LifeStance Health: Building America's Mental Healthcare Giant

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s a Thursday afternoon in suburban Atlanta. A working mother has just left a voicemail with the third therapist’s office she’s called this week. The first two aren’t accepting new patients. The third can’t see her daughter for four months. Her teenage daughter’s anxiety has been spiraling since the pandemic, and getting help feels less like healthcare and more like trying to win a spot in an invisible line.

That scene isn’t rare. It’s the default.

Into that gap stepped LifeStance Health. Founded in 2017, the company set out to do something deceptively simple: make it easier to actually access mental healthcare. It built a national outpatient platform that offers both in-person and virtual care for children, adolescents, and adults across a wide range of conditions. Headquartered in Scottsdale, Arizona, LifeStance is one of the biggest bets anyone has made on modernizing—and consolidating—America’s famously fragmented behavioral health system.

By the company’s most recent quarter, LifeStance reported $363.8 million in revenue, up 16% year-over-year. Its clinician base had grown to nearly 8,000 providers. It served patients across 33 states through more than 550 centers, with telehealth making up over 70% of appointments.

And yet the story isn’t the numbers. The story is what it took to get there—and what happened when the easy part (growing fast) ended.

LifeStance is private equity ambition colliding with a very real societal need. It’s a roll-up strategy applied to a human-intensive service where the key constraint isn’t capital or software—it’s clinicians. It’s a company that rode a historic surge in demand during COVID, went public into peak optimism, and then watched its stock collapse as investors realized that scale is not the same thing as profitability.

So how did a 2017 roll-up become a publicly traded behavioral health giant? And in a system where access is broken, reimbursement is messy, and supply is limited, can LifeStance actually deliver on its promise—while still producing sustainable returns?

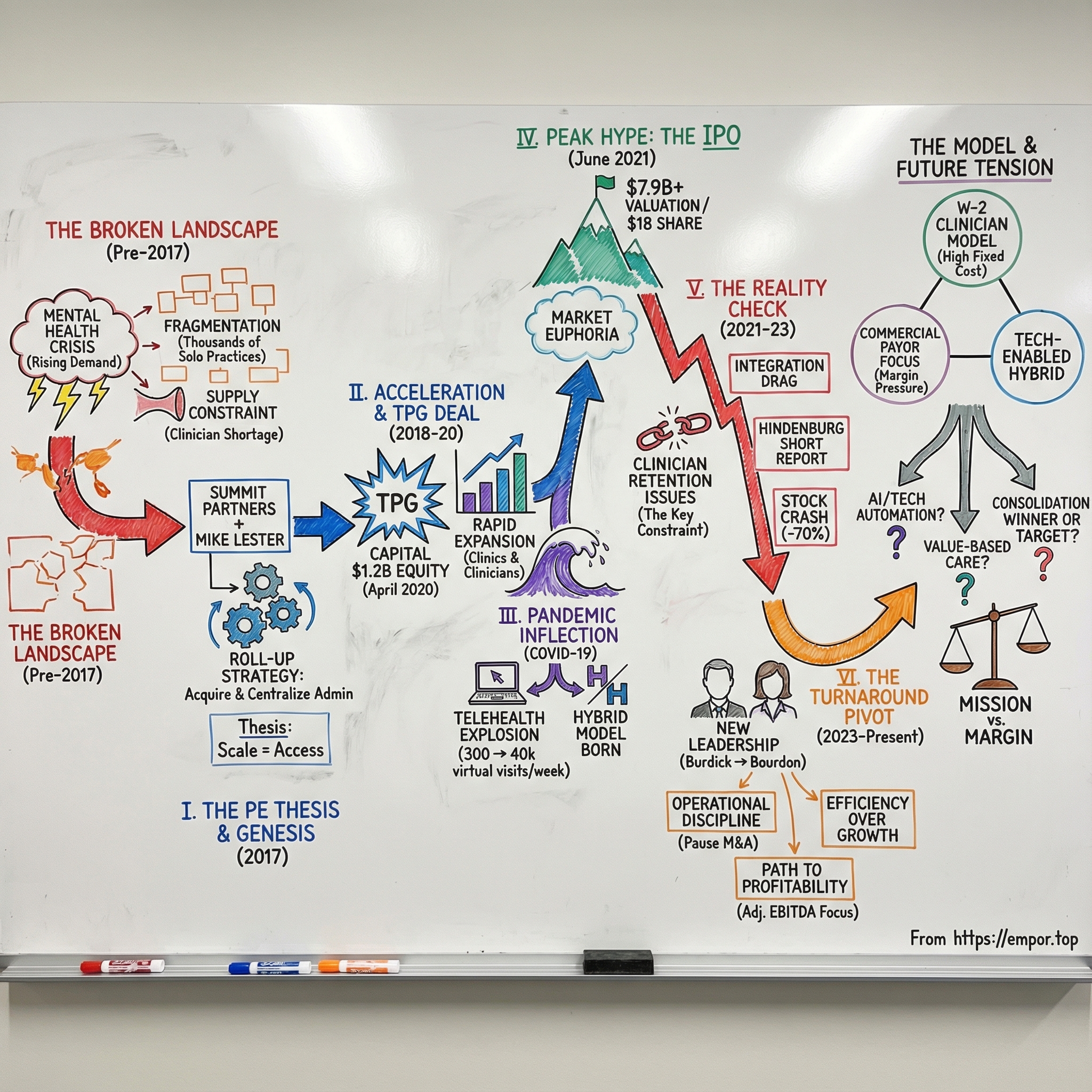

That’s what this episode is about: healthcare consolidation, the limits of the private equity playbook in services businesses that run on people, and the constant tension between mission and margin in American healthcare. We’ll follow LifeStance from a Summit Partners thesis to acquisition-fueled expansion, through the TPG Capital deal, the pandemic demand shock, a high-profile IPO, the post-IPO reality check, and the turnaround attempt that followed.

II. The Broken Mental Healthcare System: Setting the Stage

To understand why LifeStance existed at all, you have to understand the system it walked into. America’s mental health crisis wasn’t new in 2017. What was new was how visible it had become—and how impossible it felt to navigate.

By November 2024, nearly 59 million Americans—close to a quarter of the country—were living with mental illness. Almost half received no treatment. Not because they didn’t want help, but because they couldn’t get in the door.

