Leggett & Platt: The Hidden Giant Behind Your Mattress (and Everything Else)

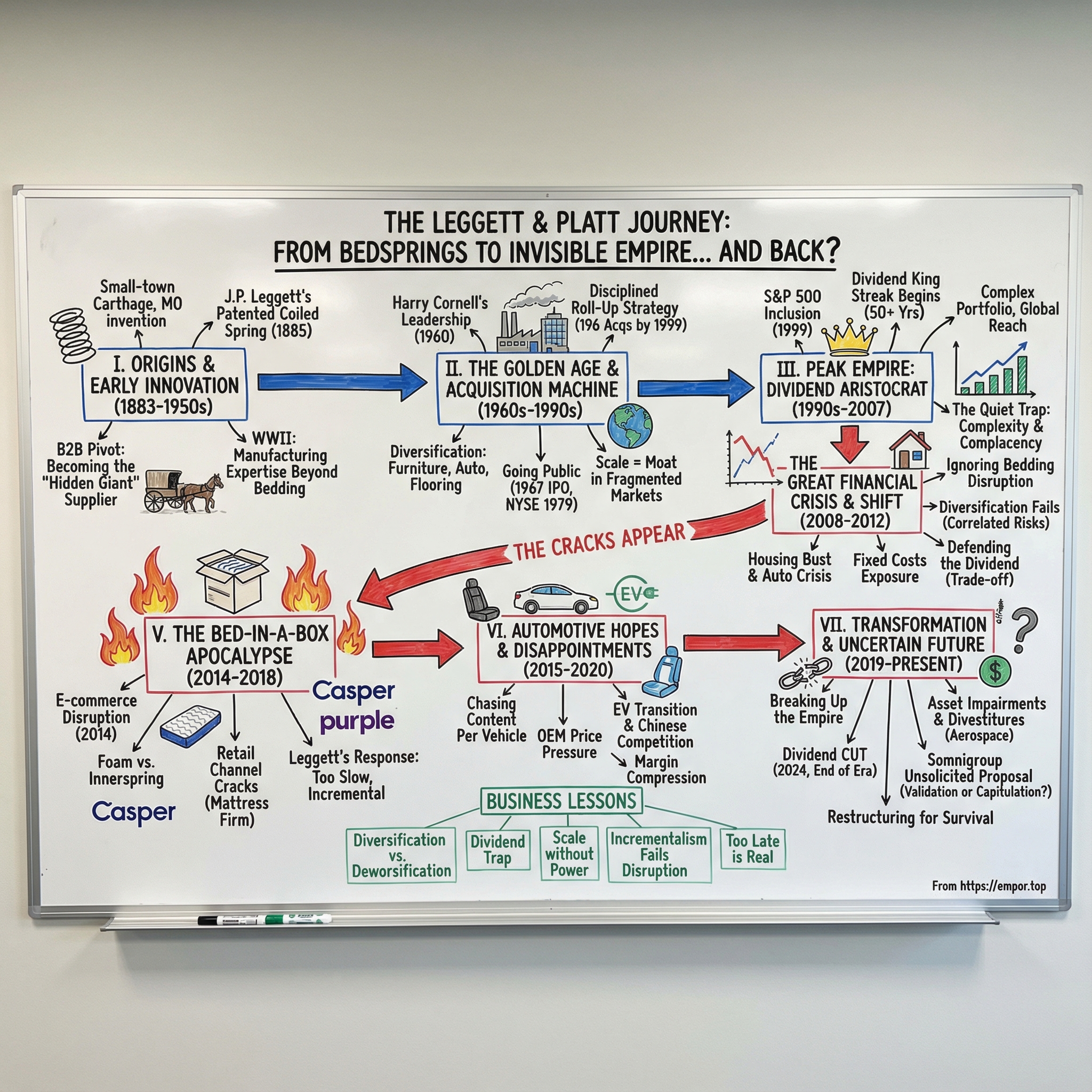

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: you wake up tomorrow, pour your morning coffee, and drop into your office chair. Later, you’ll drive home in your car, and at the end of the day you’ll collapse onto your mattress—maybe even hit a button and let an adjustable base do the rest. In all of those ordinary moments, there’s a very real chance you’re relying on parts made by a 142-year-old company you’ve probably never heard of: Leggett & Platt.

Leggett & Platt is based in Carthage, Missouri. It was founded in 1883, and it makes the engineered components that hide inside other people’s products—furniture, bedding, automotive seating, and more. Today it operates across 15 business units, employs roughly 20,000 employee-partners, and runs 135 manufacturing facilities in 18 countries.

For decades, this was the kind of company Wall Street loves: steady, diversified, and invisible. It generated more than four billion dollars in annual revenue year after year. It built one of the longest dividend growth streaks in American corporate history. And it became a behind-the-scenes supplier to entire industries most consumers never think about—because the point was that you didn’t have to.

But if you bought the stock at the 2007 peak and held on, it hasn’t been “boring and predictable.” It’s been dead money at best, and worse at times. The shares fell hard, the celebrated dividend streak finally broke in 2024, and now the company is fighting for its next chapter—so much so that it’s even drawn an unsolicited acquisition proposal from Somnigroup, the newly formed bedding conglomerate that owns Tempur Sealy and Mattress Firm.

So that’s the question we’re going to chase: how did a 19th-century bedspring innovator turn itself into a sprawling industrial conglomerate—and why is it now shrinking, selling pieces, and restructuring just to stay standing?

Along the way, we’ll hit some timeless business lessons: how roll-up strategies can create real advantage in fragmented markets… until they don’t. How diversification can quietly turn into “deworsification.” How protecting a dividend streak can become a strategy unto itself—and a trap. And how Leggett & Platt once played the “Intel Inside” role for bedding, until the bed-in-a-box revolution made its core technology feel less essential.

By the end, the story isn’t just how this empire got built. It’s whether it can be rebuilt—leaner, more focused, and competitive again—or whether Leggett & Platt’s most valuable future really does belong inside someone else’s.

II. The Founding Era & Early Innovation

In 1883, in the small town of Carthage, Missouri, a tinkerer named Joseph P. Leggett landed on an idea that sounds almost obvious now, but at the time was a genuine upgrade to everyday life: a bedspring made from single-cone wire coils, formed and interlaced, then mounted on a wooden slat base.

It’s hard to overstate what came before. Most American beds were essentially a mattress stuffed with cotton, feathers, or horsehair laid directly on a frame. They sagged. They clumped. They offered whatever “support” the stuffing happened to provide.

Leggett’s coiled spring created something new: a resilient foundation underneath the mattress. Suddenly, the bed wasn’t just a bag of filling—it had structure.

