LendingClub: From Peer-to-Peer Pioneer to Digital Bank

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

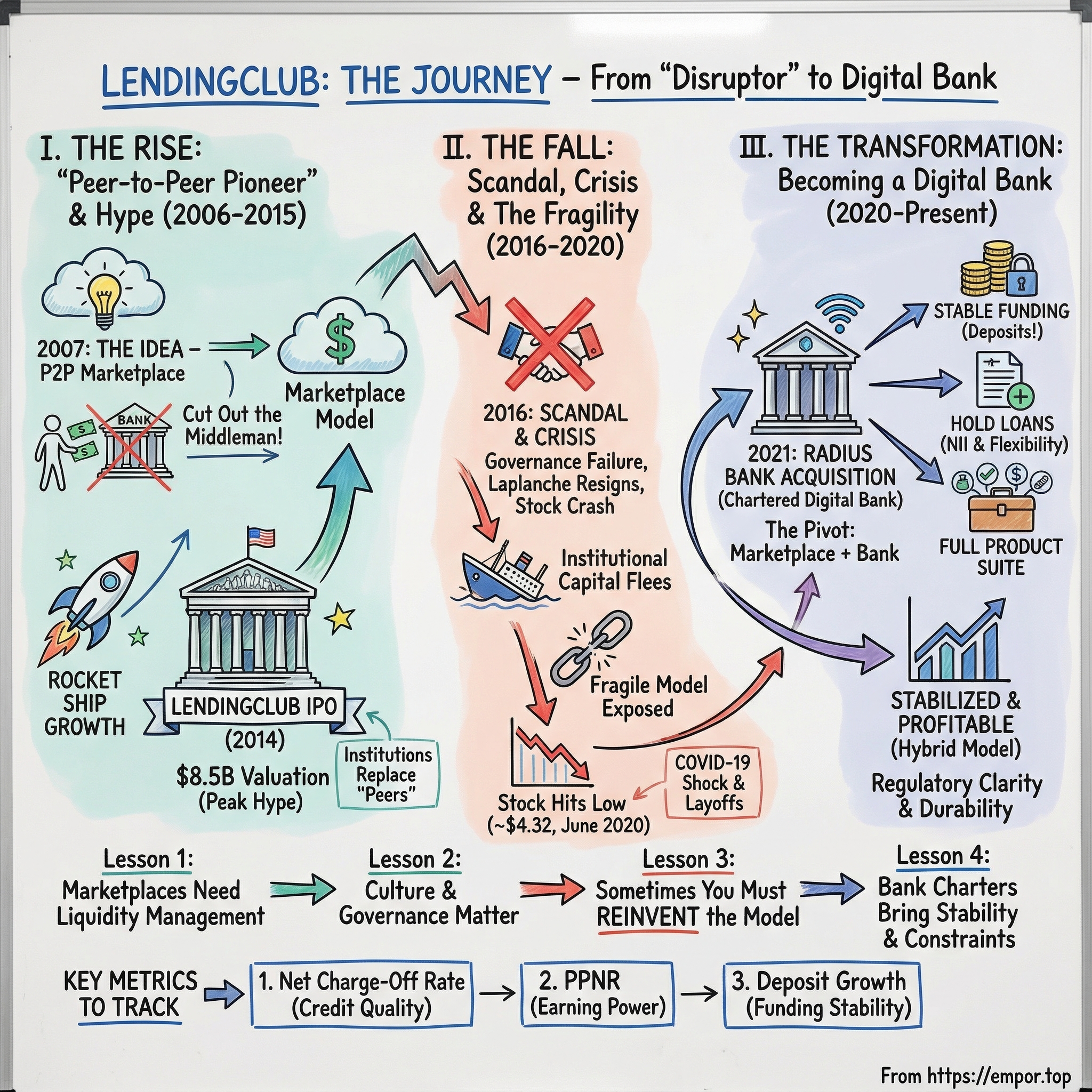

Picture this: December 2014, on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. A French-American entrepreneur named Renaud Laplanche rings the opening bell as LendingClub’s banner stretches across the building outside. The IPO prices at $15. By the end of the day, the stock is up 56%, and LendingClub is suddenly worth about $8.5 billion.

This was the moment the pitch became a public-market promise. LendingClub wasn’t just another lender. It was going to reinvent consumer credit: cut out the bank middleman, match borrowers directly with investors, and give both sides a better deal than they’d get from Wells Fargo or Bank of America.

Now jump ahead six years. It’s June 2020, and LendingClub is trading under $5, hitting an all-time low of $4.32 on June 26. The founder is gone, pushed out after a governance scandal. The “peer-to-peer” model that made the company famous has largely faded into the background. The company is laying off roughly a third of its workforce. And the ultimate irony is that the thing it once positioned itself against—being a bank—is exactly what it’s trying to become.

That whiplash is the point. LendingClub’s story breaks cleanly into three eras: first, the disruptor era, when it sold the dream of democratized credit and pulled in billions from yield-hungry investors. Then the crisis era, when scandal, weakening loan performance, and a tightening market exposed just how fragile the model could be. And finally, the reinvention era, when LendingClub remade itself into a chartered digital bank—one of the most dramatic pivots in modern fintech.

Underneath the drama is a deceptively simple question: can a fintech disruptor create durable value in lending, or do these companies eventually either blow up or turn into the very institutions they set out to replace?

Along the way, we’ll get into why “peer-to-peer” was never quite as peer-to-peer as the branding implied, how a single governance failure can wipe out years of momentum, and what happens when the “tech” in fintech collides with credit cycles, capital constraints, and regulators with long memories.

And to understand how it all started, we need to go back to the original spark: a moment of frustration that turned into an idea.

II. The Opportunity: Consumer Credit Before LendingClub

To understand what LendingClub thought it could fix, you have to picture consumer credit in the mid-2000s. Americans were borrowing like crazy—credit card debt was closing in on $900 billion. The typical card charged something like 15 to 18% interest, and plenty of people paid a lot more.

At the same time, if you were on the other side of the equation—someone with money to save—you were basically out of luck. Bank accounts paid almost nothing, and even certificates of deposit had slid to under 2%.

This gap was the whole business. Insiders sometimes described it as a “credit spread sandwich”: banks took deposits at 1 to 2%, turned around and lent at 15 to 20%, and kept the difference. They could make a real argument for why that spread existed: branches aren’t free, marketing is expensive, fraud is constant, collections are messy, regulators demand systems and paperwork, and some percentage of borrowers always default.

But to a new generation of entrepreneurs, that spread also looked like an opening. Especially because the internet had already rewritten the rules in industry after industry—media, retail, communications—yet banking still felt oddly frozen in place. You might be able to check your balance online, but the core machinery of credit—how loans were priced, approved, and distributed—had barely changed in decades.

And the timing was eerie. LendingClub was founded in December 2006, just months before the mortgage market began its spectacular unraveling. The traditional banking system was about to be tested harder than at any point since the Great Depression. Trust in incumbents would crater, and appetite for alternatives would rise.

