Mattel Inc.: The Story of America's Toy Empire

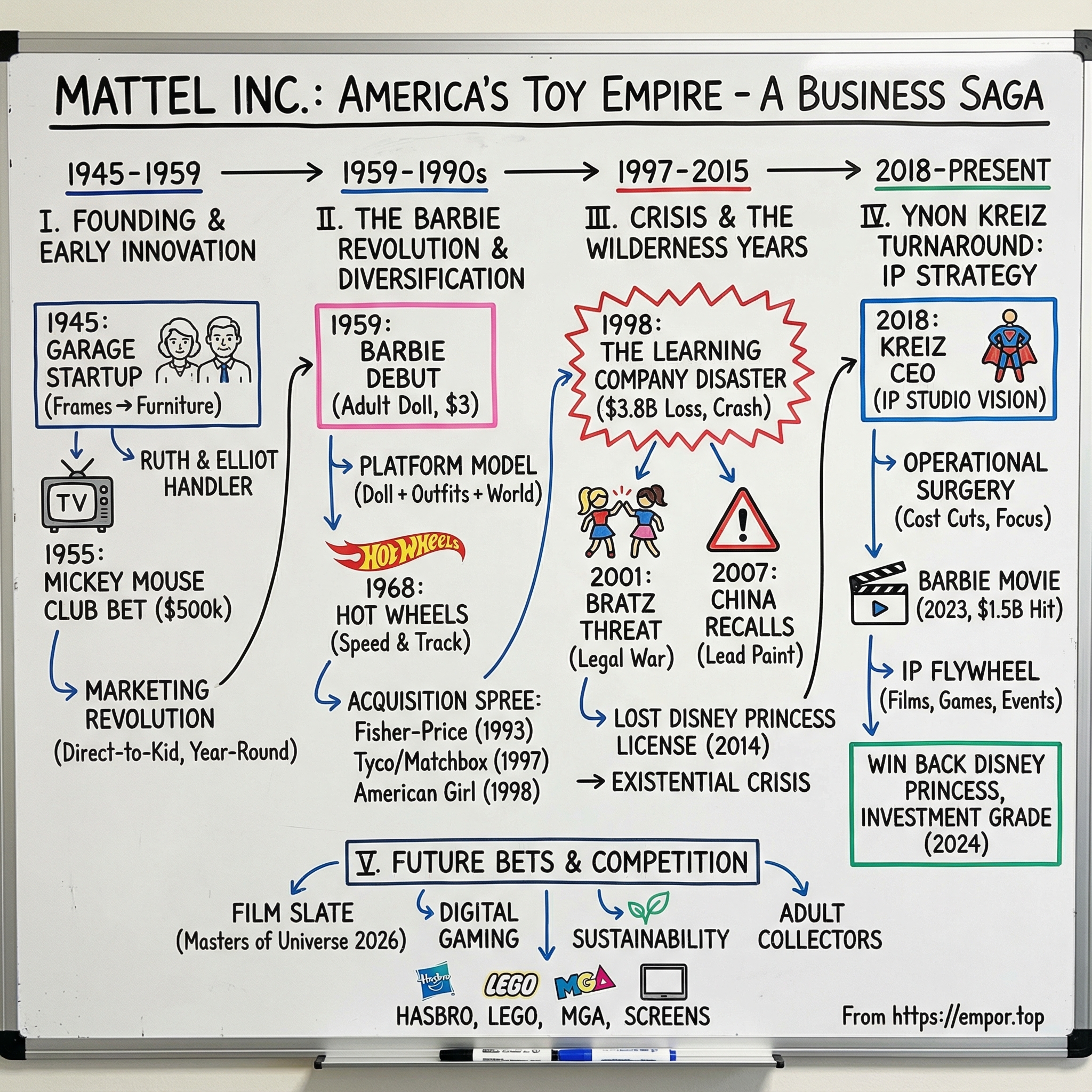

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture July 2023. Movie theaters across America look like they’ve been dipped in pink paint. Groups show up in fuchsia. Friends pose for photos under neon signs. And then the lights go down, and Margot Robbie’s Barbie takes over thousands of screens.

By the end of that first weekend, Barbie had pulled in $162 million domestically—an opening so big it set a record for a film directed by a woman. It didn’t slow down. The movie ultimately earned nearly $1.5 billion worldwide, finishing as the highest-grossing film of 2023.

For Mattel, Barbie’s owner, this wasn’t just a hit. It was a payoff. The kind of improbable payoff that only comes after decades of compounding—after reinvention, missteps, brush-with-disaster moments, and a turnaround that, in hindsight, looks almost inevitable. Almost.

Because Mattel didn’t start as a toy empire. It started as a small Los Angeles-area workshop making picture frames. And somewhere along the way, it became the world’s number-two toy company—behind LEGO—built on a portfolio that reads like a childhood highlight reel: Barbie, Hot Wheels, Fisher-Price, American Girl, UNO, Thomas & Friends, and Masters of the Universe.

In 2024, Mattel generated $5.38 billion in revenue, slightly down from the year before. The business runs across North America, International, and American Girl, with North America still doing most of the heavy lifting.

But the point of this story isn’t the scorecard. It’s the playbook.

This is a story about what it takes to steward intellectual property across generations. About how a brand can become so iconic it feels untouchable—and then suddenly feels outdated. About what happens when leadership believes it has to buy the future, pays billions for it, and nearly sinks the whole company. And about how an outsider CEO eventually walked in and reframed Mattel’s identity from “toy maker” to something closer to an IP studio that happens to sell toys.

So that’s the arc we’ll follow: How did a picture frame business become America’s toy empire? Why did it nearly collapse in the 2010s? And how did it come back—strong enough to produce the biggest movie in the world in 2023?

II. Founding Story & Early Innovation (1945–1959)

Mattel’s origin story doesn’t begin with toys. It begins with a garage in Los Angeles and a very unglamorous product: picture frames.

On January 20, 1945, three entrepreneurs—Harold “Matt” Matson and the husband-and-wife team of Ruth and Elliot Handler—started what was first called Mattel Creations. Like a lot of postwar companies, they built whatever they could sell. And at first, that meant frames.

