Globalstar Inc.: The Story of Satellite Communication's Perpetual Underdog

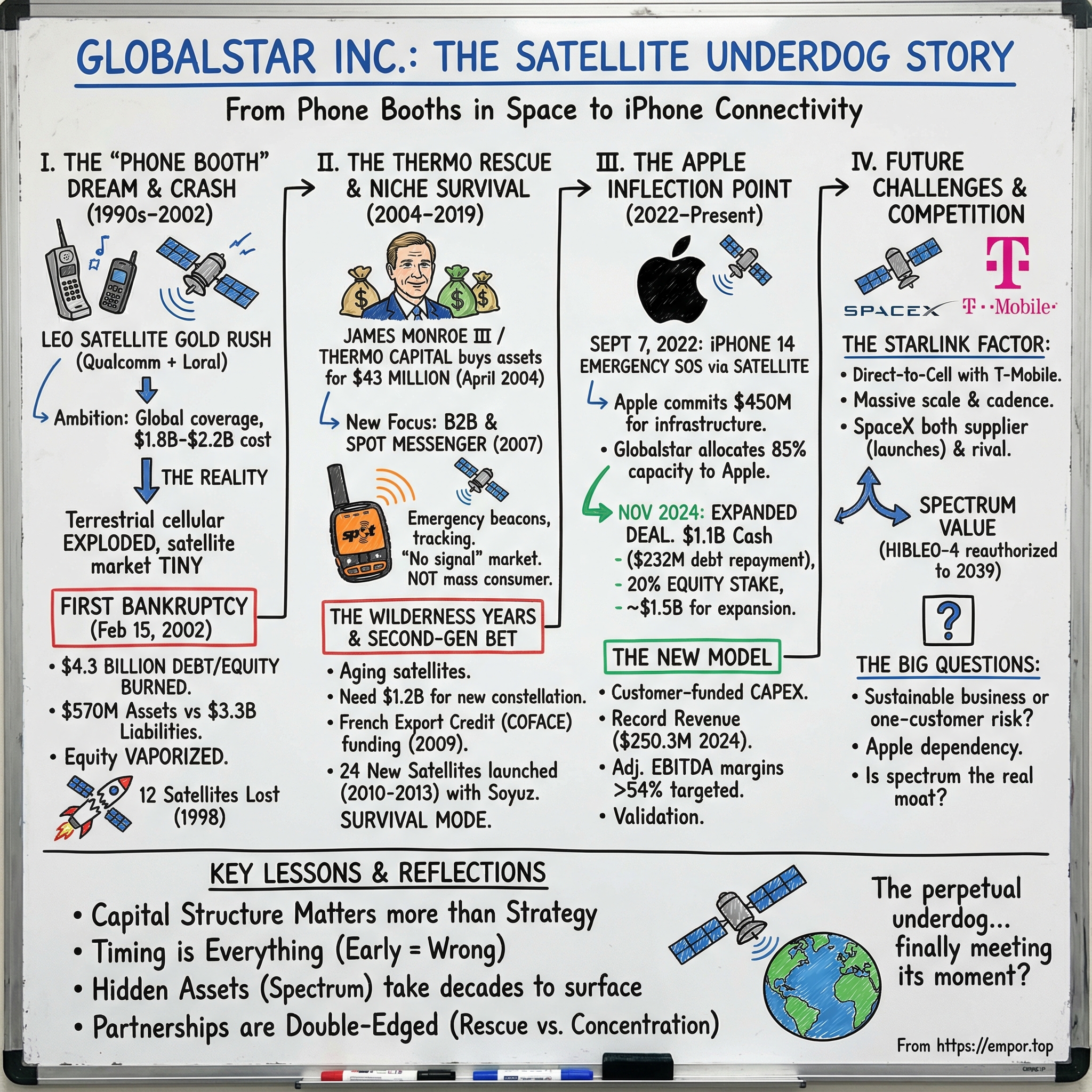

I. Introduction: A Phone Booth in Space, or a Bet on the Impossible?

Picture the scene: September 7, 2022, at Apple’s Steve Jobs Theater. The invite is a starry night sky stamped with two words: “Far Out.” Millions tune in expecting the usual iPhone upgrades. Instead, Apple drops a curveball: the iPhone 14 can talk to satellites.

Not with a dish. Not with a specialized gadget. With the same slim rectangle already in your pocket.

And then comes the twist. Underneath Apple’s polished demo is a company almost no one had been paying attention to: Globalstar, a Louisiana-based satellite operator that had already gone bankrupt twice. When the market connects those dots, Globalstar’s stock surges.

What Apple is actually shipping is both simple and mind-bending. If you’re somewhere with no cellular service, a compatible iPhone can point its antenna at a passing satellite, compress a short message, and push it through Globalstar’s network down to a ground station. From there, it can be routed to people who can help—like emergency responders. The “space” part feels futuristic; the implementation is intensely practical.

The crazier part is how old the plumbing is. Globalstar’s roots go back to the late 1990s, built through a partnership with Loral Space & Communications and Qualcomm—right in the middle of the era when investors were convinced the future of telecom would be “phone booths in space.”

So how did a company that filed for Chapter 11 protection on February 15, 2002—after $4.3 billion of debt and equity had gone into the dream, with $570 million of assets against $3.3 billion of liabilities—end up powering a headline feature on the world’s most important consumer device? How did assets Thermo Capital Partners bought for $43 million become, two decades later, critical infrastructure for Apple?

This isn’t just a comeback story, though it has all the ingredients. It’s a case study in capital intensity, brutal technology timing, patient ownership, and the weird alchemy that happens when infrastructure finally meets the moment it was built for. Globalstar’s ride—from 1990s telecom mania, through near-death experiences, to an unlikely renaissance—puts a spotlight on a few uncomfortable truths: being early is often indistinguishable from being wrong; capital structure can matter more than strategy; and “hidden” assets can stay hidden for decades, until suddenly they don’t.

The question that hangs over everything is deceptively simple: is Globalstar now a real business with durable advantages, or is it still a fragile bet on one customer relationship that could vanish with a renegotiation? The answer, as we’ll see, is messy—and that’s exactly why this story is worth telling.

II. The LEO Satellite Gold Rush: When Space Seemed Like the Answer

To understand Globalstar, you have to rewind to the early 1990s—and to a very specific kind of telecom fever.

