Kyndryl Holdings: The World's Largest Infrastructure Services Spin-Out

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

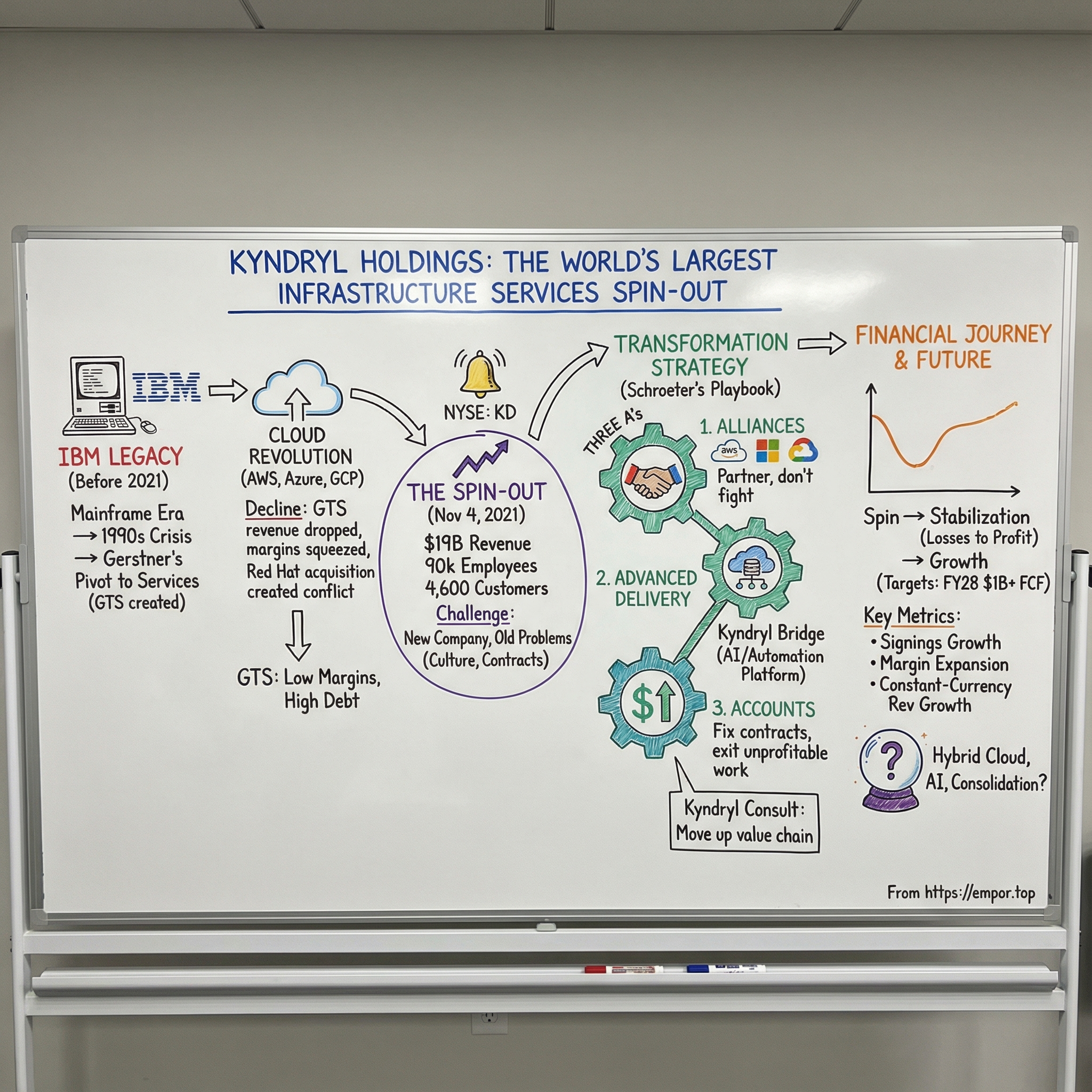

Picture this: November 4, 2021. Lower Manhattan, on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. A brand-new company rings the opening bell—but this isn’t a scrappy startup cashing in on a garage dream.

This is a revenue giant, spun into existence with about $19 billion in annual sales, 90,000 employees on day one, and responsibility for the kind of infrastructure nobody thinks about until it breaks. The systems behind banks moving money. Airlines running reservations. Governments delivering basic services. And it was already managing mission-critical infrastructure for roughly three-quarters of the Fortune 100.

The name? Kyndryl. It sounds like it came out of a corporate naming generator—because, in a way, it did. IBM unveiled the name in April 2021: “Kyn” for kinship, “Dryl” for tendril.

And with that, the largest corporate spin-off you’ve never heard of stepped onto the public stage, trading on the NYSE under the ticker “KD.” CEO Martin Schroeter put a confident frame around the moment: “We are thrilled that Kyndryl is today an independent company -- with 90,000 of the best and brightest professionals, a strong balance sheet and a path to growth.”

But the celebration masked an immediate, existential question: can a decades-old infrastructure services business—built inside IBM and optimized for a different era—become a modern, agile company fast enough to survive the cloud revolution?

That’s the story we’re about to tell: a legacy tech transformation, the corporate carve-out playbook executed at staggering scale, and a fight to compete in a market that keeps getting more commoditized—all while rebuilding the plane mid-flight.

It’s also a story bigger than Kyndryl. Across industries, thousands of companies are staring at the same dilemma: are you trapped in yesterday’s business model, and if so, can you actually reinvent yourself—or do you just narrate change on the way down?

This is how a century of IBM infrastructure services became the world’s largest IT infrastructure services company—and the open question of whether Kyndryl can write its own future, instead of living as a prisoner of its past.

II. The IBM Legacy: Where Kyndryl Came From

To understand Kyndryl, you have to start with IBM—and with the reinvention inside IBM that made Kyndryl both inevitable and, eventually, unavoidable.

IBM is basically a century-long biography of business computing. It began with tabulating machines used to count the 1890 U.S. census and grew into the company that defined mainframes and enterprise IT for most of the twentieth century. For decades, if a government agency or a global corporation wanted computing to work, they bought IBM.

Then, in the early 1990s, the unthinkable happened: IBM started to break. In 1993, it reported an $8 billion loss, the largest in American corporate history at the time. The PC revolution—ironically, one IBM helped kick off—was gutting the economics of the mainframe era. IBM had been built around a world where the mainframe sat at the center of everything, and its profits reflected that: more than 90% of IBM’s profit came from mainframes, and that engine was sputtering.

IBM needed a reset. It got one in the form of Lou Gerstner: an outsider, pulled from RJR Nabisco, and not a traditional “tech CEO.” Louis V. Gerstner Jr. became chairman and CEO in 1993 and led IBM through 2002, and he’s widely credited with bringing the company back from the brink.

Gerstner made two moves that echo through this story.

