Harmonic Inc.: The Story of Silicon Photonics and the Video Infrastructure Revolution

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

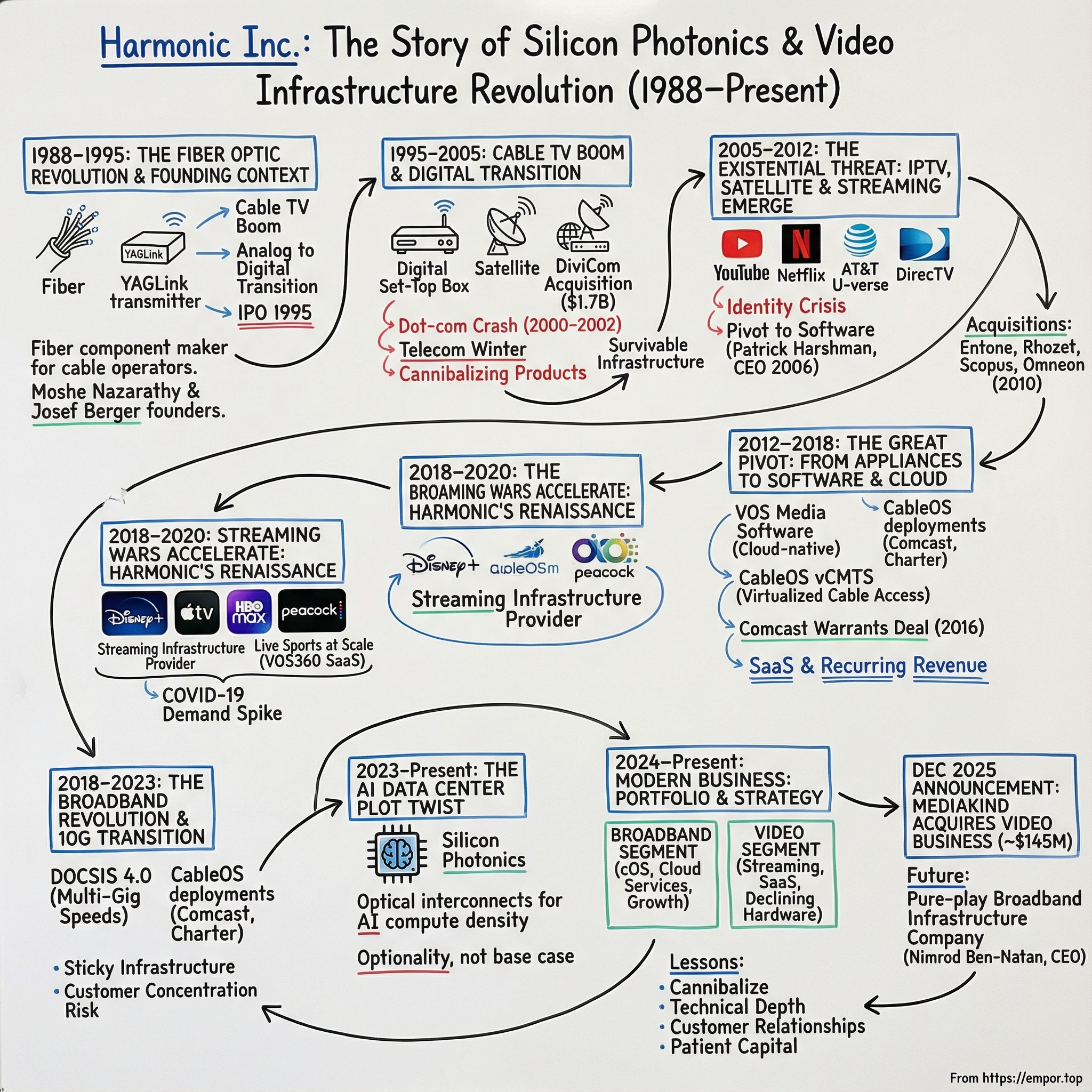

Picture the invisible backbone of modern entertainment and connectivity: the infrastructure that lets you stream the Super Bowl on your phone, binge Netflix in 4K, or pull down huge files in seconds over a cable modem. Behind all of that sits a company most people have never heard of, but one that has quietly shaped how video and broadband work for nearly four decades: Harmonic Inc.

Harmonic was incorporated in 1988 and is headquartered in San Jose, California. It started as a fiber optic equipment maker selling into cable TV operators, then survived wave after wave of industry whiplash—near-death stretches, platform transitions, and strategic pivots that would have broken most tech companies. In its modern form, Harmonic operates through Broadband and Video segments. The Broadband segment centers on software-based broadband access for operators, including cOS software-based solutions and cOS central cloud services offered by subscription.

So here’s the question that frames everything: how did a fiber optic component maker survive multiple platform shifts—and come out the other side as critical infrastructure for the streaming era and, increasingly, what comes next? The answer is a playbook in timing, resilience, and why infrastructure businesses—done right—can outlast the flashier parts of tech.

And the story is especially charged right now because of what Harmonic announced in December 2025. The company received a binding offer from MediaKind, a global leader in cloud-based video streaming technology, to acquire Harmonic’s Video Business segment for approximately $145 million in cash. The deal is expected to close in the first half of 2026, subject to a French employee works council consultation process and customary closing conditions. In other words: after years of building two businesses in parallel, Harmonic is preparing to sell one of them—and become a pure-play broadband infrastructure company, placing its bet on cable’s march toward multi-gig speeds.

That sets up the themes we’ll keep coming back to: platform transitions, the uncomfortable necessity of cannibalizing your own products, and the underrated power of customer relationships when you sell mission-critical infrastructure. This isn’t a unicorn fairy tale. It’s the long, grinding, unglamorous work of building the plumbing—and surviving long enough to become essential.

II. The Fiber Optic Revolution & Founding Context (1988–1995)

By the mid-1980s, cable TV had a very real physics problem: bandwidth. The analog networks that delivered HBO, ESPN, and the local stations into American living rooms were running into the limits of coax. The farther a signal traveled, the more it degraded. And every new channel operators tried to cram into the lineup made the whole system harder to maintain without sacrificing picture quality.

What the industry needed wasn’t a clever marketing bundle. It needed a new medium.

That new medium was fiber optics: thin strands of glass that could carry signals as pulses of light over long distances with far less loss than copper. And in 1988, in Sunnyvale, California, a new company formed around that idea: Harmonic Lightwaves, Inc.

One of the founders was Moshe Nazarathy, who would go on to become the company’s vice president of research and later senior vice president and general manager of Harmonic’s Israel R&D Center. Before Harmonic, he served as a principal scientist at Hewlett-Packard’s Photonics and Instruments Laboratory. In other words, this wasn’t a “let’s try cable” startup. It was built by people who lived and breathed the underlying physics.

Harmonic was incorporated in California in June 1988, and later reincorporated in Delaware in May 1995. In November 1988, Anthony J. Ley became chief executive following the company’s creation by co-founders Moshe Nazarathy and Josef Berger.

Ley brought a very different kind of credibility: deep operational experience. He had spent 25 years at Schlumberger Ltd. in Europe and the U.S. Schlumberger, a multibillion-dollar oil exploration and industrial aviation corporation based in England, had owned Fairchild Semiconductor Corp. from 1983 to 1985; during that stretch, Ley was vice president of research and engineering at Fairchild’s Palo Alto location. Born in London, he held advanced mechanical engineering degrees from Cambridge University and MIT. After becoming a consultant in 1985, he joined Harmonic Lightwaves in 1988—first as a consultant, then as president and CEO.

