Microsoft: The Reinvention of a Software Empire

I. Introduction & Setting the Stage

It’s January 2026, and Microsoft has just posted quarterly revenue of $81.3 billion. Cloud revenue has crossed $50 billion for the first time. The market cap is hovering around $3.5 trillion. And what may be the most striking line item of all: Microsoft’s AI business is now running at a $26 billion annual pace—scaling faster than almost any software segment in history. Satya Nadella, Microsoft’s third CEO, tells investors the company is “only at the beginning phases of AI diffusion,” and that it has already built an AI business “larger than some of our biggest franchises.”

Now rewind to 2013.

Microsoft’s stock had gone nowhere for thirteen years. The iPhone had swallowed the consumer internet. Google owned search and advertising. Amazon was laying the rails of the cloud. Microsoft, meanwhile, was still synonymous with two products: Windows and Office—both tied to a PC market that the world was busy declaring dead. The unflattering comparison that kept showing up in headlines was, “the next IBM.” When Steve Ballmer announced he would retire, the stock popped 7%—not because Wall Street had newfound confidence in Microsoft, but because it was relieved the company might finally change.

That sets up the deceptively simple question at the heart of Microsoft’s modern story: how did a PC software monopolist, widely written off as yesterday’s winner, become a cloud and AI platform giant worth more than almost every company on Earth?

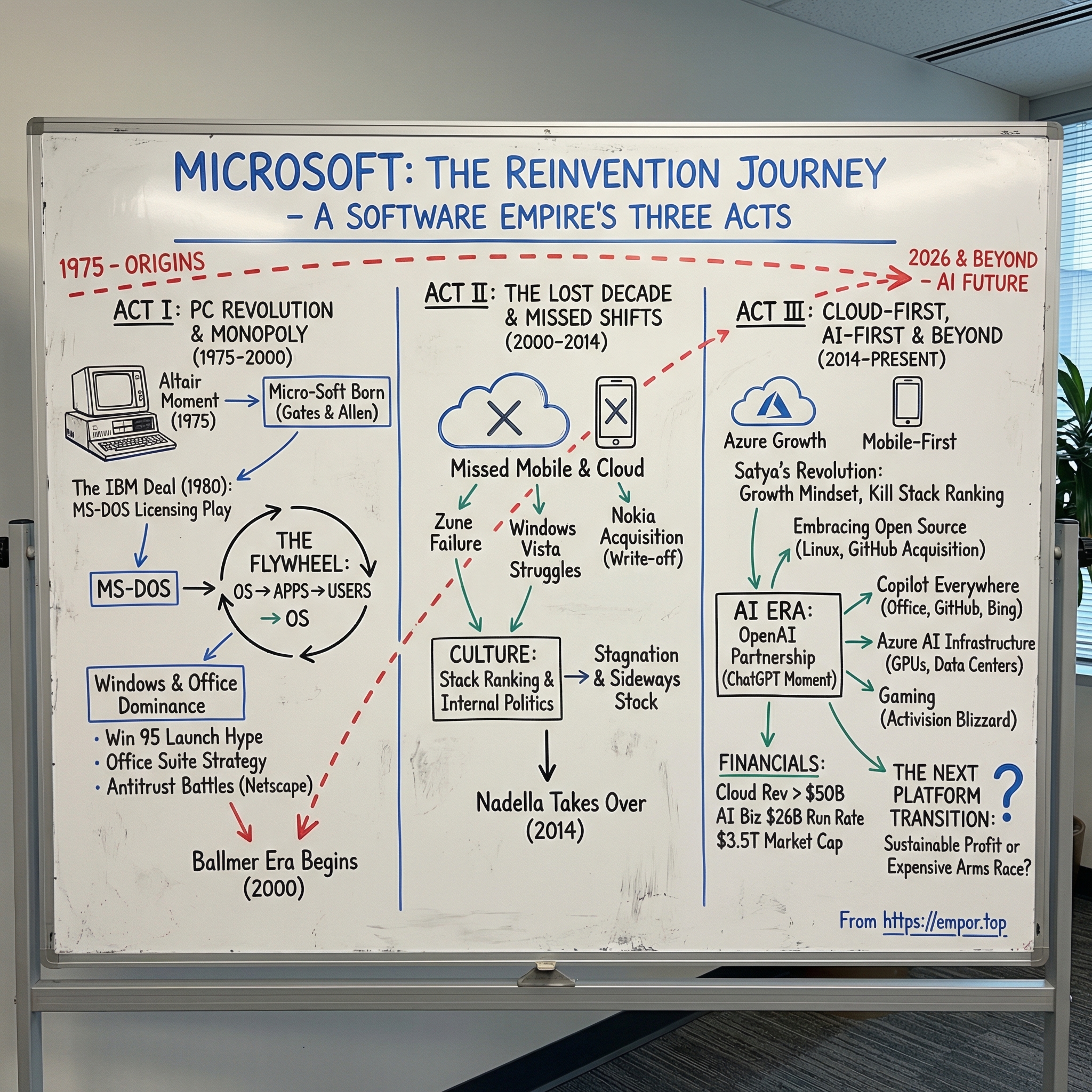

The answer is not one turnaround, but three acts of dominance—each one demanding that Microsoft shed the identity that made it successful in the previous era. First, a scrappy startup that outmaneuvered IBM. Then, the Windows-and-Office monopolist that nearly got broken up by the U.S. government. And finally, the company we see today: an enterprise platform built on cloud infrastructure, subscriptions, and AI.

What makes the reinvention so rare is that Microsoft had to fight its own instincts to pull it off. Imagine Apple deciding hardware no longer mattered, or Google treating search as a legacy product. That’s the scale of the shift here: from selling boxed licenses to renting computing power by the minute, from defending Windows at all costs to embracing Linux, from treating open source like an enemy to buying GitHub for $7.5 billion.

As we go, keep an eye on a few themes: platform transitions where the company effectively bets itself, the flywheel—both the power and peril—of developer ecosystems, the way culture can become either a moat or a millstone, and the uncomfortable law of tech: your greatest strength eventually becomes your biggest vulnerability.

This is Microsoft’s story, told through strategic pivots, internal battles, and the leaders who—at different moments—either nearly ran the company off the road or pulled it back onto the freeway.

II. Origins: The Altair Moment (1975–1981)

Paul Allen was cutting through Harvard Square on a bitter December day in 1974 when a magazine cover stopped him cold. On the rack at the Out of Town Newsstand sat the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics, screaming: “Project Breakthrough! … ALTAIR 8800.” Allen didn’t just buy it. He bolted to Currier House, burst into the room of his childhood friend Bill Gates—then a Harvard sophomore—and slapped it down like evidence.