Even the name carries an early, almost comic bit of foreshadowing. “Mattel” was stitched together from Matson and Elliot—Mat and El. Elliot later admitted they couldn’t figure out how to work Ruth into it. Which is ironic, because Ruth would become the company’s true strategic engine, and the person behind its most iconic product. From day one, she was essential—and literally missing from the masthead.

Matson didn’t stick around long. Health issues pushed him to sell his stake, leaving the Handlers in control. And as the business searched for something bigger than frames, it found an adjacent market with far more upside: miniature furniture. Mattel began producing toy furniture, and customers wanted it—enough that the company started to look less like a workshop and more like a toy maker in the making.

The Handlers were an unusually effective pairing. Elliot was the designer: the person who could imagine an object, sketch it, and make it real. Ruth was the operator and strategist: the one who understood distribution, pricing, and how demand actually gets created.

That last part mattered, because Ruth latched onto something most toy executives in the early 1950s still treated as a novelty. Television wasn’t just entertainment. It was a direct line into America’s living rooms—and, more importantly, into kids’ heads.

In 1955, she made the bet that changed the company. Mattel committed $500,000—roughly its net worth at the time—to sponsor ABC’s The Mickey Mouse Club. The money wasn’t just big. The concept was radical: year-round advertising, not a short Christmas-season push, and aimed straight at children.

Mattel’s sponsorship of Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse Club made it the first toy company to broadcast commercials to kids. Before that, toys were largely sold through parents, with marketing concentrated around the holidays. Ruth flipped the model. If you could create desire in children in March, June, and October—not just December—you could pull demand forward and make the business feel less seasonal, less fragile, and far more scalable.

The show became a hit. The bet worked. By 1958, Mattel’s sales had climbed to $14 million.

More important than the number was the lesson Ruth extracted: in toys, the real customer is often the child, even if the parent holds the wallet. Build a brand in the mind of a kid and you’re not just selling a product—you’re building a franchise. That instinct, the idea that media creates demand, would become a through-line from black-and-white TV in 1955 all the way to a pink-saturated box office phenomenon in 2023.

And Ruth’s biggest leap—the one that would turn Mattel into an empire—was still ahead.

III. The Barbie Revolution (1959–1980s)

The spark came from Ruth Handler’s living room, watching her daughter Barbara play.

Barbara and her friends weren’t treating dolls like babies that needed to be fed and tucked in. They were using paper dolls to act out grown-up lives: jobs, dates, apartments, choices. Ruth noticed the disconnect. In the 1950s, the doll aisle was basically a training ground for motherhood—babies and toddlers, nothing else. There was no doll that let a girl imagine adulthood.

Ruth’s question was simple, and quietly radical for the era: what if a doll helped girls practice becoming someone, not just caring for someone?

That idea snapped into focus in 1956 on a family trip to Europe. In Lucerne, Switzerland, Ruth came across a German doll called Bild Lilli—an adult-figured doll based on a character from a satirical comic strip drawn by Reinhard Beuthin for the newspaper Bild. It looked like the exact thing Ruth couldn’t find back home. She bought three: one for Barbara, two to bring back to Mattel as proof that an “adult” doll could exist—and could sell.

Inside Mattel, the reaction was immediate and dismissive. The mostly male leadership team couldn’t imagine mothers buying a doll with breasts for their daughters. The idea struck them as inappropriate, even absurd. They were convinced the market wasn’t ready, and they weren’t eager to risk the company’s reputation on something that would invite backlash.

Ruth didn’t back down. Over the next few years, she pushed the concept forward anyway. Back in the U.S., she reworked the doll into something Mattel could own and manufacture, collaborating with local inventor-designer Jack Ryan. And she gave the doll a name that made it personal: Barbie, after Barbara.

On March 9, 1959, Barbie debuted at the American International Toy Fair in New York. She sold for $3. Many in the industry expected her to flop—an adult-shaped fashion doll felt like a mismatch for what they thought parents wanted. Early reactions proved the tension was real: some parents were unhappy about Barbie’s chest. But kids didn’t care about the controversy. They cared that Barbie offered a new kind of play.

In her first year, Barbie sold roughly 300,000 dolls, beating expectations and establishing a new category almost overnight.

The real breakthrough, though, wasn’t just the doll. It was the system Ruth built around her.

Barbie arrived with clothing catalogs—mini lookbooks that didn’t just show outfits, but quietly trained you to want the next one. The fashions were sold separately. Then Mattel built Barbie a world: a backstory, relationships, friends, family. Barbie wasn’t a single product; she was a platform.

It was the razor-and-blade model, applied to toys. The doll got you in the door. The outfits, accessories, playsets, and new characters kept you coming back.

In 1961, Mattel introduced Barbie’s ultimate accessory: her boyfriend, Ken—named after the Handlers’ son, Kenneth. In 1963 came Midge, Barbie’s best friend. In 1964 came Skipper, Barbie’s little sister. Each addition made Barbie feel more real, and each one expanded the shelf space Mattel could claim.

Over time, the financial impact became enormous. Mattel has sold over a billion Barbie dolls. At its peak, Barbie accounted for more than 70% of Mattel’s profits—an economic engine so powerful it shaped the company’s entire identity.

But Barbie wasn’t only a product line. She became a cultural force.

Over the decades, Barbie’s résumé grew to include airline pilot, astronaut, doctor, Olympic athlete, and even U.S. presidential candidate. For generations, she modeled possibilities—less about nurturing, more about independence and aspiration. That shift was the whole point.

And the backlash began almost as quickly as the success. Starting in the 1970s, Barbie drew criticism for materialism and unrealistic body proportions. Arguments about body image, gender roles, and stereotypes would follow the brand for decades.

Still, the business takeaway was hard to miss: Ruth Handler hadn’t just launched a hit toy. She’d created a piece of intellectual property that could be extended, refreshed, debated, and reinvented—while staying lodged in popular culture for more than sixty years.

IV. The Hot Wheels Era & Diversification (1968–1990s)

If Barbie was the company’s heart, Hot Wheels became its engine.

In 1968, Mattel introduced something that felt less like a toy and more like a little piece of physics: a racing track system sold separately from the cars. The original set was a chain of bright orange road sections, punctuated by “superchargers”—battery-powered spinning wheels that grabbed a car and slingshotted it forward. It wasn’t about realism. It was about speed.

