Kenvue: The Consumer Health Giant's Journey from J&J Spinoff to Independence

Introduction

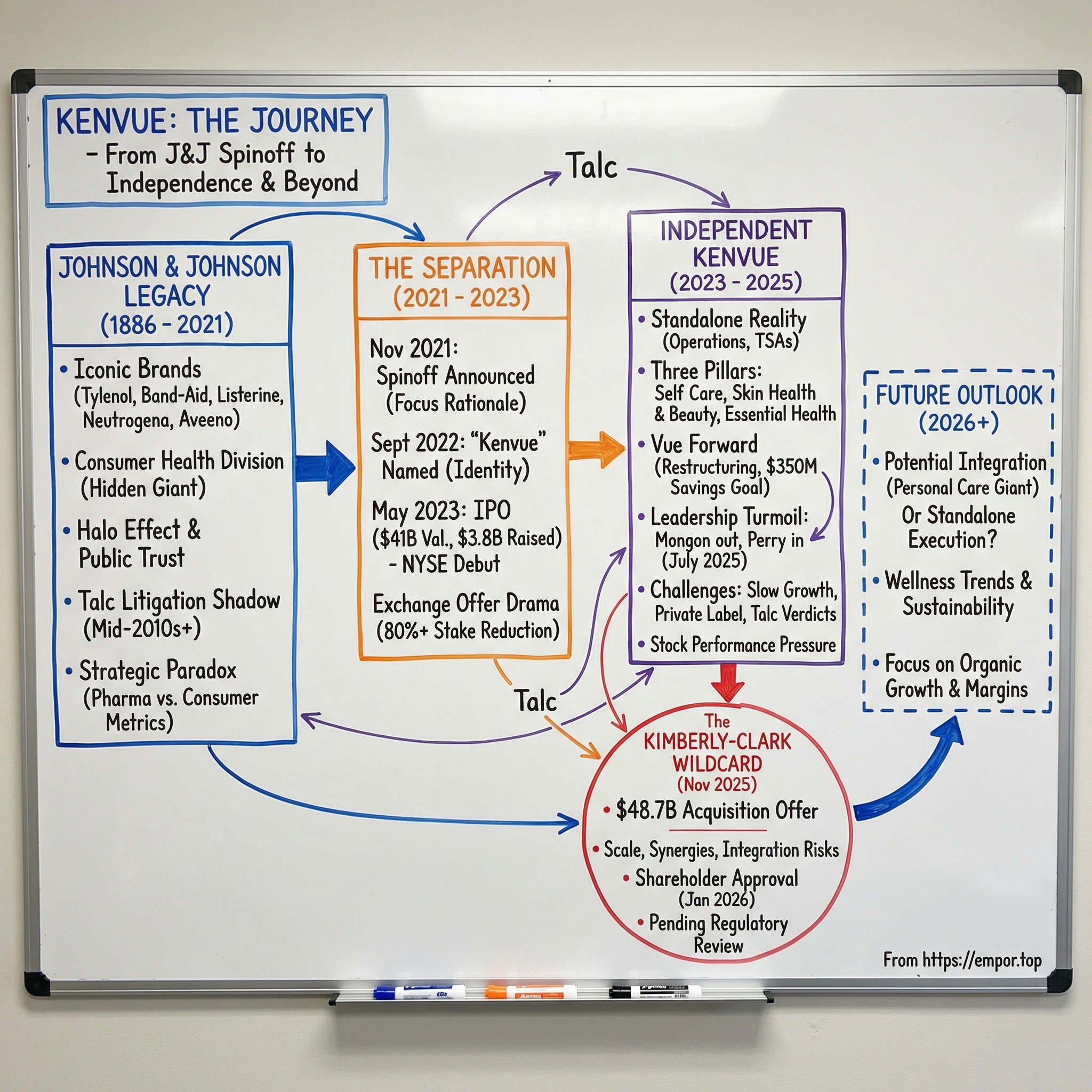

Open a medicine cabinet in America and there’s a good chance Kenvue is already in there. Tylenol for a headache. Band-Aid for a scraped knee. Listerine for the morning rinse. Neutrogena in the shower. Aveeno on dry winter skin. Zyrtec when the allergies hit. These aren’t fads or flash-in-the-pan products. They’re default choices—brands people buy on autopilot, that doctors and pharmacists mention by name, that have earned a kind of quiet permanence in homes across more than 165 countries.

And yet, until May 2023, none of these brands belonged to a standalone company. They lived inside Johnson & Johnson—tucked within one of the most complex healthcare conglomerates on Earth. Kenvue’s story is what happens when a pile of iconic consumer brands—doing $15.5 billion in annual sales and sitting at number 281 on the Fortune 500—gets carved out of a roughly $400 billion parent and told to prove it can thrive on its own.

It’s also a story about the mechanics and the psychology of big corporate separations: the financial engineering that makes a split tax-free, the operational headache of unplugging decades of shared systems, the challenge of building a culture that isn’t just “the consumer division,” and the existential question every conglomerate eventually confronts. Is the whole really worth more than the parts?

