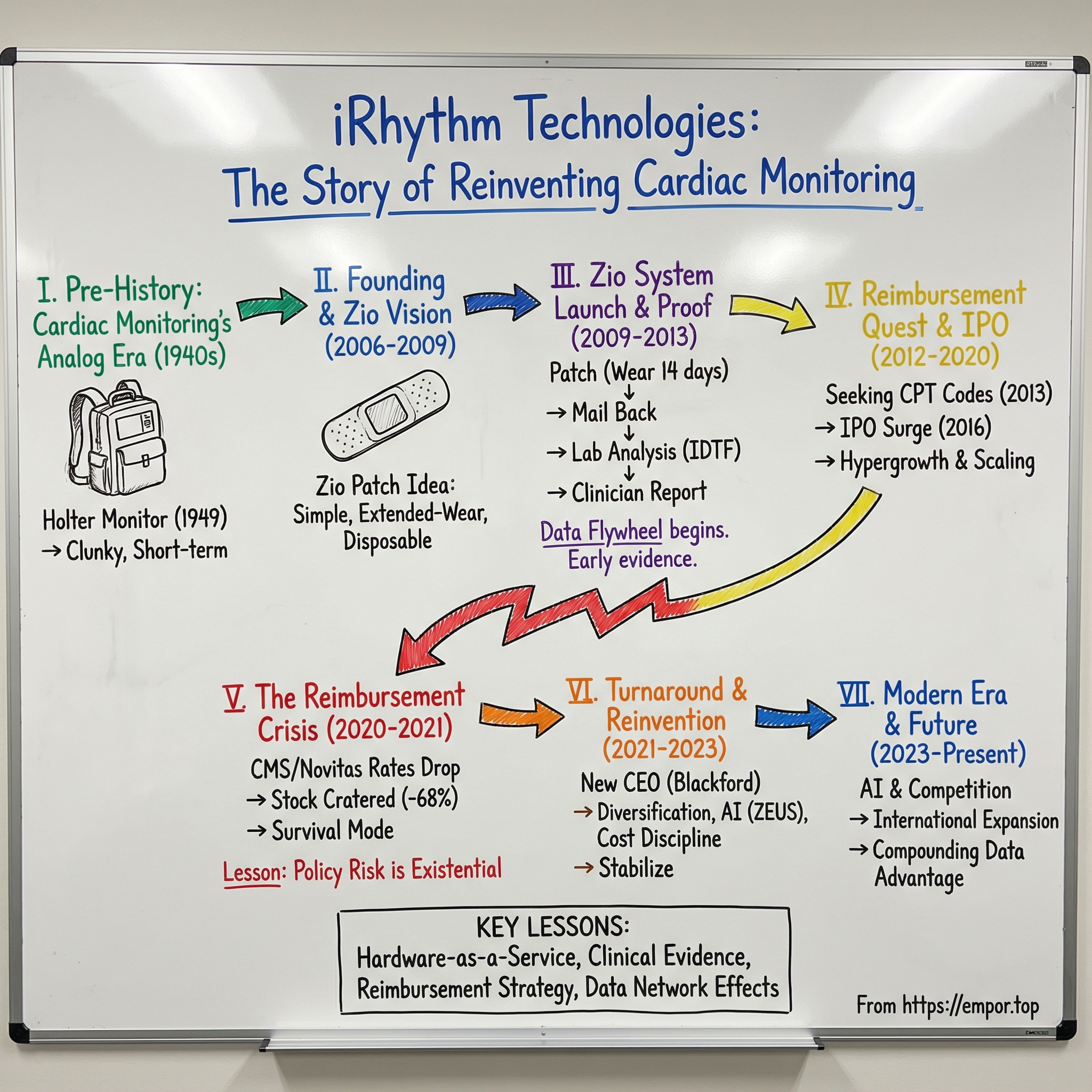

iRhythm Technologies: The Story of Reinventing Cardiac Monitoring

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a cardiologist in 2005 trying to explain cardiac monitoring to a patient with intermittent palpitations. To catch the problem, she’d need to wear a clunky box strapped to her chest, keep the electrodes in place, skip showers, and hope her symptoms showed up during a one- or two-day window. If they didn’t—and most transient arrhythmias didn’t—then she’d come back and do it all over again. For decades, the “gold standard” of catching dangerous heart rhythms was basically a game of timing.

iRhythm Technologies changed that. With its Zio platform, the company helped turn cardiac monitoring from a short, inconvenient snapshot into something closer to “wear it and forget it.” What began as a Band-Aid-sized patch idea coming out of Stanford became a major force in ambulatory cardiac monitoring, with more than 2 million patients served each year and over 30% share of the core market.

But the part that makes iRhythm’s story worth telling isn’t just the invention. It’s the near-death experience.

In early 2021, iRhythm’s stock cratered—down more than 68% from its January peak—not because a competitor beat them, or because the technology stopped working, but because Medicare reimbursement rules shifted underneath them. The company that had rebuilt the front end of cardiac diagnostics almost got taken out by the back end: pricing, codes, and the byzantine machinery of American healthcare economics.

Today, iRhythm has been working toward its first free cash flow positive year in 2025, while pitching an even larger vision: expanding its total addressable market to 27 million patients. So how did a Silicon Valley startup disrupt a 100-year-old diagnostic category, get blindsided by policy, and then fight its way back?

That’s what this story unpacks: the long, weird evolution from Norman Holter’s backpack-sized monitor in the 1940s, to iRhythm’s founding in 2006, to the IPO surge, the reimbursement crisis that nearly killed the business, and the reinvention that put it back on a growth trajectory. Along the way, the real lesson emerges: in healthcare, the breakthrough isn’t just building a better product. It’s surviving the system that decides whether the product gets paid for.

II. The Pre-History: Cardiac Monitoring's Analog Era

Norman Jefferis “Jeff” Holter was an American biophysicist who gave his name to the Holter monitor: a portable device that could continuously record the heart’s electrical activity for a day or more. The only catch was that “portable” in 1949 meant something very different than it does now. Holter and his colleague Gengerelli pulled off an early proof of concept by broadcasting an electrocardiogram from an 85-pound backpack transmitter while the subject exercised. Ambulatory cardiac monitoring was born with nearly 40 kilograms of vacuum tubes, batteries, and recording gear strapped to someone’s back.

Holter himself didn’t look like the typical medical innovator. Born in Helena, Montana, he trained as a physicist and chemist—Carroll College, then UCLA, then the University of Southern California. That outsider background turned out to be a feature, not a bug. He didn’t treat the heart as a mysterious organ to be observed in brief clinic visits. He treated it like an electrical system you could measure continuously, out in the real world where problems actually happen.