First, he refused to do what nearly everyone insisted was the only option: break IBM into smaller companies. Analysts, industry experts, and plenty of IBM insiders believed IBM was simply too big and too slow to survive intact. Gerstner held the line. IBM would stay together.

Second—and this is where Kyndryl’s DNA begins—he pushed IBM to stop thinking of itself primarily as a product company and start acting like a services company. The bet was straightforward: if customers were overwhelmed by complexity, IBM could sell not just the machines and the software, but the ongoing operation of the entire environment. In other words: “Let us run your IT.”

That shift created IBM Global Services. As hardware revenue weakened through the 1990s, services grew into a massive new profit engine. By the end of the decade, IBM Global Services made up about 40% of IBM’s revenue.

The logic was elegant. Hardware was getting squeezed, but “solutions” were sticky. Enterprises wanted a trusted partner to manage increasingly complicated systems, and IBM was already in the building. Multi-year outsourcing contracts—often huge ones—became the new bread and butter.

In 2002, IBM doubled down by acquiring PwC Consulting and folding it into the services operation. Over the following years, services and consulting expanded into the center of gravity for IBM’s business, eventually accounting for roughly two-thirds of revenue.

But “services” at IBM actually meant two very different businesses.

IBM Global Business Services, or GBS, was the consulting side: advisory work, application development, higher-margin projects. IBM Global Technology Services, or GTS, was the infrastructure side: data centers, networks, mainframes, and the operational plumbing that has to work every second of every day.

GTS—especially its Managed Infrastructure Services unit—was the business that would later be carved out as Kyndryl. On day one, that spin came with about 4,600 customers (including 75 of the Fortune 100), more than a quarter of IBM’s roughly 350,000 employees, around $19 billion in annual revenue, and an order backlog of about $62 billion.

That IBM legacy explains Kyndryl’s core paradox. It inherited enormous strengths: deep technical expertise, decades-long relationships with the world’s most demanding enterprises, and a backlog that gave it revenue visibility far into the future. It also inherited the baggage: a cost structure, culture, and operating model optimized for the old world—one where outsourcing meant managing fleets of customer-owned infrastructure, not orchestrating workloads across clouds.

And that tension—between what IBM built GTS to be, and what the market started demanding next—is what forced the split in the first place.

III. The Decline: Why IBM Had to Split

The seeds of Kyndryl’s separation were planted long before the formal announcement. Gerstner’s services strategy saved IBM in the 1990s, but by the 2010s the foundation was cracking—because the ground under enterprise computing was moving.

Virginia “Ginni” Rometty became IBM CEO in 2012 and walked into a different kind of existential threat than Gerstner ever faced: the public cloud. Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud weren’t just new competitors. They were changing the default answer to a basic question.

For decades, the answer had been: “Enterprises run their own infrastructure, and they outsource the mess to IBM.”

Now the answer was increasingly: “Why run it at all?”

IBM tried to pivot with the times. During the 2010s, Rometty recast IBM as a cognitive solutions and cloud computing platform company, rallying around “strategic imperatives” like analytics, cloud, mobility, and security. The messaging was modern. The problem was structural: IBM still housed a massive managed infrastructure services business designed for a world of customer-owned data centers.

And the results started to show it. The business that would later become Kyndryl slid from $21.8 billion in revenue in 2018 to $20.28 billion in 2019, then down again to $19.35 billion in 2020. Not a collapse—but a steady, stubborn decline that’s deadly in a business built on long-term contracts and operational leverage.

Even worse was profitability. Infrastructure services were getting commoditized, with competition pushing pricing down and customers expecting more automation for less money. Within IBM, Global Technology Services was running at much lower margins than the consulting side of the house. The infrastructure unit’s pre-tax margin was 5.8% in 2019, compared to 9.6% for IBM’s Global Business Services.

This wasn’t just a shrinking business. It was an anchor. IBM’s “strategic imperatives” could grow, but in consolidated results the legacy infrastructure operation drowned out the story. Wall Street couldn’t see the transformation because the legacy machine was still the largest line item.

Then came the deal that forced the issue.

In July 2019, IBM completed its acquisition of Red Hat—its biggest purchase ever, at $34 billion. The strategic logic was clear: hybrid cloud. Enterprises might not go all-in on public cloud, but they would run a mix of on-prem data centers and multiple public clouds. Red Hat, especially OpenShift, could become the connective tissue.

But Red Hat also sharpened a contradiction IBM could no longer manage. To win in hybrid cloud, you have to partner everywhere—AWS, Azure, Google Cloud. Yet IBM still had its own cloud ambitions, and that made true partnership complicated inside one corporate umbrella. As Stephen Leonard, Kyndryl’s global alliances and partnerships leader, put it: “We couldn’t do it in IBM because we were focused on and committed to only the IBM cloud.”

When Arvind Krishna became IBM CEO in April 2020, the logic hardened into action. In October 2020, IBM announced it would divest the Managed Infrastructure Services unit of its Global Technology Services division into a new public company. This wasn’t a small pruning. The new company—later named Kyndryl—was set to launch with about 90,000 employees, 4,600 clients across 115 countries, and an order backlog of roughly $60 billion. Investors welcomed it, in part because it finally made IBM’s story legible.

IBM framed the business case in simple terms: the two businesses served different customer needs, required different operating models, and needed different talent strategies. Together, they constrained each other. Apart, each could pursue its own path.

Krishna said it plainly: “The separation of Kyndryl is one of many actions we are taking to sharpen our focus on hybrid cloud and AI, leverage a portfolio clearly focused on technology and consulting, and achieve our growth objectives.”

For investors, this was the key inflection point. IBM was effectively acknowledging that its managed infrastructure services business no longer fit the future it wanted to build. Whether the spin created a newly liberated opportunity—or simply pushed the hardest problem out the door with a new logo—was the question Kyndryl would now have to answer on its own.

IV. The Spin-Out: Building Kyndryl from Scratch

Building a $19 billion company from scratch while simultaneously running it—that was Martin Schroeter’s assignment when IBM tapped him to lead the spin in January 2021.

Schroeter wasn’t a mystery pick. He was an IBM lifer with the right scars for the job: CFO from 2014 to 2017, then Senior Vice President of Global Markets from 2018 to 2020, responsible for IBM’s global sales engine and customer relationships. He left IBM in June 2020—before the spin was even announced—then returned months later to run what was, at the time, literally called “NewCo.”

That detail matters. This wasn’t an outsider parachuting in with a turnaround playbook and no context. Schroeter knew the customers, the contracts, and the internal machinery that kept the infrastructure business running. But having a bit of distance also gave him permission to do what many insiders can’t: question the defaults.

The scale of what he inherited was almost absurd. On paper, Kyndryl would launch with around 90,000 employees, about 4,600 customers across 115 countries, and roughly $60 billion in service backlog. In practice, it meant keeping the lights on for banks, airlines, healthcare systems, and governments—while also building an entire standalone corporation underneath them.

