Alphabet Inc.: The Architecture of Internet Dominance

Introduction

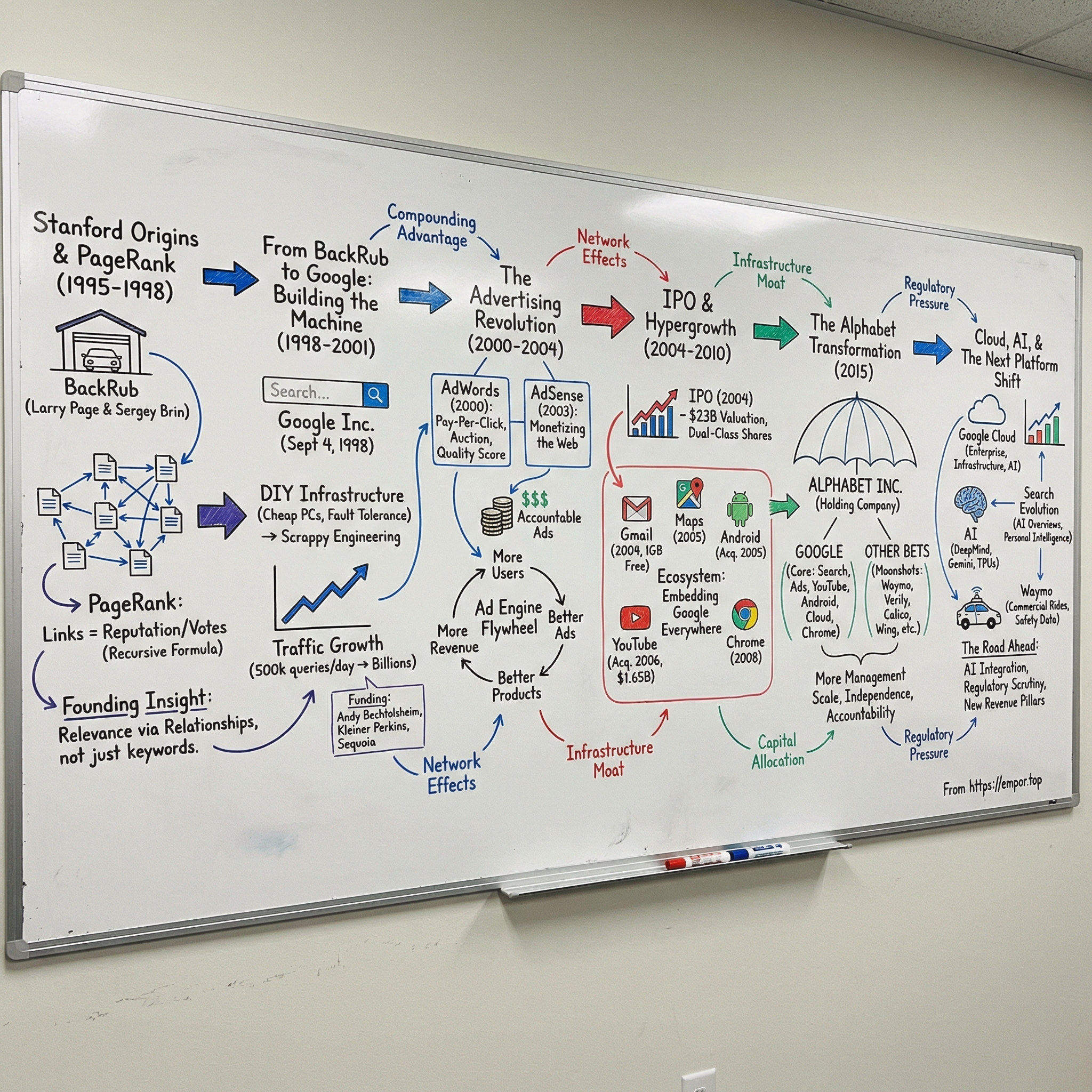

How did two PhD students—working out of a garage in Menlo Park—end up building the gateway most of humanity now uses to access information? The answer is a mix of a deceptively simple mathematical insight about how the web is structured, an advertising engine that became one of the greatest cash machines in business history, and a culture willing to pour billions into ideas that might take decades to pay off. Today, Alphabet—the parent company of Google—is valued at more than two trillion dollars, with products that billions of people rely on every day.

This is the story of how a Stanford research project called BackRub turned into “to google.” How a plain, fast search box became the most valuable piece of real estate in advertising. And how a company that started by ranking web pages now builds self-driving cars, designs custom chips, and is racing to define the future of artificial intelligence. It’s also the story of what happens when success compounds so dramatically that governments around the world start asking whether any one company should have this much power.

Alphabet’s arc follows a familiar tech pattern: a technical breakthrough creates a product people can’t live without. That product throws off enormous profits. Those profits fund expansion into adjacent markets—some of which become platforms in their own right—unlocking even more scale, leverage, and ambition. To understand Alphabet today, you have to understand how each link in that chain was forged—and where it might finally be vulnerable.

Stanford Origins and The PageRank Revolution (1995-1998)

In the mid-1990s, the web was exploding—and finding anything on it was getting harder, not easier. The leading search engines of the day—AltaVista, Lycos, Excite—mostly played a simple game: match the words you typed to the words on a page. Type “jaguar,” and you could get the car, the animal, or someone’s personal homepage that mentioned the word once. Worse, the system was easy to rig. Just cram enough keywords into your site and you could float to the top. The web was drowning in its own abundance.

