KAR Auction Services: The Digital Transformation of America's Auto Auction Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

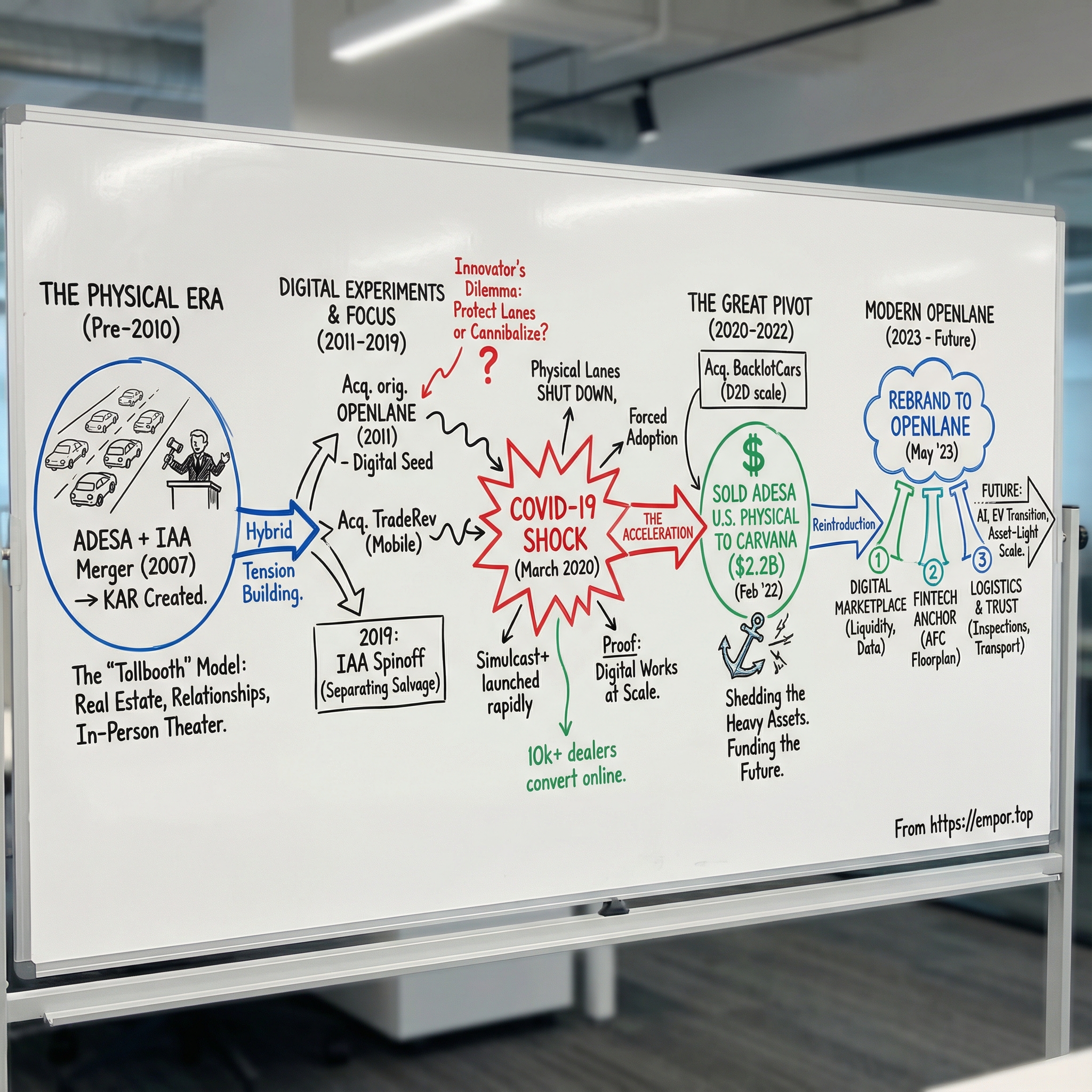

Picture a dusty auction lane in Indianapolis, circa 2007. Hundreds of used cars lined up bumper-to-bumper. Dealers packed in shoulder-to-shoulder. An auctioneer, microphone in hand, machine-gunning out bids in that unmistakable chant. Every week, millions of dollars changed hands through a ritual that hadn’t fundamentally changed in decades. And almost no one in that crowd would’ve believed that, within fifteen years, most of this commerce would move to screens—buyers spread across the continent, purchasing cars they wouldn’t physically see until a transporter dropped them on the lot.

That’s the world KAR came from. And it’s almost unrecognizable compared to what the company is now.

Today, under the name OPENLANE, it’s built to be asset-light and highly scalable: a digital marketplace designed to make wholesale simple for dealers, automakers, and commercial sellers. In 2024, OPENLANE reported $1.81 billion in revenue, up from $1.64 billion in 2023. That same year, it facilitated the sale of roughly 1.4 million vehicles—connecting major automakers, rental fleets, and finance companies with thousands of dealerships all hunting for inventory.

This is the story of how a roll-up of regional, brick-and-mortar car auctions—businesses built on relationships, real estate, and the physical theater of auction day—tried to outrun the future. It’s a story of private equity engineering, strategic reinvention, a few near-death moments, and a pandemic that compressed what should’ve been a decade of digital adoption into a matter of weeks.

The question we’re really asking is simple: how did an old-economy tollbooth for used cars turn into a fintech-enabled digital marketplace? And what does KAR’s transformation teach us about the hardest kind of disruption—the kind you have to do to yourself?

We’ll follow the thread from the 2007 mega-merger that helped create a giant, through the years when digital looked like a side project, to the COVID shock that nearly broke the business—and, in the process, remade it. Along the way, we’ll meet Jim Hallett, the Canadian executive who was fired from his own company and later came back to buy it, and Peter Kelly, the Stanford MBA who co-founded OPENLANE and now runs the enterprise.

Because as “unsexy” as wholesale auctions sound, this market is hidden infrastructure for the entire car economy. When Hertz refreshes its fleet, when Toyota Financial Services processes lease returns, when your local dealer takes a trade-in they can’t sell—all of those vehicles have to go somewhere. If you want to understand how B2B industries actually digitize, this is a great place to look: a massive market, built on trust and logistics, quietly being rebuilt by software.

II. The Used Car Ecosystem & Market Context

To understand KAR, you first need to understand the wholesale auto auction business—one of those invisible industries that moves billions of dollars while most consumers never notice it exists.

In 2024, the US vehicle auction market was estimated at about $3.47 billion, with forecasts projecting it could grow to roughly $4.48 billion by 2030 as more of the process moves online. On the volume side, the market handled about 14.26 million vehicles in 2024. That’s a staggering amount of metal changing hands—mostly out of sight, and almost always between businesses.

Here’s the basic engine. Every year, tens of millions of vehicles need to move from one professional owner to another before they ever land on a retail lot. Off-lease returns pour in from captive finance arms like Toyota Financial Services or BMW Financial. Rental giants like Hertz and Enterprise rotate their fleets—often on roughly annual cycles—which sends a wave of late-model, generally well-maintained cars into the secondary market. These sellers don’t want to negotiate one car at a time. They need a fast, repeatable way to liquidate thousands of units and get clean execution at scale.

Then you’ve got the less glamorous supply: repossessions from finance companies, corporate fleet vehicles being cycled out, and trade-ins that a dealership doesn’t want to retail on its own lot. Repos can happen for a range of reasons—late payments, undisclosed credit issues, or even failure to maintain required insurance coverage. And because the lender’s priority is usually to recover losses quickly, those vehicles can sell for less than a typical retail-ready car.

On the other side of the market are dealers—thousands of them—who wake up every day needing inventory. If you’re a dealership, you’re constantly balancing what your customers want, what you can source, and what you can profitably sell. Wholesale auctions solve that problem by aggregating supply and demand into one place, setting prices through competitive bidding, and charging fees for making the whole thing work.

