Innospec Inc.: From Toxic Legacy to Chemical Transformation

How a Company Built on One of the Most Harmful Industrial Products in History Reinvented Itself—and Survived a Global Bribery Scandal That Nearly Destroyed It

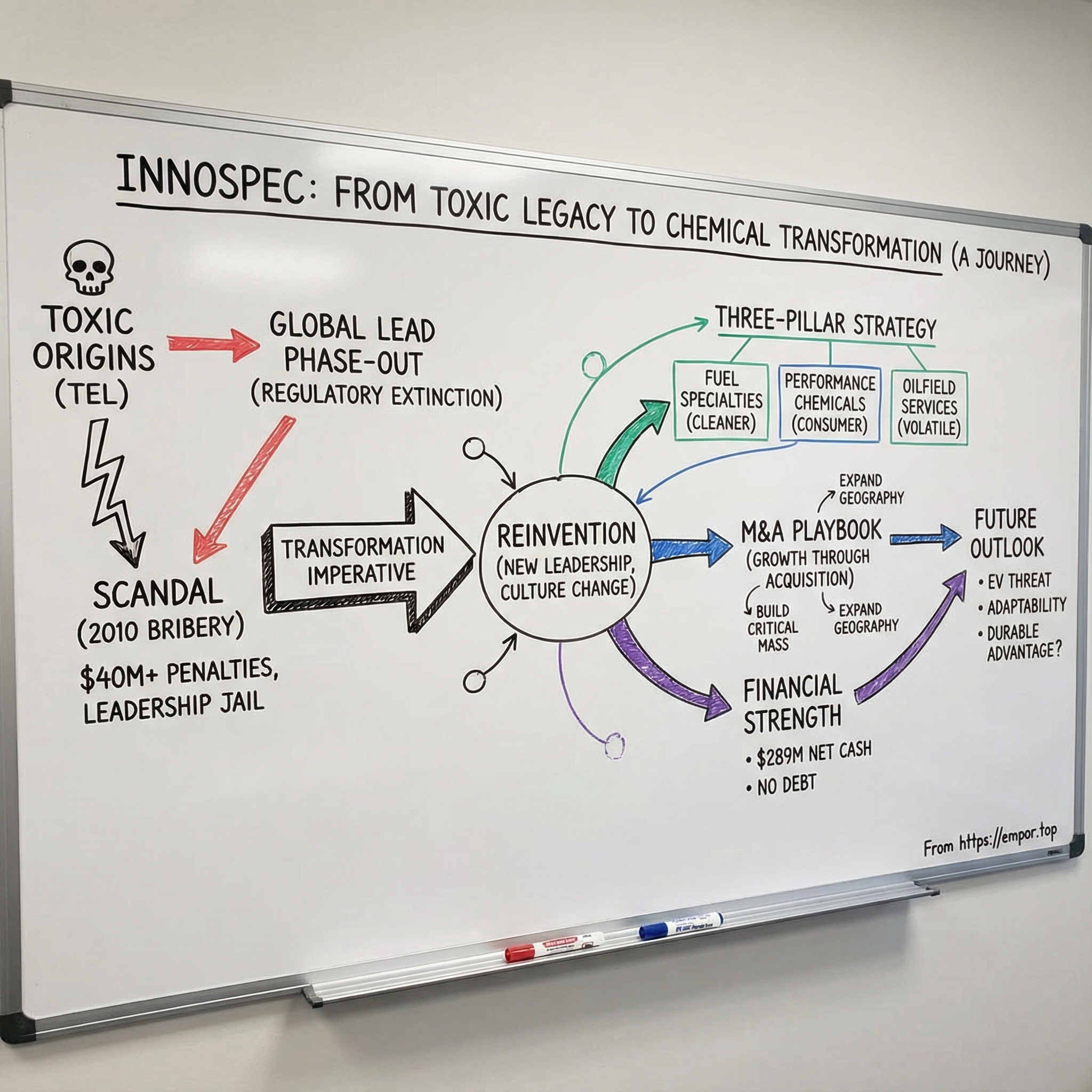

I. Introduction: The Central Question

Picture this: it’s 2021, and tetraethyl lead—the fuel additive that poisoned generations of children and left a measurable trail of damage across public health—is finally gone from motor gasoline everywhere on earth. In July 2021, Algeria ended production of leaded gasoline for cars, closing the last major chapter of a century-long mistake. A month later, on August 30, 2021, the United Nations Environment Programme declared the “official end” of leaded gasoline in cars worldwide.

And yet there’s a company headquartered in the Denver suburbs whose corporate DNA runs straight through that product.

That company is Innospec Inc.

Innospec’s story begins in 1938, when the business that would eventually wear its name was created for a single, clear purpose: manufacturing tetraethyl lead, the anti-knock additive that made engines run better while quietly loading the atmosphere, the soil, and human bodies with lead. Fast forward to September 30, 2025, and Innospec is a very different-looking enterprise—one with trailing twelve-month revenue of $1.79 billion.

So here’s the central question that makes this story worth telling: how does a company built on one of the most harmful industrial products in history reinvent itself?

And the harder follow-up: how does it survive a global bribery scandal—more than $40 million in penalties—where executives and intermediaries paid foreign officials specifically to keep that dying, toxic product alive longer?

This is a story about corporate transformation under pressure: a business watching its core product face regulatory extinction, a period where fear and incentives curdled into corruption, and a long, messy rebuild where survival required an ethical reckoning and a total rewrite of what the company stood for.

Today, Innospec—formerly known as Octel Corporation and Associated Octel Company, Ltd.—is an American specialty chemicals company organized around three business lines. Performance Chemicals serves personal care, home care, agrochemical, mining, and industrial markets. Fuel Specialties develops and supplies fuel additives. Oilfield Services provides drilling, completion, and production chemicals.

But getting here meant navigating a collapsing legacy business, criminal prosecution, judicial rebuke, and the painstaking work of building a new corporate identity with credibility. Along the way, Innospec accumulated lessons every founder and investor should recognize about adaptation, ethics, and what it really takes to build something durable in specialty chemicals.

