Louisiana-Pacific Corp: From Antitrust Spin-Off to Building Products Innovation

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a boardroom in Nashville, Tennessee, sometime in the early 2000s. Louisiana-Pacific’s executives are staring at a stack of legal documents that might as well be a death sentence: billions in potential liabilities.

Their flagship siding product, Inner-Seal, is failing in the real world. Homes across America are seeing rot and damage. Class action attorneys are closing in. Investigators are asking uncomfortable questions. The stock has collapsed.

This is the point where most companies don’t come back.

Louisiana-Pacific did.

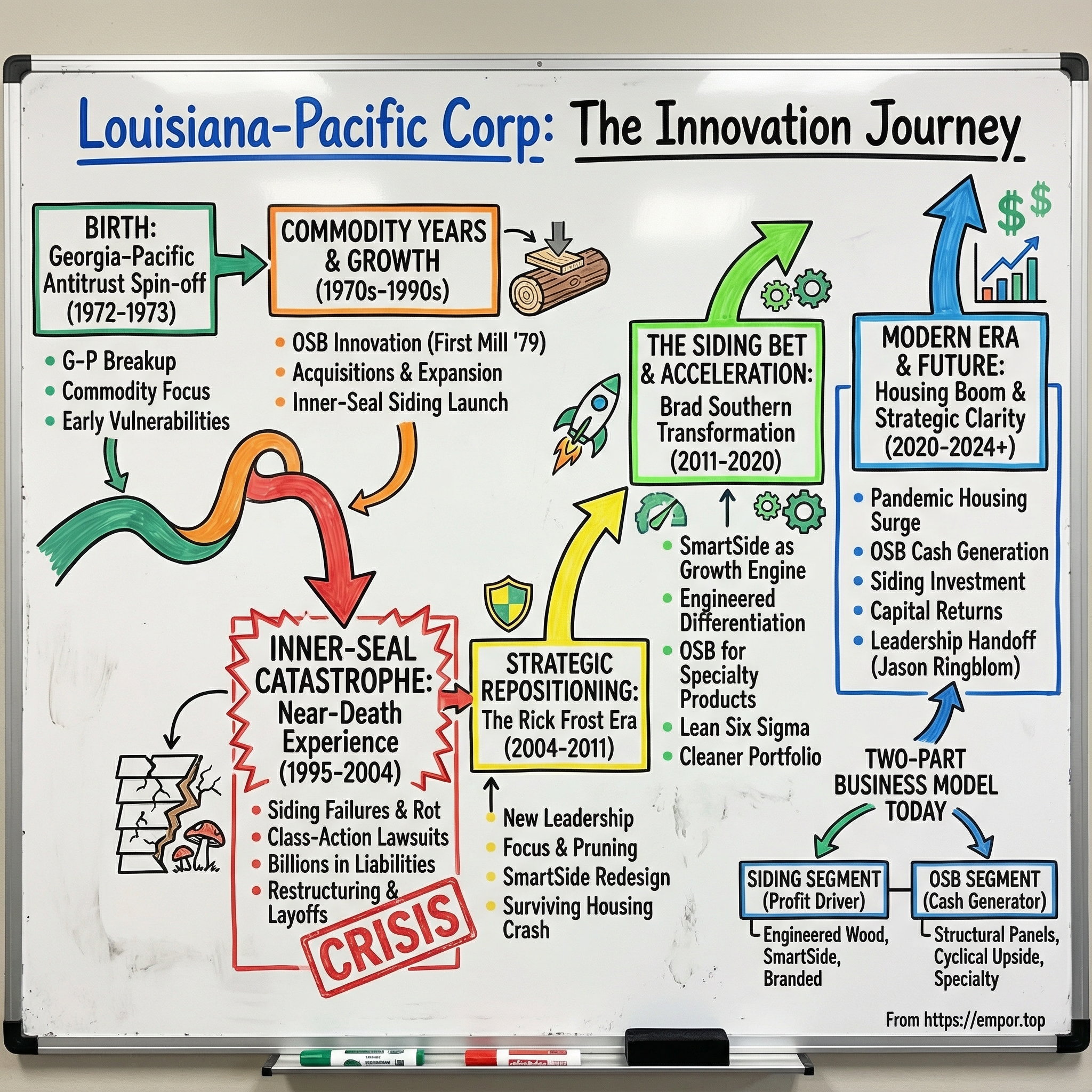

Born out of an antitrust breakup, nearly taken down by defective products, and repeatedly tested by brutal housing cycles, LP turned itself into one of the most unlikely reinventions in American building materials.

By 2024, Louisiana-Pacific reported $2.94 billion in revenue, up nearly 14% year over year. Earnings jumped to $420 million, up more than 135%. Along the way, LP became the largest manufacturer of engineered wood siding in North America and the second-largest producer of oriented strand board on the continent.

At its core, the LPX story is about survival, reinvention, and focus. Incorporated in 1972 and now headquartered in Nashville, the company has spent five decades riding the booms and busts of housing—while also enduring something far worse than a downturn: a product disaster. Inner-Seal, produced from 1985 to 1995, triggered a 1996 class-action lawsuit that’s been described as “the largest class-action lawsuit in the history of the siding industry.”

What makes this story so compelling isn’t just that LP survived. It’s what it became on the other side. Louisiana-Pacific moved from being a commodity wood products company to a differentiated building solutions business, with siding now driving the majority of its EBITDA. It rebuilt trust after one of the most notorious product failures in American housing. And it learned—sometimes the hard way—how to stay disciplined when the cycle turns and weaker competitors panic.

For investors, operators, and anyone who likes a good comeback story, LP raises a few big questions: How do you rebuild a brand after catastrophic failure? What does strategic focus actually look like when your back is against the wall? And can a company rooted in commodities really escape its fate through innovation?

Let’s dive in.

