Moderna: The Code of Life

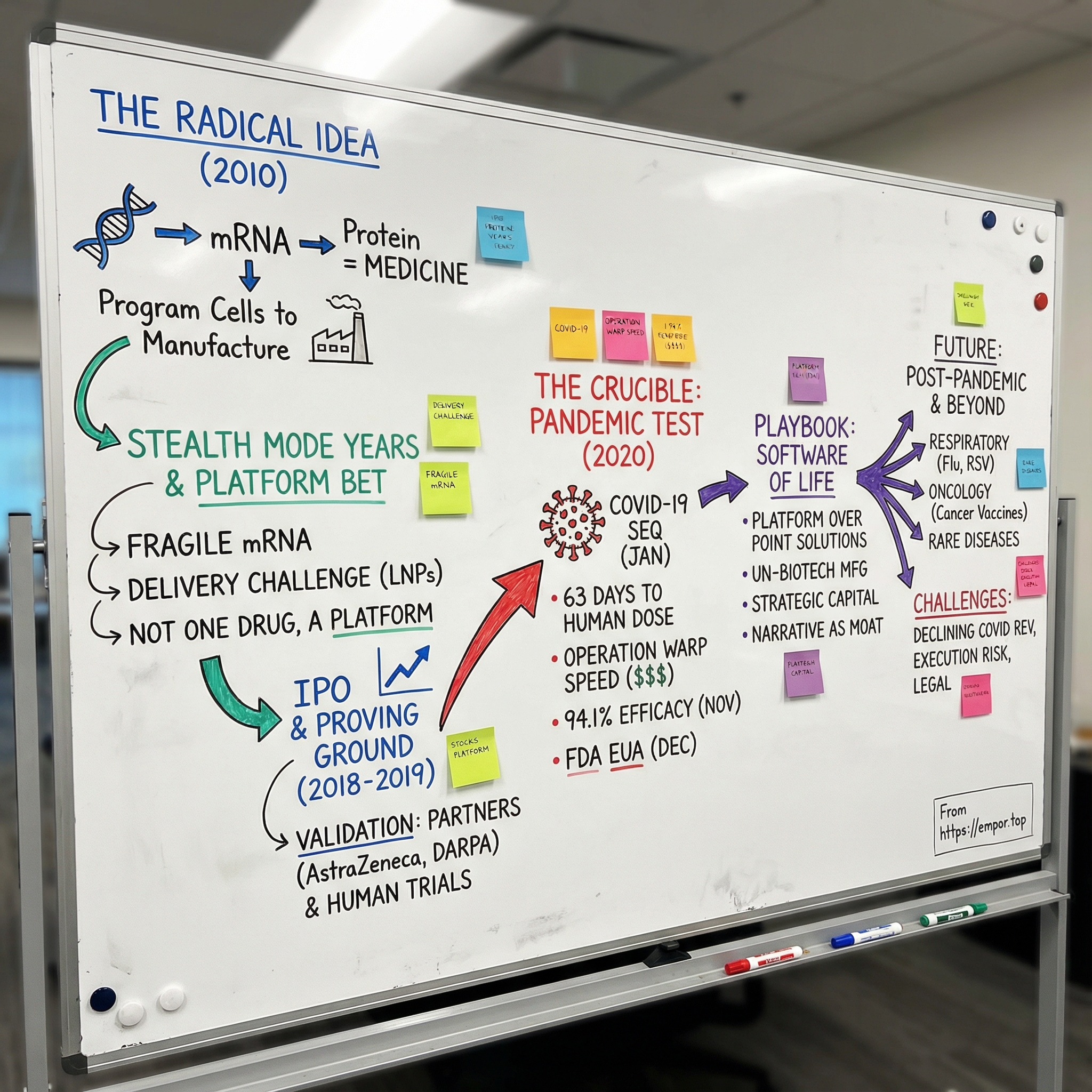

I. Introduction: A Bet on the Impossible

January 2020. A mysterious new virus is moving fast, jumping from headlines to hospital wards. The world doesn’t know it yet, but within weeks daily life will shut down: flights canceled, offices dark, ICU beds scarce. And suddenly, the most urgent problem on Earth is also the most brutal kind of test—can science outrun exponential spread?

In that moment, hope doesn’t rest only with pharmaceutical giants that have spent a century shipping medicines by the truckload. A huge share of it lands on a young biotech company in Cambridge, Massachusetts—one that, remarkably, has never brought a single product to market.

This is the story of Moderna.

To understand why Moderna was even in the conversation, you have to go back to 2010. Noubar Afeyan and his colleagues weren’t trying to build one great drug. They were trying to build a new way to make drugs—using messenger RNA as the instruction set. The pitch was almost offensively simple: stop manufacturing medicines exclusively in stainless-steel factories. Instead, deliver a message into the body and let your own cells do the manufacturing. Program the right instructions, and biology becomes the production line.

