Gap Inc.: The Rise, Fall, and Reinvention of an American Fashion Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

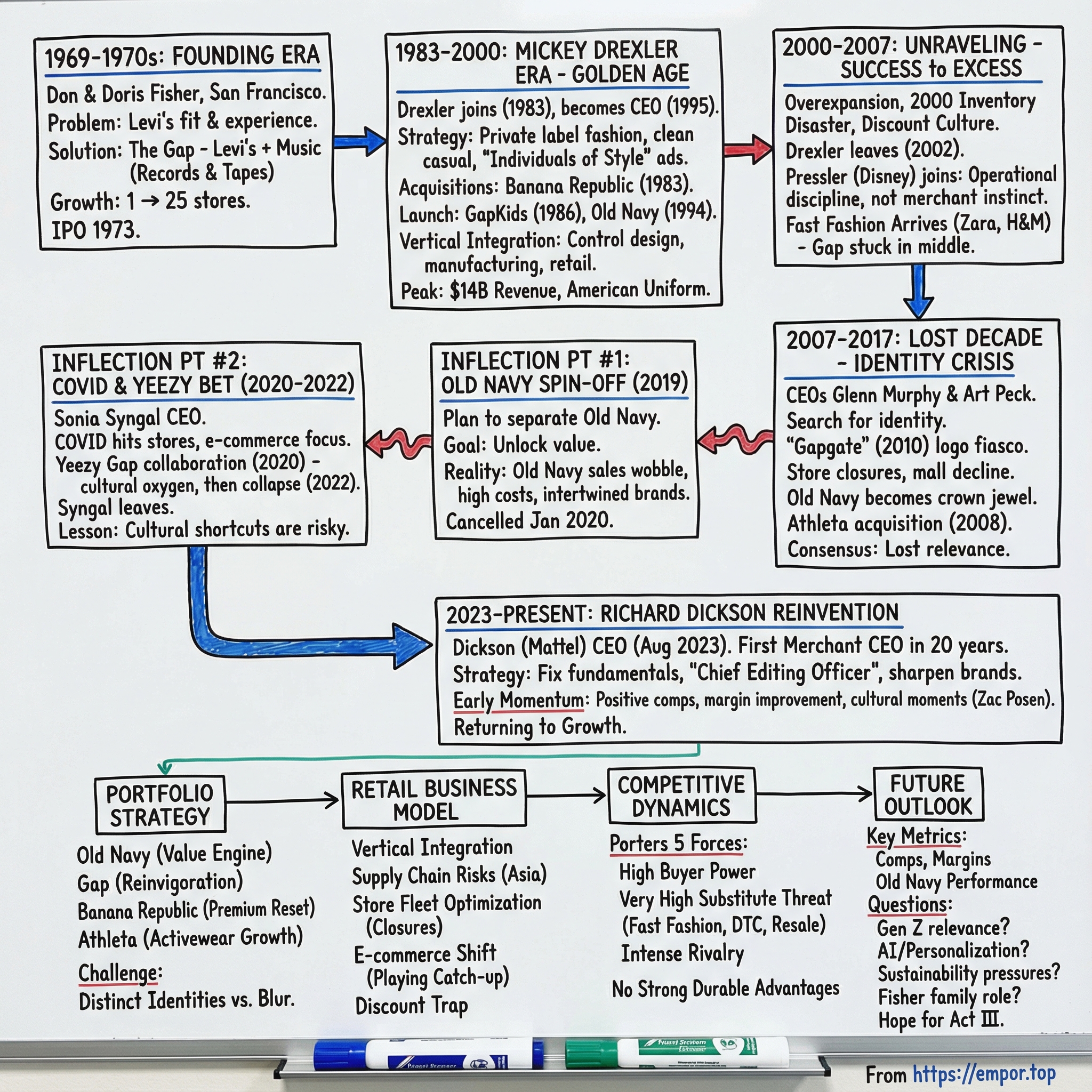

In August 1969, a frustrated San Francisco real estate developer named Don Fisher walked into a department store looking for a pair of jeans that actually fit. He walked out empty-handed—and angry. It was the kind of small, everyday friction most people shrug off. Don didn’t. He saw a problem hiding in plain sight: young customers wanted Levi’s, but the shopping experience was miserable.

Days later, that irritation turned into action. On August 21, 1969, Don and his wife, Doris, founded Gap after a frustrating attempt to exchange a pair of jeans that didn’t fit. What started as a simple fix for a simple problem would become one of the most influential apparel stories in modern America.

Today, Gap Inc. is the largest specialty apparel company in the U.S. Fiscal year 2024 net sales were $15.1 billion. It operates four distinct brands—Gap, Old Navy, Banana Republic, and Athleta—each aimed at a different customer, a different price point, and a different moment in life. And under CEO Richard Dickson, the company has shown real signs of momentum again: “For the full year 2024, Gap Inc. delivered positive comps in all four quarters, achieved one of the highest gross margins in the last 20 years and meaningfully increased operating margin versus the prior year.”

But those results are the end of the story, not the beginning. To understand how Gap got here, you have to go back through the messy middle: two decades of identity crises, false starts, and turnaround plans that didn’t turn—plus the rising force that broke a lot of mall brands at once: fast fashion. So the central question is simple, and brutal: how did the company that once defined American casual wear lose its way, and can it actually find its way back?

Because this isn’t just a story about one retailer. It’s a case study in what happens when success hardens into habit—when a brand portfolio turns from advantage to trap, and when cultural relevance expires faster than your supply chain can react. Gap’s arc shows why some companies stay iconic, while others become background noise—and what it really takes to come back.

II. The Founding Story: Levi's, Music, and a Gap in the Market (1969–1970s)

Picture San Francisco in 1969: counterculture at full volume, young people rejecting the establishment, and denim turning into the uniform of a generation. Don Fisher didn’t see chaos. He saw demand.

Fisher was a real estate broker, not a retail lifer. But one maddening shopping trip changed his trajectory. He was trying to buy Levi’s that fit—and then exchange the ones that didn’t. What he found instead was a system designed to make a simple purchase feel like a chore: scattered inventory, missing sizes, indifferent service, and a shopping experience that treated the very customer who wanted the product like an inconvenience.

His takeaway was almost insultingly straightforward: people wanted jeans. Retailers were making it hard to buy them.

So Fisher spotted the gap—literally—between what young consumers wanted and what stores were offering. If department stores were going to keep mishandling the basics, there was room for a specialist: a store that carried the popular thing, in every size, organized sensibly, with returns that didn’t require a negotiation.

