Garrett Motion Inc.: From Turbocharger Pioneer to Bankruptcy and Rebirth

Introduction: The Counter-Cyclical Bet

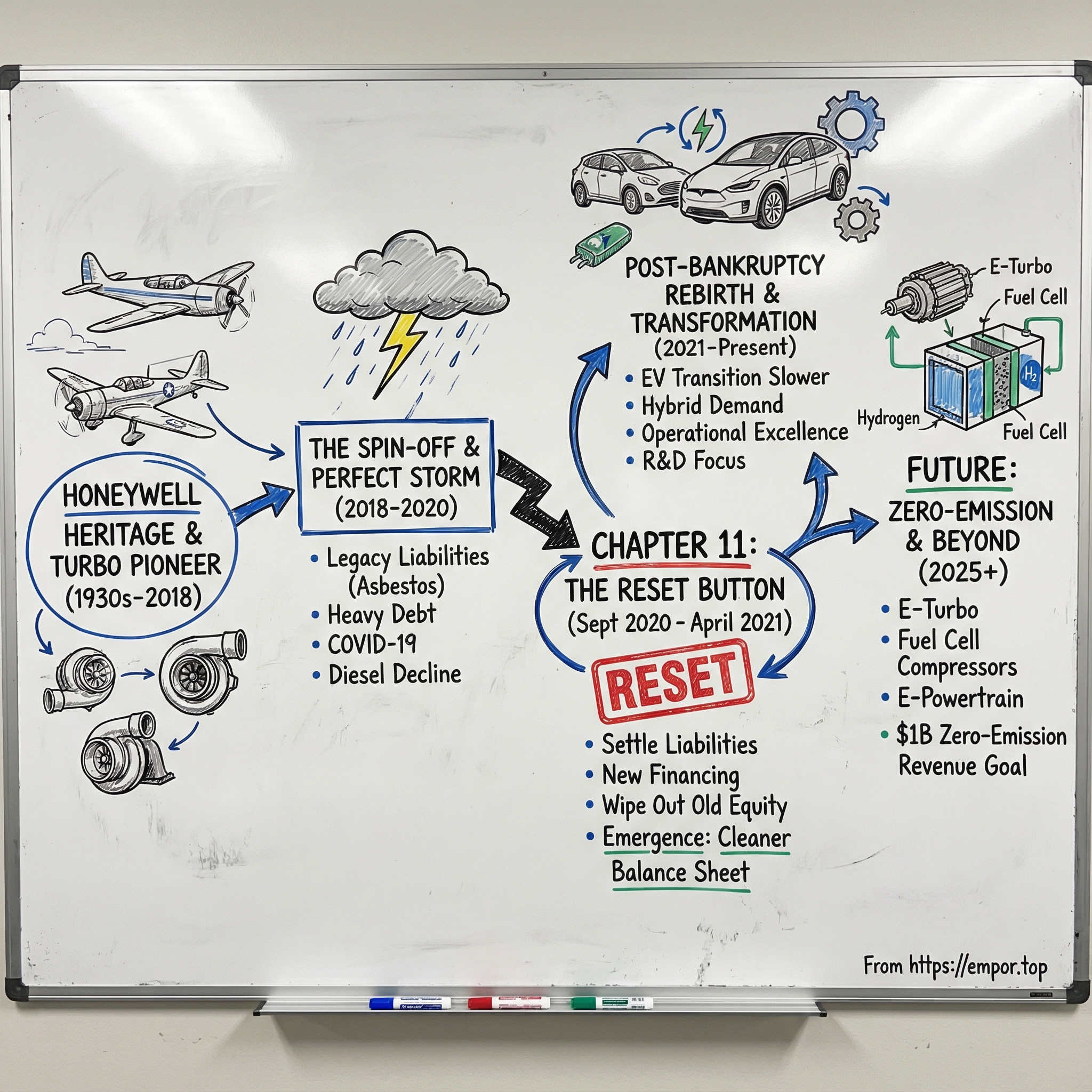

How did a 70-year-old engineering powerhouse go from being part of aerospace giant Honeywell, to a bankrupt spin-off, to a thriving independent company — all in three years?

For most of its life, Garrett was the definition of an “under-the-hood” winner: the kind of business most drivers never think about, but that automakers can’t ship cars without. For decades, it built turbochargers for passenger vehicles and commercial fleets, plus a huge aftermarket business that keeps millions of vehicles on the road. By the time Garrett became a standalone company, it was the world’s leading pure-play turbocharger manufacturer — a position earned through relentless engineering, then nearly wiped out by the way the spin-off was structured.

Because this isn’t really a story about turbochargers. It’s a story about legacy liabilities, a corporate divorce gone wrong, and Chapter 11 used not as a tombstone, but as a tool. It’s also the story of a much bigger debate in the auto industry: what happens when the world acts like the internal combustion engine is already dead, but adoption and infrastructure move slower than the narratives?

Garrett’s technology arc is as dramatic as its balance sheet. It traces back to aviation-era turbocharging — the basic physics of cramming more air into an engine to get more power and efficiency — and stretches forward into modern systems like electric compressors for hydrogen fuel cells. Along the way, Garrett’s hardware ended up everywhere: cars and trucks, off-highway equipment, marine, and power generation.

And yet, in September 2020, Garrett filed for bankruptcy. Not because the products stopped working or customers disappeared overnight, but because the company was carrying a financial load that didn’t match reality — a capital structure weighed down by obligations that had little to do with building great turbos.

That’s what makes this story so useful for anyone who cares about business, investing, or corporate strategy. It’s a case study in how spin-offs can transfer hidden time bombs, how distressed investors can spot value that public markets abandon, and why being “right” about the future isn’t enough — you have to be right about the timeline. Internal combustion wasn’t dead by 2025. Garrett went bankrupt anyway, emerged cleaner than ever, and found itself selling into a world that needed its technology longer than almost anyone predicted.

Today, Garrett is also working on “zero-emission” adjacent technologies — including fuel cell compressors for hydrogen vehicles, and systems that support electric propulsion and thermal management. The company operates six R&D centers, 13 manufacturing sites, and employs more than 9,000 people across more than 20 countries.

This is a story about corporate restructuring as competitive advantage, betting against consensus timelines, and the gap between technology availability and technology adoption.

The Honeywell Heritage & Turbocharger Origins

Picture Los Angeles in 1936. Aviation is booming, the world is edging toward war, and a young entrepreneur named John Clifford “Cliff” Garrett opens a tiny operation supplying tools and parts to the aerospace industry.

