Hecla Mining Company: America's Oldest Precious Metals Producer

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

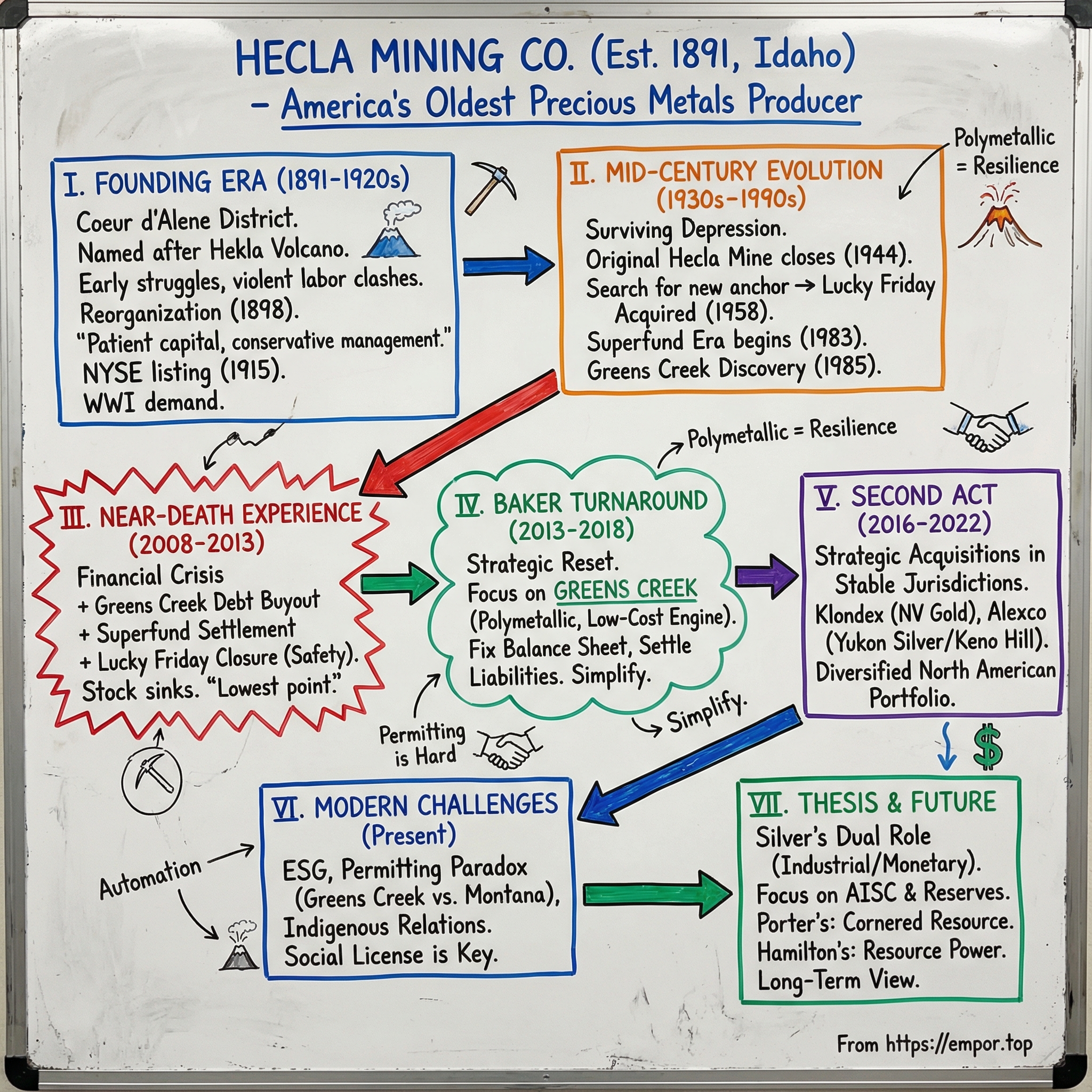

Picture the rugged mountains of northern Idaho in 1891. The air is thin, the winters are brutal, and the ground beneath your boots holds secrets worth dying for—and many men did. In makeshift camps scattered across the Coeur d'Alene district, prospectors with pickaxes and big, desperate dreams chewed tunnels into mountainsides, chasing silver veins that flashed in candlelight. Among the dozens of outfits born in that rush, one took the name Hecla—after Iceland’s most famous volcano, a mountain ancient Norse legends treated like a doorway to the underworld.

One hundred thirty-four years later, Hecla is still here. And in mining, “still here” is the whole point.

Founded in 1891, Hecla Mining Company has grown into the largest silver producer in the United States and Canada, and the oldest NYSE-listed precious-metals mining company in North America. Today it accounts for more than a third of U.S. silver output, and nearly a third of Canada’s.

So how does a 134-year-old mining company survive the full gauntlet—booms and busts, world wars, labor conflict, regulatory revolutions, and environmental disasters—and keep producing? How does a company that once pulled ore worth only about $14,000 from the ground in its first seven years become an operator posting record sales approaching a billion dollars?

The answer isn’t a single lucky strike. It’s a mix of geology, yes—but also disciplined capital allocation, operational grit, and an almost unfashionable willingness to play the long game in an industry that punishes impatience.

In 2024, Hecla reported silver reserves of 240 million ounces and produced 16.2 million ounces of silver—both the second-highest marks in its history. Total sales hit a record $929.9 million. This isn’t a legacy company living off old stories. It’s a business that, after more than a century of reinvention, has found a modern stride.

Hecla’s story is also a crash course in what it takes to win—or just survive—in capital-intensive industries: balance-sheet discipline when cycles turn, relentless reinvestment in a depleting asset base, and the strategic necessity of earning social license in a world that demands more from miners than production alone. And it includes a chapter where the company nearly disappears. The near-death stretch from 2008 to 2013 brought Hecla to the edge; the pivot that followed reshaped everything that came after.

Today, Hecla operates mines in Alaska, Idaho, Quebec, and Canada’s Yukon Territory. But the road from a single claim near Burke, Idaho to a diversified North American precious-metals producer was anything but straight. It meant surviving the closure of the original Hecla mine in 1944, navigating the Coeur d’Alene district’s Superfund-era reckoning, and executing a turnaround that took the company from near-bankruptcy back to industry leadership.