“This is it,” he said. “It’s happening.”

Gates and Allen had been orbiting computers for years. Back at Seattle’s Lakeside School, a Mothers’ Club rummage sale had helped fund a teletype terminal in 1968, giving them the kind of early access that rewires a teenager’s brain. They’d already tried being entrepreneurs, too—building Traf-O-Data in high school to analyze traffic patterns with a homemade computer.

But the Altair was different. This wasn’t a timeshared system you begged to use. It was a computer kit ordinary people could buy—$397 worth of switches, lights, and possibility. And like most revolutionary hardware, it had one fatal flaw: out of the box, it basically couldn’t do anything. It needed software.

What happened next is the kind of story that only works because it’s true. Gates and Allen called Ed Roberts at MITS, the Albuquerque company behind the Altair, and told him they had a BASIC interpreter nearly ready to go.

They had written none of it. They didn’t even own an Altair.

Roberts, desperate for software that would make his machine more than a geeky paperweight, made them a deal: come demo it.

The next eight weeks were a sprint that bordered on reckless. Gates, Allen, and Harvard freshman Monte Davidoff wrote a BASIC interpreter for a computer they’d never touched, using a PDP-10 at Harvard to simulate the Altair’s Intel 8080 processor. The night before the trip, there was still a huge problem: they needed a way to get the program into the Altair in the first place. Allen wrote the bootstrap loader on the plane to Albuquerque—untested, and on faith.

In March 1975, at MITS headquarters, Allen sat down in front of the Altair. No keyboard. No monitor. Just a front panel: switches and blinking lights. He toggled in the bootstrap loader by hand, then connected the teletype and tried the simplest test imaginable.

PRINT 2+2

The machine clattered back:

4

That was the moment. Roberts was sold.

On April 4, 1975, in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Microsoft was born—“Micro-Soft” at first, hyphen and all, until Gates dropped it. The founding equity split told you a lot about who would run this company: Gates took 64%, Allen 36%. Gates argued he was doing more of the coding and was leaving Harvard, while Allen still had a job at Honeywell. It was pragmatic, and it was also personal. That imbalance would hang over their relationship for decades.

Those early Albuquerque years forged Microsoft’s personality. Gates was infamous for sleeping under his desk, tearing into people for sloppy code, and insisting on reviewing what shipped. The company was small, intense, and moving fast. By 1978, Microsoft had around a dozen employees and about $1 million in revenue. And Gates knew where the company had to go next: closer to deeper talent. On January 1, 1979, Microsoft moved to Bellevue, Washington—near Boeing, the University of Washington, and the tech gravity of the Pacific Northwest.

Then came a hire that would define Microsoft’s next era. Gates called his Harvard hallmate Steve Ballmer, now at Stanford Business School. Ballmer was Gates’s complement in almost every way: loud where Gates was cutting, physical where Gates was cerebral, a relentless operator with a salesman’s energy. On June 11, 1980, Ballmer joined as Microsoft’s 30th employee. His title was “Assistant to the President,” and he received 8.75% of the company. In practice, he became Gates’s negotiator, recruiter, and enforcer—the person who could turn Gates’s intensity into an organization.

Even as the company grew, the original partnership was starting to fray. Allen was often the one pulling Microsoft toward new frontiers; Gates was the one who turned ideas into product, product into leverage, and leverage into money. When Allen was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1982, he later overheard Gates and Ballmer discussing how to dilute his equity.

The bond that created Microsoft was breaking—just as the company was about to get the call that would define the entire PC industry: IBM was coming.

III. The IBM Deal & MS-DOS: The Platform Play (1980–1985)

In July 1980, Jack Sams from IBM’s Entry Systems Division flew into Seattle with a problem—and a deadline. IBM, the titan of enterprise computing, was watching Apple, Commodore, and Tandy rack up personal computer sales while it had nothing credible in the category. Inside IBM, a crash effort called Project Chess had been spun up to build a PC in about a year. To pull it off, they needed an operating system.

IBM’s first stop was Microsoft, and the meeting was supposed to be about BASIC. But Gates did something that, on the surface, looked almost too honest: he pointed IBM to the industry standard for microcomputers, CP/M, made by Gary Kildall’s company, Digital Research.

When IBM flew to Pacific Grove, California, the trip went sideways. Kildall was out flying his plane. His wife refused to sign IBM’s non-disclosure agreement. IBM left angry—and empty-handed.

So Sams called Gates back.

Microsoft didn’t have an operating system to sell. But Gates knew where one could be found. Across Lake Washington, Seattle Computer Products had built QDOS—“Quick and Dirty Operating System”—a CP/M-style system for Intel’s 8086 chip. Its creator, Tim Paterson, had gotten tired of waiting for Digital Research to ship a 16-bit version of CP/M. Microsoft licensed QDOS for $25,000, then bought it outright for another $50,000, without telling Seattle Computer Products that IBM was waiting on the other end of the line. When SCP later realized Microsoft had turned their “quick and dirty” OS into a deal worth millions, they sued. The case ended in a $1 million settlement.

This is where Gates’s real move comes into focus.

IBM wanted to buy the operating system outright for $250,000. Gates pushed for a licensing arrangement instead: IBM could ship the OS—now called MS-DOS—for a per-unit royalty, but Microsoft would keep the rights to license it to other PC makers. IBM’s negotiators reportedly saw it as naïve. Why would anyone else want software for IBM’s PC?

Gates was betting on something IBM didn’t take seriously: clones.

The IBM PC was built from off-the-shelf parts. That meant other companies could copy the hardware architecture. And if the architecture got copied, the operating system became the control point. Own that, and you didn’t just sell software—you collected a toll on an entire industry.

On August 12, 1981, IBM launched the IBM PC with MS-DOS 1.0. Within eighteen months, Compaq shipped the first IBM-compatible clone. Then came Eagle Computer, Columbia Data Products, and a flood behind them. By 1984, there were dozens of “IBM-compatible” manufacturers—and every one of them needed MS-DOS.

Microsoft’s revenue jumped from $16 million in 1981 to $97 million in 1984. But the deeper win was the flywheel. Hardware makers needed MS-DOS to be compatible. Developers wrote for MS-DOS because that’s where the users were. Users bought MS-DOS machines because that’s where the software was. Microsoft ended up in the middle of a self-reinforcing ecosystem, getting paid every time the wheel turned.