The Berlin Wall had fallen. Defense budgets were shifting. Aerospace engineers who’d spent careers building Cold War hardware were suddenly looking for civilian-sized problems. Meanwhile, mobile phones were still expensive, bulky status symbols. Coverage was spotty. Roaming was painful. For most of the planet, the idea that you could count on a signal everywhere was pure fantasy.

So the pitch that took hold was almost irresistible: skip the towers entirely. Put the network in the sky.

Build a constellation of satellites in low Earth orbit and you could, in theory, sell phone service anywhere. A hiker in the Himalayas could call home. A ship in the Pacific could reach shore. Whole countries without modern telecom infrastructure could leapfrog straight to global connectivity. It was “phone booths in space,” and it sounded like the cleanest shortcut ever invented.

Globalstar was born inside that moment. In 1991, Qualcomm teamed up with spacecraft manufacturer Loral to create a new LEO satellite system. The plan was to launch a 48-satellite constellation and sell capacity through local terrestrial service providers. The projected cost was $1.8 billion—then, as these projects tend to do, it crept upward, eventually reaching $2.2 billion. A 1998 launch failure wiped out 12 satellites, commercial service slipped to 2000, and by 2002 Globalstar was in bankruptcy protection.

And Globalstar wasn’t some lone moonshot. It was part of a broader space-telecom land grab. Iridium, Odyssey, and Teledesic all came charging in with their own grand designs. In the end, all but Iridium scaled back or canceled their intended constellations under the weight of huge costs and a market that turned out to be far smaller than the hype. Even the survivors took brutal financial hits.

The technical choices made early on mattered far more than most investors understood. Iridium built something uniquely complex: satellites that talk to each other in space, not just down to Earth and back up again. That inter-satellite connectivity is what allows Iridium to connect anywhere to anywhere else, even over oceans and poles. Globalstar went with a simpler “bent-pipe” approach—satellites that act more like mirrors, relaying signals down to ground stations without processing them in orbit. That made the satellites cheaper, but it also meant Globalstar needed a dense network of ground stations, and coverage was inherently constrained to places within reach of those gateways.

The corporate structure matched the ambition. In March 1994, Loral and Qualcomm announced Globalstar LP, a U.S. limited partnership. Eight other companies joined financially, including Alcatel, AirTouch, Deutsche Aerospace, Hyundai, and Vodafone. On paper, it looked like the kind of consortium that only forms when the future feels obvious.

Globalstar even positioned itself as the more affordable alternative to Iridium. In March 1994, it said it expected to charge $0.65 per minute, versus $3 per minute from Iridium, and predicted a 1998 system launch off that original $1.8 billion budget.

The problem was that the ground shifted while Globalstar was still building the sky.

When these LEO narrowband networks were conceived, cellular coverage was limited and unreliable in many regions, and international roaming was a mess. Satellite phones seemed like the missing layer that would fill the gaps towers couldn’t reach. But terrestrial mobile didn’t just improve—it exploded. Month by month, more towers went up, more spectrum got allocated, and more countries built out modern networks. The very market satellites were meant to serve was shrinking in real time, even as rockets were carrying the constellation into orbit.

That mismatch—between how fast you can build in space and how fast the world can build on the ground—would end up torching billions in capital. And it set Globalstar on the long, brutal path that eventually made the Apple partnership feel so improbable.

III. Building the First Constellation: Engineering Triumph, Business Tragedy

The first call on the original Globalstar system happened on November 1, 1998. Qualcomm chairman Irwin Jacobs dialed from San Diego. On the other end, in New York, was Loral Space & Communications CEO and chairman Bernard Schwartz. The signal went up, hit the network, and came back down. Years of hardware, launches, and spectrum paperwork collapsed into one clean, human moment: hello.

Getting there, though, was anything but clean.

Globalstar started launching satellites in February 1998, then took a gut punch on September 9, 1998: a launch failure that destroyed 12 satellites in one shot. Space is unforgiving on a normal day. It’s even less forgiving when you’re relying on Russian Soyuz rockets at a time when Russia’s space program was under serious funding strain. Every delay didn’t just cost money. It cost time, and time was the one thing Globalstar couldn’t afford to lose.

Still, the constellation came together. In October 1999, Globalstar began “friendly user” trials with 44 of the 48 planned satellites. By December, it rolled out limited commercial service to about 200 users. In February 2000, it flipped the switch to full commercial service—48 satellites operating, plus spares, with coverage spanning North America, Europe, and Brazil.

And here’s the cruel part: the system worked.

The problem was the price of making it work. Satellite calls started around $1.79 per minute. The handset was a luxury item too. In mid-2000, Globalstar USA cut the phone price from $1,199 to $699 if you committed to service—still a lot of money to pay for the privilege of paying nearly two bucks a minute.

On Earth, everything was moving in the opposite direction. GSM coverage kept spreading across Europe. Prepaid cellular exploded in developing markets. In many places, you could get a phone for free with a contract, and the cost of a minute kept sliding toward “who even thinks about it anymore?”

So the tragedy wasn’t technical. It was economic. Globalstar had built a global-ish phone service for the moment just before mobile networks turned into the default. The satellites were real. The calls were clear. But the reason to use them was disappearing right as the constellation reached orbit.

Wall Street could see it too, eventually. Globalstar Telecommunications Ltd. had gone public in February 1995, raising $200 million on NASDAQ. The IPO was priced at $20 per share, which works out to $5 after two later stock splits. At the peak of the telecom bubble, the stock hit about $50 (post-split) in January 2000. Then the mood turned. By June 2000, some institutional investors were already openly predicting bankruptcy. The shares slid under $1, and NASDAQ delisted Globalstar in June 2001.

The broader telecom crash of 2000–2001 finished what competition started. Globalstar had poured billions into fixed infrastructure for a market that, at consumer scale, never really arrived. The math was merciless: enormous capital costs, a customer base that numbered in the tens of thousands instead of the millions the model needed, and losses that burned cash faster than a young satellite company could replace it.

IV. First Bankruptcy: A Billion-Dollar Write-Off for Pennies on the Dollar

On February 15, 2002, Globalstar’s predecessor company and three of its subsidiaries filed voluntary petitions under Chapter 11 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code. After $4.3 billion of total debt and equity had been sunk into the dream, Globalstar Telecommunications filed for protection listing $570 million in assets against $3.3 billion in liabilities.

