Fastly Inc.: The Story of Edge Computing's Broken Promise (or Unfinished Revolution?)

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

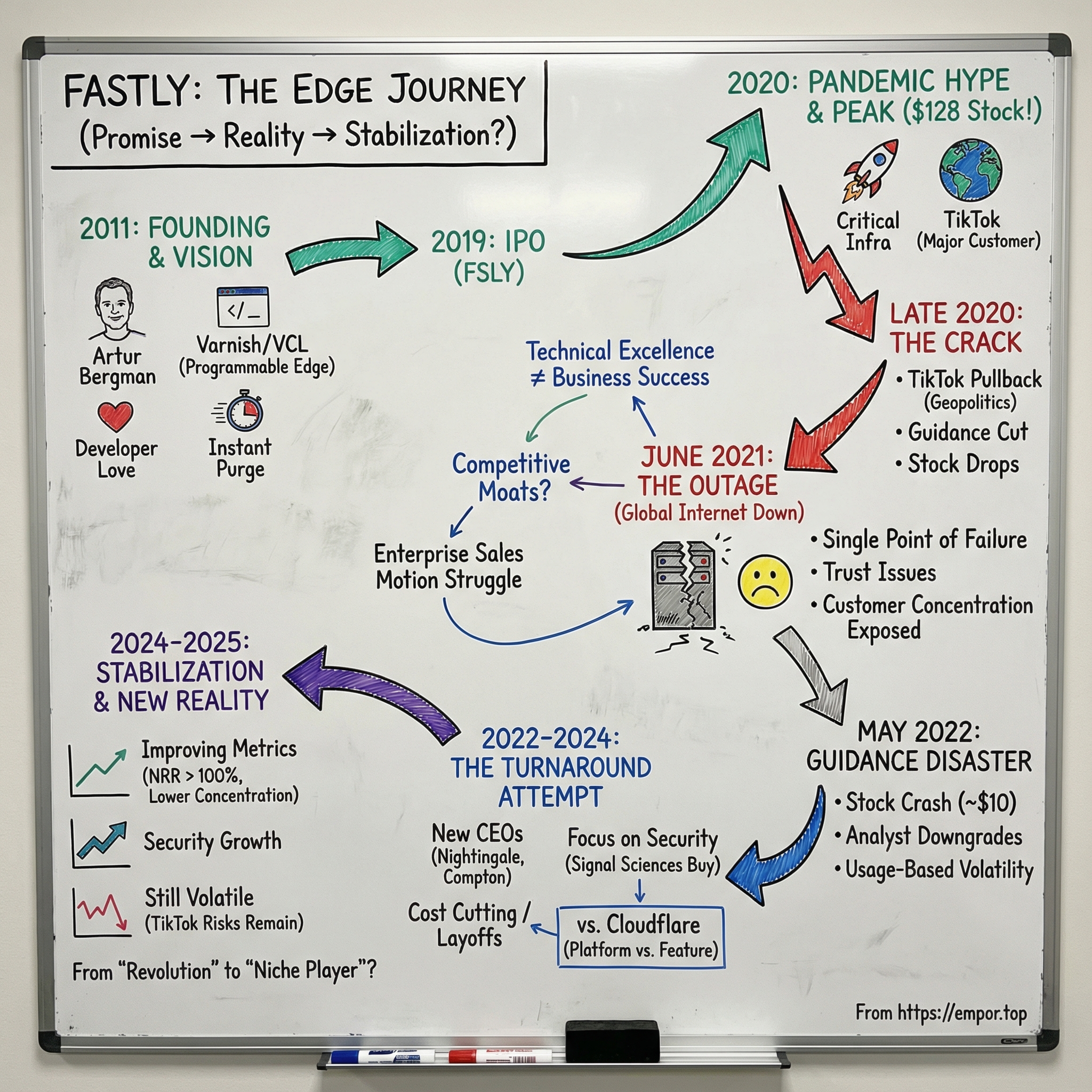

Picture this: October 13, 2020. The world is deep into a pandemic, and the internet has become civilization’s primary nervous system—work, school, entertainment, everything riding on a few unseen layers of infrastructure. On that day, a San Francisco company called Fastly hits an all-time high of $128.83 a share.

Most people had never heard of Fastly a few months earlier. But in the market, it was suddenly everywhere: a developer-loved edge computing and CDN company turned must-own pandemic winner, swept up by momentum traders and tech-focused hedge funds. In 2020 alone, the stock had risen more than 300%.

Now jump to late 2025. Fastly trades around $10 a share. On December 19, 2025, it closed at $10.23—down more than 90% from that peak.

