Inhibikase Therapeutics: The Audacious Quest to Crack Parkinson's Disease

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

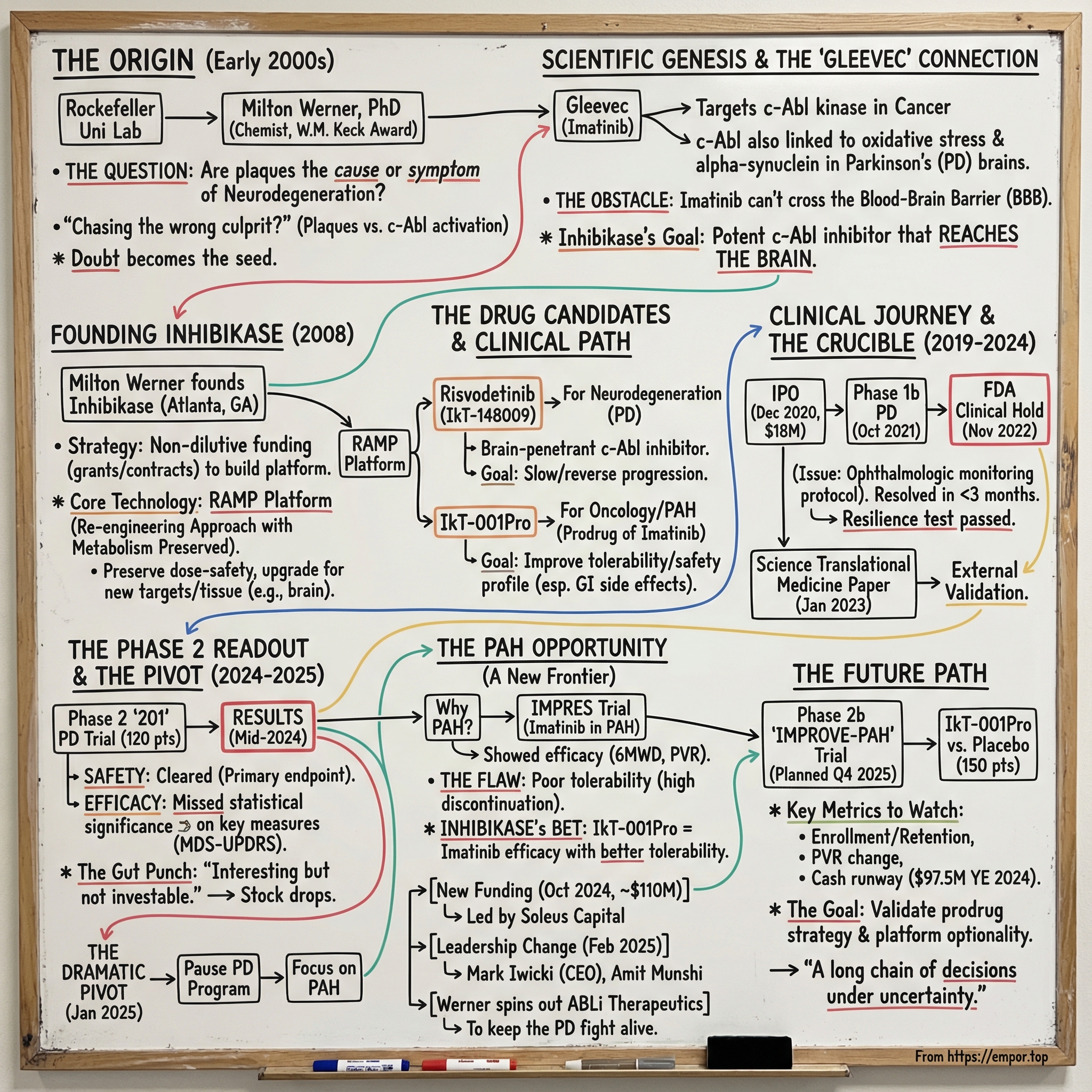

Picture The Rockefeller University in the early 2000s: a lab humming with experiments, late nights, and the kind of stubborn curiosity that only shows up when the question feels impossible.

In the middle of it is Milton Werner—a chemist with serious momentum, including a $1 million Distinguished Young Scholars Award from the W.M. Keck Foundation—staring down a problem that had trapped neuroscience for decades. What if the field had been chasing the wrong culprit in Parkinson’s disease?

Back then, the dominant story was simple and seductive. Parkinson’s patients had these distinctive protein aggregates in their brains—plaques—so the plaques must be the disease. As Werner later put it, “Diseases like Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s have these protein aggregates which we often refer to as plaques, and the idea was that these plaques only showed up in disease, so we needed to just figure out how to get rid of them.” But what bothered him was what that logic assumed. “There was no guarantee that those misfolded proteins, or plaques, were actually causing disease.”