Then Microsoft tightened the screws with per-processor licensing. Instead of charging PC makers per copy of MS-DOS actually shipped, Microsoft offered a fee per computer manufactured—whether it ran MS-DOS or not. For manufacturers, it simplified forecasting. For Microsoft, it made competitors radioactive. Why would a company like Dell or Compaq pay twice—once to Microsoft on every machine, and again to a rival operating system vendor—just to experiment?

While all of this was happening, Paul Allen was watching from a hospital bed. Diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, he took a leave of absence in 1983 that became permanent. He kept his stake—an incredibly consequential decision financially—but the personal bitterness never fully went away.

By 1985, MS-DOS controlled over 80% of the PC market. And Gates, for all his love of leverage, could see the next problem coming: character-based interfaces were a dead end. Apple had shown the future with the Macintosh and its graphical interface. Microsoft needed a graphical world of its own—and the race was on.

IV. Windows & Office: The Monopoly Years (1985–2000)

On November 20, 1985, Bill Gates walked onto a stage at the Plaza Hotel in New York to show off Windows 1.0—and the truth was, it was still more idea than product. Microsoft had promised it for April 1984. It arrived almost two years late. Reviewers called it slow and cramped. The windows didn’t even overlap; they tiled, which made the name feel like a bit of a prank. And it demanded 256KB of RAM at a time when plenty of PCs were still limping along with 64KB.

But Gates wasn’t trying to win the day. He was trying to win the decade.

Apple, seeing the Macintosh interface echoed in Microsoft’s new product, sued. The case dragged on for years, finally ending in 1993. While the lawyers fought, Microsoft did what it always did: it shipped, listened, iterated, and kept moving. Windows 2.0 arrived in 1987 with overlapping windows. Windows 3.0 followed in 1990 with much better memory management. None of these releases were perfect, but they did something more important: they trained millions of people to expect a graphical interface on a PC.

The bigger move, though, wasn’t Windows. It was what Microsoft decided to build on top of it.

In 1985, Gates made a strategic bet that would reshape the entire software industry: the operating system and the flagship applications should be built together, inside the same company, optimized for each other. At the time, Lotus owned spreadsheets with 1-2-3. WordPerfect dominated word processing. Microsoft, in the background, was assembling its own stack—Word, Excel, and PowerPoint, the last of which came via the 1987 acquisition of Forethought Inc. for $14 million. The goal wasn’t to beat competitors one product at a time. The goal was to make the whole set work together—and work best on Windows.

As that strategy came into focus, Microsoft itself turned into a financial phenomenon. On March 13, 1986, it went public at $21 per share and raised $61 million. The IPO created an estimated 12,000 employee millionaires, the largest wave of that kind at the time. Gates, still only 30, was worth about $350 million. By 1987, at 31, he became the youngest self-made billionaire in history. Around Seattle, the wealth wasn’t subtle: real estate surged, and luxury cars suddenly became normal employee purchases. “Microsoft Millionaires” wasn’t a metaphor—it was a regional economic event.

Then, in May 1990, Windows 3.0 landed as the first version that felt truly ready for the mainstream. It sold 10 million copies in two years. And with Windows finally gaining real traction, Microsoft’s suite strategy snapped into place. That same year, it released Office 1.0 for Windows, bundling Word, Excel, and PowerPoint for roughly what customers might pay for a single competing product. Lotus and WordPerfect protested that it was predatory bundling. Customers saw a deal—and a simpler choice. By 1993, Office controlled about 90% of the suite market.

The flywheel was now unmistakable: Windows pushed Office, Office pulled Windows, and Microsoft collected on both sides.

And then Microsoft turned a software launch into a cultural spectacle.

Windows 95 arrived on August 24, 1995, with marketing on a scale the industry hadn’t seen: $300 million spent to make an operating system feel like a blockbuster. Microsoft bought the entire print run of The Times of London. It paid $14 million for the Rolling Stones’ “Start Me Up.” Jay Leno hosted the launch. People lined up at midnight. The Empire State Building lit up in Microsoft’s colors. Seven million copies sold in five weeks.

But the lasting innovation wasn’t the hype. It was the playbook hidden inside the product.

Windows 95 bundled Internet Explorer to go after Netscape, and Microsoft Network to take aim at AOL. When a new threat appeared, Microsoft’s response was increasingly consistent: use Windows as the distribution weapon. Netscape sold Navigator for $49. Microsoft put IE on every Windows machine and priced it at free.

That approach didn’t just reshape the browser market. It also lit the fuse on the defining legal battle of Microsoft’s monopoly era.

On May 18, 1998, the Department of Justice sued Microsoft for antitrust violations. Gates’s videotaped deposition became a public symbol of the company at its most combative—careful, evasive, arguing over definitions while prosecutors pointed to internal emails about “cutting off Netscape’s air supply.” On November 5, 1999, Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson ruled that Microsoft was a monopoly that had abused its power. On June 7, 2000, he ordered the company broken up.

The breakup never happened. Appeals courts overturned the remedy, and under the Bush administration the case ended in a settlement with behavioral restrictions rather than a split. But the real impact wasn’t the legal outcome—it was what it did to Microsoft’s posture. The company that once moved like a predator started moving like a defendant: cautious, suspicious, always watching for regulators.

It was in that atmosphere that Gates stepped down as CEO on January 13, 2000, handing the role to Steve Ballmer. Gates was 44 and worth $60 billion. Microsoft had become one of the most dominant companies in history—Windows on 95% of PCs, Office effectively synonymous with productivity.

And yet, outside Microsoft’s walls, the next era was already forming. While the company fought the Justice Department, two Stanford PhD students were building Google. Amazon was turning a bookstore into something much bigger. And Steve Jobs was quietly pressing his team with a question that would make the PC feel suddenly old: what if we built a phone?

V. The Lost Decade: Missing Mobile & Cloud (2000–2014)

Steve Ballmer bouncing onstage, drenched in sweat and chanting “DEVELOPERS! DEVELOPERS! DEVELOPERS!” became the defining image of Microsoft in the 2000s. In hindsight, it reads like a parody: loud, feverish, stuck in a world where the center of gravity was still the PC. But Ballmer wasn’t clueless. He’d helped scale Microsoft from a tiny crew into a global giant. The problem was simpler, and more dangerous: the skills that built a monopoly were exactly the wrong instincts for surviving a platform shift.

The misses came in waves. Windows Vista shipped on January 30, 2007, after five years of work and an estimated $6 billion in R&D. It arrived heavy and finicky—slow on real machines, riddled with compatibility issues, and so unpopular that Dell offered customers “downgrade rights” back to Windows XP. Then there was Zune, launched November 14, 2006, as Microsoft’s answer to the iPod. It never got close—capturing less than 5% market share before it was discontinued. It didn’t help that its signature color was, unforgettably, brown. Microsoft called it “brown sugar.” Everyone else just called it brown.

