Horace Mann Educators Corporation: Teaching the Teachers

Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a scene that plays out every September across America: yellow school buses rolling into parking lots, students clutching new backpacks, and teachers unlocking classroom doors for another year of shaping young minds. It’s a familiar tableau. The less visible part is what comes after the bell: teachers still have to live a financial life like everyone else, just often on tighter margins. Auto insurance for the commute. Home coverage for the first modest house. A retirement plan that has to last decades after the final bell.

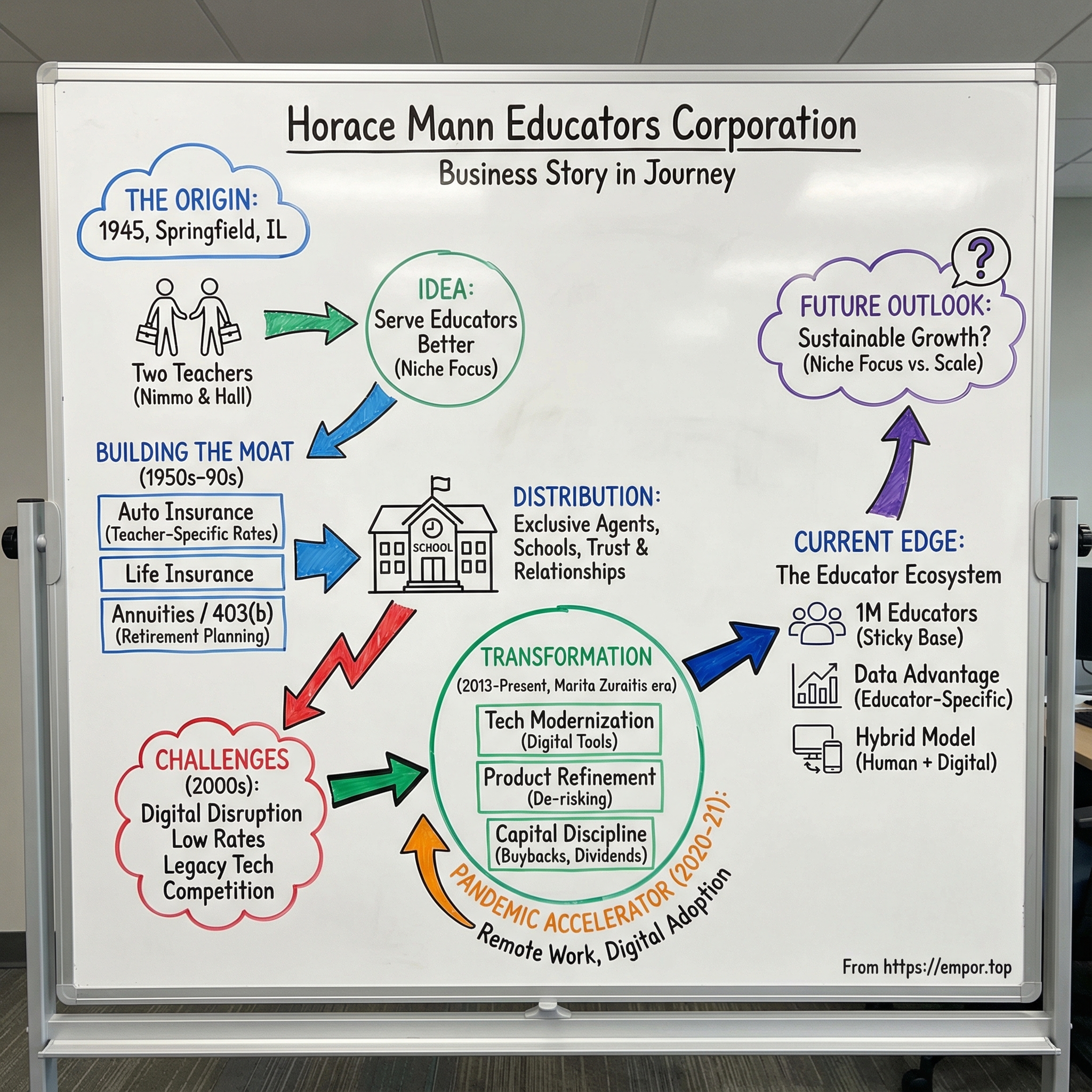

Horace Mann exists because, in 1945, two teachers in Springfield, Illinois looked around and realized something simple: teachers were being overlooked. They wanted quality, affordable auto insurance designed for educators, sold by people who understood educators. Over time, that mission expanded into something broader—helping teachers, administrators, and school employees protect what they have today and plan for what comes next.

Today, Horace Mann Educators Corporation is a peculiar creature in the insurance landscape: a national multiline insurer dedicated to serving America’s educators and their families. It trades on the NYSE under the ticker HMN and generates roughly $1.6 billion in annual revenue. But the real differentiator isn’t the ticker or the top line. It’s the choice the company has kept making for eight decades: focus, and keep focusing.