The bottleneck starts with a simple supply problem. By December 2023, more than 169 million people lived in a Mental Health Professional Shortage Area. Zoom in and it gets worse: in 2018, more than half of U.S. counties didn’t have a single practicing psychiatrist. Even when care exists, it’s often clustered in affluent metro areas, leaving huge swaths of the country functionally stranded.

And this is happening inside a very large, very real market. The U.S. behavioral health market was valued at $87.82 billion in 2024 and was expected to keep growing in the years ahead. That number isn’t abstract. It’s what you get when mental illness touches almost every family—directly, or through someone they love.

So why didn’t this industry consolidate the way so many other parts of healthcare did?

Start with stigma. For decades, mental health stayed hidden, which meant it stayed underfunded. Then layer on economics: insurance reimbursement for mental health has long been weak and complicated, pushing many psychiatrists and therapists to opt out of insurance altogether and focus on cash-pay patients who could afford it. Add the messy reality of behavioral health delivery—different provider types, different rules, inconsistent scope of practice, rising burnout—and you end up with a workforce that’s stretched thin even before demand spikes.

The result is a market built out of small islands. Tens of thousands of solo practitioners and tiny group practices, each one running its own billing, credentialing, scheduling, and marketing. Patients feel this fragmentation immediately: finding someone who takes your insurance, is accepting new patients, and is actually a fit can take weeks of calls. Clinicians feel it too: a meaningful chunk of the behavioral health workforce reported spending most of their time on administrative work, and most providers said that admin load directly stole time they could have spent with patients.

Then COVID hit—and whatever was fragile snapped.

The pandemic didn’t invent anxiety, depression, and addiction. But it supercharged them. Isolation, grief, financial stress, and burnout sent demand through the roof, right as the system’s pre-existing problems—limited access and not enough providers—became impossible to ignore.

This was the landscape Michael Lester and his backers looked at in 2017: a huge, underserved market, split into thousands of small operators, with structural barriers keeping care out of reach. Their bet was straightforward in theory: consolidate the chaos, build infrastructure, and unlock access at scale. The hard part was that in mental healthcare, scale isn’t just a business problem.

It’s a people problem.

III. Origins & The Roll-Up Genesis (2017–2018)

LifeStance didn’t begin with a new therapy modality or a breakthrough piece of software. It began the way a lot of modern healthcare platforms begin: with a conviction that a broken, fragmented market could be stitched together—and that the stitching itself would create value.

In 2017, Summit Partners teamed up with founder Mike Lester, the LifeStance leadership team, and co-investor Silversmith Partners around a clear idea: build a national outpatient behavioral health platform that could meet rising demand and make care easier to access. Lester wasn’t an untested founder, either. Summit’s Darren Black framed the bet plainly: “This management team has a history of building industry-leading, clinically focused platforms in the healthcare services arena. As an investor in Mike’s prior company, I could not be more confident in his leadership capabilities.”

The thesis was simple and, on paper, persuasive. Behavioral health was huge and growing, but still run largely by small practices. Clinicians were drowning in admin. Insurance contracting rewarded scale. Better technology could tighten operations. And patients—millions of them—couldn’t find help at all. LifeStance planned to fund the push with as much as $250 million of equity, using a mix of acquisitions and new, “de novo” clinic openings to expand.

What they were building wasn’t just a bigger therapy practice. LifeStance aimed to assemble a multi-disciplinary care model under one roof: psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, psychologists, and licensed therapists offering outpatient treatment both in-person and via telehealth. That mattered because mental healthcare is often a team sport. In a single organization, a patient could get medication management from a psychiatrist and ongoing therapy from a counselor, with coordination that’s hard to achieve when care is scattered across independent offices.

Then came the roll-up playbook. LifeStance would buy established local groups with strong reputations and stable clinician teams. The clinicians were the asset; everything else was meant to become infrastructure. LifeStance would take over billing, credentialing, payer contracting, scheduling, marketing, and IT—so clinicians could spend more time with patients and less time fighting with paperwork. Summit and Silversmith backed that plan with $250 million, giving LifeStance the firepower to start buying and building quickly.

The early acquisitions read like a map of reputable community practices: PsychBC in Ohio, Georgia Behavioral Health Professionals in Georgia, Pacific Coast Psychiatric Associates in California, Child & Family Psychological Services in Massachusetts, and many more brands across the country—local names that patients already trusted.

For clinicians, the pitch was direct: keep your clinical autonomy, keep your patients, and let LifeStance handle the business headaches. In return, you’d get better systems, stronger contracting leverage with insurers, and a broader peer group to collaborate with. And LifeStance positioned itself as different from traditional employment in large health systems—more clinician-first and less driven by production-line pressure.

It worked—fast. In 2018, LifeStance recorded about 930,000 patient visits across 125 centers with 800 clinicians. By 2019, it was up to roughly 1.4 million visits, 170 centers, and 1,400 clinicians. The machine was on, and the pace would stay aggressive—nearly 100 acquisitions across the company’s first six years.

This was private equity’s classic healthcare services strategy playing out in real time: buy a fragmented market, centralize the back office, negotiate better reimbursement through scale, and grow by both acquiring and hiring. The open question was the one that would define LifeStance’s next chapter: in a field built on trust and human relationships, would this kind of industrial consolidation work as cleanly as it had in dental, dermatology, or physical therapy?

IV. Rapid Expansion & The TPG Deal (2018–2020)

By 2020, LifeStance was no longer a scrappy roll-up stitching together local practices. It had become a real national platform—and that meant the next step was almost inevitable. If you wanted to keep buying, keep opening clinics, keep hiring clinicians, and build the infrastructure to run all of it, you needed bigger capital.

That capital arrived in April 2020. TPG Capital agreed to invest $1.2 billion in LifeStance, joining Summit Partners and Silversmith Capital Partners. And they didn’t just dabble. TPG underwrote the deal entirely in equity—at the exact moment most investors were slamming on the brakes.

The timing was wild. This was April 2020: COVID-19 had just shut down the American economy. Dealmaking across industries froze. But TPG leaned in on behavioral health just as the country was about to discover, in real time, what mass anxiety, isolation, grief, and burnout looked like.

On May 14, 2020, TPG affiliates acquired a majority equity interest in LifeStance Health Holdings, Inc. Up to that point, the business had been conducted through LifeStance Health, LLC and its subsidiaries and affiliated practices. In the context of the market, the transaction was enormous: the $1.2 billion investment represented the vast majority of behavioral health deal value for the first half of 2020.