The business started as Aircraft Tool and Supply Company. It eventually became Garrett AiResearch — or just AiResearch — a name that would end up stamped on some of the most important airflow hardware of the 20th century.

At first, Cliff Garrett wasn’t chasing cars. He was chasing altitude. His ambition was to make high-altitude flight safer and more practical — especially for passenger aircraft. While already running his Garrett Supply and Airsupply businesses, he set up a small research lab in 1939 to work on “air research” and pressurized flight. The early days were modest: AiResearch’s first lab was simply a small store building on Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles.

Then came World War II, and with it, the proving ground that would define the company’s DNA. AiResearch’s first major product was an oil cooler for military aircraft. Garrett intercoolers ended up on Boeing’s B-17 bombers, and also on the B-25. That wartime work — cabin pressurization, air conditioning, turbines, and other high-altitude systems — built the technical foundation that would later make turbochargers feel almost inevitable.

By the end of the 1940s, Garrett Corporation was listed on the New York Stock Exchange. And in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the company was deep in small gas turbine engines — roughly 20 to 90 horsepower — building expertise in the hard stuff: metallurgy for housings, high-speed seals, radial inflow turbines, and centrifugal compressors. In other words, the exact engineering muscles you need to move, compress, and survive hot, fast-moving air for a very long time.

The real pivot came in 1954, and it came from Cliff Garrett himself. On September 27, 1954, he decided to separate the turbocharger group from the gas turbine department because he saw commercial opportunity in diesel turbochargers. That decision created the AiResearch Industrial Division for turbocharger design and manufacturing, headquartered in Phoenix, Arizona.

The first big customer was Caterpillar. Cliff Garrett led a team to develop a turbocharger for a Caterpillar D9 crawler tractor that launched in 1954 — a moment the company would later point to as the start of its automotive turbo era. Over time, the turbo work expanded far beyond off-highway equipment. Garrett’s Transportation Systems technologies eventually spread across gas, diesel, natural gas, electric, and fuel cell powertrains, and into tens of millions of vehicles.

Turbocharging itself is one of those deceptively simple ideas that changes everything. Exhaust contains energy that would otherwise be wasted as heat. A turbocharger captures that exhaust energy to spin a turbine, which drives a compressor, which forces more air into the engine. More air lets you burn more fuel efficiently. The payoff is the holy trinity: more power from a smaller engine, better fuel economy, and lower emissions.

By 1962, Garrett was powering the world’s first turbocharged production car: the Oldsmobile Jetfire Rocket.

Meanwhile, the broader company kept expanding. Through the 1950s and 1960s, Garrett AiResearch produced a wide range of military and industrial products — fluid controls and hydraulics, avionics, turbochargers, aircraft engines, and environmental control systems for aircraft and spacecraft. It was an aerospace-first engineering house that happened to be building the most important component for the next era of engines.

Then, in 1963, Cliff Garrett died — and the company suddenly became vulnerable. To avoid a hostile takeover of Garrett’s assets by Curtiss-Wright, Garrett Corporation merged with Signal Oil and Gas Company in 1964.

From there, the turbo business rode inside a chain of corporate combinations that eventually led to Honeywell. Garrett AiResearch merged with Signal Oil & Gas to form a company renamed in 1968 as Signal Companies. In 1985, it merged with Allied Corporation to become AlliedSignal. And in 1999, AlliedSignal acquired Honeywell and adopted the Honeywell name.

Through all of it, the turbocharger business remained a crown jewel. Garrett became synonymous with turbo excellence — the brand mechanics asked for, the supplier OEMs designed around, the benchmark competitors chased. As Transportation Systems President and CEO Olivier Rabiller put it: “There is a strong emotional attachment to the Garrett name, which has stood for pioneering turbo technology for more than 60 years and has made an indelible mark on the driving habits of millions of vehicle owners as well as the history of automotive engine performance.”

By the 2010s, Garrett’s turbocharger operation was embedded deep inside Honeywell’s Transportation Systems division: profitable, scaled, and tied into relationships that took decades to earn. It looked like the kind of business you’d protect at all costs.

And yet, the threat that would nearly destroy it wasn’t a competitor, or a technology shift, or even a bad product cycle.

It was something Garrett didn’t create — and couldn’t outrun — once it became a standalone company.

The Spin-Off Setup: Honeywell's Dilemma (2017-2018)

In October 2017, Honeywell made a move that looked, on the surface, like classic corporate housekeeping. It announced plans to spin off its Transportation Systems business, along with ADI Global Distribution and its Home product offerings.

Officially, the rationale was simple: focus. Honeywell wanted to be a tighter, faster-growing industrial company, centered more cleanly around its core franchises like aerospace and building technologies. Unofficially, there was more going on. Activist pressure. The perennial frustration of the “conglomerate discount.” And, lurking behind the scenes, a long-running liability that had been dragging on Honeywell for years.

To understand why the Garrett spin-off was structured the way it was, you have to understand Bendix.

Bendix Corporation was a major manufacturer of automotive brake components for decades. Like many industrial businesses of its era, Bendix used asbestos in brake linings, because asbestos handled heat and friction extremely well. When Allied Corporation merged with Signal Companies in 1985 to form AlliedSignal, Bendix came with it. Then in 1999, when AlliedSignal acquired Honeywell and took its name, Honeywell inherited Bendix — and the legal exposure that came with it.

In other words: as part of the 1999 deal, Honeywell ended up owning both Garrett and Bendix. And for decades, Bendix had produced asbestos-lined brake pads for cars, trucks, and industrial vehicles, exposing workers, mechanics, and consumers to a toxic substance known to cause mesothelioma, asbestosis, and other deadly respiratory diseases. Court documents show Bendix was still selling asbestos-containing brake pads as late as 2001.

By the time Garrett was being prepared for life on its own, the scale of those claims was enormous. Thousands of individuals had filed Bendix-related claims. At the time of the spin, the liabilities were estimated at more than $1.3 billion.

This is where the story turns controversial.

Honeywell structured the Garrett spin so that the newly independent company would take on the vast majority of those legacy liabilities — even though Garrett’s turbocharger business had nothing to do with Bendix brakes.

Under an Indemnification and Reimbursement Agreement, Garrett’s subsidiary became responsible for paying 90% of certain annual liabilities, primarily tied to Honeywell’s Bendix asbestos exposure and related costs, net of 90% of associated insurance and other recoveries. The agreement was set to run through December 31, 2048, or until payments fell below roughly €21 million (or $25 million, as determined at the time of the spin) for three consecutive years — whichever came first. Separately, Garrett agreed to reimburse Honeywell for 90% of Bendix asbestos liabilities, with payments capped at $175 million per year.