Horace Mann serves about 1 million out of nearly 8 million K–12 teachers, administrators, and support staff in the U.S.—roughly one in eight. That’s meaningful penetration in a profession most insurers treat as just another line in a spreadsheet.

Which brings us to the question at the heart of this story: how does a company survive—let alone thrive—for 80 years by deliberately limiting its market to a single profession? In an industry where scale seems to reward the biggest generalists, where GEICO and Progressive spend billions to win every driver, Horace Mann made the opposite bet: that going narrower could actually make you stronger.

This is a story about niche domination and distribution moats that take decades to build. It’s also a story about reinvention—about the dramatic transformation that began after Marita Zuraitis became CEO in 2013, as the company faced digital disruption, catastrophic weather, and years of low interest rates, all while serving customers who are essential to society but not known for having high incomes.

And if you’re coming at this as an investor, Horace Mann is a fascinating puzzle. Is it a quiet compounder with a durable edge—trust, relationships, and deep understanding of a single customer base? Or is it a niche player whose focus also caps its growth? The answer says a lot about what “moats” really look like in insurance.

Origins & The Founding Vision (1940s)

Before there was a company with his name on the letterhead, there was Horace Mann himself: a 19th-century Massachusetts politician and education reformer, often called the “Father of American Public Education.” Mann pushed a then-radical idea—that every child, regardless of background, deserved access to a quality education. He never sold an insurance policy in his life. But his name came to stand for a cause, and later, for a company built to serve the people carrying that cause forward.

Horace Mann was founded in Springfield, Illinois, in 1945. At first, it wasn’t called Horace Mann at all. It was the IEA (Illinois Education Association) Mutual Insurance Company, reflecting its affiliation with the Illinois Education Association. And it was created by two teachers: Leslie Nimmo and Carrol Hall.

Their starting point was narrow by design. Nimmo and Hall set up IEA Mutual to sell auto insurance to Illinois teachers. In post-Depression America, most insurers didn’t think of educators as a distinct customer segment worth building around. Teachers weren’t high earners. But they were, in many ways, ideal insurance customers: steady jobs, predictable income, and a professional culture built around responsibility and planning.

Nimmo and Hall’s insight was simple, and it turns out, powerful: educators were underserved, and they tended to be better-than-average risks. Pool enough teachers together and you could offer competitive rates while still running a sound insurance business. Better yet, if distribution ran through the education community—teacher associations, school districts, and the natural word-of-mouth network inside schools—you didn’t need to spend like a consumer giant on mass advertising to find customers.

The company later took the name Horace Mann, a deliberate tribute to the man most associated with the American public education movement. Mann wasn’t involved, of course. But the naming mattered. It signaled that this wasn’t just a company that happened to sell policies to teachers—it was a business that wanted to be part of the education ecosystem. That sense of mission alignment would become one of its most durable advantages.

Growth followed quickly. Within two years, the company was offering auto insurance to teachers beyond Illinois. And by 1949, it expanded into life insurance, extending its relationship from protecting a teacher’s car to protecting their family’s financial security.

That early pattern is the blueprint Horace Mann kept returning to for decades: earn trust with educators first, then expand. Serve one community exceptionally well. Follow that community as it spreads. Then broaden the product set to match real needs over the arc of a career—life insurance, and eventually much more.

It was the opposite of the mainstream insurance playbook. While companies like State Farm and Allstate built massive distribution machines designed to sell to everyone, Horace Mann concentrated on schools, districts, and educator associations—relationships that compound over time, and that competitors can’t simply buy off a billboard.

Building the Educator Moat (1950s-1990s)

The decades after World War II were a once-in-a-century boom for American public education. Baby Boomers packed classrooms. Suburbs built new schools. Districts hired in waves. And for Horace Mann, that meant the customer base it had chosen on purpose was growing right alongside the country.

Then a piece of federal policy opened the door to something even bigger than auto and life insurance. In 1961, Congress created the framework for tax-deferred annuities—what educators would come to know through the 403(b). Horace Mann moved into annuities that same year, and it wasn’t a side business for long. Retirement became central to the company’s identity, because it sat right at the intersection of two things Horace Mann understood deeply: education and planning.

The 403(b)—the nonprofit world’s counterpart to the 401(k)—fit Horace Mann’s strategy almost too perfectly. Teachers didn’t just need a place to save; they needed someone who could speak their language. Retirement for an educator isn’t identical to retirement for a corporate employee. There can be summer income gaps. There’s often a pension in the mix. And many educators plan for a longer stretch after leaving the classroom. Horace Mann positioned itself as the specialist who could navigate those realities, not a generic provider trying to serve everyone.