II. The Birth: Georgia-Pacific's Antitrust Breakup (1972–1973)

In the early 1970s, American antitrust enforcement was having a moment. Regulators were looking hard at big, vertically integrated industrial companies—especially the ones that seemed to be swallowing whole markets.

Georgia-Pacific was one of those giants. It had been buying up smaller firms across the South—sixteen in all—that came with a staggering footprint of southern pine timberlands, roughly 673,000 acres that fed its plywood machine. The Federal Trade Commission argued those acquisitions were tilting the softwood plywood industry toward monopoly power.

In 1972, Georgia-Pacific agreed to a consent order. The remedy was blunt: divest about 20% of its assets—valued around $305 million—and put them into a new, standalone company. That company was Louisiana-Pacific.

The consent order didn’t just create LP; it also tied Georgia-Pacific’s hands for years. Georgia-Pacific was prohibited from acquiring other softwood plywood companies, faced restrictions on timberland purchases in the South for five years, and was limited on plywood mill acquisitions for a full decade. In other words: the government wasn’t just forcing a spin-off. It was trying to stop the flywheel that had created Georgia-Pacific’s dominance in the first place.

Louisiana-Pacific officially came into being in July 1972, built from pieces Georgia-Pacific transferred over before the separation was final. LP didn’t start life as a scrappy startup with a single mill—it inherited real operating heft: the Samoa, Ukiah, Intermountain, Weather-Seal, and Southern divisions, along with 50% interests in Alaska’s Ketchikan Pulp Company, Ketchikan Spruce Mills, and Ketchikan International Sales.

And it inherited leadership too. Georgia-Pacific vice chairman William H. Hunt became LP’s first chairman. Then, in 1974, Harry A. Merlo—LP’s chief executive since the beginning—took over as chairman while remaining CEO.

Merlo would go on to become the most consequential, and later most controversial, figure in LP’s history. His story starts far from boardrooms: the son of immigrants, raised in a logging community in Butte County, California—what he called the “Dago Town” of Stirling City. After serving in the Marines and attending Berkeley, he climbed the ranks of the timber business until he was running a Georgia-Pacific division and perfectly positioned to lead the new spinoff.

But LP’s early problem wasn’t leadership. It was the uncomfortable math of independence.

As chairman, Hunt set out to tackle three immediate vulnerabilities: LP’s reliance on outside timber supply, its heavy dependence on lumber tied to the construction cycle, and the sudden loss of Georgia-Pacific’s distribution network—the same pipeline LP had relied on to get products into the market.

And then there was the weirdest challenge of all: from day one, Louisiana-Pacific had to compete against its own former parent. Georgia-Pacific kept the larger share of the assets, the stronger brand, and much of the distribution infrastructure. LP was, in effect, a mini-me forced to fight for oxygen in markets where the giant still set the rules.

That pressure would shape LP’s personality for decades. When you can’t win on scale, you look for another way to win. And for LP, that “other way” would eventually become innovation—less a visionary choice than a survival instinct.

III. The Commodity Years: Growth Through Acquisition (1970s–1990s)

From the late 1970s through the early 1990s, Louisiana-Pacific hit the gas. With Harry Merlo firmly in charge, LP expanded through a mix of acquisitions and product bets—turning itself from an antitrust spin-off into a real contender in building products.

The logic was straightforward, and it came straight out of LP’s origin story. Compared to the industry’s biggest players, LP didn’t have the same depth of premium timber—southern pine and Douglas fir—or the same lumber position. So the company went looking for a different kind of advantage: building high-performance products from cheaper, faster-growing trees like cottonwood and aspen. Merlo later put it plainly: “We recognized that the days of making wood products from big trees were numbered for both economic and environmental reasons.”

That mindset set up LP’s biggest early breakthrough. In 1979, the company opened the first oriented strand board (OSB) mill in North America, in Hayward, Wisconsin. When production started, demand was so strong crews ran the place around the clock. Merlo told investors, “I’ve never seen a forest product accepted so quickly by the marketplace.”

OSB wasn’t magic. It was a manufacturing rethink. LP would slice logs into thin wafers, mix those wafers with resin, and press them into sheets. Instead of depending on old-growth timber, it could turn small-diameter, fast-growing trees into structural panels. First sold under the name Waferwood, OSB offered builders a compelling alternative to plywood for sheathing and subflooring: strong, consistent, and typically cheaper.

The boom years rewarded that bet. With housing strong—and remodeling and repair pulling hard on specialty products—LP’s sales rose about 50% from 1980 to 1988, while profits climbed roughly 400%. OSB went from a curiosity to a major part of the business, growing from about 6% of sales in 1980 to nearly 30% by 1990.

While OSB was changing what LP sold, acquisitions were changing what LP owned. In 1986, the company bought Kirby Forest Industries and the California properties of Timber Realization Company, adding roughly 830,000 acres of timberland—securing a deeper resource base for the future. By 1990, LP kept diversifying with purchases like Weather Guard Inc., which made home insulation from recycled newsprint, and MiTek Wood Products, a producer of laminated veneer lumber and engineered wood I-beams.

Those engineered beams were another example of LP’s “do more with less” instinct. The I-beams used about half the lumber of solid wood joists and rafters, while coming out stronger and lighter—exactly the kind of performance story builders like, especially when lumber prices swing.

But LP didn’t stop at structural products. It pushed its reconstituted-wood technology into entirely new categories. The company introduced a concrete form of Inner-Seal. And in 1985, it made the decision that would define the next chapter: it started marketing Inner-Seal siding for the exterior of homes.

On paper, it looked like a classic, smart extension—taking a successful engineered panel technology and moving “up the stack” into a higher-value application. In reality, it was the kind of move that either locks in a company’s future… or detonates it. For Louisiana-Pacific, it would do both.

By the early 1990s, LP looked like a success story. It controlled more than 950,000 acres of timberland, ran plants in 29 states plus operations in Canada and Ireland, and had earned a reputation as a leader in engineered wood. Even Georgia-Pacific—the company that once towered over its spinoff—was losing ground as OSB and waferboard gained share across the industry.