II. Founding Era & The Silver Kings (1891–1920s)

The Coeur d'Alene mining district in northern Idaho was no place for the faint of heart in the 1880s. Prospectors armed with picks, shovels, and desperate optimism pushed through dense forests and over knife-edge ridges, chasing rumors that could turn into fortunes—or funerals. Gold had been discovered in 1882, but it was silver and lead that made the district famous. And violent.

The Hecla claim entered the record on May 5, 1885, when James Toner filed it. He passed it to A.P. Horton, who sold it to George W. Hardesty and Simon Healey. By July 1, 1891, Patrick “Patsy” Clark owned it outright. The ground had changed hands like a hot poker, with the final sale price landing at a modest $150—an amount that reads like a typo when you know what the rocks would ultimately contain. Over the next 134 years, that little claim would yield mineral value measured not in thousands, but in tens of billions.

On September 29, 1891, Clark formed the Hecla Mining Company with Albert Gross and Charles Kipp. Two weeks later, on October 14, the company was incorporated in Idaho by Clark, Kipp, John A. Finch, and Amasa B. “Mace” Campbell, along with several other founders. Seven businessmen—some local, others from the East, especially Chicago and Milwaukee—capitalized the venture at $500,000.

They named it “Hecla” after Mount Hekla in Iceland, one of Europe’s most active volcanoes. In Icelandic folklore, Hekla was said to be a gateway to purgatory—or hell. If that sounds melodramatic, consider the job description: descend underground, chase narrow veins through unstable rock, and hope the mountain doesn’t decide to reclaim you.

And at first, the mountain didn’t even pay.

During its first seven years, Hecla produced ores worth no more than $14,000. Around it, the Coeur d'Alene district looked less like a boomtown and more like an armed camp. Miners in Shoshone County organized local unions through the 1880s; mine owners countered by forming a Mine Owners’ Association. In 1891 alone, the district shipped ore containing $4.9 million in lead, silver, and gold—enough money to harden everyone’s position and raise the stakes of every conflict.

Those conflicts exploded into some of the most violent labor clashes in American industrial history. The governor declared martial law and sent in six companies of the Idaho National Guard to suppress what officials called “insurrection and violence.” Federal troops arrived too, and they confined six hundred miners in bullpens without hearings or formal charges. The strike failed—but the backlash helped fuel something bigger. In May 1893, representatives from the broken union met with delegates from other Rocky Mountain unions to form the Western Federation of Miners, which would go on to recruit more than 200,000 members by the turn of the century.

Inside Hecla, the early years forced a hard lesson: this wasn’t a business you could hype your way through. After the company’s underwhelming start, management chose a reset. In 1898, Hecla reorganized. By then, more than half of the original founders had died, moved on, or sold out. That first reorganization also set a pattern that would echo through the next century: patient capital, conservative management, and a willingness to rebuild after near-failure rather than bet the company on one more roll of the dice.

Stability followed. Hecla stock listed on the New York Curb Exchange on September 23, 1915. Dividends, paid monthly since March 1904, became quarterly in 1918. Operationally, the company tightened its system too: in July 1917, Hecla began sending ore to the Bunker Hill Mine and Smelting Complex in Kellogg, Idaho, and by 1918 the Hecla shaft had reached 2,000 feet.

Then World War I changed the equation. Metals weren’t just commodities—they were strategy. Silver, lead, and zinc fed munitions, electrical systems, and industrial production. The Coeur d'Alene district roared, and Hecla expanded to meet wartime demand.

The 1920s delivered both setback and discovery. In July 1923, a fire tore through Burke’s business district and destroyed most of it, including Hecla’s surface plant, knocking the mine out of business for almost six months. Use and Occupancy Insurance covered the loss, and Hecla rebuilt—this time with concrete and steel. In 1924, ore was found in the Star, and a substantial ore body was discovered in the Hecla at the 2,800-foot level.

So why did Hecla survive when hundreds of peers didn’t?

It wasn’t because they avoided danger—mining doesn’t offer that. It was because they avoided the other killer: overreach. Conservative financial management, patience in downturns, and a refusal to over-leverage in boom times became Hecla’s DNA. Competitors borrowed big, expanded fast, and collapsed when prices turned. Hecla learned to treat cycles like gravity: you can’t negotiate with them, but you can build your business so it doesn’t break when they hit.

III. Mid-Century Evolution: Consolidation & Modernization (1930s–1990s)

The Great Depression didn’t just squeeze miners. It broke them. Silver prices fell, demand for lead and zinc dried up, and layoffs swept through the Coeur d'Alene district. Hecla got hit too—but it had something most competitors didn’t: the balance sheet to endure. Limited debt and a conservative posture gave the company time, and in mining, time is often the difference between survival and liquidation.

Hecla used that breathing room to consolidate. In 1930, it gained control of the Polaris Mine. Over the next few years, it went to work stitching the neighborhood together: developing Polaris with a shaft starting in 1933, buying surrounding ground like the Silver Summit in 1935 and the Chester in 1936, and extending the Silver Summit tunnel to connect to the Polaris shaft.

One of the more telling details in that period is who showed up alongside them. The Polaris Development & Mining Company included 10 percent ownership by Newmont Mining Corporation in 1934, and Newmont’s exploration geologist, Fred Searls, joined Hecla’s board. For Hecla, partnering with one of the era’s rising mining powers was a signal: this company was no longer just trying to keep one mine running. It was learning to play offense—buying distressed assets when others were forced sellers, developing them patiently, and positioning for the next upcycle.

Then came the moment every depleting-asset business eventually faces: the ore runs out.

In 1944, the original Hecla mine—the company’s namesake and foundation—closed at a depth of 3,600 feet after yielding more than nine million tons of ore and generating $81 million in net smelter returns. That shutdown wasn’t just operational. It was identity-level. Hecla had other properties in the fold, and the Star mine was finally producing meaningful income, but without a large anchor mine, the company suddenly felt unmoored. From 1944 on, Hecla was searching for a replacement big enough to become the new center of gravity.