So what happened? How did a company that felt like critical internet infrastructure—so essential that when it went down, huge chunks of the web went down with it—go from $120-plus to single digits? How did a developer-beloved pioneer in programmable, real-time delivery fail to turn that importance into durable business success?

That’s the heart of this story: the gap between technical excellence and commercial execution. The dangers of customer concentration. The double-edged sword of usage-based pricing. And the unforgiving physics of infrastructure markets, where competitors are massive, margins are hard-won, and “good enough” gets bundled into platforms you can’t easily fight.

The plot has everything: a Swedish-American founder pushed to the edge of patience by legacy CDNs, a TikTok-fueled hype wave that set expectations on fire, a high-profile outage that made Fastly famous for the worst possible reason, and guidance cuts that shattered investor confidence. Along the way, we’ll unpack why Cloudflare executed a similar vision more effectively, why hyperscalers loom over standalone infrastructure companies, and whether Fastly’s turnaround effort under new leadership can still salvage what the company set out to build.

II. The CDN Wars & Pre-History: Understanding the Battlefield

To understand Fastly, you first have to understand the world it tried to break into: a part of the internet most people never think about, dominated for years by a few giants, and shaped by one brutal constraint—physics.

In the late 1990s, the web had a basic architectural problem. Most sites lived on a single “origin” server. If you were far away from that server, your page loads were slow because the data had to travel farther. If a big news event hit and traffic spiked, the origin got crushed. Latency and downtime weren’t edge cases. They were the default.

Akamai Technologies was founded in 1998 by Daniel Lewin, Tom Leighton, and others out of MIT, based on research from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. Their breakthrough was simple to explain and hard to execute: put servers all over the world, cache content on them, and serve users from the closest possible location. If someone in Tokyo wanted a page hosted in San Francisco, they wouldn’t have to wait for packets to cross the Pacific—they’d get a nearby copy.

That model worked. Akamai more or less invented the CDN category and then spent the next two decades owning it.

The 2000s brought expansion and consolidation. Akamai cemented its dominance, buying competitors like Speedera and Globix. Limelight Networks, founded in 2001, emerged as a meaningful alternative, especially in media.

The scale difference over time tells you why Akamai was so hard to dislodge. In its 1999 10-K, Akamai reported nearly $4 million in annual revenue and about 3,000 servers globally. By 2016, Akamai reported more than $2.3 billion in revenue and said it managed around 200,000 servers.

But success bred a certain kind of stagnation, and the “legacy CDN” model started to feel increasingly out of step with how modern software teams operated. Three friction points mattered most:

Configuration rigidity: Changing CDN settings often meant going through support teams and then waiting hours or days for updates to propagate. As continuous deployment and rapid iteration became the norm, this started to feel absurd.

Enterprise sales motions: Traditional CDNs were sold like classic enterprise software—multi-year contracts, opaque pricing, and heavy sales processes. That fit Fortune 500 procurement. It didn’t fit the new wave of developer-led, self-serve internet companies.

Cache purge latency: When content changed, clearing stale cached versions across the network could take minutes or even hours. Fine for mostly static pages. Painful for real-time, dynamic applications.

Then the next wave of competitors showed up.

In 2010, Cloudflare attacked the market from a different angle: combine CDN with security—especially DDoS protection—wrap it in a low-cost offering, and make adoption frictionless with a freemium model. Instead of selling to a handful of huge enterprises, Cloudflare pulled in millions of smaller sites that never would’ve talked to Akamai in the first place.

At the same time, the hyperscalers started quietly turning CDN into a checkbox. AWS CloudFront, Google Cloud CDN, and Azure CDN bundled delivery into their cloud platforms. For customers already running workloads in those ecosystems, “good enough” delivery became just another line item—easy to turn on, easy to manage, and tightly integrated with the rest of their stack.

By 2011, the board was set: Akamai still owned the high end, Cloudflare was racing up from the bottom, and the cloud giants were making CDN feel less like a product and more like a feature.

And yet there was a gap. A space for a CDN designed around how developers actually wanted to work: self-serve, transparent, instantly configurable—and not just faster delivery, but real-time programmability at the edge.

That gap is where Fastly was born.

Enter Artur Bergman, and a piece of technology called Varnish.

III. The Founding Story: Artur Bergman's Vision (2011)

Fastly was founded in 2011 by Artur Bergman, a Swedish-American entrepreneur who’d just spent years living inside the kind of problem most people never see: how do you keep a global, user-generated website fast when everything is changing all the time?

