Koppers: The Hidden Guardian of Infrastructure

I. Introduction: The "Unsexy" Empire

Picture a freight train cutting through the American heartland at midnight, hauling grain from Kansas to a port in Louisiana. Under those steel wheels sits the unglamorous workhorse of the rail network: thousands of wooden crossties—chemically treated timber built to survive decades of punishment from rain, heat, ice, and vibration.

Now shift scenes. Along a rural highway in Alabama, a long line of utility poles holds up the wires that keep refrigerators cold and hospitals bright. And halfway around the world, inside an aluminum smelter in Australia, carbon anodes made from a black, tar-derived material called pitch help turn raw inputs into the lightweight metal in your smartphone casing.

Three totally different worlds. One quiet connective tissue.

Koppers.

Most investors have never heard the name. Yet Koppers sits in the background of the modern economy, supplying products so essential that if they disappeared, huge pieces of daily life would start failing in very physical ways: tracks would degrade, poles would rot, and key industrial processes would seize up. The company is based in Pittsburgh, headquartered in a 1920s art-deco skyscraper fittingly called Koppers Tower. It’s not a household name. But it is, in its niches, foundational.

In North America, Koppers is the largest provider of railroad crossties for the Class I railroads, known for pre-plated crossties. More broadly, its products help hold up the railroad network, keep electricity flowing, and protect outdoor wooden structures Americans barely think about—backyard decks, fencing, and more.