The spin-off closed on October 1, 2018. At 12:01 a.m. Eastern Time, Garrett became independent, with Honeywell distributing one share of Garrett common stock for every ten shares of Honeywell common stock. Garrett began “regular way” trading on the New York Stock Exchange that same day under the symbol “GTX.”

Honeywell’s argument was that this wasn’t some sleight of hand — it was history. The Bendix brake operations, and therefore the asbestos liabilities covered by the agreement, had originated inside Honeywell’s former Transportation Systems business. That business had sold Bendix automotive brake pads among other products, and it was that same organization that ultimately became the Garrett spin-off.

But critics saw it very differently. One complaint would later describe the spin as a deliberate effort by Honeywell and its executives — not Garrett’s management — to offload more than $1 billion of legacy asbestos exposure onto Garrett, while binding the new company with covenants that severely limited its flexibility for decades.

And Garrett didn’t just inherit asbestos.

It also started life as a public company with roughly $1.5 billion in debt. Add the operating leverage from the business cycle, and the effective leverage from years of future asbestos payments, and Garrett suddenly looked like one of the most heavily burdened auto suppliers in the market — on day one.

Meanwhile, the transaction strengthened Honeywell. The announced deals were expected to improve Honeywell’s financial position through a combination of one-time dividends and ongoing reimbursements from the spun companies for most of Honeywell’s environmental and Bendix asbestos payments. Around the effective date of the spins, Honeywell was set to receive one-time dividends from Garrett and Resideo totaling about $3 billion, money it intended to use to pay down debt and repurchase its own shares.

The red flags showed up almost immediately. Europe’s diesel market — Garrett’s biggest segment — was already weakening in the long shadow of Volkswagen’s 2015 emissions scandal. EV adoption forecasts were accelerating. And Garrett was walking into public markets at a moment when investors were souring on anything tied to the auto cycle.

It was the perfect setup for a disaster: a great operating business, strapped to an impossible capital structure, launched at exactly the wrong point in the cycle.

The Perfect Storm: Diesel Decline & COVID (2018-2020)

Garrett Motion’s first two years as an independent company turned into a case study in how perfectly ordinary industry headwinds can become existential when you’re carrying too much debt and a liability you never asked for. Three shocks hit in quick succession — and each one made the next harder to survive.

Inflection Point #1: Dieselgate Aftermath

Volkswagen’s diesel emissions scandal, revealed in September 2015, didn’t just damage VW. It reset Europe’s relationship with diesel. Regulators tightened standards, headlines stayed ugly, and consumers started walking away.

That shift mattered more to Garrett than almost anyone. Diesel engines were its biggest turbo market, and for good reason: diesel almost always needs forced induction. Gasoline turbos were growing, but they weren’t yet universal. So as Europe moved from diesel toward gasoline and, increasingly, electrification, Garrett’s most important end market was shrinking — right as it was trying to prove itself as a standalone public company.

Inflection Point #2: US-China Trade War

Then came geopolitics. Starting in 2018, U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods added friction to global supply chains and weighed on sentiment. Chinese auto sales declined — the first annual drop in more than two decades — and uncertainty spiked across the industry.

Garrett was exposed to China both as a manufacturing footprint and as a sales market. In a normal capital structure, you can ride out a choppy year. In Garrett’s new reality, “choppy” meant every forecast miss made the balance sheet feel tighter.

Inflection Point #3: COVID-19

And then the floor dropped out.

In March and April 2020, global auto production plunged — down roughly 20–30% versus the prior year. Garrett’s revenue fell with it. The company could manage its obligations when the factories ran and vehicles shipped. But when volumes collapsed, the math stopped working. Debt service didn’t shrink. The asbestos-related payments didn’t pause. The operating business was still there — it just wasn’t generating enough cash, fast enough, to support the structure it had been handed.

As tensions with Honeywell escalated, Garrett also began challenging the spin-off arrangement in court. The dispute centered on what Garrett described as Honeywell’s unilateral imposition of a decades-long indemnification agreement right before the October 2018 separation — an agreement that required Garrett to reimburse Honeywell for asbestos liabilities tied to Bendix brake pads, a business unrelated to Garrett’s turbochargers.

By the summer of 2020, the relationship was openly adversarial. Honeywell argued it had recently worked cooperatively with Garrett and its creditors to provide covenant and payment relief, and that Garrett was trying to use bankruptcy to push Honeywell’s claims into limbo. Garrett, for its part, was staring at a pandemic-driven collapse in production with an already overburdened balance sheet.

In September 2020, Garrett made its move. On September 20, 2020, Garrett Motion Inc. and certain of its subsidiaries filed voluntary petitions for Chapter 11 protection in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York.

This wasn’t a liquidation. It was a strategic restructuring: use Chapter 11 to reset the capital structure, deal with the asbestos overhang, and give a great operating business a chance to survive on terms that made sense.

Garrett ultimately emerged from bankruptcy on April 30, 2021 — proving the point that had been building since the spin: the products weren’t the problem. The structure was.

The Bankruptcy Playbook: Chapter 11 as Corporate Strategy

What happened in the seven months between September 2020 and April 2021 transformed Garrett Motion from a company suffocating under legacy obligations into something it hadn’t been since the spin: financially workable.

This Chapter 11 wasn’t the Hollywood version of bankruptcy — factories shutting down, customers fleeing, the whole thing collapsing in slow motion. Garrett kept building and shipping turbochargers the entire time. The automakers stayed. The suppliers stayed. And the court-supervised process gave the company exactly what it needed: leverage to renegotiate the parts of its capital structure that were never sustainable in the first place.

Two distressed investing heavyweights immediately saw the setup. Centerbridge Partners and Oaktree Capital Management specialize in messy situations where the underlying business is healthy but the balance sheet is not. Garrett was a textbook case: a global market leader that didn’t need a new product — it needed a new deal.

By late April 2021, that deal was done. The bankruptcy court confirmed Garrett’s plan of reorganization on April 23, 2021. Garrett emerged on April 30, 2021, and prepared to re-list as a public company on Nasdaq effective May 3, 2021, under the ticker symbol GTX, with Centerbridge and Oaktree leading the stakeholder group backing the plan.

The restructuring hit three objectives that mattered.

First, the asbestos indemnity was eliminated. The plan wiped out the prior indemnity and the related liabilities to Honeywell that had been imposed in the 2018 spin, and it settled the litigation between the companies. Practically, this was the heart of the whole case: removing a decades-long overhang that had made Garrett feel permanently overlevered, no matter how well it executed operationally.

