J&J Snack Foods: The King of the Concession Stand

I. Introduction: The Invisible Empire of "Fun"

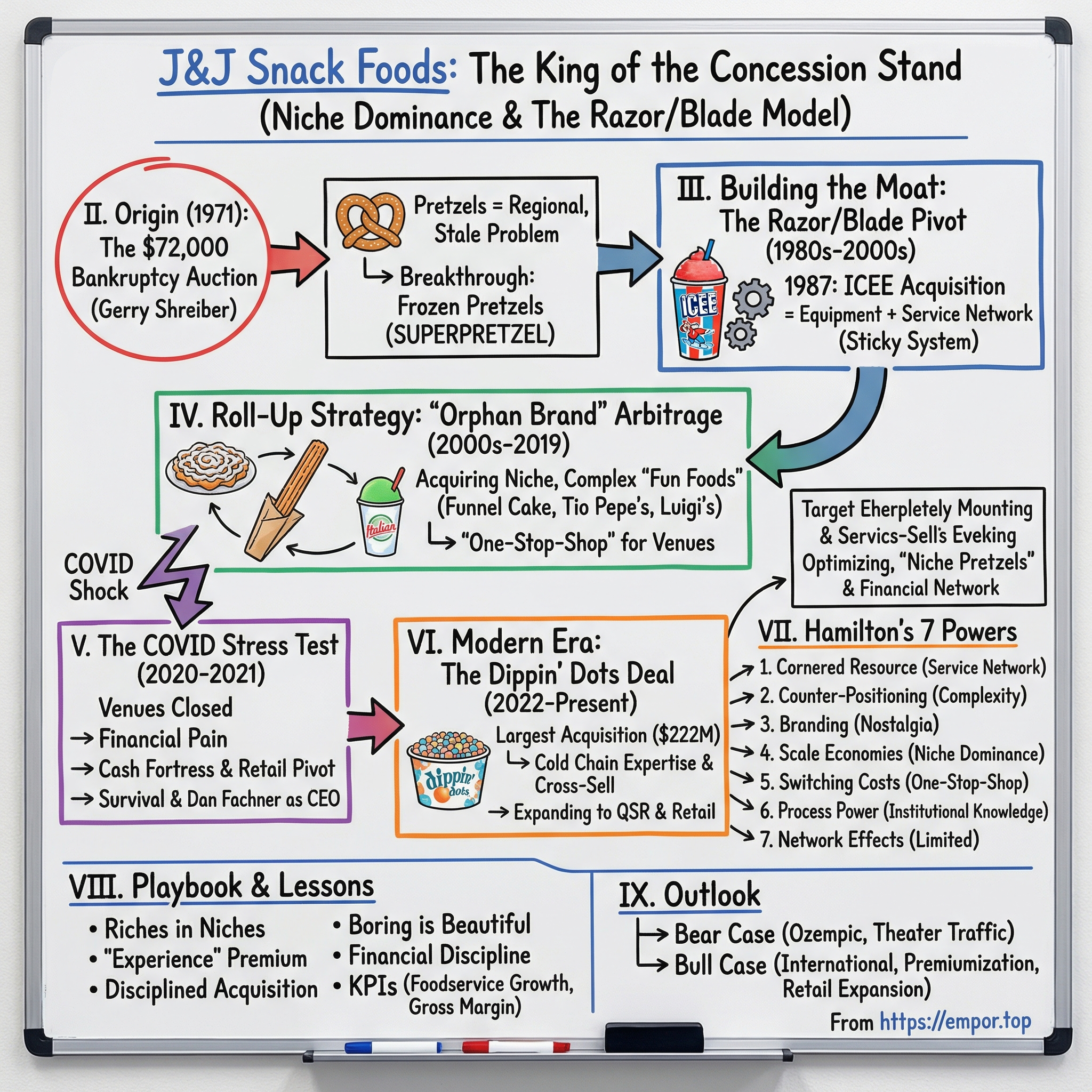

Picture a sweltering July afternoon at a minor league ballpark somewhere in middle America. The home team is down three in the seventh, but the crowd isn’t exactly grieving. A dad hands his daughter a soft pretzel the size of her forearm, its twists glossy with butter and studded with salt. Two rows back, a teenager works on a cherry ICEE, the polar bear logo beading with condensation as it melts down his hand. By the concourse, a couple splits a paper cup of Dippin’ Dots, still amazed that ice cream can come as tiny frozen beads.

The game might be forgettable. The snacks won’t be.

What almost none of those fans realize is that all of it can trace back to the same company. Not Pepsi. Not Nestlé. Not some glossy Manhattan-based food giant. It’s J&J Snack Foods Corporation—headquartered in the decidedly unglamorous Pennsauken, New Jersey—which has quietly built a multi-billion-dollar business by owning the food of American fun.

J&J understands something basic about human behavior: when people are having a good time, they spend differently. Eight dollars for a pretzel at a stadium? Sure. Six dollars for a frozen drink at a theme park? Why not. J&J has engineered itself into those moments—serving everyone from movie theaters, stadiums, and amusement parks to schools, convenience stores, warehouse clubs, and restaurants. If there’s a counter, a crowd, and a reason to celebrate, odds are they’re on the menu.

The thesis here is simple: J&J Snack Foods isn’t just a food company. It’s a masterclass in niche dominance—and, in key parts of the business, a razor-and-blade model. They win by leaning into the operationally messy, low-volume, high-hassle categories that the biggest food companies tend to avoid. Freezers, ovens, sticky machines, service calls, weird logistics—J&J runs toward the complexity, not away from it.

The results are anything but small. In fiscal 2024, revenue rose 1.0% to $1.57 billion, with a gross margin of 30.9% and net earnings of $86.6 million. The company today sits around a $2.5 billion market cap, with enterprise value roughly $2.57 billion. Not bad for what began as a bankrupt pretzel factory with eight employees and under $400,000 in sales.