On August 21, 1969, Don co-founded The Gap with his wife, Doris, opening the first store at 1950 Ocean Avenue in San Francisco’s Ingleside neighborhood near City College. The formula was tight and intentional: Levi’s jeans in every available size, cut, and style—plus record albums to pull in the youth crowd and signal exactly who the store was for.

Even the name came loaded with meaning. Doris Fisher suggested “Gap,” a nod to the “generation gap” everyone talked about then. It wasn’t subtle, and it didn’t need to be. The store was built to serve the kids who were driving culture—and being underserved by the places that sold their clothes.

The supply arrangement made the concept work. Fisher committed to selling only Levi’s, in every style and size, with the product grouped by size so customers could actually find what they needed. Levi’s, for its part, kept The Gap stocked with overnight replenishment from its San Jose warehouse. And a Levi’s executive, Bud Robinson, offered to cover half of The Gap’s radio advertising upfront—structured in a way that avoided antitrust trouble by making the same marketing package available to any store willing to sell nothing but Levi’s.

This wasn’t a one-person story, either. Don and Doris built the business side by side from the start, investing equally and working in that first Ocean Avenue store themselves. Doris wasn’t a symbolic co-founder; she shaped the merchandising sensibility early, and the partnership showed in how focused and customer-friendly the whole experience felt.

The music wasn’t a gimmick. It was traffic—teenagers came for records and tapes, and while they were there, they bought jeans. And it worked. Within a few years, The Gap proved it could travel. By 1972, it had grown from one store to 25 locations.

Success came fast enough that Wall Street got interested. The company filed for an IPO in 1973, then went public in 1976, giving the Fishers the capital to expand aggressively.

But scale changes the game. And the next leap—the one that would turn The Gap from a clever retail concept into a true fashion powerhouse—would require a kind of merchandising instinct the Fishers hadn’t yet brought in.

III. The Mickey Drexler Era: Building the American Brand (1983–2000)

By 1983, Gap was doing fine. It was a specialty retailer with roughly $80 million in sales—real money, but not a movement. Nineteen years later, when Mickey Drexler left, Gap had become a sprawling apparel empire with more than 4,000 stores and around $14 billion in annual revenue. More importantly, it had turned “basic” into a national style.

To understand Gap’s golden age, you have to understand Drexler.

Millard “Mickey” Drexler didn’t come from fashion glamour. He grew up as an only child in a Jewish neighborhood in the Bronx. His mother died when he was 16. The family apartment on Allerton Avenue was so cramped he slept on a makeshift bed in the hallway. That kind of upbringing doesn’t make you precious. It makes you relentless—especially about details—and Drexler carried that intensity into retail with an almost unnerving instinct for what customers would buy.

Before Gap, he learned the business inside big department stores—Abraham & Straus, then Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s. In 1980, he got his first CEO job at Ann Taylor, where he’s credited with turning the brand into a go-to destination for working women in just three years.

Don Fisher took notice. In 1983, he recruited Drexler to come to Gap and oversee the company’s portfolio of brands—starting with fixing the core business.

Drexler arrived as Donald Fisher’s deputy, became president of the Gap division, and quickly started pulling levers that most retailers were too timid to touch. He brought in new designers. He tightened quality control. He refreshed stores so they felt modern and consistent. And in 1986, he launched GapKids—an immediate hit that extended the brand from “what you wear” into “what your family wears.”

But the real masterstroke was strategic: Drexler helped push Gap from being a Levi’s reseller into being a private-label fashion company. Gap leaned hard into clean, versatile casualwear—tees, chinos, denim—simple pieces with just enough fit and finish to feel like an upgrade, without the high-fashion attitude. It was the birth of a very specific kind of American promise: you can look put-together in basics, and you don’t need a designer label to do it.

Marketing turned that promise into culture. Gap’s “Individuals of Style” campaigns put celebrities in straightforward, recognizable Gap clothes. Sharon Stone. Madonna. Big names, minimal styling. The message landed because it felt democratic: the clothes weren’t the costume. You were.

Over time, Drexler’s rise inside the company matched Gap’s rise in the culture. He started as president in 1983 and, in 1995, was promoted to CEO. Gap wasn’t just growing—it was defining what “normal” looked like in America.

Then came one of the smartest defensive moves in modern retail: Old Navy.

In the early 1990s, Dayton-Hudson (the parent of Target) explored launching a cheaper Gap-like concept called Everyday Hero. Drexler saw the threat immediately. Instead of waiting to be undercut, Gap struck first—opening Gap Warehouse in existing outlet locations in 1993. On March 11, 1994, Gap Warehouse became Old Navy Clothing Co., with its own name, its own vibe, and one job: win the value customer before someone else did.

Even the name had a kind of scrappy charm. Other options—Monorail and Forklift—were floated and rejected. “Old Navy” won out after Drexler saw the words on a building during a trip to Paris.

The timing was perfect. Gap was feeling pressure from both ends: higher-end brands pulling fashion-forward shoppers upmarket, and mass merchandisers dragging prices down. Old Navy gave the company a clean way to compete on price without torching the Gap brand. And it exploded—growing to hundreds of stores in under three years. By 1997, Old Navy became the first retail brand to hit $1 billion in annual sales within just four years of launching.

Meanwhile, Gap was also building out the top end of the portfolio. It had acquired Banana Republic back in 1983—a small, safari-themed retailer—and reshaped it in the late 1980s into an upscale clothing brand. Suddenly, Gap had a true three-tier machine: Banana Republic upmarket, Gap in the middle, Old Navy at value.

By 1998, Fortune called Drexler “possibly the most influential individual in the world of American fashion.” And it didn’t feel like hype. Around 1999 and 2000, Gap was at its peak. The company was generating nearly $14 billion in revenue, and khakis and pocket tees had become America’s unofficial uniform.

Underneath the cultural moment was a business advantage competitors envied: Gap’s vertical integration. The company controlled design, manufacturing, distribution, and retail—giving it speed, consistency, and margins that made the model look unbeatable.

And that’s the thing about peaks. From the top, it’s hard to see what’s about to break. But for Gap, the very success that made it feel untouchable was about to become a trap.

IV. The Unraveling: When Success Becomes Excess (2000–2007)

The turn of the millennium didn’t just mark a new decade for Gap. It marked the end of the illusion that the machine could run on autopilot forever. The same playbook that had built an empire—scale, consistency, and a tightly controlled pipeline—started to work against them the moment the customer moved on.

A softer economy and intensifying competition helped trigger a multi-year slump, but Gap’s problems weren’t just cyclical. The company had expanded so aggressively that stores were everywhere, and yet the brand was somehow harder to find in culture. It had saturated the market at the exact moment it began losing its feel for what people actually wanted to wear.

