Halozyme Therapeutics: The Enzyme That Changed Drug Delivery

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

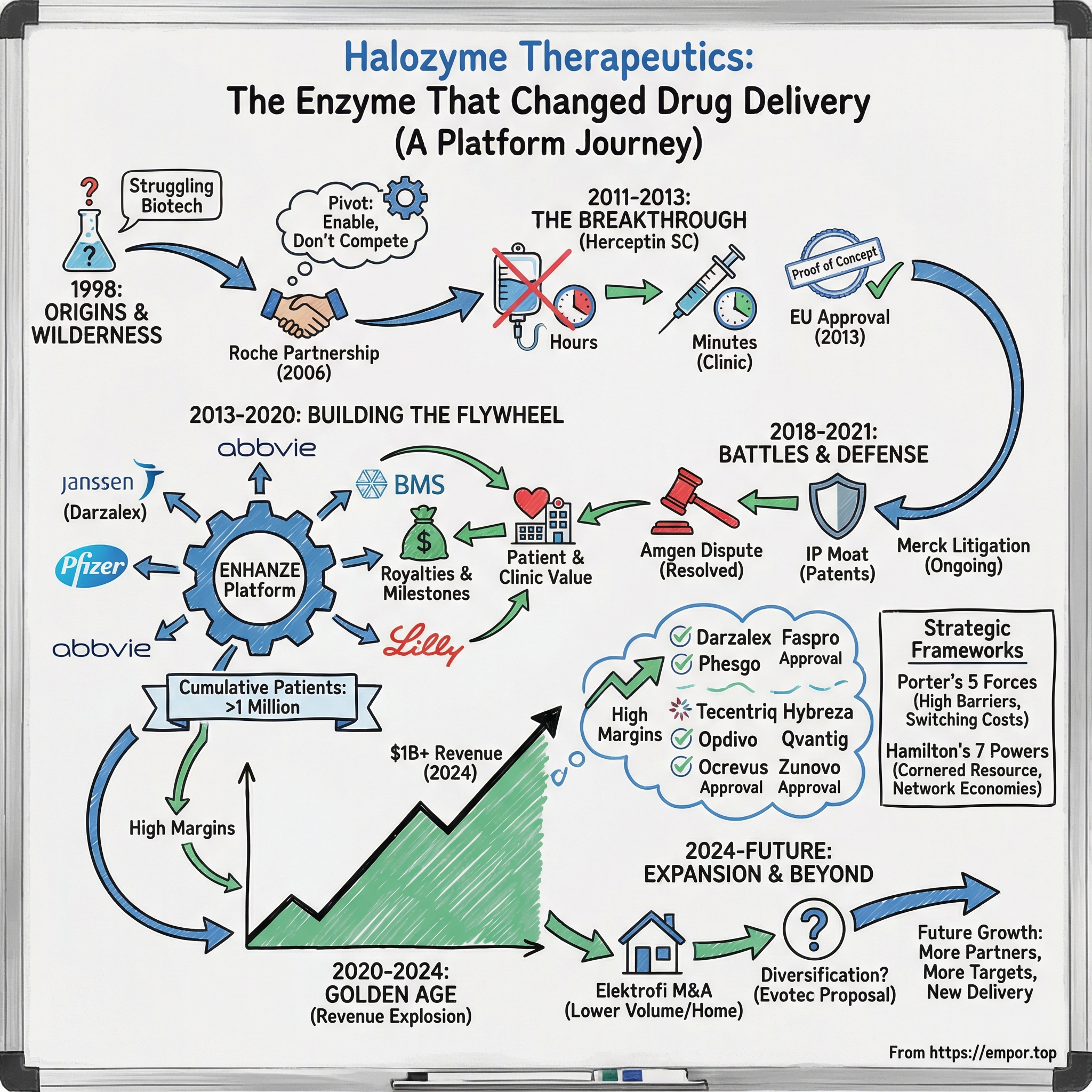

Picture a cancer patient in 2010, settled into a recliner at an infusion center, watching an IV drip inch along. Fluorescent lights hum overhead. Other patients sit in rows beside her, each tethered to a pole and a plastic bag of life-saving medicine. For many, these sessions ran an hour, sometimes longer—and they came back again and again, every few weeks, for months or years. The drugs could be miraculous. The experience was exhausting.

Now cut to 2024. That same treatment can look like a quick clinic visit: a five-minute injection, a short wait, and you’re back out the door before your coffee gets cold.

That shift—from long IV infusions to fast subcutaneous shots—has been one of the quiet revolutions of modern medicine. And behind a surprising amount of it sits a company most people have never heard of: Halozyme Therapeutics.

Halozyme was founded in 1998, nearly went bankrupt multiple times, and then—almost improbably—became a platform business embedded inside some of the biggest drugs in the world. In 2024, the company generated $1.015 billion in revenue (up 22.44% from 2023) and sat at roughly an $8 billion market cap. Its ENHANZE drug delivery technology has been licensed by a roster that reads like the industry’s roll call: Roche, Takeda, Pfizer, Janssen, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, argenx, ViiV Healthcare, Chugai Pharmaceutical, and Acumen Pharmaceuticals.

The central mystery here is almost funny in its simplicity: how did a pancreatic enzyme—something you’d associate more with digestion than with oncology—turn into the cornerstone of a multibillion-dollar platform?

And how did a company that struggled for years become something closer to pharmaceutical infrastructure, with ENHANZE touching more than one million patient lives?

This is a picks-and-shovels story in biotech. While pharma giants spend billions inventing blockbuster drugs, Halozyme built the tool that helps deliver them in a way that’s more convenient for patients, easier on clinics, and often more valuable for the drug makers. Halozyme doesn’t make the drugs. It makes the drugs better.