Leggett knew the invention was one thing; producing it at scale was another. So he pulled in his soon-to-be brother-in-law, Cornelius B. Platt, a blacksmith who ran the C.D. Platt Plow Works in Carthage. Platt agreed to help manufacture the springs, and in 1883 the two formed a partnership, using the Platt Plow Works as the production site for the first Leggett bedsprings. They built them with belt-driven machinery in borrowed space, the kind of early industrial setup that ran as much on grit as it did on engineering.

Their go-to-market strategy was just as scrappy. To reach customers outside Carthage, Platt and George Leggett—J.P.’s brother—would load a horse-drawn wagon with bedsprings and head to nearby towns. And because a fully assembled bedspring takes up a lot of room, they often transported the springs and slats separately, then put them together right there in the store—or on the sidewalk out front.

In 1885, Leggett received a patent for improvements to the coiled bedspring. The business took off. The company built its first factory and offices in Carthage in 1890. At that point, the “workforce” was simply the two partners and five employees. The partnership incorporated in 1901, and not long after finishing the Carthage plant, the company opened a second factory in Louisville, Kentucky.

What’s striking about the first half-century of Leggett & Platt is how focused it stayed. Despite offering different models and steadily improving them, bedsprings were essentially the only product the company sold until 1933. That year brought a pivotal expansion: Leggett & Platt began making springs for innerspring mattresses, a relatively new category that was quickly catching on.

That move did more than add a product line—it changed the company’s identity. Over time, Leggett & Platt made a defining pivot in how it operated: instead of selling to retailers, it increasingly sold to other manufacturers. In other words, it stopped trying to be a brand and became a supplier. That B2B posture—quietly powering someone else’s finished product—would define the next century.

Then came World War II. In 1942, Leggett & Platt began manufacturing bedsprings for military use. The war years proved something important: the company’s expertise in wire and spring manufacturing wasn’t limited to civilian bedrooms. It could be redirected wherever durability and repeatable manufacturing mattered, a lesson that would shape everything that came after.

The DNA was set early: technical know-how in springs and wire products, an obsession with making things efficiently, and deepening relationships with industrial customers. Leggett & Platt was becoming the invisible partner behind the visible product—essential, but rarely named.

III. The Golden Age: Going Public & The Acquisition Machine (1960s-1990s)

The modern era of Leggett & Platt really began in 1960, when a 32-year-old grandson of the founder took the wheel.

Harry Cornell had joined the company in 1950 on the sales side and steadily climbed the ladder until he became president and CEO in 1960. Over the decades that followed, he oversaw a transformation that’s hard to wrap your head around: what started as a small, regional manufacturer with five plants and about $7 million in annual sales grew into a global components powerhouse—eventually reaching roughly $4 billion in revenue, with operations spread across about 18 countries.

Cornell was third-generation family leadership, but he didn’t run the company like a caretaker. He pushed a clear strategy: broaden the mix of component products for bedding and furniture, expand geographically, and offer compatible products directly to furniture stores. In other words, don’t just be the bedspring company. Be the company that quietly makes the critical parts across the whole room.

And Cornell had a leadership style people remembered. Former employees tell stories of him showing up unannounced—introducing himself, checking on a project, asking how things were going. It was personal, unpretentious, and it helped build loyalty.

But that folksy style sat on top of something else entirely: a disciplined acquisition engine.

By the time Cornell stepped down as CEO in 1999, Leggett & Platt had become a sprawling portfolio of businesses—nearly 200 factories across 18 countries, producing a wide range of products used throughout the home, the office, and increasingly, the automobile. Along the way, the company completed 196 acquisitions, using them to move into new geographies, new product categories, and deeper vertical integration.

Going public in 1967 poured fuel on that fire. Leggett & Platt’s IPO priced 50,000 shares at $10 each, trading over the counter at first. Then, in 1979, the stock graduated to the New York Stock Exchange—an arrival moment for a company that had spent most of its life far from Wall Street.

The acquisition playbook was simple and repeatable: find adjacent, often family-owned component manufacturers; buy them at reasonable prices; fold them into Leggett’s distribution and customer relationships; and squeeze out scale efficiencies. Cornell also leaned into a uniquely Leggett idea that went all the way back to the early days: don’t just make the parts—make the machines that make the parts, and, where it made sense, make the raw materials too. The more of the stack you controlled, the more reliable your costs, quality, and delivery became.

This is also where Leggett started to feel less like a single business and more like an industrial toolkit. Through the 1970s and 1980s, diversification accelerated. The company moved into steel motion hardware for home furniture—mechanisms that make upholstered seating rock, recline, and swivel. It began drawing steel wire primarily for internal use. In 1986, it entered Flooring Products. In 1988, it entered Automotive by producing seating components.

By 1985—when the company was 102 years old—Leggett & Platt made Fortune’s list of the 500 largest industrial companies in the United States. And in 1990, powered by years of acquisitions and expansion, it crossed the $1 billion sales mark.

Cornell didn’t just buy businesses; he built a culture that could absorb them. The organization was deliberately decentralized. Business unit leaders ran with real autonomy, which kept decision-making close to customers and operations. In a pre-internet world—where relationships were local, distribution was physical, and manufacturing know-how mattered—this structure worked beautifully. Being big and diversified wasn’t a handicap. It was a real advantage, because most customers were fragmented and most competitors were small.

Then came the international push. In 1999 alone, Leggett & Platt acquired 29 international companies, including deals in Australia, Brazil, and Italy. By the end of that year, acquisitions helped land the company in the S&P 500 Index—another milestone that signaled just how far the Carthage bedspring business had traveled.

For investors, it looked like a machine built for perpetual motion: acquire, integrate, optimize, repeat. The dividend climbed year after year. The stock split multiple times. Leggett & Platt had become the kind of steady compounder that made long-term shareholders feel smart without ever having to brag about it at a dinner party.

The big takeaway from this era is that, in fragmented industrial markets—before e-commerce and before globalization rewired supply chains—being a diversified scale player with deep customer relationships really could function like a moat. The twist is that moats don’t disappear all at once.

They erode. Quietly. And then suddenly.

IV. Peak Empire: Becoming a Dividend Aristocrat (1990s-2007)

By the late 1990s and into the early 2000s, Leggett & Platt looked unstoppable. The acquisition machine kept humming, the dividend kept rising, and Wall Street had a clean, comforting narrative to tell: this was a steady, diversified industrial that quietly sat inside the American economy.

By the early 2000s, the company had done more than 200 acquisitions and stitched together an almost comically broad catalog of components: innersprings and box springs, the machinery that made them, furniture mechanisms, carpet cushion, store fixtures, wire products, and a growing pile of automotive seating parts—seat mechanisms, lumbar support systems, control cables, and more. Leggett liked to say its products were in virtually every American home and automobile. And in a sense, that was the whole point: they weren’t the brand you shopped for. They were the parts your favorite brands couldn’t ship without.