Elliot Handler, Mattel’s co-founder, wanted a boy equivalent to Barbie: a product line that could scale into a universe. He set his sights on the die-cast car market, which at the time was dominated by a British company, Lesney Products, with its Matchbox cars.

Matchbox built its business on small, realistic replicas of real production vehicles. Handler took the opposite approach. Hot Wheels would be exaggerated and aspirational—customized hot rods with oversized rear tires, superchargers, flame paint jobs, hood blowers, and outlandish proportions that looked like they belonged on a drag strip, not a street.

Then came the secret weapon: engineering.

Hot Wheels used wide, hard-plastic tires that reduced friction and rolled more smoothly than the narrow metal or plastic wheels on contemporary Matchbox cars. The result was the whole point of the brand: Hot Wheels were built to fly. They rolled easily, handled tracks better, and hit higher speeds—especially on those orange lanes.

The market responded instantly. Mattel’s first run of sixteen Hot Wheels cars hit in 1968 and detonated the category, leaving competitors like Corgi and Matchbox scrambling to catch up. They tried. Matchbox even launched its “Superfast” line in 1969, a direct response to Hot Wheels’ speed advantage. But the center of gravity had shifted.

Hot Wheels also fit perfectly into the playbook Ruth had pioneered with Barbie. The cars were the entry point. The real franchise lived in the track sets, accessories, variations, and collectibles. Over time, the brand proved unusually durable—hooking kids, then holding onto them as they grew into adult collectors and lifelong car obsessives.

With Barbie and Hot Wheels both printing cultural relevance and cash, Mattel started expanding aggressively. Over the next few decades, it went on an acquisition spree designed to turn a couple of monster hits into an all-ages toy empire.

In 1993, Mattel acquired Fisher-Price. Analysts called it the biggest toy-industry deal since Hasbro bought Tonka in 1991, and it gave Mattel a serious foothold in early childhood—plus a stronger case to challenge Hasbro at the top of the toy world.

In 1997, Mattel bought Tyco Toys. Included in that deal was Matchbox—once the rival it had built Hot Wheels to beat. Suddenly, two of the biggest names in pocket-sized cars were living under the same corporate roof.

In 1998, Mattel acquired Pleasant Company, the creator of American Girl, and also bought Bluebird Toys, a toymaker based in Swindon, England, whose crown jewel was Polly Pocket. That same year, the first American Girl retail store opened in Chicago—an early signal that toys could be more than products. They could be destinations.

Mattel bought the American Girl brand from Pleasant Rowland in 1998 for a total of $700 million.

By the late 1990s, the portfolio looked unbeatable: Barbie, Hot Wheels, Fisher-Price, Matchbox, American Girl, Polly Pocket, and a growing set of licensed properties. The open question wasn’t whether Mattel had assembled a powerhouse. It was whether it had assembled too much.

The answer would come with devastating clarity.

V. The Jill Barad Era: Hubris & The Learning Company Disaster (1997–2000)

Jill Barad was, by any measure, a marketing star. She rose through Mattel by doing the hard thing: keeping Barbie fresh through the 1980s and 1990s, turning a decades-old doll into a living pop culture machine. By the time she became CEO, she wasn’t just running a toy company. She was one of the very few women leading a Fortune 500 business, and the public treated her like proof that the glass ceiling could crack.

Wall Street treated her the same way. Under Barad—first overseeing Barbie, then running the whole company—Mattel looked unstoppable. Barbie was throwing off billions in sales. The acquisition spree looked like a master plan: cover every age bracket, own more shelf space, and keep Hasbro on its heels.

And then came The Learning Company.

In December 1998, Barad announced Mattel would acquire The Learning Company for roughly $3.8 billion in stock, pitching it as a deal that would even boost earnings the very next year. It wasn’t framed as “just another acquisition.” It was a strategic pivot: Mattel wasn’t going to be only a toy maker anymore. It was going to be a technology company too.

On paper, it sounded almost inevitable. The Learning Company was a well-known name in educational software, with titles like Reader Rabbit and Carmen Sandiego. If kids were spending more time on computers, why shouldn’t Mattel own the characters on the screen the same way it owned the characters in the toy aisle? Barad talked about “convergence,” about technology becoming the way the company would communicate with customers. She even floated the idea of turning Reader Rabbit into something like an interactive doll.

But the problems showed up fast—so fast that the warning lights were blinking before the deal was even fully complete. The Learning Company reported unexpected losses, and Mattel soon told investors its earnings would come in far below expectations. Within weeks, the software company’s founders were out.

From there, the fall was brutal. Mattel’s stock, once trading in the mid-$40s in 1998, sank to around $10 by early 2000. In less than two years, roughly $14.5 billion of market value evaporated.

Inside the business, the bleeding was constant. The Learning Company unit was reportedly losing as much as $1 million per day under Mattel’s ownership.

By the end of 1999, Mattel posted a net loss on more than $5.5 billion in sales, weighed down by restructuring charges, thousands of job cuts, and a fourth-quarter loss at The Learning Company that made the “strategic turning point” look like a trapdoor. In February 2000, Barad abruptly resigned.

The exit from the deal was even more humiliating than the entrance. In October 2000, Mattel effectively gave The Learning Company away to Gores Technology Group for no cash—just a vague claim on some future earnings. Mattel also agreed to pay off about $500 million of the unit’s debt. The losses from the sale helped push Mattel to a large net loss for 2000.

Then came the lawsuits. Shareholders filed actions in 1999 and 2000 alleging mismanagement and breach of fiduciary duty. In 2002, Mattel agreed to pay $122 million to settle.

Businessweek later tagged the deal as one of “the Worst Deals of All Time.” It earned that label because it wasn’t just expensive. It exposed a deeper truth about Mattel at the worst possible moment: the company had confused dominance in toys with competence in everything.

The investor lessons land hard. Culture matters, and toy-company instincts don’t automatically translate to software. “Synergies” that read beautifully in a pitch deck often dissolve on contact with reality. And acquisitions done to sustain momentum—because organic growth is slowing and the market expects more—are usually a sign you’re solving the wrong problem.