Because a spin-off isn’t just a press release and a new ticker symbol. It’s finance and HR systems. Payroll. Treasury. Legal. Procurement. Real estate. Security. IT. Vendor contracts. Compliance regimes in dozens of jurisdictions. The stuff no one celebrates, but everything depends on.

And since this was a separation from IBM, the two companies had to write the rules of the divorce in excruciating detail. Kyndryl entered into a stack of agreements to govern the split and the post-spin relationship, including a Separation and Distribution Agreement, Tax Matters Agreement, Transition Services Agreement, Employee Matters Agreement, Intellectual Property Agreement, Real Estate Matters Agreement, and other supporting arrangements. In other words: “Yes, you’re independent”—but also, “Here are the hundreds of ways we’ll still be intertwined while you stand up on your own.”

The mechanics of the spin landed in early November 2021. On November 3, IBM distributed 80.1% of its Kyndryl shares to IBM shareholders (the “Distribution”). Shareholders of record as of October 25 received one share of Kyndryl common stock for every five shares of IBM common stock they held. IBM temporarily retained a 19.9% stake.

Then there was the name.

IBM revealed “Kyndryl” in April 2021—“Kyn” for kinship and “Dryl” for tendril—and the reaction was, predictably, skepticism. It sounded invented because it was. But Kyndryl had a real branding problem: it was inheriting world-class enterprise relationships, yet it still needed to introduce itself to customers, investors, and even its own employees—many of whom had spent their entire careers thinking of themselves as IBMers. In a business built on trust, familiarity matters. Starting from a blank slate is not a gift.

Which leads to the hardest part of the whole spin: culture.

Kyndryl talked about becoming “flatter and faster,” arguing that its “unrivaled global expertise” in managing and modernizing mission-critical systems positioned it well for a huge and growing digital transformation market. The ambition was clear. The question was whether you could actually turn a workforce shaped by decades of IBM process and hierarchy into something more entrepreneurial—without breaking the very operational discipline that customers were paying for.

And all of this was happening under immediate pressure. Customers had to decide whether a newly independent Kyndryl could be trusted with their most critical infrastructure. Employees had to decide whether to stick around or take a job at a company that felt more stable. And the business had to confront technology debt—years of underinvestment that were easier to ignore inside IBM than to fix in public.

Margins were the other looming issue. Infrastructure services were already under pricing pressure, and Kyndryl was inheriting contracts negotiated under IBM’s umbrella—where scale, procurement leverage, and cross-selling economics were different. As a standalone company, those assumptions didn’t automatically hold.

The market’s first impression wasn’t exactly warm. On Kyndryl’s first trading day, November 4, 2021, the stock opened around $26 per share. Using the NYSE closing prices that day—$120.85 for IBM and $26.38 for Kyndryl—at a 1:5 distribution rate, IBM shareholders effectively received about $5.28 of Kyndryl stock for each IBM share they owned.

The takeaway wasn’t the math. It was the message: investors were treating Kyndryl like a legacy business in managed decline, not a newly liberated company about to reinvent itself.

This was the second big inflection point in the story. The moment the IBM safety net came off—and Kyndryl, carrying decades of services DNA, had to prove it could survive on its own.

V. The Market Reality: Infrastructure Services in the 2020s

To understand Kyndryl’s challenge, you first have to understand the market it competes in—and why it’s both massive and punishing.

Kyndryl is an IT infrastructure services company. It designs, builds, manages, and modernizes the systems that keep large organizations running, with additional capabilities in areas like AI, data, and analytics. When it launched as a standalone company in late 2021, it grouped its work into six service areas: cloud; security and resiliency; network and edge computing; digital workplace; core enterprise and zCloud; and applications, data, and AI.

In plain English: Kyndryl is the team you call when “IT” isn’t a department—it’s a heartbeat.

When a major bank needs its core system to run every second of every day—processing transactions, answering balance checks, handling ATM withdrawals—there is no tolerance for downtime. When an airline needs its reservation system to survive peak travel season without falling over, that’s not a nice-to-have; it’s the business. When a government agency has to keep citizen services online while untangling decades of old infrastructure, the work can’t stop just because the technology is being replaced. These are the kinds of environments where Kyndryl has historically lived.

At the time of the spin, Kyndryl operated in 63 countries and managed around 400 data centers. And it wasn’t serving small customers. At year-end 2020, the business had a portfolio of around 4,400 customers, including about 75% of the Fortune 100. The contracts tend to be long-term and huge—often the kind of engagements where the infrastructure is so central that the client can’t afford to get the transition wrong.

But here’s the economic catch: mission-critical doesn’t automatically mean high-margin.

This work is labor-intensive. Keeping a client’s infrastructure healthy requires people—engineers watching systems around the clock, specialists maintaining hardware and networks, teams coordinating upgrades and migrations. The business scales with headcount, not with software that can be copied endlessly at near-zero cost.

A comparable peer makes the point. DXC Technology—formed in 2017 from the merger of Hewlett Packard Enterprise’s Enterprise Services unit and Computer Sciences Corporation—built its business on large-scale IT outsourcing for big enterprises and public sector clients. It’s also a reminder of what “good” can look like in this industry: tight margins. DXC, despite its scale, has operated around the low single digits, roughly 3% in one snapshot cited here. That number is the tell. Infrastructure services are often a scale game where you fight for share and operational efficiency so you can earn modest profits on enormous revenue.

And it’s not like Kyndryl gets to enjoy that market alone.

Competition comes from every direction. Global firms like Accenture increasingly bundle infrastructure work into broader transformation programs. Indian IT services giants like Tata Consultancy Services, Infosys, and Wipro compete aggressively on cost. And peers like DXC fight in the same trenches, trying to squeeze more efficiency out of similar contract structures.

But the real threat isn’t just other outsourcers. It’s the clouds themselves.

AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud aren’t merely vendors selling servers and storage. They’re selling a different operating model: don’t outsource your data center—get out of the data center. If a company can move workloads to AWS, why hire Kyndryl to run physical infrastructure at all?

That’s what makes Kyndryl’s position so tricky. Even its partnership strategy starts from an uncomfortable truth: the hyperscalers are both collaborators and substitutes. In fact, around December 2021, Kyndryl hadn’t yet struck a partnership with AWS—the market leader at the time, ahead of Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud Platform. (That later changed; Kyndryl has since partnered with AWS.)

Zoom out, and you can see the squeeze. Traditional managed services were built for on-premises infrastructure. But on-prem has been losing favor as enterprises move more workloads to the cloud. Meanwhile, cloud platforms keep adding managed services that reduce the need for a middleman, and lower-cost services firms keep pushing prices down from below. Commoditization is the default gravity of this market.