The settlement terms were far better for Garrett than the original arrangement. Upon emergence, Garrett made an initial cash payment to Honeywell of $375 million and issued Series B Preferred Stock that entitled Honeywell to certain cash payments from 2022 to 2030. That Series B Preferred Stock was repayable at any time at a present value — approximately $584 million as of emergence, using the agreed discount rate of 7.25%.

Zoom out and the trade becomes clear: Garrett swapped a long-dated obligation with payments capped at $175 million per year — and an implied value well north of a billion dollars — for a package totaling roughly $960 million. That haircut was the point of Chapter 11: use the process to convert an open-ended, destabilizing liability into something finite and financeable.

Second, the company secured new financing. Garrett exited with a $1.25 billion equivalent term loan and a new $300 million revolving credit facility — the kind of capital structure that lets an auto supplier breathe, invest, and survive the next downturn.

Third, existing equity holders were wiped out. Painful, predictable, and essential: when the debt and liabilities exceed the value of the business, the old common gets zeroed. Garrett issued new shares and came back to market with a reset cap table.

CEO Olivier Rabiller framed it the way you’d expect a turnaround CEO to frame it — as continuity plus freedom. Garrett, he said, had operated without interruption, supported by its constituencies, with lenders and pre-petition creditors paid in full. Most importantly, he emphasized that Garrett now had a financing and capital structure designed to support long-term viability and fund accelerated technology development.

The speed was the tell. Seven months from filing to emergence is fast in any industry; in automotive — with complex supply chains, OEM dependencies, and a macro environment still shaped by COVID — it was remarkable.

Why did it work? Because the ingredients lined up. Garrett’s underlying business was real: leading share, deep OEM relationships, and proven technology. Centerbridge and Oaktree brought capital and restructuring muscle. Management stayed in place and maintained credibility. And Honeywell, facing years of litigation and uncertain outcomes, chose certainty.

The broader lesson is simple: Chapter 11 isn’t always an epitaph. Sometimes it’s a tool — a way to fix structural problems that keep a good business from functioning. And in Garrett’s case, it wasn’t the turbochargers that failed. It was the deal they were wrapped in.

The Post-Bankruptcy Transformation (2021-2023)

Garrett emerged from bankruptcy in April 2021 into a world that felt completely reshuffled. The worst of the pandemic-era shutdowns had passed, automakers were ramping production back up, and the story investors had been telling themselves about the end of internal combustion started to look… early.

Inflection Point #4: The EV Transition Proved Slower Than Feared

From 2018 through 2020, “peak ICE” wasn’t just a headline — it was treated like destiny. Automakers laid out aggressive electrification roadmaps. Analysts looked at a turbocharger company and saw a sunset industry.

Then the timeline slipped. EV adoption kept rising, but it also ran into the real world: charging infrastructure gaps, battery costs, range anxiety, and the simple economics of emerging markets. And in the middle of that, hybrids — which many people had dismissed as a temporary bridge — came roaring back.

China became the clearest signal. By 2030, the market share of plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) and range-extended EVs (REEVs) in China is expected to approach that of battery-only EVs (BEVs). Layer on top of that strong momentum in internal-combustion exports, and you get something the market hadn’t priced in back in 2019: a longer, larger runway for turbocharging technology, even in an “electrifying” world.

For Garrett, this was everything. Hybrids still have engines — and those engines are typically smaller, highly optimized, and designed to squeeze out every last unit of efficiency. Turbochargers are one of the best tools for that job. As Toyota’s hybrid-heavy approach proved durable and China’s plug-in hybrid production accelerated, Garrett found demand that the 2018–2020 doomsday narrative simply didn’t anticipate.

And Garrett wasn’t just along for the ride. Its E-Turbo — a turbocharger with an integrated electric motor — is especially well-suited for hybrids and range-extended EVs. It improves response and efficiency, and helps make these powertrains feel stronger and smoother. In other words: if the world was going to electrify in steps, Garrett had a product designed for the in-between.

New Management Strategy: From Survival to Growth

Once the balance sheet stopped dominating every conversation, Garrett’s leadership could finally run the company like an operator again, not a debtor. The strategy shifted from staying alive to building momentum — in three main ways.

First, operational excellence. Garrett optimized its manufacturing footprint, reworked costs, and invested selectively in R&D — the unglamorous execution that matters most in an auto supplier. As the company later put it: “Garrett Motion delivered strong financial performance in 2024, while navigating a challenging industry environment. We expanded adjusted EBITDA margin by 90 basis points year-over-year to 17.2% and generated $358 million in adjusted free cash flow, a testament to our solid operating performance and ability to deliver across industry cycles.”

Second, technology pivots. Garrett leaned into a set of bets that expanded its role beyond a traditional exhaust-driven turbo.

E-Turbo Development: Electric turbochargers integrate an electric motor into the turbo system, reducing turbo lag and improving response at low engine speeds. As 48V mild hybrids move toward the mainstream, Garrett positioned its E-Turbo architecture — with an e-motor on the shaft — to deliver boost even when exhaust energy is limited.

Hydrogen Fuel Cell Compressors: Garrett has been developing compressors for hydrogen fuel cell vehicles since 2016, building on decades of experience in high-speed turbomachinery. Its modular electric fuel cell compressors draw directly from its aerodynamics expertise and operate at extremely high speeds — above 150,000 rpm — with configurations aimed at passenger vehicles, commercial vehicles, and industrial applications. Garrett also pointed to a longer arc here, noting it has been involved with fuel cell innovation for more than 40 years, and launched one of the auto industry’s first fuel cell production car applications in 2016.

E-Powertrain and E-Cooling: Garrett also expanded into electric propulsion systems. Its 3-in-1 E-Powertrain integrates a high-speed electric motor, inverter, and reducer into a single package, aiming for meaningful reductions in size and weight versus conventional approaches.

Third, market expansion. Garrett pushed further beyond passenger cars into heavy-duty trucking — a segment where full electrification remains harder and slower — along with industrial and power generation applications. And it doubled down on the aftermarket opportunity tied to the enormous installed base of turbos already on the road.

Financial Recovery

The financial story followed the operational one: as production recovered from the pandemic shock, revenue rebounded, margins improved, and cash generation returned — the kind of recovery that’s only possible when the capital structure isn’t actively choking the business.

By 2024, Garrett reported net sales of $3,475 million, net income of $282 million (an 8.1% margin), and adjusted EBITDA of $598 million, with a 17.2% margin — an improvement of 90 basis points year over year. Importantly, the sales decline that year reflected broader industry softness rather than a collapse in competitive position. The more telling signal was margin expansion: Garrett became more profitable even in a tougher revenue environment.

