Griffon Corporation: The Story of a Multi-Billion Dollar Conglomerate Built Through Strategic Rollups

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

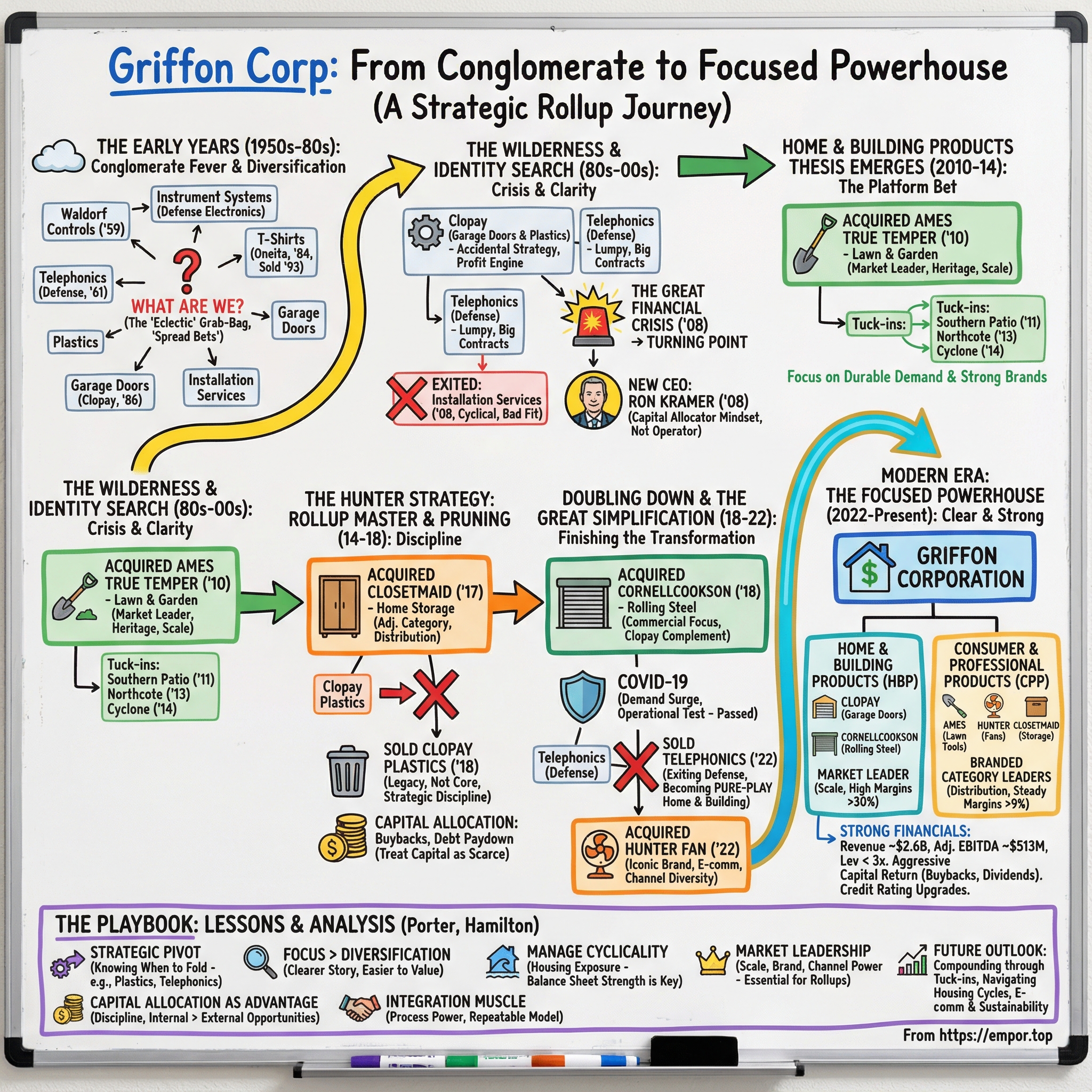

Picture this: a company born in the golden age of movie theaters, that later bet big on defense electronics, took detours into installation services, and somehow—seven decades on—ended up as one of America’s most powerful players in garage doors and lawn tools. That’s Griffon Corporation: a multi-billion-dollar business hiding in plain sight, trading quietly on the NYSE while most investors couldn’t tell you what it does.

And what it does today is surprisingly straightforward. Through its subsidiaries, Griffon sells home and building products, plus consumer and professional products, across the United States, Europe, Canada, Australia, and beyond. In the fiscal year ending September 30, 2024, Griffon generated $2.62 billion in revenue. With a market capitalization around $3.5 billion, it’s not a tiny company. It’s just one that has managed to compound—often quietly—without becoming a household name on Wall Street.

The story starts in 1959 with Helmuth W. Waldorf, a Long Island businessman and tool-and-die maker’s apprentice who immigrated from Germany to study at Columbia University. He founded a small defense electronics company in College Point, Queens, called Waldorf Controls Corporation. That name didn’t last long. Later that year it became Instrument Systems Corporation. Then, in 1961, the company went public and strengthened its avionics business by acquiring Telephonics Corporation.

From there, Griffon became what you might politely call “eclectic.” Over the decades it owned defense electronics, T-shirt manufacturing, plastics, garage doors, installation services, and more. The portfolio read like a 1970s boardroom manifesto: do a little bit of everything, and diversification will protect you.

This is the story of how that approach eventually broke—and what Griffon built in its place.

Three core themes define Griffon’s transformation from muddled conglomerate to focused powerhouse. First: the art of the rollup—how to consolidate fragmented industries through disciplined acquisition. Second: capital allocation mastery—knowing when to buy, when to hold, and, most importantly, when to sell. Third: strategic portfolio pivots—the rare corporate courage to shed businesses that defined you for decades in order to become something entirely new.

What follows is how Griffon went from a company that struggled to explain itself to Wall Street to becoming North America’s largest garage door manufacturer and a dominant force in lawn and garden tools. It’s a story about crisis creating clarity, patient capital deployment, and the hard-earned advantage that comes from finally choosing what you are—and what you’re not.

II. The Early Years: Theaters, Diversification & Conglomerate Fever (1950s–1980s)

The 1950s and 1960s were a strange, heady moment in American business. The fashionable idea of the day was simple: don’t pick one lane—own a bunch of them. If one industry hit a downturn, another might be booming. Spread the bets, smooth the earnings, and Wall Street would reward you for being “safer.”

That was the conglomerate thesis. And it was the water Griffon grew up swimming in.

Griffon began life in 1959 as Waldorf Controls Corp., then quickly rebranded as Instrument Systems Corp. before the year was out. Based in College Point, Queens, it built electronic and electromechanical products for military and government customers. It also had a powerful early backer: Emerson Radio & Phonograph Corp. owned roughly a quarter of the business.

The timing couldn’t have been better. Defense spending was surging in the Cold War era, and Washington was eager to fund anyone who could help push American technology forward. Helmuth Waldorf, a German immigrant with a tool-and-die background and a sharp feel for opportunity, positioned the company right in the middle of that spending stream.

