Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Corporation: America's Maritime Infrastructure Builder

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture the Port of Savannah in the predawn darkness of 2020. A vessel the size of a small aircraft carrier slides through a newly deepened channel, carrying enough containers to fill 22,000 trucks. Ten years earlier, it couldn’t have made that trip. The water was too shallow. The turns were too tight. Post-Panamax giants like this simply didn’t fit.

So who made it possible?

Not the shipping lines. Not the port authority. And not even the Army Corps of Engineers, even though they paid for much of it. The entity that actually moved the mud—millions of cubic yards of sediment, sand, and rock—was Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Corporation.

Great Lakes is the leading dredging contractor in the United States, focused on the projects that keep America’s ports working and its coastlines standing. It’s been doing this for more than 135 years, and it runs the country’s largest and most diverse dredging fleet—about 200 specialized vessels built for one job: reshaping the seafloor when the economy, the ocean, or both demand it.

Most people—and most investors—have never heard of GLDD. Yet it sits at the intersection of three forces that are only getting stronger: global trade, climate adaptation, and the energy transition. Every container ship that calls on an American port depends on dredged channels. Every beach town that “saves” its shoreline depends on sand being borrowed, moved, and rebuilt. And now, increasingly, offshore wind projects depend on marine construction and seabed preparation that looks a lot like dredging’s next act.

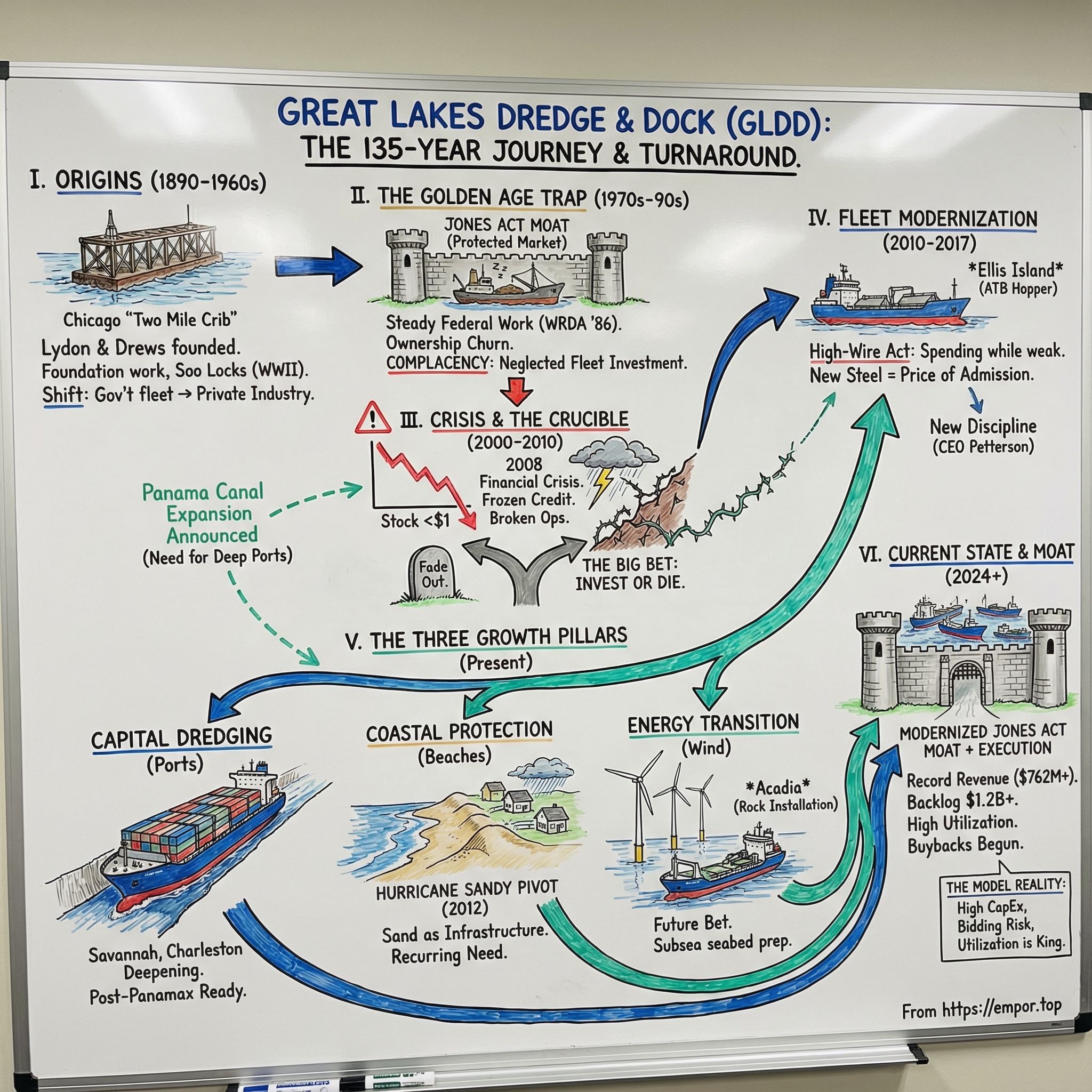

That brings us to the question at the heart of this story: how does a 135-year-old infrastructure company survive technological disruption, near-bankruptcy, and competition against foreign, state-backed rivals—and still come out the other side as the market leader?

The answer is a turnaround you don’t usually see in heavy industry: a painful diagnosis, a bet-the-company fleet modernization, and an industry structure that quietly creates one of the most powerful—and most misunderstood—regulatory moats in American infrastructure.

By the end of 2024, GLDD had revenue of $762.7 million, net income of $57.3 million, and Adjusted EBITDA of $136.0 million—the latter two marking the second-highest results in the company’s history. The bidding environment in 2024 reached $2.9 billion; Great Lakes won 33% of it. That fed a dredging backlog of $1.2 billion at year-end, plus another $282.1 million in low bids and options pending award—enough to give visibility well into 2026.

For investors, GLDD can look like a paradox: a boring business sitting in front of exciting demand. It’s protected by regulation, pushed forward by secular tailwinds, and, right now, executing better than it has in decades. But it’s also a company that traded below a dollar per share during the financial crisis, has a history of uneven returns, and operates in a world where one bad, fixed-price job can erase a year’s worth of profits.

II. What is Dredging & Why Does It Matter?

Before we jump back into Great Lakes’ history and the decisions that almost broke—and then rebuilt—the company, we need to get clear on what dredging actually is. Because once you see it, you start noticing dredging everywhere, even though almost nobody talks about it.

At the simplest level, dredging is removing material from the bottom of a river, lake, harbor, or ocean. It’s earthmoving, just underwater. Great Lakes does it across a wide range of jobs: coastal protection projects that move sand from offshore to rebuild eroding shorelines; maintenance dredging to re-clear channels and harbors as they naturally fill back in with silt; lake and river dredging; inland levee and construction dredging; environmental restoration and habitat work; and other marine construction.

Those projects usually fall into three big buckets.

First is capital dredging: the big, transformative projects that deepen or widen a port so it can handle a new class of ship. When the Panama Canal expansion pushed global shipping toward larger Post-Panamax vessels, ports up and down the U.S. East and Gulf Coasts suddenly had a problem: their channels weren’t deep enough. Fixing that meant dredging entire navigation systems deeper—often going from 40 feet to the mid-40s or beyond—so the new giants could enter and maneuver.

Second is maintenance dredging: the recurring work that keeps the system from quietly breaking. Rivers carry sediment. Tides move sand. Storms rearrange the bottom. Left alone, channels and harbors start to fill in again. Without ongoing maintenance dredging, much of the U.S. navigation network would become unreliable—and in places, unusable—surprisingly fast. This is the industry’s steady baseline: not glamorous, but constant.

Third is coastal protection, often called beach nourishment. Beaches erode in normal conditions, and major storms can erase decades of shoreline in a night. Nourishment is the process of pulling sand from offshore sources and rebuilding beaches and dunes where communities, roads, and property sit right at the edge. This category accelerated after Hurricane Sandy in 2012 made the economics painfully clear.