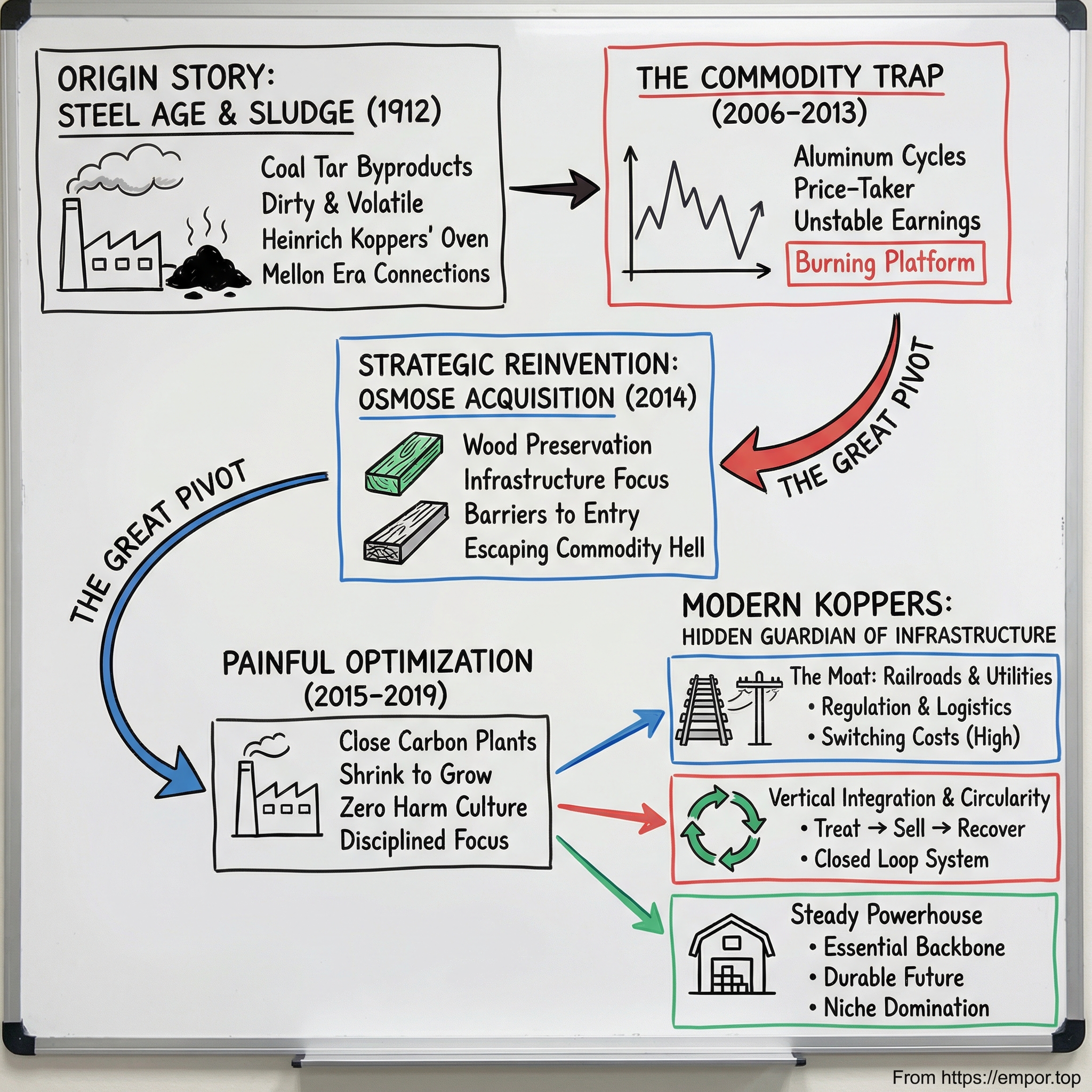

And that sets up the paradox at the heart of this story: Koppers was born in the early 1900s in the “dirty” world of coal and steel—processing the messy byproducts of steel manufacturing. So how did that kind of company not only survive, but build a future, in an era increasingly defined by ESG scrutiny and climate concern?

The answer is a strategic reinvention. Over the past decade, Koppers transformed itself from a volatile, commodity-exposed processor into something much more durable: a specialized guardian of infrastructure, operating in markets with real barriers to entry.

To understand why that pivot is so powerful, you have to start at the beginning. In the early 1900s, German engineer Heinrich Koppers developed a new kind of coke-oven furnace that recovered valuable byproducts instead of venting them into the air. In modern terms, it was an early form of industrial recycling—capturing “waste” and turning it into inputs for other industries. That instinct became Koppers’ DNA.

Coal tar—thick, sludgy residue from steelmaking—could be distilled into creosote to preserve railroad ties and into carbon pitch used in aluminum production. The company’s identity was built around that idea: take what other industries discard, and make it indispensable.

But here’s the twist: this isn’t really a story about chemicals. It’s a story about escaping what investors call “Commodity Hell”—the trap of being a price-taker, where your profits rise and fall based on forces you can’t control. Koppers lived there for a long time. It made money, sure, but it got yanked around by cycles, input costs, and global industrial demand.

Then came the realization: the old model wasn’t just volatile; parts of it were in structural decline. And that forced a hard, defining question—could Koppers redesign itself around businesses where it could actually control its destiny?

The thesis is simple: through smart acquisitions, painful divestitures, and a serious operational transformation, this century-old industrial company repositioned itself as an irreplaceable link in America’s infrastructure supply chain—protected by regulation, entrenched customer relationships, and vertical integration that competitors can’t easily replicate.

Now, let’s go back to the soot and the steel, and trace how Koppers got here.

II. History: The Mellon Era & The Coke Kings (1912–1980s)

The story begins in the industrial chaos of early twentieth-century America, when steel was king and Pittsburgh was its throne room. In 1912, a German immigrant engineer named Heinrich Koppers founded the Koppers Company in Chicago. He wasn’t just building another industrial supplier. He had a genuine breakthrough: a coke oven designed to capture valuable byproducts that everyone else simply burned off or vented away.

To see why that mattered, you have to understand how steel worked back then. Steel started with heat—enormous, relentless heat—and that heat came from coke: coal baked until it became a dense, energy-rich fuel. The old coking process did the job, but it was wildly wasteful. As coal cooked, it gave off gases, tar, and chemical compounds that were literally treated like exhaust.

Koppers’ innovation flipped that on its head. His ovens didn’t just make coke; they recovered coal gas, coal tar, and other chemicals as usable products. In today’s language, it was an early form of industrial recycling: turn a toxic, messy byproduct stream into a second profit engine. That idea—extract value from what everyone else discards—would become the company’s defining instinct.

At first, Heinrich Koppers ran much of the operation from Germany. But American industry was moving too fast, and the gravitational pull of U.S. capital was too strong. After discussions with U.S. Steel representatives as early as 1907, Koppers agreed to build a coke plant in the United States. The company was formally incorporated in 1912. Two years later, Koppers sold his controlling stake to a group of investors that included Andrew Mellon and H. B. Rust, and the headquarters moved from Chicago to Pittsburgh—right into the center of America’s industrial power base.