For Johnson & Johnson, that question had an increasingly obvious answer by late 2021. Consumer health had the brand halo, but not the economics of pharma or medical devices. Inside J&J, it had become the third wheel. The question wasn’t whether it would be let go—it was how.

What followed became one of the most closely watched corporate separations in modern American business: an IPO that raised nearly $4 billion, an exchange offer with mind-bending complexity, and a restructuring plan aimed at pulling $350 million of annual savings out of a business that had never truly had to compete as an independent company. Then came leadership turmoil. And finally, a twist almost nobody saw coming: a $48.7 billion acquisition offer from Kimberly-Clark that could make Kenvue’s “independent” era one of the shortest in Fortune 500 history.

This is the full story.

The Johnson & Johnson Legacy

In 1886, three brothers—Robert, James, and Edward Mead Johnson—started a company in New Brunswick, New Jersey with a straightforward idea: make sterile surgical supplies for a medical world that was only beginning to take germ theory seriously. The early success gave them room to expand from the operating room into the home. Baby powder arrived in 1894. Band-Aid adhesive bandages followed in 1920. Then the pace quickened. Johnson’s Baby Shampoo became a fixture in bathrooms. Tylenol, introduced in 1955, grew into a dominant name in over-the-counter pain relief. And Listerine joined the family through Johnson & Johnson’s 2006 purchase of Pfizer’s consumer health business, adding one more “default choice” to a portfolio that already showed up in nearly every aisle of the store.

For most of the twentieth century, this consumer business did something invaluable for Johnson & Johnson. It wasn’t the biggest profit engine—pharma and medical devices wore that crown—but it gave the company a level of public trust that most healthcare giants can’t buy. This is the “halo effect”: when people heard “Johnson & Johnson,” they didn’t picture oncology drugs, clinical trials, or complex medical devices. They pictured a baby in a bathtub. A Band-Aid on a kid’s knee. A gentle, dependable brand that had been around forever. That warm association spilled over into everything else J&J did, making the broader enterprise feel safer, steadier, and more trustworthy to consumers, doctors, regulators, and investors.

But the numbers never quite matched the sentiment. In 2021, consumer health brought in about $15 billion in annual revenue—huge on its own, but small next to the rest of the machine. Pharmaceuticals generated roughly $52 billion, and medical devices another $25 billion, for about $77 billion combined. And then there were margins. Pharma, with patent protection and pricing power, could run at gross margins above seventy percent. Consumer health lived in a different world—crowded shelves, constant promotions, and private-label competition—where economics were far less forgiving.

Then came talc.

In the mid-2010s, allegations that Johnson & Johnson’s baby powder contained traces of asbestos began to spread. Over time, it snowballed into one of the largest mass tort situations in American history. By the early 2020s, tens of thousands of plaintiffs had filed suit. J&J’s initial effort to contain the exposure—a controversial “Texas Two-Step” bankruptcy strategy that attempted to isolate liabilities in a subsidiary—was rejected by courts. In 2022, the company removed talc-based baby powder from global shelves and replaced it with a cornstarch formula. But by then, the damage wasn’t just legal. It was reputational. The halo that had taken generations to build suddenly had a crack running straight through the most iconic product in the portfolio.

As of early 2026, more than 67,000 claims remained pending in multidistrict litigation, making it the largest active MDL in the United States. And in December 2025, a Maryland jury ordered Johnson & Johnson and Kenvue to pay $1.56 billion to a single plaintiff—the largest individual verdict in fifteen years of talc litigation.

The talc crisis didn’t create the idea of a spinoff, but it sharpened the case for one. Consumer health—once the emotional heart of Johnson & Johnson—started to look like a source of legal exposure, reputational drag, and strategic distraction. Analysts increasingly argued that the conglomerate structure was working against shareholders: pharma, with blockbuster drugs and a deep pipeline, deserved one kind of valuation. Consumer health, with slower growth and litigation baggage, deserved another. Together, the pieces were pulling against each other.

That’s why the J&J legacy matters for Kenvue. It explains the paradox at the core of the new company. Kenvue inherited some of the most trusted brands ever built in consumer health—and it also inherited the shadow of a name whose trust had become complicated.

The Decision to Split: Strategic Rationale

On November 12, 2021, Johnson & Johnson’s then-CEO, Alex Gorsky, went public with what Wall Street had been debating for years: J&J was going to separate its consumer health division into its own, publicly traded company. The “new” Johnson & Johnson would be a tighter machine—pharmaceuticals and medical technology only. Explaining the move, Gorsky pointed to “a significant evolution in these markets, particularly on the consumer side,” a line delivered with the kind of careful restraint that signaled just how many audiences were listening.

And J&J wasn’t doing this in a vacuum. The industry was already moving in the same direction. Pfizer had combined its consumer health assets with GlaxoSmithKline’s in 2019, creating the business that later became Haleon and went public in 2022. Merck carved out Organon in 2021. Abbott’s earlier AbbVie spinoff in 2013 was another proof point that mega-healthcare conglomerates could, and would, break themselves apart.

