InvenTrust Properties Corp: The Grocery-Anchored REIT That Survived the Retail Apocalypse

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

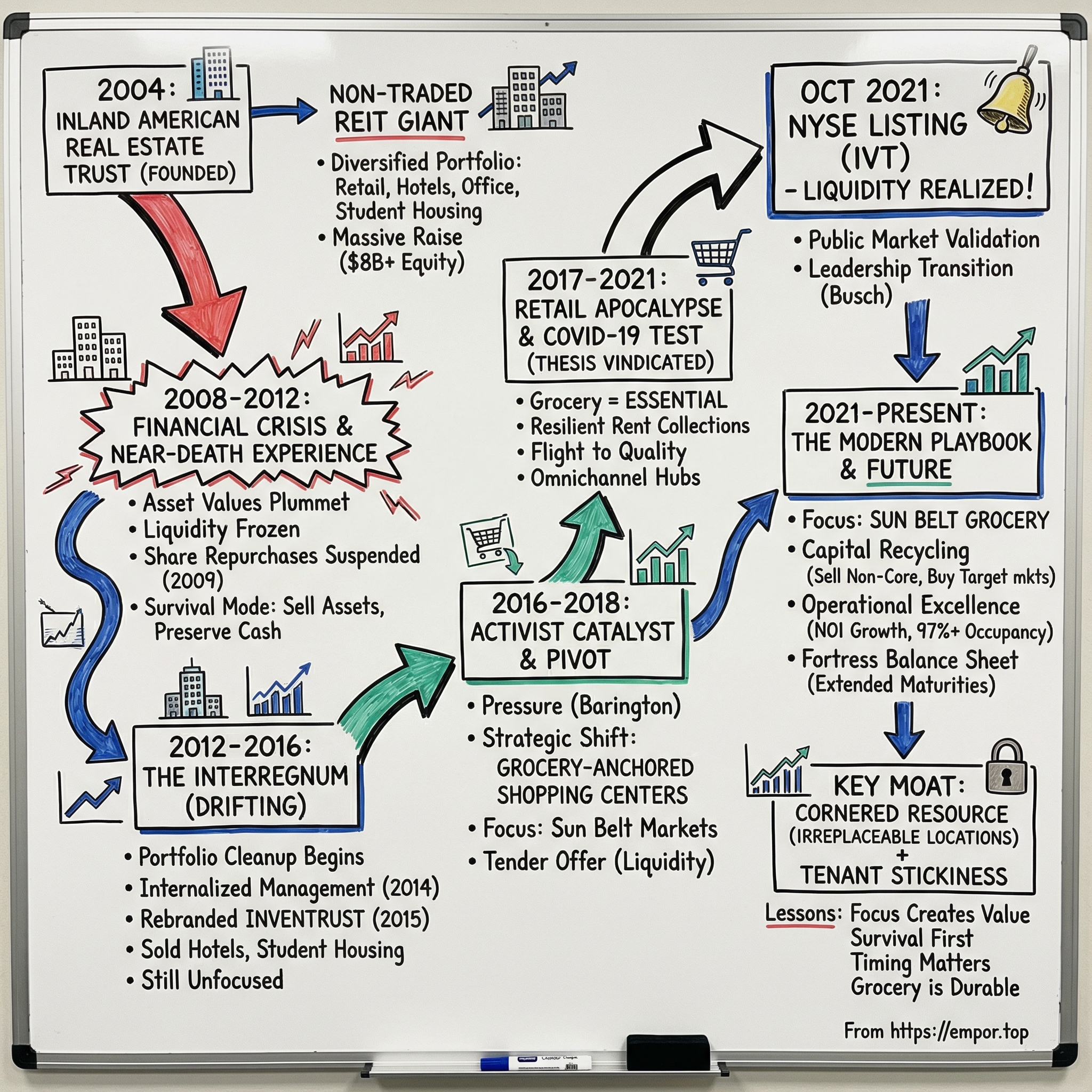

Picture this: October 12, 2021. The closing bell at the New York Stock Exchange is about to ring, and for InvenTrust, it isn’t just ceremony. Daniel “DJ” Busch, a former Wall Street research analyst turned CEO, is on the trading floor with his team as the company marks a milestone years in the making. InvenTrust’s shares have just begun trading on the NYSE under the symbol IVT, and at 4:00 p.m. Eastern, management rings the Closing Bell to cap the first day.

For most companies, the bell is a victory lap. For InvenTrust, it’s something closer to validation. Because getting to that floor required surviving nearly two decades of wrong turns, reinventions, and moments when the business didn’t just look troubled—it looked finished.

By the mid-2020s, InvenTrust had become a grocery-anchored shopping center REIT with a market capitalization of roughly $2.3 billion. As of December 31, 2024, it owned interests in 68 properties totaling 11.0 million square feet. Solid numbers. But they don’t explain the real intrigue here: this company was not built in a straight line.

The central puzzle is simple to ask and hard to believe once you know the backstory: how did a company that once sprawled across property types—from hotels and student housing to offices and even private prisons—then nearly came apart during the 2008 financial crisis, and later had to stare down the “retail apocalypse,” end up as a focused, high-quality grocery-anchored REIT with one of the cleanest balance sheets in the space?

The story starts in 2004, when it was founded as Inland American Real Estate Trust. For a time, it became the largest REIT in the U.S. that wasn’t listed on a stock exchange, backed by nearly $8 billion in equity raised by its sponsor, the Oak Brook-based Inland Group. It bought broadly and aggressively. Then, years later, it rebranded as InvenTrust in 2015—and began shedding big chunks of that empire to concentrate on one thing: shopping centers anchored by grocery stores.

A few big themes weave through everything that follows. First: the survival playbook—what it takes to navigate an existential crisis with restructurings, asset sales at painful prices, and sheer persistence. Second: the activist catalyst—how investor pressure, especially from Barington Capital, forced the company to stop drifting and start choosing. Third: the grocery-anchored thesis—the bet that necessity retail, and supermarkets in particular, would hold up while much of brick-and-mortar got pummeled by e-commerce. And fourth: geography—the shift toward high-growth Sun Belt markets like Texas, Florida, Arizona, and the Carolinas.

And looming over all of it is timing. InvenTrust largely finished its portfolio cleanup and balance sheet repair just before COVID-19 put every retail landlord in America through a stress test. Grocery-anchored centers suddenly weren’t “boring”—they were essential. The thesis didn’t just hold. It was vindicated in real time.

II. REIT 101 & The Grocery-Anchored Shopping Center Thesis

Before we jump back into InvenTrust’s twists and turns, we need two quick pieces of context: what a REIT actually is, and why grocery-anchored shopping centers ended up being one of the few pockets of retail real estate that didn’t get wiped out.

REITs—Real Estate Investment Trusts—were created by Congress in 1960 with a simple goal: let everyday investors own slices of large, income-producing real estate the way they can own shares of public companies. The trade-off is the defining rule of the whole category. If a company elects REIT status and pays out at least 90% of its taxable income as dividends, it generally doesn’t pay corporate income tax. Instead, taxes are paid at the shareholder level. That structure pushes REITs to behave like cash-flow machines: less about hoarding profits, more about distributing them.

