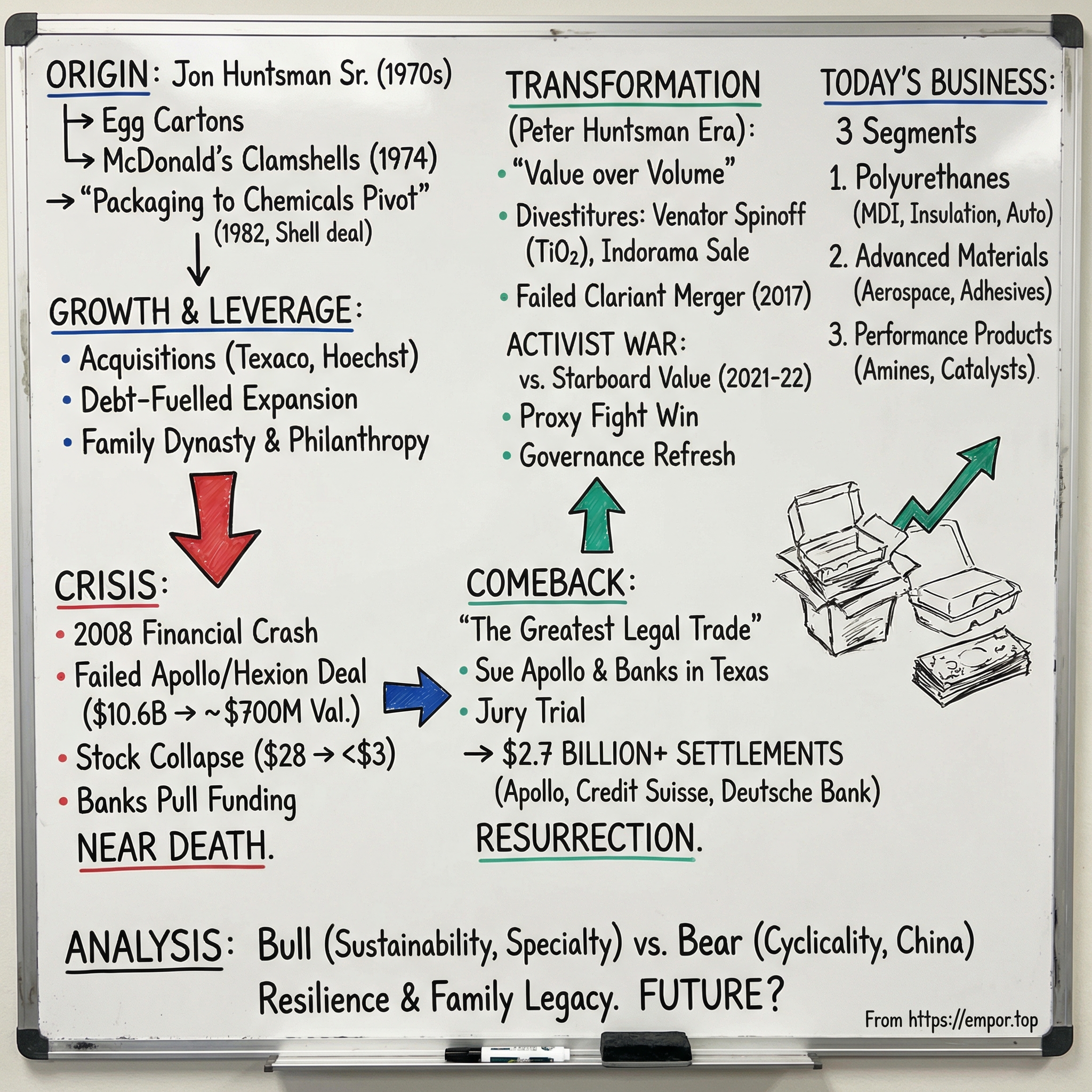

Huntsman Corporation: The Art of the Chemical Comeback

I. Introduction: The "Succession" of the Chemical World

Picture yourself at a McDonald’s in 1974, unwrapping a Big Mac. The burger’s hot, your hands aren’t greasy, and the whole thing is cradled in that satisfying foam clamshell—an object that became almost as iconic as the Golden Arches.

That container didn’t come from McDonald’s. It came from Huntsman, a company most Americans have never heard of. For decades, Huntsman’s plastics showed up in everyday life—sometimes invisibly, sometimes literally in your hands—long before anyone on Main Street would have recognized the name.

And that’s what makes this story so fun. Because Huntsman isn’t just “a chemical company.” It’s a corporate thriller: a family dynasty, a near-death experience in the 2008 financial crisis, and a billion-dollar legal brawl with private equity and Wall Street that ended with Huntsman extracting more than $2.7 billion in value—what might be the greatest legal trade in corporate history.

If Succession were set in industrial America instead of media, this is the vibe. Jon Meade Huntsman Sr. (June 21, 1937–February 2, 2018) built the business from nothing into a global manufacturer and marketer of specialty chemicals. Then he handed the keys to his son. Peter Huntsman became CEO in July 2000, and later took over as chairman in January 2018.

This deep dive has three big ideas. First: Huntsman is one of the most dramatic “near-death and rebirth” arcs in modern corporate history—a company that stared into the abyss in 2008 and came out the other side still standing, and fundamentally changed. Second: it’s a case study in ruthless portfolio transformation—shedding the most volatile, commodity-like businesses to become a more specialty-focused company. Third: it’s proof that a family-controlled public company can beat a top-tier activist investor, if the strategy is real and the execution holds.

Today, Huntsman is a publicly traded, global manufacturer and marketer of differentiated and specialty chemicals. In 2024, it generated about $6 billion in revenue, ran more than 60 manufacturing, R&D, and operations sites across roughly 25 countries, and employed around 6,300 associates. But that sleeker footprint is the end of the story, not the beginning. To understand what Huntsman is now—and why it matters—you have to go back to the moments when it almost didn’t make it at all.

