Lam Research: The Silicon Valley Equipment Giant Behind Every Chip

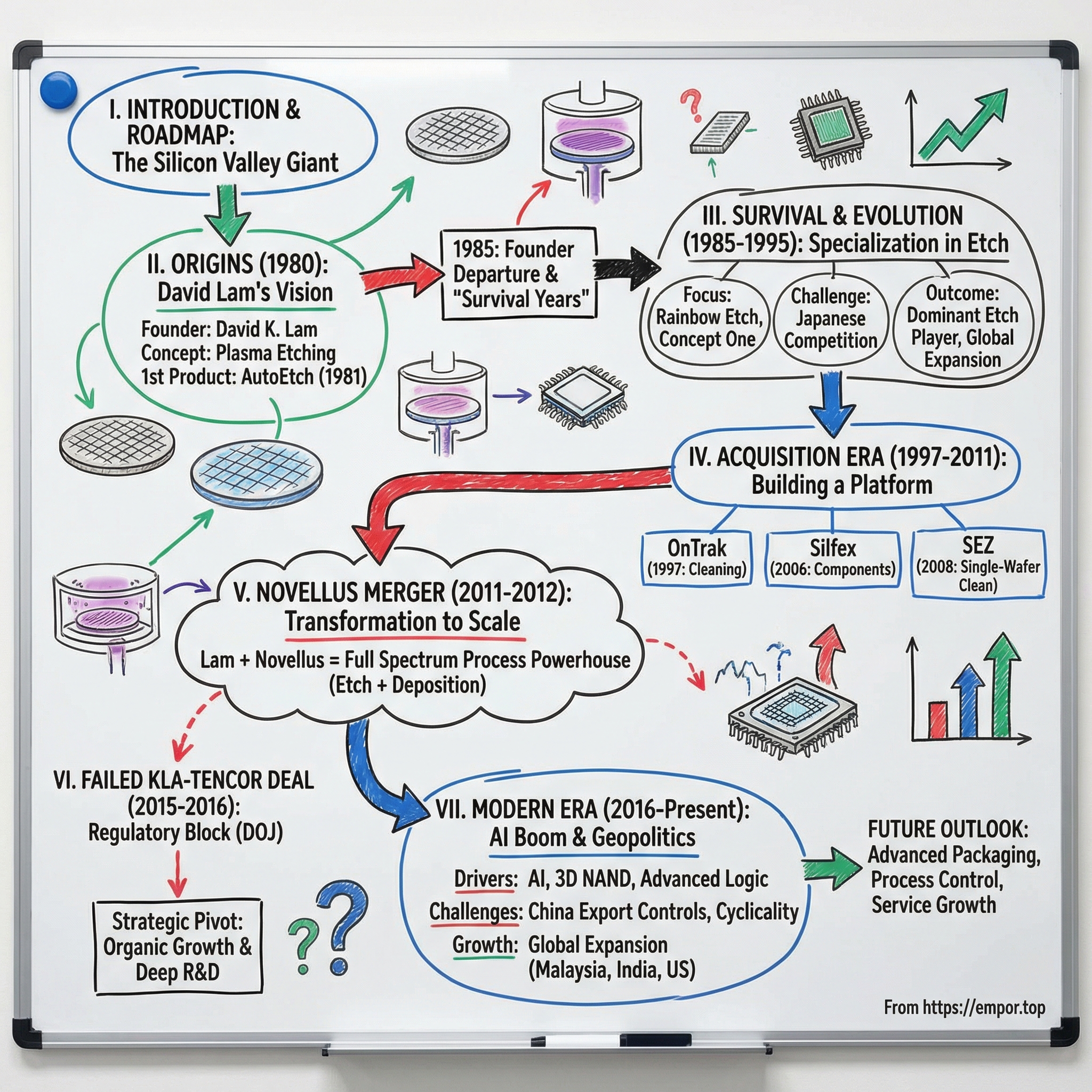

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Inside a cleanroom in Hsinchu, Taiwan, a machine the size of a delivery truck fires plasma at a silicon wafer with atomic precision. Billions of transistors take shape, layer by layer, etch by etch. The logo on the tool reads Lam Research. Most people have never heard the name. Yet without Lam’s equipment, your smartphone, your laptop, the data center answering your AI questions, and the car guiding you home tonight wouldn’t exist. Full stop.

By late 2024, Lam commanded roughly a third of the global semiconductor equipment market and generated more than sixteen billion dollars in annual revenue. A year later, it was producing over five billion dollars in quarterly revenue, up about twenty-two percent year over year. Its market cap had surged past a quarter-trillion dollars. Those are staggering numbers for a company almost nobody outside the industry can name.

So here’s the question that anchors this whole story: how did a refugee engineer’s startup, founded in a modest Fremont office in 1980, become a critical enabler of virtually every advanced chip on Earth? The answer runs straight through plasma physics, brutal survival years, transformative mergers, and a global chessboard where geopolitics now shapes who can build what, and where.

At its core, Lam builds wafer-fabrication equipment for front-end processing. In plain English: these are the machines that create the transistors and the microscopic wiring that connects them. If chipmaking is like constructing a skyscraper, Lam makes the tools that pour the concrete and lay the electrical lines—except each “floor” is measured in nanometers, and every imperfection compounds across hundreds of steps. Lam dominates two of the most important of those steps: etch, which carves patterns into the wafer, and deposition, which lays down new material with extreme uniformity. Together, those processes make up roughly half the work of manufacturing a modern chip.

This is a story about technical innovation becoming a moat, about consolidation deciding who gets to survive, and about navigating the most complex political and economic environment the semiconductor industry has ever faced. And ultimately, it’s a story about why the least glamorous part of tech—the machines that make the machines—may be one of the most powerful ways to participate in the AI revolution.