Because pharma and consumer health may share a pharmacy aisle, but they run on different physics. Pharma is built on R&D-heavy moonshots, clinical trials, and patent-protected blockbusters. Consumer health is built on brand, distribution, marketing, and relentless operational excellence—winning endcaps, defending shelf space, and holding share against private label. Under one roof, you don’t get synergy so much as a permanent argument over priorities: What gets the capital? What gets management attention? What kind of culture are you optimizing for?

The split was also engineered to be tax-free for Johnson & Johnson shareholders, which meant structuring it carefully under Section 355 of the Internal Revenue Code. In practical terms, this wasn’t a sale where J&J cashed out. It was a distribution. Shareholders would ultimately end up holding stock in two companies instead of one, without the tax bill that would normally come with an outright divestiture. That structure—when you can pull it off—is corporate finance at its cleanest: value unlocked, minimal tax friction.

But let’s not pretend the timing was purely philosophical. Separating consumer health also helped create daylight between J&J’s pharma crown jewels and the reputational and legal gravity that had built up around the consumer portfolio—especially talc. Activists and governance-minded investors had been pushing for simplification for years, arguing that a focused pharma and med-tech company should trade at a higher multiple than a sprawling conglomerate with slower-growth categories and headline risk. If each business could stand on its own, the market could value each on its own terms.

Gorsky, CEO since 2012, set the separation in motion but didn’t carry it across the finish line. He handed the role to Joaquin Duato in January 2022, and Duato inherited the gritty work: carving out a roughly $15 billion business that, for decades, had been woven into J&J’s infrastructure. Consumer health didn’t just share a logo—it shared systems. Procurement. HR. Legal. Enterprise software. Supply chain processes. Untangling that reality meant Transition Service Agreements: formal contracts where J&J would keep providing key services to the soon-to-be independent company for a limited period—often a couple of years—while it stood up its own standalone capabilities.

So the strategic logic was simple: focus. The operational reality was anything but. And the outcome hinged on one thing—execution.

Birth of Kenvue: Name, Identity, and IPO

On September 28, 2022, Johnson & Johnson finally put a name to its soon-to-be independent consumer health company: Kenvue. It was a deliberate mash-up—“ken,” a Scottish English word for knowledge, and “vue,” a homophone of “view,” meant to suggest perspective and sight. Like most corporate naming reveals, it landed with the usual cocktail of reactions: curiosity, skepticism, and a little confusion. But the constraint set was real. The name had to be unique enough to stand apart from J&J, broad enough to cover everything from mouthwash to allergy meds, and clean enough to sit on the NYSE without feeling like a product line. Kenvue checked the boxes, even if it would take time for anyone to associate that unfamiliar word with the household staples inside it.

The identity work behind the name was just as intentional. Kenvue leaned warm and human—more “daily care” than “clinical giant.” And that was the point. Kenvue itself wasn’t meant to be a consumer-facing brand. Nobody would walk into a pharmacy asking for “a Kenvue.” The company’s real brands were Tylenol, Neutrogena, Band-Aid, Listerine, and the rest. Kenvue was the parent: a label designed for investors, partners, and employees—a way to build a standalone corporate story without disturbing the brand equity people actually trusted.

Then came the market debut. On May 4, 2023, Kenvue went public. Shares were priced at $22, putting the company at roughly a $41 billion valuation and raising about $3.8 billion—at the time, the largest IPO on a U.S. exchange since Rivian’s in November 2021. The timing mattered. The IPO window in 2023 was barely open: interest rates were up, inflation was stubborn, and investors were still nursing the hangover from the anything-goes exuberance of 2021. For a consumer health carve-out to get a multi-billion-dollar deal done in that environment said something simple and powerful: these brands still had pull.

In the first days of trading, the stock popped, eventually hitting $27.80 on May 15, 2023—eleven days after listing. But the early excitement didn’t erase the core debate. Professional investors loved the durability of the portfolio, but they also knew the math of the category. Consumer health is not built for hypergrowth; low single-digit organic growth is the norm, not a disappointment. Kenvue wasn’t being sold as a rocket ship. It was being sold as a steady, cash-generating business—one you buy for resilience, dividends, and incremental improvement rather than breakout upside.

And even after the IPO, the biggest question still hung in the air: Kenvue might have a ticker now, but it wasn’t truly free yet. Johnson & Johnson still owned the vast majority of the shares. The public float was just the beginning. How J&J would unwind the rest of its stake would become the defining plotline of Kenvue’s next chapter.

The Exchange Offer Drama

The IPO was the start of Kenvue’s public life, but it didn’t end the entanglement with Johnson & Johnson. J&J still controlled more than eighty percent of Kenvue. And if the goal was a clean, tax-efficient separation, that stake couldn’t just sit there. It had to move from the parent to the parent’s shareholders. The tool J&J chose was an exchange offer—one of those corporate-finance maneuvers that sounds simple in a press release and gets complicated the second you try to explain it at a dinner table.

The pitch to shareholders was straightforward: trade in your Johnson & Johnson shares, and you’d receive Kenvue shares in return, at an exchange ratio structured to provide a modest premium. Investors could tender all, some, or none of their J&J stock. Demand was so strong that the offer was oversubscribed—more J&J shareholders wanted Kenvue stock than J&J was willing to hand out under the terms. When it was all done, J&J accepted 190,955,436 shares of its own common stock in exchange for 1,533,830,450 shares of Kenvue common stock, an exchange ratio of about 8.0346 Kenvue shares for each J&J share tendered.