At the same time, “marketplaces” were having a moment. eBay had shown that strangers would transact if you wrapped the exchange in the right platform and incentives. Airbnb was proving that even highly personal assets—your home—could be reliably shared with the right trust layer. So it was natural to ask the next question: why not money?

Could you build a marketplace where people with extra cash lent directly to people who needed it, with the platform as the intermediary instead of a bank?

The idea wasn’t coming out of nowhere. In the UK, Zopa launched in 2005 and helped popularize the peer-to-peer lending concept. In the U.S., Prosper launched in 2006, showing the model could exist stateside before LendingClub even got off the ground. Suddenly it wasn’t a thought experiment. It was a land grab.

The pitch was clean and intuitive. Borrowers would get lower rates than credit cards because there wouldn’t be a bank taking such a big spread. Lenders would earn better returns than a savings account because they’d actually be taking credit risk. And the platform would take a small fee on each transaction—enough to build a real business, without the cost structure of traditional banking.

That was the opportunity Renaud Laplanche saw. And the way he found it says a lot about how the best startups actually start.

III. Founding Story: Renaud Laplanche & The Peer-to-Peer Vision (2006-2007)

Renaud Laplanche was nobody’s idea of a standard-issue Silicon Valley founder. Born in France in 1970, he grew up obsessed with sailing and competed at a national level, winning French championships in 1988 and 1990 in the Laser class—those fast, minimalist one-person boats.

His professional path was just as unconventional for a future fintech founder. He trained as a lawyer, earning a post-graduate degree in Tax and Corporate Law from Université de Montpellier, then picked up MBAs from HEC in Paris and London Business School. In other words: he didn’t just understand finance. He understood the rules finance plays by.

After school, he landed at Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton, one of those elite New York firms that sits at the intersection of big money and big regulation. He spent nearly five years in structured finance work, including time at Credit Suisse First Boston. And by all accounts, he wasn’t miserable. He liked the work. But the entrepreneurial itch was there.

That itch turned into his first company: TripleHop Technologies, which built enterprise search software called MatchPoint. Not glamorous, but useful. Oracle bought TripleHop in 2005, giving Laplanche the two things that change a founder’s options overnight: credibility and cash.

Then came the moment that made LendingClub inevitable.

In 2006, as he was getting ready for a vacation, Laplanche did what most people avoid: he looked closely at his personal finances. And the numbers felt insane. His credit card charged 18% interest. His “high-yield” certificate of deposit paid about 1.5%. Same bank. Two completely different worlds. The bank was paying him next to nothing as a saver, while charging him premium pricing as a borrower—and pocketing the spread for playing middleman.

So he asked a simple question: what if you didn’t need the middleman?

If you could connect investors directly with borrowers, maybe borrowers could pay less, investors could earn more, and the platform could take a small fee for making the match. That idea—cutting the bank out and letting a marketplace set the terms—was the core insight that became LendingClub.

In December 2006, Laplanche co-founded LendingClub with Soul Htite. And their first go-to-market strategy was genuinely wild by today’s standards: they launched on Facebook.

This wasn’t a gimmick. Early peer-to-peer lending theory leaned hard on trust and social connection. The idea was that people would be more willing to lend, and more likely to repay, if there was some human context—shared networks, shared schools, shared communities. LendingClub built what it called “LendingMatch” to pair borrowers and lenders using signals like shared geography, schools, or groups, with the ambition to eventually connect people through friends-of-friends.

The timing was perfect. LendingClub was one of Facebook’s first applications, an original Facebook Platform/F8 partner that launched with F8 on May 24. It closed its first loan on June 6 and soon after had made 27 loans totaling $101,250. It’s hard to imagine now, but LendingClub wasn’t just early to fintech. It was early to Facebook apps.

The Facebook experiment proved something important: strangers would trust a platform with real money. It also proved something else: this wasn’t going to scale on social vibes alone. The early user base skewed young, and “college students on Facebook” weren’t exactly the dream borrower profile. And because there weren’t enough lenders on the platform at first, LendingClub effectively funded early loans using angel capital—about $12 million—just to keep the machine moving.

It generated buzz, but it was also a signal: if LendingClub wanted to become a real lending marketplace, it needed to stand on its own.

So in August 2007, the company pivoted off Facebook and became a standalone platform. That same month, it raised a $10.26 million Series A led by Norwest Venture Partners and Canaan Partners—capital to build a full-scale peer-to-peer lending business instead of an intriguing Facebook experiment.

And then Laplanche made the decision that would define LendingClub’s trajectory: he chose regulation over rebellion.

Instead of daring the SEC to catch up, LendingClub registered its offerings as securities with the Securities and Exchange Commission and even pursued the ability to support trading on a secondary market. That choice didn’t come free. After discussions with the SEC, LendingClub was told, in effect: yes, these are securities. The company would need to register the whole program as essentially a public offering.

In April 2008, LendingClub had to suspend operations for about six months to do the registration. For a young startup, a forced pause like that can be fatal. But LendingClub survived it, and when it came back, it had something precious in consumer finance: regulatory clarity that many competitors didn’t.

The pitch, though, stayed refreshingly simple. LendingClub was going to be the eBay of money—consumers lending to consumers, with the platform replacing the bank as matchmaker.

And as 2008 unfolded and trust in traditional banking cracked in real time, that vision—more transparent, more tech-driven, more direct—started to look less like a quirky idea from a Facebook app, and more like the beginning of something big.

IV. Building the Marketplace: Product-Market Fit & Growth (2007-2012)

Marketplace businesses all run into the same problem on day one: you can’t attract borrowers without lenders, and you can’t attract lenders without borrowers. LendingClub had to build both sides at the same time, and it had to do it while convincing people that clicking a button on a website could be as real as walking into a bank.

On the borrower side, the pitch was simple and visceral: get out from under credit card interest. If you had solid credit and were paying 18% on a Visa balance, LendingClub offered a shot at refinancing into something more like the low teens. And it did it with a fully online application process—still novel in the late 2000s—plus faster decisions than most traditional banks could manage.

On the lender side, the pitch was the mirror image: earn more than you could at a bank without taking stock-market risk. Between its founding and 2013, LendingClub reported investor returns in the mid-single digits to high-single digits, roughly in the 6% to 9% range. In a world where CDs were paying under 2%, that was a powerful hook—especially for investors who understood what they were buying: consumer credit risk, sliced into small pieces.

Underwriting was the fulcrum. This couldn’t work if it turned into a free-for-all. LendingClub screened applicants using credit scores, debt-to-income ratios, employment history, and other factors, then priced the loan based on the perceived risk. To make that risk legible to everyday investors, it created a grading system: A through G, with subgrades 1 through 5 inside each letter. That’s how you got a 35-step ladder from safest to riskiest. Interest rates ranged from about 6% at the top end to the mid-20s at the bottom, and investors could build portfolios by spreading small amounts across dozens or hundreds of loans.