Larry Page arrived at Stanford in the fall of 1995 as a 22-year-old computer science PhD student with a very different obsession. He wasn’t trying to build a better keyword matcher. He was fascinated by the shape of the internet itself—the mathematical structure of the web as a system. Encouraged by his advisor, Terry Winograd, Page began looking at the web’s link structure as one enormous graph: every page a node, every hyperlink an edge. To study it, he built a project called BackRub that crawled the web and, crucially, paid special attention to backlinks—links pointing to a page.

Sergey Brin, another Stanford PhD student, soon joined in. Brin had been born in Moscow and immigrated to the United States at age six. At Stanford, he had a reputation for being intellectually fearless and direct. Where Page tended to be quiet and methodical, Brin was restless and expansive. As partners, they fit.

The key insight arrived when they realized backlinks weren’t just an interesting artifact to measure. They were a signal. If lots of pages link to a page, that page is probably valuable. And if the pages doing the linking are themselves widely linked-to, that endorsement should count even more. It’s the difference between a recommendation from a stranger and one from a Nobel laureate. Page and Brin turned that intuition into PageRank: a recursive formula that gave every page a score based on both the volume and the credibility of the links pointing to it.

The academic analogy wasn’t accidental—it was the whole point. In research, a paper’s importance is often judged by citations, and a citation from an influential paper is worth more than a citation from an obscure one. PageRank treated hyperlinks like citations and computed a web-wide reputation score. The math was elegant. The results were startlingly better.

At first, Page and Brin didn’t set out to start a company. They tried to license the technology to existing search engines—approaching firms like Excite, which famously passed. But the product kept pulling them forward. Running on Stanford servers and improvised hardware, their search engine spread by word of mouth. By mid-1998, it was already handling around ten thousand searches a day. Page later put it plainly: “Pretty soon, we had 10,000 searches a day. And we figured, maybe this is real.”

Money arrived in the most Silicon Valley way possible. After a quick demo, Andy Bechtolsheim, co-founder of Sun Microsystems, wrote them a $100,000 check made out to “Google Inc.”—a company that didn’t legally exist yet. Jeff Bezos, then building Amazon, invested too. Along with family, friends, and other angels, they raised roughly $1 million—enough to leave the dorms behind and set up in their first “office”: a garage in Menlo Park owned by Susan Wojcicki, who would later become CEO of YouTube.

What made PageRank different was its worldview. Other search engines tried to understand what a page said. Page and Brin focused on what the rest of the web believed. Relevance came from relationships, not just keywords. That single shift—from text to reputation—turned out to be one of the most valuable ideas in the history of the internet.

From BackRub to Google: Building the Machine (1998-2001)

Google officially incorporated on September 4, 1998. The name nodded to “googol,” the number one followed by a hundred zeros—an inside-baseball math joke that doubled as a mission statement: organize an almost unimaginably large amount of information. The origin story is fittingly nerdy: someone went to register a domain, typed “google” instead of “googol,” and the typo turned into one of the most valuable brands on earth.

Early Google was a study in contrasts. On the surface, it was almost suspiciously plain: a stark white page, a single search box, and not much else. This was the era when portals like Yahoo tried to be your entire internet—news, sports, weather, stock quotes, everything fighting for space. Google bet on the opposite. Get the answer fast. Get out of the way.

But behind that clean interface was a brutal engineering problem: crawling, sorting, and serving the entire web took immense computing power, and Page and Brin couldn’t afford fancy enterprise servers. So they did what scrappy engineers do—they built their own. Google stitched together clusters of cheap, commodity PCs and wrote software that assumed machines would fail constantly. Instead of treating failures as emergencies, the system treated them as normal. That do-it-yourself approach to infrastructure didn’t just keep costs down. It became part of Google’s identity, and eventually, a real moat.

The traction was undeniable. By early 1999, Google was handling roughly half a million queries a day—and climbing. The garage days were over; the company needed real capital. In June 1999, it landed a $25 million round from two Silicon Valley heavyweights: Kleiner Perkins and Sequoia Capital. The pairing was notable because the firms rarely co-invested, and both initially hesitated to share the deal. In the end, they did it anyway—John Doerr took a board seat for Kleiner Perkins, Michael Moritz for Sequoia—and the round valued Google at about $100 million. In hindsight, it was one of the great venture bets of all time.

Larry Page was still CEO, but investors had a familiar concern: the product was world-class, but the company was growing up fast, and someone needed to run the machine. In 2001, Eric Schmidt came in as CEO. He had a PhD in computer science from Berkeley, had been CTO at Sun Microsystems, and had run Novell. He was in his mid-50s, with a calm, corporate presence—an intentional contrast to the twentysomething founders zipping around the office on scooters. Schmidt later described his job with a phrase that stuck: “adult supervision.” And to his credit, he understood what he was supervising. Page and Brin weren’t just talented engineers—they were building a new default interface to the internet.

The resulting structure was unusual but worked: Schmidt as CEO, Page as president of products, Brin as president of technology. Schmidt brought operational discipline and credibility with partners. Page and Brin kept driving the product and the technical roadmap. Around this time, Google embraced the informal motto “Don’t be evil”—a line that would later attract both praise and criticism, but early on captured a real internal belief: that you could build a massive business without betraying the user.