And the stock story is even stranger—in the best way. After founder Gerald B. Shreiber bought J&J Soft Pretzel in 1971, the business went on to deliver 44 consecutive years of sales growth. No hype cycles. No moonshots. Just steady compounding—the kind of “boring” that tends to make long-term investors very rich.

So how did a scrap metal dealer with zero food experience turn a $72,000 bankruptcy auction purchase into a company that shows up in stadiums, theaters, and amusement parks all over America?

Let’s go back to where it started.

II. The Origin: The $72,000 Bankruptcy Auction

It was 1971. Nixon was in the White House, the Vietnam War was still dragging on, and Gerald “Gerry” Shreiber was 30 years old—working a factory job, raising a young family, and thinking about anything other than becoming a snack-food executive.

Then, in a place you’d never expect, he stumbled into the deal of his life.

Shreiber was shopping in a waterbed store when he got talking with the owner. The owner wasn’t just trying to sell him a bed. He was venting. He’d extended credit to a soft pretzel company, the company had gone under, and now he was staring at a painful lesson in small-business finance.

For Shreiber, it sounded like something else: an opening.

This was a guy with no food background and no business degree. He’d dropped out of Rider College back in 1960, apprenticed in a machine shop, and by 1967 was a partner in a metalworking business run out of a garage. His own motto—“Discover, salvage, and build”—wasn’t a slogan. It was how he looked at the world.

So when he heard “bankrupt pretzel company,” he didn’t hear “lost cause.” He heard “distressed asset.”

He went to see the pretzel operation for himself and quickly decided it was worth a shot. First, he bought the waterbed store owner’s portion for $30,000, plus a share of early profits. Then he went after the rest the hard way: bankruptcy court.

On September 27, 1971, Shreiber walked into the Camden, New Jersey District Court auction and outbid the other parties for the remaining assets. His winning bid: $72,100.

That’s the moment J&J Snack Foods’ story really begins—not with a grand founding vision, but with a bargain purchase and a lot of problems.

What Shreiber bought wasn’t a growth company. It was eight employees, decrepit baking equipment, and a product that didn’t sell particularly well. The business model was shaky. And the product itself had a built-in limitation: soft pretzels didn’t travel.

Back then, the soft pretzel was basically a Philadelphia regional treat. People loved them, but only where they were fresh. Pretzels went stale quickly, which meant you couldn’t ship them far, which meant the market was capped by geography.

Shreiber was betting on the idea that this wasn’t a pretzel problem—it was a logistics problem.

He wasn’t flush with cash, either. The initial capital he put into getting things started was just $8,000, borrowed against his life insurance policy. This wasn’t a side project. It was a full-body bet.

And then came the breakthrough: pre-baked, frozen soft pretzels.

Vendors didn’t want the hassle of baking. Consumers wanted convenience. And freezing solved the one thing keeping the category stuck in one corner of the country: spoilage. Once you could ship and store pretzels frozen, a stadium in California could serve something that tasted like it came from a street cart in Philly.

That insight didn’t just improve the business—it created a category. The frozen soft pretzel.

Shreiber also did what great operators do after they find product-market fit: he put a name on it and pushed it hard. SUPERPRETZEL was born, and it became the cornerstone of the company’s identity.

But as the brand started to spread, Shreiber learned another lesson that would shape the next several decades. The grocery aisle mattered—but the real money was at the venue. The places where people were already primed to spend: stadiums, arenas, theaters, amusement parks. Where the snack isn’t just food; it’s part of the experience.

The expansion was steady. By 1972, he had distributors in Philadelphia and Shrewsbury, New Jersey. Over time, the company’s reach widened dramatically. By 1989, J&J controlled about 70 percent of the soft pretzel market, producing roughly two million pretzels a day, with a marketing network that spanned food brokers and hundreds of independent distributors across all 50 states.

And even though venues were the prize, Shreiber didn’t ignore retail. In 1986, J&J made a real push into supermarkets. When early efforts didn’t meet expectations, he brought in Michael Karaban—the marketer who’d helped make Lender’s frozen bagels a household staple—to sharpen the consumer play. Karaban repackaged the product and shifted the approach to speak directly to shoppers, not just distributors.

The logic was simple: win the freezer aisle, and you build familiarity. Then, when those same customers see Superpretzel at a ballpark, it already feels like the obvious choice.

From a busted pretzel factory with under $400,000 in sales, Shreiber was building a real company—one that, over the next four decades, would grow into a public snack and beverage powerhouse with annual revenue approaching $1 billion.

But the pretzel was only the opening act.

The story was about to accelerate, and it would require Shreiber to rethink what J&J actually was: not just a manufacturer, but a platform for selling “fun,” one concession stand at a time.

III. Building the Moat: The Razor/Blade Pivot (1980s–2000s)

By the mid-1980s, Gerry Shreiber had done the hard part: he’d taken a busted pretzel operation and turned it into the dominant player in a brand-new national category. But he also understood the trap. Even a great single-product business has a ceiling. The soft pretzel market wasn’t infinite, and sooner or later growth would slow.

So he went looking for something that could change the trajectory of the company.

In 1987, J&J Snack Foods acquired ICEE-USA, the maker of the semi-frozen, carbonated ICEE drink—an underdog competitor to 7-Eleven’s Slurpee. At the time, ICEE was losing money in what was described as a $500 million market. Under J&J, it became a very different story: ICEE increased its sales and operating income by more than 20 percent annually through the end of 1991.

That deal was the inflection point—the moment J&J began turning from “a company that sells food” into something closer to a systems business.

Here’s why. When you buy a box of frozen pretzels, you’re buying product. It’s transactional: ship a case, get paid, repeat. Frozen beverages don’t work like that. An ICEE only exists if the machine exists—installed, operating, calibrated, cleaned, stocked, and repaired when it inevitably breaks at the worst possible moment.

