fuboTV: The Sports-First Streaming Bet

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

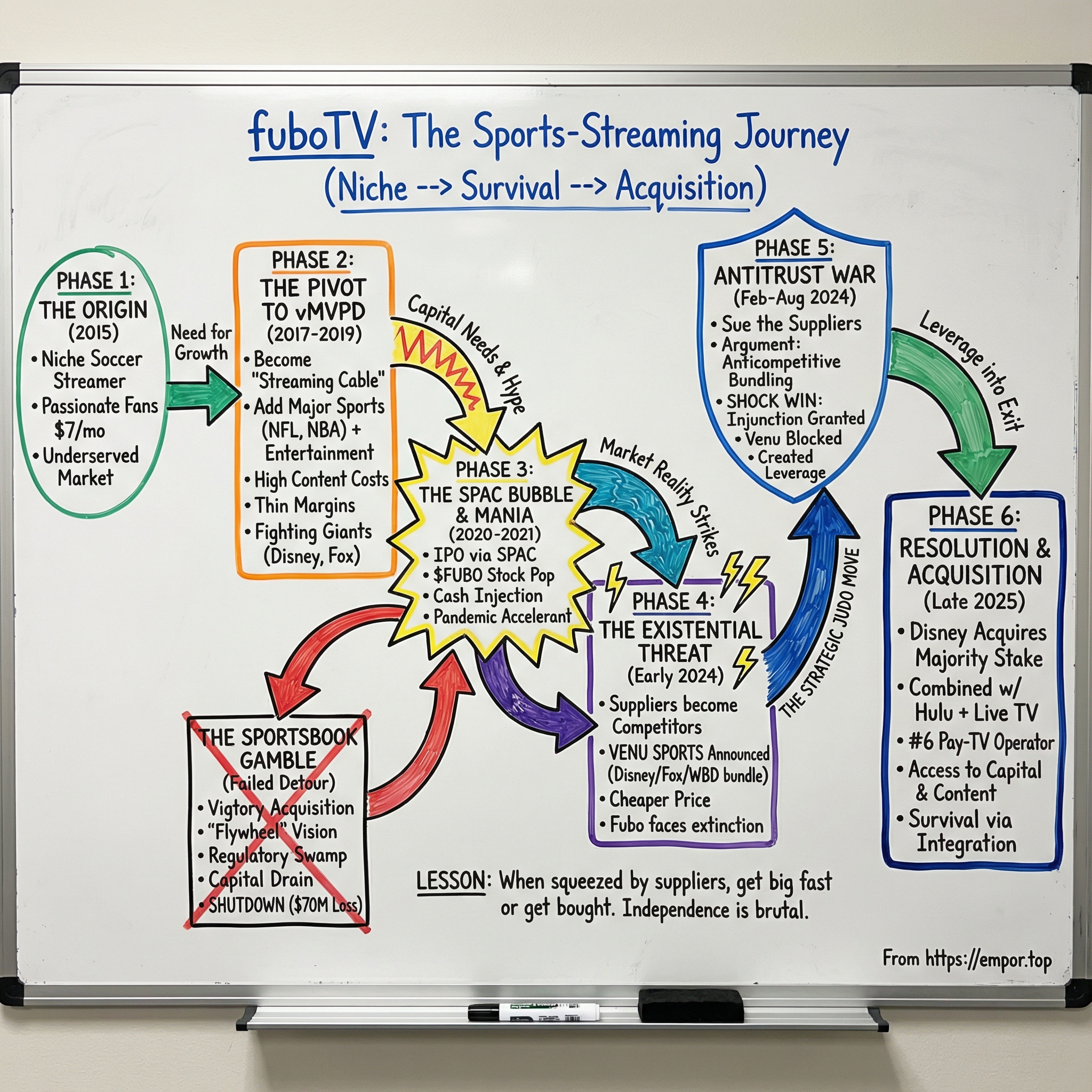

Picture this: it’s September 2024, and David Gandler is in a Manhattan conference room, staring across the table at lawyers representing three of the most powerful media companies on Earth. Disney. Fox. Warner Bros. Discovery. The same giants who control the sports rights Americans actually care about had just announced Venu Sports, their own streaming bundle.

For fuboTV, the company Gandler had built from a scrappy soccer-streaming upstart into a public company doing well over a billion dollars in revenue, this wasn’t just “new competition.” It was the nightmare scenario. The suppliers who fed fubo its lifeblood were about to step around the table, become the retailer, and sell the bundle directly—on terms only they could set.

And Gandler didn’t blink. He sued.

The story that follows—from that lawsuit to its surprising end—ends up being a perfect window into the future of live sports streaming, and the brutal reality of trying to survive as the middle layer in an industry racing toward vertical integration.

By the end of 2024, fuboTV looked nothing like the niche soccer service it started as. The company posted record North America results: $1.588 billion in revenue (up 19% year over year) and 1.676 million paid subscribers (up 4%). It also delivered its first quarter of positive free cash flow, and improved key profitability metrics by more than $100 million on an annual basis for the second straight year.

Then came the twist. In October 2025, Disney completed its acquisition of a majority stake in fubo, creating the sixth-largest pay-TV operator in the U.S. when combined with Hulu + Live TV. Together, the two services served nearly 6 million subscribers in North America.

So how did we get here? How did a company that began by streaming soccer matches for expats nearly turn itself into a sportsbook? And why does fubo’s journey end up revealing something bigger—about where television is headed, and who gets to make money in the streaming era?

This is a story of pivots—some brilliant, some painful. It’s about what happens when your partners decide they’d rather compete with you. It’s about live sports, the last true appointment viewing left in an on-demand world. And it’s about a strategic judo move so rare you almost never see it in business: suing your way into becoming an acquisition target.

Let’s dive in.

II. The Origin Story: Soccer Streaming in a Pre-Cord-Cutting World

In early 2015, streaming didn’t feel inevitable. Netflix was still, in plenty of living rooms, “that DVD company.” YouTube TV didn’t exist. Hulu was a media-company joint venture, not a Disney powerhouse. And the idea that Americans would one day pay close to $100 a month for cable channels delivered over the internet would’ve sounded ridiculous.

That’s the world fuboTV was born into.

In January 2015, David Gandler, Alberto Horihuela, and Sung Ho Choi co-founded fuboTV as a simple, soccer-first streaming service. At launch, it cost $7 a month and offered livestreams from soccer-centric channels. The bet wasn’t that streaming would win someday. The bet was that a certain kind of fan already needed it.

The founding team was an unusual blend for a media startup, and that turned out to be the point. Gandler came from the business side of television—more than 15 years in video sales across local broadcast and cable, spanning both general and Hispanic audiences. He’d worked at Scripps Networks Interactive, Time Warner Cable Media Sales, and NBCUniversal’s Telemundo Media. He understood how TV money moved, and he understood an audience that traditional packages often underserved.

Horihuela brought a different angle: product and entrepreneurship in video. He’d been head of Latin America for the SVOD service DramaFever (later acquired by Softbank and part of Warner Bros. Digital Networks). He’d also co-founded PrimeraRed Network, a digital video ad network focused on U.S. Hispanic markets, along with Dokarta. Earlier in his career, he’d worked as an economist and analyst, including roles at Morgan Stanley and DeMatteo Monness.