Here’s where we’re going: first, the science—what ENHANZE is, and why it works. Then the wilderness years, when Halozyme tried (and failed) to be a traditional drug company. Then the breakthrough partnership with Roche that proved the platform was real. From there, the flywheel: deal after deal, product after product. And at the peak of it all, a legal battle with Amgen that threatened the entire business model.

Along the way, we’ll pull the story apart with the strategic frameworks that explain why this company—of all companies—ended up with such a durable advantage. It’s a masterclass in platform economics, strategic patience, and the art of becoming indispensable.

II. The Science Foundation: Understanding ENHANZE

To understand Halozyme, you first have to understand a molecule most people never think about: hyaluronic acid.

It’s everywhere in the body—in skin, eyes, joints—where it acts like a natural cushion and lubricant. But just under the skin, it does something else: it helps create a dense, gel-like mesh that makes it surprisingly hard to push fluid through tissue. That mesh is a big reason so many modern medicines can’t be delivered as a simple shot.

A helpful way to picture it is rush-hour traffic. Try to inject too much liquid under the skin, and the hyaluronic acid network turns the space into a jam. The fluid pools, swelling and discomfort follow, and absorption into the bloodstream becomes slow and unpredictable. That’s why so many biologic drugs—large, complex molecules like monoclonal antibodies used in cancer and autoimmune disease—have historically defaulted to IV infusion. It’s the reliable way to deliver the volumes those therapies often require.

Halozyme’s breakthrough was engineering an enzyme that temporarily clears the traffic.

The company developed a recombinant human hyaluronidase PH20 enzyme, known as rHuPH20, that breaks down hyaluronan—the key component of that gel-like barrier. The elegant part is that this isn’t an unnatural hack. Hyaluronan is constantly being broken down and rebuilt as part of normal biology, with an estimated daily turnover of about a third. So rHuPH20 works locally and transiently: it opens a pathway, the drug disperses and absorbs, and then the body restores the barrier within roughly 24 to 48 hours. No permanent tissue remodeling. No lasting systemic effect.

In practical terms, rHuPH20 depolymerizes hyaluronan in the extracellular matrix, enabling higher-volume subcutaneous delivery—on the order of a few milliliters up to much larger volumes—and turning what used to be hours in an infusion chair into minutes in a clinic room.

That difference can be dramatic. With Herceptin SC, administration drops from around 30 minutes for IV Herceptin to about 5 minutes. For Rituxan Hycela (also known as MabThera SC), administration falls from roughly 3 to 4 hours down to about 5 to 7 minutes.

The patient experience is the obvious win. But the system-level impact is just as important. IV infusion isn’t just “the drug.” It’s an infusion chair, nursing time, pharmacy prep, monitoring, and facility overhead. A subcutaneous injection can be done quickly, which frees capacity for other patients and reduces staffing strain. And for infusion centers operating at or near capacity—as oncology volumes rise—moving even a portion of treatments from IV to subcutaneous can meaningfully increase throughput.

Hyaluronidases themselves weren’t new; they’d been used since the 1940s to increase the absorption and dispersion of injected drugs and fluids. What made Halozyme’s version different was the recombinant human part. Instead of being extracted from animal tissue (often bovine testes), rHuPH20 is produced through biotechnology, which reduces the allergenicity and immunogenicity issues associated with animal-derived hyaluronidases and yields a cleaner, more consistent, more manufacturable product.

This is the picks-and-shovels strategy in its purest form. By co-administering rHuPH20 with a partner’s therapy, Halozyme helps overcome the volume and time constraints that make subcutaneous dosing difficult in the first place—reducing the burden on patients and healthcare providers compared to IV formulations. Halozyme doesn’t invent the blockbusters—the Herceptins, the Darzalexes, the Opdivos. It provides the enabling technology that makes those drugs easier to give, more convenient to receive, and often more valuable to the companies that sell them.

And the therapeutic areas where this matters most—oncology, immunology, and rare disease—are exactly where biologics dominate and IV infusion has long been standard. As biologics became one of the fastest-growing segments of drug development, Halozyme quietly positioned itself at a critical chokepoint in how those medicines get delivered.

III. Origins & The Wilderness Years (1998-2011)

In 1998, biotech was on a roll. Antibody drugs were starting to hit, genomics was booming, and San Diego was turning into a magnet for life-sciences startups. Halozyme was born in that moment—but the company it would eventually become was still a long way off.

Halozyme Therapeutics was founded in 1998 by Gregory I. Frost. It initially operated as DeliaTroph Pharmaceuticals, then renamed itself Halozyme in 2001. Frost came out of the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Research Center in La Jolla, and the company went public in 2004.

What followed wasn’t a clean march toward a product. It was a scramble.

In those early years, Halozyme’s enzyme technology was explored for an almost comical spread of applications: helping prepare eggs for in-vitro fertilization procedures, improving uptake of anesthetics during cardiac surgery, and even trying to reverse chemotherapy resistance in cancer patients. At the same time, the company chased aesthetic uses, animal health products, and insulin delivery improvements. It was the classic early-biotech pattern: a powerful tool, no obvious business model, and a constant race against the bank account.

And the bank account mattered. By traditional biotech standards, Halozyme had burned only $8 million since February 1998. But “only” doesn’t help if you can’t raise the next dollar. In the summer of 2003, with cash running low and investors hard to persuade, Lim and Frost took no salaries to avert layoffs. That wasn’t vision. That was survival.

That same year brought the leadership change that ultimately set everything up.