Most of all, the Learning Company disaster showed the danger of CEO overconfidence. Barad’s success with Barbie was real. But success in one arena doesn’t grant immunity from making a catastrophic bet in another. And this bet didn’t just miss. It put Mattel into a tailspin that would define the next decade.

VI. The Wilderness Years: Bratz, China Scandal & Near-Death (2000–2015)

The Bratz Threat

Mattel walked out of the Learning Company disaster bruised, distracted, and suddenly vulnerable. And right then—almost on cue—a new rival showed up with the kind of product that doesn’t just compete. It insults.

Bratz, created by former Mattel employee Carter Bryant for MGA Entertainment, arrived in spring 2001. These dolls were everything Barbie wasn’t: edgy, urban, more overtly multicultural, with oversized heads, pouty lips, and fashion that felt ripped straight from the early-2000s moment. Where Barbie projected polish, Bratz projected attitude.

The market moved fast. Bratz hit shelves across the U.S. in 2001, and within five years MGA had sold around 125 million products. By 2005, Bratz products were generating more than $1 billion a year—sales that, as observers put it, cut deeply into Barbie.

That year, global franchise sales reached $2 billion. By the next year, Bratz held roughly 40% of the fashion-doll market.

The pressure showed up everywhere. In 2004, Bratz reportedly outsold Barbie in the U.K. and Australia. In 2005, Barbie sales fell 30% in the United States and 18% worldwide, with much of the drop attributed to Bratz’s popularity. Barbie revenue slid from a peak of $1.8 billion in 2002 to below $1.5 billion by 2007.

Mattel’s response wasn’t a product breakthrough. It was a lawsuit.

The first target was Bryant himself. Mattel alleged copyright infringement, trade secret misappropriation, and breach of contract. The core argument was simple: Bryant had signed an employment agreement saying he would assign to Mattel any “inventions” created during his time there—meaning, Mattel claimed, Bratz was theirs.

What followed was a legal war that ate years of attention. Bryant settled with Mattel before trial, but Mattel pushed ahead against MGA. In 2008, a federal jury agreed with Mattel and awarded $100 million, and the district court went further—ordering a transfer of property and issuing an injunction that blocked MGA from marketing Bratz.

Then it flipped. On July 22, 2010, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that ownership of Bratz belonged to MGA Entertainment, rejecting the district court’s decision that would have forced MGA to forfeit the entire brand.

The scale of the fight became its own headline. Court filings described nine years of litigation that racked up more than 10,000 docket entries, included two multi-month jury trials, and generated an astonishing discovery process—around 11.5 million pages and 400 depositions.

In the end, it was a pyrrhic saga for both sides: years of management distraction, enormous legal costs, and a brand battle that consumed energy Mattel desperately needed elsewhere.

The China Lead Paint Crisis

And then, as if the Bratz fight wasn’t destabilizing enough, 2007 delivered a different kind of blow—one that wasn’t about taste or trend, but trust.

In August and September 2007, Mattel announced a series of product recalls totaling more than 20 million toys. Some were recalled for excessive lead paint; others for magnets that could come loose. The recalled toys had been made in China.

Mattel later agreed to pay $2.3 million in civil penalties for violating a federal lead paint ban related to the 2007 recalls—what the Consumer Product Safety Commission described at the time as the highest civil penalty in the agency’s history for its regulated product violations.

The mechanics of the crisis were ugly and revealing. The lead paint traced back to a subcontractor in China that violated Mattel’s safety standards to cut costs. This wasn’t a small quality miss—it was a failure mode inherent in a sprawling outsourced supply chain.

Then the story got worse. Subsequent reporting found that Mattel had misled the public to believe Chinese suppliers were responsible for both the lead paint and the magnets issue, when the magnet hazard was actually tied to an internal Mattel design flaw.

CEO Robert Eckert took the hit publicly, appearing on camera to apologize and lay out remediation steps. But the consequences lingered: eroded trust, heavier regulatory scrutiny, and a cost structure that only got harder to defend in a business built on thin margins and seasonal spikes.

The Disney Princess Loss

By the mid-2010s, the compounding damage was catching up with Mattel—and then it lost one of the most valuable licenses in toys. In September 2014, Disney handed the Princess license to Hasbro.

Former Mattel employees later pointed to the 2013 release of Ever After High as a breaking point in the relationship. Chris Sinclair, a Mattel board member who became CEO in January, agreed: “We got too competitive with them on Ever After High,” he said.

The loss was brutal. Mattel was suddenly staring at an estimated $400 million hole in revenue from the Disney licenses, just as the company was already cycling through leadership and trying to stabilize the core business.

Barbie sales declined sharply from 2014 to 2016. Mattel churned through CEOs. Bryan Stockton lasted barely three years before being ousted. The stock sank. Activist investors circled.

By 2017, the situation had crossed from “turnaround needed” into something darker: an existential crisis. The company that had once defined the toy aisle looked like it had simply… lost the plot.

VII. The Ynon Kreiz Turnaround (2018–2023): IP Goldmine Strategy

The New Playbook

By 2017, Mattel didn’t just need a new product cycle. It needed a new identity. And the person the board picked to do that wasn’t a toy lifer.

Ynon Kreiz is an Israeli-American executive whose career was built in media: chairman and CEO of Fox Kids Europe from 1997 to 2002, chairman and CEO of Endemol from 2008 to 2011, and chairman, CEO, and president of Maker Studios from 2012 to 2016. In April 2018, he became Mattel’s CEO, replacing Margo Georgiadis, and in May he also became chairman of the board.

That background mattered. Kreiz didn’t look at Mattel and see a struggling manufacturer fighting for shelf space. He saw a library. A catalog of characters and brands that had been treated like products, when they could have been treated like franchises.

The turnaround started with hard operational surgery. The restructuring was aggressive: Mattel cut its workforce by more than a third, closed or consolidated factories, and reduced the number of items it manufactured by more than 35%. Over three and a half years, the effort took $1.1 billion out of annual costs.

Over roughly that same period, earnings (before interest, taxes and depreciation) rose eight-fold.