In 1964, leadership changed—and the pace picked up. Edward J. Garrett became chairman and president, and two younger brothers moved into senior executive roles. The Garretts cut losses by shutting down deficit-ridden plants, pushed the company to find more civilian markets, and leaned hard into government research-and-development contracts that could fund the next wave of products.

The result was a rapid transformation. In just a few years, Instrument Systems went from a small Long Island-area electronics business to something that looked, at least on paper, like a bona fide industrial conglomerate. By 1968, it was trading on the American Stock Exchange, which meant something crucial: access to more capital, and with it, more acquisitions.

Telephonics was the early cornerstone. Instrument Systems bought Telephonics Corp. in 1961, adding real heft in defense electronics. Over the years, the company kept moving pieces around the board. A sound system for airliners went into production in 1969. In 1976, it sold off plastics and packaging. Buy a division, work it for a while, sell it, repeat—the corporate churn that defined the conglomerate era started to become part of Instrument Systems’ rhythm.

But the market rarely loves a grab-bag. Most conglomerates ran into the same problem: the conglomerate discount. Investors and analysts didn’t know how to value a business that was part defense contractor, part manufacturer, part whatever-else-it-owned-this-year. If you covered defense electronics, you didn’t want to handicap consumer or industrial operations. If you wanted steady consumer exposure, you didn’t want the volatility of government procurement cycles. Complexity became a tax, and the stock often traded for less than the parts were worth on their own.

Meanwhile, Telephonics kept getting stronger. In 1981, it landed a five-year order worth about $100 million to supply the central integrated test system for Rockwell International’s B-1B bomber. It was also developing communications and radio control systems for the Navy’s anti-submarine S-3A aircraft and LAMPS MK III helicopters, plus an advanced audio communications system for NASA’s Space Shuttle Orbiter Vehicle. In other words: serious programs, serious customers, serious credibility.

By the early 1980s, Instrument Systems had become a real defense electronics player—just not a focused company. Telephonics gave it legitimacy and high-value contracts, but the broader portfolio still felt like a collection of decisions rather than a strategy. The market treated it accordingly.

And yet, underneath all that mess, something important was happening. Without realizing it—or at least without fully committing to it—Griffon was inching toward the kind of acquisition that would eventually define what it became. It just wouldn’t be obvious for a long time.

III. The Wilderness Years: Searching for Identity (1980s–2000s)

The 1980s brought the one acquisition that, in hindsight, mattered more than almost anything else Griffon did for the next four decades: Clopay Corporation. In 1986, Instrument Systems bought Clopay for $37 million, and it turned out to be the company’s most successful diversification move—even if it didn’t look like a grand strategy at the time.

Clopay itself was a reinvention machine. It started in 1859 as a paper wholesaler in Cincinnati. During World War II, it shifted into window coverings. It later took the name Clopay—a mash-up of “cloth” and “paper.” Then it kept evolving: plastic film in 1952, and garage doors in 1966.

That adaptability ended up being the real asset. Clopay grew through the 1990s and 2000s into a leading U.S. manufacturer of residential garage doors and a supplier of plastic films used in products like diapers, surgical gowns, and drapes. By 1991, Clopay was responsible for about 70% of Instrument Systems’ roughly $50 million in operating income. The message was loud, even if the company didn’t fully absorb it: this “diversification” wasn’t a side bet. It was the center of gravity.

By the early 1990s, Griffon’s internal dynamic was set. Clopay threw off steady cash. Telephonics delivered big defense wins—but on a schedule dictated by government budgets and contract timing. One business was consistent and quietly compounding. The other was prestigious, technically complex, and inherently lumpy. That push and pull—boring and reliable versus exciting and volatile—would shape years of boardroom debate.

And then there was everything else.

In 1984, Instrument Systems bought Oneita Knitting Mills, Inc. for about $15 million. Oneita was a New York apparel company founded in 1893, making T-shirts and clothing for newborns. It was renamed Oneita Industries. Within a few years, Instrument Systems started selling off pieces of it, and by 1993 the entire business was gone.

Oneita was a clean example of the conglomerate era’s core failure mode: buying things because you can, not because they fit. T-shirts had no strategic connection to defense electronics, plastic films, or garage doors. It was diversification as a hobby—and the market treated it like one.

By the mid-1990s, the company tried to clean up the story. Under leadership that had turned Instrument Systems into a leaner holding company with three core areas—plastics, garage doors, and electronics—there was real progress operationally. But Wall Street still didn’t care. “We’re very frustrated that we haven’t gotten our story across,” Blau said at the time. In 1994, he moved the stock from the American Stock Exchange to the New York Stock Exchange to raise the company’s profile. And the business adopted a new name: Griffon Corporation, after the mythical half-lion, half-eagle—strength through diversity.

It was a strong symbol. It just didn’t solve the underlying problem. Griffon still had to explain why defense electronics, plastic films, and garage doors belonged under one roof. The legal name change from Instrument Systems to Griffon followed in 1995. The company was growing and profitable, and the stock had risen to about $9 a share from roughly $1 a share in 1989—but “what are you?” remained an unanswered question.

Inside the portfolio, the pieces kept moving. Clopay was now the largest business by far. Telephonics worked to reduce its dependence on purely military projects by pursuing commercial and nondefense government work, but it still lived in the world of big programs and big contracts. It held major communications equipment work tied to JSTARS, the U.S. military aircraft platform. In 1997, it won a contract worth more than $100 million to supply communications equipment for upgrades to the British Royal Air Force’s Nimrod antisubmarine planes. That same year, it also won a $26 million deal to supply wireless communications equipment for 1,080 New York City subway cars—proof it could translate defense-grade expertise into civilian infrastructure.

From the mid-1990s through the mid-2000s, the top line kept climbing. Griffon crossed $1 billion in sales in 1999 and reached $1.5 billion by 2006. If you stopped there, the story looked fine: growth, profitability, diversification.

But the cracks were already there. Griffon’s residential installation services business—an attempt to vertically integrate by owning the installers of Clopay garage doors—turned out to be capital-intensive and deeply cyclical. Margins were pressured, and the business demanded constant reinvestment just to stand still. Meanwhile, Telephonics still rose and fell with procurement cycles and the quirks of contract timing.

So Griffon walked into 2008 bigger than ever, and still strategically unresolved. Was it a defense contractor? A building products company? A diversified industrial holding company? The honest answer was: it depended on the day you asked. And when the world is about to lurch into a financial crisis, that lack of clarity isn’t just a branding problem. It’s a vulnerability.

IV. The Great Financial Crisis & The Turning Point (2008–2010)

The financial crisis didn’t just put pressure on Griffon’s balance sheet. It exposed the core weakness of the whole conglomerate idea Griffon had lived with for decades: when your businesses don’t reinforce each other, a shock doesn’t get diversified away. It hits everywhere at once.

Right as the world was sliding toward the cliff, Griffon changed hands at the top. In 2008, Harvey Blau stepped down as CEO. On April 1, 2008, Ron Kramer—Blau’s son-in-law—took over. Blau stayed on as non-executive chairman. Kramer wasn’t a longtime operator coming up through manufacturing plants; he was an investment banker. He’d married Blau’s daughter, Stephanie, in 1992, joined Griffon’s board in 1993, and became vice chairman in 2003. Now he was in the CEO seat, and the timing was brutal.

