M/I Homes: Building the American Dream, One Community at a Time

I. Introduction: The Quiet Giant in Your Backyard

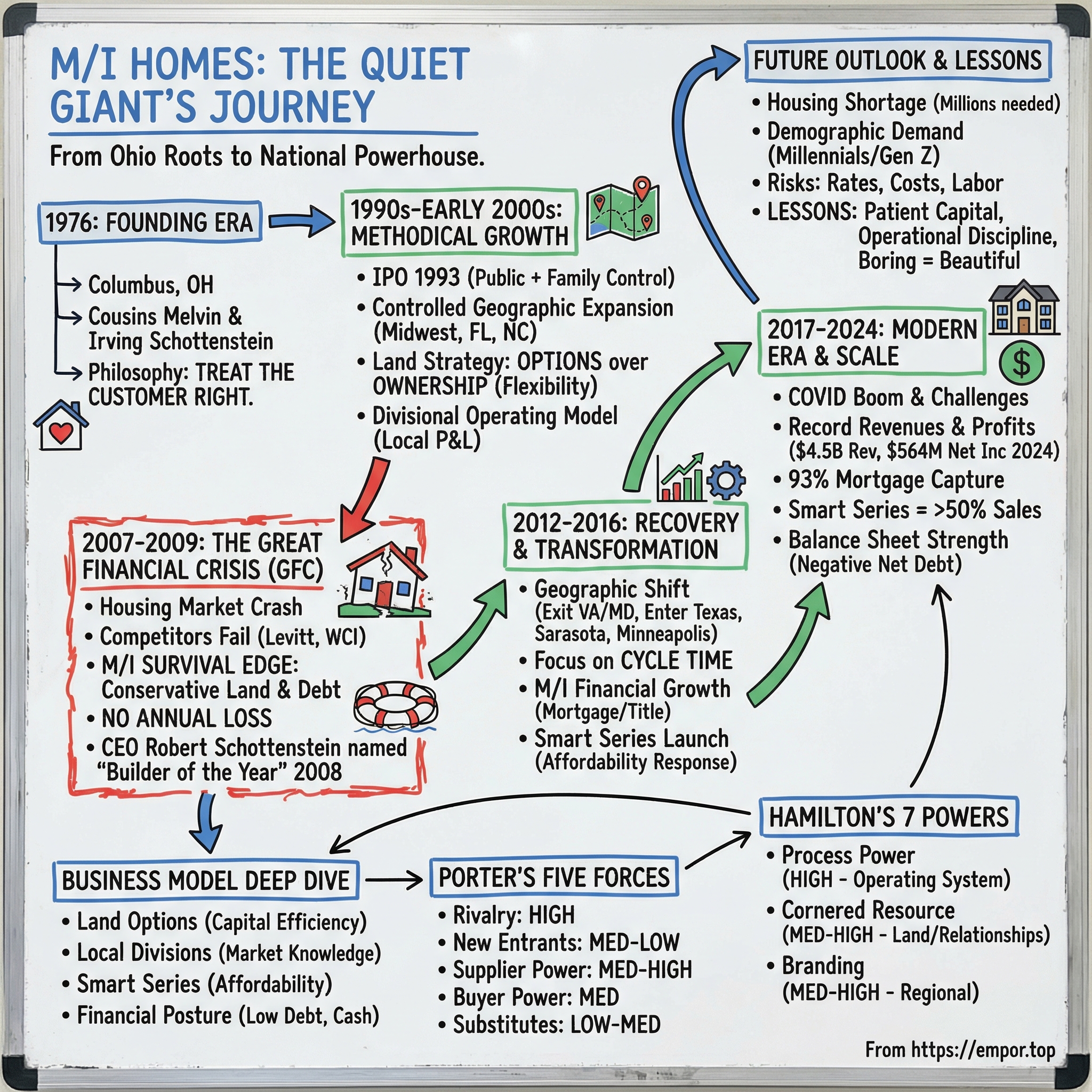

Picture late 2008. The housing market has cracked wide open—and it’s taking “can’t-miss” institutions down with it. Lehman Brothers is bankrupt. Bear Stearns is gone. In homebuilding, iconic names are toppling too. Levitt & Sons—the company that helped define postwar suburbia—files for Chapter 11. WCI Communities, once celebrated as “America’s Best Builder,” is scrambling for bankruptcy protection. Even Carl Icahn, who’d tried to buy WCI just a year earlier for about twenty-two dollars a share, watches that bet implode to well under a dollar.

And then there’s Columbus, Ohio.

While the headlines focus on collapse, a homebuilder most Americans have never heard of is doing something far rarer: staying on its feet—and quietly getting ready for the other side of the cycle. That same year, Builder Magazine names M/I Homes CEO Robert Schottenstein “Builder of the Year,” citing leadership through the Great Recession.

This is the story of M/I Homes: a company that started as an Ohio family business and, decades later, put up all-time highs—$4.5 billion in revenue, $564 million in net income, and $19.71 in earnings per share in 2024. The real question isn’t why M/I grew. It’s how it survived when so many bigger, better-known builders didn’t—and what that survival reveals about the company’s edge.

Because homebuilding isn’t like most businesses. It’s capital-heavy, brutally cyclical, and intensely local. Land is the inventory, but it’s also the bomb you’re holding when the music stops. Interest rates can take buyers out of the market almost overnight. And unlike software, you can’t ship a house with near-zero marginal cost—every home is a one-off project, built by local crews, on a specific piece of ground, in a specific municipality, under a specific set of rules.

In a business like that, the operators who actually understand risk don’t stand out in good times. They stand out when the cycle turns. M/I has shown, more than once, that it plays the game differently: conservative land strategy, disciplined capital management, and a long-term mindset shaped by family ownership. Together, those choices have produced one of the more durable models in American homebuilding.