That Mellon connection is a big deal. Andrew Mellon wasn’t a passive investor; he was a builder of empires. Born in 1855 in Pittsburgh, he rose to lead the family bank and methodically assembled stakes across heavy industry—Union Steel, Gulf Oil, and eventually Koppers. He would later become U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, but long before that, he was one of the men wiring together the industrial economy. With Mellon involved, Koppers wasn’t just a clever engineering shop anymore. It was plugged into the region’s money, influence, and corporate network.

In the 1920s, that network expanded further. Henry B. Rust worked to assemble a consortium that could integrate large pieces of the coal economy, and he sought support from Mellon. The result was a web of holding companies that touched mining, rail transportation, shipping, utilities, and steel mills. Koppers fit naturally into that ecosystem: it was the company that could take coal’s dirtiest leftovers and make them profitable.

And that became the business model—simple in concept, hard in execution. Koppers took coal tar, the nasty sludge left after coal was coked, and distilled it into products industry couldn’t function without. Carbon pitch became a critical binder in the anodes used for aluminum smelting. Creosote became the preservative that kept wood from rotting in the ground—railroad ties, utility poles, and marine pilings. Other outputs—like naphthalene and carbon black feedstock—fed into plastics, resins, concrete additives, and rubber. The point wasn’t just that Koppers made chemicals. It was that it sat at an intersection of supply chains: steelmaking waste became inputs for aluminum, infrastructure, and manufacturing. And the primary raw material underneath it all was coal tar.

By 1929, Koppers’ prominence was literal and physical. The company opened the landmark Koppers Building—an art-deco tower that still defines part of Pittsburgh’s skyline—a sign that Koppers had joined the city’s industrial aristocracy.

World War II pushed the company further into the national spotlight. In 1943, at the U.S. government’s request, Koppers built a factory in Kobuta, Pennsylvania, on the Ohio River downriver from Beaver, to manufacture styrene-butadiene monomer—an input used to make synthetic rubber for the war effort. Koppers wasn’t just a supplier to industry anymore; it was part of the country’s strategic manufacturing base.

After the war, like many industrial giants, Koppers sprawled. It expanded into plastics, road paving, and a mix of other businesses. Over time, it started to look less like a focused specialist and more like a classic mid-century conglomerate—pulled in different directions, exposed to cycles, and often defined by whatever capital spending boom was happening at the moment.

By the 1980s, that kind of sprawl wasn’t seen as a strength. It was seen as an opportunity—for corporate raiders.

In early 1988, Beazer, a British conglomerate led by one of the era’s most aggressive dealmakers, launched a hostile takeover for $1.81 billion (about $5 billion today). The sale closed on June 17, 1988.

The fight got intensely public. Koppers’ CEO, Charles Pullin, went on the offensive, casting the deal as an attack on a venerable American company. But the outrage didn’t stop at Beazer. Pullin aimed much of his fire at Shearson and American Express—American Express owned 62 percent of Shearson, and Shearson had helped finance the bid. The backlash was real: Koppers officials and other Pennsylvanians cut up their American Express cards, the state’s political leaders condemned the deal, and Shearson reportedly lost an estimated $7 billion of business in Pennsylvania.

Still, money talks. When Beazer raised its offer from $45 to $61 per share—roughly four times Koppers’ book value—the resistance collapsed. The board accepted the bid.

But that wasn’t the end of the Koppers story—it was a forced reset. Later in 1988, a smaller and more streamlined domestic business unit—Koppers Industries—was bought back by local management. It was a far cry from the sprawling conglomerate of earlier decades, but it restored a measure of focus and returned the company to what it could do best.

What emerged was leaner and more coherent. It was also still tethered to volatile commodity forces that had shaped Koppers from the beginning. The real reinvention—the one that would change the company’s destiny—was still ahead.

III. The "Burning Platform": Life as a Commodity Broker (2006–2013)

On February 1, 2006, Koppers Holdings Inc. stepped back onto the public stage. It priced its initial public offering at $14 per share for 10 million shares, raising about $140 million, and began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker KOP.

But the company investors were buying wasn’t the steady, infrastructure-anchored Koppers you might imagine today. It was a business still tied to the same gritty root system it had always had: coal tar.

At the center of the newly public company was its Carbon Materials and Chemicals segment—distilling coal tar into carbon pitch, creosote, naphthalene, and other byproducts. And while that sounds specialized, it behaved like a commodity business. In practice, Koppers’ fortunes were chained to a single global heartbeat: aluminum production. When smelters were running hot, demand for pitch surged. When smelters slowed, Koppers felt it immediately.

