Greenbrier Companies: The Story of North America's Railcar Empire

Introduction: The Invisible Infrastructure Empire

Every day, roughly 1.7 million railcars crisscross North America. They haul the grain that becomes your cereal, the oil that becomes your gasoline, and the chemicals that end up in everything from medicine to plastic packaging. Most of us never notice them. And almost nobody knows the names of the companies that design them, build them, repair them, and finance them.

One of those companies started in Oregon and, over the next few decades, quietly assembled something that looks a lot like an industrial empire: manufacturing, refurbishment, leasing, and fleet management tied together into one system. It expanded beyond North America, built a footprint across three continents, and—crucially—made it through moments when the whole business should have snapped in half.

That company is The Greenbrier Companies. It’s a publicly traded transportation manufacturing corporation headquartered in Lake Oswego, Oregon, best known for freight railcar manufacturing, railcar refurbishment, and railcar leasing and management services. Greenbrier is also one of the leading designers, manufacturers, and marketers of rail freight equipment in North America and Europe.

Formed in 1981 and public since 1994, Greenbrier generated about US$3.49 billion in revenue. Along the way, what began as a small operation—one that, early on, included two executives buying a lease-underwriting division for just a few million dollars—grew into a global platform. What was once two railcar production lines became a multibillion-dollar operation with manufacturing spread across 12 facilities on three continents, integrated with aftermarket, leasing, and services businesses.

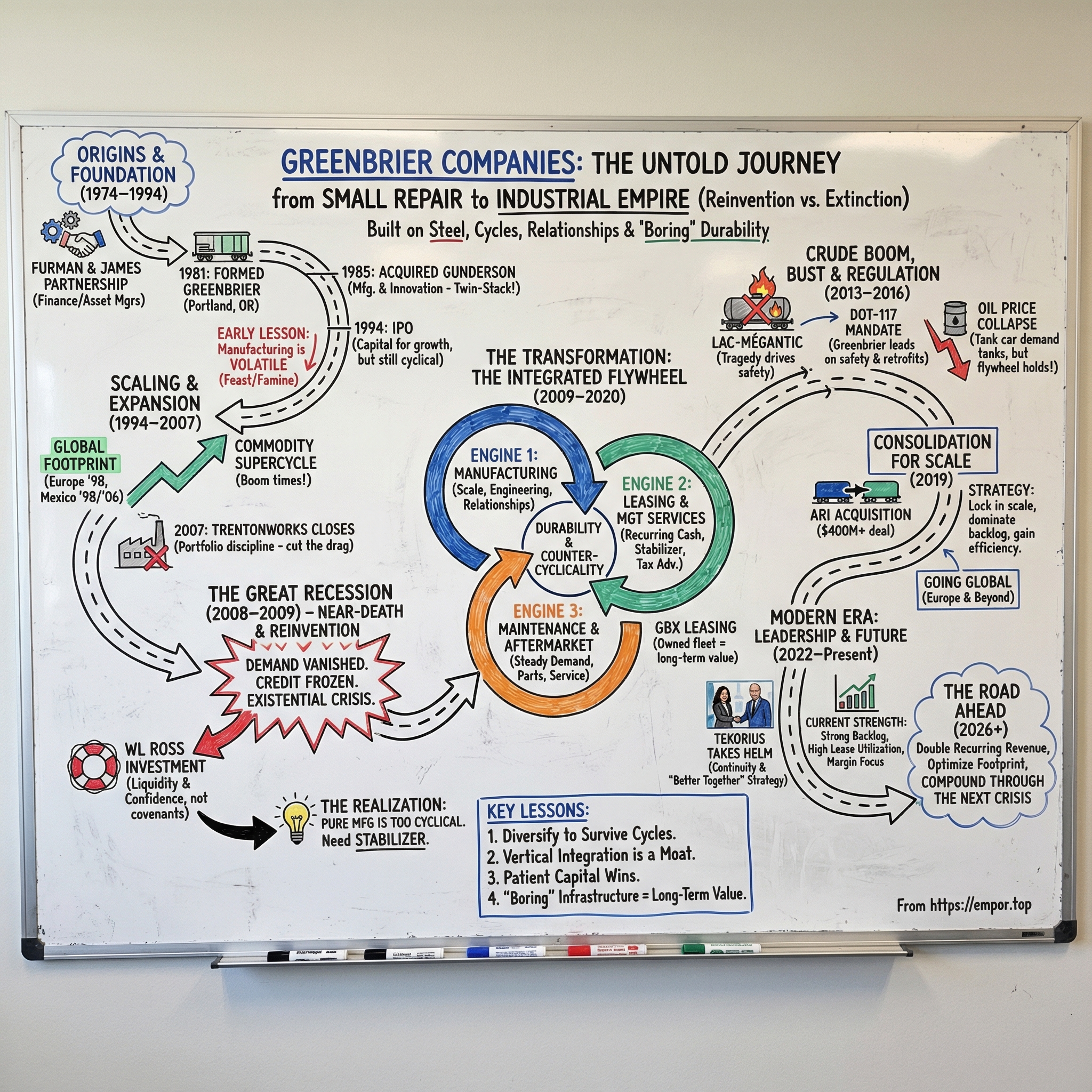

Here’s the real hook: how did a small Pacific Northwest operation become a critical piece of the freight transportation machine? The answer is a forty-year slog through boom-and-bust cycles, pivots made under existential pressure, and a steady evolution from “we build railcars” into something far more durable: a vertically integrated flywheel where manufacturing feeds leasing, leasing drives service and aftermarket demand, and the whole system keeps producing cash flow even when the cycle turns.

This is the story of Greenbrier: a masterclass in surviving cyclicality, vertical integration done right, and why the most “boring” industrial businesses can end up being extraordinary—if you build them to last.

The Railcar Industry 101: Why This Business Exists

To understand Greenbrier, you have to understand a weird, almost hidden rule of North American freight: most railcars aren’t owned by the railroads.