But in building products, the stakes are different. These aren’t disposable goods. They sit on people’s homes, their biggest asset. And when a company starts to believe its own momentum is a substitute for caution, the downside isn’t a bad quarter.

It’s existential.

IV. The Inner-Seal Catastrophe: A Near-Death Experience (1995–2004)

The morning a homeowner discovers mushrooms growing out of their siding is the kind of thing you don’t forget.

In the early 1990s, that surreal scene started playing out in neighborhoods across America. Louisiana-Pacific’s Inner-Seal lap siding—marketed as a smart, affordable innovation and sold with a 25-year warranty—was failing in plain sight. Boards swelled. Paint blistered. Edges crumbled. Mold and fungus showed up where no one ever wants to see it: on the outside walls of their home.

LP manufactured Inner-Seal siding from 1985 to 1995. In 1996, homeowners filed a class-action lawsuit alleging manufacturing problems and systemic defects. It wasn’t just “bad press.” It became what’s been described as the largest class-action lawsuit in the history of the siding industry. The complaints were consistent and grim: cracking, swelling, discoloration, and premature rot that damaged homes and dragged down property values.

At the heart of it was moisture. Inner-Seal was a composite wood product made by pressing layers together and bonding them with glue. Unlike traditional wood siding, it wasn’t a single piece of lumber; it was built up from stacked, pressed sheets. When the product’s sealing and moisture-management didn’t hold up over time, water got in—and once it did, the material deteriorated.

Early warning signs had surfaced in a different place. Some of the first claims involved LP’s OSB roof panels in Florida. After Hurricane Andrew in 1992, shingles tore off homes and exposed the panels to heavy rain. Those claims were serious, but the siding failures were on another level: broader, more predictable, and more devastating because they sat on the front of the house, taking weather every day.

The legal and financial fallout came fast. By the end of 1991, LP had already paid more than $22 million to settle OSB claims, followed by another $14 million between 1993 and 1994. Then came the main event. In 1996, LP committed at least $275 million to a settlement involving roughly 800,000 homeowners who had installed Inner-Seal siding.

That same year, U.S. District Judge Robert E. Jones approved a nationwide settlement framework that required LP to provide funding of up to $475 million to cover inspections and repair or replacement of failing siding over the next seven years.

And the homeowner settlement wasn’t the only front. Also in 1996, LP paid $65 million to settle a shareholder class-action lawsuit filed the year prior. Shareholders alleged the company had violated securities laws by failing to disclose that oriented strand board products were defective.

The claims didn’t stop quickly. By the time the case was closed in 2002, LP had paid about 130,000 warranty claims. By the end of the settlement process, the company had paid nearly $1 billion to satisfy claims.

As the company tried to bring the saga to an end, it rolled out new ways to clear the remaining backlog. In April 2003, LP announced a Claimant Offer Program designed to speed up payments: homeowners could submit an offer to settle their claim, and LP guaranteed it would accept all valid offers up to 35.87% of the approved claim amount.

In October 2003, LP said it intended to fund the remaining claims under the settlement. As of August 6, 2003, about $18 million in claims remained, and under the settlement terms those funds were to be provided in the fall of 2004, with payments soon after. Curt Stevens, LP’s Executive Vice President, said, “Providing payments to the remaining claimants will bring to a close our monetary obligations under the settlement agreement.”

Inside the company, the reckoning was just as intense. In 1995, the board met secretly in Chicago and fired Harry Merlo—the CEO who had built LP into a powerhouse and whose tenure would later be defined by this disaster. In 1996, Mark Suwyn replaced him as chairman and CEO, inheriting a business fighting for survival.

The restructuring was brutal. In late October, LP announced layoffs of 3,300 workers and the sale of $1 billion of assets—about a quarter of the company—to stay afloat. That included selling 300,000 acres of prime California timberland.

The Inner-Seal catastrophe taught a harsh, permanent lesson about innovation in building products. If an appliance fails, it’s a headache. If siding fails, it can become a structural problem. It invites water into the system and turns a home—people’s biggest asset—into a repair project.

And it shattered trust. How do you sell siding again when your last siding made people’s walls grow mushrooms?

It would take years, multiple leadership teams, and an almost obsessive commitment to doing it differently. But somehow, Louisiana-Pacific would claw its way back.

V. The Rick Frost Era: Strategic Repositioning (2004–2011)

When Rick Frost stepped in to lead Louisiana-Pacific, Inner-Seal still hung over the company like a storm cloud. Settlement obligations were still consuming cash. The brand was damaged. And the housing boom of the mid-2000s risked hiding a more dangerous truth: LP had become sprawling, complicated, and too exposed to the whims of commodity markets.

Frost’s mandate was simple to say and hard to execute: turn Louisiana-Pacific from an acquisition-built tangle of commodity businesses into a tighter, more disciplined building products company.

Richard W. Frost was named CEO to succeed Mark A. Suwyn, who retired effective October 31, 2004. Suwyn framed it as continuity in the middle of chaos: “Rick has been a key part of a strong leadership team for the past eight years.” Frost had joined LP in 1996, bringing more than 25 years of forest products experience into a company that urgently needed operational steadiness and strategic focus.

That same year, LP made a move that was symbolic and practical: it left Portland, Oregon, where it had been headquartered for its first 33 years, and relocated to Nashville, Tennessee. The message was hard to miss. This was a break with the past—literally changing the company’s center of gravity as it tried to put the Inner-Seal era behind it and move closer to key southeastern housing markets.

The reshaping didn’t happen with one big announcement. It happened through a long series of exits. From 2000 to 2010, LP completed 20 divestitures. And in May 2002, the company publicly committed to an asset sale and debt reduction program aimed at improving long-term competitiveness and financial flexibility.