The borrowers, crucially, weren’t the stereotypical “desperate” profile people associate with nonbank lenders. LendingClub’s own disclosures later showed an average borrower with a near-700 FICO score, meaningful credit history, and real income. This was more “prime borrower consolidating debt” than subprime loan sharking.

Then there was the part most consumers never saw, but that made the whole thing possible: WebBank.

WebBank was (and is) an FDIC-insured, state-chartered industrial bank based in Salt Lake City. LendingClub partnered with it so that WebBank originated the loans, and LendingClub handled everything else—marketing, underwriting, servicing, and distributing the loans to investors. The practical effect was huge: LendingClub could offer loans nationwide without going state by state to get separate lending licenses. And because WebBank was a Utah-chartered bank, it could originate loans at rates that would have run into usury limits in many other states. Call it regulatory arbitrage if you want—but it was legal, and it was a core piece of how early fintech lending scaled.

Here’s what made this era feel magical: LendingClub actually grew through the financial crisis.

While traditional banks were pulling back, tightening standards, and dealing with their own balance-sheet fires, LendingClub was steadily expanding. It hit profitability milestones, raised more venture capital, and started to feel like it had found a repeatable machine.

By November 2012, LendingClub had crossed $1 billion in cumulative loans since inception and said it was now cash flow positive. A billion dollars isn’t much in the context of JPMorgan. But for a company that had started as a Facebook app and had been forced to pause for months to satisfy the SEC, it was a major proof point: this was no longer an experiment.

In 2012, the institutional signals got louder. LendingClub’s SEC registration was renewed for $1 billion in Member Payment Dependent Notes. It brought in new money from Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, plus a personal investment from John J. Mack, the former CEO of Morgan Stanley. Kleiner Perkins partner Mary Meeker joined the board alongside Mack, and the company’s valuation climbed to around $570 million.

The board roster started to read like a bridge between Silicon Valley and the financial establishment: Mary Meeker. John Mack. Later, Larry Summers. That kind of lineup did more than add credibility—it told the market that marketplace lending wasn’t a fringe idea anymore. It was becoming an asset class.

But underneath that momentum was an irony that would matter later: the “peer-to-peer” part was fading.

LendingClub’s growth didn’t really turn into the kind of hockey stick that made headlines until professional investors showed up with dedicated funds built to deploy capital on the platform. Retail lenders—the original “peers”—simply couldn’t move money fast enough to keep up with borrower demand. Institutional investors—hedge funds, family offices, banks—began to dominate the supply side.

That shift lit the growth engine. It also quietly rewired the business’s risk. Because once your marketplace depends on big pools of institutional capital, you’re no longer just matching people on the internet. You’re managing confidence—and confidence can disappear overnight.

V. The Rocket Ship: Hyper-Growth & IPO Era (2012-2016)

Once institutions really leaned in, LendingClub stopped feeling like a quirky internet experiment and started looking like a new asset class. In a world of near-zero interest rates, big pools of money—hedge funds, asset managers, family offices—went hunting for yield. LendingClub’s loans offered something rare: consumer credit returns, packaged in a clean, online platform with data, grades, and diversification baked in. Capital flooded in. For the first time, LendingClub wasn’t scrambling to find lenders. It had more money ready to go than borrowers to lend to. The flywheel finally had torque.

In May 2013, that shift got its loudest validation yet: Google led a $125 million investment to buy a minority stake in the company, reportedly under seven percent. The round valued LendingClub at $1.55 billion—unicorn status, back when that word still meant something. And it sent a clear signal: one of the most sophisticated technology companies on earth thought this model was real.

The board started to look less like a startup board and more like a summit meeting. Google joined a roster that already included Mary Meeker, John Mack, and Larry Summers. Silicon Valley and Wall Street were effectively co-signing the same bet.

Then the growth turned into a headline machine. LendingClub had crossed $1 billion in cumulative originations in 2012. Within a couple of years, it was several times that, with originations accelerating fast enough that the industry couldn’t dismiss it as a niche. Marketplace lending was no longer a curiosity. It was starting to feel inevitable.

With the core personal loan product humming, LendingClub pushed outward—business lending, auto refinancing, patient financing. Laplanche told Forbes in April 2015 that the company would expand into car loans and mortgages. The ambition was clear: not just one better loan product, but a full-spectrum alternative to the consumer and small business credit stack at traditional banks.

Partnerships piled up, too. LendingClub announced a deal with Google to extend credit to smaller businesses using Google’s services. It signed additional partnerships with Alibaba.com, BancAlliance, and HomeAdvisor. And it partnered with Opportunity Fund in an initiative announced by former President Bill Clinton at the Clinton Global Initiative. For a stretch, it felt like everyone wanted a piece of the marketplace lending revolution—capital, distribution, credibility, all at once.

And then came the IPO.

On December 10, 2014, LendingClub went public in what was billed as the largest U.S. tech IPO of that year, raising roughly $1 billion in gross proceeds after the underwriters’ option. Shares priced at $15. The market’s verdict was immediate: LendingClub soared to an $8.46 billion valuation.

Put differently, a seven-year-old fintech platform was suddenly worth more than nearly every bank in America except the very biggest. In the days and weeks after the offering, the stock even briefly touched $28. The story wrote itself: the future of banking was going to be a website.

On CNBC’s “Squawk on the Street,” Laplanche didn’t play small. “What we focus on is really building the company for the next decade,” he said. “We think we have the opportunity to transform the entire banking system, making it more transparent, more cost efficient, more consumer friendly.”

But the higher the valuation climbed, the more the fault lines mattered.

By this point, “peer-to-peer” was mostly branding. A large share of LendingClub’s funding was coming from institutional buyers—especially hedge funds. That worked beautifully when credit was benign and investors were hungry. But institutional capital isn’t sticky like bank deposits. It can vanish fast—because of returns, headlines, liquidity needs, or simple fear.

And there was another quiet question sitting under the hype: were the unit economics truly structural, or were they being flattered by a historically friendly credit environment? LendingClub’s tech advantage was real. But banks weren’t standing still. They were digitizing, too—and they still had the cheapest funding source in finance: deposits.

None of that stopped the momentum in 2014 and 2015. LendingClub was the category leader. Laplanche was treated like the godfather of marketplace lending. The only debate was how high the growth curve could bend.

And then, with everyone leaning in, confidence snapped.

VI. The Fall: Scandal, Crisis & Near-Death (2016-2020)

On May 9, 2016, LendingClub dropped the news that instantly changed everything: its board had accepted Renaud Laplanche’s resignation as Chairman and CEO, following an internal investigation that found a violation of the company’s business practices.

Wall Street didn’t wait for the details. The stock got crushed, plunging 35% in a single day to about $4.62—its lowest level since the IPO. LendingClub had gone public less than a year and a half earlier as “the future of banking.” Now it was trading like a broken story.

The details were messy, and worse, they were exactly the kind of messy that spooks institutional capital. The board said an internal review found that LendingClub had falsified documentation connected to a $22 million sale of near-prime loans to Jefferies. Roughly 33 loans in the pool—about $3 million—didn’t meet the investor’s criteria. Rather than unwind the sale cleanly, company personnel backdated delivery dates to make the loans appear compliant. When the discrepancy was found, LendingClub used company funds to repurchase the loans.

