Morningstar: The Architects of the Moat

I. Introduction: The "Consumer Reports" of Capital

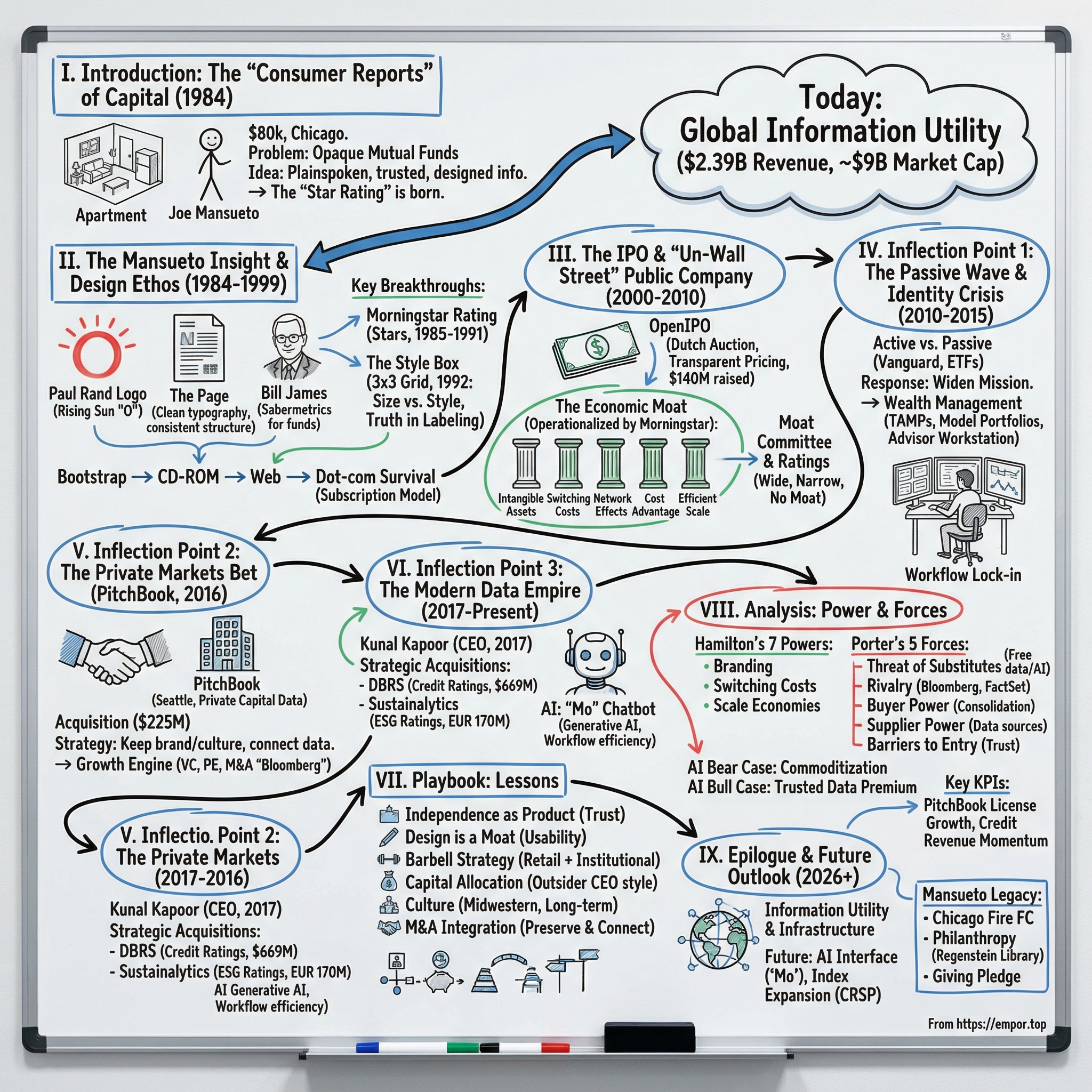

In 1984, a 27-year-old analyst named Joe Mansueto sat in his one-bedroom Chicago apartment surrounded by mutual fund prospectuses. They were brutal to read: dense, jargon-packed, and, to the average person, basically unusable. And maybe that was the point. If investors couldn’t see what they were buying, it was a lot easier to charge big front-end loads and ongoing fees without too many questions.

Mansueto’s idea was simple, almost naïve in the best way: what if someone treated mutual funds the way Consumer Reports treated toasters? What if investing information could be plainspoken, comparable, and trustworthy? And, because Mansueto cared as much about how information felt as what it said, what if it could be beautifully designed too?

He started Morningstar from home with $80,000, aiming to bring institutional-quality research to individual investors. Four decades later, that apartment project had turned into something far larger: a company generating about $2.39 billion in trailing twelve-month revenue as of late 2025, up from $2.27 billion in 2024.