Then came the mess that retail people still talk about: the 2000 inventory disaster. Gap made big bets on specific looks, and customers shrugged. Stores clogged up with product that wouldn’t move. Markdowns followed, margins got crushed, and—worse—shoppers got trained to wait for discounts. Once you teach your customer that full price is optional, it’s a hard lesson to un-teach.

By 2002, the tension snapped. On May 22, 2002, after a long sales slump, rising debt, and a management style that clashed with the Fisher family, Mickey Drexler was forced to announce his retirement. He remained CEO until September 26, 2002, when Paul Pressler was named his successor.

Drexler’s exit wasn’t just a leadership change. It was the end of an era. He’d overseen the brand’s transformation and then watched it stumble for 12 straight quarters of same-store sales declines. It landed personally. “I spent 18 years there building a company. I was hurt [by] the way it happened,” Drexler later said.

He even turned down a reported $2 million severance package, because accepting it would have locked him into a non-compete agreement. Instead, he went to J.Crew, where he’d engineer another turnaround—while Gap, without him, kept searching for its identity.

Pressler represented a hard pivot in philosophy. He came from Disney, not fashion. The pitch was operational discipline: close underperforming locations, clean up the balance sheet, pay down debt. And some of that happened. But the deeper problem was that Gap didn’t need a theme-park operator. It needed a merchant.

Pressler leaned heavily on market research and focus groups—exactly the opposite of Drexler’s gut-driven approach. The outcome was predictable: safer product, less energy, declining traffic, and a brand that felt increasingly irrelevant.

And while Gap was trying to spreadsheet its way back to cool, the industry was changing underneath it. Zara and H&M arrived in the U.S. with a different operating system: fast fashion. They could grab what was happening on runways and in street style, and get cheap versions into stores in a matter of weeks. Gap’s traditional design-to-shelf cycle—closer to half a year—couldn’t compete. Young shoppers who once defaulted to Gap discovered alternatives that felt current, fun, and in sync with the moment.

That “cheap chic” wave stranded Gap in the worst possible place: the middle. It wasn’t fast enough to win on freshness, not cheap enough to beat the value players (including its own Old Navy), and not special enough to justify trading up. The sweet spot that had made Gap a powerhouse was getting hollowed out.

By 2007, the company was essentially admitting what the market had already decided. Gap announced it would focus on finding a CEO with deep retail and merchandising experience—someone who understood apparel, the creative process, and could execute at scale while keeping financial discipline. In other words: it needed to get back what it had lost.

V. The Lost Decade: Searching for Identity (2007–2017)

That July, Gap named Glenn Murphy—previously the CEO of Canada’s Shoppers Drug Mart—as the new CEO of Gap Inc. The company also brought in new lead designers, hoping fresh creative blood could restore something Gap had been bleeding for years: a clear point of view.

Murphy did what he was hired to do. He brought operational discipline, tightened execution, and steadied the ship. But the core problem didn’t go away. The question hanging over the business was painfully simple: what did Gap actually stand for now? The brand that once defined American casual had turned into everyone’s fallback—perfectly fine, rarely beloved.

Nothing captured that better than what happened in October 2010. After sales slumped coming out of the 2008 financial crisis, Gap tried what should have been a routine brand refresh. Instead, it ignited a public meltdown that became known as “Gapgate.”

The old logo disappeared almost overnight. On October 6, 2010, Gap replaced its familiar mark with a new logo: a much smaller dark-blue box and the word “Gap” set in bold, black Helvetica. The redesign came from Laird and Partners, a well-known New York creative agency with a strong reputation in fashion branding. The effort was estimated to have cost around $100 million.

The reaction was immediate—and brutal. Customers and designers weren’t just unimpressed; they were offended by how abruptly it was done, with no lead-up and no broader story. The change didn’t seem to signal anything else happening inside the company. It felt like surface-level tinkering from a brand that couldn’t explain itself.

Within 24 hours, a single online blog racked up roughly 2,000 negative comments. A protesting Twitter account, @GapLogo, drew 5,000 followers. A “Make your own Gap logo” site went viral and collected nearly 14,000 parody redesigns.

Less than a week later, Gap folded. On October 12, 2010, the company reverted to the old 1990 logo. A spokesperson who had initially described the new look as “modern, sexy and cool” reversed course, saying, “we’ve learned just how much energy there is around our brand.” The speed of the retreat didn’t just signal a failed rebrand. It signaled a company that didn’t know what it was trying to be.

The logo fiasco became a business-school case study worldwide—not because Helvetica was inherently wrong, but because the episode revealed something bigger. The failure wasn’t really design. It was brand leadership. Gap believed it could change an emotional symbol without a strategy, without dialogue, and without earning it.

In 2015, Art Peck took over as CEO, inheriting the same unsolved puzzle. He pushed digital transformation and tried to modernize how Gap operated. But the results stayed frustratingly hard to find. (Peck ultimately stepped down in November, ending a tenure defined by big ambitions and stubbornly mixed outcomes.)

Meanwhile, inside the portfolio, one brand kept doing what the rest couldn’t: Old Navy. While the Gap brand struggled to justify its price and positioning, Old Navy’s value proposition clicked with budget-conscious families. It became the crown jewel—eventually generating almost half of Gap Inc.’s $16.6 billion in 2018—and investors increasingly treated it like the real business, with the rest of the company as baggage.

There was at least one genuinely forward-looking move in this stretch: Gap acquired Athleta in 2008, buying its way into activewear just as Lululemon and the broader category were exploding. In a decade full of defensive maneuvers, Athleta looked like an offensive bet.

But the environment kept getting harsher. Store closures began in earnest. In October 2011, Gap Inc. announced plans to close 189 U.S. stores—nearly 21 percent—by the end of 2013. Mall traffic was declining, e-commerce was rising, and consumer tastes were splintering. The “specialty retail apocalypse” didn’t just hit Gap. It hit the part of America Gap had been built on.

And from the outside looking in, Mickey Drexler could name the disease in one breath: “They are being affected, I think, by what every other big apparel chain is being affected by — too much stores, too much merchandising, too much sales, tons of competition,” he said. “You have got to have a niche, a point of view. What I would do is what I did the first day [there] in 1983. I went to every style in the company, throwing out, keeping in, and renaming everything.”

For investors, the message hardened into a grim consensus: Gap had lost its identity and couldn’t find it again. Each turnaround plan promised a new start. Each new initiative fizzled. The company that once defined American fashion started to feel like it might be permanently stuck—present everywhere, resonant nowhere.