But the real catastrophe was mobile.

When the iPhone debuted in June 2007, Ballmer laughed on camera: “$500 for a phone? That doesn’t have a keyboard? Good luck with that.” At the time, Windows Mobile still looked like a contender, with 42% of the U.S. smartphone market in 2007. Three years later, it was down to 5%. Microsoft’s comeback attempt—Windows Phone 7 in 2010—was genuinely fresh, with Metro design and live tiles. It was also, fatally, late. Developers had already picked their sides. The ecosystem war had been decided.

And then Microsoft tried to buy its way back onto the battlefield.

On September 3, 2013, it announced it would acquire Nokia’s phone business for $7.2 billion. Nokia had once commanded 41% of the global mobile market in 2007; by then it was down to 3%. Microsoft was paying up for a shrinking asset, hoping distribution and branding could compensate for a lost platform. Two years later, Microsoft wrote off nearly the entire purchase price and laid off 18,000 employees, most of them from the Nokia division. It was an expensive, public lesson: if you lose the platform transition, you don’t get to purchase a time machine.

And yet, underneath the failures, Microsoft was quietly building the thing that would eventually save it: Azure.

The effort began in 2008 as “Project Red Dog,” named after a Redmond bar where the team would unwind after work. Ray Ozzie, Gates’s successor as Chief Software Architect, had sent a memo with an ominous title—“The Internet Services Disruption.” The argument was blunt: software was moving to services, Amazon Web Services was growing fast, and companies were tired of running their own servers. The future wasn’t boxed software. It was the cloud.

Azure launched commercially on February 1, 2010, as “Windows Azure”—a name that gave away Microsoft’s psychological hang-up. Even in the cloud, it still wanted Windows to be the organizing principle. Technically, Azure launched as a platform-as-a-service product when customers were gravitating toward infrastructure-as-a-service, the model AWS had popularized. Azure also pushed developers to build in Microsoft’s world, using Microsoft’s tools, in Microsoft’s way. It was the old playbook—own the platform, lock in the ecosystem—aimed at a market that was already voting for flexibility. Developers chose AWS.

If the product story was rough, the culture story was worse.

Microsoft’s internal management system, “stack ranking,” forced teams to grade employees on a curve—meaning that no matter how strong a team was, someone had to be labeled an underperformer. The incentives turned toxic. People competed against colleagues instead of competitors. Collaboration became risky. Politics beat product. Meanwhile, Microsoft Research produced breakthrough work in touch interfaces, cloud computing, and early AI, but too much of it never made it into shipping products. The Windows team wouldn’t share APIs with Office. Office wouldn’t optimize for Windows Phone. Azure became a fiefdom. The company that had once won through integration was now being hollowed out by balkanization.

By the early 2010s, the stock chart captured the mood. From $58 at the dot-com peak to $28 in 2013, Microsoft had effectively gone sideways for thirteen years. Revenue grew from $23 billion to $78 billion, but it felt like milking—extracting value from Windows and Office while the next era formed somewhere else. Apple, the company Microsoft had helped rescue with a $150 million investment in 1997, was now worth twice as much.

On August 23, 2013, Ballmer announced he would retire. The stock jumped 7% on the news.

Then came the twist. The board picked a CEO most people outside Redmond barely knew: Satya Nadella, the soft-spoken head of Cloud and Enterprise and a 22-year Microsoft veteran. The consensus reaction wasn’t excitement. It was resignation. Microsoft, people said, was the next IBM—and Nadella would simply manage the decline.

What almost no one anticipated was that Nadella would do the opposite: he’d change what Microsoft was, and in the process, change what it could become.

VI. Satya's Revolution: Cloud-First, Mobile-First (2014–2019)

Satya Nadella’s first all-hands as CEO, on February 4, 2014, felt like it came from a different company. No Ballmer-style roar. No Gates-style interrogation. Nadella spoke quietly about empathy, about learning, about a “growth mindset.” And then he did something that would have been unthinkable a few years earlier: he held up an iPhone—at Microsoft—and said their software needed to run on every device. Using a rival’s product as a prop at a Microsoft event wasn’t just a gesture. It was a statement of intent.

To understand why that moment mattered, it helps to know who Nadella was before he got the job. Born in 1967 in Hyderabad, India, he grew up a cricket fanatic. He studied electrical engineering at Mangalore University, then came to the U.S. for a master’s in computer science at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, and later earned an MBA from the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. He joined Microsoft in 1992 as an engineer and spent the next two decades moving through the company—Bing, Office, and, most importantly, the cloud organization—watching Amazon build AWS into the center of gravity while Microsoft argued internally about whether the cloud was a feature or a threat.

One of Nadella’s first moves was a new mission statement: “to empower every person and every organization on the planet to achieve more.” On paper, it reads like corporate wallpaper. In context, it was a clean break. The old mission—“a computer on every desk and in every home, running Microsoft software”—was about Microsoft’s dominance. Nadella’s version put the customer at the center. That sounds like semantics until you realize how many product decisions suddenly flip when the goal stops being “make Windows win” and starts being “help the user win.”

Then, in rapid succession, came proof this wasn’t just rhetoric.

First, Nadella killed stack ranking. The system that forced teams to sort people on a curve—guaranteeing that even great groups would have “losers”—had trained employees to hoard information, protect turf, and outmaneuver coworkers. Nadella replaced it with an emphasis on collaboration and shared outcomes. He handed senior leaders copies of Carol Dweck’s Mindset and made “growth mindset” a cultural north star. You don’t detox an organization of that size overnight, but the incentives changed, and over time the behavior changed with them.

Second, he put Microsoft all-in on the cloud—and, just as importantly, he stopped treating Windows as the sun everything else had to orbit. In March 2014, Windows Azure became Microsoft Azure. The rebrand signaled something deeper: Azure would meet developers where they were. Nadella opened it to open-source and non-Microsoft tooling—Linux, Java, Python, Docker, Kubernetes—and started saying, repeatedly, “Microsoft loves Linux.” He wasn’t being cute. By 2015, about a quarter of Azure virtual machines were running Linux. By 2019, it was more than half. For the company that once labeled Linux “a cancer,” it was a theological reversal.

Third, Nadella embraced the uncomfortable truth that the future lived on platforms Microsoft didn’t control. Office shipped on iPad and iPhone—free—within weeks of him taking the job. Visual Studio Code launched as a free editor for Mac and Linux. .NET was open-sourced. Each move upset internal purists who still wanted the old world back. Each move won trust from customers and developers who had spent years assuming Microsoft’s default setting was “lock you in.”

