Kaiser Aluminum Corporation: From Wartime Giant to Niche Champion

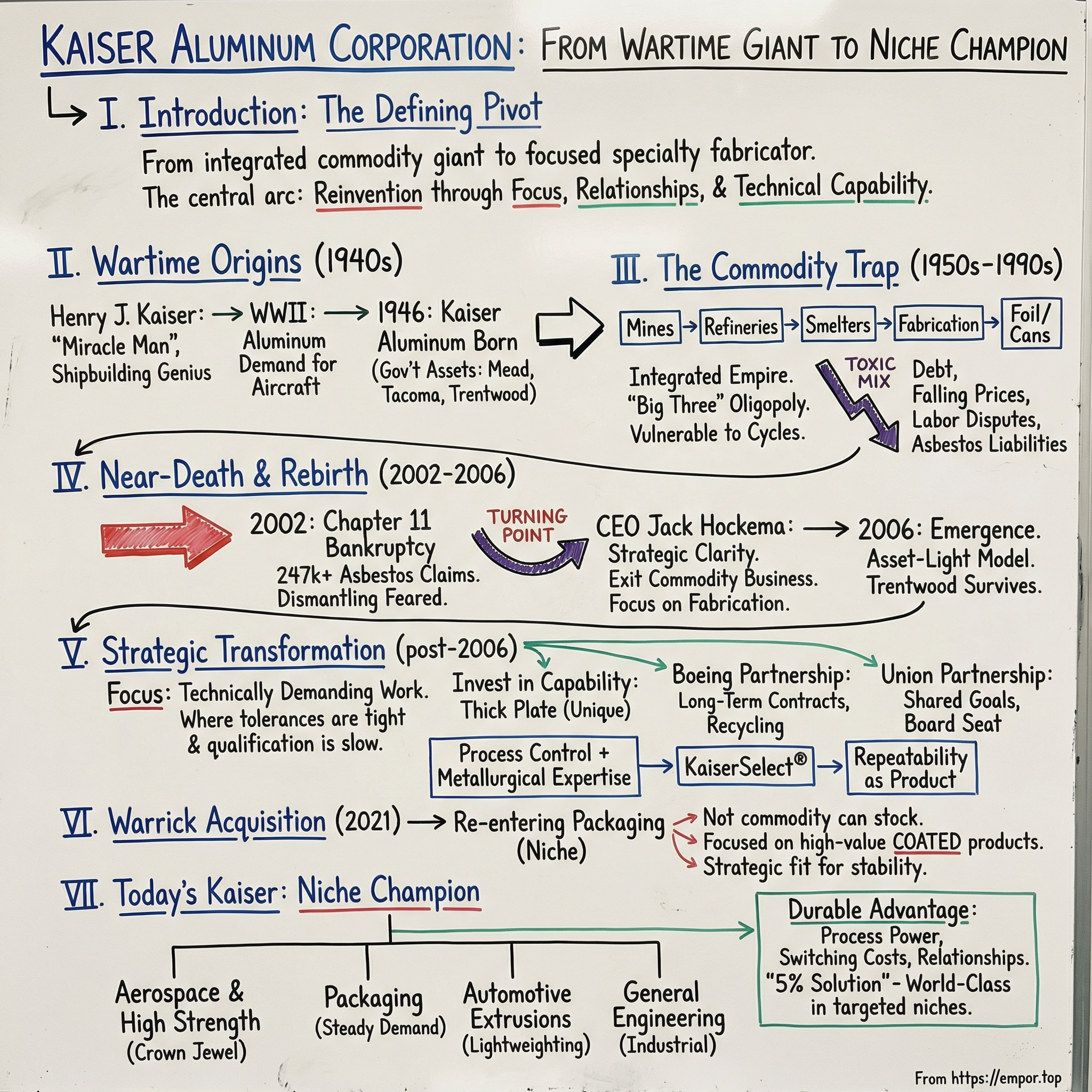

I. Introduction: The Question That Defines This Story

Picture a sprawling aluminum rolling mill in Washington State, sitting on the banks of the Spokane River. It spans sixty-five acres of manufacturing floor space. Inside, furnaces glow as aluminum is heated to roughly 900 degrees. Workers guide massive plates—some up to eight inches thick—through heat-treatment steps that turn raw metal into the structural backbone of Boeing jetliners. This is Trentwood: Kaiser Aluminum’s crown jewel, running continuously since 1942.

But the twist is that Kaiser Aluminum shouldn’t be here at all.

In February 2002, Kaiser filed for bankruptcy. Management pointed to a toxic mix: heavy debt, a weak economy, years of falling aluminum prices, ballooning pension and retiree benefit costs, and the crushing weight of asbestos-related litigation. By then, Kaiser had been hit with roughly 247,000 asbestos lawsuits. Add in legacy obligations, commodity volatility, and a bruising two-year labor dispute, and the outcome seemed inevitable. Many industry watchers assumed Kaiser would be dismantled and sold off piece by piece.

And yet, it survived—and it came out different.

In 2024, Kaiser reported $3.0 billion in net sales, $47 million in net income, and $217 million of adjusted EBITDA, a 14.9% margin. In the third quarter of 2025, it posted net income of $40 million, or $2.38 per diluted share, up from $9 million and $0.54 per share in the re-casted results a year earlier.

So how did one of America’s “Big Three” aluminum producers nearly die, then come back as a high-margin niche player? That pivot—from vertically integrated commodity giant to focused specialty fabricator—is the central arc of this story, and a masterclass in reinvention.

Kaiser’s strategy today is simple to say and hard to do: compete where the work is technically demanding. The company uses metallurgical know-how and process technology to make engineered aluminum mill products for aerospace, packaging, automotive, and industrial customers. It walked away from the brutal commodity game and doubled down on a narrower promise: be exceptional at turning aluminum into high-performance components that only a small handful of companies can reliably produce.