Automotive, in particular, started to feel like the next great pillar. The bet was straightforward: cars were getting more comfortable and more feature-rich. Power adjustments, ergonomics, and “comfort systems” weren’t luxuries anymore—they were becoming standard. If content per vehicle was going up, then being deeply embedded in Detroit’s supply chain looked like a durable growth lane.

International expansion followed the same playbook that had worked at home. Leggett spread manufacturing across Europe and Asia so it could serve global OEMs with local production. From the outside, it looked like smart risk management: diversification not just across products, but across geographies too. Protection against any single downturn.

In 1999, the company’s entry into the S&P 500 made it official. Leggett & Platt wasn’t just a successful roll-up anymore. It was a blue-chip.

And then there was the dividend. Starting in the early 1970s, Leggett raised its dividend every year—year after year, quarter after quarter—until the streak became more than a shareholder return policy. It became the brand. Eventually, that record would stretch to 52 consecutive years of increases, earning “Dividend King” status and placing Leggett in an elite club that income investors treated like royalty.

For the right kind of shareholder, it was irresistible: a sprawling but stable industrial, throwing off cash, tied to housing and consumer spending, with a side of automotive growth—and a dividend that felt as dependable as gravity. The story the market bought was simple: boring, predictable, diversified, moated.

But the cracks were already forming.

The portfolio had grown so wide that complexity became its own tax. With more than a hundred business units, overhead and coordination costs piled up. Plenty of categories were too small to ever be truly advantaged. Innovation slowed—not because the company couldn’t innovate, but because buying growth was easier than building it. Meanwhile, customer concentration crept higher as retailers and manufacturers consolidated, and price pressure intensified as Chinese competitors entered more of Leggett’s product lines.

Most of all, almost no one was asking the dangerous question: what if the core bedding ecosystem—the one Leggett was built around—didn’t stay the same forever? For generations, the industry’s rhythm was predictable. Manufacturers bought components from suppliers like Leggett, assembled mattresses, and sold them through brick-and-mortar retailers. It had always worked that way.

So why would it ever change?

That was the quiet trap of the era. The dividend kept climbing, the empire kept expanding, and “good enough” returns made it easy to ignore the fact that the underlying business was becoming more fragile with every passing year.

V. The Great Financial Crisis & The Cracks Appear (2008-2012)

When Lehman Brothers collapsed in September 2008, Leggett & Platt learned the hard way that “diversification” is only comforting when your businesses don’t all depend on the same underlying engine.

Leggett’s biggest segment was Residential Furnishings, and Residential Furnishings ultimately rides on housing. When the housing bubble burst, consumers slammed the brakes on big-ticket purchases. Mattress demand fell off a cliff—because when people are worried about losing their homes, they don’t upgrade what’s inside them. Furniture followed right behind.

And the part of the portfolio that was supposed to balance it out didn’t. Automotive was staring into its own abyss as Detroit’s Big Three teetered toward bankruptcy. Instead of one segment cushioning another, Leggett found itself exposed to the same downturn from multiple angles, all at once.

That’s when the roll-up era’s hidden weakness became visible: fixed costs. Plants that looked “efficient” in good times suddenly had excess capacity everywhere. Revenue dropped, margins tightened, and the company’s scale started to feel less like a moat and more like a weight.

So management did what industrial companies do in a crisis. They closed plants. Cut headcount. Pulled every cost lever they could reach. But one decision mattered more than the rest, because it wasn’t operational—it was cultural.

The dividend.

By this point, the annual dividend increase wasn’t just a shareholder return policy. It was identity. A signal to the market that Leggett was steady, disciplined, and safe. Plenty of investors owned the stock for that reason alone. Cutting it would’ve been admitting, out loud, that the story had changed.

So the company kept paying it—barely. And in doing so, it locked itself into a tradeoff that would define the next decade: cash that could have strengthened the balance sheet or been reinvested into the business instead went out the door to protect a streak.

The crisis also exposed problems that had been building quietly even before the economy cracked. Customer concentration was real: the top ten customers made up more than 30% of revenue. Many product lines were increasingly commoditized, which meant buyers could pit suppliers against each other and win on price. “Market leadership” didn’t translate into pricing power, and margins showed it. Worse, private equity started buying up Leggett’s customers—turning relationship-driven accounts into spreadsheet-driven negotiators who pushed relentlessly on terms.

When the economy stabilized, Leggett stabilized too—but not like before. The recovery lagged, pressure on margins lingered, and the easy wins from acquisition-fueled growth weren’t there anymore. The stock clawed back some ground, but it never regained the pre-crisis confidence.

And while management spent these years fighting yesterday’s fire, the next one was already starting—inside the mattress industry itself. That disruption wouldn’t look like a recession. It would look like a new business model. And it would hit far closer to home.

VI. The Bed-in-a-Box Apocalypse (2014-2018)

In 2014, the mattress industry got its iPhone moment. Casper launched that April and made a simple pitch feel radical: instead of wandering into a fluorescent showroom and negotiating with a salesperson, you could buy a mattress online, have it show up at your door in a box, and test-drive it for 100 nights.

The trick wasn’t magic marketing. It was logistics. New compression and roll-packing equipment made it possible to take a foam mattress, shrink it into a shippable package, and hand delivery to common carriers and last‑mile partners. Once that constraint disappeared, the whole industry’s distribution model—built around stores, trucks, and floor inventory—suddenly looked optional.

Casper didn’t do it alone. Co-founder Philip Krim, working with Jeff Chapin (who’d helped big brands think about product design at IDEO) and other partners, built the model around cutting out retail overhead and going direct. And once it worked, it didn’t stay a one-off. A flood followed. Purple, Tuft & Needle, Leesa, GhostBed, Helix Sleep, and a long tail of copycats piled in. At one point, more than 170 bed-in-a-box brands were chasing the U.S. mattress market.

For Leggett & Platt, this wasn’t just “new competition.” It attacked the heart of their value chain.

Leggett supplied innerspring components to the traditional mattress manufacturers—Sealy, Serta, Simmons—who, in turn, relied heavily on brick-and-mortar retail. Bed-in-a-box flipped that: many of the new entrants sold all-foam mattresses, and the hybrids they did sell often reduced the role of traditional innersprings. Springs weren’t merely bypassed; they were positioned as yesterday’s technology. Foam was framed as modern, engineered, and superior. Innersprings were what your grandparents slept on.

Then the channel started cracking. In 2018, Mattress Firm—the largest mattress retailer in the U.S.—filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Its massive store footprint was a relic of an earlier era, when mattress retail was local, price competition was limited, and “more stores” looked like an advantage. But as online brands sold mattresses with fewer markups and more convenience, the pricing umbrella collapsed. Mattress Firm’s problems were partly self-inflicted, but the signal was unmistakable: the traditional ecosystem was in trouble.