By 2004, the strategy was becoming concrete. In May of that year, LP announced a plan to convert its Hayward, Wisconsin, strand board mill—historic ground as the first OSB mill in North America—into a facility that would produce SmartSide siding products. The birthplace of LP’s OSB revolution was being repurposed for what management hoped would be its redemption product in siding.

LP continued shedding non-core pieces. In 2005, it announced plans to sell its vinyl siding business to KP Building Products, including vinyl siding mills in Holly Springs, Mississippi, and Acton, Ontario, plus a warehouse in Milton, Ontario. In 2007, Fiber Composites, LLC purchased LP’s WeatherBest composite decking and railing business, including the Meridian, Idaho manufacturing facility and the WeatherBest brand.

Then, just as LP was trying to simplify and stabilize, the floor dropped out.

The 2008 financial crisis and the collapse of the U.S. housing bubble crushed demand for building products. Housing prices peaked in early 2006, began sliding through 2006 and 2007, and wouldn’t bottom until 2011. For a company still heavily tied to new home construction, it was a punishing environment.

It’s worth noting how long this pain had been building. Even back in the late 1990s, the financial scars from the Inner-Seal era were obvious: sales in 1996 were down 13% from 1995, and LP posted a $200.7 million net loss. In 1997, it lost another $101.8 million, even as executives insisted the company could fight through it. LP had survived the settlements—only to face what became the worst housing collapse since the Great Depression.

The choices LP made in the crisis years mattered. Management didn’t try to win by pushing volume through weak markets just to keep mills busy. Instead, it focused on efficiency and survival: shutting capacity, cutting costs, and protecting the balance sheet. And crucially, it kept investing in the product line that could eventually let LP compete on something other than price.

That product was LP SmartSide.

LP had launched LP SmartSide Trim & Siding in 1997, built on a manufacturing process that treated each strand of wood with a proprietary combination of zinc borate, resins, and waxes to resist moisture. The pitch was straightforward: the look of traditional wood, with the durability advantages of engineered wood.

More importantly, SmartSide was designed as the direct answer to Inner-Seal. Instead of relying on surface-level defenses, moisture protection was built into the material itself. The zinc borate treatment was the technological cornerstone—intended to protect against rot, decay, and termites by making durability part of every strand, not an afterthought.

By the time Frost’s tenure ended, LP was still very much in survival mode—but it wasn’t drifting anymore. The portfolio had been pared down. The company had fought to protect its financial position through the downturn. And SmartSide was starting to look like the path out of the commodity trap.

In the leadership handoff, LP appointed Curt Stevens to succeed Rick Frost as CEO effective May 4, 2012. Frost, who had served as CEO since 2004, retired from LP on May 31, 2012. Stevens struck an optimistic note about what had been preserved and what could now be built: “LP has exceptional people, quality products and the financial position to take full advantage of an upturn in the housing market. Great things await us.”

VI. The Brad Southern Transformation: The Siding Bet (2011–2016)

In the early 2010s, Louisiana-Pacific’s leadership faced a question that sounded simple and felt impossible: could a company that had nearly been destroyed by defective siding ever sell siding again?

Brad Southern didn’t come at that question from a distance. He’d been living with it for years. In 2004, just as the Inner-Seal settlements were winding down and SmartSide was being positioned as LP’s redemption product, Southern was appointed general manager of the siding business. If SmartSide failed, it wouldn’t just be a product miss. It would be proof that LP would never be trusted on the outside of a home again.

Southern was a forest-products lifer, but not the caricature of one. He started his career at MacMillan Bloedel as a forester and moved through forestry, strategic planning, finance, accounting, and plant management—basically every vantage point you can have inside a wood-products business. He earned both a B.S. and a master’s degree in Forest Resources from the University of Georgia. By the time he took on siding, he wasn’t just selling a product. He understood the supply chain, the mills, the economics, and the failure modes.

For more than a decade, he pushed SmartSide forward—patiently, stubbornly—until it went from “LP’s second chance” to the company’s clearest growth engine. When he became CEO, he brought something rare: an operator’s understanding of the product’s technical story, and a realist’s understanding of the psychological baggage the LP name carried in the field.

The bet hinged on a single, crucial claim: SmartSide was not Inner-Seal.

SmartSide was engineered explicitly to avoid the moisture problems that had detonated the last era. Instead of relying on surface protection, LP built durability into the material itself. Every strand of wood was treated with a proprietary mix of zinc borate, resins, and waxes designed to resist moisture, decay, and termites. The process was, in effect, a scar turned into a system: manufacturing built around lessons learned the hard way.

Southern’s style matched the strategy: focused, determined, and low on theatrics. Analysts credited him with turning LP from a commodity producer into a specialty player and repeatedly pointed to the same themes—execution, discipline, and a quieter kind of effectiveness. One called him a CEO who “gets the job done.” Another described him as a “reliable leader who operates with little fanfare.” Others emphasized the same outcome: growth in the Siding segment and a reduced risk profile for the company.

You could see that shift in the mix. Five years earlier, in the second quarter, SmartSide made up about 30% of LP’s sales. By the second quarter of the more recent period cited—even with a housing downturn—SmartSide represented 38% of sales. Not because OSB had become less important, but because siding was becoming big enough to matter.

Southern’s growth ambition was aggressive but not hand-wavy. He talked about aiming for roughly 10–12% annual growth in SmartSide siding revenue. And he understood where that growth would come from: about 40% of LP-made siding went into single-family homes, roughly 25–30% into retail buildings, and around 25% into repair-and-remodel work.

That last category mattered. New construction is cyclical. Repair and remodel can be steadier. And LP needed steadier.

SmartSide also didn’t enter an empty market. It walked into a fight with established incumbents. James Hardie dominated fiber cement, with its durability reputation—but also higher cost and more challenging installation. Vinyl owned the value end, cheap and easy to live with. Traditional wood siding sat at the premium aesthetic, with the tradeoff of ongoing maintenance.