As the product set expanded, Horace Mann’s real advantage took shape in how it got to the customer. This is where the moat formed: distribution built not on advertising, but on relationships. The company contracted with more than 600 exclusive agencies for sales and service. These weren’t agents trying to be all things to all people. Many were former educators, or had deep ties to local schools. They showed up at teacher appreciation events. They sponsored school functions. They became familiar faces in the community—people you’d talk to in the teachers’ lounge, not a call center voice you’d never meet.

Those relationships compounded through institutions, too. Horace Mann’s retirement products were present in nearly 4,000 districts, supported by more than 105 education association partnerships. Over time, those ties created real switching costs. If a district had set up payroll deduction for premiums or retirement contributions through Horace Mann, changing providers wasn’t just a pricing decision—it was an administrative headache, a disruption of routines, and a break from established trust.

The corporate story evolved alongside the distribution story. In August 1989, Horace Mann was acquired from CIGNA by an investor group that included company management. The management buyout pulled the company out from under a large corporate parent and gave it more freedom to chart its own course.

A couple years later, in November 1991, Horace Mann went public—pricing its initial public offering at $18 per share—and began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker HMN. Public capital, same focused mission. While plenty of companies use an IPO as an excuse to broaden into adjacent markets, Horace Mann largely kept doing what it had always done: serve educators.

In January 1994, the company acquired Allegiance Insurance Company, a California property and casualty insurer that Horace Mann had managed since 1989. It was a practical move—expand geographic reach using an asset it already knew—without abandoning the niche.

By the turn of the millennium, Horace Mann had assembled the core pieces that would define it: exclusive focus on educators, a multi-line product set, and a distribution engine rooted in school communities and association partnerships. The big question heading into the next era wasn’t whether the model worked—it clearly did. The question was whether it could hold up as insurance entered a new age of scale, digital disruption, and intensifying competition.

The Golden Years & Growing Cracks (2000s)

The early 2000s handed Horace Mann a paradox that hits almost every successful specialist sooner or later: focus had built the franchise, but focus also set the ceiling. Educators are a large group, but they’re not infinite—and they’re not a high-income demographic. If Horace Mann wanted to keep growing, it had two main levers: win customers away from other insurers, or deepen relationships with the teachers it already served. Neither one was easy.

So the company started looking for ways to earn more of the “financial household.” In 2003, Horace Mann entered the mutual funds business—an expansion beyond annuities into mainstream investments. The logic was straightforward: if you’re already the trusted name for a teacher’s insurance and retirement planning, why not be the place they invest, too? The problem was that this move dragged Horace Mann onto a battlefield dominated by giants like Fidelity and Vanguard, where scale, brand, and distribution are everything.

Then came 2008. The financial crisis didn’t just rattle consumers—it hit insurers at the core of their business model. Investment portfolios took a beating as markets fell. Variable annuities, in particular, started to look like a trap: products that promised certain outcomes to customers while leaving the insurer exposed when markets moved the wrong way. At the same time, the long era of low interest rates squeezed the basic economics of life insurance, compressing the spread insurers earn between what they invest and what they promise policyholders.

And as the balance sheet pressure built, the world outside was changing just as fast. GEICO and Progressive showed how aggressively direct-to-consumer advertising could pull business away from traditional agent channels. Customers got used to researching and buying insurance online, on their own schedule—not by meeting an agent at a school or scheduling a sit-down. Technology companies began circling insurance distribution, adding a new kind of threat: not just another carrier, but a new way of reaching the customer.

Inside Horace Mann, the distribution engine that had been such an advantage started to show strain. The exclusive agent model required relentless recruiting and training. And a new generation of agents often wanted something different—more flexibility through independent channels, or more stability through direct employment—than the demanding, entrepreneurial path of being exclusive. Retention weakened.

Underneath it all, the plumbing was aging. Legacy systems for policy administration and claims were built for a paper world. They worked, but they didn’t bend easily toward the digital experience customers increasingly expected. Modernizing them meant major investment with a payoff that was real—but not immediate, and not guaranteed.

Investors saw all of this. For much of the 2010s, Horace Mann’s stock traded at a deep discount to book value, a market signal that shareholders weren’t sure the educator-only strategy could keep working—or that the company could modernize fast enough to prove it.

That was the landscape the board faced when it went looking for new leadership. They found their answer in Marita Zuraitis.

The Marita Zuraitis Era: Transformation Begins (2013-2023)

When Marita Zuraitis arrived at Horace Mann, the mandate was clear: protect what made the company special, and fix what was holding it back.

She joined in May 2013 as President and CEO-elect, then officially took the helm in September. At the time, Horace Mann had a strong niche and a loyal distribution network—but it was also carrying the weight of legacy systems, shifting consumer behavior, and the industry’s post-crisis hangover.

Zuraitis brought a résumé built for exactly this kind of job. Before Horace Mann, she ran The Hanover Insurance Group’s property and casualty companies, overseeing both personal and commercial lines. Earlier, she held senior roles at The St. Paul/Travelers Companies, USF&G, and Aetna Life and Casualty. In other words: she’d led from both headquarters and the field, and she knew how insurers actually work when the business gets messy.