Now, zoom out to retail real estate. There’s a hierarchy.

At the top are Class A regional malls—the iconic, high-end properties anchored by department stores and packed with national brands. For decades, these were the crown jewels. Below them are power centers: big open-air complexes anchored by big-box retailers like Target, Best Buy, or Home Depot. And then you get to community and neighborhood shopping centers—smaller, more local properties designed around routine errands. These are often anchored by a grocery store, sometimes paired with a pharmacy or discount retailer.

For a long time, the mall was king. Then the “retail apocalypse” era—especially the stretch from the mid-2010s into 2019—made the mall’s weak spot impossible to ignore: department stores. As e-commerce kept pulling share, the traditional anchors started shrinking, closing, or going bankrupt. When an anchor goes dark, the whole ecosystem around it can unravel. Foot traffic drops, smaller tenants struggle, vacancies spread, and what used to feel like a destination starts feeling like a ghost town. That’s the death spiral that took down hundreds of malls.

Grocery-anchored centers play a different game. They still live in the world of retail, but they behave more like infrastructure. COVID didn’t create that truth, but it made it undeniable. Governments kept grocery stores and other essential services open throughout the pandemic because communities literally couldn’t function without them.

The underlying thesis is almost laughably straightforward: people have to eat. You can buy clothes online. You can stream movies. You can click a button and have a blender on your doorstep tomorrow. But groceries—fresh food especially—still drive frequent, habitual trips to physical stores. And even when customers order online, much of that demand is still fulfilled through stores because they’re already embedded close to where people live. That proximity and infrastructure make grocery stores a durable node in the food distribution system.

And here’s where the real estate economics get interesting: the grocery store isn’t just a tenant. It’s the traffic engine.

When a Publix or Kroger or Whole Foods is pulling in shoppers day after day, the smaller tenants around it get lifted with the tide. The nail salon, the dry cleaner, the pizza place, the fitness studio—they’re not trying to “win retail.” They’re trying to be convenient. The center becomes a neighborhood hub where you can stack errands in one trip, something e-commerce can’t fully replace.

That drives the business model for grocery-anchored REITs. Rent is the core, and much of it is structured so tenants cover many of the property’s operating costs—taxes, insurance, and maintenance—making the landlord’s income more predictable. Then you layer on steady growth: built-in rent bumps over time, plus the ability to push rents higher when leases roll and market demand supports it.

COVID poured fuel on this dynamic. As households shifted more spending toward groceries, “daily needs” shopping centers benefited from stronger traffic—and the investment world took notice. Grocery-anchored real estate started to look less like a sleepy retail subset and more like a defensive, cash-flowing asset class.

For investors, that’s the appeal: necessity over discretion, repeat visits over occasional splurges, and stability over spectacle. It’s not flashy. But in real estate, boring often means resilient—and resilient is exactly what InvenTrust needed for its second act.

III. Origins: From the Inland Real Estate Empire (2004–2007)

To understand InvenTrust, you first have to understand the Inland Real Estate Group—one of the most prolific sponsors of non-traded REITs in the U.S.

Inland’s roots run through Oak Brook, Illinois, where founder Daniel Goodwin and partners built a sprawling real estate platform. Over decades, Inland grew into a full-stack real estate machine: property management, leasing, acquisitions, brokerage, development, financing—the works. It also became a fundraising powerhouse, raising billions from everyday investors through a product most people only vaguely understood: the non-traded REIT.

Inland Investments sponsored eleven REITs starting in the mid-1990s and became the first sponsor to take a non-listed REIT to the New York Stock Exchange. It also completed six “full-cycle” non-listed REIT programs that ultimately provided liquidity to stockholders. That track record mattered, because in non-traded REIT land, investors aren’t buying a stock that trades every second. They’re buying a promise: steady distributions now, and some kind of liquidity event later.

Non-traded REITs occupy a strange corner of the investment universe. Unlike public REITs—where shares trade on an exchange and prices move with market sentiment—non-traded REITs are sold through broker-dealers at a fixed offering price, often $10 per share, regardless of what the underlying buildings might actually be worth at that moment. And because these shares generally don’t trade freely, investors can’t just hit “sell” when they change their mind. Liquidity is limited, typically constrained by share repurchase programs with strict caps and restrictions.

Inland American, like many peers, was sold at that fixed $10 price—even after real estate began cracking in 2007 and 2008. Later, when FINRA required updated per-share net asset values, Inland American reported $8.03 per share. But that number wasn’t a clean exit price; it was an estimate in a world where getting out was often the hard part.

Against that backdrop, Inland American Real Estate Trust—the vehicle that would eventually become InvenTrust—was formed in October 2004 as a non-traded REIT sponsored by the Inland Group. Its mandate was broad by design: acquire and manage a diversified portfolio of commercial real estate, including retail, lodging, and student housing.

The timing was perfect—until it wasn’t. From 2004 through 2007, commercial real estate was surging. Credit was cheap, lenders were aggressive, and property values seemed to only go one direction. The non-traded REIT industry boomed in parallel, as brokers pitched yield-hungry investors on stable income today and an eventual liquidity moment tomorrow.

Inland American launched its offering in 2005 and ultimately raised $8.3 billion, including DRIP proceeds, before the offering closed in 2009. That was one of the largest raises in non-traded REIT history, and it gave Inland American enormous buying power. By 2009, the company reported $11.4 billion in total assets spread across a massive footprint: 735 retail properties, 99 lodging properties, 47 office properties, 72 industrial properties, and 27 multifamily properties.

What emerged was diversification in the purest sense—and, depending on your point of view, a portfolio that looked less like a strategy and more like a land grab. Retail of varying quality. Hotels scattered around the country. Student housing near campuses. Office, industrial, apartments. When you raise that much money that fast, the dominant operational question becomes brutally simple: where do you put it all?

Then there was the fee structure, another defining feature of the non-traded REIT world—and one that later attracted scrutiny. Investors sued Inland American over payments to an affiliate, Inland American Business Manager & Advisor Inc. The affiliate collected a 5% fee on distributions to investors and reportedly collected $185 million in fees between 2005 and 2012. The suit alleged those fees were inflated because the “distributions” were actually return of capital, a common criticism of non-traded REITs.

By February 2014, the company was the largest non-publicly traded REIT in the United States. But the story’s irony is that size didn’t simplify anything—it multiplied everything. Hundreds of properties, multiple asset classes, and meaningful debt can look like strength in a rising market. In a falling market, it can become a maze with no obvious exits.

And that’s where this is headed. As the market peaked in 2007 and began its historic collapse, Inland American was sitting on a portfolio assembled near the top, financed with debt that would soon be far harder to refinance. The stage was set for a near-death experience.

IV. The Financial Crisis & Near-Death Experience (2008–2012)

The financial crisis of 2008 and 2009 wasn’t a normal downturn. For real estate companies that had borrowed heavily during the boom, it was closer to an extinction event.