And Mattress Firm wasn’t just any retailer in Leggett’s orbit. It was a critical route to market for Leggett’s biggest bedding customers. When the retailer faltered, the pressure didn’t stop at the storefront. It rolled backward through manufacturers and straight into the component suppliers.

Leggett’s response was careful—arguably too careful. The company tried to follow the market toward foam and hybrids. It explored partnerships with direct-to-consumer brands, but those relationships didn’t meaningfully scale. And internally, management faced the innovator’s dilemma in its purest form: moving aggressively into the new architecture risked cannibalizing the high-margin innerspring business that still paid the bills.

So the shift happened around them, not with them. Residential Furnishings—once the dependable growth engine—began to slide. Share eroded. The technology that had once been differentiated became, in more and more situations, a “good enough” input—especially as customers consolidated and gained leverage.

Why didn’t Leggett see it coming fast enough? Because the company’s greatest historical strength had quietly turned into a liability. Customer intimacy had become customer dependence. Leggett was so tied to the incumbents that it inherited their assumptions—and their blind spots. Decades of acquisition-led growth had also dulled the urgency to invent the future internally. And the commitment to keep the dividend climbing siphoned away flexibility right when flexibility mattered most.

By the time the disruption was undeniable, Leggett wasn’t choosing between two growth paths. It was choosing between defending the old world and trying to buy its way into the new one—late, and under pressure.

VII. Automotive Hopes & Disappointments (2015-2020)

As bedding started to wobble, management needed a new pillar. Automotive became the obvious candidate—the segment they could point to on earnings calls and say, “This is the future.”

On paper, it made sense. Cars were getting more feature-rich and comfort-obsessed. More power adjustments. More ergonomics. More “content per vehicle.” And Leggett had the right kind of product portfolio for that world: seating actuators, lumbar support systems, control cables, and the hidden mechanisms that turn a basic seat into something that feels premium.

They didn’t just talk about it—they doubled down. A string of acquisitions added capabilities in seating components, deepened relationships with OEMs, and expanded the company’s footprint in the supply chain. The narrative was clear: if mattresses were becoming a battleground, maybe cars could be the steady growth lane.

But automotive is a different animal. It’s one of the most unforgiving procurement environments in the economy. OEMs like GM, Ford, and FCA were famous for squeezing suppliers, and “give us a little price break every year” wasn’t a negotiation tactic—it was the starting point. At the same time, Chinese competitors showed up in the lower-tech parts of the market and put a ceiling on pricing. Even if Leggett had scale, it didn’t have leverage.

Then the ground shifted again. The rise of electric vehicles began challenging the assumptions behind the whole strategy. Tesla and other EV makers approached vehicle design differently—simplified interiors, different seating structures, and a willingness to rethink the supplier stack. New players started winning share, and the old comfort-and-content playbook didn’t feel as guaranteed.

By 2019 and into 2020, the pressure showed up where it always does first: margins. Returns on the capital Leggett had put into automotive started raising uncomfortable questions. And then COVID hit, and automotive production halted for months. The “future growth engine” went from promising to exposed overnight.

By this point, a pattern was hard to ignore. Leggett kept chasing the next big thing, but it wasn’t set up to lead in categories that demanded real differentiation. It could buy capabilities through acquisitions, but acquisitions couldn’t manufacture a moat. So, again and again, it ended up playing the same game: competing on price in markets where buyers had the power—and where being a higher-cost domestic manufacturer was a structural disadvantage.

VIII. Private Equity, Consolidation & The Changing Competitive Landscape

While Leggett was dealing with disruption in bedding and disappointment in automotive, the ground under its entire business model was shifting. Quietly, but decisively.

Private equity swept through the bedding world. The big mattress manufacturers—Sealy, Serta, Simmons—passed through PE ownership and came out the other side with a very different posture toward suppliers. This wasn’t the old relationship-first industry anymore. These were consolidated, financially engineered buyers with professionalized procurement teams, benchmark spreadsheets, and one job: push costs down. The power dynamic flipped. Leggett used to be the indispensable component supplier to lots of fragmented customers. Now it was negotiating with fewer, larger, tougher counterparties.

And then there was the ever-present threat hanging over every supplier conversation: vertical integration.

Tempur Sealy was the clearest example. CEO Mark Sarvary explained the company’s thinking this way: “Our decision to exit the production of innerspring components in the U.S. will allow us to focus our investments on brand building and product innovation while improving our working capital position. Leggett & Platt is a well-established leader in the industry and our expanded relationship will provide significantly greater flexibility for our product development efforts.”

On the surface, that quote reads like validation. In practice, it captures the trap Leggett was in. In 2014, Tempur Sealy sold its U.S. innerspring production facilities to Leggett and signed a long-term supply agreement. But the relationship was never simple. Even when big customers outsourced, they still held a powerful negotiating weapon: the credible threat that they could bring production back in-house if the economics didn’t suit them.

Layer on top of that what people inside U.S. manufacturing often call the “China problem.” For a lot of the categories Leggett played in, Chinese manufacturers could produce similar, increasingly “good enough” components at a lower cost. Tariffs and anti-dumping cases offered some protection, and Leggett fought those battles—sometimes successfully. But winning in court didn’t erase the underlying reality: global competition was resetting price expectations, and Leggett was still getting squeezed.

So a strategic question started to hover over the whole era: should Leggett have moved up the stack? Should it have bought a mattress brand, a retailer, or otherwise integrated forward—rather than staying a pure component supplier?

There were real arguments against it: risk, complexity, and the capital required to compete in consumer-facing businesses. But the argument for it was brutal in its simplicity. Staying “in the middle”—not the low-cost producer, not meaningfully differentiated, and not vertically integrated—left Leggett exposed to exactly what it was experiencing: chronic margin compression.

By the end of the 2010s, the deterioration was hard to deny. Leggett still had scale. But scale without pricing power is a hollow advantage. Customers were bigger and more demanding. Products were more commoditized. The company’s core bedding technology was being displaced. And there was no obvious path to reclaim control of its destiny.

IX. The Transformation Plan: Breaking Up the Empire (2019-2024)

By the end of the 2010s, it was getting impossible to ignore: the old Leggett playbook wasn’t working anymore. The realization didn’t arrive with one clean turning point. It seeped in—quarter by quarter—until the company had no choice but to start pulling the empire apart.

The first real attempt at portfolio discipline actually dated back to 2007, in the aftermath of the financial crisis. Management introduced a framework that categorized businesses as “Grow,” “Core,” or “Fix,” with different expectations for each. They sold and shut down underperformers and, over time, cut out roughly $1.2 billion of revenue. They also set total shareholder return targets. And to reassure investors that everything was still under control, they raised the dividend by 39%.

But it was a reset without a reinvention.