When Ley arrived, Harmonic was working on fiber-optic measurement projects. But the bigger pull was obvious: cable television was on the verge of a rebuild, and fiber was the tool that made it possible. The core concept was simple to explain and hard to execute—move video from satellites and studios into cable systems, but do it with fiber optic transmission instead of relying purely on coax.

Harmonic’s first product arrived in 1992: the high-power YAGLink transmitter. At launch, it was the industry’s highest powered laser transmitter for broadband video services. And it mattered because it helped cable operators consolidate headends—the facilities where content comes in, gets processed, and then gets distributed across the network. If you can centralize that work instead of duplicating it everywhere, you can lower costs and scale faster.

Meanwhile, in 1993, Nazarathy began leading an Israeli research and development center called Harmonic Data, funded in part by the Israel-U.S. Binational Industrial Research and Development Foundation. That Israel R&D operation would become a long-term engine for the company’s technology development.

The timing couldn’t have been better. In the early 1990s, cable operators were flush with cash and hungry to upgrade for what everyone was pitching as the “500-channel” future. Harmonic rode that infrastructure wave straight into the public markets, completing its IPO on the NASDAQ in May 1995 and raising capital to expand. That same year, Ley added the title of chairman of the board.

Harmonic’s 1995 IPO is a clean example of how infrastructure companies get built: not by inventing demand, but by showing up at the exact moment an industry shifts architectures—here, from copper to fiber—and being ready with the right gear when the spending floodgates open.

III. The Cable TV Boom & Digital Transition (1995–2005)

If the early ’90s were about getting video onto fiber, the late ’90s were about cramming more of that video—at higher quality—into the same pipe. Cable operators were racing to convert analog systems into digital platforms that could deliver hundreds of channels, interactive program guides, and, eventually, high-definition. Harmonic put itself right in the middle of that upgrade cycle.

By this point, Harmonic Inc. (no longer just Harmonic Lightwaves) was selling the kind of infrastructure boxes that made modern cable possible. Its products helped satellite, wireless, fiber, and cable television providers deliver interactive services, and the company organized itself into two divisions: Broadband Access Networks and Convergent Systems.

Competition, though, was brutal. Harmonic was up against vertically integrated giants like Motorola, Cisco Systems, and others, plus a fast-moving pack of specialists that included Envivio, RGB Networks (now Imagine Communications), Elemental Technologies, Appear TV, and ATEME. Harmonic’s advantage wasn’t that it had the biggest catalog—it was that it had the engineering depth and customer relationships to keep winning crucial slots in the video chain.

Then came the dot-com era: a strange mix of real demand and overheated expectations. In 1999 and 2000, infrastructure spending across telecom and cable hit a fever pitch as everyone tried to build ahead of the curve. Harmonic used that moment to make the biggest—and most controversial—move in its history.

In 2000, Harmonic acquired the DiviCom business of C-Cube Microsystems for about $1.7 billion in stock. It was a massive bet for a company of Harmonic’s size. In May 2000, Harmonic completed the acquisition of DiviCom, then a leading provider of standards-based digital video, audio, and data systems for satellite, wireless, fiber, and cable companies. DiviCom’s technology helped customers deliver digital services across multiple network types, and the deal gave Harmonic a much deeper push into satellite, wireless, telecommunications, and other emerging broadband markets.

On paper, the logic was compelling: marry Harmonic’s fiber transmission strengths with DiviCom’s digital video encoding to offer a more complete end-to-end platform for the digital transition. As C-Cube CEO Alexandre Balkanski put it at the time, the deal would “create a powerful infrastructure company” for delivering video, voice, and data across cable, satellite, and terrestrial markets, powered by DiviCom’s MPEG encoder expertise and C-Cube’s semiconductor technology.

In reality, the timing was brutal.

On June 26, 2000—barely weeks after the deal closed—Harmonic warned that its second-quarter results would come in below expectations. The next day, its stock dropped sharply. And as the broader telecom crash unfolded after the dot-com bubble, Harmonic’s customers pulled back spending and the company’s stock price suffered right along with them.

From the DiviCom acquisition through the end of 2005, Harmonic ran as two operating divisions: Convergent Systems for digital video systems, and Broadband Access Networks for fiber optic systems, each with its own management team directing product development and marketing strategy.

Harmonic made it through the 2000–2002 telecom winter by doing the unglamorous work: cutting costs, leaning on loyal customers, and continuing to sell products that, even in a downturn, were still hard to rip out and replace. Cable operators could slow their spending, but they couldn’t stop the digital transition forever.

The takeaway from this era is a tough one for anyone who loves acquisition stories: you can buy the right asset for the right strategic reason and still destroy enormous value if you do it at the wrong moment. Harmonic paid peak-cycle prices for DiviCom—and then spent years living with the hangover.

IV. The Existential Threat: IPTV, Satellite & Streaming Emerge (2005–2012)

By the mid-2000s, cable was no longer the default answer to “How does video get into the home?” And for Harmonic—still deeply tied to cable operators’ capital spending—that wasn’t just a market shift. It was an identity crisis.

The disruption didn’t arrive in a single clean wave. It hit from every direction at once.

First came the telcos. AT&T U-verse and Verizon FiOS pushed into pay TV using IPTV delivered over fiber networks, built around a different architecture than traditional cable headends. Then satellite kept gaining share. DirecTV and Dish could blanket the country, price aggressively, and pull customers away without needing to rebuild local infrastructure market by market.

And then, quietly at first, the open internet started doing what the open internet always does: it collapsed distribution costs and rewrote consumer habits. YouTube launched in 2005 and gave the world an early preview of internet-scale video distribution. Netflix began streaming in 2007—initially more novelty than threat, until it wasn’t. Suddenly, the most dangerous question hanging over Harmonic was also the simplest: if the world moves to over-the-top streaming, what happens to a company built to sell boxes into cable headends?

The financial consequences followed the fear. As operators hesitated and spending slowed, Harmonic’s revenue came under pressure. Investors didn’t wait around to see how the story ended. The stock price fell hard, reflecting real anxiety that the company’s core market might be shrinking permanently.

Inside Harmonic, the strategic problem sharpened into a painful choice: pivot to IP video and internet delivery, or defend the cable infrastructure franchise and hope the storm passed. Either path carried risk. Doing both—keeping the legacy business alive while building the next one—was the hardest option. It was also the only one that gave Harmonic a chance to survive.

That’s the backdrop for a leadership handoff that would define the next decade. In 2006, the board appointed Dr. Patrick Harshman as president and CEO, succeeding Anthony Ley, who had led Harmonic for 18 years. The company framed it as the outcome of an ongoing succession planning process and an external search, but the timing made the subtext clear: Harmonic needed a CEO for a platform transition, not just an upgrade cycle.

Harshman wasn’t an outsider brought in to “shake things up.” He had joined Harmonic in 1993 and rotated through the parts of the business that mattered—marketing, international sales, and R&D. By December 2005, he was executive vice president overseeing most operational functions. Before Harmonic consolidated its product divisions, he had run both sides of the house: Convergent Systems and Broadband Access Networks. He also had the technical pedigree—Ph.D. in electrical engineering from UC Berkeley, plus an executive program at Stanford—to credibly lead an engineering-heavy organization through a technology reset.

Harshman’s core insight was subtle but crucial. The distribution pipes were changing—cable, fiber, IPTV, internet—but the hard problems Harmonic solved weren’t going away. Video still had to be compressed, processed, packaged, and delivered reliably at scale. If Harmonic could follow those problems upstream and abstract itself away from specialized hardware, it could stay relevant no matter who “won” the last mile.