And then there was Choi, the CTO—the technical counterweight who could actually build the thing.

Together, they saw a gap that’s obvious in hindsight but took real conviction at the time: American soccer fans were stuck in a rights maze with no good exit. If you wanted the Premier League, you needed one subscription. Serie A, another. La Liga, somewhere else. And plenty of international matches—the games many fans cared about most—weren’t reliably available through any legal option at all.

fuboTV’s insight was simple: bundle the soccer. Make it work. Make it easy. Let people pay directly for what they actually wanted.

The service caught on fast with a specific kind of customer: passionate, tech-savvy fans who were tired of cobbling together cable packages, satellite add-ons, and sketchy streams just to watch the sport they loved. And while the broader streaming market already had big names, none of them were building for this viewer.

In 2015, fuboTV raised a $5.5 million Series A led by DCM Ventures. Over nine rounds before going public, the company raised about $155 million in total.

The early product-market fit wasn’t subtle. Soccer fans aren’t casual viewers. They plan their weekends around fixtures. They wake up at strange hours for matches across the Atlantic. And live sports isn’t like entertainment: there’s no real “catch up later” behavior. You can binge a drama a year after it comes out. You can’t binge a match. The whole value is in the moment, which makes the customer relationship inherently stickier—if you can deliver.

But even in the early days, the team knew the wedge was narrow. A niche gets you traction. It doesn’t necessarily get you scale.

You can see that ambition in who backed them. Over its first five years, fuboTV’s investors included AMC Networks, Luminari Capital, Northzone, Sky, and Scripps Networks Interactive. fuboTV was also named to Forbes’ Next Billion-Dollar Startups list in 2019.

Those names weren’t just checks. Sky, in particular, lived and breathed sports television. Scripps brought deep programming and distribution knowledge. AMC knew premium content and audience building. The message was clear: this could be bigger than a soccer app.

Of course, “just stream it” sounds easy until you’re the one doing it—especially with live sports. On-demand video can buffer and recover. Live sports can’t. A five-second delay doesn’t just annoy customers; it ruins the experience when the neighbor’s cheer spoils the goal. Latency matters. Consistency matters. Reliability matters. Delivering high-quality streams at scale is brutally expensive, and it’s exactly the kind of complexity that can either crush a young company or become a real advantage later.

By the end of fuboTV’s soccer-first phase, the team had proven something foundational: there was real demand for live sports on the internet, and fans would pay for a service that respected the way they watched.

The next question was the one that would define everything that came after: could fubo evolve fast enough to ride the much bigger wave that was starting to form as cord-cutting accelerated across the U.S.?

III. The First Major Pivot: Becoming a vMVPD

In early 2017, fubo made the move that would determine whether it stayed a niche product or had a shot at becoming a real television company. It pivoted from “soccer streaming” into a broader live TV bundle—adding entertainment and news, and expanding its sports lineup to include programming tied to the NFL, NBA, MLB, and NHL.

This wasn’t a side quest. It was a full strategic repositioning.

fubo was betting on a chain reaction: that its soccer audience was really a broader sports audience, that sports fans were really live-TV fans, and that live-TV fans were actively searching for a cable alternative. But every link in that chain came with a cost. More channels meant higher programming fees. Higher programming fees meant higher prices. And higher prices meant you were no longer selling an app for diehards—you were selling a cable replacement, with cable replacement expectations.

That’s what a vMVPD is, in plain English: streaming cable. The acronym—virtual multichannel video programming distributor—sounds like something invented to make consumers stop asking questions. But the product was easy to understand. Sling TV had launched in 2015. YouTube TV arrived in 2017. Hulu Live followed that same year. The new battleground was set: who could rebuild the cable bundle for the internet era?

For fubo, the hard part wasn’t the concept. It was the supply chain.

To become a legitimate alternative, fubo had to cut deals with the very companies that built the old system: Disney (with ESPN and ABC), NBCUniversal, Fox, and ViacomCBS. And those negotiations weren’t friendly. These were powerful suppliers with little incentive to make things easy for a startup that, in the best-case scenario, would one day weaken their grip on distribution.

Programming was expensive, and it didn’t get cheaper just because it was delivered over the internet. fubo had to manage rising fees and, at times, make the kind of unpopular decisions that come with the territory—dropping channels to control costs, then dealing with customer backlash. That’s the core economic reality of the vMVPD business: margins are thin, content costs are relentless, and every lineup change is both a financial decision and a brand risk.

Those deals also exposed a tension that would follow fubo for years: dependency on suppliers who might eventually become competitors. Disney, for example, wanted fubo to pay a premium for ESPN—the crown jewel of live sports—but Disney also had every reason to build its own streaming future, one where it didn’t need middlemen.

So fubo had to differentiate somewhere else. It leaned hard into product.

The company rolled out features designed for live sports fans: cloud DVR, multi-stream viewing, and interactive overlays. In 2017, it launched Cloud DVR storage, the ability to pause and resume live streams, and a “lookback” feature for content aired in the previous 72 hours. It offered two simultaneous streams in the base package and, in March 2018, added a third stream for $5.99 per month.

And then came the statement piece: video quality.

fubo became the first live TV streaming service to support 4K HDR video for the 2018 World Cup. When the biggest soccer event on earth arrived, fubo could credibly say it offered the best-looking stream available on any virtual cable bundle. For the kind of sports viewer who actually cares about the viewing experience—and plenty do—that mattered.

Of course, this pivot came with a cultural trade-off. The moment you carry HGTV, Food Network, and CNN, you’re not “the soccer streaming service” anymore. You’re competing directly with everyone else selling a bundle. But the upside was the whole point: the addressable market expanded from a relatively small group of soccer obsessives to the much larger universe of cord-cutters trying to replace cable.

By 2018, fubo had crossed 100,000 subscribers—proof that the broader positioning was resonating.

That same year, the company pushed beyond the U.S., launching in Spain and becoming the first U.S. virtual MVPD to enter Europe. It was an ambitious move, and it hinted at a much bigger vision. But it also came with a reality check: content rights are intensely local, and what works in the U.S. doesn’t simply copy-paste across borders. International expansion would become a repeating mix of promise and pain.

As Fast Company put it, fubo still called itself “sports-first,” but it was no longer trying to be “the Netflix of soccer.” Now it was pitching itself as a direct competitor to cable—and to live streaming bundles like Sling TV and AT&T TV (now DirecTV Stream).

The pitch evolved into something simple and durable: come for the sports, stay for the entertainment. Use comprehensive sports coverage—especially Regional Sports Networks—to win the household, then keep the household by being a full live TV solution.

Investors took away something important from this era: fubo’s team knew when a strategy had hit its ceiling, and they could execute a transformation without losing the company’s DNA. That adaptability would matter. Because the next pivot wouldn’t just test their product instincts or their negotiating skill.

It would test their judgment.

IV. The SPAC Moment & Growth Acceleration

The spring of 2020 was a strange time to be in the live sports business. The NBA suspended its season. The NHL went dark. Major League Baseball hit pause. And fuboTV—a company built around the simple promise of live sports—was suddenly staring at an empty calendar.