That’s the real business. The syrup matters, sure. But the machine is the gatekeeper.

So ICEE brought J&J a classic razor-and-blade model. The “razor” is the equipment: expensive, specialized dispensers that have to be in the store or the theater. The “blade” is what flows through it: the syrup and supplies that get reordered over and over. And if you’re the company that owns the relationship, provides the equipment, and keeps it running, you don’t just win the sale—you embed yourself in the operation.

From then on, the pitch wasn’t “please buy our frozen drink.” It was closer to: want frozen beverages? Great—we’ll bring the whole system. Machines, product, service, the works.

For a movie theater chain, that’s a no-brainer. They can either cobble together equipment, suppliers, and repair support on their own, or they can make one call and have ICEE handle it end-to-end. And once the machines are installed and the staff is trained, switching isn’t just inconvenient—it’s painful. You’re not swapping out a product; you’re rebuilding infrastructure.

J&J doubled down. In July 1991, the company issued a secondary stock offering to help expand ICEE from a 15-state footprint in the western U.S., plus Mexico and Canada, into a national brand.

But the expansion wasn’t just a sales push. It required building what became one of J&J’s most valuable assets: a nationwide service network. Technicians. Parts. Dispatch. The operational muscle to keep machines working wherever they sat. When a slushie machine goes down, the venue doesn’t want an apology—they want it fixed. Fast.

That service capability became the moat. A competitor could make a frozen drink. They could even make a good machine. What they couldn’t easily do is build, staff, and sustain a national field-service operation that shows up reliably—especially across thousands of scattered locations. That kind of network takes years, and the learning curve is brutal.

J&J kept strengthening the platform. The frozen beverage category expanded with the 1992 acquisition of Arctic Blast, and in 1995 J&J acquired the international rights to the ICEE brand—ensuring it controlled the name globally, not just in the U.S.

And then, much later, they finished the job. In 2020, J&J acquired ICEE-USA by purchasing remaining shares in a $2.4 million deal, consolidating complete ownership and simplifying the structure.

The bigger point is what ICEE taught them: equipment plus service creates gravity. The same basic dynamic carries over to other concession categories, too—anything that requires specialized warmers, dispensers, or venue-specific setup. Once your machines are installed, your team knows the routines, and your supplier is also your service provider, “trying someone new” stops being a simple purchasing decision.

It becomes a risk.

And that’s why the ICEE acquisition mattered so much. J&J didn’t just add another product. It added an ecosystem—one that made customers stickier, relationships deeper, and the business far harder to displace.

The pretzels built the company. ICEE built the fortress.

IV. The Roll-Up Strategy: "Orphan Brand" Arbitrage (2000s–2019)

If the ICEE acquisition was J&J Snack Foods’ inflection point, what came next was the slow, disciplined execution of a strategy that doesn’t get much airtime in business schools, but that long-term investors love: buying “orphan brands” and scaling them quietly.

An orphan brand lives in a strange middle zone. It’s too small, too niche, or too operationally annoying for the food giants—Nestlé, PepsiCo, Kraft—to care about. But it’s also too complex for a small regional player to run at national scale. These categories tend to come with quirks: specialized equipment, finicky prep, sticky cleanup, cold-chain headaches, or products that don’t travel well. In other words, exactly the kind of work J&J had learned to embrace.

Take funnel cakes. They’re pure Americana—the smell of hot oil and powdered sugar is basically the scent of a county fair. But as a business, they’re a mess. You’re dealing with fryers, batter handling, trained staff, and a product that’s at its best when it’s seconds old. Big Food wants shelf-stable, repeatable, standardized. Funnel cakes are none of that.

So in 1994, J&J bought The Funnel Cake Factory and moved to own yet another corner of “fun food.” Shreiber summed up the logic to Frozen Food Digest with the kind of plainspoken clarity that shows up again and again in this company’s history: “Funnel Cake represents another niche product for our distribution channels. We like the product. We like the potential.”

Churros followed the same logic—just with a more accidental origin story. Back in 1981, Shreiber was on the hunt for the next growth lever when a supply agreement with Whimsy Stores fell apart. J&J ended up acquiring some of the product inventory, and instead of treating it as a one-off, they used it to build the foundation of a churros business. That eventually became Tio Pepe’s Churros—now sold primarily under the Tio Pepe’s, California Churros, and Oreo brand names.

Frozen novelties were another “orphan” category that fit J&J’s style. The acquisition of MIA Products brought them the frozen novelty manufacturing plant they still use. And by 1989, Luigi’s had been successfully introduced to supermarkets, as company sales reached $86 million. Luigi’s Real Italian Ice became a real portfolio pillar—winning share in frozen cups across both retail and foodservice.

From there, it was a steady drumbeat. The 1990s brought another wave of acquisitions that expanded J&J’s reach while deepening their hold on existing categories. The beverage platform strengthened through Arctic Blast in 1992 and the international rights to the ICEE brand in 1995. Pretzels expanded through deals like Bavarian Soft Pretzels (1994), Pretzel Gourmet and Bakers Best Snack Food (1996), and Texas Twist (1997). Frozen novelties grew with Mazzone Enterprises (1996) and Mama Tish’s International Foods (1997). And baked goods got a boost with Mrs. Goodcookie (1998) and Camden Creek Bakery (1999).

In the 2000s, the same playbook continued. J&J completed the acquisition of ConAgra Foods’ frozen handheld business—dough-enrobed products sold under the PATIO, HAND FULLS, HOLLY RIDGE BAKERY, VILLA TALIANO, TOP PICKS, and private label names—along with manufacturing facilities in Holly Ridge, North Carolina, and Weston, Oregon.

Zoom out and you can see the formula. Find a family-owned or regional brand that’s hit its ceiling. Buy it at a reasonable price. Then plug it into J&J’s national distribution and servicing machine. What the prior owners couldn’t do—break out of their region, win national accounts, show up reliably at thousands of venues—J&J could do with infrastructure they’d already built.