That one doubt—small on paper, radioactive in practice—eventually became the seed of Inhibikase Therapeutics. Over the next sixteen years, it would grow into a clinical-stage biotech willing to bet that the breakthrough playbook from targeted cancer drugs could be re-aimed at neurodegeneration. Not to manage symptoms, but to slow progression—and maybe even reverse functional loss.

It’s also a story told with eyes wide open about the odds. “Treating major CNS disease, which encompasses Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, ALS, etcetera, has been a 100% failure business for forty years,” Werner said. “We persevere because our outcomes are very strong.”

But this isn’t just a company profile. It’s a tour through the hardest parts of biotech: the gap between beautiful animal data and messy human biology, the market’s tolerance for scientific uncertainty, the regulatory stress test of an FDA clinical hold, and the gut-punch moment when Phase 2 results force a rethink. Inhibikase would ultimately face that exact moment—when risvodetinib’s path in Parkinson’s dimmed, and the company had to consider a pivot that would have sounded unthinkable at the outset.

To understand how they got there, you have to start with Werner himself. He earned his PhD in chemistry from the University of California, Berkeley, trained at the National Institutes of Health, and joined Rockefeller in 1996 as a head of laboratory. From 1996 to 2007, he ran a multidisciplinary research program that pushed into the molecular mechanics of neurodegeneration—work that would take nearly two decades to truly test in humans, and would eventually reshape the company built around it.

II. The Scientific Genesis: From Gleevec to Neurodegeneration

To understand Inhibikase, you first have to understand Gleevec—one of the most celebrated targeted cancer therapies ever made. Its active ingredient, imatinib, shuts down the Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase, a malfunctioning signal that drives certain cancers. Approved in the U.S. in 2001, it helped turn chronic myelogenous leukemia from a near-certain fatal diagnosis into something many patients could live with long-term.

Gleevec’s origin story is biotech at its best: identify the molecular villain, then design a drug to neutralize it. After the Philadelphia chromosome mutation and the hyperactive Bcr-Abl protein were linked to disease, researchers screened chemical libraries for inhibitors. They landed on a lead compound—2-phenylaminopyrimidine—and then iterated, adding chemical groups to improve binding until it became imatinib.

So what does a leukemia drug have to do with Parkinson’s?

The connection runs through a related enzyme: c-Abl, a widely expressed, non-receptor tyrosine kinase that can be activated by oxidative stress. And oxidative stress is one of the major pathological mechanisms implicated in neurodegenerative disorders. If c-Abl activation was part of the machinery that helped kill neurons, then inhibiting c-Abl might do more than treat symptoms—it might slow, or even change, the underlying disease process.

As the biology came into focus, the story got more intriguing. In mouse studies, introducing lentiviral c-Abl into the substantia nigra increased both monomeric and aggregated alpha-synuclein. That accumulation was also associated with c-Abl activation—suggesting a reinforcing loop. And importantly, a similar association between c-Abl activation and alpha-synuclein accumulation showed up in human postmortem Parkinson’s striatal specimens.

The takeaway was hard to ignore: “All these suggest that preventing c-Abl activation may be a promising disease-modifying therapy.”

But there was a catch big enough to stop the whole idea in its tracks.

Imatinib was built to treat cancer in the body, not disease in the brain. And for a c-Abl inhibitor to work in Parkinson’s, it would need to cross the blood-brain barrier. That protective filter—so good at keeping toxins out—also keeps many drugs out, including commonly used c-Abl inhibitors like imatinib and nilotinib. Researchers had shown that imatinib could inhibit c-Abl’s deleterious effects on parkin by preventing its phosphorylation and preserving its protective function. But with limited brain bioavailability, the protective effect in vivo could be severely constrained simply because the drug couldn’t get where it needed to go.

By the mid-2010s, the preclinical evidence around c-Abl inhibition in Parkinson’s had piled up, even if it wasn’t yet proven in humans. In animal models, c-Abl inhibitors reduced phosphorylated alpha-synuclein and Lewy pathology, reduced mitochondrial dysfunction, and rescued dopamine neurons and motor function in a dose-dependent manner. Multiple inhibitors—imatinib, nilotinib, bafetinib, radotinib, and newer molecules in clinical development—showed that c-Abl inhibition could act prophylactically and/or therapeutically against Parkinson’s-like neurodegeneration in animals.

So the scientific opportunity was clear. The obstacle was just as clear: take the foundational logic of Gleevec—potent, targeted kinase inhibition with a known safety and pharmacology profile—and engineer it into something that could actually reach the brain.

That’s the opening Inhibikase was built to attack.

III. The Founder's Journey: Milton Werner & The Birth of Inhibikase

Milton Werner didn’t start as a biotech CEO. He started as a scientist who liked hard problems—and who built his career by crossing boundaries most researchers stay inside.

From September 1996 through June 2007, he led the Laboratory of Molecular Biophysics at The Rockefeller University in New York City. Those years became his proving ground: a place where he could pull chemistry, physics, and biology into one integrated way of thinking about disease. Across his scientific career, Werner worked on questions ranging from fundamental biology to the mechanistic basis of certain leukemias and lymphomas—and, eventually, how to build therapeutics that might halt, and even reverse, functional loss in neurodegenerative disease.