Then the dot-com bubble burst. From 2000 into 2001, Silicon Valley got wiped out—companies collapsed, budgets froze, and talent flooded back onto the market. Google, still private and relatively lean, didn’t just survive the crash. It benefited from it. Competitors weakened or vanished, hiring got easier, and advertisers—burned by flashy, unmeasurable banner campaigns—started looking for something more accountable.

Google was about to give them exactly that.

The Advertising Revolution: AdWords and AdSense (2000-2004)

The story of Google’s advertising business starts with a contradiction: the founders didn’t want one. In their 1998 paper on search, Page and Brin basically argued that ad-funded search engines would end up serving advertisers before users. They had watched the web fill up with flashing banner ads and popup chaos, and they wanted Google to feel like the antidote.

But philosophy doesn’t pay for servers. By 2000, Google had the users—and the bills—but not a business model.

So in October 2000, Google launched AdWords: a self-serve way for advertisers to place small text ads next to search results. It was deliberately understated, closer to a helpful suggestion than an interruption. The first version looked like traditional advertising in one key way: advertisers paid by impressions, not outcomes.

That changed in 2002, when Google rebuilt AdWords around two ideas that would define modern internet advertising: pay-per-click and auctions. Now, when someone searched, Google would run a real-time competition among advertisers bidding on related keywords. The winners appeared next to the results, and advertisers only paid when someone actually clicked.

But the real masterstroke wasn’t the auction—it was that Google refused to let the highest bidder automatically win. Instead, it introduced Quality Score, a measure that rewarded relevance. An advertiser with a lower bid but a more useful, more clicked-on ad could outrank a competitor throwing money at a mediocre message.

That single design choice aligned everyone’s incentives. Users got ads that were more likely to be genuinely helpful. Advertisers were pushed to write better, clearer copy and build better landing pages, and they could often pay less if they did it well. And Google made more, not less, because a system that maximizes usefulness tends to maximize clicks—and clicks were now the cash register. It was a flywheel competitors could imitate in form, but struggled to match in outcomes.

Then came the second breakthrough: AdSense in 2003. AdWords monetized Google’s own search pages. AdSense turned the rest of the internet into inventory. Suddenly, a cooking blog, a local newspaper site, or a niche forum could plug into Google’s ad system and start earning money without hiring a sales team. Google handled the targeting, the payments, and the optimization. Publishers got a share of the revenue—Google kept roughly a third—and the long tail of the web got a business model.

Put AdWords and AdSense together and you get a two-sided marketplace with rare leverage. Advertisers could reach people at the exact moment they signaled intent—when they were actively searching. Publishers could monetize traffic of almost any size. And Google sat in the middle, taking a cut while using data and algorithms to keep improving the matching.

By 2004, the machine was throwing off billions in revenue, powered by something the old media world couldn’t offer: accountability. With pay-per-click, you weren’t buying a vague promise of “exposure.” You were buying measurable action. A local business could spend a small amount, see exactly what happened, and decide whether to spend more. That measurability became the wedge that pulled budgets away from print, radio, and TV—and into Google.

By 2020, search advertising alone was generating well over a hundred billion dollars a year and made up the majority of Google’s ad revenue. The ads Page and Brin once warned could corrupt search ended up funding the most formidable product and infrastructure expansion the internet has ever seen.

IPO and Hypergrowth Era (2004-2010)

On August 19, 2004, Google went public—and did it in a way that felt very on-brand. Instead of the usual Wall Street choreography, Page and Brin pushed for a Dutch auction. Regular investors could bid directly for shares, rather than having banks quietly dole them out to favored clients. It was egalitarian in theory, disruptive in practice, and it irritated plenty of people who were used to the old rules.

The IPO raised $1.66 billion at $85 a share, valuing Google at roughly $23 billion. Overnight, Page and Brin became billionaires. But the more important moment wasn’t the money. It was the declaration of independence.

In their IPO letter, they told shareholders exactly what kind of company they intended to be: “Google is not a conventional company. We do not intend to become one.” Then they made that real with a dual-class share structure that kept voting control in founders’ hands even as the company sold stock to the public. It was controversial, but it insulated Google from quarterly pressure and gave the team room to make long-term bets—an approach other tech companies would later copy.

The years after the IPO were a blur of scale. Search volume surged from roughly 500,000 queries a day at the end of 1999 to about three billion per day by 2011. The ad machine scaled with it, turning that attention into revenue and profit at a pace that was hard to comprehend in real time.

But the truly defining move of this era was that Google refused to stay “just search.” In April 2004—months before the IPO—it launched Gmail and handed users one gigabyte of storage for free, roughly a hundred times what competitors offered. The offer sounded so absurdly generous that many people assumed it was an April Fools’ prank. It wasn’t. Gmail was a product, yes—but it was also a flex. Google could do that because it had built an infrastructure machine that made storage and compute cheaper than anyone else could manage.

Then came Google Maps in 2005. And around that same time, Google bought a small company called Android Inc., which was working on a mobile operating system. The acquisition, reportedly for about $50 million, barely registered in the press. In hindsight, it was a defensive masterpiece: a way to make sure Google had a seat at the table as computing shifted from desktops to phones. Android would go on to power more than 70% of the world’s smartphones.

