LivaNova: The Story of Healthcare's Most Unusual Convergence

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

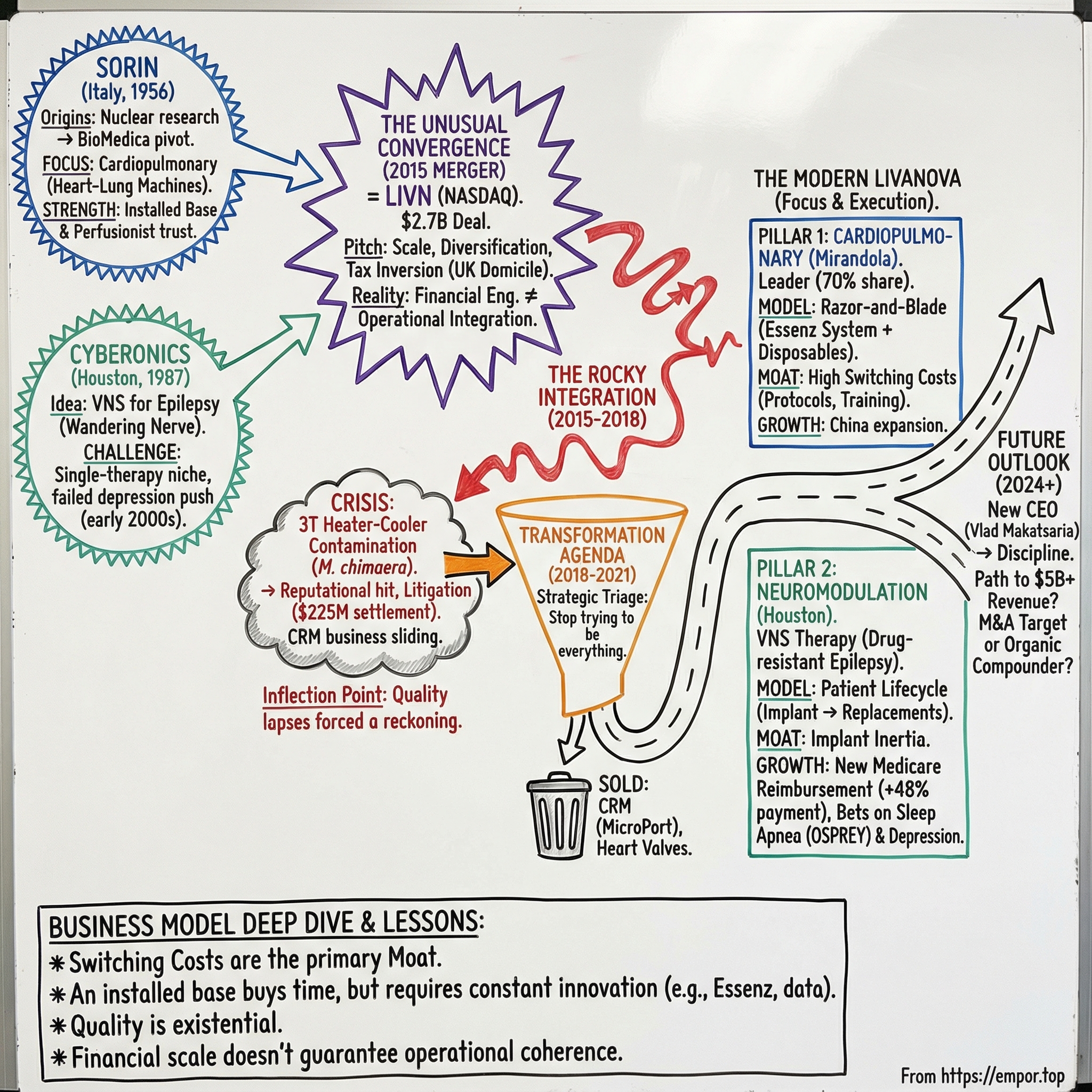

In late October 2015, a newly minted medical device company showed up on the NASDAQ under a new ticker: LIVN. It wasn’t a splashy debut. There was no legendary founder, no garage-to-global arc, no single product that investors could instantly understand. LivaNova arrived quietly, almost like an accounting entry that had somehow become a real company.

But the origin story was anything but ordinary.

LivaNova was created by a transatlantic merger between two businesses that, on paper, had almost nothing to do with each other: Sorin, an Italian cardiac-surgery heavyweight with deep roots in heart-lung machines, and Cyberonics, a Houston-based pioneer of vagus nerve stimulation for epilepsy.

When the companies unveiled the new name, they explained it with the kind of corporate poetry you’d expect: “LivaNova combines a derivation of the English word life with the Latin word for new, embodying our core mission of extending and enhancing life for patients.” Fine. But the more interesting question is the one the name can’t answer:

How did an Italian heart-lung machine legacy collide with a neuromodulation company—and why did that combination make sense?

Because buried inside that merger is a lesson about the medical device business. In the niches where these companies lived, you can build world-class products, earn real clinical trust, and still hit a ceiling. The markets are specialized. Hospitals squeeze pricing. Regulators demand perfection. And scale—true scale—often doesn’t come from one category dominating the world. It comes from strange pairings that let you survive the grind.

The merger itself was announced in March 2015 as a $2.7 billion transaction and closed in October. Overnight, LivaNova became a company operating in more than 100 countries, serving two very different kinds of patients: those on the table for open-heart surgery, and those living with drug-resistant epilepsy.

Officially, the company was formed on February 20, 2015, through the combination of Sorin Group S.p.A.—an Italian firm founded in 1956 with deep expertise in cardiac surgery products—and Cyberonics, founded in 1987, which had spent decades pushing neuromodulation into mainstream medicine. Separated by an ocean and nearly thirty years of history, they ended up sharing the same underlying problem: how do you build durable advantage in medical device markets where innovation is mandatory, but commoditization is relentless?