His path there was classic academic horsepower. He earned his PhD in chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley, trained at the National Institutes of Health, and then joined Rockefeller in 1996.

But the key turn in the story is that Werner didn’t just publish papers and stop. After leaving Rockefeller, he took a short but important detour into industry—serving as Vice President of Discovery Research at Celtaxsys, Inc. from May 2007 to August 2008. It was a brief stint, but it gave him a firsthand look at how drug development changes when you’re responsible not just for the science, but for the timeline, the budget, and the regulatory path.

Then, in 2008, he made the leap. Werner founded Inhibikase Therapeutics to develop novel treatments for infections and neurodegenerative disorders of the central nervous system, including Parkinson’s disease. He based the company in Atlanta, Georgia—well outside the gravitational pull of Boston and San Francisco. That distance mattered. It shaped everything from hiring to fundraising to how the company learned to operate with a little more grit and a little less assumption that capital would always be there on demand.

Werner also brought credibility—real, compound-interest credibility. Over his career he authored more than 70 research articles, reviews, and book chapters, and lectured internationally on his work. He collected major recognition along the way, including the Naito Memorial Foundation Prize, a Young Investigator Award from the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Foundation, a Research Chair from the Brain Tumor Society, and that $1 million Distinguished Young Scholars in Medical Research Award from the W. M. Keck Foundation.

Still, for all the Parkinson’s framing in the origin story, Inhibikase didn’t immediately become a Parkinson’s company.

That shift came later. Werner put it plainly: it wasn’t until 2015 that Inhibikase, as a company, formally got involved in Parkinson’s. “We got involved because we made discoveries in certain medications that inhibit signaling enzymes like c-Abl and that we could model diseases like Parkinson’s.”

That 2015 pivot mattered because it defined what Inhibikase would and wouldn’t be. The easy path would have been to do what much of the field was doing—take an existing cancer drug, try it in neurodegeneration, and hope the biology held up. Inhibikase took the harder route. Instead of simply repurposing, it focused on building new molecules engineered for brain penetration, while preserving the favorable metabolic characteristics that made imatinib such a landmark in the first place.

To pull that off, they needed something most early biotechs don’t have: time. And Werner was unusually explicit about how they bought it. Inhibikase, he said, had been able to fund activities with non-dilutive capital through federal contracts and grants “in ways that many other companies do not.” “That makes Inhibikase a stronger company,” he added, “and hopefully we will be able to support our activities until we reach those important medical milestones.”

That strategy wasn’t just nice-to-have; it was survival. Disease modification in Parkinson’s had become one of biotech’s graveyard indications—a place where even the biggest pharmaceutical companies had spent heavily and still come up empty. If Inhibikase was going to take a real shot, it had to stay capital-efficient long enough to generate clinical data that could carry the story on more than hope.

By the late 2010s, Werner had assembled the ingredients: a scientific platform, non-dilutive support, and a clear hypothesis to test in humans. Now came the part that breaks companies—the translation step, where animal-model certainty collides with human biology and the clock starts ticking for real.

IV. The RAMP Platform & The Drug Candidates

At the center of Inhibikase is a simple-sounding promise with brutally hard execution: take a proven drug concept, re-engineer it so it can do a new job, and don’t break the part that made it safe in the first place.

That’s what the company calls RAMP—short for “Re-engineering Approach with Metabolism Preserved.” In plain English, the idea is to preserve the relationship between dose and safety that’s already been learned the hard way in humans, while upgrading the molecule for a new therapeutic target or a new tissue—like, say, the brain.

RAMP produced two lead programs that share the same scientific roots but aim at very different diseases. The first was risvodetinib (IkT-148009), built for neurodegeneration. The second was IkT-001Pro, a prodrug strategy built around imatinib for oncology—and, later, pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Risvodetinib was designed as a potent, selective small molecule meant for chronic use: a once-daily oral drug aimed at the biological mechanism driving Parkinson’s disease, with the ambition of halting progression and reversing functional loss. Mechanistically, it’s built to block Abl kinase activation—a clinically validated target—with the goal of protecting, and potentially restoring, dopamine-secreting neurons in both the brain and the gastrointestinal tract by restoring neuroprotective mechanisms.

And critically, risvodetinib was engineered to solve the problem that made imatinib a dead end in Parkinson’s: the blood-brain barrier. Where imatinib couldn’t reach therapeutic levels in the CNS, risvodetinib was designed for brain penetration while still needing to be tolerable enough for long-term, everyday dosing.

In animals, the payoff looked almost too good to be true. Studies suggested that Abl inhibition didn’t just slow Parkinson’s-like decline; it could reverse functional deficits even in established disease models. If that kind of reversal ever showed up in people, it wouldn’t be an incremental neurology drug. It would be a category-defining event.