Post-Sandy analysis found that the Army Corps’ beach nourishment projects in New York and New Jersey saved an estimated $1.3 billion in avoided damages. In plain language: the places with rebuilt dunes and nourished beaches fared dramatically better. The Corps visited impacted areas and saw the pattern firsthand—where nourishment and dunes were in place, homes and infrastructure were more likely to still be standing.

Doing all of this takes equipment that looks like it belongs in a different world. Great Lakes’ fleet centers on three major dredge types: cutter suction dredges, trailing suction hopper dredges, and mechanical dredges, supported by a web of auxiliary vessels and equipment that prepare material, move it, and push it through long hydraulic pipelines.

Trailing suction hopper dredges are essentially ocean-going vacuum ships. They sail along the seabed, suction up sediment into a massive internal “hopper,” then carry it to a disposal site or a place where that material can be used—like rebuilding a beach.

Cutter suction dredges are more like floating industrial factories. They stay in place and use a rotating cutting head to break up hard material, then pump it through pipelines that can run for miles to wherever the material needs to go.

Mechanical dredges look closer to what you’d recognize on land: clamshells or buckets lifting material up and out, often used where precision matters or where conditions don’t suit hydraulic pumping.

Zoom out, and dredging is a meaningful but not enormous global market: valued at about $10.4 billion in 2022, with expectations for moderate growth. What’s more important than the size is the structure. This is a capital-intensive niche dominated by a small set of players—globally by European firms like DEME, Van Oord, Boskalis, and Jan De Nul, plus the Chinese state-owned China Harbour Engineering; and in the U.S. by Great Lakes, Weeks Marine, and Manson Construction.

Van Oord traces its roots back to 1868 and operates globally across dredging, land reclamation, offshore wind, and major marine infrastructure. DEME was formed in 1991 through a merger near Antwerp and has become a major name in dredging and offshore energy, with operations spanning environmental works and marine construction.

But the U.S. market has a twist that changes everything: the Jones Act. We’ll unpack it later, but for now, here’s the punchline—foreign dredging companies can’t just show up and compete for domestic U.S. work. That restriction shapes the entire competitive landscape and helps explain why a company like Great Lakes can be both highly cyclical and structurally protected at the same time.

One more foundational detail: this is specialty construction done from floating platforms, and the biggest buyer is the U.S. federal government, primarily through the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

For investors, the key insight is simple. Dredging is essential, specialized, and, in the U.S., unusually protected. There’s no substitute. If you want bigger ships in your port, or a navigable channel after nature fills it back in, or a rebuilt coastline after storms, someone has to move the mud. And doing it at scale requires vessels that cost tens to hundreds of millions of dollars and take years to build.

III. The Founding Era & Rise (1890–1960s)

Great Lakes’ story starts in Chicago in 1890, right in the middle of America’s industrial surge. Back then it wasn’t “Great Lakes” yet. It was a partnership: William A. Lydon & Fred C. Drews.

Their first big job tells you everything about the kind of company this was going to be. Chicago needed clean drinking water, but the near-shore lake water was getting increasingly contaminated as the city exploded in size. The solution was simple in concept and brutal in execution: move the intake farther out into Lake Michigan, away from the pollution.

Lydon & Drews built an offshore tunnel from Chicago Avenue to a new water crib farther from shore. It became known as the “Two Mile Crib,” and it mattered because it wasn’t a monument or a headline—it was a lifeline. Lydon served as the firm’s engineer and first president; Drews, with marine construction experience, ran operations as general superintendent. They set up shop in the Unity Building on Dearborn Street (the building later became Chicago’s Chamber of Commerce), and then went to work doing the kind of underwater construction that most people never see, but everyone depends on.

From there, growth came fast. Through the 1890s the company expanded beyond Chicago and opened satellite operations in the major Great Lakes cities. It took on shoreline work for Chicago’s Columbian Exposition in 1892 and helped build foundations for what is now Navy Pier. The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, in particular, was a proving ground—massive development along the lakefront, a hard deadline, and huge civic visibility. Lydon & Drews was in the middle of it.

In the early 1900s, the company scaled up through acquisition, absorbing four Chicago firms: Chicago Dredge & Dock Company, Green Dredging Company, Hausler & Lutz, and McMahon & Montgomery. With that consolidation came a name change—first to Chicago & Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Company in 1903, then, more cleanly, to Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Company. The company incorporated in New Jersey in 1905, drawn by the state’s favorable corporate laws.

By then, this wasn’t a two-man operation anymore. The fleet had grown to thirteen dredges and ten tugboats, and the work had broadened: dredging, pile-driving, foundations, bridges, breakwaters, even lighthouses—projects in Chicago and across the Great Lakes that steadily expanded the company’s footprint and capabilities.

Between the wars, Great Lakes became the quiet force behind much of Chicago’s modern shoreline. It performed shoreline reclamation for the Adler Planetarium, Shedd Aquarium, Soldier Field, Northerly Island (built for the 1933 World’s Fair and later the site of Meigs Field), and the Field Museum. It also did landfill work that reshaped Lincoln Park, Jackson Park, Grant Park, and Chicago’s nine-mile shoreline. And when the city needed heavy marine construction, Great Lakes was there too: foundations and approaches for the Michigan Avenue Bridge, the Outer Drive Bridge on Lake Shore Drive, and sections of the lower level of Wacker Drive.

World War II elevated that reputation from local to national. Great Lakes earned the Navy’s E-Flag for its work on the MacArthur Lock at Sault Ste. Marie—part of the Soo Locks system that connects Lake Superior to the lower Great Lakes. The Corps of Engineers called it the most reliable lock on the Great Lakes. And reliability wasn’t a nice-to-have; the Soo Locks were—and still are—critical infrastructure, enabling the movement of iron ore that powered America’s industrial base.

After the war, the company pushed beyond the Great Lakes, participating in extensive oil-related dredging in the Gulf of Mexico and taking on bridge and marine construction projects around the country. Meanwhile, a structural shift was brewing that would define the industry for decades: the Army Corps of Engineers began pulling back from operating its own dredging fleet, reducing it to what it considered necessary for emergencies and national defense.

That change didn’t just happen on its own. Great Lakes’ president at the time, John A. Downs, played a key role in promoting legislation that ultimately mandated the Corps’ fleet reduction. It was a classic move in American infrastructure history: private industry pushing government out of day-to-day operations and into the role of planner, funder, and contract-awarder. The result was a more robust private dredging sector—and a market structure that still governs who gets to do this work.

By the 1960s and into the years that followed, Great Lakes was no longer just a Chicago contractor with a few dredges. It had become a scaled operator with a fleet, a national footprint, and political influence—one that was about to benefit from an era of steady federal contracting, protected competition, and the illusion that the good times would last forever.

IV. The Golden Age & Complacency (1970s–1990s)

From the mid-1970s through the 1990s, Great Lakes looked like it had reached the easiest stage of any industrial company’s life: comfortable maturity. Federal infrastructure spending stayed healthy. The customer—the U.S. government, especially the Army Corps—was steady and predictable. And the Jones Act effectively fenced off the domestic dredging market from foreign competition.

The Jones Act—Section 27 of the Merchant Marine Act of 1920—is the legal backbone of U.S. maritime protectionism. In plain terms, it says that vessels working in domestic commerce must be American-owned and controlled, U.S.-built, U.S.-flagged, and crewed by Americans. Supporters argue that opening any part of the Jones Act trades threatens national defense readiness, homeland security, and economic resilience. Critics counter that it raises costs and slows down infrastructure work by blocking access to cheaper—or more advanced—foreign-built ships.

Either way, the policy has real scale behind it: roughly 40,000 Jones Act vessels operate in domestic trades, supporting nearly 650,000 American jobs and about $150 billion in annual economic impact. The ecosystem effects are meaningful too—industry advocates often cite that for each direct maritime job, several more are supported indirectly, contributing tens of billions in labor compensation.

For dredging, the wall got even taller in 1988, when Congress clarified that transporting “valueless material,” like dredge spoil (and even municipal solid waste), still counts as waterborne transport—and therefore requires Jones Act-qualified vessels. That detail matters because dredging isn’t just digging; it’s digging and moving. Once spoil transport fell clearly under Jones Act rules, it effectively meant that dredging work in U.S. waters—ports, channels, rivers, beaches—had to be done with American-qualified equipment.