The themes that emerge from this eight-decade journey are timeless: how bankruptcy can create brutal clarity; why focus can beat scale; and how relationships—with customers like Boeing, and with unionized workers who now have a seat on the board—can become real moats in a capital-intensive business.

II. The Kaiser Industrial Empire and Wartime Origins

Before there was Kaiser Aluminum, there was Henry J. Kaiser.

He was a first-generation American born to poor German immigrants, and he spent his early life doing what he’d do for the next half-century: working relentlessly, studying the business in front of him, and climbing into bigger and bigger problems. By the time the twentieth century hit its stride, Kaiser’s fingerprints were already all over American infrastructure.

From 1914 to 1930, he built dams in California, levees along the Mississippi, and highways at scale—famously including two hundred miles of road and five hundred bridges in Cuba. He didn’t just win contracts; he built the supply chain around them, setting up sand and gravel plants so he could feed his own projects. From 1931 through the end of World War II, he helped assemble consortia of construction companies for some of the biggest public works in the country: Hoover, Bonneville, and Grand Coulee among them.

Kaiser had a motto that sounded like a motivational poster, but he lived it: “Problems are only opportunities in work clothes.” If an expert told him something couldn’t be done, he treated it like a dare.

World War II turned that mindset into national fame. Kaiser had no shipbuilding background, but he did have something the incumbents didn’t: a production genius for organizing labor, materials, and workflow. His shipyards pioneered practices that feel obvious today but were radical then—building ships in sections before final assembly, and welding steel plates instead of riveting them.

The output was staggering. During the war, Kaiser’s yards built almost 1,500 ships. In Richmond, California, they became known for speed and for workplace equality, pushing industrial-scale hiring that included women and minorities in roles the industry had historically closed off. His teams drove cargo-ship construction down to an average of about forty-five days. Liberty ships were the headline, later joined by larger, faster Victory ships. And the legend that cemented his reputation: a ship completed in four days.

The press couldn’t get enough. Kaiser was splashed across magazines as the “Miracle Man” and America’s “Number One Industrial Hero.” Roosevelt even considered him as a potential running mate in 1944. In a public poll near the war’s end in spring 1945, Americans named Kaiser the civilian who had done the most to help win the war.

But even while he was building ships, Kaiser was looking at another bottleneck in the war machine: aluminum.

In late 1940, he won a government contract from the Defense Plant Corporation to build aluminum plants on the West Coast—capacity meant to feed aircraft manufacturers. More contracts followed in 1941 through the U.S. Maritime Commission. This wasn’t a random pivot. Kaiser and a colleague, Chad Calhoun, had been bombarding officials in Washington, D.C. with proposals for an aluminum plant in the Pacific Northwest. They understood something critical from their dam-building days: hydroelectric power was abundant there, and aluminum smelting devours electricity. Grand Coulee, in particular, was about to generate the kind of power supply aluminum producers dream about.

Kaiser Aluminum, as the modern company knows it, was born in 1946—by leasing, and later purchasing, aluminum facilities in Washington State from the U.S. government. Those early assets were the reduction plants at Mead and Tacoma, plus a rolling mill at Trentwood.

The timing—and the politics—mattered. The government wasn’t simply selling to the highest bidder. Fresh from an antitrust battle with Alcoa, Washington wanted a durable third competitor alongside Alcoa and Reynolds. In that context, Kaiser benefited from preferential treatment: creating competition in a strategically vital industry mattered more than taking Reynolds’ higher offer.

So on April 1, 1946, Henry Kaiser officially entered the aluminum business. Industry insiders were certain he’d fail. Aluminum demanded specialized skills, advanced process technology, enormous capital, and relentless access to cheap power—none of which sounded like a beginner’s sport. The date didn’t help: critics joked that April Fool’s Day was the perfect time to begin before his “assured failure.”

And yet the facilities were real, and the scale came fast. At its peak, the Mead smelter had sixteen pot line buildings producing ingots, twenty-seven support buildings, and about 2,100 employees. In its first year alone, it produced more than 100 million pounds of aluminum.

What happened next reshaped the industry. That government divestiture helped create an oligopoly where there had effectively been a monopoly. By 1950, a district court decree divided U.S. production capacity among the three: Alcoa with 50.9 percent, Reynolds with 30.9 percent, and Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corporation—Permanente Metals’ new name—with 18.2 percent.

Kaiser’s aluminum ambitions also tied into something else he wanted to build: cars. Along with business partner Joe Frazer, he formed Kaiser-Frazer Corporation for the post-war boom, and the company eventually produced 750,000 cars. During steel shortages, Kaiser floated a visionary idea—build cars with aluminum instead of steel. It was far ahead of its time and never moved beyond experiments, but the instinct was telling: he wasn’t just interested in making metal. He was interested in what the metal could become.

And that’s the founding pattern that matters for everything that comes later. Kaiser Aluminum began as a government-partnered effort to break an industry bottleneck, backed by cheap Northwest power, and oriented from day one toward downstream manufacturing. That DNA—technical capability, value-added products, and relationship-driven selling—would prove essential decades later, when the company had to fight its way back from the brink.

III. The Commodity Trap: Boom, Bust, and Decline

The good times came quickly. When the Korean War spiked demand, Kaiser ramped up production hard—boosting output by roughly 90%. By 1953, Kaiser’s primary aluminum made up more than a quarter of total U.S. production.

The mid-1950s looked like the beginning of a long American manufacturing dynasty. New markets opened up in foil and auto parts. Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Corporation, now widely known as KACC, sat firmly in the “Big Three,” trailing only Alcoa and Reynolds. Aluminum, meanwhile, was becoming the metal of the modern age—second only to steel in the basic metals market.

Henry Kaiser acted like a man building an empire meant to last. In 1955, he broke ground on the Kaiser Center in Oakland, California. From what became the city’s largest new office complex, he oversaw an industrial machine doing about $1 billion in business, employing roughly 41,000 people across 96 plants.

And Kaiser didn’t just grow. It integrated—aggressively.