His argument for continuous monitoring became famous because it was so simple. Collecting heart data, he said, is like assaying ore: a mining engineer doesn’t test one rock and declare the whole mountain understood. A standard ECG is a snapshot—maybe 30 seconds. But the rhythms that cause fainting, strokes, and sudden death don’t schedule appointments. Arrhythmias come and go. Trying to catch them with a single ECG is like trying to photograph lightning by clicking once and hoping you got lucky.

The hardware improved quickly. By 1952, working with Wilford Ray Glasscock, Holter’s setup shrank dramatically—down to roughly a 1.2-kilogram amplifier and transmitter. Transistors arrived. Components got smaller and self-powered. Radio transmission gave way to magnetic tape, and later to digital memory. In 1965, Holter received U.S. Patent 3,215,136, and the Holter Research Foundation eventually sold exclusive rights to Del Mar Engineering Laboratories, which went on to dominate the category for decades.

And yet, for all the progress in size and electronics, something strange happened: the core experience barely changed.

Monitors got smaller, but the model stayed stubbornly analog. Patients still wore a wired rig with multiple chest leads. They still had to baby the device and the electrodes. Showers were a hassle. Exercise was limited. And most importantly, the monitoring window stayed short—usually 24 to 48 hours—far too narrow for the very problems clinicians were trying to catch.

By the 2000s, the market had settled into a comfortable rut. Big names like GE Healthcare, Philips, and Boston Scientific had profitable businesses selling equipment into hospitals and cardiology practices, where monitoring was also a billable service line. No one was eager to rip up the workflow. Patient inconvenience—and missed diagnoses—were treated as the cost of doing business.

But the clinical need wasn’t going away. It was getting louder.

Atrial fibrillation, the most common arrhythmia, was emerging as a public health crisis. It raises stroke risk fivefold. It affects roughly 2–3% of the population, and prevalence climbs sharply with age. And it’s a diagnostic nightmare because it often shows up in short, unpredictable bursts—or with no symptoms at all. Study after study pointed in the same direction: longer monitoring periods catch more AFib and other arrhythmias, particularly after a stroke, and extended monitoring beyond 48 hours can materially improve management.

The problem was that the existing technology wasn’t built for extended wear. Very few patients would tolerate a tangle of leads and a bulky recorder for a week, let alone longer.

So the industry needed something that wasn’t just smaller. It needed a rethink—starting from the patient experience and working backward. And that rethink would come from an unlikely place: a Stanford innovation fellowship, where a cardiac electrophysiologist started asking a deceptively simple question about why monitoring had to be so hard in the first place.

III. Founding Story & The Zio Patch Vision (2006–2009)

iRhythm’s origin story starts at Stanford, in the 2005–06 Biodesign Innovation Fellowship, where teams go hunting for real clinical problems worth solving. The need that eventually became iRhythm didn’t even look like a winner at first. It began buried in the middle of the list—something like 11th place—then steadily climbed as the team filtered for problems that were both medically important and realistically solvable.

At the center of it was Uday Kumar. He wasn’t the classic “two engineers and a pitch deck” kind of founder. Kumar was a cardiac electrophysiologist and a Consulting Associate Professor of Bioengineering at Stanford. He’d spent years treating arrhythmia patients and seeing the same failure mode over and over: the tools for diagnosing intermittent rhythm problems were uncomfortable, inconvenient, and often too short-duration to catch the event you were looking for. A 24–48 hour Holter monitor might be the standard, but it was also a gamble.

Biodesign gave the team a disciplined way to turn that clinical frustration into a product concept—define the need, map the stakeholders, test assumptions, iterate. And because Kumar lived the problem in the clinic, they could pressure-test what mattered quickly. Plenty of people in the field told them it couldn’t be done. The team kept going anyway.

In February 2006, they filed a provisional patent. Later that year, the company was formally established—incorporated in Delaware on September 14, 2006—and headquartered in San Francisco, right at the seam between medtech and Silicon Valley.

The founding insight was simple enough to fit on a sticky note: make cardiac monitoring disposable, extended-wear, and waterproof. Let patients live normally while you collect data. And instead of a one- or two-day snapshot, push monitoring out to two weeks—up to 14 days.

But there was an important constraint baked into the idea from day one: it had to work economically, not just technically. Around that time, wireless connectivity and real-time transmission were becoming the obvious “next step.” The team could have built a more advanced, always-connected device. They chose not to—because that would have driven cost up, narrowed access, and made it harder for payers to say yes. So they aimed for the opposite: simple, reliable, and scalable.

That decision—to avoid the cutting edge on purpose—ended up being a competitive advantage. The real bottleneck wasn’t the sophistication of the electronics. It was whether a human being would actually wear the thing long enough to generate useful data, and whether the system would pay for it. A patch that patients kept on for two weeks could beat a fancier device that came off after two days.

Of course, “simple” didn’t mean “easy.” The engineering list was brutal. The patch needed battery life for continuous recording over two weeks. The adhesive had to survive sweat, showers, and movement—on real chests, not lab mannequins. The memory had to store an enormous amount of data. The form factor had to disappear under a shirt. And it all had to be cheap enough to throw away after one use.

Over time, the company raised significant venture funding—$109 million across 10 rounds before its IPO—from investors including Leland Stanford Junior University and Norwest Venture Partners. The bet was that consumer-electronics-style manufacturing plus healthcare analytics could create a new kind of diagnostic category.

By the end of this phase, the Zio Patch had taken shape: a small, flexible, water-resistant adhesive patch that could continuously record heart rhythms for up to 14 days. It was designed to be straightforward enough that it didn’t have to live only in cardiology offices—it could be used in the ER or even ordered by a primary care physician.

In 2009, the Zio Patch and its associated algorithm received FDA clearance. That was the moment the project became a real commercial product. But clearance was only the opening gate. The harder challenge—the one that would define iRhythm’s next decade—was convincing the healthcare system to pay for it.

IV. The Zio System Launch & Clinical Proof Points (2009–2013)

The Zio Patch that hit the market wasn’t just a new gadget. It was a new way to deliver a diagnosis.

Yes, the hardware mattered: a small, light, low-profile patch designed to record continuously for up to 14 days. But iRhythm’s real move was wrapping that patch in an end-to-end service that made extended monitoring feel almost effortless for the patient and far more actionable for the clinician.

Here’s how it worked. A physician prescribed the patch. The patient applied it themselves—typically on the left side of the chest—and then went back to normal life. Showering, sleeping, exercise: the patch was built to stay on through all of it. When the wear period ended, the patient dropped it in the mail using a prepaid envelope. Back at iRhythm, the company’s lab downloaded the data, ran it through proprietary algorithms, and produced a clinical report for the prescribing physician.

That last step was the quiet revolution. With older setups, monitoring and interpretation were often tethered to the same place and the same workflow. Zio loosened that link. A patient could get the test initiated in a primary care office or the ER, and the data could still end up in the hands of a cardiac specialist who could decide what happened next. In other words, the test followed the patient, and expertise followed the data.

