Gulfport Energy: From Gulf Waters to Shale Gas Giant

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s November 2020. David Wood, CEO of a small Oklahoma City oil and gas company, is getting ready to file paperwork that will effectively wipe out shareholders. Just a few years earlier, Gulfport Energy was being talked about like a shale success story. Now, with COVID crushing demand and commodity prices stuck in the mud, Gulfport is staring down Chapter 11—one more name in a long line of once-promising producers headed to restructuring court.

And yet, that’s not the end of the story. In the company’s own words at the time, “Gulfport is emerging from its successful restructuring having materially improved its balance sheet and midstream cost structure, which leaves Gulfport well-positioned for future success.” Less than two years after its darkest moment, Gulfport would come out the other side leaner, more focused, and fundamentally different.

That reinvention is what makes Gulfport worth studying.

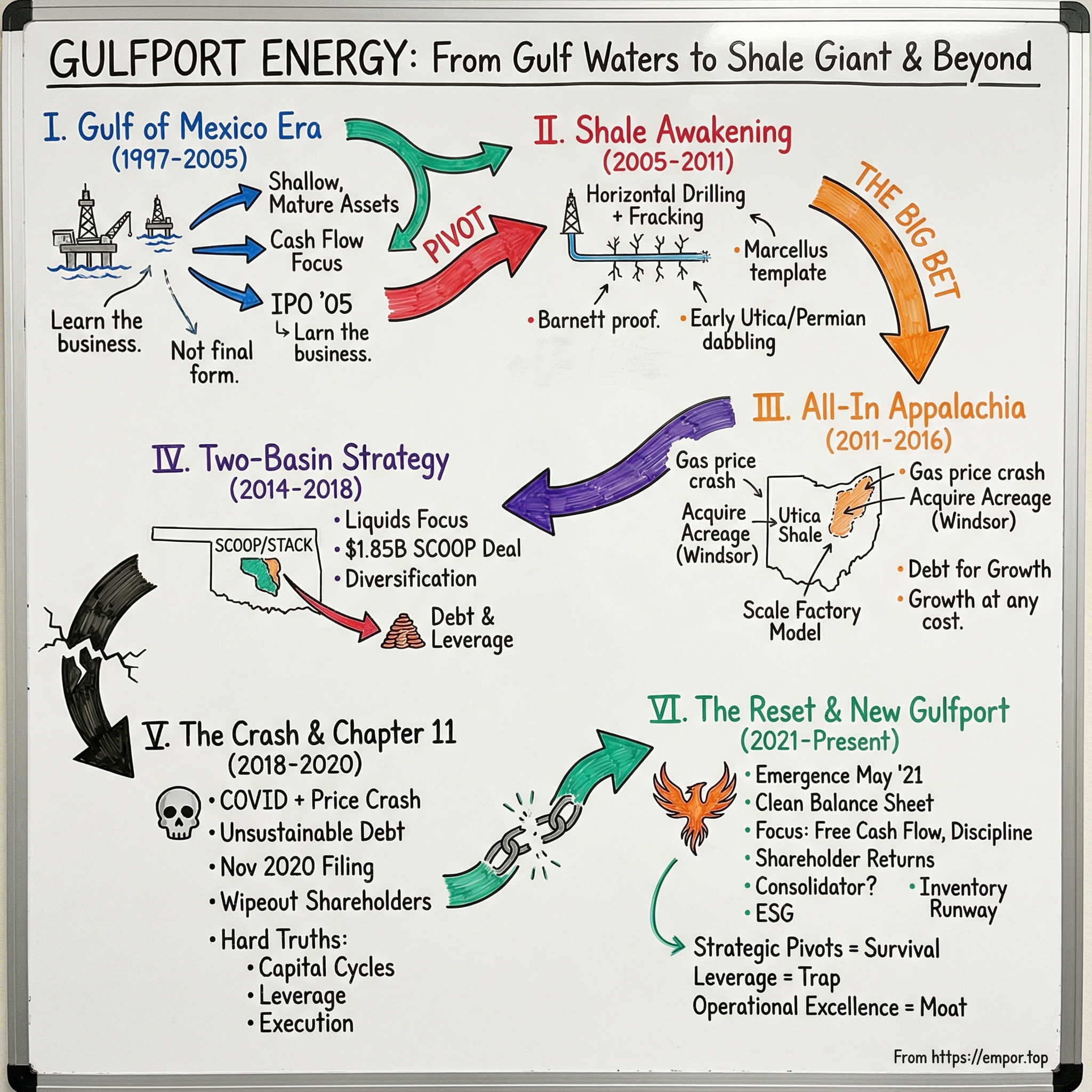

While the corporate lineage traces back to an entity founded in 1985, the current Gulfport Energy Corporation was formed in July 1997. What followed was a quarter-century of pivots so sharp they changed the company’s identity multiple times: from shallow Gulf of Mexico offshore wells, to the deep shales of Appalachia, to a two-basin strategy, to a debt crisis, to a post-bankruptcy reset.

At the time of this story, Gulfport was an independent, natural gas-weighted exploration and production company operating primarily in the Appalachia and Anadarko basins. Its core properties were in eastern Ohio, targeting the Utica and Marcellus formations, and in central Oklahoma, targeting the SCOOP Woodford and SCOOP Springer formations.

So here’s the question that drives this entire episode: how did a small offshore Gulf of Mexico operator transform into a major Appalachian shale player, survive bankruptcy, and then reinvent itself as a modern E&P consolidator?

The answer runs through six defining inflection points—and along the way, it teaches the hard truths of commodity businesses: capital cycles matter, leverage is unforgiving, and the only real edge is execution.

For investors, Gulfport is a rare kind of case study. Over its life, it’s been both predator and prey—aggressive acquirer and distressed restructuring candidate. Understanding how it swung between those extremes is a window into what separates the survivors from the casualties in America’s most volatile industry.

II. Founding & Early Years: The Gulf of Mexico Era (1997–2005)

Before Gulfport bet the company on Appalachian shale, it was exactly what its name suggested: a Gulf Coast operator built around a very specific kind of oil-and-gas hustle.