Within months, Lehman collapsed and the credit markets seized up. Housing cratered—exactly the kind of macro shock that tests anything tied to home construction. Clopay’s end markets weakened. Telephonics faced its own uncertainty as government spending and procurement priorities shifted. And the residential installation services business, already a problem, ran straight into a wall as new construction activity dried up.

Kramer’s response was less about grand strategy and more about staying alive. He shored up liquidity by securing a new $100 million revolving line of credit from JPMorgan Chase. He refinanced Griffon’s senior debt. He raised about $250 million through a stock offering and investments from Goldman Sachs, Kramer himself, and existing Griffon shareholders. And most importantly, he made a painful call: Griffon exited the residential installation services business—one that had seen net sales fall 65% over three years.

That 65% decline wasn’t a bad quarter. It was the business model breaking in real time.

On paper, installation services had sounded smart. Own more of the value chain. Control the customer experience. Capture more margin. In the real world, it chained Griffon to one of the most violent cycles in the economy: housing starts. When housing collapsed, there wasn’t a “diversification benefit.” There was just a bigger hole.

In 2009, Griffon added another piece that mattered more than it looked at the time: Brian Harris, hired from Dover Corporation as chief accounting officer. He would later become vice president and controller in 2012, and then senior vice president and CFO in 2015. Dover was known for operational discipline and capital allocation rigor. Bringing in someone from that environment was a signal that Griffon was building muscle for something beyond mere survival.

Because crisis has a way of forcing honesty. When you’re fighting for oxygen, the portfolio questions stop being theoretical. Which businesses generate cash? Which consume it? Where do you actually have defensible positions—and where are you just participating?

For Griffon, the answers started to crystallize. Even in a housing collapse, Clopay still had something real: brand, distribution, and a replacement-driven element of demand. Telephonics was different—lumpy and contract-driven, yes, but tied to a cycle that wasn’t housing. And installation services? The crisis made the verdict obvious.

Exiting that segment became Kramer's first major act of portfolio rationalization. It set a new rule for what deserved to stay: a business had to earn its place through cash generation, market position, and fit—not just because it had been there for years.

By 2010, Griffon had made it through with its balance sheet intact, its key operating businesses still standing, and a new leadership team finding its footing. Survival was no longer the only objective.

Now the real question was: if you’re not going to be everything, what are you going to be?

V. The Home & Building Products Thesis Emerges (2010–2014)

Just two years after flirting with disaster, Griffon made a bet that would reshape the company for good.

In September 2010, Griffon announced it would acquire Ames True Temper, the leading North American manufacturer and marketer of non-powered lawn and garden tools, wheelbarrows, and outdoor work products. The total price: $542 million.

On the surface, the timing looked aggressive. Housing was still weak. Consumers were cautious. Deal-making hadn’t exactly roared back to life. But Ron Kramer saw what he wanted Griffon to become: a focused owner of category leaders with durable demand and strong brands. As he put it at the time, Ames True Temper was “the clear market leader” with “superb brands, quality products, excellent customer relationships, and an outstanding management team,” plus obvious room to grow in North America and globally.

AMES came with something else that was hard to manufacture from scratch: heritage. The business traces its roots to 1774, when Captain John Ames opened a blacksmith shop making shovels. That’s not just a fun founding story—it’s a signal of endurance. The company had lived through every cycle America could throw at it and still held the number one or number two position across major product categories.

This wasn’t a distressed “buy it cheap and hope” move. Castle Harlan, the private equity firm selling Ames, had owned it since 2004 and built out a strong management team. Its president, Justin Wender, described the handoff as passing a well-run business to its next chapter: the company was “poised to continue its solid growth,” and Castle Harlan was proud to have been part of its long history.

Griffon also made the financial case plainly. On a pro-forma basis for the twelve months ended June 30, 2010, combining Griffon and Ames would have brought revenue to roughly $1.7 billion versus about $1.27 billion for Griffon on its own. Management said pro-forma EPS would rise by around 60%. The point wasn’t the spreadsheet—it was the signal: Griffon wasn’t just buying a company. It was buying momentum, scale, and a second pillar next to Clopay.

To understand why this deal mattered, it helps to understand Kramer.

He wasn’t a lifelong manufacturing operator. Kramer earned his undergraduate degree from Wharton in 1980 and an MBA from NYU in 1981, then built his career in finance—starting at Citibank, then spending thirteen years at Ladenburg Thalmann, eventually becoming chairman and CEO in 1995. In 1999, he became a managing director and partner at Wasserstein Perella and its successor firm, Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein. He left Wall Street in 2002 to become president and director at Wynn Resorts.

That background showed up in how Griffon started behaving. Under Kramer, the company strengthened its balance sheet, consolidated manufacturing, invested more than $50 million to modernize operations, and exited the underperforming installation services business. The mindset was unmistakable: treat capital like a scarce resource, demand returns, and keep the balance sheet flexible enough to act when opportunities appear.

After Ames, Griffon started building out the platform with a deliberate series of tuck-ins. In 2011, it bought the Southern Patio pots and planters business from Southern Sales & Marketing Group for $23 million. In late 2013, it acquired Northcote Pottery—an Australian garden décor maker founded in 1897—for $22 million. A few months later, it bought Cyclone, the Australian garden and tools division of Illinois Tool Works, for $40 million.

The strategy was coming into focus: stick to adjacent categories, buy businesses with real positions in the market, then build scale through integration and operational improvement. This wasn’t the old Griffon—random diversification dressed up as safety. This was consolidation with a thesis.

Griffon also upgraded the leadership bench to match its ambition. In 2012, the company named Robert Mehmel president and COO. Mehmel came from DRS Technologies, a defense electronics manufacturer that grew from $400 million to over $4 billion in sales during his tenure.

It rounded out the team Griffon needed for what came next: Kramer as the dealmaker and capital allocator, Mehmel as the operational executor, and Brian Harris providing financial control and discipline.

By 2014, Griffon’s identity had snapped into place. The company that once struggled to explain why its pieces belonged together now looked like a focused acquirer of market-leading home and building products businesses—patiently deploying capital to build scale in fragmented industries.

The wilderness years were over. The rollup machine was just getting warmed up.

VI. The Hunter Strategy: Becoming a Rollup Master (2014–2018)

From 2014 through 2018, Griffon stopped looking like a company experimenting with a new thesis and started looking like a company that had found its operating system. Ames and Clopay weren’t just two good businesses sitting side by side anymore. They were platforms. And Griffon’s job became simple to describe, even if it was hard to execute: keep buying smart, keep integrating well, and keep pruning anything that didn’t fit the increasingly clear home-and-building-products identity.

The acquisitions came in a steady drumbeat, and they mostly followed the same pattern: adjacent categories, strong brands, and distribution Griffon could amplify.

In April 2017, The AMES Companies expanded into the UK by acquiring three businesses at once: La Hacienda, a heating and garden décor brand; Kelkay, a decorative outdoor landscaping player; and Apta, a garden pottery business. The point wasn’t just “international growth” in the abstract. These deals gave AMES access to leading garden centres, retailers, and grocers across the UK and Ireland—and a real platform to build from.