So let’s rewind to where it all began.

II. The Schottenstein Dynasty and Founding Era

To understand M/I Homes, you have to start with the family behind it. In Columbus, the Schottensteins aren’t just successful—they’re woven into the city’s business and civic fabric, with reach that has spanned retail, real estate, and beyond for generations.

The story begins with Ephraim L. Schottenstein, a Lithuanian immigrant who settled in Columbus in the late nineteenth century. He started small: buying leftover, outdated merchandise from local stores and reselling it—literally out of a horse and buggy. It was unglamorous, but it was the kind of business that teaches you the fundamentals early: know your customer, watch your costs, and never confuse a good market with a good balance sheet.

Over time, that modest hustle grew into Schottenstein Stores Corp., and the family’s holdings expanded into some of the most recognizable names in American retail—Value City Furniture, American Eagle Outfitters, Designer Shoe Warehouse, and Consolidated Stores, later known as Big Lots. In Columbus, their imprint is also physical: Ohio State’s Jerome Schottenstein Center carries the family name, built in 1996 as a tribute to Jerome Schottenstein’s contributions to the city.

The second generation—brothers Jerome, Saul, Alvin, and Leon—helped scale the family enterprise just as discount retail took off in the late 1940s. Jerome, in particular, became known as a dominant figure and a formidable deal-maker, with a reputation for reviving struggling retail chains.

But M/I didn’t come from that exact branch of the tree. The homebuilding story starts in 1976, when cousins Melvin and Irving Schottenstein founded M/I Homes in Columbus. They weren’t coming in cold. They had already built experience in real estate development, including large apartment projects and work that included pioneering a golf course community—practical, on-the-ground knowledge that translated directly into the messy realities of building homes.

Their founding philosophy was straightforward: treat the customer right. It’s the kind of line that can sound like a slogan, until you see how deeply it gets baked into decisions—how you build, how you warranty, how you handle problems, and how you earn referrals in a business where reputation travels fast and mistakes are expensive.

The early results came quickly. By 1979—just three years in—M/I had become the number one homebuilder in Central Ohio. And it wasn’t a temporary spike. M/I still holds the number one position in Columbus today.

Then came expansion. In the early 1980s, M/I moved into Florida—Tampa in 1981, then Orlando three years later. By the late 1980s it added North Carolina markets, Raleigh and Charlotte. In 1988, it opened divisions in Cincinnati and Indianapolis.

That same year brought a piece of infrastructure that would matter far more than most people would realize at the time: the creation of M/I Financial, the company’s captive mortgage operation. This wasn’t just “another business line.” It gave M/I more control over the closing process, reduced friction for buyers, and created an additional profit stream tied directly to home sales. And it embedded a lesson that would become a recurring theme in M/I’s playbook: in homebuilding, managing the customer experience isn’t just marketing—it’s operational risk management.

In 1993, the company took its next big step: M/I Homes, Inc. went public on November 2. Not long after, it hit another milestone—10,000 homes closed the following year.

The IPO mattered because it added growth capital—but without wiping away the company’s roots. M/I managed a balancing act many companies struggle with: gaining access to public markets while still preserving substantial family control and the long-term mindset that comes with it.

And the choice of headquarters was part of that identity. Columbus is what real estate analysts call a “secondary market”—not a glamorous coastal superstar, but a stable place with a diversified economy, affordable land, and steady growth. That location didn’t just shape how M/I built in the early years. It would matter when the cycle turned, because the crash would hit the most overheated markets the hardest, while much of the Midwest saw more modest declines.

By the end of this founding era, the company’s DNA was already visible: grow methodically, stay close to the customer, build durable infrastructure like mortgage, and keep risk in check. Those aren’t exciting principles in a boom. They become everything when the boom ends.

III. Growth Through Geographic Expansion: The 1990s and Early 2000s

The decade after the IPO was a gift to American homebuilders. Rates drifted down, mortgages got easier, and demand felt endless—baby boomers trading up, their kids forming households, entire metro areas swelling outward.

A lot of builders took that as a signal to swing for the fences. They bought land everywhere, in huge quantities, and piled on debt to do it—because in a rising market, the quickest way to look like a genius is to own more dirt.

M/I expanded too. It just didn’t do it like that.

Through the 1990s and early 2000s, the company moved outward in a controlled way, adding markets one by one and sticking to places that looked less like lottery tickets and more like long-term bets: stable, growing metros with diversified local economies. The Midwest stayed central—Columbus, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Chicago. The South offered the growth engine—Florida markets like Tampa and Orlando, and the Carolinas in Charlotte and Raleigh. Texas would eventually become part of the story, but not yet.

Over time, M/I grew from a Columbus family builder into a national operator with divisions across 17 markets, including Austin, Charlotte, Chicago, Cincinnati, Columbus, Dallas, Detroit, Fort Myers/Naples, Houston, Indianapolis, Minneapolis, Nashville, Orlando, Raleigh, San Antonio, Sarasota, and Tampa.

As the footprint widened, a distinctive operating model clicked into place. Each division ran like its own business, led by a local president with real P&L responsibility. That wasn’t a cultural quirk—it was strategy. Land, regulations, labor, and buyer preferences are intensely local, so land decisions lived close to the ground. Corporate headquarters wasn’t picking subdivisions on a map from Columbus.

But it also wasn’t a loose federation. The center provided the guardrails: purchasing leverage, financial controls, and a system for sharing what worked across markets. The result was an uncommon mix—local entrepreneurship with institutional discipline. Division leaders had room to adjust to their market, and nowhere to hide if results didn’t show up.

Product followed the same philosophy. M/I didn’t bet the company on a single buyer type. It designed, built, and sold everything from first-time and millennial homes to move-up, empty-nester, and luxury product, including both single-family homes and attached townhomes under the M/I Homes brand. That flexibility mattered because cycles don’t just change demand—they change which buyer segments can actually transact.