Gulfport Energy was formed in July 1997. It started with a patchwork of initial assets—properties from WRT Energy and a 50% working interest in the West Cote Blanche Bay (WCBB) field contributed by DLB Oil and Gas. WCBB wasn’t a flashy new discovery. It was a mature salt-dome complex in Louisiana’s coastal marshes, the sort of long-producing field that small E&Ps in the late ’90s lived on: known geology, steady production, and lots of room for operational tightening.

From the beginning, Mike Liddell was central to the story. He served as a director starting in July 1997 and became chairman in July 1998. Liddell wasn’t selling a moonshot. The playbook was pragmatic: buy mature, undervalued offshore and coastal assets, then work them harder and smarter—low-risk development, incremental improvements, and a focus on cash flow.

Over the next several years, Gulfport sold off a number of assets, simplifying the portfolio and leaving a cleaner balance sheet and a tighter focus. The company leaned into low-risk development work, largely centered on WCBB. While bigger Gulf of Mexico players chased higher-risk exploration—especially as the deepwater era heated up—Gulfport stayed shallow. It wasn’t glamorous. It was disciplined.

Then came the move that would set up everything that followed: going public in 2005, via a reverse merger—classic small-cap E&P mechanics. Public markets meant capital, and in the mid-2000s energy was in vogue. Oil prices were rising, and investors were eager to fund upstream growth stories.

That same year, Gulfport handed the CEO seat to a new operator. On December 1, 2005, James D. “Jim” Palm joined as Chief Executive Officer, replacing Mike Liddell in the role. Liddell stayed on as chairman and a director. Palm brought an engineering-and-business background—he earned a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering in 1968 and an MBA in 1971, both from Oklahoma State University—and he’d spent early years at Gulf Oil Corporation in Pittsburgh after serving three years as a Naval Officer. More importantly, he’d already built an independent E&P himself: in 1995, he founded Crescent Exploration, L.L.C., operating in Oklahoma and the Texas panhandle.

On paper, Gulfport at this point was still a Louisiana Gulf Coast E&P. But the limits of that identity were already showing. The Gulf of Mexico was getting tougher for small operators: capital requirements kept rising, hurricanes were an ever-present threat, and many of the best opportunities increasingly demanded scale Gulfport didn’t have.

The key takeaway from this era is that “Gulfport” was never meant to be the final form of the company. These years were about learning the business, generating cash flow, and building the platform. The name would stick—but the strategy, the geography, and eventually the entire identity of the company were about to change.

III. The Shale Revolution Awakening: Pivot to Onshore (2005–2011)

To understand what happened to Gulfport after 2005, you have to zoom out. The entire U.S. oil and gas industry was in the middle of a quiet technological coup—and it started, fittingly, in the unlikely place that became Ground Zero: the Barnett Shale in North Texas.

This is where George Mitchell and Mitchell Energy proved that shale wasn’t just a source rock. With the right recipe, it could be a reservoir. The breakthrough wasn’t one invention so much as a winning combination: hydraulic fracturing, paired with horizontal drilling.

Fracking sounds simple in hindsight. Pump huge volumes of water mixed with sand and chemicals into tight rock at high pressure, crack it open, and let the sand hold those fractures wide enough for gas to flow. But making it work reliably—and economically—took years of trial and error. By the late 1990s, Mitchell’s team had cracked the cost curve. Then the industry did what it always does when a play works: it copied it, improved it, and scaled it.

The Barnett was the proof. The next step was the template. In 2005, horizontal drilling tipped from “interesting” to “dominant” in the Barnett. Within a few years, almost every new well was drilled that way. Shale gas production surged after 2008, flipping the script on decades of decline and turning the U.S. from a country planning for LNG imports into the world’s biggest natural gas producer.

From Gulfport’s perspective, sitting on legacy Gulf Coast assets, that shift wasn’t academic. It was existential.

Because if shale was the future, the Gulf of Mexico looked like the past. Offshore was capital-intensive, exposed to hurricanes, and increasingly a game for bigger balance sheets—especially as the industry pushed into deeper and deeper water. And after major storms highlighted how fragile offshore infrastructure could be, the regulatory backdrop was tightening too.

Meanwhile, the onshore shale basins were proving something seductive: repeatability. Once you had acreage and a technical playbook, you could scale drilling like a manufacturing process.

The Marcellus in Appalachia was a perfect example. The formation had been known for ages, and some of the earliest gas wells in the U.S. were drilled there. But modern, high-volume production didn’t really arrive until horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing made it economic. Today, virtually all Marcellus production comes from horizontal wells—a signal to every management team in the business that the “how” mattered as much as the “where.”

Gulfport started to move. Not in one clean leap, but in a series of probes—small bets across multiple basins to see what might become the next core.

As Mike Liddell later put it: "While we started as a southern Louisiana pure play, over the past several years Gulfport has made a series of investments in a number of emerging oil plays. From the Canadian oil sands to the Permian Basin of West Texas to the Utica Shale of eastern Ohio, we are growing into some exciting new areas."

He also framed the company’s commodity preference in blunt terms: "Gulfport went long oil 10 years ago, and today our assets and production are comprised of over 95 percent oil. We do not dislike natural gas, but we feel that oil is a much more valuable and flexible commodity — and the industry seems to agree as it is shifting in this direction."

So Gulfport dabbled widely. It picked up exposure in the Permian. It invested in Canadian oil sands through Grizzly Oil Sands. And it began looking seriously at the Utica—early, before it became a household name in energy circles.

But this kind of reinvention isn’t cheap. Gulfport was trying to transform itself from a steady, mature-asset operator into a growth-oriented shale company. Its existing cash flows weren’t enough to fund that shift at speed, so it leaned on the public markets—raising equity, and diluting shareholders, to buy time and buy acreage. It was a conscious trade: accept dilution now, or risk being locked out of the best rock forever.

By 2011, the identity shift was real. Gulfport still carried a Gulf Coast name, but the center of gravity was moving inland. The old offshore-era assets were no longer the story—they were the origin. And the defining bet, the one that would remake Gulfport completely, was now close enough to touch.