The company pruned the worst performers, yet the deeper structural issues stayed in place. The acquisition muscle memory returned. The TSR targets quietly reinforced the idea that the dividend had to be defended at all costs. And, most damaging of all, Leggett hadn’t yet internalized what was coming for bedding.

That disconnect became impossible to hide in late 2023. In the fourth quarter, Leggett took a $450 million long-lived asset impairment charge tied to prior acquisitions in its Bedding Products segment. Management pointed directly to the real-world pain behind the accounting: prolonged weak demand, changing market dynamics, and customer instability. Some customers were actively trying to shore up their finances, and Leggett expected those efforts to translate into less future volume and lower earnings.

Read between the lines and the message was brutal: a major strategic bet hadn’t paid off.

That impairment was, in effect, the company admitting that the 2019 Elite Comfort Solutions deal—purchased for $1.25 billion in cash—had destroyed value. ECS was supposed to be the move that brought Leggett into the new bedding world: “proprietary foam technology,” more scale in private-label finished mattresses, and a platform to “capitalize on current and future market trends.” Instead, it became a write-down that symbolized how hard it is to buy your way into a disrupted market once you’re already late.

Then, in January 2024, Leggett finally went from adjusting around the edges to formally restructuring. The company announced a restructuring plan aimed primarily at Bedding Products, with smaller actions in Furniture, Flooring & Textile Products. The plan was expected to shrink annual sales by about $100 million, but also deliver an annualized $40 to $50 million of EBIT benefit once fully implemented in late 2025.

And in a telling move, Leggett also pulled back its promises. Alongside the restructuring plan, it withdrew its previously stated 11–14% total shareholder return goal and stepped away from a set of financial targets, including revenue growth, EBIT margin, and dividend payout ratio.

A few months later came the moment that, for many shareholders, made everything feel real.

Leggett & Platt had been a Dividend King—52 consecutive years of dividend increases. That streak ended in 2024 with an 89% dividend cut. The board declared a second-quarter dividend of $0.05 per share, down $0.41 from the prior year’s second quarter.

By then, the market had been screaming that something was wrong. The dividend yield had climbed above 10%, a level that usually isn’t a sign of generosity—it’s a distress flare. After the cut, the stock was down more than 63% for the year.

This wasn’t just a financial decision. It was an identity break. For decades, the dividend streak had been treated as proof that Leggett was stable and predictable. Ending it in one announcement told investors what management wouldn’t say quite so bluntly: the old version of Leggett & Platt was gone. Predictably, many income-focused institutions that owned the stock for the dividend sold. And management credibility—already strained by missed targets—took another hit.

Still, the company kept moving. Through 2024 and into 2025, Leggett pushed the restructuring forward and highlighted progress: $22 million of EBIT benefit in 2024, $20 million of cash proceeds from real estate sales, efforts to limit sales attrition, and tight control of restructuring costs. It also emphasized balance sheet repair, including $126 million of debt reduction during 2024.

Then came a divestiture that underscored how serious the reset had become. In August 2025, Leggett announced it had completed the sale of its Aerospace Products Group to affiliated funds managed by Tinicum Incorporated. The deal was expected to generate about $250 million of after-tax proceeds, with the cash used primarily to pay down debt and improve leverage.

Aerospace wasn’t just another business unit. Selling it marked a shift in posture: less empire-building, more survival math. It was part of a broader strategic review meant to narrow the company to businesses that actually fit its long-term direction. After years of incrementalism, Leggett & Platt was finally making the kind of painful, simplifying decisions that—depending on who you ask—either came just in time, or years too late.

X. The 2007 Restructuring: A Dress Rehearsal That Failed

In hindsight, the 2007 restructuring was Leggett & Platt’s first clear warning shot—and its first big missed chance to change the trajectory. Management could see the portfolio getting too sprawling. They knew some businesses weren’t pulling their weight. So they tried to bring order to the empire.

Out came the Grow/Core/Fix framework. Underperformers were divested. Expectations were differentiated. And to keep investors onside, the company paired the cleanup with ambitious total shareholder return targets.

For a while, it looked like it worked. EBIT margins improved. The dividend kept rising. From the outside, this read like a classic industrial reset: trim the dead weight, tighten the screws, and move on.

But the reset stopped short of the hard stuff.

Leggett didn’t truly reposition around what was coming in bedding—still its most important ecosystem. It held onto automotive even as returns were, at best, uncertain. And once the immediate pressure eased, the company slipped back into its most familiar habit: buying growth. The acquisition engine restarted before the underlying model was made resilient.

The TSR targets didn’t help. They quietly turned financial outcomes into the strategy. If the dividend streak had become the company’s pride, then those targets made it even harder to question whether the cash should be used differently. Cutting the dividend to fund transformation wasn’t just unpopular—it was culturally off-limits. So money kept flowing out to shareholders, instead of into building a stronger competitive position.

That choice mattered when the bed-in-a-box wave hit. Leggett was already late, and it was late with constraints: limited flexibility, a culture built for steady optimization, and a playbook that leaned on acquiring “innovation” rather than creating it. Incremental improvement was what Leggett did best. Radical repositioning was what the moment demanded.

The lesson is simple, and brutal: capital allocation discipline is harder than it looks—especially when a company’s identity gets tangled up in metrics like TSR targets and dividend streaks.

XI. The Dividend Decision: When Legacy Becomes Liability (2024)

The 52-year dividend growth streak had stopped being just a capital allocation choice. It was Leggett & Platt’s identity.

For decades, the company lived in a rarefied category: a Dividend King, one of the small handful of U.S. companies that had raised its dividend year after year for five straight decades. Income investors owned it for that reason. Some institutions even had mandates built around owning reliable dividend growers. The streak wasn’t just a perk. It was the product.

The problem was that, underneath the streak, the cash generation was getting shakier. The company’s cash flow had been persistently volatile, and that volatility showed up as growing balance sheet pressure. Free cash flow fell from over $602 million in 2020 to $497.2 million by 2023.

And the dividend wasn’t waiting patiently for the business to catch up. For years, Leggett kept paying—and raising—even when earnings couldn’t fully support it. On consensus estimates, the dividend payout ratio climbed to 131%. In plain English: Leggett was paying out more than it was earning. You can do that for a while. You can’t do it forever.

So in 2024, the company finally did the thing it had trained investors to believe it would never do. It cut the dividend, pointing to leverage, a tough economic climate, and a reset in priorities. Management framed the new agenda as “strengthening balance sheet and liquidity, improving margins by optimizing operations, and positioning for profitable growth opportunities.”

It was a psychological breaking point. Leggett wasn’t just trimming a payout. It was admitting that the old contract with shareholders had expired.

The aftermath was exactly what you’d expect: institutional selling, individual investor outrage, and a stock price collapse. But there’s a harder, more uncomfortable argument sitting underneath the wreckage: the cut was probably the right decision, made far too late.