II. Origin Story: The Gambler and the Golden Egg

The Huntsman story doesn’t start in a sleek corporate tower. It starts in rural Idaho, in the Great Depression.

Jon Meade Huntsman Sr. was born in Blackfoot, Idaho, to a family that didn’t have much. His mother, Sarah, stayed home. His father, Alonzo, taught school. This wasn’t “humble beginnings” as a branding exercise. This was the kind of life where a schoolteacher’s paycheck had to stretch, and then stretch again.

In 1950, the family moved to Palo Alto, California, because Alonzo was chasing something bigger: graduate studies at Stanford, where he earned an M.A. That move—education as the escape hatch—set a tone that Jon would take to an extreme.

He went to Wharton on a Zellerbach scholarship and graduated in 1959 at the top of his class. He served two years in the U.S. Navy, then earned an M.B.A. from the University of Southern California. For a kid from Blackfoot in that era, this was a rocket ship trajectory. But instead of using it to climb a corporate ladder, Huntsman aimed it at a very specific opportunity: packaging.

His first big break came in a place that sounds almost too mundane to matter: egg cartons. Working with the Olson Brothers, Inc., an egg producer in Los Angeles, he helped develop the first plastic egg carton. That led to something much bigger. In 1967, Huntsman was appointed president of Dow Chemical Company’s Dolco Packaging Division in Southern California, a joint venture with Olson Brothers.

Egg cartons turned into a Dow joint venture. And that joint venture became a launchpad.

In 1970, Huntsman left Dolco to form Huntsman Container Corporation. The company was credited with inventing the first plastic bowls, plates, utensils, meat trays, egg cartons, and a range of container products for the food industry—most famously, the McDonald’s Big Mac container.

The timing was perfect. The 1970s were a boom era for fast food, and fast food runs on consistency: standardized portions, standardized processes, standardized packaging. McDonald’s was expanding fast, and it needed containers that were cheap, reliable, and kept food hot. Huntsman had exactly what the market wanted.

A pivotal moment came in 1974, when Huntsman secured a landmark deal to supply McDonald’s. It wasn’t just a big customer; it was proof. Proof that the product worked at national scale, and proof that Huntsman could deliver. That kind of validation brings revenue, yes—but more importantly, it brings confidence and momentum.

But here’s the twist: Jon Huntsman Sr. didn’t want to be in the container business forever.

He looked at packaging and saw a good business. Then he looked upstream—at the chemicals that made the plastic—and saw the great business. In 1982, he made the defining pivot: he sold the packaging division and used the proceeds to acquire Shell Oil’s polystyrene business for $42 million.

That $42 million deal is the hinge in this story. Huntsman wasn’t going to be a packaging company that bought resin from chemical giants. It was going to become the chemical giant.

From there, the playbook was aggressive and very on-brand for the era: growth by acquisition, often using leveraged buyouts, buying assets that bigger companies didn’t want anymore. During the 1980s, Huntsman snapped up chemical operations as the industry consolidated. Major moves included acquiring Texaco’s chemical business in 1984 and Hoechst’s petrochemical facilities in 1985, rapidly expanding the company’s footprint.

This became the pattern: use debt to buy distressed or non-core assets from oil majors, integrate them, build scale, repeat. In chemicals, where plants are expensive and cycles are brutal, this is how you can grow fast—if you can survive the downturns.

And downturns are the tax you pay for playing in commodity chemicals. When the economy slows, demand drops, prices fall, and highly levered producers get squeezed. Huntsman Sr. wasn’t blind to that. He just had a rare tolerance for it. After re-entering plastics in the early 1980s, he bought Shell Chemical’s polystyrene plant in Belpre, Ohio, expanded it, and kept adding through acquisitions in the U.S. and abroad. He established Huntsman Chemical Corporation, which became a major global player in styrene monomer and polystyrene. Additional deals—assets from Shell, Elf Atochem in France, and a joint-venture purchase of Texaco Chemical Company—extended Huntsman’s global reach through the late 1980s and into the 1990s.

By the end of that run, Huntsman had become one of the largest privately held petrochemical companies in the United States. And the company’s DNA was set: high leverage, cyclical markets, and the instinct to bet big when others were retreating.

That mindset would eventually be tested in a way no acquisition spree could prepare for.

Because while Jon Huntsman Sr. was building a chemical empire, he was also building a family dynasty. Jon and Karen Huntsman had nine children. The eldest, Jon Huntsman Jr., went on to become Utah’s governor and later served as U.S. Ambassador to Singapore, China, and Russia, and he also spent time as a Huntsman Corporation executive.

But the company didn’t ultimately pass to Jon Jr. It passed to Peter, the second eldest—an operator, not a politician. In 2000, Peter replaced his father as CEO. It would prove to be one of the most important decisions the family ever made, because the next chapter wasn’t about growth. It was about survival.

At the same time, the Huntsmans were cementing a different kind of legacy: philanthropy. The Chronicle of Philanthropy ranked Jon Huntsman Sr. second on its 2007 list of the largest donors. Forbes later included him among the world’s most generous givers. In 1995, he contributed $100 million to establish the Huntsman Cancer Institute, and over time more than $2 billion would be directed to the Huntsman Cancer Institute and Hospital, with a substantial portion coming directly from Jon and Karen.

That generosity wasn’t separate from the company’s story. It was part of how the Huntsmans became a pillar in their communities—especially in Utah and Texas—building relationships and goodwill that would matter later, when Huntsman needed more than good operations. It needed allies.

III. The Perfect Storm: The 2008 Near-Death Experience

To understand how close Huntsman came to total destruction, you have to start with the deal fever of 2007. Private equity was awash in cheap debt, lenders were eager, and big industrial companies—especially chemical businesses with real assets—were suddenly “hot.”