IV. The Utica Shale Bet: All-In on Appalachia (2011–2016)

If the shale revolution was a poker game, Gulfport’s 2011 move into the Utica Shale was the moment it pushed its chips to the center of the table. Not because the company was already huge there—it wasn’t—but because what came next would define Gulfport’s identity for the better part of a decade.

The first step was meaningful, but still measured. In 2011, Gulfport secured commitments totaling about 50,000 gross acres, or roughly 25,000 net, in eastern Ohio’s Utica Shale, with the potential to expand those commitments to more than 80,000 gross acres in short order. Gulfport was designated operator on the acreage, and by June 30, 2011 it had already acquired leasehold interests in approximately 33,000 gross acres (16,500 net) for about $37.9 million.

Then the land grab started in earnest.

The appeal of the Utica was straightforward: thick, hydrocarbon-rich rock across eastern Ohio, positioned close to premium Northeast markets that were hungry for supply. And, crucially, the Utica sat beneath the better-known Marcellus—meaning the same surface footprint could potentially unlock multiple productive zones.

Gulfport went hard. The company accumulated approximately 208,000 net reservoir acres primarily across Belmont, Harrison, Jefferson, and Monroe Counties, where the Utica could run 600 to more than 750 feet thick. The Marcellus overlays the Utica, and Gulfport identified about 20,500 net reservoir acres within its leasehold that it believed could be developed for the Marcellus as well.

The biggest single step-change came in December 2012. Gulfport announced a proposed acquisition of additional Utica working interests, entering a definitive agreement to buy roughly 30,000 net acres from Windsor Ohio LLC—an affiliate of Wexford Capital LP—for approximately $300 million. That deal would lift Gulfport’s Utica position to about 137,000 gross acres, or approximately 99,000 net.

Days later, the price tag grew. As of December 20, 2012, the parties amended the agreement to add approximately 7,000 more net acres for about $70 million, bringing the total purchase price to roughly $370 million.

And this is where the story gets messier. Gulfport repeatedly bought Utica acreage from Windsor Ohio, whose operating member was Mike Liddell—Gulfport’s chairman. These related-party transactions attracted scrutiny from analysts and investors, who questioned whether shareholders were paying fair prices for acreage controlled by an insider.

By then, Gulfport was no longer a curious newcomer. Before these deals, company records showed it had about 147,350 net acres under lease in the Utica—making it the seventh-largest landholder across the play. In Ohio specifically, Gulfport was the second-largest operator, behind only Chesapeake Energy.

And Gulfport still wasn’t done. The company had built much of its southeast Ohio position by buying from conventional drillers, and in the third quarter of 2013 it said it had acquired another 9,000 gross acres—with no plans to stop. It had budgeted roughly $225 million to $275 million for additional Utica leasehold acquisitions.

Of course, owning the land was only the beginning. The Utica was technically demanding. Wells were deep—often more than 10,000 feet—and high-pressure, requiring specialized equipment and careful execution. Then there was midstream: early on, Ohio’s pipelines and processing capacity weren’t ready for a modern shale surge. Bottlenecks could choke production, forcing operators like Gulfport to rely on new gathering lines, processing plants, and takeaway capacity that had to be built in parallel with drilling.

While Gulfport was building this Appalachian machine, it was also monetizing pieces of its earlier onshore experimentation. In 2012, the company initiated drilling to start developing the Utica—while contributing its Permian Basin interests into the Diamondback Energy, Inc. IPO.

The structure worked like this: Diamondback would acquire all the outstanding equity interests in Windsor Permian LLC, an affiliate of Gulfport, for $64 million in debt plus an equity interest in Diamondback. Gulfport would own 35% of Diamondback’s outstanding common stock immediately prior to the IPO close.

The Diamondback IPO closed on October 17, 2012. On that date, Diamondback repaid its note to Gulfport in connection with Gulfport’s contribution of its Permian oil and gas interests.

In effect, Gulfport swapped a Permian position for a stake in what would become one of the defining Permian pure-play success stories—creating a source of liquidity it could monetize over time to help fund its Utica buildout.

Operationally, the 2012–2016 stretch was when shale’s “factory model” fully took over. The business shifted from one-off exploration to repeatable manufacturing: pad drilling, standardized completions, and scale economics. Gulfport leaned into that model as its Ohio operations matured, working to bring down well costs and cycle times.

But the macro backdrop turned brutal. Natural gas prices collapsed—Henry Hub fell from the highs of the late 2000s to levels below $2 by 2016. The same shale boom that made the Utica possible also flooded the market with supply and crushed returns for gas-heavy producers. Gulfport kept pushing forward anyway, betting that execution and efficiency could carry the day in a depressed price environment.

That bet would take years to play out. And it wouldn’t be a clean win.

V. The SCOOP/STACK Expansion: Building a Two-Basin Strategy (2014–2018)

By the mid-2010s, Gulfport had done the hard part in the Utica: it had secured premier acreage and built an operating machine. The problem was the commodity itself. Natural gas prices stayed weak, and there was no guarantee that “just drill better” would fix the economics.

So management went looking for a counterweight—another basin, another product mix, more liquids. Something that could soften the blow of living and dying by gas.

That search led them back to Oklahoma, into the Anadarko Basin, and into a new shale story that was getting louder every quarter: the SCOOP, the South Central Oklahoma Oil Province.

Continental Resources had helped put the SCOOP on the map in 2012, pitching the SCOOP/Woodford as an oil and liquids-rich province with unusually thick, high-quality resource shale. Nearby sat the STACK—another Anadarko darling—adjacent to and northeast of the SCOOP. The two plays shared geology, infrastructure, and the same basic promise: repeatable, manufacturing-style drilling, but with a better chance of getting paid in liquids.

Geologically, the appeal was “stacked pay.” The Anadarko wasn’t just one target; it was layers. The SCOOP included familiar formations like the Hunton and the Woodford, plus the Caney, Hoxbar, and Springer. The Woodford was the legacy workhorse, but Continental’s identification of the Springer in 2014 added another runway—more rock to drill, more inventory to monetize.

