Heidrick & Struggles: The Story of Executive Search's Public Market Survivor

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

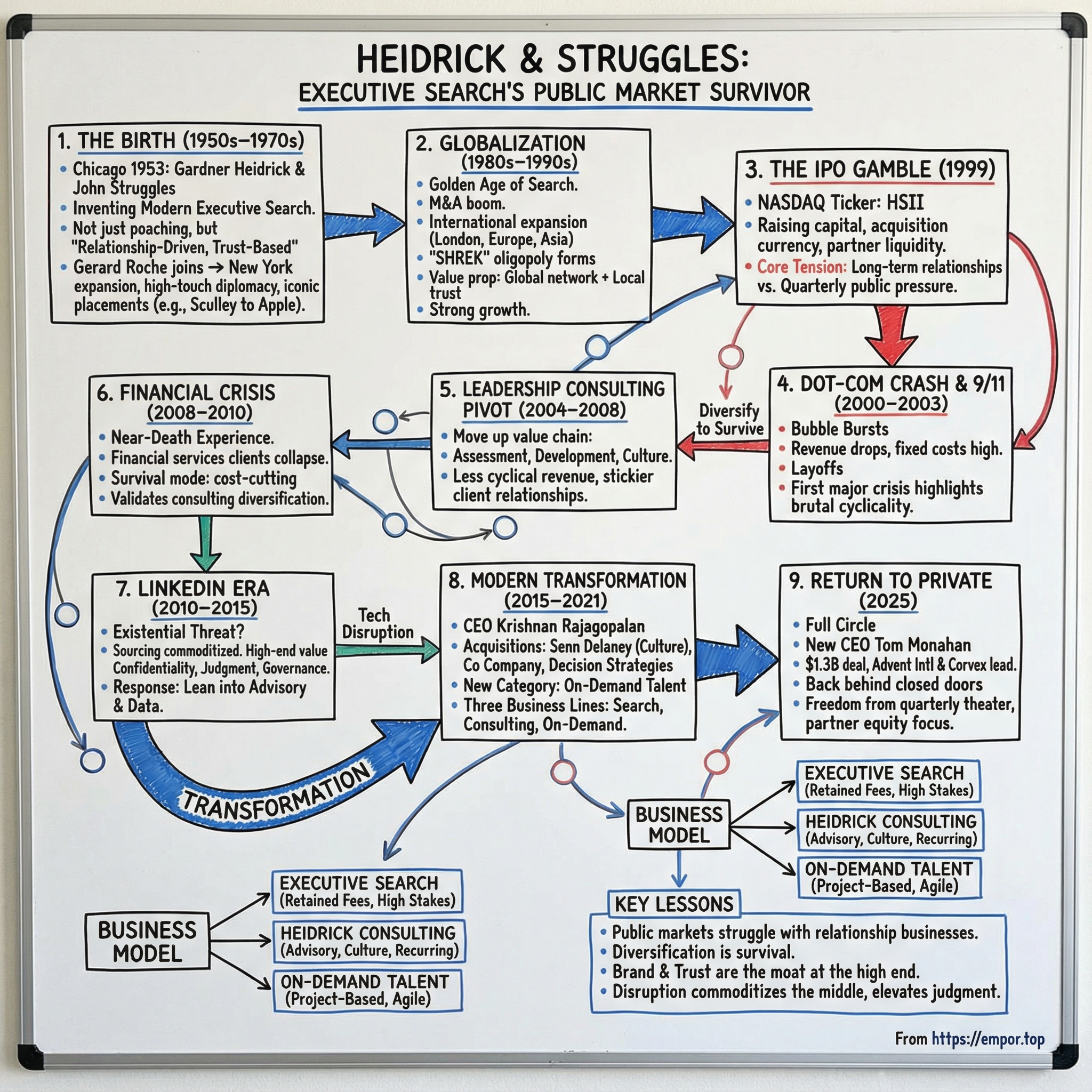

Picture this: it’s October 2025, and a 72-year-old executive search firm is about to go full circle. Heidrick & Struggles announces a definitive agreement to become privately held again, acquired by a consortium led by Advent International and Corvex Private Equity. It’s an all-cash deal worth about $1.3 billion. After 26 years on the NASDAQ, one of the founding firms of modern executive search is heading back behind closed doors.

That headline is a perfect doorway into the real story here. This isn’t just about a company that helps Fortune 500 boards pick their next CEO. It’s about the core contradiction at the heart of professional services: can a business built on relationships, discretion, and judgment thrive under the public markets’ constant demand for predictability?

Because this is a people business in the purest sense. The product isn’t software or factories or patents. The product is the partners’ networks, the firm’s reputation, and a process that depends on trust. And in a business like that, your most valuable assets go home every night—and can leave for good at any time.

Heidrick has spent more than 70 years building its name in that world: high-stakes, high-touch leadership work where confidentiality matters and the consequences of a bad hire can be catastrophic. Over time, it expanded far beyond “just” search, pushing into leadership consulting, culture and team effectiveness work, and on-demand talent—partly to grow, but also to smooth out the brutal cyclicality of hiring.

So today’s arc is reinvention, over and over. Surviving the dot-com crash. Then the Great Financial Crisis. Then the “isn’t LinkedIn going to kill you?” era. Each time, the company had to change enough to stay relevant—without breaking the very thing clients were paying for: trust.

And for investors and operators, the lessons travel. What happens when you take a relationship business public? How do you diversify without losing your edge? And when disruption hits—whether it’s a social network, a recession, or an algorithm—how do you adapt without turning yourself into something nobody asked for?

Let’s start at the beginning: downtown Chicago, a small office, and two men who decided that finding executives could be a profession—not a favor, not a hustle, and not just poaching.

II. The Birth of Modern Executive Search (1950s–1970s)

On November 15, 1953, in a modest downtown Chicago office, Gardner Heidrick and John Struggles opened the doors to Heidrick & Struggles. The premise was deceptively simple: help companies find the leaders who could actually grow the business.

To see why that was such a big idea, you have to zoom out to the America they were selling into. Post–World War II corporate life was booming. Companies were scaling fast, getting more complex, and increasingly run by professional managers—the era of the “organization man.” But the higher you went in an org chart, the harder the hiring problem became. Boards weren’t looking for “a resume.” They were looking for judgment, credibility, and someone who could survive the politics of the top floor.

Heidrick and Struggles came out of Booz Allen Hamilton, bringing a consultant’s instinct for process to what was, at the time, an informal business. Their first clients—West Virginia Coal & Coke Corporation, Northern Trust, and Continental Can—hint at the early market: large, established institutions that couldn’t afford leadership mistakes. And in an era when recruiting meant personal favors and newspaper ads, the idea that a dedicated firm would systematically identify, evaluate, and recommend senior executives was genuinely novel.