In airlines, the carrier owns the plane. In trucking, the fleet owns the rigs. But the Class I railroads—BNSF, Union Pacific, CSX, Norfolk Southern, Canadian National, and Canadian Pacific Kansas City—own only a slice of the cars rolling over their tracks. The rest are owned by shippers, leasing companies, and specialized equipment providers. That split isn’t an accident. It’s the product of history, regulation, and simple capital logic. Railroads would rather sink their money into locomotives, track, and network technology than tie up billions in rolling stock. Meanwhile, shippers want cars built for their exact cargo: covered hoppers for grain, tank cars for chemicals, intermodal equipment for consumer goods.

That structure creates the industry’s three-sided system: manufacturers build the cars, lessors buy and lease them, and railroads run the network. Many companies live in just one lane. The most formidable ones—Greenbrier included—figure out how to operate across multiple lanes at once.

The next thing you need to know is that this business swings hard. Demand for new, refurbished, used, and leased railcars rises and falls with the economy and with shipper behavior. When times are good, order books swell. When times turn, they don’t soften—they can collapse. The industry’s history is full of “feast or famine” whiplash: around the early 1980s recession, production fell from the thousands to just a handful in a few years. That’s the kind of volatility Greenbrier would eventually have to engineer its way around.

Different car types also follow different cycles. Covered hoppers—workhorses for agriculture and some chemicals—tend to be steady, in part because they live long lives and they’re constantly being maintained and rebuilt. That ongoing maintenance matters: railcars aren’t just sold, they’re supported for decades, and that aftermarket pull-through becomes its own source of durability.

Broadly, the customer universe breaks into a few buckets. Energy needs tank cars for crude, ethanol, and chemicals. Agriculture runs on covered hoppers for grain and fertilizer. Consumer goods ride intermodal equipment—containers and double-stack cars. And automakers rely on specialized auto racks. Each segment has its own trigger points, its own booms and busts, and its own winners.

Finally, this is not an easy market to enter. Railcars are expensive to design and build, quality expectations are unforgiving, and customers buy on trust as much as on price. A small number of scaled manufacturers dominate, which makes the industry an oligopoly in practice: capital-intensive, relationship-driven, and hard to break into.

The takeaway is simple: the railcar business doesn’t reward the flashiest operator. It rewards the ones that can survive the troughs. If you can stay standing—through diversification, operational flexibility, and disciplined finance—you don’t just make it to the next upcycle. You usually come out of it stronger.

Origins & The Furman Years: Building the Foundation (1974–1994)

Greenbrier didn’t start as a factory story. It started as a finance-and-assets story—two executives who saw, early, that the real leverage in rail isn’t just building equipment. It’s managing it, financing it, and knowing where the cycle is headed.

In 1974, William A. Furman and Alan James bought the lease-underwriting division of their former employer and launched James Furman and Co. The partnership initially focused on asset management and remarketing—railcars, and even commercial jet aircraft. A few years later, starting in 1979, their firm managed Greenbrier Leasing Corporation on behalf of its owner, Commercial Metals Company.

Furman brought a rare kind of preparation for this industry. He earned an undergraduate degree in Economics (Phi Beta Kappa), then a Master’s in Transportation Economics at Washington State University, where he studied under Dr. James C. Nelson—a prominent rail economist and a key intellectual force behind the Staggers Act, the deregulation wave that reshaped North American rail in the late 1970s. That background gave Furman something most operators didn’t have: a clear view of how regulation would change the economics and competitive landscape.

Before Greenbrier, Furman was at FMC Corporation, a Fortune 500 industrial company. At just 25, he became the first general manager of FMC’s Finance division, founding it as a captive sales finance arm.

James’ résumé was just as unconventional—and perfectly complementary. He worked as an engineer at Sylvania’s Electronics Defense Laboratories on classified national defense projects, then went to Boeing as part of a contract attorney team on the SSI project and as a contract lawyer for Middle East affairs. Later, at GATX-ARMCO-Boothe, he was senior vice president and helped drive substantial growth in commercial jet aircraft leasing. Between the two of them, they had finance, engineering, contracts, and leasing—basically the toolkit for building a modern asset platform long before that phrase was fashionable.

The pivot from “asset managers” to “company builders” came in 1981. When Commercial Metals decided to sell its leasing operation, James and Furman bought it through what became The Greenbrier Companies, and soon moved the business from Dallas to Portland, Oregon.

But the moment Greenbrier truly changed shape—from managing railcar assets to building them—arrived in 1985. That year, The Greenbrier Companies acquired FMC Corporation’s Portland-based Marine and Rail Car Division and restored the name Gunderson, Inc.

Gunderson wasn’t just a facility. It was a Portland institution with a long industrial lineage: founded in 1919 as the Wire Wheel Sales and Service Co. by Chester E. Gunderson, joined by his brother Alvin a few years later, and incorporated in 1921. The company evolved with the region’s needs—selling and repairing wheels, then engine parts, then trailer brakes, and eventually manufacturing trailers to haul logs, dry cargo, and petroleum products.

The acquisition also brought something even more valuable than a legacy: product innovation. In 1985, the newly renamed Gunderson, Inc. introduced the Twin-Stack, an intermodal container car originally developed as a prototype by FMC. It became a meaningful product line—about 3,000 were produced in 1990—and intermodal would go on to be a defining category for the company. By 2018, Greenbrier had produced more than 100,000 intermodal wells.

The late 1980s and early 1990s rewarded the move into manufacturing. As railway freight surged, Greenbrier’s sales more than doubled from 1989 to 1993, rising from $113.6 million to $264.3 million. Profits climbed even faster—from $1.76 million to $8.2 million.

That momentum set up the next milestone: going public. In 1994, The Greenbrier Companies completed its IPO. James, then chairman, and Furman, then chief executive, retained 65 percent ownership.