IkT-001Pro, meanwhile, attacked a different bottleneck: tolerability. It’s a prodrug formulation of imatinib mesylate, developed to improve the safety profile of the first FDA-approved Abelson kinase inhibitor—imatinib, marketed as Gleevec. Imatinib is widely used in cancers driven by Abl kinase mutations in the bone marrow, and in gastrointestinal cancers linked to c-Kit and/or PDGFRa/b mutations.

In preclinical studies, IkT-001Pro was reported to be up to 3.4 times safer than imatinib in non-human primates, with fewer of the burdensome gastrointestinal side effects that can come with oral dosing.

Strategically, the prodrug approach also offered a classic biotech de-risking move: keep the active ingredient that regulators already understand, then prove you’ve made it easier to live with. Inhibikase believed this could support a faster path through the FDA under the 505(b)(2) pathway.

That thesis got an early signal boost in September 2018, when imatinib delivered as IkT-001Pro received Orphan Drug Designation for stable-phase chronic myelogenous leukemia—an early regulatory win that added exclusivity advantages and validated the premise that the prodrug concept was worth serious attention.

And in the background, even then, RAMP’s real value was optionality. Two candidates, multiple indications, one core capability. That flexibility would matter later, when the company faced the kind of clinical reality check that forces biotechs to either adapt fast—or run out of road.

V. Key Inflection Points: The Clinical Journey (2019-2024)

Once risvodetinib moved from theory to patients, the story started to look like biotech always does: long stretches of careful progress, punctuated by sudden, high-stakes moments where everything can change in a day.

That reality hit in late 2020, when Inhibikase stepped onto the public markets. Its common stock began trading on the Nasdaq Capital Market on December 23, 2020 under the ticker symbol “IKT.” Five days later, on December 28, the company closed its initial public offering: 1.8 million shares at $10 per share, raising $18 million in gross proceeds before fees and expenses.

It wasn’t a flashy, blow-the-doors-off debut. The shares priced at the low end of the expected range, a reminder that everyone involved understood what they were buying into. Parkinson’s wasn’t just competitive—it was where promising mechanisms went to die. Still, that IPO capital mattered. It gave Inhibikase the runway to push beyond grant-funded preclinical work and into the kind of clinical development that actually answers the question.

In October 2021, the company took its first real step into that arena: dosing the first patient in a Phase 1b trial of risvodetinib in people with Parkinson’s disease. It was a randomized, placebo-controlled study designed to do what early trials are supposed to do—establish safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics across multiple dose levels before anyone starts talking seriously about efficacy.

And then came the moment every biotech team dreads.

In November 2022, the FDA unexpectedly placed IkT-148009 on clinical hold. The market reacted fast, and painfully—shares fell as investors tried to price in the thing no one wants to hear this late in the process: stop.

The issue wasn’t abstract. The FDA asked for additional ophthalmologic monitoring—specifically, measurement of visual acuity and examination of the cornea and lens. Inhibikase had already planned retinal monitoring, including the retina, macula, and fundus, but the agency wanted the protocol tightened and expanded.

The company responded, submitting a Complete Response and Amendment dated December 21, 2022, followed by further commitments on January 20, 2023. The hold lasted about two and a half months—brief in the context of drug development, but long enough to test management, morale, and credibility.

When the FDA lifted the full clinical hold, it did more than restart the trial. It showed Inhibikase could navigate the regulatory process under pressure—an essential capability if the program was ever going to reach patients at scale.

Right around that same time, the science got an external spotlight. In January 2023, Inhibikase announced the publication of “The c-Abl inhibitor IkT-148009 suppresses neurodegeneration in mouse models of heritable and sporadic Parkinson’s disease” in Science Translational Medicine. For a company whose whole bet depended on a mechanistic story, the paper provided a kind of independent reinforcement that investors and clinicians pay attention to: this wasn’t just internal conviction.

Then came the real test: Phase 2.

In 2024, Inhibikase completed enrollment in its Phase 2 “201” trial in untreated Parkinson’s patients, a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, multi-center, placebo-controlled study evaluating three dose levels. The trial enrolled 120 participants across 32 U.S. sites, and the company expected results in the fourth quarter of 2024. By mid-June 2024, 69 participants had already completed the 12-week dosing period.

When the readout arrived, the safety story held up. Across secondary outcome assessments, most measures numerically trended in risvodetinib’s favor versus placebo. Completion was strong—95% of participants finished the full 12-week regimen—and risvodetinib was generally well tolerated.

But the headline was the headline for a reason: the drug cleared the primary endpoint of safety and tolerability, yet the efficacy signals did not reach statistical significance on the key hierarchical measure.

In Parkinson’s drug development, that’s the line between “interesting” and “investable.” And it set up the next phase of Inhibikase’s story—where years of focus suddenly had to compete with a new question: if Parkinson’s wasn’t yielding clear proof, where else could this platform win?

VI. The Dramatic 2024-2025 Pivot

By January 2025, Inhibikase was forced to make the kind of decision that defines a biotech’s identity.