VI. Inflection Point #1: The Old Navy Spin-Off That Wasn't (2019)

In February 2019, Gap finally said the quiet part out loud: the portfolio wasn’t working. The company announced it would split into two separate public companies, spinning off Old Navy as its own independent business. On February 28, 2019, Gap Inc. said Old Navy would separate from the rest of the company.

On paper, it sounded like the cleanest move Gap had made in years. Investors certainly treated it that way. When the spin-off plan was announced, Gap’s shares jumped 19%—less a celebration of Gap’s strategy than a sign of how desperate the market was for something that might stop the bleeding.

The story was easy to sell. Old Navy would be a standalone value powerhouse—an roughly $8 billion business—with a clear lane, a simple customer promise, and the kind of scale that should travel. The remaining company would be smaller—around $9 billion a year—housing Gap, Banana Republic, Athleta, and the rest, with the freedom to attempt a more focused turnaround without Old Navy’s shadow. Old Navy’s brand chief, Sonia Syngal, even framed the ambition plainly: push the brand to “$10 billion and beyond.”

The pitch wasn’t just about splitting up. It was about unlocking value. Old Navy could “soar” without being dragged down by struggling siblings, and the “new Gap” could rebuild without constantly being compared to the one part of the house still on fire—in a good way.

Then reality intruded. Old Navy began to wobble. Sales softened in the quarters that followed, and the competitive set looked uglier by the month: H&M, TJ Maxx, Target—big, aggressive players all fighting for the same value-minded customer.

By November 2019, the plot got even messier. Art Peck, the CEO who had announced the separation, was out. Gap said Peck was stepping down after holding the role since 2015, and Robert Fisher—the son of founders Donald and Doris Fisher—stepped in on an interim basis. The spin-off was supposed to be a crisp financial separation; instead it started to look like a company in the middle of another leadership scramble.

Two months later, the whole plan was dead. On January 16, 2020, Gap Inc. announced it was calling off the separation.

Robert Fisher laid out the rationale in a statement: “The plan to separate was rooted in our commitment to value creation from our portfolio of iconic brands. While the objectives of the separation remain relevant, our board of directors has concluded that the cost and complexity of splitting into two companies, combined with softer business performance, limited our ability to create appropriate value.”

In plain English: this was going to be expensive, complicated, and the business wasn’t strong enough to absorb the disruption. Gap had already warned investors the spin would carry a one-time expense of $400 million to $450 million, plus another $300 million to $350 million in capital costs over time. Paired with weaker sales, the separation started to feel less like a brand fix and more like costly financial engineering. Even Wall Street—usually happy to push for breakups—had begun clamoring for Gap to pull the plug.

The collapse of the spin-off exposed an uncomfortable truth. Old Navy might have been the crown jewel, but the company’s brands were more intertwined than anyone wanted to admit. And collectively, they weren’t performing strongly enough to fund the clean reset the strategy required.

VII. Inflection Point #2: COVID, Kanye, and the Yeezy Bet (2020–2022)

Sonia Syngal became CEO in March 2020—exactly as the world slammed shut. It was a whiplash moment for Gap Inc.: a new leader, fresh off her run reviving Old Navy, inheriting a fragile portfolio just as stores everywhere went dark. Syngal was widely seen as a potential savior, and she moved quickly to push the company back toward fashion and relevance. She worked to improve the supply chain, continued shutting underperforming stores, and made one huge, headline-grabbing swing: a long-term design partnership with Kanye West.

COVID initially punished Gap’s store-heavy model. But in the wreckage, a few trends broke in Gap’s favor. Athleisure exploded as millions worked from home, lifting Athleta. And e-commerce—long an area where Gap lagged—stopped being a strategic initiative and became survival. Gap didn’t get to modernize at its own pace anymore. It had to do it now.

The most audacious bet came in June 2020: Yeezy Gap (often styled as YEEZY GAP or YZY GAP), a collaboration between West’s Yeezy and Gap. The announcement alone jolted the market—Gap’s stock rose 36%—because it promised something the company had been starving for: cultural oxygen. Gap pitched the line as “modern, elevated basics for men, women and kids at accessible price points.” West and Gap agreed to a 10-year deal, with an option to renew after five years, and the structure included the ability for West to acquire up to 8.5 million Gap shares tied to sales performance. The first wave of product wouldn’t arrive until June 2021, but the signal was loud and clear: Gap was trying to buy its way back into the conversation.

West had been orbiting Gap for years. He’d worked at a Gap store as a teen, and in a 2015 interview he said he wanted to be “the Steve Jobs of the Gap.” A collaboration had even been in the works back in 2009, but it fell apart. West later blamed “the politics.”

When the product finally hit, the early data looked like a breakthrough. Gap later said the Yeezy Gap hoodie delivered the most online sales of a single item in one day in company history—and that about 70% of buyers were new customers.

But the partnership’s story quickly shifted from momentum to friction. Releases were irregular and unpredictable. In August 2022, West began airing grievances publicly, posting on Instagram about meetings being held without him, accusing Gap of copying his designs for Gap’s own product, and criticizing how the collaboration was being run. On September 12, he said in an interview that he wanted out: “It’s time for me to go it alone.”

Days later, West—who goes by Ye—said he’d terminated the contract between Yeezy and Gap. In a letter sent by his lawyer, Yeezy alleged Gap failed to meet obligations, including distributing products to stores and building dedicated YZY Gap store concepts. In comments to CNBC, Ye framed it as a broken dream: “It was always a dream of mine to be at the Gap and to bring the best product possible. Obviously there’s always struggles and back-and-forth when you’re trying to build something new and integrate teams.” He added that he wasn’t able to set the prices he wanted, didn’t approve of color selections, and felt the teams’ priorities weren’t aligned: “It was very frustrating. It was very disheartening, because I just put everything I had.”

Then came the part that made the business dispute irrelevant. After a series of antisemitic remarks from West, Gap’s hand was forced. On October 25, Gap said it would stop selling Yeezy Gap products, abandoning plans to offload remaining inventory after the contract ended.

Outside observers summed up what the whole saga exposed. “What is Gap? Who is it for? Over the last several years, they’ve been really struggling to find their way. I honestly cannot remember a time when I knew what Gap stood for,” said Deb Gabor, CEO and founder of Sol Marketing.

Syngal didn’t survive the year, either. In July 2022, she departed amid continued struggles; that same month, she was ousted after a dismal first quarter marked by declining sales.

In the end, the Yeezy experiment became a perfect snapshot of Gap’s modern dilemma. It showed how badly the company wanted cultural relevance—and how dangerous it is to rent it from a volatile celebrity. Unlike Adidas, which would reportedly sell Yeezy designs without the Yeezy label, Gap’s Yeezy product lived off to the side, disconnected from the core assortment. When the partnership collapsed, Gap was left with the exact problem Yeezy Gap was supposed to solve: the hardest question in American apparel—what is Gap now, and why should anyone care?