It was an idea so clean it sounded like science fiction—and to many scientists, it sounded like a category error. mRNA is fragile. The body is built to destroy foreign RNA. And yet Moderna kept raising money, kept hiring, kept expanding, building a reputation that was equal parts fascination and skepticism.

So the question that hung over the company for more than a decade wasn’t subtle: how did a business with a massive valuation and no approved drugs end up delivering a world-saving vaccine in record time—and, in the process, prove that an entirely new class of medicine could work?

The path runs through years of doubt, through partnerships that provided both cash and credibility, through a landmark IPO that put Moderna’s story on the public markets, and then into the crucible of the pandemic—when the world stopped asking whether mRNA could work someday, and started demanding that it work now.

This is the story of the software of life—and the people who bet everything on making it real.

II. The Genesis: Rewriting the Rules of Biology

In the spring of 2010, on an unseasonably warm May day in Cambridge, a young Harvard professor named Derrick Rossi crossed the Charles River for a meeting that would change the trajectory of modern medicine. He wasn’t headed to a venture firm or a hospital. He was headed to the office of Robert Langer, the legendary MIT bioengineer whose lab had already produced an almost absurd volume of papers, patents, and biotech companies.

Rossi arrived with a laptop full of results and a deceptively simple claim: mRNA—normally too fragile and too inflammatory to use as medicine—could be made to behave.

His breakthrough was a kind of molecular disguise. Rossi had learned how to modify key building blocks of mRNA so the body wouldn’t immediately treat it like an invader. With those changes, the message could slip into cells, get read by the cell’s machinery, and produce protein—powerful enough, in his stem-cell experiments, to reprogram adult cells back into induced pluripotent stem cells.

To see why this landed with such force, you need the basic wiring diagram of biology: DNA → RNA → protein. DNA is the long-term storage in the nucleus. Messenger RNA is the courier—temporary instructions copied from DNA and delivered to ribosomes, the cell’s protein factories. Proteins then do the work of life: they signal, repair, attack pathogens, and build tissue.

Traditional biotech mostly works downstream. It manufactures proteins in industrial facilities, purifies them, ships them, and injects them. It works—but it’s slow, expensive, and limited by what you can reliably make outside the body.

Rossi was proposing something more like software. Don’t ship the protein. Ship the instructions.

Langer immediately latched onto the real prize, which wasn’t stem cells at all. It was the method—the ability to tweak mRNA so it could do its job without setting off alarms. As he listened, he saw past the initial experiment and into the platform. This wasn’t just a trick for one application. It was a general-purpose way to get cells to make proteins on command. As Langer put it to Rossi, the implications went far beyond stem cell behavior: you could apply it to make anything.

Rossi’s work didn’t appear out of thin air. It built on foundational research by Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman, who in 2005 showed that swapping in a modified nucleoside—pseudouridine—could help mRNA evade the body’s immune defenses. Rossi’s team demonstrated how nucleoside-modified synthetic mRNA could drive efficient protein expression and cellular reprogramming without triggering severe inflammatory responses, including experiments converting adult fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells. The leap wasn’t the concept that mRNA could be tamed—it was what taming it could unlock: repeatable, transient protein expression that could be scaled into therapeutics.

Three days after his meeting with Langer, Rossi delivered the same message to a very different audience: Flagship Ventures, the venture creation firm run by Noubar Afeyan. Flagship didn’t just fund startups; it liked to invent them. Inside its VentureLabs incubator, it would start with a big “What if?” and then build a company to answer it.

Afeyan himself was built for that style of ambition. Born in Beirut in 1962 to Armenian parents, he did his undergraduate work at McGill University, earned his Ph.D. in biochemical engineering at MIT in 1987, and built a reputation for turning deep science into real businesses. Before Flagship, he founded and led PerSeptive Biosystems, a bio-instrumentation company that grew into a major player.

Rossi, Langer, and Kenneth R. Chien joined forces to found Moderna so they could push the mRNA work beyond academia and into products. Tim Springer of Harvard—already a proven biotech entrepreneur—became the first investor Rossi secured for the new company.

Even the name was a thesis. Moderna came from “Modified RNA,” a signal that this wasn’t a one-drug bet. It was an attempt to create a new category of medicine.

But platforms don’t run themselves. Afeyan recruited Stéphane Bancel, who joined Flagship as a Senior Partner and joined Moderna’s board in March 2011, then became Moderna’s CEO in October 2011.

Bancel brought exactly what a high-wire science platform needed: operational discipline and industry credibility. He had been chief executive officer of the French diagnostics company bioMérieux SA for five years. Before that, he spent time at Eli Lilly and Company in roles that included managing director for Belgium and executive director of global manufacturing strategy and supply chain. Moderna wasn’t just trying to prove a scientific point—it was trying to become a manufacturing-driven medicines company. Bancel had lived that world.

