Janus Henderson Group: The Merger That Tried to Outrun an Industry in Decline

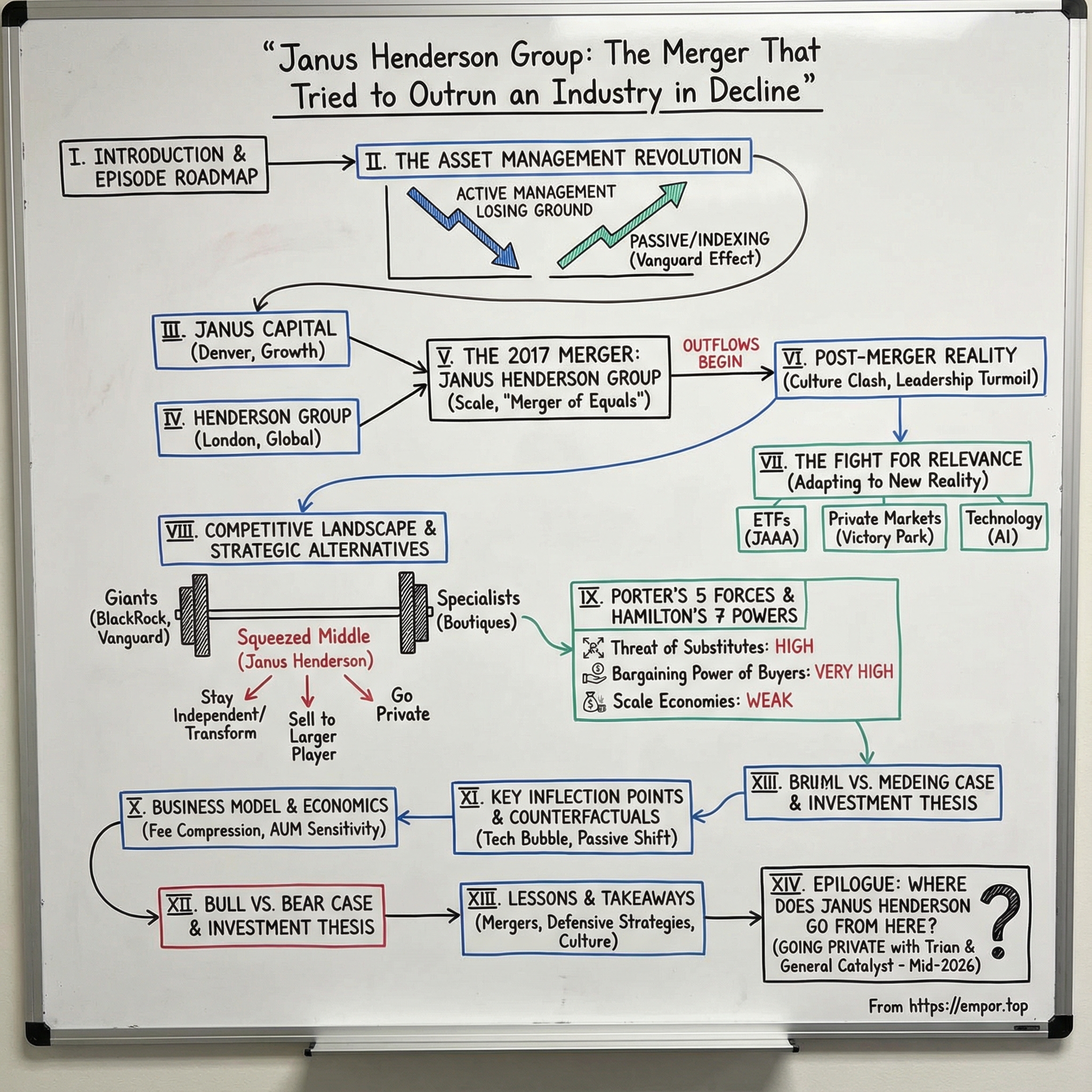

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture two proud money managers standing at the altar in May 2017—one in Denver cowboy boots, the other in bespoke British tailoring from the City of London. Janus Capital Group and Henderson Group were about to become Janus Henderson, a global asset manager with about $331 billion under management, born from what both sides insisted was a “merger of equals.” The wedding photos showed smiling executives. The marriage, as it turned out, would be stress-tested almost immediately.

The deal was an all-stock combination that closed in May 2017. Fast-forward to the end of this story arc: in December 2025, Janus Henderson signed a definitive agreement to be acquired by Trian Fund Management and General Catalyst in an all-cash transaction, valuing the equity at roughly $7.4 billion. The investor group also included strategic backers like Qatar Investment Authority and Sun Hung Kai & Co. Limited, among others. From “merger of equals” to going private in under a decade—something clearly didn’t go to plan.

That brings us to the central question animating everything you’re about to hear: Can you merge your way out of a secular industry crisis?

Because active management—the business of paying humans to pick stocks and bonds in hopes of beating the market—has been losing ground to low-cost index funds for nearly two decades. This isn’t a bad quarter or a rough cycle. It’s a structural shift: investors have moved trillions from active strategies to passive, benchmark-tracking funds.

And that’s what makes Janus Henderson such a useful case study. Janus was once the hottest fund family in America—by 2000, no one was pulling in more money, at one point gathering as much as $1 billion a day. Henderson, meanwhile, carried the weight of British institutional finance, with roots reaching back roughly ninety years. On paper, their combination had logic: complementary geographies, broader products, more scale. In practice, it mostly bought time.

So in this episode, we’ll start with the revolution that rewired asset management—how indexing went from heresy to default. Then we’ll trace the two firms that walked into this merger: Janus, the growth-stock gunslinger that flew too close to the dot-com sun, and Henderson, the British institution that tried to globalize before the ground shifted under everyone. Finally, we’ll follow what happened after the vows: the integration, the outflows, the pivots, and why the story ends—at least for now—with a take-private deal.

For investors looking at active managers, for operators contemplating defensive consolidation, and for founders trying to build something that can survive disruption, Janus Henderson offers a surprisingly sharp set of lessons. Let’s dig in.

II. The Asset Management Revolution: Setting the Stage

To understand why Janus Henderson existed at all—and why it ultimately agreed to go private—you have to rewind to the golden age of active management. From the 1980s through the late 1990s, stock-picking wasn’t just popular. It was the default. Mutual fund managers landed on magazine covers. Peter Lynch turned Fidelity into dinner-table conversation. The shared assumption was simple: markets were inefficient, and the right professionals could beat them, year after year.

And investors paid up for the privilege. Expense ratios around 1% to 1.5% were common, and loads and sales charges could tack on even more. In exchange, you got the promise of alpha—and in that era, alpha felt abundant. “Index fund” was practically an insult: a product for people who weren’t even going to try.

Then, quietly, a different idea showed up and refused to go away.

In 1975, John Bogle founded The Vanguard Group and popularized a radical proposition: don’t try to outsmart the market—own it. Passive investing, first through index funds and later through ETFs, was a structural innovation. It stripped away trading, manager selection, and mystique, and replaced it with something far more compelling to regular investors: broad market exposure at rock-bottom cost.

Bogle’s argument was devastatingly straightforward. Once you subtract fees, most active managers don’t beat their benchmarks. And the few who do rarely keep doing it. So instead of paying for a moving target—finding tomorrow’s winners—investors should lock in market returns as cheaply as possible.

For a long time, that was still a minority view. Active managers had brands, distribution, and decades of inertia on their side.