It was also, somehow, a moment to go public.

On March 23, 2020, fuboTV announced it would merge with FaceBank Group, a publicly listed virtual entertainment technology company founded by media technology entrepreneur John Textor, through a reverse triangular merger. The combined company would be called fuboTV Inc., led by fubo’s CEO David Gandler. The deal closed quickly, on April 2, 2020.

Even in the anything-goes era of 2020 market mechanics, this was an odd pairing. FaceBank wasn’t known for sports or streaming. It was known for hyper-realistic digital humans—celebrity likenesses and hologram-style performances designed for VR, AR, live entertainment, and other emerging media. Years earlier, the company (then called Pulse Evolution) helped produce a Michael Jackson hologram performance at the Billboard Music Awards. It also created a virtual Tupac in 2012 and held rights tied to digital representations of icons like Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe.

So yes: on paper, it was a sports streaming bundle merging with a “hologram company.”

The stated rationale was that the combined business could become a broader digital entertainment platform, blending fubo’s direct-to-consumer live TV streaming for cord-cutters with FaceBank’s technology and celebrity IP relationships to enhance sports and entertainment offerings over time.

But in March 2020, the more practical synergy was capital.

In its SEC filing, FaceBank said it had secured a $100 million revolving line of credit for fuboTV as an “inducement” for fubo to enter the merger. In the early weeks of COVID—when markets were seizing up and uncertainty was everywhere—that kind of liquidity mattered far more than any futuristic digital-human roadmap.

Then came the real public-market launch. On October 7, 2020, fuboTV completed its initial public offering on the New York Stock Exchange, raising roughly $183 million in proceeds. It began trading under the ticker “FUBO” on October 8, and the stock jumped about 10% in its debut.

Soon after, the FaceBank chapter faded into the background. Textor resigned as Executive Chairman, and the board brought in a name that signaled media-world seriousness: Edgar Bronfman Jr., former chairman of Warner Music Group, as Executive Chairman. Bronfman—heir to the Seagram fortune and a veteran of multiple entertainment industry reinventions—added credibility and connections that reached deep into the ecosystem fubo depended on.

What happened next was the kind of move that only makes sense in the context of 2020 and early 2021. In December 2020—just a couple months after the NYSE listing—fubo’s stock hit an intraday high of $62. The market briefly priced fubo like it was not just a streaming bundle, but a category-defining winner.

It wasn’t hard to see why investors got swept up. The pandemic accelerated streaming behavior. Cord-cutting intensified. And when sports began returning, live programming snapped back as a magnet for subscribers. With fresh capital from the IPO, fubo could spend more aggressively on content, technology, and marketing—and the subscriber base climbed fast, passing the half-million mark.

By November, the company said it had reached one million subscribers—roughly doubling annually.

In May 2021, fubo reported what it called the strongest first quarter in its history: $119.7 million in revenue, up 135% year over year, with 590,430 total subscribers, up 105%. Gandler framed it as an “inflection point,” noting that fubo grew revenue and subscribers sequentially in a first quarter despite typical seasonality.

Wall Street’s story for fubo was clean and emotionally satisfying. Streaming was clearly becoming the default way people got video. And sports—unlike scripted entertainment—didn’t really time-shift. DVR changed how people watched dramas and comedies, but nobody “catches up” on a big game the next day. If sports were the last pillar holding up the old cable bundle, then a streaming service built around sports could ride cord-cutting all the way to massive scale.

But going public didn’t just unlock capital. It also turned fubo into a stock—priced every day, judged every quarter, and compared relentlessly to companies with very different economics. fubo was still losing money and spending heavily to acquire subscribers. The stock’s wild swings created noise and pressure. And that cocktail—public-market expectations plus a fresh war chest—set the stage for the next decision.

Because with the company newly public and the market rewarding big narratives, management was about to chase a storyline even bigger than streaming.

V. The Sportsbook Gamble: Bold Vision or Distraction?

In January 2021, fuboTV was riding high. The stock had more than tripled since its IPO and hovered around $36. The company had just passed 545,000 subscribers. And David Gandler had a vision that felt tailor-made for the moment: fuse live sports streaming with sports betting, inside one product, and turn watching into a more interactive, more valuable habit.

fubo put it in headline form with a binding letter of intent to acquire Vigtory, a sports betting and interactive gaming company, and said it expected to launch a sportsbook before the end of the year.

On paper, it was almost too clean. fubo already had the audience: sports fans, showing up live, paying real money every month. If even a portion of those fans were also bettors—and many were—then fubo didn’t just have a streaming service. It had the top of a funnel that DraftKings and FanDuel were spending fortunes to buy.

Gandler leaned into the flywheel story.

"We believe online sports wagering is a highly complementary business to our sports-first live TV streaming platform," he said. "We don't see wagering as simply an add-on product to fuboTV. Instead, we believe there is a real flywheel opportunity with streaming video content and interactivity."

And fubo wasn’t treating this like a hobby. The leadership bench signaled intent. Scott Butera—then known for his role running interactive gaming at MGM Resorts International and helping launch BetMGM—joined Vigtory as Rattner’s co-CEO in 2020. Before that, he’d held senior roles across the gaming world, from Foxwoods to Tropicana to the Cosmopolitan, plus a stint as commissioner of the Arena Football League.

In Butera’s words, the deal wasn’t just a product expansion. It was a new category.

"The addition of Vigtory to FuboTV is a pivotal event in the sports entertainment industry," he said. "As sports fans increasingly desire interactive sports events, sports betting and related businesses such as iGaming and free to play contests have become a critical component of fan engagement. Combining fuboTV's broad and deep offering of live streamed sporting events with Vigtory's world-class sports betting products creates the ultimate sports betting experience for consumers."

The market loved it. On the day fubo announced the Vigtory deal, the stock jumped 34% as investors ran the mental math on a future where fubo wasn’t just a thin-margin bundle reseller, but a platform skimming high-margin betting revenue from the same fans already watching games.

Then reality showed up.

fubo launched Fubo Sportsbook on November 3, 2021: a mobile wagering app integrated with its live TV streaming platform. It started in Iowa, with plans to expand to more states.

But sports betting in the U.S. isn’t one market. It’s fifty. Each state has its own licensing, approvals, compliance rules, and—often—the requirement to partner with a local casino or tribal operator to gain market access. DraftKings and FanDuel had spent years building that machinery. fubo was trying to assemble it mid-flight.

The results reflected that gap. In Iowa, Fubo Sportsbook handled a little under $2 million in wagers during calendar year 2022 and generated $116,822 in revenue, according to figures compiled by the Iowa Racing and Gaming Commission. In a market dominated by the two giants, it barely registered.

Arizona looked somewhat larger, but the story was the same. Through the most recent report compiled for July by the state’s Department of Gaming, Fubo Sportsbook recorded just under $4 million in all-time handle. To put a single month in context: in March 2022, fubo’s handle was $879,565—about 0.127% of the roughly $690 million wagered statewide that month.

This was the core problem. fubo was trying to take on DraftKings and FanDuel while they were spending over a billion dollars a year to acquire customers—at the same time fubo’s streaming business was still burning cash. Two capital-intensive battles, at once, against incumbents built for exactly those battles.