As one history of the industry puts it: “Back in the 1950s, the retained executive search industry was in its infancy. But Gardner Heidrick and John E. Struggles had determination and vision, and today, that vision has translated into a $10 billion industry.”

The firm moved quickly to establish credibility. They incorporated in 1953, kept headquarters in Chicago, and put their own names on the door—a small choice that mattered in a trust business. Early on, Heidrick & Struggles built a reputation for discreet, hands-on work in banking, insurance, and accounting: conservative industries with high standards and long memories.

Then came the hire that changed everything.

Gardner Heidrick brought in Gerard Roche because he was smart, aggressive, and—crucially—magnetic. Roche didn’t just become a successful partner. He helped reshape how executive search worked in the United States.

In the early 1960s, Roche got a call from Heidrick about a role for a client. He wasn’t interested. But when he declined, Heidrick countered with a different pitch: open a New York office. Heidrick’s line was equal parts challenge and invitation: “You couldn’t be in a better place to look for a new job than in one of my offices.” Roche took the leap, and Heidrick & Struggles suddenly had a new center of gravity.

Roche’s edge wasn’t a secret database or a clever ad. It was relentless relationship-building. In the mid- to late 1960s, he did what comes naturally to great salespeople: he got face time. Breakfasts, dinners, golf, conversations in living rooms—he even entertained clients at his home in Chappaqua, New York. He treated recruiting like diplomacy: personal, frequent, and always moving the relationship forward.

Underneath the charm was a system. Roche started by hunting for the openings themselves—scouring major corporations for roles that needed filling—then persuading management that he should be trusted to run the search. From there, he’d use the firm’s databank and his corporate contacts to build an initial slate, often 50 or 60 names, and narrow it down through reference work and persuasion.

And he operated with a worldview that, in hindsight, sounds like the operating system of the whole industry: everyone was either “a prospect, a candidate, a reference or a client.”

By the 1970s, that approach was producing staggering output. Roche filled more than 150 positions during that decade, and roughly a quarter of them were president or CEO roles. He wasn’t just matching people to jobs. He was positioning himself—and by extension Heidrick—as an invisible hand in corporate leadership.

Heidrick & Struggles also became, almost accidentally, an incubator for the industry. In the spring of 1955, the firm hired Spencer Stuart, who later left to start his own executive search firm—Spencer Stuart.

Meanwhile, the footprint was spreading. By the late 1950s, Heidrick & Struggles was moving beyond the Midwest. In 1957 it opened offices in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York City—early signs of what would become a global business built on discretion, research, and reputation.

The founders had discovered something profound: at the highest levels of leadership, the stakes were too high and the talent pool too specialized for traditional recruiting. A CEO search isn’t about finding someone who can do the job. It’s about finding the one person who can change a company’s trajectory. And that demanded a different kind of service—part investigator, part matchmaker, part confidant.

III. Building the Modern Firm: Globalization & Expansion (1980s–1990s)

The 1980s were the golden age of executive search. M&A was booming, conglomerates were breaking apart, whole industries were reorganizing—and every shake-up created the same problem at the top: who’s going to run the new thing?

Inside Heidrick & Struggles, that era belonged to Gerard Roche. By 1978, the board was convinced he should be CEO. But Roche didn’t become the kind of chief executive who vanished into meetings and memos. Even after taking the top job, he kept carrying a full search load for two more years—still doing the work, still closing the deals. In the early 1980s, he personally helped move marquee talent across corporate America: Thomas Vanderslice leaving General Electric to run GTE, Edward Hennessy jumping from United Technologies to lead Allied Corporation, and Robert Frederick going from GE to become president of RCA.

While Roche was reshuffling the C-suite, the firm was reshuffling the map.

Heidrick & Struggles had already made a crucial international beachhead in 1968, opening in London—its first office outside the U.S.—and becoming the first executive search firm to secure a retainer from the British government. That early win mattered. It signaled to multinational clients that this wasn’t just an American headhunting shop; it was becoming an institution they could trust across borders.

In the 1980s, the pace accelerated. Over nine years the firm added nine offices across three continents: Boston, Brussels, Dallas, Frankfurt, Hong Kong, Houston, Mexico City, Paris, and Zurich. Growth in Europe was especially strong, and the expansion continued into major Latin American cities as well, with offices in Buenos Aires, Caracas, Lima, Santiago, and São Paulo. Step by step, the business was turning into what clients increasingly demanded: a global network with local relationships.

As the industry professionalized and consolidated, a handful of names began to dominate. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, the market had its shorthand for the giants: the “SHREK” firms—Spencer Stuart, Heidrick & Struggles, Russell Reynolds, Egon Zehnder, and Korn Ferry. All were U.S.-based except Egon Zehnder, headquartered in Switzerland. In other words: the era of the global search oligopoly had arrived, and Heidrick was in the club.

The competition pushed everyone to get sharper. The pitch couldn’t just be, “We know people.” It had to be, “We understand your business.” Heidrick framed its methods around deep work on a client’s strategic, financial, and operational context—because at the very top of the house, the job is never just the job.

And the numbers followed the narrative. Demand for senior talent kept climbing, and by the mid-1990s the firm was riding a powerful wave—worldwide revenues growing rapidly, with particularly strong momentum beginning in 1995.

But what really cemented the mystique of the industry weren’t the office openings or the growth rates. It was the headline hires—the kind that changed how boards thought about leadership.

One of the defining placements of that era was Roche’s 1983 recruitment of John Sculley from PepsiCo to become CEO of Apple. Today, cross-industry CEO moves feel normal. Back then, it helped legitimize a then-radical idea: that leadership skills could transfer—and that the right outsider could redefine an organization.

Roche’s most famous chapter may have come later, and with an unlikely co-star: his longtime rival, Thomas J. Neff of Spencer Stuart. When IBM needed a CEO, the search committee chair, James E. Burke, wanted the widest possible field of candidates. The solution was controversial—pair two rival recruiters, “Tom & Gerry,” to run the assignment, in part to sidestep off-limits restrictions that could narrow the candidate pool. The approach worked. Louis V. Gerstner Jr., one of Roche’s candidates, landed the job.

These wins did more than pad a trophy case. They were proof of what executive search was selling: this wasn’t a commodity transaction, and it wasn’t something you could reliably replicate through internal HR or contingency recruiting. At the very top, the value was judgment, access, discretion—and the ability to convince the right person to say yes.

By the late 1990s, Heidrick & Struggles had become a global powerhouse, with offices on six continents and relationships with many of the world’s largest companies. But structurally, it was still a partnership—an arrangement that brought cohesion and long-term thinking, but also real constraints. The partners now faced a question that would define the company’s next era: stay private and protect the culture that built the franchise, or go public to raise capital, use stock for acquisitions, and give liquidity to partners who had spent decades building the firm.