That dependence exposed a deeper problem: this wasn’t just normal industrial cyclicality. The economics were stacked against them.

On the way in, Koppers had to buy coal tar from steel mills and compete with other distillers for supply. On the way out, it had to sell into global markets where pricing was set by forces far beyond Pittsburgh—especially as new capacity, including from China, came online. Koppers could run world-class operations and still get whipsawed by variables it couldn’t control.

Then the 2008 financial crisis hit and made the risk impossible to ignore. Carbon Materials and Chemicals sales fell hard—down 27%, or $237 million, year over year—driven by lower volumes across major product lines as the global economy contracted. Meanwhile, Railroad and Utility Products barely moved, with sales down just 1%, or $4 million. Net income told the story even more starkly: it dropped from $138 million in 2008 to $18.8 million in 2009.

Inside the company, the lesson was brutal and simple. They were running on a treadmill with no off switch. When the economy was strong, raw material costs could spike as steel production rose. When the economy weakened, demand vanished. Either way, Koppers struggled to capture much upside—while absorbing the full force of the downside.

Public markets don’t reward that kind of profile. Investors treated Koppers like what it was at the time: a volatile, commodity-exposed processor. The stock traded at depressed earnings multiples, and management fielded pointed questions about the instability of the carbon business. The company could be profitable, but the earnings quality was shaky—and the market priced it accordingly.

So the tension at the heart of Koppers’ story sharpened: they needed an escape route from commodity hell. A business less exposed to global aluminum cycles and coal tar pricing. Something with steadier demand, stickier customers, and margins they could defend.

That escape hatch would come from an unlikely place: wood preservation chemicals.

IV. The Great Pivot: The Osmose Acquisition (2014)

In April 2014, Koppers announced the move that would redefine the company. It signed an agreement to acquire Osmose Holdings’ Wood Preservation and Railroad Services businesses—the “Acquired Businesses”—for a base purchase price of $460 million, subject to closing adjustments.

To see why this mattered, you have to understand what Osmose actually was. Its Wood Preservation business was a global leader in developing, manufacturing, and marketing wood preservation chemicals and wood treatment technologies. It operated and sold products across North America, Latin America, Europe, and Australasia, and in 2013 it generated roughly $350 million of revenue within the Acquired Businesses. Just as important: its end markets weren’t a single industrial heartbeat like aluminum. They spanned infrastructure, residential and commercial construction, and agriculture.

For Koppers, that changed the story in three big ways.

First, it broadened the company’s center of gravity from “heavy industrial” into residential and infrastructure. Osmose’s copper-based preservatives went into the lumber that becomes decks, fences, and other outdoor structures. That meant Koppers could participate in demand streams driven by homebuilding and everyday maintenance—not just steel and smelters.

Second, it diversified Koppers away from coal tar. Copper-based systems rely on different inputs entirely, so this wasn’t just “more volume.” It was a hedge against the very commodity volatility that had kept Koppers trapped for years.

Third—and this was the strategic masterstroke—it pushed Koppers further up and down the value chain. Koppers already knew treated wood cold. It treated railroad ties at scale, using preservatives it understood deeply. Now it would also own a major platform for producing the copper-based chemicals used to treat residential lumber. More of the economics, more of the customer relationship, more control.

The company expected the acquisition to contribute more than $400 million in sales, with EBITDA margins anticipated to be above its 2015 target level of 12%. To finance the deal, Koppers put new capital in place alongside closing: a $300 million Term Loan A with a five-year amortization period and an expanded revolving credit facility of $500 million, up from $350 million.

The deal closed in August 2014. Koppers announced it had completed the acquisition and framed it as a centerpiece of its long-term growth strategy: the businesses fit Koppers’ core competencies, expanded its chemicals offering and its railroad and utilities platform, and opened up additional growth avenues. Management also projected synergies of at least $12 million, with the annual run rate expected to be achievable by the end of 2015.

On the outside, the initial reaction was skepticism. Why was a coal-tar-and-steel-adjacent chemicals company buying into residential wood preservation? The leverage looked heavy, and the integration risk was real—two different operating models, two sets of systems, two cultures that didn’t naturally rhyme.

But management believed the market was missing the point. The Osmose wood preservation business had what Carbon Materials didn’t: steadier demand, recurring relationships, and real barriers to entry. You can’t simply decide to build a competing preservatives platform. Products require extensive testing and EPA registration, and customers value consistency, technical support, and trust built over years. In other words, this wasn’t just an acquisition. It was an exit ramp from commodity hell.