For Great Lakes, that regulatory structure functioned like a moat. European leaders like DEME and Van Oord could build technologically superior fleets and execute massive projects overseas, but they couldn’t simply sail into the U.S. market and bid on domestic work. Chinese state-owned dredging firms, with their ability to price aggressively thanks to subsidies and scale, were locked out entirely. Great Lakes, sitting inside the fence, was positioned as the largest domestic player in an essential, government-funded industry.

Then came more fuel for the machine. In 1986, Congress passed the Water Resources Development Act (WRDA), often described as “Deep Ports” legislation, aimed at improving U.S. transportation infrastructure by deepening major ports. Great Lakes, as the leading dredging contractor in the country, captured a meaningful share of that work—and it also attracted attention from would-be owners who liked what they saw: protected market, recurring federal spending, and critical infrastructure demand.

That kicked off a long stretch of ownership churn. In 1979, Great Lakes International Inc. (GLI) became the holding company for Great Lakes Dredge & Dock. Between 1985 and 1998, GLI changed hands multiple times, including ownership by Itel Corporation, then Blackstone Dredging Partners, and later Vectura Holding Company (Citigroup). Management shifted too. In early November 1985, GLI was taken over by real estate magnate Sam Zell, who later sold the company in 1992 to Blackstone Investment Group of New York.

Seen from the outside, the carousel told two stories at once. On the one hand, dredging looked like a great business to own: steady federal revenue, high barriers to entry, and an industry that almost never disappears. On the other hand, constant transitions are rarely a recipe for patient, multi-decade capital planning—especially in a business where the real competitive advantage floats.

Because the real issue in this era wasn’t demand or market position. It was the fleet.

Dredges are some of the most capital-intensive assets in infrastructure. They can last 20 to 30 years or more, but only with relentless maintenance, periodic overhauls, and—eventually—replacement. And in asset-heavy businesses, there’s a trap that springs quietly: when you’re making good money on old equipment, it’s incredibly tempting to keep running it, keep patching it, and keep taking the cash instead of sinking it into new steel.

That’s what happened. Great Lakes generated solid returns while its fleet aged in place. Meanwhile, global competitors were investing into newer vessels: better fuel efficiency, deeper capabilities, and more advanced control systems. Great Lakes was living off yesterday’s capital spending—coasting, in the best market it would ever have.

By the late 1990s, the fleet was getting old. The company still had the moat. It still had the contracts. But the technological gap was widening, and the bill for deferred investment was starting to come due.

V. Crisis & Near-Death Experience (2000–2010)

The 2000s hit Great Lakes like a rogue wave. The company had spent years living off an aging fleet in a protected market. Then, almost all at once, the outside world changed: costs spiked, credit disappeared, and the gap between “good enough” equipment and world-class capability suddenly mattered. What followed was a near-death experience that rewired the company’s instincts—and set up the bet that would define the next decade.

The ownership carousel didn’t help. In 2003, GLI was acquired by Madison Dearborn Partners for $340 million. Three years later, Madison took it public in a way that was very of-the-moment: a merger with its special-purpose acquisition company, Aldabra Acquisition Corp. After the deal closed in 2006, Aldabra changed its name to Great Lakes Dredge & Dock and began trading on NASDAQ. Madison exited fully by 2009.

In hindsight, the timing was brutal. Great Lakes had just re-entered the public markets as several pressures converged: the fleet was increasingly outmatched, steel and fuel were getting more expensive, and the broader economy was heading straight into the 2008 financial crisis.

That crisis didn’t start with dredging, of course. It started with U.S. housing—mortgage-backed securities and the derivative machine built on top of them. As those assets fell apart in 2007, liquidity began to evaporate across the financial system. By September 2008, Lehman Brothers collapsed, markets seized up, and the Great Recession followed.

For Great Lakes, the effects were immediate and concrete. Construction and infrastructure activity slowed. Credit markets froze—exactly when the company most needed financial flexibility to invest in new equipment. Debt covenants became a real threat, and the balance sheet went from “stretched” to “existential.”

The stock chart tells the story in a single image: a company that traded above $20 not long after going public fell to below $1. That wasn’t just a painful mark-to-market moment. At penny-stock levels, equity capital is essentially off the table. And in 2008–2009, debt capital was off the table for just about everyone. Great Lakes was staring at the worst possible combination: shrinking access to financing, rising operating costs, and a fleet that was getting older by the month.

And yet, even as the walls were closing in, a second timeline was starting—one that would eventually give the U.S. dredging industry its biggest demand surge in generations.

In April 2006, Panamanian President Martín Torrijos formally proposed expanding the Panama Canal. Later that year, a national referendum approved the project by a wide margin, and the Panamanian government moved forward. Construction began in 2007. The plan was straightforward but massive: double capacity by adding a third, wider lane of locks. Work ran from 2007 until 2016, and the expanded canal opened for commercial operations on June 26, 2016.

For dredging, the announcement was a starting gun. The canal expansion accelerated the shift to larger, Post-Panamax ships. Industry experts said that nearly 80 percent of ships on order were Post-Panamax, and officials up and down the East and Gulf Coasts began making the same argument: deepen the ports, and you can pull more traffic that historically landed on the West Coast and moved east by rail.

That logic put every major East and Gulf Coast port on the clock. Channels needed to be deeper. Turns and berth areas needed to be widened. Ports that could handle the new ships would win; ports that couldn’t would risk being sidelined.

It was the setup for a capital dredging boom that could last decades—if Great Lakes could survive long enough to participate in it.

Survival meant doing things that were painful but unavoidable. The company restructured debt, sold non-core assets, and cut its workforce. New leadership and the board dug into the business and reached a hard conclusion—later described as a deep dive into operational and financial performance—that Great Lakes wasn’t just financially stressed. It was operationally broken.

Out of that diagnosis came a strategy that was simple to say and terrifying to execute: invest or die.

The coming wave of port-deepening megaprojects required capabilities Great Lakes didn’t have. If the company couldn’t modernize its fleet, it wouldn’t just miss the next cycle—it would become irrelevant inside its own protected market. So Great Lakes faced a choice that didn’t feel like a choice at all: bet the company on new steel, or slowly fade out with the old fleet that had once made it dominant.

VI. The Big Bet: Fleet Modernization (2010–2015)

The fleet modernization program Great Lakes kicked off around 2010 was a high-wire act disguised as capital planning. This was a company that had nearly gone under, with a battered balance sheet and a stock still clawing its way back from the abyss, deciding to spend hundreds of millions on new vessel construction anyway.

The logic was brutal and simple: the next generation of port-deepening work was coming, and Great Lakes didn’t have the tools to win it. The only way back into the fight was new steel.

One of the signature builds to come out of this era was the Ellis Island, an articulated tug barge (ATB) hopper dredge. It was delivered in November 2017 after completing U.S. Coast Guard and American Bureau of Shipping sea trials—late enough that it became a visible proof point of a bet that had been placed years earlier.

As David Simonelli, President of the Dredging Division, put it at delivery: “We are excited to take delivery of this advanced vessel which improves the competitiveness of our hopper group and represents a substantial reinvestment in our fleet. The Ellis Island significantly increases the United States commercial Jones Act hopper fleet capacity as the largest hopper dredge in the United States market.”

CEO Lasse Petterson framed it even more broadly: “This addition to our fleet represents a great milestone in Great Lakes’ history. The Ellis Island is capable of meeting the current and future U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’, State and U.S. Ports’ deepening, coastal protection, coastal restoration and maintenance dredging infrastructure demands. The Ellis Island’s haul capacity and dredging systems will yield more efficient and faster project execution.”

The Ellis Island wasn’t just a single new ship—it represented a design decision about how Great Lakes would modernize. The vessel and its accompanying tug, Douglas B. Mackie, used an ATB configuration: a pairing that could deliver serious hopper capacity without the full cost structure of a traditional self-propelled hopper dredge. Along with the Galveston, Liberty, Terrapin, Dodge and Padre Islands, Great Lakes’ hopper fleet became the largest in the U.S. dredging industry, including the 15,000-cubic-yard-capacity barge Ellis Island.