The choice they made would shape the next quarter-century—and, in a straight line, lead to the 2025 announcement that brought this story full circle.

IV. The IPO Gamble: Going Public in a Private Business (1999)

In April 1999—right at the height of dot-com euphoria—Heidrick & Struggles took the leap. The firm went public on the NASDAQ under the ticker HSII, turning a partnership-era institution into a publicly traded company, and raising capital it could use to grow and acquire.

On the surface, the timing looked perfect. The economy was running hot. Tech companies were racing to scale and suddenly needed grown-up leadership yesterday. Legacy companies, panicked about “going digital,” were hunting for executives who could drag them into the internet age. Everyone was hiring, and the most senior hires were the hardest ones to get right.

The logic for the IPO was clean: more money to expand globally, invest in technology, and diversify beyond pure search. Public currency could also make acquisitions easier, and stock-based compensation could help recruit and retain top talent. And for long-time partners, the IPO offered something the private model couldn’t: real liquidity.

But going public didn’t just change the cap table. It changed the rules of the game.

Executive search is a relationship business with lumpy, timing-sensitive revenue. A CEO search can run for months. A board relationship can take years to earn. The best consultants don’t “scale” the way software scales; they build trust one client at a time, over entire careers. That rhythm is slow, uneven, and often invisible from the outside.

Public markets want the opposite: predictable growth, clean quarter-to-quarter narratives, and momentum you can chart on a line. Suddenly, Heidrick had to answer questions that don’t map neatly onto its actual work. What do you tell analysts when a client delays a CEO search? How do you forecast earnings when your product is the judgment—and the personal networks—of individual partners who can walk out the door?

Most competitors didn’t want that trade. Spencer Stuart stayed private. Egon Zehnder stuck with its partnership model. Their view was simple: the public market structure was a mismatch for a business built on discretion, long horizons, and trust.

Heidrick went the other way—and early on, it looked like it worked. The stock held up, growth continued, and the firm leaned into the advantages of being public: acquisition currency, capital for investment, and equity as a recruiting tool. Demand for senior executives was rising fast, and Heidrick was right in the middle of it.

But the IPO didn’t remove the industry’s biggest fact of life. It just put it under a microscope: hiring is cyclical.

And the moment the cycle turned, the public-company experiment was about to be tested—immediately, and brutally.

V. Dot-Com Crash & The First Crisis (2000–2003)

The dot-com bubble finally broke in March 2000. The NASDAQ Composite peaked at 5,048.62 on March 10—more than double where it had been a year earlier—and then the air came out fast. By 2001, the deflation wasn’t a “correction.” It was a wipeout. Many dot-coms burned through their venture and IPO cash without ever reaching profitability, and then simply stopped trading.

For Heidrick & Struggles, it was the nightmare scenario: the firm had gone public right near the top, riding a boom in executive hiring, and then watched demand disappear almost overnight.

And it wasn’t just the startups themselves. When the dot-coms collapsed, the ecosystem around them collapsed too—law firms, banks, recruiters, consultants, vendors. In the San Francisco Bay Area alone, four out of five dot-coms went out of business in 2000 and 2001, costing about thirty thousand direct internet jobs. The kicker is that these weren’t entry-level roles. They were exactly the kinds of high-paying leadership positions that feed an executive search firm.

The financial impact showed up quickly. North America revenue fell to $70.1 million from $74.8 million in the prior year’s first quarter, a 6 percent decline. But the more important number was the operating margin, which slid to 10.4 percent from 17.5 percent. The problem wasn’t mysterious: revenue was down, while costs were sticky. Heidrick had hired aggressively over the prior 12 months to meet boom-time demand, so base salary costs were higher right as the work slowed. On top of that, the allowance for doubtful accounts jumped—another symptom of clients and candidates living through a cash crunch.

Then came September 11, 2001, and the downturn deepened. The New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq closed for four sessions. When markets reopened on September 17, the Dow dropped 7.13 percent—684 points—one of the worst single-day declines in its history. By the end of the week, it was down 14 percent, the biggest-ever weekly loss at the NYSE.

Inside Heidrick, the public-company structure that had looked like an accelerator in 1999 now felt like a constraint. The firm had expanded consultants and offices to match the boom. In a people business, that’s mostly fixed cost. When the searches stop, the cost base doesn’t magically shrink with them—unless you do the thing no one wants to do.

Layoffs.

In executive search, that’s not like trimming a sales team. Your consultants are the product. They’re also the relationships. Cutting them is culturally traumatic and strategically risky. But the quarterly math of public markets doesn’t care about trauma. It cares about margins.

The first crisis made the core dynamic impossible to ignore: executive search has enormous operating leverage in both directions. When hiring is booming, profits can surge. When hiring freezes, the pain multiplies. And public investors—especially in the early 2000s—weren’t exactly patient about “waiting out the cycle.”

Heidrick survived. But it didn’t escape unchanged. The scars from this period crystallized the question that would haunt, and ultimately reshape, the firm for the next two decades: if pure search is this volatile, what do you build alongside it so the company isn’t fighting for oxygen every time the economy turns?

VI. Rebuilding & The Leadership Consulting Pivot (2004–2008)

Coming out of the dot-com wreckage, Heidrick’s leadership faced an uncomfortable, clarifying question: was there any way to make this business less hostage to the hiring cycle—without giving up what made the firm valuable in the first place?

They decided the answer wasn’t to abandon search. It was to wrap something around it.

The bet was leadership consulting. The reasoning was straightforward: if boards and CEOs already trusted Heidrick to discreetly find the next leader, why wouldn’t they also trust the firm to help evaluate that leader, develop the team around them, and shape the culture they’d inherit?

In other words, move up the value chain—from identifying leaders to predicting whether they’d actually succeed. The firm leaned into the idea that more “science” could sit alongside the art of relationships: more structured assessment, more data, more repeatable methods, and more ongoing engagement with clients.

So Heidrick started building out services like executive assessment, leadership development, and succession planning. The goal wasn’t just new revenue lines. It was a different relationship with the client: fewer one-and-done searches, more recurring advisory work that kept Heidrick in the room between big hires.

The economics helped, too. Consulting work tends to be less tied to expensive senior rainmakers and less sensitive to the timing of a single placement. And it’s often stickier: once you’ve assessed a leadership team and mapped a company’s culture, you’re not a vendor anymore. You’re part of the decision-making fabric.

By the mid-2000s, the pivot seemed to be taking hold. Heidrick returned to profitability, the stock climbed off its post-crash lows, and clients responded to the broader offering.