His background fit the job. Raised by an engineer father and a doctor mother, Bancel gravitated early toward computers, math, and science. He earned a Master of Engineering from École Centrale Paris, a Master of Science in chemical engineering from the University of Minnesota, and an MBA from Harvard Business School.

What he saw at Moderna wasn’t a single breakthrough waiting for a single approval. It was the possibility of a repeatable engine. If mRNA could be engineered to produce any protein, then in theory one core process could generate therapies across thousands of diseases. The promise was enormous—and so was the list of things that still had to go right.

III. The "Stealth Mode" Years & The Platform Bet

The problem with mRNA, as every molecular biologist knew, was devastatingly simple: it’s fragile. The human body has spent millions of years evolving ways to spot and destroy foreign genetic material. Enzymes called RNases are everywhere—ready to shred stray RNA on contact. And if the RNA survives long enough to be noticed, the immune system can respond with the biological equivalent of pulling a fire alarm.

Even if you could solve those two issues, there was still the most practical one of all: delivery. How do you get a delicate strand of code into the right cells, intact, so it can actually be read?

For years, those hurdles pushed mRNA to the edges of serious drug development. Scientists had understood mRNA’s role since the 1960s, but turning it into a usable medicine was another matter. RNA is transient by design. It doesn’t want to stick around. It breaks down easily, and biology is very good at making sure it stays that way.

Delivery science didn’t offer an easy escape hatch, either. For more than three decades, lipid-based approaches looked promising in the lab and then disappointed in animals and humans. Many positively charged lipids were simply too toxic. And when researchers injected these particles intravenously, they tended to end up in the same place: the liver. Getting reliable delivery beyond the liver was—and remains—one of the field’s toughest problems.

The breakthrough that made Moderna’s ambition plausible came from lipid nanoparticles, or LNPs: tiny fatty spheres that could wrap mRNA, shield it from destruction, and help it slip into cells. LNPs weren’t a Moderna invention, but they became the enabling technology that turned mRNA from an idea into something you could plausibly manufacture, ship, and inject.

And they were hard. The industry had been wrestling with LNPs for years. Moderna felt that pain firsthand. Without the packaging, the medicine doesn’t exist. As Giuseppe Ciaramella, who led infectious diseases at Moderna from 2014 to 2018, put it: “It is the unsung hero of the whole thing.”

Once Moderna decided existing lipid formulations weren’t good enough, it treated the problem like its own internal drug discovery program. “There was a group of chemists put on this right away to build novel cationic lipids,” Ciaramella said. “It is kind of like a small-molecule drug discovery engine, but on steroids.” The team synthesized around a hundred ionizable lipids, adding ester linkages into the carbon chains to make them more biodegradable—pushing toward the holy grail: effective delivery without unacceptable toxicity.

That grind captured Moderna’s broader, contrarian strategy. Most biotechs pick a disease, pick a molecule, and march it forward as the “lead” program. Moderna kept insisting it wasn’t building a single drug. It was building a platform. If the company could reliably deliver mRNA and get cells to translate it into protein, then new products wouldn’t require inventing a whole new manufacturing system each time. You’d change the code, and you’d change the output—more like software updates than bespoke biology.

The upside was enormous. The cost was immediate.

By 2018, Moderna was burning cash at a rate that made traditional investors squint. In the first nine months of that year alone, it logged almost $360 million in operating expenses and said it had accumulated a deficit of $865.2 million. And because the company was running many programs at once rather than spotlighting one flagship candidate, outsiders had a hard time answering the simple valuation question: what, exactly, are we betting on?

The culture didn’t help. STAT reported that Bancel ran Moderna with a high degree of secrecy and little outside review of its science. That secrecy was interpreted two ways—either as protection for something truly revolutionary, or as a curtain drawn around a technology that still didn’t work.

In the absence of approved products, Moderna needed a different kind of proof. It got it, not from the public markets, but from partners willing to attach their names to the bet.

In March 2013, AstraZeneca signed an exclusive agreement with Moderna to discover, develop, and commercialize mRNA therapeutics for serious cardiovascular, metabolic, and renal diseases, as well as cancer. AstraZeneca paid $240 million upfront. Reportedly, it was the largest preclinical deal payment of its kind at the time.

This wasn’t just money. It was a global pharma giant saying, in public, that mRNA wasn’t merely interesting—it was worth staking reputation and capital on before any clinical readouts.

Later that year, Moderna got a second kind of validation from a very different customer. In October 2013, DARPA awarded Moderna up to about $25 million to support mRNA medicines—primarily for vaccine and antibody programs aimed at threats like Chikungunya.

