Kennametal Inc.: Cutting Through a Century of Manufacturing

I. Introduction: The Hidden Infrastructure of Industrial Power

Picture the scene: a Boeing 787 Dreamliner rolls down the final assembly line in Everett, Washington. Titanium brackets. Precision-machined aluminum panels. Engine mounts built to tolerances so tight they feel like magic. None of that shape appears on its own. It’s carved out of stubborn, expensive metals by cutting tools most passengers will never think about.

Somewhere in that chain of work is a small, unglamorous hero: a tungsten carbide insert. It’s brutally hard, engineered to keep its edge while chewing through exotic aerospace alloys at speeds that would’ve sounded like science fiction not that long ago.

And there’s a decent chance it has Kennametal stamped on it.

For more than 80 years, Kennametal Inc. has been an industrial technology company built around one idea: if you can master materials science, you can make manufacturing dramatically more productive. It sells cutting tools and wear-resistant components that customers rely on every day across aerospace and defense, earthworks, energy, general engineering, and transportation.

This is a business that sits right at the intersection of metallurgy, manufacturing, and margins—literally making the tools that make everything else. When a mining operation in Australia needs components that can survive rock, heat, and nonstop abrasion, Kennametal is in the mix. When an automotive plant in Germany is machining engine blocks at relentless cycle times, Kennametal’s inserts are doing the cutting. When an oil and gas operator is drilling through miles of rock, specialized tooling is grinding away deep underground.

And yet, outside of industrial circles, Kennametal is nearly invisible. It doesn’t sell to consumers. It doesn’t have a lifestyle brand. No Super Bowl commercials. No sleek product launches. But it does have scale: about 8,400 employees supporting customers in nearly 100 countries, and around $2 billion in fiscal 2024 revenue.

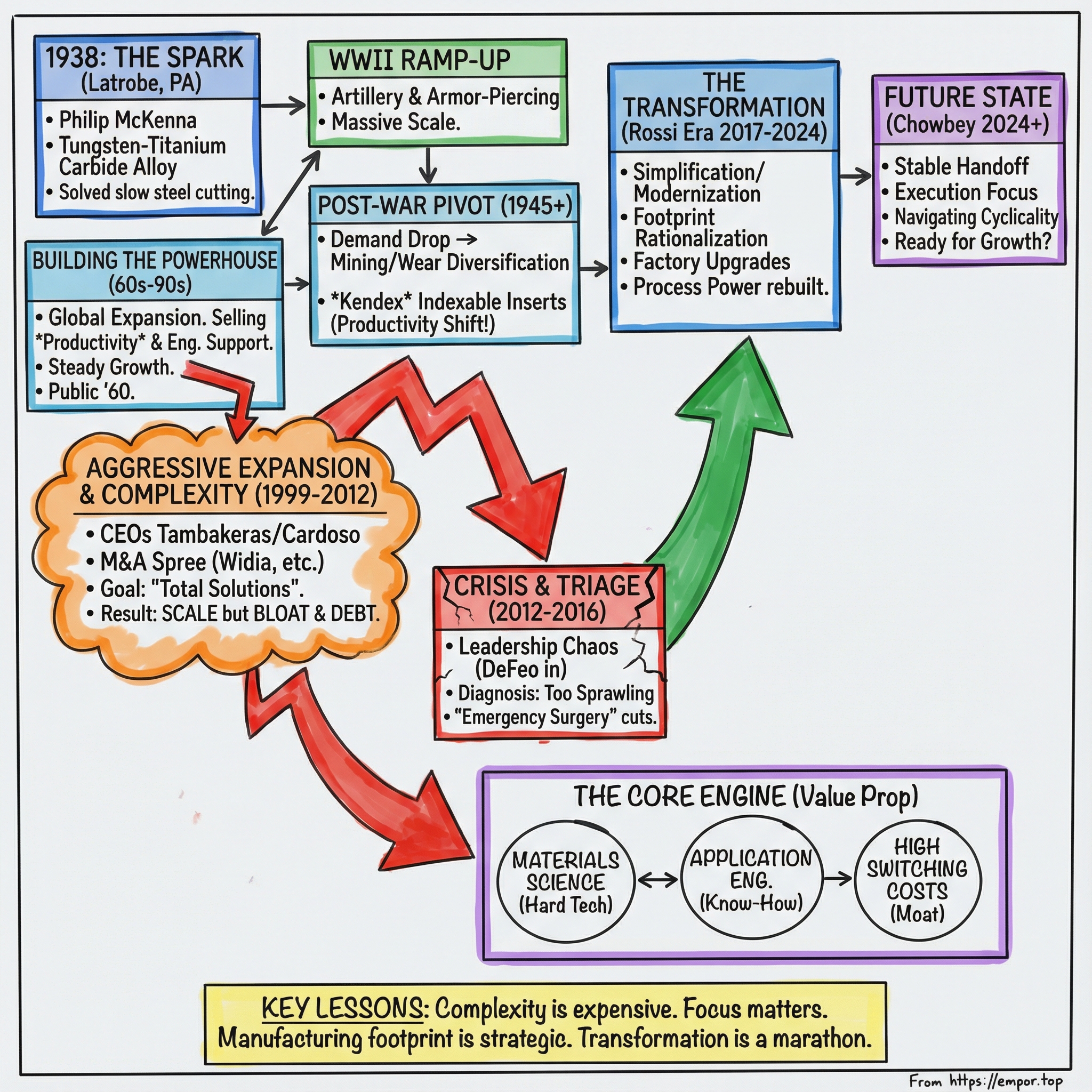

Understanding Kennametal is a way of understanding how the physical world actually gets built—and why some industrial companies endure for generations while others get commoditized and disappear. Over 85 years, Kennametal went from a Depression-era startup in rural Pennsylvania to a global supplier that major manufacturers depend on. Along the way, it learned the hard lessons of cyclicality, focus, and what it really takes to build a moat in specialized, high-stakes markets.

In a sense, Kennametal’s story tracks the story of American manufacturing itself: the breakthroughs, the boom years, the globalization, the stumbles, and the reinvention. And like so many great industrial stories, it starts with a breakthrough material—and the person who recognized what that material could do.

II. Founding Context & The Tungsten Carbide Revolution (1938–1960s)

It was 1938, and the U.S. was still clawing its way out of the Great Depression. In Latrobe, Pennsylvania—a small steel town in the hills east of Pittsburgh—a metallurgist named Philip McKenna set out to solve a problem every machinist understood in their bones: cutting steel fast enough to matter, without destroying the tool in the process.