Gulfport made its move on December 14, 2016. The company announced a definitive agreement with Vitruvian II Woodford, LLC, a Quantum Energy Partners portfolio company, to acquire approximately 46,400 net surface acres in the core of the SCOOP. The deal also came with around 183 MMcfe per day of net production (as of October 2016). Total price: $1.85 billion.

It was, by far, Gulfport’s largest acquisition—and it was a statement. This wasn’t a toe in the water. It was a bet that a liquids-leaning Anadarko position could balance out the company’s gas-heavy Utica exposure and give Gulfport a second engine.

The acquisition created a substantially contiguous position totaling roughly 85,000 net effective acres, including rights to 46,400 Woodford acres and 38,600 Springer acres, across Grady, Stephens, and Garvin Counties. About 80% was held by production, meaning Gulfport wasn’t staring down an immediate “drill it or lose it” clock. The company framed the opportunity as deep inventory—approximately 1,750 gross drilling locations, including more than 775 gross locations with internal rates of return of approximately 75%.

CEO Michael G. Moore put it plainly: "Today is a defining day for Gulfport Energy. Combining Vitruvian's high-quality SCOOP position with our prolific Utica assets will transform our company and solidify Gulfport with core positions in two of North America's high-return natural gas basins."

The structure of the deal showed just how big this was for Gulfport. The $1.85 billion consideration included $1.35 billion in cash plus roughly 18.8 million shares of Gulfport stock issued to the sellers in a private placement. To come up with the cash, the company planned to rely on financing—debt and potentially equity—before closing.

On paper, the logic was hard to argue with. Gulfport already knew how to operate shale at scale. Now it would apply that playbook in a basin that offered more liquids and a different set of returns. And the SCOOP had operational quirks operators liked—Continental, for one, highlighted that STACK and SCOOP wells tended to produce very little formation water, which mattered because water handling is one of the most expensive, unglamorous frictions in shale.

Over the next couple of years, Gulfport built out that Oklahoma footprint. The company accumulated about 73,000 net reservoir acres across the Woodford and Springer, largely in Garvin, Grady, and Stephens Counties, targeting formations that ranged from Devonian to Mississippian age, including the Woodford, Sycamore, and Springer.

By 2018, Gulfport could credibly call itself a two-basin operator. It had a major Utica position and a rapidly scaled SCOOP position. As of the end of the third quarter of 2018, Gulfport reported producing more than 1.4 Bcfe per day, with about 20% coming from the SCOOP. Even then, the company was still largely a gas story—only about 10% of production was liquids—but the direction of travel was clear: more diversification, more optionality.

But the pivot came with a hidden fuse.

Because transforming a one-basin shale company into a two-basin shale company doesn’t just require geology and engineers. It requires capital. And for Gulfport, the SCOOP expansion was financed the way shale growth so often was in that era: with leverage.

That debt would soon stop feeling like a tool—and start feeling like a trap.

VI. The Debt-Fueled Growth Trap & Financial Crisis (2018–2020)

From 2018 to 2020, Gulfport ran headfirst into the oldest trap in shale: chasing growth without building a business that could survive a down cycle. For years, production was the headline metric. Returns were the footnote. And eventually, the footnote became the story.

The backdrop mattered. Over the 2010s, the U.S. became a powerhouse oil and gas producer in large part because capital was abundant. Shale promised repeatable drilling and rapid growth, and Wall Street was happy to fund it. Companies with strong balance sheets borrowed conventionally. Smaller independents often leaned on the junk bond market. Either way, the industry’s expansion was built on cheap money and the assumption that prices would cooperate.

Then investor sentiment flipped. After years of rewarding “growth at any cost,” markets started demanding something much harder: free cash flow, restraint, and returns to shareholders. Prices stayed weak, the economy rolled into a cyclical slowdown, and upstream bankruptcies began stacking up. For companies that had loaded up on debt to fund expansion, the math turned ugly fast—large interest bills paired with shrinking revenue.

Gulfport felt that squeeze before the pandemic ever hit. In August 2020, under pressure from activist investor Firefly Value Partners to change its board, the company warned it might not be able to stay afloat without refinancing its debt.

Then COVID-19 arrived and turned stress into crisis.

On November 13, 2020, Gulfport Energy Corp. filed a Chapter 11 petition in U.S. Bankruptcy Court in Houston. The Oklahoma City-based natural gas producer reported an estimated $2.5 billion in liabilities as of September 30.

“Despite efforts to streamline our business, our large legacy debt burden in addition to significant legacy firm transportation commitments created a balance sheet and cost structure that was unsustainable in the current market environment,” said David M. Wood, Gulfport’s president and chief executive.

Gulfport wasn’t an outlier—it was a data point in a broader collapse. In 2020, North American E&P bankruptcies involved $56.2 billion of debt, with average debt per company hitting a record $1.2 billion. Haynes and Boone counted 46 E&P Chapter 11 filings that year. More than a fifth of those cases involved over $1 billion of debt, including major restructurings like Chesapeake Energy, Diamond Offshore Drilling, and California Resources.

Gulfport’s plan was straightforward, if painful: use bankruptcy to cut the debt load and reset the business. The company filed alongside its wholly owned subsidiaries to implement a restructuring support agreement with a pre-negotiated plan designed to reduce debt by about $1.25 billion, strengthen the balance sheet, and lower ongoing operating costs.

Under the restructuring agreement, Gulfport planned to issue $550 million of new senior unsecured notes to existing unsecured creditors. It also secured $262.5 million in debtor-in-possession financing from its revolving credit facility lenders, including $105 million in new money subject to court approval. Those same lenders committed to provide $580 million in exit financing when Gulfport emerged from Chapter 11.

It was a sobering moment—not just for Gulfport, but for shale as a whole. In a commodity business, leverage doesn’t just amplify outcomes. It removes your options. When prices fall and the balance sheet is stretched, there’s nowhere to hide.

VII. Emergence & The New Gulfport: Focus & Discipline (2021–2023)

Bankruptcy, it turned out, was less an ending than a hard reset. For Gulfport, Chapter 11 wasn’t about shutting the doors. It was about clearing the wreckage, shrinking the fixed burdens that had made the company uncompetitive, and trying to come back as something sturdier.