The IPO wasn’t just about raising cash. It created a stronger platform for expansion—and a currency for deals. In 1995, Greenbrier acquired a majority interest in Trenton Works, a railcar manufacturing facility in Nova Scotia, Canada. The purchase nearly doubled Greenbrier’s railcar manufacturing capacity to more than 5,000 a year.

Even in these early years, you can see the pattern that would define the company later: James and Furman didn’t treat manufacturing as the whole game. They built around it—leasing, management services, and production working together—planting the seeds of the integrated model that would matter most when the cycle inevitably turned.

Geographic Expansion and the Scaling Era (1994–2007)

After the IPO, Greenbrier stopped being a Pacific Northwest railcar story and started acting like a company with continental ambitions.

In 1998, it pushed into Europe by acquiring the Polish railcar manufacturer Wagony Świdnica. That same year, it made an even more consequential move south: a joint venture with Bombardier Inc. inside a former Concarril facility in Sahagún, Mexico.

The Mexico bet had a simple, hard-nosed logic. Labor costs were lower, the plant was close enough to serve U.S. customers, and NAFTA made cross-border manufacturing workable. In 2004, Greenbrier acquired Bombardier’s stake in the venture. The operation became what’s now known as Greenbrier Sahagún.

Then the mid-2000s arrived, and with them the commodity supercycle. As demand surged for oil, grain, and industrial materials, rail traffic followed—and the whole freight ecosystem geared up. Greenbrier spent the years leading into the crisis building capacity and capability, including a wave of rolling stock equipment acquisitions between 2006 and 2008. In 2006, it also formed the GIMSA joint venture in Mexico with Grupo Industrial Monclova, further deepening its manufacturing footprint there.

At the same time, Greenbrier was quietly strengthening the part of the business that doesn’t live and die by the order book. It had established its rail services division back in 1991, expanding maintenance and refurbishment. That would matter later, because repairs and servicing tend to stay alive even when new builds freeze.

By 2007, Greenbrier looked like it had it all: manufacturing across North America and Europe, a growing leasing portfolio, and services that brought in steadier, recurring revenue. But the scaling era also forced a hard lesson in economics. TrentonWorks, the Canadian facility Greenbrier had bought in the IPO aftermath, became a drag as exchange rates moved against it and Mexico offered structurally lower operating costs. Greenbrier closed TrentonWorks in 2007.

It was an early signal of how the company would operate when conditions got tougher: treat the footprint as a portfolio, not a museum. If the numbers stopped working, the sentiment didn’t get a vote.

And that mattered because the next chapter wasn’t another expansion story. It was survival. The 2008 financial crisis was coming—and it would push Greenbrier to the edge.

The 2008-2009 Crisis: Near-Death and Reinvention

The Great Recession hit the railcar industry like a sudden brake application at full speed. Commodity prices fell, global trade slowed, and financing—the oxygen of big-ticket equipment purchases—nearly disappeared. Orders didn’t drift down. They vanished. What had been record backlogs turned into a scramble to stay alive.

One moment captured the new reality. In December 2009, Greenbrier announced an agreement with General Electric Railcar Services Corporation (GER), a subsidiary of GE Capital, to modify a major manufacturing contract. Back in 2007, the deal called for Greenbrier to build 11,900 new tank cars and hopper cars for GER over eight years, with the final 8,500 units contingent on Greenbrier meeting certain contractual conditions. Deliveries began in December 2008, and by that point around 600 cars had been delivered and accepted.

Now came the renegotiation. Under the modified terms, the parties agreed to cut the total down to up to 6,000 railcars.

It wasn’t just one contract getting smaller. It was a signal flare for the entire market: even customers with long-term commitments were looking for exits, delays, and do-overs. And for manufacturers, there’s no real leverage when your buyers are slamming the brakes and the rest of the industry is begging for work. Greenbrier had to take the reduction, protect what backlog it could, and keep moving.

What made this period truly existential wasn’t only demand—it was capital. Greenbrier was carrying debt into the worst credit environment in decades, when banks didn’t want to lend and customers couldn’t finance purchases. This is where the WL Ross investment became critical.

The initial $75 million investment came as a three-year, non-amortizing term loan with no financial covenants, priced at LIBOR plus 350 basis points. Alongside the loan, Greenbrier issued warrants to purchase approximately 3.378 million common shares—about 16.5 percent of the company on a pro forma basis—at $6.00 per share. WL Ross also planned to purchase at least $1.5 million of Greenbrier common stock in the open market.

“WL Ross is a top-tier partner and this new relationship is a testament to the success of our integrated business model,” said William A. Furman. “Our expansion into adjacent, less cyclical markets has dampened the effects of the current downturn and has positioned us to attract this capital on favorable and flexible terms.”

The structure was the point: liquidity without a web of covenants that could trip the company at the worst possible time, plus equity upside for the investor if Greenbrier survived and recovered. Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., founder, chairman and chief executive officer at WL Ross, and Wendy Teramoto, senior vice president at WL Ross, joined Greenbrier’s Board of Directors. WL Ross, based in New York City, had sponsored more than $8 billion of equity-linked investments since its inception in 2000.

Mark Rittenbaum, Greenbrier’s executive vice president and chief financial officer, put it in plain terms: “This strategic investment, along with our amended revolving credit facility, strengthens our balance sheet, improves our liquidity position, and increases our operating flexibility. Together with our recent cost reduction initiatives and improvements to working capital, Greenbrier is well positioned to weather the downturn, seize opportunities in the current environment and to build significant long term value for our shareholders.”

The immediate survival playbook was as brutal as you’d expect: cost cuts, shutdowns, workforce reductions, and contract renegotiations wherever possible. But the deeper consequence was strategic. The downturn made something undeniable. Pure manufacturing was simply too cyclical. When the cycle turned, revenue could fall off a cliff—and almost take the company with it.