By the early 1950s, Kaiser had assembled the full aluminum stack: mines in Jamaica, a refinery in Baton Rouge, smelters, and finishing plants spread across regional markets. Some assets came from war-surplus facilities; others were brand-new, large, and expensive. In an era when scale and control were the playbook, Kaiser was building the whole pipeline from ore to finished product.

It even became part of the culture. Disneyland opened with a Kaiser Aluminum Hall of Fame in Tomorrowland. Kaiser tried to turn household foil into a national habit with television, launching The Kaiser Aluminum Hour with Paul Newman and later sponsoring Maverick with James Garner.

On the product side, the company kept innovating: an alloy used for automobile bumpers, a malleable corrugated aluminum roofing material, and a two-piece aluminum can that was an industry first. Kaiser also copyrighted Kalcolor, an electrochemical technique for coloring aluminum during production.

But the same structure that powered Kaiser’s rise also wired in its future fragility. Vertical integration meant huge fixed costs and exposure everywhere—mines, refining, smelting, fabrication. And aluminum is unforgiving. Smelting demands enormous capital and enormous electricity. Prices are set by global commodity markets no one company controls. Demand whipsaws with the economy. When things are good, you look like a genius. When they turn, the business can bleed quickly.

By the 1980s, the world Kaiser had dominated was changing. Global overcapacity emerged as producers in places like Russia and China expanded. Energy costs became volatile. And the integrated model—once a strength—started to look like a trap. Kaiser wasn’t just competing at one layer of the value chain; it was taking hits at every layer.

In 1988, Charles Hurwitz and his company Maxxam, Inc. bought KaiserTech Ltd., the Oakland-based parent of Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Company. Years later, Kaiser would file for bankruptcy in 2002, citing a toxic mix that included labor disputes, the West Coast energy crisis, and asbestos liabilities.

The late 1990s delivered the kind of “perfect storm” that turns a struggling industrial company into a crisis story. Kaiser and the United Steelworkers of America endured a two-year work stoppage that ended on September 18, 2000, after binding arbitration. About 2,900 workers were involved. Five plants were affected—Tacoma, Washington; Gramercy, Louisiana; Newark, Ohio; and two in the Spokane, Washington area. The stoppage led to roughly 1.4 million days of idleness.

It was only the second work stoppage in the parties’ 52-year bargaining history, but it was massive: the longest and largest lockout in the 58-year history of the aluminum industry.

And then, almost immediately, the next blow landed. The West Coast energy crisis of 2000–2001 sent electricity prices skyrocketing—exactly where Kaiser needed cheap, steady power to keep smelters running. The Mead smelter, operating since 1946, was shut down.

Underneath all of it were the liabilities that don’t show up as flashing red lights until it’s too late: pension obligations built up over decades of union employment, retiree healthcare promises, and—most fatally—asbestos claims that had been accumulating since workers began filing lawsuits in the late 1970s.

This is the commodity trap in its purest form. Vertical integration looks elegant in a boardroom, but it multiplies exposure when cycles turn. Commodity pricing can turn “great operations” into “bad economics” overnight. And legacy obligations—pensions, healthcare, environmental cleanup, litigation—can pile up quietly for years before they become existential.

IV. The Bankruptcy and Near-Death Experience

Kaiser’s Chapter 11 filing on February 12, 2002 wasn’t a surprise event. It was the inevitable collision point of several crises that had been building for years. Kaiser and certain affiliates filed voluntary petitions that day. More affiliates followed on March 15, 2002, and the remaining domestic affiliates filed on January 14, 2003. The cases were consolidated for procedural purposes and administered jointly in the United States District Court for the District of Delaware.

The most frightening problem was the one with no natural ceiling: asbestos.

Before filing, Kaiser had already faced more than 120,000 asbestos-related claims. From 1959 to 1978, the company manufactured asbestos products—insulation and refractory materials designed for high-heat industrial and construction settings. Those products worked. They also exposed thousands of people to a mineral that would later become synonymous with slow-moving catastrophe.

Bankruptcy didn’t make the asbestos issue disappear. It forced Kaiser to contain it. When the company emerged, it was required to establish a trust to compensate future victims. The Kaiser Asbestos Trust opened in 2006, funded with $1.2 billion.

Chapter 11 also demanded brutal choices about what Kaiser actually was—and what it was willing to stop being. Over the next few years, the company sold a long list of assets to reduce debt and shed mining and refining holdings, including interests in subsidiaries in Ghana, Jamaica, and Australia. It sold two smelters in Washington state and the Louisiana plant where an explosion had taken place in 1999.

The human impact landed hard, especially in the Inland Northwest where Kaiser had once been a cornerstone employer. In the Spokane area alone, the workforce dropped from about 2,000 to fewer than 600 after the bankruptcy filing. And hanging over everything was labor damage from the years just before Chapter 11, including a prolonged dispute that included what was ultimately ruled an illegal lockout.

Then came the leadership test: who could steer a company through a restructuring that wasn’t just financial, but existential?

That person was Jack Hockema. One month after 9/11, Hockema took over as CEO—somewhat reluctantly, by his own account—after the prior CEO left for a job in another industry. He would serve as President and Chief Executive Officer starting in October 2001, and later became Chairman of the Board in July 2006.

Hockema wasn’t a turnaround celebrity parachuted in from consulting. He was a manufacturing operator with deep aluminum scar tissue. He held a civil engineering degree from Purdue and later earned a master’s in management from Purdue’s Krannert School. In 1975, he became the aluminum industry’s youngest manager of a major facility as works manager at Consolidated Aluminum Corporation in Hannibal, Ohio. He went on to be an award-winning plant manager at Kaiser in the late 1970s, spent the early 1980s as a vice president at Gulf+Western, and later returned to Kaiser as a consultant. By the time he took the top job, he understood the plants, the customers, and the physics of the process.

During bankruptcy, the strategy stopped being abstract and became policy. In 2004, Kaiser moved its headquarters from Houston to Foothill Ranch in Southern California, closer to its fabricated products business. The message was explicit: when Kaiser emerged, fabricated aluminum products would be the core.