As the company put it coming out of restructuring:

"Gulfport is emerging from its successful restructuring having materially improved its balance sheet and midstream cost structure, which leaves Gulfport well-positioned for future success. Today, we begin a new chapter at Gulfport with a strategy focused on continuing to reduce costs and generating sustainable free cash flow in an effort to drive shareholder value."

The numbers behind that “new chapter” mattered because they represented regained breathing room. Gulfport exited bankruptcy with a new Board of Directors, a strengthened balance sheet, and meaningfully less debt—$853 million of total debt after more than $1.2 billion of deleveraging through the Chapter 11 process. It also emerged with around $135 million of liquidity. At emergence, Gulfport’s net-debt-to-EBITDA sat at roughly 1.5x: not perfect, but no longer suffocating.

The timeline was fast, by bankruptcy standards. On November 13, 2020, Gulfport Energy Operating Corporation and its wholly owned subsidiaries filed petitions for voluntary relief under Chapter 11 in the Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of Texas, Houston Division. On April 28, 2021, the court approved and confirmed the Amended Joint Chapter 11 Plan of Reorganization. As part of the emergence process, Gulfport Energy Corporation was incorporated in Delaware on April 30, 2021. Then, on May 17, 2021, the company filed an Amended and Restated Certificate of Incorporation authorizing new shares of common stock.

Those new shares began trading on the NYSE under the ticker “GPOR” on May 18, 2021—symbolically, a return to public markets with a cleaned-up cap table and a mandate to behave differently this time.

That mandate was simple: capital discipline above all else. The company emphasized continued cost reductions and sustainable free cash flow generation in an effort to drive shareholder value. It also committed to an increased focus on sustainability, prioritizing safety, environmental stewardship, and strong community relationships where it operated.

Leadership shifted as the post-bankruptcy era matured. Gulfport named John Reinhart President, Chief Executive Officer and Director effective January 24, 2023. Tim Cutt, who had served as Chief Executive Officer and Chairman since 2021, remained Chairman of the Board.

Reinhart arrived with more than 30 years of industry experience. Most recently, he had been President, CEO, and a board member at Montage Resources Corporation, where he led actions that positioned Montage as a strategic partner with scale, a low debt profile, and top-quartile operational and financial metrics. Earlier stops included roles as CEO of Blue Ridge Mountain Resources and COO at Ascent Resources. He began his oil and gas career at Schlumberger and later held operations roles of increasing responsibility at Chesapeake Energy. Before all of that, he served in the U.S. Army, with tours in Panama and Iraq.

With a healthier balance sheet and a sharper operating philosophy, Gulfport leaned into a returns-first playbook. The priorities were moderate growth, free cash flow generation, and shareholder returns—not production growth for its own sake. The company focused on improving well costs and cycle times and built a more robust hedging program to reduce exposure to commodity price swings.

By 2023, that approach was translating into meaningful adjusted free cash flow generation. And after adjusting for cash flow used for discretionary acreage acquisitions, Gulfport allocated about 99% of its adjusted free cash flow to repurchasing common stock. It did that while maintaining a strong balance sheet, ample liquidity, and financial leverage below one times.

The shift was stark. A company that had just gone through a restructuring that wiped out equity was now built around returning cash to stockholders and defending the balance sheet. Chapter 11 didn’t just change Gulfport’s capital structure. It changed what the company believed it was supposed to optimize for.

VIII. The Consolidation Play: Positioning for the Future (2024–Present)

The Gulfport that stumbled into Chapter 11 in 2020 isn’t the Gulfport operating today. The post-bankruptcy reset didn’t just clean up the balance sheet—it rewired the company’s priorities. Instead of chasing scale at any cost, management has been selling a different identity: disciplined operator, long-life inventory, and, in a consolidating industry, a company that could plausibly do the buying instead of becoming the bought.

Operationally, Gulfport was still very much a two-basin story in 2025. In the second quarter of 2025, net daily production averaged 1,006.3 MMcfe per day, primarily consisting of 800.6 MMcfe per day in the Utica/Marcellus and 205.7 MMcfe per day in the SCOOP. By the third quarter of 2025, net daily production averaged 1,119.7 MMcfe per day, primarily consisting of 916.8 MMcfe per day in the Utica/Marcellus and 202.9 MMcfe per day in the SCOOP.

But the bigger message Gulfport emphasized wasn’t the quarter-to-quarter volumes. It was runway.

In its recent presentation, the company highlighted a major inventory build, with gross undeveloped inventory increasing by more than 40% since year-end 2022. Gulfport estimated approximately 700 gross locations—about 15 years of net inventory—with break-evens below $2.50 per MMBtu.

That matters because in shale, inventory isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the difference between being a long-term business and being a short-term liquidation. Without a deep bench of economic drilling locations, decline curves win. So Gulfport has been spending to extend the clock.

On the Marcellus side, the company expanded undeveloped inventory by approximately 125 gross locations—an increase of roughly 200% in Ohio Marcellus inventory. In the Utica, management also put incremental discretionary capital toward testing the drilling feasibility of U-development. Gulfport recently reached total depth on two U-development wells and said the work unlocked 20 gross Utica dry gas locations.

CEO John Reinhart framed the strategy bluntly, and with a number that signaled intent:

"We are pleased to announce our plans to allocate $75 million to $100 million towards targeted discretionary acreage acquisition opportunities in the coming months and anticipate this investment will expand our high-quality, low-breakeven inventory by more than two years. This represents the highest level of leasehold investment at Gulfport in over six years, reinforcing our ongoing commitment to organic growth."

At the same time, Gulfport kept leaning hard into shareholder returns. The board expanded the company’s common stock repurchase authorization by 63 percent to $650 million. Gulfport planned to allocate approximately $125 million to common stock repurchases in Q4 2025, bringing total 2025 repurchases to approximately $325 million. That pace fit the broader pattern: in recent years, the company said it returned roughly 96–99% of adjusted free cash flow to shareholders.