That’s the scale. The weird part is the identity.

Everyone recognizes the Morningstar star rating—those five little symbols that sit beside mutual funds and ETFs across the financial world. But far fewer people can answer the obvious follow-up: what is Morningstar, actually? A media brand like Forbes or Bloomberg? A software provider like FactSet? An asset manager like Fidelity? A data company like S&P Global?

In practice, it’s a bit of all of that—and that’s exactly why it’s so interesting. Morningstar has become something closer to an information utility: a company whose data and frameworks are so baked into how investing gets done that they function like infrastructure. When your advisor pulls up a fund list, Morningstar is often behind the numbers on the screen. When an institution evaluates private-market managers, there’s a good chance they’re using PitchBook, which Morningstar owns. When a European bank needs a credit opinion on a structured product, DBRS Morningstar may be the rating agency in the mix.

This story matters now for three reasons. First, the industry shift from active to passive investing should, on paper, have been an existential threat to a business famous for rating active managers. Yet Morningstar found ways to adapt. Second, more and more value creation has moved into private markets, and the PitchBook acquisition put Morningstar right in the center of that gravity shift. Third, in a world flooded with questionable financial content—and now AI-generated noise—trusted, independent data and research starts to look less like a nice-to-have and more like a competitive advantage.

By 2024, Morningstar’s consolidated revenue was roughly $2.0–$2.1 billion, with PitchBook and DBRS Morningstar emerging as major growth engines. Today it operates across data, ratings, and wealth management, with a market capitalization around $9 billion.

So how did a typographically obsessed investor, working from a Chicago apartment, end up building one of the most influential institutions in modern finance? Let’s go back to the beginning.

II. The Mansueto Insight & The Design Ethos (1984–1999)

Morningstar’s origin story starts with its founder, but not in the way most finance stories do. Joe Mansueto wasn’t minted on Wall Street. He grew up in Munster, Indiana, the son of Mario Mansueto, an Italian doctor. No dynasty connections. No insider pipeline. He went to Munster High School, then earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in business from the University of Chicago.

Before Morningstar, Mansueto worked as a securities analyst at Harris Associates, the firm behind the Oakmark funds. It was a front-row seat to how professionals judged money managers: disciplined, comparative, and grounded in data. It was also a lesson in how little of that world made it to regular people trying to save for retirement. In the early 1980s, mutual funds were exploding in popularity, but transparency wasn’t keeping up. Investors were paying around 0.8% annually on average—often with front-end loads on top—and many had only a foggy sense of what they actually owned.

Mansueto didn’t just think that was bad. He thought it was fixable. And he brought an unlikely weapon to the fight: design.

Finance, historically, has treated presentation like decoration. Mansueto treated it like infrastructure. He was deeply influenced by Paul Rand, the graphic designer behind iconic logos for IBM, ABC, and UPS. In a move that says everything about early Morningstar, Mansueto convinced Rand to design Morningstar’s logo. The “O” hints at a rising sun, a nod to the company’s name—pulled from the last line of Thoreau’s Walden: “The sun is but a morning star.”

That design obsession wasn’t vanity. It was a strategy for trust. Morningstar’s signature format—simply called “The Page”—took dense, decision-critical fund information and organized it with clean typography and consistent structure. It first appeared in Morningstar’s flagship biweekly mutual fund publication, Morningstar Mutual Funds. Decades later, it still lives on in digital form inside investor tools. While fund prospectuses often felt like they were written to hide the ball, Morningstar’s layout made the ball easier to find.

The other key influence was even less expected: Bill James, the baseball statistician who helped pioneer sabermetrics. James took a sport run on gut feel and gave it a rigorous statistical language. Mansueto wanted to do the same for mutual funds—especially in an era when brokers could steer investors toward whatever paid the best commission.

The early years were lean and stubbornly bootstrapped. Mansueto started with about $80,000 and worked out of a small office. Data didn’t arrive clean, neatly packaged, and digital. It had to be collected, standardized, checked, and rechecked. And Morningstar had to persuade fund companies—and the broader industry—that an independent rater had a right to exist. The way through was persistence, and an almost obsessive commitment to data quality.

Then came the product breakthroughs that didn’t just build Morningstar—they changed how investing is discussed.

Between 1985 and 1991, Morningstar worked to systematically digitize mutual fund data. Around the same time, it introduced what would become its most recognizable invention: the Morningstar Rating. For advisors and everyday investors, it became a quick shorthand for performance and risk—an easy-to-grasp signal in a market full of noise. Subscriptions grew into the tens of thousands, and the little stars began spreading far beyond Morningstar’s own pages.