So the direction of travel became clear: less hardware-defined, more software-defined.

Harmonic started buying pieces it needed for that transition. In 2006, it acquired the video networking software business of Entone Technologies for about $45 million. In 2007, it acquired Rhozet Corporation. In 2009, it bought Scopus Video Networks for $5.62 per share in cash, representing an enterprise value of approximately $50 million.

Then came the deal that most clearly signaled where Harshman wanted to take the company. In May 2010, Omneon announced it had agreed to be acquired by Harmonic for an estimated $274 million. Omneon Video Networks, founded in 1998 and backed by firms including Advanced Technology Ventures, Norwest Venture Partners, Accel Partners, and Invesco, had built a reputation in the broadcast world. Its co-founder, Donald M. Craig, had designed products that won Technology & Engineering Emmy Awards in 1988 and 1996. Harmonic wasn’t just buying a product line; it was buying credibility and capability in the workflow layers closer to where video gets created and managed—exactly the territory you want to own if distribution is about to fragment.

And yet, the more interesting question from this era isn’t “What did Harmonic buy?” It’s “How did Harmonic not die?”

The answer is the unsexy superpower of infrastructure: stickiness. Cable operators had already sunk enormous capital into Harmonic’s equipment. Swapping it out wasn’t like changing software vendors. It meant ripping and replacing gear, re-integrating systems, retraining teams, and risking outages in a business where outages are career-limiting. The complexity of video processing and delivery created real switching costs, and those switching costs bought Harmonic time—time to keep the legacy business running while it tried to build the next version of itself.

For anyone who studies infrastructure companies, 2005 to 2012 is the whole paradox in one chapter. Platform transitions are existential threats because they can strand your products overnight. But deep integration and long-lived customer relationships can also be the life raft—if leadership uses the breathing room to actually pivot, not just wait for the old world to come back.

V. The Great Pivot: From Appliances to Software & Cloud (2012–2018)

The Software Transformation

By 2012, Harmonic was done waiting to see whether cable would “stabilize.” Management had reached the uncomfortable conclusion that the next generation of video infrastructure wouldn’t be built out of purpose-built appliances at all. It would be built in software.

That sounds obvious now. Back then, it was an act of self-disruption. Harmonic’s best business was still selling specialized boxes into headends. Betting on software meant asking customers to buy something with different economics, different deployment patterns, and a different mental model. In other words: cannibalize the thing that still paid the bills in order to have a future.

The technical shift was just as dramatic. Instead of proprietary hardware optimized for a single task, Harmonic began building video processing software designed to run on commodity, off-the-shelf servers. VOS Media Software was built as a cloud-native platform, using containers and microservices orchestrated by Kubernetes. The orchestrator tied those microservices together into an end-to-end workflow—so encoding, packaging, and delivery could behave like software services, not fixed-function gear.

From there, the architecture expanded into hybrid cloud. VOS Cloud moved media processing into public or private cloud infrastructure, aiming to reduce the capital expense of building and operating new headends or data centers and to shorten time-to-market for new broadcast and OTT services. In practice, it meant content and service providers could run their workflows on standard IT hardware, scale capacity as needed, and stop treating every upgrade as a forklift replacement.

None of this was an easy sell. Cable operators were used to CAPEX-heavy buying cycles, and to vendors showing up with new chassis, not software licenses. But the argument for software kept getting stronger: lower total cost of ownership, faster deployments, and flexibility that hardware couldn’t match.

Harmonic backed up the strategy with a willingness to shed legacy pieces of itself. In February 2013, it sold its line of fiber-optic access products to Aurora Networks for $46 million in cash. It was a clear signal that Harmonic was prioritizing where the industry was going, not where it had started.

Then came a deal designed to accelerate the pivot and deepen Harmonic’s compression and encoding bench. On February 29, 2016, Harmonic acquired Thomson Video Networks. The combined company brought together a video-focused global R&D organization of more than 600 engineers, a global service organization of more than 300 professionals, and a channel network of over 300 partners. Thomson Video Networks had reported fiscal 2014 revenue of approximately EUR 71 million.

The price: $75 million in cash, with up to $15 million in post-closing adjustments. Strategically, TVN broadened Harmonic’s portfolio and expanded its reach worldwide. It also brought a customer base with limited overlap—less than half of customers were shared—which created a straightforward cross-sell opportunity across pay-TV and OTT providers.

“We are pleased to announce the closing of the TVN acquisition,” said Patrick Harshman, President and CEO of Harmonic. “By bringing together two powerhouses in the video industry, we further extend our position as the market leader.”

The CableOS Vision

While Harmonic was transforming its video business, it made an even bigger bet—one that was less about video workflows and more about the future of cable broadband.

In 2016 and 2017, Harmonic introduced CableOS, a virtualized cable modem termination system, or vCMTS. In the old model, CMTS platforms were enormous hardware appliances bolted into headends. CableOS tried to turn that into software: run the core CMTS functions on standard servers and enable distributed access architectures that pushed intelligence closer to the edge of the network.

Harmonic positioned itself as a pioneer here, saying CableOS—a virtual CCAP product running on off-the-shelf hardware—was being used to deliver broadband service.

But the market didn’t immediately buy the story. Jefferies analyst George Notter described CableOS as “grinding along” and still stuck in a “show-me” phase. He noted that “the long-term competitiveness of the solution remains the key variable for the business,” and that it was “too soon to definitively call their success here.” Customer progress was real, but “it’s not a given that their efforts will translate into meaningful commercial deployments.”

Harmonic’s answer was to land credibility the hard way: with Comcast. Harmonic had a warrants deal with Comcast Corp., announced in the fall of 2016, tied to certain deployment milestones associated with CableOS. Getting the nation’s largest cable operator onto the early path didn’t just bring potential revenue. It sent a signal to the rest of the industry that this wasn’t a lab experiment.

CableOS also put Harmonic in direct contrast with the incumbents. Cisco, ARRIS (later CommScope), and Casa Systems were still largely selling hardware-centric solutions. Harmonic’s pitch was software-defined flexibility and lower cost—but only if operators were willing to embrace a new architecture, and only if Harmonic could prove it would perform at carrier scale.

This is what enterprise infrastructure transitions actually look like. They don’t flip in a quarter. They drag on for years, with compressed margins, lumpy results, and a constant undercurrent of “prove it.” But by the time 2018 arrived, Harmonic had done the hard part: it had built the products—and started winning the reference customers—that positioned it for the next wave that was about to hit video: the streaming wars.

VI. The Streaming Wars Accelerate: Harmonic's Renaissance (2018–2020)

Becoming the Streaming Infrastructure Provider

From late 2018 into early 2020, the video industry stopped drifting and started sprinting. Disney+, Apple TV+, HBO Max, and Peacock either launched or formally teed up their entries, piling into a fight that already included Netflix, Prime Video, and Hulu. And every one of these services ran into the same non-negotiable reality: you can’t declare a streaming revolution without the machinery to encode, process, and deliver video at broadcast quality to huge audiences, all at once.

Harmonic arrived at that moment with the right scars and the right product strategy. Years of investment in cloud-native video processing finally had a market ready to buy it. As studios and broadcasters pushed into direct-to-consumer models, Harmonic leaned hard into Software as a Service, with offerings like its VOS360 platform for streaming workflows. The business impact wasn’t subtle: SaaS created more predictable, recurring revenue compared with the old rhythm of selling big hardware boxes in lumpy cycles—and it helped change how investors thought about what Harmonic actually was.

Empower your video business to reach new audiences with a single, cloud-based solution. The VOS360 Media SaaS features best-in-class linear streaming capabilities so that operators can stream to any device and expand audience reach globally with an outstanding linear and VOD experience.