Home prices were falling fast, refinancing windows slammed shut, and defaults started cascading through the system. But the real problem wasn’t just housing. It was credit itself. The leveraged loan market froze. Big deals that had been “done” on paper evaporated. Mortgage-backed securities and CDOs were marked down again and again as real estate values kept dropping. Major financial institutions were suddenly fighting for survival—and when the lenders are fighting for survival, the borrowers don’t get the benefit of the doubt.

That’s the environment Inland American walked into with about the worst possible setup: a giant, sprawling portfolio assembled near peak pricing, and meaningful debt that would need refinancing in the years ahead. In normal times, you refinance. In 2009, you begged. And sometimes, there was no one to beg.

One of the first visible signs that Inland American was in cash-preservation mode came on March 30, 2009, when it suspended its share repurchase program. For investors in a non-traded REIT, that repurchase program is one of the only release valves—an imperfect source of liquidity, but at least something. Turning it off was a message, whether management intended it or not: we need to keep every dollar we can.

Across corporate America, the crisis forced a brutal menu of options. You could try to renegotiate with lenders. You could sell assets into a distressed market and lock in losses just to raise cash. You could raise equity at awful prices and dilute existing holders. Or you could file for bankruptcy and use the court to buy time.

In 2009, General Growth Properties became the cautionary tale—and, depending on your view, the playbook. GGP was considered best-in-class, and it still ended up in a massive Chapter 11. The filing protected its assets from creditors who wanted to foreclose and flip properties when markets recovered. GGP used bankruptcy to restructure, reduce debt, and emerge with a more sustainable balance sheet.

Inland American avoided bankruptcy. But “survived” doesn’t mean “unscathed.” As property values plunged, the company’s reported net asset value per share fell hard over the following years—from the $10 offering price to $8.03 in 2010, then $7.22 in 2011, $6.93 in 2012, $6.50 in 2014, $4.00 in 2015, and $3.14 in 2016.

For investors who had bought in at $10—often expecting stability and liquidity down the road—the experience was punishing. Whatever the distribution checks looked like along the way, the underlying value was shrinking, and the ability to exit was limited. The “sleep well at night” product had turned into a position many people couldn’t sell at anything close to what they paid.

The only way through was a series of painful, unglamorous moves. Sell what you can. Negotiate what you must. Triage the portfolio. Simplify the business, even if it means admitting mistakes made at the top of the cycle.

That simplification showed up in blockbuster dispositions. In 2013 and 2014, Inland American sold a total of 280 net lease assets for approximately $2.6 billion. Then, in November 2014, it sold 52 hotel properties for $1.1 billion. Piece by piece, the mid-2000s conglomerate was being dismantled. Hotels—gone. Large swaths of net lease—gone. The company was getting smaller, but also getting clearer about what it could realistically manage and finance.

Then came a governance shift that mattered just as much as the asset sales. In March 2014, the company announced that functions performed by its external, related-party managers would now be performed by the REIT itself. Inland American became self-managed on March 12, 2014, and was subsequently renamed InvenTrust Properties Corp. in April 2015. The internalization didn’t magically fix the balance sheet, but it did address a long-running criticism of the non-traded REIT model: the conflicts that can come with external management and related-party arrangements. It was a step toward a cleaner, more shareholder-aligned structure.

By the end of this era, the lessons were written into the company’s DNA. Liquidity mattered more than optimization. Covenant headroom wasn’t a nice-to-have; it was oxygen. Lender relationships could decide your fate. And when resources are constrained, focus beats diversification—because in a crisis, complexity isn’t a strategy. It’s a liability.

V. The Interregnum: Drifting Without Direction (2012–2016)

Surviving a near-death experience doesn’t automatically turn into a comeback. For InvenTrust, the years from 2012 to 2016 were a frustrating in-between: the panic of the crisis had faded, but a coherent strategy hadn’t arrived to replace it.

What remained after the crisis-era triage was still a patchwork. The company was selling and simplifying, but it hadn’t yet decided what it wanted to be. It still owned properties in secondary and tertiary markets—assets that could produce cash flow, but didn’t have the growth and demographic momentum you’d want for a long-term rebuild. Tenant quality was uneven, too. Some centers had solid anchors; others relied on retailers that were already starting to look fragile as e-commerce pressure accelerated. And after years of conserving cash, deferred maintenance was part of the baggage.

Compounding all of this was the structure itself. InvenTrust was widely held, but it wasn’t listed on an exchange. Investors couldn’t just decide they were done and sell with a click. Like other non-traded REITs, the shares were sold through brokers in individual transactions, and liquidity was limited. As the company’s estimated NAV kept sliding and the “liquidity event” remained a question mark, frustration boiled over. By 2016, the company estimated its stock was worth $3.14 per share—painful for investors who had entered years earlier at $10.

Strategically, InvenTrust was stuck in a particularly awkward middle. It didn’t have the scale, balance sheet, or low-cost access to capital that the big public shopping center REITs—names like Kimco, Regency Centers, and Federal Realty—used to keep consolidating the category. Those companies could raise equity and debt more efficiently, buy better assets, and play offense. But InvenTrust also didn’t have the flexibility of a true private real estate fund that can simply liquidate when the plan isn’t working. The non-traded REIT format made it hard to reset quickly. It was a no-man’s land: disadvantaged versus public peers, but too structured to pivot like private equity.

Unsurprisingly, leadership churn and incremental moves defined the era. The company kept operating, kept paying distributions when it could, and kept disposing of assets—but without a clear, compelling end state.

Still, a few major actions did reshape the chessboard. On April 26, 2016, the company completed the spin-off of Highlands REIT, Inc. Then, in 2016, it sold its student housing platform, University House, for a gross sales price of $1.41 billion, with final net proceeds of approximately $845 million. On June 23, 2016, it completed the sale of University House Communities Group, Inc., formerly its student housing platform.

These were meaningful steps, but they didn’t feel like a bold new strategy so much as finishing the cleanup. Spinning off non-core assets into Highlands allowed InvenTrust to shed weaker properties without having to sell each one individually in a tough market. Selling the student housing platform generated significant proceeds, but it was also another tacit admission that the original “diversified everything” approach hadn’t worked.

By 2016, InvenTrust had moved a long way from the sprawling conglomerate it once was. It was narrowing toward retail, and ultimately toward grocery-anchored centers in Sun Belt markets. But the transformation still felt incomplete. Was this company going to grow into a true, scaled buyer of grocery-anchored shopping centers? Was it going to go public to finally give shareholders liquidity? Or was the real endgame to sell to someone bigger?

The uncertainty didn’t stay quiet for long. It rarely does in public-markets-adjacent land. And it was exactly the kind of situation that attracts activists—investors who look at drift, discounts, and dysfunction and see opportunity.

VI. The Activist Catalyst: Barington & Portfolio Transformation (2016–2018)

Activists tend to come in two flavors. Some show up with megaphones and a proxy fight already queued up. Others arrive with spreadsheets, quiet phone calls, and a promise: let us help you fix this before it becomes ugly.