Both sides framed the partnership in mission-first language—access, quality, and scale. TPG Partner Jeff Rhodes pointed to LifeStance’s clinicians and leadership delivering “high-quality care” to a growing patient base. Summit’s Darren Black highlighted how quickly the platform had come together: in three years, LifeStance had built a national footprint designed to deliver convenient outpatient behavioral health services.

But the business logic was straightforward: this deal bought LifeStance time and ammunition. More acquisitions. More de novo openings. More hiring. More investment in the systems that make a multi-state clinician network actually function.

CEO Michael Lester put it plainly: the partnership with TPG, Summit, and Silversmith would drive the next phase of growth, expanding LifeStance’s geographic reach and its digital health footprint—so it could serve more patients nationwide.

The scale was already showing up in the operating numbers. In 2020, LifeStance handled approximately 2.3 million patient visits across in-person and online care—about double the volume from two years earlier. It had expanded to 370 centers and more than 3,000 clinicians. The platform had gone from “being built” to “ready to be stressed.”

And the whole strategy still hinged on one thing: clinicians. No clinicians, no company. LifeStance kept leaning into a specific pitch in a world full of 1099 platforms and solo-practice burnout: W-2 employment, benefits like healthcare coverage and retirement plans, and support for continuing education—plus relief from the endless admin drag of running your own practice.

What no one could fully see in April 2020 was how quickly demand for mental healthcare was about to surge—and how perfectly this moment would test, and reward, a scaled platform built for hybrid care.

V. COVID-19: The Inflection Point (2020–2021)

When COVID-19 arrived, it didn’t just strain America’s mental health system. It exposed it.

Isolation. Fear. Economic whiplash. Political turmoil. Grief that came in waves. Demand for help surged, fast—and at the exact same time, the old way of delivering care (an office, a waiting room, a commute) stopped working.

Telehealth went from “nice to have” to the default overnight. And in behavioral health, that shift mattered even more than in most specialties. If you can talk to a therapist from your bedroom, you don’t need to find a clinic across town, navigate childcare, or worry about being seen walking into an office. Geography fades. Stigma fades. Friction fades.

LifeStance, almost by accident of timing and design, was built for that moment.

As the pandemic hit, LifeStance’s virtual psychiatry volume exploded—from about 300 telepsych visits a week to more than 40,000. In other words: what had been a rounding error suddenly became the core of the business. And because LifeStance already operated as a hybrid platform—with centralized scheduling, billing, and multi-state operations—it didn’t have to invent a telehealth system under pressure. It had to scale one.

“LifeStance has been on the same growth trajectory, pre-COVID, during COVID and post-COVID,” said Danish Qureshi, co-founder and Chief Growth Officer. “What’s unique about our model is that we are delivering a hybrid care model that is agnostic of whether services are delivered in person or through telemedicine. We have built a platform that allows patients to seek care in whatever setting is most comfortable to them and that helps to lower the barrier to care.”

But this wasn’t a free lunch. The same wave that pulled more patients toward care also tightened the single biggest constraint in the entire industry: clinicians.

Everyone needed more therapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists at the same time. The shortage intensified. And suddenly, every mental health company—new and old—was battling for the same limited supply of talent.

That battle produced a new competitive map almost overnight.

On one end were the consumer-facing, pure-play digital brands like Talkspace and BetterHelp, which captured huge attention as the world moved online. On another were the “infrastructure for independents” platforms—Headway, founded in 2019, and Alma, founded in 2018—which helped clinicians stay independent while taking insurance and offloading billing and admin. By this period, Headway worked with about 34,000 providers, and Alma listed about 21,000 providers in its directory. And then there was the employer route: companies like Spring Health, backed by more than a billion dollars in venture funding, selling mental health benefits directly to employers.

LifeStance’s bet was that it could thread the needle between those models. Not just virtual care. Not just back-office tooling. A scaled clinical organization that could do both in-person and telehealth, employ clinicians directly, and still operate largely in-network with commercial insurance—so patients could actually afford to use it.

The growth showed up quickly. On a pro forma basis, revenue climbed from $100.3 million in 2018 to $212.5 million in 2019, then to $377.2 million in 2020.

By early 2021, the trajectory was pointing in one direction. TPG, Summit, and Silversmith had a fast-growing platform in a category with once-in-a-generation tailwinds, and the public markets were rewarding healthcare stories—especially ones that blended access, scale, and a COVID-era technology shift.

So the question became simple: would Wall Street buy the vision, too?

VI. Going Public: The IPO (June 2021)

By mid-2021, the market was in full-blown SPAC fever. LifeStance went the other direction. It chose the old-school route: a traditional IPO, with the kind of underwriting lineup that signaled, “we want real institutional buyers, and we think we can stand up to scrutiny.”

LifeStance Health Group, Inc., one of the largest outpatient mental health providers in the U.S., priced its offering at $18.00 per share, selling 40,000,000 shares and raising $720 million.

That $18 price mattered. The company had initially marketed the deal at $15 to $17, but demand was strong enough to push the final price above the range. Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan, and Jefferies led a 12-bank syndicate—Wall Street’s A-team—turning the offering into a high-profile test of whether public investors would buy the roll-up-plus-telehealth story.

On day one, they did. The stock jumped, trading around $25.34 shortly after debut—about a 40% pop. Within two weeks, it was up 57% from the IPO price, and the implied valuation had stretched from nearly $7.9 billion to $10.6 billion.

The pitch was tailor-made for that moment. Mental health need was accelerating, stigma was receding, and care was shifting online. LifeStance told investors the market opportunity was enormous—and expanding quickly—driven by rising incidence, growing awareness and acceptance, improved access, and regulatory support.

But the real bull case wasn’t just demand. It was the claim that LifeStance had found a scalable way to unlock supply.

Management drew a sharp distinction: the issue wasn’t a shortage of clinicians, it was a shortage of clinicians willing to accept commercial insurance. LifeStance argued that its scale let it change that equation. CEO Mike Lester highlighted the reimbursement leverage: before joining the platform, insurers paid the company’s providers about 85% of Medicare rates; after joining, that rose to 125% of Medicare. In other words, LifeStance wasn’t only filling schedules—it was improving the economics per visit through contracting power.