That’s the whole story in one brutal balance sheet. Big-name investors and telecom giants had financed a space-age network… and ended up with a company that, on paper, wasn’t even close to solvent. Equity was effectively vaporized. Creditors braced for steep losses. And the satellites? They kept gliding overhead, perfectly functional and totally indifferent to the carnage happening on the ground.

The company was already cutting hard before the filing. Globalstar reduced its workforce by approximately 300 employees primarily through three separate actions in March, July, and September of 2001. It recorded employee separation costs of $4.9 million in 2001 and $0.2 million in 2002.

Then, in the middle of the wreckage, a new character enters who ends up shaping the next two decades of this story: James Monroe III, founder of Thermo Capital Partners. Monroe had started in 1984 with $40,000—the money he and his wife made from selling their home—and built businesses selling diesel engines, developing power plants, and investing in fiber-optic networks. In Globalstar, he saw something everyone else had written off: a functioning satellite system, spectrum rights, and a real—if much smaller—market for satellite voice and data, especially for the parts of the world beyond reliable cell coverage.

Thermo moved in while the asset was still in bankruptcy. In December 2003, Thermo entered into a preliminary agreement to acquire Globalstar, contingent on regulatory approval and the successful completion of several settlement and technical agreements. Regulatory approval came in early March 2004, and the U.S. Bankruptcy Court approved the last of the required agreements on March 31.

On April 14, 2004, Globalstar announced it had completed its financial restructuring after Thermo formally acquired its main business operations and assets.

The price tag is the kind of number that makes you reread the sentence: $43 million. That’s what Thermo paid for satellites, ground stations, spectrum licenses, and the operational backbone that had cost billions to build. Monroe was, in effect, buying a space network for something closer to real-estate money.

When the new Globalstar emerged from bankruptcy in April 2004, ownership was split between Thermo Capital Partners (81.25%) and the original creditors of Globalstar L.P. (18.75%).

So was this a brilliant contrarian trade—or a value trap with a better press release? Monroe’s bet was simple: the expensive part—the constellation—was already in orbit, the spectrum still mattered, and while the consumer phone-booth-in-space dream was dead, a niche business could still live. Thermo expected Globalstar to post at least 70% year-over-year growth in 2004 and to be operationally profitable by the fourth quarter of that year.

V. The Second Act: Finding a Niche (2004-2010)

The post-bankruptcy Globalstar barely resembled the consumer-focused moonshot that had burned through billions. This version was a scrappier, more grounded B2B business, selling satellite connectivity to people who actually needed it—not executives who liked the idea of a satellite phone, but crews and agencies operating where “no signal” is the default.

Globalstar supported land-based and maritime customers across oil and gas, government, mining, forestry, commercial fishing, utilities, military, transportation, heavy construction, emergency preparedness, business continuity, and even a small but meaningful slice of individual recreational users.

That last category would become the most visible part of the company’s comeback attempt.

In August 2007, Globalstar announced SPOT Satellite Messenger, to be marketed through a new subsidiary, SPOT, Inc. Manufactured by Globalstar partner Axonn LLC, SPOT combined Globalstar’s simplex data technology with a Nemerix GPS chipset. It was a product built to lean on what still worked well in Globalstar’s aging system: the L-band uplink used by simplex modems. The launch came in early November 2007.

SPOT was a smart pivot. Instead of trying to win the voice-calling war against cell phones—a war Globalstar had already lost—SPOT focused on a simpler promise: if you’re out of reach, you can still get a message out. The device could send a preset note to family, act as a basic GPS tracker, and, most importantly, function as an emergency beacon that could connect with search-and-rescue when things went sideways.

Over time, those little orange devices spread across the outdoor world. The company said SPOT devices were involved in nearly two rescues a day. It wasn’t mass-market consumer telecom. It was something narrower, and far more real: a safety net for people beyond the edge of coverage.

But even a great niche comes with a ceiling. The emergency beacon and recreational market could help stabilize the business, yet it was never going to be big enough to effortlessly carry the cost of running a satellite network. Globalstar still faced the same hard physics and harder economics: it needed scale it didn’t have, capital it couldn’t easily raise, and—looming over everything—a technology refresh it couldn’t postpone.

Because the clock in space never stops.

The first-generation satellites had been designed for roughly a seven-to-eight-year lifespan. By 2005, some began reaching the end of their operational lives, and in December 2005 Globalstar started moving certain satellites into a graveyard orbit above LEO. Then the more troubling news arrived. In an SEC filing dated January 30, 2007, Globalstar warned that previously identified problems with the satellites’ S-band amplifiers—critical for two-way communications—were occurring at a higher rate than expected, and could ultimately reduce two-way voice and duplex data service as soon as 2008.

That’s the kind of sentence that can kill a satellite company.

You can’t send a service technician to swap an amplifier in orbit, at least not in any way that makes business sense. When satellites fail, you replace them. And replacements don’t come cheap—they require manufacturing, launches, and years of planning. For a company that had only just clawed its way out of bankruptcy, the question wasn’t theoretical. It was existential: where would Globalstar find the money to rebuild the very infrastructure it depended on?

VI. Second-Generation Constellation: The Existential Gamble

Globalstar’s second-generation constellation wasn’t just an engineering project. It was a financing problem so difficult it almost didn’t matter whether the satellites could be built—because the company still had to find the money first.

The need was straightforward and terrifying: roughly $1.2 billion to build and launch 24 new satellites. That’s an enormous bill for a business with modest revenue, a damaged reputation, and little access to traditional capital markets.

In December 2006, Globalstar awarded Alcatel Alenia Space (later known as Thales Alenia Space) a contract worth about 661 million euros to construct the 24 second-generation satellites. The new birds were designed for a 15-year lifespan—nearly double the first generation’s design life—which mattered because Globalstar couldn’t afford to repeat this scramble every seven or eight years.

The company later described the Thales contract at about 671 million euros, which it pegged at the time to $871 million. There was even a potential price reduction of 28 million euros if all satellites were delivered by late 2010. But manufacturing was only half the problem. Add launch and insurance—estimated at about $10 million per satellite—and the total bill climbed to roughly $1.3 billion.