Because by defending the streak for so long, management had boxed the company in. Cash that could have funded reinvention went out the door. Balance sheet flexibility that could have bought time and options got used to protect a headline. And when the cut finally came, it wasn’t a controlled reset. It was an emergency confession.

The irony is brutal. The dividend policy designed to reward loyal shareholders ended up punishing them far more than an earlier, smaller cut ever would have.

XII. Current State & Recent Moves (2024-2025)

By late 2025, Leggett & Platt was no longer the sprawling empire it had spent a century building. It was a company in transition—smaller, more focused, and finally taking real swings at cost and complexity. But it was still doing it against structural headwinds it didn’t fully control.

In its latest earnings report, Leggett & Platt posted third-quarter sales of $1.0 billion, down 6% from the same period the year before. Reported earnings per share were $0.91, while adjusted EPS came in at $0.29.

The restructuring was starting to show up in the places that matter. Year-to-date in 2025, the company delivered $36 million in incremental EBIT benefit, and it expected to land at roughly $40 million for the full year. Management also raised its view of what the program could ultimately produce: an annualized EBIT benefit of $60–$70 million once initiatives were fully implemented in late 2025, up from a prior estimate of $50–$60 million.

Cash was the other bright spot. Strong generation, plus proceeds from the aerospace divestiture, helped Leggett pay down debt and bring leverage down—moving from 3.83x in 2024 to 3.25x by 2025. It was the clearest sign that, after years of trying to optimize its way out of trouble, the company was now prioritizing balance sheet room to breathe.

The external environment, though, remained uneven. Tariffs were a tailwind in Rod & Wire, where domestic steel tariffs supported better metal margins. But in Adjustable Bed, the picture flipped: reliance on imported products from China created meaningful challenges.

For the full year, Leggett & Platt expected earnings of $1.00 to $1.10 per share, and revenue of $4.0 to $4.1 billion.

And then came the development that made the entire “turnaround as a standalone company” question feel suddenly less theoretical.

Somnigroup International Inc. announced it had submitted an unsolicited proposal to acquire all outstanding Leggett & Platt shares in an all-stock transaction. The headline term was simple: Leggett shareholders would receive Somnigroup common stock with a market value of $12.00 for every one Leggett share.

“Leggett & Platt has been an important supplier to our Company for many years,” said Scott Thompson, Chairman and CEO of Somnigroup. “This proposal would deliver significant value to Leggett & Platt shareholders through a compelling premium and tax-advantaged participation in our combined platform, while also being accretive before synergies to all Somnigroup shareholders.”

The proposal also came with plenty of qualifiers. Somnigroup said the exchange ratio was “to be agreed,” called the offer non-binding, and conditioned it on due diligence. It also noted that it hadn’t engaged with Leggett & Platt prior to November 30, 2025. Leggett’s board responded in the expected way: it said it would review and evaluate the proposal consistent with its fiduciary duties, in consultation with independent financial and legal advisors.

Stepping back, the Somnigroup offer—coming from the newly formed combination of Tempur Sealy and Mattress Firm—felt like both validation and capitulation at the same time. Validation that Leggett’s assets still matter strategically. Capitulation that, after a decade of disruption, consolidation, and margin pressure, being acquired might be the cleanest path forward.

XIII. Business Model & Strategic Analysis

For nearly a century, Leggett & Platt’s model was deceptively powerful: be the behind-the-scenes component supplier with real technical know-how, sell to lots of small, fragmented customers, and use acquisitions to build scale and a broader catalog. Because the organization was decentralized, business leaders could move fast and stay close to customers—while corporate supplied capital, distribution reach, and shared services.

Then that foundation started to crack, for a few reasons that hit all at once.

Customers consolidated. Private equity rolled up mattress manufacturers and retailers, turning relationship-driven accounts into bigger, tougher negotiators. Once your customer base shrinks, the math changes: they can pit suppliers against each other, and they can credibly threaten to bring production in-house.

Disruption hit the core market. Bed-in-a-box didn’t just change what people bought. It rewired the whole mattress value chain—compressing distribution, shifting product design toward foam and hybrids, and stripping out parts of the ecosystem where Leggett had historically been essential.

Complexity became a tax. The same sprawling portfolio that once looked like entrepreneurial energy started to behave like friction. Too many subscale operations. Too many duplicated functions. Too much management attention spread too thin. The overhead of “being everywhere” began eating the benefits of scale.

And despite the size, there wasn’t pricing power. “Market leadership” in a commoditized category often just means you’re the biggest participant in a price war. Scale can improve efficiency, but it can’t manufacture differentiation.

So what’s left of the value proposition?

Leggett still has meaningful scale in categories like springs and wire rod. Domestic manufacturing can be an advantage when tariffs tilt the playing field. Long-standing technical relationships with automotive and bedding OEMs still matter. And the private-label mattress capability it picked up through Elite Comfort Solutions is, at least in theory, a different model than being a pure component supplier.

But the bigger question is the one investors can’t avoid: is this still a “good business”?

That answer is uncomfortably mixed. Many of these markets have low barriers to entry. Pricing is often commodity-like. Customer concentration is still high. And it’s a capital-intensive company, in categories that have struggled to deliver attractive returns on invested capital. In other words, this looks less like a compounding machine—and more like the profile of a classic value trap.

XIV. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE

In some corners of Leggett’s world, it’s genuinely hard to show up overnight. Wire and rod production is capital-intensive, relationship-driven, and shaped by regulatory and quality constraints. But in foam and many furniture components, barriers are lower, differentiation is thinner, and overseas competition—especially from China—can enter with “good enough” products that hit the market fast. Automotive sits somewhere in between: testing and certification slow down would-be entrants, but they don’t eliminate the pressure entirely. Scale helps, but it’s not a locked gate.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MODERATE

Leggett buys into commodity markets. Steel prices move with global supply and demand, and Leggett has limited ability to dictate terms. Foam brings its own version of the same problem: chemical inputs are sourced from global suppliers with their own pricing power, and a few specialty materials have limited supply options. Net-net, Leggett is usually reacting to input costs, not controlling them.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

This is the force that defines the modern Leggett story. Private equity-backed mattress manufacturers negotiate like professionals, because they are. Automotive OEMs are famously relentless on price, terms, and annual “productivity” givebacks. Large retailers like Walmart and Amazon have the kind of leverage that turns suppliers into line items. And because the customer base is concentrated, losing one major account isn’t a setback—it can be a body blow. Add the constant threat of vertical integration from players like Tempur Sealy, and buyers don’t just have leverage; they have options.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

Leggett’s legacy strength—innersprings—has been steadily pressured by all-foam and hybrid mattresses. In automotive, traditional seating mechanisms run into a different design philosophy as EV makers rethink interiors and simplify architectures. Adjustable bases don’t exist in a vacuum either; they compete with smart beds and other alternative sleep products. And across categories, “good enough” imports create a substitute that’s less about technology and more about price.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Even where markets are fragmented, competition can be brutal because many product lines don’t offer much differentiation. Chinese manufacturers frequently compete on price with a lower-cost base. Private equity consolidation has also created bigger, better-capitalized rivals that can invest, cut costs, and fight for share. And in metal-related businesses, steel overcapacity can compress margins and keep the whole category in a grind.