The sharper point of differentiation wasn’t just “we’re in the cloud.” It was what Harmonic could do in the cloud. The hyperscalers—AWS Media Services, Google Cloud, and others—could offer broad building blocks. Harmonic, by contrast, made a name by obsessing over the hardest version of the problem: live sports and live events at broadcast quality. Netflix’s classic model is fundamentally file-based—process once, then distribute on demand. Streaming a playoff game to millions of people simultaneously, in real time, with tight latency and no excuses, is a different beast. Harmonic’s background in mission-critical video infrastructure translated cleanly into that world.

You could see it show up in performance. The software-as-a-service (SaaS) portion of the video business grew 26% to $13.2 million, driven by live sports streaming. Harshman said Harmonic’s video SaaS platform powered the “largest live streaming event ever in the US,” an apparent reference to Peacock’s exclusive stream of the January 13 NFL Wild Card game.

Then COVID hit in 2020, and streaming stopped being a nice-to-have and became the default. With people stuck at home, video consumption spiked across platforms. For Harmonic, that was both a demand shock and a validation moment: the bet on software-based, cloud-native infrastructure wasn’t just strategically correct, it was operationally necessary—because software can scale in ways appliance deployments simply can’t when demand gets weird.

VOS360 Media simplifies all stages of playout, media processing and delivery. Running on the public cloud, the end-to-end SaaS solution provides unparalleled agility, resiliency, security and scalability for a superior viewing experience.

Over time, the financial story followed the product story. Video SaaS growth made the path to profitability easier to see as recurring revenue replaced the lumpiness of hardware. Video SaaS revenue grew 15% year-over-year, reaching $15.1 million in Q4 2024 and $14.8 million in Q1 2025.

And as that picture sharpened, the market’s narrative shifted with it. Harmonic slowly stopped being treated like a “legacy cable” vendor whose best days were behind it. Investors started to price it as something else: a picks-and-shovels provider to the streaming boom. The question wasn’t “does Harmonic have a future?” anymore. It became, “how big can this get?”

For long-term investors, this stretch is the reminder that infrastructure turnarounds don’t look like Hollywood comeback arcs. They look like years of grinding product work, slow customer adoption, and a lot of waiting—until the industry snaps into a new architecture, and suddenly the company that quietly prepared is standing in the middle of the spending wave.

VII. The Broadband Revolution & 10G Transition (2018–2023)

Cable's Broadband Pivot

While Harmonic’s video reinvention was finally getting credit, the bigger strategic unlock was happening next door, in broadband. Cable operators were quietly changing their identity—from video companies trying to defend a shrinking bundle into broadband utilities determined to win the connectivity war.

The twist is that cord-cutting didn’t just hurt cable. It also created the demand surge that made cable broadband indispensable. Streaming, video calls, remote work, online gaming—every one of those behaviors pulls on the same thing: bandwidth. And in most markets, cable’s hybrid fiber-coax networks could scale that bandwidth more economically than ripping streets open for fiber-to-the-home.

That’s where DOCSIS comes in. CableLabs—the cable industry’s research consortium—developed DOCSIS 4.0 as the next leap for these hybrid networks. The promise is simple: push cable networks into the multi-gig era with symmetric speeds, higher reliability, better security, and lower latency. The headline capability is substantial—up to 10 Gbps downstream and up to 6 Gbps upstream—enough to support multi-gig symmetrical services over existing hybrid fiber-coax.

And that “existing” part is the point. Cable broadband networks—fiber plus coax—already blanket multiple countries and, in the U.S., reach more than 90% of households. DOCSIS 4.0 lets operators squeeze dramatically more capacity out of infrastructure they’ve already paid for, instead of laying entirely new cable. The economics are compelling: lower upgrade costs, faster rollouts, and a clearer path to future-proofing.

Harmonic’s product for this moment was CableOS: a virtualized platform for broadband access networks. Harmonic said CableOS deployments now cover roughly 10% of the global cable modem footprint, and that it continued to lead the early virtual CMTS market into the first quarter of 2023.

Then the deployments started to scale—and with them, the customer concentration that comes with selling core infrastructure. Comcast became the marquee win. In Q1, Comcast represented 47% of Harmonic’s revenue, and Comcast also began using CableOS for targeted fiber-to-the-premises builds. Charter Communications signed on as well, with a multi-phased network evolution plan calling for vCMTS technology across a large portion of its hybrid fiber-coax footprint—about 85%, according to the plan.

By the end of 2023, Harmonic argued it had turned early momentum into a commanding position. The company cited a 62% market share in Distributed Access Architecture and 98% in virtual CMTS solutions—dominance in categories that sit directly on the critical path of the cable industry’s next decade.

Comcast, in particular, became a strategic partnership, not just an account. Harmonic and Comcast worked together to expand fiber broadband access as Comcast pushed into new markets. In 2024, Comcast expanded its network to more than one million new locations, with more than 1.2 million new locations planned by the end of 2025. Comcast said it was leveraging Harmonic’s cOS virtualized broadband platform and network edge devices as a core part of delivering multi-gig symmetrical broadband.

Charter doubled down, too. After selecting Harmonic in 2023 as its vCMTS partner for a multi-phased hybrid fiber-coax upgrade, Charter signed on for expanded use. Under the announcement, Charter would use Harmonic’s cOS platform across its broadband customer base, along with network and operational tools and an unspecified number of Pebble-2 remote PHY devices equipped with unified DOCSIS 4.0 silicon.

Of course, that kind of success comes with a built-in risk: when you win big in cable, you win big with a small number of buyers. Comcast and Charter—both pressing ahead with hybrid fiber-coax evolution plans—represented about 46% of Harmonic’s revenue in Q1 2024. Harmonic’s results were, by definition, tied to the capex timing and deployment choices of a handful of giant operators.

By Q1 2025, that concentration had eased somewhat: Comcast represented 34% of revenue and Charter 12%. The directional change suggested Harmonic was working to broaden its base without losing the whales.

The prize here isn’t just revenue. It’s stickiness. Once CableOS is deployed, it becomes entangled with how an operator runs its network—planning, provisioning, operations, the edge devices, the upgrade path. That’s not a vendor you swap casually. Harmonic said it ended the quarter with commercial CableOS deployments at 94 operators worldwide, up 22% year-over-year, giving it a meaningful lead over vCMTS competitors like Casa Systems, which was beginning to show initial traction, and CommScope.

And that’s why, for investors, broadband started to look like the steadier engine compared with video. The video business could grow, but it could also churn with platform shifts. Broadband infrastructure—once installed—tends to turn into a long-lived, expanding relationship. In infrastructure terms, that’s the dream: a product that stops being a purchase and starts being part of the network’s permanent architecture.

VIII. The AI Data Center Plot Twist (2023–Present)

Silicon Photonics for AI

The most surprising twist in Harmonic’s story showed up in 2023 and 2024: suddenly, people started talking about Harmonic as if it might matter to AI data centers. That narrative pulled in investor attention and helped drive the stock. But it also needs to be handled carefully, because the leap from “cable infrastructure leader” to “AI interconnect winner” is not automatic.

The underlying problem AI runs into is brutally simple: bandwidth. Training large language models means wiring together enormous GPU clusters and moving staggering amounts of data between them. Traditional electrical interconnects can’t scale forever—not in power, not in density, and not in heat.

That’s where silicon photonics comes in. The idea is to integrate optical components onto silicon chips so data can move as pulses of light. Compared with electrons, photons can carry more data with less energy loss over longer distances. And as the compute gets denser, that efficiency starts to look less like an optimization and more like a requirement.