Less than two years after the vision was unveiled, fubo pulled the plug. The company announced it would close its Fubo Gaming subsidiary and shut down its owned-and-operated sportsbook operations immediately.

"Following our previously announced strategic review, we have concluded that continuing with Fubo Gaming and Fubo Sportsbook in this challenging macroeconomic environment would impact our ability to reach our longer term profitability goals," Gandler said. "Therefore, we have made the difficult decision to exit the online sports wagering business effective immediately."

fubo said exiting sports betting would cost approximately $70 million and result in layoffs.

The shutdown was the end of a strategic review the company had disclosed in an Aug. 4 shareholder letter. fubo said multiple parties expressed interest in the business, but none of the options would have lowered funding needs enough to produce attractive returns for shareholders.

What went wrong wasn’t mysterious. It was just brutal.

First, sports betting is a scale business. The leaders benefit from massive marketing budgets, deep risk management infrastructure, and the momentum that comes from already being where bettors are.

Second, the regulatory timeline moved slowly. By the time fubo could expand meaningfully, the early-land-grab phase in many states had already passed—and customers had already picked their apps.

Third, the capital requirements were far larger than a streaming company could casually absorb. Competitors weren’t spending millions; they were spending billions.

And fourth, the killer insight: the promised synergy didn’t force behavior change. Bettors were already comfortable using a second screen while watching. The pain of placing a bet in a separate app wasn’t high enough to make “integrated” betting the reason someone switched platforms.

The sportsbook chapter leaves a clean lesson behind. Pivot when your core strategy hits its ceiling—but don’t let a hot public-market narrative convince you that you can build two expensive businesses at the same time.

Investors, for their part, seemed relieved. After the shutdown announcement, fubo’s stock jumped double digits in early trading. The market wasn’t rewarding ambition anymore. It was rewarding focus.

VI. The Existential Threat: Venu Sports & the Antitrust Battle

In February 2024, fuboTV made one of the most consequential bets in its history. Instead of watching helplessly as its three biggest content suppliers prepared to launch a competing product that could undercut fubo’s pricing by more than half, the company went to war.

fubo filed an antitrust lawsuit against Disney, Fox, and Warner Bros. Discovery, arguing that the three vertically integrated media giants had spent years using their control over sports content to box fubo in, inflate its costs, and limit consumer choice.

The threat had a name: Venu Sports. And it wasn’t theoretical. Venu had been aiming to launch within weeks, with an announced starting price of $43 a month—$36 less than fubo’s cheapest plan. In an internal Venu document introduced during the hearings, the joint venture partners described an “ocean of opportunity” between traditional pay-TV bundles priced around $70 to $80 per month and entertainment subscription streamers like Netflix, Peacock, and Disney+ in the single digits.

To fubo, that “ocean” was the entire business.

And the irony wasn’t lost on anyone. fubo had long argued that a “skinny” sports bundle was exactly what it wanted to offer from the beginning. But when it tried to license sports networks without also taking on big bundles of general entertainment channels, fubo said it got nowhere.

So the lawsuit didn’t just argue that Venu would be tough competition. It argued that the game was rigged.

fubo claimed Disney, Fox, and Warner Bros. Discovery used bundling requirements and “significantly above-market licensing fees” to push up fubo’s programming costs—costs that inevitably flowed through to consumers. In court documents, U.S. District Judge Margaret Garnett noted that the three companies control about 54% of all U.S. sports rights and at least 60% of nationally broadcast U.S. sports rights. She added that there was “significant evidence in the record that the true figures may be even larger.”

Gandler didn’t mince words.

“Each of these companies has consistently engaged in anticompetitive practices that aim to monopolize the market, stifle any form of competition, create higher pricing for subscribers and cheat consumers from deserved choice,” he said. “By joining together to exclusively reserve the rights to distribute a specialized live sports package, we believe these corporations are erecting insurmountable barriers that will effectively block any new competitors from entering the market.”

The case quickly became bigger than fubo. Lawmakers, distribution rivals, and public interest groups publicly warned that Venu could harm consumers by concentrating even more power in the hands of the same companies that already controlled the rights. Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, along with Representative Joaquin Castro, sent a letter to the Department of Justice and the FCC. DirecTV and Dish filed amicus briefs supporting fubo. Politicians from both parties piled on.

Then came the moment no one expected: fubo won.

In August 2024, after several days of testimony from high-level media executives, Judge Garnett granted fubo’s request for a preliminary injunction, blocking Venu’s launch.

Gandler called it “a victory not only for Fubo but also for consumers,” adding, “This decision will help ensure that consumers have access to a more competitive marketplace with multiple sports streaming options.”

In her ruling, Garnett pointed to a 1981 case, U.S. v. Columbia Pictures, where movie studios tried to form a cable channel with exclusive access to new films. She wrote that the facts were “strikingly similar,” describing it as an earlier moment of rapid industry change where competitors attempted to coordinate in a way that could limit competition.

And she didn’t just worry about what Venu would do to the market. She worried about what it would make the partners stop doing.

“Once the JV launches, the JV defendants have no reason to take actions that could allow for the emergence of direct competitors,” Garnett wrote. “Quite the opposite: the multi-year monopolistic runway they have created for themselves will provide powerful incentives to thwart competition and hike prices on both consumers and other distributors.”

fubo’s stock jumped roughly 16% to 20% on the news.

But the injunction wasn’t the end of the story. It was the opening move.

Because what happened next was even more remarkable: rather than spend years in court, Disney pivoted toward a deal.

VII. The Streaming Wars Context & Competitive Dynamics

To understand why fubo’s lawsuit mattered so much—and why Disney ultimately found it easier to buy than to fight—you have to understand the arena fubo was fighting in. The vMVPD market, “streaming cable,” is one of the most punishing corners of media: brutal competition, thin margins, and suppliers with more leverage than the distributors trying to sell their channels.

At the top of the leaderboard sits YouTube TV. It crossed 8 million subscribers in early 2024, and industry sources later pegged it as nearing 10 million—helped in a big way by bundles tied to NFL Sunday Ticket. Google can afford to play a longer game than almost anyone: it can sustain losses, lean on the gravity of the broader YouTube ecosystem, and benefit from built-in distribution advantages through Android devices. That combination is a moat independent players don’t get to have.

Then there’s Hulu + Live TV, which—under Disney’s ownership—is now tied to fubo’s story in a very direct way. Hulu + Live TV has been in the next tier with roughly 4.6 million subscribers, and it has a bundling superpower: Disney+, ESPN+, and the core Hulu service can all be packaged together in a way a standalone vMVPD simply can’t replicate.

Sling TV helped invent the category, but it’s had a harder time holding onto momentum as the price gap between “skinny” bundles and fuller-featured competitors has narrowed. DirecTV Stream has gone after a more premium segment, but it’s also operated under the cloud of AT&T’s strategic uncertainty around the asset.

Underneath all of those brands is the same structural problem: the economics are punishing. Content costs make up the vast majority of expenses, and those costs are largely fixed. When Disney, Fox, or NBCUniversal raises carriage fees—as they regularly do—the distributor has three choices, and all of them hurt: eat the increase, raise prices, or risk losing channels customers consider non-negotiable.