Huntsman was a prize.

In June 2007, Huntsman announced it had agreed to be acquired by Access Industries, owned by billionaire Len Blavatnik, for $5.88 billion in cash. The deal would have paid Huntsman shareholders $25.25 a share, with Access also assuming about $3.7 billion of Huntsman’s debt.

Then, barely a month later, everything changed. On July 12, 2007, that agreement was terminated after Apollo Global Management came in with a higher bid—about $6.51 billion. It was the kind of moment sellers dream about: a real bidding war, in public, with the price climbing.

Apollo, led by Leon Black, planned to do the deal through Hexion Specialty Chemicals, its existing chemicals platform. Huntsman shareholders were promised $28 per share in cash. For the Huntsman family, this was the long-awaited cash-out moment—decades of grinding through the brutal cycles of commodities, finally converted into liquidity at a premium.

And then the world changed.

The financial crisis didn’t just nick Huntsman’s operating results. It ripped out the assumptions that made the buyout work. Oil prices spiked and then fell. Demand for chemicals dropped. Credit markets froze. In 2007, leverage made these mega-deals possible. In 2008, leverage became a weapon pointed back at everyone holding the bag.

Huntsman’s response wasn’t to quietly accept the collapse. In June 2008, Huntsman filed suit in Texas against Apollo and two of its partners, co-founders Leon Black and Josh Harris, after the group backed away from the deal. Huntsman alleged fraud, claiming Apollo never intended to allow its Hexion unit to complete the $6.5 billion purchase. Huntsman also claimed Apollo put forward the higher bid to block the Basell transaction, because a Basell-owned Huntsman would have threatened Hexion’s market position.

That’s not a normal “markets changed” disagreement. That’s an accusation that the bid was never meant to close—just meant to stop someone else from buying the company.

Hexion, for its part, pointed to Huntsman’s declining financial position as the reason the deal couldn’t go through. And when it became clear the merger agreement was effectively dead, Huntsman’s stock was punished immediately—dropping by almost half.

Half, in one move. But the real story is what came next.

With the $28-per-share exit vaporized, investors re-priced Huntsman as a stand-alone, highly cyclical, heavily indebted chemical company in the middle of a historic downturn. By the time the settlement news later emerged, Huntsman shares had fallen to $2.98, valuing the entire company at roughly $700 million.

Think about that swing. From a transaction valued around $10.6 billion including assumed debt, to a public-market value of about $700 million. From $28 a share to under $3. This wasn’t a bad quarter. This was the abyss.

And then came the banks. The Apollo-Hexion deal needed financing, and the lenders weren’t just passive bystanders. Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank were supposed to fund the transaction—but by October 2008, they backed away, arguing the combined Huntsman-Hexion business no longer met the standards in place when the deal was struck in July 2007.

That refusal to fund was the killing blow. No financing meant no closing. And with Huntsman’s business deteriorating, Apollo had an argument—at least in theory—under the logic of Material Adverse Effect clauses.

Huntsman was cornered: the buyout was collapsing, its stock was in free fall, and the standalone outlook looked brutal. A company built on living with leverage was now staring straight at the dark side of that DNA.

IV. The Greatest Legal Trade in History

This is the moment the Huntsman story stops being a business case study and turns into a courtroom thriller. Most companies in Huntsman’s position would have taken the loss: negotiate a breakup fee, lick their wounds, and focus on staying alive. The Huntsmans chose something else.

They chose war.

Huntsman sued Apollo and the banks, arguing that the banks had conspired with Apollo and interfered not just with the Hexion transaction, but also with Huntsman’s earlier merger agreement with Basell.

The masterstroke was where they fought.

The Huntsman family had deep roots in Texas. The company employed thousands there. Jon Huntsman Sr. had spent decades building relationships and goodwill. So Huntsman steered the fight to a place where those things mattered: Montgomery County, Texas. A jury trial was set in Conroe—far from the finance-world comfort of New York or Delaware, and much closer to the kind of jury that might instinctively side with a major local employer over Wall Street lenders.

When the trial kicked off, Gibbs & Bruns partners Robin Gibbs and Kathy Patrick framed it exactly that way. They told jurors they were about to see how “these enormous investment banks wield enormous power,” and that the jury would have a chance to “send a message from Main Street in Conroe to Wall Street and the financial capitals of Europe.”

The claims were sweeping: fraud, commercial disparagement, tortious interference with the Basell agreement, tortious interference with the Hexion agreement, and conspiracy with Apollo and with each other. And Huntsman didn’t come asking for symbolic damages. The complaint sought more than $8 billion—split between roughly $3.6 billion tied to Basell and $4.5 billion tied to Hexion.

That number wasn’t just big. In Texas, it was terrifying.

But Huntsman also knew it couldn’t afford a two-front war forever. So it pushed to resolve the Apollo fight first. Apollo affiliates made cash payments totaling $425 million, and also paid another $250 million in exchange for 10-year convertible notes issued by Huntsman. At least $500 million of those payments were due on or before December 31, 2008.

Then, in December 2008—when the global financial system was still on life support—Apollo and Hexion agreed to pay Huntsman about $1.1 billion in exchange for Huntsman dropping its claims. The package included $500 million in cash, the $250 million investment, and the additional $425 million cash payments.

A billion-dollar settlement, in that moment, was almost unheard of. Peter Huntsman put it bluntly: “When you think of the annals of corporate histories, I’m not sure you can come up with more than one or two settlements, either in court or out of court, where one company pays another company $1 billion.”

Phase One was over. And it set up Phase Two.

As 2009 began, Peter Huntsman said, “We begin 2009 with cash in the bank and the objective of bringing Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank to justice for the harm they have caused.”