SmartSide positioned itself right in the middle: the look people wanted, with engineered durability—and a price point between vinyl and fiber cement. But the real wedge was labor. Contractors already knew how to work with wood products. SmartSide’s installation was straightforward for crews used to wood, which became a meaningful advantage as labor shortages increasingly constrained builders.

Still, none of that mattered if the market didn’t trust the name on the bundle.

So the marketing problem wasn’t just “build awareness.” It was “rebuild belief.” Southern’s team leaned into performance proof: extended warranties to signal confidence, testing programs meant to show how SmartSide held up in the very conditions that had wrecked Inner-Seal, and case studies from early adopters to provide something the industry values more than any brochure—real-world evidence.

As SmartSide gained traction, the story analysts told about LP began to change too. “For a business that has traditionally been a commodity business, he has really tried to push it upstream,” one analyst said. Growth in SmartSide reduced the company’s dependence on OSB, a business where prices can swing violently with housing cycles and capacity changes.

That was the transformation in plain language: LP wasn’t abandoning OSB, but it was building a second engine—one with a chance at branded pricing, more stable margins, and a longer runway. If OSB was the cash cow, SmartSide was the bid for a different kind of company.

VII. Accelerating the Flywheel: The 2010s Transformation (2016–2020)

By the mid-to-late 2010s, the comeback stopped being a theory and started looking like a system. This was the third major inflection point in Louisiana-Pacific’s history: the moment the company’s strategic focus fully snapped into place, and LP finished its shift from a diversified, commodity-heavy operator into a tighter building-products business built around engineered differentiation.

The transformation accelerated through pruning. LP kept selling off the parts of the old empire that didn’t fit—timberlands and manufacturing plants tied to plywood, pulp, industrial panels, and lumber. In total, the company sold 935,000 acres of timberlands nationally, plus a long list of operations that had once made it “big,” but also made it distracted, cyclical, and capital-hungry.

That was the real math of the portfolio reset. Every sale generated cash, yes. But just as importantly, every sale removed a set of decisions LP no longer wanted to spend its time on: maintenance capex, commodity whiplash, and the constant temptation to chase volume for volume’s sake.

Some of the cleanup had started earlier. In 2003, LP continued selling timberland in Louisiana, Texas, and Idaho, along with mills tied to its divestiture program. The timberland portion of that program ultimately exceeded the company’s initial $700 million target by more than $50 million.

What emerged on the other side was a much cleaner operating model. Louisiana-Pacific, together with its subsidiaries, provided building solutions for new home construction, repair and remodeling, and outdoor structures—and organized itself around three segments: Siding, Oriented Strand Board (OSB), and LP South America (LPSA).

Siding was the crown jewel, and LP treated it that way. The segment included engineered wood siding, trim, soffit, and fascia products such as LP SmartSide trim and siding, LP SmartSide ExpertFinish trim and siding, LP BuilderSeries lap siding, and LP outdoor building solutions. This was the business that could compound: branded products, repeatable performance claims, and a sales story that wasn’t just “we’re cheaper than the other guy.”

OSB, meanwhile, evolved from “make panels and pray for pricing” into a platform for specialty products that could earn a premium. The OSB segment manufactured and distributed structural panels, including a value-added portfolio under LP Structural Solutions: LP TechShield radiant barriers, LP WeatherLogic air and water barriers, LP Legacy premium sub-floorings, LP NovaCore thermal insulated sheathing, LP FlameBlock fire-rated sheathing, and LP TopNotch 350 durable sub-flooring.

The product cadence kept moving. LP launched offerings such as LP WeatherLogic Air & Water Barrier, LP Legacy sub-flooring, and LP FlameBlock Fire-Rated Sheathing. Brad Southern underscored the strategy in plain terms: engineers weren’t just making OSB—they were designing versions that could command a premium, so “you can get paid for that” premium product.

The margin story made the shift unmistakable. In the second quarter of 2019, overall siding EBITDA margin was 19 percent—worlds apart from the single-digit economics that define much of commodity wood. That gap wasn’t an accounting trick. It was what happens when product differentiation and manufacturing execution start reinforcing each other.

Capital allocation tightened up too. This wasn’t the Merlo-era playbook of acquiring your way into growth. The priorities were organic investment in SmartSide capacity, returning capital to shareholders, and reducing debt. LP even converted an under-used OSB mill to siding production and indefinitely curtailed another—choices that signaled a new willingness to optimize the asset base instead of keeping everything running just to keep it running.

Underneath all of it was a cultural shift that matched the strategy. LP Building Products adopted Lean Six Sigma, pairing lean manufacturing’s focus on flow and waste with Six Sigma’s focus on variation and design—complementary disciplines aimed at operational excellence.

By the end of the 2010s, the arc was clear. The company that once sprawled across timber, lumber, pulp, plywood, and countless other categories had narrowed itself to what it could win at: engineered wood siding and specialty OSB. The most capital-intensive, most brutally cyclical businesses were pushed out. The businesses with a chance at durable margins—and a real identity—were kept, refined, and scaled.

VIII. The Modern Era: Housing Boom, Pandemic, and Strategic Clarity (2020–2024)

COVID-19 landed as the first real stress test of Louisiana-Pacific’s reinvented playbook. And almost immediately, it turned into something else: a once-in-a-generation housing surge that ran from the summer of 2020 into mid-2022.

For OSB, it was a frenzy. Prices hit record after record in 2020 and 2021, then briefly touched another high in 2022. The move wasn’t subtle. In a market that had historically spiked and then snapped back, OSB went from already-elevated levels to heights that were hard to believe—and stayed there longer than most cycles ever allow.

For LP, that was both a gift and a trap.

OSB margins exploded, throwing off extraordinary cash. But that cash came with a question that separates disciplined operators from cycle-chasers: do you pour fuel on the fire by adding capacity at the top, or do you treat the windfall as temporary and keep building the company you actually want to be?