For decades, manufacturers had relied on high-speed steel cutting tools. They worked, but they came with a built-in tax on productivity. Push them too hard and they overheated. Edges softened. Tools wore out. And every worn tool meant the same thing: stop the line, swap the tool, start again. The tool itself wasn’t always the big cost. The downtime was.

McKenna’s answer was materials science. After years of research, he developed a tungsten-titanium carbide alloy for cutting tools that delivered a genuine step-change in machining productivity. The company’s early flagship product—called, simply, “Kennametal”—was described as “much harder than the hardest tool steel,” enabling high-rate steel cutting that hadn’t been practical before.

That breakthrough wasn’t a lucky lab accident. McKenna had grown up with heat, sparks, and steel filings. Born in 1897, he was introduced to metallurgy early by his father, A.G. McKenna. By age seven, Philip was stoking the fire for his father’s blacksmith forge, watching drill steels heat and change. By 1907, he could run a lathe. In high school, he was skilled enough to make a true-tempered hunting knife on his own. This was hands-on metallurgy—earned the hard way.

Professionally, McKenna had deep credentials too. His father founded Vanadium Alloys Steel Company (VASCO), and Philip became its research director. But in early 1938, dissatisfied with the direction of the business, he resigned. Within months, he was forming a new company built around a tungsten-titanium carbide composition he had patented while at VASCO.

At first, the economics looked modest. McKenna Metal’s first full year of sales—backed by a staff of 12—came to about $30,000. But history was about to hand the company the most intense manufacturing ramp the modern world had ever seen.

World War II put American heavy industry into overdrive, and Kennametal’s tools became part of the machining backbone of the wartime economy. Annual sales climbed toward $10 million, and employment rose to nearly 900.

And Kennametal’s war work went beyond “making more parts, faster.” During the war, more than half of the artillery shells produced in the United States were machined with Kennametal product. The company also developed a new type of anti-tank projectile made of tungsten with a hard carbide core. The same properties that made tungsten carbide ideal for cutting—extreme hardness, resistance to heat, resistance to wear—also made it effective for armor-piercing penetrators. Kennametal wasn’t just enabling production; in some cases, its materials were literally in the weapon.

Then the war ended—and the floor dropped out. When government orders declined in 1945, Kennametal’s revenues fell sharply. Philip McKenna’s response was decisive: diversify. He began developing tools for the mining industry and built a new plant in Bedford, Pennsylvania, to produce them.

That pivot mattered for reasons bigger than a single product line. It created a second engine for the company—wear-resistant components for harsh, abrasive environments—and planted the seed of the two-lane business Kennametal would become: metal cutting on one side, earthworks and mining applications on the other. Different end markets, same core advantage: materials that survive where ordinary steel fails.

In 1946, Kennametal introduced the Kendex line of mechanically held, indexable insert systems. To outsiders, it might sound like a small mechanical tweak. To a factory manager, it was a revelation. Instead of resharpening an entire tool when an edge dulled, machinists could rotate or replace an insert. Tool changes got faster. Precision improved. Downtime fell. It pushed metal cutting further toward the modern, modular system we take for granted today.

By the time Kennametal went public in 1960, the company had already built the foundations that would carry it for decades: proprietary materials science, real application engineering expertise, a growing global customer base, and—thanks to that post-war pivot—diversified industrial exposure. Philip McKenna died in 1969, and family members continued to manage the company. But his real legacy wasn’t just the alloy. It was the business philosophy embedded in it.

Because what McKenna understood—almost before the market had the language for it—was that Kennametal wasn’t really selling metal. It was selling productivity. A cutting insert that costs more but lasts longer, runs faster, and reduces downtime doesn’t just pay for itself; it changes the economics of the customer’s entire process. That insight powered Kennametal’s rise. And in the decades ahead, it would also shape the company’s biggest strategic bets—and its hardest lessons.

III. Building the Industrial Powerhouse (1970s–2000)

By the 1970s, Kennametal was no longer just the clever Pennsylvania company with a breakthrough alloy. It was becoming something much bigger: a global industrial supplier with a reputation for doing the hard, unglamorous work of keeping factories running.

The climb through the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s wasn’t perfectly smooth—industrial cycles never are—but the direction was clear. Kennametal grew into a multinational business serving customers across the world, and by this era it had become the dominant metal-cutting toolmaker in North America and one of the biggest players globally. At the same time, it built a leadership position in mining and highway construction tooling—the kind of products that live in abrasive, punishing environments where “good enough” fails quickly.

What made Kennametal different wasn’t just scale. It was what it actually sold.

Yes, the products were tangible: cutting tools and tooling systems made from tungsten carbide powders, high-speed steels, ceramics, industrial diamonds, and other materials built to resist heat, abrasion, pressure, and wear. And yes, the portfolio expanded under a growing collection of brands, including Kennametal, Hertel, Rubig, Widia, Cleveland Twist Drill, Greenfield, Hanita, Circle Machine, and Disston.

But the real product—the thing customers came back for—was productivity.

Kennametal didn’t win by being the cheapest box on the shelf. It won by embedding itself in the customer’s process. Its engineers and technical representatives weren’t just order-takers. They showed up to the factory floor, studied the customer’s specific operation, then matched tool geometry, materials, and cutting parameters to the job. If they could take minutes out of a cycle time, extend tool life, or reduce scrap, the value dwarfed the price of the insert itself.

That approach created real switching costs. A competitor wasn’t just offering “a similar tool.” Switching meant risking downtime, retraining operators, and walking away from a pile of hard-earned process knowledge Kennametal had helped build.

The results showed up in performance. By the end of fiscal 1979, sales had more than tripled, net income and earnings per share had quadrupled, and dividends had more than doubled.

Then came globalization. As manufacturing moved and spread, Kennametal followed—especially into Europe and Asia—because the model only worked if the technical support was local. By the early 2000s, the company employed roughly 12,000 people worldwide. In fiscal 2001, annual sales were about $1.8 billion, with roughly a third coming from outside the United States.

A lot of this era was shaped by Robert McGeehan, the first non-family leader of Kennametal. He joined in 1973 as a metalworking service engineer—about as close to the customer as it gets—then rose to president in 1989 and CEO two years later.