So for anyone trying to understand Kyndryl, this is the frame: demand will still exist. Big organizations aren’t going to magically become simple, and hybrid environments will persist for a long time. The question is whether Kyndryl can capture enough of that demand, in the right kinds of work, at margins that justify being a public company—or whether it gets trapped between hyperscalers above and low-cost competitors below.

VI. The Transformation Strategy: Schroeter's Playbook

Martin Schroeter and his team faced a question with no clean answer: how do you turn a legacy business that’s been sliding for years into something that can actually grow again—without breaking the reliability that made customers sign those giant contracts in the first place?

Their answer was a simple framework with a lot of heavy lifting behind it: the “Three A’s”—Alliances, Advanced Delivery, and Accounts. It became Kyndryl’s operating system for the turnaround.

Strategic Pillar #1: Alliances with Hyperscalers

The most important move was also the most counterintuitive. Instead of treating AWS, Microsoft, and Google Cloud as the enemy, Kyndryl decided to become their partner.

That was easier said than done. Inside IBM, Kyndryl’s predecessor business struggled to sign deep partnerships with third-party clouds that, in many ways, competed with IBM’s own cloud ambitions. As a standalone company, Kyndryl could finally go all-in on the reality its customers were already living: hybrid and multi-cloud.

Because enterprises don’t migrate to “the cloud” like flipping a switch. They end up with a patchwork—some workloads still on-prem, others on one cloud, others split across multiple clouds, with security, networking, and governance stitched together across the whole mess. Managing that complexity is exactly what Kyndryl has spent decades doing. The twist is that now the mission isn’t “run my data center,” it’s “run my environment,” wherever it lives.

Kyndryl moved quickly. The Microsoft partnership came first in November 2021, almost immediately after the spin. Google Cloud followed in December. AWS came next, with Kyndryl also saying it planned to build its own internal infrastructure in the cloud, using AWS as its preferred provider—along with AWS becoming a Kyndryl Premier Global Alliance Partner.

Stephen Leonard, Kyndryl’s global alliances and partnerships leader, captured what the alliances unlocked: the ability to expand “beyond the IBM universe into the broader industry universe” and build skills and capabilities across platforms like Google and Azure.

Execution showed up in the numbers. Kyndryl went from essentially no hyperscaler-related business at the time of the spin to $1.2 billion in revenue tied to hyperscaler alliances by fiscal 2025. The company expected that figure to reach $1.8 billion in fiscal 2026.

Strategic Pillar #2: Advanced Delivery—Kyndryl Bridge

Partnering with the clouds helped define where Kyndryl wanted to play. The next question was how to deliver the work differently, in a market where “more people on the account” can’t be the only answer.

That’s what led to Kyndryl Bridge, launched in September 2022 as the centerpiece of its Advanced Delivery push. Kyndryl described Bridge as an “as-a-service” operating environment built from its decades managing complex, mission-critical systems—combining a marketplace, an operational management console, and an AI and machine-learning analytics engine.

The promise was straightforward: use software and automation to make infrastructure management less reactive and more predictive. Kyndryl said Bridge generated over 12 million real-time insights per month, spotting patterns, flagging emerging risks, and helping teams address issues earlier. The goal: automatically resolve up to 90% of IT issues.

For a services business stuck in a commoditizing grind, Bridge was also something else: intellectual property. A way to differentiate beyond labor, and a platform that could make Kyndryl faster, cheaper to run, and harder to replace.

Adoption moved quickly. Kyndryl said Bridge had more than 1,200 onboarded customers and 190 service offerings, and that it helped deliver productivity benefits totaling nearly $2 billion per year through avoided major incidents and planned maintenance costs. The company also said Bridge freed up more than 12,300 delivery professionals, generating $725 million of annualized savings.

Strategic Pillar #3: Accounts Initiative

The third “A” was the most painful, and arguably the most necessary: fix the contract portfolio.

Kyndryl inherited deals from the IBM era that weren’t built to be profitable on a standalone basis. Inside IBM, services contracts could be priced aggressively—sometimes at low or even negative margins—to protect broader relationships or support other sales. Kyndryl didn’t have that luxury.

So it started walking away from revenue. It let some contracts run off, renegotiated others, and exited work that couldn’t be made economic. That decision made the near-term revenue line uglier, but it was the price of rebuilding a healthier core.

Kyndryl said its Accounts initiative—focused on addressing contracts with substandard margins—reached $900 million of annualized benefits, surpassing its fiscal 2025 year-end objective of $850 million. And as the portfolio improved, Kyndryl said the projected margins associated with signings in fiscal 2023 increased meaningfully versus the prior year, reflecting a willingness to turn down low- and no-margin business.

Kyndryl Consult: Moving Up the Value Chain

Alongside the Three A’s, Kyndryl placed another bet: it couldn’t just be the operator. It needed to become more of an advisor and a builder—work that’s typically higher value and more differentiated than traditional infrastructure management.

That became Kyndryl Consult. By the third quarter referenced here, Kyndryl Consult revenue grew 26% year-over-year, while signings grew 35% year-over-year in the quarter and 45% over the last twelve months.

Taken together, this was the third major inflection point: Kyndryl stopped acting like a legacy infrastructure outsourcer bracing for decline, and started trying to become a cloud-enabled partner—with better contracts, deeper alliances, and a delivery model designed to scale beyond headcount.

VII. The Financial Journey: From Spin to Stabilization

Kyndryl’s first few years as an independent company read like most real transformations do: you take the pain up front, you look worse before you look better, and you spend a long time proving the turnaround is more than a slide deck.

Year one was essentially survival mode. The business Kyndryl inherited from IBM had already been drifting down for years—revenue had slipped from $21.8 billion in 2018 to $19.35 billion in 2020—and independence didn’t magically reverse that gravity. Kyndryl also changed its fiscal year-end after the split, but the direction stayed the same: revenue declined to $18.32 billion for the 12 months ended March 31, 2022, and then fell again to $17.0 billion for the 12 months ended March 31, 2023.

Year two (FY2023) was where the cost of transformation really showed up. Kyndryl reported a pretax loss of $851 million, driven by transaction-related costs, workforce rebalancing charges, and lease-exit costs. Net loss for the year was $1.4 billion, a net margin of (8.1%). This is the part of the movie where the company is trying to rebuild the engine while the plane is still in the air—and the financials are the turbulence.

Public markets didn’t give Kyndryl much patience. After opening around the mid-$20s at the spin, the stock slid below $10 at its low—more than a 60% drop from day one. It later bounced hard, including an 87% gain in 2023, but that whiplash captured the market’s base case: this could be a value trap until proven otherwise.