It was healthcare-as-a-service before that phrase became a cliché. iRhythm wasn’t selling a reusable device the way the legacy Holter business had for decades. It was selling a completed diagnostic episode—closer to how a lab sells a blood test than how a device company sells equipment. And that choice would shape everything: the economics, the operations, and eventually the moat.

Early evidence started to validate the model. A retrospective clinical trial completed in 2012 looked at Zio use in outpatient evaluation after an emergency department visit. Every patient returned the device for rhythm review, and the average monitoring time was more than seven days. That kind of compliance was a big deal, because traditional Holters routinely ran into real-world failure modes: wires that came loose, patients who quit early, and recordings that ended up too short to be useful.

More time on the body meant more signal captured. As studies compared Zio’s diagnostic yield to traditional 24-hour Holter monitoring, the results pointed in the same direction: extended wear uncovered arrhythmias that short snapshots missed. Patients who would have walked away with a “normal” Holter were now showing episodes of atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, and other clinically meaningful rhythms. For physicians, it wasn’t just a nicer experience. It was a different level of visibility into intermittent disease.

As the product scaled, so did the data flywheel. By late 2015, since FDA clearance and launch, iRhythm had collected and analyzed more than 90 million hours of ECG data across nearly 400,000 U.S. patients. That volume wasn’t just a bragging right—it was the raw material for better algorithms and better reports, compounding value beyond any single patch.

None of this was lightweight to run. iRhythm operated as an Independent Diagnostic Testing Facility (IDTF), which meant building the lab infrastructure, hiring and training certified cardiac technicians, putting quality systems in place, and staying compliant with a thicket of diagnostic-testing regulations. The “mail it back and we’ll send you a report” experience was simple on the surface. Underneath, it required industrial-grade execution.

Adoption, at first, followed the standard medtech pattern: win over academic medical centers and influential cardiologists, then expand outward to community practices. The audience iRhythm needed to persuade wasn’t naïve. Cardiologists could scrutinize the output and decide quickly whether the reports were actually useful. But they were also appropriately conservative. New diagnostic modalities don’t spread on hype; they spread on validation and workflow fit.

And even with FDA clearance, the earliest commercial years weren’t frictionless. Reimbursement uncertainty slowed uptake, and some physicians used the patch despite weak payment clarity—effectively absorbing cost to get the clinical benefit for their patients.

It was an early warning that would later become the central drama of the company: in healthcare, a superior product is table stakes. If the payment pathway isn’t there, the innovation doesn’t scale—and sometimes it doesn’t survive.

V. The Reimbursement Quest: CPT Codes & Business Model (2012–2016)

In healthcare, reimbursement isn’t a line item. It’s the engine. You can build a better diagnostic tool, prove it works, and even get physicians to love it—but if payers won’t cover it, the product doesn’t scale. It stalls. iRhythm learned that early, and then spent years fighting through the maze anyway.

The core issue was simple: Zio didn’t fit the boxes the system already had.

Cardiac monitoring billing ran on Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes—the standardized language doctors and labs use to get paid. There were codes for classic 24-hour Holters, codes for 48-hour monitoring, codes for event monitors. But there wasn’t a clean home for a single-piece, extended-wear patch that recorded continuously for up to 14 days, then got mailed back for analysis and a report.

So iRhythm did what new modalities usually have to do at first: it billed under “miscellaneous” or “unlisted procedure” codes. And in reimbursement land, “unlisted” is basically another way of saying “good luck.” Those claims often came back denied, delayed, or paid at lower rates. That uncertainty didn’t just create paperwork. It created friction at the point of prescription, because physicians and health systems didn’t want to hand patients a test that might turn into a billing headache.

To break through, iRhythm had to do something that doesn’t show up in glossy product demos: earn its way into the rulebook. That meant a multi-year campaign to establish dedicated CPT codes for extended continuous monitoring—working with specialty societies, assembling clinical evidence that longer wear actually delivered distinct value, and navigating the AMA’s CPT Editorial Panel, the group that decides what “counts” as a billable medical service.

In 2013, iRhythm hit a major milestone: it secured Category I CPT codes that better reflected the Zio service model. Category I codes are the ones payers take seriously—recognized across the industry as established clinical care. It wasn’t just a reimbursement win. It was institutional validation that extended-wear monitoring had graduated from novelty to accepted practice.

With coding clarity came a clearer business model. A Zio test typically generated a few hundred dollars of revenue depending on payer mix and service components. The costs were straightforward but real: the disposable patch, shipping and logistics, lab processing, report generation, and customer support. And because iRhythm ran the whole workflow as an IDTF, it could build fixed infrastructure once and then spread it across growing volume. Over time, that model produced strong gross margins—eventually landing in the high 60% to 70% range.

That created the playbook. Drive more tests. Spread fixed costs thinner. Improve margins. Reinvest in sales coverage, operations, and evidence generation. Repeat.

But reimbursement didn’t suddenly become “solved.” The payer world was still fragmented. Medicare mattered enormously—cardiac monitoring skews older, and Medicare is the biggest single player. But commercial insurance was hundreds of separate negotiations, each with its own coverage policies and payment rates. iRhythm built a dedicated reimbursement team to grind through that reality, contract by contract, payer by payer, working to establish coverage and better predictability.

By 2016, the company had provided the Zio Service to more than 500,000 patients and collected over 125 million hours of curated heartbeat data. It believed it was positioned to disrupt a well-established U.S. ambulatory cardiac monitoring market worth about $1.4 billion.

Behind the scenes, iRhythm was also building for scale. It expanded its salesforce to call on cardiologists and drive prescribing. It increased operational capacity to handle rising test volume. It optimized the IDTF engine so reports could be generated reliably and efficiently.

The company was starting to look like a growth machine. But there was one more requirement for that machine to really accelerate: capital.

VI. Going Public & Hypergrowth (2016–2020)

By 2016, iRhythm had a working playbook, growing volumes, and a business model that looked like it could scale. What it needed next was fuel.

On October 19, 2016, iRhythm priced its IPO: 6,294,118 shares at $17 per share. The next day, October 20, it began trading on NASDAQ under the ticker IRTC.

Wall Street didn’t just show up. It lunged. The deal priced above the expected $13–$15 range, the share count was raised from the original plan, and the stock opened its first day around $26.75. J.P. Morgan and Morgan Stanley led the offering. For investors, this wasn’t just another medtech IPO. It was a bet that iRhythm had found the rare combination of clinical proof, operational leverage, and a reimbursement pathway sturdy enough to support a category shift.

To mark the moment, CEO Kevin King rang the NASDAQ Closing Bell. King had joined iRhythm in 2012, and his rise coincided with a transition the company desperately needed: from scrappy startup energy to public-company execution. His style—disciplined, operationally focused, and deeply attuned to the realities of reimbursement—fit the next phase. iRhythm wasn’t going to win by being flashy. It was going to win by running the machine better than anyone else.