Australia got the same treatment. Early in 2017, Griffon announced the acquisition of Hills Home Living, the iconic clothesline and home-products brand. Then, in September 2017, it added Tuscan Path, a provider of pots, planters, pavers, decorative stone, and garden décor products. Back in the U.S., Griffon broadened AMES beyond long-handle yard tools into cleaning. In October 2017, it acquired Harper Brush Works from Horizon Global, adding brooms, brushes, and other cleaning products to the mix.

None of these were splashy headline deals. That was the point. This is what a rollup looks like in real life: a sequence of practical moves that make the platform wider, strengthen channel relationships, and create more leverage in manufacturing and overhead.

Then came the bigger swing.

In 2017, Griffon completed the acquisition of ClosetMaid from Emerson for $260 million. After factoring in tax benefits from the transaction, Griffon described the effective purchase price as $225 million.

ClosetMaid, founded in 1965, was a market leader in home storage and organization—closet systems, home storage, and garage storage products—sold through major home center retailers, mass merchandisers, and direct-to-builder professional installers. In other words, it fit perfectly with where Griffon was already winning: branded, physical products with entrenched retail and channel relationships.

Ron Kramer framed the logic plainly: “ClosetMaid complements and diversifies our portfolio of leading consumer brands and products. This acquisition expands our existing footprint in home centers and expands our customer relationships to include the direct to builder and mass merchant, specialty and hardware channels.”

Griffon characterized the valuation as roughly 7.1 to 7.5 times expected EBITDA—reasonable pricing for a category leader with distribution already stitched into the biggest channels. And in its first full year under Griffon, management expected ClosetMaid to contribute about $300 million in revenue.

But the ClosetMaid announcement carried a second message—arguably the more important one.

Alongside the deal, Griffon disclosed that it had received unsolicited inquiries from qualified parties about buying Clopay Plastic Products, and that it would explore strategic alternatives for the business.

This was a big moment of self-awareness. Clopay Plastics was legacy in the truest sense: plastic film had been part of Clopay since 1952. It was also a real business. For the trailing twelve months ending June 30, 2017, Clopay Plastics generated $468 million in revenue and $53 million of segment adjusted EBITDA.

Kramer went out of his way to praise it while also making clear it might not belong: “Clopay Plastics is a well-recognized, trusted provider of specialty plastic films. It has an 83-year legacy of innovation and technical leadership, a state-of-the-art manufacturing base with global reach, outstanding personnel, and long-term relationships with blue-chip customers. Given the unique aspects of the Clopay Plastics business, Griffon is evaluating approaches to increase long-term value for our shareholders while providing enhanced opportunities for growth and value creation for Clopay Plastics and its customers.”

A few months later, Griffon made the decision real. In November 2017, it announced the sale of Clopay Plastics to Berry Global for $475 million. The transaction closed in February 2018, and with it Griffon exited the specialty plastics industry it had entered through the Clopay acquisition back in 1986.

This wasn’t just portfolio cleanup. It was strategy hardening into doctrine: Griffon was increasingly willing to sell good businesses—businesses with history—if they weren’t aligned with where the company was going.

And it wasn’t only about buying and selling. It was also about what you do with the cash. Between August 2011 and March 2018, Griffon repurchased 21.9 million shares for a total of $290 million. The through-line was consistent: acquire with intention, divest to sharpen focus, and return capital when the stock offered value.

In 2018, Kramer was appointed chairman of the board, succeeding Harvey Blau after Blau’s death in January. Blau’s passing marked the end of an era—the leader who had overseen Griffon’s evolution through the old conglomerate world was gone. But the successor wasn’t improvising. Kramer was firmly in control, and the company’s direction was no longer ambiguous.

By 2018, Griffon had pulled off something most conglomerates talk about and few execute well: it simplified without shrinking itself into irrelevance. The portfolio was cleaner, the acquisition machine was running smoothly, and the company looked ready for its next, even bigger bet.

VII. The CornellCookson Bet & Doubling Down (2018–2020)

In 2018, Griffon made what might have been its cleanest strategic move yet. Not the biggest. Not the flashiest. Just the kind of deal that tells you a company finally understands its own playbook.

Clopay Building Products entered into a definitive agreement to acquire CornellCookson, a leading U.S. manufacturer of rolling steel doors and grille products used in commercial, industrial, institutional, and retail settings. The purchase price was $180 million, or about $170 million net of tax benefits.

CornellCookson was old-school American manufacturing in the best sense. Founded in 1828, it operated out of Mountain Top, Pennsylvania and Goodyear, Arizona, building custom closure solutions you’d find in places where failure isn’t an option—stadiums, hospitals, hotels, museums, and other facilities where reliability, security, and life safety matter. And it didn’t sell through big-box retail. CornellCookson went to market through a global network of more than 700 dealer partners.

The fit with Clopay was immediate. Ron Kramer called it “a highly strategic addition” to Griffon’s Home and Building Products segment—complementing Clopay’s residential and commercial sectional doors with a leading position in rolling steel products. The acquisition expanded Griffon’s footprint in the commercial channel, deepened relationships with professional dealers and installers, and added another legacy brand to the stable. With a history of innovation and quality dating back to 1828, Kramer said, the Cornell and Cookson names would be “right at home” inside Griffon.

The logic went beyond brand poetry. CornellCookson sat right next to Clopay’s core competency—doors—while pulling Griffon further into commercial and industrial environments, with a different customer base than residential garage doors. And because the products were specialized, the margin profile was more attractive. This was rollup thinking with discipline: broaden the market, stay close to what you know, and let your existing manufacturing and distribution muscle do the heavy lifting.

That muscle was real. Clopay Building Products, founded in 1964, was already a leading manufacturer and marketer of residential and commercial garage doors, selling through professional dealers and some of the largest home center chains in North America. It operated a national network of more than 50 distribution centers, sold to roughly 2,000 independent professional installing dealers, and served self-install customers through Home Depot and Menards.

After the deal, Griffon didn’t just “integrate” CornellCookson and move on. It invested. More than $25 million of capital went into Clopay and CornellCookson following the acquisition, including $15 million to expand and modernize CornellCookson’s Mountain Top, Pennsylvania facility. The goal was simple: cement leadership in door products and build capacity for growth.

And then the world changed.

COVID-19 didn’t arrive as a normal downturn. It arrived as a systems failure. Supply chains fractured. Steel and resin costs spiked. Shipping capacity tightened. For a company that manufactures bulky physical products and relies on distribution networks to move them, those weren’t abstract macro headlines—they were daily operational problems.

But the demand side did something almost no one predicted. Stuck at home, Americans started upgrading the places they lived. Home improvement spending surged. Garage doors suddenly mattered more when you were walking past them ten times a day. Lawn and garden tools flew off shelves as first-time homeowners—and plenty of people who weren’t homeowners—discovered that yard work is both productive and strangely calming.

For Griffon, the question stopped being “How do we get through this?” and became “How do we ship enough product?”

That’s where the company’s accumulated operating discipline showed up. Griffon managed liquidity carefully while still investing to meet demand. It took pricing actions to offset commodity inflation. And the integration muscle it had built over the previous decade—acquiring, rationalizing, improving—translated surprisingly well into crisis execution.