By fiscal year 2024 and into 2025, the first real proof points started to appear. For the fiscal year ended March 31, 2025, Kyndryl reported revenue of $15.1 billion, down 6% year-over-year (4% in constant currency). But profitability flipped: pretax income came in at $435 million, versus a pretax loss of $168 million in FY2024. Net income was $252 million, or $1.05 per diluted share, compared to a $340 million net loss the year before.

That swing mattered. For the first time as a standalone company, Kyndryl showed it could produce profits—despite deliberately shrinking the top line by exiting or fixing bad business.

The quarterly cadence reinforced the trend. In Q3 FY2025 (ended December 31, 2024), revenue was $3.74 billion, down 5% year-over-year (3% in constant currency). But earnings improved sharply: pretax income was $258 million and net income was $215 million, compared to a net loss of $12 million in the prior-year period. And in Q4 FY2025, Kyndryl returned to constant-currency revenue growth (+1.3% year-over-year) while margins improved: adjusted pretax income rose to $185 million and adjusted EBITDA increased to $698 million.

In a services business, though, you can’t stop at earnings. Cash is the truth serum—especially when accounting includes lots of restructuring, separation, and one-time noise. In FY2025, cash flow from operations was $942 million, a key signal that the business was generating real, usable cash even while it was reshaping itself.

By late FY2025, management had enough confidence to keep raising its outlook: adjusted pretax income of at least $475 million, adjusted EBITDA margin of at least 16.7%, and adjusted free cash flow of approximately $350 million. It also expected roughly 2% constant-currency revenue growth in the fourth quarter—important not because it’s a huge number, but because it suggests the long slide might finally be bottoming.

Then there’s the leading indicator Kyndryl cares about most: signings. In FY2025, Kyndryl reported $18.2 billion in contract signings, up 46% year-over-year—evidence that customers were buying into the “new” Kyndryl, not just renewing the old one.

Put it all together and the financial story becomes clearer: this was never going to be a one-year fix. The timeline is closer to three to five years. Some of the revenue decline was intentional—walking away from unprofitable work—while the real goal was to rebuild margins and improve the quality of the backlog. And that’s why late 2024 into early 2025 marks the fourth major inflection point: signings accelerated, margins expanded, and a return to revenue growth started to look less like hope and more like a measurable turning point.

VIII. The Competitive Positioning: Can Kyndryl Win?

Kyndryl sits in a weird spot in the industry map: it’s the world’s largest IT infrastructure services provider, yet it’s also a new public company still trying to convince the market it’s not just yesterday’s IBM business with a fresh coat of paint.

The Advantages

In infrastructure services, scale isn’t a vanity metric—it’s table stakes. Kyndryl operates across more than 60 countries and brings decades-long relationships with the kinds of customers that don’t have the luxury of “trying something new” on their most critical systems. If a multinational bank needs one partner that can cover every geography it operates in, the shortlist is short.

Kyndryl also claims a second kind of scale: it’s the world’s largest IT infrastructure services provider, and the fifth-largest consulting provider.

Then there’s the technical depth. A lot of the world still runs on IBM mainframes, especially in finance and government. And while plenty of people can talk cloud, far fewer can actually keep those legacy systems running, secure, compliant, and continuously available. That expertise is hard-earned and increasingly scarce.

Finally, the work itself creates switching costs. When Kyndryl runs a bank’s core infrastructure, replacing it isn’t like swapping a vendor. It’s a high-risk transition that can take years, with real operational danger if anything goes wrong. That creates a moat—though one that can slowly shrink as customers modernize and simplify.

The Disadvantages

The IBM inheritance is a double-edged sword. It comes with trust, access, and institutional relationships. It also comes with a narrative problem: to many outsiders, Kyndryl is the part of IBM that got “shed,” not the part IBM wanted to spotlight.

The cost structure is another headwind. Kyndryl was built inside IBM’s operating model, with the workforce and overhead that came with it. Competing purely on price against Indian IT services firms is a losing game; their labor cost advantages are simply too large.

And then there’s talent. The best engineers increasingly want to work at hyperscalers or high-growth startups, not on the operational grind of decades-old enterprise systems. Kyndryl has to recruit and retain talent in a market that often sees infrastructure management as less glamorous—and sometimes pays less competitively.

Comparison to Peers

DXC Technology is the closest “mirror universe” comparable. It was created on April 3, 2017, from the merger of Hewlett Packard Enterprise’s Enterprise Services unit and Computer Sciences Corporation. At launch, DXC had about $25 billion in revenue. As of November 2024, it employed over 125,000 people across more than 70 countries.

DXC’s early public-market path shows how unforgiving this category can be: shares fell in the first month amid integration concerns, dropped further by three months, then recovered somewhat by six months as the company delivered $500 million in cost synergies. Over a longer arc, DXC saw volatility and pressure—shares fell to $25 by 2022, with the company facing $2 billion of debt and about 5% client churn.

The lesson for Kyndryl is mixed. DXC is proof an infrastructure services spin-off can survive. But it’s also a warning that execution, client retention, and portfolio quality can make or break you—and that “scale” doesn’t guarantee success.

Against Accenture, Kyndryl is fighting uphill on brand and positioning. Accenture gets paid for strategy and transformation, which attracts talent and supports premium pricing. Kyndryl, by contrast, has historically been the operator. The trade-off is that Kyndryl often goes deeper in the infrastructure stack and has credibility with mission-critical workloads that can’t tolerate disruption.

Against Indian IT services giants like TCS, Infosys, and Wipro, Kyndryl’s cost structure is the obvious disadvantage. But it can differentiate through geographic reach, security clearances, and entrenched relationships in heavily regulated industries.

The Hybrid Cloud Opportunity

The strategic hinge for Kyndryl is whether hybrid cloud is a durable destination—or just a waypoint on the road to “everything in public cloud.”

Kyndryl is betting there’s a sustainable middle. Most large enterprises aren’t going all-in on a single public cloud. They’re building hybrid environments for regulatory, latency, resilience, and cost reasons—and they’re increasingly multi-cloud by design. Managing that reality is exactly the kind of complexity Kyndryl knows how to handle, especially when paired with hyperscaler partnerships.

A Forrester Research Inc. survey found that 97% of large enterprises expect to use more than one infrastructure-as-a-service platform in the future. Wikibon estimates that the true private cloud market is about 40% of the size of the IaaS sector, but is growing 50% faster.

If hybrid cloud sticks, Kyndryl can become the adult in the room—the partner that makes messy, multi-platform enterprise environments actually run. If enterprises consolidate more aggressively into public cloud than expected, Kyndryl’s core value proposition gets harder to defend.

IX. Strategic Frameworks: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

At this point in the story, the numbers tell us Kyndryl is stabilizing. The strategy tells us it’s trying to become something new. But the real question is durability: what, if anything, can keep this business from getting competed down to a utility?