And yet, even in the wreckage, there was a clue to the future. Greenbrier noted that, with the contract modification, it estimated the company held about 40% of the total new railcar industry backlog in North America—an outcome it believed was favorable not just for Greenbrier, but for the supply side of the entire industry.

The crisis didn’t just force Greenbrier to survive. It forced Greenbrier to evolve. The path forward wasn’t to become a better manufacturer in a market that could still disappear overnight. It was to build something that earned through the cycle—countercyclical revenue streams, led by leasing—so the next downturn wouldn’t be another near-death experience.

The Transformation: Becoming a Leasing Powerhouse (2009–2020)

Coming out of the financial crisis, Greenbrier leaned into a pivot that would reshape the company: it started treating leasing and management services not as a side business, but as the stabilizing center of the whole model.

The logic was simple, and powerful. Leasing throws off recurring revenue that doesn’t disappear when the manufacturing order book dries up. If you also build railcars, you can place your own production into your lease fleet—effectively turning lumpy, cyclical sales into long-lived assets that generate cash for years. Put the pieces together and you get a flywheel: manufacturing feeds leasing, leasing feeds services, and the installed base drives aftermarket work.

As CEO William Furman put it at the time, the move was “a logical bolt-on to Greenbrier’s leasing platform and commercial strategy,” creating “a new annuity stream of tax-advantaged cash flows” and reducing exposure to the ups and downs of new railcar orders. In other words: less dependence on the cycle, more income you could count on.

That strategy later accelerated through GBX Leasing. Greenbrier acquired 100% of GBX Leasing (GBXL), buying out its joint venture partner, The Longwood Group. The portfolio—made up primarily of railcars manufactured by Greenbrier—became part of a wholly owned subsidiary. Since GBXL’s inception in early 2021, the business delivered stable, tax-advantaged cash flows designed to complement the more cyclical revenues from new railcar manufacturing.

By the time Greenbrier laid out its plan at its April 2023 Investor Day, the direction was unmistakable. Management said it aimed to more than double recurring revenue from leasing and management fees, supported by investing up to $300 million net annually over the next five years.

Leasing also became a commercial weapon, not just a financial one. It gave Greenbrier another way to go to market—alongside direct sales, partnerships with operating lessors, and originating leases for syndication partners. The tradeoff was real: putting cars into a lease fleet can mean deferring revenue recognition versus an outright manufacturing sale, which can pressure manufacturing revenue and margin in the short term. But strategically, it tilted the company toward durability.

Even the crisis-era lifeline from WL Ross ended up looking like a turning point rather than a scar. Ross later pointed to Greenbrier’s rebound in revenues, backlog, and earnings as evidence the investment worked, and said share sales were made to give limited partners flexibility. Furman was blunt about what it meant in the moment: WL Ross gave Greenbrier liquidity, flexibility, a stronger balance sheet, and a vote of confidence when the industry was in free fall.

And the endgame wasn’t just “more railcars under lease.” The ambition was a more defensible, differentiated machine—one where being a major fleet manager creates information advantages and feedback loops that strengthen leasing, syndication, and service offerings over time.

The Crude Oil Boom and Regulatory Revolution (2013–2016)

Just as Greenbrier was climbing out of the financial crisis, the industry got yanked into a totally different kind of boom: shale oil. The Bakken in North Dakota, the Permian in Texas, and other unconventional plays pushed crude-by-rail from niche to necessity almost overnight. Pipelines couldn’t keep up. Rail could.

For railcar builders, that meant tank cars. Lots of them. Greenbrier’s order book surged and the company ramped capacity to meet the wave. But the tank-car rush also set the stage for a moment that would change the business permanently.

On 06 July 2013, just before 0100 Eastern Daylight Time, a Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway freight train, MMA-002, left Nantes, Quebec where it had been parked unattended for the night. It rolled for about 7.2 miles, reaching 65 mph. At about 0115, as it approached the centre of Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, 63 tank cars carrying petroleum crude oil (UN1267) and 2 box cars derailed. About 6 million litres of crude spilled. Fires and explosions followed, destroying 40 buildings, 53 vehicles, and the tracks at the west end of Megantic Yard. Forty-seven people were killed.

The wreck made one thing painfully clear: the tank cars then in service—especially older pre-CPC-1232 designs—were not built to withstand the kind of impacts derailments can produce. The physical damage at Lac-Mégantic showed that product release could have been reduced with more impact-resistant shells and heads. Design improvements weren’t a “nice to have.” They were a public safety imperative.

Greenbrier moved quickly to align itself with what it believed had to happen next: tougher rules, and faster. The company publicly urged regulators to require safer tank cars, pointing to a string of derailments and the findings tied to Lac-Mégantic. “Recent derailments, including the derailment in Saskatchewan on Tuesday, and the findings of the Quebec coroner related to the tragic death of 47 people in the Lac-Megantic accident underscore the urgency of taking concrete actions to improve tank car design for both newly-built tank cars and for tank cars currently in service,” said William A. Furman, Greenbrier’s Chairman and CEO.

It also had a product ready to match that stance. Greenbrier promoted its “Tank Car of the Future,” designed to move crude, ethanol, and other flammables more safely in North America, and to serve other hazardous-materials traffic. The design emphasized a thicker 9/16-inch steel tank shell, more robust outlet protection, and jacketed shells with thermal protection—features intended to reduce punctures, limit releases, and slow the “pool fires” that can occur when contents escape and ignite.

Then the rules arrived, and they were consequential. The DOT-117 standard in the U.S. (TC-117 in Canada) codified what the market had been racing toward, adopting demanding requirements for non-pressurized tank cars: jacketed and thermally insulated shells of 9/16-inch steel, full-height half-inch-thick head shields, sturdier re-closeable pressure relief valves, and rollover protection for top fittings. For manufacturers and fleet owners, the technical spec was only half the story. The other half was the clock: regulators put a tight timeline on retrofitting or retiring the large installed base of DOT-111s and even the newer CPC-1232 cars built since 2011.