Then came the governance gut punch: the review also found that Laplanche hadn’t fully disclosed a personal conflict. He had invested in an outside fund, Cirrix Capital, while LendingClub was considering—and later made—a significant investment in the same fund.

Several senior executives were pushed out alongside him. And the company’s problems were no longer just internal. The episode triggered investigations from the U.S. Department of Justice and the New York Department of Financial Services.

People who followed online lending split into camps. Some saw it as a compliance failure that got turned into a public hanging. Peter Renton, founder of Lend Academy and the LendIt conference, called the fallout overblown and said, “We have only ever really heard one side of the story.” Others saw it differently: not a one-off paperwork issue, but the inevitable outcome of a culture that had been optimized for growth and investor confidence.

One of the more pointed takes came from John Buttrick at Union Square Ventures, an investor in LendingClub and Upgrade. He wrote that, in retrospect, LendingClub probably went public too early. Financial services companies, he noted, are held to punishing standards in the public markets—compliance issues aren’t a speed bump, they’re a trapdoor. Renton put it even more bluntly: “This is the worst seven days in the history of the industry.”

With Laplanche gone, LendingClub handed the wheel to Scott Sanborn, who had joined in 2010 and had run marketing and operations. He became acting CEO, supported by director Hans Morris in a newly created executive chairman role. In June 2016, Sanborn was elevated to CEO permanently, tasked with restoring trust and running the company with more transparency and discipline.

But the scandal didn’t happen in a vacuum. The entire marketplace lending sector was wobbling. Other high-profile lenders were getting hit at the same time: OnDeck’s stock tumbled after missing revenue expectations, and Avant reportedly saw loan volume decline. The broader message from the market was clear: this wasn’t just a LendingClub problem. Investors were re-rating the whole category.

Inside LendingClub, the scandal accelerated a collapse in momentum. Originations contracted sharply—down to around $3.8 billion for 2016, more than 50% off the prior year’s peak.

And it exposed a set of deeper structural problems that had been building under the rocket-ship narrative.

First, underwriting had loosened during the growth years. When the company is built on volume, the temptation is always the same: take a little more risk to keep the machine fed. Later loan vintages performed worse, with higher default rates than earlier cohorts.

Second, the marketplace model was brutally procyclical. When times were good, institutional buyers flooded in. When confidence cracked, those same buyers stepped back—fast. And unlike a bank, LendingClub didn’t have deposits sitting there as stable fuel. No buyers meant no loans. No loans meant no revenue.

Third, the macro backdrop was turning. The Federal Reserve had started raising rates in December 2015. As rates moved up, LendingClub loans could look less compelling on a risk-adjusted basis, and funding costs rose. The spread that had looked so attractive in a zero-rate world started to feel tighter and more fragile.

The legal and regulatory clean-up dragged on for years. LendingClub faced a consolidated shareholder class action alleging materially false and misleading statements about business practices and internal controls; the case was settled for $125 million, with judgment finalized in September 2018. The regulatory chapter ended with more limited damage than the market had feared: the SEC credited LendingClub for “extraordinary cooperation,” and the company itself wasn’t charged. To settle with the SEC, LendingClub Asset Corporation, Laplanche, and CFO Carrie Dolan paid penalties of $4 million, $200,000, and $65,000 respectively.

Meanwhile, Laplanche moved on. After leaving, he took time off with his family, hiking in the Swiss Alps. By summer, he was gathering former LendingClub executives around a new idea. In August 2016, they started Upgrade in San Francisco—just a few blocks from LendingClub’s headquarters. In a twist that felt almost scripted, Jefferies, the same bank at the center of LendingClub’s altered-loan-dates scandal, became Upgrade’s first loan buyer. Upgrade would go on to raise over $750 million in venture capital.

For LendingClub, though, the years that followed were defined by a slow bleed. Originations stayed muted. The stock drifted lower. The gap between the IPO story and the new reality widened into a chasm.

Then came COVID.

In March 2020, credit markets froze and risk appetite evaporated. In April, LendingClub announced it would lay off around one third of its employees in anticipation of the downturn. As institutional investors fled, the vulnerability of the marketplace model stopped being theoretical. By June 26, 2020, LendingClub hit an all-time low of $4.32.

At that point, the question wasn’t whether LendingClub could recover its old narrative. It was whether the narrative could even work anymore.

Could the marketplace model survive? Or was it time for something radically different?

VII. The Transformation: Becoming a Bank (2020-2021)

The answer arrived in February 2020—almost comically late in the “we’re not a bank” storyline, and just weeks before COVID would break credit markets again. LendingClub announced it had signed a definitive agreement to acquire Radius Bancorp and its wholly owned subsidiary, Radius Bank, in a cash-and-stock deal valued at $185 million.

Radius was a Boston-based, digital-first bank with roughly $1.4 billion in assets. And the headline mattered: this was the first time a U.S. online lender had bought a bank.

If you step back, the logic is almost brutally straightforward. LendingClub’s biggest weakness wasn’t demand from borrowers. It was funding. The marketplace model lived and died by institutional appetite. When investors got spooked, LendingClub’s oxygen got cut off.

A bank charter fixed that.

As Scott Sanborn put it, a charter would let LendingClub combine “the leading digital loan provider online” with “a leading digital deposit gatherer.” Deposits are what make banks powerful: they’re sticky, they’re generally cheaper than wholesale money, and they don’t vanish overnight because a hedge fund risk committee held a meeting.

Sanborn also said the deal could save about $40 million a year in bank fees and funding costs. More importantly, it would let LendingClub do what banks have always done: keep some loans on its own balance sheet and earn the spread, not just collect an origination fee and hope capital markets stay open.

LendingClub later explained that it had been looking at banking capabilities since 2018. It originally connected with Radius to explore using Radius’s banking-as-a-service platform. But the more it dug in, the more the company saw a bigger play: merge the two sides of a bank’s balance sheet—loans and deposits—inside one digital, branchless model.

Calling it “transformative,” Sanborn told analysts the acquisition would add new funding sources, push the combined company toward becoming a digital bank, and offer what he described as a “superior route to a bank charter.” That last phrase is doing a lot of work. Building or obtaining a charter from scratch is slow, uncertain, and intensely political. Buying a bank that already has one is the more direct path—if regulators let you do it.

And that became the next chapter: the approval process.

It took almost a full year, and it played out during a global pandemic. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency approved the acquisition on Dec. 30, 2020. The Federal Reserve Board approved it shortly after. Then, on February 1, 2021, LendingClub closed the deal, acquired Radius, and formed LendingClub Bank, N.A.

Sanborn called it “a historic day” and “a true watershed moment for the industry.” LendingClub described the result as the only full-spectrum fintech marketplace bank and the first public U.S. neobank. In 2021, Radius was integrated into the LendingClub brand.