Before Fastly, Bergman was CTO at Wikia (now Fandom), the commercial wiki platform founded by Wikipedia’s Jimmy Wales. Wikia had Wikipedia-like scale and complexity, but not Wikipedia-like resources. Pages weren’t just being viewed; they were constantly being edited, updated, and re-linked by communities around the world. That dynamic nature is exactly where traditional CDNs—built for caching mostly static content—started to crack.

And Bergman had plenty of context for why. His career had been a tour through early web infrastructure: engineering management roles at Fotango (a Canon Europe subsidiary), Six Apart, and then leadership at Wikia from 2007 to 2011, where he moved from manager to VP to CTO. By the time he hit the CDN problem at Wikia, he wasn’t coming at it as an outsider with a slide deck. He’d already spent years in the trenches of scaling internet services.

What drove him crazy wasn’t that CDNs were useless. It was that they were slow to change.

When you’re running a real-time site, “cache invalidation” isn’t an academic computer science joke—it’s the difference between users seeing the right information and seeing yesterday’s internet. But legacy CDN workflows often meant waiting minutes, hours, or longer for configuration changes to propagate or purges to complete. That pace might have been tolerable in the era of static homepages and weekly deploys. It was ridiculous in a world moving toward continuous deployment.

So Bergman built what he wished existed: instant purge, real-time configurability, and deep programmability—so developers could control delivery the way they controlled code. As he described it, the approach dramatically improved performance around the world, pushing page loads down to roughly 150 milliseconds.

The founding insight was simple and ambitious: treat the edge like software. Push a change, and it should be live essentially immediately. No ticket queues. No waiting for a vendor. No “we can roll that out next week.”

Technically, Fastly’s foundation was Varnish Cache, an open-source HTTP accelerator built for speed. And the real magic lever was VCL, the Varnish Configuration Language. VCL gave sophisticated developers the ability to customize caching logic and request handling with a level of control that traditional CDNs generally didn’t offer. Over time, that programmability would become Fastly’s calling card: not just a faster pipe, but a platform you could shape.

Fastly officially launched in July 2011 with seven employees and a mission to make web experiences faster.

As the company grew, that original developer-first DNA stayed front and center. Fastly invested heavily in the things engineers actually care about: clear documentation, well-designed APIs, and a culture of transparency. The team wrote detailed technical posts, contributed to open source, and engaged with developers like peers, not targets.

Bergman also emphasized values in the way the company grew—focusing on transparency, integrity, inclusion, and building a diverse workforce he believed would help attract diverse talent and build better technology for a broad customer base.

That combination—serious technical control plus a “built by developers, for developers” posture—pulled in exactly the kind of early customers you’d expect. Stripe, Twitter, GitHub, and other developer-centric companies chose Fastly. Media brands like The New York Times and The Guardian used it for delivery. High-traffic e-commerce businesses valued the instant purging because it meant pricing, inventory, and product updates could be reflected immediately, not whenever the cache felt like catching up.

The bet was clear: build the best product for the most demanding users, and the revenue will follow.

That thesis had worked in other developer-led categories. The open question was whether it could work here—inside infrastructure, where the economics are harsher, the competitors are enormous, and “best product” doesn’t automatically translate into durable advantage.

IV. Building the Product & Finding Product-Market Fit (2011-2016)

Fastly’s early product work wasn’t an incremental upgrade on the legacy CDN playbook. It was a rethink of what a CDN should feel like for modern engineering teams: fast to change, transparent, and programmable.

The signature feature was instant purging. Where traditional CDNs could take anywhere from half an hour to an hour to reliably clear cached content around the world, Fastly could do it in roughly 150 milliseconds. That sounds like a nice-to-have until you’re a newsroom publishing breaking updates, an e-commerce site changing prices and inventory, or a gaming company pushing live scores. In those businesses, “the cache will catch up eventually” isn’t a product feature. It’s a bug.

The other pillar was VCL, the Varnish Configuration Language. Fastly leaned into Varnish Cache as the technical foundation, and VCL became the control surface. Developers could write logic that ran at the edge—deciding how requests should be handled, what should be cached, how traffic should be routed, even how content might be transformed—without constantly bouncing back to the origin. It was edge computing before “edge computing” became the buzzword every infrastructure company stapled onto their deck.

Fastly’s service also looked different operationally. It followed a reverse proxy model: customer traffic flowed through Fastly’s servers, and content was pulled from the customer’s origin and cached in Fastly’s points of presence to reduce latency. Customers didn’t have to “upload files to the CDN” in the old sense. Fastly sat in the request path and made the whole system faster and more controllable.

Out of that product DNA, the ideal customer profile basically selected itself. Fastly naturally attracted high-traffic companies with engineering-forward cultures—teams that wanted control, could use it, and were allergic to waiting on vendor ticket queues. Media companies with huge archives and constant publishing cadence. Developer-centric tech companies. E-commerce businesses with dynamic pages and real-time updates.