Dr. Jonathan E. Lim became President and Chief Executive Officer in May 2003, joined the board in October 2003, and later became Chairman in April 2004. Before Halozyme, he’d been a management consultant at McKinsey & Company focused on health care. Before that, he held an NIH postdoctoral fellowship doing clinical outcomes research at Harvard Medical School, and earlier still, he trained clinically in general surgery at New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

In other words: physician, scientist, strategist. Not a common combination.

Lim’s key contribution wasn’t a lab breakthrough. It was a reframing. Instead of trying to out-invent pharma giants with proprietary drugs, Halozyme could do something much more defensible: enable the drugs they already had. Big Pharma owned blockbuster biologics that were effective but burdensome to administer. Halozyme’s enzyme could make those same drugs easier to deliver. Rather than compete with the giants, it could become a piece of infrastructure they needed.

The first real signal that this idea could work came from Roche. In 2006, the Swiss pharmaceutical giant licensed Halozyme’s technology for potential use with its oncology franchise. The deal economics were modest by pharma standards, but strategically it was huge: a top-tier player had looked at Halozyme’s platform and said, “Yes, this matters.” Then in 2009, Roche expanded the collaboration and began serious development work on a subcutaneous version of Herceptin, its blockbuster breast cancer therapy.

Lim served as President, CEO, and Chairman—and later Director—of Halozyme from May 2003 through December 2010. By the time he left, Halozyme had finally stopped trying to be everything at once. The company was no longer a chaotic collection of enzyme experiments. It was becoming a platform business with a real anchor partner.

But the payoff still wasn’t here. The years ahead were tense: cash constraints, slow clinical timelines, and the ever-present doubt that hangs over any enabling technology. Would it work at commercial scale? Would physicians and patients actually prefer subcutaneous delivery? Would the economics be compelling enough for more partners to follow?

Helen Torley would become Chief Executive Officer and President in January 2014, ushering in a new chapter. But before Halozyme could enjoy any “platform flywheel,” it needed Roche to do the one thing that would silence the skeptics: deliver proof of concept in the real world.

IV. The Roche Breakthrough: Herceptin SC & Proof of Concept (2011-2013)

By 2010, Herceptin was already an icon in oncology: a monoclonal antibody that had reshaped outcomes for HER2-positive breast cancer and become a multibillion-dollar franchise for Roche and Genentech. But the way patients got it still looked like old-school cancer care—IV infusions every three weeks, often lasting 30 to 90 minutes, repeating for months and sometimes years.

Halozyme and Roche were chasing a deceptively simple question: could you take one of the world’s most important biologics and turn it into a quick shot—without giving up efficacy?

That question landed in the HannaH trial (enHANced treatment with NeoAdjuvant Herceptin). The study enrolled 596 patients with HER2-positive operable or locally advanced breast cancer and randomized them to receive trastuzumab either subcutaneously or intravenously, alongside chemotherapy. This was the moment of truth for ENHANZE in a major oncology setting: would a roughly five-minute injection match what the IV drip had proven over years?

It did. The results showed trastuzumab/hyaluronidase was comparable to IV trastuzumab on the co-primary endpoints of pharmacokinetics and pathologic complete response. The pCR rate came in at 45.4% with Herceptin SC versus 40.7% for the IV arm—evidence of non-inferior clinical efficacy. In plain terms: under the skin worked just as well.

In August 2013, trastuzumab/hyaluronidase (Herceptin SC) was approved for medical use in the European Union. For Halozyme, this wasn’t just “a product approval.” It was platform proof—one of the first major oncology drugs approved for subcutaneous delivery using its technology.

Then came the part that turned a scientific win into a commercial story: patients didn’t just accept the shot. They wanted it.

In the PrefHER patient-preference trial, 86% of patients preferred the subcutaneous regimen versus standard IV trastuzumab (13%), with 1% reporting no preference. The most common reason was exactly what you’d expect: time saved.

And the time difference was real. Subcutaneous trastuzumab is given as a fixed 600 mg dose in a total volume of 5 ml, with no loading dose, administered over up to five minutes. IV trastuzumab, by contrast, takes about 90 minutes for the initial infusion and around 30 minutes for subsequent doses—before you even count the rest of the infusion-center choreography.

This single approval quietly confirmed multiple things at once. The biology worked in the biggest leagues. A pharma giant could shepherd the combo through regulators. And when patients were offered the choice, the market signal was overwhelming.

Herceptin SC was first approved in Europe in 2013 and later expanded to approval in 100 countries worldwide. The U.S. approval arrived years later, in February 2019, reflecting the longer regulatory path in the United States.

But the real ripple effect went far beyond Herceptin. Every pharma team with an IV biologic watched this play out and saw the same opportunity: take an already effective drug, make it dramatically easier to administer, and potentially strengthen its competitive position.

That’s why this moment mattered so much to Halozyme. In a traditional biotech, one approval is one shot on goal. For a platform company, one approval de-risks everything that comes after it.

The flywheel was starting to move.

V. Building the Platform Flywheel (2013-2017)

With Herceptin SC approved in Europe and the data in hand, Halozyme’s pivot stopped being a theory and became a machine. This wasn’t a one-off license anymore. It was the beginnings of a repeatable platform: partners plug in their IV biologic, ENHANZE makes subcutaneous delivery possible, and Halozyme gets paid as the program moves from lab bench to patients.

The deal that really showed the blueprint came in December 2014, when Halozyme signed a worldwide Collaboration and License Agreement with Janssen Biotech to develop and commercialize products combining Janssen compounds with ENHANZE. Halozyme received a $15 million upfront payment, could earn development, regulatory, and sales-based milestones totaling up to $566 million, and would collect royalties on net sales of any resulting products.