Still, the most important decision in this era wasn’t flashy. It was the land strategy.

Homebuilding is a land business first and a construction business second. You can’t sell homes without lots. The real question is whether you want to own the land outright—or control it without carrying it.

In the boom years, many builders stuffed their balance sheets with massive land banks—tens of thousands of lots purchased outright, often financed with debt. When land prices rose, it looked like free money. When prices fell, it turned into a trap.

M/I leaned hard into a different approach: land options. Instead of buying land outright, it often paid a smaller deposit for the right—but not the obligation—to buy lots later at a predetermined price. If the market kept running, M/I could exercise the option. If the market turned, it could walk away, losing the deposit rather than being stuck with the full land value.

Its land-light strategy—owning 25,210 lots and controlling 25,887 more—ensures a five-year supply of inventory, reducing exposure to price volatility.

That tradeoff was deliberate. Owning less land meant giving up some upside in the best of times. But it also meant lowering the kind of risk that can end a company.

By 2005, M/I was doing more than $1.5 billion in revenue and had become the eighteenth-largest homebuilder in the country—big enough to be a real player, still small enough to stay nimble. The balance sheet was conservative. The land position was flexible. The operating model was working across a widening set of markets.

And then the cycle turned—fast.

IV. The Great Financial Crisis: Survival When Others Perished

What hit housing in 2007 and 2008 wasn’t a normal downturn. It was one of the most severe financial crises in modern history, and it pulled the entire global economy down with it. In the U.S., mortgage debt swelled dramatically—rising from roughly mid-40s as a share of GDP in the 1990s to the low 70s by 2008, topping $10 trillion.

For a while, it had felt like the laws of gravity didn’t apply. Home prices had climbed relentlessly—roughly doubling from the late 1990s to the mid-2000s—and a whole ecosystem formed around the assumption they’d keep going. Then the market flipped. From mid-2006 to mid-2008, prices fell sharply, and the financing machine that had powered the boom seized up.

For homebuilders, that combination was existential. The Great Recession that began in 2008 didn’t just slow demand; it detonated it. More than six million American households ultimately lost homes to foreclosure. That’s not “a tough market.” That’s your customer base getting erased.

The builder casualties were brutal and very public.

Levitt & Sons—yes, that Levitt, the company that helped invent modern suburbia and pioneered mass-production homebuilding after World War II—couldn’t make it. After decades in business, Levitt filed for Chapter 11 in late 2007.

WCI Communities, a Florida builder led by billionaire investor Carl Icahn, also sought bankruptcy protection as losses piled up quarter after quarter. And TOUSA—at the time, the largest builder in the country to file—went down with billions in assets and nearly as much debt, joining a growing list of builders that had entered bankruptcy in just a matter of months.

This was the backdrop. The industry wasn’t “struggling.” It was breaking.

And this is where M/I’s boring, conservative choices suddenly became the whole story.

The land option strategy—so easy to dismiss during the boom—turned into a life raft. When the market collapsed, M/I could walk away from optioned land instead of being stuck owning it at yesterday’s prices. Builder magazine, in recognizing what M/I had done, pointed directly to the defensive posture: cost reductions, balance-sheet protection, and a deliberate tightening of the land position. Since 2006, M/I had cut its total lots owned and controlled by about half.

That shift wasn’t theoretical. In 2007, bulk land sales helped drive a major reduction in owned lots. And M/I went after leverage with the same urgency. Early in 2007, it owed its banks $410 million on its revolving line of credit. By year-end, that balance had been reduced by more than 70%, with the expectation it would go to zero during 2008.

In boom times, that kind of balance-sheet discipline can look like you’re leaving money on the table. In a crash, it’s the difference between “restructuring” and “surviving.” While competitors were trapped under crushing debt and land impairments, M/I kept flexibility—and ended up with debt levels among the lowest in the industry.

The industry noticed quickly. On May 13, 2008, M/I announced that Builder magazine had named CEO Robert H. Schottenstein “Builder of the Year,” an award given to the executive seen as having the most profound impact on their company over the prior year.

Schottenstein wasn’t new to the business. He’d been at M/I since 1985, served as President since 1996, and had been a director since the company went public in 1993. By the time he became CEO in early 2004 and Chairman shortly after, he brought a combination of institutional knowledge and outside training as a real estate attorney—useful skills when your entire industry is suddenly negotiating with banks, rewriting contracts, and trying to keep the wheels from coming off.

This leadership change was more than a title swap. It was a generational handoff from Irving to Robert that kept M/I’s conservative DNA intact while continuing to professionalize how the company ran.

And then there’s the stat that almost sounds impossible if you lived through that era: M/I never posted an annual loss during the crisis. In a period when builders were taking massive writedowns and impairments, that kind of consistency was nearly unheard of.

The ownership structure helped explain why. Schottenstein, as CEO, directly owned 2.26% of the company’s shares. When your name is tied to the business and you own real equity, you tend to manage differently. You avoid the bets that look brilliant for a year and fatal over a cycle.

For anyone trying to understand M/I, this is the proving ground. The crisis didn’t just test the company—it revealed it. Options over ownership. Conservative leverage. Geographic diversification. Operational discipline. M/I didn’t invent those ideas in 2008. It simply lived long enough for the market to prove they were the right ones.

V. Recovery and Transformation: 2012-2016

When the dust settled, homebuilding wasn’t the same business it had been in 2005. The weaker players were gone or badly damaged. Mortgage underwriting tightened. And a new kind of competitor showed up with deep pockets: institutional investors buying single-family homes to rent, soaking up inventory and changing the demand picture in real time.