LP chose the second path. By the end of 2020, it had already beaten its own cumulative target for EBITDA efficiency and economic gains, delivering $178 million of impact versus a $165 million goal. And instead of pivoting into “OSB party time,” Brad Southern leaned even harder into the strategy LP had spent the prior decade building: efficiency, focus, and continued investment in siding.

That restraint mattered because the OSB industry’s default setting has usually been the opposite. Demand rises with housing, producers rush to add supply, and the overbuild guarantees the next collapse. Over the last few years, though, capacity discipline across the industry was unusually strong—and LP’s decision not to over-invest at peak pricing ended up looking less like conservatism and more like foresight.

Then the cycle turned, as it always does. Mortgage rates climbed, housing activity slowed, and OSB prices fell through 2022. By the end of that year, profitability looked nothing like it had at the beginning.

The hangover showed up clearly in 2023. LP’s full-year net sales fell 33% year over year to about $2.58 billion. The OSB segment took the brunt of it: revenue dropped 50% on lower pricing and volume, with price down 40% and volume down 18%.

But this is where LP’s transformation paid off. The business wasn’t just “OSB with a little something on the side” anymore. Siding held up best amid the volatility elsewhere, providing a steadier earnings base while the commodity side cycled. In the model LP had spent years building, OSB could still be a powerful cash generator—but siding was the ballast.

In 2024, the company showed what that combination can look like on the rebound. Revenue rose to $2.94 billion, up nearly 14% from 2023, and earnings jumped to $420 million, up about 136%.

LP also leaned into capital returns. As the company put it, “Brad repositioned the company as a global leader in specialty building products, strengthened its financial performance, and built a culture grounded in safety, innovation, and accountability. Under his leadership, LP's share price grew fivefold and the company returned more than $4 billion to shareholders through dividends and share repurchases.”

Operationally, siding kept hitting new highs. “LP's Siding segment grew and captured share to set new records for sales volume, sales revenue, and EBITDA in the second quarter,” said LP Chairperson and CEO Brad Southern.

And the company wasn’t acting like those records were a one-off. Southern said the growth in 2024 pushed LP to accelerate planning for its next major capacity expansion: “Given the growth this year, that's resulted in us stepping up the planning for our next significant capacity expansion... we are looking at that investment next year—beginning that investment next year. And that would get us up and running either late 2026 or in 2027 depending on the timing and how the year plays out next year as far as Siding growth.”

At the same time, LP signaled a leadership handoff—another marker that the turnaround era was giving way to a new chapter. “It has been the honor of my career to lead LP's 4,300-member team,” Southern said. The company named Jason Ringblom, a 21-year LP veteran, as the next CEO. Ringblom brought deep experience across sales, marketing, and operations, and before becoming President had served as Executive Vice President and General Manager of LP’s OSB and Siding businesses prior to their integration.

IX. The Business Model & Competitive Positioning Today

Louisiana-Pacific’s reinvention only really makes sense when you look at the machine it built on the other side of Inner-Seal: a two-part business that’s designed to balance itself. One side is a branded, higher-margin growth engine. The other is a cyclical cash generator that can gush money in the right market—and still matters even when the cycle turns.

The Siding Segment is the profit driver and the identity LP fought to earn back. It’s a portfolio of engineered wood siding, trim, soffit, and fascia products, including LP SmartSide trim and siding, LP SmartSide ExpertFinish trim and siding, LP BuilderSeries lap siding, and LP outdoor building solutions.

And this is where LP’s modern competitive story lives—because it’s also where its biggest rivalry lives. The fight between LP SmartSide and James Hardie has become one of the defining matchups in building products. The competition is especially intense in major remodeling and building markets like the Twin Cities, where contractors have strong opinions, homeowners demand performance, and reputations spread fast.

LP’s edge starts with the jobsite. SmartSide is lighter than fiber cement, which makes it easier to carry, position, and install. Crews don’t need special tools, either—SmartSide can be cut with the same saws used for traditional wood. Those may sound like small details, but in construction, “easier to work with” can be a decisive advantage, especially when labor is tight.

Under the hood, LP’s technical differentiation is the zinc borate treatment. After the company’s early issues with rot and swelling in its OSB siding era, LP rebuilt the product by coating the wood flakes in zinc borate before pressing them into boards. Over time, that process became the credibility story: according to the text, LP sold more than 7 billion square feet of LP SmartSide siding over the last 17 years.

Hardie, for its part, doesn’t let LP forget the past. It has published a video showing an “OSB product” delaminating, rotting, and falling apart—an image designed to revive doubts about engineered wood siding. The product shown is tied to the old Inner-Seal era, but the point isn’t technical accuracy. It’s psychological: slow down SmartSide’s rise by reminding the market what happened the last time LP asked homeowners to trust its siding.

On cost, SmartSide has a modest advantage in the numbers cited here. The Siding Cost Guide estimates SmartSide at about $9 per square foot installed versus about $10 per square foot for James Hardie fiber cement, once materials and installation are included. Hardie’s additional weight can push costs up, both in handling and labor.

The OSB Segment is the other half of the machine: cash generation, operating leverage, and cyclical upside. It manufactures and distributes OSB structural panel products, including LP Structural Solutions—LP TechShield radiant barriers, LP WeatherLogic air and water barriers, LP Legacy premium sub-floorings, LP NovaCore thermal insulated sheathing, LP FlameBlock fire-rated sheathing, and LP TopNotch 350 durable sub-flooring.

And LP sells into a wide set of channels. Its customers include retailers, wholesalers, home building, and industrial businesses across North America, South America, Asia, Australia, and Europe.

X. Strategic Frameworks: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

To make sense of Louisiana-Pacific’s competitive position, it helps to step back from the product catalog and look at the forces acting on the business. Two lenses work particularly well here: Porter’s Five Forces for industry structure, and Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers for durable advantage.