After the Phase 2 study in untreated Parkinson’s patients, the company said in an SEC filing that risvodetinib had done what it needed to do on safety and tolerability—but it hadn’t delivered a clear efficacy win. Inhibikase paused development of the Parkinson’s program and began looking for “strategic options” for the asset.

On the safety side, the results were reassuring: adverse events looked similar to placebo in both frequency and severity, and the company reported no severe treatment-related adverse events.

On the efficacy side, the central problem was blunt. Risvodetinib did not show improvement versus placebo on the top hierarchical efficacy measure: the sum of Parts 2 and 3 of the Movement Disorder Society Universal Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, or MDS-UPDRS, across dose groups.

Still, the data weren’t empty. The company reported improvement at the 100 mg dose in Part 2 of the MDS-UPDRS and at the 50 mg dose on the Schwab & England Activities of Daily Life Scale. And then there was the most tantalizing piece: biomarker work tied to alpha-synuclein pathology using skin biopsy. Inhibikase described a dose-dependent reduction in neuronal alpha-synuclein deposition in cutaneous nerve fibers across doses.

That’s the frustrating paradox of neurodegeneration drug development in one paragraph: signals that suggest biological activity, without a matching change in how patients function—at least not over a 12-week window. Whether more time, a different patient population, or different dosing could have changed the outcome remained uncertain.

The market didn’t wait around for the academic debate. In after-hours trading following the disclosure, Inhibikase’s stock dropped more than 19%, falling to $2.26 per share from $2.80 at the prior close. Another reminder that Parkinson’s is where good theories go to be interrogated by reality.

But the twist in this story is that the company had already been building an off-ramp.

Months earlier, on October 9, 2024, Inhibikase announced the pricing of an approximately $110 million private placement financing, before fees and expenses. The stated use of proceeds: fund the initiation of a Phase 2b trial in pulmonary arterial hypertension, plus general corporate purposes.

The financing closed on October 21, 2024, with approximately $110 million raised from the sale of common stock and accompanying warrants. If those warrants were fully exercised for cash, the total potential financing could reach approximately $275 million. This was the war chest meant to fund the Phase 2b “702” trial in PAH.

The round was led by new investor Soleus Capital, with participation from new investors including Sands Capital, Fairmount, Blackstone Multi-Asset Investing, Commodore Capital, Perceptive Advisors, ADAR1 Capital Management, BSQUARED Capital, Nantahala Capital, Stonepine Capital Management and Spruce.

Then came the leadership handoff. Inhibikase appointed Mark Iwicki as Chief Executive Officer, replacing founder Dr. Milton H. Werner, effective February 14, 2025. Iwicki brought more than 30 years of biopharmaceutical industry experience. The company also referenced Amit Munshi, a 30-year industry veteran who is currently CEO of Orna Therapeutics and former President, CEO and board member of ReNAgade Therapeutics.

A week later, on February 21, 2025, Inhibikase completed its merger with CorHepta Pharmaceuticals, making CorHepta a wholly owned subsidiary. The deal included a $15 million payment in company shares, with additional shares tied to future milestones.

And Werner didn’t retire—he redirected.

Milton Werner, Ph.D., became founder and CEO of newly launched ABLi Therapeutics, aiming to develop risvodetinib as a disease-modifying therapy for Parkinson’s and other diseases of the Abelson Tyrosine Kinases. ABLi licensed both risvodetinib and the RAMP platform from Inhibikase.

Werner had led the Atlanta-based company for more than 16 years before departing in February. “The path for neuroscience needed its own financial support and focused effort, and today we announced ABLi as that focused effort,” he told Fierce Biotech.

Notably, the split was described as amicable. Munshi said, “I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to Milton, the scientific founder of Inhibikase, for his invaluable contributions, including his groundbreaking invention of IKT-001Pro. Under Milton’s visionary leadership, the Company has achieved significant scientific milestones, and his continued guidance will remain a cornerstone of our future progress.”

In other words: one company pivoted toward PAH with fresh capital and new leadership, while the founder spun out to keep the Parkinson’s bet alive—just in a different vehicle.

VII. The PAH Opportunity: New Frontiers

The pivot to pulmonary arterial hypertension wasn’t a Hail Mary. It was a return to a clue the field already had: imatinib had shown real signal in PAH—just not in a form patients could stay on.

That signal came from the Phase 3 IMPRES trial. It enrolled 202 people with PAH, many already on heavy standard-of-care—about 41% were on three PAH therapies, with the rest on two. At 24 weeks, imatinib produced a placebo-corrected improvement in six-minute walk distance of 32 meters, and that benefit held up in an extension study for patients who stayed on the drug. The trial also showed improvements in hemodynamics, including reductions in mean pulmonary artery pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance.

But the same dataset carried the fatal flaw: tolerability. Even with clear efficacy, only about 43% of patients were still taking imatinib at six months. Severe adverse events and significant side effects drove a discontinuation rate high enough that the risk-benefit profile didn’t pencil out broadly, and off-label use in PAH has been discouraged.