Overall Assessment: This is a structurally tough setup. Leggett’s old advantages—scale, relationships, diversification—still exist, but they don’t translate into the kind of durable pricing power that makes a business great. It’s not an obviously broken company. But it’s operating in markets where the forces are stacked against easy, consistent value creation.

XV. Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework Analysis

Scale Economies: WEAK (formerly MODERATE)

Leggett has real scale in wire rod and spring manufacturing. The problem is that scale hasn’t shown up where shareholders want it to: in consistently better margins. In practice, the biggest customers negotiate away the benefits. The efficiency gains flow downstream, and Leggett is left carrying the fixed-cost base. And whatever leverage scale should provide often gets offset by the complexity tax of running a sprawling, diversified portfolio.

Verdict: scale without pricing power is a hollow advantage.

Network Effects: NONE

Leggett is a B2B component supplier. There’s no network dynamic here—no marketplace, no platform flywheel, no “winner-takes-most” loop.

Counter-Positioning: NONE

Leggett isn’t the disruptor in this story—it’s the incumbent living through disruption. The direct-to-consumer mattress brands counter-positioned against Leggett’s traditional customers, but the impact landed on Leggett all the same: the ecosystem where it had thrived got rewired.

Switching Costs: LOW-MODERATE

- Automotive: Some switching costs exist because components get designed into platforms and require testing and certification.

- Bedding: Low—springs are largely interchangeable, and foam is foam.

- Private-label mattresses: Moderate, mainly because supply chains and production planning get integrated.

Overall: switching costs aren’t strong enough to protect pricing.

Branding: NONE (B2B)

End consumers don’t know Leggett & Platt exists. The company never became “Intel Inside” for sleep or seating. The brands that matter live at the retail layer—Tempur, Purple, and others—while Leggett stays invisible, which means the value of branding accrues to its customers, not to it.

Cornered Resource: NONE

- No proprietary technology that can’t be replicated

- Manufacturing know-how is valuable, but not exclusive

- Patents exist, but none are category-defining

- Strong talent, but not irreplaceable

Process Power: WEAK

Leggett does have operational competence. It knows how to run high-volume manufacturing, and it has a continuous improvement culture. But these gains tend to be incremental—helpful, not decisive. Process strength can defend a position at the margin; it can’t, by itself, overcome structurally tough industries and buyer-driven pricing.

Overall Hamilton Assessment: Leggett & Platt has zero to one of the 7 Powers. At best, it has weak Process Power in certain operations. That maps cleanly to the last decade-plus of value destruction: a big company competing in commodity-adjacent markets without durable competitive advantages.

What you’re left with is “scale without power”—big, but not mighty. Volume doesn’t automatically translate into leverage. Market share doesn’t become a moat. And that’s why the stock could generate billions in revenue and still go nowhere for years: no moat leads to no pricing power, which leads to margin compression, which leads to value destruction.

XVI. The Path Forward: Can Leggett Be Fixed?

There are a few ways this ends. None of them are impossible. But they don’t have equal odds.

The Optimistic Scenario:

In the best case, the restructuring actually does what it’s supposed to do. Leggett captures the full $60–$70 million in annual EBIT benefit, and margins expand into the 8–9% range as the cost base finally matches the new reality of demand.

Then the outside world helps. Housing recovers, and bedding volumes come back with it. Tariffs continue to favor domestic manufacturing in rod and springs. The private-label mattress business scales in a way that’s profitable, not just busy. Automotive content per vehicle keeps rising, even as EVs change the mix. With debt paid down, financial flexibility returns—and maybe even a path to credit improvements. In that version of the story, the slimmer, more focused Leggett outperforms the old conglomerate simply because it’s no longer fighting itself.

The Realistic Scenario:

More likely, the restructuring helps—but it doesn’t fix the underlying issue that’s been haunting the company for a decade: the competitive position. Costs come out, margins improve some, but pricing power doesn’t magically appear.

Revenue continues a slow bleed as share shifts and end markets stay choppy. Leggett becomes what turnarounds often become: a “melting ice cube,” throwing off cash while gradually shrinking. In that world, the endgame is less about rebuilding a durable growth machine and more about who buys what’s left—private equity, a strategic acquirer, or a breakup where the parts are worth more than the whole.

The Pessimistic Scenario:

If the macro turns down again—especially if housing stays weak—Leggett’s problems compound quickly. Bedding disruption accelerates, with more direct-to-consumer pressure and more imports. Automotive gets hit harder by the EV transition than expected, and the company finds itself with assets that don’t earn their keep.

That’s when the familiar industrial spiral starts: another round of impairments, another restructuring cycle in 2026–2027, and credit pressure that narrows the company’s options. At the extreme, you’re talking about a distressed sale—or worse.

What would need to be true for Leggett to thrive:

1. Aggressive portfolio pruning, exiting businesses that can’t clear acceptable ROIC hurdles

2. Real investment in product innovation—not just cost-cutting and footprint reductions

3. Vertical integration or partnerships with the brands and channels that are actually growing

4. Geographic expansion into faster-growing markets

5. M&A that creates genuine pricing power, not just more complexity

6. Leadership willing to place bold bets, not simply manage decline

The honest assessment is that Leggett is trying to get back to “good enough” profitability in businesses that have become structurally harder. That’s a tough place to create real shareholder value. And the Somnigroup proposal is a clue that plenty of the market thinks the cleanest solution might not be a standalone comeback at all—but becoming part of a larger, vertically integrated platform.

XVII. Lessons for Investors & Operators

1. Diversification can become "deworsification."

Leggett’s 100-plus business units didn’t add resilience as much as they added complexity. When housing rolls over, when auto production slows, when consumers pull back—most of your portfolio feels it anyway. Spreading yourself thin isn’t the same thing as being protected.

2. The dividend trap is real.

At some point, protecting the streak became more important than allocating capital. Shareholders likely would’ve been better served by a smaller cut and real reinvestment back in 2015 than by holding the line until the 2024 slash. “Dividend King” status is a reputation, not a moat—and it’s always a lagging indicator.

3. Incrementalism fails against disruption.

Leggett responded to a rewired mattress market with small bets and gradual adjustments. Casper, Purple, and the rest didn’t adjust the edges—they rebuilt distribution from scratch. When your market is being disrupted, you need big moves, and you need the willingness to cannibalize your own profit pool before someone else does it for you.