Cash flow strengthened as well. The company reported $131 million in operating cash flow and $358 million in adjusted free cash flow for the year.

That set up the next phase of the comeback: acting like a stable company again. By late 2024, Garrett outlined a more shareholder-forward capital allocation approach, including a $50 million annual dividend and a $250 million share repurchase program for 2025. Alongside that, it projected 2025 net sales of $3.3 billion to $3.5 billion — a very different posture than the one it had heading into bankruptcy just a few years earlier.

The Competitive Landscape & Industry Dynamics

Garrett plays in a market that’s both enormous and surprisingly tight. Turbochargers are mission-critical components, but there aren’t many suppliers that can build them at global scale, meet OEM quality standards, and stay competitive on cost. That concentration cuts both ways: it protects incumbents, but it also intensifies head-to-head rivalry.

Garrett Advancing Motion, previously known as Honeywell Turbo Technologies, sits at the top of the field. BorgWarner is the closest peer. Together, they account for roughly 65% of the global automotive turbocharger market — a reminder that this is less a fragmented parts category and more a heavyweight fight.

The Key Competitors

BorgWarner is the main foil in Garrett’s story. It’s bigger and more diversified, with turbochargers housed inside a broader portfolio that spans air management, drivetrain and battery systems, and electric propulsion. In turbos specifically, BorgWarner competes across light vehicles, commercial vehicles, and off-highway applications, and it has developed products like variable geometry and electrically assisted turbos that push performance and efficiency.

Strategically, BorgWarner’s posture is clear: diversify hard into EV-related systems as insurance against internal combustion declining faster than expected. That creates the contrast that defines this whole industry moment. BorgWarner hedges across multiple futures. Garrett stays a pure-play in boosting, and tries to win by being the best at what still sells — while placing selective bets on adjacent technologies.

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and IHI Corporation are formidable Japanese competitors, particularly in Asia. Their advantage is proximity: close relationships with regional OEMs, tight integration with local supply chains, and the ability to expand capacity quickly and cost-effectively.

Cummins Turbo Technologies is the specialist in heavy-duty. Cummins’ engine heritage and deep customer relationships make it a natural force in commercial applications, where duty cycles are brutal and reliability is everything.

Why Garrett Remains Different

Garrett is one of the oldest and most recognized names in turbocharging. It designs, manufactures, and sells turbochargers and electric-boosting technologies for light and commercial vehicle OEMs, serves global independent aftermarket channels, and also develops automotive software and connected vehicle capabilities. Its portfolio is supported by 5 R&D centers, 11 close-to-customer engineering facilities, and 13 manufacturing sites around the world.

But the real differentiation isn’t the site count. It’s the shape of the business.

Pure-Play Focus: Garrett is still fundamentally a boosting company. That focus can be an advantage — organizational attention, manufacturing discipline, deep engineering specialization — but it also comes with concentration risk if the world shifts faster than expected.

Aftermarket Scale: Garrett has the largest turbocharger aftermarket business globally, built around the enormous installed base of more than 65 million Garrett turbos already on the road. That base creates recurring demand that tends to be steadier than new vehicle production, because vehicles age, parts wear, and repairs don’t wait for the next model cycle.

OEM Relationships and Switching Costs: Turbochargers aren’t plug-and-play. The qualification and design-in cycle can take 3 to 5 years, and once a turbo is integrated into an engine platform, switching suppliers often requires expensive re-engineering and re-certification. That stickiness is one of the biggest defenses incumbents have.

The China Question

China is the most important battleground to watch, because it combines massive vehicle production with an industrial policy push to build domestic champions.

Today, foreign incumbents — Garrett, BorgWarner, MHI, and IHI — have historically held an overwhelming position in China’s gasoline turbo market. Gasoline turbos run at punishing temperatures and speeds, and that demands high-quality materials and advanced manufacturing processes. Chinese suppliers have found it difficult to close that gap quickly, particularly in high-end innovation around core components like compressors and turbines.

But “difficult” isn’t “impossible.” The risk isn’t that Chinese competitors match global leaders tomorrow. It’s that the quality gap narrows over time as investment, learning curves, and customer confidence compound. For Garrett, that makes China less a single forecast and more a continuous monitor: capability development, platform wins, and where domestic suppliers start getting designed in.

Market Growth Dynamics

Even with EVs rising, the turbo market has continued to expand. The automotive turbocharger market is projected to grow from about $15.2 billion in 2024 to $22.9 billion by 2030, driven by tighter emissions rules, continued demand for gasoline passenger vehicles, and ongoing advances in electric turbo technology.

In 2024, global turbocharger adoption grew 12% year over year, with Asia Pacific representing about 45% of the market.

The logic is straightforward: the world is electrifying, but the fleet is not flipping overnight. Turbos keep growing because hybrids still use engines, emissions standards keep pushing downsized turbocharged designs, emerging markets remain predominantly ICE-based, and commercial vehicle electrification is likely to lag passenger cars by many years.

Today & The Future: Can Garrett Thrive in an EV World?

Garrett entered 2025 and 2026 in a place that would’ve sounded almost impossible back at the September 2020 bankruptcy filing. The balance sheet was no longer the whole story. The operating model looked stronger. And, most importantly, the end market turned out to be far more resilient than the “ICE is dead” narrative had implied.

In the third quarter of 2025, Garrett reported net sales of $902 million, up 9% year over year on a reported basis (and 6% on a constant-currency basis). Net income came in at $77 million, for an 8.5% margin. Adjusted EBIT was $133 million, a 14.7% margin.

Wall Street noticed. Garrett posted EPS of $0.38 versus expectations of $0.32, and revenue of $902 million versus a forecast around $858 million. The bigger point wasn’t the beat itself — it was what the quarter said about the company’s trajectory: this was a business doing more than just surviving the cycle.

The quarter also came with forward-looking signals. Garrett landed several new light-vehicle turbo programs, including an additional award tied to range-extended electric vehicles. It picked up multiple commercial vehicle and industrial wins, including more than $40 million in expected lifetime revenue for generator sets. And it saw growing interest in its E-Powertrain offering, with additional proof-of-concept initiatives underway with two OEMs.

Off the back of that performance, Garrett raised the midpoint of its 2025 net sales outlook to $3.55 billion.

Zero-Emission Momentum

Here’s the other shift you can’t miss: Garrett wasn’t positioning itself as “just” a turbo company anymore, even if turbos remained the profit engine.