Barington Capital Group, L.P. was comfortable being called an activist, but it didn’t brand itself as a smash-and-grab operation. Profiles of the firm described a “differentiated approach,” rooted in the idea that undervalued companies can unlock value through better governance, sharper strategy, and cleaner capital allocation. Founded in 2000 by James Mitarotonda, Barington built its reputation in consumer, retail, and industrial businesses in the U.S., pushing for change—and escalating only when boards refused to listen.

InvenTrust in 2016 was exactly the kind of situation that invites that playbook. The company had survived the crisis, internalized management, and shed major non-core platforms. But it was still drifting: a complicated portfolio, limited liquidity for shareholders, and a valuation that told investors the market didn’t believe the story.

The specific behind-the-scenes details of Barington’s involvement with InvenTrust aren’t fully disclosed in public records. But the thrust of the activist thesis was clear and, frankly, hard to argue with: the portfolio was unfocused, management wasn’t creating value, and the company needed to choose—either fix itself fast, or sell to someone who could.

What followed was less a tweak and more a rewrite.

InvenTrust committed to a single identity: grocery-anchored shopping centers. That meant selling non-core assets and tightening the map. The goal wasn’t just “Sun Belt sounds nice.” It was to exit secondary and tertiary markets and concentrate in higher-growth metros where population gains and rising incomes could translate into stronger rents and steadier leasing demand. Over time, the footprint shrank dramatically—from roughly 40 markets down to about 15—making the portfolio simpler to run and easier to defend.

The upgrade wasn’t only geographic. It was also about who pulled shoppers into the parking lot.

InvenTrust went after centers anchored by what it viewed as the right grocers: Whole Foods, Trader Joe’s, Sprouts, Publix, Wegmans, and strong regional chains. The logic was that these brands had loyal customers, the willingness to reinvest in stores, and positioning that was less exposed to the fiercest price competition from Walmart and Amazon.

Management framed the bet in plain terms. InvenTrust focused on Sun Belt markets with high job and income growth, and emphasized that a large portion of its retail assets were anchored or shadow-anchored by grocers—tenants viewed as more resistant to internet competition. The portfolio showed signs of stability, including occupancy in the low 90s and rent growth on renewing leases.

Then came the balance-sheet side of the turnaround: capital recycling. Selling properties created proceeds, but InvenTrust didn’t try to immediately turn around and buy its way into growth—hard to do when bigger, public peers have a lower cost of capital. Instead, it leaned into deleveraging and strengthening credit metrics, the unglamorous work that makes everything else possible later.

And because shareholder frustration wasn’t theoretical—many investors simply wanted an exit—InvenTrust also made a direct move to create liquidity. In 2018, the company ran a Dutch auction tender offer and accepted for purchase 46,421,060 shares at $2.10 per share, for a total of approximately $97.5 million. The shares it bought represented about 6% of the company’s outstanding common stock as of August 1, 2018, and 38% of all shares tendered. CEO Thomas McGuinness said the offer was meant to balance the long-term strategy with the needs of stockholders seeking liquidity, and pointed to the portfolio transformation underway over the prior 18 months.

The tender offer was a telling signal. InvenTrust was effectively saying: we know liquidity has been a problem, and we’re willing to use capital to relieve pressure—while still staying on the path of becoming a higher-quality, grocery-anchored REIT. The $2.10 price also threaded a needle: it gave sellers a defined exit, reduced the share count for those who stayed, and tried to land in a range that could be defended to both groups.

By June 30, 2018, InvenTrust owned and managed 78 retail properties totaling 13.9 million square feet.

More important than the count was what the company had become. The 2016–2018 period was the most consequential stretch of InvenTrust’s post-crisis life: a hard pivot to grocery-anchored retail, a tighter Sun Belt-heavy footprint, and a stronger financial posture. After years of operating in an awkward in-between, InvenTrust finally had something it hadn’t had since before the crisis—an identity, and a plan.

VII. The Retail Apocalypse Test (2017–2020)

By the late 2010s, retail real estate was living under a cloud. The phrase “retail apocalypse” wasn’t just clickbait—it was the dominant narrative as e-commerce kept taking share and once-household-name chains started collapsing.

Then came COVID-19, and the story got darker overnight. Lockdowns triggered nationwide store closures and turned a slow-motion disruption into a sudden shock. Bankruptcies and near-bankruptcies piled up: J. C. Penney, J.Crew, and Nordstrom, among others. Lord & Taylor—America’s oldest department store—headed toward liquidation, just six years shy of its 200th birthday. Other chains, including Dave & Buster’s, H&M, Party City, and Gap, told landlords the same thing in blunt terms: rent checks weren’t coming.

For shopping center REITs, it was both danger and opportunity.

The danger was straightforward. Bankrupt tenants meant lost rent. Store closures meant dark space. And the broad-brush assumption that “all retail is dying” crushed valuations across the entire sector. In the depths of the pandemic, shopping center REITs reported their worst same-store NOI performance on record in the second quarter, as landlords struggled to collect rent from non-essential tenants. Dividends fell too: most shopping center REITs cut or eliminated payouts after COVID began, with Federal Realty standing out as a rare exception that kept its multi-decade streak alive.

But the opportunity came from a simple truth the market was slow to price in: not all retail is created equal. Grocery, pharmacies, discount retailers, and service businesses weren’t just surviving—they were busy. The landlords who owned the right centers could replace failing categories with growing ones.

That’s where grocery-anchored centers quietly separated from the pack. Essential businesses that kept the lights on—grocery stores and pharmacies most of all—didn’t just stay open. In many cases, they thrived. And investors in grocery-anchored portfolios were insulated from some of the rent collection chaos hitting other corners of retail.

For InvenTrust, timing mattered. The company had largely finished its portfolio transformation before the apocalypse hit hardest. It had already sold weaker properties and exited struggling markets. What remained was a tighter collection of grocery-anchored centers in higher-growth geographies—exactly the kind of real estate that could bend without breaking.

InvenTrust also leaned into a practical leasing playbook: if shaky retailers were going to disappear, the replacement tenants needed to be the kind that can’t be shipped in a box. Fitness, medical, dental, beauty services, restaurants, and pet services all fit the bill. These businesses wanted to sit next to grocery traffic, and they weren’t going to be disrupted by Amazon. A physical therapy clinic can’t be delivered via Prime.

By late summer 2020, rent collection across the shopping center space had improved to over 80% in August, and the longer-term picture for open-air, grocery-anchored centers looked materially better than for enclosed regional malls. Even after the panic, leasing spreads for higher-quality grocery-anchored portfolios remained positive—a sign that tenants still wanted this real estate.

The deeper insight, though, was even more important: grocery-anchored centers weren’t only competing with e-commerce. In a lot of ways, they were enabling it.

Click-and-collect made the store a pickup point. Delivery services used stores as fulfillment hubs. The “physical” grocery box became part of the omnichannel system. And when COVID pulled forward years of e-commerce adoption in a matter of months, grocers with real omnichannel capabilities were best positioned to adapt. Even then, much of grocery e-commerce still flowed through stores—not warehouses—because the infrastructure was already there, and the stores were already close to the customer.