The grant came through a DARPA effort called ADEPT: PROTECT, built around a simple and frightening premise: the next biological threat might arrive before you even have the pathogen in hand. DARPA wasn’t looking for a better chronic-disease pipeline. It wanted a platform that could be deployed safely and rapidly against emerging infectious diseases and engineered biological weapons—even when the threat was unknown.

That interest was almost eerie in hindsight. Moderna’s value proposition had always been speed, and DARPA’s ambitions only grew. Work in this area helped set the stage for later efforts like the Biological Technologies Office and, in 2017, the Pandemic Prevention Platform, which aimed for something that sounded outrageous at the time: producing a new vaccine or antibody treatment within roughly 60 days of a new threat.

Between AstraZeneca and DARPA, Moderna secured nearly $300 million in a single year from partners who weren’t buying a product—they were buying the possibility that the platform was real.

And that pattern continued. From 2011 through 2017, Moderna raised roughly $2 billion in venture funding, building out headcount, labs, and manufacturing capability long before it had anything to sell. To believers, it looked like constructing the factory before you’ve chosen which car models you’ll ship—because the factory was the point.

To everyone else, one question kept getting louder: when would theory finally become reality?

IV. The IPO & The Proving Ground

By late 2018, Moderna had been at this for eight years—spending heavily, expanding aggressively, and talking like a company that already belonged in the top tier of biotech. Its pipeline sprawled across vaccines and therapeutics for targets ranging from influenza and Zika to rare genetic diseases. It had big-pharma partners. It had government backing. What it didn’t have was the one thing public markets ultimately demand: undeniable proof in people, at scale, that the platform worked.

Then Moderna stepped onto the biggest stage it had ever faced.

In December 2018, Moderna went public in what was, at the time, the largest biotech IPO in history, raising about $621 million by selling 27 million shares at $23 each. When the stock started trading on December 7, the company debuted at a valuation of roughly $7.5 billion.

The sheer size of the offering was the point. Moderna wasn’t trying to fund a single moonshot program. It was asking investors to buy into the idea that one core technology—mRNA as a programmable medicine—could generate an entire portfolio of products over time. As CFO Lorence Kim put it, the return wouldn’t come from “one drug singly advancing by itself to approval,” but from a technology pushed forward, repeatedly, into many shots on goal.

Wall Street’s reaction was a reminder of how strange that pitch still sounded in 2018.

The IPO set a record, but the stock dropped sharply on its first day of trading—nearly 20% by Friday afternoon—wiping out a huge chunk of market value almost immediately. The message from the market wasn’t subtle: yes, the story is big, but the evidence is thin.

And the skeptics had plenty to cite. mRNA medicines were still early in clinical development. There were few human studies demonstrating clear efficacy. Moderna itself had only one mRNA candidate—aimed at myocardial ischemia—that had reached Phase 2. Even Moderna’s own filings acknowledged the core risk: it wasn’t yet clear whether mRNA drug processes would work reliably, or whether they’d be safe. On top of that, regulators like the FDA hadn’t evaluated this kind of medicine before, which meant the pathway could be uncertain even if the science held up.

Still, the IPO did exactly what Moderna needed it to do: it bought time and scale. The company said the proceeds would go primarily toward drug discovery and clinical development, expanding manufacturing capabilities, and building the infrastructure to support the pipeline.

What followed wasn’t a single dramatic breakthrough. It was the grind Moderna had always promised—methodical progress, program by program.

In the years after the IPO, Moderna moved multiple vaccine candidates into clinical trials, including influenza and cytomegalovirus, or CMV. It reported positive Phase 1 data readouts across six prophylactic vaccine programs, including H10N8, H7N9, RSV, chikungunya virus, hMPV/PIV3, and CMV.

None of this made Moderna a household name. There was no blockbuster product, no instant vindication. But these studies mattered for a different reason: they were accumulating proof points that the platform could be translated into humans. The company was showing, step by step, that it could deliver mRNA safely, get human cells to produce the intended proteins, and trigger measurable immune responses.

It also revealed something important about the original vision. Vaccines weren’t the headline in 2010, but they became some of the earliest real-world tests Moderna could run. And complexity arrived faster than anyone expected. Combination therapies weren’t on the radar at the beginning either, yet many of Moderna’s candidates evolved to use combinations of mRNAs—multiple encoded messages in a single shot—to make more complex proteins.

By early 2020, Moderna had cleared a crucial bar: its technology could work in humans.

What it still hadn’t done was deliver the kind of breakthrough product that would justify the valuation, the burn, and a decade of belief.

That test was coming—and it was about to arrive at the speed of a viral sequence.

V. The Crucible: Operation Warp Speed & The Race for a Vaccine

On January 11, 2020, Chinese scientists published the genetic sequence of a novel coronavirus linked to a growing outbreak in Wuhan. It was a Saturday. For most of the world, it was just another alarming headline. For Moderna, it was the moment their entire company had been built around.