But her fit wasn’t just professional. Zuraitis also had a personal connection to Horace Mann’s educator mission through several family members who were teachers. That mattered here. Horace Mann isn’t simply trying to win on price; it’s trying to win on trust. You can’t lead that with spreadsheets alone.

As she put it at the time: “My four-month transition working with Pete has been invaluable and validated my initial assessment of Horace Mann as a financially strong company with dedicated agents and employees focused on serving the educator marketplace. I look forward to building on that foundation and profitably growing the business.”

The word “profitably” is doing real work in that sentence. Zuraitis didn’t come in to chase growth for growth’s sake. She came in to rebuild the machine.

Her transformation agenda touched almost everything.

First: technology. Modernization moved from “someday” to “now.” Horace Mann began investing heavily in new policy administration systems, better digital experiences for customers, and stronger data analytics. These were not quick wins. They were expensive, multi-year projects—exactly the kind that are easy to postpone until it’s too late. But they were necessary if Horace Mann wanted to keep its relationship-driven model while meeting modern expectations.

Then: distribution. This was the delicate part, because the exclusive agent force was both Horace Mann’s identity and its moat. The answer wasn’t to rip it out and go fully direct. Instead, Zuraitis focused on upgrading it. Agents got better tools—digital quoting, CRM, and marketing automation—while the company also built out direct options for educators who preferred self-service. The goal wasn’t to replace relationships. It was to make them work in a digital world.

Next: the product portfolio. Here, the company made some harder calls. Variable annuities, with their capital-intensive guarantees and ugly downside when markets turn, became less central as Horace Mann leaned toward products with more predictable risk.

And finally: capital allocation. Discipline became a theme. The company bought back shares when the stock traded below what management believed it was worth, and it raised the dividend again—its 17th consecutive year of dividend increases—signaling confidence in the cash the business could generate.

The payoff didn’t show up overnight. Then, almost quietly, it did. Operating metrics started moving in the right direction: combined ratios improved, expense ratios came down, and return on equity began climbing toward the double-digit levels that had long felt out of reach.

Key Inflection Point: The COVID Pandemic & Digital Acceleration (2020-2021)

In March 2020, COVID-19 shut down schools across America almost overnight. For Horace Mann, it wasn’t just a public-health crisis—it was a stress test of the entire premise of the company. Its customers were teachers and school employees, and suddenly their lives were upended: classrooms went virtual, stress spiked, and district budgets tightened under enormous uncertainty.

Horace Mann’s first priority was keeping people safe while keeping the business running. The company quickly moved more than 95% of its workforce to remote work without reducing service levels—something that would have been hard to imagine in an earlier era of paper files and on-prem systems. The technology investments Zuraitis had been pushing finally had their “this is why we did it” moment, and the payoff showed up in days, not quarters.

Then the company did something that fit its brand in a way a generic carrier couldn’t easily imitate. Horace Mann announced a Teacher Appreciation Relief Program, crediting customers with 15% of two months of auto premiums—subject to regulatory approval—because driving had dropped so sharply during the pandemic.

That relief wasn’t a one-off gesture, either. Horace Mann also offered other forms of financial flexibility, including coverage continuity and a grace period for payments due through June 30 on auto, property, supplemental, and life insurance coverages.

As Zuraitis put it: “Our mission is to help our customers protect what they have today and prepare for a successful tomorrow. Appreciating the work that educators do has always been a part of who we are, and this is our way of letting them know that we are here for them.”

The pandemic also pulled digital adoption forward by years. With educators working from home, Horace Mann leaned into proactive outreach—and discovered something surprising: teachers were actually easier to reach. As the company noted at the time, agents were making more outbound calls and seeing higher response rates, simply because educators had more flexibility to take them.

And the tone was clear: the company wasn’t treating this like a normal marketing opportunity. “What we’re asking of teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic is monumental,” Zuraitis said. “In addition to the personal challenges we are all facing, teachers are balancing the needs of students and their families, their own health concerns, and adjusting their teaching to be as effective as possible in physically distant or remote learning environments.”

Horace Mann also published research to put numbers behind what educators were feeling. The report found that most educators were working more than a year earlier, nearly two-thirds were enjoying their jobs less, and more than half didn’t feel secure in their district’s health and safety precautions.

Financially, COVID delivered the kind of mixed bag you’d expect for an insurer. Fewer cars on the road meant fewer auto claims, which helped loss ratios. But the broader economic shock and low interest rates created headwinds for the investment portfolio, and the sheer uncertainty made strategic planning harder than ever.

The Recent Revolution: AI, Data, and the New Competitive Landscape (2022-Present)

By 2022, the big question for Horace Mann wasn’t whether it could survive disruption. It was whether all the hard, unglamorous work of the prior decade—tech modernization, tightening underwriting, de-risking parts of the portfolio—could finally translate into a cleaner growth story. The next few years delivered the clearest “yes” the company had put on the scoreboard in a long time.