Operationally, this was a line in the sand. In October 2020, LendingClub stopped opening new loan accounts on its website as part of the restructuring around the coming bank transition. In December 2020, it ceased operating as a peer-to-peer lender.

The peer-to-peer era was over. The original vision—regular people lending to each other through a platform—had finally given way to something more traditional: a bank, just one built without branches and with a tech-first operating model.

So what actually changed once LendingClub had a bank charter?

First, funding. LendingClub could now gather FDIC-insured deposits and use them to fund loans—far more stable, and often cheaper, than relying on institutional buyers who could disappear when markets turned. By January 2023, LendingClub said deposits had continued to grow after the Radius acquisition. CFO Drew LaBenne noted that since the deal closed in early 2021, LendingClub had grown the bank from $2.7 billion in assets to $7.6 billion in assets.

Second, flexibility. As a bank, LendingClub could hold loans on its balance sheet and earn net interest income—the spread between what it pays for deposits and what it earns on loans—instead of living primarily on origination fees and loan sale economics.

Third, product expansion. A bank charter meant real deposit products: high-yield savings accounts, checking accounts, certificates of deposit, and the rest of the core banking toolkit. LendingClub didn’t have to be just a lending company anymore. It could be a full-service digital bank.

There were constraints too. LendingClub disclosed that an operating agreement began in connection with the Radius acquisition and the formation of LendingClub Bank in February 2021, setting parameters for how the bank would operate. Under its original terms, LendingClub said the operating agreement expired on Feb. 2, 2024.

And then there’s the irony—because you can’t tell this story without it. LendingClub spent its first decade defining itself as an alternative to banks. Now it was one, with capital requirements, regulatory oversight, and the same hard realities of credit and compliance.

But maybe that wasn’t a betrayal of the mission. Maybe it was the inevitable endgame: if you want to lend at scale, through cycles, in the United States, eventually you either partner with a bank… or you become one.

VIII. The New LendingClub: Digital Bank Era (2021-Present)

The LendingClub that exists today barely resembles the peer-to-peer poster child that rang the NYSE bell in 2014. It still originates loans online, but the engine underneath has changed. Funding now comes either from institutional buyers or from LendingClub’s own balance sheet as a chartered bank.

That’s the key shift: the business is now a hybrid of three models at once—marketplace, balance-sheet lending, and digital banking. LendingClub originates a loan, then decides what to do with it. It can sell the loan to institutional investors through its marketplace, securitize it into an asset-backed security, or hold it on balance sheet and earn interest over time. That flexibility matters, because it lets LendingClub lean into whatever channel makes the most sense as markets move.

The bank charter also changed the economics. LendingClub has said it lowered costs by eliminating issuing-bank partnerships and warehouse financing. And it increased revenue potential by building a balance sheet and earning net interest income. In the company’s words, it now has the option to sell some loans while keeping others, and it earns about three times as much on the loans it retains.

Deposits—the “sticky funding” that marketplace lending never had—have become the new flywheel. LendingClub reported $9.1 billion of deposits, up 24% from $7.3 billion the prior year, driven by savings and CD products. And newer products have scaled quickly: LevelUp Savings, launched in the third quarter of 2024, reached nearly $1.2 billion in balances by year end.

Financial performance has followed the funding shift. LendingClub said it had nearly doubled book value and delivered 12 consecutive quarters of profitability, even amid macroeconomic pressure and uncertainty.

“We had an exceptional quarter with year-over-year originations and revenue growth of 32% and 33%, respectively. Strong revenue growth combined with credit outperformance resulted in $38 million of net income, delivering double digit ROTCE in excess of our target and ahead of schedule,” said Scott Sanborn, LendingClub CEO.

“We’re off to a great start for 2025, growing total net revenue and originations more than 20% year over year to cross $100 billion in lifetime originations,” Sanborn said.

The balance sheet has grown too. Total assets of $10.6 billion increased 20% from $8.8 billion in the prior year.

The product set has broadened beyond the core personal loan. “We’re funding personal loans, auto loan refinance, and our purchase finance business through the bank,” Sanborn said. LendingClub has also launched savings products meant to reward good financial behavior and encourage consistent deposits.

Most importantly, the metric that used to haunt the company—credit—has improved. LendingClub reported that its consumer held-for-investment portfolio net charge-off rate improved to 4.7% from 8.1% the prior year, and said it continued to outperform a competitor set, with “+40% better performance.”

Sanborn’s leadership has been a stabilizing force through this entire pivot. By now his tenure has stretched to nearly a decade—an entirely different vibe than the chaos of 2016. “It feels great to be recognized for the hard work we’ve put in to transform our business model over the last few years,” Sanborn said. “As our recent quarterly and full year 2021 results have shown, our efforts are paying off.”

The stock, while still far below the IPO-era highs, has clawed back from the 2020 lows. As of December 19, 2025, LendingClub’s closing stock price was 19.65, giving it a market capitalization of about $2.27 billion.

All of this is playing out in a very different competitive arena than the one LendingClub helped create. SoFi—once best known for student loan refinancing—secured its own bank charter and pushed into a full-service neobank model. Upstart leaned into AI-first underwriting while staying a marketplace lender. Marcus, Goldman Sachs’s consumer bet, pulled back from several product lines after losing billions. And traditional banks, no longer dismissing fintech as a side show, accelerated digital investment across the board.

The market’s scoreboard has been weird. SoFi shares were up 65% year-to-date, while LendingClub was down 30% year-to-date and down 38% over the last year. You might assume the high-flying stock belongs to the profitable company—but here, it’s the opposite. LendingClub is the one posting profits, while SoFi has never turned a profit despite rapid revenue growth.

LendingClub may no longer be the clean, utopian “disrupt the banks” story that captivated people in 2014. But it has become something that tends to matter more in financial services: a profitable, scaled, regulated digital bank—with the ability to fund itself, manage through cycles, and operate with regulatory clarity that many pure fintechs still don’t have.

IX. Technology & Underwriting: The LendingClub Advantage

From the beginning, LendingClub tried to frame itself as a technology company that happened to do lending—not a lender with a decent website. The obvious question is whether that edge is still real, now that everyone has a sleek app and “AI” on the investor deck.

The real differentiator, if there is one, sits in underwriting. LendingClub says its credit decisioning and machine-learning models draw on an enormous internal dataset built from its history of originations and repayment behavior—information gathered not just at application time, but across the full customer lifecycle. In its own telling, the models are informed by over 150 billion “cells” of proprietary data derived from tens of millions of repayment events across economic cycles.

That’s the classic data flywheel: more loans create more repayment outcomes, which improve the models, which sharpen borrower selection and pricing, which improves performance, which brings in more funding and more loans. After roughly 18 years and more than $100 billion in originations, LendingClub has accumulated a history that’s hard for a new entrant to reproduce quickly—because you can’t fake time and cycles.

The company points to results it attributes to that underwriting advantage: four years of credit outperformance, and an improvement in its consumer held-for-investment portfolio net charge-off rate to 4.7%, down from 8.1% the prior year.