In the immediate postwar years, Hecla operated “much like a holding company,” leaning on zinc production at the Star mine while hunting for the next long-life asset. Not every swing connected. One notable miss was an investment in a silver mine named Rock Creek, where Hecla put in roughly $500,000 for development before selling the property at a loss in 1955. Other attempts took Hecla well outside hard-rock mining entirely: it acquired a Seattle manufacturer of movable ceiling panels, Accesso Systems, Inc., and also Ace Concrete Company in Spokane. But diversification didn’t solve the core problem. Hecla didn’t need side businesses. It needed great rocks.

The salvation turned out to be another Coeur d'Alene silver-lead mine with a memorable name: Lucky Friday.

Lucky Friday’s story started before Hecla ever owned it. On March 30, 1939, Sekulic and Charles E. Horning organized the Lucky Friday Silver-Lead Mines Company in Idaho and issued 1,200,000 shares. Early work included sinking a 100-foot shaft, which showed enough promise to justify a contract with Albert H. Featherstone’s Galconda Lead Mines, Inc. to push the shaft to 600 feet. By January 1942, Lucky Friday shipped its first ore—478 tons.

Hecla began buying into Lucky Friday in 1958, eventually becoming the largest owner at 38 percent. In 1964, Lucky Friday Silver-Lead Mines Co. merged into Hecla Mining. For Hecla, it was exactly what the post-1944 years had been missing: a large, productive, long-life operation that could carry the company for decades.

Lucky Friday went on to become one of the top seven primary silver mines in the world based on silver equivalent ounces, and it celebrated its 75th anniversary in 2017. And with the #4 Shaft project, the mine was expected to have another 20 to 30 years of life.

The 1970s delivered the full commodity-cycle emotional whiplash. A surge in silver prices gave Hecla the chance to escape debt from the Lakeshore venture in just a year and a half. The market rewarded the turnaround brutally fast: Hecla’s stock rose from $5.25 in January 1979 to a high of $53.50 twelve months later, making it the best performer on the New York Stock Exchange that year. The Hunt brothers’ attempt to corner the silver market drove prices to historic highs in 1980, and Hecla shareholders rode that wave to extraordinary gains.

But the decade’s most lasting shift wasn’t a price spike. It was regulation—and accountability.

In 1983, the broader Coeur d'Alene area was designated a Superfund site by the Environmental Protection Agency because of land, water, and air contamination from a century of largely unregulated mining. For the district, it was a reckoning. For Hecla and its peers, it changed the operating environment permanently. Mining was no longer just about geology and metallurgy. It was now about permits, cleanup, liability, and whether a company could adapt to an era where the costs of the past started showing up on the balance sheet.

While that storm gathered in Idaho, Hecla was quietly building the asset that would define its future. In 1985, the company discovered the Greens Creek deposit on Alaska’s Admiralty Island, within the Tongass National Forest. It was polymetallic—silver and gold, yes, but also zinc and lead—exactly the kind of high-grade, diversified ore body that could smooth out some of the volatility that pure silver producers live and die by.

By 2000, Hecla had two cornerstone assets: Lucky Friday in Idaho and Greens Creek in Alaska. It finally had the kind of portfolio that looks stable from a distance.

Up close, though, the next decade would prove stability was an illusion—and Hecla was about to face the most dangerous stretch in its modern history.

IV. The Near-Death Experience: 2008–2013

The 2008 financial crisis hit mining like an avalanche. Silver didn’t drift down—it fell off a cliff, sliding from nearly $20 an ounce to under $9 in a matter of months. Credit vanished. Hedging desks tightened. Lenders started asking uncomfortable questions. Across the industry, companies that looked fine on Monday were negotiating survival by Friday.

Hecla entered that storm with its biggest bet in decades already on the table.

On April 16, 2008, the company bought out Rio Tinto’s subsidiaries that held a 70.3% stake in Greens Creek, turning Hecla into the clear controlling owner of what was already a world-class, low-cost silver mine. The price was steep: $700 million in cash, plus 4,365,000 shares of common stock valued at $53.4 million. To make it happen, Hecla leaned heavily on a $380 million credit facility.

In normal times, this looked like a masterstroke—consolidate the crown jewel, capture the cash flow, and build the company around the best ore body in the portfolio.

But these were not normal times. Within months of closing, the commodity tape turned brutal. Silver cratered. Cash flows shrank. And Hecla was suddenly carrying significant debt in a market that had stopped forgiving leverage.

Then another bill came due—one from the past.

In 2011, Hecla finalized a major Superfund settlement tied to historic waste releases from its mining operations. The case had been filed by the Coeur d’Alene Tribe in 1991 and joined by the United States in 1996, and it ultimately became one of the largest Superfund cases ever brought. Under the settlement, Hecla agreed to pay $263.4 million plus interest to the United States, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe, and the state of Idaho. For a company already straining under downturn economics, it was another massive obligation landing on an already overloaded balance sheet.

And just as the financial pressure peaked, the operating floor gave way.

After a series of accidents that killed two miners within a year—Pete Marek in April 2011, followed seven months later by Brandon Lloyd Gray—federal regulators stepped in. The Mine Safety and Health Administration ordered Lucky Friday closed after an investigation that followed a December 14, 2011 rock burst. Hecla expected compliance to take through the end of 2012. The shutdown hit hard: it idled the mile-deep Silver Shaft, affected more than 200 workers, and forced Hecla to cut its expected 2012 company-wide silver production from 9.5 million ounces to 7 million. Inspectors issued dozens of citations and orders to both Hecla’s Lucky Friday unit and an independent contractor, Cementation USA.

This wasn’t a bad quarter. It was the nightmare scenario: the company’s second cornerstone mine went dark, just as the company was digesting a debt-heavy acquisition and a nine-figure environmental settlement. With Lucky Friday offline, Greens Creek had to carry the business at the exact moment the metals market was least forgiving.

The fallout spread fast. Shareholders filed class action securities lawsuits. The stock sank. Outside observers began asking the question that only comes up when a company is truly in trouble: does it make it?

From 2008 to 2013, Hecla lived at the edge of the cliff. This was the lowest point in its modern history, a stretch when a 120-year-old miner—built to survive cycles—was staring at the real possibility of bankruptcy.