V. Optimization & Pain: Shrinking to Grow (2015–2019)

The Osmose deal closed at exactly the wrong moment—at least if you were still judging Koppers by its old carbon business. The carbon materials markets rolled over again. Aluminum prices fell, Chinese overcapacity squeezed the system, and coal tar supply tightened as steel production patterns shifted globally. Suddenly, the leverage Koppers took on to buy Osmose didn’t look like a bold pivot. It looked like a weight.

This was the handoff to a new era of leadership. In January 2015, Koppers announced that Leroy Ball would become President and Chief Executive Officer as part of its long-term strategic planning process. Ball had been elected Chief Operating Officer in May 2014, overseeing global operations, and before that he’d served as CFO since August 2010.

He wasn’t an old-school plant guy. Ball came up through finance, including eight years as CFO of Calgon Carbon, a company focused on purifying water and air. He held an accounting degree from Florida International University and an MBA from Robert Morris University. But that finance-first mindset turned out to fit the moment. Koppers didn’t need a cheerleader for the legacy business. It needed someone willing to do the unpleasant math, then act on it.

Ball and his team made the call: the carbon footprint had to shrink—fast. Koppers announced it would close three more tar distillation facilities in the UK, China, and the U.S., part of a restructuring designed to cut the global Carbon Materials and Chemicals footprint from 11 facilities down to four by the end of 2016.

The reasoning was blunt. Primary aluminum production was migrating to regions with cheaper energy, and that shift helped create overcapacity in tar distillation across the U.S. and Europe. At the same time, coal tar supply in the UK had fallen significantly. Koppers said it was “significantly transforming its business model” by streamlining its operating footprint and reducing its reliance on— and exposure to—carbon pitch markets.

The UK operations were especially painful. Exiting production at Port Clarence wasn’t about a big payday; the company said the sale price and earnings contribution weren’t material. It was about eliminating operational risk and forcing focus—re-centering the European manufacturing base around Nyborg, Denmark, instead of trying to keep every legacy site alive out of habit.

While the footprint was being cut down, the culture was being rebuilt. During this period, Ball pushed what became known as “Zero Harm”—a shift in how Koppers talked about, measured, and ran the business. The stated commitment was straightforward: put the health, safety, and well-being of employees, the environment, and surrounding communities first. Koppers pointed to measurable improvements in safety performance and financial results after implementing the program, and positioned Zero Harm as the foundation for operating successfully in a “dynamic environment.”

There were tangible markers behind the messaging. In 2015, Koppers received certification at 18 facilities and its corporate headquarters under the American Chemistry Council’s Responsible Care program. In a company with deep roots in gritty heavy industry, this signaled something real: a move away from “get it done” industrial bravado toward disciplined, compliance-driven operational excellence.

And slowly, the shape of the company began to change.

The restructuring hurt, but it did what it was supposed to do. As Koppers reduced its exposure to the volatile Carbon business and leaned harder into Performance Chemicals and treated-wood markets, the earnings profile started to look different. Less tied to aluminum cycles. Less at the mercy of commodity pricing. More like a business that could grind forward—steadily—year after year.

VI. The Moat: Railroads and Regulation

To understand Koppers’ competitive position today, you have to understand the strange, unforgiving economics of railroad crossties.

In North America, the big rail networks—Union Pacific, BNSF, CSX, Norfolk Southern, Canadian National, Canadian Pacific Kansas City, and Amtrak—function like regional monopolies. They own the tracks. They maintain the tracks. And beneath every mile of rail is a consumable that quietly determines whether trains run smoothly or not: treated wooden ties designed to survive decades of vibration, moisture, heat, and freeze-thaw cycles.

Koppers sits right in the middle of that system. It’s been the largest provider of pressure-treated railroad crossties for the Class I railroads in North America for more than 25 years. The job sounds straightforward—treat wood so it lasts longer—but the implications are massive. Longer-lasting ties mean fewer replacements, fewer service disruptions, and less demand for fresh timber. Koppers frames this as a durability-and-sustainability story: extending tie life out toward decades, reducing replacement cycles, and improving the reliability of wood products in the field.

And then there are the switching costs. On paper, a crosstie is a commodity. In reality, changing suppliers is a headache railroads will go out of their way to avoid.