And “making it work” is doing a lot of heavy lifting. A wholesale auction isn’t just a gavel and a bid. It’s inspection. It’s reconditioning. It’s arbitration when the condition doesn’t match the description. It’s title transfer, which is its own bureaucratic minefield. It’s transportation and storage. And increasingly, it’s financing—because dealers often rely on credit lines to buy inventory quickly.

In the United States, this is also a regulated, dealer-only world. Most states run “closed” auctions, meaning regular consumers can’t participate. As of 2018, there were 139 dealer-only used car auction sites in the US. That matters because it shapes the entire competitive landscape: the customers are professionals, the relationships are long-running, and trust becomes a form of currency—especially when you’re buying a $15,000 vehicle without physically touching it.

Zoom out, and you get a market that’s both concentrated and fiercely contested. In North America, the wholesale auction business has long been dominated by two giants: Manheim Auctions and KAR Auction Services, with estimated market shares of roughly 42% and 27%, respectively. The rest is a long tail—ranging from sizable independents like Connecticut-based Southern Auto Auction down to small one- or two-lane local outfits.

That long tail is exactly what the industry used to be. Before KAR’s rise, auctions were regional and fragmented. A physical site served local dealers. Relationships were built over decades. And if you were a national fleet seller trying to remarket vehicles across the country, you were forced to manage dozens of separate auction partners to get the job done. Fragmentation created friction—and friction created opportunity. If you could stitch together a national network, you could offer enterprise sellers scale, consistency, and a single relationship instead of many.

This is why investors loved the category for so long. Wholesale auctions threw off recurring transaction fees. They benefited from marketplace dynamics—more buyers attracting more sellers, and vice versa. They had real switching costs once dealers established routines, relationships, and credit lines. And crucially, they gave you exposure to the used car economy without taking on the biggest risk in the business: owning the inventory.

In other words, at its peak, this was the ultimate toll booth—positioned right in the middle of America’s used car supply chain.

III. The Pre-History: Insurance Auto Auctions & Jim Hallett Era

KAR Auction Services didn’t start as one business. It started as two parallel machines that looked similar from a distance—both built to move cars efficiently—but served very different kinds of vehicles. One lived in the salvage world. The other ran in the clean-title, retail-ready lane. KAR’s origin story is what happened when those paths began to converge.

Insurance Auto Auctions, or IAA, was founded in 1982 and became a major player in total-loss and specialty salvage. Think of the cars insurance companies write off after accidents, floods, hailstorms, or theft recoveries. IAA’s job was to help insurers process those vehicles and sell them quickly—turn-key, end-to-end. It built a national footprint, with 95 sites across the United States.

The buyers were different too: rebuilders, parts recyclers, scrap dealers. But the underlying playbook was familiar. Aggregate supply from big institutional sellers. Document condition. Handle titles. Coordinate towing, storage, and pickup. Create a marketplace where the right specialized buyers show up and prices can clear.

Running alongside IAA was ADESA, focused on the whole-car market—vehicles that could go back to dealers and eventually to consumers. Headquartered in Carmel, Indiana, ADESA was a wholesale auction operator at scale. And it had something that would become increasingly important as auctions modernized: a financing arm.

That arm was Automotive Finance Corporation, or AFC, which offered floorplan financing to independent dealers. In plain terms, it was inventory lending—credit lines that let dealers buy cars at auction without tying up all their cash. If auctions were the toll road, financing was the fuel card. It made dealers more active buyers, and it gave the auction operator a much stickier relationship.

The person who eventually helped pull these worlds together was Jim Hallett, a Canadian executive with a background that didn’t look like Wall Street—and that was kind of the point. Hallett entered the retail auto business in 1975, eventually owning and managing new car franchises. Then he moved upstream. In 1990, he launched two automobile auctions: Ottawa Dealers Exchange and The Greater Halifax Dealer Exchange.

By his own telling, it was an unlikely route. He studied recreation management at Algonquin College, couldn’t find much work in the field, and took a friend’s advice to try selling cars at Myers Motors in Ottawa. He was good—good enough to break sales records and move into management within 14 months. Not long after, he started his first auction operation outside Ottawa, off Highway 417 in Vars. Halifax followed soon after.

Those Canadian auctions ultimately merged with ADESA, and in 1996 Hallett relocated to Indianapolis to become president and CEO. Under his leadership, ADESA expanded aggressively—growing from 16 to 53 whole-car auctions—and scaled AFC alongside it to better serve dealers. He also pushed ADESA deeper into remarketing by entering the salvage vehicle market in both the United States and Canada.

In 2004, ADESA went public—a milestone that should have been a victory lap. Instead, the next year brought a gut punch. In a 2005 corporate shakeup, Jim Hallett was fired as ADESA’s CEO.

And that’s where this story takes a hard left.

Two years later, Hallett returned—not as an employee, but as the buyer. In 2007, he came back to purchase the company and transform it into KAR Auction Services. His first mission wasn’t a shiny new product or a bold expansion plan. It was simpler: change the culture, and rebuild morale.

“It was a good thing,” he said of being fired. And in hindsight, it set up one of the more unusual comeback arcs in American business: the executive who didn’t just reclaim his seat—he bought the table.

IV. The ADESA Acquisition: Creating an Industry Giant

By late 2006, ADESA was wobbling. After Hallett’s firing, the company had drifted into exactly the kind of organization he hated running: slow, political, and demoralized. Then, as he quietly started lining up backers to buy the business, he discovered something else: ADESA had already put itself on the market.

“The building was not a very happy building,” Hallett said later. From his perspective, he wasn’t just buying auction lanes and real estate. He was walking back into a company that had gone stale—bureaucratic, underperforming, and full of people who didn’t enjoy coming to work.

The timing couldn’t have been more 2006. Private equity was in full swing, and a sponsor group moved quickly. ADESA announced a definitive merger agreement to be acquired by Kelso & Company, GS Capital Partners (an affiliate of Goldman Sachs), ValueAct Capital, and Parthenon Capital. Shareholders would receive $27.85 per share in cash—about a 10% premium to the prior day’s closing price.

But the real masterstroke wasn’t just taking ADESA private. It was what they built with it.

In April 2007, the buyers formed KAR by combining two complementary auction businesses: ADESA, the large-scale whole-car auction operator, and Insurance Auto Auctions, a salvage auction and claims-processing specialist that was already in Kelso’s portfolio. IAA was contributed into the surviving corporation, alongside the deal’s assumed or refinanced debt—bringing the total transaction value, including fees and expenses, to about $3.7 billion.

Hallett came back as CEO. And he came back with a mission that had almost nothing to do with spreadsheets. He talked about transforming the culture in 60 days—then claimed he did it in 30. The point wasn’t the exact number. The point was urgency. KAR needed the organization moving again, and fast.

Operationally, the combined footprint was immediately intimidating: dozens of ADESA used-vehicle auction sites across North America, a sizable salvage presence, and AFC’s network of loan production offices feeding floorplan financing to independent dealers. Put it together and you got a platform that could serve the biggest, most demanding sellers—automakers, captive finance arms, rental fleets—while bundling the services that kept the machine running: auctions, financing, transportation, and reconditioning. Regional competitors could win relationships locally. They couldn’t match that kind of national, end-to-end execution.

Inside the sponsor group, the integration story was straightforward: combine overlapping salvage operations, standardize best practices across ADESA’s used-vehicle locations, and capture both revenue and cost synergies. They also kept buying—tuck-in acquisitions to build density and capability—and made a critical technology move by acquiring OPENLANE, expanding KAR’s web-based auction and digital tools.

Then came the reintroduction to the public markets. In December 2009, KAR completed its IPO, giving the sponsors their exit and giving the company fresh capital—and a public currency—to keep consolidating.

By this point, the industry’s endgame was basically set. On one side was KAR. On the other was Manheim, the giant owned by Cox Enterprises via Cox Automotive—an auction powerhouse with adjacent services like financing, title work, and repairs. Together, the two would dominate wholesale auctions for years, with independent auctions filling in the regional gaps but struggling to offer the national coverage and consistency that large fleet and finance sellers increasingly demanded.