One of his most consequential moves was the acquisition of J&L Industrial Supply early in his tenure. It was a bold attempt to move closer to the customer by capturing more of the distribution layer: a mail-order, one-stop shop for cutting tools, abrasives, machinery and accessories, precision measuring instruments, and industrial supplies. Strategically, it made sense. Control more of the channel, learn more about buying behavior, and widen your share of wallet. In practice, it also added complexity—an early hint of a tradeoff Kennametal would wrestle with more and more in the years ahead.

By the late 1990s, Kennametal looked like what it had become: a respected industrial blue-chip. Profitable. Diversified. International. Deeply embedded in customer operations. But it also carried the quiet risk that comes with maturity. Growth was slowing. The culture—technically exceptional—was starting to feel insular. And the board could see that “keep doing what we’ve been doing” wasn’t a strategy.

McGeehan’s final major contribution was the acquisition of Greenfield. He announced his retirement in mid-1998 and stepped aside in July 1999. His successor was Markos Tambakeras, recruited from his role as president of Honeywell Industrial Control. Born in Egypt, raised in Greece, and educated in South Africa, Tambakeras arrived with a strong reputation and a mandate that was hard to miss: shake the company out of its comfortable groove.

The stage was set for an era of aggressive expansion that would remake Kennametal—for better and for worse.

IV. The Aggressive Expansion Era: Tambakeras and Cardoso (1999–2012)

When Markos Tambakeras took the CEO job in July 1999, he arrived with the posture of an outsider walking into a comfortable incumbent—and seeing potential the market wasn’t rewarding. An analyst told the Pittsburgh Business Times that fall, “Markos is innovative, hard driving, a big motivator… He definitely does not shy from a challenge.” That was the point. Kennametal didn’t hire him to preserve the status quo; it hired him to change it.

Tambakeras ran Kennametal as President and CEO from 1999 until retiring in 2005, then served as Chairman of the board from 2002 to 2006. Before Latrobe, he’d spent years at Honeywell, including roles as President of Industrial Controls and President of Asia Pacific—exactly the kind of résumé that signals “operator with global ambition.”

He also inherited real problems. Investor confidence was shaky, and not just in Kennametal. The company still owned more than 80 percent of JLK Direct after spinning it off, and both stocks had been underwhelming heading into his tenure. Meanwhile, Kennametal was carrying the weight of the Greenfield deal, and that debt load was hard to ignore.

Tambakeras’s response was a strategy that would define the era: use M&A to buy scale, extend reach, and reposition Kennametal as something bigger than a North American tooling champion. The early 2000s gave him both headwinds and openings. A recession squeezed demand in Kennametal’s core markets, but it also made acquisition targets more available—and more affordable.

The downturn hit quickly. In November 2001, Kennametal announced it would close three manufacturing plants to cut costs as sales declined. But while he managed the near-term pain, Tambakeras was setting up the big move.

That move came in May 2002, when Kennametal announced a definitive agreement to buy the Widia Group in Europe and India from Milacron for €188 million (about $170 million at the time). Widia was doing roughly $240 million in sales and was a leading manufacturer and marketer of metalworking tools, engineered products, and related services—particularly strong in Europe and India.

This was the kind of deal that could change the map overnight. Tambakeras called Widia “an excellent strategic fit,” pointing to strong brands, respected technology, and a loyal customer base. Widia brought meaningful footprint too: about 3,400 employees and ten manufacturing facilities across Europe and India, with a go-to-market model built largely around direct sales and local service teams.

And Kennametal was explicit about why it wanted it. The Widia acquisition would deepen the company’s position in its core metalworking business and, in Kennametal’s words, was “a major step” toward leadership positions in Europe and Asia. It wasn’t diversification for its own sake. It was globalization, done the fastest way possible: buy a platform.

With that foundation in place, Tambakeras began setting up a leadership handoff that preserved momentum. Carlos Cardoso joined Kennametal in 2003, became Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer in early 2005, and then took over as President and CEO in January 2006. His background was broad—manufacturing, engineering, quality, operations, sales, marketing—and the internal message was clear: continuity of strategy, with more operational horsepower behind it.

Under Cardoso, the acquisition pace continued. In 2005, Kennametal acquired Extrude Hone for $137 million, adding specialized machining capabilities. The broader playbook was consistent: expand the portfolio, broaden the reach, and keep pushing Kennametal toward a “solutions” posture—more capability, more offerings, more ways to attach to customer processes.

Cardoso’s tenure was also widely celebrated at the time. He was named one of America’s “Best Chief Executive Officers” by Institutional Investor in 2007 and received an Ernst & Young Regional Entrepreneur Of The Year award in 2009.

But while the strategy looked clean on PowerPoint, the operating reality kept getting messier. The 2008–2009 financial crisis slammed industrial customers, just as Kennametal was juggling the hard work of integrating businesses with different cultures, systems, factories, and product lines. Each deal added capability—but also added parts, plants, and complexity. And in a business where margins are made in execution, complexity is a tax you pay every day.

By the time Cardoso was nearing the end of his run—he announced his retirement in 2014—Kennametal had undeniably grown through acquisitions. It had also accumulated the less visible baggage: integration challenges, a heavier cost structure, and the kind of organizational sprawl that compresses margins at exactly the wrong moment, when customers start demanding concessions.

The “total solutions provider” ambition wasn’t irrational. But the combination of cyclicality, leverage, and complexity meant the company was heading into the next chapter with far less room for error. The stage was set for crisis.

V. The Lost Years and Leadership Chaos (2012–2016)

From 2012 to 2016, Kennametal hit its low point. The strategy blurred, performance slipped, and the leadership bench became a revolving door. It wasn’t just a bad patch in the cycle. It was a moment when the company had to confront an uncomfortable question: what, exactly, was Kennametal trying to be?

In November 2014, the board made a public break with the Cardoso era. It announced that Donald (Don) A. Nolan would become president and CEO and join the board, while lead director William R. Newlin would become chairman, effective Nov. 17, 2014. Cardoso’s retirement was set for Dec. 31, 2014. The messaging emphasized a “clear-cut, transparent transition”—the kind of language you use when you want everyone to know: this is a reset.

Nolan looked like a sensible pick. He had more than 30 years of experience in specialty materials, had led Avery Dennison’s Materials Group, and had held market-facing roles at Valspar. Earlier stops included Loctite, Ashland Chemical, and GE. And in a bit of symmetry, he’d started his career at Latrobe Steel—right in Kennametal’s backyard.