Ties are heavy, bulky, and not worth much per pound, which means logistics—not chemistry—often decides who wins. Railroads need suppliers with treating plants positioned close to their networks, enough inventory to absorb seasonal spikes, and the operational discipline to never leave a maintenance crew short. Koppers has built that supply chain over time, with a sawmill provider network that sources ties and switch ties from more than 125 independently owned sawmills. Those relationships matter because consistency matters: consistent raw material supply, consistent treatment quality, consistent delivery.

But the biggest wall around the castle isn’t logistics. It’s regulation.

Operating a wood-treating facility with creosote or other preservatives means living inside a tight cage of EPA and state environmental permits. These are not easy to get—especially for new facilities. Creosote is a known carcinogen, and handling it demands serious environmental controls, monitoring, and compliance systems. Over time, that reality has created a quiet form of “regulatory scarcity”: existing operators that maintain permits and run compliant plants effectively become entrenched, while potential new entrants find the barriers punishingly high.

Koppers also increasingly sells something more than a product. It sells a system.

Instead of treating a tie and walking away, the company has been building a circular, end-of-life solution—recovering ties when they’re pulled from the track, grading them, and then routing them to their next destination. Some recovered ties can be resold into agricultural or building uses. The rest can be processed into biomass fuel used to generate power for certain industrial facilities. Through December 31, 2027, KRR will collect and grade ties at the end of their useful life. With that agreement, Koppers said it serves four of the six Class I railroads, and it has continued exploring ways to grow its presence.

This “closed loop”—treat, sell, recover, repurpose, and convert what’s left into energy—creates stickiness that a pure product supplier can’t match. It also helps solve a real problem railroads have to manage: what to do with treated wood at end of life. If Koppers can make disposal and recovery easier, it becomes a better long-term partner—especially as customers put more weight on sustainability reporting.

To support that broader offering, Koppers has invested in capacity and recovery. It modernized and expanded its treatment facility in North Little Rock, Arkansas, which it estimated—once fully operational—could treat nearly 20% of the annual Class I tie market. The company also invested $65 million in its Recovery Resources business, which focuses on reusing, repurposing, or recycling ties as they reach the end of their service life.

All of that would already be a formidable moat. But Koppers has another engine alongside rail: Performance Chemicals, the copper-based preservatives used in residential and commercial lumber.

This is the side of the company that looks least like “old Koppers” and most like a modern specialty chemicals platform. Koppers Performance Chemicals is a global player in wood preservative systems and technologies, supported by wood science expertise and long-standing customer relationships. Beyond preservatives, it provides fire retardants, engineering services, and marketing support to help customers sell treated-wood products into their markets. In the post-pivot Koppers story, this segment became the steady cash generator—helping fund debt paydown and giving management room to keep investing in the infrastructure moat.

VII. Analysis: The 7 Powers & 5 Forces

If you run Koppers through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers, something interesting happens. What looks, from a distance, like an old industrial company starts to read more like a company with real, durable advantages—advantages that come from being hard to replace, hard to replicate, and hard to regulate.

Cornered Resource: Koppers’ most valuable scarce asset isn’t a plant or a formula. It’s permission. The ability to operate wood-treatment facilities that use creosote and other EPA-regulated chemicals is a resource you don’t simply go out and rebuild. New entrants face long timelines, heavy environmental scrutiny, and often intense local opposition. In practice, the companies that already hold the permits have cornered something scarce. On top of that, Koppers’ coal tar distillation capacity adds another layer of advantage—access that would take major capital and years of work for a would-be competitor to recreate.

Switching Costs: For Class I railroads, changing crosstie suppliers is not like switching office vendors. It’s a logistical operation. Deliveries have to hit the right places, on the right schedule, to match maintenance-of-way planning. Quality has to be consistent. A supply disruption isn’t just inconvenient—it can ripple into missed track time and operational headaches. Koppers’ network of treatment plants, built and located over decades to serve specific corridors, lowers that risk for customers. That’s the switching cost: not just price, but reliability, geography, and execution.

Process Power: Koppers doesn’t just treat wood. It increasingly controls the workflow around treated wood. It produces preservatives (including creosote from the Carbon Materials and Chemicals business), treats ties and poles through Railroad and Utility Products, and handles end-of-life solutions through its Recovery Resources business. That vertical integration creates efficiencies and coordination a more “single-step” competitor can’t match. Koppers has described itself as the only vertically integrated wood treatment and utility pole producer in the world—controlling the chain from inputs to a finished, treated product. And importantly, the Railroad and Utility Products business serves non-discretionary, long-life infrastructure markets. Railroads need ties. Utilities need poles. That demand doesn’t disappear just because housing slows.