VIII. Inflection Point #3: The Richard Dickson Reinvention (2023–Present)

In August 2023, Gap Inc. made a hire that raised eyebrows for all the right reasons: Richard Dickson, 56, became President and Chief Executive Officer after spending eight years at Mattel, most recently as President and Chief Operating Officer from 2015 to 2023.

This wasn’t a “steady hands” appointment. It was a signal. Gap was betting that the executive who helped reinvigorate Mattel’s Barbie franchise could do something similar for a portfolio of apparel brands that had spent years drifting. Dickson had already been sitting on Gap Inc.’s board for a year, so he wasn’t walking in blind. By his own account, he knew exactly what he was signing up for—a company in “distress,” with a lot of repair work ahead.

He also represented something Gap hadn’t had in a long time. Dickson is the first merchant to run Gap Inc. in two decades. The previous four CEOs weren’t known as merchants or fashion executives; their strengths were largely outside product. The last true merchant at the helm was Millard “Mickey” Drexler.

So the obvious question is: why would this turnaround work when so many others didn’t?

Dickson’s answer is simple, and it cuts: Gap Inc. had tried to be too many things to too many people. “This company has had legendary talent,” he said. “With compliments to past leadership, everyone came in strategically well intended, with good ideas but flawed execution.”

He’s been particularly blunt about where the clutter showed up. Gap, he argues, chased too many initiatives—new launches, collaborations, constant activity—without fixing the fundamentals, like stores that felt uninspired. At the portfolio level, there was too much overlap and too much internal competition: Gap’s activewear encroaching on Athleta, Old Navy cannibalizing Gap, and brands blurring instead of sharpening.

His response has been systematic and hands-on. He’s gotten into the details of how Gap Inc. speaks, even joking that he sometimes acts as the “Chief Editing Officer,” down to the language on the company’s websites. That same editing mindset has applied to the assortment: under Dickson, the product offering shrank by about 20% as he cut items that didn’t fit the message.

The goal isn’t to abandon basics—it’s to make them feel alive again. “We’ve been really well-known for basics, really across our portfolio, and we’ve been dialing up the fashion quotient,” Dickson said. “And it’s really important to keep consumers engaged, to keep people interested you have to be interesting.”

And, at least in the early innings, the numbers started to match the narrative. “We ended the year delivering another successful quarter, exceeding financial expectations and gaining market share for the 8th consecutive quarter,” Dickson said. “For the full year 2024, Gap Inc. delivered positive comps in all four quarters, achieved one of the highest gross margins in the last 20 years and meaningfully increased operating margin versus the prior year. These strong results are underpinned by the momentum we’re seeing in our operational execution, our culture and the reinvigoration of our brands.”

In fiscal 2024, net sales increased 1% and comparable sales rose 3%. All four brands gained market share during the year. Operating income grew to $1.1 billion, up more than 80%, and the company generated $1.5 billion in operating cash flow.

About a year and a half into Dickson’s tenure, Gap had pushed back into growth and started repairing its brand image. In fiscal 2024, it also posted its highest gross margin in more than 20 years, at 41.3%. After a fourth straight quarter of strong results, the market began to treat this less like a bounce and more like a strategy with staying power.

Just as importantly, cultural moments started to reappear—exactly what Gap had been missing. Zac Posen, Gap’s creative designer, has put the brand back on celebrity radar. Timothée Chalamet has been seen in Posen’s work, and even Banana Republic—a long-time laggard—returned to growth.

The moments weren’t subtle. Actress Da’Vine Joy Randolph wore a denim ball gown designed by Gap’s new creative director, Zac Posen, to the Met Gala. A few weeks later, Anne Hathaway wore a white Gap shirt dress to a Bulgari party. “We were so excited to see that in the marketplace,” Dickson said.

Dickson has also been looking for new ways to extend the brands without losing the plot. He told FOX Business that customers were responding to the beauty category, calling it a “meaningful opportunity” to expand into beauty. The company has already launched Old Navy’s Beauty Collection across 150 stores, and said additional Gap products are expected as soon as spring 2026.

And as the business stabilized, Gap began returning more cash to shareholders. The Board of Directors approved a first quarter fiscal year 2025 dividend of $0.165 per share, a 10% increase compared to the fourth quarter fiscal year 2024 dividend per share.

IX. The Portfolio Strategy & Brand Architecture

Gap Inc.’s four-brand portfolio is both the company’s biggest advantage and the thing that has tripped it up for years. In theory, a house of brands lets you cover multiple customers, price points, and occasions. In practice, it only works if each brand has a sharp identity—and if they don’t blur into each other.

Start with the engine: Old Navy. Full-year net sales were $8.4 billion, up 2%, with comparable sales up 3%. Old Navy is the volume driver, built for value-conscious families who want clothes that feel current enough without feeling expensive. The positioning is clear, which is why it keeps working. It isn’t trying to be the coolest brand in the room; it’s trying to be the dependable one. And it continues to win in categories like active and denim, where innovation and newness have helped it gain market share.

Then there’s the namesake brand—Gap—still fighting the hardest battle: relevance in the middle of the market. Fourth quarter net sales were $980 million, down 3% year over year, even as comparable sales rose 7%. That mix tells you what’s happening. The brand is getting customers back into the stores and back onto the site, but it’s still climbing out of years of discounting and inconsistent product. This is the reinvigoration playbook Dickson keeps talking about: making Gap feel wanted again. But the strategic problem hasn’t changed. Gap still risks being squeezed—too pricey for the Old Navy shopper, too plain for the premium shopper.

Banana Republic has its own identity challenge, shaped by a broader cultural shift: the unraveling of business casual. Once known for upscale workwear, Banana has been searching for the right modern role. It posted 4% comparable sales growth when analysts expected a decline, and it continued building strength in men’s apparel, but it’s still without a CEO—hardly the setup for a clean, consistent brand vision.

And then there’s Athleta, which lives in one of the most competitive arenas in retail. It’s up against Lululemon and a crowded field of athleisure players, all chasing the same customer with constant product drops and brand storytelling. Athleta’s comparable sales fell 2% during the quarter, and Dickson said it missed on offering the right product for its core consumer. He also warned the performance could stay “choppy” as the brand continues its reset.

This is the tightrope with Gap Inc.’s architecture. The portfolio can create leverage—shared supply chain, real estate scale, digital infrastructure—but only if the brands stay distinct. When the lines get fuzzy, the company ends up competing with itself, like when Gap’s activewear starts stepping on Athleta’s lane. In a portfolio like this, differentiation isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the whole game.