Hecla’s response wasn’t elegant, but it was the kind of gritty, keep-the-lights-on decision-making that separates survivors from cautionary tales. The company raised emergency capital through dilutive equity offerings, renegotiated debt covenants, and kept Lucky Friday on skeleton operations while working through the safety and compliance requirements. It limped out of the period bruised and diluted, but still standing.

And in mining, still standing is the first step to a turnaround.

V. The Baker Turnaround: Strategic Reset & Greens Creek Optimization (2013–2018)

Philips S. Baker Jr. wasn’t a turnaround artist parachuted in at the eleventh hour. He’d already been in the top job for a decade when the crisis years hit, taking over as CEO in 2003—only the company’s 11th chief executive in more than a century. That kind of continuity tells you something about Hecla. It’s not built for flashy reinventions. It’s built for long, grinding endurance.

Baker was a mining engineer by training, but what mattered most in this moment was the combination: technical fluency plus financial discipline. He came in when silver was at one of its lowest points in three decades, and as the company lurched through 2008–2013, his playbook hardened into something simple and unromantic: focus on what works, cut what doesn’t, and rebuild the balance sheet so the next cycle doesn’t kill you.

The centerpiece of that reset was Greens Creek.

Hecla’s Greens Creek mine in southeast Alaska is one of the largest and lowest-cost primary silver mines in the world, and it became the cash-generating engine that kept the entire company moving. In 2024, Greens Creek produced 8.5 million ounces of silver at an all-in sustaining cost, after byproduct credits, of $5.65 per ounce.

The reason Greens Creek can do that comes down to what it is: a polymetallic deposit. It doesn’t just produce silver. It also produces zinc, lead, and gold. Those byproducts throw off real revenue, and that revenue offsets the cost of mining the silver. In strong byproduct years, the economics can get so favorable that it feels like the silver is almost along for the ride.

Greens Creek sits in the Tongass National Forest, within the Admiralty Island National Monument—making it the only U.S. mine permitted to operate inside a national monument. That’s not a fun fact. That’s a constraint. In a place like that, environmental performance isn’t a corporate value statement. It’s a condition of existence. Hecla invested accordingly, and the mine’s safety record and environmental stewardship became part of what allowed it to keep operating in such a sensitive jurisdiction.

Under Baker, the Greens Creek plan rested on three pillars: run the mine better, explore relentlessly, and spend capital like it’s scarce.

On operations, the mine runs continuously—24 hours a day, 365 days a year—and Hecla pushed hard on productivity and safety. In 2016, Greens Creek became the first U.S. underground mine to use automated loading technology from Sandvik, a meaningful step forward in both efficiency and risk reduction.

On exploration, the story is even more important. Mining is a depleting business; the ore body is always running out unless you replace it. Since Hecla’s full acquisition in 2008, systematic exploration kept reserves healthy despite steady production. Based on those reserves, Greens Creek carried an estimated 14-year mine life—an unusually strong position for a mine that had already been operating for decades.

And while Greens Creek was driving the future, Baker was also cleaning up the past. Hecla worked through legacy environmental liabilities that required hundreds of millions of dollars in expenditures. The $263 million Superfund settlement was painful, but it mattered: it removed a long-standing overhang and made the company easier to finance, easier to value, and frankly, easier to trust.

Hecla also tightened the portfolio. Baker sold the company’s mines in Venezuela, where Hecla had been the country’s largest gold producer. The exit was complicated, but the logic was clear: nationalization risk was rising, and capital belonged in stable jurisdictions. The company redeployed that focus toward strengthening its ownership position in Greens Creek—leaning harder into the asset that was actually working.

Even with Greens Creek performing, the turnaround years weren’t calm. Hecla endured a nearly three-year labor strike and a mineshaft fire that temporarily shut down operations at the Lucky Friday silver mine. But the discipline stayed consistent: protect the balance sheet, invest in the best assets, and don’t let short-term pressure force long-term mistakes.

By the time Baker departed in 2024, the arc was hard to miss. Hecla had gone from staring down existential questions to becoming North America’s largest silver producer again, posting record revenues and holding the second-highest silver reserves in its history.

VI. The Second Act: Strategic Acquisitions & Portfolio Transformation (2016–2022)

With Greens Creek throwing off cash and the balance sheet finally steady, Hecla could do something it hadn’t been able to do for years: think beyond the next quarter. The question shifted from “How do we survive?” to “Where do we put capital in an industry where the best assets are scarce, and permits can take a decade?”

The answer, in classic Hecla fashion, wasn’t to chase shiny new frontiers. It was to buy selectively, in tier-one jurisdictions, in a style of mining the company already knew cold: narrow-vein underground operations. The deals that followed made the strategy legible: be contrarian when assets are available, stay in places where the rule of law holds, and don’t stray too far from your operational edge.

In 2018, Hecla made its big move into Nevada, buying Klondex Mines in a $462 million cash-and-stock deal. Klondex owned the Fire Creek, Midas, and Hollister mines—three underground, narrow-vein gold properties. That detail mattered. Hecla wasn’t trying to learn an entirely new business; it was buying mines that fit its existing muscle memory. As Phil Baker put it at the time, opportunities to buy operating mines in Nevada’s prolific gold region don’t come along often.

The Klondex deal also signaled a portfolio pivot. Hecla was still, at its core, a silver company. But adding meaningful gold exposure diversified the revenue base and reduced the company’s dependence on a single metal price. It also planted a flag in one of the world’s most mining-friendly jurisdictions, giving Hecla a large land position—about 110 square miles—in Nevada.

It wasn’t an effortless integration. The Nevada operations needed investment—development work, exploration, and operational tuning to get the most out of the mines. But the logic held: diversify, add gold optionality, and expand where the permitting environment is workable.

The more consequential transformation came in 2022, when Hecla expanded its silver footprint again—this time north, into Canada. On September 7, 2022, Hecla and Alexco Resource Corp. announced the completion of Hecla’s acquisition of Alexco, bringing the Keno Hill property in the Yukon into the portfolio.