In 2015, Nadella made a prediction that sounded aggressive at the time: Microsoft’s cloud revenue would reach $20 billion by fiscal year 2018. Many analysts doubted it. AWS had a huge head start, and Azure was still playing catch-up. But Nadella understood something the market was slow to price in: enterprises already ran on Microsoft. Active Directory, Exchange, SQL Server, Office—this was the backbone of corporate IT. Azure didn’t ask a Fortune 500 company to abandon that stack. It offered a path to extend it.

That prediction turned out to be conservative. Microsoft reached the $20 billion run rate months early. Azure’s growth stayed above 50% year over year for long stretches. By 2019, Azure had taken roughly 20% of the cloud infrastructure market, narrowing the gap with AWS at around 33%.

At the same time, Nadella’s acquisition strategy became a kind of quiet curriculum in how to modernize a legacy giant.

In September 2014, Microsoft bought Minecraft for $2.5 billion, a deal that confused people who still thought of Microsoft as purely an enterprise software company. The logic was long-term: Minecraft wasn’t just a game. It was a creative platform where kids learned the primitives of building, experimenting, and, eventually, coding.

In December 2016 came LinkedIn for $26.2 billion—Microsoft’s biggest deal at the time. LinkedIn brought the professional graph: profiles, connections, hiring data, and daily engagement. It fit naturally alongside Office 365 and Dynamics 365, and it gave Microsoft something it had always struggled to build organically: a social network that wasn’t consumer-chaos.

Then, in October 2018, Microsoft bought GitHub for $7.5 billion, bringing the world’s largest code repository into the fold—about 40 million developers at the time. Under the old Microsoft, GitHub might have been forced into Windows and steered toward Azure at all costs. Under Nadella, GitHub stayed platform-neutral. That independence was the product. The point was trust, and Microsoft was finally willing to earn it instead of demanding it.

The business model shifted, too—and this one was existential. Office, long powered by one-time license sales, became Office 365: a subscription, typically priced around $10 to $15 per user per month. Wall Street worried Microsoft would cannibalize its own cash machine. But the logic was hard to argue with: selling a license every few years could never compete with recurring revenue year after year. By 2019, Office 365 Commercial had more than 200 million monthly active users, and Microsoft had the kind of predictable, compounding revenue stream investors love and competitors fear.

The market reaction was decisive. When Nadella took over, Microsoft’s market cap was roughly $300 billion. By the end of 2019, it had passed $1.2 trillion. The stock had quadrupled. Microsoft wasn’t just “back”—it looked, for the first time in years, like it had a future that wasn’t defined by defending the past.

And just as that future was coming into focus, Nadella was about to place his most consequential bet yet: a partnership with a small AI research lab that almost nobody was paying attention to.

VII. The AI Era: OpenAI Partnership & Beyond (2019–Present)

In July 2019, Microsoft put $1 billion into OpenAI, a San Francisco artificial intelligence lab founded in 2015 by Sam Altman, Elon Musk, and others. The structure of the deal hinted at Nadella’s real intent. Microsoft wouldn’t just write a check. It would supply massive computing power through Azure, and in return it would get preferred access to OpenAI’s models for commercial products.

At the time, most of the industry barely blinked. Microsoft could afford it. AI labs were everywhere. It was easy to file the whole thing under “smart optionality.”

Then, in November 2022, OpenAI released ChatGPT—and the ground shifted.

Within two months, ChatGPT hit 100 million users, the fastest adoption curve any consumer app had ever seen. Overnight, that 2019 deal stopped looking like optionality and started looking like positioning. Microsoft moved with a speed that didn’t match its reputation. In January 2023, it announced a “multi-year, multi-billion dollar” expansion of the partnership—widely reported at roughly $10 billion across multiple tranches—building on earlier rounds in 2019 and 2021. The upside for Microsoft was obvious: rights to weave OpenAI’s GPT models across its product suite. The cost was equally clear: Microsoft would have to supply the infrastructure to train and run them at scale.

Here’s why that trade mattered. If cloud computing is the electricity of the digital age, then generative AI is the appliance that makes everyone’s power bill explode. Every Copilot prompt, every chat query, every generated image is compute—running somewhere. Microsoft wasn’t only betting on AI as a product category. It was manufacturing demand for Azure.

And the rollout was sweeping.

Azure OpenAI Service gave enterprises a way to use GPT models inside Microsoft’s cloud with the compliance and security posture large companies needed. GitHub Copilot, launched in 2022, brought AI into the most leveraged job in tech: writing code—and within a year it was generating nearly half the code in projects where it was turned on. Microsoft 365 Copilot pushed the same idea into Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Outlook, and Teams: the interface stays familiar, but a new “teammate” appears inside it. Bing was rebuilt around a chat experience. Microsoft Designer integrated DALL-E to generate images. One by one, Microsoft’s major franchises got an AI layer, and Azure sat underneath all of it.

Then came the weekend that made the partnership feel less like a business alliance and more like a geopolitical relationship.

On November 17, 2023, OpenAI’s board fired Sam Altman, saying it had lost confidence in his leadership. What followed was a chaotic, high-stakes scramble, with Microsoft in the middle. Nadella announced that Altman and OpenAI co-founder Greg Brockman would join Microsoft to lead a new advanced AI research team. OpenAI’s employees revolted; about 95% threatened to quit and follow Altman. Within days, the board reversed course, Altman returned as CEO, and OpenAI’s board was reshaped. Microsoft kept the partnership—and arguably improved its leverage by proving it had a path forward even if OpenAI imploded.

Two years later, the relationship was rewritten again.

In October 2025, OpenAI completed its shift from a nonprofit structure into a for-profit public benefit corporation called OpenAI Group PBC. Microsoft ended up with a 27% equity stake, valued at roughly $135 billion based on OpenAI’s reported $500 billion valuation. Microsoft’s IP rights to OpenAI’s models and products were extended through 2032, and expanded to cover models developed after any future declaration of artificial general intelligence.

But the rewrite also introduced friction. OpenAI committed to buying an incremental $250 billion of Azure services—an eye-popping figure that made up 45% of Microsoft’s commercial remaining performance obligations as of the January 2026 earnings report. At the same time, Microsoft lost its right of first refusal as OpenAI’s exclusive cloud provider. OpenAI cut a separate $300 billion deal with Oracle and gained more freedom to run non-API products on other clouds. Microsoft responded the way a platform company responds: it diversified. It formed its own MAI Superintelligence Team to push advanced AI research internally, and it broadened Azure’s menu to include competing models, including Anthropic’s Claude.