That’s what makes LivaNova worth studying. This story has everything that defines modern medtech: the power of an installed base, the brutal consequences of quality lapses, regulatory scrutiny that never lets up, and the hard choices of portfolio rationalization—what to double down on, and what to walk away from. And hanging over it all is the existential question every mid-sized device company faces: can you thrive when giants like Medtronic and Abbott set the tempo?

What unfolds from here is a decade-long arc—from a bold merger, through a product crisis that threatened to define the company, to a transformation that narrowed the focus and rebuilt the operating foundation, and finally to a return to growth. It’s what happens when financial engineering meets operational reality in one of healthcare’s most unforgiving arenas.

II. The Cardiopulmonary Origins: Sorin's Italian Engineering Legacy

Picture northern Italy in 1956. The country was still rebuilding from World War II, but Italian industrial giants were already thinking in decades, not quarters. Two of the biggest—Fiat and Montedison—created a new joint venture with a name that sounds like it belongs in a sci-fi novel: Sorin.

Sorin was an acronym for Società Ricerche Impianti Nucleari—literally, the Company for Nuclear Plant Research. And that’s exactly what it was. In its earliest form, Sorin wasn’t a medical device company at all. It was a research laboratory, built to solve the hard problems of nuclear power, equipped with an experimental reactor for materials research. It was meant to be the brain behind the nuclear energy ambitions of two industrial empires.

That origin story matters because nuclear work forces you to become good at everything. Electronics, chemistry, materials science, experimental physics—if you can’t integrate disciplines, you don’t ship anything. Over the next decade, Sorin accumulated that kind of broad, deep technical competence.

Then the ground shifted. When the nuclear power industry ran into crisis after the nationalization of electric utilities, Sorin did what great industrial organizations do when the original mission collapses: it repurposed its capabilities. The company pivoted toward medical technologies and took on a new name, Sorin Biomedica, under the Fiat Group umbrella.

The pivot wasn’t a slow crawl. The conversion worked—within three years, Sorin Biomedica was self-sustaining and profitable. In Italy and across Europe, it became a rare example of a research-first nuclear outfit that had successfully reinvented itself as an industrial company.

To understand why that reinvention stuck, you have to understand the kind of product Sorin moved into: cardiopulmonary bypass.

When a surgeon needs to operate on the heart, the heart can’t keep doing its job. So someone—or rather, something—has to do it for the patient. Blood is diverted outside the body, oxygenated, temperature-managed, and pumped back in. All of this has to happen reliably, continuously, and safely. If the system clots, overheats, contaminates, or fails mechanically, there’s no graceful fallback. The margin for error is essentially zero.

In 1985, Sorin Biomedica went public on the Milan Stock Exchange. By then, it had become a serious European contender in cardiovascular devices. But in medtech, “contender” isn’t the same thing as “global.” To get scale, you often buy it.

That moment arrived in 1992, when Sorin Biomedica acquired Shiley, the Cardiovascular Devices Division of a group headed by Pfizer. Included in that deal were two names that mattered enormously in operating rooms around the world: Dideco, an Italian leader in extracorporeal circulation and autologous blood transfusion products, and Stöckert, a leading producer and distributor of heart-lung machines.

With those acquisitions, Sorin Biomedica began to look like a true international player: leadership in Europe, a broader product line, and a global distribution footprint—particularly strong in Japan, a market that rewarded high-quality, high-reliability surgical systems.

But there was still a glaring gap. The U.S.—the largest device market in the world—remained tough terrain, and Sorin’s penetration there stayed limited. That geographic weakness would hover over the strategy for years.

In the late 1990s, the industry kept consolidating, and Sorin kept expanding. In May 1999, Snia acquired Cobe Cardiovascular, based in Denver, Colorado, a major competitor in cardiac surgery. The deal elevated Sorin Biomedica into the top tier globally and made it the U.S. leader in the category.

Then, in January 2004, following Snia’s partial proportional demerger, Sorin Group—headed by holding company Sorin S.p.A.—was listed independently on the Online Stock Market of Borsa Italiana. It was now a pure-play cardiovascular device business, the kind of focused company that attracts strategic attention when the next M&A wave hits.

By the early 2010s, Sorin had built what would become LivaNova’s most durable competitive asset: dominance in heart-lung machines. The company was the market leader, with an estimated 70% share, and an installed base of roughly 7,000 units worldwide.

That installed base mattered for a simple reason: hospitals don’t switch perfusion systems lightly. Perfusionists train on specific platforms. Entire operating room protocols get built around a particular setup. Once a system is in place and trusted, ripping it out isn’t just a purchasing decision—it’s a workflow change, a training burden, and a clinical risk. Switching costs are enormous.

And that’s where the business model becomes quietly powerful. Sorin’s cardiopulmonary franchise wasn’t just about selling a machine. It was about placing capital equipment, then supplying the oxygenators, tubing sets, cannulae, and other disposables that get used in every procedure. It’s the razor-and-blade model, but in an environment where the “razor” is literally running a patient’s circulation.

Through its full range of cardiopulmonary equipment and consumables—anchored by the world’s leading heart-lung machine—the company supported millions of patients over decades. And long before the name “LivaNova” existed, the moat was already being built: an installed base, embedded relationships, and a recurring revenue stream tied directly to surgical volume.

III. The Neuromodulation Path: Cyberonics and the Vagus Nerve

While Italian engineers were perfecting heart-lung machines, a completely different bet was taking shape in Houston. In 1987, Cyberonics was founded around a single, audacious premise: treat epilepsy with an implanted device.

The idea was almost heretical in its simplicity. Instead of operating on the brain or relying solely on drugs, what if you could modulate seizures by stimulating the vagus nerve—the “wandering” nerve that runs from the brainstem down through the neck and into the torso, touching systems that control everything from heart rate to digestion?

Not long after founding, Cyberonics earned an investigational device exemption to begin clinical studies of its implantable pulse generator and lead system, based on encouraging animal results. The first vagus nerve stimulator implant in an adult patient with drug-resistant epilepsy happened that same year. Even then, the concept felt like science fiction: a peripheral nerve in the neck as a control knob for electrical storms in the brain, with stimulation settings that could be adjusted without another surgery.