II. Origins: David Lam's Vision & The Founding Story

It was 1980. Silicon Valley was still half-orchard, half-industrial park, but the trajectory was clear: semiconductors were going to eat the world. In Fremont, California, a quiet, methodical engineer named David K. Lam was about to make a bet that looked narrow at the time—one new kind of manufacturing tool—but would end up shaping how nearly every advanced chip gets made.

David Lam’s path to that moment reads like a twentieth-century migration story. He was born in China into a large family—seven boys and one girl—then swept into the turmoil of the 1940s as his family fled to Vietnam. Later they moved again, this time to Hong Kong. There, Lam attended Pui Ching Middle School and excelled enough to earn a scholarship to the University of Toronto. From Canada he headed to MIT, finishing a master’s degree and then a PhD in chemical engineering by 1973. Along the way, he studied plasma physics—an academic thread that would later become his commercial edge.

Before founding his own company, Lam worked at Texas Instruments on plasma etching research, then moved through Hewlett-Packard and Xerox. And at each stop, the same mismatch kept showing up: chipmakers were still using wet chemical processes to etch patterns into silicon wafers. Wet etching worked, but it was blunt. As features shrank, the industry needed something controllable and repeatable at far smaller scales. The old method was like trying to do fine art with a mop.

The market structure made the opportunity even clearer. In 1980, semiconductor equipment was a fragmented business—dozens of companies, lots of point solutions, plenty of incremental upgrades. At the same time, Japanese competitors were surging. Japan’s share of the global semiconductor equipment market climbed from nearly nothing in the late 1970s toward about half by the end of the decade. For American equipment makers, “innovate or perish” wasn’t rhetoric. It was the scoreboard.

Lam saw the opening and moved. With seed capital from his mother—one of those small details that captures the trust and improvisation behind immigrant entrepreneurship—he founded Lam Research Corporation. The thesis was simple but audacious: plasma etching would replace wet chemistry as the standard way to carve features into wafers. Plasma could remove material with far more precision, enabling geometries wet processes couldn’t touch. In Lam’s view, the industry was ready to swap a blunt instrument for a scalpel.

A year later, in 1981, Lam shipped the AutoEtch system—the first fully automated plasma etching machine. The name sounded modest. The impact wasn’t. Automation meant consistency. Consistency meant yield. And yield, in semiconductor manufacturing, is everything. Customers didn’t just see a better tool; they saw the kind of capability the next generation of chips would require.

The company grew quickly enough to go public in 1984, raising twenty million dollars on the NASDAQ. Lam became the first Asian American to take a company public on that exchange—a milestone that underscored both the magnitude of the accomplishment and how rare it still was at the time. The IPO put real fuel in the tank: capital to build, to compete, and to survive in an industry where the winners were the ones who could keep shipping the next tool, not just the first one.

And then came the twist. In 1985—just five years after founding the company—David Lam left to join Link Technologies. He stayed on Lam Research’s board for five years, but day-to-day leadership moved to others. For a young hardware company still tied tightly to its founder’s technical vision and relationships, this was the kind of moment that could end the story. Plenty of semiconductor equipment startups never made it past a founder departure.

Whether Lam Research had become durable enough to stand on its own was suddenly the only question that mattered.

David Lam’s own story kept going. He later formed the David Lam Group for management consulting and venture investment, and became chairman of Multibeam Corporation. In 2013, he was inducted into the Silicon Valley Engineering Hall of Fame alongside Intel founders Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore—fitting company for someone whose work helped turn Moore’s Law from an idea into a manufacturable reality.

III. The Survival Years: Post-Founder Evolution (1985-1995)

The mid-1980s were brutal for American semiconductor equipment companies. Japanese toolmakers, buoyed by coordinated industrial policy and exceptional manufacturing execution, were taking share fast. U.S. players were shutting down, merging, or quietly backing away from the hardest fights.

And right as that storm hit, Lam Research lost its founder.

With David Lam out of the CEO seat, the company had to prove a scary thing: that it wasn’t just a brilliant engineer’s insight wrapped in a young startup’s momentum. It had to become a durable organization—one that could keep winning on technology, execution, and customer trust without relying on a single person to hold it together.

The team that stepped in made a defining choice. Instead of broadening into adjacent categories to chase near-term revenue, they narrowed the focus. They would double down on etch and try to build a lead so large competitors couldn’t erase it. In an era when “full-line” breadth was the conventional wisdom, Lam chose specialization—and committed to being the best in the world at one of the most essential steps in chipmaking.

In 1987, that strategy started to show up in products. Lam launched the Rainbow etch system and its first MSSD system, and introduced the Concept One PECVD tool—plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition—that marked an early move into deposition. Rainbow pushed etch performance forward, helping customers run more wafers with tighter uniformity. And in semiconductor manufacturing, uniformity isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s yield. It’s whether a wafer becomes profit or scrap. Small improvements there can be worth a fortune.

The Japanese threat didn’t let up. Companies like Tokyo Electron and Hitachi kept pouring resources into etch and deposition, backed by a domestic semiconductor industry that was, at the time, the world’s largest. Lam’s response was not to outspend them, but to stay on the edge: pushing process capability, protecting know-how, and working shoulder-to-shoulder with the most advanced chipmakers to solve the next set of manufacturing problems. This way of operating—equipment engineers effectively living at customer sites, co-developing recipes and troubleshooting in real time—became a core part of Lam’s identity.

By the early 1990s, the environment began to shift. Japan’s bubble economy burst, tightening investment. The foundry model—catalyzed by TSMC’s founding in 1987—created a new kind of customer that cared less about national champions and more about whoever could deliver the best process results. And as chipmaking got more complex, etch mattered more, not less. Each new generation demanded more etch steps, which amplified the advantage of whoever had the best tools and the deepest process expertise.