The power story makes the constraint obvious. Goldman Sachs expects data center power demand to grow around 15% annually, with AI data centers growing much faster from 2023 to 2030. By the end of the decade, data centers are expected to account for roughly 8% of U.S. power consumption, up from about 3% today. If that’s even directionally right, the industry can’t just keep brute-forcing the problem with more copper and more watts. Optical interconnects, enabled by silicon photonics, start to look like the only scalable path.

So where does Harmonic fit?

The connection is real, but it’s also easy to overstate. Harmonic has deep roots in optical transmission, and decades of engineering muscle built in infrastructure markets. There are technological adjacencies between moving video and data over fiber for cable networks and the broader optical networking world.

At the same time, Harmonic is not a pure-play silicon photonics company in the way investors might mean when they bring this up. It isn’t Lightmatter or Ayar Labs. It isn’t Broadcom or Marvell with massive photonics investment behind it. Harmonic’s business today is still dominated by cable broadband infrastructure (CableOS) and video streaming services—while that video segment is in the process of being divested to MediaKind.

That distinction matters because the market has sometimes blurred two different ideas: “Harmonic understands optics” and “Harmonic is positioned to win silicon photonics in AI.” Those are not the same claim.

Meanwhile, the leaders in this space are moving quickly. Lumentum said its R300 OCS was being sampled by multiple hyperscale customers. NVIDIA has talked about integrating silicon photonics directly with its Quantum and Spectrum switch integrated circuits, and has pointed to co-packaged silicon photonics systems delivering materially lower power consumption. The competitive set—Lightmatter, Broadcom, Marvell, Intel, and a stack of specialized startups—has already spent heavily to get here.

And even for them, scaling silicon photonics for AI isn’t “just ship it.” The hurdles are hard and fundamental: energy efficiency, manufacturing and packaging, ecosystem development, and cost optimization.

For Harmonic, a meaningful silicon photonics opportunity would likely require substantial investment and, realistically, partnerships or acquisitions. Management has been relatively measured when discussing this, keeping attention on the nearer-term, executable opportunity in broadband infrastructure.

So the investor takeaway is straightforward: silicon photonics is real optionality, but it shouldn’t be the base-case story. The foundation is still the broadband business—with proven deployments and real customers like Comcast and Charter. If Harmonic ends up capturing AI infrastructure upside, treat that as the call option, not the core thesis.

IX. The Modern Business: Portfolio & Strategy (2024–Present)

The December 2025 announcement that Harmonic planned to sell its Video business to MediaKind reshaped the whole company story. To understand Harmonic now, you have to hold two pictures in your head at once: what it still is today, and what it’s trying to become once that transaction closes.

In 2024, Harmonic generated $678.72 million in revenue, up 11.65% from $607.91 million the prior year. Earnings were $39.22 million, down 53.31%.

Operationally, Harmonic still ran two businesses side by side:

Broadband Segment: The Broadband segment sells software-based broadband access solutions. That includes cOS software-based broadband access solutions for broadband operators, plus cOS central cloud services—a subscription service for cOS customers. In fiscal 2024, this segment generated about $456 million in revenue, roughly two-thirds of Harmonic’s total.

Video Segment: The Video segment sells video processing, production, and playout solutions and services to cable operators and to satellite and telco pay-TV providers, as well as to broadcast and media customers, including streaming media companies.

The deal with MediaKind would turn that two-engine company into a pure-play broadband infrastructure business. Harmonic positioned the transaction as an accelerator: by shedding Video, it could concentrate capital, management attention, and product velocity on its virtualized Broadband platform.

MediaKind, for its part, would be buying a Video unit with two very different trajectories under one roof: a declining hardware business alongside a rapidly growing SaaS business. In Q3 2025, Video represented 36.5% of Harmonic’s business.

Why do this now? Harmonic’s argument was straightforward: broadband offered a better long-term setup—more durable demand, deeper strategic importance to customers, and stronger positioning—than the Video segment.

By Q1 2025, Harmonic said its broadband platform was deployed with 129 customers, serving 33.9 million cable modems, a 30% increase from the prior year. The company also said it had added seven new broadband customers, including two U.S. Tier 1 operators and three fiber customers.

Harmonic continued to emphasize innovation across video and broadband, and reported trailing twelve months revenue of $635.71 million in 2025. In the third quarter of 2025, Harmonic reported Non-GAAP Net Income of $14.1 million and a Non-GAAP Gross Margin of 54.4%.

But 2025 also showed the reality of selling into massive upgrade cycles: timing isn’t always yours to control. Harmonic said its 2025 broadband revenue guidance reflected shifting operator deployment schedules tied to the move toward Unified DOCSIS 4.0. “Our prudent 2025 Broadband revenue guidance reflects shifts in customer deployment timing as operators transition to Unified DOCSIS 4.0. These trends are industry-wide and we believe they are short-term in nature.”

Then came another signal that Harmonic’s center of gravity had moved. Patrick Harshman retired as President and Chief Executive Officer effective June 11, 2024, and the company named Nimrod Ben-Natan—then Senior Vice President and General Manager of Harmonic’s Broadband business—as his successor.

Ben-Natan’s story is basically the internal version of Harmonic’s own evolution. He joined in 1996 as a software engineer working on Harmonic’s first-generation video transmission platform. He had led the Broadband business since 2012, and Harmonic credited him as a key driver behind the development and broad deployment of its Emmy award-winning cOS virtualized broadband technology.

Choosing Ben-Natan wasn’t just a standard succession plan. It read like a strategic statement: the future of Harmonic would be built around broadband infrastructure, not video services. His decades at the company brought institutional memory, but his day job—running Broadband—matched the company’s post-divestiture identity.

As of December 31, 2024, Harmonic reported 133 issued U.S. patents and 48 issued foreign patents, with 48 patent applications pending—evidence of how much of this company’s value still sits in engineering and IP.

If the MediaKind transaction closes as expected, Harmonic emerges simpler: a focused provider of virtualized broadband infrastructure for cable operators in the middle of multi-year network upgrades. The approximately $145 million in cash proceeds would strengthen the balance sheet and give Harmonic more flexibility—whether that means acquisitions, expanded R&D, or simply investing harder in the broadband roadmap that now defines the company.

X. Business Model Deep Dive & Strategic Positioning

To understand Harmonic’s competitive position, you have to look at it the way its customers do: as infrastructure. Not a nice-to-have tool, but gear and software that sits right on the critical path of delivering service. That’s a different game than consumer tech or even most SaaS. The economics are shaped by long sales cycles, deep technical integration, and, once you’re in, switching costs that can be punishing.

The Infrastructure Business Dynamics:

Infrastructure businesses tend to be expensive to win and hard to lose. The upfront work is heavy—evaluations, pilots, integration, operational testing—but once a system becomes part of the network, it’s sticky. Retention isn’t driven by brand affinity; it’s driven by risk avoidance. Nobody wants to be the person who caused the outage by ripping out a core platform.

Harmonic’s broadband business is a clean example of this dynamic. Comcast framed it in plain operator language: “We are rapidly expanding our network to new areas and by leveraging Harmonic's cOS platform provides us with the flexibility to use fiber or extend our existing DOCSIS-based infrastructure to deliver critical connectivity to homes and businesses,” said Dan Rice, vice president of Access Engineering, Comcast.

That “flexibility” line is doing a lot of work. If Comcast or Charter deploys CableOS at scale, it isn’t just installing software. It’s wiring Harmonic into network management systems, provisioning platforms, and day-to-day operational workflows. Replacing that kind of platform isn’t like swapping a vendor in procurement. It’s a multi-year parallel run with real operational risk.