II. The Toxic Origins: Tetraethyl Lead and the Birth of Associated Octel

The Discovery That Changed Everything

In 1916, a young engineer named Thomas Midgley Jr. started at General Motors. Five years later, in December 1921, he was working under Charles Kettering at GM’s Dayton Research Laboratories, chasing a problem that mattered to every car buyer: engine “knock,” that violent rattling that made motors feel weak, unreliable, and cheap.

Midgley tried one candidate additive after another. Tellurium worked, but it left an odor so stubborn it was basically a biological weapon. So they kept searching.

Then, on December 9, 1921, Midgley added a small amount of tetraethyl lead—TEL—to gasoline and fired up a one-cylinder test engine. The knocking vanished.

In the lab, it must have felt like magic: a tiny dose of chemistry turning a rough engine into a smooth one. In hindsight, it was something else: the starting gun for a public-health disaster that would later be associated with millions of deaths and widespread brain damage in children. Environmental historian J.R. McNeill would describe leaded gasoline’s legacy as having “more adverse impact on the atmosphere than any other single organism in Earth’s history.”

From day one, the marketing told you what the company wanted you to hear—and hid what it didn’t. They branded the additive “Ethyl,” carefully avoiding the word “lead” in reports and advertising. Automakers and oil companies—especially GM, which jointly held the patent tied to Kettering and Midgley—pushed TEL as the cheap, high-margin solution, positioned as superior to ethanol or ethanol blends that offered far less profit.

The catch was that the danger wasn’t some later discovery. Lead’s risks had been known since ancient times. Efforts to limit its use stretched back centuries. Midgley himself suffered lead poisoning, and by 1922 he was already being warned about the risks of TEL exposure.

And TEL wasn’t even new chemistry. German chemist Carl Jacob Löwig had first synthesized it in 1853. For decades it stayed a technical curiosity—too deadly to be useful. Midgley didn’t invent tetraethyl lead. He found the business model for it.

Death in the Factories

The bill came due immediately, first to the workers.

After two deaths and multiple cases of lead poisoning at the prototype TEL plant in Dayton, the mood inside the program reportedly collapsed. By 1924, staff in Dayton were said to be “depressed to the point of considering giving up the whole tetraethyl lead program.”

It didn’t stop. Over the next year, eight more people died at DuPont’s plant in Deepwater, New Jersey.

That same year, the story broke into public view. At Standard Oil refineries in New Jersey, five workers died and many others were badly injured. People exposed to concentrated TEL hallucinated, had seizures, and spiraled into madness before death. Newspapers dubbed it “loony gas,” and for a moment it looked like the entire idea might be killed off by outrage.

Instead, it was managed.

TEL sales were voluntarily suspended for a year while the U.S. Public Health Service held a conference in 1925 and conducted a hazard assessment. In 1926, a U.S. Surgeon General committee concluded there was no real evidence that selling TEL was hazardous to human health—while still urging further study.

And then the industry scaled.

Between 1926 and 1985, an estimated 20 trillion liters of leaded gasoline were produced and sold in the United States alone, at an average lead concentration of 0.4 g/L. In other words: the equivalent of about 8 million tons of inorganic lead, with roughly three quarters emitted as lead chloride and lead bromide.

The British Operations Take Shape

Now take that story across the Atlantic, into the pre-war urgency of late-1930s Europe.

With war looming, the British government concluded that high-octane aviation fuel would be essential. Leaded fuel boosted engine power, enabling aircraft to fly higher and farther. In the language of the time, it was the “magic bullet.”

The Associated Octel Northwich plant became the first UK site to manufacture Anti Knock Compound. Across Europe, TEL plants were appearing in Germany, France, and Italy. By 1938, the British Air Ministry decided it couldn’t rely on imports and moved forward with plans for its own production.

In September 1938, the company became The Associated Ethyl Co Ltd, and its product was named Octel Antiknock compound. Later, it became Associated Octel—partly to reduce confusion with the American competitor, Ethyl Corporation.

In 1940, the Air Ministry pressed ahead with a TEL factory at Northwich. It was completed just in time for the Battle of Britain, reducing dependence on supplies from the United States. The first charge of TEL was made on September 9, 1940.

That wartime necessity created the corporate ancestor of what would become Innospec. A business built to supply the chemistry behind Spitfires and Hurricanes would spend the next half-century selling essentially the same chemical advantage to civilian drivers—long after the evidence of harm had become overwhelming.

After the war, demand for anti-knock compounds rose as leaded fuel spread across car engines as well as aviation. In 1948, ownership changed and the Associated Ethyl Company was born. In 1961, the name changed again to “The Associated Octel Company limited.”

And that’s the core tension at the center of Innospec’s origin: this wasn’t just a company that happened to sell a controversial product. It was a company founded to make it, scaled by it, and shaped by the incentives that came with it. Everything that follows—its later compliance posture, its diversification, and its reinvention—starts here, with TEL as both the foundation and the stain.

III. The Inevitable Decline: Global Lead Phase-Out

The Science Finally Catches Up

By the 1960s, the excuse-making started to run out.

Independent researchers—most famously Clair Patterson at Caltech—published work showing that lead from gasoline wasn’t staying in tailpipes. It was spreading everywhere: air, soil, dust, and, most dangerously, into human bodies. And by mid-century, the picture sharpened into something undeniable: tetraethyl lead was a potent neurotoxin, with children paying the steepest price.

Regulators began to move. In the 1970s, the United States and other countries started phasing TEL out of automotive fuel. The EPA, not long after the agency was created, issued its first lead reduction standards in 1973 and set a glide path toward dramatically lower lead levels by the mid-1980s.

The rules were grounded in Section 211 of the Clean Air Act, as amended in 1970. Ethyl Corporation fought back in federal court. The EPA lost at first, then won on appeal—and the phasedown began in 1976.

Decades later, researchers tried to quantify what the world had lived through. A 2011 estimate attributed the legacy of tetraethyl lead to staggering annual harm worldwide: 1.1 million excess deaths, hundreds of millions of lost IQ points, tens of millions of crimes, and an estimated hit of around four percent of global GDP. Numbers that big almost stop being numbers. They’re the kind of scale that forces a different conclusion: this wasn’t a tragic side effect. It was an industrial catastrophe.