Lam also started planting flags internationally—expanding into China, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan. This wasn’t just about selling boxes overseas. It was about building the service and support footprint that keeps fabs running. Once a customer standardizes on a tool set, trains engineers, qualifies processes, and builds a support relationship, switching isn’t a procurement decision. It’s a manufacturing disruption measured in lost time, lost wafers, and delayed ramps.

By the mid-1990s, Lam had done the thing most companies never manage after a founder exit: it had become the dominant player in etch. It survived the downturns, held its ground against well-capitalized Japanese rivals, and proved the company’s advantage was real.

But there was still a structural problem. Being the leader in one critical category didn’t make you immune to the industry’s mood swings. Semiconductor capital spending could whipsaw, with revenue lurching dramatically as customers went from expansion to austerity and back again. The next chapter of Lam’s evolution would be about building enough scale and enough breadth to ride those cycles—and that would increasingly mean acquisitions.

IV. The Strategic Acquisition Era (1997-2011)

By the late 1990s, Lam had proved it could win as an etch specialist. The next question was whether it could stay a category leader in an industry that was rapidly turning into an arms race of scale and scope.

In 1997, Lam made its first major acquisition, buying OnTrak Systems for two hundred twenty-five million dollars. OnTrak focused on CMP cleaning—cleaning wafers after chemical-mechanical polishing, the step that flattens each new layer so the next one can be built on top. It was an adjacent move that pulled Lam deeper into the flow of the fab without diluting the company’s identity: solve hard, high-value problems in wafer processing.

The logic was straightforward, and it was becoming more powerful every year. As chip manufacturing got more complex, fabs added more and more steps. If you could support customers across multiple steps—especially steps that touched yield and uptime—you gained leverage: more chances to be in the room early on new nodes, tighter process integration, and a stickier service relationship once your tools were qualified. Applied Materials had been running that “broad portfolio” playbook for years. Lam didn’t need to out-Applied Applied. But it did need to expand in a way that made its core strengths harder to displace.

Under CEO Jim Bagley, Lam kept pushing etch forward while adding capabilities with intent. The company continued to invest heavily in research and development, often in the range of twelve to fourteen percent of revenue—an aggressive commitment in a business where the temptation is always to cut when the cycle turns down.

In 2005, Steve Newberry became CEO and leaned further into building a more complete portfolio. Newberry brought an operator’s mindset: long-term value in this business doesn’t come from shipping a single great tool. It comes from owning more of the manufacturing path and executing reliably at global scale.

Two deals defined that push. In 2006, Lam acquired Bullen Semiconductor, now known as Silfex, which made precision silicon and silicon carbide components. This wasn’t about entering a flashy new market. It was vertical integration—securing critical parts and know-how that underpin tool performance and supply reliability. Then in 2008, Lam acquired SEZ AG, a Swiss company known for single-wafer cleaning technology, expanding Lam’s footprint in cleaning and strengthening its position around yield-critical process steps.

Look at these deals together and a pattern emerges. Lam wasn’t buying random growth. It was buying adjacency: steps next to etch and deposition, capabilities that benefited from Lam’s deep customer relationships, and technologies that fit naturally into the same conversations Lam was already having with the world’s leading fabs.

That discipline mattered because this industry punishes sloppy acquisition strategy. The semiconductor equipment graveyard is full of companies that overpaid for “synergies,” chased categories where they had no right to win, or bought technology that never integrated into a coherent product roadmap. Lam’s M&A in this era was comparatively restrained: small enough to digest, focused enough to reinforce the core, and timed to build a broader platform without losing what made the company special.

And all of it happened against the backdrop of extreme cyclicality. Semiconductor equipment demand doesn’t drift; it lurches. In a down year, revenue can fall sharply. In an up year, orders can flood in. The job is to expand capacity fast when customers are racing—and then cut decisively when spending snaps back—without starving the R&D engine that decides who wins the next node. The teams that managed Lam through those whipsaws built operational muscle that would become a competitive advantage in its own right.

By 2011, Lam was roughly a three-billion-dollar revenue company: highly profitable, exceptionally strong in etch, and with a growing presence in cleaning. It was still, at heart, a specialist—but now a specialist with the beginnings of a broader platform. In an industry accelerating toward consolidation, the question hanging over Lam was simple: is being the best at a few critical steps enough?

The answer was about to arrive as the biggest deal in the company’s history.

V. The Novellus Merger: Transformation to Scale (2011-2012)

In December 2011, Lam Research announced it would acquire Novellus Systems for $3.3 billion in an all-stock deal. In semiconductor equipment, that’s not a bolt-on. That’s a tectonic shift.

Novellus, based in San Jose, was the leading provider of chemical vapor deposition equipment—the tools that lay down ultra-thin films of material onto wafers. If etch is the controlled act of removing material, deposition is the controlled act of adding it. Those two steps are the heartbeat of modern chipmaking. And if one company could lead in both, it wouldn’t just be useful to fabs. It would be indispensable.

The mechanics of the deal were built to signal partnership, not conquest. Novellus shareholders received 1.125 shares of Lam for each Novellus share in a tax-free exchange. After the merger, Lam shareholders owned 57% of the combined company, and former Novellus shareholders owned 43%. The business kept the Lam Research name, but it wasn’t “Lam plus a product line.” Novellus would shape what Lam became.

Strategically, the fit was almost unnervingly clean. There was little overlap. Lam brought etch and single-wafer cleaning. Novellus brought thin-film deposition and surface preparation. Put them together and you could walk into a leading-edge fab and credibly cover a much larger slice of the most yield-sensitive, node-defining steps in the entire flow.