Platform Transition Playbook:

Harmonic’s long survival through repeated platform shifts leaves a pretty clear pattern—useful not just for understanding this company, but for evaluating any infrastructure player facing disruption:

- Willingness to cannibalize: The move from hardware to software meant giving up attractive near-term appliance revenue to stay relevant longer-term.

- Customer relationship preservation: Even as architectures changed, Harmonic kept selling into many of the same operators—and used those relationships as the bridge to the next platform.

- Technical depth: Real engineering competence in video compression and optical transmission kept the company from becoming obsolete when the industry’s “default architecture” changed.

- Patient capital: The software transformation took years to show up cleanly in financial results, even after the product strategy was set.

Revenue Model Evolution:

The business model has steadily shifted away from one-time hardware sales and toward recurring revenue. In video, VOS360 was the poster child for that change. In broadband, Harmonic has pushed in the same direction with subscription offerings like CableOS Central cloud services.

Harmonic’s messaging here is consistent: “CableOS deployments continue to gain momentum, and Harmonic is once again breaking barriers with its new CableOS Central service. Leveraging the rich data analytics available through our platform, CableOS Central is a powerful new service enabling operators to predict and address issues before they become service-affecting.”

Whether you buy the marketing language or not, the strategic intent is clear: turn a platform that used to be sold as infrastructure into a platform that also earns like a service.

Land-and-Expand Model:

CableOS also fits a land-and-expand pattern. Operators typically start with limited deployments to prove performance and operational fit. If it works, the footprint expands—often for years—until it becomes the default architecture across the network. That’s exactly the posture Charter has taken, with plans to use Harmonic’s cOS platform across its broadband customer base along with network and operational tools.

This is where infrastructure starts to look almost subscription-like, even when it isn’t formally SaaS. Once Harmonic lands a major operator, the follow-on expansion creates visibility that most pure hardware vendors never get.

Risks and Dependencies:

The flip side of this model is concentration risk. The customer pool in cable and telecom is small, consolidation is real, and when a handful of buyers control deployment timing, they also control your quarterly story. Add in rising competition from cloud providers and the pressure from legacy product declines, and you get a business that can feel stable operationally but volatile financially.

Technology transitions add another layer of uncertainty. DOCSIS 4.0 rollout timing has been hard to forecast, with operators adjusting schedules based on competitive dynamics and, critically, on when the broader ecosystem is ready. Harmonic executives reiterated that 2025 was expected to be a down year for broadband as the emergence of “unified” node, amplifier and modem chips for DOCSIS 4.0 affected deployment timing for some cable operators.

That’s the infrastructure trade: when the cycle is on, it’s powerful. When the cycle pauses, even briefly, you feel it immediately.

XI. Competitive Landscape & Market Dynamics

Harmonic plays in markets where the customers are huge, the buying cycles are long, and the technology doesn’t sit still. The competitive story also depends entirely on which side of the house you’re talking about—broadband infrastructure versus video.

Broadband Infrastructure Competition:

In virtual CMTS and distributed access architecture, Harmonic has gone head-to-head with a familiar cast of telecom and cable equipment names, including Arris Group Inc., Cisco Systems Inc., Casa Systems Inc., Nokia Corp., and Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd.

But the field has been shifting in Harmonic’s favor. Casa Systems filed for bankruptcy protection in 2024, taking a meaningful rival off the board. CommScope, which acquired ARRIS, has wrestled with heavy debt and operational challenges. Cisco, once a heavyweight in cable infrastructure, has increasingly de-emphasized the category to focus elsewhere.

And operators aren’t standardizing on a single vendor for everything. Charter’s hybrid fiber-coax upgrade, for example, has pulled in multiple suppliers: Applied Optoelectronics for 1.8GHz amplifiers, line extenders, and remote management software; Vecima Networks for nodes, network orchestration software, and testing systems; and ATX Networks for amps and nodes.

The broader takeaway is that cable operators have been leaning toward specialists—vendors that live and breathe cable broadband operations—rather than generalists trying to cover ten markets at once. That preference has helped companies like Harmonic, especially as the industry moved toward software-defined access.

Video Infrastructure Competition:

Video is a different battlefield. Harmonic positioned itself as a leader in video delivery solutions, with SaaS and software platforms designed for high-stakes use cases like live sports and event streaming, targeted advertising, and playout across cloud, on-premises, and hybrid environments.

Competition here comes from both ends. On one side are the hyperscalers—AWS Media Services, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure—offering broad cloud building blocks for encoding and delivery. On the other side are specialists competing product-by-product, including Imagine Communications, Ateme, and Elemental (owned by AWS).

Against that backdrop, the planned sale of Harmonic’s Video segment to MediaKind is also a sign of where the industry is going: consolidation, scale, and an arms race in SaaS streaming infrastructure. Harmonic described the combination as creating a world-class independent SaaS streaming infrastructure provider, bringing together two established organizations with complementary strengths across SaaS streaming, appliance platforms, and cloud AV workloads. Harmonic said the combined company would serve a blue-chip customer base and generate more than $100 million in annual recurring revenue.

M&A Considerations:

Given how strategic broadband infrastructure has become—and how concentrated the buyer base is—Harmonic has lived under a cloud of M&A speculation for years. The logic usually sounds like some variation of:

- Too small to go toe-to-toe with hyperscalers in video infrastructure over the long run

- Large enough to matter as a broadband infrastructure leader

- Potentially attractive to private equity looking for infrastructure-like assets and long-duration customer relationships

- A plausible target for larger players in the cable ecosystem

And if the MediaKind transaction closes and Harmonic becomes a more focused broadband company, that clarity could cut both ways: it makes the story easier to understand, and it makes the remaining business easier to value—and, in theory, easier to buy.

XII. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces:

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate-Low

Breaking into vCMTS isn’t like launching a new app. It takes deep technical expertise, sustained R&D, and—most importantly—trusted relationships with a small set of very demanding operators. Sales cycles run long, deployments are risky, and the default posture of an operator is “don’t touch what works.” The one caveat is capital: a well-funded tech player could try to buy its way in through acquisition.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low-Moderate

Harmonic’s strategy of running core functions on standard server hardware limits supplier leverage. There are pockets—like specialized optical components—where suppliers can have more influence because there are fewer credible sources. But overall, Harmonic isn’t boxed in by a single critical supplier the way some hardware-heavy businesses are.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High

This is the big one. Harmonic sells to a small number of enormous customers, and that concentration shows up in the numbers: Comcast and Charter represented about 46% of revenue in Q1 2024. Customers with that kind of weight can pressure pricing, contract structure, and deployment timing. The counterbalance is switching costs: once a platform is deployed and operationalized, the buyer’s leverage drops because replacing it becomes painful and risky.

Threat of Substitutes: Moderate

In broadband, the clean substitute to an HFC network running DOCSIS is fiber-to-the-home. But at the scale cable operators operate—tens of millions of locations—moving everything to passive optical networking and FTTP is still far more expensive than upgrading DOCSIS for a fraction of the cost. Fixed wireless access is another substitute, especially in markets where it’s “good enough,” but it comes with different performance trade-offs and capacity constraints.

Competitive Rivalry: Moderate-High

The competitive field has narrowed—Casa Systems’ struggles are the clearest example—but rivalry stays intense because the stakes are huge and the technology is still evolving. Even if the current competitor set is thinner, the category remains attractive enough that well-capitalized players can re-enter, and operators often design their networks to avoid dependence on a single vendor.