That structure mattered as much as the partner name. Upfront cash helped keep Halozyme funded without constant trips back to the equity markets. Milestones meant Halozyme got rewarded as programs advanced. And royalties were the long game: a durable stream that could compound as more products reached the market.

One of the earliest and most important targets under that Janssen umbrella was daratumumab. In March 2015, Halozyme reported that Genmab announced plans for a Phase 1 clinical trial of a subcutaneous formulation of the anti-CD38 antibody daratumumab using ENHANZE—made possible because Janssen had already teamed up with Halozyme for this purpose.

Daratumumab became Darzalex, a multiple myeloma therapy that would grow into one of Halozyme’s defining wins. The subcutaneous product, DARZALEX FASPRO, is co-formulated with recombinant human hyaluronidase PH20—Halozyme’s ENHANZE drug delivery technology. DARZALEX was first approved by the U.S. FDA in November 2015, and it is now approved in ten indications.

While Janssen was the headline, it wasn’t the only signal. Over this period, Halozyme kept stacking partnerships with major pharmaceutical players—names like Roche, Pfizer, Janssen, and Baxter—each one another vote of confidence that ENHANZE wasn’t limited to a single drug or a single company’s development philosophy. The platform was proving portable: different molecules, different diseases, different clinical teams, same basic delivery unlock.

And here’s what made the business model so powerful: Halozyme didn’t have to bet the company on a single drug’s clinical outcome. Its partners ran the trials, dealt with regulators, and built the commercial engines. Halozyme supplied the enabling technology and, if the partner succeeded, earned royalties. It was picks-and-shovels economics applied to biologics, with much of the cost and execution risk sitting on the other side of the table.

For partners, the incentives were obvious. A subcutaneous formulation could be a competitive weapon: differentiation versus rival drugs, new formulation-based intellectual property, and a better experience for patients and clinics. When a therapy is already a blockbuster, shaving administration time down to minutes isn’t a nice-to-have—it can influence prescribing, expand capacity in infusion centers, and help defend a franchise.

By the end of this stretch, Halozyme had licensed ENHANZE to a growing roster of leading pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, including Roche, Baxalta, Pfizer, Janssen, AbbVie, Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Alexion, and argenx.

Underneath the deal-making was another critical ingredient: manufacturing. Producing recombinant enzymes at pharmaceutical-grade consistency isn’t trivial. Halozyme had spent years building that capability—first for its own work, and then through supplying Roche—and that hard-won expertise became part of the moat. Even if someone else understood the science, matching the quality systems, reliability, and scale was a very different challenge.

By 2017, you could see the outline of something defensible taking shape. Patents protected the enzyme and its use across drug types. Each approval—whether Herceptin SC, Rituxan SC, or HyQvia—added credibility with regulators and partners. The manufacturing track record reduced perceived risk. And with every new partnership, the flywheel spun faster: more programs meant more data, more experience, and more leverage in the next negotiation.

The financial story was starting to change too. Halozyme still wasn’t “big” by Big Pharma standards, but the line was bending in the right direction. Milestones arrived as programs progressed, and early royalties began to show up. They were small at first—but they were proof that the annuity model worked, and that larger streams were sitting out in the future, waiting for more launches.

VI. The Amgen Crisis & Legal Battle (2018-2021)

In October 2018, Halozyme ran into the nightmare scenario for any platform company: a deep-pocketed rival decided it didn’t want to license the toll road—it wanted to build a competing one.

Amgen, one of the largest biotech companies in the world, announced it was developing its own hyaluronidase-based technology and publicly claimed it didn’t infringe Halozyme’s patents. The implication was clear. If a player like Amgen could route around ENHANZE, then maybe others could too. And if Halozyme’s patents weren’t enforceable, the whole royalty-driven model started to look a lot less durable.

For Halozyme, this wasn’t just competitive noise. It was an attack on the foundation.

So the company did the thing that separates “nice-to-have” technology from true infrastructure: it fought. Halozyme leaned hard on its intellectual property position and showed it was willing to litigate to defend it. The message to the market wasn’t subtle: if you want to use this approach, you can either partner—or you can go to court.

The outcome is what mattered most. By late 2020, Amgen wasn’t positioning itself as a workaround anymore. It had entered into a global agreement with Halozyme, originally signed on November 21, 2020—effectively moving from would-be competitor to licensee.

That resolution did something crucial for Halozyme’s credibility. It validated that the IP moat wasn’t just a stack of patents on paper; it was strong enough that a sophisticated, well-resourced company found it easier to make peace than to keep fighting. In other words: ENHANZE wasn’t just a clever trick. It was defensible territory.

That same instinct—to protect the chokepoint—didn’t end with Amgen. As subcutaneous delivery became more central to oncology, Halozyme kept treating intellectual property as a core operating asset, not a legal footnote.

You can see that posture in the more recent Merck dispute over a subcutaneous formulation of Keytruda. In April 2025, Halozyme filed a patent infringement lawsuit against Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. in U.S. District Court in New Jersey, alleging that Keytruda SC infringed multiple patents Halozyme filed beginning in 2011 covering its MDASE subcutaneous delivery technology.

The details underline how seriously Halozyme has taken this science. The patents at issue stem from a research effort that explored nearly 7,000 modifications to human hyaluronidases—less a single invention and more a sustained, industrial-scale optimization program. And Halozyme has been explicit about an important nuance: none of the MDASE patent rights it is seeking to enforce relate to its ENHANZE licensing program. These are distinct technology families.