The Long Goodbye

For Associated Octel, this wasn’t just “regulatory risk.” It was a slow-motion extinction event.

The entire company had been built around one chemical advantage. Now, country by country, that advantage was being outlawed. The U.S. reached the total elimination of leaded gasoline sales for on-road vehicles on January 1, 1996. Japan became the first country to ban it completely in 1986. And then the phase-out continued—unevenly, but relentlessly—until 2021, when Algeria became the last country to ban leaded gasoline.

That uneven timeline created a strange, dangerous dynamic for a company like Octel. As the developed world shut the door, demand didn’t disappear everywhere at once. It migrated—toward developing markets with looser regulations and older vehicle fleets. For Octel, that looked like a lifeline.

It was also a trap.

The 1998 Spin-Off: A New Beginning

By the late 1990s, the corporate world was making its own decisions about how much longer it wanted to be associated with TEL.

Until May 22, 1998, Octel was a wholly owned subsidiary of Great Lakes Chemical Corporation. Then Great Lakes consummated a spin-off of its petroleum additives business, distributing shares in the Company to Great Lakes shareholders at a ratio of one Octel share for every four Great Lakes shares held. Octel began trading on the NYSE in May 1998.

Functionally, it was strategic triage. Great Lakes got distance from a declining, increasingly controversial business. And the newly independent Octel inherited the problem in full: manage a product everyone knew was dying, and somehow build a future before the cash ran out.

The company’s filings didn’t sugarcoat the plan. It intended to manage the decline “safely and effectively” and “maximize cash flow through the decline,” while taking continuous cost improvement measures to keep up with shrinking demand.

But there was also the first draft of reinvention. Early on, the company described a Specialty Chemicals unit with two developing areas: Petroleum Specialties and Performance Chemicals. Petroleum Specialties was still built on TEL operations, but it was also the bridge to a different business—developing and marketing a broader set of fuel additives and customized blends aimed at cleaner-burning, more efficient fuels.

That was the mandate for the next two decades, whether the company wanted it or not: pivot away from TEL and into specialty chemicals—or disappear.

IV. The Scandal That Nearly Destroyed Everything: The 2010 Bribery Case

The Desperation of a Dying Business

A company doesn’t usually wake up one morning and decide to run a bribery operation across multiple countries. It happens when a core business is dying, the remaining markets are the ones with the weakest guardrails, and the people in charge convince themselves that “just keeping things going” is worth any price.

For Innospec, that meant corruption—systematic payments meant to keep tetraethyl lead alive in places like Indonesia and Iraq even as the rest of the world moved on.

On March 18, 2010, Innospec Inc., with principal offices in the United States and the United Kingdom, agreed to pay $40.2 million to resolve global corruption claims brought by the Department of Justice, the SEC, OFAC, and the U.K.’s Serious Fraud Office. The coordinated investigation concluded that Innospec paid or promised more than $9.2 million in bribes to government officials in Iraq and Indonesia, tied to roughly $176 million in contracts for tetraethyl lead.

The context matters. TEL was still meaningful revenue, but it was in structural decline as clean air legislation spread across the U.S. and other countries. The company also paid kickbacks connected to Iraq through the United Nations Oil-for-Food Program. According to enforcement filings, Innospec’s former management didn’t stop it—management authorized and encouraged it. And internal controls didn’t catch it. The conduct kept going for years.

The Iraq Schemes

The Iraq conduct came in two waves.

First came the Oil-for-Food era. Innospec used an agent in Iraq—Naaman—to secure contracts with the Iraqi Ministry of Oil by paying kickbacks. Naaman paid kickbacks on Innospec’s behalf so the company could obtain five Oil-for-Food contracts to sell TEL to the Ministry and its refineries. On three of those contracts, the kickbacks amounted to 10 percent of the contract value.

Then the program ended—and the bribery didn’t.

After Oil-for-Food was terminated in late 2003, Innospec continued using its Iraq agent to pay bribes to Iraqi officials to secure more TEL sales. From at least 2004 through 2007, Innospec made payments totaling about $1.61 million and promised another roughly $884,000 to Ministry of Oil officials. The goal was to build goodwill, secure additional orders under a Long Term Purchase Agreement executed in October 2004, and help ensure a second LTPA in January 2008.

The misconduct wasn’t subtle. Innospec covered travel and entertainment for Ministry officials, including a seven-day honeymoon, provided mobile phone cards and cameras, and handed over cash as “pocket money.” It also paid bribes aimed at ensuring the failure of a 2006 field test of MMT, a fuel product made by a competitor.

The internal communications captured the mindset. In an October 2005 email, Innospec’s agent told a Business Director and an Executive that Iraqi officials were demanding a kickback before opening a letter of credit for a TEL shipment. The agent added: “We are sharing most of our profits with Iraqi officials. Otherwise, our business will stop and we will lose the market.”

The Indonesia Schemes

The SFO’s Opening Statement in the U.K. case laid out the Indonesia story in granular detail. Innospec Ltd. allegedly routed bribes through regular “commission” payments to an Indonesian agent, plus a separate stream of “ad hoc funds.” Internally, these funds were given euphemistic labels: “Lead Defense” fund, “compensation fund,” “exceptional promotional work,” “special bonus,” and even “cranes.” As described by the SFO, these payments weren’t just about winning a specific order. They were also meant to accumulate influence—to buy goodwill with Indonesian officials over time.

And critically, the purpose wasn’t neutral. Innospec paid bribes to support efforts to maintain TEL sales in Indonesia precisely when Indonesia was planning to go unleaded. The alleged scheme was designed to slow that transition—delaying cleaner fuels and prolonging exposure to a known neurotoxin.

In June 2010, a Guardian and Guardian Films investigation reported that Innospec—then operating as Octel—had bribed officials in Iraq and Indonesia with millions of dollars to keep TEL in use as a fuel additive. And TEL’s harm wasn’t theoretical: elevated lead levels are linked to brain damage in children.