Here’s the part that reads like a plot twist: the Apollo settlement came with a built-in advantage for the next battle. Under the settlement agreement, Apollo and its principals agreed to fully cooperate with Huntsman in its litigation against the banks. In other words: Apollo’s people, Apollo’s documents, Apollo’s inside view—now available to Huntsman, aimed directly at Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank.

Huntsman went into the Texas courtroom asking the jury for $4.65 billion in compensatory damages and another $9.3 billion in punitive damages. The pressure worked. After a week of jury selection and another week of trial, the banks settled. Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank agreed to pay $316 million each in cash.

But that wasn’t the whole package. Gibbs & Bruns secured what it described as a record $1.7 billion settlement package: $632 million in cash plus $1.1 billion of financing through notes and bonds on favorable terms.

The trial itself mattered too. Peter Huntsman took the stand for three days. According to The American Lawyer, during cross-examination he “held up well, neither appearing hostile nor ceding any points.”

When it was all tallied—Apollo and Hexion, plus the banks—Huntsman noted that total proceeds exceeded $2.7 billion.

Let that sink in. At the low point, Huntsman’s market cap had fallen to roughly $700 million. The litigation proceeds alone were worth multiples of the company’s entire equity value at its nadir.

On December 30, 2008, Huntsman announced it had received the final payment from Apollo’s affiliates. Net proceeds from those payments—excluding fees and expenses—went to reduce indebtedness and increase liquidity.

This wasn’t just a legal win. It was corporate resurrection.

The settlement money became the seed capital for the modern Huntsman. Instead of bankruptcy, deleveraging. Instead of selling assets at fire-sale prices, breathing room and optionality. The company was, in a very real sense, re-founded with the proceeds from the attempt to destroy it.

V. The Peter Huntsman Era: "Value over Volume"

With the company pulled back from the edge, the next problem wasn’t survival. It was identity.

The crisis had exposed Huntsman’s weak spot: too much of the business rose and fell with commodity cycles, and too much demand depended on end markets like construction and autos—great in a boom, brutal in a recession. The legal windfall bought time. It didn’t magically make the company less cyclical. That would take a different kind of work.

That work fell to Peter Riley Huntsman (born March 13, 1963), Jon Huntsman Sr.’s son, and by then the company’s long-tenured operator. Peter wasn’t new to the machine. He had been with Huntsman in various roles since 1983, became president and chief operating officer in 1994, and then stepped into the CEO role in July 2000. In January 2018, he also became chairman of the board. He’s also the brother of Jon Huntsman Jr., the former U.S. ambassador and former governor of Utah.

If Jon Sr. was the charismatic dealmaker who built Huntsman through acquisitions, Peter became the methodical leader who reshaped it through divestitures. Internally, the philosophy was “value over volume”—a shift away from winning by scale and tonnage, and toward selling more differentiated products with better economics. Less “how many railcars shipped,” more “how valuable is what we’re shipping.”

That meant exiting lower-margin base chemicals. Under Peter, Huntsman moved away from units that produced products like ethylene oxide, used in antifreeze and as a pesticide. And the clearest example of the strategy was the 2020 Indorama deal.

In January 2020, Huntsman sold its chemical intermediates and surfactants businesses—including its Port Neches facility—to Thailand-based Indorama Ventures in a transaction valued at about $2 billion, with a cash purchase price of roughly $1.93 billion. It wasn’t just a portfolio tweak. It was Huntsman deliberately shrinking its more capital-intensive upstream footprint.

Peter described it that way at the time: “This transformational transaction significantly reduces our capital-intensive upstream asset base, further bolsters our already strong balance sheet and allows us to further invest in and grow our downstream businesses.”

But the most symbolic move—the one that felt like Huntsman cutting away a piece of its own history—was the Venator spinoff.

Titanium dioxide, or TiO2, is the white pigment that shows up everywhere: paint, coatings, sunscreen, even food coloring. It was a big, familiar business. It was also volatile. In August 2017, Huntsman spun off its Pigments and Additives division as a new public company, Venator Materials, which began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker “VNTR.”

The name was a wink and a goodbye. Venator is Latin for “hunter”—a play on “Huntsman.” And the new company largely centered on TiO2, a business known for sharper booms and busts than Huntsman’s specialty-leaning segments.

At the IPO, Venator raised $454 million at $20 a share. Huntsman pointed to the financial impact at the time: profits more than doubled to $179 million, and debt fell from $4.5 billion to $2.4 billion—largely using the proceeds from the Venator offering.

Then came the second act, and it proved why Huntsman wanted that cyclicality out of the house.

Venator, which owned Huntsman’s former Titanium Dioxide and Performance Additives businesses, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on May 14, 2023. It entered the process with a restructuring agreement in place, with creditors converting debt into equity. Venator had about $1 billion of debt, had been losing money for three years, and had been squeezed by sluggish demand and high energy costs. In 2022, it lost $188 million on $2.2 billion in sales.

Venator later completed its Chapter 11 recapitalization and emerged with far less debt. The bankruptcy court confirmed its plan on July 25, 2023. Venator attributed the restructuring to unprecedented macroeconomic headwinds, including significantly lower product demand and higher raw material and energy costs, and it reduced its debt from more than $1 billion to about $200 million upon emergence.

From Huntsman’s perspective, the takeaway was simple: imagine carrying that burden through the pandemic, the energy shock, and Europe’s industrial slowdown. Spinning off Venator wasn’t just a strategic cleanup. In hindsight, it looked downright prescient.

VI. The Failed Merger and The Activist Wars

Even as Huntsman was pruning away commodities and pushing deeper into specialties, Peter Huntsman also chased a faster route: combine with someone else and buy scale overnight.

In May 2017, Huntsman announced what looked like the logical endgame of its “value over volume” evolution: a merger of equals with Clariant, the Swiss specialty-chemicals group. It was an all-stock deal, pitched as the creation of a global specialty leader—roughly $13 billion in sales, about $2.3 billion in adjusted EBITDA, and a combined enterprise value around $20 billion.