So how do you fund a billion-dollar rebuild when your credit history includes “Chapter 11”?

Monroe and his team went looking for a structure that didn’t require Globalstar to be a normal, bankable borrower. The breakthrough came in France. With help from Thales and a group of French banks, Globalstar secured an Export Credit Facility backed by COFACE, a private French company that provides export credit finance as agent for the French government, including state guarantees. The facility provided a state guarantee for 95% of a syndicate of bank loans totaling €452,781,326. Negotiations with COFACE, the French Ministry of Finance, and the banks ran through the fall of 2008 and into the first half of 2009, and the facility became a cornerstone of the entire plan. It was funded, and an initial drawdown was made by Thales, on July 1, 2009.

Later that month, in July 2009, Globalstar announced it had secured complete financing for the second-generation constellation and signed an amendment to the initial contract to set updated production conditions.

In plain terms, the French government effectively backstopped a large portion of the manufacturing cost. France had its own incentive: Thales Alenia Space was French-Italian, the satellites would be built in France, and the arrangement supported French aerospace jobs. For Globalstar, that blend of industrial policy and export finance wasn’t politics—it was oxygen.

Then came the launches. The first six second-generation satellites went up on October 19, 2010. Another six followed in July 2011, and another six in December 2011. On February 6, 2013, the final six launched, completing the 24-satellite deployment.

That last launch used a Soyuz 2-1a rocket, continuing a steady cadence: six satellites at a time, lifted from Kazakhstan’s Baikonur Cosmodrome. Each spacecraft weighed roughly 700 kg at launch and was 3-axis stabilized. It was old-world space infrastructure—Soviet-era hardware and a historic launch site—commercialized to keep a struggling American satellite operator alive.

But even as the constellation came together, the deal almost blew up back on the ground.

A dispute with Thales over contract terms escalated into arbitration. The panel ruled against Globalstar, finding the previous contract was no longer in force, and said Globalstar owed Thales Alenia Space 53 million euros (about $69 million) in contract termination fees. The ruling set off a 30-day clock: pay, or risk Thales stopping work on six nearly completed satellites. Globalstar warned that if that happened, it would be forced to consider “strategic alternatives,” including filing for Chapter 11 protection—again.

A second bankruptcy loomed close enough to touch. Once again, it came down to negotiation under pressure—and Thermo’s willingness to inject more capital. The company was trying to thread a needle in a windstorm, clinging to one urgent belief: if it could just get the next satellites up, the network could stabilize. A successful Globalstar, they said, could be only six new satellites away.

VII. The Wilderness Years: Survival Mode (2013-2019)

With the second-generation constellation finally in place, Globalstar at least had the one thing no scrappy turnaround can fake: real infrastructure in orbit. The problem was that a satellite network isn’t a business by itself. It’s a machine that needs demand.

The consumer dream was still gone. Iridium was marching toward its own next-gen refresh. On the ground, the world kept getting better, cheaper connectivity—especially for the kinds of basic tracking and monitoring Globalstar had leaned on. In the years before Apple, Globalstar looked less like a growth story and more like a company stuck maintaining expensive hardware while the market slowly drifted away.

The stock reflected that reality. It languished. For anyone on the outside looking in, there was no obvious catalyst: revenue stayed essentially flat, profitability remained out of reach, and debt kept eating whatever operating cash flow the business could produce.

But Globalstar did have something that didn’t show up in subscriber counts: spectrum.

The company held FCC-granted licenses in S-band and L-band—frequencies valuable not only for satellite communications, but potentially for terrestrial use as well. The bet, especially from Monroe, was that spectrum could become the company’s real ace card. Globalstar’s spectrum alone could be worth $4.5 billion if the Federal Communications Commission approved a petition to open it for terrestrial purposes. If the FCC ruled in Globalstar’s favor, Monroe believed a major cellular company might partner with Globalstar and license the bandwidth to help offload data from mobile networks straining under the weight of smartphones.

That long-view thesis matched the person driving it.

Jay Monroe served as Executive Chairman of Globalstar’s Board. He had held the Chairman role since Thermo Capital Partners bought Globalstar’s assets in April 2004. He was CEO from January 2005 to July 2009, then returned as CEO from July 2011 until September 2018. He was also the majority owner of Thermo Companies, which he founded in 1984. Under his direction, Thermo founded or acquired businesses across power generation, natural gas exploration and production, industrial equipment distribution, real estate, telecommunications, financial services, and leasing services.

Monroe was a rare kind of investor-operator: in control, unusually patient, and willing to keep writing checks through multiple cycles. That approach also made him extremely wealthy. Bloomberg’s Billionaires Index put his net worth at at least $3.2 billion, though he had never appeared on an international wealth ranking. Monroe also said he had tried—and failed—to get Warren Buffett to invest in Globalstar six years earlier, and joked that his adult children would be surprised to learn how large a fortune he’d amassed.

In 2018, Monroe tried to simplify the corporate structure by folding other Thermo assets into Globalstar. The company announced a merger between Globalstar and Thermo Acquisitions, Inc., an affiliate of Thermo, in exchange for Globalstar common stock valued at approximately $1.645 billion (the “Merger”). On August 1, 2018, Globalstar and Thermo announced they had terminated the Merger by mutual written agreement.

The deal collapsed amid objections from minority shareholders, including hedge fund Mudrick Capital. But the episode was revealing: Globalstar wasn’t just fighting physics and competition. It was also navigating a complicated ownership structure—and the inherent tension between a controlling shareholder’s vision and what minority shareholders would tolerate.

VIII. Inflection Point: The Apple Deal That Changed Everything

The whispers started in 2021: Apple, people said, was working on satellite connectivity for the iPhone. For years, analysts had floated the most dramatic version of that story—Apple building its own constellation. It would be on-brand, and it would be insanely expensive. Instead, Apple did what Apple usually does: it found an existing system it could bend to its will.

By late summer 2022, the speculation got specific. Satellite communications consultant Tim Farrar said Apple was likely about to announce a satellite feature for the iPhone 14—and that the timing of T-Mobile and SpaceX’s own satellite connectivity announcement looked like a pre-emptive strike, meant to steal some of the oxygen before Apple’s reveal. In Farrar’s telling, Apple’s partner was Globalstar.