M/I came out of the crisis with something most builders couldn’t say: options, flexibility, and the freedom to choose where to play next. So it made a set of geographic calls that weren’t flashy, but were decisive. It shut down its Virginia and Maryland divisions—markets it didn’t want to fight through the recovery—and leaned harder into the Sunbelt.

Texas became the centerpiece. Before 2015, M/I entered Houston, San Antonio, Austin, and Dallas—metros benefiting from job growth, inbound migration, and a cost of living that still looked reasonable compared with the coasts. And true to form, M/I didn’t charge in like a tourist. It built local teams, established relationships with developers and municipalities, and assembled land positions deliberately.

Then it widened the map again. In 2015, M/I opened a division in Minneapolis. In 2016, it expanded into Sarasota, Florida—and crossed a symbolic milestone: more than 100,000 homes sold.

Operationally, the focus shifted from simply surviving to getting sharper. Cycle time—contract to closing—became a central obsession. The logic was simple: build faster and you free up capital faster, customers get their homes sooner, and returns on inventory improve. M/I backed that push with technology, investing in CRM systems, land acquisition analytics, and digital marketing that complemented the company’s traditional, relationship-driven approach.

The leadership dynamic mattered here too. Robert Schottenstein remained CEO, and Phillip Creek—then CFO, later President and COO—brought a steady hand on financial discipline and operational rigor. It was a pairing built for a recovery: vision and market feel on one side, process and controls on the other, both aligned around preserving the conservative culture that had kept M/I alive.

The results followed: margins improved, community counts rose, and returns on equity climbed. But the signature was what didn’t change. M/I grew, but it didn’t sprint. The company kept playing the long game—building a platform that could compound through the next cycle, not just look good in the first few years after the last one.

VI. The Modern Era: Scale, Efficiency, and Market Leadership (2017-2024)

From 2017 on, M/I stepped into the phase every builder says they want: real scale, real process, and enough institutional muscle to keep performing even when conditions refuse to cooperate. The opportunity was huge. So were the curveballs. What stands out is how steady M/I stayed through both.

Then came COVID—and the strangest housing market most people had ever seen. Overnight, homes weren’t just shelter; they were offices, classrooms, gyms, and the one controllable piece of your life. Remote work untethered buyers from city centers. Suburbs and secondary markets pulled demand forward. And millennials, who’d spent years on the sidelines, showed up in force. Layer on historically low interest rates and suddenly housing demand was red-hot.

In some markets, new homes made up as much as 30 percent of all home sales—when “normal” is closer to 10 percent. Builders who had spent a decade rebuilding capacity after the Great Recession couldn’t add supply fast enough.

M/I’s response looked a lot like its response to every other cycle: don’t get drunk on the moment. While some competitors pushed pace too hard or treated pricing like a one-way lever, M/I managed sales velocity and price increases carefully—trying to capture the upside without burning future customer relationships or turning communities into churn.

That discipline showed up in the numbers. Pretax margin improved to 16.3% from 15.1% the prior year, driving record pretax income of $734 million. And by 2024, the results were the culmination of years of compounding execution: deliveries rose 12% to 9,055 homes, revenue climbed 12% to $4.5 billion, gross margin expanded to 26.6% from 25.3%, and pretax income reached $734 million—up 21% year over year.

Return on equity landed at 21%. In a capital-intensive, highly cyclical industry, that isn’t just “strong.” It’s the kind of performance that tells you the operating system is working.

At the same time, the second engine in the business kept getting more important: financial services. M/I’s integration through its mortgage and title operations deepened into a real competitive advantage. Mortgage capture hit 93%, up from 89% the year before. Mortgage and title operations revenue rose to $34.6 million, a 16% increase.

When you capture more than 90% of buyers through your own mortgage platform, you’re not just adding a profit stream. You’re controlling the closing process, cutting down delays, and getting cleaner feedback loops on what buyers can qualify for, what incentives work, and where affordability is tightening—all of which flows back into how you price, design, and pace communities.

This era also clarified the strategic importance of one product line in particular: Smart Series. The concept is simple, but powerful—deliver the energy efficiency, design, and warranty of a new home, but at a lower price point and with a faster, more predictable build. Standardized plans. Curated finish packages. Less friction for the buyer, less complexity for construction.

M/I kept leaning into it. Smart Series represented 52% of Q2 2025 sales, with an average selling price of $400,000. The larger point isn’t the percentage—it’s what it signals: M/I has built a scalable response to the biggest structural issue in American housing, which is that many first-time buyers are being priced out of new construction entirely.

And then the market turned again. After 2022, rates rose sharply and affordability tightened almost overnight. M/I adapted without panicking. Instead of reaching for broad price cuts that can permanently reset expectations and compress margins, the company leaned on mortgage rate buydowns to drive traffic and convert sales—paying to reduce a buyer’s rate temporarily, making the monthly payment work without blowing up headline pricing.

Underneath all of this is the footprint M/I has spent decades assembling. As the 13th-largest homebuilder in the U.S., M/I operates across 17 markets in 10 states, with particular strength in the Midwest and the South. It has depth where it matters—strong positions in places like Columbus, Chicago, Minneapolis, Charlotte, Raleigh, Tampa, and across Texas—enough scale to matter, but still focused enough to know each market intimately. In many divisions, M/I typically ranks in the top five or top ten—big enough to have real operating leverage, but not so sprawling that it loses the local edge that built the company in the first place.

VII. The M/I Business Model Deep Dive

To really understand M/I Homes, you have to look past the houses and into the operating system underneath them—the set of choices that determines how much risk the company takes, how fast it can move, and how well it can hold up when the cycle turns.

The Land Strategy as Competitive Advantage

Every homebuilder needs land. The only question is whether you want to be an owner—or a controller.

M/I has built its entire model around balancing the two. As of mid-2025, the company owned and controlled more than 52,000 single-family lots, or roughly a five-to-six-year supply. And it wasn’t skewed heavily in one direction: about half were owned, and about half were controlled through options.