The 2008 financial crisis snapped that inertia. Lehman collapsed. Housing imploded. Equities cratered. And suddenly, the value proposition of “expert” money management didn’t feel like a luxury—it felt like a question. If the professionals didn’t see a once-in-a-generation drawdown coming, why were investors paying premium fees?

The crisis didn’t create the data that showed active management’s struggles. It made people finally care about it.

From there, the flow of money started to look less like a cycle and more like gravity. Active mutual funds—already under scrutiny for lagging benchmarks—saw net outflows accelerate, including more than $1.8 trillion leaving between 2022 and 2023.

Meanwhile, passive just kept taking share. Statista estimates passively managed index funds were about 19% of U.S. investment-company assets in 2010. By 2023, they were roughly 48%. And in 2024, passive overtook active in total U.S. assets for the first time.

Even within the most mainstream category—large-blend U.S. equities—the contrast was brutal. Passive large-blend strategies pulled in hundreds of billions in 2024, while active large-blend strategies saw huge amounts head out the door. This wasn’t one bad year. It was a multi-decade trend getting stronger with every market cycle.

Then came the squeeze that made the whole thing self-reinforcing: fee compression. As money flowed to cheap index products, active managers had to cut their own fees to compete. But cutting fees while also losing assets is a dangerous combo. It can trigger the classic AUM death spiral: less revenue leads to fewer resources for research and talent, which can lead to weaker performance, which drives more outflows. And by 2024, the symbolism became reality: passive mutual funds and ETFs in the U.S. held more total assets than active.

By 2015 and 2016, the menu of real options for a mid-sized active manager was shrinking fast. You could sell to a bigger platform and become a boutique inside someone else’s empire. You could slash costs and “harvest” the business as assets declined. Or you could merge with someone complementary, chase scale, and hope efficiencies bought you enough time—maybe long enough for active to feel essential again.

Janus and Henderson chose that third door. To see why, we need to look at what each firm brought to the altar.

III. Janus Capital: The Growth Stock Gunslinger

Janus Capital began in 1969 with a simple, stubborn idea from Tom Bailey: you could build a world-class money manager far from Wall Street—and maybe do better because of it. He set up shop in Denver, launched the Janus Fund, and named the firm after Janus, the Roman god of doors and beginnings. It was a fitting choice for a company explicitly trying to walk through a different door than the rest of the industry.

Denver wasn’t a quirky detail. It was the point. Bailey wanted distance from the herd, from the conventions and politics of New York, and the freedom to invest with more independence and urgency. From day one, the firm leaned into bottom-up, research-heavy stock picking—judging companies on their merits rather than trying to time the market’s mood.

He also built Janus around people. Bailey gave portfolio managers real autonomy, demanded deep fundamental work, and encouraged a contrarian streak that made the place feel more entrepreneurial than institutional. His edge, more than any single trade, was talent identification—finding and developing managers in what became “the Janus way.” Over time, he fostered a bench that included names like Jim Craig, Helen Young Hayes, Tom Marsico, Ron Sachs, Scott Schoelzel, Blaine Rollins, Claire Young, and Sandy Rufenacht.

In 1984, Kansas City Southern Industries bought a controlling interest. The deal brought growth capital without stripping away the investment independence that was core to Janus’s identity. Through the 1980s, the firm expanded and earned respect—but it was still more standout regional shop than national phenomenon.

Then the 1990s arrived, and everything about that positioning suddenly looked genius.

As the technology boom gathered speed, Janus’s growth-stock DNA became rocket fuel. The firm’s flagship funds posted eye-popping gains at exactly the moment investors were looking for boldness and momentum. The Janus Fund surged in 1998 and 1999, and Janus Twenty—more concentrated, more aggressive—did even better. Over the decade, Janus Twenty delivered extraordinary results, and Janus portfolio managers turned into stars: magazine profiles, TV interviews, and the kind of attention usually reserved for CEOs and celebrity analysts.

Denver became part of the mystique. Alongside local rival Bill Berger, Bailey helped put the city on the map as a growth-investing capital, a place corporate executives now had to visit if they wanted to win influential shareholders.

The money followed. Janus’s assets exploded—from tens of billions in the mid-1990s to roughly $330 billion at the market’s peak in early 2000.

And then the music stopped.

When the tech bubble burst, Janus’s concentrated exposure to technology and telecommunications didn’t just hurt—it defined the firm’s collapse. The flagship funds cratered during the 2000–2002 bear market, and the Global Technology Fund was hit especially hard. Janus had been a big owner of the era’s emblematic winners—names like Amazon, AOL Time Warner, and Cisco—and when the bubble deflated, the firm’s performance fell with it.

Investors didn’t wait around. Redemptions piled up, and Janus went from the symbol of go-go investing to a cautionary tale in just a few years.

As if the performance damage weren’t enough, the early-2000s mutual-fund scandal poured salt in the wound. In 2003, New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer’s investigation into fund trading practices expanded beyond the initial late-trading allegations, and Janus was accused—along with other firms—of allowing market timing activity. In 2004, Janus paid $226 million to settle charges that it violated state and federal securities laws. The episode reinforced the worst possible narrative: not only had investors lost money, but the game may not have been played fairly.

Bailey stepped down as president and CEO in 2002, and Janus entered a long rebuild. It tried to broaden beyond its growth-equity identity by acquiring value-oriented Perkins Investment Management in 2003 and adding mathematical equity capabilities through INTECH. It also pursued big-name credibility, including recruiting Bill Gross from Pimco in 2014 to run a global unconstrained bond strategy.

But by 2015 and 2016, the vulnerability was still there. Janus was sizable, but not big enough to enjoy true scale advantages. Its lineup was still tilted toward equities just as clients were increasingly gravitating to fixed income and multi-asset solutions. The brand carried baggage from the dot-com wreckage and the trading scandal. And its distribution was heavily U.S.-centric at a moment when global reach was becoming table stakes.

Janus needed a reset—something structural, not incremental. And across the Atlantic, Henderson was arriving at a similar conclusion for its own reasons.

IV. Henderson: The British Institution Goes Global

If Janus was born in the wide-open American West, Henderson came into the world wearing a London waistcoat.

The firm’s origin story starts in 1934, when it was created to administer the estate of Alexander Henderson, 1st Baron Faringdon. That inheritance mandate might sound narrow, but it anchored Henderson in the City of London’s most important asset: trust. Over time, the work expanded from estate administration into professional portfolio management, particularly through investment trusts, a core British vehicle for pooling capital.

By 1975, Henderson had moved into managing pension funds—another step deeper into the institutional bloodstream of the UK. And in 1983, it became a public company, listing on the London Stock Exchange.

Then came the turning point that pushed Henderson from “British institution” to something more global: Australia.

In March 1998, AMP Limited acquired the business and integrated it with AMP Asset Management’s operations in the UK and Australasia, under the Henderson Global Investors name. The AMP years gave Henderson more scale and reach, but they also brought the kind of complexity that tends to show up when a financial conglomerate tries to make everything fit neatly on one org chart.

In 2003, Henderson re-emerged as an independent public company again, demerging from AMP and re-listing in London as HHG Group. The post-demerger structure included Henderson Global Investors alongside other businesses like Life Services and the financial advisory firm Towry Law—evidence that the separation wasn’t a simple “back to basics” so much as a reshuffling into a new, standalone platform.

Independence set off a familiar asset-management playbook: buy capabilities, buy distribution, buy scale.