But the bigger shift was strategic. Kreiz repositioned Mattel from “toy maker” to an IP-driven toy and family entertainment company—one that manages brands the way a studio manages franchises. With properties like American Girl, Barbie, Fisher-Price, Hot Wheels, Thomas & Friends, and UNO, he argued Mattel should be growing through film, television, digital games, and other media. “We look at Marvel as a very good analogy,” Kreiz said.

The Studio Strategy

Kreiz’s core insight was simple: Mattel was sitting on an undermonetized goldmine. These weren’t just toy lines. They were stories people already knew—characters and worlds with decades of cultural memory baked in.

So Mattel expanded its entertainment push, building more offerings across products, digital games, publishing, and live events. As of 2024, it had 16 motion pictures in production with major studio partners.

The boldest test of the whole strategy was Barbie. And the most counterintuitive choice Mattel made was not trying to sand the movie down into a “safe” brand extension. Instead, it handed the creative keys to filmmaker Greta Gerwig and star Margot Robbie.

Robbie was all-in. She wanted a female-driven, superhero-scale movie for the masses. The production made an extra lap to lock in Ryan Gosling as Ken—an expense that raised costs, but proved “worth every nickel” in the end.

Before release, there was a different fear: that the movie would be “too woke,” especially coming from the director of Little Women. The film was widely screened to the press. Then opening weekend arrived, and the question flipped from “Will this work?” to “How big can this get?” Moviegoers gave it an A CinemaScore, and it delivered the biggest opening of 2023: $162 million domestic and $356 million worldwide.

The Barbie Movie Phenomenon

Barbie didn’t just become a hit. It became Warner Bros.’ highest-grossing film ever, finishing at $1.44 billion worldwide and surpassing the longtime leader, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2.

It ended 2023 as the year’s biggest movie and the 14th highest-grossing film of all time. It earned eight Academy Award nominations and won Best Original Song.

For Kreiz, it was proof that his thesis wasn’t theory. It was a flywheel. As he put it: “We’re very much about embracing culture, creating cultural moments, cultural touch points and make sure that we take brands that are timeless and make them timely.”

And the halo effect showed up in the core business. In a tough toy market, Barbie helped Mattel feel the downturn less sharply. The movie lifted sales of dolls, accessories, and Dreamhouses, helping the company beat Wall Street’s expectations with a 9% increase in third-quarter sales.

Then came a symbolic win that would have felt unthinkable a few years earlier: Mattel won back the Disney Princess license. After losing the rights to produce Disney Princess and Frozen dolls to Hasbro in 2014, Mattel regained the license.

Investors took it as a signal that Mattel’s credibility—and relevance inside the entertainment ecosystem—had snapped back. The news sent shares up 11%, aligning neatly with Kreiz’s plan to get Mattel more deeply entrenched in major entertainment properties.

And by 2024, the turnaround had a final stamp of legitimacy: Mattel received an investment grade rating from the three major credit rating firms.

VIII. The Hasbro Wars & Competitive Landscape

The toy business has always been a knife fight. And for most of Mattel’s life, the other hand holding the blade has been Hasbro.

These two have spent decades trading punches over the same prize: the right to sit at the center of childhood. That fight plays out in three places—licenses, shelf space, and mindshare—and licensing is where the damage can be immediate.

The Disney Princess saga is the clearest example. When Mattel lost the license to Hasbro in 2014, it wasn’t just a hit to pride. It opened up an estimated $400 million hole in revenue and broadcast to the market that Mattel was slipping. When Mattel won the license back in 2022, it read like a reversal of that story: a signal that the Kreiz-era Mattel could compete—and win—inside the entertainment ecosystem again.

But even if Hasbro is the rival everyone knows, Mattel doesn’t get to play on a two-team field. The modern competitive landscape is crowded, global, and brutally fast-moving:

LEGO's Dominance: LEGO, the Danish construction-toy powerhouse, has become the world’s largest toy maker by revenue, leapfrogging Mattel. Its licensed sets—Star Wars, Harry Potter, Marvel—plus premium positioning give it a mix of brand devotion and pricing power that’s hard for anyone else to match.

MGA Entertainment: The company behind Bratz, L.O.L. Surprise, and Miniverse is still a recurring headache for Mattel: trend-driven, willing to take swings, and very good at capturing the moment when kids decide the old thing suddenly feels uncool.

Spin Master: The Canadian player that built hits like Paw Patrol and Hatchimals has grown into a serious competitor, especially in boys’ categories and licensing-driven franchises.

The Retail Apocalypse: Then there’s the distribution shock. Toys "R" Us going bankrupt in 2018 wiped out the toy industry’s biggest specialty retailer, pushing even more volume through Walmart, Target, and Amazon. That consolidation didn’t just change where toys are bought—it tilted bargaining power toward the retailers who control the shelves and the search results.

Mattel’s response has been to stop fighting the last war. The playbook now is multi-pronged: double down on the power brands, use entertainment to generate demand that doesn’t depend on any one retailer, and build a direct relationship with fans through Mattel Creations. In that framing, movies aren’t just “marketing.” They’re a flywheel—cultural events that can sell toys, create new fans, and pay for themselves along the way.

IX. Business Model Deep Dive

Economics of the Toy Business

On the surface, toys look like the happiest business in the world. Under the hood, the economics are unforgiving. A few structural realities make it hard to run, and even harder to run well:

Hit-Driven Nature: Toys don’t behave like toothpaste. Demand is shaped by trends, licenses, and whatever just captured kids’ attention this month. When you catch a wave, you can look like a genius. When you miss one—or lose a major license—the fall shows up fast.

Extreme Seasonality: The industry lives and dies by the holidays. More than 40% of sales land in the fourth quarter, which means companies spend most of the year building inventory, placing bets, and praying they don’t get stuck with a mountain of product in January.

Retail Dynamics: Shelf space is a zero-sum game. Retailers have leverage, and they use it—pushing for co-marketing money, protection against markdowns, and friendly payment terms. Returns are part of the terrain, not an exception.

Manufacturing Costs: Most toys are made in China, which keeps costs down but brings its own kind of fragility. Tariffs, currency swings, shipping disruptions, and geopolitical tension can all hit a toy company’s margins with very little warning.