In other words, the thing that was supposed to kill retail ended up reinforcing the value of the best grocery-anchored locations.

VIII. COVID & The Grocery Thesis Vindicated (2020–2021)

When COVID-19 forced governments to shut down non-essential businesses in March 2020, grocery stores were explicitly exempt. They were deemed essential—and overnight, grocery-anchored landlords weren’t just “owning retail.” They were owning critical neighborhood infrastructure.

That designation mattered in the only way that counts in a crisis: the doors stayed open, and rent collections stayed comparatively strong. While huge swaths of retail went dark, most grocery stores and other essential operators kept operating from day one of the pandemic.

The contrast with other retail formats was brutal. Across the shopping center REIT universe, rent collections cratered in the early months—down to about 46% of typical rent in April. Even that ugly number looked “good” next to malls, where collections were widely understood to be far worse. Free-standing retail held up somewhat better than shopping centers. And within shopping centers, the ones with grocery and drug tenants tended to be the stabilizers—because essential traffic didn’t vanish.

So yes, 46% was a gut punch. But it also proved the point: in a moment when discretionary retail broke, necessity retail bent and started recovering.

That’s why, even early in the pandemic, the market started talking about a flight to quality. In a world that suddenly felt unpredictable, investors weren’t looking for the cleverest story. They were looking for the assets that could keep throwing off cash: data centers, self-storage, and, crucially, grocery-anchored shopping centers.

For InvenTrust, COVID didn’t create a new strategy—it stress-tested the one it had already chosen. A grocery-anchored, Sun Belt-heavy portfolio held up the way it was supposed to. Anchor tenants largely kept paying. Essential small-shop categories like pharmacies and medical offices stayed open. Quick-service restaurants with drive-throughs proved far more resilient than sit-down concepts. Non-essential tenants still struggled, but they were a smaller slice of the pie than they would’ve been in a less focused portfolio.

As the country moved from lockdowns into reopenings, the trend line improved. By mid-2020, rent collections in shopping center and free-standing retail REITs were showing meaningful month-over-month gains as more of the economy turned back on.

COVID also accelerated something that had been building for years: a widening gap between great retail real estate and everything else. Quality, well-located assets with essential tenants became more valuable relative to the weak stuff. Capital that had frozen during the panic came back looking for the safest bets—and there weren’t many of them. With little new product coming to market, demand for anchored and shadow-anchored multi-tenant retail properties increased, and pricing for high-quality assets tightened, in some cases pushing cap rates below pre-COVID levels.

InvenTrust came out of this period with a rare combination in retail real estate: a portfolio the market now clearly understood, and a thesis that had just been validated under the harshest conditions imaginable. And that set up the next chapter—the one shareholders had been waiting for since the original non-traded REIT days: a public listing, and real liquidity at last.

IX. The NYSE Listing: Emergence into Public Markets (2021)

On an October morning in 2021, InvenTrust finally did the thing its shareholders had been waiting on for years: it stepped into the daylight.

The company announced that its common stock had been listed and would begin trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker IVT at the market open. Daniel “DJ” Busch, now President and CEO, framed it as both a celebration and a handoff to a new audience. The board, management, and employees were marking the moment, he said, and he was excited to bring a platform of premier Sun Belt, grocery-anchored assets into the public markets.

But the listing wasn’t just symbolic. It was practical. InvenTrust emphasized that a direct listing would provide immediate liquidity in what it viewed as the most efficient way for existing shareholders to finally have a real market for their shares. After seventeen years living in the non-traded REIT world—through the financial crisis, years of drift, a forced strategic pivot, and then a pandemic stress test—there was, at last, a ticker.

By June 30, 2021, InvenTrust owned and managed 65 retail properties representing 10.8 million square feet of space. It also highlighted a commitment to environmental, social, and governance practices, noting that it had been a GRESB member since 2018.

The listing was also the capstone to a leadership transition that helped set the tone for the next era. CEO Thomas McGuinness announced his retirement, and the board approved a succession plan that elevated Busch to President on February 22, 2021, with the expectation that he would succeed McGuinness as CEO upon McGuinness’s retirement on August 6, 2021.

Busch brought an unusual résumé for a REIT chief executive. Most REIT CEOs come up through the operator track—leasing, property operations, development, acquisitions. Busch came from the investor side. Before joining InvenTrust, he was Managing Director, Retail at Green Street Advisors, where he provided independent research on shopping center, regional mall, and net lease REITs. Earlier, he covered the mall sector at Green Street, building models, analyzing financial statements, and explaining to investors why one portfolio deserved capital and another didn’t.

That perspective mattered because InvenTrust’s next chapter depended on public markets not just understanding the portfolio, but believing the story. As board member Ms. Saban put it, Busch brought deep public market knowledge and extensive retail real estate experience to the President and CEO roles.

Alongside the listing and leadership change, the company reiterated another message aimed straight at income-focused REIT investors: it intended to increase the dividend by 5%, starting with the fourth quarter 2021 distribution to be paid in January 2022.

X. The Modern Playbook: Current Operations & Recent Developments (2021–Present)

With a ticker symbol and real liquidity at last, InvenTrust entered a different kind of test: could it operate like the focused, public-market REIT its story had been building toward? Since the NYSE listing, the answer has been yes—by sticking to a simple formula: buy selectively in the Sun Belt, sell what doesn’t fit, and keep squeezing more performance out of the portfolio it already owns.

In 2024, that playbook showed up in the transaction tape. InvenTrust acquired seven retail properties—including The Plant in Phoenix, Arizona, and Stonehenge Village in Richmond, Virginia—for a total gross acquisition price of $282.1 million. It also sold one retail property and an outparcel adjacent to an existing retail property for an aggregate gross disposition price of $68.6 million. Operationally, it stayed busy: 210 leases were signed across 1.32 million square feet, and the company posted a retention rate of about 94%.

The operating engine did what public REIT investors want it to do: grow same-property income through occupancy, rent, and smarter leasing. Same Property NOI increased by $7.7 million, or 5.0%, driven primarily by higher occupancy, higher ABR per square foot, favorable lease spreads, and leases with advantageous fixed recovery terms.

For the full year, same-property NOI reached $162.6 million, up 5% from 2023—marking the fourth consecutive year with same-property NOI growth above 4%. Management said the year-over-year lift was primarily driven by base rent growth, including embedded rent bumps already written into leases.

“InvenTrust’s strong fourth-quarter and full-year performance reflects our continued focus on operational excellence and strategic growth,” said DJ Busch. “Our impressive Same Property NOI growth, all-time high leased occupancy, and solid leasing spreads underscore the quality of our portfolio and our ability to drive long-term value. We believe our disciplined acquisition approach in key Sun Belt markets positions us for sustained success in 2025 and beyond.”