The science, though, wasn’t neat. The mechanism of action was still poorly understood. The early clinical results were meaningful but not miraculous—more “fewer seizures” than “seizure-free.” And the business hurdles were just as real: persuading neurologists and surgeons to adopt a new procedure, and convincing payers to reimburse it.

Still, Cyberonics pushed forward. In July 1997, the FDA approved the VNS Therapy System as an adjunctive treatment for adults and children over 12 with partial-onset seizures refractory to drugs. Over time, the platform iterated—eventually reaching five generations of technology—and the installed base grew. Within five years of approval, more than 16,000 patients had been implanted, and VNS had become a recognized option for medically refractory seizures.

By the early 2000s, Cyberonics had carved out a real niche. But it also ran into the classic problem of a single-therapy company: once you’ve established yourself, where do you go next?

The most obvious expansion was depression. Given the vagus nerve’s connections to brain regions tied to mood regulation, it was a logical swing. In July 2005, the FDA approved Cyberonics’ VNS implant for chronic or recurrent depression—unipolar or bipolar—in patients who had failed to respond to at least four antidepressant interventions. Then the commercial reality hit. CMS declined to cover VNS for serious depression, and in 2007 concluded the evidence wasn’t compelling enough to warrant broader coverage.

That decision didn’t just slow the depression business. It effectively froze it. The indication had consumed time, attention, and money without turning into meaningful revenue—an overhang that would trail the company for years.

Meanwhile, even the core epilepsy opportunity had structural friction. Roughly one in three people with epilepsy are drug-resistant, yet only a small fraction of eligible patients ever receive VNS therapy. The reasons weren’t one thing; they were everything: uneven physician awareness, reimbursement complexity, reluctance to undergo an implant procedure, and the steady march of new anti-seizure medications that kept delaying when a patient was considered “drug-resistant” enough to move to devices.

The technology, however, kept getting better. A key leap came with AspireSR in the mid-2010s. Instead of delivering stimulation on a fixed schedule alone, AspireSR monitored relative changes in heart rate—particularly ictal tachycardia—and could automatically deliver extra stimulation when a seizure was likely underway. It was an early step toward closed-loop neuromodulation: not just “stimulate and hope,” but “detect and respond.”

So by the time Cyberonics approached its eventual merger, the picture was complicated in a very medtech way. It owned a leading position in a real, FDA-approved therapy with years of clinical use. But it had limited avenues to expand, a costly depression detour that hadn’t paid off, and growing pressure to find a new strategic path.

In other words: Cyberonics needed a reset. And across the Atlantic, so did Sorin.

IV. Parallel Journeys: Two Companies, Two Continents (1990s–2014)

Through the 1990s and 2000s, Sorin and Cyberonics ran on parallel tracks. They were in different countries, selling into different departments of the hospital, and solving different clinical problems. But the pattern was the same: build something real, hit the limits of a niche market, then go looking for the next move.

On Sorin’s side, the company kept buying its way into adjacent cardiac categories. In May 2001, the Snia Group purchased Ela Medical from Sanofi-Synthélabo. Ela Medical brought production facilities in Paris, a meaningful patent portfolio, and—crucially—a direct sales presence in the United States, plus a lineup of FDA-approved products. It also strengthened Sorin in cardiac rhythm management: pacemakers and implantable defibrillators.

On paper, CRM looked like the perfect complement to cardiac surgery. In reality, it became a strategic headache.

Cardiac surgery equipment rewarded Sorin’s installed base and technical credibility. CRM was a knife fight against giants. The category was dominated by Medtronic, St. Jude Medical (later Abbott), Boston Scientific, and Biotronik. Competing meant relentless R&D just to keep up, plus pricing pressure that never eased.

And that pressure was getting worse across medtech. Large hospital systems consolidated. Group Purchasing Organizations pulled more volume under centralized contracts. Price competition ground margins down. Features that once differentiated a product became basic expectations in the next generation.

Meanwhile, Cyberonics kept pushing VNS forward. The epilepsy business grew, but it grew the way many device therapies grow: steadily, and with friction. Adoption depended on physician education, procedure willingness, and reimbursement—all of which took time and constant commercial effort. The technology improved, too, setting Cyberonics up for what would become a key product cycle with AspireSR, designed to respond to likely seizures by monitoring heart-rate changes. That next generation would matter, but it wouldn’t solve the company’s bigger issue: it was still fundamentally a one-therapy business.

By 2014, the strategic tension on both sides was hard to ignore. Sorin had a dominant but maturing cardiopulmonary franchise, a CRM business stuck in brutal competition, and heavy exposure to Europe. Cyberonics had a category-defining neuromodulation franchise that was still underpenetrated, a costly depression expansion that never turned into a business, and comparatively limited scale outside the U.S.

At the same time, the broader industry was rewriting the rules through M&A. The 2010s wave wasn’t just about product portfolios; it was also about corporate structures. Medtronic’s acquisition of Covidien—combined devices with hospital supplies and relocated the combined company to Ireland—became the template everyone studied. Tax inversion wasn’t the only rationale, but it was clearly part of the playbook.

That context matters, because when Sorin and Cyberonics moved toward each other, the structure was deliberate. LivaNova PLC—organized under the laws of England and Wales—was formed on February 20, 2015 to facilitate the business combination between Cyberonics, a Delaware corporation, and Sorin, an Italian joint stock company. When the transaction closed on October 19, 2015, LivaNova became the holding company for both businesses. Its ordinary shares began trading on the NASDAQ Global Market and were also admitted to listing in the U.K.

The U.K. domicile wasn’t a coincidence. It offered favorable tax treatment while keeping the company plugged into both U.S. and European capital markets. And the deal mechanics mattered too: Cyberonics was treated as the accounting acquirer for reporting purposes, even as Sorin’s larger revenue base became the operational foundation of the combined company.