Then there’s the part customers actually feel: speed. Members can check their rate without impacting their credit score, get a decision in minutes, and, in many cases, see funds within days. That convenience used to be a huge gap versus traditional banks. It still matters, even if the gap has narrowed as incumbents have modernized their own digital experiences.

On the back end, servicing and collections have also become a software problem. LendingClub uses models to flag borrowers who are more likely to miss payments, enabling earlier outreach, and it leans on self-serve tools that reduce the need for expensive call-center labor.

The honest assessment is somewhere between the hype and the cynicism. LendingClub’s technology is meaningfully better than what many traditional banks were built on, especially in how it packages underwriting, pricing, and a clean member experience into one digital flow. But it’s not magic, and it’s not untouchable. A well-capitalized competitor can replicate a lot of the product experience.

Where LendingClub’s advantage is more durable is in the underwriting process itself—the cumulative learning embedded in models trained on years of repayment behavior through multiple environments. Even small improvements in predicting default risk can compound into real economics over time. Still, it’s not a forever moat. Competitors like Upstart are chasing the same prize with different data and different approaches, and in consumer credit, edges have a way of getting competed away unless you keep earning them.

X. Business Model Deep Dive & Unit Economics

LendingClub’s business today is easier to understand if you stop thinking of it as “a lending platform” and start thinking of it as a bank with a dial. For every loan it originates, it can choose the path that makes the most sense in that moment: keep it and earn interest over time, or sell it and earn fees now. That one choice—hold versus sell—drives almost everything in the unit economics.

At a high level, the model has four primary revenue streams:

Net interest income: As a bank, LendingClub earns the spread between what it collects on loans and what it pays on deposits. With deposits costing around 4% and loan rates often in the low-to-mid teens, the gross margin opportunity is real. But this is lending, not software—credit losses take a meaningful bite out of that spread.

Loan sales gains: When LendingClub sells loans through its marketplace, it earns an origination fee, typically a few percentage points of the loan amount, and it may earn an additional premium if investors buy the loans above par.

Servicing fees: LendingClub continues to service many of the loans it sells, collecting ongoing fees for processing payments, handling collections, and reporting to investors.

Transaction revenue: On the banking side, deposit accounts generate interchange and other transaction-based income.

The bank charter is what made this mix possible—and it fundamentally changed the math.

Before the Radius acquisition, LendingClub was paying WebBank to originate loans and leaning on warehouse financing to fund them while waiting to sell. Those are both structural costs of the old model, and they’re now largely gone. The company has estimated the charter saves about $40 million a year in fees and funding costs.

But the bigger change is the revenue per loan. When LendingClub sells a loan, it captures fees up front. When it retains a loan, it can earn interest income over the life of that loan. LendingClub has said it earns about three times as much on the loans it keeps versus the ones it sells. That’s the deposit flywheel in action: cheaper funding lets you hold more loans, and holding more loans lets you keep more of the economics.

Of course, there’s no free lunch. The tradeoff is capital.

As a bank holding company, LendingClub has to maintain regulatory capital ratios, including a consolidated Tier 1 leverage ratio of 11.0% and a CET1 capital ratio of 17.3%. That’s a position of strength, but it also acts like a governor on growth. If you want to keep more loans, you need more capital to support them—meaning growth can become constrained unless you generate capital internally or raise more equity.

Deposits are the other side of the balance-sheet engine, and they’ve become the stabilizer the marketplace model never had. LendingClub reported $8.9 billion of deposits, up 18% from $7.5 billion the prior year. Unlike institutional funding that can disappear with sentiment, deposits tend to be stickier—and that stability matters most when credit markets get weird.

Then there’s the question every bank eventually gets judged on: efficiency.

The efficiency ratio—non-interest expense divided by revenue—is a core scoreboard metric in banking. LendingClub’s is higher than traditional banks, which isn’t surprising for a growth-oriented, marketing-driven digital lender. But it benefits from being branchless: no rent-heavy retail footprint, no teller network, no regional operations stack. Some of that advantage gets given back through marketing spend, but the structural cost base is still lighter than most incumbents.

And finally, the part that always decides whether the whole thing works: credit.

Unsecured personal loans are inherently risky, and the business lives right at the edge where attractive returns exist, but defaults can erase profits fast if underwriting slips. LendingClub’s reported credit outperformance versus peers over the last four years is a meaningful signal. But this is still a cyclical business, and every lender looks disciplined until the environment really turns. The model is better than it used to be—more stable funding, more optionality, more spread capture—but it still rises and falls on one thing: how well LendingClub can price risk, through a full cycle, without getting tempted by growth.

XI. Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Medium-High

Fintech still pulls in founders and funding, and on the surface it’s never been easier to stand up a slick digital lending product. But the bar has moved since LendingClub’s early days. Getting a bank charter is hard, regulators are far more attentive, and credit businesses aren’t won by UI alone—scale and underwriting learnings compound.

LendingClub’s first-mover glow is long gone, but it isn’t nothing. Having lived through decades of credit conditions and amassed more than $100 billion in originations gives it a real base of historical performance data to train models on—and that’s not something a new entrant can conjure up quickly.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low-Medium

In LendingClub’s world, the key “suppliers” are funding sources—especially depositors—and, to a lesser extent, the vendors that power its tech stack. Deposits are competitive and rate-sensitive; savers will move for a better offer. But deposits are also stickier than institutional capital, because switching isn’t frictionless. Moving your money means changing direct deposits, updating bill pays, and dealing with the hassle.

On the technology side, supplier power is lower. Cloud infrastructure, core tooling, and many fintech building blocks have become increasingly commoditized, which means vendors typically can’t squeeze the economics the way a scarce funding source can.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High

Borrowers hold the leverage. A personal loan is a commodity: people shop on rate and terms, and the internet makes side-by-side comparisons effortless. Loyalty is thin because the relationship is usually transactional—take the loan, make the payments, move on.

That reality caps pricing power. To win, LendingClub has to keep showing up with a better combination of rate, speed, certainty, and a smooth experience for each credit profile.

Threat of Substitutes: High

If you need consumer credit, you have options: credit cards, HELOCs, buy-now-pay-later, 401(k) loans, borrowing from family, or just going to your bank. Credit card issuers have fought back with balance transfer offers. BNPL has pulled spending into point-of-sale installment plans. Traditional banks can often bundle lending into broader relationships.

So LendingClub isn’t selling something unique. It’s selling a familiar product, and the game is to deliver it faster, simpler, and at a better value than the substitutes.

Competitive Rivalry: Very High

This is the force that dominates everything. LendingClub is competing with banks that have enormous scale and cheap funding, fintech peers like SoFi and Upstart chasing the same borrowers with different angles, and incumbents like Discover and Capital One with deep customer relationships and distribution. Even marketplace-style platforms are still around in various forms.

In a market like this, there’s no “set it and forget it.” It’s an always-on race: who can underwrite best, fund cheapest, acquire customers most efficiently, and still keep credit losses under control.