By December 31, 2024, the portfolio was very close to full. Leased occupancy stood at 97.4%. Anchor leased occupancy—spaces 10,000 square feet or larger—was 99.8%, while small shop leased occupancy was 93.3%. Anchor leased occupancy held at an all-time high, and small shop occupancy improved sequentially. There was also a 210-basis-point gap between leased and economic occupancy, representing about $6.3 million of annualized base rent—essentially, a pocket of occupancy that was leased but not yet fully paying, a built-in runway as tenants open and rent commences.

In 2025, the capital allocation story tilted hard toward geographic repositioning. On June 6, 2025, InvenTrust completed the sale of five properties in California for a gross disposition price of $306.0 million, recognizing a gain on sale of $90.9 million. In the second quarter, it also completed four acquisitions, including Plaza Escondida in Tucson, Arizona, anchored by Trader Joe’s.

Management has described the 2025 California sales as capital recycling: monetizing assets where valuations are attractive and redeploying the proceeds into markets it’s more excited about. The strategic logic is straightforward. California properties can fetch premium pricing, but the state brings headwinds—higher taxes, regulatory complexity, and slower population growth. Selling there and reinvesting into faster-growing Sun Belt markets like Texas, Florida, Arizona, and the Southeast is meant to create value through geographic arbitrage.

The balance sheet, meanwhile, reads like a company that remembers the 2008 playbook a little too well—in the best way. As of June 30, 2025, InvenTrust had $787.1 million of total liquidity, including $287.1 million of cash and cash equivalents and $500.0 million of availability under its revolving credit facility. It had $22.9 million of mortgage debt maturing in 2025 and $200.0 million of term loan debt maturing in 2026.

And rather than letting maturities creep closer, the company pushed them out. InvenTrust recast $400 million of unsecured term loans into two pieces—Tranche A-1 (maturing August 2030) and Tranche A-2 (maturing February 2031)—which extended weighted average maturity from 2.9 years to 5.1 years. In plain English: fewer near-term refinancing headaches, and a capital structure better matched to long-lived real estate, especially valuable in a rate environment that can turn on a dime.

XI. Strategic Frameworks: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

To understand where InvenTrust can win—and where it’s structurally disadvantaged—you have to zoom out from individual properties and look at the forces shaping the grocery-anchored shopping center game.

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: Low to Medium

At first glance, this is just “buy some shopping centers.” In reality, the barriers are real. The best corners in the best neighborhoods are already taken, and new retail development is often throttled by zoning, entitlement timelines, and local resistance. Building a meaningful portfolio also takes enormous capital.

That said, “low” doesn’t mean “zero.” Private equity and private REITs show up in the same acquisition processes, and older centers can sometimes be repositioned and re-anchored by a grocery tenant. So the threat isn’t that a brand-new InvenTrust pops up overnight; it’s that well-funded capital can still compete for the same scarce assets.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Medium

In real estate, suppliers are the people who build and fix things: contractors, labor, and, indirectly, land. Construction costs have climbed, and skilled labor can be tight—especially in high-growth markets.

The good news for InvenTrust is that it mostly operates as an owner and operator of existing centers, not a ground-up developer. That lowers direct exposure to the worst of construction-cost inflation. Still, any redevelopment, tenant build-out, or improvement project ultimately runs through the same supply chain, and that keeps supplier power in the “medium” bucket.

Bargaining Power of Buyers/Tenants: Medium-High

The anchor tenants have leverage, and everyone knows it. Big grocers like Kroger, Albertsons, Whole Foods (Amazon), and Publix aren’t just renting space—they’re the traffic engine for the entire center. Because they’re so valuable to the ecosystem, they can negotiate hard on rent, terms, and renewal options.

But it’s not a one-way street. The highest-quality grocery sites aren’t interchangeable. Grocers need specific demographics, visibility, access, and trade areas to justify a store. When a location works, it’s hard to replace.

Small-shop tenants have much less negotiating power. Most of them want one thing: to be next to the grocery traffic. And that makes them far more price-takers than price-setters.

Threat of Substitutes: Medium-High

E-commerce is still the gravitational force pulling on retail—especially the non-grocery categories that often fill in the rest of a shopping center. Service tenants like medical, fitness, and beauty are relatively insulated, but categories like apparel and home goods will keep feeling pressure.

Even grocery has substitutes at the margin: delivery services and delivery-only “dark stores” can, in theory, reduce the need for customers to visit a physical store. The counterweight is economics. Grocery delivery is notoriously hard to make profitable, and fresh food still favors physical stores. That’s why the threat is real, but not existential.

Competitive Rivalry: High

This is a knife fight for the best assets, and InvenTrust is up against bigger players.

Regency Centers and Kimco are both far larger, better-capitalized public REITs, and they’ve built their businesses around the same general truth: grocery-anchored centers are some of the most durable retail real estate in America. Brixmor is another major competitor in the shopping center REIT tier.

That scale gap matters. InvenTrust, at roughly a $2.3 billion market cap, is meaningfully smaller than peers like Regency (about $12.5 billion), Kimco (about $14.4 billion), and Brixmor (about $8 billion). In practice, that can translate into a higher cost of capital, less research coverage, and a tougher time winning competitive acquisition processes—especially when pricing gets aggressive.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis:

-

Scale Economies: Limited - InvenTrust doesn’t have the same scale advantages as the giants. Bigger REITs can spread overhead across larger portfolios and usually access capital more efficiently.

-

Network Effects: None - This is real estate: local by nature. Owning a center in Phoenix doesn’t make a center in Atlanta inherently more valuable. There’s no network flywheel here.

-

Counter-Positioning: Not Applicable - InvenTrust isn’t running a disruptive model. The playbook—Sun Belt, grocery-anchored, upgrade the tenant mix—is something competitors can pursue too.

-

Switching Costs: Moderate - Retail tenants don’t move lightly. Build-out costs, permitting, downtime, and customer habits create real friction. Grocery anchors are especially sticky because shoppers build routines around the store they know.

-

Branding: Weak - Consumers don’t shop “at InvenTrust.” They shop at Publix, Trader Joe’s, and Whole Foods. The brand equity lives with the tenants, not the landlord.

-

Cornered Resource: THIS IS THEIR PRIMARY POWER - The core advantage is owning irreplaceable real estate: grocery-anchored centers on strong corners in prime Sun Belt markets. You can’t replicate the same intersection. You can’t recreate a fully built, well-leased center in a mature trade area overnight. And you often can’t buy an equivalent portfolio at an attractive price because so few owners are willing sellers. Since becoming public, InvenTrust has kept refining the portfolio around exactly this idea.

-

Process Power: Developing - InvenTrust is building operational muscle in leasing, tenant mix, and market selection. It’s valuable, but not yet so unique that it stands alone as a moat.

Primary Moat: Cornered Resource (irreplaceable quality locations) combined with moderate Switching Costs (tenant stickiness).

XII. Business Model Deep Dive & Competitive Positioning

At its core, InvenTrust is running a simple machine: own high-quality, grocery-anchored shopping centers, lease them to tenants, collect rent, and pass most of that cash flow back to shareholders.

The simplicity, though, hides a carefully balanced revenue stack. The anchors—usually grocery stores—are the stabilizers. They tend to sign long leases, often in the 10- to 20-year range, and those leases commonly include contractual rent escalations. That’s the predictable foundation.