After the dust settled, Johnson & Johnson still owned roughly 9.5 percent of Kenvue—no longer a controlling parent, but not fully gone either. J&J later reduced that remaining position through open-market sales, further cutting the tie between the two companies.

This wasn’t just a technicality. The exchange offer reshaped who actually owned Kenvue. Overnight, the shareholder base shifted from one dominant holder to millions of former J&J shareholders. And many of those investors had bought J&J for its pharma and medical device engine, not for Band-Aid and Tylenol. Some were thrilled to keep the consumer business. Plenty weren’t. As they sold, it created a very real wave of supply hitting the market, putting pressure on Kenvue’s stock through the back half of 2023 and into 2024 as the market worked through the overhang.

Inside the company, this was the moment that mattered most. The IPO gave Kenvue a ticker. The exchange offer gave it independence. No majority owner. No parent-company safety net. No implicit lift from the Johnson & Johnson name. From here on out, Kenvue would have to earn its valuation the old-fashioned way: by defending its brands, improving its operations, and proving that “steady and durable” could still be a great business story.

The Portfolio: Three Pillars of Consumer Health

Now that Kenvue had to stand on its own, the easiest way to understand the business was to picture a familiar scene: walking the aisles of CVS, Walgreens, Walmart, Tesco, or Boots. Without realizing it, you move through Kenvue’s portfolio in three big blocks—each with its own logic, its own competitors, and its own job inside the company.

Self Care is the over-the-counter engine. It’s where Kenvue sells the products you buy because something hurts, something itches, or someone in the house is running a fever. Tylenol anchors the lineup, with Motrin, Benadryl, and Zyrtec beside it. Nicorette plays in smoking cessation. Zarbee’s caters to consumers who want a “natural” angle in cough and cold. And Calpol, a household name in the U.K., has long been a go-to children’s paracetamol brand. This segment is defensive by nature. People don’t stop getting headaches in a downturn. They don’t become less allergic when inflation is high. What matters most here is trust—especially in the high-stakes moments. At two in the morning, with a sick kid and a thermometer that won’t drop, brand recognition doesn’t feel like marketing. It feels like reassurance. Store-brand generics are always there, cheaper and often chemically equivalent, but the willingness to pay a premium for a familiar name has proven stubbornly durable.

Skin Health and Beauty is the more dynamic, more contested battleground. Neutrogena—founded in 1930 and acquired by Johnson & Johnson in 1994—is the centerpiece, positioned as dermatologist-recommended and perched between mass and prestige. Aveeno, with its oat-based formulations and naturals positioning, wins a different kind of loyalty, often tied to sensitivity and everyday use. Dr.Ci:Labo gives Kenvue a foothold in Japanese cosmeceuticals and the broader Asian beauty market. Le Petit Marseillais is a major name in France. Lubriderm holds down moisturizers. Rogaine tackles hair loss. OGX brings haircare into the mix. If Kenvue has a segment where it can credibly talk about more than steady, low-growth durability, it’s here. Skincare has been one of the liveliest categories in consumer products over the last decade, pushed forward by “skinification”—the idea that skincare is self-care, and that routines are worth investing in. The catch is the competitive set. Kenvue isn’t just up against incumbents like L’Oréal and Procter & Gamble. It’s also facing a constant wave of direct-to-consumer indie brands that win attention fast, especially with younger shoppers.

Essential Health is the heritage backbone—the brands that feel like they’ve always been there, because many of them have. Listerine, invented in 1879 and named after antiseptic surgery pioneer Joseph Lister, remains one of the most recognizable names in oral care. Johnson’s Baby—once the emotional centerpiece of the J&J halo—now sits inside Kenvue. Band-Aid is so embedded in everyday language that it’s become shorthand for the entire product category. The segment also includes feminine care brands like Stayfree pads, o.b. tampons, and Carefree liners, plus Desitin in diaper rash. Essential Health is the most mature pillar: modest growth, extremely steady demand. The advantage here is less about novelty and more about distribution. Retailers know these brands move reliably, so they get prime shelf space. And once a brand is that entrenched, dislodging it takes years and an enormous marketing budget.

Across these three pillars, Kenvue says its products touch more than a billion people globally, with multiple brands holding number-one or number-two positions in their categories. The real management challenge isn’t whether the portfolio is strong—it is. It’s deciding how to deploy resources inside it: how much to spend defending mature cash generators versus pushing for growth in skin health and beauty, how hard to lean into e-commerce and direct-to-consumer, and how to balance expansion in emerging markets with the day-to-day fight to hold share in developed ones.

Financial Performance and Transformation Initiatives

The first full year of Kenvue’s independent life wasn’t a victory lap. Fiscal 2024 revenue landed at $15.46 billion—basically unchanged from $15.44 billion in 2023. Earnings told a tougher story. Adjusted diluted EPS fell to $1.14 from $1.29. GAAP diluted EPS dropped to $0.54 from $0.90. The hit reflected a familiar mix for newly spun companies: restructuring charges, the real cost of building standalone operations, foreign-currency pressure, and a consumer who—after years of inflation—was getting more willing to trade down to store brands.