This is how they became the “one call” concession company. If you run a stadium, an arena, a theater circuit, or a theme park, the last thing you want is five different vendors for pretzels, churros, frozen drinks, cookies, and frozen novelties. You want one supplier who can cover the whole stand—and show up when something breaks. Over time, J&J became that supplier.

In total, J&J has completed more than 30 value-building transactions over its history, and it points to “a proven, long-term track record of successfully integrating and scaling niche brands.”

What made the strategy work, though, wasn’t just deal flow. It was how they financed it. Shreiber ran J&J with financial conservatism that’s almost out of fashion: a strong balance sheet, limited reliance on heavy debt, and the patience to wait for the right opportunities. That discipline mattered most when the economy turned. When others were stressed, J&J could act—picking up assets at better prices without having to issue stock at the wrong time or accept punishing borrowing terms.

This steady mix of market penetration and acquisition helped power one of the strangest stats in public food-company history: 44 consecutive years of sales growth.

Years later, CEO Dan Fachner would still describe the same core capability: “a proven, long-term track record of successfully integrating and scaling niche brands including ICEE, SuperPretzel, Luigis and others.”

By the end of the 2010s, J&J had assembled a portfolio that was brutally hard to copy: soft pretzels, frozen beverages, frozen juice treats and desserts, stuffed sandwiches and burritos, churros, fruit pies, funnel cakes, cookies, bakery goods, and more—spread across about 25 brands, anchored by a handful of category-defining names.

It looked like a machine built to run forever.

And then, in early 2020, the venues that made that machine so powerful—stadiums, theaters, theme parks, schools—went dark.

V. The COVID Stress Test: A Near-Death Experience? (2020–2021)

When historians write the business history of COVID-19, J&J Snack Foods will be one of the cleanest examples of what a true demand shock looks like. Not a recession. Not a bad product cycle. A scenario where the places you sell simply stop existing, overnight.

Roughly two-thirds of J&J’s sales went to venues that shut down or sharply curtailed foodservice. And those venues were the heart of the company: movie theaters, stadiums, theme parks, school cafeterias. The exact ecosystem J&J had spent decades stitching together—its “fun” empire—went dark. Concession stands that printed money on a Saturday suddenly had no one to serve.

The financials started telling that story fast. In the fourth quarter of fiscal 2020, sales fell to $252.5 million from $311.9 million a year earlier. For the full year ended September 26, 2020, sales dropped to $1.022 billion from $1.186 billion. And even those numbers blurred the reality, because they still included pre-pandemic months.

The quarter-by-quarter decline was harsher. Net sales for the three months ended June 27, 2020 fell 34% year over year to $214.6 million. In the first four weeks of that third quarter, sales were down about 45% from the prior year—and management warned it could swing to an operating loss for the quarter.

Profitability collapsed with it. Fourth-quarter net earnings fell to $6.6 million (35 cents per diluted share), down from $26.1 million ($1.36). Full-year earnings dropped 81% to $18.3 million (96 cents), from $94.8 million ($5.00).

And the pain hit the crown jewel the hardest. Frozen Beverage—the ICEE machine-and-service flywheel that had changed the economics of the entire company—went from highly profitable to deeply unprofitable. In 2020, the segment posted an operating loss of $12.5 million, versus operating income of $30.0 million in 2019, driven primarily by the sudden collapse in volume.

So why wasn’t this the end of the story?

Two reasons: they had cash, and they could pivot.

Even as J&J acknowledged that COVID-19 would continue to pressure the business, it also made a crucial point: it didn’t expect liquidity issues. The company had $278 million in cash and marketable securities on the balance sheet. In a moment when other businesses were negotiating emergency credit lines or diluting shareholders to survive, J&J had a war chest.

This is where Gerry Shreiber’s decades of financial conservatism stopped looking old-fashioned and started looking brilliant. The fortress balance sheet—easy to critique in good times—became a competitive advantage in the only moments that really matter.

The second reason was operational agility. While foodservice collapsed, grocery demand surged as people ate at home. J&J pushed product into the retail freezer aisle, and the Retail Supermarket segment responded. In the third quarter, soft pretzel sales to retail supermarket customers rose 74% to $12.7 million, and were up 23% for the nine months. Frozen juices and ices increased 26% to $33.3 million in the quarter, and were up 14% for the nine months. Handheld sales to retail supermarket customers rose 6% to $3.3 million in the quarter. Biscuit sales were up 56% to $8.2 million.

Retail wasn’t big enough to fully replace what theaters and stadiums used to generate. But it proved something essential: J&J wasn’t a one-channel company. It had more levers than it seemed.

Then came another major inflection point—one that the pandemic didn’t cause, but certainly accelerated.

On May 11, 2021, J&J announced that Dan Fachner would succeed founder Gerald Shreiber as CEO. Shreiber would remain chairman, but the baton was passed. Fachner wasn’t an outside turnaround artist. He was as inside as it gets: he’d worked for J&J and its beverage subsidiary, The ICEE Company, since 1979. He became senior vice president at ICEE in 1994, president of the unit in 1997, and later rose to president of J&J in May 2020.

In other words, the man who ran the machine-and-service playbook that built J&J’s moat was now running the whole company.

Shreiber put it simply: “Dan's leadership and loyalty has been at the core of the J&J Snack Foods story, and I know he will skillfully serve our organisation and pursue its continued success.”

A founder-to-successor transition is one of the riskiest moments in a company’s life. Plenty of founder-led businesses lose their edge the moment the original builder steps back. But this handoff was designed to be steady: to someone with deep institutional knowledge, operational instincts, and credibility across the organization.

And importantly, the recovery showed up faster than anyone expected.

By fiscal 2021, net sales had climbed back to $1.145 billion, up 12% from $1.022 billion. Fourth-quarter net sales rose to $323 million, up 28% from $253 million, and net income jumped to $18.875 million, or 99 cents per share, up sharply from $6.584 million, or 35 cents.