Through and after the global financial crisis era, Henderson expanded with acquisitions, including New Star in 2009 and Gartmore in 2011. The deals strengthened its UK retail franchise and broadened its product set—especially in equity income—and they brought real distribution relationships that were hard to build from scratch.

By the mid-2010s, Henderson oversaw around £100 billion in assets and looked, in some ways, sturdier than Janus. Its footprint was meaningfully international—strong in the UK and Europe, with presence in Australia and Asia—and its product mix was less concentrated in U.S. growth equities, with more fixed income and multi-asset strategies in the toolkit.

Andrew Formica, who became CEO in 2008, led Henderson through the financial crisis and those acquisition years. Under him, Henderson tried to position itself as a global active manager: European strengths, Asian ambitions, and enough breadth to look credible in a world where large allocators increasingly wanted fewer managers doing more things.

But even with a broader footprint, Henderson couldn’t escape the same gravity pulling at the whole industry. Passive kept eating share. Fees kept compressing. Performance became harder to sustain, and operational efficiency became harder to improve without cutting into the very people and processes clients were paying for.

Which is why, when Henderson looked across the Atlantic, the attraction of Janus was obvious. Henderson had international distribution and more diversified capabilities. Janus had U.S. reach, deep equity-investing DNA, and a brand that still resonated with American retail investors. Put them together and you could cut overlapping costs, consolidate functions, and pitch clients a single global platform across regions and asset classes.

On paper, the math worked.

Whether the people would? That was the part no spreadsheet could solve.

V. The 2017 Merger: Desperation or Vision?

After months of courtship, Janus shareholders made it official. They approved the agreement and plan of merger with Henderson Group dated October 3, 2016, with about 86.2% of shares voting in favor.

The announcement itself read like a greatest-hits album of deal language: “strategic rationale,” “compelling value creation,” “significant scale,” “diverse products,” “depth and breadth in global distribution.” Both boards unanimously backed an all-stock “merger of equals,” promising a leading global active manager that could deliver world-class client service, gain market share, and enhance shareholder value.

On May 30, 2017, the transaction closed. Henderson delisted from the London Stock Exchange, and the combined company—Janus Henderson Group plc—listed on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker JHG.

The logic on paper was clean. Janus and Henderson really were complementary in the ways bankers love: different customer bases, different product lineups, and different geographic footprints. In the pitch deck version of reality, Henderson’s international distribution could help sell Janus products abroad, while Janus’s U.S. reach could pull Henderson strategies into American channels. Add it up, and you got a larger platform that could meet more client needs and, ideally, generate stronger profits.

The deal terms showed how carefully “equals” had been negotiated. Ownership was split roughly 50/50. The headquarters would effectively be dual—London and Denver. Leadership would be shared too, at least at first, with Dick Weil from Janus and Andrew Formica from Henderson serving as co-CEOs. Governance reflected the same balance: the initial board would have 12 directors, six designated by Henderson, including Formica and Henderson’s then-chairman Richard D. Gillingwater, who would become chairman of the Janus Henderson board.

Cost synergies were the hard-dollar heart of the thesis. Management projected $110 million in annual run-rate savings within three years, mainly by cutting duplicated corporate functions, rationalizing technology platforms, and consolidating office space. Those numbers were believable—asset-management mergers tend to hit cost targets precisely because the overlap is obvious and the cuts are, however painful, straightforward.

Revenue synergies were the softer promise. The story was that cross-selling would follow: distribution teams would push each other’s funds, global clients would consolidate mandates, and research capabilities would add up to something greater than the sum of the parts. But clients don’t hire asset managers because two companies combined their back offices. They hire them for performance, fees, and service. A Henderson salesperson pitching a Janus growth fund still had to answer the only question that mattered: why this fund, now, versus everything else?

The market, unsurprisingly, didn’t throw a parade. Commentary ranged from polite optimism to open cynicism, and “rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic” showed up more than once. The critique wasn’t that the merger couldn’t cut costs. It was that combining two firms living under the same industry pressure didn’t magically create a growth engine—it created a bigger company with the same problem and a temporary cushion of savings.

Then there was culture. Janus had a Denver-born, entrepreneurial streak—portfolio managers used to autonomy and a kind of cowboy confidence that came from doing things far from New York. Henderson was shaped by British institutional norms and the added layers of having operated inside a larger corporate structure. Even if both sides wanted harmony, geography alone made it harder: two headquarters, two time zones, and two ways of running a shop.

And the co-CEO structure, a familiar compromise in “mergers of equals,” came with built-in ambiguity. When Weil and Formica disagreed, who broke the tie? Whose strategy won? For employees, the optics were balanced, but day-to-day decision-making could get muddy.

That muddiness didn’t last long. In August 2018, Janus Henderson dropped the co-CEO model and appointed Dick Weil as sole CEO. The company framed it as a natural next step: integration had progressed, the co-CEO structure had “achieved its goals,” and it was time to return to a single leader. Formica resigned effective immediately and left the firm by year-end, later becoming CEO of Jupiter Asset Management.

In other words: within fourteen months of closing, the most symbolic feature of “merger of equals” disappeared. The rhetoric gave way to the reality that one side ultimately held the wheel.

And that gets to the uncomfortable truth at the center of this deal. However elegantly it was packaged, the Janus Henderson merger was defensive. Neither firm had a compelling standalone path to outmuscle BlackRock, Vanguard, or Fidelity. Neither could count on organic growth to outrun the industry’s shift toward passive and lower fees. Combining bought time and reduced costs—but it didn’t change the competitive dynamics threatening both businesses.

Mergers can make an organization leaner. They can’t, by themselves, make a disrupted business model whole.

VI. Post-Merger Reality: The Outflows Begin

On integration, Janus Henderson did what it said it would do.

By 30 June 2018, the group reported about $107 million of annualised, run-rate, pre-tax net cost synergies. Management said it expected recurring annual run-rate, pre-tax net cost synergies of at least $125 million within three years of closing. Technology platforms were consolidated. Back-office functions were streamlined. Office space was rationalized. The merger machine, at least on the expense line, was doing its job.

But asset management isn’t won in the back office. It’s won in flows. And the flows were going the wrong way.

According to the Financial Times, Janus Henderson suffered $84 billion in outflows from the beginning of 2017. Scale didn’t change the industry’s physics. Even as a larger combined firm, Janus Henderson was still caught in the same undertow pulling investors toward passive products and cheaper beta.

You could see it in the cadence of the quarterly reports. As of 30 June 2018, Janus Henderson managed $370.1 billion, slightly down from $371.9 billion at the end of March. Over that quarter it suffered $19.8 billion of redemptions. And the pattern kept repeating: a few strategies gathering assets, others leaking more, the net number hovering negative, and total AUM moving more on what markets did than on anything the firm controlled.

The underlying business model made that painful in a very specific way. Management fees—charged as a small percentage of AUM—were the engine. When markets rose, that could mask outflows for a while; asset prices lifted the base, and revenue held up. When markets fell, the same mechanics turned vicious: market declines and client redemptions hit AUM at the same time, and revenue dropped faster than costs could realistically follow.

In 2017, Denver-based Janus Capital and London-based Henderson Group merged to create what was meant to be a stronger global asset manager. The years after didn’t exactly validate the pitch. So when Janus Henderson finally reported in early 2024 that more investors were adding money than pulling it out—the first quarter of net inflows since the merger closed—Financial Times editor Robin Wigglesworth couldn’t resist. In a column titled “Janus Henderson inflows! INFLOWS!!”, he joked that someone at the firm had “clearly made some kind of human sacrifice.”