Making this fleet real was hard in two different ways.

First, the engineering. These vessels needed to reach deeper than much of the domestic fleet historically could, handle tougher materials in capital channel work, and run efficiently enough to win bids—even against older, fully depreciated equipment that could be operated cheaply.

Second, the financing. Great Lakes was still in recovery mode, raising capital and taking on debt while the memory of near-bankruptcy was fresh.

And then there was the structural gut punch: the Jones Act. The same law that walled off the U.S. market from foreign dredging giants also forced Great Lakes to build in American yards at American prices. In practice, large U.S.-built ships can cost four times—or more—than the global market price. That meant modernization wasn’t just a strategic choice. It was an expensive one, made more expensive by the very moat that kept competitors out.

The risk stack was enormous. Would the port-deepening wave materialize fast enough? Would Congress fund it? Would the vessels perform the way the spreadsheets promised? And would Great Lakes stay solvent long enough to see the upside?

Then the work started showing up.

Savannah moved forward with its massive harbor expansion to deepen the channel for modern container ships. Charleston, Miami, Jacksonville, Boston—port after port advanced from planning to contracts as the post-Panamax era stopped being theoretical and started arriving at the dock.

Great Lakes announced $87 million in new awards, including $47 million for the Charleston I port deepening project. It was also the low bidder on Charleston II—about $279 million and expected to be the largest dredging project in Army Corps of Engineers history—with a formal award expected in October 2017.

This is what the company had been buying with all that risk: a seat at the table for the biggest projects in a generation. Great Lakes survived the crisis, rebuilt its fleet, and finally re-entered the market with modern capability. Inside the domestic fence of the Jones Act, it was once again competitive on technology and execution—right as the port-deepening wave arrived.

VII. The Beach Nourishment & Coastal Protection Boom (2012–Present)

Port deepening was the capital-project wave that made fleet modernization worth the risk. But at the same time, another line of work was becoming just as strategically important for Great Lakes over the long run: coastal protection, better known to most people as beach nourishment.

Hurricane Sandy was the catalyst. It hit the East Coast on October 29, 2012, and tore through the shorelines of New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut, leaving behind more than $50 billion in damage. In the aftermath, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ New York District moved into coastal restoration mode. And the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management—BOEM—supported states, localities, and federal agencies as they searched for OCS sand sources to rebuild beaches and dunes.

Sandy didn’t just create a backlog of repair work. It changed minds. Coastal engineers had argued for years that beaches aren’t just nice-to-have recreation. They’re working infrastructure—sacrificial buffers that absorb wave energy and protect what sits behind them. Post-Sandy analysis put a number on that idea: the Army Corps’ beach nourishment projects in New York and New Jersey were estimated to have saved about $1.3 billion in avoided damages. The takeaway was hard to ignore, and the Corps began applying those findings to improve how future nourishment projects are planned and built.

Money followed urgency. New York City’s recovery effort was backed by $15 billion of federal disaster recovery grants, plus billions more in City capital funds, aimed at rebuilding homes, repairing NYCHA buildings, supporting businesses, and hardening infrastructure—especially along vulnerable coastlines. The Department of the Interior invested $787 million in Sandy recovery to repair damaged national parks and wildlife refuges, restore and strengthen marshes and wetlands, and reconnect waterways. Beyond resilience, these programs were also framed as job-creating, get-it-done-now public works.

For Great Lakes, this work looked nothing like a port deepening mega-project. Port projects are lumpy: years of permitting, years of politics, then one huge job—and then, often, nothing at that port for a long time. Beach nourishment is the opposite. Beaches erode steadily. Storms accelerate the damage. And once a community commits to a protected beach, it signs up for maintenance: periodic replenishment, often every five to ten years.

Great Lakes’ fleet was built for this kind of repetition. On the Gulf Islands National Seashore project, the hopper dredges Ellis Island and Liberty Island hauled more than 7.5 million cubic yards of sand from open-ocean borrow areas on a long, roughly 25-mile run to the islands. In another phase of the same broader effort, Ellis Island moved more than 2 million cubic yards from distant offshore sources to rebuild and reinforce beachfront. And when the job called for a different tool, Great Lakes deployed one: the cutter suction dredge Alaska was used on Phase 4, borrowing more than 1.5 million cubic yards of offshore sand.

Just as important as the work itself was who paid for it. Port deepening is heavily federal, and overwhelmingly tied to the Army Corps. Beach nourishment pulls in a broader mix—federal, state, and local—often with funding mechanisms that don’t rise and fall in lockstep with the federal budget cycle. That diversification matters when you’re trying to smooth out a business that can otherwise swing wildly year to year.

You can see the recurring, programmatic nature in projects like Phase III of the Post Florence Renourishment Project. It used 2,012,850 cubic yards of sand sourced from the Offshore Dredged Material Disposal Site tied to the Morehead City Federal Navigation Project, rebuilding four reaches totaling 9.4 miles of beach in Emerald Isle.

Over time, Florida, New Jersey, North Carolina, and other coastal states became major nourishment markets. And there’s a political tailwind baked in: tourism economies depend on having beaches. The hotel and tourism lobby tends to show up, year after year, to support funding that keeps the shoreline in business.

For investors, coastal protection adds a different kind of durability to Great Lakes: more recurring revenue, broader geographic and customer exposure, and often better margins than the toughest fixed-price port jobs. Most of all, demand is driven by forces that don’t negotiate—storms, erosion, and rising seas. As coastal threats grow, the need for this work doesn’t fade. It compounds.

VIII. The Energy Infrastructure Pivot (2015–Present)

By the mid-2010s, Great Lakes had rebuilt itself around two demand engines: deeper ports and rebuilt beaches. Then a third opportunity started taking shape offshore—one that could be even bigger over the long arc: wind.

Great Lakes has been working to extend its core marine-construction skill set into the offshore wind industry, a market the U.S. is only now beginning to build at scale. Europe—especially countries like Denmark, Germany, and the UK—had already spent the prior decade-plus turning offshore wind into a real industrial supply chain. The U.S., by comparison, lagged by roughly 15 years. But the direction of travel was clear: state renewable mandates and federal support were pushing projects forward, and building them would require the same kind of heavy, specialized work Great Lakes already knew how to do—just in a new setting.

A marquee example is Vineyard Wind 1, located about 24 kilometers, or 15 miles, south of Martha’s Vineyard. The project features 62 fixed-bottom turbines with a combined nameplate capacity of 804 megawatts—enough, at peak production, to supply the equivalent of about 400,000 homes.

So where does a dredging company fit into an offshore wind farm?

Not by “dredging” in the classic sense of deepening a channel. The key is what happens at the seafloor around each turbine foundation. These turbines sit on monopile foundations, and the ocean does what the ocean always does: currents and waves try to scour away the sediment at the base. To keep the foundation stable, developers need scour protection—rock placed in engineered patterns around the monopile.

That work is its own niche, and it requires its own kind of ship: a subsea rock installation vessel.

Great Lakes’ big offshore wind bet is a Jones Act-compliant subsea rock installation vessel called Acadia. It’s based on an Ulstein design, with an overall length of 140.5 meters (461 feet), a breadth of 34.1 meters (112 feet), and accommodations for 45 people. It can carry up to 20,000 tonnes of rock and deposit it precisely on the seabed at foundation locations across a wind project site.

Acadia is the spearhead because it fills a glaring gap in U.S. capability. The vessel was ordered in 2021. First steel was cut in July 2023. And on May 2, 2024, the keel was laid at Philly Shipyard in Philadelphia. If delivered as planned in the latter half of 2025, it becomes the only Jones Act-compliant rock placement vessel in the U.S. commercial fleet—an important distinction in a market where the equipment you have determines which projects you can even bid.

Philly Shipyard has said the award is valued at about $197 million. Great Lakes also negotiated a right of refusal on a second vessel; if both ships were ordered, the total two-ship program would be approximately $382 million.

Importantly, Great Lakes didn’t build this on pure speculation. It has secured contracts tied to Equinor’s Empire Wind 1 and Ørsted’s Sunrise Wind projects. Management has positioned offshore wind as a long-duration growth opportunity, rooted in U.S. decarbonization and clean energy objectives—and as a way to apply Great Lakes’ offshore execution experience to a market with a long runway.