V. The 2015 Merger: Creating LivaNova

On February 26, 2015, Sorin and Cyberonics dropped a deal that made plenty of people in medtech do a double-take. Italian heart surgery equipment and Houston epilepsy implants weren’t exactly a natural pair. So what, exactly, was the connective tissue?

The companies announced an all-stock merger to form a new global medical technology holding company. On a pro forma basis, the combined equity value was about $2.7 billion, with Cyberonics shareholders expected to own roughly 54% of the new entity and Sorin shareholders about 46%.

The pitch had three layers.

First was scale. Neither company, on its own, had the size to comfortably fund the R&D pipeline, the regulatory work, and the global commercial footprint that modern medtech increasingly demanded. The plan was to operate as three business units—Cardiac Surgery, Cardiac Rhythm Management, and Neuromodulation—with operating headquarters in Mirandola (Italy), Clamart (France), and Houston (U.S.). In total, LivaNova would span more than 100 countries and employ around 4,500 people.

Second was diversification. Instead of being exposed to the ups and downs of a single niche, the combined company would have revenue streams tied to two very different clinical worlds: the cardiac operating room and the epilepsy clinic. In theory, what hurt one side of the house wouldn’t necessarily hurt the other.

Third—and this was the part everyone understood even if not everyone loved—was tax optimization. By domiciling the new holding company in the U.K., LivaNova could target a lower effective tax rate than either legacy company could achieve alone.

Then came the process of turning the idea into a public company. U.S. antitrust clearance under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act arrived on April 30, 2015. Sorin shareholders approved the transaction on May 26, 2015. Cyberonics shareholders followed on September 22. The merger closed on October 19, 2015.

That same day, LivaNova’s ordinary shares began trading on NASDAQ and were also admitted to listing on the standard segment of the FCA’s Official List and to trading on the Main Market of the London Stock Exchange, under the ticker “LIVN.”

With the deal done, management laid out the usual promise of merger math: restructuring plans meant to capture economies of scale, remove duplicated corporate costs, and streamline distribution, logistics, and office functions. More broadly, the company said the combination should create revenue enhancements, cost savings, and synergy opportunities—plus greater geographic and product diversity and improved growth prospects.

But underneath the synergy slide was a harder reality: this was not an easy integration.

Start with culture. Sorin came out of an Italian manufacturing tradition built over decades. Cyberonics was a Texas medical device company shaped by the rhythms of the FDA and U.S. reimbursement. Then there was the go-to-market problem: Sorin’s world revolved around perfusionists and cardiac surgeons. Cyberonics lived with neurologists and neurosurgeons. The customer bases barely touched, and the sales motions didn’t rhyme.

Even the org chart told you how complicated this would be. LivaNova would run three business units across three operating hubs—Mirandola, Clamart, and Houston—spanning three continents.

Three business units. Two very different clinical specialties. One stock price.

KEY INFLECTION POINT #1: The merger fundamentally repositioned both companies from niche players to a diversified platform. But as would soon become painfully clear, financial engineering did not equal operational integration.

VI. The Rocky Integration Years (2015–2018)

The integration wobbled almost from day one. Management talked about synergies and scale, but inside the most important part of Sorin’s legacy—the cardiopulmonary franchise—something far more dangerous was unfolding. A slow-moving manufacturing contamination crisis was building into an existential threat.

In the spring of 2015, investigators in Switzerland reported a cluster of six patients with invasive infection from Mycobacterium chimaera, a species of nontuberculous mycobacterium commonly found in soil and water. The patients had all undergone open-heart surgery where heater-cooler devices were used during extracorporeal circulation.

The product at the center of the storm was the Stöckert 3T Heater-Cooler. It wasn’t an obscure accessory; it was a widely used support device in cardiac operating rooms, and a recognizable Sorin workhorse. Then, in July 2015, a hospital in Pennsylvania reported a similar cluster: invasive nontuberculous mycobacterial infections in open-heart surgery patients. The field investigation again pointed to exposure to contaminated Stöckert 3T units—manufactured by LivaNova.

The clinical picture was brutal. Patients could develop prosthetic valve endocarditis, vascular graft infections, and signs of disseminated mycobacterial infection. And when these infections took hold, outcomes could be devastating, with high recurrence and mortality rates.

By 2015, it was no longer a one-country anomaly. An international outbreak of M. chimaera infections among cardiothoracic surgery patients had been associated with exposure to contaminated LivaNova 3T heater-cooler units (formerly the Stöckert 3T system).

The question quickly became: how does a device that never even touches the patient end up implicated in a deadly infection? And where did the contamination begin?

The most alarming clue would come later. In mid-July 2017, a study in The Lancet reported traces of M. chimaera in LivaNova’s German-based factory. Researchers matched samples from the facility to bacteria found in patients, concluding that contamination of heater-cooler units at the factory “seems a likely source” for severe infections diagnosed across Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, the U.K., the U.S., and Australia.

The scale of exposure was staggering. It has been estimated that more than 500,000 people underwent surgeries involving the Stöckert 3T heater-cooler during the period when contamination was linked to the devices.

The regulatory and legal fallout followed. In February 2018, a federal panel consolidated 39 federal lawsuits from 21 U.S. districts into multidistrict litigation, MDL No. 2816, in the Middle District of Pennsylvania.

LivaNova later agreed to pay $225 million to resolve roughly 75% of U.S. lawsuits alleging contaminated heater-cooler devices caused serious infections during open-chest surgeries.

For a company with a market cap under $3 billion, $225 million was a real financial blow. But the deeper damage was to the asset Sorin had spent decades compounding: trust. The cardiopulmonary franchise was built on the belief that these systems are safe, reliable, and engineered for worst-case scenarios. The 3T crisis punctured that belief in the most public way possible.

At the same time, the third leg of the merger—the cardiac rhythm management business—kept sliding. CRM sales fell sharply, down 21.8% on a constant-currency basis. Management characterized the weakness in the second half of 2015 as expected and previously communicated, but the underlying reality didn’t change: CRM was a brutally competitive category where LivaNova simply didn’t have the scale to dictate terms.