The company also emphasized repeatability. On acquisitions, LifeStance said it typically fully integrated acquired practices into its operational and technology systems within four to six months. On new (“de novo”) centers, it said clinics generally broke even within a few months, paid back invested capital in just over a year, and reached a two-times return on invested capital within 18 months on a center margin basis.

There was one more detail in the fine print that mattered later: control. After the IPO, affiliates of TPG Global, Summit Partners, and Silversmith Capital Partners still held a majority of the voting power. LifeStance was a “controlled company” under Nasdaq governance standards—meaning the public would own shares, but the sponsors still steered the ship.

In the summer of 2021, though, none of that felt like a risk. It felt like a coronation: a company founded in 2017, now newly public, priced above the range, and briefly worth close to eight figures in billions.

But public markets don’t just reward growth stories. They interrogate them—quarter after quarter. And LifeStance was about to learn how quickly a great narrative can collide with the hard math of labor, reimbursement, and integration at scale.

VII. Public Company Challenges & Recalibration (2021–2023)

Within months of the IPO, the LifeStance narrative started to crack. The stock that had traded above $25 in the first burst of post-IPO excitement began a long slide—one that eventually wiped out more than 70% of its value.

The first real jolt came with LifeStance’s first quarterly earnings report as a public company. At the time of the June 2021 IPO, the company said it retained 87% of its clinicians—about 13% churn. Just two months later, it delivered a brutal surprise: a net loss nearly double what analysts expected and a revised view of retention that it described as “consistent with the broader healthcare industry,” which it had previously defined as 77% retention, or 23% churn. The market didn’t debate the nuance. The stock dropped 46% that day.

Retention wasn’t a side metric. It was the business model.

In outpatient mental health, clinicians are the product, the capacity, and the relationship. If they walk, the revenue walks with them. Replacing them isn’t like swapping out sales reps. Recruiting is slow, credentialing is tedious, and rebuilding a caseload means starting trust from scratch—patient by patient. So if churn was higher than investors thought, then the unit economics behind the entire roll-up thesis suddenly looked far less stable.

That scrutiny turned into legal risk. LifeStance came under pressure over its clinician retention disclosures, and a judge in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York approved a deal in which LifeStance agreed to pay $50 million to resolve a lawsuit alleging it misled investors about retention ahead of the June 2021 IPO.

And retention was only one of the problems hitting at once. As the world emerged from the peak-pandemic phase, telehealth utilization began to normalize, taking some of the urgency—and some of the easy growth—out of the system. Integration got harder as LifeStance tried to standardize operations across nearly 100 acquired practices. Payors, always watching costs, kept pushing back on reimbursement.

The financials reflected the strain. LifeStance said it employed 7,400 licensed mental health clinicians as of 2024. In 2023, it reported a $187 million net loss—an improvement of 12% versus 2022, but still deep in the red. That same year, it closed 82 clinics while opening 35, describing the move as a consolidation effort.

Then, in February 2024, activist short-seller Hindenburg Research escalated the storyline with a report that pulled no punches. “Overall, we think LifeStance is a classic example of what happens when private equity meets a ‘hot’ healthcare sector: Massive debt fueling a grinding, metric-focused corporate culture resulting in worse quality of care for patients, a worse environment for clinicians and long-term losses for the average investor,” Hindenburg wrote.

Hindenburg also challenged LifeStance’s repeated claims that retention had stabilized. After the IPO fallout, LifeStance reported or confirmed on seven different investor-facing calls and conference appearances between 2022 and 2023 that its clinician retention rate was steady at 80%. Hindenburg said it scraped the LifeStance website and found that between August 15, 2023 and January 15, 2024, about 11.5% of providers listed in the company directory had disappeared—implying an annualized retention rate closer to 72%, below what management had been saying and, in Hindenburg’s framing, below the industry average.

LifeStance disputed Hindenburg’s methodology and characterizations. But the point wasn’t just who won the argument. The damage was that the market was reliving the same fear that hit right after the IPO: if you can’t trust the retention story, you can’t trust the growth story.

Leadership changes followed. In September 2022, LifeStance’s Board appointed Ken Burdick as Chief Executive Officer and Chairman, succeeding founder Michael Lester, who had led the company as CEO and Chairman since 2017.

Burdick brought a very different profile. He previously served as CEO of UnitedHealthcare and sits on several healthcare company boards. The appointment signaled an intentional shift: less startup roll-up energy, more operational discipline and public-company governance.

Under Burdick, LifeStance began pulling back. The Scottsdale, Arizona-based provider continued to abstain from M&A, opened fewer de novo clinics, and pushed a series of business optimization efforts. “We have steadied the ship, but we have not yet come close to optimizing the potential of our business,” Burdick said.

It was a dramatic pivot—from growth-at-all-costs to efficiency and a credible path to profitability. M&A, the engine that had built LifeStance’s footprint, was paused. Underperforming locations were closed. The new focus became “growing into the footprint”: filling the centers it already had with more clinicians, more patient visits, and better execution—because on public markets, growth is only half the story. The other half is whether it actually works.

VIII. The Turnaround Attempt & Current Strategy (2023–Present)

Under Ken Burdick, LifeStance set out to run a different kind of playbook than the one that got it to the IPO. The goal shifted from winning the land grab to proving the model could throw off cash. That meant a multi-year turnaround with a few clear levers: get more capacity and consistency out of the clinician base, tighten and rationalize the center footprint, improve the economics of insurance reimbursement, and cut corporate overhead that had ballooned during hypergrowth.

By the end of 2024, the turnaround started to show up in the results. Fourth quarter revenue was $325.5 million, up 16% year-over-year, and full-year revenue reached $1,251.0 million, up 19% from $1,055.7 million. The clinician base grew 12% to 7,424 clinicians. Burdick called it out on the company’s results: “The team delivered exceptional performance in 2024. We grew revenue 19%, more than doubled Adjusted EBITDA, and generated strong Free Cash Flow of $86 million.”

The bottom line was still not pretty in GAAP terms, but it was moving in the right direction. LifeStance reported a net loss of $7.1 million in the fourth quarter and $57.4 million for the year. At the same time, adjusted EBITDA rose 62% to $32.8 million in the quarter and more than doubled to $119.7 million for the full year. The message to investors was simple: the company might not be profitable yet, but the engine was finally being tuned to get there.