Scale mattered too. A broader portfolio made R&D dollars go further across more adjacent problems. A combined sales organization could show up with fewer handoffs, fewer gaps, and a clearer story: we can help you build this node, not just one step of it. And then there were the economics. Lam targeted $100 million in annual cost savings by the fourth quarter of 2013—real money, in a business where margins are hard-earned and cycles are unforgiving.

But the merger didn’t just bring technology. It brought people who would define the next era. Tim Archer—Novellus’s chief operating officer for the prior eighteen years—became COO of the combined company. Archer was a Caltech-trained applied physicist who began his career at Tektronix designing bipolar integrated circuits. He arrived with deep process credibility and an operator’s instinct for execution. Years later, in December 2018, he would succeed Martin Anstice as CEO. But his fingerprints were on the post-merger company from day one.

Anstice, who had been Lam’s CFO, became CEO in 2012 after the deal closed in June. His first assignment wasn’t just integration in the org-chart sense. It was integration of identity. Lam and Novellus had competed for decades. Their engineering cultures were different, their teams were proud, and pride doesn’t dissolve just because the legal paperwork cleared. Anstice’s approach was to keep the organization oriented outward—on measurable performance and customer outcomes—rather than letting internal politics decide whose way of doing things would win.

The payoff came quickly. Customers increasingly preferred suppliers that could deliver more of the process flow with fewer seams. The cost savings came in stronger than expected. And, most importantly, Lam gained a new kind of technical leverage: when the same company understands both how films get deposited and how they get etched back, it can optimize sequences—entire stacks, not isolated steps—in ways a single-discipline vendor simply can’t.

This was the moment Lam stopped being “the etch company” and became a full-spectrum process equipment powerhouse. It was the defining strategic decision of the company’s history—and it set up the next decade of growth. But as Lam was about to learn, not every big swing lands. The next attempted deal would end very differently.

VI. The Failed KLA-Tencor Deal & Strategic Pivot (2015-2016)

In October 2015, Lam Research announced an agreement to acquire KLA-Tencor for about $10.6 billion. If Novellus had turned Lam into a new kind of company, this would have turned it into a new kind of industry.

KLA-Tencor was the clear leader in inspection and metrology—the tools that don’t add material or remove it, but verify it. They scan wafers for defects, measure critical dimensions, and tell the fab whether the last step actually worked. Put Lam’s process tools together with KLA’s ability to see and measure what’s happening, and you’d have a single company that could both shape the wafer and validate it, step after step.

The vision was obvious and powerful. As chips got more complex, the tight loop between “do” and “measure” became the difference between a fast ramp and a painful one. In theory, a combined Lam-KLA could help customers catch defects earlier, tune processes faster, and optimize the whole flow with much better feedback—years before “smart manufacturing” became a buzzword.

But the same logic that made the deal attractive also made it alarming to regulators. The U.S. Department of Justice focused on KLA-Tencor’s dominance in inspection and metrology and the risk that, inside a combined company, those tools could become leverage against competitors. Lam’s rivals in etch and deposition would be forced to rely on equipment and services controlled by a direct competitor—an inherent conflict the DOJ viewed as dangerous. Months of negotiations and proposed remedies didn’t change the outcome. The DOJ ultimately wouldn’t keep engaging.

On October 5, 2016, Lam and KLA-Tencor mutually agreed to terminate the merger. No termination fees changed hands—an unusually clean break for a deal of that size—but it was still a hard stop on a very big ambition.

And in hindsight, it was also clarifying. With blockbuster consolidation effectively off the table, Lam redirected its energy to what it could control: organic growth and deeper R&D. The company leaned harder into etch and deposition just as the industry was moving into three-dimensional architectures—3D NAND, FinFETs, and increasingly advanced packaging—that demanded more steps, more precision, and more of exactly what Lam specialized in.

Sometimes the most important deal is the one that never closes. The KLA-Tencor episode made the constraint unmistakable: in semiconductor equipment, regulatory scrutiny is real, and it’s binding. Lam’s next phase would be built less on buying its way into new categories—and more on winning the ones it was already in.

VII. Modern Era: AI Boom & Geopolitical Navigation (2016-Present)

When Tim Archer took the CEO job in December 2018, Lam was already a leader. Over the next few years, it started to feel less like Lam was competing in the industry—and more like the industry was reorganizing around the steps Lam owned.

Archer was a product of both sides of the Lam-Novellus marriage. He’d spent eighteen years at Novellus before the merger, then another six as COO of the combined company. That gave him a rare, full-stack view of the business: deposition and etch, tools and process, engineering reality and customer economics. He was trained in applied physics at Caltech, and he could go deep with customers on the underlying technical problems. He’d also done a Harvard management program, but people who worked with him tended to emphasize something else: he was methodical, technically rigorous, and obsessed with execution, not theatrics.

The defining shift of Archer’s era wasn’t a single product cycle. It was a structural change in how chips got built. For decades, semiconductor progress meant making features smaller on a basically flat surface. But as traditional scaling ran into physics and economics, the industry started building upward. NAND memory became a vertical stack—3D NAND—like turning a suburban neighborhood into a skyline. Logic moved into true 3D devices: first FinFETs, then gate-all-around structures. And packaging stopped being an afterthought and became its own frontier, stacking multiple chips together and threading them with dense vertical interconnects.

That transition was rocket fuel for Lam. The move to 3D doesn’t just make chips harder; it makes them longer to manufacture. Every extra layer and every higher aspect ratio translates into more deposition steps, more etch steps, more cleans, more chances for defects, and more demand for the tools that can keep profiles straight and yields high. In other words: even if fabs weren’t processing more wafers, each wafer suddenly required more of what Lam sells.