On September 7, 2022, that reveal arrived. In the U.S. and Canada, iPhone 14 and iPhone 14 Pro users would be able to connect directly to a satellite when they were outside cellular and Wi‑Fi coverage, and message emergency services. The “space” feature Apple unveiled onstage depended, in the real world, on Globalstar—headquartered in Covington, Louisiana, with facilities across the U.S.—and a big build-out of infrastructure to support it.

Apple committed $450 million from its Advanced Manufacturing Fund to develop critical infrastructure for Emergency SOS via satellite, including expanding and enhancing Globalstar ground stations in Alaska, Florida, Hawaii, Nevada, Puerto Rico, and Texas. For a company that had spent years looking like it might never get out from under its own fixed costs, Apple wasn’t just a customer. Apple was a financier.

For Globalstar, the terms made the shift unmistakable. In an SEC filing released during Apple’s “Far Out” event, Globalstar said it planned to allocate 85% of its current and future network capacity to Apple for the service. That is not a partnership in the casual sense. That is a company reorienting around a single, massive demand source.

The system itself was a perfect marriage of Globalstar’s legacy network and Apple’s product obsession. The service uses L- and S-band spectrum designated for mobile satellite services under ITU radio regulations. When an iPhone user initiates an Emergency SOS via satellite request, the message is picked up by one of Globalstar’s 24 low Earth orbit satellites—moving at roughly 16,000 mph—and relayed down to custom ground stations positioned around the world.

Apple’s contribution was the magic trick that made this usable by normal people. The company designed custom algorithms to compress text messages, custom antennas for the iPhone, and an interface that guides users to aim their phones at the right patch of sky. On the ground, the receiving side was upgraded too: Cobham Satcom in Concord, California engineered and manufactured new high-power antennas for the ground stations.

Then, in November 2024, Apple expanded the relationship dramatically. Apple’s deal with Globalstar included $1.1 billion in cash—$232 million earmarked to address Globalstar’s existing debt—and a 20% equity stake. Apple committed about $1.5 billion to Globalstar to fund the expansion of iPhone services. Globalstar, which had been providing emergency connectivity for iPhone models 14, 15, and 16 since 2022, again said it would allocate 85% of its network capacity to Apple as part of the expanded deal.

The math of Globalstar’s survival had flipped. It now had guaranteed demand from the world’s most valuable company, capital to invest in its network, and something it had rarely enjoyed in the public markets: validation. As one analyst put it, “Certainly, this makes Globalstar a sustainable business on the satellite side. The real question is there any more than that.”

IX. The SpaceX/Starlink Factor: Competition and Partnership

Even as Apple gave Globalstar a lifeline, a bigger force was gathering overhead—one that could reset the rules for everyone in satellite communications. SpaceX and T‑Mobile started selling a version of the dream Globalstar originally pitched in the 1990s: your regular phone, anywhere on Earth, no towers required. “The important thing about this is that it means there are no dead zones anywhere in the world for your cell phone,” Elon Musk said. “We’re incredibly excited to do this with T‑Mobile.” The plan was to broadcast from Starlink satellites using T‑Mobile’s mid-band spectrum and stitch satellite coverage into the existing cellular ecosystem.

On January 3, 2024, T‑Mobile announced that SpaceX’s Falcon 9 had launched the first batch of Starlink satellites equipped with Direct to Cell capabilities—livestreamed, of course, like a product launch.

T‑Mobile branded the offering “T‑Satellite,” saying it was powered by more than 650 Starlink Direct to Cell satellites and supported over 60 phone models.

This was a fundamentally different approach from Apple and Globalstar. Globalstar’s iPhone feature depends on Apple’s custom integration: specialized hardware in the phone, bespoke protocols, and a tightly managed user experience that guides you to point the device at the right slice of sky. Starlink’s pitch was the opposite: make the satellite behave like a cell tower, and let existing LTE phones connect without special-purpose satellite gear.

And then there’s the scale. Globalstar operates 31 satellites. SpaceX spent the last year ramping a Direct to Cell constellation of more than 400 satellites, with the ability to build and launch at a tempo legacy operators can’t match. In satellite, cadence is strategy—and SpaceX’s cadence is its moat.

For Globalstar, that creates a new kind of vulnerability. The company is still heavily reliant on Apple, which has invested around $2 billion into Globalstar over the past three years. In its most recent quarterly filing, Globalstar also raised the stakes explicitly, warning for the first time about what happens if Apple ever walks: “The loss of the Customer would likely have a material adverse impact on our financial condition, results of operations and cash flows.”

By late 2025, reports added an extra edge to the threat: SpaceX had allegedly designed newer satellites to support the same radio spectrum Apple uses for the iPhone’s current satellite features—the very service Globalstar provides. If that capability makes it into Starlink’s next-generation constellation in the coming years, SpaceX could potentially offer Apple-compatible satellite connectivity on a platform built for mass scale.

And yet, in the great irony of modern space, Globalstar also became a SpaceX customer.

Globalstar, backed by Apple, purchased launches from SpaceX worth $64 million. Scheduled for 2025, those launches were set to deliver at least 17 new satellites into low Earth orbit to replenish Globalstar’s constellation. Those satellites came from a separate supply chain: Globalstar entered into a $327 million purchase agreement with MDA in February last year, with Rocket Lab subcontracted to supply the spacecraft chassis.

Globalstar also signed an agreement with SpaceX for a Falcon 9 launch for the next set of satellites, tied to the 2022 satellite procurement agreement with MDA.

So the relationship with SpaceX became messy in a very 2020s way. SpaceX sells Globalstar the rides it needs to stay alive, while Starlink builds a competing product that could, over time, encroach on the same use cases—and possibly even the same spectrum. That tension sharpened when SpaceX filed with regulators seeking additional spectrum for Starlink, including portions of spectrum bands that had been used exclusively by Globalstar.

X. The Thermo Capital & James Monroe III Story

No understanding of Globalstar is complete without understanding James Monroe III—the Denver billionaire who kept control of the company through two decades of turmoil, skepticism, and only recently, validation.