This wasn’t simply shrink-to-survive. It was repositioning. Kaiser would get out of the commodity businesses entirely. No bauxite mining. No alumina refining. No primary aluminum smelting. Instead, it would buy metal on market-based contracts and focus on fabrication—the part of the value chain where metallurgical expertise, process control, and long-term customer relationships could actually create durable advantage.

On July 6, 2006, Kaiser emerged from bankruptcy.

Hockema framed it as a beginning, not an ending, saying the company was positioned to benefit from strong demand for aircraft aluminum and a growing market for lighter automobile components. The timing helped: Kaiser came out after more than four years of reorganization into high aluminum prices and a particularly strong aerospace and defense environment. Within months of leaving Chapter 11, the company had landed new long-term contracts to supply aluminum products to the makers of a military jet fighter plane and to Boeing Integrated Defense Systems.

What emerged in 2006 barely resembled the vertically integrated giant that had entered Chapter 11. But the most important asset survived: Trentwood, with its decades of aerospace know-how. And the clarity forced by bankruptcy—focus on the hard, high-value work—would end up being worth more than all the old integration ever was.

V. The Strategic Transformation: Becoming a Different Company

The years immediately after Kaiser emerged from bankruptcy in 2006 forced a fundamental question: who are we now?

What came out of Chapter 11 was not the old Kaiser—the vertically integrated empire that mined bauxite, smelted aluminum, and pushed commodity volume. It was a smaller, more focused company with a handful of surviving plants. Trentwood was one of twelve. And in Spokane Valley, the assignment was clear: if this facility was going to earn its place, it had to become indispensable.

So Trentwood kept its head down and rebuilt.

Over the next several years, the plant went through a $240 million overhaul. It adopted lean manufacturing, hunting for cycle-time reductions, energy savings, and better yield from every pound of metal. Just as importantly, Kaiser took a hard look at what Trentwood should make. Even before bankruptcy, the plant had started stepping away from rolling aluminum for the cutthroat beverage-can market. Coming out of Chapter 11, that shift became doctrine: focus on semi-fabricated plate, sheet, and coil for aerospace and other high-end manufacturing applications.

That single decision—walking away from commodity can stock and doubling down on aerospace plate—captured the new Kaiser philosophy. Don’t try to win on volume in a global knife fight. Win where the work is hard, the tolerances are tight, and the customer pays for certainty.

It also changed Kaiser's sensitivity to the aluminum price cycle. With its smelters shut down years earlier, Kaiser wasn’t trying to survive as a primary-metal producer. It bought aluminum and turned it into specialized, semi-fabricated products. And in aerospace, demand remained strong, with manufacturers sitting on years-long backlogs of aircraft orders.

Trentwood became the physical expression of that strategy. Kaiser kept investing. After a pause during the pandemic, it resumed again—finishing a $25 million expansion at the rolling mill, the latest chapter in a long investment cycle that, by then, had infused roughly $415 million into the Spokane Valley facility over two decades.

That money wasn’t about making more of the same. It was aimed at capabilities that competitors couldn’t easily match. Between 2005 and 2015 alone, Kaiser put $240 million into modernizing the World War II-era factory. The core focus over the past two decades was expanding heat-treatment capability for plate products, and improving the ability to stretch material after heating. Kaiser also made supporting investments in hot-rolling throughput, homogenizing capacity, and casting capacity to feed those additional heat-treat furnaces.

The payoff was a rare industrial capability: Trentwood became one of only three companies worldwide able to produce plate up to eight inches thick—and it can even produce plate ten inches thick. That matters because modern aircraft increasingly rely on large, monolithic aluminum structures: single thick pieces machined down into finished parts, instead of assemblies made from many smaller pieces. Very few producers can make that starting material, and in aerospace, qualification takes so long that switching suppliers is anything but casual.

Which brings us to the relationship that has defined Kaiser’s post-bankruptcy trajectory: Boeing.

Kaiser announced a new long-term contract with Boeing to supply sheet and light-gauge aluminum plate for Boeing commercial aircraft programs. “Kaiser Aluminum and Boeing have a long history of partnership, and this agreement further solidifies the long-term relationship between the two companies,” Jack Hockema said at the time.

Kaiser’s material shows up across major Boeing platforms, including the F-15 Strike Eagle, the F/A-18 Hornet, the C-17 Globemaster III, the CH-47D/F Chinook Helicopter, and the V-22 Osprey.

And it wasn’t just about selling metal. Kaiser and Boeing also built what was described as the largest aluminum recycle program to date, capturing 7XXX and 2XXX alloy recyclables generated at multiple Boeing facilities during commercial aircraft production. “The recycling agreement illustrates our collaborative relationship with Boeing,” Hockema said. The scrap alloys would be re-melted and used in aerospace sheet and plate production at Trentwood.

But the most surprising transformation wasn’t in furnaces or rolling schedules. It was in labor relations.

After the bruising lockout years and the trauma of bankruptcy, Kaiser and the United Steelworkers rebuilt the relationship into something closer to a partnership. By 2018, Dan Wilson, president of Steelworkers Local 338 at Trentwood, described it plainly: “Now, we have a great relationship.” Wilson had lived the old era as a millwright and union officer during the dispute. This wasn’t theoretical progress—it was earned, the hard way.

A new labor agreement extended the Director Designation Agreement, which allowed the union to nominate candidates to the company’s board of directors. “We are pleased to reach this agreement to extend through 2020 our productive, long-term relationship between Kaiser Aluminum and the United Steelworkers,” Hockema said, crediting the Trentwood and Newark workforces as central to the company’s success. Union members now sat on the board.

Out of the labor dispute and bankruptcy, “we forged something different and new,” said Scott Endres, a Kaiser vice president. “Our relationship with the United Steelworkers differentiates us.” Management and labor developed a shared sense of teamwork focused on moving the business forward.