That’s exactly where Inhibikase thought it could play a different game.

IkT-001Pro is Inhibikase’s prodrug formulation of imatinib, designed to make the same active ingredient easier to live with—especially by reducing the burdensome gastrointestinal effects associated with oral dosing. The company’s bet is straightforward: if you can preserve imatinib’s efficacy in PAH but dramatically improve tolerability, you might finally unlock a therapy that works for far more patients than the original could.

In the previously published Phase 3 data, imatinib was reported to deliver a clinically meaningful improvement in six-minute walk distance of roughly 40 meters, reduce pulmonary vascular resistance by more than 300 dyne-sec/cm, and improve other measures of heart health, with approximately 30% of participants getting better when imatinib was added to standard of care at 400 mg once daily. Inhibikase argues that IkT-001Pro has the potential to offer that same therapeutic upside with a more manageable safety and tolerability profile. In preclinical studies, IkT-001Pro was shown to be as much as 3.4 times safer and/or better tolerated than imatinib in non-human primates.

Regulators cleared the next step: the FDA IND-cleared the 702 trial evaluating IkT-001Pro in PAH for Phase 2b clinical entry on September 9, 2024.

And under new leadership, the company set expectations publicly. “During our third quarter of 2025, we continued to position the Company to advance IKT-001 toward a late-stage clinical trial in PAH,” said Mark Iwicki, Chief Executive Officer of Inhibikase. “We expect to initiate our Phase 2b clinical study of IKT-001, our prodrug of imatinib mesylate, in PAH during the fourth quarter of 2025.”

That proposed Phase 2b IMPROVE-PAH study is planned as a multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of approximately 150 PAH participants.

Commercially, PAH is smaller than Parkinson’s—but it’s a rare disease category with established pricing and a stubbornly high unmet need. Even with meaningful therapeutic advances that have improved long-term survival, PAH still has no cure. Most treatments have historically focused on vasodilation, sometimes with additional downstream and off-target antimitogenic effects. The promise of targeting the disease biology more directly is what keeps imatinib—and now IkT-001Pro—on the table.

As of December 31, 2024, Inhibikase reported $97.5 million in cash, cash equivalents, and marketable securities. It’s a meaningful runway for the Phase 2b push—but if IkT-001Pro earns a path into larger, later-stage trials and beyond, the company will likely need more capital to get all the way to Phase 3 and potential commercialization.

VIII. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

If you zoom out, Inhibikase reads like a case study in how biotech actually gets made: not by one breakthrough moment, but by a long chain of decisions under uncertainty—scientific, regulatory, and financial.

The Academic-to-Entrepreneur Arc: Werner’s path from Rockefeller lab head to sixteen-year biotech CEO captures both the upside and the fragility of founder-led drug development. Deep domain expertise can unlock contrarian hypotheses—like his view that plaques don’t cause Parkinson’s, but instead spark a downstream cascade worth targeting. But the jump from academic validation to clinical proof is where most programs break. Many “works in mice” stories never translate in humans. Werner’s move to keep pursuing risvodetinib through ABLi suggests the scientific conviction is still there; what changed was the corporate structure and the capital plan around it.

Platform Value in Biotech: RAMP didn’t just produce a molecule—it produced options. That mattered when risvodetinib’s Phase 2 efficacy signals didn’t land cleanly. Without IkT-001Pro and a credible PAH path, that miss could have been existential. Platform-driven companies can sometimes absorb setbacks that would wipe out a single-asset story. But the resilience isn’t free. Here, the pivot came with real cost: a new strategic center of gravity, and the founder stepping aside as CEO.

The Clinical Hold Crucible: Clinical holds are a stress test for any biotech, and not just scientifically. Inhibikase got its hold lifted based on its Complete Response and Amendment dated December 21, 2022, and further commitments made on January 20, 2023 around ophthalmologic monitoring. The key detail is the timing: the hold was resolved in under three months. That kind of turnaround signals operational competence—and it builds credibility with regulators that can matter just as much as any single dataset.

Non-Dilutive Funding Strategy: Werner emphasized that Inhibikase funded work with non-dilutive capital through federal contracts and grants “in ways that many other companies do not,” adding, “That makes Inhibikase a stronger company.” The tradeoff is baked in: non-dilutive funding can preserve ownership through the long preclinical grind, but it can also mean moving slower than competitors once the race shifts to the clinic.

Knowing When to Pivot: The 2024–2025 decision to prioritize PAH over Parkinson’s was more than a strategy tweak—it was a recognition that years of conviction hadn’t yet produced definitive clinical proof. Those moments don’t just test a pipeline; they test relationships, culture, and identity. Inhibikase’s outcome was unusual and revealing: the company pivoted with new leadership and fresh funding, while Werner spun out to keep the Parkinson’s bet alive elsewhere.