KAR hadn’t just returned from Hallett’s firing. It had come back bigger—built as a national machine, engineered for scale, and positioned in a market that was rapidly hardening into a duopoly.

V. The Golden Years: Physical Auctions at Peak

From 2009 through the mid-2010s, KAR hit its sweet spot. The model was beautifully simple: run the marketplace, take a fee every time a vehicle changed hands, and layer on services that made the whole machine harder to leave. It was the definition of a toll booth business—except the “toll road” was America’s used-car supply chain.

Those years weren’t just good in vibes; they were big in volume. By 2017, KAR was selling more than 3 million vehicles a year and operating a sprawling footprint of roughly 75 auction locations, plus more than 100 AFC finance offices supporting dealers. By 2018, the company was selling even more vehicles and generating $2.44 billion in revenue, with a growing share of transactions already moving through online channels.

The money came from multiple directions at once. There were auction fees charged to buyers and sellers. There was transportation revenue for moving vehicles around the country. There were reconditioning fees for getting cars cleaned up and retail-ready. And there was AFC, earning financing income by funding dealers’ inventory. Each add-on did the same thing strategically: it increased KAR’s share of wallet, and it made the relationship stickier.

If you’ve never been to a physical auction at scale, it’s hard to appreciate how much of the business was built on theater and trust. Dealers showed up early, walked the lots, popped hoods, checked tires, and scanned windshield stickers. Then they packed into lanes where cars rolled through one by one, and auctioneers rattled off bids in that rapid-fire cadence. Dealers barely moved—just a nod, a finger, a tiny hand motion—and thousands of dollars would swing in an instant. Part carnival, part commodities pit.

That physical system also created real competitive advantages. The network of sites was expensive and slow to replicate. Dealers built routines around specific auctions and relationships with local managers. And the infrastructure behind the scenes—transport, reconditioning, title processing, arbitration—wasn’t something you stood up in a weekend. It took years, and it rewarded incumbents.

Investors loved it for the same reason operators did: it looked durable. Volumes rose and fell with the cycle, but the underlying flow of off-lease returns, rental fleet sales, and trade-ins kept coming. Costs were heavily fixed, so incremental volume dropped to the bottom line. And the question “Who’s going to build dozens of new auction sites to compete?” felt, at the time, like a mic-drop.

Hallett didn’t treat it like a finished story. He kept building. KAR rolled up more than 50 wholesale auctions and related businesses, adding density, new services, and international operations in the UK and Europe. Each acquisition reinforced the flywheel: more buyers meant better prices, better prices attracted more sellers, more sellers brought more inventory, and more inventory brought more buyers.

From the outside, it looked like an impregnable franchise.

The only problem was that the very thing that made it so strong—those physical lanes, those sunk costs, that weekly ritual—was about to become the anchor that threatened to slow it down.

VI. First Tremors: Digital Disruption Begins

The first tremors didn’t come from wholesale at all. They came from the consumer side of the used-car world, where startups like Carvana, Beepi, and Vroom were testing a radical idea: people would buy a car online without ever seeing it in person. And once that mental barrier cracked, it raised an uncomfortable question for the auction industry: if retail customers could do this, why wouldn’t dealers—professional buyers—do it too?

Digital tools were already creeping into auctions, but now a new wave of app-based businesses was trying to rewrite the entire experience. Their pitch was simple and painful for incumbents to hear: more convenience, lower fees, and faster ways for dealers to turn trade-ins into cash. For an industry that had moved at a glacial pace for decades, the implication was clear. Change wasn’t coming gradually anymore. It was coming in a rush.

In truth, KAR’s digital story started earlier than most people remember. “KAR catalyzed the digital transformation of remarketing through our acquisition of OPENLANE in 2011,” Peter Kelly would later say. “So it is fitting to anchor the next era of our company—and our industry—on the OPENLANE brand.”

OPENLANE itself began back in 1999, founded by Peter Kelly—a Stanford MBA with an engineering background. Before that, he’d worked in civil engineering at Taylor Woodrow, rising quickly through project management. Then he jumped into automotive and built what amounted to a software layer for wholesale.

The original OPENLANE concept was clean and, for the time, almost counterintuitive: private-label online auctions for captive finance companies—the financing arms of automakers like Ford Motor Credit or Toyota Financial Services. When a lease ended and a vehicle came back, the finance company could offer it first to its own dealer network through a branded, OPENLANE-powered platform, before sending it to a public auction. This “upstream” channel gave dealers first access to attractive off-lease inventory, and it gave sellers more control over outcomes.

Under Kelly, OPENLANE grew from startup to a scaled platform handling more than a million wholesale transactions a year.

So when KAR acquired OPENLANE in 2011, it wasn’t just buying a website. It was buying a different model—and pulling in the executive who had built it. The deal looked prescient. It gave KAR a digital capability that complemented its vast physical footprint.

But culturally, digital still sat in the “nice to have” category. It was treated as a feature that made the physical auction machine stronger, not the thing that might eventually replace it.

Meanwhile, the real pressure was building from entrants with no physical baggage at all. A crop of dealer-to-dealer virtual auction startups appeared, targeting trade-ins and promising guarantees and easier dispute resolution—often with much lower fees than traditional lanes. The space quickly filled with names like ACV Auctions, BacklotCars, EBlock, Manheim Express, and TradeRev, which KAR owned. They were aimed at the dealer trade-in market—an enormous pool of vehicles—and by 2019, these emerging digital auctions were collectively moving hundreds of thousands of cars a year, with plenty of runway.

This was the innovator’s dilemma in its purest form. KAR’s physical sites were both the company’s moat and its ballast. They represented billions in sunk costs. The revenue they produced funded operations—and, importantly, debt service. But a digital-first future wanted a different kind of infrastructure: fewer acres of asphalt and more software, more inspection tech, more seamless logistics, and a cost structure built for speed.

KAR didn’t get the luxury of a clean pivot. It faced a choice: protect the legacy model or start cannibalizing it before someone else did. Jim Hallett and his team tried to thread the needle.

They chose to do both.

VII. TradeRev & AFC: Building Digital Beachheads

KAR’s digital strategy snapped into focus in the mid-2010s, not through some grand internal invention, but by buying its way into a new behavior: dealers using their phones as the auction lane.

The most important move was TradeRev, a mobile-first platform built for the messiest, most time-sensitive part of the wholesale pipeline: dealer trade-ins and commercial consignments. TradeRev was launched in 2009 by CEO and co-founder Mark Endras alongside co-founders Wade Chia, Jae Pak, and James Tani.

KAR first took a 50% stake in TradeRev in 2014. Then, in 2017, it bought the rest—paying $50 million in cash, plus up to another $75 million over four years tied to performance. The logic was straightforward: TradeRev brought a dealer-to-dealer marketplace to complement KAR’s sprawling footprint of whole car and salvage auctions, floorplan financing, and other ancillary services. And it gave KAR a credible shot at a dealer-to-dealer market that represented more than 10 million annual transactions.

TradeRev didn’t just put the old auction online. It changed the cadence. Instead of waiting for the next weekly sale, a dealer could take a trade-in, snap photos, post it, and run a live, one-hour auction from a smartphone, tablet, or desktop. The app was designed to feel familiar—fast-moving, competitive, auction-like—but it pulled the transaction forward in time, closer to the moment the dealer actually needed to make a decision.

Just as importantly, TradeRev wasn’t only a bidding interface. Winning bidders could complete the deal inside the app, with optional inspection, title, and arbitration services. And then KAR layered in the part that turned “a cool app” into a platform: financing and transportation through its own businesses, including AFC and CarsArrive.