Its investments in non-turbo technologies started showing up in customer validation and external recognition, including the 2024 Stellantis Innovation Award for its zero-emission technologies. Garrett highlighted customer validation for its proprietary 3-in-1 E-powertrain high-speed technology, refrigerant compression technology, and a range of fuel cell compressors.

Management has been explicit about where they want this to go. CEO Olivier Rabiller described a path toward $1 billion in revenue by 2030 from zero-emission technologies, driven by three pillars: fuel cell compressors, e-powertrain, and e-cooling compressors. On the e-powertrain side in particular, the company pointed to progress with Honda, with production expected to start in 2027.

And while battery electric vehicles still dominate the headlines, Garrett’s strategy is built around a more mixed reality: by 2025, more than half of its R&D investment was going toward e-powertrain systems, hydrogen fuel cell compressors, and e-cooling solutions — a bet that the future won’t be one technology, everywhere, all at once.

Capital Allocation Discipline

Post-bankruptcy, one of the clearest markers of “this is a real company again” has been capital allocation. Garrett’s executives laid out an approach centered on returning 75% of free cash flow to shareholders.

In late 2025, the board declared a cash dividend of $0.08 per share, a $0.02 increase, payable on December 15, 2025 to shareholders of record as of December 1, 2025. The company also made a $50 million voluntary early repayment on its term loan — a small line item, but an important signal: Garrett was delevering by choice now, not under duress.

Russell 2000 Inclusion

Another credibility milestone arrived in June 2025, when Garrett joined the Russell 2000 Index after the U.S. market closed on June 27, 2025, as part of the annual reconstitution. Rabiller framed it as a reflection of Garrett’s progress in strengthening its leadership in turbo technologies across passenger vehicles, commercial vehicles, and industrial applications — while also pushing forward on differentiated solutions for zero-emission mobility.

Russell indexes matter because they’re plumbing for institutional capital. They’re used widely by investment managers for index funds and as benchmarks for active strategies, with trillions of dollars benchmarked against the Russell U.S. indexes.

New Market Opportunities

Finally, there’s a growth vector that looks almost obvious in hindsight: industrial applications.

Garrett’s diversification into industrial markets — including data center backup power — has started to show up as a promising near-term revenue stream. The surge in AI data centers has created a corresponding surge in demand for backup power generation, and those generators need turbochargers.

It’s exactly the kind of adjacency Garrett likes: still airflow, still high-speed rotating machinery, still demanding reliability — but less directly tied to passenger-car unit volumes. And if the next decade is defined by electrification plus massive buildout of power-hungry digital infrastructure, that kind of “beyond automotive” demand could end up extending Garrett’s runway in a way few people would have modeled back in 2018.

Strategic Frameworks: Powers & Forces Analysis

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Strong

Garrett and BorgWarner sit in a two-player tier at the top of the turbocharger world, together holding roughly two-thirds of global market share. In a business with heavy fixed costs — engineering, tooling, validation testing, and global manufacturing footprints — scale isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the price of admission. It lets Garrett spread R&D over massive unit volumes, negotiate better supplier terms, and run plants at efficiencies smaller competitors simply can’t match.

Network Effects: Minimal

This isn’t a platform business. Garrett sells engineered components to OEMs and the aftermarket. A turbo doesn’t become more valuable because more people use it, and customers don’t “connect” to each other through the product. There’s no flywheel here.

Counter-Positioning: Emerging

Garrett’s pure-play strategy is a form of counter-positioning against diversified rivals. While others hedge across EV propulsion, batteries, and broader drivetrain systems, Garrett has stayed focused on turbocharging and adjacent “boosting” technologies. If hybrids and ICE stick around longer than the market once assumed, that focus looks brilliant. If electrification accelerates abruptly, it becomes a self-inflicted constraint.

Switching Costs: Very Strong

The real moat in auto supply isn’t just making a good turbo — it’s getting designed in. OEM design cycles run years, and once an engine platform is validated and certified around a specific turbocharger, switching suppliers isn’t a procurement decision. It’s an engineering program: redesign, retesting, revalidation, and regulatory re-certification. That friction creates meaningful stickiness. In the aftermarket, the switching costs are softer but still real: mechanics tend to buy what they trust, and Garrett’s name has deep loyalty in turbo repair and replacement channels.

Branding: Moderate

“There is a strong emotional attachment to the Garrett name, which has stood for pioneering turbo technology for more than 60 years.” That’s true — but it’s also scoped. Garrett’s brand is strong where it matters: with OEM engineers, tier-one procurement teams, and mechanics. Consumers don’t shop for turbo suppliers; they shop for car badges. The exception is the performance aftermarket, where the Garrett name carries genuine weight.

Cornered Resource: Moderate

Garrett has decades of accumulated engineering data, patents, and know-how — the kind of institutional learning you don’t replicate quickly, even with capital. That shows up especially in newer products. Its 400-volt and 800-volt electric fuel cell compressors use patented oil-less foil bearings designed to avoid contamination and deliver strong efficiency and noise performance. Garrett also positioned itself early in hydrogen fuel cell compressors, developing its first generation in-house and launching it in a passenger vehicle in 2016.

Process Power: Strong

Turbochargers live in brutal conditions: extreme heat, tight tolerances, and rotational speeds north of 100,000 RPM. Building them reliably at scale is a process game — precision machining, balancing, materials science, quality control, and constant iteration. Decades of manufacturing learning compound into an advantage that’s hard to see from the outside, and even harder for a new entrant to match.

Overall Power Position: Garrett has real moats — especially scale, switching costs, and process power — but they sit under a single, unavoidable shadow: if the market shifts faster than expected toward pure electrification, those advantages matter less.

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry: High

This is a concentrated industry, but it’s not cozy. A handful of global players compete aggressively, and OEMs are expert buyers who constantly benchmark suppliers on cost, performance, and reliability. Even with differentiated technology, pricing pressure never goes away.

Threat of New Entrants: Low

Cracking this market is hard. Turbochargers demand deep expertise in core components like compressors and turbines, plus years of validation credibility with OEMs. That creates big barriers: capital intensity, long timelines, and high consequence for quality failures. Chinese domestic entrants are the most credible long-term threat, but in the near term they still face meaningful gaps in high-end innovation and proven durability.

Supplier Power: Medium

Inputs like special steels and aluminum can be volatile, and e-turbo-related systems introduce additional supply sensitivities. Some specialized components may come from sole or limited sources. Garrett’s scale helps it negotiate, but it can’t fully escape commodity and supply-chain dynamics.