Two classic lenses help sharpen the picture: Michael Porter’s Five Forces, which explains why an industry is attractive or brutal, and Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers, which explains what can create lasting competitive advantage inside a brutal industry.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate-Low

In “services” broadly, entry is easy. A few smart people can hang a shingle and call themselves consultants.

But Kyndryl doesn’t make its living on slide decks. It runs mission-critical infrastructure for some of the most regulated, risk-averse organizations on earth. To win that work, you need global delivery at scale, deep security and compliance capabilities, and—most importantly—a track record that makes a CIO comfortable betting their career on you. That’s not something a new entrant can manufacture quickly.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate

Kyndryl is dependent on both technology and people.

On the tech side, it relies on hardware, software, and cloud partners—but it can usually multi-source across vendors, which keeps any single supplier from holding all the cards.

On the people side, leverage shifts away from the company. Skilled infrastructure talent is scarce, competition is intense, and the best engineers have options. In a labor-heavy business, that supplier power matters.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High

Kyndryl’s customers are large enterprises. They buy big, they negotiate hard, and they’re increasingly sophisticated about what infrastructure should cost.

Switching costs still exist—especially in the gnarliest, most embedded environments—but they’ve been trending down as technology stacks modernize and standardize. Every renewal becomes a pricing battleground, and customers use competitive bids to squeeze margin out of the relationship.

Threat of Substitutes: Very High

This is the existential one.

The hyperscalers are not just competitors; they’re a different answer to the same problem. Instead of paying someone to manage your infrastructure, you increasingly rent it as a service. Add in automation, better cloud-native tools, and managed services that reduce human involvement, and the need for classic infrastructure outsourcing shrinks.

Even when Kyndryl wins cloud-related work, it’s often helping customers migrate to platforms that, over time, can reduce the need for Kyndryl.

Industry Rivalry: Intense

Kyndryl fights on multiple fronts: peers like DXC, broad transformation players like Accenture, and cost-focused competitors like the Indian IT services firms. Offerings blur together, differentiation is hard to sustain, and price competition is constant.

Conclusion: Structurally Challenging Industry

Porter’s framework lands in a tough place: buyer power is high, rivalry is relentless, and substitutes keep improving. That combination is why this sector so often produces huge revenue and thin margins—and why Kyndryl can’t afford to be “good enough.” It needs a reason to exist beyond being a competent operator.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Moderate

Kyndryl’s size helps. Scale improves procurement, enables global coverage, and makes it possible to invest in platforms like Kyndryl Bridge.

But this is still a services business. You don’t get software-style operating leverage when delivery requires humans. Scale matters—but it doesn’t magically turn into high margins.

Network Effects: Weak Currently

Most services businesses don’t have network effects.

In theory, Kyndryl Bridge could change that if managing thousands of environments produces data and insights that compound—making the platform better as more customers use it. But today, that’s more potential than proven power.

Counter-Positioning: Potential

This is one of the more interesting angles in Kyndryl’s story.

Hyperscalers are built to standardize and pull customers deeper into their own platforms. Kyndryl is built to live in the messy middle: legacy systems, hybrid estates, multi-cloud governance, and all the edge-case complexity that big enterprises can’t simply delete.

That’s a form of counter-positioning: doing work that the hyperscalers either can’t optimize for—or don’t want to, because it distracts from their core incentives.

Switching Costs: Strong

When you run the infrastructure underneath an enterprise, you build deep integration and institutional knowledge. Replacing you isn’t a vendor swap; it’s a risky, multi-year transition with real downside if anything breaks.

That creates meaningful lock-in—and it’s arguably Kyndryl’s strongest advantage. The catch is that this power can erode as customers modernize and simplify, making future transitions less painful than past ones.

Branding: Weak

Kyndryl is still building its identity.

The IBM legacy gives it credibility in the enterprise—especially in mainframe-heavy industries—but it also carries the stigma of being the part IBM chose to separate. In a trust-driven category, brand strength takes years, not quarters.

Cornered Resource: Moderate

Kyndryl has deep expertise in mainframes and legacy enterprise systems—skills that are increasingly rare.

But it’s also an aging advantage. The cohort that understands those environments is shrinking. The strategic question is whether Kyndryl can translate that legacy expertise into a new “cornered resource” in hybrid and multi-cloud management, not just remain the caretaker of old infrastructure.

Process Power: Developing

If Kyndryl Bridge and its automation efforts actually change the unit economics—fewer incidents, faster resolution, more standardized delivery—then Kyndryl could build a real process advantage: proprietary ways of operating that competitors can’t easily replicate.

That’s the bet behind Advanced Delivery. It’s not guaranteed; it has to show up in sustained margin improvement and customer outcomes.

Conclusion: Switching Costs and Counter-Positioning Are the Base—Process Power Is the Prize

Kyndryl’s most durable strengths today are switching costs and the possibility of counter-positioning against hyperscalers. But neither is enough on its own to create a long-term winner in a commoditizing market.

If Kyndryl works as a turnaround, it will likely be because it turns its scale and operational history into process power—using platforms like Kyndryl Bridge to deliver better outcomes at lower cost, and making itself the default operator for the messy hybrid reality enterprises can’t escape.

X. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

If you’re going to have an opinion on Kyndryl—investor, customer, or employee—you have to be able to argue both sides. This is a turnaround story in a structurally tough market. There’s a very real path to “they pulled it off,” and a very real path to “the industry won anyway.”

Bull Case: Transformation Working

The bull thesis starts with evidence that the plan is actually showing up in results. Management pointed to the combination that matters most in this business: strong signings and expanding margins. As the company put it: "In the third quarter, we delivered another quarter of strong signings growth and significant margin expansion, led by Kyndryl Consult, Kyndryl Bridge and our alliances with hyperscalers. With sustained momentum in our signings coupled with higher operating margins, we remain on track to deliver constant-currency revenue growth in the fourth quarter."

Signings are the clearest leading indicator. If customers are committing to new multi-year work—and doing it at healthier economics—that suggests the “new Kyndryl” is winning in the market, not just managing a slow runoff of IBM-era contracts.

The hyperscaler pivot is another proof point. Kyndryl went from having essentially no hyperscaler-driven business at the spin to generating more than $1.2 billion in revenue tied to those alliances by fiscal 2025. That’s not just a partnership press release. It’s real workload moving through Kyndryl.

The bull case also assumes Kyndryl is right about the end-state of enterprise IT: hybrid isn’t a phase, it’s the permanent condition. For many large organizations, regulatory requirements, resiliency needs, latency constraints, and cost realities mean a meaningful portion of workloads stay on-premises even as cloud adoption grows. If that’s true, then someone has to operate and connect the whole environment—and Kyndryl is built for exactly that messy middle.

Then there’s valuation. The stock has traded at depressed levels relative to many technology services peers, reflecting skepticism about whether this transformation can stick. If Kyndryl proves it can grow again with better margins, there’s upside not only from improved fundamentals, but also from investors simply valuing it more like a viable services platform rather than a melting ice cube.