In Germany, the fight escalated quickly. A court in Munich granted Halozyme a preliminary injunction and ordered Merck to halt distribution of Keytruda SC in Germany, finding imminent infringement of one of Halozyme’s MDASE patents in Europe.

Taken together, these legal battles reveal the double-edged reality of Halozyme’s position. Its intellectual property is valuable enough that major pharmaceutical companies will contest it. But that also means Halozyme has to keep spending time, money, and management attention enforcing it. ENHANZE sits outside the specific MDASE claims, but the broader lesson is the same: when you become the enabling layer for an industry, your moat isn’t just built in the lab. It’s defended in court, too.

VII. The Golden Age: Multiple Approvals & Revenue Explosion (2020-2024)

From 2020 through 2024, Halozyme finally got to live in the world it had been building toward for years. After more than a decade of slow, high-risk platform validation, multiple partner drugs hit their stride at the same time—and Halozyme’s business flipped from “interesting biotech story” into a true royalty engine.

Nothing illustrates that better than Darzalex.

J&J reported worldwide net trade sales of DARZALEX (daratumumab)—including the subcutaneous formulation, daratumumab and hyaluronidase-fihj, sold as DARZALEX FASPRO in the U.S.—of $11,670 million in 2024, with $6,588 million coming from the U.S. alone. Darzalex had already been a major myeloma drug after its 2015 approval. But the subcutaneous version, launched in 2020, changed the experience of receiving it. What used to take hours on an IV line could now be delivered in minutes.

A year earlier, J&J said that 85% of patients receiving Darzalex were using Faspro—the subcutaneous option. And that’s the compounding magic of ENHANZE: when a partner drug succeeds, Halozyme doesn’t need to sell harder or build a bigger salesforce. Its economics show up quietly, automatically, as royalties—earned on every dollar of net sales.

By 2024, the platform’s scale was undeniable. Halozyme crossed $1 billion in total revenue and reached a cumulative one million patients treated with medicines enabled by its ENHANZE drug delivery technology. Full-year 2024 revenue rose 22% year over year to $1,015 million, and royalty revenue grew even faster—up 27% to $571 million, above guidance.

The growth curve tells you what happened as multiple products matured at once. Annual revenue was $0.66 billion in 2022, $0.829 billion in 2023, and $1.015 billion in 2024. That’s not a one-product spike. That’s a platform stacking launches, expansions, and adoption—one after another.

In 2024, Halozyme said royalty revenue outperformance was driven by continued strength in DARZALEX SC and Phesgo, plus a modest initial contribution from VYVGART Hytrulo as adoption grew, primarily from its first indication in generalized myasthenia gravis.

And the approvals didn’t stop. Tecentriq Hybreza (Roche) received both FDA and EMA approvals in 2024 for all IV indications. Opdivo Qvantig (Bristol Myers Squibb) received FDA approval at the end of 2024. Ocrevus Zunovo (Roche) later secured a permanent U.S. J-code in April 2025, which was expected to help accelerate uptake. Roche anticipated an incremental $2 billion opportunity for the brand and projected $10 billion in combined IV and subcutaneous Ocrevus by 2028.

As revenues scaled, profitability followed. In 2024, net income increased 58% year over year to $444 million. GAAP EPS rose 63% to $3.43. Adjusted EBITDA climbed 48% to $632 million, and non-GAAP EPS increased 53% to $4.23.

With that kind of cash generation, Halozyme started behaving like a mature platform company, not a scrappy biotech. Capital allocation became part of the story: $303.5 million was deployed in Q2 2025 for share repurchases, bringing total repurchases to more than $1.85 billion since 2019.

And the outlook stayed bullish. Halozyme reiterated 2025 guidance for total revenue of $1,150 to $1,225 million (13% to 21% year-over-year growth) and adjusted EBITDA of $755 to $805 million (19% to 27% growth).

For investors, this stretch was the payoff. The model worked the way it was supposed to: high-margin royalties that scaled with partner success. Every additional approval—new indications, new geographies, new drugs—layered on more revenue without anything close to proportional cost. After years of waiting for “platform economics” to stop being a pitch deck phrase, Halozyme was living it.

VIII. Recent Inflection Points & Strategic Moves (2024-Present)

After the revenue breakout of 2020 through 2024, Halozyme didn’t shift into cruise control. Late 2024 and 2025 were about staying ahead—expanding what its platform could do, widening the set of drugs it could help, and continuing to defend the next wave of subcutaneous delivery in court.

The biggest swing was M&A. Halozyme agreed to acquire Elektrofi in a deal worth up to $900 million, bringing together two specialists in subcutaneous drug delivery. The structure was straightforward but meaningful: $750 million upfront, plus up to three $50 million milestone payments tied to different product approvals. The companies expected the transaction to close in the fourth quarter of 2025.

CEO Helen Torley framed it as a platform expansion, not a side bet. In an October 2025 statement, she said: "This acquisition marks a pivotal step in Halozyme's evolution. With Elektrofi's Hypercon technology, we are expanding and diversifying our drug delivery technology offerings to the biopharma industry and positioning Halozyme for continued long-term revenue growth through Elektrofi's licensing, royalty revenue business model."

The strategic fit is the key. ENHANZE has been used in 10 approved products and shines when you need to move a lot of drug volume under the skin—often in a physician’s office, and sometimes at home. Hypercon, by contrast, is aimed at lower-volume delivery and is designed to open up more products for home administration. Together, it’s less “replacement” and more “coverage”: Halozyme broadening the range of biologics it can help convert from IV to subcutaneous.

Electrofi also brought something investors care deeply about in platform businesses: time. Hypercon comes with a patent portfolio that runs into the 2040s, which directly addresses the long-running question of what happens as ENHANZE patents age out. In one move, Halozyme extended its patent runway and, with it, the credibility of its long-term royalty model.