That’s where the real strategic leverage showed up. KAR already owned AFC, the floorplan financing operation that funded independent dealers’ inventory purchases. AFC had been in the business since 1987 and specialized in the very customers TradeRev needed most: smaller dealers who live and die by speed, turnover, and access to credit.

Put TradeRev together with AFC and KAR’s logistics network, and you got a bundle that was hard to replicate. Dealers could source inventory, finance it, and move it—all in one workflow. Digital-only competitors could build a marketplace. KAR could build a marketplace with lending and fulfillment attached, creating real switching costs.

KAR was also increasingly explicit about what it was building. “The digital revolution in remarketing has begun, and the acquisition of TradeRev ensures that KAR will maintain its strong leadership position in the mobile app and online auction space,” Jim Hallett said at the time. He wasn’t just selling an acquisition; he was signaling intent: this wasn’t an experiment anymore.

And you can see how the company started to describe itself as the pieces came together. OPENLANE operated across two main segments: Marketplace and Finance. Marketplace covered the digital wholesale platforms in North America and Europe. Finance was AFC—floorplan lending, primarily to independent dealers. Marketplace brought the transactions. Finance anchored the relationship.

By 2017, the portfolio design was becoming unmistakable: physical auctions for cash flow and scale, digital platforms for growth, and financing for stickiness. KAR was trying to run two businesses at once—the mature tollbooth and the future platform—and use the first to fund the second.

It was a smart plan.

It was also a plan that assumed KAR would have time.

VIII. The IAA Spin-Off & Strategic Focus

By 2018, KAR had become an odd kind of conglomerate: two big businesses under one roof, serving two very different worlds.

On one side was Insurance Auto Auctions, or IAA—the salvage engine. Its customers were insurance companies. Its buyers were rebuilders, recyclers, and exporters hunting for totaled vehicles and parts. On the other side was KAR’s whole-car operation—ADESA, OPENLANE, TradeRev, AFC—built around clean-title vehicles moving between finance companies and dealers.

Back in 2007, putting these together made sense. There were clear benefits to scale, shared infrastructure, and a single corporate platform. But by the late 2010s, most of that low-hanging fruit had been picked. The remaining overlap was limited, and the strategic priorities were starting to pull in different directions.

So KAR decided to split.

In early 2018, the company announced it would separate IAA, framing it as a way to unlock shareholder value and give each business more freedom to pursue its own strategy. “Today marks the beginning of a new era for KAR and our investors, employees and diverse customers around the globe,” Jim Hallett, KAR’s chairman and CEO, said at the time.

The separation became real in 2019. KAR completed the spin-off, and IAA began trading as its own public company on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker “IAA.” Existing KAR shareholders kept their KAR shares and received one share of IAA for every KAR share they held, as of the June 18, 2019 record date.

Financially, the split made the contrast even clearer. In 2018, IAA generated about $1.3 billion in revenue. KAR, excluding IAA, generated about $2.4 billion. But more important than the revenue mix was momentum: the salvage business had its own set of tailwinds. Hallett pointed to an expanding international buyer base, favorable scrap prices, and a growing share of vehicles being declared total losses—driven by increasingly sophisticated, higher-dollar cars that were simply more expensive to repair. On a May 8 investor call, he noted that in the first quarter, 19% of vehicles involved in accidents were declared total losses.

That environment was great for IAA. But it wasn’t the same game KAR was trying to win.

For KAR, the spin-off was about focus. It simplified the investor narrative and sharpened the operating agenda: go all-in on the whole-car wholesale market, push harder into digital, and use AFC to deepen dealer relationships. No salvage, no split personality—just one mission: evolve from a physical auction operator into a technology-enabled marketplace for wholesale used vehicles.

And in a market that was getting more digital by the quarter, KAR wanted to move faster.

IX. COVID-19: The Forced Acceleration

Nothing in KAR’s strategic planning could have prepared it for March 2020. As COVID-19 lockdowns rolled across North America, the core of the business—packed auction lanes, weekly in-person sales, the whole physical ritual—shut down almost overnight. For a company built on moving cars through real estate, not routers, it was an existential moment.

KAR moved fast. It paused operations for two weeks, then restarted ADESA auctions as online-only simulcasts, leaning on its existing digital platforms to keep the market moving. Other major auction companies followed, but KAR wanted to be out in front.

On March 20, KAR announced a two-week stoppage of all ADESA physical sale operations, including Simulcast. When the company began restarting sales, Jim Hallett described a first for the business: a fully digital auction operated remotely, with an automated auctioneer and buyers and sellers interacting through the Simulcast platform. He pointed to Simulcast+ as the key enabler—technology that let KAR sell vehicles from locations that were otherwise shut down, and do it without a human auctioneer on a lane.

The timing was almost eerie. KAR had been investing in digital for years, but adoption had moved at the industry’s usual pace: cautiously. Then the crisis hit, and the tooling that had felt like a side bet became the only way to do business. As CFO Subrahmanyam said at the time, KAR had revamped Simulcast a couple years earlier, and just before COVID it launched Simulcast+, a fully automated digital auction experience “including the auctioneer.” ADESA began using it in April, positioning it as a live-streaming environment that was fully digitized and highly automated—built to feel like the real thing, without the room.

What happened next was the kind of behavior change incumbents dream about and fear at the same time. KAR hadn’t run a car down an auction lane since March, yet it sold nearly 650,000 vehicles in the second quarter. More than 10,000 dealers who had been “in-lane” buyers enrolled in and adopted KAR’s digital tools for the first time—bidding from home or the office, skipping travel, cutting dead time, and reducing the physical risk that suddenly mattered to everyone.

Sellers saw upside too. Digital tools gave them flexibility to launch sales from almost anywhere—an auction site, a grounding yard, a dealer lot, even multiple sites at once. KAR reported that digital sales drew more engagement than physical auctions: more attendees, more unique bidders, more unique buyers, and more bids per vehicle. And the buyer base widened. The number of states represented in KAR’s sales jumped about 50% from pre-COVID levels.

This was the great forcing function. COVID accomplished in weeks what might have taken a decade through normal industry persuasion. Dealers who’d sworn they needed to “kick the tires” discovered that condition reports, inspections, and process could carry the trust instead. The adoption curve didn’t bend—it snapped.

And it wasn’t just KAR. At Manheim, the share of inventory sold to digital buyers rose sharply; before shutdowns began in March 2020, it was a bit above 50%, and during the pandemic it climbed far higher.

Underneath the emergency response was something more permanent: a shift in the economics of the industry. Digital auctions were cheaper to operate than physical lanes. They reached broader pools of buyers, improving price discovery. And they weakened the geographic constraints that had defined wholesale auctions for generations.

Hallett put it bluntly after roughly four months of living in that new reality: the last 120 days proved that running vehicles down the lane was a preference, not a prerequisite, for a successful sale—and he hoped the industry would finally embrace the “better, faster and safer” digital alternative.

Then came the leadership handoff that symbolized the change. KAR Global announced that Peter Kelly would become Chief Executive Officer effective April 1, 2021. Kelly had served as president since 2019 and succeeded Jim Hallett, who had led the company as CEO since 2009 and became chairman in 2014.

Hallett framed it as continuity with a purpose: Kelly, he said, was a pioneer who helped ignite KAR’s digital transformation when OPENLANE joined the company nearly a decade earlier—and over the past several years, the two had worked closely to sharpen strategy, evolve the operating model, and extend KAR’s leadership in digital wholesale vehicle markets.

X. The BacklotCars Acquisition & Platform Play

COVID didn’t just push KAR online. It reset the competitive landscape. And KAR wasn’t interested in simply surviving the shift—it wanted to come out of it with more digital gravity than anyone else.

So in September 2020, KAR announced what was, at the time, its biggest digital swing yet: an agreement to acquire BacklotCars, a dealer-to-dealer wholesale platform built for smartphones and web browsers, for $425 million. The deal was expected to close before year-end, pending the usual legal and regulatory approvals.