Finally, the optimistic endgame is that AI and automation change the unit economics. Kyndryl Bridge is the vehicle here: if more of the routine work gets handled through automation and proactive insight, Kyndryl can rely less on brute-force headcount and shift more effort into higher-value activities—improving both cost structure and differentiation over time.

Management has put a stake in the ground with its longer-term targets, including tripling adjusted free cash flow to about $1 billion by FY2028 and doubling adjusted pretax income to $1.2 billion. In the bull narrative, those aren’t fantasies—they’re the natural outcome of better contracts, better delivery, and a business that stops shrinking.

Bear Case: Structural Decline Continues

The bear thesis starts with the uncomfortable possibility that Kyndryl can execute well and still lose—because the category itself is being hollowed out.

Cloud adoption doesn’t need to eliminate on-prem overnight to hurt Kyndryl. It just needs to keep reducing the amount of traditional infrastructure that customers want someone else to run. Even if Kyndryl successfully pivots, the underlying pool of classic managed infrastructure work can keep getting smaller, and the newer work can get priced like a commodity.

That flows into the margin question. Kyndryl inherited an IBM-era cost structure in a world where buyers have leverage and alternatives. Even with automation and portfolio fixes, it may never achieve margin levels that look like premium consulting firms or software companies. The risk isn’t bankruptcy—it’s permanent mediocrity.

Customer attrition is the other lurking threat. The backlog gives visibility, but it doesn’t guarantee loyalty. As contracts renew, customers can rebid, replatform, or carve out pieces of work—especially the newer, cloud-native components where switching is easier and competitors are plentiful.

Talent is another structural headwind. Kyndryl needs modern cloud, security, and data skills at scale, but it’s competing for that talent against hyperscalers, startups, and top-tier consulting firms. Meanwhile, a workforce heavy in legacy expertise can be a strength—until it becomes a constraint.

And then there’s plain execution risk. Pulling off a transformation of this size requires cultural change, a new go-to-market motion, real technology investment, and financial discipline—all at once, while still running critical infrastructure for thousands of customers. History is full of large services businesses that announced a pivot, did some restructuring, and never actually escaped the gravity.

The bear case doesn’t require a dramatic failure. It only requires Kyndryl to remain what skeptics feared on day one: a necessary but unexciting operator in a market with shrinking relevance and squeezed returns.

XI. Recent Developments & Current State

By late 2024 and into 2025, Kyndryl reached the moment every spin-out turnaround is racing toward: not just “we have a plan,” but “the metrics are finally starting to line up.” This was the fourth major inflection point in its young history—the shift from stabilization to something that could plausibly look like durable progress.

The clearest snapshot came in Kyndryl’s third quarter of fiscal 2025, ending December 31, 2024. Revenue was $3.74 billion, and net income jumped to $215 million. More important than the headline profit was what management said was driving it: Kyndryl Consult growing fast, the hyperscaler alliances turning into real work, and enough momentum in signings that the company felt comfortable raising its full-year earnings and cash flow outlook while reaffirming a return to constant-currency revenue growth in Q4.

Under the hood, the quarter showed the direction of travel: adjusted pretax income rose sharply to $160 million, adjusted EBITDA increased to $704 million, total signings grew to $4.1 billion, and hyperscaler alliances contributed $300 million of revenue in the quarter. In other words, the “Three A’s” strategy was no longer just a framework—it was showing up in the operating results.

Then, in November 2024, Kyndryl held its 2024 Investor Day—its first as an independent company. That matters because investor days are usually something confident, steady companies do, not businesses still proving they can stand on their own. Management used the stage to lay out the next phase: the multi-year growth strategy, the financial model it believed Kyndryl could reach, and how it planned to allocate capital as the turnaround matured.

Schroeter framed it as execution catching up to intent: “Since becoming an independent company in November 2021, we've consistently communicated our strategic milestones and executed ahead of plan—positioning Kyndryl for revenue growth, further margin expansion and strong free cash flow generation.”

The targets were ambitious. At Investor Day, Kyndryl said it expected to triple adjusted free cash flow by fiscal 2028 versus fiscal 2025 and more than double adjusted pretax income over the same period. Specifically, it laid out fiscal 2028 objectives of at least $1 billion in adjusted free cash flow, at least $1.2 billion in adjusted pretax income, and an adjusted EBITDA margin of 20% to 22%.

The company also announced its Board had authorized a $300 million share repurchase program. For a turnaround, that kind of move sends a very particular signal: management believes the cash flow is real, and that the business is moving from triage to capital returns—something you rarely see if the foundation is still shaky.

Kyndryl also provided fiscal 2026 guidance that pointed in the same direction: adjusted pretax income of at least $725 million, an adjusted EBITDA margin of about 18%, and roughly $550 million of adjusted free cash flow.

And that brings us to the symbolic milestone Kyndryl has been chasing since day one: the return to constant-currency revenue growth in Q4 FY2025—the first positive growth since the spin-off. It wasn’t huge, but it mattered. In a business that spent years shrinking and then deliberately walked away from bad revenue to rebuild margins, getting back to growth is the proof point that the patient might not just be stable—it might be recovering.

All of it adds up to a company that looks increasingly like it’s executing the plan it laid out. The caution, though, is the obvious one: these are still multi-year targets, and the industry is still unforgiving. Kyndryl’s progress is real—but it only becomes a true turnaround if it can sustain that execution long enough for the model to hold.

XII. The Future: What Comes Next?

From here, Kyndryl’s future isn’t about discovering a new strategy. It’s about proving the one it’s already chosen can hold up over time—and at scale.

Is the Transformation Working?

The recent signal is encouraging: margins have been improving, signings have been strong, and the company finally clawed its way back to constant-currency revenue growth. But this is the trap of every turnaround—early wins can be real and still be fragile. The harder test is whether Kyndryl can keep that momentum through renewals, pricing pressure, and the inevitable operational surprises that come with running the world’s most demanding infrastructure.

The Next Phase: From Stabilization to Growth (2025-2028)

Kyndryl has set FY2028 as the next checkpoint, with a model that implies a meaningfully more efficient company than it was at the time of the spin. The headline ambition is an adjusted EBITDA margin of 20% to 22% by fiscal 2028—up several points from fiscal 2025.

Getting there depends on the same levers that drove the early turnaround, just pushed much harder: growing Kyndryl Consult, expanding hyperscaler alliance work, scaling Kyndryl Bridge across the base, and continuing to manage—or exit—the legacy contracts that don’t fit the new economics.

The AI Opportunity

AI cuts both ways for Kyndryl.