Fachner highlighted the momentum: “We are pleased with the strong finish to the year and the positive trends we see across our business, including exceeding pre-Covid sales levels in the fourth quarter despite an incredibly challenging operating environment. While fiscal 2019 was one of our strongest years, our net sales for Q4 '21 increased 4%, compared to the same period in fiscal 2019, driven by a 6% increase in our Food Service segment and 29% growth in our Retail segment as traffic across many of our customers' venues and outlets continues to rebound.”

The pandemic stress test proved something fundamental about J&J Snack Foods. The model looked vulnerable because it was so tied to “going out.” But underneath, it had real resilience: multiple channels, a balance sheet built for storms, and the operational muscle to reroute production when the world changed.

They survived the near-death experience. And coming out the other side, Fachner and his team weren’t just trying to get back to normal.

They were setting up the next act—one defined by the biggest acquisition in company history.

VI. The Modern Era: The Dippin' Dots Deal (2022–Present)

In the spring of 2022, Dan Fachner finally got to make the kind of bet that only makes sense if you’ve spent decades living inside concession stands.

For years, he’d watched Dippin’ Dots—the little beads of flash-frozen ice cream—selling right alongside J&J’s own lineup at the same places: outdoor fairs, sporting events, amusement parks. It was the purest form of “venue food,” and Fachner had been pushing for J&J to buy it. In 2022, he got his chance.

J&J announced a definitive agreement to acquire Dippin’ Dots, L.L.C. for $222 million, subject to customary purchase price adjustments. It was funded with a mix of cash and senior debt financing, and it closed on June 21, 2022—the largest acquisition in the company’s history.

“This is a significant day for J&J Snack Foods as we close the largest acquisition in our company's 50-plus-year history,” Fachner said at the closing.

To understand why this mattered, you have to understand what Dippin’ Dots actually is. It isn’t just another ice cream brand. It’s an ice cream industry pioneer built around an innovative, patented cryogenic freezing process that creates “beaded” ice cream, yogurt, sherbet, and flavored ice. It sells through national and local accounts, plus a franchise network of more than 140 franchisees. The company is headquartered in Paducah, Kentucky, with its main production facility, warehousing, distribution, and administrative offices there, and it leases four additional frozen warehouses in California, Canada, Australia, and China.

And then there’s the real kicker: storage.

Dippin’ Dots requires temperatures around -40°F. That’s so cold most food logistics networks simply aren’t built for it. J&J, with its deep experience in frozen distribution, was one of the few buyers that could realistically take this on at scale without turning the cold chain into a margin killer. On logistics alone, the fit was obvious.

But the logic went deeper than temperature-controlled warehouses. As Fachner put it, “Dippin' Dots aligns perfectly with J&J's portfolio strategy by adding an iconic, differentiated brand that uniquely complements our frozen novelty and frozen beverage businesses.” He pointed to the same playbook that built J&J in the first place: leverage strength in entertainment and amusement locations, theaters, convenience, and supermarkets to create go-to-market synergies and new selling opportunities across a larger combined customer base.

J&J expected the deal to be accretive to earnings per diluted share by about $0.30 to $0.40 in the first 12 months after closing, and noted the transaction also came with significant tax benefits that improved the overall valuation.

What really made Dippin’ Dots such a clean “orphan brand” for J&J, though, was where it lived. It’s the ultimate venue snack: most people don’t encounter it in a normal grocery run. They find it when they’re out—at a theme park, a stadium, a mall. That meant little channel conflict with J&J’s retail business, and lots of immediate selling opportunities in places where J&J already had deep relationships.

You could see the cross-sell almost immediately. AMC, which had offered ICEE and SuperPretzel for decades, started selling Dippin’ Dots in 2023.

J&J has continued expanding the breadth and depth of Dippin’ Dots in theaters and has been preparing for a retail launch. With a more compelling film slate expected in fiscal 2025, management has said it’s optimistic about the growth opportunity for both Dippin’ Dots and ICEE beverages as theater traffic rebounds.

And Dippin’ Dots wasn’t the only modern-era expansion. Under Fachner, J&J has also been pushing churros into the quick-service restaurant channel. In fiscal 2024, sales from new products and added placement with new customers totaled about $8.0 million, driven primarily by the addition of churros to the menu of two major QSR customers. The broader takeaway: J&J wasn’t just supplying concession stands anymore. It was starting to compete for snack real estate inside fast food.

Fachner has framed the acquisition strategy with the same blend of appetite and restraint that defined the company for decades. “There probably isn't a week that goes by that I'm not looking at something. I'm looking all the time,” he said. “But we're being very disciplined in the approach that we're taking here.” J&J could afford that discipline. The business was growing, and it didn’t need deals just to paper over stagnation. In 2023, the company posted its third consecutive year of double-digit net sales growth, and profitability was the highest in its history.

The dealmaking didn’t stop with Dippin’ Dots. J&J also acquired the Thinsters cookie brand from Hain Celestial, continuing its pattern of adding niche brands that bigger food companies don’t prioritize.

By fiscal 2024, the financial picture was mixed but still pointed in the direction J&J likes: steady, resilient growth. Net income for the year ended Sept. 28 was $86.551 million, or $4.45 per share, up 10% from $78.906 million, or $4.08 per share, in fiscal 2023. Net sales were $1.575 billion, up 1% from $1.559 billion. Adjusting for an extra (53rd) week in fiscal 2023, sales were up 2.8%.

Fachner called out one highlight in particular: handheld products at retail. Sales in that part of the business rose 58% in fiscal 2024, “led by growth and incremental placements with a major mass merchant.”