Buyer Power: High

Garrett sells to a concentrated set of global automakers — large, sophisticated customers with leverage and alternatives. Long-term programs and switching costs help stabilize relationships, but OEMs still have the negotiating upper hand, especially when volumes soften.

Threat of Substitutes: Very High

This is the existential force. Battery electric vehicles don’t need turbochargers. If battery costs fall faster than expected, charging infrastructure expands quickly, or policy mandates harden, the addressable market for traditional turbocharging can shrink sharply. Everything in Garrett’s strategy ultimately comes back to timing: how fast the world substitutes away from combustion.

Industry Attractiveness: Moderate, but under structural pressure. The opportunity is real — especially in hybrids and longer-lived ICE markets — but the transition clock is always ticking.

Business & Investing Lessons: The Playbook

Garrett Motion’s arc is dramatic — but the takeaways are surprisingly practical. If you’re a founder thinking about financing, an investor underwriting risk, or a strategist watching how corporate structures shape outcomes, this is a story with receipts.

Lesson 1: Capital Structure Kills

Garrett’s turbocharger business didn’t break. The technology stayed world-class, OEM relationships held, and the company kept shipping product even through chaos.

What failed was the structure wrapped around the business. Garrett went into the spin-off carrying heavy debt, then got pinned under the Bendix asbestos indemnification — a long-dated obligation that had nothing to do with building turbochargers, but everything to do with whether the cash flows could ever belong to shareholders.

The lesson is simple and brutal: always stress-test leverage against real downside scenarios. Spin-offs that offload liabilities onto the newco can look clean on day one and become existential on day 700. When you evaluate any company, don’t stop at operating metrics. A great business can still get destroyed by bad financing.

Lesson 2: Chapter 11 Can Be a Feature, Not a Bug

Garrett’s Chapter 11 is a reminder that bankruptcy isn’t always the end of the story. Sometimes it’s the mechanism that makes the story survivable.

The restructuring did what years of litigation and negotiation couldn’t: it eliminated the previous asbestos indemnity and the related liabilities to Honeywell that had been imposed in the 2018 spin, and it settled the litigation between the companies. By removing that decades-long overhang, Garrett dramatically reduced its effective leverage and regained operational and strategic flexibility.

Distressed investors who stepped in weren’t betting on a miracle product. They were betting on a clean reset. They saw a healthy operating business trapped in an unhealthy structure — and understood that Chapter 11 could separate the two.

Lesson 3: Consensus Can Be Wrong on Timing

From 2018 through 2020, the market treated “peak ICE” like a settled fact. Turbochargers were viewed as a melting ice cube, and Garrett’s equity priced in a fast, clean transition away from combustion. That narrative amplified the stock collapse and made everything harder.

But by late 2025, the world looked messier — and for Garrett, that messiness was opportunity. Hybrids surged. Emerging markets stayed ICE-heavy. Garrett put up strong results. And in 2024, 75% of China’s 5.86 million vehicle exports were still ICE-powered, even as hybrid formats grew quickly.

The lesson: being right about direction doesn’t mean you’re right about timing. Technology transitions often take longer than forecasts — and in capital allocation, timeline is the whole game.

Lesson 4: Pure-Play vs. Conglomerate Discount

Garrett’s closest peer, BorgWarner, has diversified aggressively into electric propulsion. That provides insurance if ICE declines faster than expected, but it can also dilute focus and complicate where capital goes.

Garrett’s pure-play posture flips that trade. Focus can create real execution advantages — but it also concentrates risk if the transition clock accelerates.

The lesson: different playbooks fit different risk tolerances. The “right” approach depends on your view of transition timing and your comfort with outcomes that can get more binary than most investors like to admit.

Lesson 5: Aftermarket Moats

Most people model a turbo business like it lives and dies with new car production. That misses the installed base.

In 2024, OEM fitment represented 77.81% of the turbocharger market, because nearly every new light vehicle in Europe — and more than 60% in China — shipped with a turbo. At the same time, the replacement segment was expected to grow at a 9.40% CAGR as the global turbo fleet aged.

This is where Garrett has a quiet advantage: more than 65 million Garrett turbos are already on the road. That installed base creates replacement-cycle revenue that tends to be more defensive than new vehicle sales. As fleets age, the aftermarket can become more valuable — even as investors fixate on “peak turbo” in new builds.

Bear vs. Bull Case & Key Performance Indicators

Bull Case

ICE/Hybrid Runway: The core bet is that internal combustion and hybrids stick around through 2035 and beyond — especially in emerging markets where charging networks and affordability move slower than press releases. Europe still matters a lot here: it holds about 37% of the automotive turbocharger market, and demand is heavily driven by emissions compliance and the continued rise of hybrids.

Content Per Vehicle Growth: Even if total ICE volumes flatten, Garrett can still win by selling more technology per vehicle. Plug-in hybrids often need higher-spec turbos, and twin-turbo setups increase content. If hybrids keep proliferating, Garrett’s revenue per platform can rise even without a booming unit market.

Aftermarket Expansion: An aging global fleet of turbocharged vehicles means more replacements. That aftermarket demand tends to be steadier than OEM build cycles — the kind of revenue stream that can keep cash flowing even when new-car production cools.

Zero-Emission Optionality: Fuel cell compressors and e-powertrain systems aren’t the profit engine today, but they’re real shots on goal. If hydrogen or other zero-emission architectures scale, Garrett has a path to meaningful new revenue streams beyond traditional turbos.

Clean Balance Sheet: Post-bankruptcy, Garrett finally has the flexibility it never had after the spin. Without the same debt and liability overhang, it can return capital, invest through cycles, or pursue M&A from a position of strength rather than survival.

Valuation Gap: If markets continue to treat Garrett like a shrinking “ICE-only” supplier, it can remain cheap relative to diversified peers. But if the company keeps executing — and the hybrid runway proves longer — there’s a case for multiple expansion from the current roughly 6–8x EBITDA range toward the 10–12x range seen in more diversified competitors.

Bear Case

EV Acceleration: The existential risk hasn’t disappeared. A faster-than-expected EV ramp — driven by battery breakthroughs, tougher policy mandates like European ICE bans, or a sharp shift in consumer demand — would compress Garrett’s timeline and reduce the market for conventional boosting.

Chinese Competition: In the near term, Chinese suppliers still struggle to match foreign incumbents at the high end, especially on innovation and durability. But “near term” can be deceptive. Over a 5–10 year window, heavy investment and learning curves could narrow the gap and pressure share and pricing in the world’s most important auto market.

Cyclical Auto Exposure: Garrett is still tied to global vehicle production. A recession or another sudden production shock could hit volumes hard. The difference versus 2020 is that the balance sheet now provides more cushion — but the cyclicality remains.