The IPO proceeds gave iRhythm room to scale: more processing capacity, more sales coverage, more product development. But just as importantly, going public gave the company something harder to buy—validation. It made Zio feel less like a new experiment and more like an emerging standard.

And the numbers followed. In the years after the IPO, revenue grew at better than 30% a year. Patient volumes climbed. The sales force expanded. Zio spread from early adopters into more health systems and community cardiology practices. The flywheel looked increasingly familiar: invest in sales, drive test volume, spread fixed IDTF costs across more patients, and use the resulting leverage to keep reinvesting.

That didn’t mean profitability arrived right away. In its IPO paperwork, iRhythm was clear: it was still losing money, by design. For the first half of 2016, it reported $28.6 million in revenue and a $10.6 million net loss. But strong gross margins held out the promise that, if volume kept compounding, the model could eventually print cash.

The product line also started to mature into a portfolio. Zio XT became the core extended-wear offering. Zio AT expanded the addressable market to patients who needed more urgent, near-real-time monitoring, adding wireless transmission so critical arrhythmias could be flagged quickly. iRhythm wasn’t just refining a patch; it was trying to cover more clinical scenarios and stay ahead of copycats.

Underneath the hardware, iRhythm kept investing in software. ZEUS—its Zio ECG Utilization Software—was the wedge. Instead of relying purely on human review, iRhythm used machine learning to help identify and characterize arrhythmias at scale, improving both accuracy and efficiency as volumes rose. In this business, faster and better reports weren’t a nice-to-have. They were the unit economics.

That’s where the data advantage started to look like something more than a talking point. By the time of the IPO, iRhythm had already provided the Zio Service to more than 500,000 patients and collected over 125 million hours of curated heartbeat data. Every additional test made the system smarter, and that compounding effect was difficult for competitors to match quickly.

Competition, of course, wasn’t standing still. BioTelemetry was the closest pure-play rival, building its own extended monitoring business. Legacy giants like GE and Philips still owned the older workflows and relationships. But iRhythm was increasingly seen as the tech-forward category leader—the company building not just a device, but a modern diagnostics platform.

By 2019, that narrative had become consensus. iRhythm’s revenue had passed $200 million, and its market cap signaled strong confidence in continued growth. In digital health circles, it started to look like one of the cleanest stories out there: a simple product, a scalable service model, powerful secular tailwinds, and what seemed like a durable edge in data and algorithms.

Then came 2020, and everything changed.

VII. The Reimbursement Crisis & Stock Collapse (2020–2021)

2020 started out looking like another step in iRhythm’s march toward becoming the default in ambulatory cardiac monitoring. COVID did what it did to almost every healthcare business—patient volumes dipped as hospitals triaged and postponed non-urgent care—but the core story still felt intact.

Then, in August 2020, iRhythm got what looked like a gift from the one stakeholder that matters more than any other: Medicare. In the draft 2021 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, CMS proposed new, permanent codes for long-term ECG monitoring and recording. Investors read it as the system finally catching up to what iRhythm had been arguing for years: long-term continuous monitoring wasn’t a niche upgrade—it was a meaningful clinical improvement. The stock popped, jumping 33% on the news.

CEO Kevin King leaned into the moment: “We are pleased with the new code sets and the proposed rates in the Proposed Rule. The new codes are validation of the clinical importance of long-term continuous monitoring and the proposed rates reflect the significant clinical value of our Zio XT service.” The proposed rates looked supportive—higher than what the market had been used to—and Wall Street treated it like a green light for the next leg of growth.

And then, four months later, the floor dropped out.

In December 2020, CMS released the final 2021 Physician Fee Schedule rule—and it didn’t finalize national pricing for extended external ECG patches. Instead, it pushed pricing down to the Medicare Administrative Contractors, or MACs, the regional contractors that actually process Medicare claims and decide what gets paid in practice.

The market understood what that meant immediately. iRhythm shares fell 24% overnight.

On paper, this might have looked like a boring policy footnote. In reality, it turned reimbursement into a regional lottery, and iRhythm’s ticket was drawn in the worst possible place.

iRhythm ran its primary IDTF service center in Texas. That meant its Medicare fate sat with the MAC that covered Texas and several south-central states: Novitas Solutions (which also handles claims nationally for the Indian Health Service and the Veterans Affairs system). With CMS stepping aside, Novitas became the de facto price-setter for iRhythm’s core service.

In January 2021, Novitas set Medicare rates for extended external monitoring in the neighborhood of $40 to $50. In April, the contractor later increased the reimbursement for iRhythm’s primary code to $115. But even then, it was still almost $200 below what iRhythm had historically received.

Put more bluntly: in early 2021, Medicare payment for iRhythm’s long-term continuous ECG monitoring fell from more than $300—a rate that had held since 2012—to roughly $100.

The business implications weren’t subtle. CMS claims accounted for about 27% of iRhythm’s 2020 revenue. Long-term monitoring was about 95% of the company’s total business. So this wasn’t a cut to a side project. It was a two-thirds haircut to the price of the product that essentially was the company, with no matching way to shrink the costs overnight.

The stock did what the math told it to do. After more than tripling between January 2020 and January 2021, iRhythm’s shares collapsed—down more than 68% from the January peak.

As the reimbursement crisis unfolded, the leadership situation got whiplash-inducing. Kevin King retired as president and CEO in December 2020, effective January 12, 2021. Former Medtronic executive Mike Coyle took over, only to step down for personal reasons in June 2021 after roughly four months—four months dominated almost entirely by the Novitas pricing saga.

Coyle said on a fourth-quarter earnings call that iRhythm and others in the category met with Novitas to push for revisions. But the posted rates still shocked the industry and analysts.

Meanwhile, iRhythm was stuck choosing between bad options. Keep serving Medicare fee-for-service patients at reimbursement levels that meant losing money on each test. Exit Medicare and focus on commercial payers—at the cost of abandoning a large older patient base and risking physician relationships. Or fight for higher rates through every available channel while trying to survive long enough for the policy to change.

After iRhythm announced it would not provide Zio XT services through Medicare fee-for-service, the list of remaining plays narrowed fast. One option floated publicly was to pursue coverage through a different MAC and hope for a better outcome. Coyle said the company was engaged with other MACs, without offering specifics.

And while iRhythm was absorbing this body blow, the rest of the industry was consolidating around the opportunity. Philips acquired BioTelemetry for $2.8 billion in December 2020. Boston Scientific bought Preventice for $925 million in January 2021. Hillrom agreed to acquire Bardy Diagnostics for $375 million, also in January 2021. The market was basically saying, “cardiac monitoring is strategic,” at the exact moment iRhythm’s business model was being kneecapped by reimbursement policy.

In September 2021, iRhythm named Quentin Blackford as CEO—its second CEO appointment since King stepped down. Blackford came from Dexcom, where he had been COO, and officially took over on October 4. Investors liked the stability signal; the stock jumped more than 34% when the market opened Monday after the announcement.