By 2017, leadership acknowledged what the numbers had been saying. On September 14, 2017, LivaNova announced it was reviewing strategic options for the CRM Business Franchise, including a potential divestiture.

That review ended quickly. On April 30, 2018, LivaNova announced it had completed the sale of its CRM business to MicroPort Scientific for $190 million in cash.

“With the completion of the CRM sale to MicroPort, LivaNova’s portfolio is now concentrated on our areas of strength and leadership—cardiac surgery and neuromodulation,” said Damien McDonald, LivaNova’s chief executive officer.

It was strategic triage: exit a subscale business and concentrate resources where LivaNova could plausibly lead. But it came with a catch. CRM had generated about $249 million in net sales in fiscal year 2016—revenue the company would now have to replace through organic growth, all while managing a crisis that was shaking its core franchise.

KEY INFLECTION POINT #2: The 3T crisis forced LivaNova to confront quality and operational issues that had festered during the merger integration. The company emerged more focused—two business units instead of three—but with a damaged reputation that would take years to repair.

VII. The Transformation Agenda (2018–2021)

After the CRM exit and the 3T fallout, LivaNova didn’t have the luxury of grand narratives. It needed operational excellence—fast. The strategy that emerged was intentionally simple: stop trying to be everything, and rebuild around what the company could actually lead.

From that point on, LivaNova ran as two franchises: Cardiac Surgery, headquartered in Mirandola, Italy, and Neuromodulation, run out of Houston.

The cleanup continued. Another legacy Sorin asset—the heart valve business—was no longer core. In 2020, LivaNova announced the sale of its heart valve (HV) business. That unit went on to become Corcym.

With the portfolio narrowing, the company could finally put more energy into moving the products forward. In cardiopulmonary, that showed up in Essenz, the next-generation perfusion platform. Essenz wasn’t pitched as a minor refresh. It was meant to be a step-change: a new heart-lung machine paired with a new patient monitoring system, built around direct feedback from perfusionists and the realities of the operating room. The design focused on practical details that matter when the stakes are life and death—an ergonomic layout, cleaner cable management to reduce distractions, and mast-mounted pumps that improve disposable positioning. That in turn could reduce priming volume and limit hemodilution.

The message was clear: this was a franchise built over decades of trust with perfusionists, and it was doubling down on safety, reliability, and workflow.

On the neuromodulation side, the push was less about hardware and more about proof. LivaNova invested in building the clinical evidence base and leaned into real-world data—work it planned to showcase publicly, including a slate of presentations at the American Epilepsy Society Annual Meeting. Much of that centered on CORE-VNS, described as the largest prospective, multinational observational study of VNS Therapy for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy, along with new health economics analyses.

CORE-VNS became a flagship data point for the story LivaNova wanted to tell: that VNS produced substantial seizure reductions over time. The company highlighted results at 36 months showing an overall median seizure reduction of 80% for focal onset motor seizures with impaired awareness, and 95% for focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures.

Then the world shut down. In early 2020, COVID-19 tore through hospital operations and crushed elective procedure volumes. Cardiac surgeries were postponed. Epilepsy implants were delayed. For a company tied so directly to procedure flow, the hit was immediate. But the recovery was also faster than many expected, as hospitals fought through backlogs and restarted deferred care.

In March 2020, LivaNova also launched Epsy Health, a digital health unit designed to support epilepsy patients, caregivers, and providers. It was a nod to a broader realization in medtech: the device is only part of the outcome. Education, adherence, monitoring, and patient engagement can be just as important—and they’re also where new value can be created.

Underneath all of this was a quieter, equally important shift: financial discipline. LivaNova reduced debt, worked to improve margins, and slowly rebuilt credibility with investors. After collapsing from above $80 before the 3T crisis to below $50, the stock began to recover as the company proved it could operate like a focused, modern medtech business again.

VIII. The Modern Era: Innovation & Strategic Choices (2021–Present)

As the turnaround took hold, leadership started to change too—and this time, the changes were about what came next, not what went wrong last time.

In April 2023, CEO Damien McDonald resigned. The board chair, Bill Kozy, stepped in on an interim basis while LivaNova went looking for an outside operator with big-company reps.

They found one. On February 5, 2024, LivaNova announced that its Board of Directors had named Vladimir A. Makatsaria chief executive officer and a member of the board, effective March 1, 2024.

Makatsaria most recently served as Company Group Chairman at Johnson & Johnson MedTech, leading its global Ethicon surgery business. Before that, he spent 27 years at Johnson & Johnson in executive leadership roles across technologies and geographies.

The J&J pedigree mattered. LivaNova wasn’t just trying to “do better.” It needed repeatable operating discipline, sharper commercial execution, and a CEO who could keep the core franchises moving while also creating strategic options. As Kozy put it, “Vlad is a respected leader in the medical device industry with a proven reputation for delivering results, driving innovation and building great teams.”

The numbers suggested the transformation wasn’t just narrative. In the fourth quarter, revenue was $321.8 million, up 3.8% reported. Full-year 2024 revenue was $1.25 billion, up 8.7% reported—up 9.3% on a constant-currency basis and 10.7% organically versus the prior year.

“In 2024, LivaNova delivered strong revenue growth, expanded operating margin, and significantly improved cash generation,” Makatsaria said. He also pointed to clinical progress in two newer bets: obstructive sleep apnea and difficult-to-treat depression.

On the legacy engine—cardiopulmonary—momentum was clear. In the third quarter of 2025, Cardiopulmonary revenue rose 18.0% reported and 15.9% constant-currency versus the third quarter of 2024, with growth across all regions. The drivers were exactly what you’d expect in a razor-and-blade franchise: Essenz Perfusion System placements, and strong demand for consumables.