So where can a company like fubo differentiate, if it doesn’t control the content and can’t win on scale?

fubo’s answer has been to build for the sports fan who actually cares. In the U.S., it positioned itself as a sports-first cable replacement, offering more than 400 live sports, news, and entertainment networks, and claiming to be the only live TV streaming platform with every English-language Nielsen-rated sports channel. And it leaned into a real product edge: technical quality. fubo was out early with 4K streaming among vMVPDs, and for live sports—where the viewing experience is the product—that’s not a gimmick.

Another key wedge has been Regional Sports Networks. fubo has carried many RSNs, which has helped it stand out from other streaming providers. Even as RSNs have struggled financially, with several declaring bankruptcy, fubo has maintained broader coverage than many competitors—an especially meaningful differentiator for fans trying to follow local MLB, NBA, and NHL teams.

That differentiation also pushed fubo toward the premium end of the market. Average revenue per user in the fourth quarter was $87.90 in the region, an all-time high for the company and up 1.4% year over year. That’s higher than most competitors, and it reflects a deliberate choice: fubo wasn’t trying to be the cheapest bundle. It was trying to be the best one for serious sports households.

But premium positioning comes with premium problems. The moment prices rise, a chunk of customers will do the math and decide they can live without something. And the comparison set is always moving. A price-sensitive household might pick YouTube TV instead, especially if they’re already in the YouTube ecosystem and the “effective price” feels lower once other subscriptions and bundles enter the picture.

All of this circles back to the reason live sports remain the most valuable content in the streaming era. Sports solve a core problem that entertainment streaming still struggles with: getting people to show up at a specific time, pay for it, and stay engaged. Games are watched live or they’re not watched at all. And once you know the score, the product loses most of its value.

That’s why rights for the NFL, NBA, MLB, and college football keep commanding premium prices even as so many other parts of the media business get squeezed. Sports are appointment viewing, and appointment viewing still prints money—because advertisers will pay more to reach someone who is locked in, emotionally invested, and paying attention than someone half-watching a drama in the background.

VIII. Technical Moats & Product Innovation

In a business where competitors often carry the same channels at roughly the same prices, the product itself stops being a nice-to-have. It becomes one of the only levers you can still pull. For fuboTV, that’s meant treating technical execution not as plumbing, but as a competitive weapon.

The flagship example came early. fubo was the first live TV streaming service to support 4K HDR, debuting it during the 2018 World Cup, and it was also first to adopt an industry standard for streaming quality optimization. For sports, that kind of quality isn’t subtle. Standard definition versus HD versus 4K is the difference between “I’m watching the game” and “I can actually see the game.” The blades of grass. Jersey numbers. A ref’s hand signal. And in sports where the object you’re tracking is tiny and fast—hockey, baseball, golf—higher resolution can be the difference between following the play and just trusting the announcer.

fubo also chose to build its tech stack internally. That’s a trade: more cost and complexity up front, in exchange for control later—control over features, over performance, and over how fast you can ship improvements. In 2017, the company rolled out Cloud DVR, the ability to pause and resume live streams, and a lookback feature that let users watch content that had aired in the last 72 hours. And it leaned into a reality of modern sports watching: households don’t have one screen anymore. fubo included two simultaneous streams in its base plan and, in March 2018, added a third stream for $5.99 per month.

Then it pushed into features that were explicitly built for sports-first viewing behavior. fubo was the first virtual MVPD to launch 4K streaming and MultiView, and it did it years ahead of many peers, along with Instant Headlines, a first-of-its-kind feature. MultiView—multiple games on one screen—sounds simple until you try to execute it across different TVs, devices, and network conditions. But it taps into something real: the Sunday-afternoon chaos of overlapping games, the fantasy scoreboard mindset, the second-screen bettor mentality. It’s not just “more content.” It’s a better way to consume the same content.

And looming over all of this is the problem that every live sports streamer wrestles with: latency. A delay of even five to ten seconds is enough to ruin the experience, because the world will spoil the play for you. The neighbor cheers. The group chat explodes. Social media posts the highlight before you’ve seen it. fubo has invested heavily in reducing latency, but true broadcast-like synchronization across every device and every internet connection is still one of the hardest problems in the category.

That challenge gets even nastier when you remember where people watch. fubo has to perform on streaming devices, Smart TVs, mobile phones, tablets, and computers. Each platform has different hardware, different operating systems, different update cycles, and different failure modes. Great execution here doesn’t win headlines, but poor execution absolutely loses customers.

In November 2025, fubo added another layer to its product strategy with the launch of the Fubo Channel Store. Inside the fuboTV app, customers could subscribe to premium streaming channels like DAZN One, Hallmark+, MGM+, and others. It’s a “super aggregator” move: even when fubo isn’t the one licensing the content for the core bundle, it can still aim to be the place where the customer manages—and increasingly watches—their subscriptions.

The market has noticed the focus on experience. fubo earned the highest score in J.D. Power’s customer satisfaction evaluations among vMVPDs. For 2024, J.D. Power gave fubo a score of 578, ahead of DirecTV Stream’s 558. fubo trailed YouTube TV (651), Hulu + Live TV (635), and Sling TV (613), but the comparison is telling: fubo’s customers skew toward demanding sports fans, and sports fans tend to be the harshest judges of whether the product actually works when it matters.

None of this is a permanent advantage. A technical moat is real, but it’s also perishable. Features like 4K, cloud DVR, and MultiView eventually spread across the market, and then the bar resets. Which is why the next frontier matters: personalization and AI-driven discovery—using viewing data to surface what you care about, when you care about it, and keep you engaged without making you hunt for the next game.

IX. Business Model Deep Dive & Unit Economics

To understand fuboTV’s business model, you have to start with an uncomfortable truth: in live TV streaming, the distributor is often the middle layer—and the middle layer gets squeezed.

fubo’s revenue comes from two places: subscriptions and advertising. Subscriptions are the foundation. In North America, the company finished full year 2024 with $1.588 billion in total revenue, up 19% year over year, driven largely by monthly packages that generally land in the roughly $80 to $100 range depending on the tier.

Advertising is the second engine—and the one with more upside. It’s smaller than subscriptions, but it’s been growing faster. In Q4 2023, fubo’s ad revenue rose 15% year over year to $38.6 million. The strategic appeal is obvious: if you can grow ads without meaningfully growing content costs, that incremental revenue is far more valuable than another dollar of subscription fees that mostly gets passed through to programmers.

Connected TV makes that possible. Unlike traditional linear TV, CTV ads can be targeted—two households can watch the same game and see different ads, based on demographic and behavioral signals. And sports audiences are especially attractive: they show up live, they stay through breaks, and they’re easier to define than the average “I put something on in the background” entertainment viewer. That combination can support premium pricing for ads.

On the other side of the ledger is the cost that defines the entire category: content. The carriage fees fubo pays to programmers like Disney, Fox, NBCUniversal, and ViacomCBS dominate the expense structure. And they behave like a fixed tax on the business. Whether a service has one million subscribers or two million, it still has to carry a massive slate of channels—and pay escalating per-subscriber fees to do it.