Keno Hill was exactly the kind of asset Hecla likes: high-grade, historically prolific, and located in a stable jurisdiction. The property spans 242 square kilometers and sits on one of the highest-grade silver districts in the world. From 1913 to 1989, the district produced more than 200 million ounces of silver from exceptionally rich ore, making it the second-largest historical silver producer in Canada.

Baker framed the acquisition in macro terms, pointing to silver’s role in clean energy and Hecla’s ambition to grow into that demand. He said that with Keno Hill, plus ongoing growth from Greens Creek and Lucky Friday, Hecla expected to lift annual silver production into the high teens of millions of ounces over the following years—meaningfully above 2021 levels—and to strengthen its position not just in the U.S., where it already produced a large share of domestically mined silver, but in Canada as well.

Structurally, the deal did two big things at once. First, Hecla paid Alexco shareholders in stock—issuing 17,992,875 shares under a 0.116 exchange ratio—valued at roughly $69 million at the time. Second, and arguably more important long-term, Hecla cleaned up Keno Hill’s economics by eliminating an existing silver stream. The silver streaming interest held by Wheaton Precious Metals was terminated in exchange for US$135 million of Hecla common stock.

That mattered because streams are forever. They can be a great way to finance a build, but they permanently siphon off upside from the mine. By paying Wheaton in stock to unwind the agreement, Hecla bought back the future.

Operationally, Keno Hill came with real substance. It produces silver, lead, and zinc concentrates from five deposits—Bellekeno, Lucky Queen, Flame & Moth, Onek, and Bermingham—and it wasn’t just a geologic idea on a map. The site was fully permitted and included a 400-tonne-per-day mill, an on-site camp, all-season road access from Whitehorse, and power from the Yukon Energy hydropower grid.

Put the pieces together and you get the second act of modern Hecla. These acquisitions shifted the company from a story of two cornerstone mines—Greens Creek and Lucky Friday—into a broader North American portfolio. By 2024, Hecla operated across Alaska, Idaho, Quebec, and the Yukon, with a business that was no longer one operational setback away from an existential crisis.

VII. The Modern Challenges: ESG, Permitting & Indigenous Relations (2015–Present)

In the 21st century, mining isn’t just about finding ore and extracting it at a profit. It’s about earning permission—over and over again. From regulators, from communities, from workers, and from the people who live downstream. Hecla’s recent history is a clean example of the new reality in developed countries: the rules are clearer and the jurisdictions are safer, but the bar is much higher—and the consequences of getting it wrong last for decades.

Nowhere is that clearer than in Coeur d’Alene. The Superfund designation didn’t fade with time; it followed Hecla like a shadow. A settlement was ultimately reached to resolve one of the largest cases ever filed under the Superfund statute. Under that agreement, Hecla would pay $263.4 million plus interest to the United States, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe, and the state of Idaho to resolve claims tied to waste releases from its historic operations.

That payment was brutal. But it also closed a chapter. With the legacy liability addressed, Hecla could stop fighting the past and focus on proving what “modern mining” actually looks like: serious environmental management, tighter safety systems, and community relationships that are built deliberately—not treated as an afterthought.

You can see the difference when you compare Greens Creek to Hecla’s Montana development projects.

Greens Creek is unusual even by Alaska standards. According to Greens Creek General Manager and Hecla VP Brian Erickson, it’s located within the Admiralty Island National Monument—making it the only U.S. mine permitted to operate inside a national monument. “That means our safety and environmental record must be among the best in the world right now,” Erickson says.

And Greens Creek doesn’t survive there by accident. It works because the mine has spent decades building credibility—operationally, environmentally, and locally. The mine is the largest taxpayer in the Juneau Borough, and Hecla is the largest private-sector employer and taxpayer in Juneau, Alaska. That kind of economic footprint doesn’t guarantee support, but it creates real alignment: the community benefits when the mine runs well, and the mine only keeps its privilege to operate by staying worthy of trust.

Montana is the cautionary counterpoint.

Hecla acquired Mines Management, Inc. to own 100% of the Montanore project in Sanders County near Libby, Montana. It also acquired Revett Mining Company, which resulted in full ownership of the Rock Creek project in Sanders County near Noxon, Montana. Together, those assets complement Hecla’s other holdings in the area, including the Troy Mine and the Rock Creek deposit.

On paper, these Montana projects represent enormous potential value. In practice, they’ve been trapped for years in permitting battles and opposition. Environmental groups, tribal nations, and local communities have raised concerns about impacts on wilderness areas and water quality. The result is the modern permitting paradox in a single sentence: you can have a great ore body and still never get to mine it.

Then there’s the third leg of the stool: Indigenous relations. In a growing share of North America, your ability to operate depends on more than compliance—it depends on partnership.

At Keno Hill, the property sits in a premier mining jurisdiction where the First Nation of the Na-Cho Nyak Dun and the Yukon government are supportive of mining. But that support didn’t just happen. It comes from years of relationship-building, revenue sharing, and doing the slow work of turning “stakeholders” into actual partners.

And it can unravel fast. Victoria Gold’s Eagle Mine heap leach pad incident in June 2024—unrelated to Hecla and Keno Hill—prompted the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun to take strong positions on mining activities within their Traditional Territory, where Keno Hill is located, including a call to halt all mining. It’s a sharp reminder of how fragile social license can be: one operator’s failure can spill over into everyone’s reality.

Put all of this together and you get the American mining paradox in high definition. The U.S. says it wants more domestic mineral production and fewer fragile foreign supply chains. But it also fights almost every new mine through years of litigation, permitting delays, and political opposition. For Hecla, that cuts both ways. Existing, permitted operations like Greens Creek and Lucky Friday become more valuable precisely because new supply is so hard to bring online. At the same time, development projects can sit for decades—rich in resource, poor in certainty—never turning into producing mines at all.

VIII. The Precious Metals Thesis: Macro, Fed Policy & Mining Economics

Silver is a strange metal. It’s money and it’s machinery. It trades like a precious metal when investors get nervous, but it’s consumed like an industrial input when the world is building. And because it sits at that crossroads, it also gets financialized to an extreme—pulled around by sentiment, rates, ETFs, and speculation in a way that can feel disconnected from what’s happening in physical supply and demand.