But a new CEO didn’t magically fix the underlying problem. iRhythm was still operating in a fog of uncertainty created by the single most powerful force in healthcare: who pays, how much, and under what rules.

The lesson landed with a thud. In healthcare, regulatory and reimbursement risk can overwhelm almost everything else. iRhythm had the best-known brand in its category, deep physician adoption, strong clinical evidence, and the biggest dataset. None of that mattered when a government contractor rewrote the economics of the business in a single decision. The company that had modernized cardiac monitoring suddenly had to do something even harder: fight for survival.

VIII. The Turnaround & Reinvention (2021–2023)

Quentin Blackford walked into iRhythm with the mandate you give to a new CEO when the building is still smoldering: stabilize the business, restore credibility, and find a path back to growth. His background at Dexcom—another company that lived and died by reimbursement decisions—made him a natural fit for the moment. He understood that iRhythm couldn’t just argue its way out of the crisis. It had to re-architect the company so that one payer decision couldn’t threaten its existence again.

Publicly, Blackford kept the message crisp: “We firmly believe that national pricing remains the best option for all stakeholders.” iRhythm continued to press its case—working with medical societies, industry coalitions, and CMS—to push extended monitoring back toward predictable, stable reimbursement.

On the third-quarter 2021 earnings call, he laid out what that fight looked like in practice: “iRhythm has been pursuing parallel paths to support fair and stable Medicare pricing for these Category I CPT codes. iRhythm remains engaged with the MACs regarding an alternative costing model and has continued to work with industry participants to submit additional cost data for consideration. We, along with our industry coalition, have made meaningful progress against this milestone.”

But through 2021, the company was still stuck inside the blast radius of the Novitas rates. The stock remained under pressure, lurching lower after the initial cut and taking another hit in April. Leadership churn only amplified the sense of instability: Mike Coyle had stepped down in June after roughly four months on the job, and Blackford didn’t officially take over until October.

Early 2022 finally brought signs of a thaw. Baird analyst Mike Polark noted that the market “has been building in roughly a $200 placeholder for the Medicare rate.” William Blair analysts went further, projecting that improved pricing could create revenue upside of $55 million and $58 million for 2022 and 2023, respectively. “While still below pre-2020 rates of $311, we believe a $233 CMS rate would be a viable and profitable rate that would help give more confidence in the long-term viability of the extended holter market.” Put differently: the business didn’t need a full rewind to survive—but it did need rates that didn’t make each test an exercise in value destruction.

If those improved rates had been in place a year earlier, iRhythm estimated it would have translated into roughly a 10% lift to total revenue in 2021. That framing mattered, because it hinted at a future where Medicare wasn’t a black hole—it was simply another payer line to manage.

At the same time, iRhythm moved on multiple fronts, because it had to. Diversification stopped being a buzzword and became a survival strategy. The company worked to broaden its payer mix and reduce dependency on Medicare fee-for-service. It also leaned harder into products that lived under different reimbursement codes and clinical use cases—especially Zio AT, its mobile cardiac telemetry offering with real-time transmission.

The other lever was cost. The crisis had exposed how vulnerable the model was when pricing moved faster than the cost base could. So iRhythm turned its attention inward: manufacturing automation, service delivery optimization, and administrative efficiency, all aimed at lowering the break-even point and making the system more resilient.

Geography became part of the hedge, too. International expansion—previously more “nice to have” than core strategy—took on a new urgency. The UK and Europe offered growth, but more importantly, they offered different reimbursement dynamics. The markets were smaller and required a different go-to-market approach, but they provided something iRhythm had learned to value the hard way: diversification against U.S. policy whiplash.

Even as all of this was happening, iRhythm kept investing in the platform. ZEUS continued to evolve, adding capabilities for arrhythmia characterization and risk stratification. In 2022, iRhythm won FDA clearance for its AI-powered AFib software, dubbed ZEUS, covering the system’s algorithms and a digital arrhythmia reporting service. The company planned to begin rolling out the Zeus system within a limited number of clinical trials in 2023.

And then there was Verily. iRhythm’s long-running partnership with Google’s life sciences subsidiary produced the Zio Watch, extending the platform to a wrist-worn form factor. After a long journey, the collaboration reached its regulatory milestone: the FDA cleared the pair’s smartwatch and software used to detect atrial fibrillation.

By 2023, iRhythm wasn’t “back” in the old, carefree sense—the company had been changed by the experience. But the recovery was visible. Revenue growth resumed, even if from a constrained base. Gross margins stabilized. The business that had nearly been taken out by a reimbursement decision was still standing, and it was rebuilding with a very specific lesson baked into its strategy: the product could no longer be the only plan.

IX. Modern Era: AI, Competition & The Future of Cardiac Care (2023–Present)

By 2023, iRhythm had made it through the reimbursement fire. The next question was whether it could do more than survive—whether it could compound again.

In early 2025, CEO Quentin Blackford framed 2024 as a turning point: “Our fourth quarter capped a transformative year for iRhythm, marked by 24% revenue growth and significant operational achievements. We achieved record new account onboarding, with balanced volume contributions across multiple channels, particularly in risk-bearing, primary care settings where Zio's value as a population health management tool has resonated strongly. Throughout 2024, we enhanced our quality systems, improved customer experience through EHR integration and innovative product launches, expanded into multiple international markets, and secured strategic technology licensing agreements to advance connected patient care.”

The financials backed up the tone shift. For full-year 2024, iRhythm reported $591.8 million in revenue, up 20.1% from 2023. Fourth quarter revenue was $164.3 million, up 24.0% year-over-year. The company also narrowed its losses dramatically in the quarter: Q4 2024 net loss was $1.3 million, an improvement of $37.4 million versus Q4 2023.

It wasn’t a straight line to profitability, though. iRhythm ended 2024 with a full-year net loss of $113.3 million, even as progress continued. Operating expenses for the year rose 14.5% versus 2023—evidence that iRhythm was still spending to grow, even as it tried to prove it could do so efficiently.

The balance sheet offered breathing room. iRhythm reported cash reserves of $535.6 million, up from the prior quarter—financial flexibility to keep investing in products, software, and expansion without living quarter-to-quarter.

For 2025, iRhythm guided to revenue of approximately $675 million to $685 million. Blackford emphasized that the growth was coming from deeper penetration and earlier use in the care pathway: “In our core U.S. business, we achieved a record number of Zio registrations from across different channels—serving over 2 million patients, advancing Zio utilization earlier in the patient care pathway, and growing our market penetration within ambulatory cardiac monitoring.”

Later, iRhythm updated its outlook again, projecting full-year 2025 revenue of $690 million to $700 million, with adjusted EBITDA margin expected to be about 7.5% to 8.5% of revenue. The message was clear: growth was back on the table, and so was operating leverage—but the company still had something to prove.