But just as the firm was finding its footing again, an even bigger shock was coming—one that would test not just the strategy, but whether executive search could ever truly work as a public company.

VII. The Great Financial Crisis: Near-Death Experience (2008–2010)

In 2008, the world didn’t just slow down. It seized up.

The Great Financial Crisis began in the U.S. housing market, fueled by a toxic mix of runaway speculation, lax underwriting, subprime lending, and regulatory blind spots. When that system cracked, it didn’t stay contained. Credit froze, confidence evaporated, and the shock raced through the global economy.

For Heidrick & Struggles, this downturn wasn’t a repeat of the dot-com crash. It was worse.

By then, financial services had become one of the firm’s most important practice areas. And suddenly, many of the very institutions that had been steady sources of marquee search work were in triage mode—or disappearing entirely.

The inflection point came in September 2008, when Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy. Markets fell hard. Bank runs hit in multiple countries. And across industries, executive hiring essentially stopped. Searches that were in motion got paused. New searches didn’t launch. Boards that had been ready to make leadership changes chose the least risky option available: stick with the current team and wait out the storm.

The impact showed up fast and painfully. Revenue fell more sharply than it had in the early 2000s. The stock sank below $10, and the market cap cratered. For a firm that had gone public at the peak of the previous cycle, the moment felt like cruel symmetry: once again, the public markets were judging a relationship business on the worst possible quarter.

There was also a broader, uncomfortable parallel playing out in the background. In finance, the crisis reignited debates about whether shifting from partnership-like models to public-company structures—and emphasizing trading over long-term stewardship—had changed behavior in ways that made the system more fragile. Heidrick didn’t cause the crisis, of course. But it was living its own version of the same tension: what happens when a long-horizon, trust-based model is forced to perform under short-horizon expectations?

Inside the company, the question turned existential. The dot-com bust had felt like a freak event. Now, less than a decade later, Heidrick was taking an even bigger hit. If executive search was going to get punched in the face every five to ten years, could it ever be a good fit for the public markets?

The response was survival mode. Costs came out everywhere they could: layoffs, compensation deferrals, an almost total hiring freeze, and office consolidations. Every line item was questioned. In a business where “capacity” is human beings, the cuts weren’t just financial—they were emotional and cultural.

But in the middle of the retrenchment, leadership held the line on one strategic choice: they wouldn’t abandon diversification into consulting. If anything, they leaned in harder. The crisis had validated the lesson of the early 2000s: pure search was simply too cyclical. If Heidrick wanted to stop gasping for air every time the economy turned, it needed more work that clients would buy in good times and bad—assessment, advisory, and leadership services that lived between the big hiring moments.

The recovery, when it came, was slow. But the firm that emerged had a tougher cost structure and a clearer sense of what it had to become. The near-death experience of 2008 to 2010 didn’t just shape that era—it set the logic for the decade that followed.

VIII. The Digital Disruption Era: LinkedIn & The Existential Threat (2010–2015)

Just as Heidrick was climbing out of the financial crisis, a different kind of threat took shape—one that didn’t look like a recession at all. It looked like a website.

LinkedIn had launched back in 2003. But by the early 2010s, it was turning into something that felt, to a lot of people, like an existential weapon: a massive, searchable directory of professionals that anyone could access with a subscription. And with LinkedIn Recruiter, the pitch to companies was almost offensively simple: why hire a firm to find people when you can just… find them?

The disruption story practically wrote itself. Why pay an executive search firm a third of an executive’s first-year compensation when your internal recruiting team can run searches on LinkedIn all day? For decades, recruiters’ “black books”—their hard-won knowledge of who was where, who was promotable, and who might be movable—had been the scarce asset. Now it looked like that scarcity was gone. Anyone with a credit card could type, filter, and message.

Public market investors bought the narrative. Valuation multiples compressed, and industry pundits started writing obituaries for executive search. If you like clean tech-disruption arcs, this one had everything: high fees, opaque process, relationship-driven gatekeepers, and a platform that promised transparency and efficiency.

And then something unexpected happened.

The high end of the market didn’t break.

Because LinkedIn could help you find names. It couldn’t reliably solve the actual problem boards were trying to solve.

At the highest levels, the work is less “sourcing” and more risk management—confidentiality, politics, persuasion, and judgment. A routine director-level hire might be fine with a DIY LinkedIn process. But a CEO search is not a sourcing problem. It’s a governance problem. A board seat isn’t just a role to fill; it’s a bet on credibility, chemistry, and what happens in the room when the company is under pressure.

That’s also where the modern CEO job was getting harder. Boards weren’t just asking for operators. They were asking for leaders who could navigate shareholder pressure, activist scrutiny, digital transformation, and growing expectations around ESG—while staying ahead of succession planning, strengthening the C-suite, and building boards that actually benefit from diversity of thought and background. In that context, “here’s a list of candidates” is table stakes. What clients needed was someone to run a process with discretion, surface real trade-offs, and help the board get to conviction.

Heidrick positioned itself accordingly: a firm with a global track record at the top of the house, using data-driven advisory work and a deep network to help clients build inclusive, sustainable leadership teams. The message was clear: the value isn’t access to a database. The value is what you do with the information—and whether you can get the right person to say yes.

The firm also emphasized the scale and repeatability of its relationships: it worked with more than 70% of Fortune 1000 companies across sectors around the world, applying methodologies refined through decades of leadership work. Not just to “fill roles,” but to help clients find leaders, strengthen teams, and shape cultures built for performance.

Strategically, Heidrick’s response wasn’t to pretend LinkedIn didn’t exist—or to try to out-LinkedIn LinkedIn. It leaned harder into what software couldn’t replace: advisory value, judgment, and integrated solutions. The firm invested in its own technology platforms and data analytics, not as a substitute for human decision-making, but as an amplifier of it.

And it kept pushing into adjacent work where the firm’s credibility mattered and the engagement could extend beyond the hiring moment: culture shaping, diversity and inclusion, organizational acceleration. In these businesses, technology was a tool in the toolkit—not the thing that replaced the toolkit.

The deeper lesson of the LinkedIn era was subtle: disruption in professional services rarely lands the way it does in product businesses. Technology tends to wipe out the commoditized middle first—the work that’s mostly process and access. But at the top, where decisions are sensitive, reputations are on the line, and the downside of a mistake is enormous, judgment still commands a premium. The value proposition survived. The challenge was making it unmistakable.

IX. The Modern Transformation: Krishnan Rajagopalan Era (2015–2021)

By the mid-2010s, Heidrick had proven it could survive shocks. The bigger question was whether it could outgrow them.

That’s where Krishnan Rajagopalan came in. He joined Heidrick in 2001 as a search consultant, then rose through the operating core of the firm: Global Practice Managing Partner for Business/Professional Services from 2007 to 2010, then Technology and Services from 2010 to 2014. In 2017, he stepped into the top job as acting President and CEO from April 3 to July 6.