The most important strategic move came right out of the gate. In January 2022, Horace Mann announced it had completed the acquisition of Madison National Life Insurance Company, Inc., a provider of group life, disability, and specialty health insurance for educators and public sector employees.

Horace Mann acquired Madison National for $172.5 million. Headquartered in Madison, Wisconsin, Madison National offered short- and long-term group disability, group life, and other products, with K-12 school districts representing 80% of 2020 premiums.

This wasn’t just “add another line of business.” It was a shift in where Horace Mann could win. Historically, the company’s center of gravity had been individual educators—sold one relationship at a time through its agent force. Madison National pulled Horace Mann deeper into the district level, where benefits decisions get made in bulk and where, amid a teacher shortage, districts were increasingly looking for better protection products to help with recruitment and retention.

As CEO Marita Zuraitis put it: “Bringing Horace Mann and Madison National Life together greatly expands our ability to serve educators. In addition to our historical strength in the individual educator space, we can now provide employer-sponsored protection products that school districts are increasingly looking to offer to boost educator recruitment and retention.”

You can see the strategic intent in the reporting structure. Beginning in the first quarter of 2022, Horace Mann started reporting financial results in two divisions: Individual Insurance & Financial Services (Property & Casualty and Life & Retirement), and Supplemental & Group Benefits (the Supplemental business plus Madison National Life combined in one segment). In other words: the company wanted investors to track the “educators one-by-one” business separately from the “districts as employers” business.

While that was happening on the product and distribution side, Horace Mann kept pushing on the operational side. In early 2025, the company unveiled Catalyst, a technology platform designed to simplify workflows, improve customer interactions, and strengthen the agent-client relationship. The features—predictive analytics, document integration, and streamlined marketing capabilities—were aimed at a very specific goal: make the agent model feel less like a relic, and more like a modern, high-touch advantage.

“Catalyst has transformed the way I approach my work,” said Bobby Maksymowski, owner of the Maksymowski Agency and head of the National Agent Advisory Council at Horace Mann. “With its use of AI and marketing automation, I can focus on building meaningful relationships with educators and addressing their unique financial needs. It’s truly a game-changer.”

Then came the part Wall Street cares about most: did it work?

Horace Mann’s 2024 results were the clearest evidence yet that the turnaround had moved from “plan” to “performance.” For the full year, the company reported net income of $103 million, or $2.48 per share, and core earnings of $132 million, or $3.18 per share. At year-end, reported book value was $31.51, with adjusted book value of $37.54.

Revenue came in at $1.60 billion, up 6.9% from 2023. Net income rose 128% from the prior year.

But the heart of the story was underwriting. The combined ratio improved to 97.9%, down from 111.7% in 2023. That’s the difference between an insurance engine that’s leaking money and one that’s back to doing what it’s supposed to do: price risk correctly, pay claims, and still generate profit. The company attributed the improvement to disciplined rate increases, improved underwriting, and favorable weather patterns.

“In 2024, we delivered strong earnings results by restoring Property & Casualty segment profitability while positioning the company for sustained, profitable household growth,” Zuraitis said. “In 2025, by maintaining business profitability and executing on our growth plans, we expect core EPS in the range of $3.60 to $3.90 per share and a double-digit shareholder return on equity.”

Early 2025 suggested the momentum carried into the next year. In its May 6, 2025 investor presentation, Horace Mann reported record first-quarter core earnings per share of $1.07 and pointed to continued improvement, especially in Property & Casualty.

Core return on equity improved to 10.6%, up 4.9 percentage points year over year.

Property & Casualty showed the sharpest change, with a combined ratio of 89.4%, improving 10.5 percentage points from the prior year. Within that, the Property combined ratio was 79.9% and Auto was 95.0%.

The Educator Ecosystem: Why This Niche Still Works

To understand Horace Mann’s edge, you first have to understand the market it’s chosen to live in for eight decades: the educator ecosystem. On paper, it looks narrow. In practice, it’s deep.

Horace Mann serves about 1 million of the nation’s nearly 8 million K–12 teachers, administrators, and support staff. That means the company has meaningful penetration—and still a lot of white space—without ever needing to leave its lane.

The reason educators work so well as insurance customers isn’t one magic trait. It’s a stack of advantages that reinforce each other. Teaching is stable work in an essential profession, and it stayed structurally intact even through COVID-era disruption. Educators tend to be highly educated, which often correlates with lower claims frequency. Their pay may not be lavish, but it’s steady and predictable. And culturally, this is a profession built around responsibility, planning, and showing up day after day—exactly the behavioral profile an insurer wants.

Horace Mann then matches that customer profile with a product set built around educator reality. It focuses on K–12 educators, administrators, and public-school employees, and it reaches them through a network that includes agents, brokers, and benefit specialists.