The Judicial Rebuke

What made the Innospec case famous wasn’t only the conduct. It was the judge’s reaction to how the case was being resolved.

On March 26, 2010, at Southwark Crown Court, Lord Justice Thomas handed down a sentencing judgment for Innospec Limited after it pleaded guilty to conspiracy to corrupt. It was the first global settlement spanning criminal proceedings in both the U.K. and the U.S.—and the Court used the moment to draw a hard line.

Lord Justice Thomas emphasized that, under procedural rules at the time, the SFO had no authority to agree penalties with defendants. Sentencing belongs to the judiciary. Plea discussions may happen, but the Court must scrutinize any agreement and decide whether it actually serves the public interest in open and transparent justice.

He concluded that the Director of the SFO “had no power to enter into the arrangements made,” and warned that “no such arrangements should be made again.”

He also made clear where this conduct sat on the spectrum: bribing foreign government officials and ministers was, in his view, “the top end of serious corporate offending.” He said that an appropriate starting point for a fine would have been comparable to the U.S. fine—$101.5 million in this case—on top of stripping out the benefits obtained through criminality.

Individual Consequences

This didn’t just stain a corporate record. It ended careers—and it put people in prison.

Four men were sentenced for their roles in bribing officials in Indonesia and Iraq after an SFO investigation into Associated Octel Corporation (later renamed Innospec). Dennis Kerrison, 69, of Chertsey, Surrey, received four years in prison. Paul Jennings, 57, of Neston, Cheshire, received two years. Miltiades Papachristos, 51, of Thessaloniki, Greece, received 18 months. David Turner, 59, of Newmarket, Suffolk, received a 16-month suspended sentence and 300 hours of unpaid work.

At sentencing, Judge Goymer said the quiet part out loud: “Corruption at Innospec was ingrained and endemic—it was institutionalised.” Turner, who cooperated and gave evidence against Kerrison and Papachristos during their three-month trial, received the suspended sentence in light of that cooperation.

Years later, on September 19, 2014, the convictions against Dr. Papachristos and Mr. Kerrison were upheld by the Court of Appeal. Kerrison’s sentence was reduced from four years to three.

For anyone evaluating Innospec after the fact—investors included—this episode isn’t an asterisk. It was a breaking point. It forced changes in culture, leadership, and priorities, and it pushed compliance from a back-office function to something central to how the company operated.

V. The Transformation Imperative: Rebuilding from the Ashes

New Leadership, New Direction

When the bribery investigations were closing in, Innospec didn’t just need a legal strategy. It needed a future—and someone to build it.

In April 2009, the board appointed Patrick S. Williams as President and CEO. Williams wasn’t an outsider brought in to “clean house.” He was a longtime operator, having joined the company in 1993 and worked his way through a series of senior roles. By 2005, he was Executive Vice President and President of Fuel Specialties, and in 2008 he also took responsibility for Performance Chemicals.

He stepped into the top job at the bleakest possible moment: with regulators on both sides of the Atlantic investigating the company and the business staring down an existential question—whether it would be allowed to keep operating at all.

At the time, chairman Bob Bew put the optimistic spin on the transition, saying Williams had been central to Innospec’s growth and would lead it into “our next era of growth,” highlighting his industry knowledge, commitment to innovation, and “energetic and decisive leadership.” The subtext was obvious: Innospec had to prove it could survive, and that meant changing what it was known for.

The rebrand was part of that effort. The company had already formally become Innospec Inc. in January 2006, dropping the Octel name that had become inseparable from tetraethyl lead. But symbolism wasn’t enough. In practice, the company moved away from TEL in motor gasoline: it stopped selling TEL for use in motor gasoline, which had previously been supplied from the U.K. to Algeria. Later, the legacy business continued to shrink. The Octane Additives business ceased trading in 2020, and the manufacture of TEL used for 100LL avgas was transferred into the Fuel Specialties segment.

Cultural Transformation

A crisis like this doesn’t get solved by a press release, or even by writing a bigger check. It gets solved by changing incentives, controls, and norms—what people believe they can get away with, and what they believe leadership will actually punish.

Innospec’s public message after the scandal was clear: compliance had to become a core operating principle, not a box-checking function. CEO Patrick Williams would later point to the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and the U.K. Bribery Act as the baseline reality for doing business globally—laws that “have underpinned the need for absolute compliance with laws and regulations.” Under his leadership starting in 2009, the company said it invested heavily in the people and processes required to build what it described as a first-class compliance culture. Embedding that mindset, the company acknowledged, took time—but it was necessary to win back the confidence of customers, employees, and investors.

The transformation was also enforced externally. As part of the U.S. resolution, the Department of Justice required Innospec to retain an independent compliance monitor for at least three years and to fully cooperate with ongoing investigations. That monitoring period wasn’t cosmetic. It forced a rebuild of internal controls and compliance infrastructure from the ground up.

For any company that survives an ethical crisis, the real test is whether it changes how it operates when no one is watching. For Innospec, the settlement wasn’t just a financial penalty. It was a mandate to remake the company—who led it, how decisions were made, and which behaviors were no longer tolerated.

VI. The Three-Pillar Strategy: Building a New Innospec

Fuel Specialties: From Toxic to Clean

Fuel Specialties is the engine of modern Innospec. It’s the company’s largest segment, selling chemicals that help fuels burn cleaner and engines run better—additives that improve fuel efficiency, boost performance, and reduce emissions across automobiles, marine, and aviation markets. It also sells products used by oilfield service providers in the extraction of oil and gas.

The pivot here wasn’t incremental. It was existential: stop relying on TEL—the product that helped power the 20th century while polluting it—and build a business around the opposite value proposition. Instead of selling chemistry that added lead to the world, Innospec needed to sell chemistry that helped remove smoke, soot, deposits, and waste.

The demand drivers for this business aren’t mysterious, but they’re powerful: tighter air-quality rules, changes in engine technology, and the constant pressure to squeeze more efficiency out of every gallon. Overlay climate concerns, energy security, and volatile energy prices, and fuel quality legislation tends to follow. That legislation, in turn, creates a steady need for sophisticated additive packages. Add in the global push to diversify away from crude oil—through biofuels like biodiesel and bioethanol—and you get more fuel blends, more complexity, and more opportunities for companies that can make those blends behave in real engines.