That tailwind came with a cyclical catch: Lam’s revenue has long been tied heavily to memory. Historically, about two-thirds of the business came from memory makers, with particularly deep exposure to NAND flash. In upcycles—when memory companies spend aggressively—Lam tends to overperform. In downcycles—when memory spending freezes—Lam feels it harder than more diversified peers. It’s a concentrated bet, and it cuts both ways.

To keep up with demand, Lam also had to build real-world capacity, not just ship PowerPoints. It opened a manufacturing facility in Malaysia in 2021 and launched an R&D center in Bengaluru, India in 2022. Over roughly four years, the company nearly doubled its overall manufacturing capacity—an expensive, conviction-filled move that assumed the long-term demand curve for equipment was shifting up. By 2025, Lam’s installed base passed one hundred thousand chambers worldwide. That number isn’t just bragging rights; it’s a growing annuity of service, parts, upgrades, and deep customer lock-in.

Then came the AI acceleration in 2023 and 2024. Training frontier models and running inference at scale requires huge volumes of advanced logic and, crucially, high-bandwidth memory. That kicked off a race: cloud giants and chipmakers sprinting to expand capacity and move to more advanced nodes. Lam wasn’t adjacent to that wave—it was in the middle of it. If you want more layers, tighter profiles, and better yields, you need more deposition and etch. And if you need more deposition and etch, you’re talking to Lam.

And then there’s China—the hardest strategic problem on Lam’s board. In fiscal 2025, China represented about thirty-seven percent of Lam’s total sales, making it the company’s largest geographic market. Chinese chipmakers, pushed by national policy toward self-sufficiency, were investing aggressively in equipment. At the same time, U.S. export controls—tightened repeatedly since 2022—kept narrowing what Lam could sell, and to whom.

The effects were not subtle. The fifty-percent affiliate rule limited shipments to certain domestic Chinese customers. Lam estimated about a two-hundred-million-dollar revenue drag in its December 2025 quarter alone, and projected roughly a six-hundred-million-dollar headwind for calendar year 2026. The company also expected China to fall below thirty percent of total sales in 2026 as restrictions took hold. For a company that benefited enormously from China’s buildout, that’s not a rounding error. It’s a reshaping.

Even with those constraints, Lam’s scale in late 2025 was enormous. In the December 2025 quarter, it generated about $5.34 billion in revenue with gross margins just under fifty percent. Annual R&D spend had moved above two billion dollars—around twelve percent of revenue—because in this business, you don’t defend leadership with marketing. You defend it with process capability. Headcount was roughly eighteen thousand globally. And by January 2026, Lam’s market cap—supported by a share price that hit an all-time high above $220—reflected a market conclusion that’s easy to summarize: Lam sits where the AI buildout meets the physical reality of manufacturing.

The technology roadmap backed that up. Lam’s cryogenic etch work, which won a 2025 SEMI Award, points to where the hardest problems are going. By etching at extremely low temperatures, Lam can deliver faster etch rates and more vertical profiles—exactly what you need as 3D NAND heads toward stacks of three hundred layers or more. The company also highlighted momentum in its conductor etch systems: the Aqara platform doubled its installed base year over year and won tool-of-record positions tied to EUV and high-aspect-ratio applications.

So the modern Lam story is a balance of forces. On one side: AI-driven demand, 3D structures, and a manufacturing flow that’s becoming more etch-and-deposition intensive every year. On the other: real geopolitical limits, especially in China, and rivals investing aggressively to close gaps. Lam’s share of wafer fabrication equipment spending has pushed into the mid-thirties percent range, meaning it’s taking more of a growing pie. The open question is whether it can keep doing that as export controls tighten and the next wave of technology complexity arrives.

VIII. Technology Deep Dive: The Physics of Making Chips

To really understand why Lam Research matters, you have to picture what a fab actually does. Not “chips are important” in the abstract, but the literal reality: engineers rearranging matter at the scale of atoms, over and over again, across a twelve-inch silicon wafer.

A modern chip takes hundreds of process steps. But the heart of the whole operation—where devices are built, shaped, and rescued from the chaos of physics—comes down to two families of steps that Lam lives and dies by: deposition and etch.

Deposition is exactly what it sounds like: laying down thin films of material on top of the wafer. But “thin” here means a few atoms thick, and “uniform” means uniform everywhere, across the entire wafer. If the film is a tiny bit too thick on one edge, or a tiny bit too thin in the center, the chip might not work. Lam’s portfolio spans multiple ways to do this: electrochemical deposition for copper interconnects, chemical vapor deposition where gases react on the wafer and form a solid film, and atomic layer deposition, the extreme end of precision, where the tool builds the film one atomic layer at a time.

Etch is deposition’s mirror image: removing material, selectively, to sculpt patterns. The wafer gets coated with photoresist, then exposed and developed into a microscopic stencil. Lam’s etch tools then generate plasma—an electrically energized gas—and use it to strip away what’s exposed while leaving the protected regions behind. The tolerance window is unforgiving. The most advanced chips have features measured in single-digit nanometers, on the order of a few dozen atoms. And you’re not etching one feature. You’re etching billions of them, and they all have to come out right.

Then there are the steps that sound mundane until you realize they’re existential. Lam also sells photoresist strip, which removes the stencil after etching, and wafer cleaning, which scrubs away residue and contamination between steps. In a fab, “dirty” doesn’t mean you can see it. It means a single stray particle at the nanometer scale can kill a transistor—and when that transistor sits inside a chip worth hundreds or thousands of dollars, yield becomes the whole game.

Lam’s market share in etch is the cleanest proof of how hard this is, and how good Lam has gotten at it. The company holds roughly forty-five percent of the global etch equipment market. In advanced-node etching below five nanometers, its share rises above eighty percent. And in 3D NAND channel etching—the brutal job of drilling ultra-high-aspect-ratio holes through stacks of alternating layers—Lam has historically been close to one hundred percent share. That kind of dominance doesn’t come from a single breakthrough tool. It comes from years of process learning, co-developed with customers, baked into hardware, software, and recipes that competitors can’t copy quickly even if they understand what they’re looking at.