OEM Vertical Integration: Automakers always have the option to pull critical components in-house. If major OEMs decide turbochargers are strategic enough to vertically integrate, supplier pricing power weakens and the addressable opportunity shrinks.

Stranded Assets: A rapid transition away from combustion would also create a more painful problem: factories, tooling, and specialized engineering talent built for turbos could become underutilized with limited alternative uses.

Hybrid Boom Proves Temporary: If today’s hybrid surge is just a short bridge — a five-year bump rather than a 15-year runway — Garrett’s “more time than expected” thesis weakens fast.

Key Performance Indicators to Track

For investors following Garrett Motion, two metrics tell you the most about whether the comeback is durable:

1. Adjusted EBITDA Margin: This is the read on operating discipline as the mix shifts and OEM pricing pressure persists. The move from 16.3% in 2023 to 17.2% in 2024 was a strong signal. Holding in the mid-to-high teens supports the post-bankruptcy playbook; a drop below 15% would suggest the leverage in the model is fading.

2. Free Cash Flow Generation: Cash is what funds everything: dividends, buybacks, debt paydown, and the R&D needed for e-turbos and zero-emission adjacencies. In 2024, Garrett reported $131 million in operating cash flow and $358 million in adjusted free cash flow. If the company can keep generating roughly that kind of free cash — on the order of $300 million-plus annually — it reinforces that this isn’t just an accounting recovery. It’s a business that can compound again.

Epilogue: Recent Developments & What's Next

“Garrett delivered another strong quarter in Q3, outperforming the industry, expanding our Adjusted EBIT margin to 14.7% and generating $107 million of adjusted free cash flow,” said Olivier Rabiller, President and CEO of Garrett. “This performance enabled $84 million in share repurchases in Q3 and a 33% increase in our quarterly dividend beginning in Q4, reinforcing our disciplined approach to capital allocation.”

That quote lands because it captures what would have sounded absurd in 2020: Garrett is no longer fighting for oxygen. It’s beating expectations, throwing off cash, and giving it back to shareholders.

The Q3 2025 earnings surprise — nearly a 19% beat versus estimates — wasn’t just a one-off market bounce. It reflected a company that’s executing better than the industry around it, with a product line that’s staying relevant longer than the world assumed when “ICE is dead” became the default narrative.

And the wins aren’t confined to the traditional passenger-vehicle turbo business. Garrett secured new marine and auxiliary power awards for its largest turbocharger, with production expected to start in 2026. It entered a partnership with SinoTruk to co-develop e-powertrain systems for light and heavy trucks by 2027. And it was recognized with the 2024 Stellantis Innovation Award for its differentiated zero-emission technologies.

These kinds of announcements matter because they show how the company is widening its playing field. The SinoTruk collaboration, in particular, is a signal: Garrett is pushing deeper into Chinese commercial vehicles — a massive market segment that, in all likelihood, stays combustion-heavy longer than passenger cars.

The Big Questions for 2025-2030

Hybrid Durability: Will plug-in hybrids remain dominant for 15+ years, or are they a 5-year bridge? The answer shapes Garrett’s runway more than any single product launch.

China Competitive Threat: Can Garrett hold share as domestic Chinese suppliers improve quality? The gap is real today, but it’s not guaranteed to stay that way.

Zero-Emission Pivot Timing: Is the heavy investment in e-powertrains and fuel cell compressors early-and-right, or early-and-expensive? The company’s $1 billion revenue target by 2030 will be a clear scoreboard.

Capital Allocation Discipline: Can management maintain its commitment to returning 75% of free cash flow without overreaching? In cyclical industrial businesses, discipline is easy to promise and hard to sustain.

Data Center Opportunity: Can backup power generation for AI data centers become a meaningful, durable revenue stream? Industrial demand could end up smoothing the volatility of the auto cycle.

Why This Story Matters

Garrett Motion is the ultimate counter-cyclical bet. Everyone assumed ICE was dead by 2025. Garrett went bankrupt under legacy liabilities that had nothing to do with turbochargers. It emerged cleaner than ever — and then discovered the world still needed what it makes, for longer than almost anyone modeled.

The story illustrates:

Corporate restructuring as competitive advantage — Chapter 11 turned an impossible setup into a financeable company.

Betting against consensus timelines — The market’s 2018–2020 view of ICE decline was too aggressive on timing.

The difference between technology availability and technology adoption — EV technology can be real while adoption remains uneven, regional, and slow.

How Chapter 11 can save great businesses from bad balance sheets — the operations didn’t fail; the structure did.

The next three to five years will decide what this really is: a durable value recovery, or a melting ice cube with a temporary reprieve. The swing factor is still transition timing. But if you believe the world stays messy — hybrids scaling, commercial fleets moving slower, industrial applications growing — Garrett looks less like a relic and more like a company that rebuilt itself at exactly the moment the market stopped pricing in nuance.

Further Reading

If you want to go deeper on Garrett Motion — and on the bigger forces shaping the turbocharger business — here are the best primary sources and a few industry staples:

- Garrett Motion Annual Reports (2021-2024) — The SEC filings are the cleanest way to understand the company’s financials, strategy, risk factors, and how management describes the post-bankruptcy turnaround in its own words.

- Honeywell Spin-Off Investor Presentation (2018) — The key to understanding why Garrett’s capital structure broke the moment the cycle turned. The original transaction terms matter.

- IEA Global EV Outlook 2024-2025 — A solid baseline for EV adoption curves, regional differences, and the “timing vs. direction” debate that sits under Garrett’s entire thesis.

- BorgWarner Annual Reports — The most useful side-by-side comparison for strategy and positioning, given BorgWarner is Garrett’s closest global peer.

- SAE International Technical Papers — The best deep technical reading on how turbochargers evolved, why e-turbos matter, and what future architectures could look like.

- BloombergNEF Long-Term EV Outlook — Helpful for framing the long-duration assumptions behind both the bull and bear cases for internal combustion and hybrids.

- Centerbridge Partners / Oaktree Case Studies — Great context on the distressed-debt playbook and why sophisticated capital often runs toward complexity when public markets run away.

- McKinsey Automotive Insights — Broad industry context on powertrain transitions, regulation, and why forecasts so often get the timeline wrong.

- Chapter 11 Restructuring Documents — The court filings show the actual mechanics: who negotiated what, how the Honeywell liability got resolved, and what the “reset” really cost.

- Garrett Sustainability Reports — Useful for tracking the company’s stated roadmap for zero-emission adjacent products and how it frames its ESG priorities.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music