The competitive landscape iRhythm faced in this era looked nothing like the one it entered as a category creator. The consolidation wave that hit during the reimbursement crisis didn’t slow down. Philips acquired BioTelemetry for an implied enterprise value of $2.8 billion in December 2020. BioTelemetry brought Philips an established ambulatory diagnostics portfolio across Holter monitoring, long-term monitoring, event recorders, and mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry—on a base of $450 million in 2020 sales.

That deal changed the matchup. iRhythm wasn’t just competing with another specialist anymore. It was competing with a healthcare giant that could pair cardiac monitoring with a broader enterprise footprint, deep hospital relationships, and global distribution. The dynamic shifted from “better patch wins” to “platform versus platform,” and iRhythm was the smaller platform.

At the same time, the fastest-growing “competitor” didn’t look like a traditional medtech company at all. Consumer wearables put heart monitoring into everyday life. The Apple Watch ECG feature, FDA-cleared for AFib detection, made the concept of rhythm monitoring mainstream—millions of wrists, one tap away. It’s not the same clinical tool as prescription monitoring—spot-check ECGs aren’t continuous, professional-grade monitoring—but it changes behavior. For some patients and some use cases, “good enough” at a fraction of the cost becomes a real substitute.

iRhythm’s answer has been to widen the playing field: more markets, more channels, and more integration into clinical workflow. Internationally, the company crossed a notable milestone in late 2024: more than 10,000 billable registrations in a single quarter in the UK. It also began receiving physician orders after commercial launches in four additional European countries. In the U.S., it received FDA 510(k) clearance for updates to the Zio AT device tied to FDA remediation efforts.

Japan became another step in that international push. With a recent commercial launch there, iRhythm said it was now actively driving physician and health system awareness of Zio in six markets outside the U.S.—progress that contributed to a cumulative milestone: 10 million patient reports posted since iRhythm’s inception.

Underneath all of this—new markets, new channels, new competitors—the company’s core argument has stayed consistent: the data advantage compounds. iRhythm points to more than 100 original scientific research manuscripts supporting the Zio service. It also highlights performance claims around usability and signal quality: Zio AT’s patient-centered design drives high compliance and analyzable time with minimal noise or artifact, with real-world data showing 98% patient compliance. The company also reports that physicians agree with the Zio service’s comprehensive end-of-wear report 99% of the time.

That’s the modern iRhythm pitch in one sentence: wearable biosensors plus cloud analytics plus proprietary algorithms that turn millions of heartbeats into something a clinician can act on.

But the path forward is still full of tradeoffs. iRhythm has to keep pushing its technology and AI capabilities while competitors close in. It has to grow volumes without getting squeezed on pricing. It has to expand internationally while still living with U.S. reimbursement risk. And it has to keep investing in the platform while demonstrating it can generate durable profitability.

The company that came out of 2020–2021 is tougher and more disciplined. The problem is that the arena is tougher now, too.

X. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

iRhythm’s journey is a reminder that in healthcare, the “best product” is never the whole story. The winners are the companies that can align clinical value, workflow, and payment—and keep them aligned when the rules change.

The Hardware-as-a-Service Model: iRhythm didn’t win by selling a better gadget. It won by selling a completed diagnostic episode. The patch was disposable, but the product was the service: capture the data, process it, run it through algorithms, and deliver a clinician-ready report. That turned what could have been a one-time device sale into something closer to recurring volume, built stickiness through workflow integration, and raised the bar for competitors who’d need to replicate the full machine—not just the patch.

Clinical Evidence as Competitive Moat: Cardiology doesn’t move on vibes. Physicians change practice when evidence piles up and stays consistent in the real world. iRhythm leaned into that reality early, investing in studies, peer-reviewed publications, and outcomes data. Over time, it built a deep body of validation—more than 100 scientific research manuscripts supporting the Zio service—that’s hard to shortcut. New entrants don’t just need a product that works; they need years of proof that it works in messy, everyday practice.

The Reimbursement-as-Strategy Reality: The 2020–2021 crisis made the brutal rule plain: reimbursement isn’t a back-office detail. It can be the business. A single payer decision—or worse, a single contractor—can rewrite your unit economics overnight. iRhythm’s experience showed how vulnerable even a category leader can be when payment policy shifts. The takeaway is uncomfortable but clear: reimbursement strategy, payer diversification, and policy risk management are existential, not optional.

Data Network Effects: Every Zio test generates more annotated ECG data, and that data improves the algorithms behind the reports. Better algorithms mean better signal, better detection, and a better clinician experience—which drives more adoption and more data. That compounding flywheel is one of iRhythm’s most durable advantages, and it’s not easily matched without similar scale and time in market.

Managing Through Crisis: When the payment floor drops out, the companies that survive have options. Diversification across products, payers, and geographies reduces concentration risk. A strong balance sheet buys time when negotiations and policy processes move slowly. And leadership stability matters more than most people want to admit—iRhythm’s CEO churn during the crisis added friction at the exact moment the company needed consistency.

Category Creation vs. Category Leadership: iRhythm didn’t just compete inside the Holter market; it helped create the modern category of extended continuous monitoring. That meant years of physician education, evidence generation, and grinding through coding and reimbursement so the market could even function at scale. Category creators pay the upfront cost that followers avoid—but if they execute, they earn mindshare, relationships, and a first-mover position that can last for a long time.

XI. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces:

Threat of New Entrants (Medium): The moat around iRhythm is real, but it’s not a castle with a single drawbridge. A new entrant has to clear FDA 510(k), which is doable—but slow, documentation-heavy, and unforgiving if you don’t know the process. Then there’s the unglamorous part: building an IDTF operation that can process tests reliably, meet compliance requirements, and turn raw ECG into a clinician-ready report at scale. And even if you nail the product and the operations, you still have to climb the longest hill of all: payer coverage, contracting, and reimbursement rates. That can take years, and it’s where many “better tech” stories go to die.

Still, the barriers mostly stop casual entrants, not strategic ones. Well-capitalized players—especially tech giants like Apple or Google—can afford the time and talent to push through regulatory and operational friction. Consumer wearables companies are already creeping toward clinical use cases. And large hospital systems could, at least in theory, try to bring pieces of monitoring in-house. So the door isn’t wide open—but it isn’t locked, either.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Low): Zio is built from components that are mostly commodities: sensors, adhesives, batteries, chips, and memory. There are multiple suppliers for most inputs, and iRhythm’s scale gives it leverage when negotiating. There’s no single chokepoint supplier that can realistically hold the business hostage or force structural margin compression.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (High): This is iRhythm’s exposed flank. The buyers with the most power aren’t patients or even physicians—it’s payers: Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial insurers. The reimbursement crisis in 2020–2021 was the purest demonstration possible that payment rates can change fast, and the company has limited ability to “price” its way out of it.