That split is the point. Owned lots give you certainty of supply and the ability to capture the full economics of development. Optioned lots give you flexibility. If demand dries up or prices fall, you can walk away from an option with limited damage instead of being forced to carry land bought at the top of the market.

As of June 30, 2025, M/I’s mix was 49% owned and 51% optioned. In practice, that’s not just risk management. It’s capital efficiency. Land sitting on the balance sheet ties up cash. Options typically require much smaller deposits, which means more capital stays available for building homes, marketing communities, or returning money to shareholders.

The real art is calibration. Too little land and you can’t grow. Too much and you’re dragging a heavy, expensive anchor through the next downturn. M/I’s long-running discipline is keeping enough supply to have visibility, without overcommitting when conditions look great—because that’s usually when the risk is highest.

The Divisional Operating Model

M/I is also structured the way homebuilding actually works: locally.

Each division president effectively runs a standalone business for their market, with responsibility for land acquisition, sales, construction, and profitability. That local accountability matters because the variables that decide whether a community works—land prices, labor conditions, buyer preferences, municipal approvals, and competition—can look totally different in Tampa than they do in Minneapolis.

At the same time, divisions aren’t on their own. The corporate center provides the guardrails and leverage: purchasing power with national suppliers, shared technology and systems, financial controls, and a way to spread best practices across markets. Headquarters allocates capital and sets discipline, without trying to micromanage a business where local knowledge is the edge.

In the third quarter, division income contributions were led by Columbus, Chicago, Dallas, Minneapolis, Orlando and Cincinnati. The specific list will change over time, but the pattern is the important part: M/I doesn’t need a single metro to be a hero every year. Its portfolio is built so performance can come from multiple places at once.

Smart Series as Strategic Response to Affordability

Smart Series deserves its own spotlight, because it’s M/I’s answer to the defining problem in U.S. housing: affordability.

When we created the term Smart Series we didn't have technology in mind. Instead, we had the idea to base these homes on 3 basic principles to make your journey to homeownership easier and more enjoyable: Smart Process: From start to finish it's quick and easy. Select your home plan and choose your structural options. Smart Design: Professionally chosen design packages take the guesswork out of the design process and guarantee beautiful results. Smart Value: Our architectural designs, business process, and pre-selected finishes save you money today, while our homes loaded with energy efficient features will save you money tomorrow and for years to come.

Operationally, the model is elegant: reduce variability. By limiting customization and using pre-selected finish packages, M/I cuts complexity in construction and shortens timelines. Buyers make fewer decisions, sales move faster, and standardized materials make purchasing more efficient.

And it’s become a major driver of the business:

Our Smart Series, which is, as we've stated previously, our most affordable line of homes, continues to be an important contributor to sales performance. During the third quarter, Smart Series sales comprised about 52% of total sales compared to just about 50% a year ago.

When more than half your sales are coming from the most affordable product line, you’re not just selling houses—you’re positioning the company for the next decade of demand, whether that demand comes from first-time buyers, downsizing empty nesters, or value-conscious move-up families.

Financial Model Characteristics

If the land strategy and operating model are the engine, M/I’s financial posture is the seatbelt.

The company has kept leverage conservative, with a homebuilding debt-to-capital ratio of 19% (down from 22% a year earlier). That restraint matters in a cyclical business where debt can turn a normal downturn into an existential one.

Cash has been another defining feature. The company reported substantial cash at year-end, giving it both a defensive buffer and the ability to act quickly when opportunities appear.

We ended the quarter with record net worth of $3 billion, a 14% increase from a year ago, book value of $112 per share, zero borrowings under our $650 million unsecured borrowing line, cash of $776 million, homebuilding debt-to-capital of 19% and a net debt-to-capital ratio of negative 3%.

That last line is the headline: a negative net debt-to-capital ratio—meaning more cash than debt. For a homebuilder, that’s rare air. It’s also strategic freedom: the ability to keep building through a slowdown, to buy land when others can’t, and to play offense precisely when the rest of the industry is forced into defense.

VIII. Leadership, Culture, and the Schottenstein Factor

The Schottenstein family’s continued involvement gives M/I a dynamic you don’t see often in public companies: patient, long-horizon leadership that doesn’t have to reinvent itself every few years to satisfy a new regime.

Robert Schottenstein has been at the center of that continuity. After decades with the company, he became one of the defining stewards of the M/I playbook—staying focused on the cycle, not the quarter. He has also had real skin in the game, and that alignment matters. In an industry where the temptation is always to overextend in the good times, ownership pushes you toward decisions you can live with when the market turns.

His background helped too. Before leading M/I, he worked as a real estate attorney, which sounds like trivia until you remember what homebuilding actually is: a dense web of contracts, zoning rules, land-use approvals, financing terms, and closing mechanics. The legal architecture is the business. Having a CEO who understands that machinery from the inside tends to produce fewer “surprises,” and better decisions about risk.

The industry recognized that leadership long before M/I became widely discussed outside builder circles. In 2002, Schottenstein received the Central Ohio Building Industry Association’s Builder of the Year award. In 2008, Builder Magazine named him national “Executive of the Year,” specifically for how he led through the housing crash. In 2009, he received an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree from Ohio Dominican University.

The company’s headquarters choice reinforces the same identity. M/I could have followed the gravitational pull of the industry and relocated to places like Texas or Florida. It didn’t. Staying in Columbus keeps the company anchored to its roots, avoids the cost and churn of coastal hubs, and fits the brand: steady, practical, and built around long-term relationships.

That culture shows up in what M/I says it values—integrity, customer service, and fairness to employees and trade partners—but also in why those values matter. Homebuilding is a relationship business. Trades choose who they prioritize. Municipalities remember who shows up prepared. Buyers tell their friends what happened after the closing when something went wrong. In a world like that, consistency isn’t soft. It’s leverage.