Marketing Intensity: Toys have to stay loud to stay alive. It takes real spending to keep brands visible—now spread across TV, YouTube, influencers, app stores, and whatever platform kids migrated to last week.

The Power Brands Strategy

Kreiz’s big operational insight was focus: stop trying to make every brand matter equally, and start treating the best ones like the engines they are.

In 2024, nearly 60% of Mattel’s net sales came from North America, with the rest coming from international markets. But within that mix, the weight is even more concentrated. Barbie, Hot Wheels, Fisher-Price, American Girl, and games like UNO are the power brands—the names that generate the bulk of profits and justify the most investment. Everything else either gets fixed, shrunk, or quietly retired.

And crucially, the strategy isn’t just “sell more toys.” It’s franchising: extending the same IP across categories—products, media, fashion collaborations, and experiences like American Girl stores, and now film. Each extension is designed to do two things at once: bring in incremental revenue and keep the brand culturally present, so the toy aisle doesn’t have to do all the work by itself.

International Strategy

If North America is the base, emerging markets are the long-term upside. But international growth comes with friction. What resonates in one country can fall flat—or backfire—in another. Barbie is the clearest example: cultural perceptions of body image and aspiration vary widely around the world.

Layer on currency volatility and retail systems that don’t look like the U.S., and “global expansion” stops sounding like a simple growth lever. It becomes what it really is: a careful, country-by-country act of localization, risk management, and patience.

X. Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Porter’s Five Forces is a quick way to pressure-test the toy business from the outside in. And when you run Mattel through the framework, you get a picture that looks a lot like the last eighty years of its history: hard to win, easy to lose, and brutally rewarding if you own the right brands.

1. Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM

The big barriers are real: decades of brand equity, relationships with the major retailers, manufacturing know-how at scale, and licensing ties with entertainment companies. But toys also have a sneaky “anyone can take a shot” quality. You don’t need a massive factory to get started, crowdfunding can finance a first run, and a single viral moment on TikTok can turn a small product into a national obsession (Squishmallows is the poster child). Getting in is possible. Staying in is the hard part.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MEDIUM

A lot of manufacturing is concentrated in China, but Mattel isn’t hostage to one supplier. There are many contract manufacturers, and for standard toys the production work is fairly commoditized. The leverage shifts when you need specialized components, and it shifts again as ESG expectations and labor pressures rise—because “cheap and flexible” becomes “more expensive and more scrutinized.”

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: in toys, the gatekeepers have gotten bigger and fewer. Walmart, Amazon, and Target account for a huge share of distribution, and they know it. That gives them the power to push for discounts, favorable terms, and co-marketing spend. Meanwhile, consumer loyalty is fragile. Kids have endless options, and switching is painless. Even iconic brands have to re-earn attention every season.

4. Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

Toys aren’t competing only with other toys. They’re competing with everything a kid can do instead: video games, tablets, streaming, social media. Screen time is the obvious substitute, but so is the broader shift toward experiences—activities and travel—over more stuff. The underlying question for the whole category is whether traditional play keeps its share of childhood as those alternatives keep improving.

5. Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Mattel isn’t in a cozy oligopoly. It’s in an all-out brawl against Hasbro, LEGO, Spin Master, MGA, and increasingly strong private labels. The fighting gets fiercest when it matters most—holiday season—when price wars and markdowns can chew up margins. Add in the constant race to create the next hit, plus the bidding wars for IP licenses, and rivalry stays permanently turned up.

Overall Industry Attractiveness: MEDIUM

This is a tough industry to operate in and a harder one to dominate consistently. But if you own exceptional brands—IP that travels across products, media, and generations—you can build a moat that isn’t just about what’s on the shelf this year. It’s about what people already love, remember, and want to pass down. That’s the game Mattel is now trying to play on purpose.

XI. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

Mattel does get real advantages from scale. When you’re producing at massive volume through China-based manufacturing partners, you can negotiate better terms and spread fixed costs across more units. And when you’re marketing a portfolio of big brands, each dollar of ad spend can work harder.

But scale in toys has a ceiling. This isn’t a winner-take-all industry. Fads erupt out of nowhere, niche brands can break through, and smaller players can win whole categories without ever matching Mattel’s size.

2. Network Effects: LIMITED

There are some light network effects in physical play. Hot Wheels gets more fun when you can connect tracks, expand sets, and build bigger worlds. Barbie has a social dimension too—playdates, shared characters, shared stories.

But these aren’t software network effects where value explodes as users join. They’re softer, product-based dynamics. Collector communities help, but they’re more of a stabilizer than an engine.

3. Counter-Positioning: HISTORICALLY YES, NOW UNCERTAIN

Mattel’s biggest wins were classic counter-positioning. Barbie broke away from baby dolls and gave girls a different kind of imaginative play. Hot Wheels rejected realism and beat Matchbox with speed and spectacle.

The risk today is that someone else gets to run that play against Mattel. Digital-first brands, or values-aligned challengers that speak more directly to what modern parents want, can make legacy icons feel behind the times—fast.

4. Switching Costs: LOW-MEDIUM

There is some lock-in. Hot Wheels track systems and car collections accumulate. Barbie accessories and worlds can carry over. And nostalgia is a powerful force—parents often buy what they remember.

But switching costs in kids’ toys are still low. Children move on quickly, and parents can be brutally price-sensitive. If the new thing feels cooler, the old ecosystem doesn’t protect you for long.

5. Branding: STRONG

This is the core of Mattel’s power. Barbie is one of the most valuable toy brands in the world because it’s instantly recognizable, emotionally loaded, and multi-generational. The 2023 movie didn’t create that power—it proved it could be reactivated at massive scale.

Hot Wheels and Fisher-Price carry their own weight here too, with deep trust and familiarity baked into the names.

6. Cornered Resource: YES (IP)

Mattel’s other major advantage is what it owns. Barbie, Hot Wheels, Masters of the Universe, UNO—these are scarce assets protected by rights and trademarks, with decades of cultural memory attached.

That scarcity matters because it can’t be copied. Competitors can make a fashion doll or a die-cast car, but they can’t make Barbie or Hot Wheels. And when Mattel pairs that IP with entertainment partners, it creates a content engine that’s hard to replicate from scratch.