Leadership turmoil only added to the sense that the company was still searching for footing. Dick Weil, who had become sole CEO after the co-CEO model ended, announced he would step down at the end of the first quarter of 2022. The timing was awkward: the news came two days after the firm’s largest shareholder called for a board shake-up. Janus Henderson said Weil would retire on 31 March 2022, ending a run that stretched back roughly a dozen years as a top leader in the organization.

Behind the scenes, activist pressure was building. Trian Fund Management, founded by Nelson Peltz, had assembled a large position in the stock. Its stake grew to 15.43%, and it pushed for changes including adding new independent directors. Weil’s exit removed a potential barrier to a more aggressive reset.

The successor was not an obvious “house candidate.” Ali Dibadj joined Janus Henderson as Chief Executive Officer in June 2022, taking responsibility for the firm’s strategic direction and overall management and performance.

Dibadj arrived with a rare blend of operator, investor, and analyst credibility. Before Janus Henderson, he held several roles at AllianceBernstein, most recently as CFO and head of finance and strategy from 2020 to 2022. In overlapping years he also served as an equities portfolio manager from 2017 to 2022, and earlier as a senior analyst from 2006 to 2020. Before that, he spent nearly a decade in consulting at McKinsey & Company and Mercer.

He also knew the industry’s scorekeeping system better than most CEOs ever will. As a senior analyst for AB Bernstein Research Services from 2006 to 2020, he was ranked the number one analyst 12 times by Institutional Investor—meaning he’d spent years evaluating asset managers the same way the market would now evaluate him. And unlike many internal successors, he didn’t owe allegiance to “old Janus” or “old Henderson,” which gave him room to redraw lines that insiders might not touch.

Coming out of early meetings with employees and clients, Janus Henderson framed its priorities as “protecting and growing our core businesses, amplifying our strengths, and diversifying where clients give us the right.” The words were familiar. The implication wasn’t. Dibadj packaged the plan into a three-part framework—Protect & Grow, Amplify, and Diversify—and while the language sounded like standard corporate strategy, the emphasis began to shift in concrete directions, especially toward ETFs and private markets.

VII. The Fight for Relevance: Adapting to New Reality (2020-Present)

The COVID shock of March 2020 was a live-fire drill for every asset manager. Markets swung violently, clients demanded answers in real time, and entire investment and operations teams were suddenly working from their kitchens. Janus Henderson made it through without major operational breakdowns. But the experience changed the company anyway. Remote work stuck for much of the organization, shrinking real-estate needs while making collaboration—and culture—harder to maintain across time zones.

More importantly, the pandemic didn’t create new forces in asset management. It poured gasoline on the ones already burning. Digital distribution stopped being a “nice to have.” Technology-enabled service became the expectation. And the advantage of scale—especially scale that could fund platforms, tools, and data—became even more obvious.

This is where Ali Dibadj’s “Protect & Grow / Amplify / Diversify” framing started to translate into actual moves. The biggest swing was ETFs—specifically, active ETFs.

Janus Henderson leaned hard into active fixed income ETFs, and one product in particular became the banner carrier: the Janus Henderson AAA CLO ETF (JAAA). In 2024, JAAA’s assets grew sharply—starting the year around $5.3 billion and ending it at $16.6 billion. It later surpassed $20 billion in assets. Along the way, it became the largest CLO ETF by AUM and ranked first in year-to-date net flows among active ETFs.

For a firm that had spent years bleeding assets in slow motion, this mattered for more than the headline number. It was proof that Janus Henderson could still win when it paired investment expertise with a wrapper clients actually wanted.

CLO ETFs sit in a specialized corner of the market. They offer exposure to floating-rate credit through an ETF structure that emphasizes liquidity, transparency, and tax efficiency—features that resonate with today’s allocators. Janus Henderson saw that niche early, executed, and captured real first-mover momentum. By this point, the firm managed more than $30 billion in active fixed income ETFs, and five of those ETFs each had more than $1 billion in assets.

ETFs weren’t the only diversification push. Private markets—especially private credit—were the other. In October 2024, Janus Henderson completed its acquisition of Victory Park Capital Advisors, LLC, a global private credit manager, after announcing the deal in August.

Victory Park fit a specific strategic gap. It complemented Janus Henderson’s securitized credit franchise and its expertise in public asset-backed and securitized markets, while pushing the firm further into private credit. Founded in 2007 by Richard Levy and Brendan Carroll and headquartered in Chicago, Victory Park invested across industries, geographies, and asset classes for a long-standing institutional client base.

The logic was clear. Traditional active management—especially in public equities—was becoming harder to defend on fees. Private credit, by contrast, had grown rapidly as banks pulled back from parts of middle-market lending. It also offered a different economic profile: higher fees and less direct vulnerability to passive “set it and forget it” competition.

And Janus Henderson pushed its ETF ambitions across the Atlantic too. In May 2024, it acquired Tabula Investment Management, which specialised in European exchange-traded funds. By July, Tabula was part of Janus Henderson—an attempt to extend the ETF playbook into Europe, where adoption had historically lagged the U.S. but was gaining momentum.

By the end of 2024, the scorecard finally began to look different. The firm reported that 65%, 72%, 55%, and 73% of AUM outperformed relevant benchmarks over one-, three-, five-, and 10-year periods, respectively, as of December 31, 2024. Assets under management rose 13% year over year to $378.7 billion. And, crucially, flows flipped: fourth-quarter 2024 net inflows were $3.3 billion, bringing full-year 2024 net inflows to $2.4 billion, versus net outflows of $0.7 billion in 2023.

Then came 2025, and the momentum held. As of September 30, 2025, Janus Henderson reported AUM of about $484 billion, up 27% year over year and 6% quarter over quarter. That quarter marked the sixth consecutive quarter of positive net flows, and the firm said AUM had reached a record high.

Six straight quarters of inflows was a different world from the post-merger years, when outflows felt like a law of nature. Whether it was durable repositioning, friendly markets, or clients temporarily rotating into the right categories was still an open question. But for once, the trend line was pointing the right way.

In the first quarter of 2025, Janus Henderson also announced a strategic partnership with The Guardian Life Insurance Company of America. The partnership included Janus Henderson managing Guardian’s $45 billion investment-grade public fixed income portfolio for its general account, along with up to $400 million in seed capital.

Mandates like that don’t happen because of slick marketing. They’re a vote of confidence from an institutional client that lives and dies by risk management. And they reinforced what was becoming the company’s clearest angle: fixed income and credit—areas where active can still make a credible case.

Still, even as flows improved and new platforms took shape, the existential question didn’t go away. What is the unique value proposition that justifies active-management fees?

In equities, passive products track indexes for next to nothing, and active managers have to clear a brutally high bar just to break even after fees. In fixed income and alternatives, the argument for active is stronger—but so is the competition, and many of the best players are either massive specialists or nimble boutiques.

Janus Henderson was no longer just trying to survive the merger. It was trying to prove—product by product—that it still belonged in a world where “active” was no longer the default.

VIII. The Competitive Landscape & Strategic Alternatives

By the mid-2020s, asset management had started to look like a barbell: huge players on one end, sharp specialists on the other, and a brutal squeeze in the middle.

On the scale end sit BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street. A massive share of passive index-fund money is concentrated with those three, and the advantage compounds. They can spread technology, operations, and compliance across trillions of dollars. Their brands are defaults in retirement plans and model portfolios. And their fees are so low that smaller firms can match the price only by volunteering to lose money.