The same mindset showed up in Kaiser’s product strategy. In 2009, the company launched KaiserSelect®, a line positioned around one promise: superior consistency. Kaiser described it as a broad offering of engineered products designed to perform better, generate less waste, and, in many cases, lower customers’ production costs. “Our KaiserSelect® products are highly engineered for your most demanding machining applications and will be our mark in the marketplace,” Hockema said when the line launched.

Under the hood, the goal was repeatability. “The rolling parameters and thermal processing, along with key parameters that control final microstructure and residual stress—things that will cause it to go out of tolerance—were all identified, isolated, controlled and tested,” said Tom Gannon, Kaiser’s vice president of marketing. After years of research and development, Kaiser locked in critical production steps, the metallurgical recipe, and tests that controlled grain structure, stability, and straightness. “Kaiser manages the production process with recipe-controlled PLCs that significantly reduce the variation in the aluminum final product, lot to lot and piece to piece.”

For investors, the lesson is blunt: bankruptcy was the trauma that forced clarity. Kaiser's shift to an asset-light model—buying aluminum instead of smelting it—didn’t just reduce risk; it redirected capital toward higher-return fabrication. And by turning an adversarial labor relationship into a governance-level partnership, Kaiser built an advantage that doesn’t show up on a balance sheet, but is incredibly hard for competitors to copy.

VI. The Alcoa Warrick Acquisition: Re-entering Packaging

For the fifteen years after emerging from bankruptcy, Kaiser stuck to its script: focus on aerospace, automotive, and general engineering. And it stayed away from packaging—the high-volume world of can sheet that it had intentionally walked away from during the transformation. Then, in late 2020, the script changed.

On April 1, 2021, Kaiser completed the all-cash acquisition of Alcoa Warrick LLC from Alcoa Corporation for $670 million. The deal included the assets of the Warrick Rolling Mill. Alcoa kept the related smelting assets, the power plant, and the land. Kaiser, in turn, signed a long-term ground lease with provisions for utility services, plus a transition services agreement and a market-based molten aluminum supply agreement.

“Today we begin a new chapter in our history as we welcome 1,200 Warrick employees to the Kaiser Aluminum family,” said Keith A. Harvey, Kaiser’s President and CEO.

On paper, buying a can-sheet mill looked like Kaiser undoing a hard-won lesson. In reality, the rationale was more layered.

First, it gave Kaiser a direct entry point into North American aluminum packaging—an end market benefiting from sustainability tailwinds and a broader shift away from plastic. Second, the industry structure had improved. Capacity that used to be dedicated to beverage and food can stock had shifted into other end markets, tightening supply and improving the supply-demand balance for packaging.

And Warrick wasn’t just any asset. It’s one of only four dedicated can sheet mills in North America, which meant Kaiser wasn’t simply “getting back into packaging.” It was buying a scarce piece of infrastructure in a market where reliability of supply matters.

The numbers reinforced the point. In the twelve months before the acquisition, Warrick shipped more than 675 million pounds of aluminum, and about 60% of that volume was higher-value coated packaging products.

Kaiser described the fit in plain terms: Warrick complemented its existing, more cyclical businesses and helped smooth the overall portfolio. Aerospace and automotive swing hard with aircraft build rates and vehicle production. Packaging tends to be steadier—people keep buying canned food and beverages through booms and recessions. In Kaiser's view, that meant less volatility and a more durable earnings base.

The broader deal market noticed, too. The 2021 M&A Advisor Awards recognized the transaction as M&A Deal of the Year in the $500 million to $1 billion category.

Then Kaiser did what it always does when it sees a strategic asset: it invested.

Soon after the acquisition, Kaiser announced plans for a new $150 million coating line at Warrick to expand capacity in coated packaging products. The idea was to shift more of the mill’s output toward the coated products used for food and beverage cans, lids, tabs, and ends. The company pointed to packaging demand growth forecasts of roughly 5% to 7% annually over the next five or more years. And it positioned the new line as a meaningful step up—larger, faster, and more capable than the existing lines, blending newer technology with proven legacy systems from the plant’s long operating history.

The key nuance is this: the Warrick deal wasn’t a return to the old commodity trap. Kaiser wasn’t chasing volume for volume’s sake. It was leaning into a part of packaging where process control and technical capability—coated products, consistency, quality—could earn better economics.

In other words, the same post-bankruptcy principle still applied. Kaiser wasn’t trying to be everything in aluminum again. It was adding a business that could diversify the cycle without abandoning the focus on higher-value work.

VII. Today's Kaiser: A Niche Champion in Value-Added Aluminum

Today, Kaiser runs a North American footprint of 13 fabricating plants. Across that network, it has the capacity to produce hundreds of millions of pounds of aluminum each year—value-added sheet, can sheet, plate, extrusions, forgings, rod, bar, and tube. After acquiring the former Alcoa Warrick operation, the company employed about 3,700 people.

The business now sits on four distinct end markets:

Aerospace and High Strength is still the crown jewel. Trentwood remains the heart of that story: one of three mills in the country that manufactures heat-treated, aerospace-grade aluminum, and the only U.S. rolling mill west of the Mississippi. Kaiser supplies plate and sheet that end up in commercial aircraft, military jets, and space applications—work where qualification is slow, specs are unforgiving, and consistency is everything.

Packaging is the newest pillar, and it’s there by design. Trentwood in Spokane Valley, Washington continues to focus on plate and sheet for aerospace and general engineering, while Warrick in Newburgh, Indiana produces coil for beverage and food packaging. The logic is simple: packaging adds a steadier end market to a portfolio that otherwise rises and falls with aerospace build rates and vehicle production.

Automotive Extrusions is Kaiser’s way of riding the lightweighting trend. As automakers push to cut weight for fuel efficiency—and to extend electric vehicle range—Kaiser supplies structural components designed for that shift.

General Engineering is the broad catch-all for industrial demand: everything from semiconductor manufacturing equipment to structural components.