Bottom Line: Lending is a tough neighborhood. With intense rivalry, powerful borrowers, and plenty of alternatives, easy profits get competed away. LendingClub’s hybrid strategy—fintech speed plus bank funding and stability—is its attempt to carve out an edge in an industry that doesn’t hand out moats for free.

XII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Moderate

LendingClub does get some scale benefits: once you’ve built the technology stack, the compliance machinery, and the management team, you can spread those fixed costs across a larger loan book and a bigger deposit base. But this isn’t software where margins expand endlessly. A meaningful portion of cost scales with volume—marketing to acquire borrowers, servicing them, and, most importantly, credit losses. The deposit franchise helps on the funding side, where scale can lower the blended cost of capital, but overall the scale advantage is real and still bounded.

Network Effects: Weak

The original peer-to-peer dream had a classic two-sided marketplace pitch: more lenders bring more borrowers, and more borrowers bring more lenders. That’s not really how it works anymore. In today’s model, borrowers aren’t showing up because a vibrant community of lenders exists; they’re showing up for a rate and a fast, certain experience. The “marketplace” functions less like a network effect machine and more like a distribution channel alongside balance-sheet lending.

Counter-Positioning: Strong Initially, Now Fading

Early on, LendingClub’s positioning was genuinely hard for banks to copy. Branch-heavy incumbents couldn’t lean fully into a low-cost, online-only model without undermining their own economics and channel strategy. But time does what it always does. Banks invested heavily in digital. Newer fintechs launched without legacy baggage. The industry adapted, and the original counter-positioning edge has mostly evaporated.

Switching Costs: Low

Switching costs are thin on both sides of LendingClub’s world. Borrowers refinance when they find a better rate. Depositors move money for yield. There’s some inertia—no one loves updating autopays and direct deposits—but it’s not a real lock-in. LendingClub has tried to add stickiness by bundling products like savings, checking, and lending, but the underlying behavior in consumer finance stays the same: people shop.

Branding: Moderate

LendingClub has real name recognition in personal loans because it helped pioneer the category online. But it isn’t a premium brand that gets to charge more just for being itself. Most consumers choose on attributes—rate, speed, approval certainty—not identity. The 2016 scandal also dented trust, even if years of solid execution have repaired some of the damage. Net: the brand helps acquisition efficiency a bit, but it doesn’t create pricing power.

Cornered Resource: Weak

There’s no single asset that LendingClub uniquely controls. Competitors can build similar datasets over time, especially at scale. Talent is mobile. Even the bank charter—valuable as it is—stops being special once multiple fintechs have them. LendingClub doesn’t have a cornered resource that forces the market to route through it.

Process Power: Moderate

Where LendingClub does have something real is in process: years of underwriting iteration, operating discipline, and a polished end-to-end customer journey. Models trained on billions of data points across multiple economic environments can create an edge that shows up in credit performance and pricing. Still, process advantages are defensible only as long as you keep improving them. Well-funded, well-run competitors can copy a lot over time.

Overall Assessment: LendingClub’s moats are modest, with the most durable strengths coming from scale and process power. Becoming a bank made the business sturdier—more stable funding, more ways to earn revenue, more regulatory clarity—but it didn’t create an unbeatable position. In a commoditized, intensely competitive market, there’s no single “power” that guarantees success. The only real moat is sustained execution.

XIII. Key Strategic Questions & Future Scenarios

Can LendingClub compete with SoFi's multi-product ecosystem strategy?

SoFi has gone broad on purpose—student loans, mortgages, investing, crypto, banking—the “one app for your entire financial life” play. LendingClub has gone the other way: stay tight around personal lending, deposits, and a handful of adjacent credit products.

Neither approach is automatically “right.” SoFi’s breadth can create a powerful cross-sell machine, but it also adds complexity and forces the company to keep finding new customers for new products. LendingClub’s focus can translate into sharper underwriting, cleaner operations, and more disciplined economics—but it also caps how big the relationship can become if the member only shows up when they need a loan.

Will LendingClub remain independent or become an acquisition target?

With a market cap north of $2 billion and a track record of profitability, LendingClub sits in an interesting spot: big enough to matter, small enough to buy. A traditional bank could look at it as a ready-made digital distribution and underwriting engine. A larger fintech could see it as consolidation plus a bank charter.

But bank deals don’t happen on vibes. Regulatory approval is slow and uncertain, and cultural integration is famously hard in financial services. For now, independence seems like the default path—but in this industry, the M&A window can open quickly.

How do they grow deposits without branches in a high-rate environment?

A branchless bank has to earn deposits the hard way: by competing on rate, experience, and trust. The risk is obvious—if you’re always paying up to win deposits, your margin gets squeezed.

So far, LendingClub has shown it can gather deposits with competitive yields, product tweaks like LevelUp Savings, and digital marketing. The real question is durability: can it keep deposits growing without turning the business into a permanent rate war?

The AI/ML arms race in credit underwriting: Can they stay ahead?

LendingClub likes to frame underwriting as its compounding advantage—models trained on a massive history of repayment behavior, informed by what it describes as over 150 billion “cells” of proprietary data.

That advantage matters, but it isn’t a trophy you win once. Upstart is building its own AI-first identity. SoFi has scale, data, and a bank charter too. And large banks have enormous datasets plus the budgets to hire and build. The edge accrues to whoever keeps collecting the most relevant signal and turns it into better credit performance and pricing. LendingClub has a head start, not a finish line.

Macro sensitivity: How vulnerable to recession?

Unsecured personal loans don’t get a free pass in a downturn. When unemployment rises, defaults rise. When defaults rise, investor appetite shrinks, and credit tightens everywhere.

The bank model makes LendingClub less fragile than it used to be—deposits are generally stickier than institutional marketplace funding—but it doesn’t make the company recession-proof. Credit losses will climb in any real downturn. The open question is whether LendingClub can manage the cycle with discipline and still protect profitability.

The bear case:

The brand never fully escapes the shadow of its earlier era. The product stays commoditized. LendingClub ends up stuck in the middle—no longer a high-growth fintech story, not valued like a top-tier bank either. In this world, it becomes a steady but unremarkable digital bank, with limited pricing power and limited upside.

The bull case:

The Radius pivot keeps paying off. Deposits provide durable, low-cost funding. Holding more loans boosts unit economics. Underwriting keeps outperforming, and that performance compounds as the dataset grows. With a bank charter and a more stable model than pure marketplaces, LendingClub expands thoughtfully into adjacent products and grows customer lifetime value. In this world, the market eventually re-rates LendingClub as what it now is: a profitable, growing, well-capitalized digital bank.

XIV. Lessons & Playbook

For Founders:

Marketplace dynamics are brutal. LendingClub’s original two-sided model lived or died on balance. You needed enough borrower demand to keep originations flowing, and enough investor supply to fund it. When institutional investors stepped back, the whole machine seized. If you’re building a marketplace, don’t just model the upside. Model the day one side goes missing.