Monroe was born in Cincinnati and graduated from Tulane in 1976 with a political science degree. After moving to Denver, he sold industrial equipment for Stewart & Stevenson and then spotted an opening in a newly deregulating energy market: cogeneration plants. His employer didn’t want to own power plants, but it did want to sell the equipment that went into them—and it helped Monroe line up $60 million in financing to build a 76-megawatt plant in Greeley in 1984. He expanded that into four plants, at times generating as much as $4 million a month in revenue. Along the way he invested in residential real estate and commercial finance, and brought on James Lynch—a Kidder Peabody banker involved in the energy financing deals—as a partner.

Out of that industrial playbook came a simple investing lens. “We look for three things: a change in technology, a change in regulation and a trend,” Lynch said, describing their approach.

Telecom checked the boxes. The partners started buying fiber-optic assets in high-population areas, betting that fears of excess supply were overstated. They sold one of those businesses, Xspedius Communications, to TW Telecom for $533 million. Monroe later bought back an unprofitable piece of Xspedius and renamed it Fiberlight. “It’s a massive system, and the sellers didn’t want it for some of the dumbest reasons you can imagine,” Monroe said. “So we paid a few million dollars for it. That business is printing money.” Fiberlight grew into a major network, with 1.5 million miles of cable and an enterprise value of $1 billion.

Globalstar was the same thesis pointed at space: infrastructure assets selling for a fraction of what they’d cost to replace, protected by a regulatory moat in the form of spectrum licenses, sitting in an industry where technology shifts could eventually make the asset matter again. The difference was the clock. Fiber proved itself in years. Globalstar took decades.

And Monroe didn’t just hold on—he kept leaning in. In a recent SEC filing, Monroe disclosed that on December 13 he purchased 500,000 shares of Globalstar’s voting common stock at a volume-weighted average price of about $1.995 per share, for a total of $997,500. The purchase came after the stock had gained roughly 80% over the prior six months.

For someone who has controlled the company for more than twenty years, continuing to buy in the open market is a very specific kind of statement: he still thinks the story isn’t finished.

XI. Technology & Operations Deep Dive

To understand what Globalstar can and can’t be, you have to understand the machine it’s running in orbit—and the trade-offs baked into it from day one.

Globalstar’s satellites fly in low Earth orbit at around 1,414 kilometers up. That’s close, in space terms—especially compared to geostationary satellites, which sit way out at 35,786 kilometers. The payoff is latency. LEO systems avoid the noticeable half-second delay that geostationary users have learned to live with.

But there’s no free lunch. Being closer to Earth also means each satellite “sees” less of the planet at any moment. A geostationary satellite can cover about a third of the world; a single LEO satellite covers only a small slice. So LEO gives you responsiveness, but it forces you into constellations and careful choreography.

Then there’s Globalstar’s biggest design decision: it’s a bent-pipe network. The satellites don’t do much thinking up there. They act like relays, passing signals down to Earth without processing them in space. Iridium went the other way, building inter-satellite links and routing calls through space. That complexity is expensive, but it’s what enables true global coverage—including over oceans and poles.

Globalstar’s approach is simpler and cheaper, but it comes with a constraint that never goes away: for two-way voice and duplex data, you don’t just need a satellite overhead. You also need that satellite to be able to “see” a ground station it can connect to. No ground station in range, no connection. That makes truly global coverage problematic, if not impossible—think Antarctica, or the middle of the Atlantic.

Once you understand that, a lot of Globalstar’s history snaps into focus. Coverage isn’t just about where the satellites go. It’s about where the gateways are. Globalstar provides service across North America, parts of South America, Europe, and limited areas in Africa and Asia. It’s not global, but within that footprint it can be a cost-effective option for customers who operate there.

For Apple, that’s a feature, not a bug—at least at the start. The iPhone rollout in the U.S. and Canada maps neatly onto Globalstar’s existing ground infrastructure. The flip side is that scaling internationally isn’t only a satellites question. It’s also a ground build-out question, and that means more capital, more permitting, and more time.

If Globalstar has a true defensible asset, it isn’t the satellites. It’s the spectrum. The iPhone feature runs over mobile satellite services spectrum that Globalstar has operated in the U.S. for the past two decades. Those licenses come from the FCC and are coordinated internationally through the ITU, and they’re not something a competitor can simply recreate.

That’s why one regulatory decision mattered so much. In August 2024, the FCC reauthorized Globalstar’s HIBLEO-4 constellation for another 15 years. It didn’t just extend the runway; it also permitted the deployment of up to 26 replacement satellites and reaffirmed Globalstar’s exclusive rights to its licensed spectrum.

And in a business where physics is unforgiving, having your legal foundation secured for the next decade-plus isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s survival.

XII. Business Model Evolution & Unit Economics

Globalstar’s transformation from a failed consumer satellite phone operator into infrastructure for Apple didn’t just change the company’s narrative. It rewired the business model.

In 2024, Globalstar reported record revenue of $250.3 million, up 12% year over year. It also posted record annual service revenue in Commercial IoT, up 15% from the prior year—evidence that the legacy business lines didn’t disappear, but they also didn’t become the main event.

That main event is wholesale capacity. In practice, that means Apple. Globalstar’s revenue mix now tells a very different story than it did a decade ago: Apple-driven capacity services dominate; older voice services keep fading; IoT grows, but at a smaller scale. And with Apple reserving 85% of Globalstar’s network capacity for satellite messaging, Globalstar is no longer trying to “go find” demand. It’s building around demand that already showed up.

The financing structure matters even more than the product story. Apple is reimbursing Globalstar for 95% of the capital expenditures tied to the satellites, including launch costs. Apple also agreed to provide $252 million toward upfront costs to replenish the constellation, along with funding to improve Globalstar’s ground station network.

This is the inversion of the classic satellite-company gamble. Traditionally, an operator raises huge sums first, launches hardware, and then prays that customers arrive in time to pay for it. Globalstar now has its biggest customer effectively underwriting the rebuild. That customer-funded capex model reduces Globalstar’s existential risk and gives it room to invest elsewhere, including work toward its next-gen C-3 constellation.

Financially, you can see the shape of this new model in the income statement. Even with a net loss of $63.2 million in 2024, Globalstar reported record Adjusted EBITDA of $135.3 million, up from $116.7 million in 2023. The company also said it received $0.9 billion of a total $1.7 billion investment under the Updated Services Agreements.