But the deeper revolution arrived in 1992 with the Style Box, developed by Morningstar’s Don Phillips and John Rekenthaler. It’s a simple 3x3 grid. The vertical axis maps a fund by company size—small, mid, large. The horizontal axis maps investment style—value, blend, growth. Industry insiders dubbed it the “tic-tac-toe box,” which is fair. It looks obvious now. That’s the point. Great frameworks feel inevitable in hindsight.

Before the Style Box, comparing funds was a marketing word game. A manager could call a strategy “growth at a reasonable price” or “concentrated value,” and those labels could mean almost anything. Morningstar imposed a taxonomy tied to actual holdings. If a fund owned large-cap growth stocks, it landed in large-cap growth—no matter what the brochure claimed. And once you could compare like with like, a lot of supposed brilliance started to look more like style-driven risk. The curtain moved. More light got in.

From there, Morningstar expanded the distribution, not the mission. It rolled out CD-ROM products and early web offerings, launched Morningstar.com for individual investors, and created Advisor Workstation for professionals. Coverage widened beyond mutual funds into separate accounts and ETFs. International offices opened in the UK, Australia, Japan, and Canada.

Then came the dot-com era—an era that rewarded attention more than economics. Plenty of financial media brands chased eyeballs and advertising: TheStreet.com, MarketWatch, and a long list of trading forums that felt exciting right up until they didn’t. Morningstar took the slower path. It charged for subscriptions. When the bubble burst in the early 2000s, that decision mattered. Morningstar survived while many competitors ran out of money and disappeared.

By the end of the 1990s, Morningstar had done something rare: it had turned a mission—investment transparency—into a set of tools the industry couldn’t stop using. And with that foundation in place, the next phase wasn’t just growth. It was a reinvention: a company built on independence, stepping onto the public stage without giving up what made it different. Mansueto had served as CEO from 1984 to 1996, and he would return to the role later, in 2000—right as the market was recalibrating and Morningstar was lining up its next transformation.

III. The IPO & The "Un-Wall Street" Public Company (2000–2010)

By 2005, Morningstar had proved something most financial idealists never manage to prove: independent research could be a real, durable business. The brand was trusted, the subscription engine worked, and the company had expanded overseas. Now came the harder question—how do you tap public markets without letting Wall Street rewrite your incentives?

Joe Mansueto’s answer was, predictably, not the usual answer.

Instead of a traditional book-built IPO—run by the big investment banks, with shares quietly parceled out to favored institutional clients and a first-day “pop” that often rewards insiders more than the company—Morningstar went with WR Hambrecht + Co.’s OpenIPO process.

OpenIPO is a modified Dutch auction. Investors bid for shares, allocations are made more impartially, and everyone who wins pays the same final price. Google had used a version of it in 2004, which made the approach less fringe—but it was still rare. For Morningstar, it wasn’t a stunt. It was the product philosophy applied to capital markets: transparent pricing, fewer backroom dynamics.

The IPO raised $140 million and valued Morningstar at about $1.5 billion. The stock priced at $18.66, traded up through the day, and closed at $20.05. And importantly, the shares sold largely served as an exit for early investor SoftBank—meaning Morningstar could go public without contorting the business just to satisfy a flashy fundraising narrative.

Once public, Morningstar didn’t suddenly become a hype machine. It became more Morningstar: methodical, acquisitive, and focused on turning frameworks into infrastructure.

In 2006, it acquired Ibbotson Associates for $83 million, bringing in deep expertise in asset allocation and historical market data. The deal expanded Morningstar beyond fund “report cards” into capital markets research that could sit underneath portfolio construction—the kind of capability professionals actually build practices around.

But the most consequential development in this era wasn’t a deal. It was an idea—formalized, systematized, and turned into a product: the economic moat.

Warren Buffett had popularized the metaphor for decades: great businesses have defenses that keep competitors out and allow them to earn excess returns over long periods of time. Morningstar took that concept and operationalized it. Not just as a catchy phrase, but as a repeatable research discipline with clear categories and oversight.

In Morningstar’s framework, a moat is a structural advantage that allows a company to sustain economic profits—earning returns on invested capital above its cost of capital—for years. Analysts anchored those advantages in five sources: intangible assets, switching costs, network effects, cost advantage, and efficient scale. They also weighed whether there were meaningful risks that could destroy value, including ESG-related threats, disruption, and other long-term vulnerabilities.

To keep the rating consistent, Morningstar set up a moat committee—about 20 senior analysts across sectors and geographies—tasked with overseeing the calls. Companies were tagged as wide moat, narrow moat, or no moat. Wide moat meant durable advantages expected to hold for 20 years or more; narrow moat implied at least a decade; no moat meant there was no enduring edge.