But the job he walked into was harsher than the résumé match suggested. Revenue was sliding from its earlier peak. Margins were tightening. The company was still digesting years of acquisitions that hadn’t fully knitted together. And manufacturing overcapacity—globally, and inside Kennametal’s own footprint—was weighing on performance.

The board didn’t wait long. After only about 15 months, it pulled the lever again.

In February 2016, Kennametal announced that board member Ronald M. DeFeo would step in as president and CEO, effective immediately. DeFeo had most recently been chairman and CEO of Terex Corporation, retiring at the end of 2015. Nolan was out, described as leaving “to pursue other interests.”

The board’s statement was unusually blunt. Chairman Lawrence W. Stranghoener said, “We have determined a change in leadership is necessary,” and framed DeFeo’s mandate in plain terms: “He will sharpen our focus, prioritize our results, and motivate, engage, and empower our people to produce the financial results that are expected of an industry leader like Kennametal.”

Then came the line that said the quiet part out loud. The board thanked Nolan and called him “a necessary change agent through a period of significant turmoil and uncertainty.” In other words: the situation was worse than expected, and the company needed a different kind of operator.

DeFeo wasn’t coming in cold. He’d been on Kennametal’s board since 2001, and he leaned on that familiarity immediately: “As a 14-year member of the Kennametal board, I know what the company and its people are capable of achieving.”

His diagnosis was straightforward and unsentimental. Kennametal had become bloated and sprawling—too many SKUs, too many plants, and a strategy that tried to cover too much ground. And in a business where execution is everything, that kind of complexity doesn’t just slow you down. It bleeds you, every day.

So DeFeo went for emergency surgery.

When Kennametal reported full-year results on Aug. 2, 2016, it paired them with a major restructuring plan: cut about 1,000 jobs over the following 15 months, targeting $100–$110 million in savings by the end of fiscal 2017. The company also pointed to momentum in its most recently completed quarter, with sales up year over year, organic growth, and quarterly profit of $38.9 million—evidence that the core franchise still had life if it could be unburdened.

Over the next 18 months, the playbook was all about simplification. Plant closures accelerated. Thousands of low-volume products were eliminated. The organization was re-centered around two core segments: Metal Cutting and Infrastructure. And the “total solutions provider” ambition faded into the background, replaced by something closer to Kennametal’s roots: it makes cutting tools and wear-resistant components, and it intends to be world-class at that.

By the time the company was preparing for the next handoff, the board’s tone had shifted. Stranghoener said, “We want to thank Ron DeFeo for the dramatic progress he has made to reposition Kennametal over the past 18 months,” and set expectations for the next phase: “We expect Chris will bring continuity to the transformation presently underway at the company while evolving a strategy and vision for the future that will continue to deliver results for our customers, team members and shareholders.”

That “dramatic progress” line is the tell. DeFeo didn’t finish the turnaround—no one could in 18 months—but he stopped the bleeding and built a foundation solid enough for a real transformation. In August 2017, with the emergency work largely done, he moved to Executive Chairman, and a new CEO stepped in to take Kennametal from triage to reinvention.

VI. The Rossi Transformation Era (2017–2024)

Christopher Rossi stepped into the CEO role in August 2017 with a very specific job: keep the turnaround moving, but turn DeFeo’s emergency measures into an actual strategy—one that could survive the next cycle and rebuild confidence in Kennametal’s long-term future.

Rossi came from Dresser-Rand, the industrial equipment maker owned by Siemens. He had served as its CEO from September 2015 through May 2017, and before that he’d spent decades inside the business in roles spanning global operations, technology and business development, and aftermarket sales. In other words, he wasn’t a “restructuring celebrity.” He was a career operator—someone who’d lived inside complex industrial organizations and knew how to change them without breaking them.

Kennametal’s chairman, Lawrence W. Stranghoener, framed it as continuity plus evolution: “We expect Chris will bring continuity to the transformation presently underway at the company while evolving a strategy and vision for the future that will continue to deliver results for our customers, team members and shareholders.”

The framework that emerged under Rossi had a plain-English name: “Simplification/Modernization.” It was a multi-year effort to do two things at once—strip out complexity and cost, while upgrading the manufacturing backbone so Kennametal could compete on speed, quality, and service, not just history.

That meant more footprint rationalization. Kennametal announced restructuring actions designed to “facilitate a simplified and leaner structure” by optimizing operations globally, including proposals to close manufacturing facilities in Essen and Lichtenau, plus a distribution center in Neunkirchen—all in Germany. The intent wasn’t just savings on paper. It was a re-layout of how the company made and moved product.

The expected payoff was meaningful: tens of millions of dollars in annualized savings, paired with substantial pre-tax charges to fund the change. Rossi’s message was the balancing act every industrial turnaround has to pull off: cut deep, but keep serving customers. “We have made good progress on our restructuring actions and reducing structural costs while also improving efficiency, consolidating plants and driving increased shareholder value,” he said. “Throughout the process we have maintained a focus on serving our customers and supporting our employees while we work through these transitions.”

By this point, the closures were real, not theoretical. Kennametal completed the shutdown of its Lichtenau, Germany facility and its Irwin, Pennsylvania plant, and consolidated that work into other lower-cost and newly modernized facilities.

Then the world changed.

COVID-19 hit in 2020, and for a company tied to global production floors, it was the ultimate stress test. Kennametal accelerated parts of the Simplification/Modernization program to protect the business, including a restructuring that targeted about 10 percent of its salaried workforce globally, expected to be substantially complete in the first half of fiscal 2021.

What stood out wasn’t that Kennametal restructured during COVID. Many industrial companies did. It was that the company didn’t lose the thread. The transformation stayed intact through the disruption, rather than becoming another half-finished program abandoned at the first sign of trouble.

By September 2023, Rossi was ready to lay out the next leg. At the company’s Investor Day, Kennametal provided updates on its growth, margin expansion, and innovation plans through fiscal 2027. The strategy wasn’t just “cut costs.” It leaned into how Kennametal actually wins: targeted share gains, better commercial execution, and faster product innovation.

One of the most important shifts was commercial. Kennametal said it had “enhanced our Commercial Excellence process to drive share gain and add new revenue streams in underserved areas” of its end markets—and pointed to Aerospace & Defense as proof that the approach could work. The point was confidence: if the process could drive share gains there, it could be applied to other targeted markets too.