Zoom out, and the transformation is easy to miss if you’re only looking for splashy consumer branding. J&J Snack Foods—still largely unknown by name—had become a force across “fun food,” with Dippin’ Dots, SuperPretzel, ¡Hola! Churros, and ICEE in the portfolio. The company’s motto, “Fun served here,” wasn’t marketing fluff; it was an operating principle. Across roughly 30 brands, J&J had built a business that showed up in nearly every retail channel that matters, without ever needing the average consumer to recognize the parent company.

Fachner reflected on the arc: “Gerry used to say it was dusted from ashes. He built what it is today, and last year we did roughly $1.5 billion [in net sales.] It's a good story with a lot of great brands.”

And the story wasn’t over. The same machine that turned pretzels into a national category, and ICEE into a service moat, was now being pointed at a new generation of concession icons—still niche, still messy, still operationally difficult.

Which is exactly where J&J has always been at its best.

VII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

To really understand why J&J Snack Foods has been able to compound for decades, it helps to run the business through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework—seven ways companies build advantages that actually endure.

1. Cornered Resource: The Distribution and Service Network

J&J’s most valuable asset doesn’t show up as a line item on the balance sheet. It’s the nationwide service network behind ICEE and the rest of its equipment-driven categories: the technicians, the parts depots, the dispatching, the know-how.

ICEE is positioned as the leader in frozen beverages, in large part because it doesn’t just sell product. It offers a full package—equipment, service, and supplies—built to work in the real world of theaters, stadiums, convenience stores, and schools.

Picture the situation that matters most: it’s Friday night, a big opening weekend, and an ICEE machine goes down at a movie theater in rural Nebraska. The theater doesn’t need a refund. It needs the machine running again. J&J can send a trained technician—fast. A competitor can make syrup, and a competitor can build a machine. What’s hard to replicate is the national human infrastructure that keeps thousands of machines operating: the trained field team, the inventory of parts, and the systems that route the right person to the right location.

That service model extends beyond beverages. Like its pretzel and churro equipment programs, J&J installs frozen beverage dispensers for ICEE at customer locations and then services the machines. It supplies the ingredients for the beverages and supports retail sales with promotions and point-of-sale materials. It also sells frozen non-carbonated beverages under the Slush Puppie and Parrot Ice brands, through both distributors and its own network. Across the system, J&J provides managed service and/or products to approximately 111,000 company-owned and customer-owned dispensers.

That installed base represents decades of buildup. And each dispenser isn’t just a machine—it’s an embedded relationship and a recurring stream of supply sales that’s extremely difficult to pry loose.

2. Counter-Positioning: Embracing Operational Complexity

J&J built its empire by going after categories that Big Food tends to avoid—not because they’re unattractive to consumers, but because they’re operationally annoying.

Look at what J&J sells and what it takes to serve it:

- Soft pretzels need specific ovens and heating equipment

- Slushies are sticky, machines break, and maintenance is constant

- Churros require fryers and specialized prep

- Funnel cakes need dedicated fryer stations and trained operators

- Dippin’ Dots requires cryogenic storage at -40°F

The food giants want clean, scalable, shelf-stable. They want to ship pallets and collect checks. J&J leans into the opposite: equipment, service calls, prep, training, cold chain—lots of moving parts. It’s also been careful about brand positioning, building distinct identities in “fun” categories rather than stepping into direct fights with companies like PepsiCo.

That’s counter-positioning in action. The exact reasons these categories get ignored—specialized requirements, service needs, lower volumes per location—are the reasons J&J can defend them.

3. Branding: Owning Nostalgia

J&J’s brands aren’t luxury. But they own something that can be just as powerful: memory.

ICEE is movie theaters. Superpretzel is the ballpark. Dippin’ Dots is summer vacations and theme parks. J&J’s portfolio is deep and focused around entertainment away from home, which gives it an advantage over competitors trying to wedge into the same venues. As one analyst put it: “When you're a unique player and you have that kind of established moat, you have that entrenched presence in those certain locations, you own the stadium, you own the movie theaters. It's hard for someone else to come in there and win and take those away from you.”

And it compounds. Every generation of kids builds happy associations with these products, then grows up and brings their own families back into the same ritual.

4. Scale Economies: Niche Dominance

J&J’s scale is unusual: it’s not mass-market scale like soda or chips. It’s scale inside a set of niche categories—pretzels, frozen beverages, churros, frozen novelties—where being the biggest player still matters a lot.

In inputs like flour and sugar, that scale can translate into better economics than smaller regional competitors can match. Distribution matters, too. J&J reaches roughly 85–90% of supermarkets nationwide, and that reach is supported by 41 manufacturing facilities across 11 states—an operating footprint that enables efficiencies others can’t easily replicate.

Scale also changes what innovation costs. If J&J develops something like pretzel bites or churro fries, it can spread the development and marketing costs across thousands of doors. A regional player faces the same fixed work with a much smaller base to pay for it.

5. Switching Costs: The One-Stop-Shop Advantage

For venues, switching isn’t just a price decision—it’s an operational one.

J&J’s setup creates real friction for anyone trying to displace it. The direct-store-delivery model supports freshness, which matters for impulse snacks and perceived quality. And exclusive agreements—like with 7-Eleven—can wall off important channels and raise barriers to entry.

Now put yourself in the shoes of a theater chain that sources pretzels, frozen beverages, and frozen novelties from J&J. If it wants to switch, it’s not swapping a SKU. It’s signing up for pain:

- multiple contracts instead of one

- multiple delivery schedules

- staff training across different equipment systems

- separate maintenance relationships

- separate billing and vendor management

Even if a competitor is slightly cheaper in one category, the hassle tax is real. The “one call” advantage creates inertia.

6. Process Power: Decades of Institutional Knowledge

A lot of what J&J does sounds simple until you try to do it at scale: frozen pretzels that eat well, machines that work in the field, logistics that keep product stable, service operations that respond quickly, and, now, cryogenic cold-chain requirements through Dippin’ Dots.