In October 2006, Google made the purchase that looked the craziest at the time: YouTube, for $1.65 billion in stock. YouTube was young, losing money, and wrapped in copyright risk. Critics called the price reckless. Page and Brin saw something else: video was going to be the internet’s next great format, and YouTube already had the gravity—users, creators, culture, and momentum—that would be nearly impossible to recreate from scratch. It became one of the most famous “overpays” that turned into a bargain.

In 2008, Google launched Chrome, stepping into a browser market that seemed basically settled between Internet Explorer and Firefox. Chrome won by being fast, clean, and tightly connected to Google services. Before long it became the dominant browser, giving Google yet another critical distribution channel to keep search—and everything around it—within easy reach.

Gmail, Maps, Android, YouTube, Chrome: these weren’t side quests. They were pieces of a strategy. Google kept pushing into the places where people spend time, seek answers, and make decisions. Each product expanded the surface area for ads, improved the data feeding the ad system, and strengthened Google’s default position in everyday life. Android helped put Google on the phone. Chrome helped put Google on the desktop. Gmail kept users logged in. YouTube created a new kind of advertising medium. Maps connected digital intent to physical-world commerce.

The result wasn’t a portfolio. It was an ecosystem—interlocking products that reinforced one another. And once that ecosystem clicked into place, Google’s advantage stopped looking like a feature lead and started looking like a structural one: the whole became far greater than the sum of its parts.

For investors, this was the era when the real lesson became clear. Google didn’t win by being a little better at search. It won by embedding itself everywhere people interact with information—until, in practice, using the internet started to look a lot like using Google.

The Alphabet Transformation (2015)

On August 10, 2015, Larry Page published a blog post that landed like a thunderclap. Google—the company whose name had become a verb—was getting a new boss. A holding company called Alphabet Inc. would sit at the top. Google would become its biggest subsidiary. And the sprawling collection of experiments Google had built over the years—self-driving cars, life sciences, high-altitude internet balloons, and more—would be split out into their own businesses under the Alphabet umbrella.

The logic was both philosophical and intensely practical. Page had long been drawn to “moonshots”: ambitious bets that might take a decade to prove out, if they ever did. But inside the old Google, those projects lived in the shadow of an advertising empire. A glucose-sensing contact lens being developed by the life sciences team and a longevity lab called Calico had almost nothing in common with the engineers fine-tuning AdWords click-through rates. Yet they all rolled up into the same org chart, the same financial statements, and the same stock narrative.

Page wanted what he called “more management scale” for ventures that were, in his words, “far afield.” Alphabet would make Google “cleaner and more accountable,” while giving each moonshot enough independence to run on its own clock, with its own leadership and its own operating discipline. Eric Schmidt later pointed to an influence: Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. Schmidt had encouraged Page and Brin to meet with Buffett, and they liked the idea of a structure that could fund and oversee very different businesses without forcing them into a single corporate mold.

Under Alphabet, Google still produced roughly ninety percent of the revenue—search, ads, YouTube, Android, Chrome, Maps, and the cloud business. Everything else went into a bucket called Other Bets: Waymo (self-driving cars), Verily (life sciences), Calico (longevity research), Wing (drone delivery), Loon (internet balloons, later shut down), and a rotating cast of additional ventures.

The reshuffle also made official a leadership transition that had been quietly underway. Sundar Pichai, who had climbed through the company by leading Chrome and then Android, became CEO of Google. Page moved up to CEO of Alphabet, with Brin as president. In reality, Page and Brin were already pulling back from day-to-day management. In December 2019, they made it formal: they resigned their executive roles, and Pichai became CEO of both Google and Alphabet. The founders kept their controlling voting stakes and board seats—but the operating company was now firmly in someone else’s hands.

Pichai’s rise was remarkable on its own terms. Born in Chennai, India, he grew up in a modest two-room apartment, sleeping on the living room floor with his brother. He studied metallurgical engineering at IIT Kharagpur, then went on to graduate degrees at Stanford and Wharton. Inside Google, he was known as calm, analytical, and consensus-driven—almost the inverse of Page’s sometimes abrupt, relentlessly visionary style. Whether that steadier profile is ideal for a company facing existential competition in AI is one of the defining questions Alphabet investors are still debating.

Alphabet also delivered something investors had been asking for: visibility into how much the moonshots were costing. The numbers made it obvious the tab was large—Other Bets lost billions of dollars a year, with Waymo consuming especially heavy capital. But the new reporting also highlighted the deeper point: Google’s core business was so profitable—with operating margins routinely above thirty percent—that it could fund a portfolio of long-shot experiments and still throw off enormous cash. Alphabet wasn’t a retreat from ambition. It was a way to keep swinging—without letting the swings blur the scoreboard.

Search Dominance and The Advertising Empire Today

To understand Alphabet’s economics, start with the simplest truth: advertising still pays for almost everything. More than three-quarters of Alphabet’s revenue comes from ads. In 2023, the company brought in about $307 billion in total revenue, and roughly $265 billion of that was advertising. By Q3 2025, Alphabet crossed $100 billion in quarterly revenue for the first time, reporting $102.3 billion for the quarter, up 16% year over year. It’s not hypergrowth—but at this size, growth like that is a statement.