And as those customers came in, the pitch sharpened. Fastly wasn’t just “a faster CDN.” It was a programmable edge platform. You weren’t buying delivery; you were buying the ability to change how delivery worked, on the fly.

The business model matched the product: usage-based pricing. The more traffic you pushed through Fastly’s network, the more you paid. That’s elegant when things are going well—customer growth turns into Fastly growth, and existing accounts can expand quickly without a big renegotiation. But it’s also fragile. Usage can drop for reasons that have nothing to do with Fastly: shifts in a customer’s business, a product change, a traffic mix change, or a platform decision.

As the company scaled toward the public markets, the headline picture looked strong: rapid growth, real customers, and a network that had expanded into dozens of points of presence serving massive volumes of requests each month. But Fastly was also spending heavily to build that network and organization, and it showed up in losses alongside the growth.

Fundraising helped fuel the buildout. In June 2013, Fastly raised $10 million in Series B funding. In April 2014, it acquired CDN Sumo, a CDN add-on for Heroku. In September 2014, Fastly raised $40 million in Series C funding, followed by a $75 million Series D round in August 2015. In September 2015, Google partnered with Fastly and other CDN providers to offer services to its users—a meaningful stamp of legitimacy, and a reminder that even hyperscalers sometimes chose partnership over pure competition.

Each round brought more capacity: more network expansion, more engineering, more go-to-market. But the company’s early success also revealed the shape of its future problem.

Fastly’s developer-first approach worked brilliantly when the buyer and the user were the same person: an engineer who loved control, could write VCL, and wanted real-time change management. Enterprise IT was a different world. Many large organizations didn’t have teams ready to author edge logic or debug complex configurations. Selling to developers was one motion; selling to enterprises was another entirely.

And the comparison with Cloudflare started to matter. Fastly optimized for power users. Cloudflare optimized for distribution. Cloudflare’s freemium model pulled in millions of smaller sites, creating a massive top-of-funnel it could later convert into bigger contracts and broader platform adoption. Fastly’s developer-first purity built deep love with sophisticated teams—but it didn’t automatically create the breadth that wins infrastructure markets over the long haul.

V. The IPO and Public Company Transition (2017-2019)

By 2019, Fastly had done the hard part: it had proven the product worked, won logos that engineers bragged about, and built a real network. The next step was the one that changes a company’s metabolism overnight—going public.

Fastly published its IPO prospectus on April 19, 2019. A few weeks later, it updated investors on the expected price range: roughly the mid-teens per share. When the dust settled, Fastly priced at the top of that range, selling 11.25 million shares at $16 each and raising about $180 million.

Then the market did what the market loves to do in a hot IPO window: it bid the stock up immediately. Fastly opened trading under the ticker FSLY at $21.50 and finished the day at $23.99—nearly 50% above the IPO price.

The timing didn’t hurt. 2019 was the year of the tech IPO parade—Lyft, Pinterest, Uber, Zoom, and CrowdStrike. Investors were eager to own the “picks and shovels” of the internet. Fastly’s story fit neatly into that narrative: the modern, developer-friendly alternative to legacy CDNs, positioned for a future where more application logic would move to the edge.

On paper, the business looked like a classic high-growth infrastructure company. In 2018, Fastly generated $144.6 million in revenue and posted a $30.9 million net loss. Revenue was up nearly 38% year over year, and losses narrowed slightly. Growth was there. Profitability, not yet.

The S-1 also made the company feel very real—because it was. Fastly had 489 employees as of March 31 and 1,621 customers, including 243 “enterprise customers,” meaning organizations that had delivered more than $100,000 of revenue over the prior twelve months. And the customer roster read like a modern internet index: Hulu, Microsoft, The New York Times, Spotify, Wayfair.

But inside that impressive list was the first glimpse of a structural risk. A meaningful portion of revenue came from a small number of large customers. When usage-based pricing is your engine, that kind of concentration isn’t just a footnote—it’s a lever your customers can pull.

Fastly’s public-market pitch revolved around three big ideas: the shift from legacy CDNs to real-time edge computing, a developer-centric go-to-market motion, and a huge total addressable market as more software moved closer to users. The bet was that Fastly’s technical advantage would carry it into a much larger business.

And that’s where being public starts to change the game. You don’t get rewarded for being beloved by engineers. You get rewarded for scaling—predictably—quarter after quarter.

In February 2020, Artur Bergman stepped down as CEO and became chief architect and executive chairperson. Joshua Bixby, Fastly’s president and a six-year veteran of the company, took over as CEO.