And Kenvue wasn’t alone. Across consumer staples, 2024 was a year where pricing stopped doing all the work. After multiple rounds of price increases to offset input costs, shoppers started pushing back. Private label kept taking share in developed markets. Retailers, armed with loyalty-program data, got sharper about steering customers toward their own products—often by promoting them aggressively right next to the national brands. For Kenvue, that pressure showed up most in categories like mouthwash and everyday skincare, where the gap between the branded product and the cheaper alternative can feel small.

Kenvue’s answer was a restructuring and reinvestment plan called “Our Vue Forward.” It was announced in early 2024 and approved by the board on May 6, 2024. The idea was straightforward: shrink the cost base now so the company could spend to defend and grow its brands later. The plan called for a net reduction of roughly four percent of the global workforce and aimed to deliver about $350 million in annualized pre-tax gross cost savings, fully realized by 2026. It wasn’t free. The company expected restructuring costs of about $275 million in each of fiscal 2024 and fiscal 2025.

One of the biggest levers was getting out from under the Transition Service Agreements with Johnson & Johnson. For a carve-out like Kenvue, TSAs are a necessary bridge—but they’re also a tax on independence. Every shared system and inherited process meant Kenvue was paying J&J for support while also paying to build replacements. Exiting those agreements wasn’t just operational progress; it was another clean cut in the separation.

By the end of 2024, Kenvue said it was already more than halfway to the full savings run rate. That helped fund a twenty percent increase in brand investment versus the prior year, including a meaningfully larger advertising budget. In consumer health, this kind of reinvestment isn’t optional. Brands don’t simply sit on shelves and stay strong. If you stop showing up in consumers’ minds—and in the aisle—you give competitors room to move in.

The near-term outlook stayed cautious. For 2025, management guided to net sales change between down one percent and up one percent, with organic growth of two to four percent offset by roughly three percentage points of foreign-currency headwinds. Through the first three quarters of 2025, trailing twelve-month revenue was $15.0 billion, about three percent lower year over year. The company guided for adjusted EPS of $1.00 to $1.05 for 2025.

That was the financial posture of Kenvue in its first chapters as a standalone company: trying to hold the line on sales while rebuilding the machine underneath. It wasn’t a growth story. And it wasn’t yet a clean margin-expansion story either. But if Vue Forward delivered the savings on schedule—and if the reinvestment started to show up in share trends—Kenvue had a path to becoming one.

Leadership and Culture Building

Thibaut Mongon was meant to be the steady hand who could guide Kenvue from “a division inside Johnson & Johnson” to a standalone consumer health leader. French-born, with more than two decades at J&J, he wasn’t learning the portfolio on the fly—he’d already run it. As worldwide chairman of J&J’s consumer business, Mongon had overseen the very brands that were now being asked to stand on their own. When Kenvue named him its first CEO, it read as a continuity play: keep retailers, employees, and investors calm while the separation mechanics—and the operational unplugging—played out.

That calm didn’t last.

On July 14, 2025, Kenvue’s board announced a CEO transition. The release used the soft language of corporate crisis—Mongon had “departed the company”—but the subtext was blunt: the board wasn’t satisfied with how fast the turnaround was moving, or where it was headed. The stock had fallen well below the IPO price. Vue Forward was still in the middle innings. And Kenvue’s organic growth wasn’t showing the kind of momentum public-market investors wanted from a newly independent, newly scrutinized company.

The board’s next move signaled a shift in what it valued. Kirk Perry stepped in as interim CEO. Perry had only joined Kenvue’s board seven months earlier, in December 2024, but he brought a resume that screamed execution. Most recently, he’d been president and CEO of Circana, the retail measurement and analytics firm that effectively acts as the scoreboard for consumer brands—tracking what sells, where, and why. Before that, he spent twenty-seven years at Procter & Gamble, eventually becoming president of its global fabric and home care division, P&G’s biggest and most profitable unit. Perry wasn’t a healthcare veteran. He was a brand operator: someone steeped in retailer dynamics, marketing discipline, and the unglamorous daily work of running a consumer-products machine.

By November 2025, the board made it official. Perry became Kenvue’s second CEO, dropping the “interim” label and taking full control of strategy. The timing was hard to ignore: his permanent appointment came just weeks before Kimberly-Clark’s acquisition announcement, instantly fueling speculation about whether he’d been brought in not just to fix the business—but to assess, and potentially execute, a sale.

But leadership changes were only the visible part of the story. The harder work was cultural.

Kenvue had more than 20,000 employees who had grown up as Johnson & Johnson people. They wore the J&J badge, lived inside J&J’s systems, and drew professional pride from one of the most trusted names in healthcare. Becoming “Kenvuers”—the company’s earnest term for its workforce—wasn’t something you could accomplish with a new sign on the building. It meant building an identity that didn’t borrow credibility from the parent: new leadership norms, new processes, new incentives, and, most importantly, a new answer to the question employees quietly ask in times of change: why should I believe this will work?