That ad empire has two main engines. The first, and far larger, is ads on Google’s own properties: Search, YouTube, Gmail, Maps, and the Play Store. When someone searches “best running shoes” and clicks a sponsored result, that’s the core business at work. The second is the Google Network: ads placed across third-party websites and apps through AdSense and the broader Google Ad Manager stack. Over time, that network side has shrunk in relative importance as more ad dollars have concentrated on Google’s owned-and-operated surfaces—especially YouTube.

And YouTube isn’t a “surface” so much as a parallel media universe. The $1.65 billion acquisition that looked reckless in 2006 produced $31.5 billion in advertising revenue in 2023—about a tenth of Google’s total revenue. YouTube has grown from a scrappy user-generated video site into a full-spectrum media company: YouTube TV takes on cable bundles, Shorts fights TikTok, Premium and Music go after Spotify, and the ad-supported core increasingly competes with traditional television for both attention and budgets. In Q3 2025, YouTube ad revenue hit $10.26 billion, up 15% year over year.

Google’s dominance isn’t just brand recognition—it’s compounding advantage. More users generate more intent data. More intent data improves targeting and measurement. Better targeting boosts advertiser ROI. Better ROI attracts more advertisers. More advertisers drive auction competition, which raises prices and revenue per search. That money funds better products and infrastructure, which brings in more users—and the loop tightens again. After two decades of spinning, the flywheel has pushed Google to roughly 28–29% of global digital ad spend.

The mobile era was supposed to be the moment this machine got disrupted. Instead, it mostly made it stronger. The 2009 acquisition of AdMob gave Google a leading mobile ad platform, and Android helped keep Google Search in the default seat on most of the world’s smartphones. The big exception has always been iOS—where Google has leaned on massive payments, reportedly over $20 billion per year, to remain the default search engine in Safari. Those default deals later became a central target for regulators.

Which brings us to the biggest cloud hanging over the ad business: antitrust. In August 2024, U.S. District Judge Amit Mehta ruled that Google had illegally maintained a monopoly in search through its default agreements. The remedies phase concluded in September 2025. Mehta declined to order a breakup of Chrome, which the Department of Justice had sought, but he did impose real constraints: Google was barred from exclusive default agreements for Search, Chrome, Google Assistant, and the Gemini app; default placement contracts were limited to one-year terms; and Google was ordered to share certain search index and user interaction data with competitors, with a six-year monitoring committee overseeing compliance. Alphabet’s stock jumped more than 8% on the news that Chrome would not be divested—an unmistakable sign of market relief.

A separate antitrust fight hits even closer to the plumbing of the ad machine. In April 2025, a case focused on Google’s ad-tech business—alleging monopolistic control over advertising exchange infrastructure—was decided against Google. The remedies phase is expected to begin in September 2026, and it could include a forced divestiture of AdX, Google’s ad exchange. If the search case targets distribution, this one targets the tollbooth—because AdX sits at the center of how programmatic ad transactions get executed.

Cloud, AI, and The Next Platform Shift

For most of its life, Alphabet has been a one-trick pony—an extraordinary one. Advertising has typically delivered the vast majority of revenue, while everything else either supported that engine or lived in the “maybe someday” bucket. The first real crack in that narrative has come from a place that once looked like an afterthought: Google Cloud.

Cloud was a late arrival. Amazon Web Services had already defined the category, and Microsoft Azure had years of momentum before Google took enterprise seriously. For a long time, the division bled money and struggled to win big corporate deals. Part of that was perception: Google was seen as brilliant at engineering, but awkward at the relationship-heavy, sales-driven work of landing and keeping enterprise customers.

The inflection point came in 2019, when Alphabet hired Thomas Kurian, a veteran Oracle executive, to run the business. Kurian brought what Google had historically lacked: enterprise go-to-market discipline. He built out the sales organization, tightened execution, and pushed the product toward industry-specific solutions that enterprises could actually buy and deploy.

By 2025, the turnaround was unmistakable. In Q3 2025, Google Cloud generated $15.2 billion in revenue, up 34% year over year. More importantly, it was no longer “growing but losing.” Operating income reached $3.6 billion, with a 23.7% operating margin, up from 17.1% the year before. Backlog hit $155 billion, pointing to a long runway of contracted demand. Google Cloud still sat behind AWS and Azure in market share, but it had become a real contender—especially for customers who wanted infrastructure built for the AI era.

And that’s where Alphabet’s next chapter gets interesting, because AI is the rare platform shift that threatens Google’s core while also playing to its deepest strengths.

For more than a decade, Google has been one of the world’s most important AI research engines. In 2017, it published “Attention Is All You Need,” the paper that introduced the Transformer architecture—the foundation beneath modern large language models, from OpenAI’s GPT series to Meta’s Llama to Google’s own Gemini. Meanwhile, Google Brain and DeepMind—acquired in 2014 for roughly $500 million—kept stacking breakthroughs, from AlphaFold’s protein-structure prediction to game-playing systems that surpassed human performance.

Yet the moment that shook investors came from outside the building. When OpenAI launched ChatGPT in November 2022, it wasn’t just a viral product. It rewrote the narrative overnight: search suddenly looked disruptable, and Microsoft—through its partnership with OpenAI—looked like it had seized the initiative.