The plan was to create a new company often referred to as “HuntsmanClariant,” with Clariant shareholders owning 52% and Huntsman shareholders 48%. Management projected about $400 million a year in cost savings. On paper, it was clean: two mid-sized players joining forces to compete better against giants like BASF and Dow. And the CEOs—Peter Huntsman and Clariant’s Hariolf Kottmann—weren’t just aligned strategically; they genuinely liked each other. Both companies leaned into that friendship as part of the story.

Then the activists showed up.

After the deal was announced, White Tale—an investment vehicle tied to hedge fund manager Keith Meister and New York-based 40 North—built its stake in Clariant to more than 20%. Their argument wasn’t subtle: the merger didn’t pay Clariant shareholders enough for the risk, and it dragged Clariant toward Huntsman’s debt and what they viewed as Huntsman’s lingering exposure to more volatile, commodity-like businesses. White Tale said the deal “significantly destroys existing Clariant shareholder value” and blocked Clariant from pursuing faster, clearer ways to unlock value.

They pushed a different path: instead of merging with Huntsman, Clariant should sell its plastics and coatings business and become a purer specialty company.

Huntsman and Clariant kept insisting the merger was the right long-term move. But Swiss law required a two-thirds shareholder approval. With White Tale accumulating shares and rallying other investors, the math started to look like a coin flip—and in deals like this, “coin flip” is another word for dead.

On October 27, 2017, the two companies jointly announced they were terminating the merger by mutual agreement. Both boards approved the decision unanimously.

Peter Huntsman did what CEOs have to do in moments like this: he moved the narrative forward. “We viewed this merger of equals as an opportunity to accelerate our downstream growth and for two great companies to become even better together,” he said. “However, it is not the only option for Huntsman to create real and lasting value.”

But the market takeaway was simpler. Huntsman was still independent—still mid-cap—and now freshly labeled as “in play.” That’s catnip for activists.

In 2021, Starboard Value came calling. In January, Starboard revealed it owned about 8.6% of Huntsman’s shares, making it one of the company’s largest shareholders. This wasn’t a protest stake. It was a control stake in everything but name.

And it set up an unusually clean showdown. Starboard versus the Huntsman family. Starboard’s stake versus the combined stake held by Peter Huntsman and the family’s J.K. Huntsman Foundation. Everyone else—institutional shareholders—were the swing votes.

Starboard’s playbook was familiar: allege persistent underperformance, argue the company had missed too many targets, and push for new directors who, in Starboard’s view, would hold management to tighter accountability. Huntsman fired back just as hard. It attacked Starboard’s nominees and dismissed their relevance—for example, arguing that Jim Gallogly’s experience running LyondellBasell was rooted in commodity chemicals, not the specialty-focused Huntsman Peter was building. Huntsman also accused Starboard of oversimplifying a portfolio transformation that, by its nature, takes time.

Starboard, meanwhile, went after Huntsman’s governance. It criticized what it described as a board stocked with friends, former employees, and people with financial ties to the Huntsman family.

Huntsman didn’t respond with a quiet press release. On March 2, 2022, it dropped a 52-page investor presentation—part defense brief, part campaign document—arguing the board was “refreshed and fit-for-purpose,” the portfolio strategy was working, and the balance sheet was investment grade.

It also pointed to visible change: from the end of 2017 through the 2022 annual meeting, Huntsman added eight new independent directors, saw six incumbent directors retire, and installed a new lead independent director along with new committee chairs. After Starboard’s campaign began—but consistent with the direction Huntsman said it was already heading—the company also announced long-term financial targets, a review of strategic alternatives for one of its businesses, and a new executive compensation plan tied to the newly announced goals.

Then came the vote.

At the March 25, 2022 annual meeting, Huntsman announced that shareholders elected all ten of the company’s director nominees. Peter Huntsman framed it as a referendum on the entire reinvention: the vote, he said, validated the portfolio strategy and showed “the Huntsman of today is vastly different than the Huntsman of five years ago.”

For Starboard, it was a rare public defeat in a world where most companies settle before the ballots get counted. And for Huntsman, it was something it hadn’t been able to count on in 2008: a clean win, in the open, against one of the most feared activists in the game. Starboard ultimately exited its position.

VII. The Business Today: What Do They Actually Do?

After all the pruning, spinoffs, and near-death drama, Huntsman today is a three-act company. And each act helps explain why the modern Huntsman looks a lot less like “plastic cups by the ton” and a lot more like “materials that make everything else possible.”

Polyurethanes: The Core Engine

If Huntsman has a heartbeat, this is it.

Huntsman Polyurethanes is a global leader in MDI-based polyurethanes—supplying materials that end up as rigid and flexible foams, thermoplastic urethanes, coatings, adhesives, composites, sealants, and elastomers. It serves more than 3,000 customers across over 90 countries, with world-scale facilities in the U.S., the Netherlands, and China, plus a network of more than 30 downstream formulation sites.

The central character here is MDI—methylene diphenyl diisocyanate. The acronym doesn’t mean much to consumers, but the applications absolutely do. MDI-based polyurethane is widely used as an energy-saving insulation material in residential and commercial buildings, because it’s one of the most effective thermal insulants available.

Once you start looking for it, you see it everywhere. The insulation in your refrigerator. The foam in your car seats. The cushioning in furniture, mattresses, and pillows. And in footwear, Huntsman’s polyurethane, thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU), and textile-based solutions help brands bring products to market faster, including shoes with that springy, responsive feel people pay up for.

Insulation is the strategic anchor. Polyurethane shows up in roofs, walls, floors, doors, ceiling cavities, and pipes, across both new construction and retrofits. Huntsman’s portfolio—thermal insulation, coatings and adhesives, composite wood products, TPU, and foams—supports applications across flooring, roofs, walls, facades, doors, windows, driveways, roads, and piping.