Looking ahead, Globalstar has said it expects revenue to more than double to over $495 million, with Adjusted EBITDA margins in excess of 54% in the first full year of extended MSS network service.

The catch is that EBITDA isn’t the same thing as profits. Even with record revenue and improving operating performance, Globalstar still has to climb out from under interest expense, depreciation, and one-time charges. So the path to profitability remains real work. But the direction of travel has changed: more contracted revenue, stronger margins, and a capital plan that’s finally being financed by the party that needs the network to exist.

XIII. Strategic Analysis: Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH

For most of satellite communications history, the barriers to entry were almost self-policing. You needed billions in upfront capital, deep aerospace talent, and the patience to fight your way through years of spectrum and licensing work before you could even sell your first minute or message.

SpaceX changed that. Launch became cheaper and more predictable, and the broader market shifted too: better technology, new business models, deeper pools of funding, and much higher demand for low-latency connectivity. In other words, today looks nothing like the 1990s, when grand LEO telecom concepts collapsed under their own weight. Big constellations are no longer automatically “crazy.” They’re increasingly normal.

Regulation still matters—Globalstar’s FCC licenses aren’t something a new competitor can copy-paste—but that protection is real without being absolute.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Globalstar still has to buy from a relatively small club. Satellite manufacturing remains concentrated among players like Thales Alenia Space, Airbus Defence and Space, MDA, Boeing, and Lockheed Martin, though newer entrants like Rocket Lab are widening the field. For Globalstar’s replenishment plan, the satellites built by MDA with Rocket Lab supplying the spacecraft chassis are designed to operate in a Walker 32 configuration, improving coverage and reliability.

On launch, the market has flipped from bottleneck to advantage. SpaceX’s Falcon 9 has made reliable access to orbit more available, and at lower cost than the old days—exactly the kind of shift that can loosen supplier leverage.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

This is the heart of Globalstar’s strategic risk, and it’s not subtle.

Globalstar has been providing emergency connectivity for iPhone models 14, 15, and 16 since 2022. Under the expanded arrangement, Globalstar will allocate 85% of its network capacity to Apple. When one customer consumes most of your capacity and represents the bulk of your revenue, that customer doesn’t just negotiate hard—they set the rules.

Apple’s 20% equity stake and multi-year commitments do create some stickiness. But the power dynamic is still clear: Apple holds the leverage, and Globalstar lives with that reality.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

The most obvious substitute is the one that made Globalstar’s first act so painful: terrestrial networks keep spreading. While more than half of the world’s land mass remains uncovered by terrestrial service, Globalstar’s core markets are the developed regions where coverage keeps improving and the “no signal” zones keep shrinking.

Then there are the space-based substitutes. Starlink, Iridium, and AST SpaceMobile each represent different technical paths to similar outcomes. The real question isn’t whether alternatives exist—it’s whether satellite-to-smartphone connectivity becomes a commodity feature, or whether early integration (and the infrastructure built around it) creates meaningful switching costs.

Competitive Rivalry: INCREASING

This industry used to feel like a quiet club of legacy operators. That era is over.

Iridium has partnered with Qualcomm to bring satellite connectivity to Android devices. AST SpaceMobile and Lynk Global are pushing direct-to-smartphone approaches. And Starlink—backed by SpaceX’s manufacturing and launch velocity—has announced direct-to-cell plans with T-Mobile. The competitive set is getting larger, better funded, and more ambitious, which is exactly what you don’t want when your business is still defined by fixed costs and a single dominant customer.

XIV. Strategic Analysis: Hamilton's Seven Powers

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

Satellite networks are the definition of fixed-cost businesses. Once the constellation is up and running, serving one more user is relatively cheap. The catch is the brutal minimum scale you need before those economics start working in your favor. Apple effectively gives Globalstar that scale—but it’s a concentrated kind of scale, because it’s coming from one buyer.

2. Network Effects: WEAK

This isn’t a social network. A million more users don’t make the service meaningfully better for existing users. The value doesn’t compound; it just adds up.

3. Counter-Positioning: WEAK

Counter-positioning is when an incumbent can’t respond to a challenger without wrecking its own business model. That’s not really what’s happening here. The more relevant asymmetry is that SpaceX can walk into Globalstar’s world with manufacturing and launch leverage Globalstar simply can’t match—and Globalstar can’t “catch up” by copying SpaceX’s cadence or Starlink’s scale.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE-HIGH (for Apple)

Apple has put real effort and capital into making Globalstar work: custom hardware choices in the phone, bespoke protocols, upgraded ground equipment. That creates switching costs that are real, not theoretical. But they’re not permanent. Over a three-to-five-year horizon, Apple could still decide to build a new relationship—or a new solution—if it thought the trade-offs were worth it.

5. Branding: WEAK

Almost nobody knows Globalstar is involved. The customer-facing brand is Apple, full stop. In Globalstar’s legacy enterprise lines, customers aren’t paying for a logo—they’re paying for reliability.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE-HIGH

This is the core of the whole thing. Globalstar’s FCC-granted spectrum licenses are scarce, regulated, and difficult to replicate. That’s why the FCC’s August 2024 decision to reauthorize Globalstar’s HIBLEO-4 constellation for another 15 years mattered so much: it allowed up to 26 replacement satellites and reaffirmed Globalstar’s exclusive rights to its licensed spectrum.

And now there’s a second cornered resource layered on top: the Apple partnership itself. Competitors can build satellites, but they can’t easily recreate Apple’s integration work, operating model, and capacity commitment—at least not overnight.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

Globalstar has been running constellations, ground stations, and regulatory relationships for decades. That institutional knowledge is valuable, but it isn’t unique in this industry—Iridium and Inmarsat/Viasat have their own versions of it too.

Key Takeaway: Globalstar’s moat is narrow. It’s mainly spectrum plus the Apple partnership. And the durability of that position depends on forces Globalstar doesn’t fully control: what Apple decides to do next, how direct-to-device competition evolves, and whether regulators keep the rules stable.

XV. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case:

The optimistic view is that Globalstar has finally become what it always wanted to be: essential infrastructure riding a real, durable wave. Direct-to-device satellite connectivity is moving from sci‑fi demo to table-stakes smartphone feature. Apple helped make it mainstream, and the rest of the industry is now sprinting in the same direction. In that world, Globalstar’s real advantage isn’t flash—it’s permission and plumbing: spectrum licenses, an operating network, and years of hard-won integration work that new entrants can’t simply spin up on a whim.