Innospec’s Fuel Specialties portfolio reflects that reality. It markets detergents, cold flow improvers, lubricity improvers, corrosion inhibitors, antioxidants, cetane improvers, and other additive chemistries designed to meet modern fuel challenges. TEL is still in the catalog, but only as a small legacy product used in aviation gasoline for piston-engine aircraft.

Performance Chemicals: Consumer Products

If Fuel Specialties represents reinvention within the company’s historical neighborhood, Performance Chemicals is the clean break.

This segment sells specialty chemicals into the personal-care industry and other end markets across the Americas, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia-Pacific. Innospec positions it as technology-based solutions for customers in Personal Care, Home Care, Agrochemical, Mining, and broader Industrial applications.

The connective tissue is chemistry—especially surfactants and silicones. Surfactants are the molecules that help oil and water mix and make cleaning possible; they show up in shampoos and cleansers, and also in places you’d never expect, like fuel detergents and “frac” fluids. Silicone chemistry is the same story: in one context, it delivers shine and feel in hair-care products; in another, it helps control foaming in diesel fuel.

This is the strategic magic trick. Innospec didn’t abandon its technical core. It redeployed it. The formulation know-how that once served fuel customers could be translated into products people put in their hair, spray on their counters, or use in industrial processes.

Oilfield Services: The Volatile Third Leg

The third pillar is Oilfield Services, a business that develops and markets chemicals used in drilling, completion, and production operations—products designed, among other things, to prevent the loss of drilling mud.

It’s also the most temperamental part of the portfolio. The segment has proven volatile, rising and falling with oil prices, customer budgets, and regional activity. At one point, the company reported Oilfield Services revenue down 40% year over year, driven by continued weakness in Latin America production chemical activity, with no recovery expected in the coming quarters.

Management’s answer was straightforward: scale and capability through acquisitions. As CEO Patrick S. Williams put it, Innospec had indicated that growing its Oilfield Specialties business would include further acquisitions to accelerate development and build “the right technologies” and “the right market presence” in key basins. Announcing the acquisition of IOC, he said the transaction brought complementary high-quality assets and strong personnel, and that it would help Innospec offer customers a more complete slate of products across drilling, completion, stimulation, and production.

VII. The M&A Playbook: Growth Through Acquisition

Building Critical Mass

Innospec didn’t rebuild itself with one big bet. It rebuilt the way a lot of specialty chemical companies actually scale: deal by deal, capability by capability, until the portfolio starts to look like a coherent platform.

As the TEL era faded, management went shopping for what the company didn’t have enough of—products, customer relationships, technical talent, and geographic reach. The goal wasn’t to “diversify” in the abstract. It was to get to critical mass in the businesses that would define the next version of Innospec.

A cluster of deals in 2013 and 2014 shows the pattern. In September 2013, Innospec acquired Chemsil Silicones and Chemtec in Personal Care. Then it moved aggressively into oilfield chemicals: Strata Control (December 2013) in Oilfield Drilling Specialties, Bachman Services (November 2013) in Oilfield Production Specialties, and Independence Oilfield Chemicals (November 2014) in Oilfield Chemicals.

The Bachman acquisition captured the strategy in plain language. Bachman, based in Oklahoma City, was described as a leader in chemicals and services for the oil and gas industry, with combined annual sales of around $80 million. CEO Patrick Williams framed the plan as a “dual growth strategy”: grow organically with Innospec’s existing technologies, while using targeted acquisitions to accelerate the build. Bachman, he said, moved Innospec toward “critical mass,” adding technology, market positioning, and a customer-service culture that matched Innospec’s operating style.

Independence Oilfield Chemicals—often shortened to IOC—was the bigger swing. Innospec announced a definitive agreement to acquire IOC from a portfolio company of CSL Capital Management, subject to Hart-Scott-Rodino review, with an expected closing no later than October 31, 2014. IOC, based in Houston, focused on completion, stimulation, and production chemicals. Innospec described it as growing rapidly, with annualized sales of approximately $150 million, about 140 employees, and assets across major U.S. basins including Eagleford, Bakken, Barnett, Niobrara, and Marcellus. The consideration included an initial payment of approximately $100 million, representing 51% of the estimated total, and was described as roughly 7.5x IOC’s EBITDA based on recent trading performance.

Then, in 2017, Innospec pushed further into Performance Chemicals in Europe. On January 3, 2017, the company announced it had completed the acquisition of the European Differentiated Surfactants business from Huntsman.

The QGP Acquisition: Expanding Into South America

By the 2020s, the M&A playbook wasn’t just about filling product gaps—it was about building real geographic operating bases. That’s what the QGP deal did.

Innospec announced it had completed the acquisition of QGP Química Geral, a specialty chemicals company based in Brazil. Terms were not disclosed. But the strategic rationale was: QGP gave Innospec a meaningful manufacturing, customer-service, and product development footprint in South America—one of the largest and most important global markets for Innospec’s technologies. It also brought additional surfactant and specialty chemistries, with particular relevance for growth markets like Agriculture.

QGP was founded in 1992 and had about 300 employees. Innospec planned to integrate it into the Performance Chemicals business.

Management’s message was that this wasn’t a distant option on a map—it was immediate impact. After announcing the acquisition in December, the company said QGP would strengthen manufacturing, customer service, and product development in South America across multiple end markets, and that the deal was expected to be immediately accretive, adding approximately 8 cents of EPS in 2024, with further growth thereafter.

VIII. Financial Transformation and Capital Allocation

Balance Sheet Strength

By the mid-2020s, the rebuild wasn’t just visible in the product mix. You could see it in the balance sheet.

As of December 31, 2024, Innospec reported net cash of $289.2 million, up from $203.7 million a year earlier. It finished the year with $289.2 million of cash and cash equivalents and no debt—exactly the kind of financial posture that gives a specialty chemicals company room to maneuver. It can fund acquisitions when the right deal appears, keep investing organically, and still return capital to shareholders.