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants (Medium-Low): Getting into engineered wood at scale is expensive and slow. Building an OSB or engineered wood siding mill takes major capital—often hundreds of millions of dollars—before you’ve sold a single sheet. Then you still need reliable timber supply, either through ownership or long-term procurement contracts. And you need distribution: relationships with large builders and big-box retailers like Home Depot and Lowe’s that take years to earn.

In siding, there’s an additional barrier that doesn’t show up on a balance sheet: trust. LP spent years rebuilding credibility after Inner-Seal. A new entrant doesn’t just have to make a product; they have to convince contractors, builders, and homeowners to believe it will still perform years from now.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Low-Medium): LP has meaningful control over key inputs. It runs forest management and timber procurement systems that are SFI certified, supported by long-term relationships and some owned timberlands. On the chemicals side, inputs like zinc borate are sourced from multiple suppliers rather than a single choke point. Energy remains a commodity exposure, but it’s an exposure the industry broadly shares and one LP can manage rather than eliminate.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Medium-High): This is one of the toughest realities in building products: many of your biggest customers are big enough to push back. Large homebuilders like D.R. Horton, Lennar, and Pulte have leverage, and big-box retailers like Home Depot and Lowe’s are powerful gatekeepers in distribution.

LP’s counter is differentiation. When a product is easier to install, lighter to handle, and delivers a look contractors and homeowners want, the conversation shifts away from pure price. The pro dealer channel helps here too: it’s more fragmented than big-box retail, and that usually translates into healthier pricing dynamics.

Threat of Substitutes (Medium-High): In siding, homeowners and builders can choose from a long list of alternatives: vinyl, fiber cement, traditional wood, metal, stucco, brick, stone. Each comes with its own trade-offs. LP’s positioning for SmartSide is “better value” across those trade-offs—more attractive than vinyl, simpler to work with than fiber cement, and less maintenance-heavy than wood.

In OSB, plywood is still the obvious substitute. But OSB has largely won structural sheathing on price and performance, and while other sheathing approaches exist, they haven’t taken meaningful share.

Competitive Rivalry (High): Rivalry is intense because this is a cyclical, capacity-driven industry. In OSB, LP competes with major producers like West Fraser (which acquired Norbord), Weyerhaeuser, and various regional players. When pricing is strong, the industry is tempted to add capacity. When that capacity shows up, pricing breaks. And in that churn, older, less efficient mills often get pushed out after newer facilities come online.

In siding, the primary rival is James Hardie. It has strong brand recognition and a reputation for performance. “Hardie Board” has become a generic term for fiber cement in the way “Kleenex” became shorthand for tissues. There are other products in the market—CertainTeed Weatherboards and Nichiha, for example—but Hardie has long benefited from being the name people remember.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies (Strong in OSB, Moderate in Siding): Scale matters most in OSB, where mill efficiency, purchasing power, and distribution leverage create real cost advantages. Louisiana-Pacific is also a major OSB producer and manufacturer of engineered wood building products. In siding, scale still helps, but it’s more about building enough volume to support distribution reach, marketing, and consistent service levels as SmartSide grows.

2. Network Effects (Minimal): LP’s products don’t get more valuable because more people use them. A homeowner doesn’t benefit from a neighbor choosing the same siding.

3. Counter-Positioning (Historical - Strong): LP’s comeback strategy after Inner-Seal is a textbook case of counter-positioning. The company leaned into the exact failure mode that once nearly destroyed it and overbuilt the fix: durability, moisture protection, and a manufacturing approach designed to prevent the rot and swelling that defined the Inner-Seal era. That gave LP a clear story to tell—and made it harder for competitors to mirror the positioning without rewriting their own narrative.

4. Switching Costs (Moderate): Switching costs aren’t huge in absolute terms, but they’re real in practice. Contractors build muscle memory around installation. Dealers build stocking habits. Architects and builders bake materials into specifications, and that creates inertia. Still, these costs don’t lock anyone in forever; builders can switch suppliers between projects if price or availability pushes them.

5. Branding (Rebuilding - Moderate to Strong): LP’s brand is better than it was, and it has been rebuilt through performance over time. But James Hardie still tends to win on pure name recognition. LP has invested in branding—like sponsorship of the Tennessee Titans stadium—yet its brand equity remains something the company continues to build rather than something it can take for granted.

6. Cornered Resource (Moderate): Timberlands and access to fiber help, but they aren’t uniquely cornered in this industry. The more distinctive resource is process and IP tied to the proprietary zinc borate treatment approach, which competitors can’t simply copy and call the same.

7. Process Power (Strong and Growing): This is LP’s most durable advantage. Decades of OSB and engineered wood manufacturing experience—driving yield, improving consistency, cutting cost, tightening quality—create a compounding knowledge base. That kind of process advantage doesn’t show up overnight, and it’s hard to replicate without walking the same long learning curve.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Considerations

Bull Case

The bullish view on Louisiana-Pacific is basically a bet that the company finally built what it always wanted to be: less hostage to commodity cycles, more powered by a branded, differentiated product line.

Structural Housing Undersupply: The U.S. has spent years building fewer homes than household formation has demanded. That mismatch doesn’t eliminate cycles, but it does create a long runway for the companies supplying the basic inputs to build and renovate homes. LP participates in both new construction and repair-and-remodel, which helps smooth the ride.

SmartSide Market Share Gains: Siding has become the center of gravity. The Siding segment represents 51% of LP’s sales—an enormous shift for a company that historically lived and died by OSB. And with SmartSide estimated at roughly 5–7% share of the addressable siding market, the bull case says there’s still plenty of room to take share if LP keeps executing.

Management Excellence: A big part of the confidence here comes down to track record. Analysts repeatedly credited Brad Southern’s leadership style—focused, determined, low on drama—with moving LP from commodity producer to specialty player. In their words, he “gets the job done” and operates with “little fanfare,” while materially reducing the company’s risk profile by growing the Siding business.