And the economics are structurally awkward. Physicians prescribe, but patients typically don’t pay directly. iRhythm can’t simply raise prices like a normal consumer business, because the entity that values the product isn’t the same one writing the check. The payer sets the terms, and iRhythm has to live inside them.

Threat of Substitutes (Medium-High): Zio sits in a busy intersection of alternatives. Consumer wearables can screen for AFib at scale and at low cost, which makes them a real substitute for some use cases—even if they don’t match prescription-grade continuous monitoring. Implantable loop recorders can monitor for far longer periods in higher-risk patients. Traditional Holters still cover short-duration needs. In-hospital telemetry owns acute settings.

None of these substitutes perfectly replaces Zio across the board, because they solve different clinical problems. But together, they put a ceiling on pricing power and force iRhythm to keep proving why its specific combination of duration, data quality, and clinical reporting matters.

Competitive Rivalry (High): This is a crowded fight, and it’s getting more crowded. Philips/BioTelemetry is the biggest integrated competitor. Boston Scientific/Preventice is in the mix. Legacy device makers continue to iterate. New entrants increasingly pitch AI as the wedge.

Price pressure is part of the landscape, but so is differentiation pressure: iRhythm has to keep refreshing its edge in clinical evidence, workflow integration, and report quality. In this market, yesterday’s advantage becomes today’s baseline surprisingly fast.

Hamilton's 7 Powers:

1. Scale Economies (Moderate): iRhythm’s model has meaningful fixed costs—IDTF infrastructure, regulatory compliance systems, algorithm development—that get cheaper per test as volume rises. More tests improve unit economics. But this isn’t a pure winner-take-all market. Multiple competitors can reach sufficient scale, which means scale helps, but it doesn’t guarantee dominance.

2. Network Effects (Emerging): The network effect here is data, and it compounds slowly but meaningfully. More patients produce more labeled rhythm data, which can improve algorithms, which can improve diagnostic performance and efficiency, which should support adoption. There’s also a softer effect: physician familiarity. When clinicians get used to a workflow and trust the reports, they’re more likely to keep prescribing.

But this isn’t a classic multi-sided network effect like a marketplace. It’s real—just not explosive.

3. Counter-Positioning (Historical, Fading): Early on, iRhythm benefitted from incumbents’ reluctance to cannibalize the old Holter model. A disposable, extended-wear patch plus outsourced analysis wasn’t just a new product—it was a different business. That hesitation created space for iRhythm to build the category.

Over time, that advantage eroded. Competitors adapted, built similar offerings, or bought their way in through acquisitions. Counter-positioning helped iRhythm get started, but it’s no longer a reliable shield.

4. Switching Costs (Moderate): Switching isn’t frictionless. Practices need to learn a new platform, and any integration into electronic health records creates real stickiness. Payer contracting and prior authorization processes add administrative drag.

Still, most practices can switch providers if they’re motivated to. And patient switching costs are low, because monitoring is usually episodic—a test, not a lifetime commitment.

5. Branding (Moderate): In cardiology, “Zio” has become a recognized name, and that matters. Medical device branding isn’t about Super Bowl ads—it’s about trust, reputation, and comfort under clinical scrutiny.

But it’s also narrow. This is specialist brand equity, not mass-market consumer awareness. It helps inside the prescribing ecosystem, but it doesn’t carry the broad protective power of a consumer giant.

6. Cornered Resource (Strong — Data): This is iRhythm’s strongest durable advantage: its proprietary database of ambulatory ECG recordings, built over more than a decade. The value isn’t just the volume—it’s the annotation, the clinical context, and the operational systems that turn recordings into usable training data.

Competitors can build datasets, but they can’t time-travel. Accumulating years of comparable clinical data at scale is expensive, slow, and hard to shortcut. Combined with the models trained on it, this is a true cornered resource.

7. Process Power (Moderate-Strong): Running an IDTF at scale isn’t just “operations.” It’s a muscle built over years: consistent report turnaround, high accuracy, quality control, clinician education, customer support, and the hundreds of small workflow details that keep the machine from breaking.

No single process advantage is decisive on its own, but together they create a meaningful execution edge—especially in a category where reliability and trust are the product.

Overall Assessment: iRhythm’s strongest powers are its cornered resource (data) and its process power. They’re hard-won advantages that take time to replicate. But the company’s biggest vulnerability—buyer power through reimbursement—can override almost everything else, as 2020–2021 proved. The position is durable only with continued investment in AI, evidence, and execution, because well-resourced competitors can attack from multiple angles.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

The tailwinds are hard to ignore. Atrial fibrillation rises as populations age, and projections suggest as many as 33 million Americans could have AFib by 2050. The stakes are high because AFib is often silent—and when it’s missed, it can show up later as a stroke. That makes “find it earlier and more reliably” one of the most valuable jobs in healthcare, with a market that keeps getting bigger.

iRhythm enters that market as the category leader. With Zio, it has captured over 30% of the core ambulatory cardiac monitoring market. That position wasn’t bought; it was built—through years of clinical evidence, physician adoption, and an IDTF operation that can turn raw signal into a report clinicians actually trust. And in medicine, trust is sticky. Once a workflow is embedded and physicians are comfortable with the output, switching isn’t just inconvenient—it’s risky.

Then there’s the compounding advantage: data. iRhythm’s ECG database—built from millions of patient-days of annotated rhythms—feeds its AI and improves the product over time. Each additional test makes the system smarter, which can improve detection and efficiency, which helps the economics, which supports more adoption. Competitors can catch up on features, but catching up on years of labeled clinical data is slower and more expensive.

Reimbursement, for now, looks less like a cliff and more like a landscape iRhythm can navigate. The 2020–2021 shock appears to be in the rearview mirror. Rates are lower than the old highs, but they support workable unit economics, and the company has been actively reducing its dependence on Medicare fee-for-service by leaning more into commercial payers and expanding internationally.

That international story is still early. iRhythm has established a commercial presence in the UK and has been pushing into additional European countries and Japan. Those markets won’t mirror the U.S., but that’s part of the point: different reimbursement systems can mean both new growth and less single-point-of-failure risk.

Financially, the next milestone is symbolic as much as it is practical. iRhythm has been projecting 2025 as its first free cash flow positive year, while also pushing a much bigger ambition—expanding its total addressable market to 27 million patients. If it can keep growing while proving durable profitability, the market will start to value it less like a fragile reimbursement story and more like an enduring diagnostics platform.

And there’s always the strategic angle. A category-leading cardiac monitoring platform could be attractive to a larger healthcare technology or medtech buyer that wants the capability, the customer relationships, and the dataset. In that scenario, strategic value to an acquirer like Medtronic, Abbott, or a similar player could exceed what public markets assign on standalone fundamentals.

Bear Case:

The bear case starts with the same three-letter acronym that nearly broke the company before: CMS. Reimbursement risk doesn’t go away—it just goes quiet for a while. CMS can rewrite rules, and Medicare Administrative Contractors can reset rates. iRhythm already lived through the nightmare scenario where a single policy change threatened the economics of its core product. The company can lobby, advocate, and diversify, but it can’t control the outcome.