That kind of capability is built over time, and J&J’s leadership embodies it. Dan Fachner started with the company in 1979 repairing ice cream equipment and delivering flavored syrup while attending trade school in Arizona. He rose through ICEE learning finance, operations, sales, and marketing, eventually becoming president.

That’s not just a resume detail—it’s the company’s advantage in miniature. Fachner learned the business at the ground level, and that accumulated expertise exists across the organization. Competitors can copy products. It’s much harder to copy decades of learned processes.

7. Network Effects: Limited but Present

This isn’t a tech platform, so the network effects are subtle. But there is a demand-side loop: the more venues J&J serves, the more consumers recognize the brands, and the more venues want those brands because they’re familiar and trusted.

It’s part of why theaters added Dippin’ Dots—customers already knew it from theme parks and fairs. Familiarity drives demand, demand drives placement, and placement reinforces familiarity.

For investors, the takeaway from this framework is straightforward: J&J’s advantages are structural. They’re rooted in physical infrastructure, service capability, institutional knowledge, and decades of brand equity. Those aren’t moats a startup can hack, or even moats a well-funded competitor can replicate quickly.

They’re the kind that quietly power long-term compounding.

VIII. The Playbook: Lessons for Builders and Investors

J&J Snack Foods’ run—from a $72,000 bankruptcy auction win to a multi-billion-dollar public company—reads like a playbook for building something durable in plain sight. Not by chasing the biggest markets, but by owning the neglected ones. Not by inventing a new consumer behavior, but by inserting itself into the moments when people are already primed to spend.

Here are the lessons worth stealing.

Riches in Niches

At first glance, snacks look like a knife fight with giants. But J&J showed there’s another way to win: find categories that are too small or too operationally annoying for the conglomerates, then become the default provider.

Frozen soft pretzels. Frozen beverages that require machines and service. Churros and funnel cakes with specialized prep. Cryogenic beaded ice cream that has to live at around -40°F. Each of these is “small” in isolation. Together, they add up to something huge—because once you dominate a niche, you earn the right to stack the next one on top.

By 2024, the company employed roughly 5,000 people and posted record fiscal 2024 sales of $1.57 billion. That growth didn’t come from taking PepsiCo head-on. It came from becoming indispensable in pockets of the market that big competitors didn’t want to bother building for.

The “Experience” Premium

J&J sells snacks when people are happy. That sounds fluffy, but it’s economics.

At a baseball stadium, a movie theater, or a theme park, you’re not “grocery shopping.” You’re buying the experience. And that changes price sensitivity. The pretzel, the ICEE, the novelty dessert—these aren’t line items on a household budget in the same way. They’re part of the ritual.

It’s also why the company’s products travel so well across channels. The same consumer who grabs Superpretzel at home recognizes it at the ballpark. The same kid who begs for Dippin’ Dots at a theme park will notice it in a theater freezer. J&J has positioned itself right at the intersection of fun and food—where demand can be surprisingly resilient compared to everyday staples.

Buy vs. Build: Disciplined Acquisition

J&J’s M&A strategy isn’t about “transformative synergies.” It’s about buying great niche businesses that have hit a ceiling and giving them the scale they never had.

The pattern repeats: find a strong product with a local or regional footprint, acquire it, and plug it into J&J’s distribution and customer relationships. The acquired teams keep doing what they’re good at; J&J provides the infrastructure—national reach, manufacturing depth, and in equipment-heavy categories, service support.

Dan Fachner’s quote captures the posture: “There probably isn't a week that goes by that I'm not looking at something. I'm looking all the time. But we're being very disciplined in the approach that we're taking here.” They can be patient because they don’t need deals to survive. They do deals when they make sense.

Boring is Beautiful

There’s no hype in frozen pretzels. There’s no technological leap that suddenly makes an ICEE machine obsolete. What J&J sells is remarkably consistent: small indulgences tied to entertainment and convenience. And that stability can be a feature, not a bug.

For long-term investors, the appeal is straightforward. While flashier businesses whip around on sentiment, a company that quietly grows through penetration, distribution, and selective acquisitions can compound for decades. J&J’s history of 44 consecutive years of sales growth after Shreiber’s 1971 purchase is the cleanest proof point of what “boring” can do when it’s executed with discipline.

The Power of Financial Discipline

J&J’s balance sheet conservatism paid off when it mattered most. During COVID-19, that caution stopped looking like dead weight and started looking like survival gear. The company’s cash position helped it weather the shock without getting forced into ugly financing decisions.

That mindset has continued under Fachner. As of Q2 2025, the company reported over $48 million in cash and no long-term debt—flexibility that keeps acquisition optionality high and risk low. J&J’s edge has never been financial engineering. It’s been the ability to keep playing offense while others are forced into defense.

The KPIs That Matter

If you want to track whether the machine is working, two metrics tell you most of what you need to know:

1. Foodservice Segment Revenue Growth: J&J still lives and dies by venue traffic—movie theaters, stadiums, theme parks, and other out-of-home locations. When foodservice is growing, it usually means demand is healthy, placements are expanding, and the core “fun” engine is firing.

2. Gross Margin Trajectory: Margins reveal whether the complexity is being managed well—pricing, efficiency, and mix. J&J has targeted improving gross margins to over 31% in the near term and into the mid-30% range over the medium term. Progress here signals operational execution, especially in a business exposed to commodity inputs like flour, sugar, oils, and the realities of running a large manufacturing footprint.

Together, those two KPIs capture the essence of J&J: how much volume the venues are generating—and how well the company converts that volume into profit.

IX. Conclusion and Forward Outlook

As J&J Snack Foods moved deeper into its sixth decade, it faced the same question that every great niche compounder eventually runs into: how do you keep growing without breaking the very advantages that made you special?

J&J’s edge has never been about being trendy. It’s been about being embedded—inside venues, inside operations, and, in the case of ICEE, inside literal equipment sitting on the floor. The future, then, comes down to whether those venues keep humming, and whether consumer behavior keeps favoring the kinds of small indulgences J&J sells.