It also plays a role in the cold chain. Huntsman’s MDI-based rigid polyurethane foam provides strong thermal insulation, which helps reduce food waste and extend the life of perishable goods as they move through storage and transport.

And then there’s the manufacturing edge: Huntsman started commercial operation of a new MDI splitter at its Geismar, Louisiana site. That splitter technology matters because it can improve manufacturing economics—especially with access to relatively low-cost U.S. natural gas, a meaningful advantage versus European competitors facing much higher energy costs.

Advanced Materials: The High-Tech Moat

If Polyurethanes is the engine, Advanced Materials is the part of Huntsman that feels closest to a true specialty company.

This segment makes specialty epoxy, acrylic, and polyurethane-based resin systems and adhesive products—materials increasingly used instead of traditional options in aircraft, automobiles, and electrical power transmission. You’ll also find them in coatings, construction materials, circuit boards, and sports equipment.

In aerospace and defense, Huntsman supplies high-performance structural adhesives, laminating systems, TPU films for impact-resistant laminated glass, edge fillers for interior structures and fixtures, and composite resins designed for light-weighting. These products aren’t casual purchases. They’re qualified to OEM specifications—Boeing, Airbus, Goodrich, Gulfstream, Bombardier, Bell, Rohr, and others.

The broader point is how far the company has traveled. As Huntsman has put it: every Boeing 787 flying will have about 20 tons of Huntsman or Huntsman-related materials per plane. That’s the chemical industry’s arc in one sentence—from disposable packaging to materials you can’t realistically build modern aircraft without.

This segment also shows Huntsman’s real moat: switching costs. In aerospace, qualification takes years of testing and certification. Once a material is approved and integrated into the design and manufacturing process, customers don’t change suppliers lightly. Many of Huntsman’s epoxies are flame retardant and meet the low flame, smoke, and toxicity requirements needed to comply with regulations like FAR 25.853 for large civil aircraft.

Performance Products: The Specialty Additive

Performance Products is Huntsman’s “quiet enabler” business: chemicals that don’t usually get credit, but make other products work.

It holds leading global positions in amines, maleic anhydride, and carbonates, serving consumer and industrial end markets—including energy. The segment sells more than 800 products to over 1,000 customers globally.

Think of these as the useful building blocks: catalysts, curing agents, and intermediates that show up across industrial supply chains, enabling everything from wind turbine blades to EV batteries.

VIII. Analysis: Power and Strategy

Now that we know what Huntsman makes, the real question is: how defensible is it?

A good way to answer that is to run the company through a couple of classic strategy lenses—first Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers, then Porter’s Five Forces—and see what actually holds up in the real world of chemicals.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Analysis

Switching Costs (Medium-High): This is Huntsman’s best moat, especially in Advanced Materials. In aerospace, qualification cycles can take years. Once a resin or adhesive system is specified on a Boeing or Airbus platform, swapping it out isn’t just “finding a new supplier”—it means retesting, recertifying, and redoing process work that nobody wants to reopen. In polyurethanes, the products are often formulated around a specific customer’s needs, which creates stickiness too. But when you drift closer to commodity-like applications, that protection fades fast.

Scale Economies (High): MDI is the kind of business where scale isn’t an advantage—it’s admission. World-scale plants are enormously expensive, slow to build, and hard to permit. Huntsman has major production in the U.S., the Netherlands, and China, and the global market itself looks like an oligopoly: BASF, Wanhua, Covestro, and Huntsman. That doesn’t mean profits are guaranteed—it means it’s incredibly hard for a new player to show up and change the game.

Cornered Resource (Medium): Geismar, Louisiana matters here. The splitter technology and the reality of U.S. shale-linked energy economics create a meaningful cost position versus Europe, where energy can be structurally more expensive. This isn’t a “secret recipe” moat—the technology isn’t proprietary—but the combination of existing assets and favorable geography can be durable.

Network Effects (Low): Huntsman isn’t a network-effect business. Selling to more customers doesn’t inherently make the product more valuable to the next customer.

Counter-Positioning (Medium): “Value over volume” is a strategic stance that puts Huntsman on a different footing than pure commodity producers. Huntsman is deliberately leaning into more downstream, more specialized applications—often smaller volumes, better economics. For a producer built around massive commodity throughput, making that same pivot can mean dismantling the very business model that funds the company.

Brand (Low): This is industrial B2B. End consumers aren’t choosing Huntsman; engineers and procurement teams are choosing performance, reliability, qualification status, and total cost.

Process Power (Medium): A lot of Huntsman’s edge comes from formulation and application know-how—technical teams that can customize products to a customer’s design constraints and manufacturing process. That’s not “brand power,” and it’s not quite a patented-product story either. It’s closer to process power: repeatable expertise that makes Huntsman harder to replace than a spec sheet would suggest.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Supplier Power (High): Key inputs like benzene and natural-gas-derived feedstocks are commodities. Prices are set by global markets, not by Huntsman’s negotiating skills. Geography helps—U.S. energy dynamics can be an advantage—but it doesn’t remove exposure.

Buyer Power (Medium): It depends where you’re sitting. In more commodity-adjacent categories, buyers have options and price pressure is constant. In aerospace and other highly specified applications, “approved supplier” status acts like a lock, and buyer power drops.

Threat of New Entrants (Low): Building new chemical plants in Western markets is brutally hard—capex-heavy, slow, and increasingly constrained by regulation. The bigger risk isn’t a new entrant in the U.S. or Europe. It’s capacity expansion in China—particularly from Wanhua in MDI. Separately, with a record amount of chemical assets for sale globally (especially in Europe), you can also see the opposite dynamic: closures and consolidation driven by high costs and regulatory burdens.

Threat of Substitutes (Medium): There are substitutes, but they’re application-specific. For insulation, polyurethane competes with materials like fiberglass. For lightweighting in autos and aerospace, composites compete with aluminum and high-strength steel. Nothing here screams “existential replacement,” but the threat shows up around the edges in particular use cases.