This wasn’t academic taxonomy. It became proprietary intellectual property—a language investors could use, and a dataset institutions could subscribe to. VanEck later licensed the approach to build the Morningstar Wide Moat Focus ETF (MOAT), a clean example of Morningstar’s real superpower: turning trusted research into something other businesses can plug into.

At the same time, Morningstar’s economics were quietly shifting under the hood. Print and retail subscriptions still mattered, especially for the brand, but the growth engine was moving to software and workflow. Products like Advisor Workstation and Morningstar Direct embedded Morningstar inside the day-to-day routines of financial professionals. And once you’re in the workflow, you’re not a magazine you can cancel—you’re infrastructure.

The takeaway of the 2000s is that Morningstar didn’t use its IPO to become more “financial.” It used it to become more foundational: expanding its capabilities, codifying its most powerful ideas, and migrating the business from selling insight to selling systems.

IV. Inflection Point 1: The Passive Wave & Identity Crisis (2010–2015)

By 2010, an uncomfortable question was getting harder to ignore: if active management was being commoditized, who still needed Morningstar?

The momentum was obvious. Vanguard and BlackRock were pulling in assets at a blistering pace. Index funds, with their low fees, were beating most active managers over long stretches. Jack Bogle’s core claim—that, after costs, most stock pickers won’t outperform—was no longer just a debating point. It was showing up in the flows.

For Morningstar, this wasn’t an abstract industry trend. It cut right at the company’s center of gravity. Morningstar’s original job was to help people choose the best active managers. The star rating summarized risk-adjusted performance. The Style Box revealed what managers actually owned. Analyst reports explained who had an edge and why.

But if the “right” answer for many investors was simply, buy the cheapest S&P 500 index fund and move on, what was left to rate?

Morningstar’s response was to widen the mission without abandoning it. Instead of only helping investors pick funds, it leaned into helping professionals run practices. Products like Advisor Workstation and Morningstar Direct didn’t just deliver research—they embedded Morningstar into the daily workflow of financial advisors, which pushed the business toward enterprise subscriptions and away from being perceived as just a retail publishing brand.

Then came the bigger shift, and it was a quiet one: Morningstar moved from watcher to doer. Through Morningstar Investment Management, it began managing money more directly—building model portfolios and offering turnkey asset management programs (TAMPs) for advisors who wanted to outsource investment decisions. Morningstar offered these investment management services through its registered investment advisor subsidiaries and, as of June 2016, had more than $185 billion in assets under advisement and management.

That created a new stream of recurring revenue tied to assets. It also created a new kind of scrutiny. If Morningstar was now competing for the same assets as the managers it evaluated, could it still be the neutral referee? Morningstar maintained that its research and investment management operations were independent, but the tension didn’t disappear—and critics were quick to point it out.

Even so, the pivot showed the company’s instincts were intact. Morningstar saw where wealth management was heading: fee-based advice, scalable model portfolios, and technology that let an advisor serve more clients without lowering standards. And it understood a second-order benefit: once an advisory practice is built around Morningstar Direct—client presentations, portfolio construction, standardized reporting—switching isn’t a simple “cancel subscription” decision. It’s rewiring the firm.

And the irony is that the rise of passive didn’t eliminate the need for analysis. It changed what “analysis” meant. Pure indexing grew, but so did smart beta, factor-based strategies, and, eventually, actively managed ETFs—areas where categorization, risk understanding, and clear comparative tools still mattered. Active management didn’t die. It evolved. Morningstar evolved with it.

V. Inflection Point 2: The Private Markets Bet (The PitchBook Acquisition)

By 2016, a structural shift in markets was getting hard to ignore. The U.S. had far fewer public companies than it did a couple decades earlier—down from more than 8,000 in the mid-1990s to roughly 4,000. Meanwhile, companies were staying private for longer. Businesses like Uber and Airbnb built enormous valuations before they ever rang an opening bell.

In other words: more of the economy’s most important value creation was happening off-exchange, inside venture capital and private equity. If Morningstar stayed focused only on public markets, it risked becoming expert in a shrinking slice of the game.

So Morningstar went shopping for a new dataset—and found the right one in a company it already knew well.

That year, Morningstar announced plans to acquire PitchBook Data, Inc. in a deal valuing PitchBook at $225 million. This wasn’t a cold start. Morningstar had been an investor in the Seattle-based company since 2009, already owned about 20% of it, and planned to pay roughly $180 million for the rest.

PitchBook, founded in 2007, had built a product that felt like Morningstar’s mission translated into a different universe: data, research, and tools for private capital markets—venture capital, private equity, and M&A—where information is famously hard to standardize and even harder to trust.

The timing of PitchBook’s birth was brutal. Gabbert launched the company right as the financial crisis hit—exactly when selling a product tied to dealmaking and private markets became a much tougher pitch. But the need never went away. If anything, the crisis era reinforced how valuable clean, structured information is when markets are stressed.