IX. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH

In neurodegeneration, c-Abl inhibition has been a crowded neighborhood. Imatinib, nilotinib, bafetinib, radotinib, and newer inhibitors have all shown the same basic thing in animal models: hit c-Abl, and you can blunt—or sometimes even reverse—Parkinson’s-like pathology. That’s enough to attract smart scientists and well-funded teams.

But it’s also enough to scare people off. The field is littered with programs that looked great preclinically and then failed to produce clear benefits in humans. That history raises the bar for anyone thinking about entering the space—because it’s not just about making a potent inhibitor. It’s about proving meaningful clinical impact in a disease where trials are slow, endpoints are noisy, and placebo effects are real.

In PAH, the barriers are higher. The regulatory path is more established, but the execution is specialized: the trials, sites, and patient management are built around a relatively small, expert ecosystem. And while the IMPRES imatinib data is public, copying Inhibikase’s bet—keep the efficacy, fix the tolerability—requires real chemistry, formulation, and manufacturing capability, not just a good idea.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Suppliers don’t have much leverage here. CROs and manufacturing partners compete aggressively, and small-molecule API manufacturing for kinase inhibitors is a mature, well-served market. Clinical trial sites can be sourced through multiple networks, which helps keep Inhibikase from being boxed in by any single vendor relationship.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

If Inhibikase gets a drug approved, the buyers with the most power won’t be patients—they’ll be payers. Insurers, pharmacy benefit managers, and government programs shape access through formularies, prior authorizations, and reimbursement decisions. For a specialty drug, that leverage can dictate commercial outcomes.

The counterweight is clinical value. In PAH, premium pricing is accepted when a therapy shows clear benefit. If IkT-001Pro can deliver a real tolerability improvement that keeps patients on drug longer—and translates into better outcomes—then Inhibikase’s negotiating position gets materially stronger.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH for Parkinson's, MODERATE for PAH

For Parkinson’s, the substitute threat is high even though there are no disease-modifying therapies on the market. That’s the paradox: the unmet need is enormous, so everyone is trying something—gene therapy, antibodies, other kinase inhibitors, and GLP-1 receptor agonists among them. Even if c-Abl is a real contributor to disease biology, it’s competing with a long list of other plausible mechanisms.

For PAH, substitutes are more structured. There’s an established standard of care—prostacyclin analogs, endothelin receptor antagonists, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors—that treats symptoms and extends survival, but doesn’t reliably stop progression. That leaves room for drugs that act more directly on disease remodeling. Sotatercept’s recent approval is a strong signal that the market, regulators, and clinicians are ready to embrace anti-proliferative, disease-modifying approaches when the data is compelling.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

Rivalry is intense, especially in neurodegeneration. Even within the narrow slice of c-Abl inhibition, multiple players have pushed programs forward. And more broadly, large pharma and biotechs keep cycling back into Parkinson’s despite decades of disappointment—because the prize is enormous if anyone cracks it.

Hamilton's Seven Powers

Scale Economies: NOT APPLICABLE

Inhibikase is still pre-commercial. It doesn’t have manufacturing or distribution scale advantages—yet.

Network Effects: NOT APPLICABLE

Drug development doesn’t compound in value the way consumer networks do. One more “user” doesn’t make the product better for everyone else.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

IkT-001Pro creates a subtle counter-positioning advantage. Big incumbents with established kinase inhibitor franchises may have little incentive to champion an improved formulation that implicitly spotlights the limitations—especially safety and tolerability—of earlier versions. That reluctance can open a window for a smaller company to move faster and tell a cleaner story.

Switching Costs: HIGH (if approved)

If a therapy becomes part of long-term disease management, switching is painful. Risvodetinib was designed for chronic, once-daily use. In PAH, once a patient is stable on a regimen, physicians tend to avoid changes unless there’s a strong reason. That inertia becomes a form of switching cost—assuming the drug earns its place in the regimen to begin with.

Branding: LOW

Brand matters less than data. In rare diseases especially, physician confidence, guideline placement, and payer access do far more work than consumer awareness.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

RAMP—plus the internal know-how built over years of kinase-inhibitor metabolism work—is a real resource competitors can’t instantly replicate. But there’s a wrinkle: Werner’s departure and the creation of ABLi adds complexity around where expertise sits and how the competitive dynamics evolve, even if the intellectual property is clearly licensed and defined.

Process Power: MODERATE

Inhibikase’s process advantage is that it’s been playing the same game, in the same molecular universe, for a long time. Deep familiarity with kinase inhibitor metabolism and tolerability can translate into more predictable development decisions. IkT-001Pro’s preclinical profile—reported to be as much as 3.4 times safer than imatinib in non-human primates, with reduced gastrointestinal side effects—fits that narrative: not just a new molecule, but an attempt to engineer risk out of something the clinic already understands.