4. Scale without pricing power is hollow.

Being the biggest doesn’t matter if you’re selling something buyers treat like a commodity. “Market leadership” without the ability to raise prices isn’t strategy—it’s a slogan.

5. B2B suppliers get exposed when customers consolidate.

As private equity rolled up mattress manufacturers and retailers, Leggett’s negotiating leverage shrank. In hindsight, the company needed to either partner tightly with the winners or move up the stack. Being the “arms dealer” works until your customers get bigger, tougher, and more vertically ambitious than you are.

6. Financial engineering can’t fix a broken business model.

Restructuring, divestitures, and cost-cutting can buy time. They can’t create differentiation. Without a credible path to growth and pricing power, you’re not fixing the business—you’re just managing decline with better optics.

7. "Too late" is a real thing in business.

The moment to truly reset Leggett was 2014 to 2016, when disruption was visible but not yet devastating. By 2024, the company was playing defense, with fewer options and less flexibility. Windows close. Move slowly enough, and the market makes the decision for you.

XVIII. Bull vs. Bear: The Investment Debate Today

THE BULL CASE: - The stock is down more than 75% from its highs, which means a lot of disappointment is already baked in. - On forward earnings, shares trade at roughly 8x—far below what the market used to pay for “steady industrial + dividend” Leggett. - The restructuring is no longer just a slide deck. Incremental EBIT improvement is showing up, and a leaner footprint could create real operating leverage if demand stabilizes. - A housing recovery would matter disproportionately. If rates ease and big-ticket purchases thaw, bedding and furnishings volumes could rebound. - Domestic manufacturing can be a real advantage in a tariff-heavy world, particularly in rod and wire-related categories. - The dividend reset, painful as it was, frees up cash to pay down debt and rebuild flexibility. - Management is finally doing the hard, unpopular work—closing plants, simplifying the portfolio, and prioritizing the balance sheet. - The Somnigroup approach is a reminder that, even if Leggett isn’t a great standalone compounder anymore, its assets may still be strategically valuable to a vertically integrated buyer.

THE BEAR CASE: - The underlying model still looks like a structurally challenged one: commodity-adjacent products, powerful buyers, and no durable competitive advantage to protect pricing. - Key end markets remain weak, and it’s not obvious what forces them into a durable recovery anytime soon. - Bedding share can keep leaking, especially against more integrated players with tighter control over the value chain. - In automotive, the EV transition and shifting vehicle architectures may be more disruptive than management has historically implied. - Execution risk is high. Restructurings look clean on paper, but they can underdeliver, take longer than expected, or get competed away through pricing. - Growth options are limited. Organic growth is hard in mature categories, and M&A risks repeating the old playbook—buying complexity instead of building advantage. - Investor trust has been damaged by missed targets and the dividend break, which makes the “multiple rerating” case harder. - It has the classic feel of a value trap: it looks cheap, stays cheap, and shrinks.

THE REALIST TAKE: This is a “show me” story. It needs multiple quarters of consistent execution before it earns the benefit of the doubt again. That makes it hard to love on either side—too uncertain to be a high-conviction long, and too operationally messy to be a clean short.

If you’re a contrarian with patience, you can sketch a path where housing normalizes, restructuring benefits stick, and the stock has meaningful upside over a multi-year window. But for most investors, the risk-reward is uncomfortable: a lot can go right and still leave you with a business that’s merely okay.

XIX. Epilogue: Recent Developments & What Comes Next

By late December 2025, the outlines of the new Leggett & Platt were finally coming into view. The aerospace divestiture had closed, putting $250 million onto the balance sheet. The restructuring was largely complete, with the full run-rate benefits expected by year-end. Guidance still called for $4.0 to $4.1 billion of revenue and $1.00 to $1.10 of adjusted EPS for 2025. Debt reduction remained the priority. And hovering over all of it: the Somnigroup acquisition proposal, now sitting with Leggett’s board for review.

The next chapter is defined less by what Leggett says it wants—and more by what the world will allow.

Will the Somnigroup deal actually happen, and if so, at what price? The board’s response will be a tell on whether management believes there’s a real standalone path left, or whether the cleanest outcome is to fold into a bigger, vertically integrated platform. Beyond that, the questions are the ones you’d expect for a company trying to turn itself around in slow motion: does housing finally recover in 2026, lifting demand for bedding and furnishings? Can bedding revenue stabilize, or does the core keep shrinking? What else gets sold, and at what valuations? And even if the cost cuts land, do the margin gains stick—or does competition simply price them away?

In other words: is Leggett still a company in five years, or a set of assets living inside someone else’s?

The competitive landscape isn’t standing still while Leggett restructures. The mattress industry, in particular, seems to be settling into a new equilibrium. The direct-to-consumer frenzy has cooled—Casper itself was acquired after failing to reach profitability—and the winners increasingly look omnichannel: online plus stores, brand plus distribution. Somnigroup’s combination of manufacturing, brands, and retail is one vision of what that future looks like. Leggett’s role in that world is the open question, because being an “arms dealer” is a tougher position when the biggest buyer is also building the biggest integrated machine.

If you’re a fundamental investor watching this story, the near-term tells are straightforward: - Q4 2025 and Q1 2026 results, to see whether the restructuring is showing up cleanly in the numbers - Bedding volume trends, for any sign of stabilization versus continued erosion - Management commentary on Somnigroup and any other strategic alternatives - Credit metrics and potential ratings actions - Evidence of organic growth, or continued shrinkage masked by cost cuts

And if you want to boil it down to the essentials, there are really two KPIs that matter most: 1. EBIT margin: the clearest read on whether the cost actions are real and whether any pricing power exists. You want to see adjusted margins sustainably above the mid-single digits, and you want to know why they’re moving. 2. Bedding segment volume: the heartbeat of the company’s long-term relevance. Stabilization is the floor. Any return to growth would be a genuine signal that the business isn’t just getting smaller more efficiently.

Stepping back, the Leggett & Platt story is, in many ways, a case study in incremental decline: a good company that became a mediocre one because it didn’t evolve fast enough. The 2020s are now about whether it can stabilize and find a new purpose—or whether the most rational future is to be acquired by Somnigroup or someone like it.

This isn’t a growth story. It’s a “can they survive and be okay?” story. And it’s also a reminder that history doesn’t compound by itself. Competitive advantages do—until they don’t. For long-time shareholders, the pain wasn’t just the stock price. It was the slow realization that protecting the dividend streak and maintaining the old model didn’t protect value.

The ultimate lesson is the simplest one: in business, standing still is moving backward. Leggett & Platt stood still for too long. As 2025 closes, the only question left is whether it still has enough room—and enough time—to change course.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music