Morningstar’s relationship with PitchBook deepened over time. It provided $1.2 million of Series A funding in 2009, and then invested another $10 million in January 2016. By the time the acquisition came together later that year, Morningstar wasn’t guessing. It had watched the business up close for years.

And the business was working. PitchBook’s client count had more than tripled over the prior three years to more than 1,800. Sales bookings had been compounding at more than 70% annually over the five years ending December 31, 2015—growth that signaled not just demand, but workflow lock-in. Once a firm builds its deal pipeline, comps, and investment memos around a platform, it doesn’t switch lightly.

What made the acquisition truly transformative wasn’t only what PitchBook did. It was how Morningstar handled it.

Instead of absorbing PitchBook into Chicago and sanding down everything that made it effective, Morningstar let it stay PitchBook. The brand remained. The identity remained. John Gabbert stayed on as CEO. PitchBook kept operating with its Seattle culture intact, while Morningstar worked to connect the data and broaden distribution over time.

That approach was helped by continuity at the top. Morningstar president Kunal Kapoor—who would become CEO on January 1, 2017—had been on PitchBook’s board since 2012. He understood what made the business tick and could translate between the two worlds, which is often the difference between “strategic acquisition” on paper and real value in practice.

The strategic logic was pure Morningstar. Data and research were the company’s home turf. PitchBook expanded Morningstar’s coverage into private companies and private transactions, and it strengthened Morningstar’s push toward a truly multi-asset view of portfolios—one where public equities, funds, and private markets sit in the same analytical frame.

In the years that followed, the bet looked increasingly prescient. PitchBook grew into a major engine inside Morningstar’s results. In Q4 2024, it contributed $162.5 million to consolidated revenue, up 12.5% from the prior year. In Q1 2025, revenue was $163.7 million, up 10.9% reported and 11.1% organic. Over that same period, PitchBook Licenses rose 13.6% to 126,285, supporting the segment’s growth.

By then, PitchBook had effectively become the Bloomberg for VC, private equity, and M&A—a default system for professionals operating in the private side of the economy. And as institutions allocated more to alternatives and companies stayed private longer, that positioning stopped being a nice adjacency and started looking like a foundational pillar of what Morningstar could become next.

VI. Inflection Point 3: The Modern Data Empire (2017–Present)

In 2017, Joe Mansueto stepped into the role of executive chairman, and Morningstar began the next phase of its life: a founder-led company learning how to thrive with a new person in the CEO seat. That handoff is where a lot of great businesses wobble—either because the founder can’t stop steering, or because the successor can’t command the same trust, internally or externally.

Morningstar’s transition was steadier than most, in large part because Kunal Kapoor wasn’t a professional CEO parachuting in. He’d been inside Morningstar for two decades. He joined in 1997 as a data analyst and moved through roles across research and innovation, including director of mutual fund research. He was also part of the team behind the launch of Morningstar Investment Services, Inc.—which mattered, because it meant he understood both sides of the company’s identity: the independent rater and the builder of systems that professionals rely on.

Kapoor grew up in India, studied economics and environmental policy at Monmouth College, and earned an MBA from the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. But the most revealing detail about his fit with Morningstar is what first pulled him in. As a college student dabbling in investing, he read the Rekenthaler Report—John Rekenthaler’s sharp, opinionated writing that was less “mutual fund summary” and more crusade for investor transparency. Kapoor wasn’t just impressed by the analysis; he was hooked by the candor. That tone—plainspoken, slightly contrarian, allergic to marketing spin—was Morningstar’s culture in written form.

Steven Kaplan of Chicago Booth summed up why Kapoor got the job: “Kunal was chosen as CEO because he was an effective leader and manager—strategic, creative, and execution-oriented.” Kapoor and Mansueto continued to meet in person about twice a month and stayed in contact almost daily, but the relationship was intentionally structured to avoid the classic founder-shadow problem. “He could easily be looking over my shoulder, but he never does,” Kapoor said. “He has given the leadership team independence and backing to write Morningstar’s next chapter.”

That next chapter looked less like publishing and more like building a modern financial data empire—one that could compete in categories Morningstar had historically sat adjacent to.

The clearest statement came in credit ratings.

Under Kapoor, Morningstar made its largest acquisition ever: DBRS, the Canadian credit rating agency. Morningstar signed a definitive agreement to buy DBRS—then the world’s fourth-largest credit ratings agency—for $669 million. DBRS, founded in Toronto in 1976 as Dominion Bond Rating Service, gave Morningstar an immediate foothold in a market dominated by a small number of entrenched incumbents. The deal closed on July 2, 2019, and DBRS was integrated with Morningstar Credit Ratings to form DBRS Morningstar.