BacklotCars had been founded in 2015 in Kansas City and had quickly expanded to serve dealers in 46 states. Its pitch was designed around the exact reasons dealers hesitated to buy and sell online: uncertainty and friction. The platform emphasized certified inspections, integrated transportation, and financing options—basically, all the trust-and-logistics scaffolding that physical auctions had traditionally provided in person.

The fit with KAR’s pandemic-era reality was obvious. KAR had just proven it could run the auction business digitally at scale. Now it wanted to deepen that model and widen the funnel—especially in the dealer-to-dealer lane where competition was heating up.

BacklotCars also brought a different transaction style into the portfolio: a 24/7 “bid-ask” marketplace. That complemented ADESA’s live formats, including Simulcast+SM, the fully automated auction platform KAR had launched earlier that year. Together, they gave dealers multiple ways to transact—fast live events when you wanted price discovery, and always-on buying and selling when you just wanted the deal done.

And then there was the physical network—still very much part of the strategy. BacklotCars customers would be able to tap into ADESA’s footprint of 74 facilities, where KAR had been investing to streamline storage, inspections, remarketing, and reconditioning. In other words: digital on the front end, industrial-grade operations on the back end.

“BacklotCars has grown rapidly in the highly competitive dealer-to-dealer space and is the perfect complement to our current capabilities and footprint,” Jim Hallett said. He pointed to Backlot’s leadership, technology, and customer-service model as accelerants—assets that could benefit both customer bases quickly.

The strategic logic ran three ways at once. First, BacklotCars added product and talent—an operating marketplace with real adoption. Second, it neutralized a competitor in a segment that mattered. Third, it created another surface area where KAR could attach what it already did best: financing through AFC and logistics through its transport network.

KAR later completed the acquisition, folding BacklotCars into a growing suite of digital marketplaces that included TradeRev, ADESA.com, and OPENLANE—North America’s largest private-label platform for off-lease inventory.

The direction was now unmistakable. KAR wasn’t trying to build “an online option” for auctions. It was assembling a full-stack wholesale platform—digital marketplaces powered by physical operations, with financing and logistics stitched in—designed to make the easiest workflow the one that kept customers inside KAR’s ecosystem.

XI. The ADESA U.S. Sale to Carvana

Then came the move that stunned the industry. In February 2022, KAR announced it was selling its U.S. physical auction business—its historic crown jewel—to Carvana.

The deal was straightforward and enormous: Carvana would acquire KAR’s ADESA U.S. physical auction operations in an all-cash transaction valued at $2.2 billion. That included auction sales, operations, and staff at 56 ADESA U.S. vehicle logistics centers, plus exclusive use of the ADESA.com marketplace in the U.S. KAR’s message to investors was just as clear: this wasn’t a retreat. It was a deliberate acceleration of the company’s digital strategy, with the proceeds earmarked to reduce corporate debt.

Peter Kelly, now CEO, framed it as the logical endpoint of what KAR had been building for years. KAR, he said, had been a leader in the digital transformation of remarketing—and this transaction positioned it as a premier digital marketplace provider for wholesale used vehicles. The company’s bet was that the future of wholesale wasn’t lanes and acreage. It was software, workflows, and services stitched together around digital transactions.

What Carvana got, in exchange, was real industrial muscle. The acquisition handed over the keys to 56 ADESA sites across the U.S., totaling about 6.5 million square feet of buildings spread across more than 4,000 acres. ADESA U.S. had been the second-largest provider of wholesale vehicle auction solutions in the country, with about 4,500 corporate and operations team members. In 2021 alone, the business facilitated more than 1 million transactions through those physical sites.

KAR’s strategic logic was bold and a little counterintuitive for a company that had spent decades building physical density: sell the infrastructure, keep the marketplaces.

After the sale, KAR said it would continue operating OPENLANE, the private-label platform supporting more than 40 programs representing roughly 80% of North America’s off-lease inventory. It would also keep its fast-growing digital dealer-to-dealer businesses—BacklotCars and CARWAVE in the U.S., and TradeRev in Canada—all of which posted double-digit growth in 2021. And it would retain ADESA Canada, ADESA U.K., and ADESA Europe, along with affiliated inspections, transportation, and other service brands, including AFC, its floorplan financing business.

“This transaction will enable a leaner, more nimble operating model and faster long-term growth rate at KAR,” Kelly said.

He also underlined the bigger trend: off-premise sales had been climbing for a decade and already represented more than half of KAR’s vehicle sales. In his view, the industry was still early in the shift—and the momentum was only picking up.

For Carvana, the rationale was equally direct. Buying ADESA U.S. delivered instant scale in reconditioning and logistics—capabilities essential to Carvana’s consumer business. The two footprints were positioned as highly complementary, and Carvana argued that ADESA’s existing and potential reconditioning operations could add meaningful capacity at full utilization. The combined network also expanded reach: by Carvana’s estimate, a large majority of the U.S. population lived within 100 miles of either an ADESA U.S. site or an existing Carvana inspection and reconditioning center, setting up faster delivery times and broader vehicle access.

Back home in Indiana, the human impact was immediate. When KAR announced the pending agreement on Feb. 24, it said approximately 4,500 ADESA and KAR employees would transition to Carvana, including more than 1,000 based in central Indiana across the Carmel headquarters and the Plainfield auction operation.

And with hindsight, the timing looked smart for KAR. Carvana soon faced mounting debt and operational challenges, while KAR came out of the transaction leaner and more focused. The proceeds reduced debt and gave the company more room to invest behind the digital platforms it had spent the prior decade assembling.

XII. Modern OPENLANE: The Digital Marketplace Era

By the spring of 2023, KAR had done the thing most legacy companies talk about and few actually finish: it made the transformation real on the outside.

In May 2023, KAR Global rebranded to OPENLANE—the same name as the digital platform Peter Kelly had co-founded back in 1999, and the platform KAR had acquired in 2011. The company said the change reflected its shift to a more asset-light, digital marketplace model, and a simpler, more customer-first way to buy and sell wholesale vehicles. OPENLANE would now serve as both the parent brand and the go-to-market brand across the U.S., Canada, and Europe. The corporate name change to OPENLANE, Inc. took effect May 15, 2023.

Kelly framed it as a full-circle moment. KAR, he said, had helped catalyze the digital transformation of remarketing through its acquisition of OPENLANE in 2011—so anchoring the next era of the company on the OPENLANE brand was fitting.

The rebrand wasn’t just a logo swap. It came with a plan to merge what had become a sprawling set of marketplaces into fewer, clearer experiences.

In Canada, the company said the first OPENLANE-branded marketplace would launch as it combined the existing ADESA and TradeRev platforms beginning in June 2023. In the U.S., it had already integrated CARWAVE into BacklotCars in 2022 and was rolling out a new live-auction format nationally. The next step was to integrate its U.S. dealer-to-dealer and off-lease platforms into a combined marketplace branded OPENLANE. In Europe, it had completed consolidation of ADESA Europe, ADESA U.K., and GWListe dealer-to-dealer technology into a single marketplace that was also expected to adopt the OPENLANE name.

The result is a company that looks nothing like the KAR that came out of the 2007 leveraged buyout. Today’s OPENLANE is built around digital wholesale marketplaces, not physical auction lanes, and it competes across North America and Europe against a mix of online and traditional providers.

In 2024, OPENLANE facilitated the sale of about 1.4 million used vehicles—roughly 826,000 commercial units and 620,000 dealer consignment vehicles—up 9% from the year before.

Financially, 2024 total operating revenue was $1,788.5 million, up 5% year over year, driven by higher auction fees and purchased vehicle sales. Gross profit rose to $393.4 million, up 7%, attributed to higher auction and service volumes and cost savings initiatives. Operating profit was $182.2 million, compared to an operating loss of $135.8 million in the prior year, reflecting a gain on the sale of a business and the absence of goodwill impairment charges.