They didn’t need vials of virus shipped across borders. They didn’t need to grow anything in eggs. They needed one thing: the code.

Within days, Moderna was moving. On January 13, 2020, the NIH’s Vaccine Research Center and Moderna’s infectious-disease team finalized the vaccine sequence they wanted to make—and Moderna immediately mobilized toward clinical manufacturing.

Noubar Afeyan later described the pivot as almost surreal in its speed. On January 21—his daughter’s birthday—he got a call from Stéphane Bancel, who was in Davos for the World Economic Forum. Public-health leaders there had been pushing Moderna to take a shot at a vaccine. Afeyan’s takeaway was blunt: “We literally decided overnight to try and do this.”

Then the platform did what it was supposed to do.

On February 24, 2020, Moderna delivered the first doses of its COVID-19 vaccine candidate to the NIH for testing. And on March 16, 2020, the first Moderna shot went into a volunteer’s arm in Seattle.

From sequence to first human dose: 63 days.

Bancel was explicit about what that speed really represented. Moderna didn’t move fast because it got lucky. Moderna moved fast because it had spent a decade and more than $2 billion building a system that could move fast. Traditional vaccine development is often a years-long slog—grow the pathogen, purify proteins, build specialized manufacturing, iterate. Moderna’s process was different. When the SARS-CoV-2 sequence went public, their scientists recognized similarities to the MERS work they’d already done and pivoted quickly.

This was the “software of life” idea made real. As Bancel put it, mRNA is information. If you can deliver it and manufacture it reliably, you can reuse the same underlying technology again and again. “The way we make mRNA for one vaccine is exactly the same way we make mRNA for another vaccine,” he said. In other words: copy, paste, ship.

But designing a vaccine quickly and proving it works in tens of thousands of people are two very different kinds of hard. A Phase 3 trial would be enormous. Manufacturing at global scale would be even harder. And doing both at once—before you even know if the vaccine works—would require a level of capital that could break a normal biotech.

That’s where the U.S. government entered the story.

On April 16, 2020, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services awarded Moderna $483 million to support its vaccine candidate, which had begun Phase 1 trials on March 16 and received fast-track designation from the FDA. Moderna said the funding would support late-stage development and help scale manufacturing. In July, Moderna announced a further commitment of $472 million.

In total, Moderna received $955 million from BARDA, an office within HHS, and the U.S. government provided $2.5 billion in total funding for Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine.

This was the logic of Operation Warp Speed: fund manufacturing before efficacy is proven. Under normal rules, you don’t build the factory until you know the product works. Warp Speed flipped that. If the vaccine failed, taxpayers would eat the cost. If it worked, doses would already be waiting.

The Phase 3 trial began on July 27, 2020: more than 30,000 participants across roughly 100 sites in the United States. For months, the world waited as data quietly accumulated—case by case, chart by chart—while hospitals filled and death tolls climbed.

Then, on November 16, 2020, Moderna released the headline the world had been desperate for.

Preliminary Phase 3 results showed the vaccine was more than 94% effective in preventing COVID-19, a result Bancel called a “game changer.” The primary analysis put efficacy at 94.1%, with 11 cases in the vaccinated group versus 185 in the placebo group.

That number landed like a thunderclap. The FDA’s bar for authorization had been 50%. Seasonal flu vaccines often land somewhere around the middle of that range. Moderna’s result wasn’t just above the threshold—it was in a different category. And the trial data pointed to something even more important: protection against the worst outcomes. The vaccine appeared 100% effective against severe disease, with all 30 severe COVID-19 cases occurring in the placebo group.

Bancel summed it up in a statement: the data confirmed the vaccine’s ability to prevent COVID-19 disease and, critically, to prevent severe disease—offering “a new and powerful tool that may change the course of this pandemic.”

On December 18, 2020, the NIH–Moderna vaccine was authorized by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for emergency use.

From genetic sequence to emergency authorization: less than a year.

For Moderna, it was the ultimate proof point. A decade of spending, skepticism, secrecy, and platform-building had culminated in a vaccine that would help save millions of lives. The bet that medicine could be programmed had finally been validated—on the biggest, most unforgiving stage imaginable.

VI. Playbook: The "Software of Life"

Moderna’s COVID-19 triumph wasn’t just a medical breakthrough. It was the moment a very specific strategy—one that had looked reckless for years—suddenly made perfect sense. If you’re trying to decide whether Moderna was a one-off pandemic winner or the start of something bigger, you have to understand the playbook.

Platform Over Point Solutions

Most biotechs live and die by one or two lead programs. That’s the standard logic: trials are brutally expensive, regulators are unforgiving, and focus increases the odds that at least one shot crosses the finish line.

Moderna did the opposite. It didn’t bet on a single drug. It bet on a system—a repeatable way to design, manufacture, and deliver mRNA that could, in theory, instruct the body to make almost any protein.