7. Process Power: LIMITED

Mattel has decades of experience designing and launching toys, and that institutional muscle shows up in everything from iteration speed to brand management.

But process power is limited because the craft isn’t secret. Competitors can hire great designers too. And with manufacturing largely outsourced, there’s less proprietary advantage embedded in the production process.

Dominant Powers: BRANDING and CORNERED RESOURCE

In the end, Mattel’s durable edge comes down to two things: brand equity and ownership of iconic IP. The film strategy supercharges both—refreshing cultural relevance while extending that IP far beyond the toy aisle.

XII. The Modern Mattel Playbook & Strategic Bets

What Worked

Focus and Pruning: In the Kreiz era, Mattel stopped trying to be a sprawling toy conglomerate and started acting like a portfolio manager. Underperforming brands and distractions got cut so the winners could get the attention, shelf space, and creative energy they’d earned.

IP-to-Film Flywheel: The new thesis is that toys aren’t the whole business—they’re one output of the IP. Entertainment creates demand, demand sells toys, the toy aisle reinforces the brand, and the strengthened brand justifies bigger swings in entertainment. Barbie proved that loop can actually spin.

Creative Partnerships: The counterintuitive move was giving real control to filmmakers instead of treating the movie like a two-hour commercial. Handing Barbie to Greta Gerwig and Margot Robbie without sanding off the edges was risky for a brand owner. It also turned out to be the point.

Nostalgia + Relevance: Mattel leaned into what people loved, without pretending the culture hadn’t changed. Diverse Barbies, more body-positive messaging, and storytelling that felt of-the-moment helped legacy brands feel current instead of trapped in amber.

Financial Discipline: The turnaround wasn’t powered by vibes. It was powered by a tighter cost structure and a healthier balance sheet—making it possible to invest again without betting the company.

Current Strategic Bets

Film Slate: Barbie was the breakthrough, but Mattel is trying to make it the beginning, not the exception. Mattel Films has built a slate that reaches across the catalog: Barney (produced by Daniel Kaluuya), Bob the Builder (with Anthony Ramos starring), Polly Pocket (written by Lena Dunham and starring Lily Collins), Rock 'Em Sock 'Em Robots (starring Vin Diesel), an American Girl movie, and a Hot Wheels movie produced by J.J. Abrams’ Bad Robot. Film versions of Barney, Polly Pocket, the card game Uno, and Rock 'Em Sock 'Em Robots have also been described as in the works.

The clearest near-term test is Masters of the Universe. Mattel Films and Amazon MGM Studios’ live-action feature film is set for an exclusive theatrical release worldwide on June 5, 2026.

Hot Wheels is another major swing: Jon M. Chu signed on to direct a live-action Hot Wheels movie for Mattel and Warner Bros. Pictures.

Gaming: Mattel’s 2025 guidance included an expectation to increase investments in digital games—a sign the company is still pushing to meet kids where they already spend time.

Adult Collectors: Mattel is also leaning into a customer segment that’s less seasonal and less fickle: adults who grew up with these brands and now collect them. Lines like Barbie Signature and the Hot Wheels Red Line Club go straight at enthusiasts who are willing to pay premium prices.

Sustainability: Kreiz also set big sustainability goals: shifting to 100% recycled, recyclable, or bio-based materials across products and packaging, and reducing plastic packaging per product by 25% by 2030.

Open Questions

Can Mattel replicate Barbie’s film success, or was it a once-in-a-generation cultural moment? Masters of the Universe in 2026 will be an early read on that.

Is Mattel actually becoming a media company, or is it still a toy manufacturer that occasionally lands a blockbuster?

What happens if the film slate underwhelms? Many projects are in development, but most toy-to-film attempts don’t work.

And the biggest strategic question of all: how does Mattel compete with screens for kids’ attention in a world where play is increasingly digital?

XIII. Bear Case vs. Bull Case

Bear Case

Structural Decline: Kids are spending more of their time on tablets, video games, and streaming. If play keeps shifting toward screens, the whole physical-toy category could face a slow, grinding decline.

One-Hit Wonder: Barbie the movie may be lightning in a bottle. Hollywood is full of toy adaptations that never found a story people actually wanted. If investors assume one blockbuster means a repeatable machine, they may be pricing in a future that doesn’t arrive.

Retail Risks: The power in retail has concentrated. Amazon looms, Walmart and Target still dictate shelf space, and everyone is allergic to excess inventory after the holidays. That combination tends to mean margin pressure, tougher negotiations, and occasional channel conflict as brands push direct-to-consumer.

China Exposure: Mattel is still exposed to the realities of global manufacturing: geopolitical tension, tariffs, shipping disruptions, and the simple fact that heavy concentration in China creates a single structural fault line.

Licensing Vulnerability: Mattel benefits from major partnerships—until it doesn’t. Licenses like Disney and WWE can change hands, and Mattel’s own Disney Princess experience is the reminder: losing a license can punch a hole in the P&L overnight.

Execution Risk: Running a film and TV pipeline is not the same as running a toy company. Development is slow, hits are rare, and creative businesses don’t obey forecasting models. Even with great partners, most projects won’t become cultural events.

Bull Case

IP Goldmine: Few companies own a catalog like this. Barbie, Hot Wheels, Fisher-Price, American Girl, UNO—brands with deep recognition that can be extended far beyond the toy aisle. For decades, a lot of that potential sat on the shelf. Barbie proved it doesn’t have to.

Barbie Proof of Concept: The film showed what happens when the IP is activated at full scale: theatrical revenue, licensing, and merchandise all reinforcing each other. If that flywheel works even occasionally, Mattel starts to look less like a seasonal manufacturer and more like a higher-multiple IP business.

Kreiz Execution: The bull case leans heavily on management. Kreiz has already done the unglamorous work—cutting costs, improving the balance sheet, regaining Disney Princess, and building a real entertainment strategy. In turnarounds, the track record matters.

Multiple Revenue Streams: Mattel now has more than one way to win. Toys still matter, but licensing, film participation, gaming, and experiences diversify where growth and profits can come from—and they don’t all move in lockstep.

Resilient Demand: Toys haven’t gone away. Parents still buy them, and nostalgia is a real spending force for adult collectors. Plus, physical play offers developmental benefits that screens don’t replicate, which keeps traditional toys anchored in family life.