The Bear Case

There are real risks here—some slow-moving, some immediate.

First is the “Ozempic effect.” GLP-1 weight-loss drugs could reduce overall snacking and impulse purchases over time. If a meaningful share of consumers eats less—or thinks differently about treats—then fewer people might say yes to the extra ICEE or the churro on the way back to their seats. J&J gets some protection from the fact that its products skew toward special occasions, not everyday eating. But if American snacking behavior shifts structurally, J&J won’t be immune.

Second is movie theater traffic, which matters a lot. Softness in the theater channel impacted volumes in Q2 2025, and that’s not a surprise—post-pandemic exhibition has faced fewer releases and changing viewing habits. Management expects improvement as film slates strengthen, but if moviegoing continues to decline over the long haul, it would hit J&J where it’s most concentrated: frozen beverages and, increasingly, Dippin’ Dots.

Third is the direction of health consciousness and potential regulation. J&J’s core hits—sugary frozen drinks, carb-heavy pretzels, deep-fried churros—aren’t exactly aligned with “better-for-you.” The venue setting helps; people don’t go to the ballpark to count macros. Still, changes like taxes or labeling requirements on sugary products could create real headwinds.

And then there’s input cost inflation, the unglamorous grind that always matters in food. The company cited net mid-single-digit inflation across raw materials, driven primarily by higher cocoa and chocolate costs, with additional pressure from sugar and sweeteners, eggs, and meats. Passing those costs through is possible, but it’s never guaranteed—and venues have their own limits on how far they can push pricing before customers start grumbling.

The Bull Case

The upside case is just as clear—and it plays to everything J&J has always been good at.

International expansion remains a wide-open runway. Most of the business is still U.S.-centric, with a limited presence in Canada, Mexico, and select international markets. If you believe the “fun food” concession model travels—and there’s no reason it shouldn’t—then ICEE and SuperPretzel could scale into entertainment venues globally.

Premiumization is another tailwind, and J&J is already leaning into it. Stuffed churros, gourmet pretzel varieties, and cross-branded ideas like ICEE-flavored Dippin’ Dots push the mix toward higher-margin products. The company has also seen success with some of the largest national QSR chains, and management expects its recent churros launch in that channel to open up more opportunities. That’s important: it’s not just new products, it’s new places to sell them.

Then there’s the acquisition flywheel. J&J operates in a fragmented universe filled with founder-owned brands that can’t—or don’t want to—build national distribution, service, and logistics. With more than 30 acquisitions behind it and a strong balance sheet, J&J remains positioned to keep consolidating the “orphan brand” universe as owners look for exits.

Finally, retail expansion—especially for Dippin’ Dots—still looks like early innings. Dippin’ Dots is in just over 2% of the retail locations where it could plausibly be carried. If the company executes on broader grocery and convenience placements, that’s meaningful headroom without needing to invent a new product.

Porter’s Five Forces Assessment

Threat of New Entrants: Low. J&J’s mix of an installed equipment base, a nationwide service network, long-standing venue relationships, and recognizable brands isn’t something a startup can will into existence. Replicating that infrastructure would take massive investment and years of execution.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate. Inputs like flour, sugar, and oils are commodities sourced from multiple suppliers. Costs can swing, but no single supplier controls the relationship.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Moderate to Low. Large customers can negotiate, but J&J’s one-stop-shop setup—and the switching costs tied to equipment, service, and operations—creates real stickiness.

Threat of Substitutes: Moderate. A customer can always buy a different snack or a different drink. But in venues, brands like ICEE are often the expected choice, and the purchase is part of the outing. That “experience” component makes substitution less purely price-driven.

Competitive Rivalry: Low to Moderate. There are regional players in pretzels, churros, and frozen novelties, but few can compete nationally across multiple categories. Big Food could enter, but historically hasn’t—because these are operationally complex businesses that require service, equipment, and a willingness to deal with mess.

Final Reflection

J&J Snack Foods is, at its core, a very American kind of business story. Gerald Shreiber—a college dropout with a machine-shop background—borrowed against his life insurance policy, showed up at a bankruptcy auction, and built an empire one concession category at a time. Pretzels first. Then ICEE machines and the service network that made them sticky. Then decades of disciplined acquisitions that turned J&J into the “one call” supplier for fun.

Nothing about it is glamorous. The products aren’t revolutionary. The company doesn’t need you to know its name.

And yet for more than fifty years, it has done something that’s rare in any industry: it has compounded steadily by owning the unsexy work—distribution, service, logistics, and a portfolio of snacks that show up when people are happiest.

As Fachner put it: “Gerry used to say it was dusted from ashes. He built what it is today, and last year we did roughly $1.5 billion [in net sales.] It's a good story with a lot of great brands.”

The reminder here is simple. Sometimes the best businesses aren’t built on the next breakthrough. They’re built on rituals that don’t change: a warm pretzel, a cold drink, and a moment of fun.

X. Sources and Further Reading

If you want to go deeper—into niche investing, enduring competitive advantage, and the world J&J built its empire inside—here are a few high-quality starting points.

Books:

- 7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy by Hamilton Helmer — The competitive-advantage framework used throughout this analysis

- The Outsiders by William Thorndike — Case studies of CEOs who compounded value through discipline and capital allocation, in a way that echoes Shreiber’s style

- Fast Food Nation by Eric Schlosser — Useful background on the modern American foodservice machine that makes companies like J&J possible

Company Resources:

- J&J Snack Foods annual reports and 10-K filings (SEC EDGAR)

- Earnings call transcripts (via the company’s investor relations site)

- Company historical timeline at jjsnack.com

Industry Analysis:

- International Food Information Council surveys on consumer snacking behavior

- Circana (formerly IRI) data on food and foodservice trends

- Trade publications: Food Business News, QSR Magazine, Food Dive

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music