Schottenstein has tied those values to community involvement as well, including support for affordable housing initiatives like Homeport:

"The Homeport Voice and Vision honor means a great deal to me personally as well as to our company," Schottenstein said. "My Dad, Irving, was actively involved in the original founding of Homeport, and since that time our company has remained a consistent supporter and champion of Homeport and its mission."

It’s not just philanthropy as a line item. It’s another signal of how M/I sees itself: not as a financial instrument that happens to build houses, but as a long-running institution built to last through cycles—and to keep building communities in the process.

IX. Competitive Position: Porter's Five Forces Analysis

To see where M/I fits, it helps to zoom out and look at the structure of the homebuilding industry itself. Porter's Five Forces is a clean way to do that—because in this business, performance isn’t just about execution. It’s also about what the industry makes possible.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Homebuilding is getting more consolidated, but it’s still intensely competitive. Recent NAHB analysis of Builder magazine data shows the top 10 builders accounted for 44.7% of new single-family closings in 2024. And the two biggest names—D.R. Horton and Lennar—show up almost everywhere, appearing on the top-ten builder list in 46 of the 50 largest U.S. markets.

Those giants set the tone for the industry. D.R. Horton, for example, is consistently the largest U.S. homebuilder by volume. In 2024, it delivered roughly 89,700 homes across 36 states and generated close to $36 billion in revenue.

Against that backdrop, M/I sits in an interesting spot. With a little over 9,000 deliveries and $4.5 billion in revenue, it’s large enough to matter—typically a top-fifteen builder—but not so large that it can overpower markets through sheer scale. That means rivalry shows up in the most visceral ways: who has the better lot in the better school district, who can hit the right price point, who can build with fewer delays, and who earns enough trust to keep referrals coming.

Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM-LOW

It’s hard to “just start” a homebuilder at scale. You need capital, land acquisition expertise, relationships with municipalities, and a reliable trade base—and you need to thread all of that through permitting, zoning, and regulatory complexity that’s only gotten tougher since 2008.

That doesn’t mean new competitors never appear. Well-capitalized private equity firms can enter through acquisitions and roll-ups, which changes the competitive landscape in specific markets. But building something that looks like a national homebuilder from scratch is still a multi-year, multi-billion-dollar climb.

Supplier Power: MEDIUM-HIGH

In homebuilding, the key inputs are famously stubborn: lumber, labor, and land. They’re constrained in normal times and can become a choke point in abnormal times—like the post-COVID supply chain disruptions that reminded everyone how fragile “just-in-time” can be. Skilled construction labor, in particular, remains scarce in many markets.

M/I’s size gives it some leverage with national suppliers, but it doesn’t get to escape the industry’s underlying constraints. One place it does improve its position is through its vertically integrated mortgage and title operations, which allow it to capture margin that would otherwise flow to third parties and reduce dependency in parts of the closing process.

Buyer Power: MEDIUM

Buyers have options, but they’re shopping in a market defined by scarcity. Inventory constraints and the broader housing shortage limit how hard buyers can push, especially in desirable submarkets.

Freddie Mac has estimated the U.S. housing shortage at 3.7 million units. Goldman Sachs Research has argued that several million additional homes beyond normal construction would be needed to meaningfully address supply and affordability. The exact number is debated, but the directional point isn’t: there aren’t enough homes.

Buyer power also varies by segment. First-time buyers tend to be the most price-sensitive, and the most vulnerable to payment shocks. Move-up buyers often have more flexibility and, in some cases, more negotiating leverage.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MEDIUM

The obvious substitute for a new home is an existing home. But in today’s market, that substitute is unusually constrained, in part because of the mortgage “lock-in” effect: many homeowners don’t want to give up the low rates they already have.

About half of current U.S. mortgage borrowers still have rates below 4%, and roughly 80% are under 6%. That creates a powerful incentive to stay put, which keeps resale inventory tight and makes “just buy an existing home” less available than it would be in a normal cycle.

Renting is another substitute, but it’s a fundamentally different tradeoff—more flexibility, less long-term wealth-building, and a different lifestyle proposition. For many households, it’s not a clean replacement for ownership.

X. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework is a way to ask a simple question: what, if anything, makes an advantage durable? Here’s how M/I looks through that lens.

Scale Economies: MODERATE

Scale helps, but only up to a point. M/I gets meaningful purchasing leverage with suppliers, and it can spread overhead across more homes to improve efficiency. But homebuilding is still a street-by-street business. You can’t ship a house, national size doesn’t automatically win you a great lot, and it doesn’t get a zoning board to move faster.

Where scale matters more is in financial services. M/I Financial has real fixed infrastructure, and once it’s built, it can handle more loans with relatively low incremental cost.

Network Economics: LOW

This isn’t a network business. Homeowner communities can generate referrals and some word-of-mouth momentum, but there’s no true network effect that compounds on itself.

Counter-Positioning: LOW

M/I doesn’t win because it’s doing something competitors can’t respond to. In fact, many builders have moved toward similar land-light strategies over time, working with third-party land owners, targeting growth corridors, and studying migration and local economic fundamentals. The playbook can be copied; the harder part is executing it well for decades.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

On the company side, there are real switching costs embedded in relationships. Builders accumulate trust with land developers, municipal officials, and trade partners over years. That local knowledge and credibility is slow to build and hard to shortcut.

On the customer side, switching costs show up the moment a buyer signs. Deposits, timelines, financing coordination, and the emotional commitment of choosing a home all create a kind of practical lock-in.

Branding: MODERATE-HIGH (Regional)

M/I isn’t a household name nationally like D.R. Horton. But in several of its core markets—like Columbus, Tampa, and Charlotte—it has deep brand recognition. In homebuilding, that translates into something tangible: trust, a reputation for quality and service, and more referral-driven demand.