Optionality: With 16 films in development, Mattel doesn’t need all of them to work. It needs one or two to hit. That’s the appeal: the downside of a miss is limited, but the upside of a breakout can be enormous.

Financial Health: The turnaround isn’t just creative—it’s financial. Mattel kept strengthening its balance sheet, repurchased $400 million of shares in 2024, improved its leverage ratio, and said it was tracking ahead of schedule toward its $200 million cost-savings target by the end of 2026.

XIV. Key Metrics & What to Watch

If you want to understand whether Mattel’s comeback is durable—or just a great moment—there are a few numbers that tell the story faster than any press release:

1. Gross Billings by Power Brand (especially Barbie and Hot Wheels)

This is the cleanest read on whether the franchises are still winning in the aisle. In Q4 2024, worldwide Gross Billings for Dolls were $735 million, down 4% as reported, driven primarily by declines in Barbie. The big thing to watch is simple: does Barbie’s post-movie lift hold up, or does it fade as the cultural moment cools?

2. Gross Margin Trends

Margins are where strategy becomes reality. In Q4 2024, gross margin came in at 50.7%, up 190 basis points. That kind of improvement usually means a mix of better pricing, tighter cost control, and a healthier product mix. If Mattel can keep expanding margins, it supports the argument that this is no longer just a hit-driven toy maker—it’s becoming a better, more resilient business.

3. Film Revenue and Profit Participation

This is the new variable that could change the whole model. Film participation can be high-margin, but it’s also lumpy and unpredictable. The key isn’t just whether projects get announced—it’s which ones actually move into production, and how Mattel structures its economics when they do.

Beyond those three, the supporting indicators matter too: international growth (especially in Asia), direct-to-consumer traction, licensing revenue growth, and retail inventory levels, which tell you whether Mattel’s relationships with the big retailers are healthy—or quietly strained.

XV. Epilogue & Reflections

Recent Developments (2024-2025)

By the end of the Barbie-movie cycle, Mattel wasn’t talking like a company that had simply survived. It was talking like a company that had regained control of its own story.

CEO Ynon Kreiz put it plainly: “2024 was a year of strong operational excellence for Mattel with topline growth in the fourth quarter. Our priorities for the year were to grow profitability, expand gross margin, and generate strong free cash flow and we achieved all three objectives, well ahead of expectations.”

And looking into 2025—Mattel’s 80th anniversary—Kreiz signaled more of the same: “As we progress through 2025, our 80th anniversary year, we look forward to growing both top and bottom line and continuing to successfully execute our multi-year strategy.”

By December 2025, Mattel’s market cap stood at $6.51 billion, making it the world’s 2626th most valuable company.

Meanwhile, the entertainment pipeline kept moving from pitch deck to production schedule. Masters of the Universe with Amazon MGM remained on track for a June 2026 release, with Nicholas Galitzine cast as He-Man and Jared Leto as Skeletor. And Mattel Studios announced an animated Barbie film with Illumination, to be released by Universal Pictures—its first theatrically released animated Barbie movie after years of straight-to-video releases.

What the Future Holds

The question hovering over everything is identity. Is Mattel a toy company that learned to make entertainment, or an entertainment company that happens to sell toys? The distinction isn’t philosophical—it shapes how investors value the business, because entertainment companies tend to command higher multiples than manufacturers.

The next wave of change could come from technology as much as from storytelling. AI and personalization may reshape how toys are designed and marketed. Digital collectibles and metaverse-style experiences could give legacy brands new places to live. Sustainability pressures will likely intensify too, potentially raising costs, but also creating real opportunities to differentiate.

And then there’s the biggest variable of all: how kids play. If the long-term drift away from physical toys continues, Mattel will have to keep evolving. If parents and kids swing back toward tactile, screen-free play, Mattel is unusually well-positioned to benefit.

Biggest Surprises

Looking back, a few things about Mattel’s arc still feel hard to believe:

The Near-Total Collapse: By 2015, Mattel had lost Disney Princess, Barbie was sliding, leadership turnover had become routine, and the company looked like it was fading. The speed and scale of the reversal under Kreiz wasn’t the obvious outcome—it was the improbable one.

The Barbie Movie’s Scale: A toy company releasing the biggest film of 2023, grossing nearly $1.5 billion, wasn’t just a nice upside case. It was the kind of result that forces an entire industry to update its assumptions.

The Value of IP Management: Mattel’s comeback clarified something that’s easy to miss when you’re staring at plastic on a shelf: the highest-leverage asset isn’t the manufacturing. It’s the franchise. The shift from “making items” to “managing worlds” is where the value got unlocked.

Lessons for Founders & Investors

Brand Equity Compounds: Barbie and Hot Wheels have been accumulating awareness for more than sixty years. But compounding isn’t automatic. Without reinvention and relevance, heritage turns into baggage.

Undermonetized IP Is a Hidden Asset Class: Plenty of companies own valuable IP that doesn’t throw off much cash—because they never built the machine to extend it. Spotting that gap, and closing it, can create outsized returns.

Turnarounds Require Both Strategy and Execution: Kreiz brought the strategic reframing—Mattel as an IP company, not just a toy maker—but the turnaround only worked because it was paired with operational discipline: cost reduction, portfolio pruning, and better focus.

Outsiders Sometimes See What Insiders Miss: Kreiz wasn’t formed by the toy industry. His media background let him see Mattel’s library the way Hollywood sees it: as adaptable, bankable franchises.

Cultural Relevance Must Be Earned: Even icons can go stale. Mattel didn’t get Barbie’s cultural moment through corporate control. It got it through creative partnerships, product evolution, and storytelling that met the moment.

Strategic Patience Pays: Barbie launched in 1959. The blockbuster film arrived in 2023—64 years later. Enduring brands reward decade-long thinking, not quarter-to-quarter panic.

Ruth Handler saw possibility in a German doll and built a platform for imagining adulthood. Seven decades later, Greta Gerwig and Margot Robbie translated that platform into a global cultural event. The connective tissue is simple: imagination, turned into IP, and stewarded long enough to matter.

That’s the Mattel story. And it’s still being written.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music