On the boutique end, the game is different. Specialist firms—hedge funds, private equity shops, and focused equity managers—earn premium fees by selling something that isn’t easily replicated: genuine differentiation, scarce access, or a very specific kind of risk exposure. They don’t try to win on price. They win by being meaningfully unlike the index.

And then there’s the middle—where Janus Henderson lived for most of this story. Too large to be a tightly focused boutique with a single, concentrated edge. Too small to enjoy BlackRock-level scale economics. And often offering products where passive alternatives are “good enough” at a fraction of the cost.

Different competitors found different ways to respond. T. Rowe Price protected profitability with deep advisor relationships and retirement-plan distribution. Schroders pushed hard into private assets. Franklin Templeton pursued scale and breadth through acquisitions, including its 2020 deal for Legg Mason.

But the failures were just as instructive. The industry is littered with mergers that looked great in the banker deck and then bled value in integration. Acquisitions that diluted culture without adding real capabilities. Cost-cutting programs that improved margins in the short run while quietly weakening the investment engine clients were paying for.

The early-2000s trading scandal era, in particular, left permanent scar tissue. Some firms didn’t make it—Strong and PBHG are examples—while others, like Janus and Putnam, survived but never fully climbed back to their pre-scandal, pre-tech-crash highs. At least one implicated firm, MFS, came out the other side stronger.

So by 2024 and 2025, Janus Henderson’s realistic menu of strategic paths looked something like this:

Stay independent and transform: Keep building active ETFs, expand private markets, invest in technology and distribution. Risk: transformation takes time and capital, and the passive shift doesn’t pause while you retool.

Sell to a larger player: Become a boutique inside a bigger platform—think a Franklin Templeton, or a European bank-owned asset manager. Risk: cultural dilution, loss of identity, and the possibility the “synergies” are mostly cuts.

Go private: Step out of the public-market spotlight and invest for a longer horizon without quarterly pressure. Risk: sponsors still want an exit, often in a five-to-seven-year window, and the playbook can tilt toward financial engineering and cost reduction more than reinvention.

Harvest and return capital: Treat the business as a shrinking annuity—limit reinvestment and send cash back via dividends and buybacks. Risk: a slow-motion wind-down that drains morale, talent, and client confidence.

The Trian and General Catalyst acquisition landed as a variant of the go-private path, framed as an investment-led reset. Janus Henderson put it this way: “With this partnership with Trian and General Catalyst, we are confident that we will be able to further invest in our product offering, client services, technology, and talent to accelerate our growth and deliver differentiated insights, disciplined investment strategies, and world-class service to our clients.”

Nelson Peltz, CEO of Trian, struck the insider-activist tone: “As a significant shareholder of JHG with Board representation since 2022, we are proud of the Company's performance in recent years led by Ali and his outstanding team. We see a growing opportunity to accelerate investment in people, technology, and clients.” Hemant Taneja, CEO of General Catalyst, pushed the next-wave narrative: “We see a tremendous opportunity to partner with Janus Henderson's leadership team to enhance the Company's operations and customer value proposition with AI to drive growth and transform the business.”

IX. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces:

Threat of New Entrants: It depends on what you mean by “entrant.” Starting a traditional asset manager is hard: regulation, distribution, and the need for a credible track record all create real barriers. But newcomers don’t have to build a full mutual fund family to take your customer. Fintech and robo-advisors can insert themselves into the relationship, control the interface, and steer flows to whatever products they want. So: low risk from a new “Janus” showing up… high risk from new distribution rewriting the rules. Rating: LOW for traditional competition, HIGH for technological disruption.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: In this business, the key suppliers are people—portfolio managers and investment teams. When performance is strong, star talent can negotiate hard or walk. At the same time, the industry has no shortage of qualified professionals, which limits leverage in the aggregate. A second supplier class is technology: as platforms, data, and operational infrastructure become mission-critical, vendors gain influence too. Rating: MODERATE.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: This is the killer. Institutional clients grind fees down through procurement-like processes. Retail investors can compare costs in seconds and move money with a few clicks. Advisors increasingly build portfolios around low-cost building blocks, and switching between fund families is easier than ever. In a world where “good enough” beta is nearly free, buyers hold the power. Rating: VERY HIGH.

Threat of Substitutes: Everywhere you look. Index funds and passive ETFs replace active exposure at a fraction of the price. ETFs can also replace mutual funds with more liquidity and often better tax efficiency. Direct indexing offers customization that used to require an active manager. Private markets compete for return-seeking capital that might otherwise sit in public equities and bonds. Even crypto shows up as a speculative alternative for risk allocation. Rating: VERY HIGH.

Competitive Rivalry: Relentless. Thousands of active managers fight over a pool of assets that, in many categories, is shrinking. Performance is hard to sustain, differentiation is hard to explain, and pricing pressure never stops. And when a strategy underperforms, money doesn’t just drift away—it bolts. Rating: EXTREME.

Overall Industry Attractiveness: POOR and getting worse. The economics are compressing, the customer is empowered, and substitutes keep improving. Even if new traditional entrants struggle, incumbents can still get squeezed to the point where “winning” just means declining more slowly than the next firm.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis:

Hamilton Helmer’s framework asks a simple question: what, if anything, gives a company durable, defensible advantage—real “power” that lets it earn superior returns over time? Run Janus Henderson through that lens and the answers are sobering.

Scale Economies: WEAK. Scale helps in asset management because so much of the cost base—technology, compliance, corporate functions—can be spread across more assets. But the real scale game is dominated by the giants. Janus Henderson’s roughly $480 billion is meaningful, yet it sits in a different universe from BlackRock at around $10 trillion and Vanguard at roughly $9 trillion. The level of scale that produces true cost leadership is simply out of reach.

Network Effects: NONE. Your returns don’t improve because more people invest with the same manager. If anything, too much AUM can become a constraint as strategies hit capacity.

Counter-Positioning: NEGATIVE. This is the core strategic trap. Janus Henderson is the incumbent being counter-positioned against by the passive revolution. Vanguard and other passive providers built a model designed to win on low fees and broad exposure. A traditional active manager can’t just match that pricing without breaking its own economics—so the disruptor’s strength becomes the incumbent’s bind.

Switching Costs: WEAK. Some institutional mandates are sticky because manager searches, due diligence, and governance take time. Taxes can create friction for some retail investors. But overall, moving money is easier than it’s ever been, and huge pools of assets—like retirement accounts—can shift with minimal constraint.

Branding: MODERATE. Janus still carries name recognition, and Henderson brings a layer of British institutional credibility. But in asset management, brand gets you considered. It doesn’t get you forgiven. If performance lags or fees look out of line, clients leave.

Cornered Resource: WEAK. There’s no proprietary dataset, protected technology, or unique intellectual property that can’t be replicated. The closest thing to a cornered resource—star portfolio managers—isn’t truly cornered, because they can resign and take their reputation elsewhere.

Process Power: WEAK. Investment processes can be copied. Operational best practices spread fast. And any repeatable edge in public markets tends to get competed away over time.

Power Assessment: By Helmer’s definition, Janus Henderson doesn’t have durable power. That’s not a knock on the people running the firm; it’s a reflection of the structure of the industry it operates in. Without power, competition pushes returns toward commodity economics—especially when your main rival is a product explicitly engineered to win on price.