Management’s message coming out of 2024 was that the strategy was working, even in a messy market. “I am pleased with our 2024 performance, particularly our continued margin expansion, which was achieved in a highly complex market environment,” said Keith A. Harvey, Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer. “As we progress into 2025, we expect market conditions to stabilize and become more favorable, enabling us to capitalize on significant growth investments that are nearing completion.”

A big piece of that near-term story is packaging. Kaiser said it was commissioning the new roll coat line at Warrick, with customer qualifications underway. For full-year 2025, the company expected consolidated conversion revenue to increase 5% to 10% and adjusted EBITDA margin to improve by 50 to 100 basis points versus 2024, with roughly 60% of the EBITDA contribution projected to land in the second half of 2025. The outlook assumed demand would stabilize and improve as the year progressed.

That investment cadence is also the point. Kaiser doesn’t do “one big bet and hope.” It does steady, phased reinvestment—the kind of compounding that keeps an old industrial asset relevant in modern aerospace and manufacturing. The new project was described as the seventh phase of expansion since 2005, consistent with that long-running playbook.

Financially, Kaiser also pointed to improving leverage. As of September 30, 2025, the company’s net debt leverage ratio improved to 3.6x, down from 4.3x at December 31, 2024. On October 14, 2025, it amended and extended its $575 million revolving credit facility, pushing maturity out to October 2030.

And the leadership era that carried Kaiser through bankruptcy and reinvention finally closed. In early 2025, Jack A. Hockema retired as Executive Chair after nearly 30 years with the company. Keith A. Harvey, already President and CEO, was appointed Chairman of the Board.

Even the sustainability narrative is now being framed as part of product and process—not a separate corporate appendix. Kaiser’s 2024 sustainability report highlighted a 19% reduction in GHG emissions and the launch of the waste-reducing KaiserSelect Next Gen product line.

VIII. Strategic Playbook and Business Model Analysis

Kaiser’s transformation offers a strategic template that reaches far beyond aluminum. The big idea isn’t complicated: in a brutal commodity industry, don’t try to be decent at everything. Pick the hardest work, narrow the playing field, and become the supplier customers can’t afford to lose.

The Asset-Light Transformation

After bankruptcy, Kaiser made a set of choices that rewired the entire business model. It systematically exited the most capital-intensive, most volatile parts of the aluminum value chain:

- No bauxite mining

- No alumina refining

- No primary aluminum smelting

- Buy molten aluminum on market-based contracts

- Put capital and attention into value-added fabrication

The practical effect is that Kaiser lives and dies on fabrication margins, not on guessing where aluminum prices will go next. When LME prices move, raw material costs move too. But in many contracts, the metal cost largely passes through to customers. What Kaiser is really selling is the conversion premium: the know-how, process control, and consistency required to turn commodity aluminum into something aerospace and industrial customers can actually use.

The 5% Solution

Kaiser’s strategy can be summed up as a “5% solution”: target only a small slice of the global aluminum market, then aim to be world-class inside it.

Instead of battling integrated giants and low-cost foreign producers for commodity share, Kaiser concentrates on applications where:

- Specs are unforgiving

- Metallurgy and process discipline create real differentiation

- Qualification takes time, money, and patience

- Switching suppliers is painful enough that relationships matter as much as price

This is how you turn aluminum—a metal everyone can buy—into a business with something closer to pricing power.

Capital Allocation Discipline

The transformation also shows up in how Kaiser spends money. The pattern is consistent:

- Expand capacity in phases, tied to customer demand (Trentwood is the model)

- Do M&A only when the asset is strategically scarce and the timing is right (Warrick, after years of avoiding packaging)

- Return cash to shareholders without sacrificing the ability to reinvest

In 2024, Kaiser reported adjusted EBITDA of $217 million. That cash supported working capital needs, substantial capital investment, interest payments, and cash returned to shareholders through quarterly dividends.

The Boeing Relationship as Moat

Then there’s Boeing—an example of how “moats” in industrial businesses often look like trust and integration, not logos.

Kaiser has partnered with Boeing since 2012 on a closed-loop recycling process that reverts scrap back into aerospace sheet and plate. But the deeper advantage is the qualification dynamic. In aerospace, getting qualified can take years. And once you’re qualified on a platform, you’re not just a vendor for the next quarter—you’re effectively part of the program for its life, which can stretch for decades.

IX. Competitive Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces and Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW

To compete with Kaiser in aerospace-grade plate, you don’t just need a factory. You need the right factory. An aerospace-capable rolling mill can cost well over $100 million to build, and that’s only the entry fee.

The real barrier is time. Aerospace qualification is slow by design: third-party inspections, trial runs, and sample testing against standards like AMS or ASTM. And then come the OEM gatekeepers. Boeing and Airbus don’t casually add suppliers, because qualifying a new one ripples through the entire program. In practice, getting approved can take three to five years.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Kaiser buys primary aluminum in a market largely priced off the London Metal Exchange, with many global suppliers. And because it doesn’t smelt, it avoids the biggest structural headache in upstream aluminum: the energy-cost roulette wheel that can make a smelter profitable one year and a money pit the next.

There is one notable wrinkle. At Warrick, Kaiser relies on Alcoa for molten aluminum under a market-based agreement. That’s efficient, but it also introduces supplier concentration risk at a strategically important site.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

In aerospace, the customers are giants. Boeing and Airbus have scale, leverage, and procurement muscle.

But they don’t have complete freedom. Switching suppliers is expensive and slow, because it means requalification, re-testing, and reworking supply chain integration. That friction is why long-term contracts matter so much in this industry: they aren’t just revenue visibility for Kaiser, they’re operational stability for the customer.

That dynamic showed up in the latter part of 2021, when Kaiser completed multi-year contracts and extensions with key strategic aerospace and packaging partners, securing additional long-term growth.

4. Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE

Aluminum has real substitutes, but none are clean replacements.

In aerospace, composites have taken meaningful share in certain structures. Aircraft like the 787 and A350 use carbon fiber in the fuselage. Still, aluminum remains critical across many components—wing ribs, structural fittings, and a long list of parts where performance, cost, and manufacturability keep aluminum in the lead.