But this pivot comes with real downside risk, because the U.S. offshore wind industry has been messy. Projects have been hit by cost overruns, cancellations, and shifting economics. In Massachusetts alone, 75% of the power in the offshore wind pipeline was eliminated when Commonwealth Wind and SouthCoast Wind scrapped their contracts last year, arguing the projects were no longer viable under the prices previously negotiated.

And then there’s policy risk. A presidential executive order pausing new offshore wind leases adds another layer of regulatory uncertainty. Even if existing projects proceed, slower leasing and permitting would likely compress the future pipeline—exactly the thing you want to be expanding when you’re taking delivery of a highly specialized new vessel.

Great Lakes is trying to manage that risk by keeping Acadia flexible. The vessel is also well suited to international offshore wind work, and to rock protection in adjacent markets—pipelines for oil and gas, carbon capture, telecommunications, and power cables. The company has said it is pursuing and bidding on additional work for Acadia both domestically and internationally, with projects planned for 2026 and beyond.

The logic is straightforward: offshore wind is a multi-decade market, the work is adjacent to Great Lakes’ core capabilities, and being first with Jones Act-compliant rock-installation capacity can be a meaningful edge. But the timing matters, and the industry’s growing pains aren’t over.

IX. Modern Competition & The Foreign Threat

To understand Great Lakes’ competitive position, you have to hold two ideas in your head at the same time.

First: inside the U.S., dredging is basically an oligopoly. There just aren’t many companies with the people, the safety systems, the bonding capacity, and—most importantly—the specialized fleet to take on major federal and state work.

Second: outside the U.S., the industry is dominated by giants. And some of them don’t play by the same economic rules.

Start at home. Great Lakes’ most credible rivals are other American operators with real fleets and decades of execution history.

Weeks Marine, founded in 1919, is one of the largest dredging and marine construction companies in the U.S., with operations that extend beyond the U.S. into Canada. It has the track record and breadth to show up on the biggest bids and win.

Manson Construction is another heavyweight, with a long history in dredging and marine construction and a fleet that lets it compete head-to-head with Great Lakes on major projects.

There are also other capable players, like Cashman Dredging and Marine Contracting, that can be serious competitors depending on the job and geography.

In this kind of market, competition is real—but it’s not chaos. With only a handful of companies able to bid at the top end, the fight is less about marketing and more about operational credibility. Customers care about who can execute without incidents, who stays compliant with environmental requirements, and who finishes the job without turning a fixed-price contract into a disaster. Relationships with the Army Corps of Engineers and other public agencies matter too—not as favoritism, but as the accumulated trust that you can deliver.

The more existential threat comes from abroad, especially from Chinese state-backed firms that have grown by winning international work with scale and pricing that private companies struggle to match.

CCCC Dredging, a subsidiary of China Communications Construction Company Ltd., is a major Chinese dredging and marine contracting operation. It works across dredging and land reclamation and offers services that extend into surveys, engineering, and other hydraulic activities. It has operated in more than 20 countries, maintains offices in 10 countries, and employs more than 5,000 skilled professionals.

Backed by state financing and plugged into China’s Belt and Road infrastructure push, Chinese dredging companies have taken share across Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America. Their advantage isn’t just lower labor or cheaper steel. It’s that they can treat bids as geopolitics: they can price aggressively, even below cost, as a state-subsidized investment in influence and access.

That’s exactly why the U.S. domestic market matters so much—and why the Jones Act fight never goes away. Industry groups frame it in blunt terms: the U.S. maritime sector opposes anything that would weaken the defense industrial base, the skilled workforce, and hundreds of thousands of family-wage jobs, and administrations of both parties have historically kept domestic maritime out of free trade agreements.

Critics argue the Jones Act raises costs and reduces efficiency. The dredging industry and its allies argue that opening domestic work to foreign fleets would hollow out U.S. capability that’s essential in emergencies and national defense.

The Navy has been explicit about where it stands. It has warned that repealing the Jones Act would “hamper [America’s] ability to meet strategic sealift requirements and maintain and modernize our naval forces.”

For Great Lakes and the other U.S. incumbents, that’s the core reality: the Jones Act is the moat. It’s not something they invented. It exists for national policy reasons that go way beyond dredging. But it is durable, it has survived for more than a century, and it dictates who can compete for the work that keeps American ports and coastlines functioning.

Then there’s Europe: DEME, Van Oord, Boskalis, Jan De Nul. They can’t simply sail into the U.S. domestic market and bid the way they do overseas, but they still matter because they set the global benchmark. DEME, for example, operates the world’s first dual-fuel dredging vessels and has spent decades executing complex work—strategic waterways, port developments, land reclamation, and even artificial islands.

And in offshore wind, the European lead is even more pronounced. They’ve been building wind farms at industrial scale for years, with specialized vessels and hard-earned operational lessons the U.S. is still acquiring in real time. That’s part of why Great Lakes’ approach involves partnering with European developers like Equinor and Ørsted: it’s a way to participate now, learn fast, and build domestic capability—before the next phase of the market becomes truly competitive.

X. Business Model Deep Dive

So how does Great Lakes actually make money—and why can the same company look like a cash machine in one year and a headache in the next?

Start with the simplest truth: in dredging, what you’re doing matters just as much as how well you’re doing it. At the end of 2024, capital and coastal protection projects made up 94% of GLDD’s backlog, and those categories tend to carry better margin potential than routine maintenance work. Mix is destiny here.

Capital dredging is the marquee stuff: deepening ports, widening channels, reworking navigation systems so larger ships can get in and out. These are the jobs that demand the most capable vessels, the deepest engineering bench, and the most disciplined project management. They’re often multi-year and can run into the hundreds of millions of dollars. When Great Lakes prices and executes well, capital work can be highly profitable. When it doesn’t, the damage can be just as large.

Maintenance dredging is the industry’s baseline. Channels naturally fill in; the system constantly degrades unless someone keeps clearing it. The work is steadier, but more commodity-like—tighter margins, more price pressure, and less room for error. Demand is real and recurring; the variable is how much funding the Army Corps has in any given year.

Coastal protection and beach nourishment sits between those two poles. It’s repeating work—beaches erode and storms reset the clock—often funded through a mix of federal, state, and local sources. It can be less “winner-take-all” than some port megaprojects, and it helps smooth out the lumpiness that comes with capital dredging cycles.

Customer concentration is the next big driver. In 2024, about 57% of dredging revenue came from federal agencies. That’s a double-edged sword. The federal government is a reliable payer, and Army Corps work comes with established processes and predictable payment terms. But it also ties Great Lakes to the rhythms of Washington: budgets, shutdown risk, shifting priorities, and the simple fact that politics can delay projects even when the need is obvious.

Then there’s the heart of the business model: bidding.

Most Army Corps projects are awarded through competitive bids. That means Great Lakes is constantly making high-stakes forecasts—estimating teams have to price multi-year work with moving parts they can’t fully control: weather windows, material conditions, equipment performance, production rates. Bid too high, and you don’t win. Bid too low, and you might win a contract that turns into a financial sinkhole.

In 2024, the bid market reached $2.9 billion, and Great Lakes won 33% of it. That’s a sign the company is competitive on both price and capability. It also means it didn’t win most of what it pursued—which is normal in a bid-driven market, and a reminder that this is not a “sell more licenses” kind of business. You earn revenue by winning discrete fights, one project at a time.

All of this sits on top of the industry’s defining constraint: capital intensity.

Great Lakes is always spending. In Q3 2024 alone, capital expenditures included $19.4 million toward construction of Acadia, $13.6 million for Amelia Island, and $5.4 million for maintenance and growth. That’s the reality of running a fleet where your competitive edge is literally steel in the water.

And these aren’t small purchases. Dredging vessels are massively expensive, especially under Jones Act requirements that push construction into U.S. shipyards at U.S. costs. The Ellis Island and its tug likely cost well over $100 million. Acadia is valued at roughly $197 million. Once you commit to builds like that, you can’t “undo” them if the market turns.