By the end of 2020, Griffon had come through the pandemic’s first phase in better shape than it went in. The home and building products thesis had been stress-tested under extreme conditions, and it held.

Now the next question was unavoidable: with the strategy working and the portfolio getting cleaner, was it finally time to finish the transformation—exit the legacy defense business and become a pure-play home and building products company?

VIII. The Great Simplification: Exiting Defense & Going Pure-Play (2021–2022)

For sixty-one years, Telephonics was part of Griffon’s corporate DNA. Since buying it in 1961, the defense electronics business had built radar, communications, and surveillance systems for some of the most advanced military platforms in the world. It had been there for the B-1B bomber program, the JSTARS work, even Space Shuttle-era programs.

But on June 27, 2022, that era ended. Griffon completed the sale of Telephonics Corporation to TTM Technologies, Inc. for $330 million in cash, subject to certain post-closing adjustments.

“We are pleased to announce the closing of the sale of Telephonics. This transaction unlocks immediate value for our shareholders and strengthens our balance sheet,” said Ronald J. Kramer, Griffon’s Chairman and Chief Executive Officer. “Telephonics has been a part of Griffon for more than sixty years.”

This was a defining moment—and not just because selling a legacy business is emotionally hard. It was also politically hard. The sale came just months after another major move that triggered a very public shareholder fight.

In January 2022, Griffon closed its largest acquisition ever: Hunter Fan Company, the leading U.S. brand of residential ceiling fans, for $845 million, subject to post-closing adjustments.

Hunter was an iconic name with a 135-year heritage and a reputation for innovation and quality. It also brought an enviable customer roster, including The Home Depot, Lowe’s, Menards, Costco, and Amazon.

“Over the last 135 years, Hunter has earned its reputation for innovation, quality and craftsmanship, and has strong strategic alignment with Griffon’s Consumer and Professional Products segment. Hunter complements our portfolio of leading consumer products, and diversifies our channels to market, particularly with Hunter’s success in growing its e-commerce and direct to customer business to almost half of overall sales while maintaining their leading position in the retail channel.”

Griffon said the deal would be immediately accretive to earnings and cash flow. In the first full fiscal year, management expected Hunter to add about $400 million in revenue and $90 million of EBITDA, excluding synergies, with earnings accretion of at least $0.50 per share. The purchase price implied a multiple of roughly 9.4 times EBITDA.

Not everyone was on board.

Voss Capital, a significant Griffon shareholder, publicly opposed the Hunter acquisition and nominated several candidates for election to the board at the company’s annual meeting. “In our opinion, Griffon’s ill-advised decision to buy Hunter Fan Company from MidOcean Partners demonstrates the Board’s continued disregard for shareholders and causes us to further question whether Griffon’s directors are protecting Griffon’s shareholders’ best interests.”

Voss also argued that Griffon was paying a higher multiple for Hunter than Griffon’s own trading valuation. “Griffon is paying 9.4x their estimate of fiscal 2023 EBITDA for Hunter Fan Company. Griffon currently trades at under 8x EV/FY 2023 EBITDA and is paying a far higher multiple to acquire Hunter Fan Company than Griffon’s current or recent valuation. Given Griffon is trading near a 5-year low valuation and building products transaction valuations are hitting record highs, we believe the Company should be selling not buying.”

The proxy fight was contentious, but Griffon ultimately prevailed—and then executed the two moves that, together, finished the transformation: it bought Hunter, and it sold Telephonics.

With the divestitures of Systems Engineering Group in 2020 and Telephonics in 2022, Griffon exited defense electronics entirely. The company that started in defense, then built garage doors, then lawn tools, then home storage, now stood as a focused home and building products business—with a clearer portfolio, clearer priorities, and far less “what are you, exactly?” baggage.

After more than six decades, the mythical griffon—half-lion, half-eagle—had finally chosen its form.

IX. Modern Era: The Focused Powerhouse (2022–Present)

Today, Griffon is what it spent decades trying not to be: simple. The company that started in defense electronics, wandered through the anything-goes conglomerate era, and nearly got knocked out in 2008 now reads like a focused play on the home—what people build, improve, and live in.

That focus shows up in the results. In fiscal 2024, Griffon generated $2.6 billion in revenue, slightly down from the prior year. But profitability moved the other way: net income rose to $209.9 million, or $4.23 per share, compared to $77.6 million, or $1.42 per share, the year before. On an adjusted basis—stripping out items affecting comparability—net income was $254.2 million, or $5.12 per share, versus $247.7 million, or $4.54 per share, in fiscal 2023.

Adjusted EBITDA in fiscal 2024 was $513.6 million, modestly higher than the prior year. And the bigger story is the long-term shape of the business: recent adjusted EBITDA margins have been running in the high teens to low twenties, up meaningfully from roughly the mid-teens over the prior five years. Compared with 2020, earnings power has roughly doubled.

Most importantly, the portfolio is no longer a debate—it’s two clearly defined segments.

Consumer and Professional Products, or CPP, is Griffon’s collection of branded everyday categories: non-powered tools, residential and commercial fans, and home storage and organization. This is the segment that houses brands like AMES (with roots back to 1774), True Temper, Hunter (since 1886), and ClosetMaid.

Home and Building Products is essentially Clopay. Founded in 1964, Clopay is the largest manufacturer and marketer of garage doors and rolling steel doors in North America. Residential and commercial sectional garage doors go out under brands like Clopay, Ideal, and Holmes, sold through professional dealers and big-box channels. Rolling steel doors and grilles for commercial, industrial, and institutional use are sold under the CornellCookson brand.

In those categories, Griffon doesn’t just participate—it leads. It’s number one in North America in garage doors. It holds leading share in non-powered lawn and garden tools. Hunter is the leading U.S. brand in residential ceiling fans. ClosetMaid remains a leader in home storage and organization. These are the kinds of positions that create real staying power: scale in manufacturing, leverage with distribution, and brands that matter at the point of purchase.

With that foundation, Griffon has leaned into a familiar playbook: invest, keep leverage in check, and return cash when it makes sense. In 2024, the company returned $310 million to shareholders through dividends and share repurchases, while maintaining year-over-year leverage at 2.6x and continuing to invest in capacity expansion, modernization, and technology across the portfolio.

The repurchases have been especially aggressive. From April 2023 through November 12, 2024, Griffon repurchased 9.4 million shares—about 16.4% of shares outstanding—for $458.0 million, at an average price of $48.74 per share. The board also approved a $400 million share repurchase authorization and increased the quarterly dividend by 20% to $0.18 per share. As Kramer put it, these moves reflected “the strength of our businesses” and management’s confidence in the plan.

Guidance suggests Griffon expects to hold steady on sales while pushing profitability higher. For fiscal 2025, the company expects revenue to be consistent with fiscal 2024 at $2.6 billion, with adjusted EBITDA of $575 million to $600 million. By segment, Griffon anticipates both HBP and CPP revenue will be in line with 2024, with HBP EBITDA margins expected to remain above 30% and CPP margins above 9%.