China, in particular, loomed large in the story. With cardiovascular disease affecting 330 million individuals and more than 700 hospitals equipped for cardiac surgery, demand for cardiopulmonary bypass solutions was growing—and LivaNova wanted to be there as that system modernized.

Neuromodulation was a little less clean, but still growing. Third-quarter 2025 Neuromodulation revenue increased 6.9% reported and 6.4% constant-currency versus the third quarter of 2024, with growth across all regions.

Then came a very specific, very medtech catalyst: reimbursement.

In November 2025, the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services assigned VNS Therapy to a New Technology Ambulatory Payment Classification for new patient implants. Provider reimbursement under Medicare for VNS Therapy drug-resistant epilepsy procedures was set to increase significantly, with hospital outpatient payments rising by approximately 48% for new patient implants and 47% for end-of-service procedures versus 2025 rates.

LivaNova said the change should improve hospital economics for VNS Therapy, making the procedure more sustainable for providers—and, crucially, lowering one of the barriers to broader patient access.

At the same time, the company kept pushing beyond its two core franchises into adjacent indications. The OSPREY clinical study for moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnea met its primary safety and efficacy endpoints, showing significant reductions in apnea-hypopnea index. And in difficult-to-treat depression, two pivotal articles were published on the treatment-resistant depression unipolar cohort data set in the RECOVER clinical study, demonstrating the effectiveness of active VNS Therapy.

With that backdrop, LivaNova said it expected full-year 2025 revenue growth of 8.5% to 9.5% on a constant-currency basis. Adjusted diluted earnings per share for 2025 was expected to be $3.80 to $3.90.

KEY INFLECTION POINT #3: The shift from integration and survival mode to growth mode became real. With focused innovation in the core franchises and geographic expansion as a key lever, LivaNova entered 2025 positioned for sustained performance.

IX. The Business Model Deep Dive

Cardiopulmonary Franchise

The cardiopulmonary business looks simple from the outside—and that’s exactly why it’s so competitive. LivaNova is the market leader in heart-lung machines, with an estimated 70% share and an installed base of roughly 7,000 units worldwide.

That installed base is the whole game. Hospitals don’t switch perfusion platforms lightly. This is mission-critical equipment, embedded in protocols, training, and muscle memory. LivaNova’s Essenz Perfusion System leans into that reality: a modern platform built with perfusionists, designed to fit the operating room workflow, and set up to keep improving over time. With continuously recorded data and events captured on the Essenz Patient Monitor, the system also strengthens traceability—an unglamorous feature that becomes very glamorous when something goes wrong.

Economically, it’s classic razor-and-blade. Place the capital equipment once, then earn years of recurring revenue on the consumables that every case requires: oxygenators, tubing sets, and other single-use components. With hundreds of thousands of cardiac surgeries performed annually in the U.S. alone, those “blades” add up quickly.

But this isn’t a sleepy annuity. Innovation still matters, and competitors don’t sit still. Getinge, Terumo, and Medtronic all keep investing, and in some markets local competitors like LifeSeeds are pushing hard as well. Essenz is a meaningful upgrade, but in a market like this, the goal isn’t to reinvent the category overnight. It’s to win placements, protect the installed base, and make switching feel not just inconvenient—but irrational.

Neuromodulation Franchise

Neuromodulation is a different kind of machine. VNS Therapy is clinically proven safe and effective as an add-on treatment to reduce seizure frequency in adults and children as young as 4 years old with drug-resistant epilepsy and partial onset seizures. And that patient population is enormous: roughly one in three people with epilepsy are drug-resistant.

The business model here is built around the patient lifecycle. Once a VNS device is implanted, the relationship doesn’t end—it deepens. Programming visits keep physicians engaged over time, and eventual battery replacements, often every 5 to 8 years, create recurring end-of-service revenue. And the biggest moat is obvious: once the device is in, switching isn’t a casual decision. A competitor has to persuade a patient and a physician not just to try something new, but to commit to a different therapy approach.

There’s also an economic argument alongside the clinical one. A cost analysis found the company’s VNS Therapy System was associated with lower resource utilization and lower costs for drug-resistant epilepsy patients versus continued treatment with anti-epileptic drugs. In that analysis, the initial costs of the device, placement, and programming were estimated to be offset about 1.7 years post-implant, with an estimated net cost savings of $77,480 per patient over five years.

And yet: penetration is still low. More than 125,000 VNS devices have been implanted globally. Against a population of millions who could be eligible, that’s underpenetration—and it’s the source of both frustration and upside.

The broader neuromodulation market includes heavyweight competitors like Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott, LivaNova PLC, and Nevro Corp. In VNS specifically for epilepsy, LivaNova remains the dominant player, even as other neuromodulation approaches compete for similar patients.

Financial Profile

By 2024, LivaNova generated $1.25 billion in revenue, up from $1.15 billion in 2023.

Its gross margin was 69.45%. Operating margin was 15.53%, while net margin was -16.14%. The gap tells you something important: the underlying device franchises are high-margin, but reported profitability has been weighed down by legacy litigation costs and non-cash charges.

Over the last 12 months, operating cash flow was $216.59 million and capital expenditures were $54.49 million, resulting in free cash flow of $162.10 million.

At the time of these figures, LivaNova’s market capitalization was $2.91 billion.

X. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces

1. Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-LOW

In medical devices, “new entrant” usually means “someone willing to burn years of time and a mountain of capital before selling a single unit.” Getting through the FDA often requires large clinical trials and deep regulatory expertise. In Europe, CE Mark still demands rigorous quality systems and documentation. And even if you clear regulators, you still have to earn your way into hospitals—one clinical team at a time.