In traditional vaccine development, every new target tends to mean a new, custom-built process. Moderna was chasing something closer to redeployable infrastructure. As Afeyan put it, the advantage of a platform is the ability to “quickly redeploy” once it’s established—especially for vaccines, where a new viral sequence can become a new product candidate.

That’s the core of “programmable” medicine. Corbett and Bancel described it as “plug and play.”

But that phrase can make it sound easier than it is. The hard part—the part Moderna spent years grinding on—is delivery. “The devil is absolutely in the details as far as LNPs are concerned,” Ciaramella said. The point, though, is what happens after you’ve done that work: once an LNP system and a manufacturing process are tuned for a job, you can often swap in a new mRNA with far less rework than a traditional biotech would face. That reusability is the engine.

Embracing the "Un-Biotech" Model

Moderna didn’t just take an unconventional approach to science. It took an unconventional approach to making the science real.

In July 2018, the company opened a GMP clinical development manufacturing plant in Norwood, Massachusetts. The 200,000-square-foot facility was built to produce materials for pre-clinical, Phase 1, and Phase 2 programs. It was packed with advanced equipment—machines and robotic handlers designed to make the process more automated, more consistent, and more scalable.

That philosophy set Moderna apart from much of biotech manufacturing, which often looks closer to craftwork than mass production. mRNA, by contrast, is produced through a process that’s closer to chemical synthesis—more predictable, more standardized, and far more compatible with automation and tight process control.

Strategic Capital Allocation

Another part of the playbook was financial—and it was audacious.

Moderna was willing to raise enormous amounts of capital long before it had an approved product. Before the IPO, the company had raised about €1.6 billion (around $1.8 billion) in private funding.

That wasn’t an accident. A platform strategy is capital-intensive by design: you’re investing in basic science, manufacturing capability, and multiple clinical programs at the same time. Traditional biotech investors often struggled with that sprawl because it was hard to value in the usual way. Moderna wasn’t trying to be valued in the usual way. It was trying to build advantages that would be difficult for anyone else to recreate.

Narrative as a Moat

Finally, Moderna didn’t just build a platform. It sold a story that made the platform investable.

For years, the company framed itself less like a drug developer and more like a technology company that happened to make medicines. The “software of life” metaphor landed with investors who had watched platform businesses dominate in tech, where the real power is the underlying system, not any single product.

Afeyan has described Flagship’s method as starting with belief before proof—using what he called a leap of faith to work backward into hypotheses you might never reach if you demanded full evidence upfront: “We choose to start with a leap of faith… But we start by asking questions. If you work backwards, it gives you hypotheses you might never have had.”

That narrative mattered because Moderna spent years in a world where skepticism was rational. In those “stealth mode” years, when outside observers didn’t have much public data to point to, the story helped keep capital, talent, and partners flowing. And by defining Moderna as a platform, not a handful of individual drug bets, the company could survive setbacks in specific programs without collapsing the overall thesis.

The takeaway is simple: Moderna’s success wasn’t an accident. It was the payoff of deliberate choices—building a reusable engine, funding it aggressively, and selling a coherent vision long before the world had proof. The question now is whether that engine can keep producing hits after the pandemic.

VII. Analysis & The Bear vs. Bull Case

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry: High

Moderna plays in one of the most unforgiving arenas in business: vaccines and biotech, where competitors are global, capital is abundant, and the winners tend to compound advantages fast.

Even within the narrow mRNA lane, Moderna has a peer that proved the same thesis at the same moment. The first two COVID-19 vaccines authorized were both mRNA: Moderna’s mRNA-1273 and Pfizer/BioNTech’s BNT162b2. Pfizer and BioNTech remain a formidable rival, with deeper pockets and more established distribution relationships. Zoom out beyond mRNA, and Moderna is also facing traditional vaccine powerhouses—GSK, Sanofi, Merck—companies that have spent decades building sales channels, manufacturing muscle, and institutional trust.

You can see the squeeze most clearly in RSV. Moderna’s RSV vaccine, mResvia, has struggled to break through in a crowded market, with Moderna reporting just $2 million in mResvia sales in the third quarter of 2025.

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate to Low

The field is busier than it was a decade ago, but it’s still hard to enter in a meaningful way. mRNA isn’t just an idea; it’s a stack of capabilities—specialized manufacturing, deep lipid nanoparticle formulation expertise, and a thicket of patents. Building that from scratch takes years, and it takes billions.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High

Moderna’s biggest customers are governments and large healthcare organizations buying in bulk. They’re sophisticated, price-sensitive, and perfectly willing to run competitive processes that push suppliers against one another. In vaccines, that means pricing power often sits with the buyer, not the innovator.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate

mRNA production depends on specialized inputs: lipids for nanoparticle formulation and nucleotides for mRNA synthesis. Consistent LNP manufacturing has been a known bottleneck, and sourcing the materials to make those particles can limit how many doses can realistically be produced—especially in surge conditions like COVID.