Industry Rivalry (High): Chemicals is a knife fight. Giants like BASF, Dow, Covestro, and Wanhua compete on price, technology, and customer relationships, and margins can swing hard with supply-demand balance. Even when producers try to push price, customers push back—Huntsman has faced that challenge in MDI when price increases haven’t gained traction.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

If you want to track whether Huntsman’s transformation is really working, three metrics tell most of the story:

-

MDI Margins/Spreads: For Polyurethanes, the most important number is the spread between what Huntsman sells MDI for and what its key inputs cost. When spreads widen, earnings power snaps back quickly; when they compress, everything feels heavy. Management has noted that the business starts to show real operating leverage at high utilization. Quarterly commentary on pricing and demand is the best real-time read on the health of Huntsman’s core engine.

-

Adjusted EBITDA Margin by Segment: “Value over volume” should show up as structurally better margins over time, even when revenue is under pressure. Recent results included about $5.8 billion of revenue over the last twelve months through 3Q25, about $311 million of adjusted EBITDA over that same period, and net leverage around 5.0x. The direction matters more than the precision: are margins improving as the portfolio gets more specialty, or not?

-

Free Cash Flow Conversion: Huntsman’s history makes this one non-negotiable. Cyclical industries punish weak cash generation, especially when leverage is involved. In Q3 2025, free cash flow from continuing operations was $157 million, up from $93 million in the same period of 2024. Sustained free cash flow is what funds dividends, reduces debt, and pays for the next wave of investment—basically, the difference between “specialty strategy” as a slide deck and “specialty strategy” as a durable company.

IX. The Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case: Pick-and-Shovel Play for Sustainability

The bull story starts with a simple idea: the world is being forced to waste less energy. Regulations are tightening. Customers are demanding efficiency. And a surprising amount of that future runs through chemistry.

Better-insulated buildings need more advanced foam systems and better installation. Lighter, more efficient vehicles need high-performance materials and adhesives. Wind blades, solar components, and modern power infrastructure all depend on specialty formulations that can survive stress, heat, and time. In that framing, Huntsman isn’t trying to “win” sustainability as a brand. It’s selling the pick-and-shovel inputs that make the sustainability buildout possible.

That’s why Polyurethanes matters. If you believe the big megatrends—electrification, urbanization, decarbonization—are real, you end up needing polyurethane insulation, coatings, adhesives, and materials engineered for efficiency, whether the end customer knows Huntsman’s name or not. Management has also pointed to growth opportunities in areas like EV batteries and the steady tightening of insulation standards.

Then there’s the valuation pitch. Huntsman has often traded at a meaningful discount to “pure specialty” peers like Sika or Sherwin-Williams. Bulls argue that discount is backward-looking: the transformation is farther along than the market is giving credit for, and the business quality has improved even if the ticker still gets priced like old Huntsman.

Advanced Materials adds another layer to the bull case. Aerospace and defense customers don’t casually swap out structural adhesives or composite resins. Huntsman’s products help customers improve manufacturing processes, enable complex designs, reduce weight, and stay compliant with stringent standards. With the post-pandemic recovery in aerospace providing multi-year visibility into demand, that qualification-driven stickiness is exactly the kind of specialty exposure investors like.

And finally, the Starboard fight matters for sentiment. Huntsman didn’t just survive an activist campaign; it won in an open vote and kept executing while the spotlight was on. In the period following Starboard’s 13D filing, Huntsman continued pushing its long-term strategy and delivered record full-year results in 2021—evidence, at least in the bull framing, that management could set targets and then move the numbers in the right direction.

The Bear Case: Still Tethered to the Cycle

The bear case asks a blunt question: has Huntsman truly escaped its own DNA?

Even after all the divestitures, Polyurethanes is still the heavyweight. And MDI is still tied to construction and automotive—two end markets that don’t do “steady.” When demand softens, prices move fast. Huntsman has said the decrease in Polyurethanes revenues was driven largely by lower average selling prices, only partially offset by higher volumes, with MDI pricing pressured by less favorable supply-demand dynamics.

Recent performance highlights that reality. Third quarter 2025 adjusted EBITDA came in at $94 million versus $131 million a year earlier, and management guided for fourth quarter 2025 adjusted EBITDA at the low end of a $25 million to $50 million range. That’s not the profile of a business that can fully shrug off a downturn.

Europe is another pressure point. Huntsman cited lower construction-related demand and a scheduled turnaround at its Rotterdam facility as drivers of lower volumes. More broadly, the worry is structural: high energy costs and regulatory burdens have made European chemical production a tougher game, and any trend toward deindustrialization hits chemical operators with European assets harder than the spreadsheet models suggest.

Then there’s China—the external variable that can matter more than anything Huntsman does internally. Wanhua has been expanding MDI capacity aggressively. That means global pricing and utilization can increasingly hinge on Chinese construction activity and Wanhua’s willingness to keep capacity disciplined. Huntsman can run its plants well; it can’t set the global cycle.

Underneath all of this is the valuation debate that never really goes away: specialty or “fancy commodity.” Bears argue Huntsman is often selling higher-performance versions of products that still behave like commodities when the market turns—good businesses, but not the kind that deserve premium multiples built on pricing power and demand resilience.

And while family control can be a strength, it also keeps governance in the conversation. Starboard’s campaign put board composition front and center, criticizing what it saw as ties between directors and the Huntsman family. Huntsman won the fight. But for some investors—especially those with an ESG lens—family-controlled public companies still come with an implied governance discount, even when the strategy is sound.

X. Playbook and Lessons

The Huntsman story isn’t just entertaining. It’s useful. There are a few lessons here that apply way beyond chemicals.

Litigation as an Asset Class

What Huntsman did in 2008 and 2009 is worth studying like a great investment.