When he took the role, Rajagopalan framed it as both continuity and momentum: “It is an honor to lead Heidrick & Struggles. Tracy has been a superb mentor and partner. I look forward to working with Tracy, the Board, the executive team, and the entire organization to continue to develop and execute our strategy.”

The strategy itself was the real headline. Under Rajagopalan’s leadership, Heidrick executed what may have been its most consequential transformation since the IPO: shifting from “a search firm that also does some consulting” into a broader leadership advisory platform.

One of the earliest, clearest signals was culture. Heidrick & Struggles International announced the acquisition of Senn-Delaney Leadership Consulting Group, LLC (Senn Delaney), positioning it as the global leader in corporate culture shaping. The transaction closed on December 31, 2012, and Heidrick said it expected the deal to be accretive to earnings per share in 2013. Senn Delaney had spent 34 years advising Global 1000 and Fortune 500 companies, along with major non-profits and government entities, on building what it argued was a core driver of performance: a thriving culture.

Heidrick paid $53.5 million at closing for 100 percent of the equity, with the potential for up to $15.0 million of additional cash consideration tied to earnings milestones over the first three years.

Management didn’t describe it like a bolt-on. They described it like a strategic click: “This is a marriage of two premium brands that both pioneered their industries and both serve the top executives of leading organizations. Culture shaping is a service that appeals directly to our target market—C-suite and Board-level executives—making it a highly complementary offering to our premium Executive Search and Leadership Consulting services. At the same time, Senn Delaney gains access to the resources and global reach of the Heidrick & Struggles' platform which we believe will accelerate its growth.”

And Heidrick kept going.

In October 2015, it acquired London-based leadership consultancy Co Company. In February 2016, it acquired Decision Strategies International (DSI), another leadership advisory firm. In August 2016, it acquired JCA Group, a London-based executive search advisory firm. The pattern was consistent: add capabilities that kept Heidrick in the conversation before, during, and after the hire—not just at the moment a role opens.

But the most transformative move came in 2021, when Heidrick stepped into an entirely new category: on-demand talent.

Heidrick closed the acquisition of Business Talent Group (BTG), a marketplace for high-end independent talent on demand. Financial terms weren’t disclosed in the announcement, but the strategic logic was: BTG extended Heidrick’s suite of executive talent solutions, built on a two-year exclusive collaboration that began in 2019, and gave the firm a serious foothold in project-based, independent executive work.

Heidrick described the combination as a first-of-its-kind spectrum: on-demand independent professionals, interim executives, and permanent placements, alongside consulting services. BTG generated approximately $50 million in revenue in 2020 and was acquired for an initial consideration of $32.6 million paid in the second quarter of 2021, with an anticipated future payment in 2023 contingent on hitting agreed performance targets.

Rajagopalan positioned the move as a response to a world that had changed faster than anyone expected: “Heidrick & Struggles was a forerunner of the executive search industry when the firm was founded more than 65 years ago. The seismic changes over the past year have accelerated the future of work and underscored the importance of agile leaders and workforces. We are excited to be the first global leadership advisory firm to enter the on-demand, independent talent space and partner with BTG, a leader and pioneer of the high-end independent talent marketplace.”

By the end of Rajagopalan’s tenure, Heidrick looked fundamentally different from the pure-play search firm that had gone public in 1999. It now operated as three distinct businesses under one roof: Executive Search, Heidrick Consulting (including culture shaping, leadership assessment, and organizational effectiveness), and On-Demand Talent.

And when Rajagopalan handed the baton, he framed the era the way you’d expect from someone who spent years trying to make a cyclical business more resilient: “Leading Heidrick & Struggles has been a privilege, and I want to thank the global team for their support on this journey. I am incredibly proud of what we have achieved, how we have transformed the business through the diversification of our offerings, the impact we have had on clients, the growth and expanded diversity of our team, and the culture that we have built. I am confident that Tom and Tom will lead Heidrick & Struggles to its next chapter of growth and client impact.”

X. The Current Chapter: CEO Transition & Return to Private Ownership (2021–Present)

In early 2024, Heidrick made it official: CEO Krishnan Rajagopalan, after more than 23 years with the company, was retiring. He would step down as President and CEO and leave the Board effective March 4, 2024, then retire from the firm on April 1, 2024—staying on as an advisor afterward.

The succession plan was a tell.

Heidrick appointed Thomas L. Monahan III as Chief Executive Officer, and promoted Tom Murray, the Global Managing Partner of Executive Search, to President. It was a deliberate pairing: one leader steeped in the core search franchise, and one brought in to keep pushing the company’s transformation.

Monahan wasn’t a career headhunter. Before Heidrick, he was CEO and Chairman of CEB, a C-suite advisory business built on technology-enabled research and tools. Under his leadership, CEB grew to nearly $1 billion in revenue and about $3 billion in enterprise value, serving more than 10,000 companies globally, including 90 percent of the Fortune 500.

That choice—an outsider with deep experience in tech-enabled services—signaled where the board thought the puck was going. Search firms weren’t just competing on access anymore. They were competing on data, analytics, process, and the ability to turn “leadership” into a repeatable advisory product.

And the business, at least on the surface, was working. Under Monahan, performance strengthened. Heidrick reported $1.1 billion in annual revenue for 2024, up seven percent from the prior year, with all three lines—Executive Search, On-Demand Talent, and Heidrick Consulting—growing year over year.

“We finished 2024 on a strong note, highlighted by a fourth quarter performance that exceeded our expectations,” Monahan said. “As we move into 2025, our team is energized and focused on the significant opportunity for client impact in a complex, volatile world.”

Fourth quarter results reinforced the theme: consolidated net revenue rose 9.1% to $276.2 million versus $253.2 million a year earlier, driven by growth across each business line.

Then came the announcement that brought the story full circle.

Heidrick & Struggles said it had entered into a definitive agreement to be acquired by a consortium led by Advent International and Corvex Private Equity, alongside several leading family offices. The new investor group would also include significant investment from Heidrick leaders themselves. The all-cash deal valued the company’s equity at approximately $1.3 billion and would return Heidrick to private ownership—this time with materially more equity participation by current and future partners and leaders, a structure designed to support faster growth and greater client impact.

The terms were straightforward: stockholders would receive $59.00 per share in cash, a premium of approximately 26 percent to Heidrick’s 90-day volume-weighted average share price.

The transaction ultimately closed with support from a broader set of strategic investors, including Salem Capital Management, Mousse Partners, TF Cornerstone, HighSage Ventures, and Barcliff Partners. Heidrick described it as one of the most consequential transformations in its 70-year history—and a foundation for an ambitious, multi-year growth strategy.