Then came another leadership handoff. In February 2025, LifeStance announced that its Board appointed Dave Bourdon as Chief Executive Officer. Bourdon had joined LifeStance as CFO in 2022 and succeeded Burdick, who retired as CEO and moved into the role of Executive Chairman.

Bourdon wasn’t an outsider brought in to “fix” the business; he was the finance-and-operations leader who had been inside the turnaround while it was happening. He also brought deep behavioral health and payer experience, having previously served as CFO of Magellan Health and held multiple positions at Cigna.

In the third quarter of 2025, LifeStance reported that momentum continued. Revenue was $363.8 million, up 16% from $312.7 million a year earlier. The clinician base rose 11% to 7,996 clinicians, and visit volume increased 17% to 2.3 million. The company reported net income of $1.1 million, compared with a net loss of $6.0 million in the prior-year quarter. For full-year 2025, LifeStance reiterated revenue expectations of $1.41 billion to $1.43 billion and raised its adjusted EBITDA outlook to $146 million to $152 million.

LifeStance also described Q3 2025 as its second profitable quarter as a public company—an important psychological milestone after years of telling investors profitability was “coming.” Management attributed the improvement to higher clinician productivity, lower general and administrative expense, and continued net clinician hiring.

Bourdon framed it as an execution story. “This was a quarter of records for LifeStance,” he said. “In the third quarter, we achieved the largest improvement of quarterly organic productivity in our company’s history.” The company pointed to specific initiatives behind that push: cash incentives to encourage clinicians to open up more availability, a new patient engagement platform, technology upgrades to support call-center scheduling, and AI-automated clinician documentation.

With the model looking steadier, LifeStance started talking about growth again—but in a more controlled tone. The company signaled it could return to M&A, positioning acquisitions as additive rather than existential. “We’re being very thoughtful and disciplined,” Bourdon said. “The primary purpose of these acquisitions is for geographic expansion, so establishing beachheads and new MSAs or states. We feel really good about M&A being complementary to our organic growth. Organic growth is still going to be the primary driver in the coming years.”

Looking ahead, LifeStance said it anticipated mid-teens revenue growth in 2026 with an emphasis on margin expansion. It planned to open 20–25 new centers in 2025 and said it was targeting 15–20% margins in future years. Bourdon also put a stake in the ground on profitability: “Furthermore, we believe that in 2026 we will achieve positive net income and earnings per share for the full year. This is a key milestone in our journey as a public company.”

IX. The Business Model Deep Dive

To understand LifeStance, you have to follow the money—and in mental healthcare, the money almost always flows through insurance.

At a high level, the model is simple: a patient sees a LifeStance clinician, and LifeStance bills the insurer, mostly commercial plans, for the visit. That mix matters. LifeStance’s payor mix was heavily weighted toward commercial insurance—about 91% commercial, 5% government, and 3% self-pay. That reliance isn’t accidental. Commercial reimbursement is generally richer than Medicare or Medicaid, and in a labor-heavy business, those rates can be the difference between “scales nicely” and “never makes money.”

The other defining choice is how LifeStance staffs the business. LifeStance employs most of its clinicians as W-2 employees rather than just building a network of independents. Compared to platforms like Headway or Alma—where clinicians keep their own practices and the platform handles the administrative layer—LifeStance is running an actual clinical organization. That means higher fixed costs, but also more control over the levers that matter: scheduling, capacity, productivity, and a more consistent patient experience.

Then there’s the mix of who those clinicians are. In 2021, the company last disclosed that about two-thirds of its clinicians were therapists. Therapists are essential to the mission and often the volume driver, but from a business standpoint, psychiatry tends to carry higher reimbursement, especially for medication management. By 2024, Hindenburg’s analysis suggested that the mix had tilted further toward therapy—about 79% therapists. Whether you view that as a clinical inevitability or an economic headwind, the implication is the same: the more your organization is weighted toward longer, lower-reimbursed therapy sessions, the harder it can be to expand margins.

One advantage LifeStance points to versus some direct-to-consumer telehealth brands is patient acquisition. Because LifeStance clinicians are in-network with major insurers, many patients find them through insurance directories or referrals from primary care doctors, instead of being “bought” through paid marketing. That’s a big contrast with consumer digital mental health companies that often spend aggressively to generate demand.

In theory, scale should compound the benefits. A large network can sometimes negotiate better rates with payors, especially in markets where access is constrained and insurers need reliable in-network capacity. Centralized billing, credentialing, and technology should spread fixed costs over a bigger base. And offering multiple modalities—therapy, psychiatry, and other outpatient services—should make it easier to retain patients within the system over time.

LifeStance has also shown it can use scale to simplify. In 2022, it had more than 400 payer contracts, but half of those contracts accounted for only 5.7% of patient visits. Cutting back on low-volume contracts reduced administrative burden with minimal revenue impact—exactly the kind of unglamorous operational move that matters when the story shifts from growth to profitability.

But the scale thesis runs into the reality that has defined LifeStance from the beginning: healthcare doesn’t scale like software. Every incremental visit requires clinician time. And clinicians have options. They can switch platforms, go independent, or cut back hours if the work doesn’t feel sustainable.

Which is why the whole model keeps circling back to one metric: retention. Bourdon said one region was running at 87% clinician retention, with the company targeting the mid- to high-80% range—yet that region was the only one hitting the goal. “We’ve just got to get the other ones up to that similar level,” he said. “As we think about the future, we still believe that we can move the needle on clinician retention.”

X. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

If you want to stress-test LifeStance’s story, there are two lenses that matter. First: what does the industry structure do to you? That’s Porter’s 5 Forces. Second: even if the market is attractive, do you have anything that lasts? That’s Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers.

Porter's 5 Forces

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH

Behavioral health has a weird split personality on barriers to entry. At the low end, it’s almost frictionless: one licensed clinician can hang a shingle and start seeing patients. But at the high end—the part LifeStance is trying to own—building a national, multi-state platform is hard. It takes capital, systems, contracting expertise, and years of integration work.

The bigger risk is that the capital is there for everyone. With venture money and private equity pouring into mental health—funding players like Headway, Alma, and Spring Health—“finding funding” isn’t the moat. The race is whether LifeStance can widen its operational lead faster than competitors can assemble similar infrastructure.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Clinicians): HIGH

This is the force that sits on top of everything else. SAMHSA has projected that by 2025 the U.S. will be short roughly 31,000 full-time equivalent mental health practitioners. In a shortage, clinicians are the scarce resource—and scarce resources have leverage.