What followed has been less collapse and more scramble. Google shipped its Gemini family of models and iterated fast. By late 2025, Gemini 3 Pro launched with major gains in reasoning, multimodality, and efficiency. The Gemini app crossed 650 million monthly active users. And in January 2026, Google introduced Personal Intelligence, connecting Gemini to a user’s Gmail, Photos, and other Google services to deliver deeply personalized assistance—an approach that leans hard on Google’s unique position as the keeper of billions of people’s digital lives.

Alphabet’s AI strategy isn’t just software. It’s also hardware—because in this era, compute is destiny. Google has poured investment into its Tensor Processing Units, or TPUs, as an alternative to Nvidia GPUs for training and inference. The latest generation, Ironwood TPUs, power Google’s internal workloads and are sold to Cloud customers. In a notable deal, Alphabet signed an agreement giving Anthropic access to up to one million TPUs in a multi-billion-dollar arrangement—an indicator that external demand for Google’s AI infrastructure is real. If that trend holds, TPUs could become something Alphabet has rarely had outside ads: a major new revenue stream. Not just “Google runs on chips,” but “Google sells chips.”

At the center of this effort is Google DeepMind. In 2023, Alphabet merged DeepMind and Google Brain into a single organization—Google DeepMind—trying to shorten the distance from breakthrough research to shipped products. And the lab’s credibility only grew when Demis Hassabis, its leader, won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2024 for AlphaFold’s contribution to protein-structure prediction. That’s not a consumer feature. It’s a reminder: Google isn’t merely competing in AI; it helped build the field.

Outside the core, Waymo remains the most advanced of Alphabet’s moonshots—and the one that increasingly looks like a business rather than a science project. As of December 2025, Waymo was completing 450,000 paid rides per week, with plans to hit one million weekly rides by the end of 2026. It announced expansions to Miami, Dallas, Houston, San Antonio, Orlando, and London, with testing underway in New York City, Detroit, and Washington, D.C. With over 100 million fully autonomous miles driven, and safety data showing more than a ten-fold reduction in serious injury crashes versus human drivers, Waymo has quietly become the global leader in commercial autonomous driving. Bloomberg reported an annualized revenue run rate of $350 million and a fundraising target valuation in the $100 to $110 billion range.

Not every bet has landed as cleanly. Hardware has been a mixed story. Pixel phones earn strong reviews but hold only a small share of the global smartphone market. Nest faces relentless competition from Amazon’s Alexa ecosystem. For Google, hardware has mostly functioned as a showcase—a way to ship the “ideal” version of its software and AI—more than a standalone profit engine.

If you want the simplest signal of what Alphabet believes comes next, don’t look at mission statements. Look at capital spending. The company guided to $91 to $93 billion in capex for 2025, overwhelmingly aimed at data centers and AI infrastructure. Even with that intensity, Alphabet still produced $24.5 billion of free cash flow in Q3 2025, and $73.6 billion over the trailing twelve months—enough to keep investing while continuing buybacks. It ended Q3 2025 with $98.5 billion in cash and marketable securities.

The story here is straightforward: Alphabet is using the cash gush from ads to buy its way into the next platform—before that platform eats the business that funds everything.

Playbook: Business and Investing Lessons

Alphabet’s story is easy to get lost in—the wild products, the dizzying scale, the moonshots. But step back and it leaves a surprisingly clean set of lessons that apply far beyond Silicon Valley.

First: real technical superiority can be the strongest moat there is. PageRank wasn’t clever positioning or a temporary head start. It was a fundamentally better way to solve a problem that mattered to everyone using the web. And because it was better, it pulled users in. Those users pulled advertisers in. The revenue from advertisers paid for more engineers and more computing power, which improved the product again. The flywheel started with substance. Distribution and brand came later.

Second: the best marketplaces don’t just match buyers and sellers—they lock in sequencing. Google’s ad business is a two-sided marketplace connecting advertisers with inventory across Google’s own surfaces and the wider web. But two-sided marketplaces are brutal to bootstrap because each side waits for the other. Google cracked the chicken-and-egg problem by earning demand first. Search delivered users organically, without paying to acquire them. Only then did Google layer in advertisers with AdWords—and only after that did it expand supply across the internet with AdSense. Same marketplace, entirely different outcome because the order of operations was right.

Third: owning infrastructure is a strategy, not a line item. Google didn’t just build software; it built the machine beneath the software—data centers, custom servers, and eventually custom chips. That ownership creates advantages that compound: lower unit costs, tighter performance, and the ability to push innovation down into the stack when the next platform shift shows up. It also creates stickiness. Once companies build on Google-specific tools and systems in Cloud, switching becomes harder—sometimes technically, sometimes economically, often both.

Fourth: Alphabet is a capital allocation experiment hiding inside a tech company. The holding-company structure separates the cash-printing core from the speculative frontier. It forces accountability—Google makes the money, Other Bets spend it—and it makes the trade-offs visible. Whether that portfolio ultimately earns returns that justify years of losses is still unresolved. But the structure makes the question unavoidable, which is more than you can say for most conglomerates.

Fifth: scale attracts regulation, and regulation reshapes strategy. Alphabet’s dominance in search and advertising didn’t just create profits—it created scrutiny. That puts the company in a constant balancing act: defend the practices that built the empire while investing aggressively in technologies, like AI, that could disrupt the very business it’s defending. Pull that off and you stay on top. Miss the timing and you either get regulated into a corner or disrupted before the next engine is ready.