That’s the underappreciated tax of a spinoff. Inside a $400 billion conglomerate, you inherit infrastructure—shared services, institutional muscle memory, deep vendor relationships, and the gravitational pull of a storied brand. Standalone, you have to earn all of it. You rebuild systems, renegotiate contracts, redesign decision-making, and set priorities without a parent to break ties. And while that’s happening, people still have to ship product, defend shelf space, and hit numbers—often through reorganizations and layoffs like the ones embedded in Vue Forward.

In other words: Kenvue didn’t just spin out. It had to grow up fast, in public, with the whole market watching.

Competitive Landscape and Market Dynamics

Kenvue calls itself the world’s largest pure-play consumer health company by revenue, and it’s not just marketing bravado. With roughly $15 billion in annual sales, it’s bigger than Haleon—the GSK-Pfizer consumer health spinoff that listed in London in 2022 with around $12 billion in revenue. It’s also bigger than the consumer-health slices inside Procter & Gamble and Unilever. The difference is focus: P&G and Unilever can afford to treat these categories as parts of sprawling empires. Kenvue lives and dies by them.

And in consumer health, “competition” isn’t one rival across the street. It’s a different knife fight in every aisle.

In pain relief, Tylenol and Motrin battle a familiar cast: Advil (in the U.S., owned by Haleon), Bayer’s long-running aspirin franchise, and the ever-present wall of store-brand acetaminophen and ibuprofen that works “just as well” for a lot of shoppers. In skincare, Neutrogena is up against L’Oréal’s dermatology darling brands like La Roche-Posay and CeraVe—names that have surged in recent years, helped along by social-media-driven dermatologist credibility on platforms like TikTok and YouTube. In oral care, Listerine goes head-to-head with P&G’s Crest and Oral-B, Colgate-Palmolive’s flagship brand, and a wave of premium upstarts trying to convince consumers that mouthwash can be “designed,” not just purchased.

Then there’s the competitor that doesn’t buy Super Bowl ads: private label.

For years, store brands in consumer health lagged behind private label in food because the stakes felt higher. People might experiment with generic cereal, but hesitate with what they swallow or rub on a baby’s skin. That historical advantage is getting weaker. Retailers like Costco, Amazon, and Walmart have poured money into their own health and wellness brands, improving everything from formulation to packaging. And consumers who lived through the cost-of-living squeeze of 2022 to 2024 learned a new habit: trading down, realizing it’s fine, and not trading back up.

On top of shelf warfare, there’s regulation. Over-the-counter drugs in the U.S. sit under the FDA, with parallel regimes around the world. A big shift came with OTC monograph reform in 2020, passed as part of the CARES Act. It gave the FDA a faster administrative pathway to update the monographs—the rulebooks that dictate which active ingredients can be used in OTC products—instead of forcing the agency through slower, formal rulemaking. That can be good news if updates unlock new product possibilities. It can also be a real risk if an incumbent’s “legacy” formulation suddenly sits in a less comfortable regulatory spotlight.

And that gets to the core challenge: innovation here is not pharma innovation.

There are no patent cliffs, but there also aren’t many blockbuster moments. Winning usually looks like a thousand small improvements—a new delivery format, a more pleasant-tasting formulation, an ingredient that becomes permissible under an updated monograph, or a product tuned to a specific demographic need. Kenvue’s R&D budget is meaningful in absolute terms, but it’s modest as a share of revenue compared with pharmaceutical companies. So the question isn’t “can Kenvue invent the next wonder drug?” It’s “can Kenvue keep century-old brands feeling current in a world where consumers can discover—and switch to—something new in seconds?”

For investors, all of this collapses into one debate: is Kenvue’s scale and portfolio an enduring moat, or is it a slowly melting ice cube—ground down by faster-moving competitors, sharper retailers, and consumers who are more willing than ever to walk right past the famous name?

Playbook: Lessons from the Spinoff

The Kenvue separation is a case study in how spinoffs work in the real world—not in the clean diagrams bankers draw, but in markets that move, systems that don’t, and shareholder bases that rarely line up perfectly.

The first lesson is timing. Johnson & Johnson announced the spinoff in November 2021, when the post-pandemic bull market was still roaring. But Kenvue didn’t actually hit the public markets until May 2023—after rates had risen, risk appetite had faded, and IPOs had become far harder to sell. That long runway wasn’t procrastination; it was the unavoidable complexity of carving a roughly $15 billion business out of a roughly $400 billion parent. Still, the result was the same: Kenvue debuted into a much less welcoming market than the board likely imagined on announcement day.

The second lesson is the power—and the constraints—of tax-free structuring. A Section 355 tax-free spinoff can be an incredible value-unlocking tool, but it’s not a loophole you can just drive a truck through. The subsidiary has to be an active trade or business that’s been operating for at least five years. The deal needs a legitimate business purpose beyond avoiding taxes. And the parent generally has to distribute enough shares—typically at least eighty percent—to qualify. J&J’s choice to use an exchange offer instead of a simple pro-rata distribution made the separation more complicated, but it also gave shareholders something unusual: choice. Investors could decide whether they wanted to keep owning J&J, swap into Kenvue, or do some mix of both. That flexibility turned out to be popular.