For long-term investors, the implication is straightforward: when a company lacks durable advantage, strategy and optionality start to matter more than moat. In that light, the Trian and General Catalyst deal isn’t just an endpoint—it’s a recognition that the public-market version of this fight was getting harder to justify.

X. Business Model Deep Dive & Unit Economics

Asset management has one of the cleanest revenue formulas in finance—and one of the most unforgiving. Revenue is simply fees multiplied by assets under management. Fees are quoted in basis points, or hundredths of a percent. Charge 50 basis points on $100 billion, and you get $500 million a year. Easy to explain. Hard to live with.

Because that simplicity hides the trap: if the assets shrink, the revenue shrinks immediately. There’s no contract backlog. No multiyear subscription you can count on. Just a percentage skim on a pile of money that can rise, fall, or walk out the door.

For Janus Henderson, management fees on AUM made up more than 90% of revenue. In other words, the company’s top line mostly moved with two things: markets and client flows. By the second quarter of 2025, its net management fee margin was 47.5 basis points. That blended rate was really a portrait of the firm’s product mix: equity strategies typically carry higher fees, fixed income tends to be lower, and alternatives can be higher still.

Then comes the part that makes this business feel like a lever. AUM sensitivity cuts both ways. If public markets drop 10%, your AUM falls with them. If investors also redeem during stress—exactly when they’re most likely to panic—revenue can fall far more than the market move alone would suggest. It’s operating leverage in its purest form: glorious in bull markets, punishing in bear markets.

The cost side looks familiar for asset managers, and that familiarity is the problem. You can’t cut fast without cutting into the thing you sell.

People costs (40-50% of revenue): Portfolio managers, analysts, traders, sales teams, marketing, operations, compliance, legal, technology, and leadership. This is a human-capital business. And because performance and client service depend on the people, compensation has to stay competitive even when revenue is under pressure.

Distribution and marketing (15-20%): Platform fees paid to wealth managers, advertising, events, relationship management. Distribution has gotten more expensive as intermediaries demand a bigger share of the economics.

Technology (10-15%): Trading and portfolio systems, risk analytics, reporting, cybersecurity, and data. Even a traditional asset manager can’t treat tech as optional anymore, and the required investment tends to rise every year.

Occupancy and other (10-15%): Real estate, travel, regulatory and filing costs, audit, and corporate overhead.

In good times, well-run active managers have historically posted operating margins in the 30% to 40% range. Janus Henderson’s late-2024 results showed what “good times” can look like even in a tough industry: fourth-quarter 2024 diluted EPS of $0.77, and adjusted diluted EPS of $1.07, up 30% year over year and 18% quarter over quarter. The company also highlighted its liquidity and cash generation, including about $1.2 billion in cash and cash equivalents and $695 million of cash provided from operating activities in 2024.

But the industry’s margin story is a squeeze play. When AUM falls, revenue drops faster than you can safely cut costs, and margins compress. When AUM grows only slowly while fees drift down under passive competition, revenue growth can lag cost inflation, and margins compress again. The only clean path to margin expansion is sustained AUM growth without giving away too much price—and that’s the hardest combination to manufacture.

This is also why active managers are structurally less profitable than passive indexers:

- They need more people and more research to justify active decisions.

- Their fee rates face constant pressure from cheap passive alternatives.

- Their flows are less predictable because performance matters more.

- Their operations are more complex: more strategies, more trading, more moving parts.

And then there’s capital allocation—the part that tells you what management thinks the business is. In 2024, the board returned $458 million through dividends and share buybacks. That kind of return signals confidence and rewards shareholders. It also means fewer dollars available for reinvention—technology upgrades, distribution buildouts, and capability buys that might matter more five years from now than next quarter.

This tension is where the classic financial-services private equity playbook starts to hover in the background: buy an active manager, cut costs, harvest cash, and selectively invest where growth still exists. In the Janus Henderson take-private, Trian and General Catalyst presumably saw the same puzzle and the same opportunity—tighten the machine where it’s bloated, while funding the few bets that can still compound.

XI. Key Inflection Points & Counterfactuals

Every company story has a few moments where the fork in the road is obvious—usually in hindsight. For Janus Henderson, the most interesting question isn’t “who made the wrong call?” It’s whether any call was going to look good once the industry shifted under their feet.

2000-2003: The tech bubble collapse and scandal

Janus didn’t just participate in the late-’90s growth boom. It became a symbol of it. That worked spectacularly in 1998 and 1999—and then it became an anchor in 2000 through 2002, when concentrated exposure turned a market reversal into a firm-defining drawdown. The obvious counterfactual is diversification: what if Bailey and the team had built out fixed income, international, or value capabilities before the crash, when they still had momentum, brand heat, and the freedom to invest?

The later scandal only deepened the damage, but the first punch was performance. In this version of the story, earlier diversification doesn’t magically avoid the bear market. It just gives clients more reasons to stay, and gives the firm more places to earn trust while the flagship funds recover.

2008-2012: The financial crisis and the passive inflection

If 2000 was Janus’s identity crisis, 2008 was the industry’s. After the financial crisis, the case for paying active fees got harder to defend, and passive investing accelerated from “niche idea” to default setting. The counterfactual here is uncomfortable because it was available to almost everyone: what if Janus or Henderson had built real passive capabilities early?

Index funds weren’t patented. The barrier wasn’t technology—it was belief. Active managers largely viewed indexing as intellectually lazy and economically unattractive, because low fees looked like a race to the bottom. That cultural resistance bought them short-term margin protection, and cost them long-term positioning.

2015-2016: The merger decision

By the time Janus and Henderson decided to combine, the list of options was already shrinking. They could have sold to a larger player—names like Amundi, Franklin Templeton, or a European bank come up in any plausible “what if.” That might have brought more distribution and more balance-sheet support. They could have stayed independent and tried to protect culture and agility, accepting the risk of being sub-scale in a fee-compressing world. Or they could have gone harder on transformation: sharper cost cuts, a tighter product set, and selective investment in whatever still had growth.

Instead, they chose the middle path: merge, cut costs, and try to buy time. It avoided an immediate endgame, but it also committed them to years of integration in a market that wasn’t going to pause.

2017-2020: Integration vs. transformation

After the deal closed, management focused on what mergers reliably deliver: synergies. Platforms were consolidated. Products were rationalized. Duplicated functions were removed. Necessary work, but it came with an opportunity cost. What if the company had pushed earlier and harder into ETFs? What if it had made bigger capability buys sooner? What if it had been willing to break more glass culturally to force a clearer strategy?

Integration tends to consume bandwidth exactly when a disrupted company needs its most creative, outward-looking years. Janus Henderson got leaner. The harder question is whether it got meaningfully more relevant fast enough.

2022-present: The Dibadj era

Ali Dibadj’s arrival marked a real strategic shift, not just another reorg. The active ETF push and the move into private markets helped change the flow narrative, and the return to net inflows suggested the repositioning was starting to land. But the take-private deal with Trian and General Catalyst also hinted at another reality: the public markets may not have been willing to wait for the transformation to fully mature.

The uncomfortable truth about counterfactuals is that they can flatter us into thinking there was a clean “right answer.” In a business facing secular disruption, there often isn’t. There are only tradeoffs—different versions of hard. Janus Henderson, for much of this story, executed competently inside severe constraints. The constraints were the problem.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Thesis

The Bull Case:

Valuation: Before the Trian/General Catalyst announcement, Janus Henderson traded at roughly 2% to 3% of AUM, versus around 5% to 6% for higher-quality peers like T. Rowe Price. That gap was the market’s way of saying, “We don’t believe this growth is real.” For bulls, it was also the setup: if flows stabilized and the new growth engines kept working, the multiple didn’t need to become heroic to generate upside.