That creates a structural doom loop for the whole industry. As cord-cutting reduces the number of traditional cable households, programmers try to make up the lost revenue by charging higher fees per remaining subscriber. Distributors respond by raising prices. Higher prices drive more churn. And the cycle repeats.

That’s why “profitability” has been the storyline investors care about most. In North America, fubo ended 2024 with record revenue and paid subscribers, delivered its first quarter of positive free cash flow, and improved key profitability metrics by more than $100 million on an annual basis for the second consecutive year. It wasn’t a victory lap so much as evidence that the company could tighten execution in a business where the math rarely works out cleanly.

Growth is still expensive, though. Customer acquisition costs are meaningful in a market where consumers can switch services with a few clicks, and fubo has to constantly decide how hard to push marketing versus how quickly to narrow losses. Every price increase is a margin lever—and a churn risk.

And churn has its own clock: the sports calendar. In vMVPD land, subscriber counts tend to swell through football season, then soften when the sports schedule gets lighter. That seasonality makes forecasting harder and puts extra pressure on retention efforts, because the easiest time to cancel is precisely when the perceived value dips.

All of this leads to the question hanging over fubo for years: can an independent vMVPD ever reach durable, profitable scale, or does the category inevitably consolidate? The Disney merger points to one answer. Combined with Hulu + Live TV, fubo gains scale, more leverage in negotiations, operational efficiencies, and the practical comfort of Disney’s balance sheet—advantages that are hard to manufacture as a standalone.

Even with that, the business remains at the mercy of its content relationships. Looking ahead, fubo projected Q1 2025 revenue of $400 million to $410 million, implying low single-digit year-over-year growth at the midpoint, while also projecting 1.430 million to 1.460 million total subscribers, a mid-single-digit year-over-year decline at the midpoint. The message embedded in that guidance is the same one that’s haunted the company since it became a vMVPD: in this business, content disputes and carriage negotiations can move your numbers as much as any product feature ever will.

X. Strategic Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Step back from the quarterly guidance and the headline drama, and fubo’s position comes into focus with two classic strategy lenses: Michael Porter’s Five Forces and Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers. Different tools, same goal: explain why this has been such a hard business to win, and what—if anything—could make it easier.

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate-to-Low

On paper, the barriers are steep. To launch a vMVPD you need expensive content deals, real streaming infrastructure, marketing spend, billing, customer support—the whole cable-company machine, rebuilt for the internet. That keeps most startups out. But the “new entrant” risk doesn’t come from scrappy newcomers. It comes from giants. Amazon, Apple, or another deep-pocketed platform can afford patient losses and already owns distribution, devices, and customer relationships.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Very High

This is the force that basically explains the category. The companies that own the must-have sports networks—Disney, Fox, NBCUniversal, and others—set the terms. They can raise fees, insist on bundling, and, when it suits them, compete directly with the distributors who carry their channels. Venu Sports was the clearest example of the core vulnerability: when your suppliers decide to go direct, your business model starts to look like a temporary arrangement.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High

Customers can switch with a few taps. There’s no installation, no technician, no long-term contract. And as households get more selective about subscriptions, price sensitivity rises. The monthly billing cycle turns every month into a renewal decision—and in sports, that decision is heavily influenced by the calendar.

Threat of Substitutes: High

Traditional cable is still the default for many sports households. Some fans can stitch together individual apps like ESPN+, Peacock, and Paramount+ to get pieces of what they want without paying for a full bundle. Antenna TV is free for over-the-air broadcasts. And piracy remains a persistent substitute, especially for international sports and hard-to-find matches.

Competitive Rivalry: Very High

This is a knife fight. YouTube TV has scale and Google’s backing. Hulu + Live TV has Disney’s bundling power (and is now tied directly to fubo’s story). Sling and DirecTV Stream are still in the ring, fighting on price and positioning. Everyone sells broadly similar channel lineups, which pushes competition toward the only levers left: price, promotions, and product quality—while margins get squeezed the whole way down.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies: Limited

fubo gets some benefits from scale in technology and ad sales. But the biggest cost—programming—doesn’t give you the kind of compounding advantage you’d see in software or marketplaces. More subscribers help, but not enough to create a runaway winner.

Network Effects: Weak

This isn’t a social product. The service doesn’t become meaningfully better because more people subscribe. Each customer’s experience is mostly independent, which means there’s no natural flywheel that locks in advantage over time.

Counter-Positioning: Historically Strong, Now Diluted

In the early days, “sports-first streaming” was real differentiation. Traditional players couldn’t fully lean into it without disrupting their existing models. But as fubo expanded into a full cable replacement, that edge softened. And Venu highlighted the uncomfortable truth: content owners can reclaim “sports-first” whenever they want, because they own the thing that makes sports-first possible—the rights.

Switching Costs: Low

There isn’t much friction to leaving. Cloud DVR recordings can create some stickiness, but not the kind that holds when a competitor has a better channel mix or a lower price.

Branding: Moderate

Among serious sports fans, fubo built credibility. In the broader market, awareness is thinner, and the brand doesn’t carry the kind of pricing power you’d associate with a truly dominant consumer name.

Cornered Resource: None

fubo doesn’t own exclusive content that rivals can’t replicate. The rights live elsewhere, and competitors can often license the same networks. That’s a tough place to build a durable advantage.

Process Power: Moderate

Where fubo has consistently punched above its weight is execution: streaming quality, sports-centric features, and overall customer experience. That’s real. It’s also fragile—because it has to be defended with constant investment, and well-funded competitors can eventually copy a lot of what works.

Power Analysis Conclusion:

On its own, fubo’s strategic position is difficult. The company operates in a market with powerful suppliers, fickle customers, intense competition, and few structural moats. That’s why the Disney deal matters: vertical integration can change the rules by aligning content and distribution under one roof—potentially turning fubo from “the squeezed middle layer” into part of the stack that does the squeezing.

XI. The Road Ahead: What Happens Next

The Disney merger closed in October 2025, and it didn’t just tidy up the Venu fight. It rewired fuboTV’s place in the industry.

On October 29, 2025, Disney completed its acquisition of a majority stake in fubo. Combined with Hulu + Live TV, it created what the companies described as the No. 6 pay-TV operator in the U.S. Disney would control 70% of the new streaming organization, with fubo shareholders retaining the rest.

A month later, the scale was already coming into view. As of November 2025, the company said the combined fubo and Hulu + Live TV business totaled nearly 6 million subscribers in North America. fubo itself reported 1.63 million paid subscribers in North America.

What’s notable is who stayed in charge. fubo’s existing management team, led by co-founder and CEO David Gandler, would run the new fubo. In other words: the same operator who navigated the pivots, the SPAC, the sportsbook detour, and the antitrust fight now got to do it with Disney behind him.

The deal also changed what fubo could sell. As part of the transaction, Disney agreed to a new carriage agreement with fubo that would let fubo create a new Sports & Broadcast service featuring Disney’s major sports and broadcast networks—ABC, ESPN, ESPN2, ESPNU, SECN, ACCN, ESPNEWS—alongside ESPN+.

And Disney wasn’t only bringing channels. The combined company would have access to a $145 million term loan that Disney committed to provide fubo. In the wake of the Venu battle, the industry had started to flirt with more focused packages—bundles that used to be considered impossible under the old pay-TV economics.