But the real muscle is distribution. Horace Mann didn’t wake up with relationships across thousands of school districts and education associations. It built them, one district and one partnership at a time, until they became difficult to dislodge. That web of trust—spanning more than 4,000 school districts, 105-plus education associations, and hundreds of agent offices—isn’t something a competitor can replicate quickly, even with a big checkbook. In this niche, time is a barrier to entry.

Under the hood, the company also points to strong risk-adjusted capitalization, as measured by Best’s Capital Adequacy Ratio—supported by conservative reserving practices and limited reliance on reinsurance. In an industry where surprises can sink you, that kind of balance-sheet posture matters.

Then there’s the quiet compounding advantage: data. With roughly 80 years of claims experience concentrated in one profession, Horace Mann has educator-specific actuarial history that generalist carriers can’t easily match. That helps the company price and underwrite with more precision—often the difference between an insurance book that muddles through and one that consistently earns its keep.

Specialization shows up in the small details, too. The Educator Advantage package includes coverages designed for teachers—for example, up to $1,000 in personal property coverage if items you use for work are stolen or damaged while in your car. These aren’t headline-grabbing features, but they signal, unmistakably: this was built for you. And that’s hard for a generalist insurer to fake convincingly.

The long arc of the relationship matters most in retirement. Horace Mann has been helping educators plan since 1961, the year the 403(b) was established. Once an educator builds meaningful assets in a Horace Mann 403(b), the relationship is no longer a simple annual shopping decision. The friction of moving assets, the habit of ongoing contributions, and years of interaction with an agent or representative create real switching costs—and a customer bond that tends to hold.

Strategic Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

To really understand Horace Mann’s competitive position, it helps to step back from the story and run the company through two classic strategy lenses: Michael Porter’s Five Forces, and Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers. Different frameworks, same goal—figure out what keeps competitors at bay, and what could still knock the business off course.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-LOW

Insurance isn’t a business you casually “try.” It’s one of the most heavily regulated industries in the country, and licensing happens state by state. Building a true multi-state insurer takes real time, capital, and an enormous compliance muscle.

Then there’s the part you can’t buy quickly: distribution. Horace Mann contracts with more than 600 exclusive agencies for sales and service, and those agency and institutional relationships have been built over decades. That’s a moat measured in years, not marketing spend. The caveat is the modern one: InsurTechs have proven that, in some cases, technology can route around traditional distribution. That doesn’t erase Horace Mann’s advantage—but it does keep the pressure on.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Horace Mann’s key “suppliers” are reinsurers and technology vendors. Reinsurance is a competitive market, and there’s generally plenty of capacity. On the tech side, as cloud platforms have matured, a lot of the underlying infrastructure has become more standardized and easier to source.

And while agents are absolutely critical to Horace Mann, they aren’t really a supplier in the traditional sense—they’re a proprietary distribution asset the company has built and controls.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

Educators tend to be budget-conscious, and insurance is increasingly easy to shop. Online quoting and price transparency push buyer power up.

But Horace Mann isn’t selling a single isolated policy. Bundling creates real inertia, and retirement accounts add even more friction. On top of that is something that doesn’t show up neatly in a spreadsheet: trust. For many educators, the appeal isn’t just price. It’s the feeling that the company actually understands their world.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

For many teachers, the substitute isn’t “another insurer,” it’s “a different way of solving the problem.” Direct-to-consumer carriers like GEICO and Lemonade give price-sensitive customers an easy alternative. In retirement, robo-advisors can replace a human-led planning relationship. And when budgets get tight, some households respond by raising deductibles, reducing coverage, or opting out of certain products altogether.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Insurance is crowded. Dozens of carriers fight over commoditized lines like auto, and that competition often turns into price wars.

Horace Mann’s specialization doesn’t make rivalry disappear—it just changes the battlefield. Instead of trying to outspend everyone for the average consumer, Horace Mann competes to be the default choice inside a specific community.

Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers Analysis:

1. Cornered Resource: Horace Mann’s educator customer base and roughly 80 years of educator-specific actuarial data are assets competitors can’t realistically recreate. That history compounds into better pricing, better underwriting, and better risk selection inside the niche.

2. Network Economies: Limited. This isn’t a classic network effects business where each additional customer makes the product better for every other customer.

3. Counter-Positioning: STRONG. Horace Mann’s “educators only” strategy is difficult for generalist insurers to copy without stepping on their own toes. A mass-market carrier can’t easily launch an educator-only brand without creating channel conflict and muddling their positioning.

4. Scale Economies: Moderate. Scale matters in insurance, especially with state-by-state compliance and operational overhead. But Horace Mann’s deliberate focus also limits how big it can get compared to the mega-carriers.