Credit markets have noticed the transformation, too. S&P Global expects Griffon to keep adjusted leverage below 4x through most normal business conditions and to remain opportunistic on bolt-on acquisitions and shareholder returns, supported by expected annual operating cash flow of roughly $350 million to $375 million in fiscal 2025 and 2026. S&P also raised its issue-level ratings on Griffon’s senior secured debt to BB+ from BB, and its senior unsecured debt to B+ from B—reflecting improved credit measures even as conditions are expected to be less favorable over the next 12 to 24 months.

Still, the modern Griffon isn’t immune to the world it operates in. Uncertainty around U.S. tariff policy is a real risk, particularly if input costs rise faster than the company can pass them through. And in tools and fans, some product lines carry supply chain exposure to China.

Then there’s the big macro variable: housing. The post-pandemic period has been defined by higher interest rates, which have pressured new home construction and, to a lesser extent, renovation activity. Griffon’s answer has been execution—pricing discipline, tight cost management, and a focus on holding or gaining market share even when the market itself slows.

That’s what a focused Griffon looks like: not a company hoping cycles break its way, but one built to keep compounding through them.

X. The Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Griffon’s journey—from a “what exactly do you do?” conglomerate to a focused home and building products leader—leaves behind a playbook that’s useful far beyond this one company.

The Art of the Strategic Pivot: Knowing When to Hold and When to Fold

The hardest moves in corporate strategy aren’t the acquisitions. They’re the goodbyes.

Telephonics wasn’t just another division. Griffon had owned it since 1961. It was the original identity: defense electronics, long programs, blue-chip government customers. Selling it meant admitting something most companies resist admitting—that the business that built you might not be the business that should define you.

The same pattern showed up with Clopay Plastics. Plastic film had been part of Clopay since 1952. It wasn’t a broken asset. But it wasn’t the future Griffon wanted, either. Strategic focus meant freeing up capital and management attention to double down on the home-and-building-products platform instead of keeping a legacy operation because it had history.

Capital Allocation as Competitive Advantage

Ron Kramer brought a capital allocator’s mindset to an operator’s job. In Griffon’s world, every dollar competes with every other possible use: buy a business, invest in plants and automation, pay down debt, pay a dividend, repurchase shares. The company’s edge wasn’t just “doing deals.” It was being willing to do nothing until the math and the strategy both worked.

You can see that discipline in the buybacks. When management believed the stock offered better returns than available deals, they acted accordingly. Since April 2023, Griffon retired more than 16% of its shares outstanding. That isn’t a gimmick. It’s what rational capital allocation looks like when the internal opportunity set beats the external one.

Why Focus Beats Diversification in the Modern Era

The old conglomerate pitch was that management could diversify risk for shareholders. But shareholders can diversify on their own. What they can’t easily manufacture is operating focus, scale, and the compounding advantage that comes from being great at a narrow set of things.

Griffon lived both models. As a grab-bag of unrelated businesses, it carried complexity and a valuation discount. As a focused home and building products company, it became easier to understand, easier to compare, and easier to underwrite—by investors, lenders, and its own management team.

Managing Cyclicality in Housing-Exposed Businesses

Even the modern Griffon still lives with a reality it can’t diversify away: housing cycles matter. That makes balance sheet management part of the strategy, not an afterthought. The goal is to stay strong enough to ride out the down cycles, while keeping enough capacity and agility to capture the up cycles.

Griffon’s leverage of roughly 2.6x EBITDA reflects that balancing act. It’s not timid, but it’s also not reckless—especially for a company that has lived through 2008. The stated commitment to staying below 4x through normal conditions is basically the scar tissue talking.

The Importance of Market Leadership in Fragmented Industries

One of the most consistent choices Griffon made was where to play: categories where leadership matters, and where the industry is fragmented enough for a rollup to work.

Across its major moves, the targets weren’t random. They were market leaders: garage doors, lawn and garden tools, ceiling fans, home storage. Leaders get advantages that don’t show up neatly on a spreadsheet—preferred shelf space, better dealer relationships, more efficient manufacturing, stronger brands at the point of purchase, and more ability to take price when costs move. And in a fragmented market, the consolidator tends to keep getting stronger with each deal.

For anyone tracking Griffon from here, the “watch list” is refreshingly simple: segment adjusted EBITDA margins (especially whether HBP stays above 30% and CPP above 9%), free cash flow conversion (which should remain strong in the post-transformation portfolio), and demand signals from major retail partners—because same-store trends at Home Depot and Lowe’s still matter disproportionately for CPP.

XI. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

To understand how durable Griffon’s transformation really is, you have to look past the deal history and into the competitive physics of the markets it plays in. Two lenses help: what the structure of these industries allows (Porter), and what advantages a company can build that actually stick (Hamilton).

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry: Moderate to High

Griffon’s categories aren’t sleepy. In garage doors, it goes up against major players like Overhead Door Corporation, Wayne-Dalton (owned by Overhead Door), Amarr (owned by Entrematic), plus a long tail of regional competitors. The market is consolidated enough that it can avoid pure price chaos, but competitive enough that share gains are fought for—especially when housing slows and everyone is chasing the same replacement demand.

In lawn and garden tools, AMES faces big branded competitors like Fiskars and Stanley Black & Decker, along with plenty of private-label products sitting right beside it on the shelf. Hunter Fan sees a similar dynamic, competing with Emerson’s ceiling fan business, Minka Group, and others. Griffon’s scale helps—but it doesn’t remove the need to win every season, every reset, every product cycle.

Threat of New Entrants: Low to Moderate

Barriers to entry depend on the product line. Garage doors are harder to break into than they look. You need meaningful capital to build plants, you need a distribution footprint, and you need years to build dealer relationships and a service reputation that installers are willing to stake their name on. Griffon’s network of more than 50 distribution centers across North America is the kind of asset that takes time and money to replicate.

Non-powered tools are easier to manufacture, but the real gate is the channel. Retailers don’t want supply surprises, quality issues, or warranty headaches. For a new entrant, it’s a classic chicken-and-egg problem: you need distribution to build awareness, but you need awareness to earn distribution.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate

The inputs are mostly commodities: steel, resin, wood, aluminum. That keeps individual supplier power in check because there are generally multiple sources. The catch is that commodities don’t need a monopoly to hurt you. When the whole supply chain tightens—as it did in 2021 and 2022—price spikes can slam margins before pricing catches up. Griffon has shown it can pass through costs, but timing lags are real.

Some components can also have more concentrated supply, and tariff uncertainty—particularly around Chinese imports—adds another layer of operational complexity.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High in Retail, Moderate in Commercial

In the retail channel, buyer power is the blunt instrument. Home Depot and Lowe’s are enormous customers, and they negotiate like it. Even if you’re the category leader, they can demand pricing, terms, promotions, and service levels that squeeze suppliers. The ever-present alternative is private label, which keeps the pressure on.

Commercial and industrial is different. With CornellCookson products, demand often flows through specification—architects, engineers, and project requirements. Installed products also come with service expectations, warranty considerations, and dealer relationships. That fragmentation and stickiness generally makes buyer power more moderate than in big-box retail.

Threat of Substitutes: Low to Moderate

A garage door doesn’t have many true substitutes. Buildings need closure systems, and garage doors fill a very specific role. Competition shows up more as feature evolution—insulation, smart connectivity, design—than a product being replaced by something entirely different.