Finally: moonshots are easy to celebrate and hard to run. The incentives inside any giant organization tilt toward the profitable present. Teams gravitate toward clear metrics, near-term impact, and projects that reliably move revenue. That’s exactly why Alphabet tried to protect long-horizon bets by giving them separate leadership and reporting lines. The results have been mixed. Some efforts have been shut down, like Loon and Makani. Others, like Waymo, have consumed enormous capital and time, and still haven’t produced meaningful profit. The lesson isn’t that moonshots don’t work—it’s that even for Alphabet, they’re never simple, and they’re never guaranteed.

Analysis: Bear vs. Bull Case

Alphabet sits at roughly a two-trillion-dollar market cap, or about 29.6 times blended earnings. Whether that’s cheap, fair, or expensive depends on one question: will the company’s next decade look like “search keeps printing money while Cloud and AI add a second engine,” or “AI and regulators slowly pry open the moat”?

The answer lives in the bull and bear cases.

The Bull Case

The bull case starts with the obvious: Google’s advertising business remains one of the most durable profit machines on the planet. In Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers terms, Google has multiple advantages stacked on top of each other: scale economies (massive, efficient infrastructure), network effects (more users draw more advertisers, which improves the auction), switching costs (advertisers have campaigns, data, and workflows built around Google’s tools), and brand (when your name becomes a verb, you don’t have a normal marketing problem). Through a Porter’s Five Forces lens, the threat of new entrants in search is extremely low—any credible challenger needs huge capital, elite talent, and mountains of data. Supplier power is real but concentrated, with Apple extracting large payments for default placement. Buyer power is diffuse across millions of advertisers, which limits any one customer’s leverage.

The second pillar is that Google Cloud is no longer just “promising.” It’s inflecting. With roughly 34% growth, expanding margins, and a $155 billion backlog, Cloud is shifting from an expensive strategic necessity into a meaningful profit contributor. And as AI workloads drive a step-change in compute demand, Google’s vertically integrated stack—TPUs, Gemini models, and cloud infrastructure—can create real stickiness for enterprise customers who build deeply on it.

Third, Alphabet’s long-running habit of placing weird bets still offers asymmetric upside. Waymo alone could plausibly be worth tens of billions as autonomous ride-hailing scales. TPUs could grow into a multi-billion-dollar hardware revenue stream. And Google’s research depth—from large language models to robotics to drug discovery—creates optionality that’s hard to model, but hard to ignore.

One more datapoint bulls point to: Berkshire Hathaway initiating a stake of roughly 17.8 million shares, worth an estimated $4.3 billion in Q3 2025. Buffett has historically avoided most technology names, so even a small “toe in the water” reads as an endorsement that this isn’t just a growth story—it’s a durable cash generator at a price he can live with.

The Bear Case

The bear case is that the risks here aren’t theoretical anymore—they’re on the record.

Start with regulation. Google has already lost two major antitrust cases in the United States, with remedies that restrict default agreements and could ultimately force a divestiture of its ad exchange. In Europe, regulators have already extracted billions in fines. The danger isn’t just paying penalties; it’s that sustained global regulatory pressure chips away at the distribution and ad-tech advantages that make the machine so hard to compete with.

Then there’s the existential one: AI could change how people find information. If conversational assistants become the default interface, the traditional search results page—where ads live and where Google has mastered intent monetization—could matter less. Google is investing aggressively to lead in this transition, but it’s also trapped in the innovator’s dilemma: the business most threatened by AI is the one that funds everything, and leaning into AI-native experiences could cannibalize search economics before a replacement model is fully proven.

Competition is also coming from every direction at once. TikTok has pulled attention—and ad budgets—especially from younger users. Amazon has captured more commerce-intent searches, the most valuable slice of advertising. Apple’s privacy changes have made targeting harder across the mobile ecosystem. And in AI, Microsoft’s partnership with OpenAI, Meta’s Llama models, and a wave of well-funded startups are all fighting for platform position.

Finally, valuation matters. At around thirty times earnings, Alphabet’s stock already assumes a lot goes right. If ad growth slows meaningfully, if Cloud margins don’t scale as hoped, or if AI spend fails to translate into defensible product advantage, the cushion at today’s price is thin.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch

Two metrics do the clearest job of telling you which story is winning.

The first is Google Services revenue growth, the cleanest proxy for the health of the core advertising flywheel across Search and YouTube. Sustained low-double-digit growth suggests the engine is still compounding; a slide toward consistent single-digit growth would signal maturity, displacement, or both.

The second is Google Cloud revenue growth and operating margin trajectory. If Cloud keeps growing fast while margins expand, Alphabet is building a second profit pillar. If growth slows before profitability meaningfully scales, then Alphabet remains, at its core, an advertising company spending huge sums to defend itself in the next platform shift.

Epilogue: The Road Ahead

When ChatGPT arrived in late 2022, it sparked what people inside and outside Google described as a “code red.” For the first time in two decades, Google’s core experience—type a query, get a list of links—had a mainstream alternative that didn’t just compete on quality. It competed on format. Instead of sending you out to hunt for answers, it could give you one, directly, in plain language.