The third lesson is about what happens to a stock when the “wrong” investors own it. In big spinoffs, the new company often inherits shareholders who never asked for it. Many J&J investors were there for pharma growth and medical device innovation, not a consumer staples business expected to grow in low single digits. When those holders sell—sometimes quickly, sometimes because their mandates require it—the stock can get hit by a wave of supply that has little to do with fundamentals. Historically, that kind of mismatch has created opportunities for patient, value-oriented investors willing to wait out the noise.

The fourth lesson is operational independence, and it’s a grind. A division can look self-contained on an org chart while still depending on the parent for the basics: IT systems, procurement, legal support, finance processes, and supply chain infrastructure. Transition Service Agreements are the bridge, but they’re also a meter that’s always running. Every month on a TSA is a month paying the parent for services while also spending to build replacements. Kenvue’s Vue Forward program was, in large part, an admission of urgency: the business needed to exit those agreements and stand up its own backbone faster—and at a lower cost—than the early post-IPO reality allowed.

The fifth, and most consequential, lesson is capital allocation. Independence forces immediate decisions: how much cash goes to dividends, how much to buybacks, how much to paying down debt, and how much to reinvesting in the brands. Kenvue planted a flag early as a dividend-paying stock, inheriting the legacy of Johnson & Johnson’s long streak of dividend increases—a record that made J&J a Dividend King. But a legacy isn’t the same thing as a guarantee. Whether Kenvue could sustain that kind of shareholder promise with slower growth and lower margins than its former parent was something the public markets would judge quarter by quarter.

Analysis and Investment Case

The Bull Case

The bullish view on Kenvue starts with a simple observation: these are some of the most ingrained brands in consumer health, sitting in categories people don’t “opt into” when times are good. They rely on them year-round. Pain relief, allergy meds, mouthwash, skincare, bandages—these are everyday utilities. Many of Kenvue’s franchises hold number-one or number-two positions, and that kind of shelf dominance tends to be self-reinforcing: retailers like the predictability, and consumers reach for what they already trust.

There’s also the shareholder angle. Kenvue inherited the expectations that come with Johnson & Johnson’s dividend legacy. Income-focused investors like that profile, and it puts a different kind of pressure on management: keep the cash flowing, protect the base business, and don’t gamble the franchise.

Then there’s execution. If Vue Forward delivers as planned, the story can shift from “spinoff growing pains” to “steady margin improvement.” In a business that doesn’t grow fast, cost structure is strategy. Kenvue has targeted $350 million in annual savings by 2026, and the appeal is less about any single number than what it represents: a credible path to running this portfolio leaner as a standalone company than it did inside a conglomerate.

Finally, there’s geography. Kenvue already sells globally, and international markets remain the most plausible place to find real volume growth—especially in categories like skin health and OTC self-care across parts of Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East.

If you map this to Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers, Kenvue’s clearest “power” is brand: the accumulated trust that makes a consumer pick Tylenol over acetaminophen, or Listerine over the cheaper bottle next to it. Scale is the supporting advantage—purchasing leverage, manufacturing footprint, and distribution reach that smaller competitors can’t easily match. Switching costs aren’t high for any one product, but they show up in the real world where it matters: retailers and pharmacies have planograms, traffic patterns, and shopper expectations built around these brands, and replacing them isn’t frictionless.

The Bear Case

The bear case is that Kenvue is the kind of business investors love in theory—stable, defensive, predictable—but struggle to love in practice when growth is slow and competition is relentless. These are mature categories. Since becoming independent, revenue has been basically flat. And because consumer health innovation is usually incremental, not transformative, Kenvue can’t count on a breakthrough product cycle to change the trajectory. It has to win the unglamorous way: defending share brand by brand, retailer by retailer, quarter by quarter.

The leadership shakeup didn’t help. A CEO departure less than two years after the IPO created uncertainty at a moment when Kenvue needed steadiness—internally, with employees still adapting to independence, and externally, with investors deciding whether to stick around.

And then there’s the headline gravity. Talc litigation is primarily a Johnson & Johnson liability under the indemnification agreement, but news coverage doesn’t always honor corporate boundaries. Every major verdict risks pulling Kenvue’s brands back into the same conversation about safety and trust—exactly the conversation the separation was supposed to escape.

Lastly, private label remains the quiet grinder. As retailers get better at marketing their own products, the price gap matters more, and the habit of trading down becomes easier to keep. That steadily erodes the pricing power Kenvue needs to protect margins.

Through a Porter’s Five Forces lens, this is a tough arena: rivalry is intense, retailer power is large and still growing, substitutes are everywhere (from private label to digital-native upstarts), supplier power is manageable, and barriers to entry are mixed—hard to build national distribution and credibility, easier than ever to launch a brand in one niche and scale it online.

The Kimberly-Clark Wildcard

Then came the curveball. On November 3, 2025, Kimberly-Clark announced a $48.7 billion offer for Kenvue—an offer that effectively rewrote the investment debate overnight. The deal valued Kenvue at $21.01 per share, a big premium to where the stock had been trading after sliding to an all-time low of $14.02 on October 30, 2025. The consideration was structured as $3.50 in cash plus 0.14625 shares of Kimberly-Clark for each Kenvue share.