That brings us to a feature of this industry outsiders often miss: customer concentration isn’t a bug, it’s the structure. The leading-edge world largely runs through a handful of companies—TSMC, Samsung, Intel, and Micron. Lam’s relationships with them span decades and go far beyond sales. They involve engineers embedded with customers, joint development programs, and deeply intertwined process roadmaps. Once a fab qualifies a Lam tool for a critical step, switching is not like changing vendors on an office contract. It means months of requalification and the very real risk of yield loss that can cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

Lam’s competitive universe is basically an oligopoly. Applied Materials is the biggest by revenue and the broadest by product line, leading in deposition overall. Tokyo Electron is the heavyweight Japanese competitor, strong in coater/developer systems and increasingly aggressive in etch. And ASML sits adjacent but essential: it builds the lithography machines that print the patterns onto wafers before Lam’s tools carve and build them.

The fight is getting sharper. Tokyo Electron has publicly targeted Lam’s dominance in 3D NAND channel etch, a segment Tokyo Electron believes could grow from about five hundred million dollars in 2023 to about two billion dollars by 2027. TEL has also laid out massive investment plans—about one point five trillion yen in R&D and about seven hundred billion yen in capex for fiscal 2025 through 2029—dramatically increasing spending. This is the reality of semiconductor equipment: if you’re winning, the best-funded competitors in the world are coming directly at the step you’re famous for.

And the physics only gets worse from here. As features push toward angstrom-scale dimensions—tenths of a nanometer—the margin for error approaches fundamental limits. This is not a market where a clever startup shows up with a slick UI and “disrupts” the incumbents. The barriers to entry are measured in billions of dollars of R&D, decades of process knowledge, and trust earned through years of shipping tools that actually work in production. It is, almost by definition, an oligopoly.

And within that oligopoly, Lam sits in one of the most powerful places you can sit: right at the steps where chips get built—and where they most often fail.

IX. Business Model & Financial Architecture

Lam Research runs on two engines, and the whole company makes more sense once you see how they work together.

The first is equipment sales: shipping brand-new etch, deposition, and cleaning tools to chipmakers that are building fabs or pushing to the next process node. This is the headline business, and it’s inherently lumpy. When TSMC or Samsung greenlights a major expansion, Lam’s orders surge. When the cycle turns and budgets freeze, equipment revenue can fall fast. That’s not a flaw in Lam’s execution—it’s the nature of selling multi-million-dollar tools into an industry that alternates between sprinting and bracing for impact.

The second engine is Lam’s Customer Support Business Group, or CSBG. This is the parts, service, upgrades, and refurbished equipment business that rides on top of Lam’s installed base of more than one hundred thousand chambers. Unlike new tool sales, support doesn’t stop just because capital spending slows. Fabs still have to run, and tools still need maintenance. As the installed base grows, CSBG becomes a compounding machine—and Lam says revenue per chamber has been rising even faster than the chamber count, because the tools are getting more complex and the support required to keep them productive is becoming more valuable.

By the December 2025 quarter, that two-engine model was producing a financial profile that’s rare even in great industrial tech companies. Lam delivered $5.34 billion in revenue, up twenty-two percent year over year. Gross margins were about 49.7%, reflecting the pricing power that comes from owning mission-critical steps in the flow. Operating margins above 34% showed how efficiently Lam could turn that revenue into profit. And the company was guiding to roughly $5.7 billion in revenue for the March 2026 quarter—momentum continuing, not fading.

A big reason Lam can defend that performance is its willingness to keep spending through the cycle. R&D runs at roughly twelve percent of revenue—about two billion dollars a year. In semiconductor equipment, that’s not discretionary. It’s the moat. The companies that build the winning tools for the next node get the orders, and the ones that hesitate get designed out.

Capital allocation is steady and pragmatic. Lam returns cash through dividends and buybacks, but it also keeps enough flexibility to invest aggressively when the roadmap demands it. It even places smaller bets through Lam Capital, its venture arm, with twenty-eight investments across nineteen portfolio companies spanning semiconductor subsystems, AI chips, and Industry 4.0. Notable examples include Multibeam (e-beam lithography), LIDROTEC (laser-based chip dispensing), and Corvic AI (cognitive infrastructure). Think of it as both an investment portfolio and an early-warning system for technologies that could matter to Lam later.

Then there’s the part of the model that’s less about engineering and more about the map. China was thirty-seven percent of fiscal 2025 revenue, and Lam expected that to drop below thirty percent in 2026 as export controls tightened. That’s a real headwind. The counterweight is the surge of investment elsewhere—especially in the U.S., Taiwan, and South Korea—supported by government subsidies like the CHIPS Act and by the AI-driven capacity buildout. The strategic question isn’t whether Lam can grow outside China. It’s whether that growth can more than offset what geopolitics takes away. Management’s guidance implies yes, but it’s not a wide-open lane.

Zoom out another step and you see why investors fixate on share. The wafer fab equipment market was about $110 billion in 2025 and was expected to grow to roughly $135 billion in 2026, with more of that growth landing in the second half. With Lam’s share now in the mid-thirties percent range, it has a simple advantage: if the market grows, Lam can grow faster.

And there’s one more tailwind forming underneath all of this: advanced packaging. Lam’s tools are becoming increasingly important for processes like through-silicon vias and hybrid bonding, and advanced packaging was expected to grow more than forty percent in 2026. In other words, even as traditional scaling gets harder, the industry is finding new ways to add performance—and those ways still require the same core skill Lam has been compounding for decades: precision deposition, precision etch, and keeping yield intact when the physics wants it to fall apart.