Porter’s Five Forces adds another lens:

Threat of New Entrants: Low. Environmental permitting and liability make new creosote treating capacity exceptionally hard to stand up. You need capital, time, and a risk tolerance most companies—and communities—don’t have. The industry consolidated for a reason: it’s far easier to buy or inherit these capabilities than to start them from scratch.

Threat of Substitutes: Medium. Concrete ties are real, and they’re used in certain settings, but wood still dominates in U.S. rail because it’s cost-effective, easier to install, and performs well under load and temperature swings. Composites are a longer-term question mark, but adoption has been slow. In residential construction, alternatives exist too, yet treated wood remains the practical choice for decks, fences, and outdoor structures in many markets.

Supplier Power: High. Koppers relies on upstream supply—steel mills for coal tar, and timber supply for ties and poles. As domestic steel dynamics change, coal tar availability can tighten, which gives suppliers leverage. On the wood side, Koppers moved to reduce vulnerability by acquiring Gross & Janes in 2022, a major independent supplier of untreated crossties. Gross & Janes, headquartered in Kirkwood, Missouri, operates in Arkansas, Missouri, and Texas and reported about $50 million in annual sales in 2021. Koppers’ rationale was direct: strengthen the vertical model and de-risk supply for customers’ critical infrastructure needs.

Buyer Power: High. The Class I railroads are few, large, and sophisticated—exactly the kind of customers that can push hard on pricing and terms. But that power is moderated by switching costs and the operational complexity of tie supply. In Performance Chemicals, the customer base is more fragmented, which reduces concentration and shifts some leverage back toward the supplier.

Competitive Rivalry: Low/Oligopolistic. Railroad crosstie treatment in North America has consolidated into a small set of serious players, with Koppers and Stella-Jones as the dominant suppliers. Competition exists, but it’s constrained by the same factors that keep new entrants out: permits, geography, logistics, and customer risk. Performance Chemicals is more competitive, but Koppers’ scale and technical capabilities give it room to differentiate.

VIII. Playbook: Lessons for Builders & Investors

Koppers is a useful case study because the plot isn’t “invent a new product.” It’s “change the business you’re actually in.” Here are the lessons hiding in plain sight:

Escaping the Value Trap: Plenty of industrial companies look cheap. The hard part is telling the difference between “cheap because it’s broken” and “cheap because it’s mid-transformation.” Koppers from 2006 to 2014 was cheap for a reason: its earnings were tied to volatile carbon markets, which made the stock hard for many long-term, institutional investors to own with conviction. Post-2015, the company started to look like something else entirely—a business deliberately reallocating capital away from its weakest exposure and toward steadier, more defensible demand. The takeaway isn’t “buy cheap.” It’s “buy the pivot,” especially when management is willing to shrink legacy operations rather than endlessly optimize them.

Niche Domination Over Scale: You don’t need to be Nvidia to build a great business. Koppers shows what happens when you dominate narrow, essential markets—railroad crossties, utility poles, and wood preservation chemicals—where “good enough” isn’t good enough and where the constraints are real. The trick is picking niches protected by regulation, technical know-how, and geography, not just niches that are small and messy.

The "Dirty" Moat: The unsexy, compliance-heavy businesses often have the strongest defenses. Koppers operates in a world of creosote, coal tar derivatives, and treated wood—products that come with environmental scrutiny, permitting complexity, and real operational responsibility. Those burdens are also a filter: they keep out casual entrants and deter competitors that don’t want the risk profile. The lesson is counterintuitive but powerful: sometimes the headache is the moat.

M&A as Strategic Transformation: The Osmose acquisition wasn’t “bolt-on growth.” It was a deliberate change in business model—using acquisition to shift the company’s center of gravity toward markets with steadier demand and stronger defensibility. And the strategy didn’t stop there. In 2022, Koppers acquired Gross & Janes to reduce supply chain vulnerability. In 2024, it acquired Brown Wood Preserving Company and certain of its affiliates for approximately $100 million in cash, expanding utility pole capacity. Brown Wood manufactures and sells pressure-treated wood utility poles, and the transaction is expected to contribute $15 million to $25 million in EBITDA in 2025.