When the deal collapsed and the company was staring at an existential crisis, Huntsman didn’t follow the conventional script of quietly negotiating a breakup fee and moving on. It treated the courtroom like a capital markets venue. The company understood that venue selection mattered, that incentives mattered, and that there was real “arbitrage” between Texas juries, New York banks, and the norms of corporate dealmaking.

The result: more than $2.7 billion in proceeds from Apollo/Hexion and the banks—worth multiple times the company’s equity value at its lowest point.

The takeaway isn’t “sue people and you’ll get rich.” It’s that litigation can be a strategic tool, and it should be evaluated like any other capital allocation decision: expected value, cost, time, and the range of outcomes. Huntsman made a calculated bet that a Texas jury would view a major local employer differently than it would view Wall Street lenders. And that bet worked.

Portfolio Gardening Requires Discipline

Over the last 15 years, Huntsman remade itself the hard way: not by acquiring new businesses, but by shrinking and simplifying the old ones.

It sold or separated from multiple operations—base chemicals, polymers, titanium dioxide, PO/MTBE, intermediates—and kept pushing the center of gravity toward more differentiated, specialty-oriented businesses.

The hardest part of that strategy isn’t the spreadsheet math. It’s the emotion. Selling the business your father invented—the packaging business that launched the company—requires a kind of discipline that family-controlled companies often struggle with. Under Peter, Huntsman repeatedly chose margin quality over sheer revenue: the Venator spinoff, the Indorama sale, and a steady exit from sharper-cycle businesses.

In hindsight, the Venator outcome is the clearest proof point. Venator later went through Chapter 11. If Huntsman had kept that TiO2 exposure on its own balance sheet, it would have carried the same demand shocks, energy-cost pressure, and volatility. The pruning didn’t just improve the narrative; it reduced the risk of the whole enterprise.

Family Control: The Tradeoffs

The Starboard fight put a spotlight on an awkward reality of public, family-influenced companies: ownership can be both shield and target.

Starboard owned nearly 9% of the The Woodlands-based company. Peter Huntsman and the family’s J.K. Huntsman Foundation owned a combined 8.1%.

The advantage of that structure is long-term orientation. A founder like Jon Huntsman Sr. could make bets measured in decades, not quarters. The vulnerability is the perception of entrenchment—activists can argue, as Starboard did, that boards tied to a family lack independence and accountability.

Huntsman’s response offers the lesson. Rather than treating governance as optics, it treated it as a live operating issue. From the end of 2017 through the 2022 annual meeting, Huntsman added eight new independent directors and saw six incumbent directors retire. The point isn’t that every company needs the same numbers. It’s that family influence can coexist with credible governance—but only if the board is continuously refreshed and clearly independent.

The Nixon Connection

One fascinating footnote: Jon Huntsman Sr.’s early career briefly ran straight through American political history.

As Huntsman Container’s first packaging plant was being built in 1970, Huntsman joined the Nixon Administration—first as Associate Administrator of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, and later as Special Assistant and Staff Secretary to President Nixon. Then, after the second Huntsman Container site in Troy, Ohio was completed in 1972, he left the White House to return to the company as President and CEO.

That experience helped shape something that shows up repeatedly in this story: the importance of relationships and reputation. Huntsman’s community ties in Texas, its philanthropic presence in Utah, its broader civic footprint—those weren’t separate from the business. They were part of the company’s strategic environment. And in 2009, when Huntsman needed a jury to believe its story, that environment mattered.

XI. Where Huntsman Stands Today

Huntsman Corporation is a publicly traded, global manufacturer and marketer of differentiated and specialty chemicals. In 2024, it generated about $6 billion in revenue, operated more than 60 manufacturing, R&D, and operations facilities across roughly 25 countries, and employed around 6,300 associates within its continuing operations.

But the facts don’t capture the contrast.

This is the company that once made foam clamshell containers for McDonald’s—and now supplies materials that show up on every Boeing 787 in the sky. The company that looked like it might not survive 2008—and instead went into court and came out with billions in settlements from Apollo, Hexion, and Wall Street banks. The company that got targeted by one of the most feared activists in the game—and then won the proxy fight anyway, watching Starboard ultimately walk away.

Jon Huntsman Sr. passed away on February 2, 2018, leaving behind the kind of legacy that’s hard to separate from the company itself. In December 2017, the board named him Director and Chairman Emeritus, and elected his son, Peter R. Huntsman, as Chairman, President, and CEO.

So where does that leave Huntsman now?

For investors, the central question is whether the transformation is finished—and whether the market will ever treat Huntsman like the specialty company it says it has become. Management’s pitch is that Huntsman deserves specialty multiples. The market’s counterargument is embedded in the price: Huntsman still trades like a cyclical chemical company.

As Huntsman has framed it: "Transformation isn't just a strategy; it's a necessity. The decisions we make today, in an ever-evolving regulatory landscape, will resonate for decades. It's not about chasing carbon neutrality—it's about being smart with carbon utilization and continually innovating for a smarter, more sustainable future."

Whether that narrative pays off will depend on the real-world variables that still run the table: the MDI cycle, the health of European industry, Chinese capacity discipline, and the durability of the aerospace recovery.

What’s not up for debate is the resilience. Huntsman has already lived through challenges that would have erased most companies. The family that went “barefoot to billionaire,” as Jon Sr. titled his autobiography, built something that lasts. The next chapter is still being written.

And if you want a window into Jon Huntsman Sr.’s worldview, his book Winners Never Cheat: Everyday Values We Learned as Children (But May Have Forgotten) lays it out. Published by Wharton School Publishing in 2005, it argues that in an industry known for harsh cycles, environmental scrutiny, and aggressive dealmaking, old-fashioned values can still coexist with commercial success. Huntsman is still testing that proposition—quarter after quarter.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music