The strategic intent wasn’t subtle. This was Morningstar taking aim at the credit-ratings establishment—Moody’s and S&P, with Fitch as the distant third. DBRS Morningstar became the fourth-largest credit rating agency by global market share, at roughly 2%–3%. Just as importantly, it was one of only four credit rating agencies recognized by the European Central Bank as an external credit assessment institution, alongside S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch.

DBRS Morningstar now rates more than 4,400 issuers and 64,000 securities, with a strong position across Canada, the U.S., and Europe in multiple asset classes. For Morningstar, it fit the mission: more transparency, more independent opinions—just applied to credit risk instead of mutual funds.

Then came a second bet, aimed at a different kind of “rating”: ESG.

Morningstar announced an agreement to acquire Sustainalytics, a global provider of environmental, social, and governance ratings and research. Morningstar already owned about 40% of Sustainalytics, a stake it first acquired in 2017, so this wasn’t a blind leap. The deal included an upfront cash payment of about EUR 55 million, plus additional payments in 2021 and 2022 tied to a revenue multiple based on Sustainalytics’ 2020 and 2021 fiscal-year results. Based on the upfront consideration, Morningstar estimated Sustainalytics’ enterprise value at EUR 170 million. The acquisition closed on July 6, 2020.

More than 650 Sustainalytics employees joined Morningstar, along with the full executive team, bringing security-level and country-level ESG data, research, ratings, and products. The thesis was simple: “non-financial” factors—climate exposure, governance, supply chains—were becoming financially material. Or as Kapoor put it: “Modern investors in public and private markets are demanding ESG data, research, ratings, and solutions in order to make informed, meaningful investing decisions. From climate change to supply-chain practices, the nature of the investment process is evolving.”

But ESG also brought a new kind of volatility—less market-driven and more political. In the U.S., ESG faced growing backlash, and Morningstar Sustainalytics felt it. The decline in revenue was driven primarily by the ongoing streamlining of the licensed-ratings offering, lower revenues for ESG Risk Ratings (in part due to vendor consolidation), and softness in second-party opinions. At the same time, demand remained stronger in Europe. Morningstar now had to do something it hadn’t historically needed to do at this scale: navigate a politically charged product category while still presenting itself as the neutral, trusted party.

And then, naturally, the next frontier became the one every information business is running toward: AI.

Morningstar launched a beta version of a generative AI chatbot called Mo across Morningstar Investor, Research Portal, Direct, and Advisor Workstation. Built on the Morningstar Intelligence Engine—which pairs Morningstar’s investment research library with Microsoft’s Azure OpenAI Service—Mo was designed to surface and summarize Morningstar’s own independent insights in a conversational interface.

It wasn’t a random product demo. Morningstar had already teased Mo at the 2023 Morningstar Investment Conference, where Kapoor spoke with a digital avatar version of it on the main stage—signaling where they saw this going: AI that synthesizes research, automates repetitive work, and functions as in-product help for investors and advisors.

Morningstar reported productivity gains from Mo, including a 20% reduction in research time, a 50% cut in writing time, and a 65% decrease in editing errors—positioning it less as a novelty and more as a workflow upgrade.

Zooming out, you can see the shape of the modern Morningstar clearly now. It’s no longer “the mutual fund star rating company.” It’s a three-legged stool: Data products (Direct, PitchBook, core data feeds), Ratings (DBRS Morningstar and Sustainalytics), and Wealth Management (model portfolios and advisor platforms).

And the scale has kept moving. For the full year 2024, revenue increased 11.6% to $2.3 billion, with organic revenue up 11.8%. Morningstar Credit, PitchBook, and Morningstar Data and Analytics were the largest contributors to reported growth.

VII. Playbook: Lessons for Builders & Investors

So what do you take away from four decades of Morningstar? Not “how to pick funds,” but how to build something that people trust enough to build their livelihoods on.

Independence as a Product. In a financial world that often runs on “pay-to-play,” Morningstar’s refusal to accept payments for ratings wasn’t just a values statement. It was the core feature. The moment fund companies realized they couldn’t buy a better outcome, the output became believable. Over time, that credibility got embedded everywhere: in regulatory documents, advisor decks, and the mental shortcuts investors use to make decisions. Independence isn’t a slogan at Morningstar. It’s the moat.

Design is a Moat. Mansueto’s obsession with typography and layout wasn’t aesthetic indulgence. It was a way of making the truth usable. “The Page” took intimidating, messy fund data and turned it into something you could actually scan, compare, and understand. That same philosophy still shows up in Morningstar’s digital products today. Plenty of firms can collect data. Far fewer can present it in a way that earns trust and drives action.