The financial results supported the narrative. For the first nine months of 2025, revenue reached $1,024.4 million and net income was $295.4 million—up sharply from the prior year. Gulfport also redeemed all Series A Preferred Stock in September 2025 for approximately $31.3 million, further simplifying the capital structure. And after the restructuring reset that wiped away unsustainable debt, Gulfport pointed to a low leverage ratio—approximately 0.81x as of Q3 2025.

Which brings the story to its next strategic fork in the road: does Gulfport stay independent, merge with a peer, or end up as an acquisition target?

With consolidation sweeping across E&P, all three paths were plausible. At one point, the market even kicked around a rumored combination between Gulfport and privately held Ascent Resources—another step in the roll-up of Appalachian gas producers. Analysts summarized the pitch this way: "Our conversations with investors and industry contacts suggest an all-equity reverse merger near proved-developed-producing pricing would be well-received by the market, creating a larger-scale, lower-cost entity that would appeal to investors. We believe scale continues to become more important, especially in areas such as Appalachia."

That deal never happened. But the underlying logic didn’t go away. In commodity businesses, scale buys you staying power—and Gulfport’s footprint and balance sheet leave it in the unusual position of being both a potential consolidator and a plausible target.

IX. The Modern Gulfport: Operations, Culture & Competitive Edge

Today’s Gulfport is built around two concentrated bets: Appalachia for scale and low-cost gas, and Oklahoma’s SCOOP for high-quality, repeatable development. In the SCOOP alone, Gulfport holds roughly 73,000 net reservoir acres in the core of the play. Paired with its Appalachian position, that footprint makes Gulfport a meaningful mid-cap producer with exposure to two of the most productive natural gas basins in the U.S.

In 2024, the Utica/Marcellus did what it has long done for Gulfport: carried the load. Production averaged about 842 MMcfe per day net, roughly 80% of total volumes.

The SCOOP provided the other leg of the stool. Gulfport produced about 212 MMcfe per day net there in 2024, around 20% of total production.

The important part isn’t the split. It’s the operating philosophy behind it. Post-bankruptcy Gulfport sells one core idea: efficiency wins. Company materials consistently highlight gains in drilling speed, completion efficiency, and cost per lateral foot—exactly the kind of incremental, repeatable improvements that matter in a business where the commodity sets the price and you only control the cost.

That discipline shows up in the way Gulfport talks about inventory, too. The company estimates roughly 15 years of net drilling locations with break-evens below $2.50 per MMBtu—its built-in cushion against the whiplash of gas prices. In shale, deep, economic inventory is optionality. It lets you slow down when prices are ugly, then accelerate when the math works again, without needing to scramble for acreage.

Culturally, this version of Gulfport looks like it was forged by its near-death experience. The posture is lean and operator-first, with a heavy emphasis on accountability. The stated strategy is to develop assets in a way that generates sustainable cash flow, improves margins, and keeps operating efficiency moving in the right direction—while maintaining strong environmental and safety performance. Capital allocation follows that same logic: prioritize the highest-return projects, and execute them using leading drilling and completion techniques and technologies.

Gulfport describes its cultural foundation in five pillars: operational excellence through constant measurement and accountability; safety for employees, contractors, and the public; environmental stewardship to minimize footprint; community focus through philanthropic and volunteer outreach; and continuous improvement through ongoing evaluation of operational, environmental, and safety performance.

And like every public E&P that wants institutional capital in the 2020s, Gulfport has had to speak ESG fluently. The company has rolled out enhanced methane monitoring, flaring reduction programs, and water recycling initiatives. Whether that’s enough to win over the most ESG-driven investors is still an open question—but it’s a clear departure from the old shale-era mindset where growth came first and everything else had to keep up.

X. Industry Context & The Future of Oil & Gas

To understand Gulfport, you have to understand the world it sells into. This is a business where the ground might be amazing, the engineers might be elite, and the strategy might be disciplined—and the commodity price can still make you look like a genius or a fool.

That’s why the energy transition debate hangs over every E&P decision. Depending on who you ask, oil and gas are either in the early innings of a long decline, or set up for years of tight supply because the industry has underinvested. Gulfport doesn’t get to pick which narrative wins. It has to survive either one.

The core technological shift that created modern Gulfport was the Shale Revolution: the pairing of hydraulic fracturing with horizontal drilling that turned tight rock into producible reservoirs at scale. That combination reshaped U.S. supply so dramatically that tight oil formations now account for 36% of total U.S. crude oil production.

On the gas side, the U.S. became the world’s largest producer of dry natural gas, supplying about 20% of global output, with roughly 40% coming from shale.

That abundance changed America’s energy posture—but it also created the central headache for gas-heavy producers like Gulfport: oversupply. When the industry can add huge volumes quickly, prices can stay lower for longer. And when prices are weak, the margin for error disappears.

This is also why the SCOOP/STACK matters so much in Gulfport’s story. Appalachia gives scale and low-cost gas, but it also ties you to the gas cycle. Oklahoma offers diversification and liquids exposure that a pure Appalachian profile can’t. In a world where gas can be chronically well-supplied, having another lever matters.

You can see how the industry thinks about the Anadarko opportunity in how peers talk about it. Devon Energy, for example, positioned its STACK holdings as strategically important alongside its Permian and Delaware assets: "We will continue to aggressively ramp up our drilling programs within the U.S., with the majority of this capital directed toward the STACK and Delaware basin."

Then there’s the public-versus-private split—one of the most important structural forces in U.S. shale today. Public E&Ps live under a microscope. Investors want free cash flow, buybacks, dividends, and balance sheet strength, and they punish companies that chase growth. Private operators, often backed by private equity, can play a different game: deploy capital, improve operations, and aim for an exit on a timeline that doesn’t require quarterly applause. The result is a bifurcated market where a company like Gulfport has to prove discipline while competing against players with different constraints.

On the demand side, the long-term case for natural gas leans on big, durable drivers—LNG exports, power generation, and industrial use. Those forces support a bullish view over time. But in the near term, prolific basins can still overwhelm demand and keep prices under pressure.