At the same time, the partnership flywheel kept turning—especially with companies that had already seen ENHANZE work in the market. Argenx nominated four additional targets under its relationship with Halozyme, expanding exclusive access to ENHANZE. With those nominations, argenx now holds exclusive rights to use ENHANZE across six programs, including its approved FcRn blocker, VYVGART Hytrulo.

The economics were incremental, but the signal was loud. Under the expanded agreement, argenx paid $7.5 million per target nomination—$30 million total—and Halozyme may be eligible for future milestones of up to $85 million per nominated target, depending on development progress, regulatory approvals, and sales.

This is what switching costs look like in practice. Once a partner has built a regulatory path, manufacturing process, and clinical evidence around an ENHANZE-enabled formulation—and commercialized it successfully—the easiest next step is to do it again. Adding targets inside an existing relationship is faster and less risky than starting over with a new delivery technology.

Halozyme also explored an even larger strategic reshape. In November 2024, it updated investors on a non-binding proposal to acquire Evotec SE for €11.00 per share in cash, implying a fully diluted equity value of €2.0 billion.

Halozyme positioned the potential combination as a step toward a broader pharma services portfolio, with roughly $2 billion in annual revenue projected in 2025. The company said the deal would enhance its long-term growth profile, target a 15–20%+ 2023A–2028E revenue CAGR, and support a pro forma 45–50% adjusted EBITDA margin by 2026.

As of late 2024, the Evotec situation was still a conversation—not a conclusion—but it revealed the ambition. Management was clearly thinking beyond “drug delivery tolls” and toward diversification: reducing dependence on a concentrated set of royalty-driving partners while keeping the same capital-efficient, high-margin posture that made the platform so powerful in the first place.

As of December 2025, Halozyme’s trailing twelve-month revenue was $1.24 billion. As of October 2025, the company’s market cap was $8.06 billion.

IX. Strategic Frameworks: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

By this point in the story, Halozyme isn’t just “a biotech with good science.” It’s an enabling layer that sits inside other companies’ products. So to understand how durable this gets, you have to look at two things at once: the structure of the market it operates in, and the specific advantages it has built over time.

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: HIGH BARRIERS. In theory, anyone can decide they want a competing hyaluronidase platform. In practice, that means years of R&D, navigating an existing patent thicket, building regulatory confidence, scaling manufacturing to pharma-grade standards, and—hardest of all—convincing major drug companies to bet important assets on you. Halozyme’s own patents in litigation trace back to work that explored nearly 7,000 modifications to human hyaluronidases. That effort didn’t just produce a molecule; it produced a map of what changes matter for activity and stability. A would-be entrant doesn’t just need to “make an enzyme.” It has to catch up to decades of accumulated know-how, while also steering around the IP. The Alteogen example shows that alternatives can emerge—but also that doing so can invite serious legal and commercial risk.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW. Halozyme’s inputs are specialized, but not the kind that hand pricing power to a single upstream vendor. The company built internal manufacturing capabilities and has deep operational familiarity with its supply chain. That keeps supplier leverage contained.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE. Halozyme’s customers are pharma heavyweights—Roche, J&J, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer—teams that negotiate for a living and can push hard on terms. But once a partner commits to an ENHANZE-enabled product, the relationship changes. Clinical development, regulatory filings, manufacturing validation, labeling—those investments create real lock-in. The negotiation leverage is highest before a program starts and lowest after the product is approved and selling.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW to MODERATE. There are other ways to get drugs under the skin: microparticle approaches (one reason the Elektrofi acquisition matters), implantable pumps, alternative enzymes, and other formulation tricks. But ENHANZE has something substitutes struggle to match all at once: breadth across many drugs, a long regulatory track record, and proven commercial adoption. That said, the threat isn’t hypothetical. Alteogen’s ALT-B4 platform has secured partnerships with Merck, AstraZeneca, and Daiichi Sankyo, and Halozyme has been actively litigating to defend its position.

Competitive Rivalry: LOW. After the Amgen situation was resolved, Halozyme faced relatively little direct, head-to-head rivalry in hyaluronidase-enabled delivery. The bigger risk looks different: not a price war with one obvious rival, but the gradual normalization of an alternative platform—partners choosing non-Halozyme solutions for future programs. That’s the real competitive pressure point.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework:

Scale Economies: YES. Halozyme’s R&D, manufacturing investment, and regulatory experience get reused across deal after deal. The more programs it supports, the more those fixed costs spread out, and the cheaper—and faster—it becomes to execute the next one.

Network Economies: YES. Each additional partner adds data, precedents, operational learning, and credibility. That credibility attracts more partners, which generates more experience, which makes Halozyme even easier to say “yes” to. You can see it in practice when partners expand relationships instead of shopping around—like argenx moving from two targets to six.

Counter-Positioning: YES. For many pharma companies, building an internal subcutaneous delivery platform is possible, but it’s not what they’re optimized for. It’s expensive, slow, and risky—especially when they’re already sitting on valuable IV franchises. Licensing ENHANZE is often faster and lower-risk than building from scratch. Incumbents can’t easily copy the convenience advantage without partnering, licensing, or buying capability.

Switching Costs: STRONG. Once a product is approved using ENHANZE, switching to a different delivery technology isn’t a simple supplier change. It means reformulation work, new trials, new regulatory submissions, and the risk of disrupting a commercial product patients and physicians already rely on. That lock-in is what turns royalties into something closer to an annuity.