For Greenbrier, that created both friction and fuel. The company noted that nearly 1,000 Greenbrier-designed and built tank cars were already in Class 3 flammable-liquids service across North America, and that it had orders for more than 2,500 cars of the DOT-117/TC-117 design. Greenbrier argued that requirements like increased shell thickness, full-height head shields, minimum 11-gauge jackets, re-closeable pressure relief valves, and thermal protection would mitigate the consequences of accidents and ultimately improve public safety.

And crucially, the retrofit mandate didn’t just help builders—it powered the less glamorous part of the flywheel: repairs and services. Furman highlighted Greenbrier’s ability to capture that work through GBW Railcar Services (GBW), its 50/50 joint venture with Watco Companies LLC focused on railcar repair and retrofitting. GBW planned significant investments in shop capacity, and Greenbrier said it had commitments from leading tank car owners to perform thousands of retrofits in line with the rule.

Then, just as quickly as the boom had arrived, it cracked. In 2015–2016, crude prices collapsed from over $100 per barrel to below $30, and tank car demand fell hard. Orders cratered.

But this time, Greenbrier wasn’t living and dying on one product category. The lessons from 2009 were still fresh, and the company was now supported by a broader mix—intermodal, covered hoppers, automotive equipment—and a leasing platform that helped steady the business when new-build demand turned volatile again.

The ARI Acquisition: Consolidating for Scale (2019)

By 2019, Greenbrier was ready to place its biggest bet yet—an acquisition that didn’t just add capacity, but rewired the competitive map in North American railcar manufacturing.

That year, Greenbrier announced an agreement to acquire the manufacturing business of American Railcar Industries (ARI) from ITE Management LP in a deal valued at $400 million, after adjustments tied to net tax benefits to Greenbrier valued at $30 million. The gross purchase price for the manufacturing business was $430 million.

The logic wasn’t subtle. This would consolidate the second- and third-largest players in the North American railcar market, creating the largest company by North American industry backlog. It was also a direct answer to a nagging worry: that Greenbrier might be losing share to ARI, and with it the economies of scale that make this business work when the cycle turns ugly. This was Greenbrier choosing offense—locking in scale before the market could force its hand.

The acquisition closed on July 26, 2019, largely on the terms agreed to in April. Greenbrier planned to fold the operations into its North American business model, both on the factory floor and in how it went to market. The company’s U.S. workforce totaled about 4,000 at the time, including nearly 1,600 U.S. employees coming over from ARI.

On the ground, the deal added two railcar manufacturing facilities in Paragould and Marmaduke, Arkansas. It also brought five additional operations that supplied components and parts—hopper car outlets, tank car valves, axles, castings, and railcar running boards, among other products that quietly matter when you’re trying to control quality, costs, and delivery schedules.

There was also a strategic fit in how the two companies made money. Greenbrier had built its reputation on high-volume production of standardized intermodal container cars. ARI, by contrast, was known for efficiently handling smaller production runs of specialty cars. Greenbrier had historically sold heavily to railroads and lessors; ARI had strength with large shippers that owned their own fleets.

William A. Furman, Chairman and CEO, framed it as a pivotal moment: “Acquiring the manufacturing operations of ARI is a major milestone for Greenbrier. The transaction advances three of our strategic goals: strengthening our presence in the

Going Global: Europe and Beyond (2016–2024)

While Greenbrier was locking down scale in North America, it was also trying to pull off something harder: build a true European platform. The opportunity looked obvious—an aging fleet, fragmented operators, and a market that seemed ready for a scaled, end-to-end player. The execution, as it turned out, would be anything but simple.

The big move came through a combination with Astra Rail Management GmbH. Greenbrier and Astra announced plans to form a new company, Greenbrier-Astra Rail, combining Greenbrier’s European operations—headquartered in Świdnica, Poland—with Astra’s footprint in Germany and Arad, Romania. The pitch was straightforward: a Europe-based freight railcar manufacturing, engineering, and repair business with enough scale to serve customers more efficiently, led by an experienced management team drawn from both companies.

Greenbrier’s majority stake didn’t come for free. As partial consideration, it agreed to pay Astra Rail €30 million at closing and another €30 million twelve months later. In 2017, Greenbrier acquired a 75% stake in AstraRail Industries for €60 million, roughly $64 million at the exchange rate cited at the time—an acquisition that became a cornerstone in what Greenbrier would call Greenbrier Europe.

The transaction closed on June 1, 2017. The combined enterprise brought together manufacturing and services across Poland and Romania, with headquarters in the Netherlands. At the time, Greenbrier-Astra Rail had nearly 4,000 employees and six production facilities across Europe.

The backdrop helped the thesis. Western Europe’s railcar fleet was getting old, with an average age around 25 years. Replacement demand, paired with expectations of European growth and the pull from nearby emerging markets, was positioned as the tailwind that could make the platform work.

Then came another layer: Türkiye. In 2018, Greenbrier completed an agreement between Turkish railcar manufacturer and maintenance and parts services provider Rayvag Vagon Sanayi ve Ticaret A.S and Greenbrier’s European subsidiary, Greenbrier AstraRail, to take a 68% ownership stake in Rayvag.

Over time, the European organization consolidated under the Greenbrier Europe banner, overseeing operations across Świdnica, Arad, and Adana. The vision mirrored Greenbrier’s playbook elsewhere: engineering, manufacturing, leasing solutions, and maintenance services wrapped into one integrated offering.

But Europe demanded constant adjustment. Greenbrier Europe undertook ongoing optimization, including the decision to shut down its Arad facility and shift production to other Romanian sites after reviewing the European market. The message was clear: the market dynamics were changing, and Greenbrier was retooling its European footprint toward modernization and sustainable growth—even when that meant closing a historic production site.