Tools have more substitution risk at the edges. Electric and robotic solutions can reduce demand for certain manual tasks, but for most homeowners, non-powered tools remain the default because they’re cheap, reliable, and good enough. Ceiling fans have an interesting dynamic: better HVAC can substitute for them, but fans also win on aesthetics and as a low-cost way to make a room feel cooler.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework

Scale Economics: Strong

This is the heart of Griffon’s advantage. In garage doors, scale matters because the business has real fixed costs: factories, tooling, distribution centers, logistics systems. If you’re shipping the most volume, you spread those costs the widest—and your cost per unit drops. A dense distribution footprint also means faster delivery and lower shipping costs per door, which is a big deal for bulky products.

CPP gets some of the same benefits through manufacturing and sourcing scale in tools and fans, though those advantages are less absolute in the parts of the market where low-cost Chinese competition is strongest.

Network Effects: Limited

Griffon doesn’t get much help from network effects. These are physical products, not platforms. There’s no winner-take-all flywheel where each new customer automatically makes the product better for the next one. That means defensibility has to come from execution, not inevitability.

Counter-Positioning: Historically Yes, Diminishing

For a while, Griffon benefited from being structurally set up to do what others couldn’t. Many traditional industrial conglomerates had too much complexity and too much bureaucracy to run a tight buy-and-build strategy well.

But that edge has narrowed. Private equity firms have gotten extremely good at rollups, and they often show up with plenty of capital and the same playbook. Today, Griffon’s advantage here comes less from being “the only one who can” and more from being a proven strategic buyer with a long integration track record.

Switching Costs: Moderate in Commercial, Low in Retail Consumer

On the commercial side, switching costs can be meaningful. Once a building is designed around specific rolling steel doors and grilles, changing suppliers isn’t just swapping SKUs. It can involve design changes, warranty implications, and service relationships. Dealers also invest in training, familiarity, and sometimes inventory around the manufacturers they sell.

For retail consumer products, switching costs are low at the end customer level. A homeowner choosing a shovel doesn’t face much friction. The more meaningful stickiness is one level up: retailers value suppliers that deliver consistently, manage quality, and support the category without drama.

Branding: Strong in Niche Categories

Griffon’s brands aren’t global lifestyle icons, but they don’t need to be. In their categories, they mean something. Clopay markets itself as “America’s Favorite Garage Doors.” AMES has roots going back to 1774. Hunter has more than a century of ceiling fan heritage. True Temper carries real credibility in lawn tools.

That brand equity shows up in practical ways: premium price realization, better shelf placement, dealer preference, and fewer headaches when customers care about quality and service—especially in installed products like garage doors.

Cornered Resource: Market Positions and Channel Relationships

Griffon’s leading positions behave like a semi-cornered resource. Being the largest garage door manufacturer tends to bring the best dealer relationships, the broadest distribution, and the strongest manufacturing efficiency—and those advantages reinforce each other over time.

Retail relationships cut both ways. Home Depot and Lowe’s have real negotiating leverage, but long-standing partnerships, integrated systems, and a history of execution are valuable—and not easy for a competitor to replicate overnight.

Process Power: Integration Playbook

This is the quiet one, and it matters. Griffon has built repeatable muscle around acquisitions: finding targets, integrating operations, capturing cost savings, and bringing brands into a common operating cadence without breaking what made them attractive in the first place.

Process power doesn’t make bad deals good, and it doesn’t guarantee future success. But it improves the odds that reasonable deals actually turn into value.

Overall Assessment

Griffon’s defensibility comes mostly from Scale Economics in manufacturing and distribution and Branding in specific, high-consideration categories. It also has meaningful Switching Costs in commercial door products and real Process Power from years of integration work.

But it’s not invincible. Without network effects, Griffon has to keep earning its advantages. Scale only stays scale if share holds. Brands only stay strong if quality and innovation keep up. And the acquisition machine only matters if attractive assets exist at prices that still leave room for returns.

XII. Bear vs. Bull Case

Bull Case

Market Leadership in Structurally Growing Categories

America’s housing stock keeps getting older, and older homes don’t politely wait for the economy to feel good before they demand attention. Renovation and replacement spending should keep rising over time as Baby Boomer-era homes age into constant maintenance mode and Millennials put money into the places they now own. Griffon sits directly in the path of that spend: garage doors, lawn and garden tools, ceiling fans, and storage and organization.

And some of this demand is closer to “needs” than “wants.” Garage door replacement, in particular, is often non-discretionary. Springs fail. Doors get damaged. Safety standards and technology improve. With an installed base of roughly 50 million residential garage doors in North America, there’s a built-in replacement engine that can keep turning even when new construction slows.

Proven Acquisition and Integration Capabilities

Griffon has shown it can do the hard part of a rollup strategy: not just buy businesses, but absorb them without breaking what made them valuable. AMES, ClosetMaid, CornellCookson, and Hunter all fit the same general pattern—category leadership, clear channels to market, and room for operational improvement—and the outcomes have generally lined up with expectations.

Just as important, the opportunity set is still there. Home and building products remain fragmented, which means tuck-ins are available. And Griffon’s willingness to walk away when pricing gets silly is a real edge; discipline on valuation is what keeps “growth through acquisition” from turning into “growth through regret.”

Margin Expansion Opportunities

The margin profile today is meaningfully better than Griffon’s historical baseline, and there’s still room to run. Home and Building Products has been generating EBITDA margins above 30%, which is exceptional for an industrial manufacturing business. Consumer and Professional Products, with margins above 9%, has clear levers too—operational execution, footprint optimization, and continued manufacturing rationalization.

Griffon’s global sourcing approach also matters here. The ability to balance production between domestic and international facilities isn’t just a cost lever; it’s a structural advantage that can keep compounding through procurement and manufacturing efficiency over time.

Housing Market Recovery Tailwinds

If and when interest rates stabilize and decline, housing activity should recover. Griffon doesn’t need to predict the exact timing to benefit; it just needs to be positioned when demand returns. The appealing part is operating leverage: the company should be able to capture incremental volume without needing a proportional step-up in investment.

Strong Free Cash Flow Generation

Griffon’s business mix has become relatively modest in capital intensity, and with good working capital management, free cash flow can run ahead of net income. That cash funds the whole flywheel: shareholder returns through dividends and buybacks, debt reduction, and selective acquisitions—without having to constantly tap outside capital.

Management Track Record

Ron Kramer has been CEO since 2008 and has been on the board since 1993. Whatever you think of individual deals, the arc is hard to dispute: Griffon went from a confusing conglomerate to a focused owner of home and building products brands, and that simplification created real value. Management also has meaningful equity ownership, which helps keep incentives aligned with shareholders.

Bear Case

High Exposure to Cyclical Housing Markets

Even after diversifying within home and building products, Griffon still lives in housing’s weather system. When recessions hit, housing starts tend to get crushed. Renovation spending slows when consumers feel uncertain. Commercial construction follows the broader economy.

Griffon has lived this movie before. In 2008 and 2009, it survived—but it survived by raising capital and making major portfolio changes under stress. A future severe downturn could test the balance sheet again, especially if it arrives alongside tight credit markets.