The company framed it as a natural division of labor: Bergman would focus on what he was best at—technical vision, including edge compute and security—while Bixby drove sales execution and growth. Or, as Bergman put it, it was a chance for each of them to spend more time on what they were “really good at and passionate about.”

Fastly was also widening its ambitions beyond being “just” a CDN, pushing deeper into security and edge compute. Those adjacencies opened bigger markets—but they also pulled Fastly into more direct, more expensive competition with Cloudflare, Akamai, and the hyperscalers.

The question hanging over Fastly as a newly public company wasn’t whether the technology was real. It was whether Fastly could scale an enterprise sales machine without losing the developer-first DNA that made the product special in the first place.

The next few years would give a very loud answer.

VI. The TikTok Moment: Peak Hype (2020)

The pandemic didn’t just change daily life. It rewired the internet.

Over a matter of weeks in early 2020, the world moved into Zoom calls, streaming queues, online classrooms, curbside pickup, and doomscrolling. Traffic surged everywhere, all at once. And if you were a company that sat in the middle of that firehose—moving bytes closer to users, shaving milliseconds, keeping video smooth—this was the kind of demand shock you only get once in a generation.

Fastly was perfectly positioned to ride it.

Wall Street noticed. Fastly became one of the market’s standout pandemic winners, with the stock rocketing upward through the year. And the operating results gave bulls plenty of ammo. In Q2 2020, Fastly reported revenue of $74.7 million, up 62% from a year earlier, beating expectations. Adjusted earnings beat as well, and management raised its full-year revenue forecast. Analysts bumped targets. The “edge computing” narrative suddenly had real numbers behind it.

Then, in the middle of all that celebration, Fastly said the quiet part out loud.

On the earnings call, CEO Joshua Bixby disclosed that TikTok was Fastly’s largest customer—accounting for about 12% of revenue in the first half of 2020. For investors, it was the kind of detail that instantly changes the story. This wasn’t just “benefiting from streaming.” This was “meaningfully dependent on one app.”

And it landed at the worst possible moment. The Trump administration was publicly threatening to ban TikTok in the U.S. unless ByteDance sold it to an American company. Overnight, Fastly’s growth narrative got stapled to geopolitics.

Bixby tried to thread the needle: acknowledge the risk without sounding like the business was a house of cards.

"Any ban of the TikTok app by the US would create uncertainty around our ability to support this customer," he said on the call. Fastly believed it could “backfill the majority of this traffic” if needed, but he was clear about the reality: losing that traffic would still hit the business. Meanwhile, Fastly reminded investors it served plenty of other major customers too—Shopify, Spotify, Slack—names that signaled this wasn’t a one-trick pony.

The market didn’t care. The stock dropped sharply the next day, not because Fastly had a bad quarter, but because it had a single point of revenue failure.

From there, the chart started moving with the news cycle. When ban headlines hit, Fastly sold off. When talk of a deal or a reprieve appeared, it rallied. The company’s fate—at least in the public imagination—was suddenly tethered to forces it couldn’t control.

And still, the hype won. Growth investors and momentum traders kept piling in. The story was too seductive: Fastly was “critical internet infrastructure,” pandemic digitization wasn’t going to reverse, and edge computing was a mega-trend. By October 2020, the stock peaked above $128 a share.

But the TikTok risk wasn’t theoretical.

Later in 2020, Fastly cut its revenue forecast for the third quarter and noted ByteDance was spending less. In a shareholder letter, Fastly said ByteDance had “removed a majority of their U.S. and non-U.S. traffic from our platform” by the end of Q3. Fastly added that, based on publicly available information, it believed the reduction was in response to the possibility of U.S. companies being prohibited from working with ByteDance.

In other words: the thing investors feared was already happening.

By late 2020, ByteDance had pulled most of its traffic from Fastly’s platform. The same concentration that had juiced growth on the way up now worked in reverse—one customer decision suddenly erased a meaningful amount of revenue visibility.

The TikTok moment exposed a core fragility in Fastly’s model. Usage-based pricing is amazing when customers expand. But when a single customer is a large chunk of your usage—and that usage is tied to political negotiations between superpowers—your revenue isn’t just volatile. It’s hostage to the headlines.

VII. June 2021: The Outage That Broke the Internet

At around 9:50 UTC on June 8, 2021, Fastly suffered a major outage across its global CDN—one that quickly spilled into public view.

Because this wasn’t a niche service blipping out. Internet users around the world woke up to what felt like the web itself breaking: Amazon, Reddit, The New York Times, The Guardian, CNN, Twitch, Spotify, and even the UK government’s homepage. People weren’t seeing subtle slowdowns. They were getting hard errors like “503 Service Unavailable” and “connection failure,” and they were getting them everywhere.