Hecla leans into that dual identity. As the company has put it: “With silver markets facing their fifth consecutive deficit year, driven by record industrial demand and growing safe-haven investment, Hecla's position as the largest silver producer in the U.S. and Canada positions us well to capitalize on these favorable fundamentals.”

The big shift over the last decade is simple: demand has gotten sturdier, and supply hasn’t kept up.

On the demand side, silver is riding real, structural trends. Solar photovoltaic installations, electronics, electric vehicles, and medical applications all pull on the same thread. And silver’s unique properties—the highest electrical and thermal conductivity of any element—mean you can’t just swap it out easily without performance tradeoffs. In many use cases, silver isn’t a luxury. It’s the best tool for the job.

On the supply side, the industry has run into the wall we’ve been talking about all episode: mines are hard to permit, expensive to build, and increasingly lower-grade. New silver mines aren’t coming online fast enough to meet growing industrial demand, so deficits get filled the only way they can—by drawing down above-ground inventories.

For mining investors, this is where the unglamorous metrics matter. The key one is all-in sustaining cost, or AISC: the best attempt at “what it really costs” to keep a mine producing, including the ongoing capital needed to sustain operations.

Hecla’s best demonstration of why this matters is Greens Creek. It’s one of the largest and lowest-cost primary silver mines in the world, and it’s been the company’s cash engine. In 2024, Greens Creek produced 8.5 million ounces of silver at an all-in sustaining cost, after by-product credits, per silver ounce of $5.65.

What makes that number so powerful isn’t just that it’s low. It’s how it stays low. Greens Creek is polymetallic: it produces zinc, lead, and gold alongside silver. When those byproducts are strong, their revenue effectively subsidizes silver production, cushioning the business when silver prices weaken and supercharging margins when silver rallies.

That sets up the core silver debate.

The bull case is structural. Industrial demand keeps climbing, supply remains constrained by permitting and underinvestment, inflation or macro stress revives monetary demand, and genuinely high-quality production assets become more valuable because there aren’t many of them. In that world, being the dominant North American silver producer is a great seat to have.

The bear case is real too. Some applications may find substitutes over time. Recycling could improve, adding more secondary supply. Deflationary technology shifts could reduce the “monetary metal” bid. And crypto has absorbed some of the investor flows that once went straight to gold and silver.

So the long-term question for Hecla isn’t “Will silver go up next year?” It’s whether low-cost, byproduct-supported production, long-lived assets, and a conservative balance sheet can compound through full commodity cycles. In a business this volatile, history suggests survival and discipline matter more than perfect timing.

IX. Business Model Deep Dive: How Mining Companies Actually Make Money

Mining isn’t like most businesses. It’s a business where your inventory is buried in the ground, and every ounce you sell today is one less you’ll ever be able to sell tomorrow. That’s what it means to be a depleting-asset industry. The lifecycle is long and unforgiving—exploration, development, production, and then reclamation—and it demands steady investment for decades with no guarantee that any single project will ever work economically.

That’s why so many mining companies, over time, end up destroying shareholder value. The upfront capital is enormous. Exploration usually doesn’t hit. Development budgets slip. Commodity prices swing hard enough to turn a good mine into a bad one overnight. And the liabilities don’t end when the last truck leaves; environmental and closure obligations can linger for years.

So why has Hecla managed to keep compounding through cycles that wipe out most of its peers?

First, it owns genuinely rare assets. Greens Creek, tucked inside Alaska’s Tongass National Forest, is one of the world’s highest-grade and lowest-cost primary silver mines—and it produces nearly 30% of all U.S.-mined silver. Mines like that are scarce for a reason. High-grade ore, workable metallurgy, and meaningful byproduct credits don’t show up on command. They’re discovered slowly, proven carefully, and permitted over years. And once you have a deposit like that up and running, competitors can’t simply copy it.

Second, Hecla learned the right lesson from 2008 to 2013: in a cyclical commodity business, the balance sheet is part of the product. In 2024, the company reported record adjusted EBITDA of $337.9 million, continued to deleverage, reduced net debt, and improved its net leverage ratio to 1.6x from 2.7x a year earlier. That discipline gives Hecla options—room to keep investing when prices fall, and the ability to buy or build when weaker players are forced to retreat.

Third, it treats exploration and reserve replacement as a core operating requirement, not a nice-to-have. A mine that isn’t replacing reserves is a mine with a countdown timer. Hecla said it fully replaced silver production from reserves through strategic reserve replacement across operations. As President and CEO Rob Krcmarov put it: “Hecla’s silver reserves stand at 240 million ounces, the second-highest level in our 134-year history and only 1 million ounces below our peak in 2022.”

And then there’s a quieter advantage that shows up in the numbers when markets get ugly: Hecla’s polymetallic mix. At Greens Creek, silver is the headline, but gold, zinc, and lead matter just as much. When silver prices soften, those metals can provide a revenue floor. When silver rallies, the same structure can make profitability snap upward faster than it would at a pure-play silver mine. It’s diversification inside the ore body itself—and it’s one reason Greens Creek has been such a stabilizing force for the entire company.

Finally, there’s the question mining investors always ask: why pay any dividend at all, and how do you decide what’s sustainable? Hecla revised its dividend policy by keeping its base cash dividend while eliminating the silver-linked component, prioritizing strategic growth opportunities. The logic is simple: miners can’t “scale” the way software companies do. If you stop investing in development, equipment, and exploration, production eventually declines. In mining, capital allocation isn’t a finance function—it’s survival. Returning cash to shareholders matters, but only if you’re also reinvesting enough to keep the business alive.

X. Strategic Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

If you step back from the drama of strikes, floods, and silver prices, Hecla is still a business competing in an industry with its own hard rules. Two frameworks help make those rules visible: Porter’s 5 Forces and Hamilton’s 7 Powers. Mining is an odd fit for both—because it’s not a brand business or a platform business—but that’s exactly why they’re useful here. They highlight what matters, and what doesn’t.