You can see those barriers in the timeline. LivaNova’s VNS therapy was approved in 1997. NeuroPace’s responsive neurostimulation (RNS) didn’t get approval until 2013. And Medtronic’s DBS targeting the anterior nucleus of the thalamus for epilepsy arrived in 2018. That long gap isn’t because no one had ideas—it’s because turning an idea into a reimbursed, implanted therapy is brutally hard.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MODERATE

LivaNova buys highly specialized components, but it generally has more than one sourcing option for critical inputs. The bigger supplier risk is less about part scarcity and more about manufacturing reality: when your sites and processes are regulator-approved, any quality issue can become a production stop, not just a nuisance.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

Hospitals have consolidated, and purchasing has professionalized. GPOs negotiate on behalf of thousands of hospitals. Value-based care brings cost scrutiny into decisions that used to be driven almost entirely by clinician preference.

For a mid-sized player, that environment is unforgiving. LivaNova can win on performance, service, and installed-base inertia, but it has less sheer scale than the largest competitors to absorb pricing pressure, bundle across categories, or integrate newly acquired technologies quickly.

4. Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

In epilepsy, VNS doesn’t compete in a vacuum. It sits alongside other device-based options like NeuroPace’s RNS and DBS approaches, plus ongoing advances in drug therapies and the possibility of future gene therapies. NeuroPace emphasizes a key difference: its system uses intracranial EEG to detect patient-specific seizure activity and respond in real time, while VNS and DBS generally deliver stimulation on a set schedule rather than adapting moment-to-moment.

In cardiopulmonary, substitutes are less direct, but change still happens. ECMO technologies continue to evolve, even if they’re typically used in different clinical scenarios than routine cardiopulmonary bypass.

5. Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

LivaNova operates in categories where the competition is serious and well-funded. Across its markets, it runs into names like Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott Laboratories, Edwards Lifesciences, and Smith & Nephew. In neuromodulation specifically, Medtronic, Abbott, and LivaNova together represent a large portion of the global market—meaning rivalry tends to show up as feature competition, sales execution, and pricing pressure, not a lack of credible alternatives.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

In medtech, scale helps in the unglamorous places: paying for R&D, absorbing regulatory costs, and running high-quality manufacturing at volume. But it’s not a winner-take-all industry. Several companies can hold profitable positions in the same category.

2. Network Economies: WEAK

A heart-lung machine doesn’t get better because more hospitals use it. A VNS implant doesn’t become more effective because more patients have one. There’s no real network effect.

3. Counter-Positioning: WEAK

LivaNova doesn’t have a business model that incumbents are structurally unable to copy. If a feature matters, competitors can pursue it.

4. Switching Costs: STRONG

This is the anchor of the whole company. In cardiopulmonary, hospitals build workflows, training, and protocols around a perfusion platform, and the cost of switching is operational and clinical—not just financial. In neuromodulation, the switching cost is even more literal: an implanted device creates enormous inertia, because patients rarely explant one system just to trial a competing brand.

5. Branding: MODERATE

Sorin’s heritage still carries weight in cardiac surgery environments, especially with perfusionists. VNS Therapy has meaningful recognition in the epilepsy community. But this is professional branding—earned in clinics and ORs—not consumer branding.

6. Cornered Resource: WEAK-MODERATE

LivaNova has patents and a growing body of clinical and real-world evidence. Those matter, but they’re not permanent monopolies.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

Precision manufacturing, regulatory execution, and clinical support are learned capabilities that compound over time. And in hospital-based medtech, relationships are built slowly—often one clinical champion at a time.

Overall Assessment: LivaNova’s competitive position rests primarily on switching costs in both franchises. The installed base buys the company time, but not immunity—staying relevant still depends on continuous innovation and flawless execution.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Thesis

The Bull Case

Installed base durability: LivaNova sits in a privileged spot in cardiopulmonary. As the market leader in heart-lung machines, with an estimated 70% share, it benefits from exactly the kind of inertia you want in medtech: hospitals standardize, perfusionists train on a platform, and switching feels risky. Once you’re in, you tend to stay in.

Neuromodulation underpenetration: VNS is a proven therapy with real scale—more than 125,000 implants globally—but it’s still small relative to the number of drug-resistant epilepsy patients who could qualify. Even with competing approaches like responsive neurostimulation reaching more than 15,000 patients by 2024, this is still an early-market story. If LivaNova can turn awareness, referrals, and procedure access into a smoother pipeline, the ceiling is much higher than the current installed base.

Reimbursement tailwinds: One of the biggest bottlenecks in neuromodulation is whether hospitals can make the economics work. The Medicare reimbursement change for VNS Therapy drug-resistant epilepsy procedures—raising hospital outpatient payments by roughly 48% for new patient implants—should make it easier for providers to say yes, which can translate into more access and more volume.

Emerging markets growth: The cardiopulmonary franchise doesn’t have to be a “developed markets only” annuity. China, in particular, matters. It’s already the second-largest market for heart-lung machines after the United States, and as cardiac surgery capacity expands, LivaNova has a chance to ride that build-out.

Valuation discount: On Wall Street, LivaNova is still treated like a mid-cap with baggage. The average price target of $59.71 implies upside of about 8% from the current price, and the consensus rating is “Strong Buy.” The bet embedded in that optimism is straightforward: the crisis era is fading, and the underlying franchises deserve a higher-quality multiple.

The Bear Case

Structural healthcare cost pressures: Hospitals and payers are in permanent cost-containment mode. Even great devices get pulled into price negotiations, and procurement teams have become more powerful. That’s a tough environment for any medtech company, especially one without massive scale.

Competition intensifying: LivaNova competes against giants that can outspend it for years. Medtronic’s R&D spend alone—roughly $2.7 billion per year from 2022 through 2024—signals how relentless the arms race is. LivaNova’s R&D budget is a fraction of that, which raises the bar for focus and execution.

Technology risk: The biggest threat isn’t always a direct competitor with a similar device. It’s the next modality entirely—new pharmaceuticals, genetic approaches, or alternative forms of neuromodulation that change the standard of care and make today’s solutions feel like stepping-stones.

Limited scale: Being mid-sized cuts both ways. LivaNova can be more focused, but it also has less margin for error—and less organizational bandwidth to absorb the complexity of integrating new technologies through acquisition and then optimizing them globally.