Google’s response has been fast, and massive. Gemini, AI Overviews in Search, Personal Intelligence, and an aggressive push to weave AI into nearly every product line are all variations of the same bet: that Google can lead the transition to AI-native computing, rather than watch it erode the foundation of the business. The Gemini app reaching 650 million monthly active users suggests the effort is landing. But the central question hasn’t changed. Does AI expand how much “information seeking” people do, creating more opportunities for Google to serve value and monetize it? Or does it collapse the traditional search journey—fewer clicks, fewer commercial touchpoints, fewer chances to run the auction that funds everything else?

If you were running Alphabet, the next decade would likely come down to three imperatives.

First, push AI deeper into Search without breaking the economics. That’s the tightrope: make AI-powered search undeniably better while preserving—maybe even improving—the advertising engine that throws off hundreds of billions of dollars. This is the existential problem, because the best AI experience for users is not automatically the best experience for an ad marketplace.

Second, keep building a second and third pillar. That means scaling Google Cloud and pushing Waymo closer to standalone profitability, so Alphabet’s future isn’t a single story about ads. It’s about having multiple businesses that can compound—even if one matures, gets regulated, or gets disrupted.

Third, survive the regulatory era with as much of the moat intact as possible. That’s not just courtroom strategy. It’s learning how to operate under sustained scrutiny, adapt product decisions to new rules, and engage seriously with concerns about market power without voluntarily giving away the advantages that made Google Google.

The hard part is that none of this happens in a vacuum. Alphabet is a giant now, with roughly 180,000 employees. Keeping the intensity and risk appetite of the early days while operating under global scrutiny is a constant strain. Sundar Pichai’s steady, consensus-driven leadership has helped the company function at scale, but it has also fueled criticism that Google hasn’t always moved with enough urgency—especially with AI reshaping the competitive landscape in real time.

Still, the underlying reality is staggering. Alphabet controls a rare combination of assets: global distribution, deep data, massive infrastructure, custom chips, frontier models, and products used by billions of people. That is one of the most formidable competitive positions in business history. Whether it holds through AI’s platform shift and the next wave of regulation will decide the ending of this story—whether the architecture Page and Brin started in a Stanford dorm keeps defining how the world finds information, or becomes the thing that gets rebuilt.

Recent News

Alphabet entered 2026 with a lot moving at once—strong operating momentum, escalating regulatory pressure, and an all-hands sprint to make Gemini feel inevitable. The company said its fourth-quarter and full-year 2025 earnings call would be held on February 4, 2026. A few months earlier, in Q3 2025, Alphabet crossed the $100 billion quarterly revenue mark for the first time, posting $102.3 billion in revenue and $35 billion in net income. Google Cloud kept doing the thing investors have been waiting years to see: it accelerated again, up 34% to $15.2 billion, with operating margins just under 24%.

Regulation remains the biggest wild card. The September 2025 antitrust remedies ruling in the U.S. landed better than many feared: Judge Mehta declined to force a divestiture of Chrome, but he did tighten the screws—restricting default agreements and requiring limited data sharing. Meanwhile, the second major U.S. antitrust case, centered on Google’s ad-tech business, is still headed toward its remedies phase. Both cases are expected to be appealed, and the path to final resolution could stretch into 2027 or 2028.

On the product front, Google continued to push hard on AI. Gemini 3 Pro launched in November 2025, and the Gemini app grew to 650 million monthly active users. In January 2026, Google rolled out Personal Intelligence, linking Gemini to user data across Google services to deliver more personalized assistance. Alphabet also signed a major agreement giving Anthropic access to as many as one million TPUs, another signal that Google wants to be a serious infrastructure supplier in the AI boom—not just a model builder.

Waymo’s momentum continued, too. By late 2025 it was doing 450,000 paid rides per week and announced plans to expand in 2026 to London, Miami, Dallas, Houston, and other cities. But the safety spotlight didn’t go away: the NHTSA opened an investigation after a Waymo vehicle struck a child near an elementary school in January 2026. Waymo was also reportedly in discussions to raise more than $15 billion at a valuation in the $100 to $110 billion range.

And in a headline that grabbed investors’ attention, Berkshire Hathaway initiated a new stake of roughly 17.8 million shares in Q3 2025, estimated at about $4.3 billion.

Links and Resources

- In the Plex: How Google Thinks, Works, and Shapes Our Lives by Steven Levy — The definitive inside account of Google’s culture, technology, and strategy through its first fifteen years

- How Google Works by Eric Schmidt and Jonathan Rosenberg — Google’s former CEO and SVP of Products lay out how they tried to manage innovation at scale

- The Google Story by David A. Vise — An early, accessible history of the company’s founding and rise

- I’m Feeling Lucky: The Confessions of Google Employee Number 59 by Douglas Edwards — A first-person look at the chaotic, fast-growing early days

- Brin, S. and Page, L., “The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine” (1998) — The original Stanford paper describing PageRank and Google’s early search architecture

- Page, L. et al., “The PageRank Citation Ranking: Bringing Order to the Web” (1999) — The technical paper that formalized PageRank

- Alphabet Inc. Annual Reports and SEC Filings — abc.xyz/investor

- United States v. Google LLC, Case No. 1:20-cv-03010 — The DOJ search monopoly antitrust case filings and rulings

- Vaswani, A. et al., “Attention Is All You Need” (2017) — The Google Brain paper that introduced the Transformer architecture

- Waymo Safety Reports — waymo.com/safety — Waymo’s published safety data and autonomous driving performance metrics

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music