In automotive, steel competes hard on cost, but lightweighting trends continue to push more aluminum into structural applications. In packaging, the trend runs the other way: sustainability and recyclability have strengthened aluminum’s position relative to plastic.

5. Competitive Rivalry: HIGH in commodity segments, MODERATE in specialties

Where aluminum is a commodity, rivalry is brutal. In the specialty end of the market Kaiser targets, it’s more measured—but still real.

Kaiser’s competitors include Alcoa, Arconic, Constellium, and others. In aerospace fabrication, Constellium and Arconic are direct rivals. The difference is where Kaiser chooses to compete: thick plate capability, specific alloys, and applications where technical execution matters as much as price. That niche focus reduces pure head-to-head price warfare and shifts the battle toward reliability and metallurgical performance.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

Trentwood is one of the largest rolling mills, and scale does help—especially in a capital-intensive process where throughput and yield matter. But this isn’t winner-take-all. Multiple competitors can earn solid returns, and scale alone doesn’t lock the market.

2. Network Effects: NONE

This is industrial manufacturing. No marketplace flywheels here.

3. Counter-Positioning: STRONG (Historical)

Kaiser’s post-2006 pivot was classic counter-positioning. The integrated giants—Alcoa, Alcan—couldn’t easily walk away from mining and smelting without cannibalizing massive legacy investments and organizational identity. Kaiser could.

That advantage has faded somewhat as the industry restructured. Even Alcoa eventually separated its downstream operations into what became Arconic, narrowing the gap between Kaiser’s model and the rest of the field.

4. Switching Costs: HIGH

In aerospace, switching costs are the moat you can’t see from the outside.

Qualification takes years. Alloy specs are customized. Production schedules and just-in-time delivery get tightly integrated. And because failures are unacceptable in flight-critical applications, aerospace and defense customers are structurally risk-averse. Once a supplier is qualified and performing, customers tend to stay put—often for the life of the program.

5. Branding: MODERATE

KaiserSelect® is a real signal in the market: consistency, performance, and cost-efficiency in demanding machining applications. In aerospace and engineering, reputation matters.

But this is still B2B manufacturing. The “brand” is ultimately the product showing up on time, within spec, every time.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Trentwood’s hydropower access, thick plate production capability (only three companies globally), decades of accumulated metallurgical know-how, and long-term customer relationships are all hard to assemble quickly. None are truly irreplaceable in the long run—but they’re difficult to replicate on any reasonable timeline.

7. Process Power: HIGH

This is the heart of Kaiser’s edge.

Over years of R&D, Kaiser identified and locked in the production steps that drive grain structure, stability, and straightness. It manages the process with recipe-controlled PLCs designed to reduce variation—lot to lot, and piece to piece. In markets where customers pay for certainty and rejects are expensive, that repeatability is the product.

Overall Assessment: Kaiser’s competitive power comes primarily from Process Power (metallurgical expertise and operational discipline), Switching Costs (especially in aerospace qualification), and historical Counter-Positioning (its post-bankruptcy break from vertical integration). It’s a strong position—but not an untouchable one. Staying ahead requires continuous investment, relentless execution, and deep customer relationships.

X. Bull vs. Bear Case and Key Investment Considerations

The Bull Case

Secular Aerospace Growth: Commercial aviation has rebounded from pandemic lows, and defense spending has remained resilient. Boeing’s backlog stretches years into the future. If build rates keep rising, Kaiser’s aerospace shipments should rise with them.

Packaging Renaissance: Sustainability pressures keep pushing packaging away from plastic and toward aluminum. For Kaiser, that “aluminum wave” is the reason Warrick matters: it puts the company in the middle of a multi-year tailwind that’s steadier than aerospace.

Niche Dominance: Kaiser’s positioning is built around doing what few others can. Being one of only three companies globally that can produce aerospace plate up to eight inches thick creates real stickiness—customers don’t switch suppliers lightly when qualification is slow and failure is unacceptable.

Operating Leverage: Kaiser has been spending for years to expand capacity and capability at Trentwood and Warrick. As those projects near completion, the upside is classic manufacturing math: once the fixed-cost base is in place, incremental volume can carry meaningfully better economics. Kaiser expected to complete the Phase VII expansion at its Trentwood rolling mill in the second half of 2025, ahead of projected increases in demand.

Capital Returns: Even while investing, Kaiser has kept returning cash to shareholders. On January 14, 2025, the company declared a quarterly cash dividend of $0.77 per share.

ESG Tailwinds: Kaiser has been tying sustainability directly to operations and product. Its 2024 sustainability report cited a 19% reduction in GHG emissions and the launch of the waste-reducing KaiserSelect Next Gen product line. Closed-loop recycling with Boeing and packaging sustainability positioning also align with how many customers now evaluate suppliers.

Valuation: By comparison, Kaiser can look inexpensive. With the U.S. metals and mining industry average P/E at 24.3x, Kaiser Aluminum’s 17.1x P/E appears more conservative—suggesting there may be room for the market to re-rate the stock if earnings momentum holds and profit growth forecasts play out.

The Bear Case

Aerospace Concentration Risk: The flip side of being great at aerospace is that Boeing issues can flow straight into Kaiser’s results. The 737 MAX grounding, production quality problems, and strike disruptions have periodically hit demand and visibility.

Economic Cyclicality: A recession can punish automotive and general engineering volumes quickly. Packaging helps stabilize the portfolio, but it may not fully offset a meaningful downturn in aerospace and auto.

Competition Intensifying: Constellium, Arconic, and Novelis can all compete in aerospace fabrication. If pricing discipline weakens or competitors get aggressive, margins could compress.

Capital Intensity: Kaiser isn’t a smelter anymore, but it’s still a heavy industrial business. Rolling mills require continuous reinvestment just to stay world-class. At Trentwood, the Phase VII project brought total investment in the plant to about $415 million since 2005.