By early fiscal 2026, Copilot was already everywhere inside enterprise IT. More than 90% of Fortune 500 companies used Microsoft 365 Copilot, with more than 150 million monthly active users. Microsoft’s AI business hit a $26 billion annual run rate—one of the fastest ramps any software category has ever seen. But the market around it was no longer a one-horse race. Google’s Gemini was gaining ground. Amazon was going deeper with Anthropic. Microsoft’s early advantage of “we have the model” started giving way to a world where customers expected choice: multiple models, multiple vendors, and pricing pressure.

Which brings us to the investor question that now hangs over everything: does this spend turn into durable profit?

The bill is enormous. Microsoft’s capital expenditures reached $37.5 billion in fiscal Q2 2026 alone. After the January 28, 2026 earnings report, the stock fell more than 11% even though Microsoft beat expectations on both revenue and earnings. The worry wasn’t that the business was weak. It was that the arms race was getting expensive—and that Azure growth had decelerated slightly, to 39% from 40% the prior quarter.

The market’s question is simple, and brutal: is Microsoft spending to build an unassailable position in the next platform transition, or is it pouring money into a fight where nobody gets to own the platform this time?

VIII. Business Model Evolution & Financial Analysis

Microsoft’s pivot from boxed software to cloud subscriptions is one of the cleanest business model rewrites in modern corporate history. And it’s the reason the company can bankroll an AI arms race without blinking.

In the old world, Microsoft got paid in bursts. Windows and Office were largely one-time purchases. A company might buy a Windows license for each PC, pay again for an Office suite, and then sit tight for years. Revenue rose and fell with PC refresh cycles and big release launches. Great when a new version hit. Awkward when customers skipped a cycle.

Office 365 and Azure flipped that logic. Instead of getting paid once every five to seven years, Microsoft started getting paid every month. Microsoft 365 turned productivity into a per-user subscription. Azure turned infrastructure into a utility: pay for what you use, scale up when you need it, scale down when you don’t. The result wasn’t just “recurring revenue.” It was revenue that tends to expand over time, because customers add seats, adopt more services, and consume more compute.

That shift shows up everywhere in how Microsoft now talks about itself. It reports in three segments: Productivity and Business Processes (Office 365, LinkedIn, Dynamics), Intelligent Cloud (Azure and server products), and More Personal Computing (Windows, devices, and gaming—now including Activision Blizzard, acquired for $75.4 billion in October 2023, which made Microsoft the world’s third-largest gaming company).

The engine, though, is the cloud. “Microsoft Cloud”—Azure, Office 365 commercial, the commercial portions of LinkedIn, and Dynamics 365—cleared $33 billion in quarterly revenue in fiscal 2025, then crossed $50 billion in the quarter ending December 2025. Azure is now used by 95% of the Fortune 500. And Azure’s consumption pricing has been a quiet weapon: it lets enterprises modernize without making a giant upfront bet on building and maintaining their own data centers.

Under Nadella, the numbers stopped being “pretty good for a legacy company” and became something closer to relentless. Revenue climbed from $86 billion in fiscal 2014 to more than $280 billion in fiscal 2025. Operating margins expanded from roughly 30% to over 45%. The stock rose nearly tenfold, compounding at around 27% annually. And Microsoft has deployed that cash with discipline: heavy R&D (now nearing $30 billion a year), big but purposeful acquisitions, a growing dividend, and steady buybacks.

But this is where the story collides with the AI era: capital expenditures.

In late 2025, Microsoft spent $37.5 billion in a single quarter—about two-thirds on long-lived assets like data centers and about one-third on shorter-lived assets like GPUs. Annualized, that implies a capex pace of roughly $150 billion. The bull case is straightforward: Microsoft is building capacity into demand that customers have already committed to, reflected in commercial remaining performance obligations of $625 billion, up 110% year-over-year. The bear case is just as simple: AI infrastructure could commoditize, GPU economics could shift, or demand could flatten before those investments earn the returns investors expect.

What gives Microsoft its best shot at making the spend pay off is how the pieces reinforce each other. Azure, Office 365, and Dynamics 365 aren’t just product lines—they’re a bundling strategy that’s hard to replicate. Amazon can lead in infrastructure and still have nothing like Office. Google can have great productivity tools and still lag in enterprise relationships. Microsoft can walk into a CIO’s office with email, documents, collaboration, CRM, ERP, cloud infrastructure, developer tools, and now AI—integrated, supported, and purchasable through one relationship.

In a world where AI is getting cheaper to copy and harder to defend, distribution and integration start to matter more than ever. Microsoft’s business model has become exactly that: a set of subscriptions and platforms that make it easier to say “yes” to the next Microsoft product than to stitch together five different vendors.

IX. Playbook: Lessons from Three Transformations

Microsoft’s fifty-year history is really three reinventions stacked on top of each other. Different eras, different technologies, same underlying pattern: when the platform shifts, Microsoft either finds a way to ride it—or spends years paying for missing it.

The first transformation, from DOS to Windows, took the better part of a decade. Gates saw that character-based interfaces were a dead end long before most of the industry was ready to admit it. But seeing the future and shipping it are two different things. Early Windows versions were late and underwhelming, and Microsoft still pushed them out anyway. That’s the lesson: platform transitions rarely arrive as a single, clean “new thing.” They show up as a messy sequence of releases where version 1.0 is embarrassing, version 2.0 is tolerable, and version 3.0 finally feels inevitable. Microsoft kept iterating until Windows was good enough—and by then, it had something rivals couldn’t manufacture: distribution and familiarity.

The second transformation, from desktop software to cloud subscriptions, demanded something even harder: cannibalizing the old model before someone else did it for them. That meant asking a company trained to sell big, one-time licenses to embrace recurring subscriptions that could look smaller at the moment of sale, even if they compounded into something much larger over time. Nadella’s key move was making the shift feel like identity, not accounting. He talked about empathy, about customers, about learning. In other words: it wasn’t “we’re killing the old business.” It was “we’re becoming the company the next era requires.”

The third transformation, from cloud to AI, is still unfolding—and it rhymes with the first two. Move early. Spend aggressively. Accept that the first wave won’t be perfect. And then use the advantage Microsoft has always had, for better and worse: reach. Azure OpenAI Service, GitHub Copilot, and Microsoft 365 Copilot all launched into the world as works in progress, and they’re getting revised in public, at speed. That’s not a bug in Microsoft’s strategy. It’s the strategy.

Across all three eras, one theme keeps deciding who wins: developers.