The same Jones Act that protects Great Lakes from foreign competition also raises the company’s cost base. European competitors can often build comparable vessels in lower-cost yards abroad. Great Lakes pays the American premium—and that puts structural pressure on returns unless the fleet stays busy and the work is priced rationally.

Which brings us to the metric that matters more than almost any other: fleet utilization. A dredge sitting idle is just expense—crew, maintenance, depreciation—without revenue to cover it. A dredge that rolls from project to project can throw off meaningful returns. The operational game is matching the fleet to the pipeline: enough capacity to capitalize on boom periods, without dragging too much unused equipment through the slow ones.

Labor makes that balancing act harder. These crews are specialized, often unionized, and the work is demanding and regional. Many projects are seasonal, and some have environmental constraints—beach work, for example, can’t always proceed during turtle nesting season. Keeping the right people trained, scheduled, and retained isn’t a footnote; it’s part of execution.

Put it together and you get Great Lakes’ signature financial profile: earnings that swing based on project timing and mix, heavy capital spending that can consume cash, meaningful operating leverage when utilization is high, and real execution risk—because in this business, one badly estimated or poorly executed job can erase the profit you expected to make on several others.

XI. The Inflection Points of the Last Decade

With Great Lakes, the story doesn’t hinge on one grand “reinvention.” It hinges on a handful of moments where timing, policy, and hard choices either opened the door—or slammed it shut. Over the last decade-plus, a few inflection points changed what this company could be.

2007–2009: Panama Canal Expansion Announcement + Financial Crisis

The Panama Canal expansion, proposed in 2006 and moving into construction in 2007, effectively fired the starting gun for the port-deepening cycle. Bigger ships were coming, and U.S. ports would either deepen or fall behind.

But Great Lakes almost didn’t live to see it. The financial crisis hit when the company was already vulnerable, starving it of financing and flexibility right when it needed both. Ironically, the canal expansion’s delays helped. The expansion was initially expected to be completed by August 2014, timed to the canal’s 100th anniversary, but setbacks pushed completion back. That extra time gave Great Lakes a runway to stabilize—and to start building the fleet it would need to compete for the work the expansion would ultimately trigger.

2010–2015: Fleet Modernization

This was the bet-the-company period, and it was as simple as it was dangerous: spend heavily on new vessels while still financially fragile, or accept a future of smaller, lower-value maintenance work while competitors captured the lucrative capital projects.

The deliveries of modern hoppers like Ellis Island and Liberty Island weren’t just “new assets.” They were the price of admission for the biggest port-deepening jobs. Without them, Great Lakes wouldn’t have had the capability to win—and execute—at the top end of the market.

2012: Hurricane Sandy

Sandy didn’t just damage coastlines. It reset the conversation about what beaches and dunes are: not amenities, but infrastructure.

Funding followed. In 2013, BOEM received $13.6 million through the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act, and in 2016 an additional $2.7 million, to address critical needs for OCS sand and gravel in coastal areas undergoing recovery and rebuilding. The bigger shift was structural: Sandy triggered a sustained increase in beach nourishment and coastal protection investment that has continued since.

2017: Leadership Change

In May 2017, Lasse Petterson became CEO. His background wasn’t “career dredging”—it was large-scale project execution in complex, high-stakes environments.

Most recently before Great Lakes, Petterson served as a private consultant to oil and gas clients and previously was Chief Operating Officer and Executive Vice President at Chicago Bridge and Iron (CB&I) from 2009 to 2013, responsible for engineering, procurement, and construction operations and sales. Before CB&I, he was CEO of Gearbulk, which operates one of the world’s largest fleets of gantry-craned open hatch bulk vessels. He also served as President and COO of AMEC Americas, and spent roughly two decades at Aker Maritime in executive and operational roles.

The through-line: disciplined execution. For a company where one poorly run fixed-price job can wreck a year, that kind of operational rigor matters.

2021: Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, signed on November 15, 2021, authorized $1.2 trillion in transportation and infrastructure spending, including $550 billion in new investments and programs.

For Great Lakes’ world, the headline was ports and waterways. The IIJA invested more than $16.7 billion to improve infrastructure at coastal ports, inland ports and waterways, and land ports of entry. It also provided $2.25 billion for Port Infrastructure Development Program grants and, in total, $17.4 billion for ports and waterways across agencies including the Army Corps, DOT, Coast Guard, GSA, and DHS.

And the funding environment stayed strong. The 2024 Energy and Water Appropriations Bill provided a record $8.7 billion to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The 2023 Disaster Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act also allocated $1.5 billion for infrastructure repairs and beach renourishment projects.

In other words: more money, more projects, and a longer runway for both port work and coastal protection.

2024: Record Financial Performance

By the end of 2024, the turnaround arc showed up clearly in the numbers. Great Lakes finished the year with revenue of $762.7 million, net income of $57.3 million, and Adjusted EBITDA of $136.0 million. As of December 31, 2024, dredging backlog stood at $1.2 billion.

Revenue rose about 29% year over year, gross profit more than doubled, and backlog reached a record level. The company also added capacity with the new Galveston Island dredge, while offshore energy expansion remained positioned as an additional growth vector.

This is what it looks like when fleet modernization, supportive funding, and solid execution line up at the same time. The question now is the one that always matters in heavy infrastructure: is this the top of a cycle, or the start of a structurally higher level of profitability?

XII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

If you want to start a dredging company in the U.S. and compete at the top end, you don’t just need a website and a bid desk. You need a fleet. And that fleet costs hundreds of millions of dollars, takes years to build, and—thanks to the Jones Act—has to be built in American shipyards at American prices.

Then you run into the non-obvious barriers. The Army Corps of Engineers doesn’t hand out megaprojects to first-timers. Contractors are vetted over years, sometimes decades, and the real craft of the business—estimating, managing risk, executing safely in tight environmental and weather windows—only comes from doing the work. At meaningful scale, “new entrant” is basically a theoretical concept.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

The Jones Act cuts both ways. It protects U.S. dredgers from foreign competition, but it also funnels large vessel construction into a small number of domestic shipyards that can actually build these ships. That limited yard capacity translates into real pricing power for suppliers.

On top of that, dredging is made of the stuff you can’t negotiate with: steel and fuel. Great Lakes doesn’t set those prices, and swings in either can show up quickly in project economics. The company can soften the blow with long-term relationships and multi-vessel build programs, but it can’t wish away the reality that its supply base is constrained and its inputs are volatile.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

On the demand side, the biggest customer is still the federal government—mainly the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers—and the Corps buys dredging the way you’d expect: structured procurement, competitive bidding, and constant pressure on price.

State and local buyers have their own constraint: budgets. Even when the need is urgent—after storms, or when a port is losing competitiveness—funding and politics can slow decisions.

But here’s the counterweight. For many large projects, there aren’t many credible bidders. And once a job begins, switching contractors is practically impossible. Mid-project switching costs are enormous, and the risk of disruption is unacceptable. So buyers have leverage at bid time, but far less leverage once the work is underway.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

For most of what Great Lakes does, there isn’t a substitute. If a channel is too shallow, you either dredge it or you accept smaller ships and less commerce. If a beach community wants a restored shoreline and protective dunes, you need sand moved from somewhere else and placed with precision.

There are alternatives at the margins—living shorelines and other nature-based approaches can help in certain settings—but they don’t replace dredging for navigation, and they don’t scale to the kinds of engineered beach and storm-buffer systems many coastal communities rely on.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE-HIGH

In the U.S., it’s an oligopoly: a small group of contractors with real fleets and the qualifications to win major work. That sounds comforting until you remember how the work is awarded. Competitive bidding means rivalry shows up as price pressure, especially on more commodity-like maintenance projects.

The dynamic shifts in boom periods. When everyone’s fleets are busy and backlogs are full, capacity becomes the constraint, and pricing tends to firm up. And on the most complex projects, rivalry isn’t just about who’s cheapest. Safety record, execution credibility, and having the right specialized vessel for the job can be the difference between winning a marquee contract and watching it go to someone else.