The small shops are where the upside lives. Restaurants, service providers, and medical users generally pay much higher rent per square foot, but they sign shorter leases. That means faster repricing power in good markets, and more leasing work—and more volatility—when conditions soften.

You can see that mix in the company’s rent economics. As of June 30, 2025, Annualized Base Rent per square foot was $20.18, up 2.4% from the same period in 2024. In the second quarter, Anchor Tenant ABR per square foot was $12.73, while Small Shop Tenant ABR per square foot was $33.04.

That spread tells you why the grocery-anchored model works. The grocer doesn’t pay the highest rent, but it pays reliably and drives traffic. The small shops pay the premium, but they’re renting the benefit of that traffic. Get the mix right, and you get both stability and growth. Get it wrong, and you either own a stable but under-earning property, or a high-rent strip that’s fragile when foot traffic weakens.

Lease structure helps, too. Many shopping center leases are designed to push expenses through to tenants—property taxes, insurance, and common area maintenance—so rising costs don’t automatically crush the landlord’s margins. Some leases also include percentage rent, which gives the landlord a cut when tenant sales clear certain thresholds. It’s not the core of the model, but when it shows up, it’s a way to participate in tenant outperformance.

When it comes to what InvenTrust does with its cash, the priorities are familiar—and intentionally conservative: - Acquisitions: adding properties in target markets when pricing and quality line up - Development and redevelopment: selective, opportunistic improvements rather than a constant ground-up pipeline - Debt management: keeping leverage in check and pushing maturities out - Dividends: returning cash flow to shareholders

That last point is the heartbeat of REIT investing. For the quarter ending December 31, 2024, the board declared a quarterly cash distribution of $0.2263 per share. It also approved a 5% increase to the company’s cash dividend, bringing the new annual rate to $0.9508, reflected starting with the next quarterly dividend.

The big competitive constraint hasn’t changed: scale. Bigger, better-capitalized shopping center REITs can often raise money more cheaply, attract more analyst coverage, and win the most competitive acquisition processes. As one industry view put it, well-capitalized REITs are taking share, and retail demand is growing as brick-and-mortar stores increasingly serve as last-mile distribution nodes. In that same context, Regency Centers is often cited for having some of the strongest demographics among its peers, with a grocery-heavy portfolio that can provide downside protection in a choppy macro environment.

InvenTrust sits a tier below those giants. Its smaller size can translate into a higher cost of capital, less attention from the Street, and fewer shots at the biggest portfolio deals. The company’s response has been to stay disciplined: focus on underwriting, and pursue smaller acquisitions where competition can be less intense and where it can be selective about fit.

That’s the interesting tension in what you might call a “subscale premium REIT.” InvenTrust has built a portfolio that looks like the kind of thing the public markets reward—high-quality, grocery-anchored, Sun Belt-weighted—but it doesn’t have the heft of the largest peers. That can cut two ways: it could remain an independent compounder over time, or it could be a natural acquisition target for a bigger REIT that wants instant exposure to the exact markets InvenTrust has been building around.

XIII. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case:

InvenTrust can look like a “quiet compounder” in the grocery-anchored REIT world, and the case for it rests on a handful of reinforcing strengths.

Portfolio Quality: The company owns 68 properties concentrated in growing Sun Belt markets, and it’s deliberately leaning further into that identity—expanding the retail portfolio by acquiring grocery-anchored neighborhood and community centers in places with favorable demographics. The bet is that population migration, income growth, and limited new supply keep these centers occupied and keep rents moving over time.

Operational Excellence: Four consecutive years of same-property NOI growth above 4% isn’t a one-off; it suggests a repeatable operating rhythm. High occupancy and positive leasing spreads are the visible proof that tenants still want to be in these centers, and that InvenTrust can convert that demand into higher cash flow.

Balance Sheet Strength: After nearly blowing up in the financial crisis, the company has leaned hard into balance sheet conservatism. It has extended debt maturities and maintained substantial liquidity. A concrete example: recasting $400 million of unsecured term loans pushed weighted average maturity from 2.9 to 5.1 years, reducing near-term refinancing pressure.

Thesis Validation: COVID-19 didn’t create the grocery-anchored thesis, but it did validate it under maximum stress. Essential retail stayed open, traffic held up better than almost anyone expected, and the model proved it could take a punch.

M&A Optionality: At roughly a $2.3 billion market cap, InvenTrust is small enough that it could plausibly be acquired by a larger REIT that wants more Sun Belt, grocery-anchored exposure without having to assemble it one property at a time.

Dividend Growth: Management has signaled an intention to grow the dividend, including a 5% increase announced for 2025—a reminder that this is still, at its core, a cash-flow-and-distribution story.

The Bear Case:

The flip side is that “high quality” doesn’t make the business immune to the category’s structural risks—and InvenTrust has a few worth taking seriously.

Scale Disadvantage: InvenTrust is meaningfully smaller than major peers like Regency, Kimco, and Brixmor. In a sector where cost of capital and access to deals matter, size can translate into advantages InvenTrust simply doesn’t have: cheaper financing, greater acquisition competitiveness, and more consistent research coverage.

Grocer Margin Pressure: Grocery is famously low margin, and competition from Walmart, Amazon, Aldi, and others is relentless. If anchors feel pressure, they may push for rent concessions, shrink footprints, or close underperforming locations—none of which is great for a center that relies on the anchor as the traffic engine.

Interest Rate Sensitivity: Even with maturities extended, higher interest rates can pressure real estate values and make it harder to buy properties in a way that’s accretive to shareholders.

Recession Risk: The small shops—restaurants and service tenants—are often the higher-rent component of the model, but they’re also the tenants most exposed in a downturn. If consumer spending weakens, that part of the rent roll can get shaky.

E-commerce Persistence: Grocery has been more resilient than other retail categories, but online grocery delivery keeps growing. If dark stores and micro-fulfillment models keep improving, they could chip away at physical-store economics over time.

Climate Risk: A Sun Belt focus comes with long-term environmental and insurance realities: heat, water scarcity, and rising insurance costs could become meaningful headwinds for certain markets and properties.

Execution Risk: The capital recycling strategy—selling properties in one region (like California) and buying in others—can create value, but it’s not automatic. Timing, pricing, and deal execution matter, and property transactions can be unpredictable.

XIV. Key Metrics to Track

If you want a quick read on whether InvenTrust’s strategy is still working, there are two numbers that cut through almost everything else.

1. Same-Property NOI Growth

This is the clearest window into the health of the portfolio itself, because it strips out the noise of buying and selling buildings. Same-property NOI looks only at properties owned over a consistent period and asks a simple question: is the real estate you already own generating more cash than it did last year?

That growth can come from higher occupancy, higher rents, and better lease terms—or get eaten up by rising expenses. In InvenTrust’s case, Same Property NOI increased by $7.7 million, or 5.0%, driven primarily by increased occupancy, higher ABR per square foot, favorable lease spreads, and leases with advantageous fixed recovery terms.