5. Switching Costs: STRONG, especially for bundled households and retirement relationships. If an educator has auto, home, and life coverage tied together—plus a 403(b), maybe with payroll deduction—moving isn’t a quick click. It’s paperwork, disruption, and risk.

6. Branding: Strong within education, almost invisible outside it. That’s the trade-off: narrow reach, deep resonance. Among educators who know the company, the mission alignment and educator-specific features often create genuine affinity.

7. Process Power: Developing. Horace Mann’s advantage here is institutional: how it trains agents, how it underwrites educators, and how it operates with cultural fluency inside schools and districts. Those processes aren’t impossible to copy, but they’re hard to reproduce quickly and consistently.

Strongest Powers: Counter-Positioning, Switching Costs, Cornered Resource

Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Horace Mann’s eight-decade run isn’t just a feel-good story about serving teachers. It’s a pretty sharp case study in how to build an enduring business in an industry where most products look the same and competition never sleeps.

The Power of Niche Domination: Sometimes narrower is better. The default belief in insurance is that bigger always wins—more customers, more data, more leverage. Horace Mann shows the counterpoint: a specialist can beat a generalist when the niche is both large enough to matter and specific enough to truly understand. “Educators” is exactly that: not a tiny sliver, but not a generic mass market either.

Distribution Still Matters: Even in a world of online quoting and instant comparisons, trust is still a moat. Horace Mann’s agent network was built the slow way—through school visits, teacher appreciation events, and showing up locally year after year. That kind of presence isn’t easily replicated by a well-funded startup with a sleek app. And for products like life insurance and annuities, many customers still want a person, not just a price.

Transformation While Running: Marita Zuraitis’s era is a reminder that turnarounds in legacy businesses are less like flipping a switch and more like replacing the engine while the plane is in the air. Horace Mann modernized technology, improved digital tools for agents, and reshaped parts of the product portfolio without ripping out the core relationship model that made the company different in the first place.

Mission as Competitive Advantage: In many industries, “mission” is marketing. Here, it’s part of the operating system. Horace Mann’s educator focus creates real cultural alignment—with customers and with the agents serving them. People tend to work differently when they believe they’re serving a community, not just closing a sale.

The Patience Game: Insurance punishes impatience. Customer relationships last decades. Some products, like variable annuities, come with long tails and long commitments. And even straightforward fixes—like rate increases—often take a year or more to show up clearly in results. It’s a business where quarterly thinking can create long-term damage.

Data Compounds: Horace Mann’s advantage isn’t just that it has data—it’s that it has concentrated, profession-specific data. Decades of educator claims history can translate into sharper pricing and underwriting over time. It’s not flashy, but it’s one of the most durable edges an insurer can have.

Capital Allocation Discipline: In insurance, how you manage capital is strategy, not housekeeping. Horace Mann has balanced investing in modernization with returning capital to shareholders. The company increased its annual dividend by 3% in March 2025, with a current yield of 3.3%. It also continued buying back shares: year-to-date repurchases totaled $7.2 million, and repurchases since the initial authorization in 2011 totaled $130.9 million.

Bull vs. Bear Case & Future Outlook

The Bull Case:

The Zuraitis transformation looks real, not rhetorical. After years of frustration, Horace Mann started putting up the kind of profitability numbers that signal an insurance business is functioning the way it’s supposed to. Core return on equity rose to 10.6%, up 4.9 percentage points year over year—evidence that the cleanup in underwriting, tech, and capital management has been translating into results.

The niche still looks surprisingly durable. Horace Mann serves roughly 12% of the nearly 8 million potential K–12 educator customers, which means the company can keep growing for a long time without ever leaving its lane. And as insurance buying behavior shifts, the digital investments matter: if the company can combine modern tools with its relationship model, it has a shot at winning younger teachers who still want advice—but expect an easier experience.

Management also kept its full-year 2025 guidance in place—$3.60 to $3.90 in earnings per share—with an expectation that every line of business reaches target profitability. In a business where “turnaround” plans often come with asterisks, simply holding the line on guidance is part of the bull story.

Then there’s the teacher shortage. Districts are competing harder for talent, and that competition often shows up in benefits. The Madison National Life acquisition positioned Horace Mann to meet districts where decisions get made—through employer-sponsored protection products, not just one educator at a time through an agent.

Finally, the macro backdrop has been kinder. Rising interest rates from 2022 through 2024 improved investment yields, which helps the economics of life and retirement products.

The Bear Case:

The niche cuts both ways. Teachers generally aren’t high earners, which limits how fast premiums can grow. The market is meaningful, but finite. So growth tends to require either taking share from well-funded competitors—or stepping outside the educator-only strategy, which risks diluting the brand and the distribution advantage that made Horace Mann special in the first place.

Distribution is another pressure point. Agent-based models are expensive compared to direct-to-consumer players. GEICO can pour money into ads without supporting a network of local offices, and that structural cost difference can become pricing pressure—especially in commoditized lines like auto.