The "Barbell" Strategy. Morningstar has always lived in two worlds at once: the DIY investor on Morningstar.com and Morningstar Investor, and the institutional power user on Direct, PitchBook, and DBRS. That sounds like a split personality until you see the flywheel. Retail reach creates familiarity, which supports premium positioning. Institutional-grade data and rigor, in turn, reinforces the credibility of the retail brand.

Capital Allocation. Morningstar has generally avoided issuing shares to fund growth. Instead, it has leaned on cash generation, targeted debt, buybacks, and selective acquisitions. In Q2 2025, for example, the company repurchased $112.0 million of its shares and paid $19.3 million in dividends. The pattern resembles the “Outsider CEO” playbook William Thorndike wrote about: treat capital like a scarce resource, and deploy it like an owner would.

Culture. There’s a distinctly Midwestern consistency to how Morningstar operates: high retention, mission-driven teams, and compensation that may not match New York or San Francisco, but works for Chicago. Even Mansueto’s personal choices reflect that long-term, values-first posture. As of December 2010, he was the only Chicagoan on the list of American billionaires pledging to give away half of their wealth through The Giving Pledge started by Warren Buffett. That kind of signal matters inside an organization built on credibility.

M&A Integration. PitchBook is the template. Instead of smothering what they bought, Morningstar kept what made PitchBook special—its brand, its Seattle culture, and John Gabbert’s leadership—while gradually connecting the underlying data and distribution. The point wasn’t to “integrate fast.” It was to preserve momentum. And the result was exactly what you’d hope: PitchBook didn’t stall after the acquisition; it became one of Morningstar’s fastest-growing engines.

VIII. The Analysis: Power & Forces

To understand Morningstar’s competitive position, it helps to run two classic lenses over the business: Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers and Michael Porter’s 5 Forces. Different frameworks, same goal—figure out what actually keeps competitors out, and what could still take Morningstar down.

Hamilton’s 7 Powers:

Branding: The Star Rating has become a cultural shorthand in investing. Morningstar originally introduced it as a simple starting point for evaluating funds—something that nudged investors to think beyond short-term performance. But over time, those five little symbols escaped Morningstar’s own products and became embedded across the industry. That kind of recognition can’t be bought in a quarter or built with a marketing blitz. It gets earned the slow way: consistency, independence, and decades of showing up with the same rules.

Switching Costs: Morningstar is hard to replace once it’s inside the workflow. If an advisor is building proposals in Morningstar Direct, using Morningstar categories in every client report, and training the whole firm on those tools, ripping it out isn’t just canceling a contract—it’s redoing how the practice runs. The same dynamic shows up in institutions using PitchBook for private-market diligence. When the platform is how you source deals, track comps, and build investment memos, switching means pain, downtime, and real operational risk.

Scale Economies: Collecting and cleaning investment data is a high fixed-cost game. Selling it, on the other hand, scales beautifully. Morningstar can spread the cost of covering hundreds of thousands of investment offerings across a large subscriber base, while each incremental license costs very little to deliver. A smaller competitor would face many of the same data-collection burdens without nearly as many customers to amortize them.

Porter’s 5 Forces:

Threat of Substitutes: The forever threat is free. Yahoo Finance, Google Finance, and countless other platforms provide “good enough” market data at a price that’s hard to beat: zero. Morningstar’s job is to stay meaningfully more valuable than what’s available for free—especially as AI tools make it easier to summarize public information quickly. If the user believes the free option is close enough, premium subscriptions get squeezed.

Rivalry: Morningstar competes in a brutal arena. Bloomberg is the titan—real-time data, a messaging network, and the kind of entrenched presence that becomes a career-long habit. Capital IQ, FactSet, and Refinitiv are deep, enterprise-grade competitors with strong institutional relationships. Morningstar’s differentiation has historically been fund expertise, its frameworks like the Style Box, and the trust built around its research. PitchBook extends that edge into private markets, where data is scarcer and workflows are even stickier.

Buyer Power: Advisors are consolidating, and consolidation cuts both ways. Large RIAs and aggregators can negotiate harder on per-seat pricing than an independent advisor ever could, which can pressure pricing over time. But consolidation also creates bigger, enterprise-style opportunities—firms that want standardized tools, consistent reporting, and a platform they can roll out across hundreds or thousands of users.

Supplier Power: Morningstar depends on data from exchanges, fund companies, and other third-party sources. Much of that information is commoditized, but unique or hard-to-source datasets can shift leverage to suppliers—especially in private markets, where disclosure is limited and information is often relationship-driven.

Barriers to Entry: Creating credible investment research isn’t just a software problem. It’s a trust problem. New entrants face the classic chicken-and-egg: without a track record, you don’t have credibility; without credibility, you can’t attract the customers and feedback loops that create a track record. AI could lower some mechanical barriers—summaries, screens, basic analysis—but it doesn’t automatically solve the trust layer. In finance, being wrong isn’t just embarrassing; it’s costly.