Operationally, the company also announced a $100 million Operational Excellence and Capacity Optimization initiative. It included $20 million carried over from the previously announced restructuring program, ongoing operational improvement roughly equivalent to about 1% of cost of sales per year, inventory optimization, and plans for three to five additional plant closures.

In 2024, the story delivered something Kennametal hadn’t had in years: a calm leadership transition.

In March 2024, the company announced that Sanjay Chowbey would become CEO effective June 1, 2024. Rossi would retire after nearly seven years in the role. Chairman William M. Lambert summed up Rossi’s tenure in the language that matters most in this business: “Chris is leaving the company better than he found it, having successfully executed the company's Simplification/Modernization strategy, which improved the efficiency and customer service level of its factories while enabling the manufacturing of new product innovations.”

Chowbey wasn’t a break-glass appointment. He joined Kennametal in 2021 as President of the Metal Cutting segment, and under his leadership the business expanded its customer base, consistently delivered sales growth, expanded operating margins, launched more than 20 new products, and improved employee engagement. Before Kennametal, he was President of Flowserve’s $1.2 billion Services & Solutions business and held roles across Flowserve, Danaher, and Arvin Meritor, with responsibilities spanning strategy, operations, sales, marketing, and finance.

When Chowbey spoke about fiscal 2024, he struck the tone of someone inheriting momentum, not rubble: “Thanks to the hard work and diligence of our global team, we delivered a strong finish in fiscal year 2024 despite persistent market softness, foreign exchange headwinds and a natural disaster affecting our facility in Arkansas. We successfully met our revenue and EPS outlook and generated $277 million in cash from operations, the highest as a percent of sales in over 25 years.”

Then he made the handoff explicit—three “Value Creation Pillars” to guide what came next: Delivering Growth, Continuous Improvement, and Portfolio Optimization.

After a decade of whiplash, that was the real milestone of the Rossi era: Kennametal wasn’t just smaller and leaner. It finally had the stability—and the operating system—to try to grow again.

VII. The Business Model Deep Dive

To really understand how Kennametal creates value, you have to stop looking at it like “a company that sells tools,” and start looking at it like a company that sells performance under pressure. The products are small. The impact on a customer’s factory is huge. And that’s why loyalty can be so stubborn, even in a brutally competitive market.

Kennametal runs two main businesses. Metal Cutting generates roughly two-thirds of revenue. Infrastructure makes up the other third. They share the same materials-science DNA, but they win in different arenas.

Metal Cutting is the precision side of the house. This is where you’ll find the milling cutters, turning inserts, drilling tools, and specialized systems that machine parts for aerospace, automotive, general engineering, and energy customers. The buyers are a mix of OEMs and the contract manufacturers who actually do the machining. The work is all about consistency: cycle time, surface finish, tolerances, and tool life. When the job is hard—titanium, superalloys, high-volume production—tool performance isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the difference between hitting schedule and missing it.

Infrastructure is the harsh-environment side. Think mining tools, road construction wear parts, and wear-resistant components used in oil and gas drilling. These products are designed to be sacrificed in service of the job: they grind, scrape, and absorb abuse until they’re replaced. The purchasing channels and the competitive dynamics are different, but the core promise is the same: survive longer in punishing conditions.

Underneath both segments, the economic engine is surprisingly consistent.

First, Kennametal lives in a consumables world with real switching costs. Once a tool is qualified for a production process, it’s not easily swapped. Qualification often means extensive testing and tuning—feeds and speeds, tool geometry, coatings, coolant strategy, workholding, the whole system. Changing suppliers introduces risk: Will the new tool hold tolerance? Will finishes stay consistent? Will tool life drop and trigger unplanned changeovers? In shops where downtime is expensive and schedules are tight, those are business-threatening questions, not academic ones.

Second, application engineering is the wedge. Kennametal isn’t just shipping boxes of inserts. It’s selling know-how: how to apply the tool, how to tune the process, how to reduce scrap, how to run faster without breaking things. A field engineer might spend days inside a customer’s operation diagnosing bottlenecks and recommending changes. That work compounds over time, and it ties the customer to more than a part number. Switching suppliers can mean walking away from a body of accumulated process knowledge.

Third, the company is deeply exposed to raw materials—especially tungsten and cobalt, the building blocks of tungsten carbide. Those supply chains are concentrated and prices can be volatile, which makes commodity management a permanent feature of the job. Kennametal’s vertical integration into powder production, strengthened by the ATI acquisition, helps with supply security and cost position. But the exposure never disappears; it’s part of the terrain.

That’s the machine. And you can see it playing out in the company’s more recent results.

For fiscal 2025’s second quarter ended December 31, 2024, Kennametal reported sales of $482 million, down from $495 million a year earlier. EPS was $0.23 versus $0.29 in the prior-year quarter. This is what operating in cyclical end markets looks like: demand can soften, and the numbers follow.

The more important storyline is margins and the discipline behind them. In that quarter, Kennametal delivered about $7 million in restructuring savings from previously announced actions to streamline its cost structure, while continuing to invest in its Commercial and Operational Excellence initiatives. By the end of fiscal 2024, those actions were running at an annualized pre-tax savings rate of roughly $33 million.

Management also kept leaning into a familiar balancing act: return cash to shareholders while funding the factory. In fiscal 2025, Kennametal returned $122 million through dividends and share repurchases, and invested $89 million in capital expenditures. By June 30, 2025, it had reached about $65 million in annualized run-rate pre-tax savings, moving toward the Investor Day goal of $100 million by the end of fiscal 2027. The savings included structural cost improvements, the closure of the Greenfield, Massachusetts facility, and facility consolidation in Barcelona, Spain. The broader cost program was also expanded to target $125 million in savings by the end of fiscal 2027.

In other words: the model hasn’t changed—consumables, switching costs, application engineering, materials science. What’s changing is how efficiently Kennametal runs that model, and how consistently it can turn it into margin through the cycle.

VIII. Competitive Landscape & Industry Dynamics

Kennametal plays in one of those industries that looks chaotic up close—dozens of brands, endless catalogs, constant product launches—but has been remarkably stable at the top for decades. That stability isn’t because competition is weak. It’s because the barriers to playing at the highest level are real: metallurgy, coatings, precision manufacturing, and the field-engineering muscle to prove performance on a customer’s floor.