MS-DOS became the standard because that’s where the software was. Windows took over because developers built for it. And the “lost decade” was, in part, a developer story too—iOS and Android became the default for mobile, and AWS became the default for cloud, because that’s where developers went first. Nadella’s recovery plan wasn’t just Azure features and pricing. It was rebuilding trust: GitHub, Visual Studio Code, open-sourcing .NET, embracing Linux. Now, with GitHub Copilot at the center of AI-assisted coding, Microsoft has once again made itself feel like home base for developers at the start of a new platform cycle.

Then there’s Microsoft’s signature competitive move: bundling and integration.

Microsoft is rarely the first to a breakthrough. Apple popularized the GUI. Amazon led the modern cloud. Google’s AI research has been deeper for longer. But Microsoft has repeatedly turned “not first” into “best distributed.” It takes a new capability and wires it into an ecosystem customers already rely on. Office pulls in Teams. Teams deepens reliance on Microsoft 365. Microsoft 365 reinforces Azure. Azure becomes the place you deploy the new thing—now including AI. Each product doesn’t just sell itself; it increases the switching costs of everything around it.

Finally, the most transferable lesson of all: culture is strategy with teeth.

Microsoft’s lost decade wasn’t primarily a failure of talent or technology. The company had world-class research and plenty of resources. The failure was execution—teams optimized for internal wins, not customer outcomes. Collaboration was risky. Protecting turf was rational. Nadella’s most important contribution wasn’t spotting the cloud or betting on AI. Those were visible trends. His real work was cultural repair: changing incentives so it became safer to share, easier to ship, and unacceptable to win internally while losing externally. Because no pivot survives contact with reality unless the organization is built to execute it.

X. Bear vs. Bull Case & Future Outlook

Bear Case

The sharpest bear argument is simple: capital intensity. Microsoft is spending at a pace that would make an oil major blink—$37.5 billion in a single quarter—building AI infrastructure whose long-term return profile is still a guess. If generative AI ends up following a familiar hype-cycle arc, where early excitement outstrips sustained enterprise usage, Microsoft could be left with billions of dollars’ worth of data centers and GPUs looking for demand.

Azure is also still playing from behind. It trails AWS in cloud market share—roughly 25% to Amazon’s 31%—and while Azure has closed the gap over time, the lead has proven stubborn. At the same time, Microsoft’s AI narrative is tightly linked to OpenAI, and that partnership has gotten more complicated. OpenAI now has the freedom to diversify away from Azure, and its $300 billion Oracle deal is proof it will. If OpenAI builds more of its own distribution, or if Google’s Gemini and Anthropic’s Claude narrow the quality gap, Microsoft’s advantage could compress into “we have great distribution” rather than “we have the best product.”

Then there’s regulation—an old ghost for Microsoft, back in modern clothing. Antitrust authorities in the U.S. and Europe have scrutinized the OpenAI investment structure, questioning whether it functions like a de facto acquisition without going through merger review. The FTC opened an inquiry in early 2025. If regulators force a restructuring, Microsoft wouldn’t just lose a talking point; it could lose time—exactly what you can’t afford in a platform transition.

A slower, less dramatic risk is the long tail of legacy decline. Windows OEM revenue keeps sliding as the PC market stagnates. On-premises server products face structural headwinds as customers move to cloud services. And gaming—now much bigger after the Activision Blizzard acquisition—adds integration risk and tends to run at lower margins than Microsoft’s core software franchises.

Finally, cybersecurity has become a reputational tax. High-profile incidents, including the 2023 Storm-0558 attack in which Chinese hackers accessed senior U.S. government officials’ email via a Microsoft cloud vulnerability, triggered Congressional scrutiny. For a company whose superpower is enterprise trust, security failures aren’t just bad PR—they can change procurement decisions.

Bull Case

The bull case starts with what Microsoft does better than almost anyone: turn a new capability into an enterprise default. Microsoft’s AI strategy creates the kind of lock-in that Hamilton Helmer would recognize immediately—switching costs and network effects reinforcing each other. If an organization rolls out Microsoft 365 Copilot, builds custom tools on Azure OpenAI Service, and standardizes developer workflows on GitHub Copilot, it isn’t “trying AI.” It’s rewiring how work gets done. And once that happens, switching becomes less a vendor choice and more an organizational trauma. This isn’t hypothetical: 90% of the Fortune 500 already uses Microsoft 365 Copilot.

Distribution is the other unfair advantage. Microsoft has sales relationships with essentially every major enterprise on Earth, built over decades of selling Office, Windows, and server software. And it isn’t asking customers to adopt a standalone AI app. It’s dropping AI into the tools employees already live in: Copilot in Outlook, summaries in Teams, analysis in Excel. That matters because adoption friction is often the real enemy—procurement, security reviews, training, integration. Microsoft has a way to make AI feel like a feature update, not a new category.

Zoom out further and the runway is still long. Global cloud adoption remains early, with enterprise cloud penetration at roughly 30–40% of total IT spending. Many regions—Asia, Latin America, the Middle East—are even earlier in the cycle. If cloud is still in the middle innings, and AI is the next workload wave, Azure doesn’t need to “win” to be enormous. It just needs to stay in the top tier.

And while gaming isn’t the core investment thesis, it’s meaningful optionality. The $75.4 billion Activision Blizzard acquisition brought franchises like Call of Duty, World of Warcraft, and Candy Crush—massive, recurring audiences. Paired with Xbox Game Pass, a subscription model that echoes the Office 365 playbook, Microsoft has a credible shot at doing in consumer entertainment what it already did in productivity: make the subscription the default.

Even through the colder lens of Porter’s Five Forces, the picture is coherent. Supplier power is the big risk—Nvidia’s dominance gives it leverage over AI infrastructure economics, which is exactly why Microsoft built Maia, now in second-generation deployment. Buyer power is real but limited: enterprises can choose AWS or Google Cloud, but switching is painful. New entrants are unlikely because the capital requirements are brutal. Substitutes are the wildcard—if open-source models become “good enough,” proprietary partnerships matter less. Rivalry is intense, but with three dominant players, the market is more likely to be competitive than suicidal.

KPIs to Watch

Two numbers tell you most of what you need to know.

First: Azure revenue growth in constant currency. This is the clearest signal of whether Microsoft’s enormous capex is turning into real demand. The recent deceleration from 40% to 39% was enough to knock the stock down 11%, which tells you how sensitive the market is to this trajectory.

Second: commercial remaining performance obligations (RPO)—both its growth and what’s inside it. RPO hit $625 billion in the January 2026 quarter, up 110% year-over-year, but 45% of it was tied to a single customer: OpenAI. Investors should watch the overall expansion, but also whether the backlog is becoming broader and healthier—or more concentrated and brittle.