Threat of Substitutes: Moderate

mRNA competes with plenty of “good enough” alternatives: traditional vaccine approaches, antivirals, and other platforms like protein subunit vaccines (including Novavax). In the seasonal respiratory market, the long-term reality is likely a mix of technologies all fighting for share.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework

Process Power

Moderna’s strongest defensible edge is how it works. Over years, it built a refined, scalable process to design and manufacture mRNA medicines—closer to a repeatable production system than a one-off R&D project. The company’s “kit” approach, where the mRNA sequence is the main thing that changes, enables speed and iteration that are difficult to replicate without living through the same long learning curve. That’s real process power: hard-earned capability embedded in the organization.

Cornered Resource

Moderna also has meaningful intellectual property around mRNA technology and lipid nanoparticle delivery. That IP matters because it can raise barriers for competitors—or at least raise the cost of doing business.

But it’s not a clean moat. Patent disputes have become a persistent cloud over the category. Moderna has ongoing legal cases in multiple countries against Pfizer and BioNTech, alleging the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine infringes Moderna’s mRNA vaccine patents.

And the fight isn’t one-directional. In November 2024, GSK sued Moderna in U.S. federal court in Delaware, seeking unspecified royalties and alleging that Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine and RSV vaccine mResvia infringe GSK patents related to mRNA technology.

Scale Economies

As an early mover at scale in mRNA vaccine production, Moderna built deep manufacturing know-how. Still, scale economies here don’t look like semiconductors, where volume can create brutal cost advantages. And in practice, Pfizer/BioNTech has shown it can manufacture at comparable scale, which limits how much “first mover” production advantage Moderna can bank on.

The Bull Case

The bull case starts with a simple claim: Moderna is still being valued and discussed like a COVID company, when it’s trying to be something else entirely.

Bulls argue the pandemic didn’t create Moderna—it revealed it. COVID was the proof of concept for an mRNA platform that can be redeployed across respiratory vaccines, latent and other vaccines, precision immunotherapies, and rare disease therapeutics.

Oncology is the most exciting upside. Moderna and Merck’s personalized cancer vaccine, mRNA-4157/V940, in combination with Keytruda, showed a statistically significant and clinically meaningful reduction in the risk of disease recurrence or death versus Keytruda alone in stage 3/4 melanoma patients at high risk of recurrence after complete resection.

Bulls also point to product design that plays to Moderna’s core advantage: multiplexing and iteration. With Pfizer hitting a stumbling block, Moderna’s combination COVID-19/influenza vaccine, mRNA-1083, could be first to market. In June, Moderna reported Phase III results showing mRNA-1083 produced a strong immune response against both COVID-19 and influenza—making Moderna the first and only company to date to post positive Phase III results for a combined COVID-19/flu vaccine.

And there’s the company’s own stated ambition. As Bancel put it: “In 2025, we remain focused on driving sales, delivering up to 10 product approvals through 2027, and expanding cost efficiencies across our business.”

If that happens, COVID becomes the first act—not the whole story.

The Bear Case

The bear case is equally straightforward: Moderna may be a platform company in theory, but in the market it has still behaved like a single-franchise business—and that franchise has been shrinking fast.

Moderna’s revenue for the twelve months ending September 30, 2025 was $2.232 billion, down 56.07% year-over-year. Annual revenue was $3.236 billion in 2024, down 52.75% from 2023. And 2023 revenue was $6.848 billion, down 64.45% from 2022.

With declining sales comes an uncomfortable second-order effect: the company has to fund a big pipeline while its core cash engine weakens. Cash, cash equivalents, and investments fell from $13.3 billion at December 31, 2023 to $9.5 billion at December 31, 2024, a decline Moderna attributed largely to the full-year operating loss.

Then there’s execution risk in the pipeline itself. Moderna recently announced that, despite growing scientific understanding of CMV, its CMV program failed to meet primary efficacy endpoints for congenital CMV. Moderna said it would discontinue development of the CMV vaccine for that indication.

Cost discipline is tightening too—and not always by choice. Moderna cut programs including an RSV shot for infants and two early cancer vaccines. It estimated those and other reductions would lower anticipated R&D spending by $4 billion from 2025 to 2028, taking the expected total down from $20 billion to $16 billion.

The company has also revised guidance downward multiple times. In third-quarter 2025 earnings, Moderna reported $1 billion in revenue, down roughly 45% from the same quarter a year earlier, and it lowered the top end of its 2025 revenue outlook to a range of $1.6 to $2 billion (from a prior range of $1.5 to $2.2 billion).

The bear view is that the platform is real—but the business model may not be self-sustaining without another blockbuster soon.