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: Very Low. The “startup path” in mining is brutal. First you have to find an ore body that’s not just real, but economic—geology doesn’t care about your pitch deck. Then you have to permit it, which in developed countries can take a decade or more. Then you have to finance it, often with enormous capital requirements and lenders who demand credibility. From discovery to production, you’re often looking at a timeline measured in decades. The result is a very real moat around permitted, operating mines.

Supplier Power: Moderate. The equipment is specialized and the supplier base is relatively concentrated—think Caterpillar, Sandvik, Komatsu. And skilled labor, especially for underground work in remote places, is increasingly scarce. Still, these are global supply chains with alternatives, which keeps any one supplier from holding the whole industry hostage.

Buyer Power: Low. Hecla doesn’t negotiate the price of silver. Nobody does. Metals sell into global commodity markets with transparent pricing; producers are price takers, not price makers. The “customer conversation” is mostly about treatment and refining charges, not the metal price itself.

Threat of Substitutes: Moderate to High. On the industrial side, silver constantly faces substitution pressure—engineers will always look for cheaper materials if performance can be preserved. On the investment side, it competes for attention and capital with other stores of value, including cryptocurrency and other alternative assets. This doesn’t kill the business, but it’s a real long-term force acting against runaway pricing power.

Competitive Rivalry: High. Mining is fragmented, and the product is undifferentiated. An ounce of silver is an ounce of silver. That means competition shows up in one place: cost and execution. The winners aren’t the ones with the best marketing—they’re the ones who can produce safely, consistently, and cheaply through a full cycle.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework:

Scale Economies: Limited at the mine level—each operation has an optimal throughput, and pushing beyond it can raise costs and complexity. But Hecla can still benefit from scale in corporate overhead, shared technical expertise across sites, and access to capital markets.

Network Effects: Not applicable. There’s no flywheel where more users create more value. This is rock, not software.

Counter-Positioning: Not really applicable. Most miners use broadly similar operating models; there’s no obvious “new model” incumbents can’t copy.

Switching Costs: Not applicable on the sales side, since metals are commodities. On the supply side, there can be moderate switching costs because specialized contractors build mine-specific knowledge and routines over time.

Branding: Minimal. Responsible sourcing can matter at the margin in certain markets, but silver largely trades as a commodity.

Cornered Resource: THIS IS THE KEY POWER. Greens Creek’s ore body, Lucky Friday’s deep reserves, and Keno Hill’s historic district are not assets a competitor can manufacture. They’re geology, plus decades of permitting work, plus the hard-won ability to operate. When it can take 15–20 years to bring a new mine into production, an existing, permitted, community-accepted mine isn’t just valuable—it’s defensible.

Process Power: Moderate. Hecla has genuine operating know-how, including proprietary methods like the Underhand Closed Bench (UCB) technique at Lucky Friday. The company received the 2022 Robert E. Murray Innovation Award for pioneering UCB and has a U.S. patent for the method. These kinds of innovations can improve safety and productivity, but in a world of shared engineers and best practices, they’re not an unbreachable moat by themselves.

The Verdict: Hecla’s advantage isn’t that it’s smarter than every other miner. It’s that it owns the right rocks, in stable jurisdictions, with permits and relationships that take years—sometimes decades—to build. In mining, that combination is the closest thing there is to a durable competitive advantage.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Framework

The Bull Case:

The bull case for Hecla starts with the metal itself. Silver’s demand story has become more structural than cyclical: solar installations, electric vehicles, and electronics keep pulling more silver into the real economy. Hecla has leaned into that narrative, arguing that “with the world’s increasing demand for silver for clean energy, Hecla is helping meet that demand as the world’s fastest growing established silver miner.”

Then there’s the company’s seat at the table. Hecla is the largest silver producer in the United States—mining nearly half of all U.S. silver—and it also has a major footprint in Canada. That scale matters, not because it creates pricing power, but because it concentrates the company’s production in jurisdictions where the rule of law is strong and operating rights are more durable.

The asset base supports the story. Hecla’s portfolio includes long-lived mines and operations that have been running for decades—exactly the kind of “already permitted, already operating” footprint that becomes more valuable as new mines get harder to build. And it’s not just longevity; it’s also cost position. Hecla points to being one of the lowest-cost U.S. silver producers, with margins exceeding 50%, helped by byproduct credits at operations like Greens Creek.

Layer on growth, and the pitch gets clearer: over a five-year period, Hecla reported a 25% increase in silver reserves, a 38% rise in production, and 27% revenue growth.

Finally, the financial foundation looks nothing like the crisis years. In 2024, Hecla posted record adjusted EBITDA of $337.9 million, kept deleveraging, reduced net debt, and improved its net leverage ratio to 1.6x from 2.7x the year before. Cash flow from operating activities rose to $218.3 million, up $142.8 million from 2023.

And sitting off to the side are the “free options”: Rock Creek and Montanore. If the permitting and political environment ever turns more favorable—or if domestic supply chains become a national priority in a way that changes what gets approved—those projects could unlock meaningful value that isn’t reflected in today’s business.

The Bear Case:

The bear case starts with the brutal truth of mining: Hecla doesn’t set prices. It’s a commodity price taker. When silver prices fall, margins compress no matter how well the mines are run. You can’t “out-execute” a metals downturn forever.

Next comes the capital intensity problem. Mining eats capital just to stand still—development, exploration, equipment, and sustaining projects. That means EBITDA doesn’t reliably translate into proportional cash returns for shareholders. In 2024, free cash flow was negative $64.8 million, in line with the prior year. (This was at Keno Hill specifically during ramp-up.)

Permitting risk is the other existential variable. Rock Creek and Montanore may hold enormous potential, but “potential” doesn’t pay the bills if regulatory and social opposition prevents construction. Those assets can sit for years—effectively stranded—no matter how good the rocks are.

Then there’s grade decline, the slow-motion headwind every mine faces. Over time, the easiest, highest-grade material gets mined first, and what’s left often costs more to extract and process. Exploration can offset that, but it’s a constant race against depletion.

And the long tail of ESG and closure costs keeps getting longer. Bonding requirements, reclamation obligations, and the possibility of future carbon-related regulations all add real liabilities—some visible today, some only showing up later.