Capital Allocation Discipline: The company frames Southern’s tenure as a disciplined capital-return era as much as an operating turnaround: “Brad repositioned the company as a global leader in specialty building products, strengthened its financial performance, and built a culture grounded in safety, innovation, and accountability. Under his leadership, LP's share price grew fivefold and the company returned more than $4 billion to shareholders through dividends and share repurchases.”

ESG Tailwinds: Wood has a built-in sustainability narrative: it’s renewable, it stores carbon, and it typically carries lower embodied energy than many alternative materials. As codes, builders, and homeowners increasingly care about those trade-offs, LP can benefit from being on the “wood is part of the solution” side of the conversation.

Bear Case

The bear case isn’t that LP is a bad company. It’s that even a great strategy still lives inside a cyclical industry, with real competitive and reputational scars.

Housing Cycle Risk: LP is still tied to housing activity, and when housing slows, volumes and pricing feel it. The 2023 results show how ugly that can get: full-year net sales fell 33% year over year to about $2.58 billion. Siding is now the largest segment, but a prolonged downturn would pressure both sides of the business.

OSB Commodity Exposure: Even after the transformation, OSB remains a meaningful earnings driver. And when OSB pricing collapses, it can overwhelm everything else in the consolidated results. That’s the uncomfortable setup: the higher-margin siding business can keep improving while reported earnings still get dragged down by a commodity downturn.

Competitive Intensity: James Hardie remains a well-capitalized, highly recognized rival, and vinyl is always waiting at the low end with an aggressive price point. Share gains are possible, but they’re not free—and the fight will stay intense.

Geographic Concentration: LP is heavily North America-focused. That concentration simplifies operations, but it also means the business is disproportionately exposed to U.S. and Canadian housing conditions.

Climate and Supply Chain Risks: Like every wood-products company, LP depends on fiber supply and reliable logistics. Wildfires, timber disease, and broader supply chain disruption can all tighten availability or push costs higher. Climate-related risk, particularly in historically important timber regions like the Pacific Northwest, is part of the backdrop.

Inner-Seal Legacy: LP has largely rebuilt credibility, but the old story hasn’t disappeared. Competitors still reference it, and for some homeowners and contractors, the psychological hurdle remains: trust in siding takes years to earn and seconds to lose.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch

If you want a simple dashboard for whether LP’s reinvention keeps working, watch two numbers that tell most of the story:

1. SmartSide Siding revenue growth and market share: This is the cleanest indicator of whether LP is still taking share and expanding its position. Management has talked about targeting roughly 10–12% annual siding revenue growth; tracking actual performance against that ambition is a direct read on execution.

2. Siding segment EBITDA margin: Growth matters, but profitable growth is the point. Margin trends reveal whether LP is sustaining pricing power and manufacturing efficiency as it scales. Compression can signal competitive pressure or cost headwinds. Margins around the mid-20s, as cited here, reflect a premium positioning that LP has fought hard to earn.

Taken together, these KPIs answer the real question: is LP still becoming more of a branded building-products company, or is it slipping back toward being “an OSB cycle with a siding business attached”?

XII. Epilogue & Reflections

The Louisiana-Pacific story is a masterclass in corporate transformation—and a reminder that in building products, failure isn’t theoretical. It shows up on the outside of someone’s home.

The arc is almost too clean to be real: a company born from antitrust enforcement, spun out as roughly 20% of Georgia-Pacific’s assets. A scrappy competitor that innovated its way into leadership with OSB. An aggressive move into siding that nearly ended the company through the Inner-Seal catastrophe. Years of settlements, restructurings, and reputation repair. And then, finally, a focused reinvention that turned a commodity producer into a differentiated building products business.

Three CEO-led eras shaped that outcome. Mark Suwyn took over after Inner-Seal and absorbed the worst of the fallout, driving the painful work of settlements and restructuring. Rick Frost kept cutting complexity out of the portfolio and set LP up to survive a brutal housing cycle. Then Brad Southern finished the metamorphosis—making siding the centerpiece of the strategy and earning recognition as North American CEO of the Year twice in five years.

The Inner-Seal lesson is the one that lingers, because it’s so hard to come back from. How does a company that had siding failures so severe people joked about mushrooms growing out of walls convince the market to trust it again? LP’s answer was engineering, proof, and time. SmartSide wasn’t positioned as a fresh coat of paint on a damaged brand; it was built to address the specific ways Inner-Seal failed. The zinc borate treatment, the testing programs, and the extended warranties weren’t just features. They were signals—visible commitments meant to rebuild belief jobsite by jobsite.

And maybe the bigger lesson is how rare LP’s escape is. Most commodity companies never get out. They ride the cycle, add capacity at the wrong time, then spend the downturn repairing the balance sheet—only to repeat it all again. LP found a way to stop swinging purely with the market by narrowing its focus. It said no to breadth and yes to depth, building a business where at least part of the portfolio could earn something closer to premium economics.

Looking ahead, the questions are the right kind of questions. Can LP defend its premium positioning as competitors respond? What does the next housing cycle do to momentum? And can new CEO Jason Ringblom keep the flywheel turning? The handoff looks deliberate—Ringblom brings 21 years at LP and deep familiarity with both OSB and siding—but leadership transitions always carry real risk.

The surprising takeaway is what this story says about “boring” businesses. Building products don’t go viral. Nobody daydreams about siding. But homes still get built and repaired. And the companies that master the unsexy stuff—materials science, process discipline, distribution, and trust—can compound value for a very long time.

From antitrust orphan to near-death by defective siding to focused innovator, Louisiana-Pacific’s journey is really about one thing: the power of strategic clarity under pressure. The company that opened America’s first OSB mill in 1979 is still a leading manufacturer today, not because it defended the past, but because it kept forcing itself to become something better than its own history.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music