Hamilton's 7 Powers:

1. Scale Economies: Limited

This isn’t a winner-take-all market. Multiple vendors can serve cable infrastructure profitably, and operators deliberately maintain multi-vendor strategies to preserve leverage and reduce risk.

2. Network Effects: Minimal

As with most B2B infrastructure, Harmonic doesn’t get stronger because more customers use it. The value comes from technical performance and the ability to execute deployments, not from network-driven flywheels.

3. Counter-Positioning: Moderate-High

Harmonic’s move into virtualization and software-defined infrastructure let it counter-position against legacy hardware vendors. It could offer a model incumbents couldn’t easily match without undercutting their own appliance businesses.

4. Switching Costs: High

This is the strongest power in the portfolio. Comcast has been Harmonic’s marquee customer for cOS, a virtualized, cloud-based system underpinning its vCMTS strategy, and Comcast has also been a key buyer of Harmonic nodes. Those pieces support Comcast’s shift toward a distributed access network and its rollout of DOCSIS 4.0 upgrades. Once that kind of platform is deployed across millions of subscribers, it becomes deeply embedded in operations—replacing it is expensive, slow, and fraught with outage risk.

5. Branding: Low-Moderate

Infrastructure buyers don’t buy the logo. They buy reliability, performance, and total cost of ownership. Still, track record matters, and Harmonic’s leadership position and deployment history do influence high-stakes purchasing decisions.

6. Cornered Resource: Moderate

Harmonic’s accumulated expertise in video compression, broadband access, and distributed architectures is real, and it’s reinforced by IP: 133 issued U.S. patents and 48 issued foreign patents, with 48 applications pending as of December 31, 2024. But there isn’t a single magical resource competitors can’t eventually replicate with enough time and money.

7. Process Power: Moderate-High

Decades of deployments across operators create a kind of advantage that doesn’t show up in a datasheet: knowing how to make this stuff work in the messy reality of real networks. That operational muscle—integrations, troubleshooting, rollout playbooks, and field experience—gives Harmonic an edge that new entrants have to earn the hard way.

Primary Powers Assessment:

Harmonic’s most durable advantage comes from Switching Costs and Process Power. Once it’s embedded in an operator network, displacement becomes a high-risk project—and Harmonic’s accumulated deployment experience makes it harder for competitors to out-execute them on the ground.

The vulnerability is what Harmonic doesn’t have: Scale Economies and Network Effects. Without those, the moat doesn’t automatically widen over time. The company has to keep investing in R&D and keep winning trust—year after year—to hold its position.

XIII. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

Three Distinct Opportunities:

Post-divestiture, the bull story is that Harmonic becomes a cleaner bet on cable broadband infrastructure—with a few extra shots on goal if the roadmap plays out.

-

Cable Broadband (Core Business): The DOCSIS 4.0 upgrade cycle is a multi-year infrastructure spend. Mediacom, for example, has selected a group of partners—including ATX Networks, Harmonic, and Hitron—for an initial DOCSIS 4.0 upgrade aimed at enabling symmetrical multi-gigabit speeds and lower latency.

-

Fiber Expansion: Harmonic also has a way to participate in fiber buildouts. The company said Comcast will use Harmonic’s virtual broadband network gateway and remote optical line terminal products for fiber network expansion projects. Comcast has said it is on pace to build fiber to about 1.2 million new locations.

-

International Growth: The broadband segment’s “Rest of World” revenue grew more than 50% in Q4 2024—a reminder that this story isn’t just U.S. cable giants.

Technology Leadership: Harmonic positions itself as a leader in next-generation cable access, anchored by its cOS platform and its Unified DOCSIS 4.0 roadmap. That roadmap calls for downstream speeds up to 13 Gbps—an important step-change if operators move aggressively into multi-gig services.

Market Position: Harmonic has cited a 62% market share in Distributed Access Architecture and 98% in virtual CMTS solutions—an unusually strong position in the categories that matter most for the cable industry’s next architecture.

Financial Improvement: Selling the Video business brings in $145 million in cash, strengthening the balance sheet and giving management more freedom in capital allocation. The company has also announced a $200 million stock buyback authorization, signaling confidence in the valuation.

Valuation: Even with its infrastructure positioning, Harmonic has often traded at modest multiples relative to pure-play infrastructure software companies. The bull case is that the market still underappreciates how durable these broadband customer relationships can be once deployments scale.

Bear Case:

Customer Concentration: The biggest risk is still concentration. Comcast and Charter have outsized influence on Harmonic’s results, and a shift in either operator’s spending can swing the story quickly. In Q1 2025, Comcast represented 34% of Harmonic revenue and Charter represented 12%.

Cable Industry Headwinds: Broadband competition has tightened. Comcast’s Xfinity internet service reported losing 110,000 domestic high-speed internet subscribers in Q2, and Charter’s Spectrum reported losing 154,000 residential broadband customers in Q2. In both cases, the losses continued—and accelerated—trends that had already begun.

Technology Transition Timing: Timing risk is real, and it shows up in results. Harmonic reported consolidated revenue of $142 million, down 27.3% year-over-year. Broadband revenue declined 37.7% year-over-year to $90.5 million as the company waited for unified DOCSIS 4.0 deployments to ramp. If the DOCSIS 4.0 transition continues to take longer than expected, revenue variability stays high and forecasting remains difficult.

Competitive Threats: Competition has weakened in places, but that doesn’t mean it’s gone. Well-capitalized entrants could re-enter. And while the planned sale of the Video business reduces the risk of streaming platforms insourcing capabilities from Harmonic, it doesn’t eliminate competitive pressure in the markets Harmonic will keep.

Profitability Challenges: Harmonic has been in the infrastructure business for decades, but consistent profitability has been hard. Staying competitive requires continuous investment, and that R&D and execution burden can consume capital that shareholders would rather see turned into durable free cash flow.

Key Metrics to Watch:

To track whether the story is working in real time, focus on:

-

CableOS Customer Count and Modem Deployments: This is the clearest read on adoption. Harmonic ended Q3 with 142 cOS deployments supporting 37 million cable modems worldwide, up from 136 cOS customers and 35.3 million modems at the end of the prior quarter.

-

Customer Concentration Trends: A reduced dependence on the biggest accounts would materially lower risk.

-

Broadband Segment Gross Margins: If the mix keeps shifting toward software and services, margins should expand. If margins don’t improve, it raises the uncomfortable possibility that competition is pressuring pricing more than the narrative suggests.

XIV. Lessons & Takeaways: The Playbook

Harmonic’s story is a reminder that infrastructure isn’t glamorous, but it is durable. If you can stay on the critical path of how an industry operates—through multiple rewrites of the underlying technology—you can survive far longer than anyone expects. Harmonic did that by making a series of uncomfortable choices at exactly the moments when comfort was the most tempting.

Lesson 1: Infrastructure businesses can survive platform shifts if they’re willing to cannibalize

The move from purpose-built appliances to software platforms wasn’t a simple product refresh. It meant trading near-term revenue and cleaner margins for a messier transition period. Harmonic accepted that pain, and by doing so it positioned itself for a world where video processing and delivery increasingly ran on cloud and commodity compute. Companies that cling to legacy revenue streams tend to get stranded when the platform shift finishes.

Lesson 2: Technical depth creates optionality

Harmonic’s engineering depth—video compression, optical transmission, and the operational reality of running carrier-grade systems—kept it relevant as the industry’s architecture changed. The real advantage wasn’t a single product. It was the ability to re-apply hard-won expertise to the next problem set.