They can choose LifeStance, choose a competitor, go independent with support from platforms like Headway, or simply work fewer hours. That means LifeStance has to keep re-earning its workforce every year through pay, culture, clinical support, and day-to-day experience. If retention slips, growth slows no matter how strong patient demand is.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Patients/Payors): MODERATE

On the patient side, there’s real stickiness once care begins. Therapeutic relationships are hard to replace, and many patients won’t shop around once they’ve found a clinician they trust.

But the other buyer—the one that really matters economically—is the insurance company. LifeStance is built around in-network reimbursement, and nearly all revenue flows through payer arrangements. That gives insurers meaningful power over rates. And when costs in the world rise faster than reimbursement, the math gets tight fast. LifeStance has pointed out that total revenue per patient visit increased only 2% to $157 even as inflation ran hot—a dynamic that has pressured margins across behavioral health.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

Patients have choices, and those choices keep expanding.

On one end are pure-play telehealth platforms that emphasize convenience and lower price points—BetterHelp and Talkspace are the obvious examples. Then there are the infrastructure players that help clinicians take insurance and stay independent: Headway, Alma, Grow, and SonderMind. Add in digital therapeutics, AI-assisted tools, and traditional health systems investing more heavily in behavioral health, and you get a crowded substitute set.

The core question is whether patients—and payors—value LifeStance’s in-network, hybrid, multi-disciplinary model enough to choose it over simpler, cheaper, or more flexible alternatives.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Even after years of consolidation, the market is still crowded. PE-backed roll-ups like Thriveworks, Mindpath, and Refresh Mental Health run similar playbooks. Tech platforms like Talkspace and Cerebral compete for demand. Infrastructure networks like Headway compete for supply. Hospital systems keep building more behavioral health capacity.

And underneath all of it is the same knife fight: everyone is recruiting from the same constrained clinician pool.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

Scale Economies: DEVELOPING

LifeStance does get real benefits from spreading fixed infrastructure across a large clinician base: EMR, billing, credentialing, scheduling, compliance, and corporate functions. Size can also help in payer negotiations.

But there’s a ceiling. The largest cost in the system—clinician compensation—doesn’t magically get cheaper as you grow. This is not software. The scale advantage exists, but it’s not unlimited.

Network Effects: WEAK-MODERATE

In theory, more clinicians means more availability, which attracts more patients. More patients can generate more data to improve matching and outcomes measurement.

In practice, the network effect is muted. A patient in Chicago doesn’t get much benefit from LifeStance adding clinicians in Phoenix. The platform dynamics are there, but they’re not the kind that lock a market the way true marketplaces do.

Counter-Positioning: LIMITED

LifeStance isn’t winning because it has a model incumbents can’t copy. It’s mostly doing aggregation and operational build-out in a fragmented space. Competitors—especially well-funded ones—can pursue similar consolidation strategies.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

For patients, switching costs can be high because the relationship is the care. Starting over with a new therapist is emotionally taxing and often clinically disruptive.

But the switching cost attaches more to the clinician than to LifeStance. If a clinician leaves, patients often follow. That makes retention not just an operating metric, but a competitive defense mechanism.

Branding: DEVELOPING

LifeStance is not a household name. In many markets, it competes against local practice reputations on one side and heavily marketed national brands like BetterHelp on the other. There’s room to build trust, but it isn’t an established advantage yet.

Cornered Resource: WEAK

LifeStance doesn’t control an exclusive input. It doesn’t have privileged access to clinicians, and it doesn’t own proprietary treatment methods that competitors can’t replicate. In this business, the critical scarce resource is talent—and it is not cornered.

Process Power: DEVELOPING

If LifeStance is going to build something durable, this is the best candidate. The company has been assembling a repeatable operating system: integrating practices, enabling clinicians with technology, improving scheduling and productivity, and reducing administrative friction. As it leans further into tech enablement—using AI and digital tools to automate processes, improve accuracy, and support clinicians—process power is where a real edge could compound.

Overall Assessment: LifeStance is operating in a large, growing market with genuine societal tailwinds. But it doesn’t have a strong moat today. The outcome hinges on execution: whether it can turn scale into better economics and a better clinician experience—fast enough to outrun competitors, and consistently enough to solve the retention challenge that’s shadowed the company since the IPO.

XI. The Competitive Landscape & Market Dynamics

LifeStance operates in a market where competitors aren’t coming from one direction—they’re coming from all of them at once. Some are fighting for patients. Others are fighting for clinicians. And a few are trying to own the entire funnel, from insurance contract to appointment to outcomes.

Traditional Competitors

Most mental healthcare in the U.S. still happens the old-fashioned way: solo practitioners and small group practices. That fragmentation is exactly what makes LifeStance’s consolidation thesis possible—but it’s also what makes competition stubborn. Many local practices have deep community reputations and referral relationships that don’t show up on a spreadsheet.

Hospital systems are another force. More of them have been pulling behavioral health into broader care models, especially as value-based care pushes providers to treat mental health as inseparable from physical health. For a patient already in a health system’s orbit, getting therapy “inside the system” can be the path of least resistance.

PE-Backed Roll-Ups

LifeStance isn’t the only one who saw a fragmented market and smelled opportunity. Thriveworks, Mindpath, and Refresh Mental Health have all pursued roll-up strategies, each with its own footprint and operating style. The important shift is that the private equity playbook is no longer a differentiator. It’s table stakes. And when multiple well-capitalized platforms are buying practices and recruiting from the same talent pool, the battle becomes less about who can acquire and more about who can execute after the acquisition closes.

Tech Platforms

In the last five years, tech-enabled mental health platforms have expanded fast, fueled by the pandemic-era telehealth boom, the grinding reality of insurance, and enormous amounts of venture funding chasing a big, emotionally resonant category.

But “tech” is not one category here—it’s several. Talkspace and BetterHelp go straight to consumers with marketing and convenience. Headway and Alma go after the clinician by offering the back-office infrastructure that lets therapists stay independent while still taking insurance. Spring Health and Lyra go through employers, winning distribution by becoming a benefit.