On the upside, it can change the delivery model—automating routine work, predicting incidents before they happen, and freeing engineers to spend time on higher-value projects. Kyndryl has pointed to the AI-enabled Kyndryl Bridge platform as a driver of efficiency, including freeing up more than 12,300 delivery professionals and generating $725 million in annualized savings.

On the downside, AI could also compress the category. If enterprises can run more of their own infrastructure with fewer people, or if hyperscalers package more end-to-end managed services, the need for traditional infrastructure services could shrink faster than Kyndryl’s transformation timeline.

The M&A Question

Kyndryl has two plausible futures on the deal front. It could be an acquirer, using its scale to buy capabilities it doesn’t yet have or to consolidate weaker players. Or it could become a target itself—especially if the turnaround makes its customer relationships and infrastructure expertise look strategically valuable to the right buyer.

Critical Success Factors

For anyone tracking whether this is becoming a durable business, three signals matter most:

-

Signings growth and margin on signings: Bookings are tomorrow’s revenue. The margin profile tells you whether Kyndryl is winning the kind of work it actually wants. Sustained signings growth at high-single-digit pretax margins is a key indicator that the transformation is more than portfolio cleanup.

-

Constant-currency revenue growth: Reported revenue has been pressured by intentional runoff of low-quality contracts. The shift back to positive constant-currency growth is the inflection. Keeping it there is more important than any one quarter’s noise.

-

Kyndryl Consult revenue growth: Consult is the move up the stack—more advisory and build work, less pure “run.” Continued double-digit growth would signal that Kyndryl can compete for higher-value engagements, not just inherit operational work.

The Long-Term Scenario

In the optimistic version of the future, Kyndryl becomes the default operator for the messy hybrid and multi-cloud reality—growing steadily, expanding margins, and throwing off the kind of cash flow that supports buybacks and long-term investor confidence.

In the pessimistic version, the runoff never truly gets replaced. Competition keeps pricing tight, differentiation proves hard to sustain, and Kyndryl ends up as a necessary utility with limited returns.

The base case likely lives in the middle: a viable independent company with a durable, if not spectacular, model—modest growth, improving efficiency, and acceptable returns for investors willing to let a multi-year transformation actually play out.

XIII. Final Reflections & Takeaways

Kyndryl’s story, at its core, is about institutional courage—and the hard limits of what “transformation” really demands.

Start with the audacity of the move. IBM didn’t just spin off a business with roughly $19 billion in revenue. It spun it out while asking it to do the one thing spin-offs usually try to avoid in year one: change everything. Separate from the parent, build a standalone operating model, rebuild a culture, reprice and renegotiate a contract portfolio, and reposition for cloud—all while keeping the lights on for banks, airlines, governments, and hospitals. That’s not a reorg. That’s a high-wire act.

And the reason this story matters isn’t just because Kyndryl is big. It’s because it’s familiar. Across industries, thousands of companies are staring at the same problem: a legacy model that still works… until it doesn’t. Kyndryl is a living case study in what it takes to break from the past without breaking the business.

The Human Dimension

It’s tempting to describe Kyndryl in abstractions: “Three A’s,” “margin expansion,” “hyperscaler alliances.” But those phrases are just labels for the lived experience of about 90,000 people trying to execute a reinvention in public.

Many of them spent their careers as IBMers—IBM email addresses, IBM identity, IBM career ladders. Then, overnight, they were employees of a company with a new name, a new stock ticker, and a future that Wall Street initially assumed would be smaller and uglier than the past. Some leaned into the independence. Others understandably went looking for stability. Holding a services organization together through that kind of identity shock, while still delivering mission-critical uptime, is its own form of operational excellence.

The Investor Perspective

For investors, Kyndryl is the classic turnaround equation: plenty of ways to lose money, and a real—if uncertain—path to making it.

The risks are straightforward. The industry has structural pressure, competition attacks from every direction, and execution is brutally hard at this scale. The early market verdict—shares falling from the mid-$20s after the spin to under $10 at the lows—wasn’t irrational. It was the market pricing in the possibility that this was a melting ice cube with a fresh logo.

But the reward case is equally real. If Kyndryl hits what it’s outlined—by FY2028, $1 billion-plus in adjusted free cash flow and EBITDA margins north of 20%—then the business starts to look less like a runoff story and more like a durable infrastructure operator for the hybrid world. The stock’s sharp rally in 2023 showed how quickly sentiment can swing when investors believe the fundamentals are turning. As of the snapshot cited here, the stock remained below its spin-day close, with a market cap around $4.4 billion—evidence that skepticism hadn’t disappeared, and that upside still depends on sustained proof.

The Closing Question

So, can you teach an old infrastructure company new tricks?

Kyndryl’s early chapters suggest yes—but not quickly, and not cleanly. Reinvention at this scale looks like years of contract triage, cultural rewiring, and building new capabilities while the old engine still has to run.

Lou Gerstner titled his IBM memoir Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance? Kyndryl is attempting a related feat: an elephant born of an elephant, trying to learn a new rhythm in a new arena, without the safety net of the parent.

The proof points have been encouraging: signings have been strong, margins have expanded, and constant-currency revenue growth finally reappeared. But the ending still isn’t written. In an unforgiving industry, progress only counts if it compounds.

For investors, Kyndryl is a live experiment in whether a spin-out can become more than what it was carved from. For operators and strategists, it’s a playbook—warts and all—on how to exit bad business, embrace former enemies as partners, and rebuild a delivery model around automation. And for the people inside Kyndryl, it’s the hardest version of the opportunity: taking something old, making it new, and having to prove it every quarter.

The final chapters remain to be written.

XIV. Further Reading & Resources

If you want to go deeper on Kyndryl—and on the market forces shaping infrastructure services—here are the best places to start.

Primary Sources: - Kyndryl Investor Relations (investors.kyndryl.com) — Quarterly earnings, investor day decks, and SEC filings - Kyndryl 10-K Annual Reports — Full business descriptions, risk factors, and financial detail - IBM Annual Reports (2015-2021) — The cleanest window into Global Technology Services before the spin

Essential Reading: - "Who Says Elephants Can't Dance?" by Lou Gerstner — The origin story for IBM’s modern services strategy, and the context that ultimately created Kyndryl - Gartner Magic Quadrants for Infrastructure Services — A useful map of who competes where, and why - IDC and Everest Group reports on infrastructure services and multi-cloud management — Market sizing, trendlines, and how buyers are changing

Comparable Companies: - DXC Technology SEC filings and earnings calls — The closest comp, with a similar “large legacy services” origin story - Accenture, TCS, Infosys investor materials — Benchmarking against the strategy-led model (Accenture) and the cost-advantaged delivery model (India-based IT services)

Industry Context: - Cloud hyperscaler partner program analyses (Microsoft, AWS, Google) — How alliances work, and what each ecosystem actually rewards - McKinsey reports on IT infrastructure services market dynamics — A broader view of the pressures and opportunities in the category

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music