X. Playbook: Strategic & Investing Lessons

Lam Research’s forty-five-year run reads like a masterclass in how to win in a brutal, physics-driven industry without losing the plot.

First: technical specialization can be a superpower. David Lam didn’t try to build every kind of semiconductor tool. He picked plasma etching, bet the company on it, and kept investing until “better” became “obviously better” in production. That focus let a relatively small company take on much larger rivals. Even when Lam broadened—most dramatically with Novellus—it stayed true to the same thesis: own the most critical process steps, the ones that define yield and enable the next node, and be best-in-class there. In industries where the hard part is the science, depth tends to beat breadth.

Second: M&A works best when it’s about capability, not just scale. Lam’s deal history is remarkably consistent: buy adjacent technologies that your existing customers already need, and that you can integrate without breaking what made the acquired team great. OnTrak, SEZ, and Novellus all fit that pattern. And the failed KLA-Tencor deal shows the outer boundary. The strategy may have made sense on paper, but if the combination creates enough market power to trigger regulators, it stops being a business question and becomes a political one. Any company that grows through acquisitions has to know the difference between building a stronger platform and building something that can’t be approved.

Third: cyclicality doesn’t forgive. Semiconductor equipment demand doesn’t trend smoothly; it snaps between feast and famine. Lam built the operational muscle to survive that reality: run lean in downturns, ramp quickly when customers spend again, and—most importantly—keep R&D funded even when the cycle tempts you to cut. The growing CSBG service business helps soften the swings, but it doesn’t erase them. The takeaway for investors is simple: a bad year often reflects the cycle, not the quality of the business—and a great year isn’t automatically a new permanent baseline.

Fourth: in B2B, the deepest moat is customer intimacy. Lam’s relationships with TSMC, Samsung, Intel, and Micron aren’t just purchase orders. They’re technical partnerships built on co-development, engineers embedded with customers, and process knowledge accumulated over years. That creates switching costs that don’t show up cleanly on a spreadsheet: they’re measured in requalification time, engineering disruption, and yield risk. In any market where the product is woven into the customer’s operations, this kind of trust and integration is hard to copy and even harder to displace.

Finally: geopolitics is now part of the business model. China was a major growth engine for Lam—until export controls turned it into a constraint. The point isn’t that companies should avoid contested markets. It’s that they need geographic diversification and serious scenario planning for regulatory disruption. Lam’s investments in Malaysia, India, and expanded U.S. capacity reflect that shift from growth-at-all-costs to resilience-by-design.

The “picks and shovels” line is overused, but here it actually fits. In a gold rush, the most consistent fortunes often went to the people selling the tools. In the AI buildout, the durable winners may be the companies building the equipment that makes the chips that power everything else. Lam is one of the clearest examples of that dynamic in the modern world.

XI. Bear vs. Bull Case Analysis

The Bull Case

The secular bull case for Lam is built on a few trends that all point in the same direction.

First, the AI-driven chip buildout still looks early. Training and running large language models takes enormous amounts of compute and memory, which in turn drives demand for the most advanced chips. And the more demanding the workloads get, the more silicon the world has to manufacture. More silicon means more process steps. More process steps means more Lam.

Second, the industry’s shift to three-dimensional structures is structurally good for Lam. Whether it’s adding more layers in 3D NAND, moving logic to gate-all-around transistors, or pushing advanced packaging interconnects, the pattern is consistent: 3D requires more deposition and more etch. Lam’s addressable market doesn’t just rise with wafer volumes; it expands with complexity.

Third, Lam’s moat may be getting deeper, not shallower. The company’s position in etch—above forty-five percent share, with outsized strength in advanced-node and high-aspect-ratio applications—reflects years of accumulated process knowledge that’s hard to copy quickly, even for well-funded rivals. The company’s cryogenic etch work and its Aqara conductor etch systems show it’s still investing at the frontier, not just defending yesterday’s share.

Fourth, the service engine keeps getting more important. With more than one hundred thousand installed chambers and increasing revenue per chamber, Lam’s Customer Support Business Group adds a growing stream of recurring revenue. It won’t eliminate cyclicality, but it can blunt the worst of it and makes Lam less dependent on the timing of new fab buildouts.

If you look at Lam through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers lens, the strengths line up. There’s process power in the co-developed recipes and embedded know-how that make switching painful and risky. There are scale economies in R&D, where roughly two billion dollars a year can be leveraged across a broad base of adjacent challenges. And there’s a cornered resource quality to decades of etch expertise that can’t simply be hired away or reverse-engineered on a schedule.

Porter’s Five Forces also lands in Lam’s favor. New entrants are effectively locked out by the capital, time, and trust required. Substitutes don’t really exist—chipmaking doesn’t get to skip etch and deposition. Buyers are huge, but their power is constrained by qualification risk and switching costs. Rivalry is intense, but it plays out inside a stable oligopoly where the game is technology and execution more than price wars.

The Bear Case

The sharpest near-term risk is China. With about thirty-seven percent of fiscal 2025 revenue coming from China and export controls tightening, Lam is exposed to regulation it can’t negotiate away. The company’s estimated six-hundred-million-dollar headwind for 2026 could grow if restrictions expand further. And longer-term, China’s push to build domestic alternatives creates a second risk: even if those tools trail Lam technologically today, sustained investment could slowly chip away at share inside a market that used to be a major growth engine.

Cyclicality is the other ever-present bear case. If AI-driven demand cools, or if a recession forces customers to pull back on capital spending, Lam’s system revenue can drop quickly. That risk is magnified by mix: roughly two-thirds of Lam’s revenue has historically come from memory, which is the most boom-and-bust segment of semiconductors. A downturn like the memory spending collapse seen in 2019 would hit Lam harder than more diversified peers.