Each of these models is making a different bet on where the real leverage lives: the patient relationship, the clinician relationship, or the payor/employer relationship.

Health System Integration

Then there are the giants. Optum, through UnitedHealth Group’s care delivery footprint, has every incentive in the world to keep behavioral health inside its own ecosystem. Kaiser Permanente has long treated mental health as part of integrated care. These players already have massive patient bases and embedded payor relationships, which means they can compete on access and economics in ways smaller platforms can’t always match.

Why Hasn't Anyone Dominated?

If mental health is such a huge market opportunity, why hasn’t one winner emerged?

Because the barriers aren’t just financial—they’re human and structural. Clinicians often value autonomy and can be wary of corporate models. Healthcare is deeply local, built on trust and referral patterns. Insurance contracting is complicated and varies by region. And the hard ceiling over everything is supply: there simply aren’t enough clinicians, and no amount of capital can manufacture them on demand.

That combination keeps the market fragmented—and keeps any would-be national leader, including LifeStance, constantly fighting on multiple fronts.

XII. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

LifeStance’s arc—from private equity roll-up to pandemic rocket ship to public-market gut check—leaves a trail of lessons that apply far beyond behavioral health.

The Healthcare Roll-Up Playbook Has Limits

Roll-ups work when centralizing the back office actually improves unit economics without breaking the service. In sectors like dental, optometry, and physical therapy, a lot of the work is standardized, and patients don’t usually form a deep, identity-level bond with the provider brand.

Mental health is different. The therapeutic relationship is the product. If clinicians feel monitored, rushed, or treated like interchangeable capacity, they leave. And when they leave, patients often follow. In this category, integration risk isn’t a spreadsheet risk—it’s a people risk.

Timing IPOs: LifeStance Caught the Top

LifeStance went public in June 2021, right when enthusiasm for mental health and telehealth was peaking. It raised a lot of capital at a valuation that assumed the best version of the story would keep playing out.

But public markets don’t let you live off a narrative. They reprice you every quarter. As soon as retention, margins, and integration started looking messier than the early pitch, the stock didn’t just drift down—it got reset. The takeaway for any company eyeing an IPO is uncomfortable but real: make sure the market’s expectations are durable, not just a moment of euphoria.

When to Consolidate Fragmented Markets (And When Not To)

Fragmentation is an invitation to consolidate only if a few conditions hold: scale creates real cost or pricing advantages, the customer relationship transfers cleanly after acquisition, and the critical inputs can be standardized and replicated.

Mental healthcare only partially fits. Scale can help with contracting, recruiting infrastructure, and administrative efficiency. But relationship transfer is fragile, because patients aren’t loyal to a logo—they’re loyal to a clinician. And the most important “resource” in the business isn’t technology or equipment. It’s human beings with licenses, choices, and burnout thresholds. They can’t be owned, and they can’t be forced to stay.

The Human Capital Challenge

Healthcare services are people businesses in the purest sense: labor is the main cost and also the main value. That means the classic private equity toolkit—standardization, productivity pushes, cost discipline—has to be handled with surgical care. In behavioral health, the clinical workload is rising in intensity, and the backlog of patients, especially younger ones, keeps growing. If you don’t invest in recruiting, support, and retention, you don’t have a growth engine. You have a churn machine.

Unit Economics Matter

Public markets will tolerate losses for growth—until they won’t. LifeStance scaled quickly, but the losses and questions about how profitable the model could become eventually forced a reset. The post-IPO era made the priorities unavoidable: improve margins, generate free cash flow, and prove the unit economics hold up at scale.

The broader lesson is simple: growth is exciting, but in healthcare services, the math always catches up.

XIII. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Perspective

Bull Case

LifeStance sits in the middle of a huge market with powerful tailwinds. Awareness keeps rising, stigma keeps falling, and policy has generally moved in the direction of expanding access. The CDC’s 2022 data shows the share of adults receiving mental health treatment rising from 19.2% in 2019 to 21.6% in 2021—small on paper, meaningful at a national scale. And the cultural direction, especially among younger generations, has been unmistakable: getting help is becoming normal.

The industry’s fragmentation still creates a real consolidation opening. Outpatient behavioral health remains a patchwork of local groups and solo practices. If someone is going to build a truly national platform—with consistent access, in-network coverage, and the operational backbone to support thousands of clinicians—LifeStance is already out in front. In theory, its scale in insurance contracting, technology, and operating playbooks should get more valuable with time, not less.

And importantly, the turnaround has started to look real. In 2024, adjusted EBITDA more than doubled to $119.7 million, about 9.6% of revenue. Management’s 2025 outlook implied another step forward, with adjusted EBITDA growth projected in the high single digits to the mid-20s range. If LifeStance can do what it’s been signaling—reach full-year positive net income in 2026—that’s not just a financial milestone. It’s proof the model can work.

Then there’s the valuation reset. The stock has been punished so severely since the IPO that expectations are no longer heroic. Someone who put $1,000 into LifeStance at the June 2021 IPO would be sitting at roughly $300 today. If the company keeps executing—retaining clinicians, improving margins, and growing into its footprint—there’s meaningful upside simply from the gap between “broken story” and “working business.”

Bear Case

Clinician retention is still the existential risk. LifeStance can optimize scheduling, upgrade technology, renegotiate payor contracts—all of it—but if clinicians don’t want to stay, the flywheel breaks. And this is where the company’s history gives skeptics plenty of ammunition. Lawsuit allegations and former-employee accounts have described a workplace where compensation expectations don’t match reality, where clinicians can end up financially “trapped,” and where corporate pressure makes the job less sustainable. In a profession where the barrier to going independent can be relatively low, dissatisfaction can translate into exits quickly.

Competition also isn’t letting up. Tech-enabled platforms can offer clinicians flexibility without traditional employment. Health systems can steer patients internally. PE-backed roll-ups can copy the same consolidation playbook. In other words: LifeStance may have a head start, but the race is crowded—and the scarce resource everyone is chasing is the same limited clinician pool.

Payor dynamics are another structural headwind. Insurers are sophisticated, cost-focused buyers. They push back on rates, they shape networks, and they influence what “access” looks like in practice. Reimbursement is also uneven in ways that don’t naturally pull providers into rural or underserved areas. Even with scale, LifeStance can’t simply dictate the economics of insurance-driven care.