The Tekorius Era: Leadership Transition and Strategic Continuity (2022–Present)

After four decades with William Furman at the helm, Greenbrier faced one of those rare moments that can quietly define a company’s next decade: the leadership handoff. On March 1, 2022, the Board appointed Lorie Tekorius—then President and Chief Operating Officer—as Greenbrier’s CEO and President.

Tekorius, 54, wasn’t an outsider brought in to “shake things up.” She had been inside Greenbrier since 1995, building her career across roles of increasing responsibility. And in an industry where customers buy reliability as much as they buy equipment, that continuity matters.

“It has been a privilege to devote the bulk of my career to Greenbrier, growing and learning every day,” Tekorius said. “I am truly honored and humbled to follow Bill as only the second CEO in Greenbrier's history. I am confident that working collaboratively with our senior management team, we will meet the high expectations of all our stakeholders.”

Furman, for his part, made the endorsement as much about culture as performance: “Lorie's contributions to Greenbrier are outstanding and worthy of her new role. She has excelled in assignments of increasing responsibility throughout her long career with Greenbrier. Lorie epitomizes the Company's values of respect for humanity, integrity, and the interests of all stakeholders… The Board of Directors and I are confident her tenure and leadership will drive high impact outcomes.”

Under Tekorius, the strategy didn’t swing wildly—it tightened. Greenbrier rolled out a new business operations structure to support its “Better Together” strategy, first unveiled at its April 2023 Investor Day. The goal was straightforward: streamline decision-making, share best practices across the organization, improve customer experience, and translate operational consistency into better returns.

The company also made the org chart match how Greenbrier actually runs: two geographies, The Americas and Europe. Brian Comstock, a 26-year Greenbrier veteran with more than four decades of railway industry experience, took responsibility for operations across The Americas, including the United States, Mexico, Canada, and Brazil. William Glenn, with more than 20 years at Greenbrier, assumed responsibility for European operations. The Board appointed Comstock as Executive Vice President & President, The Americas, and Glenn as Senior Vice President & President, Europe.

And the numbers suggested the machine was working. In the first fiscal quarter ended November 30, 2024, Greenbrier reported net earnings of $55 million, or $1.72 per diluted share, on revenue of $876 million. The company generated EBITDA of $145 million and reported operating margin of $112 million.

The leasing flywheel kept turning, too: Greenbrier grew its lease fleet by about 1,200 units to roughly 16,700 units and maintained lease fleet utilization near 99%.

On the manufacturing side, quarterly new railcar orders totaled about 3,800 units, with deliveries of roughly 6,000 units, ending the quarter with a backlog of about 23,400 units valued at an estimated $3.0 billion.

Greenbrier also declared a quarterly dividend of $0.30 per share, payable on February 19, 2025 to shareholders of record as of January 29, 2025—its 43rd consecutive quarterly dividend.

The Business Model Deep Dive: Three Engines Working Together

Greenbrier’s edge isn’t that it’s the best at any single thing. It’s that it stitched three businesses together—each with different strengths, different cycles, and different ways of making money—and made them reinforce each other.

Engine 1: Manufacturing. This is the headline business and still the biggest revenue driver. It’s also the most exposed to the cycle. Over the past five years, U.S. railcar manufacturing has been reshaped by consolidation, technology upgrades, and a supply chain that had to be rebuilt in real time. Across the industry, the playbook has been clear: close underutilized plants, modernize the ones that remain, and in some cases shift production to Mexico to lower costs and stay competitive.

The tradeoff is baked in. Manufacturing throws off a lot of revenue, but margins tend to be thinner—typically in the mid-single digits for the industry. The advantage comes from scale, engineering know-how, and long-term customer relationships that are hard to win and even harder to replace.

Engine 2: Leasing & Management Services. This is the stabilizer—and the strategic crown jewel of Greenbrier’s post-crisis transformation. Greenbrier owned a lease fleet of about 16,700 railcars, most of them built by Greenbrier itself. Leasing turns railcars from one-time sales into long-lived, recurring cash flow, with stronger margins and more resilience when new orders slow down.

It also changes how Greenbrier goes to market. Leasing sits alongside direct sales, partnerships with operating lessors, and originating leases for syndication partners. There’s a real short-term cost: when Greenbrier places cars into its own lease fleet, it can mean deferring revenue recognition versus selling the car outright, which pressures reported manufacturing revenue and margin. The payoff is durability—recurring, higher-margin, tax-advantaged cash flows that smooth the cycle.

Engine 3: Maintenance Services (Wheels, Repair & Parts). This is the quiet cash machine: the aftermarket work that keeps railcars running no matter what’s happening in new-build demand. In 2024, aftermarket distribution led the mix, driven by frequent maintenance cycles across a wide range of railcar fleets. Operators need parts quickly to keep cars out of the shop and on the network. That urgency—availability, speed, and service support—creates a steady, sticky stream of demand.

Put the three together and you get the flywheel. Manufacturing feeds the lease fleet with new cars. The lease fleet creates predictable maintenance and parts demand. And those service relationships deepen customer intimacy, which helps win the next manufacturing order. It’s a system—one that’s hard for a pure-play manufacturer or a pure-play lessor to replicate.

Industry Structure & Competitive Dynamics

The North American railcar industry is a concentrated oligopoly. A small handful of companies set the pace on both manufacturing and leasing, and everyone else fights for scraps when the cycle turns.

In U.S. railcar manufacturing, the biggest names include The Greenbrier Companies, Siemens AG, and Trinity Industries. Greenbrier has often held the largest share of the manufacturing market.

Greenbrier expected North American demand of about 37,800 railcars in 2024, and said it held roughly 39% of the overall order portfolio among U.S. railcar manufacturers. Trinity led with about 50%.

Trinity remains Greenbrier’s principal competitor in North America. In fiscal year 2024, Trinity accounted for about 41% of industry railcar deliveries—an illustration of just how much production capacity sits with the top tier. Trinity is also a major lessor in its own right. As of Q1 2025, its lease fleet utilization was 96.8%, and it reported a Future Lease Rate Differential (FLRD) of 17.9%, reflecting favorable lease rate trends. By December 31, 2024, Trinity’s wholly owned lease portfolio included 109,635 railcars, and it managed another 34,230 railcars for investors.