The operating results in 2024 showed a company that could grow earnings even when top-line conditions weren’t perfect. Full-year revenue was $1.85 billion, down 5% from 2023, while adjusted EBITDA rose 4% to $225.2 million.

Shareholder Returns

Innospec also leaned into a message of stability: it increased its annual dividend by 10% to $1.55 per share. That matters because dividends are one of the clearest signals management can send about confidence in ongoing cash generation—especially for a company with businesses as cyclical as Oilfield Services.

Management summarized the posture simply: operating cash generation was positive in the quarter, net cash ended above $289 million, and the balance sheet continued to support organic growth, further dividend increases, and flexibility for share repurchases.

Recent Performance

The quarter-to-quarter picture, though, showed how messy the transformation can look in reported numbers—even when the underlying business is doing fine.

Fourth-quarter revenue was $466.8 million, down 6% from $494.7 million in the same period the year before. But the headline was profitability: Innospec recorded a net loss of $70.4 million, or $2.80 per diluted share, versus net income of $37.8 million, or $1.51 per diluted share, a year earlier.

That swing was largely accounting and legacy-driven, not operational. The company took a $155.6 million non-cash settlement charge tied to buying out its U.K. pension scheme. Strip that out, and the core segments were still moving in the right direction: operating income was up 14% in Performance Chemicals and up 7% in Fuel Specialties.

And strategically, the pension buyout did more than distort one quarter. It removed a major legacy liability—another concrete step in cutting ties with the Octel-era baggage that had followed the company for decades.

IX. Competitive Landscape and Industry Dynamics

Market Structure

Innospec sells into markets that look deceptively simple from the outside—fuel goes in, performance improves—but the competitive map is crowded and layered.

In Fuel Specialties, management has described a field with a handful of large, scaled competitors. Many of those rivals come at the world from adjacent strongholds: lubricant oil additives or refinery process chemicals. Innospec’s distinguishing claim is that its biggest business is focused specifically on fuel.

Then there’s the long tail. Innospec also competes with a wide range of small and midsize players selling downstream of the pipeline and the refinery—into terminals, trucking fleets, shipping lines, and power stations. In other words, even if you’re not fighting a giant at the top of the market, you’re still fighting everyone, everywhere, for the next account.

Performance Chemicals is a different kind of battlefield. Personal care is a multibillion-dollar market, but Innospec doesn’t try to win it by being the cheapest, biggest surfactant supplier on earth. It plays in the niches—specialty surfactants aimed at the higher end of the market—trying to stay out of the commodity knife fight and instead differentiate by building technology aligned to where customer preferences and formulations are going next.

Cabot, Ecovyst, H.B. Fuller, Celanese, and Stepan are among the many companies that show up in the competitive set around Innospec.

The EV Threat

If the bribery scandal was an acute crisis, electrification is the slow-moving one—the kind that doesn’t blow up in a quarter, but can still rewrite an industry over a decade.

The problem is straightforward: electric vehicles don’t have combustion engines. That means they don’t need many of the engine-related chemistries that make Fuel Specialties valuable—things like fuel additives, emission catalysts, and engine oil-related products. As EV penetration rises, the market for those chemicals shrinks.

At the same time, the chemical industry’s center of gravity starts to tilt toward batteries: materials for anodes, cathodes, electrolytes, and separators. Those markets may grow quickly, but that growth doesn’t automatically help a company whose capabilities and customer relationships were built around liquid fuels.

Even in the broader ecosystem, this shift has rattled incumbents. EVs don’t require engine oil, and that has put real pressure—and real anxiety—into the parts of the oil and additives world tied to internal combustion. The question for Innospec is whether Fuel Specialties can keep compounding value as the vehicle fleet gradually changes.

And that’s what makes it feel familiar. Innospec has lived through this movie before: a core product category moving toward long-term decline. It navigated the phase-out of TEL by pivoting and diversifying. Whether it can navigate a similar arc for fuel additives—this time driven not by lead regulation, but by electrification—will define the next chapter of the company’s transformation.

X. Porter's Five Forces and Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Assessment

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate to Low In specialty chemicals, “new entrant” rarely means two people in a garage. It means a competitor that can actually formulate a product that works, manufacture it consistently, clear regulatory hurdles, and then survive the long slog of customer qualification—often measured in years, not months. Those barriers are real, especially in fuel additives. They’re lower in some corners of performance chemicals, where the path to market can be faster and more crowded.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate A lot of Innospec’s raw materials are commodity chemicals with multiple sourcing options, which keeps suppliers from holding the company hostage. The constraint comes from the other end of the spectrum: certain specialized ingredients have fewer qualified suppliers. Overall, though, Innospec has enough flexibility to avoid being boxed in.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Moderate to High In Fuel Specialties, the customer list includes giants—large oil companies with scale, alternatives, and the purchasing muscle to demand sharp pricing. Performance Chemicals tends to be a better setup: a more fragmented customer base, with value driven by formulation support and application know-how rather than pure unit cost. Across both, switching costs help. Regulatory approvals and qualification requirements make it harder for customers to rip and replace a supplier on a whim.

Threat of Substitutes: High This is the big, slow wave Innospec can’t ignore. Electric vehicles don’t need fuel additives, and that’s a direct substitute for the company’s largest segment. At the same time, substitutes show up in less dramatic ways too: new chemistries in personal care, changing customer preferences, and evolving environmental rules that can make yesterday’s “best” additive look outdated.

Competitive Rivalry: High In Fuel Specialties, Innospec faces competitors with bigger balance sheets and broader chemical portfolios. In Performance Chemicals, the rivalry is different but just as intense: it’s a fragmented market with plenty of regional players, and pricing can get ugly wherever products drift toward commodity. The defense, again, is differentiation—technical service, performance claims that hold up in the field, and the ability to solve customer-specific problems.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Moderate Innospec has real scale in fuel specialties and benefits from spreading R&D and manufacturing capabilities across a global footprint. But it’s not a scale titan. Against chemical giants like BASF or Dow, it’s still a specialist swimming in a pool with whales.