For most consumers, this was the first time they’d ever heard of Fastly. The irony is that this is exactly how infrastructure companies become famous: not when things work, but when they suddenly don’t. Overnight, Fastly went from behind-the-scenes plumbing to front-page news.

Fastly would later explain what happened with blunt clarity:

We experienced a global outage due to an undiscovered software bug that surfaced on June 8 when it was triggered by a valid customer configuration change. On May 12, we began a software deployment that introduced a bug that could be triggered by a specific customer configuration under specific circumstances. Early June 8, a customer pushed a valid configuration change that included the specific circumstances that triggered the bug, which caused 85% of our network to return errors.

The cause was almost painfully ordinary. A software update deployed on May 12 introduced a latent bug. Weeks later, a single customer made a routine, valid configuration change that happened to hit the exact edge case. That was enough to send roughly 85% of Fastly’s network into failure mode.

It’s hard to imagine a cleaner demonstration of how fragile modern internet dependencies can be: one bug, one configuration push, and suddenly a huge slice of the internet is throwing errors.

Fastly moved fast. The company described the outage as “broad and severe,” but said it identified, isolated, and disabled the issue quickly. Within 49 minutes, most of its network was back up.

And then came the part Fastly is, culturally, built to do: the postmortem. Nick Rockwell, SVP of Engineering, published a detailed, technical explanation of the incident—what changed, what triggered it, how they mitigated it, and what would be done to prevent repeats. The tone wasn’t defensive. It was direct, apologetic, and very developer-native:

Even though there were specific conditions that triggered this outage, we should have anticipated it. We provide mission critical services, and we treat any action that can cause service issues with the utmost sensitivity and priority. We apologize to our customers and those who rely on them for the outage and sincerely thank the community for its support.

The broader media takeaway was just as important as the technical one: concentration risk. Commentators pointed out that a small number of companies now sit under an enormous amount of internet activity. When one of them goes down, it doesn’t feel like “a vendor had an incident.” It feels like the internet is wobbling.

For Fastly, the moment was deeply paradoxical.

On one hand, it was proof of importance. If an outage at Fastly could take down this much of the web, then Fastly really was critical infrastructure.

On the other hand, it raised the most uncomfortable question possible for an edge network: can we rely on you?

It also exposed a split in customer outcomes. Some companies had designed for redundancy; others hadn’t. Two widely discussed examples were Reddit and The New York Times—both used Fastly as the sole CDN for their primary site domains, but Reddit was impacted throughout the outage while The New York Times was not.

More broadly, customers using multiple CDNs tended to get hit less hard and recover faster, because they could fail over. Customers using Fastly as their single CDN could go fully dark. Some could redirect traffic back to origin servers, but doing it manually still meant more downtime.

That detail mattered enormously for Fastly’s business. Multi-CDN resilience is great operational advice for customers—but strategically, it’s not what a CDN provider wants to teach the market. It nudged buyers toward a simple conclusion: don’t rely on any single CDN, no matter how good it is.

The developer community largely gave Fastly credit for transparency and speed. But developers don’t always control the budget. In enterprise sales conversations, the outage became a credibility hurdle. CIOs and IT directors were suddenly asking the kind of questions that slow deals down: what’s the blast radius, what’s the failover story, and what happens to our most critical application if you’re the one having the bad day?

And for Fastly, coming off the TikTok whiplash, it was another reminder that being “central to the internet” is not only a compliment. It’s a liability, too.

VIII. The Billings Guidance Disaster (May 2022)

If the outage was a blow to trust, what came next was a blow to the core story Fastly sold to Wall Street: predictable growth.

Fastly’s quarterly results themselves weren’t the kind that normally cause a meltdown. The real damage came from management pulling down full-year guidance again—two quarters in a row—while acknowledging that demand from its biggest customers was softening. The message between the lines was hard to miss: even when the product is solid, the revenue can move in ways Fastly can’t easily control.

That triggered a brutally pragmatic response. Fastly announced a restructuring to take costs out of the business. Analysts read it as a company trying to protect near-term financials in a way that risked starving the very growth narrative that had once justified the valuation.

Morningstar, for example, cut its fair value estimate in half, from $10 to $5, and flagged the stock as “Very High” uncertainty. The broader analyst community followed with price target cuts. The stock—already down dramatically from its 2020 peak—slid deeper into single digits. The market wasn’t debating the nuance. It was repricing the entire risk profile.