Competition is also getting louder and better funded. Tokyo Electron has openly targeted Lam’s stronghold in 3D NAND channel etch and is backing that ambition with a major step-up in investment spending. Applied Materials, with its broader portfolio, keeps pressing everywhere. If a competitor lands a real breakthrough in etch or deposition, Lam’s share advantage could compress.

Finally, there’s technology transition risk. New materials, new device architectures, and lithography shifts like high-NA EUV can reorder the playing field in ways that are hard to forecast. In this industry, leadership is earned node by node—and it can be lost the same way.

Key KPIs to Watch

Two indicators tell you a lot about whether the Lam story is compounding or cracking.

The first is Lam’s share of wafer fab equipment spending, now in the mid-thirties percent range. It’s the cleanest single read on whether Lam is winning the steps that matter and whether 3D complexity is expanding its slice of the pie.

The second is CSBG growth relative to the installed base. The question isn’t just “are there more chambers out there?” It’s “is Lam extracting more service, parts, and upgrade revenue per chamber over time?” If that keeps rising, Lam’s stability and earnings power improve even when the equipment cycle turns.

XII. Epilogue: What Comes Next

The semiconductor equipment business has quietly consolidated into one of the tightest oligopolies in global technology. A small handful of companies—ASML, Applied Materials, Lam Research, Tokyo Electron, and KLA—now control most of the market. Each owns a critical set of steps. Each depends on the others’ success. And together, they form the supply chain behind virtually every meaningful advance in computing.

Lam sits in a particularly powerful seat inside that structure. It makes the tools that add and remove material—the deposition and etch steps that literally build the chip. And in the AI era, that position isn’t just “well positioned,” it’s structural. You don’t train or run large models without vast amounts of advanced logic and high-bandwidth memory. And you don’t manufacture high-bandwidth memory, or the dense interconnects around it, without world-class etch and deposition. This isn’t a cyclical story pretending to be secular. The physics of making chips keeps pushing the industry toward more layers, more steps, higher aspect ratios, and tighter tolerances—which, almost by definition, means more of what Lam sells.

So what comes next? The playbook is visible. As China becomes a smaller share of revenue under export controls, Lam can keep widening its footprint elsewhere—more manufacturing, more service capacity, more local support close to the fabs that are expanding in the U.S., Taiwan, Korea, and beyond. It can press harder into advanced packaging, where growth has been running far faster than the broader market, and where the same precision processes—etch, deposition, clean—keep showing up in new forms. And with an installed base of roughly one hundred thousand chambers, Lam has something else competitors envy: an enormous stream of real-world process data. If the line between equipment and software continues to blur, the company that already lives inside the fab, and already understands the recipes, is the natural candidate to monetize optimization and productivity at scale.

Step back and you can see how clean the arc is. David Lam’s original bet—that plasma etching would become a foundational enabling technology for semiconductor manufacturing—turned out to be not just right, but more right with every generation. What began in 1980 as a focused, almost contrarian startup is now a company worth roughly a quarter-trillion dollars, embedded in the manufacturing stack of the modern economy. The tools have changed. The scale has exploded. The geopolitical stakes are now board-level realities. But the proposition hasn’t moved: build the best tools for the hardest steps, and the world’s most important factories will come to you.

XIII. Recent News

Lam Research capped off 2025 with a record quarter, reporting results for the period ended December 28, 2025. Revenue came in at $5.34 billion, up 22% year over year and ahead of what analysts were expecting. Earnings per share were $1.27, about a dime above consensus. Management also guided to about $5.7 billion in revenue for the March 2026 quarter, signaling that demand wasn’t rolling over.

Investors responded accordingly. On January 16, 2026, Lam’s stock notched an all-time high close of $222.96. By late January, the company’s market cap had pushed past $270 billion—an unmistakable vote of confidence that Lam is sitting in the direct path of AI-driven spending.

On the technology front, Lam picked up the 2025 SEMI Award for North America in October 2025 for its cryogenic etch work—specifically the third-generation Cryo 3.0 system—highlighting how central high-aspect-ratio etch has become as 3D NAND stacks keep rising. The Aqara conductor etch platform also continued to gain momentum, doubling its installed base year over year and landing production tool-of-record wins tied to EUV and other high-aspect-ratio applications.

Operationally, Lam kept building for scale. In November 2025, it announced deeper investment in the Silicon Forest—Oregon’s semiconductor manufacturing corridor—expanding capacity to meet demand. And through Lam Capital, the company continued placing bets across the semiconductor ecosystem, including investments during 2025 in Multibeam, LIDROTEC, and Corvic AI.

The biggest cloud remains geopolitics. Export controls are still the primary overhang, and management has said it expects China revenue to fall below 30% of total sales in calendar 2026. The company has also pointed to an estimated $600 million revenue headwind from these restrictions. The response is straightforward: keep diversifying toward markets where AI-driven fab investment is accelerating outside China.

Wall Street, for now, has stayed largely on Lam’s side. RBC Capital initiated coverage with an Outperform rating, and multiple firms have argued that Lam can keep outgrowing the broader wafer fab equipment market through 2026 and beyond—because the industry’s structural trend is still more deposition, more etch, and more of the steps Lam leads.

XIV. Links & Resources

- Lam Research investor relations (annual reports, SEC filings): investor.lamresearch.com

- SEMI industry reports on the semiconductor equipment market

- Chip War by Chris Miller: useful context on the geopolitics shaping who can build what, and where

- Lam Research newsroom: newsroom.lamresearch.com

- David K. Lam oral history: in the SEMI oral history collection

- Lam Capital portfolio: lamcapital.com

- ASML, Applied Materials, Tokyo Electron, and KLA investor presentations (great for competitive context)

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music