So Gulfport’s bet isn’t that gas prices will always be friendly. It’s that if you run a tight operation, invest with restraint, and treat the balance sheet like a survival tool, you can still generate attractive returns—even when the commodity doesn’t cooperate.

XI. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Gulfport’s story reads like a case study in how to survive a commodity business: the right pivots, the wrong leverage, and the operational discipline it took to earn a second act. Here are the lessons that stick.

Lesson 1: Strategic pivots are survival mechanisms

Gulfport didn’t win by perfecting its original model. It won by abandoning it. The company moved away from Gulf Coast conventional assets and rebuilt itself around unconventional shale—first in Appalachia (Utica and Marcellus), then with a second engine in Oklahoma’s SCOOP. The common thread wasn’t geography; it was repeatability. In shale, inventory can be manufactured—if you have the rock and the playbook. Companies that cling too long to legacy positions get squeezed. The ones willing to reinvent themselves buy another decade.

Lesson 2: Leverage is a double-edged sword

Gulfport’s Chapter 11 filing is the brutal reminder that debt doesn’t care about your plans. As the company put it, “Despite efforts to streamline our business, our large legacy debt burden in addition to significant legacy firm transportation commitments created a balance sheet and cost structure that was unsustainable in the current market environment.” When commodity prices fall, cash flow can disappear fast. Interest payments don’t.

Lesson 3: Operational excellence is the only sustainable moat

In upstream, you don’t set the price. You live or die by cost, cycle time, and execution. That’s why Gulfport’s post-bankruptcy identity leans so heavily on efficiency and repeatable development. The company highlights a deep inventory base with break-evens below $2.50 per MMBtu—exactly the kind of cushion that matters when the gas tape turns against you.

Lesson 4: Portfolio concentration can win in the right basin

Gulfport’s arc runs from scattered experiments to concentrated, scaled positions. The point isn’t that diversification is bad—it’s that focus compounds when the acreage is strong and the operating machine is tuned. If you’re going to be concentrated, you’d better be concentrated in the right rock.

Lesson 5: Capital cycles and investor sentiment drive valuations

Gulfport lived through the industry’s mood swing: a decade when markets rewarded production growth, followed by a hard pivot to free cash flow and shareholder returns. That shift didn’t just change valuations—it changed what “good management” even meant. In E&P, timing the market’s demands can be as important as drilling the wells.

Lesson 6: Bankruptcy isn’t the end—it’s a reset

For Gulfport, Chapter 11 was a restart button. The company exited with $853 million of total debt after more than $1.2 billion of deleveraging, and net-debt-to-EBITDA of approximately 1.5x at emergence. The equity was gone, but the business came out leaner—and with room to operate.

Lesson 7: The energy sector is undergoing a generational shift

If you invest in energy without a macro framework, you’re gambling. Shale technology, energy transition pressure, and shifting capital availability aren’t side notes—they are the environment. Gulfport’s entire history is what happens when the environment changes faster than companies do.

XII. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces:

Competitive Rivalry: Competition is intense in both the SCOOP/STACK and the Appalachian basins. Devon Energy holds one of the largest STACK positions. Marathon Oil has approximately 300,000 net surface acres across the STACK/SCOOP. Smaller operators like Gulfport and Citizen Energy are active too. Because the product is a commodity, differentiation mostly comes down to who can drill and complete wells more efficiently and more consistently. Consolidation is slowly shrinking the field, but it’s also raising the bar for whoever remains.

Threat of New Entrants: For public companies, the barrier is mostly financial: investors have been wary of funding E&P growth stories, which keeps the door relatively closed. For private equity and family offices, it’s more plausible—especially when distressed assets create entry points. Still, the core barriers are real: capital intensity, technical complexity, and the fact that high-quality acreage is increasingly hard to come by.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Oilfield services are cyclical, and the supplier landscape has been consolidating. Inputs like sand, water, and midstream services can exert real leverage when activity tightens. Gulfport’s scale helps it negotiate, but it can’t opt out of cost inflation when the cycle turns.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Gulfport is a price taker. The key “buyer power” dynamic isn’t a customer squeezing them—it’s infrastructure. Midstream capacity, takeaway constraints, and transportation agreements can materially impact realized pricing. Hedging can smooth some of the volatility, but it can’t change the fundamental reality: the market sets the price.

Threat of Substitutes: Over the long run, the energy transition is the substitute risk: renewables, electrification, efficiency, and policy pressure. Over the medium term, oil and gas still benefit from supply-demand realities, and natural gas continues to lean on the “bridge fuel” narrative. The threat is real—it’s just uneven in timing.

Hamilton's 7 Powers:

Scale Economies: ✅ Yes — In a business with heavy fixed costs, spreading land, infrastructure, and G&A over a larger production base can be a meaningful edge.

Network Effects: ❌ No — There’s no flywheel here. Molecules don’t get more valuable because more people use Gulfport’s molecules.

Counter-Positioning: ❌ No — This isn’t a classic disruptor-versus-incumbent story. The tools and playbooks diffuse across the industry quickly.

Switching Costs: ⚠️ Limited — Midstream commitments and commercial relationships create some stickiness, but they don’t function like true switching costs in software or marketplaces.

Branding: ❌ No — Buyers don’t pay more because “Gulfport” is on the molecule.

Cornered Resource: ⚠️ Moderate — Good rock is finite. Gulfport has highlighted gross undeveloped inventory growth of more than 40% since year-end 2022, reaching an estimated roughly 700 gross locations, or about 15 years of drilling. That inventory depth matters, but it’s still ultimately an acreage game—not a monopoly.

Process Power: ✅ Yes — Execution is the closest thing this industry has to a moat. Well cost leadership, faster cycle times, and better completion design are advantages competitors can copy—but rarely overnight.

Summary: Gulfport’s defensibility is mostly grounded in scale economies, process power, and the quality of its inventory. What it doesn’t have—by nature of the business—is durable protection from commodity prices, or help from branding and network effects. So the company’s “moat” is really a mandate: keep out-executing, quarter after quarter, cycle after cycle.