“We definitely see this as a success story,” CEO David Kagan said.

Apple’s expanded commitment—$1.5 billion and a 20% equity stake—reads, to bulls, less like a vendor contract and more like a strategic alignment. The SpaceX launch agreement helps de-risk the next round of satellites. And government contracts in defense and emergency services offer at least some diversification beyond consumer-adjacent messaging.

The financial trend line, in this telling, finally matches the narrative. In Q3 2024, Globalstar reported revenue of $72.3 million, up 25% year over year, driven by wholesale capacity, government contracts, and IoT solutions. Adjusted EBITDA reached $42.8 million, up 34%. Management raised 2024 revenue guidance to $245–250 million and pointed to a targeted 54% EBITDA margin—signals that this isn’t just a one-quarter pop, but a business model that may actually scale.

Bulls argue the stock still doesn’t fully reflect what Globalstar now owns and has locked in: operating satellites, valuable spectrum, and contracted demand anchored by Apple. And hovering over everything is the most speculative upside: if satellite connectivity becomes a core iPhone pillar, an Apple acquisition at a premium starts to feel less like fan fiction and more like a plausible endgame.

The Bear Case:

The pessimistic view starts with the simplest problem in the whole story: Globalstar is still a one-customer company in disguise.

Yes, Apple rescued the business. But the rescue came with a leash. Globalstar remains heavily dependent on Apple, which has invested around $2 billion into the company over the past three years. And Globalstar itself has now put the risk in writing. In its most recent quarterly earnings filing, it warned for the first time: “The loss of the Customer would likely have a material adverse impact on our financial condition, results of operations and cash flows.”

Bears also point out that improved operating metrics haven’t yet translated into GAAP profitability. Even with record revenue, Globalstar still reported a net loss of $63.2 million for the year, driven largely by non-operating items like a loss on extinguishment of debt and foreign currency loss. In other words, the income statement is still reminding everyone what kind of business this is: capital-intensive, financially complex, and not easily forgiven by accounting.

Then there’s the technology and competitive threat. Starlink’s Direct to Cell approach is a different paradigm—make the satellite act like a cell tower—and it’s being scaled by a company with unmatched manufacturing and launch velocity. SpaceX has also added support in newer satellite designs for the same radio spectrum Apple uses for the iPhone’s current satellite features. If that carries through into Starlink’s next-generation constellation, it raises an uncomfortable possibility: Starlink could eventually offer Apple-compatible satellite connectivity at a scale Globalstar can’t match.

And if Apple ever decides to diversify—or negotiate harder, or switch partners—the whole structure wobbles. Globalstar’s history doesn’t exactly reassure skeptics here. Two bankruptcies are a loud reminder that, in this business, operational progress can still get overwhelmed by the combination of physics, capital costs, and timing.

What to Watch:

For Globalstar, almost everything important flows through two questions.

First: is wholesale capacity revenue actually compounding, or just stepping up because of one partner’s launch schedule? Second: is customer concentration getting better, or worse? In practice, that means watching Wholesale Capacity revenue growth alongside the Customer Concentration ratio. If the first rises while the second falls, Globalstar starts to look like a platform. If the first rises while the second stays pinned, it’s still a bet on one relationship—no matter how big the checks are.

XVI. Epilogue: Lessons & Reflections

Globalstar’s story is fascinating partly because it refuses to resolve cleanly. It offers a handful of lessons that are as useful as they are uncomfortable.

Patient Capital Can Pay Off—But Most Won’t Wait 25 Years. James Monroe acquired Globalstar in 2004 and has controlled it ever since. The Apple deal ultimately validated the core bet, but the timeline was punishing. Two decades is an eternity in markets, and very few investors have the mandate, temperament, or governance to keep funding a capital-intensive business through multiple near-death cycles.

Technology Timing Risk is Real. The original Globalstar backers weren’t wrong about the world wanting ubiquitous connectivity. They were early—fatally early. In businesses where you have to spend billions before you can learn whether demand really exists, “early” often looks identical to “wrong.”

The Power of Partnerships Can Be Double-Edged. Apple didn’t just give Globalstar a growth story; it gave it a reason to exist. The flip side is obvious: the rescue came with concentration risk. Globalstar’s future is now tied tightly to decisions made in Cupertino, not Covington.

Capital Structure Matters More Than Strategy. Globalstar’s collapses weren’t only about product-market fit. They were also about financing. Too much leverage, too little cash flow, and no room for delays or bad luck. The assets still had value, but the corporate wrapper failed. Equity got crushed. Creditors recovered a fraction. Monroe’s key insight was that you could buy real infrastructure for pennies—if you had the stomach to wait and the control to endure.

Hidden Optionality Can Stay Hidden for a Long Time. Globalstar’s spectrum mattered long before the market treated it like a strategic resource. The humbling lesson is that embedded optionality—especially in stranded assets—can take far longer to surface than any neat investment memo would suggest.

Regulatory Moats Are Real—But Not Absolute. Licenses and spectrum rights create genuine barriers. They also aren’t force fields. Technology shifts, new policy approaches, and competitors with different architectures can route around what once looked like protection. Globalstar’s spectrum helps in some fights and does little in others.

The Ultimate Question: Was this good business or just good luck? Thermo’s conviction, Monroe’s persistence, and Apple’s strategic choice all had to line up. If any one of those variables changes, the ending changes too. The most honest answer is probably that it was both: good business in recognizing undervalued assets, and good luck in the timing of when the world finally needed what Globalstar already had in orbit.

For long-term investors looking at Globalstar now, the real question isn’t whether the Apple relationship is valuable. It is. The question is whether it becomes a durable position or a temporary reprieve. The partnership has real weight, but it isn’t eternal. Globalstar’s job is to use this moment—this rare window of validation and capital—to build additional revenue streams, broaden its customer base, and harden itself against the next competitive wave.

And overhead, the satellites keep moving—about 1,400 kilometers above us—silent, indifferent, and expensive. Whether they’re finally the foundation of a lasting business, or just the most sophisticated assets ever to wait for the next restructuring, is still the question Globalstar has been asking for three decades.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music