But leasing is its own battlefield, with a different set of heavyweights. GATX Corporation is one of the largest: a pure-play railcar lessor with fleets across North America, Europe, and Asia. It’s headquartered in Chicago, and it also owns, jointly with Rolls-Royce Limited, one of the largest aircraft spare engine lease portfolios. As of December 31, 2020, GATX owned 148,939 railcars and 645 locomotives, with its rail fleet weighted toward tank cars and freight cars. In 2020, it primarily served the petroleum industry (29% of revenue), chemical industry (22%), food (11%), mining (10%), and transportation (20%).

Here’s the key strategic contrast: GATX doesn’t manufacture. That makes it almost the mirror image of Greenbrier’s integrated model. And it creates a telling competitive dynamic—GATX has to buy cars from manufacturers like Greenbrier and Trinity, while those manufacturers get a front-row seat into leasing demand and market pricing through the lessors’ buying behavior.

The reason the same names keep showing up is simple: the barriers to entry are enormous. Railcar manufacturing takes heavy capital, specialized engineering, certifications, and a reputation you only earn by delivering consistently over years. In practice, scale and credibility aren’t just advantages in this market—they’re the price of admission.

Strategic Analysis: Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW. This is one of those markets where the barriers aren’t theoretical—they’re physical. A new entrant doesn’t just need a good idea; it needs an enormous checkbook, years of engineering validation and certifications, and the kind of customer trust that only gets earned one delivery at a time. With a handful of scaled incumbents already dominating U.S. railcar manufacturing, breaking in is brutally hard.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE. On the biggest input—steel—Greenbrier is largely a price-taker because steel behaves like a commodity. But the more specialized the part, the more power the supplier has: wheels, bearings, couplers, and other components often come from a relatively small set of qualified providers. Greenbrier has pushed back on that leverage the way you’d expect from an integrated player—by pulling more of the component ecosystem closer through vertical integration, including capabilities added through the ARI acquisition.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH. The customers are huge, sophisticated, and they buy in bulk. Class I railroads and major leasing companies can absolutely squeeze pricing—especially when the cycle turns down and manufacturers are fighting over a shrinking pool of orders. The counterweight is relationship and switching friction: once a fleet is engineered around a design, and once maintenance, parts, and service routines are established, it’s not trivial to rip and replace.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW. For long-haul, heavy, bulk freight, rail doesn’t really have a true substitute. Trucking can win on flexibility, but it can’t match rail’s economics for those lanes and cargo types. And intermodal growth tends to strengthen rail’s role in the supply chain rather than undermine it.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE-HIGH. This is an oligopoly, but it’s not a cozy one. The big players—especially Greenbrier and Trinity—compete hard on price, quality, and delivery reliability. In good times, capacity is full and discipline is easier. In downturns, the gloves come off, and the fight is for whatever orders are still left.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: STRONG. Size matters here—on purchasing, on overhead absorption, on engineering, and on resilience. Being one of the largest manufacturers gives Greenbrier cost advantages and staying power that smaller competitors often don’t have when the market drops.

Network Effects: WEAK. Manufacturing itself doesn’t compound through classic network effects. The closest analog is the installed base: more cars out in the world can translate into more opportunities in maintenance services and parts.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE. Greenbrier’s integrated manufacturing plus leasing model is hard to mirror from either direction. Pure manufacturers usually can’t justify tying up that much capital in a lease fleet. Pure lessors generally don’t want the operational risk of running factories. That “both/and” positioning is a real differentiator.

Switching Costs: MODERATE. Railcars are engineered products embedded in customer operations. Once a shipper or lessor standardizes around a design—and once service relationships and parts compatibility get built in—switching becomes painful and expensive, even if it’s not impossible.

Branding: WEAK-MODERATE. This isn’t a consumer brand game. Still, reputation is currency. In a relationship-driven, high-stakes industrial market, being known for quality and delivery matters.

Cornered Resource: WEAK. Greenbrier doesn’t have a single piece of IP that locks the market. What it does have is hard-to-recreate human capital: skilled labor, process knowledge, and long-standing customer relationships.

Process Power: MODERATE-STRONG. Decades of operating know-how—design-to-delivery integration, manufacturing discipline, and the ability to execute consistently—compound over time. Competitors can copy a product. Replicating a well-run system takes much longer.

Overall Assessment: Greenbrier’s moat is strongest in Scale Economies and Counter-Positioning. The integrated model is a genuine advantage, especially when cycles turn. But the core truth of railcars still holds: this is a cyclical business, and no amount of strategy fully removes that exposure.

Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Considerations

The Bull Case

Structural tailwinds favor rail. As reshoring and nearshoring pull more manufacturing closer to home, more of the supply chain stays on the continent—and that tends to be good for rail volumes. Rail also keeps its core economic advantage: for bulk freight over distance, it’s hard to beat on cost. And on emissions, it’s materially more fuel-efficient than trucking, which matters more as shippers push to lower their transportation footprint.

Leasing transformation creates value. The post-crisis shift toward leasing and management services is the closest thing Greenbrier has to an “anti-cycle” hedge. The company grew its lease fleet by about 1,200 units to roughly 16,700 railcars and kept utilization near 99%. That matters because a highly utilized lease fleet is exactly what manufacturing is not: recurring, predictable cash flow that can keep the machine steady when new orders get choppy.

Strong backlog provides visibility. Greenbrier’s backlog sits around 26,700 units, valued at an estimated $3.4 billion. At current delivery rates, that’s close to a couple of years of production already spoken for—a built-in runway that helps investors underwrite the near-term manufacturing engine.