Underneath those results is the clearest signal of the transformation: the way the company makes money has changed. OPENLANE now pulls revenue from auction fees on its digital marketplaces, subscription and SaaS fees tied to technology services, financing income from AFC, and ancillary services like transportation and inspections. With more of the system running through software instead of owned auction real estate, the model is designed to be more capital efficient—and, over time, structurally higher margin.

Management also pointed to momentum in the marketplace itself. In the fourth quarter, the company said it grew consolidated revenue by 12% and consolidated adjusted EBITDA by 18%, driven mainly by a 9% increase in Marketplace volumes. It described this as the seventh straight quarter of year-over-year volume growth in its Marketplace segments, including a 15% increase in dealer volumes.

Of course, going digital didn’t make the market less competitive—it made it more competitive.

OPENLANE faces a crowded field, with competitors spanning digital-first marketplaces and adjacent auction giants. The company’s top rivals are often cited as ACV Auctions, Copart, and CarLotz.

ACV Auctions, in particular, has become the emblem of the new era: a digital-first dealer-to-dealer marketplace paired with transportation, data, and capital services. It was built to disrupt the physical-auction model long dominated by Manheim and ADESA, and it has steadily gained share by moving fast on product and dealer workflow.

In other words: OPENLANE didn’t escape competition by leaving the lanes. It simply moved the fight to the screen.

XIII. The Playbook: What OPENLANE Teaches Us

OPENLANE’s transformation is a useful case study in what it takes for a legacy business to survive digital disruption. This wasn’t a Silicon Valley rocket ship. It was an industrial, relationship-driven company that had to reinvent itself without breaking the services its customers relied on.

On Business Model Transformation:

OPENLANE pulled off one of the hardest feats in business: it ran two operating models at the same time—physical and digital—without letting either one implode. That takes more than ambition. It takes clarity about what each model needs, discipline about where you invest, and the stomach to make irreversible moves when the moment arrives. Selling ADESA U.S. wasn’t just a portfolio tweak. It was a decision to stop defending the old center of gravity and commit to the new one.

Timing mattered just as much as strategy. Push digital too early, and you’re paying for infrastructure and software before customers are ready to change their habits. Wait too long, and the market moves on without you. KAR threaded the needle by steadily building digital capability while the physical business still paid the bills—then accelerating hard when COVID forced the entire industry to adopt new behaviors.

And acquisitions weren’t side quests; they were the engine of the transition. TradeRev, BacklotCars, and the original OPENLANE platform didn’t just add features. They brought proven products, teams who knew how to build and operate digital marketplaces, and positions in segments KAR needed to win. In many ways, the company bought its way into digital competence faster than it could have built it.

On Marketplace Dynamics:

In marketplaces, liquidity is oxygen. OPENLANE’s advantage came from assembling enough supply—fleet sellers, OEMs, captive finance arms—and enough demand—thousands of dealers—to make the market reliably clear. Digital reduced the tyranny of geography, but it didn’t eliminate the underlying rule: the platform with the most consistent buyers and sellers becomes the default place to transact.

Trust is the other make-or-break ingredient, especially when the ticket size is measured in thousands of dollars and the buyer may never see the vehicle until it arrives. OPENLANE invested in the unglamorous machinery that makes digital work: condition reports, arbitration, and guarantees that lower the perceived risk of buying sight-unseen. As more volume moved online, those trust systems became a core product, not an add-on.

And the combination of financing and logistics created real differentiation. AFC’s floorplan financing isn’t just a revenue stream; it’s a relationship anchor. Dealers don’t casually switch the lender that funds their inventory. Layer in transportation and reconditioning, and the marketplace starts to look less like a website and more like an operating system—harder for point-solution competitors to match.

On Industry Evolution:

B2B markets usually change slowly—until they don’t. Wholesale auctions resisted digital for years, partly out of habit and partly because the physical process solved real problems. Then COVID forced adoption at scale. And once dealers learned they could buy efficiently from anywhere, the clock didn’t rewind.

That’s also the moment when physical assets can flip from moat to weight. In a lane-based world, ADESA’s network was a strategic advantage. In a digital-first world, those sites were fixed costs that didn’t flex with demand. The sale to Carvana was an acknowledgment that what once created defensibility could, in a new model, drag performance down.

Finally, don’t underestimate the moat created by paperwork and compliance. Title transfer, transportation rules, dealer licensing, and state-by-state requirements are friction for newcomers and muscle memory for incumbents. OPENLANE’s decades of operating experience in that complexity remains a meaningful advantage—especially as the industry tries to digitize processes that were never designed to be digital.

XIV. Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM-HIGH

Digital has made it meaningfully easier to start a dealer-to-dealer platform. You don’t need acres of asphalt and auction lanes anymore. A new entrant can stay asset-light, rely on contractors for inspections, plug into shared transportation networks, and be “live” quickly. That’s why we’ve seen a wave of DTD startups pull in huge venture rounds: the prize is to get liquidity first, then let network effects do the hard work of keeping buyers and sellers loyal.

But there’s a catch. The same go-to-market playbook that helps them scale—subsidizing fees, offering incentives, spending heavily to recruit dealers—can pressure profitability as the market gets crowded.

ACV Auctions’ successful public offering proved that digital-native competitors can reach real scale. Still, OPENLANE and the incumbents aren’t defenseless. Long-standing relationships with major commercial sellers matter, and the industry’s regulatory plumbing is real friction: dealer-only rules, bonding, and state-by-state compliance don’t prevent entry, but they slow it down and raise the cost of getting it right.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MEDIUM

On paper, sellers have options. Rental companies, OEMs, and banks can route vehicles through multiple channels. And the biggest fleets—think Hertz and Enterprise—have enough volume to negotiate hard.

In practice, though, most of this inventory needs to move fast. Off-lease returns and repossessions are time-sensitive, and delays are expensive. That urgency limits supplier leverage. At scale, execution becomes the product: consistent demand, predictable sale outcomes, and a clean operational process. That’s where OPENLANE’s size can make switching feel risky and costly for sellers—even if alternatives exist.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM

Dealers are numerous and fragmented, which keeps any single buyer from dictating terms. But the balance shifts when you’re talking about the biggest dealer groups, like AutoNation or Lithia. They can negotiate and they can move volume.

Meanwhile, digital has changed the buyer experience in a way that naturally increases leverage: it raises price transparency and makes it easier to shop across platforms. OPENLANE can still create switching costs—especially through AFC financing relationships and workflow familiarity—but compared to the old in-lane world, those costs are trending downward as the market standardizes around screens and clicks.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM-HIGH

There are plenty of ways for wholesale vehicles to change hands without going through a traditional auction-style marketplace. Dealers can sell directly to other dealers—something OPENLANE actually facilitates through TradeRev. OEM certified pre-owned programs can keep vehicles inside branded channels. And consumer-to-dealer sourcing, like CarMax and Carvana buyback programs, can feed dealer inventory through alternative paths.

The reason auctions and digital wholesale platforms still matter is trust at scale. Condition confidence, arbitration, title processing, and logistics are hard to replicate consistently. Those advantages keep a lot of volume flowing through the established channels, even as substitutes proliferate.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Competition is intense, and it’s getting sharper as more of the business moves online. The legacy heavyweight is still Manheim/Cox, and Cox’s advantage isn’t just the auction network—it’s the broader automotive stack, including assets like Autotrader, Kelley Blue Book, and Dealertrack.

Digital-first rivals are also forcing the pace, especially ACV Auctions. Even when near-term guidance shifts—like adjustments tied to dealers holding inventory amid tariff uncertainty—the underlying fight is over product, liquidity, and dealer workflows. And it’s worth remembering that growth rates don’t always mean the same thing across platforms; geography, seller mix, and vehicle types can make one company’s numbers look better without proving a structural advantage.

As transparency rises, price competition tends to follow. That pushes everyone toward differentiation in the places that are harder to copy: technology, integrated financing, dispute resolution, and end-to-end service breadth.