Operationally, the company would remain Heidrick & Struggles. But the governance and incentives would change. In connection with the closing, Heidrick intended to appoint Carmine Di Sibio—an Operating Partner at Advent and former Global Chair and CEO of EY—as Chairman of the Board of Managers. Other board members would include Monahan, representatives of Advent and Corvex, members tied to the strategic investors, and independent directors.

Just as important as who was buying Heidrick was who was buying in. Certain Heidrick leaders and partners committed to a substantial co-investment as part of the transaction, and the new capital structure supported a new, wholly incremental, partner and leader equity plan—explicitly designed to align ownership and incentives around the firm’s ambitions for client impact and colleague opportunity.

As of December 10, 2025, Heidrick & Struggles International, Inc. was private again.

The cycle was complete. Twenty-six years after going public, Heidrick was returning to private ownership—but as a fundamentally different company than the pure-play search firm that IPO’d in 1999.

XI. The Business Model Deep Dive: How Heidrick Actually Makes Money

If you want to understand why Heidrick kept reinventing itself—why it pushed into consulting, why it bought an on-demand marketplace, and ultimately why it decided to leave the public markets—you first have to understand how the money gets made in executive search.

At its core, Heidrick & Struggles is a leadership advisory firm. It sells three things: Executive Search, Heidrick Consulting, and On-Demand Talent. And it delivers them the way most professional services firms do—through people. More than 500 consultants, spread across cities around the world, are the “capacity” of the business.

The classic engine is the placement fee. In traditional executive search, Heidrick typically charges about 30–35% of a candidate’s first-year compensation. That pricing makes sense when the role is high-stakes and expensive to get wrong: CEOs, board members, and other mission-critical leaders where the process has to be deep, discreet, and defensible.

Most of that work is done on a retained basis. The client pays in stages—often three installments: when the search begins, at a midpoint, and when it concludes—rather than only paying if someone is hired. That’s the big distinction versus contingency recruiting. Retained search funds the research, the outreach, and the long, careful process. But it also exposes the firm to a different kind of risk: searches can stretch, stall, or fail to close on the original timeline, and that lumpiness is exactly what makes forecasting hard.

In the most recent twelve-month period referenced here, the biggest revenue contributor was Executive Search in the Americas—$556.9 million, or about half of total revenue. That tells you something important right away: despite all the diversification, search is still the gravity well.

Everything in this model ultimately comes back to the economics of individual consultants. Revenue per consultant and utilization are the heartbeat metrics. Senior partners with real networks and trusted client relationships can command premium fees and keep a steady flow of assignments. Less senior consultants need years to build that same book. That creates the upside—top performers can carry a lot of the firm—and the structural vulnerability too: when your rainmakers are your product, key-person dependency is never theoretical.

The newer businesses follow different rules. On-demand talent provides clients with independent professionals for interim leadership roles and critical, project-based initiatives. Consulting brings in work like leadership assessment and development, team and organization acceleration, digital acceleration and innovation, diversity and inclusion advisory, and culture shaping. These offerings aren’t priced like “a third of someone’s salary.” They’re sold more like advisory and project work, with different cycles and different margin profiles.

And that’s the point of the whole transformation. Diversification wasn’t a branding exercise—it was a direct response to two structural problems in pure search: cyclicality and margin pressure. Consulting can be more recurring and less tied to whether hiring is booming. On-demand is more transactional and faster-moving, creating a different rhythm of revenue.

If you’re tracking Heidrick’s business going forward, two indicators matter more than almost anything else: (1) revenue per consultant in Executive Search, which is a clean proxy for pricing power and productivity, and (2) how much of total revenue comes from non-search lines, which tells you whether diversification is actually reducing the firm’s dependence on the hiring cycle.

XII. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

To understand Heidrick’s competitive position, you have to look at two things at once: the structure of the executive search industry, and the specific advantages Heidrick has managed to build and defend over time.

Porter’s Five Forces:

Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM-HIGH

The big firms—the old SHREK set—have real advantages in brand, reach, and credibility. But the front door to this industry is basically unlocked. A boutique can start with sector or functional specialization, a tight circle of relationships, and increasingly, smart use of AI and tools that make sourcing and outreach faster. In other words: it’s easy to start a search firm. What’s hard is earning the right to run CEO and board searches, where track record and trust compound over decades.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: HIGH

In executive search, the “suppliers” are the consultants. They’re the product, and the relationships they carry are portable. A top partner can leave and, if clients follow, so does revenue. That makes retention one of the most existential challenges in the entire model. Heidrick’s return to private ownership—with a heavier emphasis on meaningful partner equity—directly targets this dynamic.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM

Big corporate clients can negotiate, especially when they have ongoing, high-volume relationships. But at the very top of the house—CEO, board, and other mission-critical roles—price sensitivity drops dramatically. When a hire can shape the fate of a multi-billion-dollar enterprise, the search fee rarely decides the outcome.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM-HIGH

LinkedIn, internal talent teams, and newer platforms are real substitutes—but mostly for work that’s closer to “find me qualified people.” For commodity roles, technology can absolutely replace a lot of what used to require a search firm. Heidrick’s defense is the high end: confidential, high-stakes leadership decisions where access is only part of the job, and judgment, discretion, and process management are the real product. Heidrick positions itself as a global leadership advisory and on-demand talent provider, working with more than 70% of Fortune 1000 companies across sectors worldwide.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a brutally competitive market. The SHREK firms fight each other, Korn Ferry brings scale and breadth, and hundreds of boutiques nip at specific industries and functions. (For context: in 2023, Korn Ferry was the largest executive recruitment and leadership consulting firm operating in the Americas region, with $1.78 billion in revenue.) Competition is constant, and differentiation is often as much about who the client trusts as what the firm claims to do.

Hamilton’s Seven Powers:

Scale Economies: LIMITED

This is not a software business. You can build leverage in shared research, technology infrastructure, and global coordination, but the economics still come down to individual consultant productivity.

Network Effects: MODERATE

A larger database and broader client coverage help. More relationships create more opportunities. But it’s not viral or exponential in the way true platform businesses are.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

Traditional firms were slower to adopt technology; pure-tech players often lack trust, confidentiality, and boardroom credibility. Heidrick’s hybrid stance—technology-enabled process plus human judgment—positions it against both ends of that spectrum.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-HIGH

When a firm has run multiple searches for a company, understands the board dynamics, and has a deep read on culture, switching isn’t frictionless. Clients may still change providers, but they give up accumulated context that’s hard to replace.