Key Metrics to Watch

For anyone trying to track whether Moderna is becoming an enduring pharma company or reverting to a post-pandemic downcycle story, two signals matter most:

1. Non-COVID Revenue Growth Rate: The clearest tell is whether Moderna can build meaningful revenue outside COVID. Moderna reported $15 million in mRESVIA sales in the fourth quarter of 2024, and $25 million for full-year 2024. Watching RSV uptake—and eventually flu and oncology revenue—will show whether the platform is translating into durable commercial franchises.

2. Cash Burn Rate and Path to Breakeven: The second tell is runway. CFO Mock said, “In just 2 years, we expect to reduce our cash cost by approximately 50% from nearly $9 billion in 2023 to $4.6 billion in 2025.” With $9.5 billion in cash at the end of 2024 and a target of breakeven in 2028, the pace of cash consumption will determine whether Moderna can afford the time it needs for its next wave of products to mature.

Legal and Regulatory Considerations

Moderna’s legal exposure is not theoretical—it’s active, ongoing, and potentially expensive.

In February 2023, Moderna agreed to pay $400 million to the National Institutes of Health, Dartmouth College, and Scripps Research to settle a dispute over rights to a chemical technique used in the vaccine.

Beyond that, the lawsuits involving GSK and the continuing disputes with Pfizer/BioNTech remain material overhangs. Depending on outcomes, they could lead to significant royalties or settlements—costs that would matter even more in a world where Moderna’s COVID-era revenue tailwinds have faded.

VIII. Epilogue: From Pandemic Savior to Enduring Pharma Giant?

As 2025 draws to a close, Moderna is back at a familiar place: an inflection point. The pandemic that made it famous has faded for most people, and with it the once-unthinkable demand for COVID-19 vaccines. Moderna became a global name by delivering one of the first COVID shots and earning billions in the process. But the hangover from that success is real. COVID vaccine sales have fallen sharply from their peak, and Moderna has yet to produce a second franchise with the same gravitational pull.

Management’s plan now centers on three fronts.

First: build a durable respiratory business. Moderna is pushing its seasonal flu vaccine (mRNA-1010) and its combined flu/COVID vaccine (mRNA-1083) toward potential approval. In June 2025, Moderna reported positive Phase 3 results for mRNA-1010, showing superior relative vaccine efficacy—26.6% higher than a licensed standard-dose seasonal influenza vaccine—in adults age 50 and older.

Second: go on offense in oncology, alongside Merck. Moderna and Merck expanded clinical studies of their individualized neoantigen therapy (INT) into additional tumor types, and the Phase 3 trial in the adjuvant melanoma setting completed enrollment in 2024.

Third: press into rare diseases, where the promise of “any protein, on demand” is most literal. Moderna’s investigational therapy for MMA (mRNA-3705) was selected by the FDA for the Support for Clinical Trials Advancing Rare Disease Therapeutics (START) pilot program. The FDA and Moderna agreed on a pivotal study design, and Moderna expected to begin a registrational study in 2025.

To make any of that work, Moderna also has to do something it didn’t have to worry about in 2021: operate like a company with constraints. The push for financial discipline is already showing up in the numbers. Over the four quarters from Q4 2024 through Q3 2025, Moderna delivered a $2.1 billion improvement in costs across cost of goods, SG&A, and R&D versus the prior four quarters.

So what is Moderna’s lasting legacy?

From one angle, it’s already cemented. Moderna helped deliver a vaccine that prevented millions of deaths and proved that mRNA therapeutics could work in humans at massive scale. “Within 1 year after the emergence of this novel infection that caused a pandemic, a pathogen was determined, vaccine targets were identified, vaccine constructs were created, manufacturing to scale was developed, phase 1 through phase 3 testing was conducted, and data have been reported,” investigators wrote.

From another angle, Moderna still looks like the opening act of a longer story. Derrick Rossi put the ambition in first-principles terms: “DNA makes RNA makes protein makes life. So wherever there's life, which is in all of disease pathology, mRNA could potentially play a role. We had our fingers on one of the really key levers of essentially all aspects of disease, all aspects of life.”

The software-of-life idea has been validated once, in the most public way imaginable. The harder question is what happens when the world isn’t throwing unlimited demand at a single product—when the work is slower, the biology messier, and the commercial wins have to be earned one indication at a time.

Back at the beginning, Robert Langer remembers telling his wife in 2010, “It's going to be the most successful biotech company in history.” No one knew COVID was coming. But COVID compressed the timeline and forced the ultimate demonstration. Now Moderna is running multiple clinical trials not only for COVID, but also for cancer, heart disease, and rare diseases.

The bet that started in a Cambridge lab in 2010 changed public health in 2020. Whether it changes medicine over the next decade depends on whether Moderna can prove its pandemic triumph wasn’t a singular event, but the first clear signal of a repeatable engine—that the code of life really can be rewritten on demand.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music