Lesson 3: Customer relationships are assets

Harmonic didn’t rebuild from scratch every time the market changed. It repeatedly sold the next generation of infrastructure into many of the same operators, because decades of reliability compound into trust. In infrastructure, trust is distribution. It’s how you get your next product trial when budgets tighten and the default answer is “no.”

Lesson 4: “Boring” infrastructure businesses can have exciting pivots

On the surface, this is a company that sold boxes to cable headends. In practice, Harmonic reinvented itself into cloud streaming workflows, then into software-defined broadband access. The lesson isn’t that every infrastructure company will have a dramatic pivot. It’s that the ones that do can create value in places outsiders never thought to look.

Lesson 5: Being early to platform shifts can offset lack of scale

Harmonic didn’t have the scale economies of the biggest network equipment players. So it leaned on speed, focus, and execution—getting early in virtualized cable access with CableOS while larger competitors were still defending hardware-heavy models. In markets without runaway network effects, timing and shipping matter.

Lesson 6: Optionality has value

The AI data center angle is speculative, but it’s a useful framing: capabilities built for one infrastructure era can become relevant in a completely different one. Even if silicon photonics never becomes a major Harmonic revenue engine, the broader point holds. Infrastructure companies with real technical DNA often have adjacent options the market doesn’t price in until the moment arrives.

Lesson 7: Financial discipline matters less than strategic positioning in platform transitions

During the software transformation, Harmonic tolerated margin compression and volatility because optimizing for short-term optics would have constrained the pivot. In platform shifts, the biggest risk isn’t an ugly quarter. It’s building a business that looks healthy right up until the market no longer needs it.

For Founders:

- Disrupting yourself before someone else does is often the only defensible strategy

- Deep technical moats can compensate for not being the biggest player

- Platform transitions look like threats, but they can also be the opening to leapfrog incumbents

For Investors:

- Infrastructure businesses can compound slowly, then change in steps when a new architecture takes hold

- Customer concentration is the price of selling into critical systems—and it needs to be underwritten explicitly

- “Hidden” optionality can exist in pivoting companies, but it’s rarely the base case

- Narrative shifts (cable → streaming → broadband → AI) can drive re-rating, sometimes faster than fundamentals catch up

XV. Epilogue: What's Next for Harmonic?

The 2025–2030 question for Harmonic is no longer “can they juggle two very different businesses?” If the Video segment closes into MediaKind as planned, the company becomes a far more focused bet—and that makes execution in broadband the whole ballgame.

Cable’s upgrade cycle is big, technically complex, and notoriously hard to time. Harmonic’s job is to stay on the critical path of it.

Cable Broadband: Steady Growth or Transition Year?

Harmonic has said it expects broadband revenue growth in 2026 as Charter and other operators accelerate DOCSIS upgrades, along with additional business tied to fiber deployments. The tricky part is that “when” has been the moving target. Operators keep adjusting schedules as the ecosystem—nodes, amplifiers, and modems—lines up around Unified DOCSIS 4.0.

But the roadmap itself keeps stretching outward, which is exactly what an infrastructure vendor wants to see. CableLabs President and CEO Phil McKinney has pointed to what comes after DOCSIS 4.0 starts landing broadly in the field: an “optional annex” that could raise the spectrum ceiling to 3GHz and enable speeds of 25 Gbit/s, and even the longer-range possibility of pushing HFC and DOCSIS to 6GHz, with speeds of 50 Gbit/s.

The takeaway isn’t the exact number. It’s that cable’s technical ceiling still has headroom, and that implies sustained investment—just with lumpy timing and frequent rescheduling.

Streaming: Transition to MediaKind

"Together, we would create the leading independent streaming infrastructure company, giving customers a stronger, more reliable partner to power the future of video."

If that’s the vision, then MediaKind becomes the home for Harmonic’s video platform—streaming and broadcast infrastructure, run as the whole mission, not one segment competing for attention and capital.

For Harmonic shareholders, the logic is simpler: $145 million in cash, a cleaner story, and fewer internal trade-offs. Instead of having to explain both a broadband infrastructure cycle and a video market that keeps evolving under their feet, Harmonic gets to be judged on one thing: whether cOS keeps expanding into operator networks.

M&A Scenarios:

After the divestiture, Harmonic also becomes easier to underwrite for would-be buyers. A focused broadband infrastructure company with entrenched deployments can look attractive to:

- Private equity firms looking for infrastructure-like assets and the potential for steadier cash flows

- Larger cable ecosystem players that want to secure access technology and reduce vendor risk

- Strategic acquirers aiming to consolidate the virtualized access market

In other words, the two-segment structure may have made Harmonic harder to value. A single core business can do the opposite.

Wild Cards:

A few things could still swing the story in either direction:

- DOCSIS 4.0 deployments accelerating—or slipping again

- Further consolidation among cable operators, including the pending Charter-Cox transaction

- New competitive threats emerging as the prize becomes clearer

- Regulatory changes that reshape broadband infrastructure incentives and investment

Final Reflection:

Harmonic is, in many ways, a company that shouldn’t have made it this far—and then kept going anyway. It started with fiber optic gear for cable headends, pushed into cloud-native streaming infrastructure, and then built a serious position in virtualized broadband access. Each reinvention was forced by a platform shift that could have ended the story.

The December 2025 agreement to sell the Video business to MediaKind is the capstone on that long transformation. What’s left is a more focused, potentially more valuable company—but also one that lives and dies by a small set of giant customers and by the pace of a multi-year cable technology transition.

For investors, that’s the trade. If you can live with concentration risk and timing uncertainty, Harmonic offers exposure to critical broadband infrastructure with relatively few pure-play alternatives. And as a case study, the lesson is timeless: in infrastructure, survival isn’t just about having great technology. It’s about having the discipline—and the nerve—to change your business before the market changes it for you.

XVI. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Long-Form References:

-

Harmonic Inc. SEC Filings (10-K, 10-Q, Proxy Statements) - The best primary source for strategy, risks, segment reporting, and how management explains the business in its own words.

-

"The Innovator's Dilemma" by Clayton Christensen - The classic framework for making sense of platform transitions, disruption, and why “doing the rational thing” can still get incumbents killed.

-

"7 Powers" by Hamilton Helmer - A practical way to think about durability: where competitive advantage actually comes from, and what happens when you don’t have scale or network effects to hide behind.

-

Light Reading (LightReading.com) - Consistently strong coverage of cable, broadband, video infrastructure, and optical networking, with the kind of industry detail that rarely makes it into mainstream tech press.

-

"Streaming, Sharing, Stealing" by Michael D. Smith & Rahul Telang - A clear-eyed look at the economics of streaming video markets and how distribution reshapes value capture.

-

IEEE Photonics Journal - Technical papers on silicon photonics and optical interconnects, useful for separating what’s real from what’s hype.

-

CED Magazine archives - A window into the cable industry’s evolution over decades, including the unglamorous realities of how networks get upgraded.

-

"The Master Switch" by Tim Wu - A broader history of information industries that helps explain why consolidation and control tend to follow periods of openness.

-

RCR Wireless News coverage of DOCSIS evolution and cable broadband - Helpful reporting on access network technology and how the DOCSIS roadmap translates into real-world operator plans.

-

Conference presentations from NAB Show, SCTE Cable-Tec Expo, OFC - Where roadmaps, demos, and technical direction often show up before they’re visible in earnings calls.

Key Industry Reports:

- Dell'Oro Group - Optical networking and video infrastructure market data

- IHS Markit / S&P Global - Cable infrastructure spending forecasts

- Heavy Reading - Video streaming infrastructure analysis

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music