At the global, full-line tier, the usual names show up again and again: Sandvik Coromant, Kennametal, ISCAR, Mitsubishi Materials, Kyocera, Seco Tools, and others with the breadth to cover turning, milling, drilling, and more—plus the sales and service footprint to support multinational customers. Alongside them are specialists that win in narrower lanes: companies like Union Tool, Horn USA, and Vargus, which focus on niche applications such as PCB milling, grooving, or threading. Notably, many of the most respected players are headquartered in Japan, Germany, the U.S., and Sweden—places where precision engineering is practically a national pastime.

Zoom out, and the industry structure looks deceptively “competitive” in the textbook sense. Market concentration is low, and the market is fragmented, with global leaders competing alongside countless domestic and regional manufacturers that tailor products to local needs. That fragmentation creates constant pressure on vendors to sharpen their value proposition. In plain English: nobody gets to coast.

Where it gets interesting is how competition changes depending on where you sit in the market.

At the premium end—think aerospace, medical devices, and the toughest automotive applications—the game is less about price and more about outcomes. Customers buy speed, tool life, repeatability, and the ability to hit tolerance without drama. In that world, the winner isn’t the vendor with the cheapest insert; it’s the one that can show up with the right geometry, coating, and cutting parameters, and take real time and scrap out of the process. A tool that costs more but runs faster, lasts longer, and reduces downtime is often the cheaper choice when you look at total economics.

In the mid-market, the knife fight gets sharper. Chinese manufacturers have made meaningful inroads, especially in less demanding applications where low cost can outweigh a performance gap. At the same time, the overall landscape has been getting more capable: better materials, better coatings, and more data-driven process insight are raising the baseline across the board. Full-line providers—from the biggest global brands to a long list of established competitors—use breadth and support to stay relevant, while regional players compete aggressively on availability and price.

Layer on top the technology tailwinds reshaping machining. The cutting tools market has been pushed forward by CNC and multi-axis machining, and increasingly by IoT and tool monitoring. Leading companies are investing in “smart” tooling and sensor-enabled systems that help customers improve precision and reduce variability. Others are leaning into application-specific tools, particularly for aerospace and for newer manufacturing needs like electric-vehicle components where machining demands are evolving.

And then there’s consolidation. Scale matters in this business—because it funds R&D, supports global service, and helps absorb the fixed costs of manufacturing. Berkshire Hathaway’s IMC Group, for example, brings together ISCAR, Tungaloy, and other brands under a single umbrella, pairing industrial scale with Berkshire’s patient capital. Sandvik’s Machining Solutions division competes at a scale that, in many ways, rivals Kennametal’s entire company. These kinds of groups have reshaped the field: larger competitors, broader portfolios, deeper pockets, and the ability to keep investing through downturns.

So Kennametal’s competitive reality is a mix of all of it: a fragmented market with relentless day-to-day rivalry, a premium tier where performance and engineering support create defensible positions, and a consolidating set of global giants that can outspend and out-scale smaller players. In other words, it’s an industry where you can’t win by being “good.” You win by being indispensable.

IX. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

If you’re a new company trying to break into cutting tools, you’re not just competing with catalogs and pricing. You’re competing with decades of metallurgy, coatings know-how, and hard-earned application data. Customers don’t casually “try” a new toolmaker on a production line. Qualification can take months or years, and in aerospace and defense it comes with documentation, certifications, and a track record you can’t fake.

A local shop can build a niche, especially in a regional market. But building anything resembling Kennametal’s global footprint—materials science, manufacturing, sales coverage, field engineering—takes time, capital, and a lot of learning that only happens the hard way.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MEDIUM-HIGH

Kennametal lives and dies by a few critical raw materials, especially tungsten and cobalt. Those supply chains are concentrated, and they’re exposed to geopolitical and pricing volatility. China controls a significant share of global tungsten production, which adds a strategic risk layer on top of the usual commodity swings. Cobalt has similar concentration issues.

Kennametal’s vertical integration into powder production helps blunt some of the impact, but it doesn’t change the underlying truth: commodity exposure is structural in this business, and it shows up in margins when prices move.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM

On paper, the buyers look powerful. Major industrial customers—Boeing, Caterpillar, big automotive OEMs—are sophisticated, price-aware, and more than capable of pushing vendors for concessions.

But tooling is one of those categories where the sticker price isn’t the real price. Performance is mission-critical, and failures can be brutal: downtime, scrap, missed shipments, angry end customers. That’s where switching costs show up. Once a tool is proven, tuned, and embedded in a process—with application engineers helping optimize feeds, speeds, and toolpaths—changing suppliers isn’t just a purchasing decision. It’s an operational risk decision. And most manufacturers will pay to avoid risk.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MEDIUM

For a huge range of machining applications, tungsten carbide is still the workhorse. There isn’t a simple substitute that can step in across the board.

The real long-term “substitute” isn’t another tool material—it’s making parts in ways that require less machining. Additive manufacturing is the obvious example: parts that don’t need to be cut don’t need cutting tools. But for high-performance applications, adoption has been limited. Other materials like ceramics and coated alternatives can win in specific niches, but they don’t replace carbide as the default across the spectrum.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a hard industry with constant knife-fighting. The top players compete globally, and innovation never stops: new grades, new geometries, new coatings, new application-specific systems. In the more commoditized parts of the market, price pressure is real, and it’s intensified by capable lower-cost competitors.

At the same time, the market is broad enough for multiple winners—especially when they differentiate by end market, geography, and application depth. Rivalry stays high, but so does the opportunity for the companies that can be indispensable.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

Scale matters here in a very industrial way: it helps absorb fixed manufacturing costs, fund R&D, and support a global service network. Kennametal’s restructuring and footprint optimization were, in part, about getting more of those benefits.

But it’s not winner-take-all. Multiple companies can reach “enough” scale to compete effectively, which caps how dominant scale economies can be.

2. Network Effects: WEAK (but emerging)

There isn’t a classic network effect—customers don’t use Kennametal because other customers use Kennametal.

Where it could start to emerge is data. IoT-enabled tooling and process monitoring can create a flywheel: more usage generates more machining data, which can improve recommendations and optimization. That’s still early, but it’s the closest thing this industry has to a network effect.

3. Counter-Positioning: MODERATE (historically)

Philip McKenna’s tungsten carbide breakthrough was counter-positioning in its purest form: it attacked the limitations of high-speed steel with a fundamentally better material.