X. The Retail Business Model & Competitive Dynamics

Gap’s business model was built for control. It’s vertically integrated—designing the product, sourcing it, moving it through its own distribution network, and selling it in its own stores and online. In the Drexler years, that setup was a real weapon: better margins, tighter consistency, and the ability to respond to trends faster than traditional department-store brands.

But “control” doesn’t mean “immune.” In fiscal 2024, substantially all of Gap Inc.’s merchandise purchases, by dollar value, came from factories outside North America—about 27% from Vietnam and about 19% from Indonesia. That concentration keeps the machine efficient when the world is calm. When it isn’t—when costs jump, trade rules change, or shipping lanes snarl—it turns into a pressure point. Gap is explicit about the risk: disruptions or cost increases tied to imports from Vietnam, Indonesia, or other countries—including tariffs, restrictions, or taxes—could hit operations hard.

You can see that tension in the outlook. For fiscal 2025, Gap projected net sales growth of 1–2% and operating income growth of 8–10%. But it also warned that potential tariff impacts could dent results by $100–$150 million. In a low-margin, high-volume business, that’s not noise—it’s strategy.

Meanwhile, the distribution side of retail—where you sell—has been shifting under everyone’s feet. By the end of fiscal 2024, Gap Inc. operated 2,506 company-run stores and had another 1,063 franchise locations. And the direction of travel is clear: for the year ahead, the company planned to close 35 stores on a net basis, with most of those closures coming from Banana Republic. The physical footprint is being trimmed and reshaped, not treated as sacred.

The other structural reality is the promotional trap. Gap spent years teaching customers to wait for a deal, and once you train that behavior, it becomes part of your brand whether you like it or not. Getting out isn’t about one fewer coupon email. It takes two hard things at once: product that’s genuinely worth paying full price for, and the discipline to say no to the quick hit of volume that comes from constant discounting—even if that means taking some short-term pain.

And then there’s the channel shift that’s been remaking retail for a decade. Online sales grew 6% and made up 39% of total sales. Digital penetration is still climbing, and Gap has made progress, but it’s also playing catch-up—because it was slower to fully embrace e-commerce than the digital-native brands that rewrote the rules while mall traffic was collapsing.

XI. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Medium-High

In fashion, it still doesn’t take much to get started. Barriers to entry are low, and direct-to-consumer brands like Everlane and Allbirds have proven you don’t need a sprawling store base to build something real. Social media can manufacture awareness fast, without the old-school marketing budget.

What’s harder is getting to Gap’s level of scale. Supply chain relationships, brand recognition, and an omnichannel setup do offer some protection. But it’s not a fortress—more like a head start that only matters if you keep running.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low-Medium

Gap’s size gives it leverage with contract manufacturers, and it negotiates and pays for substantially all foreign merchandise purchases in U.S. dollars. That helps.

But costs still swing with commodity volatility—cotton and synthetics don’t care about your annual plan. And as expectations rise around ethical sourcing, the pool of acceptable suppliers narrows, which quietly shifts some power back to the factories.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High

Customers have endless options and basically no switching costs. Apparel loyalty is emotional, not structural—and it’s especially fragile with younger shoppers. If you miss, the feedback loop is immediate and public. Gap’s logo fiasco proved how quickly the internet can turn a brand decision into a pile-on.

On top of that, years of discounting across the industry have trained shoppers to expect promotions. When buyers assume there’s always a deal coming, they’re the ones setting the terms.

Threat of Substitutes: Very High

This is where the ground gets hardest. Fast fashion players like Shein, Zara, and H&M keep the product feeling new, at prices that are tough to match, with far quicker turnover. At the other end, premium brands—like Lululemon in activewear—pull away customers who are willing to pay more for status, performance, or perceived quality. Amazon continues to grow in apparel, quietly siphoning basics and convenience purchases. And resale platforms like ThredUp and Poshmark give sustainability-minded shoppers an alternative that doesn’t require buying new at all.

Competitive Rivalry: Intense

Apparel is a knife fight. Market share is fragmented, and the competition comes from every angle: ultra-fast fashion, value giants like TJ Maxx, and premium brands like Aritzia. Meanwhile, mall traffic keeps declining, which forces everyone to fight harder for fewer in-person shoppers—while also spending to build out digital capabilities. In other words, the battle is everywhere, all at once.

XII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Weak

Gap has real scale in procurement, logistics, and running a multi-brand retail machine. The problem is: scale isn’t exclusive anymore. Fast fashion rivals match it—and often beat it on speed. And in digital marketing, size doesn’t buy you the kind of cost advantage it used to. Meanwhile, what once looked like a moat—a huge store footprint—now often acts like drag, especially in the wrong malls.

Network Effects: None

There’s no true network effect in apparel retail. More customers don’t automatically make the product better or lock in the next customer. Social proof matters—people copy what they see—but it doesn’t compound into a durable advantage the way it does in marketplaces or social platforms.

Counter-Positioning: Historically Strong, Now Lost

Gap’s original move was classic counter-positioning: while department stores were chaotic and inconvenient, Gap made buying jeans simple—focused assortment, organized by size, easy returns, no friction.

Then the script flipped. Fast fashion counter-positioned against Gap with speed to market. DTC brands counter-positioned by cutting out retail intermediaries and selling direct. The company that once disrupted the old system became the incumbent the next wave disrupted.

Switching Costs: Very Weak

In fashion, switching costs are basically zero. Loyalty isn’t structural; it’s emotional. Customers can try a competitor on a whim and lose nothing if it doesn’t work out. That keeps pressure permanently high—and makes consistency brutally important.

Branding: Moderate but Fading

If Gap has a power to lean on, it’s branding—but it’s uneven across the portfolio. Old Navy still has meaningful equity with value-focused families. The Gap brand has lost a lot of cultural pull, even if the awareness remains. Athleta is still building its position in a tough category. Branding can create preference, but here it hasn’t been strong enough to offset the structural headwinds.

Cornered Resource: None

Gap doesn’t have a cornered resource competitors can’t replicate—no proprietary tech, no unique supply access, no irreplaceable talent bench. Even real estate, once an advantage, is now neutral at best in a digital-first era. In fashion, the closest thing to a cornered resource is cultural relevance—and that’s exactly what Gap lost, and what it’s now trying to rebuild.

Process Power: Weak

Gap’s processes aren’t meaningfully better than the competition’s. In the post-Drexler years, the design and merchandising engine—the part that used to translate taste into product at scale—lost its edge. Dickson’s turnaround hinges on rebuilding that excellence, not on some inherently superior operating system.