XIII. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

A clean balance sheet post-bankruptcy gives Gulfport something most shale operators never really have: options. Leverage stayed low—approximately 0.81x as of Q3 2025—leaving the company with flexibility to ride out weak pricing and still play offense when opportunities appear.

The asset base is concentrated in what the company views as tier-1 rock across the SCOOP/STACK and the Utica, which matters because in shale, focus plus quality inventory is the closest thing to durability.

The post-reset model is also doing what it promised: turning operations into cash. In Q3 2025, Gulfport generated $103.4 million in adjusted free cash flow while holding per-unit operating costs at $1.21 per Mcfe.

There’s also a credible consolidation angle. As basins mature, smaller packages and non-core positions come to market—often at prices that can extend inventory without blowing up the balance sheet. A disciplined Gulfport can be a buyer in that environment.

On the macro side, energy security and continued oil and gas demand support the idea that commodity prices can stay high enough—often enough—to make a disciplined, low-cost producer work.

And management has leaned hard into the shareholder-return pitch. The company has talked about returning 96–99% of adjusted free cash flow to shareholders, primarily through buybacks, and it’s positioned around a projected 2025 free cash flow yield of 10.6%.

Bear Case:

The core bear point never changes: Gulfport sells commodities. It has no pricing power, and a macro-driven price move can overwhelm even great execution.

The energy transition adds a longer-dated overhang. If demand destruction accelerates or policy tightens faster than expected, hydrocarbon assets can rerate downward regardless of near-term cash generation.

Inventory is another quiet constraint. The runway looks attractive, but it isn’t infinite—without continued bolt-on acquisitions or successful downspacing and delineation, the drilling clock keeps ticking.

Gulfport also competes in basins dominated by larger, better-capitalized operators like Devon, Continental, and Marathon. Scale can mean lower costs, better service access, and more room to absorb volatility.

Even when operations perform, the public market can still shrug. Equity market apathy toward E&Ps has created valuation compression that’s hard to escape.

And in the day-to-day, execution risk is real. Drilling and completion performance, service-cost inflation, and equipment availability can all squeeze margins quickly.

Finally, there’s headline risk: geopolitics and regulation. Permitting delays, methane rules, and shifting federal policy can change economics or sentiment faster than operators can adjust.

Key Metrics to Watch:

Free Cash Flow Yield: This is the scoreboard. If Gulfport is truly going to return substantially all free cash flow to shareholders, then free cash flow yield becomes the clearest read on what the equity can deliver.

Capital Efficiency ($/lateral foot): A clean way to track whether the operating machine is improving. In a commodity business, steady gains here compound across the entire inventory runway.

Leverage Ratio (Net Debt/EBITDA): Post-bankruptcy, this is existential. The discipline story only holds if leverage stays low; a move back above 1.5x would start to look like the same old shale playbook that ended in Chapter 11.

XIV. Epilogue: Where Does Gulfport Go From Here?

CEO John Reinhart summed up where Gulfport believed it stood heading into 2025: "Gulfport is off to an active start in 2025, delivering first quarter results ahead of Company expectations while remaining on track to execute on our previously provided full year guidance. Our ability to generate adjusted free cash flow during a front-loaded capital program highlights the strength of our asset base and the operations team's high-level of efficiency and execution."

Now comes the part that every mid-cap E&P eventually has to confront. Gulfport’s strategic menu is familiar: stay independent and keep maximizing returns, merge with a peer to gain scale, or become the kind of clean, focused asset base that a larger buyer—or private equity—decides it wants.

By mid-2025, the market was valuing Gulfport as a meaningful, but still bite-sized public operator. The stock traded around $174.36, implying a market cap of roughly $3.1 billion across about 17.6 million shares. Trailing twelve-month revenue sat at about $1.16 billion as of June 2025.

What’s most striking about Gulfport isn’t any single quarter or valuation metric. It’s how complete the transformation has been. A company that nearly stopped existing came back with a different operating philosophy, a different balance sheet, and a different relationship with investors. Same name. Different DNA.

And the broader lessons travel well beyond Gulfport. For investors, it’s a reminder that energy doesn’t behave like growth sectors. The commodity is the sun everything orbits. Strategy matters, but it’s mostly about adapting to forces management can’t control—and winning often looks like being slightly less wrong than everyone else.

For business strategists, Gulfport is proof that crisis can create room for reinvention. Bankruptcy stripped away the baggage of the prior era—too much debt, too many fixed obligations, too little flexibility—and forced a reset. Not every company survives long enough to get that second chance. Gulfport did.

In the end, Gulfport’s story tracks the arc of American shale itself: the early optimism, the debt-fueled sprint, the industry-wide reckoning, and then the discipline of a sector that finally learned what it costs to be wrong. If you want a single company that captures that whole journey, Gulfport is a good place to start.

XV. Further Reading & Resources

-

"The Boom: How Fracking Ignited the American Energy Revolution" by Russell Gold — The clearest narrative on the shale breakthroughs that made Gulfport’s reinvention possible

-

Gulfport Energy SEC filings (10-Ks, 8-Ks) — The primary record: strategy shifts, asset moves, and the financial details behind the headlines

-

"The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power" by Daniel Yergin — The long view on how oil shaped markets, geopolitics, and the rules of the game

-

Energy podcasts: Odd Lots (Bloomberg), The Crude Life — Ongoing commentary on energy, markets, and the forces moving commodities

-

EIA (Energy Information Administration) data and reports — The macro backdrop: supply, demand, production trends, and pricing context

-

Bankruptcy court filings (2020–2021) — The unfiltered mechanics of Gulfport’s restructuring and what actually changed in Chapter 11

-

Oklahoma Geological Survey and Ohio DNR reports — Ground-truth geology and basin-level production data for the SCOOP/STACK and Utica/Marcellus

-

"Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power" by Steve Coll — A deep look at how the biggest players operate, think, and influence the industry

-

Industry research from Raymond James, Tudor Pickering, Jefferies — Useful framing on E&P strategy, valuations, and how analysts interpret the cycle

-

Baker Hughes rig count and service cost indices — A pulse check on activity levels and oilfield inflation, week to week and cycle to cycle

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music