Overall Assessment: This is a moderately attractive industry. The barriers to entry are very real, and the lack of substitutes makes demand durable. But the biggest buyer is a disciplined, price-sensitive customer, and competition can get intense—especially when federal funding or project mix swings the market from “too much work” to “not enough.”

XIII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework Analysis

Scale Economies: MODERATE

In dredging, scale mostly shows up as fleet flexibility. With a larger fleet, GLDD can keep equipment working by shifting vessels between regions and project types as demand moves around. That improves utilization and lets the company spread fixed costs—management, maintenance infrastructure, compliance, and bidding—across more revenue.

But dredging isn’t software. You still have to physically get the vessel to the job, and that travel takes time and money. After a certain point, more scale helps less, because the work is inherently geographic and project-based.

Network Effects: NONE

There aren’t network effects in dredging. A port authority doesn’t get more value from GLDD because other ports also hired GLDD. Each project stands on its own.

Counter-Positioning: NONE

There isn’t a disruptive business model here that incumbents can’t copy. The core service is still the same: move sediment from where it shouldn’t be to where it’s needed. Technology improves the tools, but it doesn’t change the fundamental job in a way that gives a newcomer a structurally different playbook.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

Once a project is underway, switching contractors is close to impossible. You can’t casually hand off a channel-deepening job midstream without major cost, risk, and delay.

But between projects, buyers rebid regularly. Switching costs drop dramatically when the contract ends. What creates stickiness isn’t lock-in—it’s reputation, past performance, and the comfort that a contractor can execute without turning a fixed-price job into a crisis.

Branding: WEAK-MODERATE

This is a B2B and government-contracting business. Capability beats brand every time. Still, in dredging, reputation is a form of currency. In its more than 132-year history, the company has never failed to complete a marine project. That matters when the Army Corps is deciding who should be trusted with a multi-hundred-million-dollar job.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

GLDD’s most important cornered resource is its modern, Jones Act-compliant fleet. You can’t replicate that quickly. Designing and building major dredging vessels takes years, and under the Jones Act it has to happen in U.S. shipyards.

As CEO Lasse Petterson put it: “The delivery of our sixth hopper dredge, the Amelia Island marks a significant milestone as our dredging newbuild program is now complete, leaving us with the largest and most advanced hopper fleet in the United States.”

Layer on top the crews and the operational know-how to run these vessels efficiently, safely, and on schedule. That’s real advantage—but it isn’t permanent. If competitors invest over time, the gap can narrow.

Process Power: MODERATE

Decades in the field have taught GLDD how to bid, plan, and execute in a world where weather, ground conditions, and logistics can blow up the best spreadsheet. Those accumulated lessons—especially around project management, risk controls, and estimating—are meaningful process advantages.

The company’s Incident-and Injury-Free (IIF) safety management program is integrated into all aspects of its culture. Safety and environmental compliance systems are also hard to stand up quickly. But none of this is magic. With enough time and capital, a determined competitor can study these practices and build something similar.

Primary Power: Cornered Resource (fleet + expertise). Secondary: Scale Economies and Process Power.

Overall Assessment: GLDD has a “good enough” moat in a niche, capital-intensive industry, but it doesn’t have a single dominant power source. The Jones Act creates an external regulatory wall, and within that wall GLDD’s fleet and operating capabilities give it a defensible position. Still, by classic standards, this isn’t a wide-moat business—it’s a survival-and-execution business.

XIV. The Bull Case

The bull case for GLDD is what you’d hope for in a heavy-industrial company: the world is leaning into its services, the company is executing better than it has in years, and the barriers to entry are still very real.

Infrastructure Spending Tailwind

Start with the simplest driver: the U.S. is spending again.

The IIJA and related legislation amount to the largest push for American infrastructure in generations, including roughly $17 billion for the Army Corps of Engineers to address infrastructure priorities and support coastal resiliency and flood mitigation. That money can translate into exactly the kinds of projects GLDD lives on: dredging, restoring jetty structures, and major navigation work like the construction of a new lock at the Soo Locks.

And the funding environment has continued to look supportive. The 2025 Corps budget was expected to be another record appropriation. On June 28, 2024, the U.S. House of Representatives Energy and Water Appropriations Subcommittee passed its 2025 Appropriations Bill providing the Corps with a budget of $9.96 billion, which is $2.7 billion above the President’s budget request. The bill included $5.7 billion for Operations and Maintenance projects, with $3.1 billion coming from the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund.

In a business where federal awards set the tempo, that kind of backdrop matters.

Climate Adaptation

Then there’s the demand driver that doesn’t care about politics: the coastline is changing.

Rising sea levels and increasing storm intensity are pushing more communities toward coastal protection as a necessity, not a luxury. That expands the addressable market in a way that isn’t just cyclical—it’s structural. The harsher the storms and the faster the erosion, the more often beaches need to be rebuilt and dunes need to be restored.

Offshore Wind

GLDD’s third leg of the stool is offshore wind, and the bull case here is about timing and scarcity.

The company has stayed committed to entering the U.S. offshore wind market, with Acadia—its U.S.-flagged, Jones Act-compliant subsea rock installation vessel—anticipated to be delivered in the latter half of 2025. If that happens on schedule, Great Lakes becomes first with Jones Act-compliant rock installation capability, in a market that could take years to develop a real domestic vessel supply chain. In a multi-decade buildout, “first with the right ship” can be a meaningful advantage.

Operational Improvements

Execution is the other half of the bull case, and it’s where this stops being just a “good industry” story.

In 2024, gross margin increased to 21.1% from 13.2% in 2023, driven in part by improved project performance and a mix shift toward capital and coastal protection work, which typically carry higher margins. The modern fleet is more productive, and better execution means fewer projects where small problems snowball into margin wipeouts.

Jones Act Protection

All of this sits on top of the same structural reality that has defined U.S. dredging for decades: the Jones Act.

The regulatory moat remains intact—and, if anything, looks more durable as national security concerns about foreign involvement in American infrastructure have intensified. The Jones Act is designed to maintain domestic capability in shipbuilding and waterborne transportation, and the U.S. Navy has been explicit about what it wants: repeal would “hamper [America’s] ability to meet strategic sealift requirements and maintain and modernize our naval forces.”

For GLDD, that doesn’t guarantee easy profits. But it does mean the competitive field stays limited.

Valuation

Finally, there’s valuation. Even after strong recent performance, GLDD trades at modest multiples relative to many infrastructure peers. The bullish argument is that the market is still pricing the company like a cyclical contractor, not like a scarce, fleet-based operator with durable demand drivers and a protected domestic market.

XV. The Bear Case

The bear case for Great Lakes is straightforward: this is still heavy construction, sold through competitive bidding, funded heavily by government, and executed in an environment you can’t control. The recent run of strong results and record backlog doesn’t erase the ways this business can go wrong.

Federal Budget Cyclicality

In 2024, roughly 57% of dredging revenue came from federal agencies. That’s great when Washington is spending. It’s painful when priorities shift, budgets tighten, or projects get delayed by shutdowns and politics. The obvious question is the one investors always ask at the end of a spending upcycle: when the current infrastructure cycle cools off, does demand fall with it?

Execution Risk

Dredging is a world of big, complex, fixed-price contracts. Weather delays. Unexpected soil conditions. Equipment failures. Permitting complications. Any of those can turn a “good” project into a margin crater.

Even a strong backlog isn’t a guarantee. At year-end 2024, dredging backlog stood at $1.2 billion, and 53% of that was tied to federal contracts—contracts that can be canceled without penalty. And on the growth side, the offshore energy push brings its own execution risk: the Acadia SRI vessel delivery was expected in the first half of 2026, pushed back from prior timelines, which is exactly the kind of delay that can snowball into cost overruns on a specialized newbuild.

Capital Intensity

Great Lakes is never done spending. Even when the current newbuild cycle ends, maintenance CapEx continues, drydocks continue, and eventually the replacement cycle starts again. That capital appetite can suppress free cash flow and keep returns on invested capital from looking as good as the company’s strategic position might suggest. Historically, those returns have often been mediocre.

Competition

The Jones Act protects the domestic market—but it’s also a perennial political target. Foreign competitors and their allies keep lobbying to weaken it. At the same time, the domestic field is small but formidable. Weeks Marine and other U.S. players can bid aggressively and execute.