Smart Series is also building its own identity inside the broader brand, aimed squarely at value-conscious buyers who still want a new-home experience.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE-HIGH

Some “resources” in homebuilding are literal. Controlling lots through option contracts in desirable locations can be a cornered resource—competitors can’t buy what you’ve already tied up, and they certainly can’t buy it on your terms.

Others are less visible but just as real: decades of relationships, market knowledge, and a management culture built to handle cycles.

Process Power: HIGH

This is the big one. M/I’s most durable advantage is its operating system—its land-light model, its discipline around risk, and a divisional structure that balances local accountability with central guardrails. That system creates repeatable benefits: - Less capital tied up than asset-heavy peers - Flexibility when the market shifts - Stronger risk-adjusted performance through cycles - Operational gains that come from continuous improvement

And importantly, it’s not a process you copy overnight. It’s something you build, tune, and reinforce for years.

M/I's Durable Competitive Advantage Summary: Process Power (land-light model and divisional operations) + Cornered Resources (land options and local relationships) + Regional Branding = sustainable above-average returns in a consolidating industry.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case and Future Outlook

The Bull Case

Start with the simplest macro fact: the U.S. doesn’t have enough homes. Depending on who you ask and how they measure it, the shortage is counted in the millions. A report commissioned by the National Association of Realtors (NAR), for example, puts the gap as high as 5.5 million units.

Even more conservative estimates still land on a meaningful deficit. One view is that the shortage is roughly 2.8 million homes and could take about a decade to work through. And that may understate the real problem, because it focuses on physical shortfall without fully capturing “missing” households—people who would have formed households, but didn’t, because housing felt out of reach.

Layer on demographics and you get the second pillar of the bull case. Millennials and Gen Z are still moving into prime household-formation years. Even with affordability pressure, first-time buyer demand doesn’t disappear; it backs up. People wait, double up, rent longer—then re-enter the market when the monthly payment finally pencils out.

This is where M/I’s product and risk posture line up with the moment. Smart Series is built for value-conscious buyers who still want the benefits of a new home, and M/I’s land-light approach provides a kind of built-in shock absorber. It’s designed to participate in the upside without taking the full balance-sheet hit if the cycle turns.

Geography helps too. M/I’s exposure to Sunbelt markets positions it to benefit from longer-term migration trends out of higher-cost regions. And the company’s management team has credibility here, because it’s already navigated multiple cycles without blowing up the model. Combine that with a strong balance sheet, and M/I has the capacity to act opportunistically if weaker competitors stumble.

Or, in the company’s own words:

"As we begin 2025, we believe our industry will continue to benefit from strong fundamentals, including favorable demographic trends and an undersupply of housing."

The Bear Case

The counterweight is just as straightforward: homebuilding is cyclical, and it doesn’t care how good you are. When recessions hit, demand can drop fast. Financing tightens, buyers freeze, cancellations rise, and even disciplined builders feel it.

Rates are the big lever. As mortgage rates climb, affordability deteriorates quickly, and each percentage point move can push a large number of buyers out of qualification range. That matters most for the first-time segment, which is exactly where Smart Series plays.

Then there are the structural constraints and disruptions that don’t show up neatly in a spreadsheet. Climate risk is real in key geographies—Florida hurricanes and Texas extreme heat can interrupt building schedules, disrupt insurance markets, and change buyer behavior. Labor remains another hard limit: when skilled trades are scarce, it’s difficult to scale construction even when demand is present.

Competition is also getting sharper. The largest builders—D.R. Horton, Lennar, and the rest of the top tier—are gaining share. The top ten builders now control about 45% of the market, up roughly 14 percentage points since 2019. Consolidation like that can squeeze mid-sized operators by intensifying bidding wars for land, trades, and finished lots.

And we can see pressure showing up in the income statement. Despite revenue growth, margins have tightened recently: gross margin fell to 24.7% from 27.9% in Q2 2024. SG&A as a percentage of revenue also ticked up, to 11.3% from 11.0% year over year.

Key Risks to Monitor

- Interest rate trajectory and Federal Reserve policy

- Land cost inflation and what it does to future margins

- Lumber and broader material cost volatility

- Labor market tightness limiting construction capacity

- Regulatory changes affecting zoning and development timelines

- Regional market swings, especially in Texas and Florida

What to Watch: The Key KPIs

If you’re tracking M/I, two operating metrics tell you most of what you need to know—because they capture the two things that drive this business: profitability and demand.

1. Gross Margin: This is the clearest read on pricing power, build efficiency, and land cost discipline. The recent move from the high-20s down into the mid-20s reflects the real-world cost of keeping buyers qualified—mortgage buydowns—plus competitive pressure. The question is whether margins stabilize as the market normalizes, or keep leaking as incentives rise.

2. Absorption Rate (Homes Sold Per Community Per Month): This is the pace gauge. M/I’s recent absorption of 2.7 homes per community per month, down from 3.2, signals softer demand. If absorption rebounds, it suggests buyers are coming back and incentives are working. If it slides further, it’s a warning that the market is weakening faster than pricing can adjust.

Together, margin and absorption tell the story in real time: how profitable each home is, and how quickly the company can sell the next one.

XII. Lessons and Playbook for Founders and Investors

For Founders Building Companies

M/I Homes offers a handful of lessons that translate far beyond homebuilding:

Capital structure matters—debt kills in downturns. The builders that went bankrupt in 2008 weren’t all bad operators. Many were simply over-levered when revenue evaporated. M/I’s conservative approach to debt didn’t make headlines in the boom, but it created the breathing room to survive when the market snapped.

Options beat ownership when flexibility has value. Land options can look like leaving money on the table in a bull market—you don’t capture the full appreciation. But optionality is priceless when uncertainty spikes. The broader point: build flexibility into your model before you need it, because you won’t be able to bolt it on mid-crisis.