Finally, the profitability story is not finished. Results have improved, but net losses have persisted, and the accumulated deficit has continued to build since the IPO. If margin expansion stalls—or if clinician costs rise faster than revenue per visit—LifeStance could end up back in the familiar place of needing more capital just to keep momentum.

Key Metrics to Watch

For investors tracking LifeStance, three KPIs matter most:

-

Clinician Retention Rate: This is the single most important metric. Without clinicians, there is no business. Management targets mid- to high-80% retention. Watch for any deterioration from current levels.

-

Revenue Per Visit: This metric captures both reimbursement rate trends and service mix evolution. Growing revenue per visit indicates pricing power and operational efficiency. Declining revenue per visit signals payor pressure or unfavorable mix shift.

-

Adjusted EBITDA Margin: Track the trajectory toward the company’s 15–20% long-term margin target. Margin expansion suggests operational leverage is finally showing up; margin compression suggests the model may not scale as profitably as hoped.

XIV. Epilogue: The Future of Mental Healthcare

As 2025 draws to a close, LifeStance sits at a familiar kind of crossroads—just with higher stakes than before. The turnaround under Ken Burdick helped steady the business after the post-IPO spiral. Now the question is whether Dave Bourdon can do the harder thing: turn stabilization into a durable operating model that can grow without breaking.

Bourdon has been blunt about where he thinks the leverage is. “We are a heavily manual business… There is a lot of opportunity for us to implement technology, digital AI-type tools,” he said, pointing to a company still doing too much work the hard way. He’s also clear about why the fight matters: there is, in his words, “significant unmet need in society today for mental health services.” Demand isn’t the debate. Delivery is.

That’s where the next wave—especially AI—could change the shape of the industry. AI isn’t likely to replace human therapists for complex care. But it can absolutely change the workload around care: automating documentation, reducing scheduling friction, improving patient engagement, and freeing clinicians to spend more time in sessions instead of in software. LifeStance is investing in that future. Of course, so is everyone else with capital and ambition in this space.

Then there’s value-based care: paying for outcomes instead of volume. In theory, LifeStance should be built for this. Scale creates data, data enables measurement, and measurement is what payors say they want. In practice, behavioral health outcomes are notoriously hard to quantify, contracts are hard to structure, and taking risk can punish operators that don’t execute flawlessly. The opportunity is real—but so is the danger.

At the same time, integrated care—the merging of mental and physical health—keeps accelerating. Primary care providers are screening more. Payors are pushing for coordination. And the winners will likely be the organizations that can plug into broader care ecosystems rather than living as a separate, siloed specialty. That makes LifeStance’s ability to partner with health systems and primary care practices more than a business development initiative. It may determine whether it stays central—or gets routed around.

So what does LifeStance look like in five years? There are a few paths that feel genuinely plausible:

Successful Consolidator: The turnaround sticks, clinician retention holds in the mid-80s, margins keep expanding, and LifeStance becomes the category-defining national outpatient mental health platform—something akin to what DaVita became in dialysis.

Acquisition Target: A major health system or diversified healthcare player acquires LifeStance for its infrastructure, clinician network, and patient relationships, the way large systems have historically absorbed physician practice groups.

Cautionary Tale: Clinician retention remains the unsolved constraint, margin targets never materialize, and the private-equity roll-up thesis proves far harder to translate into a lasting advantage in a relationship-driven, labor-limited business.

The mental health crisis is real, and it isn’t easing up. The need for accessible, affordable, high-quality care is urgent. LifeStance’s bet was that scale, technology, and operational discipline could widen access without sacrificing quality. Whether that bet can produce a business that’s both mission-driven and sustainably profitable remains the central question.

For investors, LifeStance is a classic turnaround setup: a company that overpromised in a euphoric market, absorbed a painful reset, and is now showing signs of operational recovery. The valuation still carries a lot of skepticism about whether the model can truly work long-term. If management delivers, the upside is meaningful. If it doesn’t, the same structural forces—labor scarcity, reimbursement pressure, and relentless competition—are still waiting.

In the end, the LifeStance story is bigger than one company. It’s a test of whether American healthcare can scale care for the underserved while generating sustainable returns. It’s the tension between mission and margin, between efficiency and humanity, between what public markets demand and what patients need. And for now, the ending isn’t written yet.

XV. Further Reading & Resources

Essential Primary Sources:

-

LifeStance Health IPO Prospectus (S-1 Filing, 2021): Start here. It’s the cleanest snapshot of what LifeStance promised public investors at the moment the story went mainstream—its thesis, its risk factors, and how management framed the opportunity.

-

LifeStance Quarterly Earnings Releases and Investor Presentations (2021-2025): The quarter-by-quarter record of how the strategy evolved in real time: what changed, what didn’t, and how leadership explained the tradeoffs between growth, retention, and profitability.

-

Hindenburg Research Report on LifeStance (February 2024): A sharp, skeptical read on clinician retention and operating realities. Even if you disagree with the conclusions, it’s useful for understanding the most pointed bear case and why the market reacted the way it did.

Industry Context:

-

HRSA Behavioral Health Workforce Brief (2023): A grounded view of the clinician shortage from the government’s perspective—helpful for separating company-specific execution issues from structural labor constraints.

-

Commonwealth Fund: "Understanding the U.S. Behavioral Health Workforce Shortage": A clear breakdown of why access is so constrained, and why “just hire more clinicians” is not a simple answer.

-

PwC Health Research Institute Reports on Behavioral Health M&A: A window into the deal environment around LifeStance—what consolidation looked like across the sector, how capital flowed, and how valuations shifted.

Competitive Landscape:

-

Headway, Alma, and Grow Therapy company materials: Useful for seeing the “infrastructure” model up close—how platforms try to win clinicians without employing them, and why that threatens the roll-up approach.

-

Talkspace and BetterHelp SEC filings and investor materials: The best way to compare LifeStance’s hybrid, insurance-heavy model with the pure-play digital approach—and understand what each is optimizing for.

Books for Broader Context:

-

"An American Sickness" by Elisabeth Rosenthal: A sobering, highly readable tour of American healthcare incentives—the backdrop that makes a story like LifeStance feel inevitable.

-

"The Innovator's Prescription" by Clayton Christensen: A framework for thinking about what true healthcare disruption looks like, and where scale-and-roll-up strategies can create value—or hit a wall.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music