Key Metrics to Watch: If you’re tracking whether the transformation is working, two measures do most of the heavy lifting:

-

Adjusted EBITDA Margin by Segment: This shows whether the company keeps shifting from more volatile Carbon Materials and Chemicals toward Railroad and Utility Products and Performance Chemicals—and whether those segments are converting operational discipline into real profitability.

-

RUPS Segment Crosstie Volume: This is the heartbeat of the railroad business—the steady demand base that supports the broader enterprise and funds reinvestment.

For context on the overall earnings engine, Koppers reported 2024 adjusted EBITDA of $261.6 million, up from $256.4 million the prior year.

IX. Conclusion & Forward Outlook

Koppers today barely resembles the company that went public in 2006. Back then, the story revolved around coal tar and the global aluminum cycle. Today, it’s a critical mid-cap supplier to the physical systems that keep modern life running. Roughly three-quarters of the business now ties back to wood preservation, and about three-quarters of operations sit in North America—closer to the rail networks, utility grids, and construction markets that drive demand.

Management has told investors to expect continued progress. Even with a competitive market, a shaky global economy, and plenty of uncertainty in the background, Koppers has guided to 2025 sales of about $2.17 billion, up from $2.09 billion in 2024. It expects adjusted EBITDA of about $280 million in 2025, and adjusted EPS of $4.75 per share, versus $4.11 per share in 2024.

The optimistic view is straightforward. America’s infrastructure needs work—lots of it. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law earmarked $66 billion for rail projects, the largest investment in passenger rail since Amtrak’s creation. Utilities are hardening the grid against extreme weather and modern threats, which ultimately means more poles, more replacements, and more maintenance. And railroads don’t get to “pause” upkeep when the economy slows; ties still rot, track still shifts, and networks still have to run.

Koppers sits right in the slipstream of that spend. It’s the largest provider of railroad crossties and a major utility pole supplier, exactly where infrastructure dollars tend to turn into orders. Recent moves reinforce that positioning: Brown Wood added utility pole capacity in regions with growth, and Gross & Janes helped secure supply of untreated crossties. Alongside that, the company has been pushing its “Catalyst” transformation program to lift margins and tighten execution, including creating a new role to oversee the initiative and naming James A. Sullivan President and Chief Transformation Officer.

The cautious view is just as real. A recession can slow homebuilding, which hits demand for residential lumber and the preservatives used to treat it. Coal’s long-term decline can tighten coal tar availability—the key input for creosote and carbon pitch. If domestic steel production continues to shrink or shift, Koppers could face raw-material constraints that pressure margins or force more consolidation.

There’s also the slow grind of substitution. Concrete ties haven’t replaced wood ties in North America, but technology rarely asks permission. If composites or alternative systems gain broad acceptance, Koppers’ position could weaken over time. And the same regulatory barriers that protect the company can also punish it: tighter standards can raise compliance costs, and in extreme cases could force facility changes or closures.

What makes Koppers unusual is that the reinvention isn’t theoretical—it already happened. This is a century-old industrial company that escaped commodity hell by reallocating capital, shrinking what needed to shrink, and building around durable infrastructure demand. The moats are tangible: permits that are hard to replicate, switching costs that are logistical and operational, vertical integration that simplifies life for customers, and a footprint positioned where the work has to be done.

In the end, Koppers is the ultimate pick-and-shovel play on American infrastructure—if the “shovel” is a chemically treated piece of timber designed to last for decades. Freight trains crossing the plains, power lines reaching rural communities, backyard decks that survive year after year of weather—all of it depends, in small but essential ways, on what this quiet Pittsburgh company has been making for more than a hundred years.

X. Sources & Further Reading

This story was built from the paper trail: Koppers’ SEC filings (10-Ks and 10-Qs), investor presentations, and earnings call transcripts. A few sources were especially useful:

- Koppers 2014–2016 Investor Day presentations that lay out the logic and mechanics of the pivot

- The Senator John Heinz History Center archives, which include historical Koppers Company records

- Railway Tie Association publications on the North American wood crosstie market

- American Chemistry Council Responsible Care materials related to safety and operating standards

If you want the wider backdrop—the Pittsburgh industrial machine that made companies like Koppers possible—there are many strong histories of Andrew Mellon and the web of capital and industry that shaped the region. Koppers’ arc, from steel-age byproducts to modern infrastructure preservation, makes the most sense when you see it as part of that bigger Pittsburgh story: rise, disruption, and reinvention.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music