The settlement itself came with real dollars attached. Disney, Fox, and Warner Bros. Discovery agreed to make an aggregate cash payment of $220 million to fubo. Disney also committed to provide a $145 million term loan to fubo in 2026. And there was a backstop: a $130 million termination fee would be payable to fubo under certain circumstances, including if the transaction failed to close due to the failure to obtain requisite regulatory approvals.

The companies painted an ambitious financial picture of what this new entity could become. In a preliminary proxy statement filed in July, the combined company was projected to reach $6.4 billion in revenue and a profit of $90 million for full-year 2025, growing to $8.24 billion in revenue and $540 million in profit by 2029.

Next comes the hard part: proving that the post-deal strategy can actually work in the market. fubo said it was targeting the release of its sports bundle—including content from non-Disney networks—for the fall. “We are working hard to secure content from non-Disney programmers for the new service,” Gandler said. “It is critical for Fubo subscribers that we are able to negotiate content licensing agreements at fair rates and terms.”

Because the bigger story here isn’t just fubo. It’s the future of live sports distribution, being written in real time.

Traditional cable kept sliding—Charter, Comcast, and DirecTV still held a big share of the pay-TV market, but the direction was clear as internet-based bundles gained traction. YouTube TV, with nearly 10 million subscribers, had become the category leader. The combined fubo-Hulu business now had a plausible shot at being the primary challenger to Google’s dominance.

And the next wave won’t be fought only over channel lineups. Technology wildcards are sitting on the horizon. AI-powered personalization could reshape how viewers find what to watch. Interactive viewing features—the instinct behind fubo’s short-lived sportsbook—could return in new forms. Social integration could change how fans experience games together, even when they’re nowhere near the same couch.

One conclusion already feels hard to escape. The question of whether independent vMVPDs can survive has, at least partially, been answered: they can’t—not at meaningful scale. The economics are too punishing without either the distribution leverage of a tech giant like Google, or the vertical integration of a content owner like Disney. fubo’s arc—from insurgent to affiliate—may end up being the template for what happens to everyone else caught in the middle of the streaming wars.

XII. Playbook: Lessons for Founders & Investors

fuboTV’s journey reads like a decade-long stress test: disruption, pivots made under fire, and a constant search for leverage in a business designed to squeeze the middle. If you’re building—or backing—companies in markets that are changing fast, there’s a lot to steal from what worked, and a lot to learn from what didn’t.

When to Pivot and When to Stay Focused

The 2017 pivot from a soccer-only service into a full vMVPD wasn’t optional. Soccer may have been a passionate wedge, but it wasn’t a big enough market to support a durable standalone company. fubo saw where the puck was going: cord-cutting was accelerating, and sports fans weren’t looking for one league or one channel. They wanted a real cable replacement.

The 2021 sportsbook push was different. It was a capital- and attention-hungry detour that didn’t create a lasting edge. The key distinction is capability fit. The vMVPD pivot extended what fubo already knew how to do—acquire rights, stream reliably, serve sports fans. The sportsbook required building a new business from scratch in a category dominated by incumbents with massive marketing spend and deep regulatory infrastructure.

Fighting Battles You Can Win

The Venu Sports lawsuit looked, at first glance, like a David-versus-Goliath stunt. It was actually a calculated bet with asymmetric outcomes. If fubo did nothing, a $43-per-month sports bundle from its own suppliers could have gut-punched its value proposition and crushed its subscriber base. By suing, fubo created options: win the injunction (which it did), or at minimum force a negotiation that changed its fate.

The lawsuit didn’t just delay a competitor. It flipped the narrative. fubo went from being a distributor trapped by supplier power to being a strategic problem Disney chose to solve with a deal.

Capital Allocation in Capital-Intensive Businesses

The SPAC-era access to capital was both rocket fuel and a temptation. It helped fund technology investment, content deals, and growth initiatives. But it also made it easier to rationalize the sportsbook buildout.

The takeaway is simple and painful: in capital-intensive businesses, focus is a form of defense. You don’t get infinite at-bats. Investing hardest where you actually have an advantage tends to beat spreading resources across multiple unrelated bets, especially when each bet is expensive on its own.

Competing Against Your Suppliers

For most of its life, fubo’s success depended on companies that had mixed feelings about that success. Disney, Fox, and others wanted fubo’s carriage fees, but they also wanted to keep control of distribution economics. Venu was the inevitable endgame of that tension: suppliers deciding to become the storefront.

The lesson is structural. If your suppliers control essential inputs, you need a plan that doesn’t assume they’ll stay friendly. That plan is usually one of two things: become large enough to be hard to ignore, or find a path to vertical integration. fubo ultimately landed on the second path through the Disney acquisition.

The SPAC Lesson

Going public through a SPAC got fubo to the public markets quickly, but it also meant living under constant scrutiny, stock volatility, and the pressure to tell ever-bigger stories. That environment can distort decision-making, especially when the market is rewarding narrative more than discipline. It’s not hard to see how those dynamics could have made the sportsbook ambition feel more urgent—and more justifiable—than it turned out to be.

Niche to Mainstream Transitions

“Come for the sports, stay for the entertainment” wasn’t just clever positioning. It was the necessary path from niche traction to household relevance. But broadening always comes with trade-offs: the more you look like a full bundle, the harder it is to stay sharply differentiated.

fubo largely managed the balance—keeping a sports-first identity even as it carried hundreds of channels—but the underlying truth remains: expanding your addressable market often means diluting the purity of what made you special.

Technical Excellence as Competitive Advantage

In a world where multiple services carry similar channel lineups, execution becomes strategy. fubo’s early push into 4K streaming, MultiView, and sports-centric features helped it win demanding customers who cared about how the product felt, not just what it carried.

Technical excellence isn’t an uncopyable moat, but it can justify premium positioning and reduce churn—especially in live sports, where one bad stream at the wrong moment can lose a customer for good.

Know Your Exit

Not every company gets to independent, enduring scale—especially in industries where economics favor giants. But building strategic value still creates outcomes. fubo’s sports-focused audience, streaming capabilities, and the leverage it created through the Venu fight made it valuable to Disney in ways that went beyond fubo’s standalone trajectory.

For founders and investors, that’s the closing lesson: “worth acquiring” is not a consolation prize. In some markets, it’s the most realistic win condition.

XIII. Bear vs. Bull Case

Bear Case:

The skeptics look at fuboTV and see a business that’s structurally set up to struggle. Margins stay thin—or negative—because the biggest cost, programming, keeps climbing faster than fubo can reliably raise prices. And fubo doesn’t have the kind of durable defenses that usually change that math: it doesn’t own exclusive content, network effects are weak, switching costs are low, and suppliers hold most of the leverage.

Then there’s YouTube TV. Scale creates a compounding advantage in this category: more subscribers can mean better terms, better terms can support a better bundle, and a better bundle can attract more subscribers. Google also has the luxury of patience. It can absorb years of losses in pursuit of market share in a way a smaller, standalone operator can’t—especially when investors are demanding a path to profitability.