Oligopoly structure protects margins. This isn’t a market with dozens of factories constantly undercutting each other. A small number of scaled players dominate. That doesn’t eliminate competition, but it does tend to make pricing behavior more rational than in fragmented industries—especially when the leaders are capacity-disciplined.

ESG tailwinds. Rail’s carbon efficiency and role in supply-chain decarbonization are increasingly part of the buying conversation. When customers care about emissions, rail looks better—and companies tied to rail’s growth look better too.

The Bear Case

Cyclicality is inherent. Greenbrier can smooth the cycle, but it can’t repeal it. Manufacturing demand in this industry can still swing dramatically from peak to trough, and the company will always have some exposure to that whiplash.

Customer concentration risk. The buyers are big and sophisticated—Class I railroads and major lessors—and they know how to negotiate. When demand softens, their leverage grows, and pricing pressure can follow.

Capital intensity. This is a business that constantly asks for capital. Factories require ongoing investment, and leasing requires even more: every railcar you keep on your own balance sheet is money tied up for years. Over time, scaling a meaningful fleet means deploying very large sums, and that raises the stakes on asset values, utilization, and financing conditions.

International execution risk. Europe has been a work in progress, and not a painless one. Greenbrier Europe has required restructuring, including shutting down its Arad facility and shifting production to other Romanian sites after reviewing the European market. Global footprints can create opportunity, but they also multiply complexity.

Technology disruption. Autonomous trucking is likely farther out than the hype suggests, but the broader point still stands: freight patterns can change. Any structural shift that changes what moves, where it moves, and how it moves can eventually reach rail—and railcar demand.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch

For investors monitoring Greenbrier, three metrics do a lot of the diagnostic work:

-

Backlog value and trend. Backlog is the clearest window into forward manufacturing revenue. The absolute level matters—but the direction matters more.

-

Lease fleet utilization. Utilization near 99% signals strong demand for leased equipment. A sustained move below the mid-90s would be a meaningful warning sign.

-

Aggregate gross margin. Greenbrier finished fiscal 2024 with what it called a great fourth quarter, delivering aggregate gross margin near 16% as efficiency initiatives took hold over the prior 18 months. This is the “all-in” profitability read across the portfolio—and a good reality check on whether the integrated flywheel is actually translating into better economics.

Key Lessons for Founders & Investors

Surviving cyclicality through diversification. 2009 made the flaw in a pure manufacturing model impossible to ignore: when orders evaporate, so does your margin of safety. Greenbrier’s pivot into leasing and management services didn’t just help it recover—it gave the company a way to keep earning when the cycle turned, and helped underpin long-term shareholder value.

Vertical integration as competitive advantage. Greenbrier didn’t bolt on businesses for the sake of empire-building. It built a connected system: manufacturing supplies the lease fleet, the lease fleet drives service and parts demand, and the aftermarket relationships strengthen the next manufacturing win. The power isn’t any one segment—it’s how they compound together.

Capital allocation as strategy. The biggest strategic move wasn’t a new product or a new plant. It was deciding to take cash from the factory floor and turn it into owned earning assets by expanding the lease fleet. That choice reshaped the company’s earnings mix and, over time, how the market could value the business.

Patient capital wins in cyclical industries. Railcar demand doesn’t move in gentle waves—it snaps from boom to bust. Greenbrier made it through multiple cycles while weaker players fell away. In tight, capital-heavy industries, staying power and scale often matter more than chasing growth at any price.

The power of “boring” businesses. Railcars aren’t glamorous, but they sit underneath enormous, durable flows of commerce. That combination—essential infrastructure, long-lived assets, and limited disruption risk—can be a surprisingly good foundation for compounding, as long as the operator is built to survive the troughs.

Relationship businesses require patience. With railcars lasting decades, customer relationships tend to last decades too. This is a trust business: delivery reliability, product quality, and service support don’t just win one order—they win the next ten years of them.

Counter-cyclical thinking. The best time to expand a lease fleet isn’t when factories are running flat out. It’s when manufacturing is slow, assets are cheaper, and competitors are retreating. Greenbrier learned to deploy capital when the cycle made others cautious—and that mindset became a strategic advantage.

Epilogue: The Road Ahead

Greenbrier heads into 2026 from a position of strength—and, just as importantly, from a place of clarity about what it’s trying to become.

“While we observe demand easing slightly for certain railcar types and in some markets, we are affirming our full-year guidance and expect demand to increase as 2025 progresses,” Tekorius said. “We are dedicated to executing our strategy to deliver strong performance, reduced cyclicality, and enhanced long-term shareholder value. Our results demonstrate our ability to thrive even in less than optimal business conditions. With a leading market position, a healthy backlog of new railcar orders, increasing predictability in growing areas of our business, and a continued focus on operational efficiencies, we anticipate sustainable results across various market conditions.”

That’s the whole playbook in one quote: don’t pretend the cycle is gone—build a company that can perform anyway.

The priorities are straightforward. Keep building the lease fleet, with the aim of doubling recurring revenue by 2028. Keep tuning the manufacturing footprint so it’s efficient and flexible instead of bloated and fragile. And keep defending the top of the market through engineering execution and service—because in a relationship business, reputation compounds.

In fiscal 2025, the lease fleet expanded about 10% and stayed about 98% utilized. Greenbrier also paid its 46th consecutive quarterly dividend on December 3, 2025.

And that brings us to the only question that really matters: can Greenbrier keep compounding through the next crisis?

The record says it can. But the industry guarantees nothing. The leasing transformation has meaningfully de-risked the model, yet manufacturing will always carry some exposure to demand swings. Greenbrier’s bet—its defining bet since 2009—is that integration, recurring revenue, and operational discipline can turn a boom-and-bust business into something that endures.

For long-term investors who can live with cyclicality and value the power of vertical integration, Greenbrier isn’t just a railcar company. It’s a case study in reinvention: a business that got pushed to the brink, rebuilt itself around durability, and kept finding ways to move what matters across North America’s rails.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music