Stabilization evidence: By 2025, the company had put together six consecutive quarters of positive net flows and reported about a 7% organic growth rate. If that pace held, it would change the narrative from “active manager in slow decline” to something closer to “turnaround with a working playbook.”

Dividend yield: Before going private entered the picture, the stock offered a roughly 5% to 7% dividend yield. For income-oriented holders, that mattered: you could get paid while waiting to see whether the ETF and private-credit bets became durable, not just timely.

Active management cyclicality: Active versus passive isn’t a one-way street in every environment. When markets get choppier—higher volatility, lower correlations, more dispersion—stock and bond selection can matter more. In those regimes, active managers have a better shot at earning their fees and keeping clients from defaulting to “own the index and move on.”

ESG and sustainable investing: Particularly in Europe, regulation and client preferences can push capital toward sustainability-oriented mandates. In theory, that’s a place where active management can argue it adds real value through engagement, research, and portfolio construction that an index simply won’t do.

ETF success: The CLO ETF franchise was the proof point that Janus Henderson could meet modern demand with a modern wrapper and still win flows. The bull case assumes that wasn’t a one-off—that the firm could replicate the formula in other categories where investors want active risk-taking, but not active-fund friction.

Acquisition target value: Even if the public market stayed skeptical, a strategic buyer might value Janus Henderson differently—paying up for distribution, product capabilities, or geographic footprint. The Trian/General Catalyst deal itself underlined that point, priced at $49 per share and representing an 18% premium to the unaffected price.

The Bear Case:

Secular decline: The biggest bear argument is that none of the improvements matter if the industry tide keeps pulling out. Active management’s core problem hasn’t changed: most strategies don’t beat passive alternatives over time, especially after fees. One datapoint captures the brutality here: just 7% of active U.S. large-cap managers both survived and beat their average passive rival over the decade through December 2024.

No competitive moat: The Hamilton 7 Powers lens is unforgiving. If you don’t have durable power—scale leadership, switching costs, a cornered resource, something—competition eventually compresses you. In asset management, that compression shows up as fee pressure, higher distribution costs, and fragile client loyalty.

Continued outflow risk: Flows can flip fast. A few quarters of underperformance, a change in risk appetite, or a better competing product, and the “stabilization” story can unwind. The post-merger years proved how quickly outflows can become the default setting.

Operational complexity: A transatlantic merger buys breadth, but it also buys friction—multiple regions, multiple cultures, and a longer path from decision to execution. Even years later, integration can keep creating drag in ways that are hard to measure until you feel them.

Talent risk: This is still a people business. Star portfolio managers can leave, and when they do, track records and client relationships often leave with them. Any firm that relies heavily on a handful of teams is vulnerable to key-person risk.

Disruption acceleration: The substitutes keep getting better: direct indexing, AI-powered portfolio construction, and new distribution models that route clients toward low-cost building blocks by default. Even if Janus Henderson is transforming, the rest of the market isn’t standing still.

Valuation trap history: Active managers have tempted value investors for years: cheap multiples, big buybacks, generous dividends—then more outflows and another reset lower. In declining industries, “cheap” can be a long-term condition, not a temporary mispricing.

What Would Need to Be True for Bulls to Be Right:

- Market conditions shift toward volatility and dispersion that reward security selection

- The active ETF franchise scales into multiple billions across additional categories

- Private-markets expansion produces meaningful revenue and real differentiation

- Cost discipline holds margins even as fee pressure continues

- Investment performance stays strong enough to keep client confidence through cycles

The go-private transaction effectively mooted the public-market investment debate—but it also validated the broader point behind the bull case: strategic optionality had value. Trian and General Catalyst were, in effect, underwriting the idea that with tighter execution and more freedom to invest for the long term, Janus Henderson could create value through some combination of operational improvement, repositioning, and an eventual exit—whether back to public markets, to a strategic buyer, or to another sponsor.

XIII. Lessons & Takeaways: The Playbook

For Operators:

Mergers in declining industries are desperate measures. The Janus Henderson deal largely did what these deals are designed to do: extract cost savings. Synergies showed up, systems were integrated, and overlap was cut. But a merger can’t fix a broken value proposition. Two firms facing the same secular headwinds don’t combine into a growth engine; they combine into a bigger version of the same fight. The spreadsheet gives you breathing room. It doesn’t give you a moat.

Defensive strategies have limits. In a disrupted business, scale is not the same as safety. Cutting costs can protect margins for a while, but it also starves the very investments that might create a new path—technology, distribution, new products, and talent. The defensive playbook buys time. It rarely changes the destination.

Culture matters immensely. “Merger of equals” sounds fair, but it often creates balance without clarity. Decisions slow down, politics creep in, and sooner or later someone has to be in charge. Denver and London. Entrepreneurial autonomy and institutional process. Two legacies trying to coexist. Janus Henderson’s fast exit from the co-CEO model was the tell: compromise is a bridge, not an operating system.

Brand alone isn't a moat. Janus still carried echoes of 1990s glory. Henderson brought the polish of British institutional credibility. But brand only gets you shortlisted. When performance disappoints or fees look unjustifiable next to “good enough” passive alternatives, clients don’t stay out of nostalgia.

The pivot timing problem. By the time disruption feels undeniable, you’re usually late. Janus Henderson’s ETF push eventually worked—real flows, real momentum—but it came after passive and ETF adoption had already become the default. Early recognition gives you room to evolve deliberately. Late recognition forces you to lunge.

For Investors:

Beware value traps. Cheap can stay cheap. Active managers trading at a discount to AUM have tempted investors for years, and many of them kept getting cheaper as outflows, fee pressure, and margins did their slow grind. A low multiple isn’t a margin of safety if the underlying pool of earnings is shrinking.

Industry structure matters more than company quality. Strong management and competent execution can’t overcome brutal economics. Janus Henderson had plenty of smart people making sensible moves. It still spent years struggling because the industry’s forces—buyers with power, substitutes everywhere, and relentless price pressure—were stacked against it.

Follow the flows. In asset management, flows are the scoreboard. AUM and net flows show up before the income statement does: they drive revenue, dictate strategic freedom, and shape market perception. Persistent outflows are a warning flare. Even modest, sustained inflows can change what’s possible.

Disruption is relentless. Indexing didn’t win overnight. It just kept winning. Vanguard’s 1970s idea has been compounding through every cycle for decades, and the direction of travel hasn’t meaningfully reversed—if anything, it accelerated as ETFs and digital distribution made “cheap beta” even easier to buy.

The indexing lesson: Sometimes the simplest strategy wins. Over long horizons, fees are destiny. A seemingly small annual fee gap compounds into a dramatic difference in wealth. That math did more to reshape investor behavior than any marketing campaign ever could.

For Founders & Strategists:

Build genuine power early. The Helmer lens is unforgiving: without scale leadership, switching costs, network effects, a cornered resource, or true process power, competition drags you toward commodity economics. Janus Henderson’s story shows what happens when you’re well-run but structurally exposed. Founders should hunt for power sources before growth makes the absence easy to ignore.

Recognize secular vs. cyclical. Cycles recover; secular shifts rewrite the rules. Mixing them up leads to bad decisions—either selling a good business in a temporary downturn or clinging to a structurally declining one while waiting for mean reversion. The active-to-passive shift has behaved like a secular change.