Branding: MODERATE. ENHANZE is well known where it matters most: inside pharma development organizations, where it’s often the default option for IV-to-subcutaneous conversion. Patients generally don’t walk into a clinic asking for ENHANZE by name, but awareness rises as more therapies show up as branded subcutaneous combinations. The brand is primarily B2B, and it’s strong in that lane.

Cornered Resource: STRONG. The core cornered resource is the IP portfolio. Halozyme’s ENHANZE technology is protected through at least 2027, with newer patents extending certain protections into the 2030s. But the moat isn’t only legal. Manufacturing consistency, regulatory familiarity, and institutional knowledge built across many approvals also function like scarce assets—hard to replicate quickly, even for well-funded competitors.

Process Power: YES. Halozyme has been running the same play enough times to get unusually good at it: enzyme development, formulation science, partner support, regulatory navigation, and supply reliability. Those processes are refined over decades, and they help partners move faster while avoiding mistakes that slow programs down.

Primary Moats: Cornered Resource (IP portfolio), Switching Costs (regulatory and commercial lock-in), and Network Economies (the partner flywheel).

X. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Considerations

The Bull Case:

Start with the thing that makes Halozyme unusual: it’s a biotech that doesn’t have to “win” with one drug. Its best economics come from being embedded across many drugs, with partners carrying most of the clinical, regulatory, and commercial load. In 2024, that model showed up clearly: revenue grew 22% and adjusted EBITDA grew 48%, with adjusted EBITDA margins above 60%. And the highest-margin piece of the whole machine—royalties—grew faster than total revenue.

The flywheel is also still spinning. ENHANZE has now reached more than one million patients through ten commercialized products in over 100 markets, and it’s licensed across a who’s-who list of pharma: Roche, Takeda, Pfizer, Janssen, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, argenx, ViiV Healthcare, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Acumen Pharmaceuticals, and Merus N.V. That matters because each additional partner program doesn’t just add potential revenue; it adds more proof points, more regulatory precedent, and more reasons the next partner says yes.

Even within the drugs already on the market, there’s still room to run. With Ocrevus, the strategy is to expand the market first and then convert IV sales to subcutaneous over time, with 80% of new starts already being new to brand. If that continues, it implies growth runway that doesn’t require a constant stream of fresh approvals to keep the story moving.

Then there’s the platform extension. The planned Elektrofi acquisition broadens Halozyme’s toolkit beyond ENHANZE. Hypercon targets lower-volume delivery and is aimed at opening up more products for home administration. Just as importantly for investors, it brings patents that run into the 2040s—helping address the question that has hovered over Halozyme for years: what happens as the original ENHANZE patent estate ages.

On Wall Street, the upside case often gets expressed in earnings power. Analysts have projected Halozyme’s EPS could reach $9.08 by 2028, driven by expanding margins and new ENHANZE-enabled launches.

And Halozyme has acted like a company that believes in its own durability. It has returned significant capital to shareholders, with total share repurchases exceeding $1.85 billion since 2019.

Finally, there’s optionality. Halozyme can keep being a disciplined platform licensor, but it can also use its cash flow to reshape the business. The non-binding interest in Evotec signaled that management sees a path toward diversification. Halozyme described Evotec as offering a large, diverse revenue base, potential revenue and margin expansion, a proprietary platform of technologies, and more than 500 biopharma partner relationships globally.

The Bear Case:

The first risk is concentration—because this is still a platform that gets paid based on other people’s winners. Darzalex, Phesgo, and a small handful of products drive the majority of royalty revenue. If J&J or Roche stumbles commercially, or if competing drugs take share, Halozyme takes the hit despite having little direct control.

Then there’s the clock. ENHANZE’s core patents begin expiring in 2027, with newer patents extending some protection into the 2030s. Elektrofi helps push the runway out, but it doesn’t eliminate the reality that older, already-commercialized products will eventually face a world with less exclusivity.

The legal backdrop adds uncertainty, too. In the Merck dispute, Wells Fargo analyst Mohit Bansal said the PTO decision to review the patent “likely reduces the probability” that Halozyme will prevail in its MDASE patent litigation. Halozyme has been clear that this is separate from ENHANZE, but a visible courtroom loss can still have second-order effects—especially if it encourages others to try non-Halozyme approaches.

And those alternatives are already showing up. AstraZeneca and Daiichi Sankyo are among the companies using Alteogen’s platform. If that technology proves both viable and legally durable, Halozyme could face pressure on pricing power and on its ability to remain the default choice for IV-to-subcutaneous conversion.

There’s also the longer-term technology risk: implantables, patches, nanoparticles, and other delivery formats could eventually compete with subcutaneous injection itself. Subcutaneous delivery is a huge improvement over IV, but it may not be the final form factor for convenience.

Finally, platform businesses carry platform risk. Any safety issue with rHuPH20 could ripple across multiple approved products at once, because the same enabling component is used again and again.

Key Metrics to Watch:

1. Royalty Revenue Growth Rate: This is the cleanest read-through on whether the platform is compounding. As launches stack and adoption curves mature, royalties should keep growing faster than the broader pharma market. If that growth materially slows, it can be an early warning of saturation or rising competitive pressure.

2. Partnership Expansion (Target Nominations and New Deals): Watch whether existing partners keep doubling down. Argenx expanding from two to six targets is the pattern you want to see. If expansions stall—or if new deals increasingly go to alternative platforms—that’s a signal the flywheel is losing torque.

3. Patent Litigation Outcomes: The Merck case and any future challenges to ENHANZE or MDASE-related patents matter because they shape the industry’s willingness to route around Halozyme. Wins reinforce the moat. Losses can change behavior, even if they don’t immediately change revenue.