Network Economies: None There’s no real flywheel here where each new customer makes the product more valuable for the next customer. Specialty chemicals doesn’t work that way.

Counter-Positioning: Historical, Now Faded Innospec’s move away from TEL, and into higher-value specialty businesses, was a form of counter-positioning—getting out of a dying product category faster than others. But that advantage doesn’t compound forever. In many of today’s segments, Innospec is competing head-to-head with established specialty chemical leaders, not reshaping the game.

Switching Costs: Moderate to Strong This is the heart of the moat. Fuel additives often require regulatory approvals and extensive testing, and OEM specifications can lock in formulations. In personal care, customers don’t love reformulating products—especially when performance, feel, and stability are on the line. In oilfield, the switching cost is the field itself: once a chemical is proven in a basin under real conditions, customers are reluctant to gamble on an unproven alternative.

Branding: Weak to Moderate Innospec isn’t a consumer brand, so “brand” here mostly means technical reputation. That matters, but it’s not an unbreakable advantage. And the 2010 scandal did real damage—an overhang the company has spent the past fifteen years working to outgrow.

Cornered Resource: Weak There’s no single locked-up input, patent trove, or exclusive access that competitors can’t replicate. Innospec’s edge comes more from execution than from owning something no one else can touch.

Process Power: Moderate This is the quiet strength: decades of formulation work, manufacturing know-how in complex chemistries, and a technical service model that’s hard to replicate quickly. Add in a decent track record integrating acquisitions, and you get a company that can operate like a platform—even without massive scale.

Overall Competitive Assessment: Innospec’s competitive position is built mainly on switching costs and process power—getting specified, getting qualified, and then staying embedded through performance and service. But the moats aren’t permanent. The company doesn’t have overwhelming scale or brand power, and the substitution threat from electrification—plus ongoing chemistry innovation in its other markets—means it has to keep evolving to keep its edge.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

Innospec is proof that reinvention is possible—even when your original business is being regulated out of existence. It went from heavy reliance on a product the world was banning to a diversified specialty chemicals portfolio. That kind of pivot is rare, and even rarer to pull off while staying public, staying solvent, and continuing to operate globally.

The balance sheet gives it options. With close to $300 million in net cash and no debt, Innospec doesn’t need a friendly credit market to make its next move. It can fund acquisitions, put money into new plants and R&D, or keep returning capital to shareholders without having to beg the market for permission.

There’s also a real business-level advantage in what Innospec sells. In specialty chemicals, performance can matter more than volume, and customers don’t switch lightly once a formulation is working in the field. As the company itself puts it: “Frequently, a very small amount of our chemicals can create a very dramatic impact in the final application – a little goes a very long way!” Innospec is operating at global scale, too, with more than 1,300 employees across 20 countries.

And leadership continuity counts here. Patrick Williams has led the company since 2009, taking it through the bribery scandal, the compliance rebuild, and the portfolio transformation. In a business where customer trust, qualification cycles, and technical credibility take years to build, steady leadership can be an asset.

Finally, Innospec has been deliberate about where it competes: niches where technical performance can justify premium pricing, rather than commodity markets where the lowest-cost producer wins. That focus can support margins even without being the biggest player.

The Bear Case

The biggest cloud is electrification. EV adoption is a direct long-term threat to fuel additives, and Fuel Specialties is still Innospec’s largest segment. The uncomfortable parallel is obvious: regulatory and technology shifts already killed TEL. A similar force—this time the move away from combustion engines—could eventually shrink the broader market for engine-related additives.

Oilfield Services adds another layer of unpredictability. The segment can swing hard with oil prices and drilling activity, and the company has seen continued weakness in Latin America production chemical activity. Even if the rest of the portfolio is steady, this leg can make the consolidated results feel lumpy.

Scale is a constraint. Innospec competes against larger and better-resourced players—companies like Infineum and Afton Chemical, along with diversified chemical giants that can outspend it in R&D, manufacturing footprint, and commercial coverage.

The reputational shadow from the bribery scandal hasn’t fully disappeared. Compliance can be rebuilt—and Innospec has invested heavily to do so—but the historical record is permanent, and that can influence how stakeholders view the company in moments of stress.

The growth playbook also carries risk. Innospec has used acquisitions as a major tool of transformation, but M&A only works when integration works, and integration is never automatic.

And even after everything it’s done right, there’s still a structural question: does Innospec have a moat that truly lasts? Switching costs and process power help today, but they can fade as technologies change and customers’ needs evolve.

XII. Key Metrics for Investors

If you’re a long-term, fundamentals-driven investor looking at Innospec, there are three metrics that do an outsized amount of work. They don’t just tell you how the company is doing. They tell you whether the transformation is holding.

1. Fuel Specialties Operating Margin Trend

Fuel Specialties still carries the center of gravity. The job here is to keep operating margins in the 32–35% range even as electrification slowly leans on long-term volumes. If margins start to sag, that’s usually the first sign that the market is getting tougher—pricing pressure from big customers, competitors with more scale, or a product mix that’s getting less differentiated. If margins hold or improve, it’s evidence that the model works: premium formulations, real technical service, and enough operational discipline to keep efficiency gains coming without starving R&D.

2. Performance Chemicals Revenue Growth and Margin Expansion

This is the growth narrative. Performance Chemicals has to grow faster than the broader specialty chemicals market—typically low-to-mid single digits—if it’s going to be the segment that meaningfully reshapes Innospec’s future. Margins matter just as much. If acquisitions like QGP integrate smoothly and margins expand, it’s proof that management can build and run businesses outside the company’s historic fuel core. If growth stalls or margins disappoint, it raises a harder question: is this truly a second engine, or just diversification on paper?

3. Free Cash Flow Conversion

Innospec’s balance sheet gives it freedom. The constraint isn’t access to capital; it’s how effectively earnings turn into cash that can actually be used—on acquisitions, dividends, and buybacks. Free cash flow as a percentage of net income is the reality check. Strong conversion means the business is generating deployable capital, not just accounting profits. Weak conversion means something is eating the cash—working capital, capex, or integration costs—and capital allocation becomes harder no matter how “clean” the balance sheet looks.