Branding: HIGH

This is one of Heidrick’s strongest powers. A 70-year reputation and a blue-chip client roster act as shorthand for discretion and quality—especially for high-stakes work. Heidrick emphasizes data-driven methodologies built over decades of engagements, with the goal of helping clients find leaders, build diverse and inclusive cultures, and strengthen teams.

Cornered Resource: LOW-MODERATE

Elite consultants and their networks are valuable, but they aren’t locked in place. The firm has proprietary methodologies and data assets, but no single “cornered” resource that competitors cannot, in theory, replicate over time.

Process Power: MODERATE

This is where Heidrick’s accumulated experience can compound. Thousands of searches, proprietary assessment tools, and pattern recognition built over decades create real process advantages. The culture shaping practice rooted in Senn Delaney also brings proprietary insights and tools aimed at helping organizations shape performance by shaping culture.

Verdict: Heidrick’s primary competitive advantages are Branding and Switching Costs, built through embedded board-level relationships. The ongoing challenge is protecting those advantages as technology commoditizes more of the lower end of the market.

XIII. The Competitive Landscape & Market Dynamics

The executive search industry is still shaped by the old “SHREK” giants—but the real competition depends on what part of the market you’re in. CEO and board work plays by one set of rules. Everything below that starts to look more like a knife fight: faster cycles, more substitutes, and more pressure on fees.

Most industry sources describe the Big 5 as Korn Ferry, Spencer Stuart, Heidrick & Struggles, Russell Reynolds Associates, and Egon Zehnder. They’re the global brands with the broadest footprints, the longest client lists, and decades of credibility at the top of the house.

Korn Ferry: The Largest

Korn Ferry is the heavyweight. It has held the top spot in industry rankings, and it got there by doing something even more ambitious than Heidrick: buying its way into a full-spectrum talent and HR solutions platform. A long run of acquisitions (including Hay Group and Pivot) helped make Korn Ferry the only firm in this peer set with revenue above the billion-dollar mark.

That diversification is a superpower and a trade-off. On one hand, it makes Korn Ferry less dependent on the boom-and-bust rhythm of search. On the other, the broader it becomes, the easier it is for the brand to feel less like “premium executive search” and more like a general talent conglomerate.

Spencer Stuart: The Private Powerhouse

Spencer Stuart is the clean counterpoint. It’s more traditional, more partnership-driven, and famously private. It may not always win on size or flash, but it has built a reputation for doing the most sensitive work—especially at the board level—exceptionally well.

And its decision to stay private is the important part. Without quarterly earnings pressure, Spencer has been able to protect the partnership culture and premium positioning that public-company dynamics can strain. In the context of Heidrick’s story, Spencer is the proof that the classic model can still work—if you don’t force it to perform like a public-market growth stock.

Egon Zehnder: The Partnership Model

Egon Zehnder pushes the partnership idea even further, with a compensation structure designed to reward collaboration over individual production. Based in Switzerland, it remains the most distinctive of the big firms culturally—less “eat what you kill,” more institutional team sport—which shapes how it competes and how it retains talent.

Russell Reynolds: The Return to Private

Russell Reynolds offers a different kind of signal: it went through its own public-to-private journey, showing that Heidrick isn’t the only major firm to wrestle with the fit between public markets and a relationship business.

Then there’s the rest of the field—and it’s getting more dangerous.

Boutiques have grown quickly by going deep instead of broad, taking share in sectors like technology, healthcare, and financial services where specialization can beat scale. And platforms like LinkedIn and SeekOut have made it far easier to compile lists of “qualified” candidates, commoditizing the lower end of the market. The result is a squeeze: premium firms have to keep moving the conversation away from “we can find people” and toward what clients actually pay for at the top—judgment, discretion, and running a process boards can trust.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case:

Proven Survivor

Heidrick has already lived through the disasters that kill most professional services firms: the dot-com crash, the Great Financial Crisis, the “LinkedIn will replace you” era, and COVID-19. Each time, it adjusted—cutting costs when it had to, and expanding the offering when the core model proved too volatile.

Transformation Working

The diversification push has made the business feel less like a single-cycle bet on executive hiring. Search is still the anchor, but consulting and on-demand talent have given Heidrick more ways to stay relevant between big placement moments. That shift has shown up in results, including consulting net revenue growth of 11.5% in 2023 compared to the prior year.

Irreplaceable at the Top

For CEO, board, and other mission-critical roles, the work still isn’t “find me names.” It’s confidentiality, process, persuasion, and judgment—often in politically delicate situations where the downside of a mistake is enormous. Technology can accelerate the process, but it hasn’t replaced the human layer at the top end.

Secular Trends

The world is demanding more from leaders: culture transformation, leadership development, DEI, and ESG expectations that now sit close to the board agenda. Those themes aren’t one-off fads—they’re ongoing mandates, and they map directly to the advisory lines Heidrick has spent years building.

Return to Private Ownership

“With the support of Advent International, Corvex Private Equity, a distinguished network of long-term investors, and substantial investment from Heidrick & Struggles partners and leaders, we will be positioned to create even more value for our clients and our colleagues. This new platform will allow us to strengthen our world-class search business and the critical advisory and talent solutions our clients rely on.”

The move back to private ownership also changes the operating environment. Less quarterly pressure can mean more freedom to invest for the long term—especially in talent, technology, and integrated offerings that don’t always pay off neatly inside a single reporting cycle.

The Bear Case:

Structurally Challenged Model

Executive search is still cyclical. The barriers to entry remain low. And the biggest risk hasn’t changed: the consultants are the asset, and they can leave.

Technology Commoditization Continues

AI and analytics keep getting better. Even if the very top of the market stays relationship-driven, the band of roles that can be “good enough” with tools and internal teams may keep moving upward over time.

Key Person Risk

Heidrick may have a global brand, but the work is still won and delivered by individuals. If a top producer walks, clients can walk with them. That’s not a hypothetical—it’s a permanent feature of this industry.

Market Maturity

Executive search is a mature category. It can be lucrative, but it’s not a natural “high-growth forever” story. The easy expansion years are behind the industry.

Competition Intensifying

Specialist boutiques can beat the large firms in narrow lanes through focus and speed. Platforms keep pressuring the middle. And the large global firms keep colliding with each other over the most premium assignments.

What to Watch (Key KPIs):

1. Revenue per Consultant in Executive Search - A clean read on pricing power and consultant productivity—the core engine of the model

2. Non-Search Revenue as Percentage of Total - The simplest test of whether diversification is real, and whether the firm is meaningfully less exposed to the hiring cycle

XV. Lessons for Founders, Investors & Operators

Heidrick & Struggles isn’t just a case study in executive search. It’s a case study in what happens when you take a relationship business, bolt it to a quarterly earnings machine, and then run it through recessions and disruption. A few lessons fall out pretty cleanly:

The Public-Private Tension

Some businesses are structurally better suited to private ownership. People-intensive, relationship-based firms with lumpy revenue and high cyclicality don’t naturally produce the smooth, forecastable performance public markets reward. The fact that Heidrick ultimately returned to private ownership—and that close competitors like Spencer Stuart and Egon Zehnder stayed private all along—suggests this wasn’t just bad timing. It may have been a fundamental mismatch.