Concentration Risk with Big-Box Retailers

In CPP, the channel is powerful and concentrated. Home Depot and Lowe’s are dominant, and they negotiate accordingly—pricing, promotional expectations, service levels, terms. The private-label threat is the constant pressure in the room.

And retailer relationships can change faster than suppliers want to believe. If a major partner expands private label, shifts shelf space, or rotates to alternative suppliers, the impact on volumes and profitability could be meaningful.

Commodity Cost Inflation and Margin Pressure

Steel, resin, aluminum, and wood are core inputs. When those costs spike, margins can compress before pricing catches up. The 2021–2022 period made the timing mismatch obvious: inflation can move immediately; price realization often lags.

Tariffs add another layer of uncertainty. If costs rise on products sourced from China and pass-through is incomplete or delayed, profitability can take a hit.

Rising Interest Rates

Higher rates can pressure Griffon from multiple directions at once: interest expense rises on floating-rate debt, housing demand weakens, and acquisition financing becomes more expensive. If higher rates persist, the headwind isn’t just a bad quarter—it becomes part of the environment.

Integration Execution Risk

Future deals always carry integration risk, and the Hunter acquisition is the obvious focal point. It was the largest in Griffon’s history and drew activist criticism over both price and execution risk. While early performance has looked encouraging, integration issues have a way of surfacing later—through channel conflict, supply chain complexity, or operational friction that takes longer to work out than expected.

Competition from International Manufacturers

In several categories, international competitors—especially Chinese manufacturers—can operate at lower cost. Tariffs can blunt the impact, but they don’t erase the underlying cost differential. The pressure is most acute in price-sensitive retail segments where the shelf doesn’t reward brand equity as much as it rewards a lower unit price.

Conglomerate Discount May Persist

Griffon is far more focused than it used to be, but it still isn’t a single-product pure play. Some investors may prefer owning “just garage doors” or “just fans” rather than a bundled portfolio. The market may not fully reward the “sum of the parts” logic even after the defense exit, which can limit valuation upside.

Key Metrics to Watch

For anyone tracking Griffon from here, three indicators do most of the work:

-

Segment adjusted EBITDA margins: HBP staying above 30% and CPP above 9% is a quick read on pricing power, cost control, and whether competition is intensifying.

-

Free cash flow conversion: In a business like this, cash generation should hold up well relative to net income. If it doesn’t, that’s usually an early warning sign.

-

Same-store sales trends at major retail partners: Big-box performance is a proxy for both end-market demand and whether Griffon is holding share where it matters most.

XIII. Epilogue & Future Outlook

So where does Griffon go from here?

In the near term, it comes down to a familiar question: what do you do with the cash? With expected annual operating cash flow north of $350 million and meaningful remaining buyback authorization, Griffon has plenty of levers to pull. It can keep shrinking the share count. It can keep the balance sheet conservative. And it can keep doing what it’s gotten very good at—small, adjacent acquisitions that deepen the platforms it already owns.

Those tuck-ins are still out there. Home and building products remain fragmented, which is exactly the environment where Griffon’s playbook works. Over time, you could also see it push further internationally. Today the footprint already stretches beyond North America into the UK and Australia; adding new geographies would be a logical next step if the returns pencil out.

The biggest external variable is still housing. Higher rates have been a headwind, and lower rates—whenever they arrive—should be a tailwind. No one gets to know the timing in advance. But the directional bet is straightforward: people will keep buying homes, repairing homes, renovating homes, and spending money on the spaces they live in. That’s the river Griffon has chosen to fish in.

E-commerce is another force that cuts both ways. Hunter’s growth in direct-to-consumer shows that digital channels can be an accelerant, not just a threat, and a way to build a more direct relationship with end customers. The obvious opportunity is to bring more of that capability across the rest of the portfolio. The obvious risk is that the internet also makes it easier for private label and international sellers to show up with lower prices, turning certain categories into a race to the bottom unless brands and quality keep earning their premium.

Then there’s sustainability—less a buzzword than an increasing expectation. Efficiency projects in manufacturing often pay for themselves while also reducing waste and energy use. And product innovation can become a real differentiator, whether that’s better insulation and energy performance in garage doors, or more sustainable materials and packaging in tools and home organization.

Zooming out, the long-term strategic question is the one every successful consolidator eventually faces: stay independent, keep compounding, and remain the buyer—or become the target. Griffon could continue running its current model for years, steadily consolidating where it has an edge and returning cash along the way. But a focused portfolio of leading home-and-building brands could also be attractive to private equity or a larger strategic acquirer that wants the exposure and the cash flow.

If there’s a reason to believe Griffon will handle that decision thoughtfully, it’s history. It’s navigated activist pressure. It has shown it will consider strategic alternatives when they make sense. And with meaningful equity ownership at the top, the incentives are pointed toward value creation—regardless of what form it takes.

What makes Griffon’s story unusual isn’t that it transformed. It’s that it transformed successfully, over decades, and in public. Plenty of conglomerates talked about focus; Griffon actually did it, even when it meant selling businesses that had defined the company for generations. Plenty of companies got hit in 2008 and never truly recovered; Griffon used the crisis as a forcing function. Plenty of rollups blow themselves up with overpayment and sloppy integration; Griffon built real competitive positions by staying disciplined.

And the broader lesson has nothing to do with garage doors or lawn tools. Reinvention is possible—but it requires strategic clarity, patient capital allocation, and the operational discipline to make a plan real. The mythical griffon was a symbol of strength through diversity. Modern Griffon found a different kind of strength: the willingness to be exceptional at a few things instead of average at many.

XIV. Further Reading

If you want to go beyond the narrative and see the receipts—how the strategy evolved, how the deals were justified, and how the numbers actually moved—these are the best places to spend your time:

-

Griffon Corporation Annual Reports (2008-2024) - The most complete record of the transformation, told in management’s own words.

-

Griffon Investor Presentations - Especially the 2021-2022 decks laying out the Telephonics divestiture and the rationale behind the Hunter acquisition.

-

"The Outsiders" by William Thorndike - A great lens on capital allocation discipline, and a useful benchmark for judging Griffon’s choices.

-

Harvard Business Review: "The Conglomerate Discount" - A clear explanation of why diversification stopped being “the safe strategy,” and why focus tends to get rewarded.

-

McKinsey: "The Build-and-Buy Strategy" - Modern thinking on rollups—what works, what breaks, and where integration actually creates value.

-

Transcript: Griffon Q4 2022 Earnings Call - A direct window into management’s portfolio-optimization mindset around the Telephonics sale.

-

Industry Reports: FDMC (Fenestration & Door Manufacturers Conference) - Helpful context on the garage door market dynamics that underpin Clopay’s position.

-

"Built to Last" by Collins & Porras - A classic on endurance and reinvention—useful thematic framing for a decades-long corporate pivot like Griffon’s.

-

S&P Global Rating Reports - Independent credit analysis that’s often more candid than equity research about risk, leverage, and cyclicality.

-

SEC Filings (8-K, 10-K, 10-Q, Proxy Statements) - The primary sources: deal terms, governance details, and the fine print behind the headlines.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music