XIII. Lessons for Founders and Investors

The Existential Adaptability Imperative

When your core product is headed for extinction, you don’t get to “optimize around the edges.” You either reinvent the company or you slowly die.

Innospec’s shift from a TEL-centered business to a diversified specialty chemicals company wasn’t a quick pivot. It took decades, and it required rewriting the company’s identity—what it sold, who it sold to, and what it wanted to be known for. Most companies caught in that kind of disruption never make it to the other side. Innospec did.

Ethics Are Non-Negotiable

The bribery scandal wasn’t a bump in the road. It was an existential threat—legal, financial, and reputational all at once.

“Corruption at Innospec was ingrained and endemic - it was institutionalised.” That wasn’t a journalist’s flourish; it was the judge’s assessment. The short-term gains from bribery in Iraq and Indonesia led to prison sentences, more than $40 million in penalties, and a corporate record that doesn’t get erased. The compliance-heavy posture the company emphasizes today wasn’t born from good intentions. It was forged in a near-death experience.

Diversification as Survival Strategy

One of the clearest takeaways from the post-TEL era is that concentration risk can be fatal.

Innospec’s three segments don’t just diversify revenue; they diversify demand drivers. When Oilfield Services gets hit by industry cycles, Performance Chemicals can still grow. Fuel Specialties can still throw off cash. That portfolio effect creates breathing room—exactly what you need to invest through downturns and keep compounding long-term value.

Niche Positioning Over Scale

In specialty chemicals, being the biggest player isn’t always the winning strategy. Being the most embedded can be.

Innospec has leaned into niches where formulation expertise and hands-on customer support matter more than brute-force scale. As the company has described it: “We operate in niches of that market. We don't go for the large volume commodity surfactants, for example, but we sell specialty surfactants into the high end of the market.” The goal is to avoid commodity knife fights and instead differentiate through technology aimed at future market trends.

M&A as Transformation Tool

Organic growth is powerful—but it can be slow, especially in markets where customer qualification takes time.

Innospec used acquisitions to accelerate the rebuild: adding capabilities in personal care, expanding in oilfield chemicals, and building positions in specialties tied to markets like agriculture. The pattern is simple: buy know-how, customers, and footprint—and then integrate it into a platform that’s less dependent on any one legacy product.

Balance Sheet Strength Enables Strategic Pivots

Reinvention is expensive. And it’s hard to transform a company when your lenders effectively sit in the boardroom.

Innospec’s debt-free position gives it strategic freedom: the ability to invest, acquire, and return capital without needing perfect market conditions. In a cyclical, competitive industry, that flexibility isn’t just nice to have. It’s a durable advantage.

XIV. Epilogue: What's Next for Innospec?

Innospec now faces another existential transition—one measured in decades, not years. The company that survived the death of leaded gasoline has to navigate the slow, uneven decline of the internal combustion engine itself.

The tone from management heading into 2025 was confident: Innospec said it was well positioned for full-year growth in Performance Chemicals and Fuel Specialties, with a sequential quarterly recovery expected in Oilfield Services.

And the QGP deal fit that same playbook. As the company put it: "This acquisition aligns with our long-stated M&A focus to further strengthen our Performance Chemicals segment and add a manufacturing base in South America. Following this acquisition, we continue to have an extremely strong, debt-free balance sheet and remain well-positioned for additional M&A, consistent shareholder returns, and organic growth investments."

Electrification is the familiar part of the story: a core category facing a long-term shrinking end market. The difference is pace. TEL was regulated out of existence. Internal combustion will fade more slowly, and in many markets it will stay dominant for a long time. Even in decline, that can still be a very good business—if you can protect margins, stay embedded with customers, and keep innovating as fuel formulations evolve.

That’s why Performance Chemicals matters so much. Personal care, home care, and agriculture run on totally different demand drivers than fuel additives. They’re less exposed to EV adoption, and they give Innospec a path to grow into a future that doesn’t depend on what powers the car.

The open question is whether Innospec can turn that diversification into something more than survival—durable competitive advantage in specialty chemicals. Or whether it remains a well-run, technically capable company in markets where moats are thin, switching costs can erode, and scale still matters.

What’s hard to argue with is resilience. This is a company that began by manufacturing a product that poisoned generations, then nearly destroyed itself trying to extend that legacy through corruption, and still managed to rebuild into a modern specialty chemicals business. Whether that resilience becomes a lasting edge—or just a talent for getting through the next disruption—will define the next chapter.

For investors, Innospec is simultaneously a transformation case study, proof that corporate redemption can be real, and a reminder that ethical failure is never “priced in” until it is. The next act—managing the EV transition while building something that can endure—will determine whether this survival story ultimately becomes a long-term compounding story.

Further Reading and Resources

If you want to go deeper—into the filings, the courtroom record, and the reporting that shaped how the world understood this company—these are the best starting points:

- Innospec 10-K Annual Reports (2010-2025) - SEC filings that document the post-scandal rebuild and the shift into a diversified specialty chemicals portfolio

- DOJ/SEC/SFO Settlement Documents (March 2010) - The primary-source record of the coordinated global resolution and the underlying conduct

- Lord Justice Thomas sentencing judgment (March 2010) - The U.K. court’s unusually blunt view on corporate corruption and the limits of “global settlement” deals

- The Guardian investigation into Innospec bribery (June 2010) - Reporting that helped bring the scandal’s real-world consequences into focus

- EPA history of the leaded gasoline phase-out - The regulatory arc that made TEL a dying business in the first place

- Company earnings call transcripts (2020-2025) - How management framed the strategy, segment performance, and capital allocation in real time

- Associated Octel historical archives - Background on the corporate predecessor and the origins of the TEL business

- Stanford FCPA Enforcement Action Database - A structured case summary and references for the Innospec enforcement actions

- Innospec Sustainability Reports - How the modern company presents its environmental and social priorities

- Academic research on tetraethyl lead’s health impacts - The scientific foundation for why TEL became one of the most consequential industrial toxins of the last century

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music