Key Performance Indicators to Track:

For investors following Hecla, two metrics matter more than all others:

-

All-In Sustaining Cost (AISC) per Silver Ounce: This is the closest thing mining has to a true profitability yardstick. If AISC stays well below silver prices, the company has room to reinvest, ride out downturns, and potentially return capital. The gap between AISC and the silver price is the buffer that keeps a miner alive when the cycle turns.

-

Reserve Replacement Ratio: Mining is a depleting business. If reserves aren’t being replaced through exploration and development, the company is slowly shrinking—no matter what the income statement says. Hecla’s recent record has been solid, though not perfect: in 2024, the company mined 18.7 million ounces of silver and replaced 14.6 million ounces in reserves. The shortfall primarily reflected production from areas outside of reserve blocks.

XII. Epilogue: The Future of American Mining

The strategic minerals question has moved from a niche policy debate to the center of American economic planning. COVID-era supply chain shocks, plus rising geopolitical tension with China, reminded everyone how fragile “just import it” can be. Suddenly the conversation isn’t academic anymore. It’s about whether the U.S. can reliably source the materials that power modern life and national defense—silver, antimony, cobalt, rare earths, and the rest of the periodic table we now depend on.

Hecla sits squarely in the middle of that story. Founded in 1891 and trading as NYSE:HL, it’s the largest silver producer in the United States and Canada. And it’s not only a silver company. Along the way it also produces lead and zinc—metals that show up everywhere from batteries and electronics to industrial systems that don’t get headlines until they break.

But the big constraint on the future isn’t geology. It’s permission.

The permitting reality in America is still the paradox we’ve been circling all episode: the country says it wants domestic minerals, and then it fights almost every new mine through years—sometimes decades—of reviews, litigation, and political opposition. For Hecla, that contradiction cuts two ways. It’s a risk because development projects can sit in limbo indefinitely. And it’s an opportunity because existing, permitted operations become more valuable when new competitors can’t get built.

There’s also a human transition underway. After nearly 23 years leading the company, Phil Baker stepped down in 2024. The baton passed to Rob Krcmarov, Hecla’s President and CEO, who has been out front discussing operating results and the company’s direction—including in interviews from the New York Stock Exchange.

At the same time, the way mining gets done keeps changing. Automation, AI-assisted exploration targeting, drone surveying, and improved processing techniques are steadily pushing the frontier on safety and productivity. At Lucky Friday, Hecla said the implementation of automated drilling increased ore extraction rates by 22% since 2022—exactly the kind of operational gain that matters in a business where margins can swing with the metal price.

Climate is now part of the operating equation too, not just in how mines are regulated but in what customers and markets increasingly expect. Greens Creek’s connection to Alaska’s hydropower grid gives it a lower-carbon power source than many peers—an advantage as carbon costs rise and demand grows for materials produced with a smaller footprint.

All of that points to the question that hangs over every mining company, regardless of the cycle: can you earn your cost of capital over a full commodity cycle? Mining history is crowded with businesses that didn’t—companies that bought at the top, levered up at the wrong time, or poured money into projects that never made it to production.

Hecla’s longevity is notable precisely because survival is rare. And the lessons embedded in that survival are surprisingly consistent. Conservative balance sheet management matters more than aggressive growth. Quality assets in stable jurisdictions beat higher-grade rocks in riskier places. Community relationships are long-term investments, not PR exercises. And patience—the willingness to endure multi-year downturns and decade-long development timelines—may be the most underrated edge in a capital-intensive industry.

Baker himself boiled Hecla’s resilience down to commitment and great assets with long mine lives and low costs. As he put it: “Commitment has resulted in continuity in management, board and employees, and long-tenured leaders have given Hecla a sense of direction, continuity and perspective that you can't create when there is high turnover of leaders.”

As Hecla moves into its 135th year, the core business model is still the same one it started with in 1891: find valuable minerals underground and bring them to the surface more efficiently than the next operator. The tools have evolved—from hand steel and candlelight to automated drills and data-driven targeting—but the requirements haven’t. You still need geological luck, operational excellence, financial discipline, and the stomach to wait for the cycle to turn.

For long-term investors, Hecla is ultimately a bet on the enduring value of hard assets, the growing role of silver in clean energy and industrial demand, and the company’s ability to keep executing in a business that never stops trying to humble you. After 134 years of proof, it’s at least a bet worth taking seriously.

XIII. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Long-Form Resources:

-

Hecla Mining Annual Reports (especially 2013–2024): The most direct record of the modern turnaround—strategy shifts, operational changes, reserve updates, and the details that don’t make headlines.

-

"The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power" by Daniel Yergin: It’s oil, not mining, but the lessons transfer cleanly: commodity cycles, geopolitics, capital discipline, and how entire industries get reshaped by forces outside their control.

-

"Liar's Poker" by Michael Lewis: A fast, human look at how markets actually behave. Helpful context for understanding why commodity prices can swing harder than fundamentals seem to justify.

-

"The Alchemy of Finance" by George Soros: A strong primer on reflexivity—how beliefs, narratives, and capital flows can become self-reinforcing and move prices in ways that then change real-world outcomes.

-

"Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk" by Peter Bernstein: A classic on probability, uncertainty, and the reality that “risk” isn’t just volatility—especially in capital-intensive businesses where one mistake can echo for decades.

-

Academic papers on the Coeur d'Alene mining district and Superfund cleanup: For the long, complicated history behind the environmental liabilities. The Idaho State Historical Society and EPA archives are deep and well-documented.

-

Alaska Journal of Commerce archives on Greens Creek: Local reporting that captures what matters on the ground: operations, employment, and how community relationships are built (or strained) over time.

-

Mining Engineering Journal case studies on polymetallic ore processing: For the technical layer—how metallurgy, byproduct credits, and processing complexity shape costs and long-term mine performance.

-

World Silver Survey (annual publication by Silver Institute): The reference source for silver supply, demand, and market structure—useful for separating enduring trends from short-term noise.

-

"Big Trouble" by J. Anthony Lukas: The definitive narrative account of the Coeur d'Alene labor wars—essential background for understanding how mining in this district became synonymous with both wealth and conflict.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music