Small Scale: Kaiser doesn’t have the cost structure of the biggest global players in every segment. The strategy works because it stays in the niches where technical capability and execution matter more than sheer scale. Drift outside that lane, and the economics can deteriorate.

Energy Costs: Fabrication is still energy-intensive. Power price spikes can raise operating costs even without exposure to the full smelting energy burden.

Execution Risk: Integration at Warrick, bringing on new coating capacity, and keeping operations stable through expansion all introduce execution risk. In a tight-tolerance business, hiccups are costly.

Key Metrics to Watch

For investors following Kaiser Aluminum, the most important performance indicators are:

1. Conversion Revenue per Pound: This captures what Kaiser really sells: the value it adds by turning commodity aluminum into engineered product. Rising conversion revenue per pound usually signals better mix, better pricing, or both.

2. Aerospace Shipment Volumes: Aerospace is typically the highest-margin segment, so volumes there are a practical read-through on OEM health—especially Boeing and Airbus—and on Kaiser’s standing as a qualified supplier.

3. Adjusted EBITDA Margin on Conversion Revenue: This is the clearest snapshot of operating performance without aluminum price noise. In 2024, adjusted EBITDA as a percentage of conversion revenue was 14.9%, up from 14.3% the year before—evidence of margin expansion in the core conversion business.

XI. Epilogue: What Kaiser Teaches Us

Kaiser Aluminum’s arc—from wartime giant, to commodity trap, to bankruptcy, to focused specialty producer—leaves behind a set of lessons that apply far beyond aluminum.

The Power of Focus: The old Kaiser tried to do everything at once: mine bauxite, refine alumina, smelt primary aluminum, fabricate products, even push consumer goods. The new Kaiser has narrowed the mission: take aluminum and turn it into technically demanding, high-value products where consistency and process discipline matter. Sometimes the best strategy really is doing less, better.

Survival Through Reinvention: Bankruptcy was brutal, but it forced decisions that years of incremental change never would have. Kaiser had to ask the uncomfortable questions: what do we actually do well, and what will customers pay for? The answers pointed away from upstream commodity exposure and toward fabrication—metallurgy, process control, and reliability.

Niche Beats Scale (Sometimes): Kaiser didn’t come back by trying to out-muscle giants like Alcoa. It came back by choosing different battlefields. In the segments Kaiser targets, the edge isn’t lowest cost per pound—it’s the ability to hit unforgiving specs, over and over, and deliver on time.

Know What Business You’re Really In: “We focus on demanding customers and the most demanding products to manufacture. We are up for the challenge. That is what drives our innovation.” Read that again and you can hear the reframing. Kaiser isn’t really selling aluminum. It’s selling metallurgical solutions—an engineered outcome produced through a repeatable, tightly controlled process. That mental shift changes what you invest in, how you prioritize customers, and what you walk away from.

Relationships Are Moats: In heavy industry, moats rarely look like consumer brands. They look like trust built over years: deep integration with customers like Boeing, qualification histories that take forever to replicate, and a labor relationship that evolved all the way to union representatives in the boardroom. Those advantages can’t be bought quickly, and they’re almost impossible to copy on a deadline.

Strategic M&A Discipline: Kaiser didn’t rush back into deal-making after Chapter 11. It spent years rebuilding, investing, and staying in its lane. Then, when Warrick appeared with the right strategic fit, the company moved decisively. The lesson is simple: patience in M&A often outperforms activity.

Manufacturing Still Matters: Trentwood is still there—massive, modernized, and employing more than 900 people producing aluminum for aerospace and other demanding end markets. In an era when it became fashionable to assume advanced manufacturing couldn’t survive in the U.S., Kaiser is proof that it can—if you compete on capability and quality, not labor arbitrage.

So what comes next? Electric vehicle lightweighting continues to open doors. Aerospace remains a long-term growth market, even with near-term turbulence. Packaging has powerful tailwinds. And the expansions at Warrick and Trentwood position Kaiser to capture more of that demand—on its terms.

Henry Kaiser once said problems are opportunities in work clothes. The company that carries his name has lived the line: turning a near-death crisis into strategic renewal. For investors, Kaiser is a case study in reinvention—and a useful filter for spotting which industrial companies can build durable advantages while operating near the edge of commodity economics.

XII. Further Reading and Resources

Top Long-Form Resources:

-

Kaiser Aluminum Annual Reports (2006-present) - The transformation narrative in management's own words, and the clearest way to track how strategy, capital spending, and end-market mix evolved after bankruptcy.

-

"Aluminum by Design" series - A practical primer on aluminum’s properties and why different alloys and forms show up in aerospace, automotive, and packaging.

-

Harvard Business Review: "Competing on Capabilities" - A useful lens for understanding process power, and how operational excellence becomes a defensible advantage in industrial markets.

-

"The Innovator's Dilemma" by Clayton Christensen - Context for counter-positioning, and why big, integrated incumbents often struggle to respond to smaller, more focused competitors.

-

Boeing and Airbus annual reports - Essential context on aerospace build rates, backlogs, and supply chain dynamics that ultimately drive demand for Kaiser’s core products.

-

United Steelworkers case studies on Kaiser - The union perspective on the company’s turnaround, and how labor relations shifted from lockouts to board-level participation.

-

Journal articles on aluminum industry economics - Helpful for understanding the difference between commodity metal economics and the higher-value world of fabrication and conversion margins.

-

"Lean Thinking" by Womack & Jones - The operating philosophy behind many of the lean manufacturing shifts Kaiser adopted as it rebuilt for quality, consistency, and throughput.

-

Trade publications: Light Metal Age, Aluminum International Today - Ongoing industry coverage, technical developments, and competitive moves that shape the aluminum landscape.

-

SEC filings: Kaiser's bankruptcy emergence documents (2006), Warrick acquisition materials (2020-2021), and annual 10-Ks - The details: segment reporting, risk factors, contracts, and the financial mechanics behind the strategy.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music