Even the Disney deal isn’t a guaranteed fix. Integrating two products with different histories and customer expectations can get messy and expensive. Regulators could slow or limit what the combined company can do next. And if Disney’s strategic focus shifts—toward ESPN direct-to-consumer, theme parks, or the film slate—fubo could end up as a non-core asset inside a much larger machine.

The biggest risk remains the oldest one: content renewals. If carriage fees keep escalating faster than revenue, margin expansion becomes a treadmill no amount of operational tightening can outrun. And the Regional Sports Network turmoil—multiple RSNs in bankruptcy—shows how quickly the economics of “must-have” sports distribution can change.

Bull Case:

The optimists start from a different premise: sports streaming is where live TV is headed, and fubo is now sitting closer to the center of that future than it ever could on its own. Traditional cable continues to bleed subscribers, quarter after quarter. Over time, tens of millions of households will look for an internet replacement, and the combined fubo-Hulu + Live TV footprint gives Disney a real shot at building the most credible challenger to YouTube TV.

More importantly, the Disney integration can solve fubo’s core vulnerability: competing against the companies you have to buy from. With Disney as majority owner, content that used to be a constraint becomes part of the strategy. If access to ESPN, ABC, and Disney’s broader sports portfolio comes with better economics and more stability, it changes the cost structure that has defined fubo’s struggle for years.

Advertising is the other wild card, and it’s the one with the most upside. Connected TV advertising keeps growing as linear TV declines. Sports audiences are unusually valuable—they show up live, they stay engaged, and they’re easy for advertisers to target. If fubo can scale advertising faster than subscriptions, it can expand margins without needing to win an endless price war on the bundle itself.

And then there’s the team. fubo’s management has repeatedly shown it can navigate existential moments: pivoting from soccer to a full vMVPD, surviving the COVID-era sports shutdown, walking away from the sportsbook detour, and using the Venu fight to create leverage. With steadier capital and stronger content alignment under Disney, that operational discipline has a better chance of turning into sustained profitability.

What to Watch:

The handful of metrics that will tell you where this story is going are:

-

Subscriber Growth/Churn: Can the combined business grow subscribers—or at least hold share—while keeping churn under control? Seasonality will always create noise, so the year-over-year trend matters most.

-

ARPU Trends: Average revenue per user is the signal for pricing power and mix. ARPU rising with stable subscribers is healthy. ARPU rising while subscribers fall can be a warning sign that price increases are pushing customers out.

-

Advertising Revenue Growth: This is the clearest path to margin expansion. If advertising grows faster than subscriptions, fubo is capturing more value from the audience it already has—without paying proportionally more for content.

XIV. Epilogue: Reflections & Surprises

The fuboTV story has a delicious irony that feels uniquely modern: a company sued its way into getting acquired.

When David Gandler filed an antitrust lawsuit against Disney, Fox, and Warner Bros. Discovery in February 2024, the obvious goal was to stop Venu Sports and buy fubo time—time to keep serving customers without a supplier-backed bundle undercutting it overnight. What the lawsuit also did was prove something even more valuable: fubo wasn’t just a tiny distributor complaining about the rules. It was a real platform with real leverage, willing to fight, and capable of changing the trajectory of the market.

That path—from plaintiff to acquisition target—shows just how fast the ground can shift in streaming. The Venu partners believed they could launch a product that would crush an independent vMVPD. The federal court didn’t see it that way. The injunction blocked the launch, and suddenly the economics of “we’ll just steamroll them” turned into “we may be stuck in court for years.” With a trial date looming and uncertainty piling up, Disney chose the cleaner answer: stop fighting and start owning.

Zoom out, and the deeper takeaway is about consolidation. In live TV streaming, “independent distribution” is increasingly a temporary state, not a destination. The content owners control the rights fans actually show up for. They set the carriage fees that determine whether distributors can make money. And if they don’t like the middle layer, they can try to route around it—exactly what Venu represented. In that world, there are only a few stable places to stand: massive scale, like YouTube TV with Google behind it, or vertical integration, like fubo ultimately got through Disney.

And none of this is slowing down. The sports streaming wars are still in the early innings. Rights are fragmenting across platforms, new packages keep emerging, and every major player wants a direct relationship with the fan. That fragmentation is a headache for viewers, but it’s also an opening for whoever can become the default place you start—an aggregator with enough breadth to feel like “the one app,” even in a splintered landscape. The fubo-Hulu combination gives Disney a real shot at being that hub.

fubo’s sportsbook detour fits neatly into the story as a cautionary tale. It was ambitious, narratively perfect for the SPAC era, and brutally hard to execute. And it underlined a lesson founders keep re-learning the expensive way: when your core business is structurally pressured, the answer usually isn’t to bolt on a second structurally pressured business and try to win both at once. Focus and realism beat a great investor pitch.

Maybe the wildest part is just how far the company traveled. fubo began in 2015 as a $7-a-month soccer streaming service for a very specific kind of fan. A decade later, it was part of a combined pay-TV operation serving nearly 6 million subscribers in North America, backed by Disney. From “the Netflix of soccer” to a key piece of a media giant’s distribution strategy—without ever becoming the biggest streamer on the board.

And the through-line, the thing fubo was right about from the start, is still the thing powering the whole category: live sports are the last reliable engine of attention. People don’t just watch; they show up on time, they stay, and they care. fubo built its entire existence around that insight. The bet didn’t pay off in the way the early pitch decks probably imagined. But it paid off in the way that matters in industries like this: by making fubo strategically important enough that, when the giants came knocking, it didn’t get wiped out.

XV. Further Reading & Resources

If you want to go deeper—into the economics that make streaming cable such a grind, the legal mechanics behind the Venu fight, and the bigger arc of media consolidation—here are the most useful places to start.

Top Long-Form Links: 1. fuboTV SEC filings (S-1, 10-Ks, 8-Ks on investor relations site) — The primary source: strategy, risks, and unit economics straight from the company. 2. "The Economics of Virtual MVPDs" — Stratechery by Ben Thompson — A clear breakdown of why vMVPDs are structurally tough businesses. 3. "Why Sports Streaming Startups Struggle" — The Information — Reporting on the realities behind the “sports-first” dream. 4. "Venu Sports and the Future of Sports Bundling" — Puck News — Industry context on why Venu was such a serious threat. 5. David Gandler interviews and earnings call transcripts — The closest thing to a running commentary on fubo’s decisions and pivots. 6. "Vertical Integration in Streaming: Disney's Strategy" — Matthew Ball's blog — The strategic lens for understanding why Disney moved from supplier to owner. 7. fuboTV antitrust complaint and court filings — The argument fubo made about bundling, fees, and foreclosure, in full detail. 8. Judge Garnett's preliminary injunction ruling — The court’s reasoning, and the competitive dynamics it found persuasive. 9. MoffettNathanson research on vMVPD economics — A widely cited analyst view of the category’s economics and pressures. 10. Sports Business Journal coverage of the streaming wars — Consistent reporting on rights, bundles, and the shifting power map.

Books: * Streaming, Sharing, Stealing by Michael D. Smith & Rahul Telang — A grounded look at how digital distribution reshapes industries. * The Platform Delusion by Jonathan A. Knee — A skeptical, useful counterweight to “platform” hype. * The Master Switch by Tim Wu — A long historical view of how media industries consolidate, open up, and consolidate again.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music