Litigation overhang: The 3T heater-cooler litigation remains a shadow, and the SNIA Italian litigation adds another layer of uncertainty. Even when the core business performs, these issues can shape investor sentiment and reported results.

Critical KPIs to Track

1. VNS New Patient Implant Growth Rate: This is the cleanest read on whether neuromodulation is truly expanding. If new implants outpace end-of-service replacements, penetration is improving. If not, growth may be more about maintaining the installed base than building a bigger therapy franchise.

2. Cardiopulmonary Organic Revenue Growth: Organic growth, stripped of currency noise, tells you whether the cardiopulmonary installed base is actually compounding—through new placements and stronger consumables pull-through—or simply holding position under pricing pressure.

XII. Epilogue: What Does the Future Hold?

The medical device industry is still consolidating, and that means the question never really goes away: does LivaNova eventually get bought? Every few years, the speculation resurfaces—usually framed the same way. A larger player could want cardiopulmonary scale, neuromodulation capabilities, or simply the kind of durable installed base that throws off recurring revenue. LivaNova is big enough to matter, but not so big that it’s untouchable.

At the same time, technology is converging in ways that cut both directions. Advances like adaptive deep brain stimulation, which uses real-time neurofeedback to personalize therapy, are pushing neuromodulation toward a more responsive, data-driven future. Players like Medtronic and Boston Scientific are pushing hard here, with directional leads and cloud-enabled monitoring platforms that make therapy more precise and easier to manage over time.

LivaNova’s response so far has been to stay disciplined: innovate inside its franchises, and expand indications where it has a credible right to win. One of the clearest examples is OSPREY, its clinical study in moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnea, which met its primary safety and efficacy endpoints. If that program ultimately translates into approval and adoption, sleep apnea could open a much larger market than epilepsy alone.

The same logic applies to difficult-to-treat depression. LivaNova has continued to notch clinical milestones in both depression and sleep apnea, aiming to take VNS beyond its original home territory. If VNS can become a meaningful platform across multiple conditions—rather than a single-indication workhorse—the ceiling rises fast.

So what would it take for LivaNova to become a $5B+ revenue company? There isn’t one lever—there are a few plausible ones. VNS penetration could improve, helped by better reimbursement and smoother referral pathways. New indications like sleep apnea or depression could become real commercial engines. Cardiopulmonary could keep compounding through placements and consumables, especially as emerging markets expand surgical capacity. Or LivaNova could choose to accelerate the timeline through transformational M&A.

Today, LivaNova is headquartered in London, has approximately 3,000 employees, and operates in more than 100 countries—serving patients, clinicians, and healthcare systems around the world.

And maybe that’s the cleanest ending: the company born from one of healthcare’s strangest mergers turned out to be more durable than the skeptics expected. A decade after combining Italian heart-lung machines with Texas epilepsy stimulators, LivaNova found coherence—not through obvious cross-selling synergies, but through focus, evidence, and execution.

XIII. Closing Reflections & Lessons

Biggest surprise: A merger driven by tax optimization and scale ambitions still produced a real operating company. The “obvious” synergies never truly showed up—cardiopulmonary and neuromodulation largely stayed separate worlds—but focus and disciplined execution eventually did.

The integration lesson: Financial engineering is not operational integration. The 3T crisis was the blunt reminder that you can merge org charts without merging quality systems or manufacturing culture. In medical devices, there’s no margin for sloppy handoffs.

Quality matters: The 3T heater-cooler episode showed how fast a market-leading position can be compromised by a quality failure. And the recovery curve is asymmetrical: trust takes years to rebuild, even if the fix itself is straightforward.

Switching costs as moat: LivaNova’s durability comes from switching costs in both franchises. Hospitals don’t swap perfusion platforms casually. Patients don’t trade implanted neuromodulation devices the way they change prescriptions. That inertia creates stability—but it also raises the standard: if you’re going to benefit from long-term relationships, you have to keep earning them.

Innovation imperative: An installed base buys time, not a free pass. Essenz, SenTiva, and the pipeline programs have to keep proving their value in outcomes, workflow, and economics—or competitors will slowly pry open the door.

Geographic diversification: Europe has been a strength, the U.S. has been more challenging, and emerging markets represent the next big opportunity. That mix brings currency and macro exposure, but it also gives the company real growth optionality if it executes.

Key strategic questions for the board: - When does neuromodulation reach a scale where it deserves standalone valuation—or even standalone strategy? - Is the right path to build critical mass through larger M&A, or to keep compounding through focused organic growth? - How aggressively should capital be split between strengthening the core franchises and funding adjacent bets like sleep apnea and depression? - If private equity or strategic buyers come calling, what’s the line between “interesting” and “too early”?

XIV. Resources for Further Research

If you want to go deeper on the merger mechanics, the 3T heater-cooler crisis, and the clinical evidence behind VNS Therapy, these are the most useful starting points.

Primary Sources: 1. LivaNova Investor Relations: annual reports and SEC filings (especially 2015–2024) for the merger, the portfolio changes, and the transformation program 2. FDA MAUDE Database: adverse event reports tied to the 3T heater-cooler and related regulatory activity (2016–2017 is a key window) 3. ClinicalTrials.gov: registered studies for VNS Therapy across epilepsy, depression, and sleep apnea

Academic and Clinical: 4. Frontiers in Medical Technology: “Evolution of the Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) Therapy System Technology for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy” 5. CORE-VNS publications: prospective, real-world evidence on VNS outcomes over time

Industry Context: 6. EvaluateMedTech: reporting on medtech consolidation trends and market dynamics 7. Competitor investor materials: Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and NeuroPace updates on neuromodulation strategy and product roadmaps 8. Industry conference transcripts: JPM Healthcare and Baird Healthcare conference commentary for management tone, guidance, and shifting narratives

Regulatory and Legal: 9. CDC and FDA safety communications: official guidance and updates on heater-cooler devices and M. chimaera risk 10. MDL No. 2816 filings: court documents covering the federal heater-cooler litigation in the U.S.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music