Today, counter-positioning comes from the other direction. Low-cost manufacturers—particularly in China—can undercut incumbents in less demanding applications. Kennametal’s answer has been to push upmarket where performance, engineering support, and risk reduction matter more than unit price.

4. Switching Costs: STRONG ⭐

This is the heart of Kennametal’s moat. Tooling gets qualified, then optimized into a process. Operators get trained. Parameters get dialed in. Tool performance becomes part of the customer’s production reliability. Switching suppliers means re-testing, re-tuning, and risking disruption.

In manufacturing, risk has a price. And that price is what makes switching costs so powerful here.

5. Branding: MODERATE-STRONG

In industrial markets, brand is less about awareness and more about trust. Kennametal and Widia are known quantities in shops where a tool failure doesn’t just hurt yield—it can shut down a line.

It’s meaningful strength, just not consumer-style brand power.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Kennametal has proprietary materials formulations, coatings expertise, accumulated application knowledge, a patent portfolio, and strategically placed manufacturing capabilities. Those are real advantages.

But none of them are magic. Competitors can replicate parts of the stack over time. The resource is valuable, but not unassailable.

7. Process Power: STRONG ⭐

The ability to repeatedly make hard materials consistently, apply them in the field, and improve customer outcomes is process power—and Kennametal has been building it for decades. Its application engineering playbook, its manufacturing expertise, and its customer integration processes are exactly the kind of operational advantage that compounds.

The Simplification/Modernization program wasn’t just about cost. It was about restoring and strengthening this process power so Kennametal could execute better than its complexity-burdened past.

X. Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bear Case 🐻

Cyclicality is still the tax. Industrial manufacturing moves with the business cycle, and Kennametal doesn’t get a waiver. When customers pull back on production and capital spending—as they do in every downturn—tooling demand falls with it. The transformation may improve through-cycle performance, but it can’t make the business non-cyclical.

End-market concentration cuts both ways. Kennametal’s exposure to aerospace, automotive, and energy gives it access to big, attractive markets—but it also ties results to the ups and downs of those markets. Aerospace demand after COVID has been uneven. Automotive is navigating the EV transition. Energy is, as always, volatile.

Chinese competition keeps rising. In the mid-market, lower-cost manufacturers continue to close the quality gap while holding a structural cost advantage. That’s where a lot of industry volume lives—and where price pressure can show up fastest.

Execution risk doesn’t go away just because the plan is right. Chowbey put it plainly on a recent quarter: “This quarter we once again generated strong cash flow from operations. However, conditions in a number of our end markets, primarily in EMEA, continued to weaken resulting in sales at the lower end of our expectations.” He added, “In light of these challenging conditions, we have reduced our full year outlook and have taken the additional restructuring actions we announced in mid-January.” That’s the double bind: keep investing in improvement while the cycle is turning against you.

Margin expansion isn’t guaranteed. When organic sales decline, pricing gains can get swallowed by lower volume. Kennametal’s ambition of reaching mid-teens EBITDA margins is possible—but not assured if softness lingers or competition forces more concessions.

The Bull Case 🐂

The transformation is showing up in the numbers. In a recent quarter, the increase in operating income was helped by the timing of pricing versus raw material costs, a small benefit from insurance recoveries related to the tornado at the Rogers, Arkansas facility late in fiscal 2024, an advanced manufacturing production credit under the Inflation Reduction Act, and incremental year-over-year restructuring savings. Those positives were partially offset by lower production volumes and higher wages and general inflation. The result: adjusted operating income of $16 million, an 8.6 percent margin, up sharply from $4 million, a 1.9 percent margin, in the prior-year quarter.

The headline takeaway matters more than the mix of tailwinds: when the operating system improves, the business can produce very different profitability—even without a roaring demand environment.

Infrastructure’s margin improvement, in particular, is a proof point. It suggests the restructuring strategy works when it’s executed and the footprint is right-sized.

Secular tailwinds are real. Even if the path isn’t smooth, aerospace production ramps, infrastructure spending, onshoring, and the energy transition all require machining and wear-resistant components. This is a “picks and shovels” business for the physical economy.

Cash generation has become a strength again. In fiscal 2024, Kennametal generated $277 million in cash from operations—the highest as a percent of sales in more than 25 years. In a cyclical industrial company, that kind of cash performance is often the clearest signal that simplification is working.

Shareholder returns are back on the menu. During a recent quarter, the company repurchased 857 thousand shares for $22 million, completing its initial $200 million share repurchase program. The board also authorized an additional $200 million, three-year repurchase program (announced in February 2024) in place for fiscal 2025. And it paid $16 million in cash dividends during the quarter. The message: management believes the business can both fund the factory and return capital.

Leadership continuity is an advantage. The Rossi-to-Chowbey handoff wasn’t a crisis pivot. It was planned succession. Chowbey inherits a transformation already in motion—and he’s already demonstrated he can execute inside it.

Base Case & What to Watch

Kennametal looks like a company in the middle innings of a real transformation. It has made meaningful progress simplifying operations and lifting margins, but it’s not finished—and the cycle is throwing near-term challenges back into the story.

Key KPIs to monitor:

-

Adjusted operating margin (by segment): The clearest scoreboard for whether the operating model is getting better. Watch whether Metal Cutting can move toward mid-teens margins and whether Infrastructure can sustain high-single-digit performance.

-

Free operating cash flow as a percentage of revenue: This is the quality-of-earnings metric that matters in an industrial business. Recent performance—cash from operations at the highest percent of sales in 25+ years—supports the idea that simplification is translating into durable efficiency.

XI. Key Lessons & Takeaways

Strategic Lessons

1. Complexity is expensive. Kennametal’s 2000s acquisition spree didn’t just add revenue; it added layers of operational drag. Too many brands, overlapping product lines, redundant facilities, and fragmented systems turned into a daily tax on execution—one that quietly ate margins and management attention.

2. Focus matters. The comeback started when the company stopped trying to be everything to everyone and recommitted to what it actually does better than most of the world: cutting tools and wear-resistant components. The “solutions provider” ambition wasn’t crazy, but it diluted the core and made it harder to win where Kennametal had real edge.

3. Transformation takes time. The hard truth of industrial turnarounds is that you don’t fix them in a few quarters. From DeFeo stepping in during 2016’s crisis to the present, Kennametal has been reshaping its footprint, cost structure, and operating discipline for years. It’s a marathon, not a sprint.