Catastrophic weather is the wildcard that can humble any property insurer, and climate-driven losses have been rising. Horace Mann expected second-quarter catastrophe losses of $40 million to $42 million pretax, or about 23 points on the combined ratio. The company also noted that second-quarter catastrophe losses are typically about half of its full-year catastrophe load—meaning a bad quarter can distort the year, and a bad year can distort the narrative.

There’s also platform risk. If a tech giant like Amazon, Apple, or Google ever pushed aggressively into insurance and broader financial services, it would bring a level of user experience and distribution reach that Horace Mann simply can’t match in dollars.

And as a small-cap company, Horace Mann has a practical constraint: liquidity. With a market cap of about $1.82 billion, some institutions can’t build meaningful positions even if they like the story.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch:

For investors following Horace Mann, two metrics deserve the most attention:

-

Property & Casualty Combined Ratio: This is the scoreboard for underwriting. Horace Mann targets a mid-90s combined ratio for sustainable profitability. For the full year, it reported a combined ratio of 98%, about a 15-point improvement from the prior year. If the company can keep this metric near—ideally below—that level, it’s a strong sign the turnaround is holding.

-

Core Return on Equity: This is the test of whether the company is earning enough on shareholder capital to justify its valuation. Core ROE improved to 10.6%. If Horace Mann can sustain double-digit returns, it strengthens the investment case and supports a higher-quality multiple over time.

Epilogue: The Next Chapter

Horace Mann announced it will host an Investor Day in New York City on Tuesday, May 13, 2025, from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. ET. The event will feature presentations from the executive leadership team, offering a closer look at the company’s strategic initiatives and its vision for the future.

Around the same time, Horace Mann wrapped a customer campaign marking its 80th anniversary and rolled straight into Teacher Appreciation Month in May—another reminder that, even as it modernizes, it’s still trying to feel like part of the community it serves.

Eight decades after Leslie Nimmo and Carrol Hall decided teachers deserved an insurance company built for them, Horace Mann stood at a familiar kind of crossroads. The Zuraitis-era turnaround had repaired profitability and steadied the business. Now the next question was how to keep evolving without sanding down the very edge that made the company different. Investments like Catalyst were meant to do exactly that: modernize how work gets done, give agents better tools, and keep the relationship model from becoming a disadvantage in a world that expects everything to be fast and digital.

The generational question hangs over all of it: will Gen Z teachers want a person they trust, or an app that never sleeps? The likely answer is both. Horace Mann’s bet is that the winning model isn’t purely digital or purely human—it’s a hybrid that gives educators convenience for simple transactions and real guidance when decisions get complicated.

There are also expansion paths beyond the core K–12 educator market. Healthcare workers, nonprofit employees, and municipal employees share some of the same traits that made teachers attractive customers in the first place: stable employment, mission-driven work, and moderate incomes. Whether Horace Mann pursues those adjacent niches or keeps going deeper into education is one of the most consequential strategic choices in front of it.

What the company does have, by its own description, is a position of strength: a high-quality investment portfolio built for consistency across economic environments, and a suite of products tailored to a customer base that tends to have more job security than many other occupations in downturns.

The bigger lesson from Horace Mann’s story stretches beyond insurance. In an era where scale feels like the only cheat code, there are still businesses that win by doing the opposite—by narrowing the audience, learning it intimately, and earning trust over decades. In those corners of the economy, specialization beats generalization, and patience outperforms hype.

Sometimes the best business strategy is knowing exactly who you serve and never wavering.

Further Reading & Resources

Top References:

- Company History & SEC Filings: Horace Mann’s investor relations site (investors.horacemann.com) includes annual reports, quarterly filings, and investor presentations

- Insurance Industry Analysis: A.M. Best ratings and industry reports for broader context on insurer balance sheets, profitability, and competitive dynamics

- Hamilton's 7 Powers: "7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy" by Hamilton Helmer, the framework for sustainable competitive advantage

- Porter's 5 Forces: "Competitive Strategy" by Michael E. Porter, the classic guide to industry structure and competitive rivalry

- Educator Market Demographics: National Education Association reports on teacher pay, employment, and demographic trends

- Insurance Transformation: McKinsey and BCG research on how insurers modernize technology, operations, and distribution

- Niche Strategy: "The 1-Page Marketing Plan" by Allan Dib, a practical take on niche domination

- Capital Allocation: "The Outsiders" by William Thorndike, on how exceptional CEOs deploy capital

- Risk & Insurance History: "Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk" by Peter L. Bernstein, for the long arc behind modern insurance

- Blue Ocean Strategy: W. Chan Kim’s work on creating differentiated markets instead of fighting head-to-head

Note: This analysis reflects publicly available information as of December 27, 2025. Insurance company financial performance can shift quickly based on investment returns, claims experience, and regulatory changes. Do your own due diligence and consult qualified financial advisors before making investment decisions.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music