Distribution transformation threatens incumbents. When the customer interface changes, the profit pool moves. Advisors to models. Mutual funds to ETFs. Human gatekeepers to platforms and algorithms. Incumbents built for the old distribution world are forced to fight with legacy costs and legacy incentives while new channels route money elsewhere.

The margin of safety problem. Asset management has harsh operating leverage. When AUM slips, revenue falls immediately, but the costs—people, platforms, compliance—don’t shrink nearly as fast without damaging the product. Small outflows can create outsized earnings drops. Businesses like this either need unusually stable growth or unusually flexible cost structures, and most don’t get either.

Consider the unsaid option. Sometimes the best strategy isn’t to “transform.” It’s to return capital, consolidate, or exit gracefully. In an industry with too many players chasing a shrinking pool of fee revenue, harvesting can be more rational than heroics. It’s a conclusion few leadership teams want to put in a slide deck—but it’s often the one the market arrives at anyway.

XIV. Epilogue: Where Does Janus Henderson Go From Here?

Janus Henderson will operate as a private company, led by the current management team with Ali Dibadj continuing as Chief Executive Officer. The firm also expects to keep its main presence in both London, England, and Denver, Colorado.

The transaction is expected to close in mid-2026.

Going private opens a new chapter, but it doesn’t automatically change the plot. Sponsor ownership can be a real advantage: fewer quarterly optics games, more room to invest for longer horizons, and the kind of operational discipline that public companies sometimes struggle to sustain. But the tradeoffs are just as real. Private ownership often comes with financial engineering pressure—leverage, cost cutting, and the temptation to extract value quickly. And even “patient capital” usually has a clock: many sponsors aim to exit in five to seven years, which can narrow the range of strategic choices as that deadline gets closer.

Janus Henderson framed the deal in the language of investment and momentum: “With this partnership with Trian and General Catalyst, we are confident that we will be able to further invest in our product offering, client services, technology, and talent to accelerate our growth and deliver differentiated insights, disciplined investment strategies, and world-class service to our clients.”

The AI question hangs over everything, and General Catalyst’s involvement makes it explicit. Hemant Taneja put it this way: “We see a tremendous opportunity to partner with Janus Henderson's leadership team to enhance the Company's operations and customer value proposition with AI to drive growth and transform the business.”

The open question is what, exactly, AI transforms in asset management. Can it create new forms of alpha? Or does it simply spread investment insight more widely—making it harder, not easier, to justify active fees? Machine learning has shown promise in areas like signal processing and factor discovery, but evidence of durable, repeatable alpha at scale is limited. The nearer-term payoff may be less about beating the market and more about running the firm better: faster research workflows, smarter risk management, better personalization for advisors and clients, and lower operating costs.

At the same time, wealth management keeps changing the economics of the whole industry. Advisors are increasingly building portfolios through model platforms, which concentrates flows into a smaller set of approved strategies. Direct indexing keeps improving, offering customization that mutual funds can’t easily match. And the asset manager’s job is shifting from “product provider” to “solutions partner,” a framing that tends to reward firms with breadth, distribution, and technology-enabled service—not just a lineup of funds.

Then there’s the next-generation challenge, which may be the most fundamental of all. Younger investors often experience markets through Robinhood, Coinbase, and social-media-driven narratives, not through a traditional advisor and a mutual fund prospectus. Their relationship with legacy asset managers is tenuous at best. Whether Janus Henderson—or any traditional manager—can build real relevance with Gen Z investors is still an open question.

So what does success look like under private ownership? Something unglamorous but powerful: stabilized assets, consistent net inflows, and better margins through operational efficiency. The growth engines would need to scale—active ETFs, private markets, and whatever “solutions” means in practice—enough to support an eventual exit, whether that’s an IPO, a strategic sale, or another sponsor. And the exit would need to validate the core bet: that Janus Henderson can become more than a well-run participant in a shrinking game.

The realistic endgame, given the industry’s direction, is that Janus Henderson remains either a consolidator or a consolidation target in a fragmenting market. Active management won’t disappear. It will survive in specialist boutiques, in alternatives, and in outcome-oriented strategies where investors want something other than pure beta. But the classic mutual fund model will keep facing pressure. As the company itself put it: “During our 91-year history, Janus Henderson has been public and private at different times, and it has never lost focus on investing in a brighter future together for its clients and employees.”

In the end, the Janus Henderson story is about trying to fight industry change with scale and efficiency when what’s really required is reinvention. The 2017 merger was rational given the shrinking set of alternatives—but rationality couldn’t repeal structural disruption. The take-private deal is the next attempt to find durable positioning in a business where the ground keeps moving.

For strategy observers, it’s a case study in the limits of defensive consolidation. For investors, it’s a reminder that disrupted industries don’t hand out easy turnarounds. And for operators living through their own version of this shift, it’s both warning and signal: transformation can happen—but it’s never a single deal. It’s a long campaign.

XV. Key Metrics to Watch

If you want a simple dashboard for whether Janus Henderson is actually changing its trajectory—not just benefiting from a good tape—two numbers do most of the work.

1. Organic Net Flows (as % of beginning AUM): This is the cleanest read on whether clients are choosing Janus Henderson, independent of what markets happen to do. Sustained positive organic growth in the low single digits—say, above 2% to 3% annually—would suggest the firm is finding durable relevance. Sustained negative organic growth below about -3% would point to continued market share loss. That’s why the return to positive flows matters so much: the 7% organic growth rate reported in Q3 2025 is less a nice datapoint than the core “are we turning the ship?” signal.

2. Net Management Fee Margin (in basis points): This is the revenue yield on the asset base—what clients, on average, are paying for the firm’s management. If that margin keeps sliding, it’s a sign that competition and product mix are grinding the model down. If it holds steady or rises, it suggests at least some pricing power. The 47.5 basis point margin is the one to watch, especially as growth shifts toward categories that tend to carry lower fees.

XVI. Further Reading

Books & Long-Form Resources:

-

"The Bogle Effect" by Eric Balchunas - A clear, entertaining account of how index funds went from a fringe idea to the force that rewired the entire asset-management business.

-

"Trillions" by Robin Wigglesworth - A Financial Times reporter’s guide to the rise of passive investing—and what happens when the “market” becomes the product.

-

"The Incredible Shrinking Alpha" by Larry Swedroe - A data-heavy look at why beating the market has gotten harder, and why so much “alpha” disappears after fees.

-

"More Money Than God" by Sebastian Mallaby - The long arc of hedge funds and modern active management, and the incentives that shaped today’s investment landscape.

-

Morningstar Active/Passive Barometer (semi-annual) - The go-to scoreboard for whether active managers actually deliver better outcomes than passive alternatives, category by category.

-

Janus Henderson Annual Reports (2017-2024) - The primary record of what the merger promised, what integration delivered, and how the strategy evolved once reality set in.

-

Investment Company Institute (ICI) Factbook - The industry’s flow and fund-structure bible: a great way to see the passive shift in hard numbers over time.

-

Cerulli Associates Industry Research - Deep, institutional-grade research on where assets are moving, how distribution is changing, and who’s winning.

-

S&P SPIVA Scorecards - The most-cited benchmark of active-versus-index performance, and a recurring reminder of how narrow the odds are.

-

Hamilton Helmer's "7 Powers" - The competitive-advantage framework used throughout this story to ask the uncomfortable question: what, if anything, is defensible here?

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music