There’s also the commoditization trap. As extended monitoring becomes more standard, the patch itself risks becoming “good enough” hardware. Competitors like Philips/BioTelemetry offer similar services and can lean on broader hospital relationships. If the market turns into a pricing fight, margins compress—and iRhythm’s advantage has to come from workflow, data, and outcomes, not just form factor.

Consumer wearables are the other squeeze. Apple Watch, Fitbit, and others bring AFib screening to consumer price points and consumer distribution. They’re not the same as prescription-grade continuous monitoring, but for many people—especially younger and lower-risk patients—“good enough” is how substitution happens. Even if wearables don’t replace Zio in core clinical use cases, they can narrow the funnel of patients who ever get referred for a prescription test.

Profitability is still a promise, not a fact. iRhythm’s full-year 2024 net loss was $113.3 million, and it has operated at a loss throughout its time as a public company. The path to profitability may be credible, but it requires execution: holding margins, controlling operating expenses, and continuing to grow in a market where buyer power is structurally high.

Competition keeps intensifying from multiple directions at once. Philips/BioTelemetry brings global scale. New AI-first entrants can try to differentiate on algorithms and automation. Hospital systems may increasingly bring monitoring in-house to capture the economics and control the workflow. iRhythm’s moat exists, but it isn’t self-sustaining—it has to be reinforced continuously.

Finally, there’s the risk that the patch isn’t the end state. Implantable loop recorders offer much longer monitoring for certain patients. Wearables could keep improving. New sensing modalities could emerge. If the industry shifts away from patch-based monitoring as the dominant form factor, iRhythm has to evolve fast enough to remain the platform, not the incumbent.

What to Watch — Key Performance Indicators:

1. Revenue Growth Rate: The clearest signal of whether iRhythm is still taking share and expanding use cases. Sustained double-digit growth suggests the platform is compounding; a slowdown could point to saturation or rising competitive pressure.

2. Gross Margin Trajectory: A real-time read on pricing pressure, manufacturing efficiency, and payer mix. Stable or improving margins above 65% suggest the unit economics are holding; sustained compression would be a warning sign that the category is turning into a commodity.

3. Medicare Reimbursement Rates: The existential variable. Any meaningful change in CMS policy or MAC pricing can quickly flow through to the business. This is the risk that never stops mattering—and the one iRhythm can’t afford to be surprised by again.

XIII. Epilogue & Future Outlook

iRhythm stands today as a battle-tested company: one that took an existential reimbursement shock, stayed on its feet, and came out the other side leaner, more diversified, and far more realistic about what actually drives outcomes in healthcare. The pre-2020 “just keep growing” optimism is gone. In its place is a hard-earned understanding that in this industry, the product is only half the battle—and the payment system can be the other half.

When former CEO Kevin King retired from the board, he put a bow on what the first era of iRhythm accomplished: “In my 10 years with the company, iRhythm has grown into a market leading company that has changed the standard of care in cardiac monitoring. We have served over four million patients and I am extremely proud of all that we have accomplished.”

Zoom out, and iRhythm’s story is really a story about healthcare’s direction of travel. Medicine is moving away from episodic, facility-based snapshots and toward continuous, tech-enabled monitoring in the flow of everyday life. Arrhythmia detection was the beachhead. But the infrastructure iRhythm built—wearable biosensors, cloud analytics, AI-assisted interpretation, and service delivery at scale—could, at least in principle, extend well beyond cardiac rhythms to other physiological conditions where “more data over more time” changes what clinicians can see and how they act.

AI in healthcare is still more promise than reality in most domains. But cardiac monitoring is one of the places where the promise has started to cash out. Deep learning models trained on huge ECG datasets can meaningfully improve detection and interpretation. The open question is durability: does iRhythm’s data and experience compound into a lasting edge, or do AI capabilities eventually become table stakes that every serious competitor can buy or build?

From here, several futures are plausible. iRhythm could continue as an independent category leader, expanding domestically and internationally while trying to stay ahead on algorithms, workflow integration, and operational efficiency. It could also become an acquisition target for a larger MedTech company that wants a modern cardiac monitoring platform—Medtronic, Abbott, Boston Scientific, or others—trading independence for scale and distribution. Or the market could consolidate further, with iRhythm ultimately playing either side of that equation as the space matures.

For founders, iRhythm is a case study in why business model moats can matter more than technology moats. The Zio Patch was a breakthrough, but survival depended on things that don’t fit in a demo: reimbursement pathways, clinical evidence, and an operational engine capable of delivering a consistent, trusted diagnostic service. Technology can be copied. The machine around it is harder to replicate.

For investors, the lesson is even sharper: in healthcare, policy is product. The best technology in the world can become uneconomic if reimbursement changes. Concentration risk—in payers, in geographies, in a single core offering—creates fragility. And regulatory scrutiny imposes constraints that most software businesses never have to think about.

The ultimate question for iRhythm is whether it can keep its lead as cardiac monitoring becomes increasingly software-defined. The patch matters, but the interpretation is where value keeps migrating. Can a company that started with a better way to capture the signal stay ahead when the real competition is in the algorithms that make sense of it? The next decade will decide.

XIV. Further Reading

If you want to go deeper, here are the sources and rabbit holes that map to the big threads in iRhythm’s story—product, reimbursement, clinical evidence, and the competitive backdrop.

Primary Sources: - iRhythm S-1 Filing (2016), SEC EDGAR — How the company described its business model, risks, and strategy going into the IPO - CMS Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Final Rules (2020–2023) — The policy documents behind the reimbursement whiplash - iRhythm investor presentations and earnings calls (2020–present) — Management’s real-time narrative through the crisis and recovery - FDA 510(k) clearances for Zio products — The regulatory breadcrumbs of how the product line evolved

Clinical Literature: - mSToPS Study Publication (JAMA, 2018) — The clinical case for longer-term monitoring and AF screening - Various publications on extended continuous cardiac monitoring clinical outcomes — A broader view of what longer monitoring changes in practice - Apple Heart Study publications — How consumer wearables fit into the detection conversation, and where they do (and don’t) overlap with clinical-grade monitoring

Industry Context: - BioTelemetry/Philips integration analysis — How a scaled incumbent absorbed a key competitor and what that meant for the market structure - "The Business of Healthcare Innovation" by Lawton Burns — A grounded look at how medical innovation actually gets commercialized - "The Innovator's Prescription" by Clayton Christensen — A useful lens for understanding disruption in healthcare (and why it’s so hard)

Historical Background: - "The History, Science, and Innovation of Holter Technology" (PMC) — The origin story of ambulatory monitoring and the long arc from analog to digital - "At the Heart of the Invention" — Smithsonian documentation of Holter monitor development and early ambulatory ECG history

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music