On January 29, 2026, shareholders of both companies voted overwhelmingly to approve the transaction. Assuming it clears regulators—expected in the second half of 2026—Kenvue’s stint as a standalone public company would end barely three years after it began.

Strategically, the pitch is scale. The combined company would produce about $32 billion in annual revenue and $7 billion in adjusted EBITDA, with ten brands each doing more than a billion dollars in sales. Kimberly-Clark also pointed to a large synergy plan: $1.9 billion in cost synergies and $500 million in revenue synergies, offset by $300 million of reinvestment. The Federal Trade Commission is expected to scrutinize the deal, particularly in baby care and skin health where the portfolios overlap.

Key KPIs to Watch

Whether you’re tracking Kenvue on its own or trying to understand what the combined company might become, two metrics cut through the noise.

First: organic revenue growth. That’s the cleanest read on whether the brands are actually gaining or losing ground once you strip out currency and deal effects.

Second: adjusted gross margin. That’s where pricing power, input costs, and manufacturing efficiency all show up in one place.

Together, those two numbers tell you the real story: are the brands holding their pull, and is the company getting structurally better at turning that pull into profit?

Epilogue and Future Outlook

The wellness revolution isn’t slowing down. Across age groups and income levels, consumers have been spending more on health, skincare, and personal care—and they’ve been doing it with a different mindset than even a decade ago. Preventive health is no longer a niche idea. Self-care has become routine. And the demand has shifted toward products that feel both familiar and credible: brands you already trust, backed by claims that sound science-based rather than purely cosmetic. That environment plays to Kenvue’s core advantage.

The distribution landscape is shifting too. Telehealth and digital health platforms have become a new kind of front door for consumer health—places where people seek advice, get nudged toward an OTC solution, and then buy immediately. At the same time, emerging markets continue to represent the biggest long-term volume opportunity: as incomes rise, millions of consumers trade up from unbranded local options to globally recognized names. That dynamic has been one of the most durable growth engines in consumer staples, and Kenvue’s portfolio is built to compete for it.

Sustainability, meanwhile, has moved from “nice to have” to competitive requirement. Kenvue has committed to reducing its environmental footprint across packaging, sourcing, and manufacturing—exactly the sort of priorities younger consumers say they care about, and retailers increasingly demand. The open question is whether Kenvue can turn those commitments into a real edge, or whether they simply become the price of admission in a category where every major player is making similar pledges. In consumer brands, the difference is rarely the promise. It’s the follow-through.

And then there’s the fork in the road created by Kimberly-Clark’s offer.

If the acquisition closes as expected, Kenvue’s next chapter won’t be written by Kenvue alone. It will be defined by integration—by how well a consumer health portfolio gets absorbed into a larger company with deep expertise in tissue and hygiene. In the best case, the combination creates a broader personal care platform that spans everyday essentials, from baby care to adult skincare to oral health. In the worst case, it becomes a familiar mega-merger story: too many systems to unify, too many priorities to reconcile, and synergies that look cleaner on a slide than they do in real life.

If the deal doesn’t close—if regulators block it or conditions aren’t met—Kenvue snaps back to the question it has been living with since independence: can a collection of iconic, cash-generating, but mostly slow-growing brands create enough momentum, margin improvement, and investor confidence to thrive as a standalone public company? As usual, the answer isn’t philosophical. It’s operational. It comes down to execution.

Recent News

-

January 29, 2026: Shareholders of both Kimberly-Clark and Kenvue voted overwhelmingly to approve the proposals required for Kimberly-Clark’s $48.7 billion acquisition of Kenvue. The deal is still expected to close in the second half of 2026, pending regulatory approvals.

-

November 3, 2025: Kimberly-Clark announced it would acquire Kenvue for about $48.7 billion in cash and stock. Under the terms, Kenvue shareholders would receive $3.50 per share in cash plus 0.14625 shares of Kimberly-Clark for each Kenvue share—about a 46% premium to Kenvue’s pre-announcement price.

-

November 2025: After serving as interim CEO since July, Kirk Perry was appointed permanent CEO of Kenvue.

-

July 14, 2025: Kenvue announced that CEO Thibaut Mongon would depart. Kirk Perry was named interim CEO, and the company said it would begin a comprehensive review of strategic alternatives.

-

December 2025: A Maryland jury ordered Johnson & Johnson and Kenvue to pay $1.56 billion to a plaintiff in a talc-related cancer case—the largest individual verdict in fifteen years of talc litigation.

-

Q3 2025: Kenvue reported adjusted EPS of $0.28, topping analyst expectations, and reaffirmed its full-year 2025 adjusted EPS outlook of $1.00 to $1.05.

Links and Resources

- Kenvue Investor Relations

- Kenvue CEO Transition Announcement

- Kimberly-Clark Acquisition Announcement

- Shareholder Approval of Acquisition

- Kenvue Full Year 2024 Results

- Kenvue Q3 2025 Results

- CNBC: Kimberly-Clark Agrees to Buy Kenvue

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music