X. Bear Case vs. Bull Case

Bear Case

Efficacy Translation Risk: The scar tissue from Parkinson’s is real. Risvodetinib looked powerful in animals, cleared safety and tolerability in humans, and still didn’t deliver a clean efficacy win in a midstage trial. PAH has a better starting point because imatinib has already shown efficacy there—but IkT-001Pro’s core promise is improved tolerability, and that remains a hypothesis until it’s demonstrated in larger, longer studies.

Competitive Landscape: PAH is active, competitive territory. Sotatercept’s approval both validates anti-proliferative, disease-modifying approaches and raises expectations for what “good” looks like. And Inhibikase isn’t the only team trying to solve imatinib’s tolerability problem; alternative approaches, including inhaled imatinib formulations from other companies, could compress differentiation.

Founder Departure Complexity: Werner’s departure and the launch of ABLi add layers of uncertainty—around competitive dynamics, what expertise sits where, and how the two stories evolve in parallel. While ABLi licensed risvodetinib and the RAMP platform from Inhibikase, the licensing terms haven’t been fully disclosed, which can leave investors bracing for future friction.

Clinical Development Risk: There’s a reason kinase inhibitors come with warnings. Chronic peripheral dosing of FDA-approved c-Abl inhibitors in CML has been associated with cardiovascular, pulmonary, GI-associated, and liver adverse events. IkT-001Pro is designed to improve tolerability, but the safety profile for long-term dosing in non-oncology populations still needs to be proven in the clinic.

Capital Intensity: Drug development is expensive and rarely linear. Inhibikase reported $97.5 million in cash, cash equivalents, and marketable securities as of December 31, 2024—enough to move through Phase 2b, but not necessarily enough to fund Phase 3 and commercialization without additional financing that could be dilutive, especially in uncertain capital markets.

Bull Case

Well-Capitalized for Near-Term Milestones: In October 2024, Inhibikase closed a private placement with gross proceeds of about $110 million to support advancing IkT-001Pro toward late-stage development in PAH. If the accompanying warrants are exercised for cash, total gross proceeds could rise to roughly $275 million—meaningfully extending the runway at a moment when momentum matters.

Proven Efficacy Foundation: PAH isn’t a blank-sheet biology bet. The IMPRES trial provided evidence that imatinib can work in PAH, including a clinically meaningful improvement in six-minute walk distance of around 40 meters and a reduction in pulmonary vascular resistance of more than 300 dyne-sec/cm. The problem wasn’t whether the mechanism had power—it was whether patients could stay on the drug. If IkT-001Pro makes imatinib meaningfully easier to tolerate, the upside is straightforward.

Experienced Management: With Mark Iwicki as CEO, the company is now led by an operator with deep industry experience. In a rare-disease category like PAH—where trial execution, site networks, and commercialization planning are specialized—that kind of leadership can be a real advantage.

FDA Engagement: The company received its Study May Proceed letter for the Phase 2b trial in September 2024. That doesn’t guarantee success, but it does remove near-term regulatory ambiguity and helps make the development timeline more legible.

Platform Optionality: A win in PAH would do more than validate a single program—it would validate the broader idea behind RAMP: take a molecule with known human efficacy, re-engineer it without losing what made it work, and expand where it can be used. If IkT-001Pro delivers, it could open doors to other indications where imatinib has shown activity but side effects have capped adoption, including additional pulmonary conditions and other non-oncology uses.

Key Metrics to Monitor

If you’re tracking Inhibikase from here, the story turns into a waiting game—with a few very specific telltales that will show whether the PAH pivot is working.

1. Phase 2b enrollment rate and retention: The planned IMPROVE-PAH trial, targeting about 150 participants, is the first real test of IkT-001Pro in a PAH population. Enrollment speed is a proxy for whether sites, physicians, and patients buy into the premise. Retention is the point of the spear: IkT-001Pro exists to solve tolerability. In the original IMPRES trial with standard imatinib, only about 43% of patients were still on treatment at six months. Beating that benchmark is a core part of the bull case.

2. Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) change from baseline: PVR is the primary hemodynamic endpoint for the Phase 2b portion, and it’s one of the cleanest reads on whether the drug is changing the underlying disease physiology. In IMPRES, imatinib delivered a reduction of more than 300 dyne-sec/cm. If IkT-001Pro can show a meaningful PVR improvement while keeping more patients on drug, it would be the clearest validation yet of the prodrug strategy.

3. Cash runway and financing activity: With roughly $97.5 million in cash, cash equivalents, and marketable securities as of year-end 2024, the question is how that runway lines up against execution. Watch quarterly burn relative to trial progress, and watch the financing mix—warrant exercises, secondary offerings, or partnership capital—not just for dilution impact, but for what it signals about outside conviction.

The Inhibikase story is still being written. What started as one scientist’s contrarian bet on Parkinson’s has now been reorganized into a more focused mission: take a drug the world already knows can work in PAH, and make it something patients can actually stay on. Whether that works will come down to data. But the arc so far—platform optionality, regulatory adversity, a hard Phase 2 reality check, and an abrupt strategic pivot—already reads like a masterclass in what biotech demands when biology refuses to cooperate on schedule.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music