The Bear Case: AI Commoditization. If large language models can instantly analyze filings, compare funds, and generate coherent investment summaries, what happens to the value of human-written research? If “good enough” analysis becomes abundant and cheap, Morningstar’s differentiated insight risks getting pulled toward the commodity end of the spectrum over the long run.

The Bull Case: Trusted Data in an AI World. The flip side is that AI makes trust more valuable, not less. When content is cheap and plentiful, accuracy becomes the premium product. As Morningstar’s Head of Technology, Benjamin Barrett, put it: “Building a chatbot on that data looks like magic, but when you start peeling back the layers of the onion, you have to ask, is it actually accurate? Is it pulling the latest, greatest, most relevant data? Are our answers robust and complete?” That’s where Morningstar’s advantage shows up: vetted research, consistent frameworks, and proprietary datasets—especially PitchBook’s private-market information, which can’t simply be “generated.” It has to be gathered, verified, and maintained in markets where the truth isn’t posted publicly.

Key KPIs to Watch:

-

PitchBook License Growth and Net Revenue Retention: PitchBook remains a key growth engine. In Q1 2025, PitchBook licenses rose 13.6% to 126,285—an indicator not just of new sales, but of how deeply customers expand usage once PitchBook becomes part of the workflow.

-

Morningstar Credit Revenue Growth: Morningstar Credit has been a strong contributor, with revenue rising 21.1% on a reported basis in certain quarters. Credit ratings is a scale business—once you have distribution and credibility, incremental growth can be meaningfully profitable—so sustained momentum here matters disproportionately to the overall model.

IX. Epilogue & Future Outlook

The Morningstar of 2026 bears only superficial resemblance to the apartment startup of 1984. It now operates across more than 30 countries, employs roughly 12,000 people, and produces data and ratings that shape investment decisions at massive scale.

The next shift is about interface as much as information. In 2023, Morningstar pulled artificial intelligence out from behind the scenes with Mo, its AI assistant. Instead of digging through menus and PDFs, users can ask a question and get a direct, concise answer pulled from Morningstar’s underlying databases. As Mo gets woven into Direct and Morningstar’s other platforms, the bet is clear: the value isn’t just having trusted data. It’s making that data instantly usable.

Morningstar is also still expanding the pipes. Its planned acquisition of the Center for Research in Security Prices would strengthen Morningstar’s position in indexes—adding scale for Morningstar Indexes and pushing it further into the infrastructure layer for U.S. equity index funds.

While the company kept building outward, Mansueto’s story broadened in a different direction. He owns the Major League Soccer club Chicago Fire FC and the Swiss Super League club FC Lugano. In 2018, he bought Chicago’s Wrigley Building for $255 million. And if the Chicago Fire stadium at The 78 is completed in 2028, he will have spent more than $1.3 billion over a 10-year stretch building, buying, and renovating properties in and around the heart of Chicago. It’s a personal chapter that sits alongside Morningstar, not inside it.

His continued majority ownership of Morningstar has made him one of the wealthiest figures in finance and business. In 2024, Forbes included him on its “World’s Billionaires” list, estimating his net worth at $6.7 billion at the time of publication. And his philanthropic footprint has been just as deliberate: in May 2008, he and his wife, Rika, pledged $25 million to expand the University of Chicago’s Joseph Regenstein Library. The new wing—the Joe and Rika Mansueto Library, designed by architect Helmut Jahn—was completed in May 2011.

So, is Morningstar a tech company or a financial services firm? The question misses what it became. Morningstar is an information utility—financial infrastructure the industry quietly relies on. Its star ratings show up in retirement plan menus and regulatory filings. Its Style Box shapes how funds get classified and compared. PitchBook is where private-market diligence happens. DBRS Morningstar influences what many institutions are allowed to own.

Four decades after Joe Mansueto sat in his Chicago apartment, squinting at opaque prospectuses, the company he built has become part of how money moves through the world. The sun, it turns out, was indeed just a morning star.

X. Outro

If you want to go deeper on Morningstar’s worldview, start with the company’s own writing on its economic moat methodology, available through Morningstar’s research portal. One of the most complete public walk-throughs is “Why Moats Matter: The Morningstar Approach to Stock Investing,” authored by Heather Brilliant and Elizabeth Collins, which lays out how Morningstar tries to identify competitive advantages that can actually endure.

And if you want to understand the business the way Morningstar wants to be understood, read Kunal Kapoor’s annual shareholder letters. They’re unusually direct about what’s working, what isn’t, and where the company is placing its next bets—a continuation of the transparency culture Mansueto set in motion back in that Chicago apartment.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music