Key Takeaway: Gap has weak to no durable competitive advantages. That means the business lives and dies on execution—brand, product, and culture—an inherently hard thing to sustain in fashion retail.

XIII. The Bear Case vs. Bull Case

The Bear Case:

The structural decline of mall-based retail looks stubborn, and maybe permanent. Every year, foot traffic gets a little worse. That squeezes Gap from both sides: it has to keep closing stores, while also building a more digital business with very different economics, talent needs, and competitive dynamics.

The Gap brand itself may be the bigger problem. After two decades of drifting in and out of relevance, the damage might not be fixable. For a lot of Gen Z shoppers, Gap isn’t a discovery brand. It’s their parents’ brand. And once a label gets filed away like that, winning it back is brutally hard.

Then there’s the price-and-speed war. Ultra-fast fashion players like Shein operate on a cost structure Gap can’t realistically match. If competitors can churn out trend-responsive product for a fraction of the price, Gap’s value proposition collapses for the exact customers it needs most: price-sensitive shoppers who still want something that feels current.

The broader wallet share trend isn’t helping, either. Younger consumers are spending more on experiences—travel, restaurants, entertainment—and less on accumulating clothes. That’s not a short-term cycle. It’s a behavioral shift.

Competition keeps coming from everywhere. Amazon continues to absorb basics and convenience-driven apparel purchases, while DTC brands keep building direct relationships and tighter feedback loops with consumers—often without the overhead of thousands of stores.

Sustainability could become another squeeze point. Climate change, regulation, and shifting consumer expectations are all pushing the industry toward higher standards. That creates real risk for any value-driven model, because the pressure to be “greener” often shows up as higher costs and tougher scrutiny.

And even if Gap sees the right moves, it may not have unlimited freedom to make them. Debt and pension obligations reduce flexibility, and they constrain how much the company can spend, how aggressively it can restructure, and how long it can wait for results.

The Bull Case:

The core argument for Gap is that the company finally has the right kind of leader for this moment. Richard Dickson has a track record of restoring cultural relevance—his work on Barbie at Mattel is the proof point—and at Gap he’s already paired brand work with operational execution. Under his direction, the company returned to growth, repaired its brand image, and in fiscal 2024 posted its highest gross margin in more than 20 years at 41.3%.

Old Navy remains the anchor. It still has room to run with value-conscious families, and it has the clearest positioning in the portfolio. In fiscal 2024, Old Navy net sales were $8.4 billion, up 2% year over year—steady performance from the business that drives the most volume.

Athleta is a second, bigger swing. The brand is struggling right now, but the category is still massive—activewear is a $100+ billion market—and Athleta has awareness, distribution, and an existing customer base that could support a rebound if the product reset lands.

Profitability can also improve even without blockbuster growth. Store closures and cost rationalization matter in a low-margin business. If Gap keeps shedding underperforming locations and puts investment behind the stores, categories, and channels that work, margins can keep expanding.

And the brands still have something money can’t easily buy: awareness. Gap, Old Navy, Banana Republic, and Athleta are familiar names. New entrants have to spend huge sums just to get remembered; Gap starts already in the public mind, and that’s a real foundation if the product earns another look.

There are also cleaner ways to grow than building more company-owned stores. Franchising and licensing can extend reach with less capital and less risk, especially in international markets.

The market has noticed the early execution. Since November 2023, Gap’s total return rose 56%, beating the S&P 500, largely on improving margins and investor confidence that the turnaround is real.

And finally, the cultural tide might be shifting. As backlash builds against ultra-fast fashion—on quality, labor practices, and sustainability—some consumers may drift back toward brands that can credibly offer better-made basics and a more responsible story. If that happens, Gap doesn’t have to outrun Shein on speed. It just has to stand for something clear again.

XIV. Business & Investing Lessons: The Playbook

The Curse of the "Good Enough" Brand

For years, Gap became the default—what you bought when you didn’t want to think too hard, or when nothing else felt worth the money. That’s a deceptively dangerous place to live. In a market with infinite choice, “good enough” doesn’t build loyalty; it builds indifference. Brands don’t win by being broadly acceptable. They win by being specifically loved.

Cultural Relevance is Perishable

Brand equity isn’t a savings account you can live off forever. Gap had a defining cultural moment in the 1990s, then spent the next two decades trying to stretch it—while competitors kept earning fresh attention from new generations. Relevance has to be renewed. If you stop investing in it, you don’t just stand still. You fall behind.

The Portfolio Trap

A house of brands only works when each brand is sharp. Gap Inc.’s portfolio often did the opposite: it added complexity while the identities blurred. Each brand needed focused leadership and a distinct point of view, but shared resources and overlapping lanes made it easier to compromise than to differentiate. Multiple okay brands don’t magically add up to one great company.

Real Estate as Moat vs. Millstone

In the mall era, a massive store footprint was a competitive advantage. It meant access, convenience, and presence. Then the world moved: traffic shifted online, malls declined, and that same footprint became expensive drag—leases, labor, inventory, and constant pressure to discount to keep stores busy. Distribution changes can flip a strength into a weakness faster than most companies can reorganize.

The Operational CEO Fallacy

Retail is operational, but fashion is also taste. Gap learned the hard way that efficiency can’t substitute for instinct. The previous four CEOs weren’t known as merchants or fashion executives, and the last true merchant at the helm was Millard “Mickey” Drexler. In creative businesses, operations can keep you alive—but product and brand are what make you matter.

Fast Fashion Changed Everything

The disruption wasn’t just cheaper clothes. It was a faster system. Speed to market became the advantage that rewired the industry, and Gap’s traditional design-to-shelf cycle couldn’t keep up with players like Zara. In many industries, the winners don’t innovate the product first—they innovate the process that delivers the product.

The Middle is Murder

This is Clayton Christensen in real time: you can be premium, or you can be value, but it’s brutal to be stuck in between. Gap got squeezed from below by fast fashion and value giants, and from above by premium brands with stronger stories. When the middle hollowed out, “reasonable price for decent basics” stopped being enough.

Logo Changes Reveal Deeper Problems

The logo fiasco wasn’t a design problem. It was a leadership problem. When a brand can’t explain what it is, it reaches for symbols—new logos, new campaigns, new slogans—as if a surface change can create meaning. It can’t. Visual identity only works when it expresses a strategy that already exists.

Celebrity Partnerships are High-Risk

Yeezy Gap showed the upside and the danger in one shot. A partnership can inject culture into a brand overnight—but when your relevance is rented from a person, you inherit all the volatility of that person. If they change, the brand pays. Cultural shortcuts aren’t free; they just move the risk somewhere else.