And offshore wind has its own competitive twist: today, Great Lakes is partnering with European leaders. Over time, those partners—or their peers—could push further into the American market as the industry matures.

Margin Pressure

Even when revenue is strong, profitability can get squeezed. In the second quarter of 2025, gross margin rose to 18.9% from 17.5% a year earlier, driven by improved utilization and project performance—but partially offset by higher drydocking costs. That’s the reminder: inflation in labor, fuel, and materials doesn’t stop just because backlog is up. And fixed-price contracts make it hard to pass those increases through cleanly.

Climate Paradox

Climate change is a demand tailwind for coastal protection. But it also carries a long-term, uncomfortable tail risk: if storms and sea-level rise make certain shorelines too expensive to defend, some communities may eventually choose managed retreat over endless renourishment. That’s not tomorrow’s problem—but it’s a real scenario that could cap the long-run economics of beach work in the most vulnerable places.

Offshore Wind Uncertainty

Offshore wind is the newest leg of the stool—and the least proven in the U.S. market. States like Massachusetts have leaned on offshore wind as a core tool for decarbonization, but projects have faced repeated delays and major cost increases. Add in political hostility toward the industry at the federal level, and the risk becomes clear: this is a bet on a market that has struggled mightily to translate ambition into consistent execution.

XVI. Current State & What to Watch

Key Metrics to Track

If you’re trying to understand where GLDD goes from here, two things tell you more than any glossy slide deck ever will.

First, backlog levels and composition. As of June 30, 2025, the company had $1.0 billion in dredging backlog, down from $1.2 billion at December 31, 2024. That June figure also didn’t include about $215.4 million of awards and options that were pending. And the mix matters as much as the headline number: capital and coastal protection work generally carries more margin potential than routine maintenance work.

Second, fleet utilization rates. This is the heartbeat of the business. A dredge sitting idle doesn’t just “wait” for the next job—it burns cash. A fully scheduled fleet, moving from project to project, is how a capital-intensive contractor turns expensive steel into earnings.

Catalysts to Monitor

The project pipeline starts with Washington. Army Corps budget appropriations drive what gets funded, when it gets bid, and how crowded the market feels.

Then there’s state and local money, especially for beach nourishment—particularly in Florida, New Jersey, and North Carolina—where shoreline protection is both economic policy and survival strategy.

Offshore wind is the swing factor. Lease auctions, developer timelines, and permitting cadence will determine whether the Acadia investment hits at exactly the right moment—or arrives into a slower market.

And finally, the quiet one: Jones Act legislative activity. Most of the time it’s background noise. If it ever became real policy change, it would be anything but.

Recent Performance

So far, the execution has matched the setup.

The company delivered a strong first half of 2025 and expected momentum to continue through the rest of the year and into 2026, supported by its modernized fleet, improved project performance, and a still-robust backlog.

In Q1 2025, Great Lakes reported revenue of $242.9 million and net income of $33.4 million. Dredging backlog was $1.0 billion, plus another $265.3 million in pending awards.

And then came a signal that would’ve been hard to imagine during the turnaround years: returning capital. In the first quarter of 2025, the company authorized a $50 million share repurchase program, saying its share price didn’t reflect financial performance and long-term outlook. By June 30, 2025, it had repurchased 1.3 million shares for $11.6 million.

After a decade defined by reinvestment and fleet spending, buybacks marked a shift in posture: management was no longer just rebuilding the business. It was starting to harvest it.

XVII. Epilogue & Lessons

Great Lakes Dredge & Dock is, on the surface, an unlikely comeback story: a company that does one of the least glamorous jobs in the economy, operating in a niche most people never think about, surviving long enough to become more important as the world changes.

But that’s exactly why it’s worth studying.

The Turnaround Narrative

In 2009, Great Lakes was staring at the edge of the cliff. By 2024, it was posting the second-best results in its history. The stock recovered from under a dollar to around ten dollars, with the big move coming as the company fixed its execution, modernized the fleet, and the demand wave it had bet on actually arrived.

The lesson isn’t “turnarounds are easy.” It’s the opposite: in capital-intensive industries, survival often requires committing to expensive, irreversible decisions at the exact moment you feel least able to afford them. Sometimes you really do have to bet the company to keep the company.

Boring Can Be Beautiful

There are no viral moments in dredging. No product launches. No cult founders. Just steel, crews, tides, and the constant reality that sediment keeps moving whether Congress votes on it or not.

And yet the work sits right where the big, slow, unavoidable forces of the next few decades converge: global trade that keeps pushing ports to handle bigger ships, coastlines that keep eroding and getting rebuilt, and an energy transition that needs marine construction to move from policy to power on the grid. You don’t have to love the industry to recognize the durability of the demand.

The Moat Question

GLDD isn’t a classic “wide moat” business. It doesn’t have network effects. Switching costs are real mid-project, but customers rebid relentlessly between projects. And this isn’t a world where branding lets you charge a premium.

What Great Lakes does have is a different kind of defensibility: the Jones Act as a hard boundary around the domestic market, plus a modern, scarce fleet and the operational competence to execute high-stakes work without blowing up fixed-price contracts. In an oligopoly built on expensive assets, survival and competence can be the advantage.

Regulatory Moats: Double-Edged Swords

The Jones Act is both Great Lakes’ shield and its tax. It keeps foreign dredging giants out of domestic work—but it also forces newbuilds into U.S. shipyards, at U.S. costs, which dramatically raises the price of staying competitive.

That’s the trap with regulatory protection: it can enable complacency. If you’re protected long enough, you can forget what it feels like to compete on capability and cost. Great Lakes nearly learned that lesson the hard way in the 2000s. The turnaround was, in part, a decision not to rely on regulation alone.

Infrastructure as an Investment Theme

Finally, there’s the bigger takeaway: infrastructure is slow, political, and usually invisible—until it fails. But the companies that maintain the physical systems underneath modern life often operate with real barriers to entry, durable end demand, and long-cycle assets that are hard to replicate.

GLDD is both the appeal and the warning label. You get essential services, real assets, and regulatory protection. You also get capital intensity, exposure to federal budgets, and execution risk that can erase a year’s profit in a single bad job.

William Lydon and Fred Drews started this company in Chicago in 1890 to build water tunnels. Today, Great Lakes operates the largest dredging fleet in the United States, has survived wars, financial crises, and reinvention, and is positioning itself for the next wave of American investment in ports, coastlines, and offshore energy.

It’s 135 years of moving mud—one cubic yard at a time.

XVIII. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Long-Form Links & Books

-

GLDD 10-K and Investor Presentations (SEC filings) - The primary source for how the company describes its segments, risks, fleet, and backlog. Available at investor.gldd.com.

-

"The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger" by Marc Levinson - The best narrative primer on containerization, and why ports, channels, and shipping infrastructure became the hidden plumbing of globalization.

-

"Dredging: A Handbook for Engineers" by R.N. Bray - A technical, nuts-and-bolts look at dredging methods, equipment, and the realities of moving material underwater.

-

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Annual Reports - A direct window into the priorities, funding, and project categories that shape much of the U.S. dredging market.

-

"The New Map: Energy, Climate, and the Clash of Nations" by Daniel Yergin - A wide-angle view of the energy transition and geopolitics—useful context for why offshore wind became strategically important, and why it’s been messy.

-

WEDA (Western Dredging Association) Reports - Industry perspective from the U.S. trade group: safety, policy, market trends, and the issues that keep showing up in dredging.

-

Journal of Waterway, Port, Coastal, and Ocean Engineering - Deep academic research on ports, coastal protection, sediment movement, and engineering approaches that show up later as “real-world” projects.

-

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Coastal Reports - The climate-and-coastline backdrop: erosion, storm patterns, and the trends that keep beach nourishment in the conversation.

-

Infrastructure investor letters (Brookfield, EQT, etc.) - How large, long-horizon capital thinks about infrastructure: cyclicality, underwriting, and what “durable demand” actually means in practice.

-

"Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Company: A Century of Experience, 1890–1990" by Paul R. Dickinson - The company’s own historical record for the founding era, early projects, and how Great Lakes became a national player.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music