And the postmortem wasn’t just, “one customer left.” The guidance disaster made a set of deeper problems impossible to ignore:

Customer concentration remained severe: Even after TikTok reduced usage, Fastly still relied heavily on a small number of very large customers. When one of them pulled back—because of macro pressure, internal optimization, or building more in-house—the impact hit immediately, quarter-to-quarter.

Enterprise sales motion wasn’t working: Fastly had built love with sophisticated engineering teams. But scaling that into classic enterprise procurement—long cycles, committees, checklists, and vendor consolidation—meant competing head-on with Akamai’s entrenched relationships and Cloudflare’s widening platform. Fastly didn’t yet have the sales machine or the simplified “package it and roll it out” product story that enterprise buyers tend to reward.

Competitive dynamics were worsening: Cloudflare kept expanding its catalog and pricing aggressively. Meanwhile, AWS CloudFront and other hyperscaler CDNs kept getting better—often “good enough,” and often bundled into spend customers were already committed to. Fastly’s position as the premium, programmable CDN started getting squeezed from the top and the bottom.

Usage-based pricing created real volatility: The model that made Fastly feel aligned with customer success in good times became a trap in bad times. There was no subscription floor to smooth out customer pullbacks. When customers optimized traffic, Fastly felt it immediately.

Gross margin pressure: Fastly wasn’t a high-margin software business wearing an infrastructure costume. It was infrastructure. Bandwidth, colocation, hardware, and network operations kept gross margins in the mid-50s to low-60s range, making it harder to generate the kind of operating leverage public-market investors love.

For years, the bull case had been simple: Fastly would grow into its valuation by turning technical differentiation into market share in a growing edge future. After May 2022, the bear case took over: maybe the market was structurally stacked against them—and maybe no amount of engineering excellence could change that.

IX. The Turnaround Attempt & Continued Struggles (2022-2024)

By mid-2022, Fastly didn’t just need a better quarter. It needed a different kind of company.

So the board went shopping for something Fastly had never really been: enterprise-first, operationally tight, and built to sell at scale. In September 2022, Fastly announced that Todd Nightingale would become CEO.

Nightingale came from Cisco, where he led its Enterprise Networking and Cloud business as Executive Vice President and General Manager—running strategy and development for a multi-billion-dollar portfolio. Before that, he ran Cisco’s Meraki business, the cloud-managed networking platform Cisco acquired in 2012, and helped turn it into one of Cisco’s standout franchises. His reputation was as a product-minded operator who could translate technical value into simple, scalable adoption across businesses, schools, and governments.

The hire made the board’s priorities plain: credibility with large enterprises, a sharper go-to-market motion, and more rigor in how the business was run. The logic was straightforward: if Fastly’s core problem was execution—especially enterprise sales—then bring in someone who had already built that muscle at a global scale.

Nightingale replaced Joshua Bixby, who stepped down as CEO and from the board, but stayed on as an adviser.

The timing was telling. Nightingale’s arrival was announced alongside Fastly’s Q2 2022 results. Revenue was $102.5 million, up 21% year over year and roughly flat from the prior quarter. Guidance pointed to only modest sequential growth for Q3, and full-year revenue was expected to land in the low-$400 millions.

Analysts weren’t just looking at the top line. They were looking at the engine underneath it. GAAP gross margin came in at 44.9%, down from 52.6% a year earlier, and Fastly was still losing money.

And the comparison everyone made—because it was impossible not to—was Cloudflare. In the same quarter, Cloudflare reported $235 million in revenue, growing much faster year over year, and operating at gross margins around 76%. Cloudflare was burning cash too, but it looked like a software platform with infrastructure underneath. Fastly still looked like infrastructure with a platform trying to emerge.

Fastly’s big strategic swing to change that narrative had already been set in motion: the Signal Sciences acquisition, a roughly $775 million bet on modern application and API security. Fastly positioned the deal as a way to combine Signal Sciences’ security products with its edge cloud platform into a unified suite, built in a developer-friendly way, and capable of shortening development cycles while protecting web apps.

There was a clear business logic to it. Security generally carries higher margins than pure delivery. It also expands what you can sell into an account, which is exactly how Cloudflare had been building leverage: make the edge sticky by bundling performance and protection together.

Fastly also disclosed that Signal Sciences brought a meaningful base of enterprise customers—many of them new logos for Fastly—and that the security product line carried gross margins north of 85%. On paper, this was the kind of mix shift that could improve Fastly’s economics and reduce its dependence on raw traffic dollars.

But strategy decks don’t integrate products. Teams do. And in practice, the integration was harder than hoped, with cross-sell synergies taking longer to show up than investors wanted.

Fastly kept trying to strengthen its developer funnel, too. In May 2022, it acquired Glitch, a web coding platform with more than 1.8 million developers—another attempt to feed the top of the pipeline with the kind of builders who had always loved Fastly’s ethos.