Be conservative when others are aggressive—and you get to play offense later. When competitors are expanding recklessly, restraint feels like underperformance. Then the cycle turns, and restraint becomes ammunition. M/I came out of the crash with fewer competitors, more share to take, and better opportunities to deploy capital.

Culture and long-term thinking compound. Family ownership gave M/I room to think in decades, not quarters. In cyclical industries especially, that time horizon changes decisions: less pressure to juice near-term results, more willingness to protect the balance sheet and the franchise.

Operational excellence compounds over decades. Faster cycle times, tighter processes, better customer experience—none of it looks dramatic in a single quarter. Over years, it becomes a moat. The companies that treat execution like a long game end up with an operating system others can’t easily replicate.

For Investors Evaluating Companies

Cyclicals require different valuation frameworks. Peak-cycle earnings can make P/E ratios look deceptively cheap right before profits roll over. What matters more is through-cycle performance—and whether the balance sheet can absorb the trough.

Management quality is paramount in cyclical industries. In stable businesses, “good enough” leadership often is. In cyclical ones, transitions are where companies live or die. The real test is how management behaved the last time conditions got ugly.

Business model nuances matter enormously. “Homebuilder” is a label, not a thesis. Land-heavy versus land-light, integrated mortgage and title versus pure construction—those choices create totally different risk profiles and different outcomes when the market turns.

Boring can be beautiful. Columbus, Ohio isn’t glamorous, and M/I doesn’t dominate national headlines. But steady execution in stable markets, repeated over long periods, can produce exceptional returns with less drama than the flashier stories.

Crisis survivors often emerge stronger. Companies that make it through a downturn intact don’t just survive—they inherit opportunity. Weaker competitors shrink or disappear, assets go on sale, and the survivors build institutional muscle that only comes from living through a real stress test.

The M/I Formula

Smart markets + Land options + Operational discipline + Patient capital + Long-term leadership = Survive and thrive through cycles.

XIII. Epilogue: Where M/I Stands Today

As 2025 winds down, M/I Homes sits in a familiar place for anyone who’s followed its history: the market is messy, the headlines are mixed, and the company is still standing—steady enough to plan, flexible enough to adapt.

"Though current conditions are choppy, and are likely to continue for the foreseeable future, we remain optimistic about our business and the longer-term outlook for the housing industry. Our balance sheet is the strongest in Company history."

That balance-sheet confidence is paired with an intent to keep growing. M/I expects its community count to rise about 5% in 2025, and it anticipates delivering roughly 12,000 to 14,000 homes next year.

The financial posture reinforces the point. By the end of the third quarter, M/I reported record equity of $3.1 billion, translating to book value of $120 per share, up 15% from a year earlier. Its mortgage and title operations also hit a record: capturing 93% of the company’s closings in the quarter, up from 89% the year before. And it doubled down on liquidity, extending its bank credit facility out to 2030 and expanding capacity from $650 million to $900 million—all while reporting zero borrowings under the facility.

But the bigger story extends beyond any one builder. Housing is critical infrastructure, and the U.S. is still short millions of homes. Realtor.com warned that the nation’s housing supply gap was on track to approach 4 million homes in 2024, and that closing it could take more than seven years of sustained building.

That context is what makes the next decade so interesting. If factory-built construction continues to gain acceptance, manufactured housing could become a larger piece of the affordability solution. Build-to-rent could keep expanding through partnerships between builders and institutional investors. And climate-adaptive construction may move from “nice to have” to table stakes as extreme weather reshapes codes, insurance, and buyer preferences.

Still, the cleanest way to understand M/I’s story is to zoom out and look at what it did when it mattered most. The company’s greatest achievement isn’t the record earnings or the $4.5 billion in revenue. It’s that it survived 2008 when so many others didn’t.

Levitt and Sons, the legendary builder of Levittown... had been in business since 1929, but it could not weather the current housing crisis.

M/I Homes was founded in 1976. It has now operated for nearly fifty years through multiple cycles, building more than 170,000 homes. The company that invented American suburbia is gone. M/I remains.

That survival—and the discipline that made it possible—is the headline. Patient capital, operational excellence, and conservative management never go out of style. In an industry that punishes the undisciplined, M/I has proven, again and again, that boring can be beautiful.

XIV. Further Reading and Resources

If you want to go deeper—into M/I specifically, and into the mechanics of homebuilding more broadly—here are the best places to spend your time:

-

M/I Homes Annual Reports & 10-Ks (2005-2024)—especially the Management Discussion & Analysis section, which shows how the company explains its strategy and risk posture across very different markets

-

"The Big Short" by Michael Lewis—a clear, readable way to understand the housing and credit machine that collapsed in 2008, and why survival required more than just “building good homes”

-

Builder Magazine’s Builder 100 analysis—the annual scorecard of the industry, including rankings, market share shifts, and who’s gaining or losing ground

-

Robert Schottenstein earnings call transcripts—straight from management, with real-time commentary on land, demand, cancellations, cycle times, and how they’re thinking about the cycle (typically accessible through investor relations and transcript services)

-

National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) research—foundational industry data on housing starts, completions, and macro conditions that shape every builder’s results

-

John Burns Real Estate Consulting market studies—sharp, operator-focused analysis on regional housing dynamics, pricing, and demand signals

-

Joint Center for Housing Studies (Harvard University) reports—a more academic lens on housing supply, affordability, and the demographic forces underneath it all

-

Freddie Mac housing supply research—useful work on the structural housing shortage and the long-term constraints keeping inventory tight

-

Zelman & Associates housing research—institutional-grade, Wall Street-style coverage of the homebuilding sector and the cycle

-

Company investor presentations—quarterly slide decks with operational metrics and strategic updates, available at mihomes.com

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music