Regulatory arbitrage is temporary. The WebBank partnership and the SEC registration path were smart strategies that unlocked scale. But they also underline a hard truth in finance: you can’t outrun regulation forever. If your growth depends on a loophole, assume the loophole closes.

Culture and governance matter. Whatever you believe about the underlying facts of 2016, the outcome was the same: trust broke, and value evaporated. In financial services, perception isn’t a side issue—it is the product. One compliance failure or undisclosed conflict can wipe out years of momentum, and boards don’t get to be casual about oversight.

Sometimes you must completely reinvent the business model. Scott Sanborn ultimately treated the marketplace model’s fragility as a structural problem, not a temporary downturn. The Radius deal and the bank pivot took courage, capital, and a long time horizon—but it’s what kept LendingClub alive.

First-mover advantage in fintech is overrated. LendingClub helped invent the modern marketplace lending category, but that didn’t guarantee lasting dominance. Rivals emerged with different models and different funding advantages. In lending, being early matters less than underwriting, funding durability, and execution through cycles.

For Investors:

Fintech valuations can be deceptive. In the hype, LendingClub traded like a tech company. In the downturn, it traded like a lender. That swing is the tell: most fintechs are financial businesses with better software, not software businesses that happen to touch money. Multiples follow the risk, not the UI.

Marketplace businesses often lack durable moats. Marketplaces can be incredible when network effects lock in users. In consumer credit, borrowers shop on rate and certainty, and capital providers follow risk-adjusted returns. That’s a tough setup for lasting marketplace power.

Credit businesses are cyclical. Every lender looks disciplined when the economy is calm. The real test is when unemployment rises, defaults increase, and funding gets cautious. Stress-test underwriting and be skeptical of growth that requires steadily loosening standards.

Post-scandal recovery is possible, but it’s slow. LendingClub didn’t “bounce back” in a quarter or two. The turnaround stretched across years, through leadership changes, regulatory cleanup, and a full business model shift. Scandal-impaired opportunities can pay off—but only if you have patience and conviction in the new operating cadence.

Bank charters are valuable but come with constraints. A charter brings deposits, regulatory clarity, and stable funding. It also brings capital requirements, examinations, and a permanent compliance burden. It’s a trade: less fragility, more rules, and a different kind of growth ceiling.

For Operators:

Two-sided marketplaces need liquidity management from day one. The chicken-and-egg problem doesn’t end once you find product-market fit—it just changes shape. LendingClub’s vulnerability showed up when institutional liquidity vanished. If one side is concentrated, treat it like a single point of failure.

Underwriting discipline must not be sacrificed for growth. The temptation in lending is always to keep volumes up, even if it means taking a little more risk. That “little” compounds fast across vintages. It’s often better to shrink and protect credit quality than to grow into a future charge-off wave.

Technology advantage erodes quickly. A smoother application flow and smarter automation help, but they’re not permanent differentiators. Competitors copy what works. The only lasting edge is continuous improvement—especially in credit models, pricing, and fraud.

Transformation requires bold moves and patience. The Radius acquisition wasn’t optimization; it was surgery. And surgery takes time to heal. LendingClub’s pivot worked because it addressed the core fragility in the model, even though it took years to fully show up in results.

XV. Epilogue & Reflections

LendingClub’s arc is a tidy summary of the fintech era itself: a bold promise, real innovation, euphoric growth, a humbling comedown, and then—against the odds—reinvention. It’s not a simple cautionary tale, and it’s not a victory lap either. It’s something more useful than both: a survival story.

What they got right was the original insight. Consumer credit really was broken. Credit cards charged too much, savings paid too little, and banks captured the spread. LendingClub built a faster, simpler borrowing experience, treated underwriting and servicing like software problems, and—unusually for a Silicon Valley startup—took regulation seriously early on. When the original model stopped working, it didn’t just optimize around the edges. It pivoted.

What they got wrong is just as instructive. The marketplace was never as pure as the branding implied, and the shift toward institutions made the entire system fragile. Underwriting discipline softened under growth pressure. And the governance failure in 2016 wasn’t just bad optics—it detonated trust, and in lending, trust is oxygen.

Where does that leave LendingClub now? A solid, branchless digital bank in a brutally competitive market. Since 2007, more than 5 million members have joined the Club to help reach their financial goals. The company is profitable and more durable than it used to be, but it’s not the 2014 story anymore—and it probably never will be. It trades at a fraction of its peak valuation, yet it has rebuilt into something sturdier and more grounded in the realities of credit and funding.

The most surprising part of the story might be the resilience. After the scandal, the stock crash, and the evaporation of institutional appetite, it would have been easy to assume the ending was already written. Instead, under new leadership, LendingClub made one of the more dramatic pivots in modern financial services: from marketplace lender to bank holding company.

If we could ask Renaud Laplanche anything, it would be: do you regret the IPO timing—and did you see the marketplace model’s structural vulnerability while you were building it, or only after it cracked?

If we could ask Scott Sanborn anything, it would be: when did you realize the marketplace model couldn’t survive a real stress test, and what convinced you that becoming a bank was the right kind of risk to take?

LendingClub’s story isn’t over. The company will keep evolving, competing, and navigating the same forces that shaped it from the start: credit cycles, customer acquisition, funding, and regulation. Whether it becomes a truly durable digital bank or runs into a new version of the old fragility is still an open question. But the journey—from a Facebook app to a billion-dollar IPO to near-death to bank transformation—is already a rich case study in how financial innovation actually happens, and how different reality is from the marketing that sells it.

XVI. Key Performance Indicators to Track

If you want a simple dashboard for whether the “digital bank” version of LendingClub is actually working, it comes down to three numbers.

1. Net Charge-Off Rate (NCO Rate)

This is credit losses as a percentage of average loans. In unsecured personal lending, it’s the tell. LendingClub has said it has outperformed peers on credit for the last four years, but that’s not a one-time trophy—it has to be proven again every quarter. If the NCO rate starts climbing, it’s a sign underwriting is slipping or the borrower mix is deteriorating. If it stays stable or improves, it supports the idea that the data and models are doing real work.

2. Pre-Provision Net Revenue (PPNR)

PPNR is revenue minus operating expenses, before credit provisions. Think of it as the business’s earning power before the credit cycle swings in and starts throwing elbows. PPNR that’s growing suggests the model is scaling and expenses aren’t rising as fast as revenue. PPNR that’s shrinking is a warning that costs, competition, or funding pressure may be eating the advantage.

3. Deposit Growth Rate

Deposits are the whole point of the pivot. They’re the stable, generally cheaper fuel source that replaces the old dependence on institutional buyers who can disappear when markets get nervous. Strong deposit growth signals customer traction and balance-sheet strength. And the mix matters: pay attention to how much growth is coming from brokered CDs—often more rate-sensitive—and how much is coming from direct consumer deposits, which tend to be stickier and more valuable.

Together, these three—credit quality, underlying operating power, and funding stability—tell you whether LendingClub’s reinvention is compounding… or whether the old fragilities are starting to creep back in under a new name.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music