XI. Power Analysis & Closing Thoughts

Microsoft’s competitive position, through Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers lens, explains how it has stayed on top across three different technology eras—and why it has a real shot at doing it again.

Network effects show up most clearly in the developer ecosystem. More developers build on Microsoft platforms, which creates more software, which attracts more users, which pulls in more developers. That flywheel powered MS-DOS and Windows. Today, it runs through Azure, GitHub (now home to about 100 million developers), and the Microsoft 365 universe. In the AI era, that dynamic gets supercharged: tools like GitHub Copilot get better as usage grows, creating a feedback loop where adoption itself improves the product.

Switching costs are Microsoft’s deepest moat. When an enterprise runs Active Directory alongside Exchange Online, SharePoint, Teams, Dynamics 365, and Azure, Microsoft stops being a vendor and becomes infrastructure. Moving off that stack isn’t a “new contract.” It’s a multi-year migration with retraining, downtime risk, security reviews, and political fallout. And the bundling effect matters: every additional Microsoft product doesn’t just add value—it makes everything else harder to replace.

Scale economies are most obvious in cloud infrastructure. Data centers, global networking, chip supply agreements, and platform engineering are huge fixed costs. Microsoft can spread those costs across an installed base that very few companies on Earth can match. AI pushes this to an extreme: training and serving frontier models takes staggering compute. In practice, that kind of spend narrows the true playing field to a small set of hyperscalers.

Brand power in the enterprise is easy to overlook because it doesn’t feel “techy,” but it’s real. CIO decisions are career decisions. Choosing a cloud provider isn’t just about features—it’s about who you trust when something breaks at 2 a.m. Microsoft benefits from a modern version of an old line: nobody gets fired for choosing Microsoft. Decades of enterprise support, backward compatibility, and relationship depth create an advantage that newer competitors have to earn the hard way.

And then there’s the counterfactual: what if Satya Nadella never became CEO?

In 2014, Microsoft already had many of the ingredients it later used to win: Azure existed, Office was dominant, and the research bench was world-class. What it lacked was cultural permission—permission to cannibalize old profit pools, to ship Microsoft software on competitors’ devices, to embrace Linux, and to treat the cloud as the center rather than a side bet. A different CEO could have kept defending Windows as the organizing principle, stayed hostile to open-source, and played cloud as a feature instead of a platform. Same assets, radically different outcome.

Microsoft’s place in tech history is unusual precisely because it’s rare. Most great companies get one era, maybe two. IBM owned mainframes but missed PCs. Apple defined the smartphone era but never became the backbone of enterprise IT. Google dominated search and advertising yet still trails in enterprise cloud. Amazon built the cloud but doesn’t have anything like Office or Windows as a distribution wedge. Microsoft is the outlier: a company that has been a defining force across multiple paradigms—and that survived the transitions between them.

Now the question is whether AI becomes a fourth act of dominance, or the start of a new vulnerability.

Microsoft is committing roughly $150 billion a year to AI infrastructure. It’s the biggest bet the company has ever made, and it comes with a binary feeling to it. If AI reshapes work the way Microsoft believes it will, Microsoft is positioned to capture an outsized share through distribution, integration, and enterprise trust. If AI commoditizes faster than expected—or demand doesn’t match the buildout—then Microsoft risks turning data centers and GPUs into the most expensive form of overcapacity.

Either way, the arc of this story is adaptation. Microsoft built a monopoly, nearly got stuck defending it, and then rebuilt itself—twice. In an industry where relevance usually expires, Microsoft is attempting something few companies even get a chance at: staying essential for a fourth era. The next few years will tell us whether the reinvention machine still works.

XII. Recent News

Microsoft’s fiscal second-quarter 2026 earnings, reported on January 28, 2026, captured the company’s current reality in one snapshot: the business is still growing fast, but the price of staying in front is getting very large.

Revenue came in at $81.3 billion, up 17% year-over-year. Operating income rose 21% to $38.3 billion. Non-GAAP diluted EPS was $4.14, up 24% and ahead of the $3.86 analysts were expecting. Cloud revenue topped $50 billion for the first time. Azure grew 39% in constant currency—still blistering, but a slight deceleration from 40% the quarter before. And the spending behind all of it was unmistakable: capital expenditures hit $37.5 billion in the quarter.

The most telling line, though, was the backlog. Commercial bookings surged 230% year-over-year, and commercial remaining performance obligations climbed to $625 billion, up 110%. A significant driver was OpenAI’s $250 billion Azure commitment—an enormous vote of confidence, but also a concentration investors can’t ignore.

Even with the beat, the stock dropped more than 11%. The market wasn’t questioning demand. It was questioning the math: whether Azure’s growth can stay high enough, long enough, to justify the scale of the buildout. Microsoft’s guidance didn’t calm nerves. For fiscal third quarter, it forecast revenue of $80.65 billion to $81.75 billion, and Azure growth of 37% to 38% in constant currency—another step down.

The OpenAI relationship also continued to evolve. In October 2025, Microsoft and OpenAI signed a restructured agreement as OpenAI completed its transition to a for-profit public benefit corporation. Microsoft received a 27% equity stake, and its IP rights to OpenAI models were extended through 2032. But there was an important giveback: Microsoft lost its right of first refusal as OpenAI’s exclusive cloud provider.

On the infrastructure side, Microsoft unveiled its second-generation Maia AI chip in January 2026, aimed at reducing dependence on Nvidia hardware and improving the margins on AI workloads. And on the brand-and-marketing front, it announced a multiyear partnership with the Mercedes-AMG PETRONAS Formula 1 Team on January 22, 2026.

Finally, the cost-cutting side of the cycle showed up again. Reports indicated Microsoft could be planning another round of layoffs, potentially affecting between 11,000 and 22,000 roles, alongside a stricter return-to-office policy: employees within 50 miles of an office would be required to work on-site at least three days per week starting February 23, 2026.

XIII. Links & References

- Microsoft FY26 Q2 Earnings Press Release

- Microsoft Q2 2026 Earnings Report — CNBC

- Microsoft and OpenAI Restructured Partnership — Official Microsoft Blog

- OpenAI For-Profit Transition and Microsoft Stake — Data Center Dynamics

- Microsoft Activision Blizzard Acquisition — Wikipedia

- Microsoft 2025 Annual Report

- Hit Refresh by Satya Nadella (Harper Business, 2017)

- Hard Drive: Bill Gates and the Making of the Microsoft Empire by James Wallace and Jim Erickson

- Idea Man by Paul Allen (Portfolio/Penguin, 2011)

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music