Overall Assessment: MEDIUM Industry Attractiveness

This is still a big, durable market with tailwinds—an aging vehicle fleet, constant churn from leases and fleets, and a long runway to digitize messy processes. But the same shift that’s expanding the opportunity is also tightening the screws. Technology disruption has lowered barriers, rivalry is rising, and margin pressure is real. The winners will be the platforms that can pair liquidity with trust—and do it profitably.

XV. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: STRONG (Historically), WEAKENING

In the physical era, scale was everything. The more cars you ran through your lanes, the more you could spread fixed costs across the operation: facility utilization got better, transport routes got denser, and your teams got sharper from sheer repetition.

But digital changes what “scale” even means. A cloud marketplace doesn’t get meaningfully cheaper because you own more asphalt in more zip codes. Geographic coverage still matters for inspection and transport, but the old, crushing advantage of a massive physical footprint is less dominant than it used to be.

Where scale still bites is data and capital. More transactions mean better pricing models, stronger fraud detection, and better matching. And AFC benefits from classic financial scale too: a larger lending portfolio can lower the cost of capital and improve unit economics. Still, compared to the peak-lane era, scale economies aren’t the whole moat anymore.

2. Network Effects: MODERATE-STRONG

OPENLANE is still running a two-sided marketplace, and the core flywheel hasn’t changed: more buyers bring better prices, which attracts more sellers, which pulls in more buyers.

The difference is density. Physical auctions created local gravity—dealers would cluster around a site because it was convenient, familiar, and full of inventory. Digital relaxes those geographic constraints, which is great for reach, but it can also spread liquidity thinner across more platforms.

And there’s one hard reality that keeps this from being a pure software marketplace: cars still have to move. Transportation, timing, and geography still create friction. That physical constraint puts a ceiling on network effects compared to markets where the “product” is purely digital.

3. Counter-Positioning: WEAK

For much of the last decade, OPENLANE was the incumbent being counter-positioned against. Digital-first competitors like ACV could credibly say: we’re built for mobile, built for speed, and not weighed down by legacy facilities and legacy behavior.

OPENLANE’s answer—investing in digital, then ultimately selling ADESA U.S.—was the right move strategically, but it wasn’t free. Self-disruption is expensive.

Now the company is trying to flip the script: instead of competing as “just another marketplace,” it’s leaning into a full-stack posture—marketplace plus financing plus logistics. That’s a counter-position of its own, aimed at point-solution rivals. Whether it lands depends on how much customers value an integrated workflow versus picking best-of-breed tools.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE

The biggest real switching cost is AFC. Dealers don’t casually replace the lender that funds their inventory. Changing floorplan providers can disrupt cash flow, approvals, and day-to-day rhythm.

There are also softer switching costs: platform familiarity, integrations into dealer operations, and the trust you build through arbitration history and past transactions.

But digital cuts the other way too. It’s far easier to try a new app than it ever was to change your weekly routine and start driving to a different auction site. So while OPENLANE has switching costs, the category overall is trending toward lower friction and more experimentation.

5. Branding: MODERATE

ADESA and OPENLANE are known names in wholesale. That matters in a market where buyers are wiring large sums for vehicles they may not see until delivery.

Still, this is B2B. Brand helps, but it doesn’t win on its own. Dealers care less about emotional connection and more about execution: accurate condition, predictable arbitration, reliable title processing, and vehicles that show up when promised.

So branding isn’t OPENLANE’s primary power—but reputation is meaningful insurance in a business built on trust.

6. Cornered Resource: WEAK

OPENLANE doesn’t have a single, untouchable resource competitors can’t pursue. It doesn’t have exclusive licenses others can’t get, and the physical sites that once felt like an irreplicable asset have largely been sold.

Relationships with large commercial sellers are valuable, but they’re not strictly exclusive. Those sellers can and do multi-home.

The closest thing to a cornered resource is data: transaction history, pricing behavior, and condition-report learnings accumulated over years. That’s defensible in the sense that it takes time to replicate—but it’s not uncopyable. Competitors can build their own datasets if they win enough volume.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

This is the unglamorous advantage that tends to matter most in the real world. OPENLANE has decades of operational muscle in the stuff that breaks marketplaces when it’s done poorly: vehicle logistics, reconditioning, arbitration, title transfer, and navigating transportation and regulatory complexity.

Running a hybrid operation—digital front end with physical execution behind it—creates complexity. And complexity, done well, can be a moat: it’s hard for a newer competitor to replicate quickly, even if they have a great interface.

Dominant Powers: Network Effects + Switching Costs (from AFC) + Process Power

Strategic Implication: OPENLANE’s moat is narrower than it was when physical auctions were the center of gravity. To keep strengthening defensibility, the company has to compound the advantages that still scale in a digital world: data quality, financing-led stickiness, and an integrated platform where marketplace + logistics + capital feels like the default workflow—not an optional bundle.

XVI. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

OPENLANE has, in large part, pulled off the thing incumbents rarely manage: it made the painful pivot before the market made it for them. By choosing to cannibalize the physical model and commit to digital, it survived what could’ve been an existential threat—and came out with a business built for how wholesale actually works now.

The full-stack platform matters. Plenty of competitors can run an auction. It’s much harder to wrap that auction in the infrastructure dealers actually need to move inventory: AFC floorplan financing, transportation, inspections, and reconditioning. If OPENLANE makes the bundled workflow meaningfully easier than stitching together point solutions, it can win on convenience and reliability, not just price.

The used-car market itself has durable tailwinds. With tens of millions of used cars sold annually in the U.S. and an aging vehicle fleet, wholesale volume should keep churning. And the EV transition could extend the usable life of vehicles if battery longevity holds up, keeping more units circulating through the secondary market for longer.

AFC is the relationship anchor. Dealers who rely on floorplan financing don’t casually switch lenders, and that stickiness creates recurring revenue plus a natural channel for cross-selling marketplace services.

The asset-light model should improve capital efficiency. Without the same burden of maintaining a massive network of physical auction sites, OPENLANE can direct more resources toward software, data, and customer experience—and, over time, expand margins if it maintains enough pricing power.

Finally, data can compound. Every transaction adds another data point: pricing, condition outcomes, dispute patterns, buyer behavior. If OPENLANE uses that to sharpen pricing, reduce surprises, and improve trust, the marketplace becomes better with scale—one of the few advantages that actually grows stronger in a digital world.

Bear Case:

Commoditization is the obvious threat. As more digital platforms compete for the same dealers, the product risks becoming interchangeable: a set of listings and a bid button. When switching is easy and price transparency is high, margins can compress fast.

Market share is also clearly up for grabs. ACV Auctions and other digital-first players have proven they can grow quickly, pulling dealers into new workflows and chipping away at incumbents’ historical advantages. Momentum in dealer-to-dealer, in particular, can shift faster than the legacy auction world ever did.

Dealer consolidation could reshape buyer power. Large dealer groups may decide they don’t need marketplaces as much as they used to, building direct sourcing networks or negotiating straight with fleet sellers—routes that bypass auctions entirely.

OEMs have their own incentives too. Certified pre-owned programs and other direct-to-dealer strategies can keep vehicles inside branded channels longer, potentially reducing the flow that hits open wholesale marketplaces.

And while OPENLANE has become digital-first as a company, it’s still competing against firms that were born that way. Technology leadership isn’t guaranteed. A faster product cycle, better inspection tools, or a superior dealer experience elsewhere can pull liquidity away.

The EV transition is another wildcard. Battery condition is harder to assess than a conventional powertrain, reconditioning requirements are different, and some OEMs may push harder to control EV resale channels. Any of those could pressure the traditional wholesale model.

Key Metrics to Watch:

-

Marketplace Volume Growth: The oxygen of the business. Watch dealer volume (more repeatable) versus commercial volume (often lumpier).

-

Take Rate / Revenue per Transaction: A proxy for pricing power. If competition intensifies, this is where it will show up first.