4. Process power compounds. Kennametal’s advantage isn’t just in materials or catalogs. It’s in decades of application engineering and the repeatable ability to translate that know-how into better outcomes on customer floors. That kind of capability doesn’t show up overnight—and competitors can’t copy it quickly.

Operating Lessons

1. Manufacturing footprint is strategic. In this business, the factory network is destiny. Where you make product—and how efficiently you can make it—drives cost, quality, lead times, and ultimately whether customers trust you when their production line is on the line.

2. SKU rationalization is powerful. Cutting low-volume products isn’t glamorous, but it’s one of the fastest ways to restore focus. Fewer SKUs means fewer changeovers, less inventory, simpler planning, and a business that can actually execute at a high level again.

3. Modernization enables innovation. Updating manufacturing capability isn’t just about efficiency. It’s what makes faster product development, tighter quality, and more consistent performance possible—exactly the things that keep a tooling company relevant when the materials get harder and the tolerances get tighter.

XII. The Future & Current State (2024–2027)

The Chowbey Era

Chowbey stepped into the CEO role with a message that fit Kennametal’s identity: this isn’t just a company with factories, it’s part of an industry that has to be defended and rebuilt.

“The NAM plays a vital role in shaping the future of manufacturing and I am honored to join their Board of Directors,” he said. “Representing our employees and customers as the industry evolves is important, and I look forward to collaborating with fellow board members to advance key priorities for U.S. manufacturing, including policy, workforce development and more.”

That move matters because it signals how Chowbey intends to show up: not only as an internal operator finishing a multi-year restructuring, but as a public-facing manufacturing leader. The handoff from Rossi to Chowbey wasn’t a scramble. It was deliberate succession planning—and joining the National Association of Manufacturers board reads like an early marker of stability and confidence.

Strategic Priorities

In the near term, the job is straightforward, but not easy: finish the restructuring while managing through cyclical softness.

As of June 30, 2025, Kennametal had reached about $65 million in annualized run-rate pre-tax savings—real progress toward the Investor Day goal of $100 million by the end of fiscal 2027. Those savings included structural cost improvements, the closure of the Greenfield, Massachusetts facility, and the consolidation of operations in Barcelona, Spain. And the company raised the bar: the initiative was expanded to target $125 million in total cost savings by the end of fiscal 2027.

You can read that increase two ways, and both can be true. It suggests confidence that the playbook works. It also admits there’s still more cost and complexity left in the system than anyone wants in a cyclical industrial business.

The Big Questions

Can Kennametal achieve sustained double-digit EBITDA margins? The operating system has improved, and the company has proven it can lift profitability. The harder test is doing it consistently—through the cycle, not just in the good quarters—on the way to the mid-teens ambition.

Will aerospace growth offset other cyclical pressures? Aerospace is exactly the kind of market where premium tooling wins, but the recovery has been uneven. Long-term production ramps at Boeing and Airbus should help, yet they have to be strong enough to counter weakness elsewhere.

How to compete with China while maintaining premium positioning? The mid-market keeps feeling pressure from low-cost competitors. Kennametal’s answer—push upmarket into higher-value applications—protects margin and plays to its strengths, but it also narrows the playing field.

What’s the M&A strategy? After years spent integrating and untangling the last era of dealmaking, Kennametal has been cautious. Tuck-in acquisitions in adjacent technologies remain possible, but big, identity-changing M&A looks unlikely—especially for a company that has already lived through the cost of complexity.

XIII. Epilogue: The Quiet Importance of Making Things

Kennametal began with a single, stubbornly practical breakthrough: a material that could cut metal faster, longer, and more reliably than what came before. And across the decades, that same impulse—use materials science to win time, precision, and uptime for customers—kept the company relevant, even as the world around it changed.

That’s what makes Kennametal’s long arc worth studying. Its journey from Philip McKenna’s early work in Latrobe to a global industrial technology company isn’t just a story about tungsten carbide. It’s a story about what it takes to stay mission-critical in an industry that never stops testing you: technology shifts, globalization, brutal cycles, and the slow creep of organizational complexity.

In a world obsessed with software, platforms, and network effects, Kennametal is a reminder of something easy to forget: the physical world still needs to be cut, shaped, and built. The sleekest devices and the most advanced aircraft still begin as raw material that has to be machined into form. Every plane that carries passengers across oceans depends on components manufactured to tolerances measured in microns—tolerances achieved through precision cutting, day after day, in factories most of us never see.

And if there’s one through-line in Kennametal’s story, it’s the hardest problem in business: maintaining excellence over generations. Kennametal had stretches where it looked like an industrial machine—disciplined, embedded with customers, and hard to dislodge. Then came the complexity-driven decline: acquisitions, sprawl, and a cost structure that became a drag just as the cycle turned. And then the painful, necessary work of simplification—closing plants, cutting SKUs, rebuilding the operating system—so the company could compete on execution again.

The lessons depend on who you are.

For investors, Kennametal is a case study in why cyclical industrials can be compelling at the lows—if the transformation is real, the leadership is credible, and you have the patience to let both the operating improvements and the cycle do their work.

For operators, it’s a reminder that complexity is the enemy of excellence. Deals that make perfect strategic sense on paper can still destroy value if integration overwhelms the organization, distracts management, and erodes the day-to-day discipline that actually creates margin.

And for anyone watching American manufacturing, Kennametal is proof that the story isn’t over. The tools that helped machine the Arsenal of Democracy in World War II evolved into the tools that shape modern aerospace, infrastructure, and energy. The products changed. The tolerances got tighter. The materials got nastier. But the need never went away.

Kennametal itself puts it plainly: in addition to its portfolio of tungsten powders, the company brings more than 80 years of tungsten and tungsten carbide manufacturing and processing innovation, dating back to when Philip M. McKenna created the first tungsten-titanium carbide alloy for cutting tools and wear components. Its manufacturing and applications engineers, it says, take pride in carrying on that entrepreneurial spirit and delivering high-performance material solutions to customers.

That’s Philip McKenna’s legacy in its truest form—not nostalgia, but continuity. Engineers solving hard problems. Metallurgists pushing materials to do what ordinary steel can’t. Field teams helping customers squeeze more output from the same machines. Quiet work, compounding over time.

The company he founded is still doing what it has always done: making the modern world possible—one cut at a time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music