The bigger signal is consistency. InvenTrust has now delivered four consecutive years of same-property NOI growth above 4%. If that run continues, it’s evidence the “high-quality, grocery-anchored, Sun Belt” thesis is still compounding. If it slows, you’ll want to know why.

2. Leasing Spreads

Leasing spreads tell you whether the landlord has pricing power when leases roll. They measure the gap between the rent on an expiring lease and the rent on the new or renewal lease. Positive spreads mean market rents are moving up and tenants still want this space. Negative spreads are a warning sign that demand is softening or that tenants have regained leverage.

InvenTrust executed 59 leases totaling approximately 469,000 square feet of GLA, with about 403,000 square feet signed at a blended comparable lease spread of 9.8%.

It’s also worth watching where the strength is coming from. Anchors tend to be steadier and lower-rent; small shops are the higher-rent, higher-volatility upside. Strong small-shop spreads are a great sign. Weakening spreads—especially if they start showing up across both anchors and small shops—can be an early indicator that conditions are cooling.

XV. Lessons & Takeaways: The Playbook

InvenTrust’s journey leaves behind a playbook that’s useful far beyond retail real estate.

Survival Matters More Than Optimization

In the early years, the company did a lot of what looks obvious in hindsight: buying near the top, building a sprawling, hard-to-manage portfolio, and leaning too hard on debt. Then 2008 hit, and “best practices” stopped mattering. Liquidity did. So did lender relationships. In a true crisis, the job isn’t to maximize returns—it’s to stay alive long enough to have a second act.

Focus Creates Value

The biggest upgrade wasn’t a single acquisition or a clever financial maneuver. It was choosing what the company actually was. A mix of hotels, student housing, and retail is hard for investors to understand, and even harder to value. A focused, grocery-anchored REIT concentrated in Sun Belt markets is a story the market can underwrite—and, crucially, compare to peers.

Activists Can Be Catalysts

InvenTrust didn’t snap into clarity on its own timetable. External pressure helped force the issue. Whether it was Barington or other shareholders pushing from the sidelines, the demand for sharper strategy and portfolio rationalization accelerated changes management had been slow to make. Activists don’t always create value, but in situations defined by drift, they can.

Quality Locations Are Durable Moats

The most defensible advantage in shopping centers isn’t branding or technology. It’s the corner. Great grocery-anchored centers in growing markets are hard to replicate because the land is already spoken for, the zoning is already won, and the customer routines are already formed. Once you own that kind of location, it tends to stay valuable—because there just aren’t many substitutes.

Timing and Luck Matter

InvenTrust finished much of its cleanup before COVID arrived. That mattered. If the pandemic had hit earlier—when the portfolio was messier and the balance sheet weaker—the story could’ve ended differently. Execution put the company in position, but timing determined how big the payoff would be.

Capital Structure Is Destiny

REITs can’t fake their way through a downturn. Too much leverage turns a bad year into an existential threat. A fortress balance sheet turns the same environment into something survivable. InvenTrust’s focus on deleveraging and extending maturities wasn’t flashy, but it was foundational—and it’s a direct response to what nearly broke the company before.

The Grocery Thesis Was Right

The bet on necessity retail—grocery anchors, essential services, and tenants that can’t be replaced by a cardboard box on a doorstep—ended up being the right hill to defend. And it wasn’t a consensus view at the time. The dominant narrative was that retail was dying. Being early and correct on what would prove resilient didn’t just protect the business; it created the conditions for real value creation.

XVI. Epilogue & Future Outlook

InvenTrust entered 2026 as a completely different company from the sprawling, anything-goes real estate empire it had become in the mid-2000s. Back in 2009, it reported a footprint that reads like a conglomerate checklist: hundreds of retail properties, a portfolio of hotels, plus office, industrial, and multifamily scattered across the country. Today, that sprawl has been distilled into 68 grocery-anchored shopping centers with a clear identity and a tighter geographic focus.

Looking ahead through 2025 and beyond, management has signaled confidence in the playbook: keep buying what fits, keep selling what doesn’t, and keep driving performance through leasing, occupancy, and disciplined operations—using the platform it has already built rather than reinventing the business again.

The open question isn’t whether InvenTrust has a strategy now. It does. The question is how the next set of forces shapes the outcome.

Scale and Independence: Does InvenTrust stay independent, or does it eventually become an acquisition target? At roughly a $2.3 billion market cap, it’s big enough to matter and small enough to be bought. A premium, grocery-anchored, Sun Belt-weighted portfolio is exactly the kind of thing a larger peer could want more of—without having to assemble it one center at a time.

Geographic Focus: The California dispositions point to continued capital recycling into markets management believes have better growth and fewer headwinds. The real test will be what comes next: where does InvenTrust find the next great assets, and can it buy them at prices that still create value for shareholders?

Grocery Evolution: Grocery is essential, but it isn’t static. Online ordering, delivery, dark stores, and shifting consumer habits keep changing what a “successful” grocer looks like. The health of the anchors still matters enormously, because they remain the traffic engine. How those tenants adapt will ripple through everything from leasing demand to long-term property values.

Climate and Sustainability: A Sun Belt concentration comes with trade-offs. Insurance costs have been rising, especially in Florida, and water scarcity looms in parts of the Southwest. Those pressures can show up quietly—higher operating costs here, tougher underwriting there—until they don’t feel quiet anymore.

Interest Rates and Valuations: REITs live and die by the cost of capital. The rate environment will shape acquisition economics and public-market valuations, and it will influence how attractive capital recycling really is. Navigating that uncertainty well may matter as much as any single leasing year.

From near-death in 2009 to vindication in 2020, InvenTrust’s arc is a reminder that corporate transformation is possible—but rarely quick, and never painless. It takes crisis, pressure, discipline, and years of execution that often looks unglamorous in the moment.

The grocery thesis has held. The balance sheet has been reinforced. The portfolio is high quality and increasingly understood by the market. What’s left is the hard part every “subscale premium” platform has to answer: can InvenTrust turn those strengths into sustained shareholder value on its own, or does it ultimately become part of someone else’s growth story?

Either way, the journey—from a sprawling conglomerate to a focused, grocery-anchored Sun Belt REIT—is one of the more dramatic reinventions in modern REIT history. It started as a survival story. It became a vindication story. The next chapter will decide what it turns into after that.

XVII. Further Reading & Resources

Key References:

- InvenTrust Properties investor presentations and SEC filings (10-K, 10-Q, 8-K) on SEC.gov

- Nareit research on REITs, with coverage of shopping centers and grocery-anchored industry trends

- Regency Centers, Kimco Realty, and Brixmor Property Group investor materials for peer comparison

- Green Street Advisors research on the retail REIT sector

- CoStar market data and commentary on Sun Belt retail real estate trends

- Urban Land Institute (ULI) publications on mixed-use development and retail’s evolution

- Inland Group historical materials and background on the non-traded REIT era

- Academic research on REIT performance and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Industry analysis of the “retail apocalypse” and its impact on commercial real estate

- Demographic research on Sun Belt population migration patterns and local growth dynamics

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music