Surviving Disruption

When LinkedIn arrived, a lot of people wrote the obituary for executive search. What actually happened was more nuanced, and more instructive: technology disrupted from below. It commoditized sourcing and made “finding names” easier. But at the highest levels—CEO, board, the most politically sensitive, reputation-on-the-line hires—judgment, discretion, and trust didn’t become less valuable. They became the differentiator. The winning response wasn’t to fight the tools. It was to use them, while leaning harder into what software still can’t do.

Business Model Evolution

Pure-play models get pressured first. Diversification and reinvention aren’t vanity projects; they’re survival strategies. Heidrick’s shift from search to leadership advisory to on-demand talent shows how a company can change the shape of its revenue and the depth of its client relationships without abandoning its core identity.

Brand as Moat

In trust-based businesses, reputation compounds. Founded in 1953 by Gardner Heidrick and John Struggles in Chicago, the firm helped pioneer retained executive search and grew into a premier provider serving more than 70% of Fortune 1000 companies across major sectors worldwide. In this market, that kind of track record isn’t marketing. It’s a real asset that newcomers can’t copy quickly, no matter how good their tech is.

The Talent Challenge

When your people are the product, retention isn’t an HR issue—it’s the business. The return to private ownership, with a heavier emphasis on meaningful partner equity participation, is a direct attempt to solve the core risk: your rainmakers can walk, and the relationships can walk with them.

Cyclicality Management

If your core revenue line is tied to hiring, you have to plan like downturns are guaranteed—because they are. Diversifying revenue streams helps, but so does keeping costs flexible and maintaining discipline in the boom years. The firms that staffed up and expanded too aggressively in the late 1990s and mid-2000s learned the hard way that when the cycle turns, it turns fast.

The Relationship Economy

For all the disruption of the past two decades, the high-stakes end of this market still runs on trust. Technology can widen the top of the funnel. It can’t sit in the boardroom, manage the politics, protect confidentiality, and help a company reach conviction on a decision that can define the next decade. That’s why executive search didn’t die. The job was never just to find people. It was to help pick the right one.

XVI. Epilogue: The Future of Leadership Advisory

As Heidrick & Struggles begins its new chapter under private ownership, the industry it helped create keeps moving—and so does the definition of leadership itself.

The CEO job is changing in real time. Remote and hybrid work have rewired how teams operate. Stakeholder capitalism has widened the scoreboard beyond quarterly earnings. Purpose-driven leadership has shifted from nice-to-have to expectation. And a generational handoff is underway, reshaping what executives want from work and what boards demand from the people they hire.

In that world, AI is becoming a bigger part of the search process—but also a clearer example of where technology ends and judgment begins. Algorithms are excellent at surfacing candidates, mapping networks, and spotting patterns in data. What they don’t do well is the part that actually keeps boards up at night: the high-stakes, human questions. Will a brilliant technologist thrive inside a legacy culture? Can a private equity-hardened operator handle the scrutiny and cadence of a public company board? Those calls still depend on context, credibility, and lived experience—especially when confidentiality and politics are part of the assignment.

“We, alongside Advent and our strategic investment partners, have deep conviction in the company's significant growth opportunity. We look forward to investing in new technologies and capabilities that amplify the meaningful value Heidrick & Struggles' exceptional people deliver to clients around the world.”

The generational shift may be the most profound change of all. As millennials and Gen-Z leaders rise into the C-suite, expectations around flexibility, identity, transparency, and values are colliding with older governance norms. The firms that can translate those shifts—without losing the rigor and discretion that top-of-house decisions demand—will be the ones that stay indispensable.

That’s the bet behind the transaction: private ownership gives Heidrick a foundation to pursue an ambitious multi-year growth strategy and further scale its ability to build differentiated, deep, durable global client relationships. The company described it as one of the most consequential transformations in its 70-year history. More freedom to invest. Different incentives. Less quarter-to-quarter theater. More room to build.

Will executive search exist in 20 years? Almost certainly. But it won’t look like the “black book” era, and it won’t be purely a technology product, either. The winners will blend what machines are good at—speed, coverage, analysis—with what clients still pay a premium for: discretion, persuasion, and judgment when the downside of getting it wrong is enormous.

For Heidrick & Struggles, returning to private ownership is both a conclusion and a beginning. The public-market experiment—with all its pressure, visibility, and constraints—has ended. But the core mission hasn’t changed: helping organizations find and develop the leaders who will shape their futures, just as Gardner Heidrick and John Struggles set out to do when they opened their Chicago office 72 years ago.

So this isn’t really an ending. It’s the next chapter—written the same way this entire industry was built: one relationship, one high-stakes decision, one leadership team at a time.

XVII. Further Reading & Resources

Top Long-Form References:

-

Heidrick & Struggles SEC Filings: 10-K annual reports (2008, 2015, 2021, 2024) for the clearest view of the firm’s financial history, strategic pivots, and how it explained itself to the public markets — available at investors.heidrick.com

-

"The Headhunters" by John Byrne (1986): The classic industry history, including rich detail on how executive search evolved and how firms like Heidrick helped professionalize what used to be informal, relationship-based hiring

-

Heidrick & Struggles Investor Presentations: Especially the CEO transition materials (2015, 2021, 2024), which show how leadership framed the company’s strategy, diversification, and priorities over time

-

Hunt Scanlon Media Coverage: Industry reporting and analysis on executive search, leadership advisory, and the competitive dynamics shaping the modern market

-

Bloomberg/WSJ Coverage: Reporting from the key stress-test eras—financial crisis survival (2008–2010) and the LinkedIn disruption narrative (2011–2015)

-

AESC (Association of Executive Search and Leadership Consultants) Reports: Industry standards, ethical guidelines, and market data from the trade body most closely associated with retained search

-

McKinsey Quarterly: “The future of professional services” coverage for broader context on how people-based, trust-driven firms adapt to technology and changing client expectations

-

LinkedIn Talent Solutions Reports: Useful for understanding how the recruiting tech stack evolved—and why “sourcing” got cheaper even as high-stakes leadership judgment stayed scarce

-

Private Equity International: Coverage of PE-backed roll-ups and consolidation strategies in executive search and adjacent talent services

-

Advent International and Corvex announcements (October 2025): Primary-source details on the take-private transaction, investor rationale, and the structure of the deal that brought Heidrick back behind closed doors

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music