XI. Epilogue & Reflections

The Halozyme story is one of biotech’s rare, clean transformation arcs: a company that started as a struggling would-be drug developer and ended up as an enabling layer for some of the biggest medicines on earth.

It began in 1998, founded by Gregory I. Frost. The company first operated as DeliaTroph Pharmaceuticals, then changed its name to Halozyme in 2001. In 2004, it went public on NASDAQ, raising about $18.6 million.

And then came the hard part.

This was the company that nearly failed multiple times. The one that avoided layoffs by paying no salaries. The one that pinballed between programs in aesthetics, diabetes, and animal health, trying to find a product that would stick. Yet over time, Halozyme evolved into something far more durable: a platform business generating more than $1 billion in annual revenue with operating margins above 60%.

So what actually made that possible?

Scientific insight that turned into a commercial wedge. Halozyme recognized that hyaluronic acid created a physical barrier to pushing large volumes of medicine under the skin—and then built a human enzyme solution to temporarily clear that barrier. The result wasn’t a single-disease breakthrough. It was a delivery unlock that could apply across entire categories of biologic drugs.

Strategic patience. Walking away from the traditional biotech dream—build a proprietary drug, swing for the fences—takes nerve. Halozyme chose a different kind of ambition: become infrastructure. Not the star of the show, but the thing the show can’t run without.

Execution excellence. Great science doesn’t automatically become a repeatable business. Halozyme had to prove regulators would accept the approach, that manufacturing could be done reliably at scale, and that partnerships with demanding pharma giants could be managed over years. Each approval wasn’t just revenue; it was credibility that made the next deal easier.

Leadership continuity. Since January 2014, Helen Torley has served as Chief Executive Officer and President. Her decade-plus tenure provided strategic steadiness as Halozyme shifted from “promising platform” to “platform powerhouse.” It also highlights a rare kind of leadership handoff in biotech: Jonathan Lim helped set the direction, and Torley drove the commercial buildout that turned that direction into a machine.

The lessons here go beyond one company.

Platform businesses in life sciences are possible. The picks-and-shovels model can work in biotech when the enabling technology is truly valuable and defensible. Halozyme demonstrated that you can build recurring, high-margin revenue streams—and something that starts to look like network effects—even in an industry famous for binary outcomes.

Patents matter, and they have to be defended. The disputes with Amgen and Merck show that intellectual property isn’t just paperwork. It can be a real competitive advantage, but only if you’re willing to enforce it when the stakes get high.

Patient timelines require patient capital. This journey took more than 25 years from founding to crossing $1 billion in revenue. That’s the reality of healthcare: clinical development, regulatory approval, and adoption curves move at human speed, not internet speed.

So what’s next?

Halozyme now faces the kind of strategic choices that only show up once you’ve made it. Continuing to build the drug delivery platform is a viable path. The proposed Evotec acquisition would represent a move toward diversification and a broader services footprint. And Halozyme itself could be the prize—an acquisition target for a pharmaceutical company that wants to control a strategic layer of modern biologics.

The ultimate question—stay independent or get acquired—will likely hinge on how well management navigates emerging competitive pressure from platforms like Alteogen, how effectively the Elektrofi acquisition extends the technology runway, and where the patent battles ultimately land.

But zoom out, and the punchline of the whole story stays simple: in biopharma, the delivery mechanism can be as valuable as the drug.

A humble enzyme that breaks down a naturally occurring molecule in the body—that’s what changed the experience of receiving blockbuster therapies. Halozyme didn’t cure cancer. It didn’t invent the revolution in biologics. It made other companies’ drugs easier to take, simpler to deliver, and more valuable to own. And in doing that, it built one of the most defensible and lucrative business models in biotechnology.

XII. Further Reading & Deep Dive Resources

Top 10 Long-Form Resources:

-

Halozyme SEC Filings (10-K, 10-Q, DEF 14A) - halozyme.com/investors

The primary source for how the business really works: partnership terms, royalty mechanics, risk factors, and the financial history behind the platform. -

"ENHANZE drug delivery technology: a novel approach to subcutaneous administration using recombinant human hyaluronidase PH20" - Drug Delivery Journal, 2019

A clear, science-forward explanation of the rHuPH20 mechanism, the safety profile, and how ENHANZE became clinically validated. -

BioPharma Dive: Halozyme Coverage Archive

A running narrative of the company in real time—deals, approvals, competitive shifts, and the industry context around subcutaneous delivery. -

Journal of Clinical Oncology: Herceptin SC & Darzalex SC Clinical Trials

The original clinical publications—especially the HannaH trial and the Darzalex programs—that put hard evidence behind the platform’s promise. -

Halozyme v. Merck Court Documents (PACER)

The legal record that shows what’s actually being argued: the scope of the patent claims, how competitors position their alternatives, and how Halozyme defends its IP. -

JPMorgan Healthcare Conference Presentations (2015-2025)

A decade-long trail of management’s strategy, told in their own words. Many are accessible through SEC filings, conference archives, and transcripts. -

"Seven Powers" by Hamilton Helmer

The framework that helps translate Halozyme from “interesting biotech” into “durable business,” especially around Cornered Resource and Switching Costs. -

FiercePharma: Drug Delivery Technology Trends

Broader industry coverage on competing delivery approaches, emerging platforms, and why the delivery layer has become strategically important. -

Endpoints News: Halozyme Deal Archive

Deal-by-deal reporting on partnerships, with useful color on terms, motivations, and how the market reacts. -

"The Innovator's Prescription" by Clayton Christensen

A wider lens on healthcare business-model shifts, and why “platform infrastructure” can be one of the most powerful positions in the industry.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music