-

AFC Loan Portfolio Growth and Credit Quality: Growth signals deeper dealer relationships; credit quality shows whether that growth is being underwritten responsibly.

XVII. Epilogue: The Road Ahead

OPENLANE entered 2026 as a fundamentally different company than the KAR Auction Services that went public in 2009. The transformation—from running physical auction lanes to operating a largely digital marketplace platform—was no longer a slide-deck aspiration. It was the business.

But finishing the pivot doesn’t mean the story is over. It just means the battleground has changed.

Management’s message going into 2025 was essentially: we can keep investing and still grow. In its guidance, the company pointed to confidence that it could grow revenue and adjusted EBITDA at the same time—building on what it said it achieved in 2024. The pitch to investors was straightforward and consistent with the rebrand: OPENLANE is an asset-light, scalable marketplace focused on making wholesale easier for dealers, manufacturers, and commercial sellers. It believes the addressable market remains large across North America and Europe, and that it’s well positioned on both the Dealer and Commercial sides of the house. It also framed technology speed as a differentiator—shipping new products and features quickly—and positioned AFC, its floorplan finance business, as both a category leader and a major source of synergy with the marketplace.

The next decade’s biggest external variable is the EV transition—and it cuts both ways. Electric vehicles don’t recondition like internal combustion vehicles. Battery condition assessment is harder, the tooling is still evolving, and buyers care deeply about degradation in a way that doesn’t have a perfect analog in the ICE world. That complexity could be an opening for new specialists. Or it could be a chance for OPENLANE to build a real edge if it develops EV inspection and battery confidence faster than the rest of the market.

At the same time, OEM strategies are shifting. Direct-to-consumer models represent a long-term structural risk: if automakers increasingly sell new vehicles directly and control more of the resale channel, the flow of off-lease vehicles into open wholesale marketplaces could shrink over time.

And yet, the competitive reality is messy—not a clean “OEMs take everything” narrative. On one hand, in March 2024, OPENLANE, Inc. entered an exclusive partnership with Stellantis to host weekly auctions of young, ex-rental vehicles (including EVs and PHEVs) exclusively on its platform, opening access to premium inventory for its 125,000 dealers across Europe and beyond. On the other hand, the digital-native competition keeps sharpening its tools: in October 2024, ACV Auctions Inc. introduced its analytics suite, ACV MAX and ClearCar, during the Digital Dealer Conference & Expo.

Then there’s AI, which may end up being the quiet force that matters most. If you can automate condition assessment, tighten pricing and forecasting, improve fraud detection, and personalize inventory recommendations, you don’t just make the marketplace nicer—you make it safer and more predictable. And in this business, predictability is a product.

That brings us to the real identity question hanging over OPENLANE: is it a marketplace, a fintech company, a logistics business, or all three? The answer matters because each archetype tends to be valued differently. Marketplaces can earn premium valuations when network effects are strong. Fintech can produce recurring income, but comes with regulatory and credit considerations. Logistics is operationally hard, but it’s sticky when you do it well.

Jim Hallett, looking back on the arc he helped shape, framed it less as category theory and more as a transformation story. "I am so proud of what we have accomplished at KAR, and it has been a true honor to serve our company, customers and industry over the last 47 years," he said. "Each day I was humbled by the passion, energy and grit of our employees, and grateful for their dedication to our customers. Together, we transformed KAR's brick-and-mortar business into a global digital marketplace for used vehicles. I have never been more confident in KAR's strategy and leadership, especially with Peter at the helm—aside from being a great leader, he's the best digital mind in our industry."

In practice, OPENLANE’s bet looks like “all three”: a full-stack system that combines marketplace liquidity, AFC financing, and the operational backbone required to move cars and resolve disputes. If it executes, that integration creates the kind of switching costs and compounding advantage that point-solution competitors struggle to match. If it can’t integrate cleanly, the risk flips: specialists win each layer, and OPENLANE gets squeezed into the middle.

XVIII. Closing Thoughts

The story of KAR Auction Services, now OPENLANE, sits right on the hardest fault line in business: do you protect the thing that made you great, or do you disrupt it before someone else does? Most companies don’t survive that choice. They either cling to the legacy model until it’s too late, or they pivot so early and so clumsily that they torch the cash engine before the new one can run.

OPENLANE managed the rare balancing act. For more than a decade, it built digital capabilities while still sweating the physical network. Then COVID hit, and what had been “the future” became the only way to operate. When the moment arrived to make the irreversible call—selling ADESA U.S. to Carvana—it wasn’t jumping into the unknown. The digital infrastructure was already there to carry the business forward.

There’s also a broader point here: B2B transformation stories don’t get the same spotlight as consumer disruptors, but they’re often the better case studies. You can’t growth-hack your way into trust when every transaction is expensive, regulated, and operationally messy. Liquidity doesn’t come from clever ads; it comes from execution, consistency, and a process that works when something goes wrong. OPENLANE didn’t transform in fifteen months. It did it over roughly fifteen years, one workflow and one acquired capability at a time.

The marketplace parallels are real. Like eBay growing from a simple exchange into an e-commerce platform, and like Airbnb expanding beyond bookings into a broader ecosystem, OPENLANE is trying to move from “we run transactions” to “we run the system.” The playbook is familiar: earn the right to be the place where deals happen, then expand into the adjacent value pools—financing, logistics, data—that make the relationship stickier and the revenue more resilient.

The final takeaway is simple: infrastructure businesses can transform, but it takes courage, capital, and patience. Hallett buying back the company that fired him and steering it toward digital took courage. Years of investment in platforms, inspections, logistics, and finance took capital. And the long arc—from the original OPENLANE founding to a full corporate rebrand—took patience.

For investors looking at OPENLANE now, the question isn’t whether the pivot happened. It did. The question is whether the new model can keep compounding in a tougher, more transparent, more competitive market. The early signals have been positive—growth, improved profitability, and real traction in digital volumes—but the battlefield is crowded, and the work of reinvention never really ends.

In the end, this is a story about survival by self-cannibalization. A company built around physical lanes and weekly rituals chose to bet on screens, software, and a wider network of buyers and sellers. It didn’t happen by accident. It happened because leadership saw the future coming—and decided to meet it head-on, even when that meant letting go of the past.

XIX. Further Reading & Resources

Top References:

-

KAR/OPENLANE Annual Reports & Investor Presentations (2015-2024) - The cleanest way to track how the strategy, financials, and narrative shifted as the company moved from lanes to software.

-

ACV Auctions S-1 IPO Filing (2021) - A competitor’s-eye view of how the wholesale auction market works, what matters in digital, and where the profit pools are.

-

"The Innovator's Dilemma" by Clayton Christensen - The classic lens for what OPENLANE had to do: protect the core without letting the core prevent the future.

-

"Platform Revolution" by Parker, Van Alstyne & Choudary - Helpful for thinking about two-sided marketplaces, liquidity, and how platforms turn transactions into ecosystems.

-

Cox Automotive Market Reports and Manheim Used Vehicle Value Index - Useful baseline data on pricing, demand cycles, and the competitive backdrop OPENLANE operates inside.

-

Automotive News archive articles on wholesale market evolution - Industry reporting that captures the “why now” moments: consolidation, digital adoption, and the players reshaping remarketing.

-

"Competing in the Age of AI" by Iansiti & Lakhani - A strong framework for how data, automation, and algorithms can become defensibility in operationally messy platforms.

-

Auto Remarketing and Automotive Fleet publications - Ongoing coverage of dealer behavior, fleet dynamics, and the real-world details behind wholesale volume shifts.

-

SEC filings for KAR/OPENLANE, ACV Auctions, and Carvana - The primary documents for deals, risk factors, and the numbers that sit behind the headlines.

-

National Auto Auction Association (NAAA) Industry Surveys - Annual snapshots of the auction market’s scale, mix, and trajectory—especially helpful for grounding the story in industry-level data.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music