Turnarounds Take Longer Than Anyone Thinks

Gap has been “turning around” for more than twenty years. New CEOs arrived with credible plans, and many still couldn’t land the plane. Big enterprises don’t transform on announcements. They transform through years of consistent product, clear positioning, and the discipline to keep doing the boring fundamentals even when the market wants a dramatic gesture.

XV. The Future: What Happens Next?

Can Richard Dickson finish what he’s started, or is this just turnaround attempt number seven in a two-decade streak of false dawns?

In the year ahead, Gap expected sales to grow 1% to 2%—basically in line with what the market was already modeling. For the nearer-term quarter, the company’s tone was more cautious, guiding sales to be “flat to up slightly.” As finance chief Katrina O’Connell put it, “We’ve been operating in a highly dynamic backdrop for the last few years, and we’re expecting the same for fiscal 2025.”

The real story won’t be told in slogans. It’ll be told in a few stubborn, unglamorous numbers.

The key metrics to watch:

Comparable Store Sales Growth is still the cleanest read on whether the brands are actually getting healthier. Positive comps suggest customers are coming back and buying more—not just that the company is shrinking its way to “better” results through store closures.

Gross Margin Trajectory is the tell on discipline. It captures whether Gap can sell more product at full price, manage inventory tightly, and resist the familiar impulse to reach for promotions the moment demand softens. The company’s strongest margin performance in two decades was a real signal; the question is whether it can hold.

Old Navy’s Performance matters more than anything else because it’s the volume engine. If Old Navy stumbles, it can overwhelm progress at Gap, Banana Republic, or Athleta. If it keeps humming, it buys the rest of the portfolio time.

Longer-term questions remain:

Will Gen Z actually embrace Gap again—or has the brand aged into nostalgia? Dickson’s playbook has leaned into cultural sparks: Zac Posen moments, celebrity sightings, campaigns built to travel online. But a viral moment isn’t the same thing as a durable relationship with a new generation.

How will AI and personalization reshape fashion retail? Gap has customer data and an omnichannel foundation it can build on, but it’s not alone. Many competitors have just as much data—and in some cases, sharper technical muscle to turn it into habit-forming experiences.

What happens as sustainability pressures intensify? Regulation and consumer expectations around textile waste, water use, and supply chain transparency could change the economics of affordable fashion. For a company that sources heavily from overseas factories, those shifts won’t be theoretical—they’ll show up in costs, timelines, and what product even makes sense to sell.

And finally: what is Gap Inc. structurally meant to be from here? An acquirer, buying its way into new growth? An acquisition target, with valuable brands and infrastructure? Or an independent portfolio company that can finally make the house of brands work? The Fisher family’s substantial ownership and continued board involvement point toward staying the course—but if results disappoint, strategic alternatives will come back fast.

XVI. Epilogue & Final Reflections

Gap’s story is, in a lot of ways, America’s story: ambition, innovation, triumph, complacency, decline—and the stubborn question of whether reinvention is ever truly possible.

Don and Doris Fisher took a frustrating jeans-return experience and built an empire. Mickey Drexler turned that empire into a cultural force that helped define how America dressed. And then, slowly and painfully, the thing that once felt inevitable—Gap as the default uniform—started to fade. Success hardened into habit. Habit turned into sameness. And sameness, in fashion, is a fast track to irrelevance.

The tragedy of Gap isn’t that it failed once. It’s that it kept almost fixing itself. Over and over, the company launched turnaround plans with reasonable ideas and real effort behind them. But it couldn’t escape the gravitational pull of its own history, its portfolio complexity, and an industry that doesn’t reward “pretty good.” Apparel punishes hesitation. It punishes muddled positioning. It punishes being late.

What makes this story stick isn’t just the strategy—it’s how personal it feels. Gap is in our closets, our malls, our memories. For a lot of people, it was the brand you wore to school without thinking, until one day you stopped thinking about it at all. That’s the loss. But it’s also the opening, because getting back to “I don’t have to think—this just works” is exactly what made Gap powerful in the first place.

Since 1969, Gap Inc. has created products and experiences that have shaped culture, while doing right by employees, communities, and the planet. Whether that mission can be revived—whether Gap can once again shape culture rather than merely observe it—remains the central question as Richard Dickson enters his third year at the helm.

For investors, the lesson travels well beyond Gap: fashion retail is one of the hardest games in business. Competitive advantages are fragile. Rivalry is relentless. And winning requires sustained excellence—product, pricing, and positioning all aligned—quarter after quarter, year after year. Few companies pull that off. Even fewer do it again after losing their way.

The hope for Act III—that Gap can become culturally relevant again—isn’t irrational. Dickson has already shown what a focused, merchant-led approach can unlock. “It’s the first time that all four brands have reflected positive comps in many years. In fact, we were sort of looking for when they had and it was difficult to find,” CEO Richard Dickson told CNBC.

But hope isn’t strategy, and one strong year doesn’t guarantee the next. Gap’s journey continues, as it has for fifty-five years—through triumph and tragedy, and everything in between.

XVII. Further Reading & Resources

If you want to go deeper—into Gap’s arc, and into the retail forces that reshaped the whole industry—these are the best places to start:

-

"The End of Fashion" by Teri Agins — A clear-eyed look at how fashion became mass-market, and why retail power shifted the way it did.

-

Gap Inc. Annual Reports (2000, 2010, 2020, 2024) — The most direct record of the company’s rise, decline, and the long, uneven fight back.

-

"The New Rules of Retail" by Robin Lewis — A practical guide to what changed in consumer behavior, distribution, and the economics of modern retail.

-

Harvard Business Review case studies on the decline of American apparel — Useful context for why specialty retail got squeezed, and why “mall casual” became such a brutal place to operate.

-

"Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion" by Elizabeth Cline — The environmental and social cost of fast fashion, and the competitive pressure it created for brands like Gap.

-

Mickey Drexler interviews and profiles — The philosophy of the merchant era: instinct, editing, and why product is the strategy.

-

Richard Dickson’s Mattel turnaround case studies — The playbook behind the “Barbie guy,” and what it suggests about how he might rebuild relevance at Gap.

-

Gap’s investor presentations (2019–2025) — A real-time view of how management explained the strategy as conditions changed—and what they chose to prioritize.

-

"Billion Dollar Brand Club" by Lawrence Ingrassia — Helpful framing for the DTC wave that rewired branding, distribution, and expectations.

-

RetailWire and Business of Fashion archives on Gap — The ongoing pulse: critiques, reporting, and industry reaction as the turnaround unfolds.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music