Then came more change, more tightening, and more signs that the company was being resized for a smaller, tougher reality. In August 2023, Fastly acquired Domainr, a domain status API provider. In August 2024, it laid off 11% of its workforce. And in December 2024, Fastly issued $150 million in convertible senior notes with a 7.75% yield as part of a major debt restructuring.

From 2022 through 2024, the story was less about bold new frontiers and more about the unglamorous work of survival: restructuring, layoffs, refinancing, and trying to rebuild trust—inside the market, inside customer pipelines, and inside the company itself. Each move made sense in isolation. Together, they painted a picture of a business that had been built for a growth trajectory it never ultimately sustained.

X. Current State & Recent Developments (2024-2025)

By the end of 2024, Fastly was no longer trading on hype. It was trading on whether it could stabilize.

In Q4 2024, the company reported record quarterly revenue of $140.6 million—up about 2% year over year. Management credited the beat to stronger-than-expected seasonal traffic, along with share gains.

For the full year, Fastly finished 2024 at $544 million in revenue, up 7% year over year. That’s a long way from the 40%+ growth investors once expected—but it was also meaningfully better than the near-stall Fastly had battled through 2022 and 2023. The headline takeaway: the business looked like it had found a floor.

Profitability, though, was still the unresolved part of the story. In 2024, Fastly posted a GAAP gross margin of 54.4% (up from 52.6% in 2023) and a non-GAAP gross margin of 57.8% (up from 56.9%). Losses told a split-screen story: the non-GAAP net loss narrowed to $17.2 million from $21.7 million the year before, while the GAAP net loss widened to $158.1 million from $133.1 million.

So yes—some operational improvement. But no—this still wasn’t a sustainably profitable company.

One of the more important shifts was in the customer mix. Fastly ended Q4 2024 with 596 enterprise customers, up 20 from Q3. And the concentration problem that had haunted the company for years started to loosen: the top ten customers represented 32% of revenue in Q4 2024, down from 40% in Q4 2023. That’s still concentrated, but it’s directionally the kind of change Fastly needed—less “one customer sneezes, Fastly catches pneumonia.”

Fastly also took care of a looming balance sheet concern. In late 2024, it refinanced part of its convertible debt: it issued $150 million of 7.75% convertible senior notes due 2028 (with a 100% conversion premium) and used the proceeds to repurchase $158 million in principal amount of its existing 0% convertible notes due 2026 for about $0.95 on the dollar. The move bought time and reduced near-term maturity pressure, but the cost of that flexibility was obvious: a 7.75% coupon is a very different world than 0%.

Around the same period, Fastly highlighted external validation too: it was named a Leader in the IDC MarketScape: Worldwide Edge Delivery Services 2024 Vendor Assessment (November 2024), the second time it received that designation.

Then, in mid-2025, another shoe dropped: another CEO transition.

Fastly announced that Kip Compton—who had joined in January 2024 as Chief Product Officer—was appointed CEO and named to the board, effective immediately. He succeeded Todd Nightingale, who stepped down as CEO, President, and Director. Nightingale stayed on as an advisor through June 30, 2025, and then pursued an external opportunity.

Fastly framed Compton as a product-and-growth leader with more than 25 years of senior experience across cloud, video, and networking. And internally, it made a certain kind of sense: after years of restructuring and refinancing, the company wanted a leader who could turn portfolio strategy into a clearer product story and a tighter growth engine.

But externally, it inevitably raised the question: why another reset? Nightingale had been brought in to professionalize the enterprise motion. His departure after less than three years suggested either that the turnaround was harder than expected, or that the board wanted a different approach.

The next data point arrived quickly—and it was the most encouraging one Fastly had delivered in a while.

In Q3 2025, Fastly reported total revenue of $158.2 million, up 15% year over year. Network services revenue was $118.8 million, up 11%, and security revenue was $34.0 million, up 30%. Even more striking, Fastly posted record operating income of $11.6 million—well above its $1 million guidance midpoint—and record quarterly free cash flow of $18 million.

Investors responded the way they always do when an infrastructure company shows real operating leverage: the stock jumped on the results. Still, it was rallying from a much lower base than the 2020 era.

And then the old ghost reappeared, because of course it did: TikTok.

Executives warned that regulatory shifts could still affect the business, specifically actions from the Trump administration related to TikTok and its parent, ByteDance—one of Fastly’s largest customers. On June 19, the Trump administration issued an executive order extending TikTok’s deadline to comply with the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act to September 17. The act—signed by President Joseph Biden and originally intended to go into effect in January—effectively prohibits TikTok’s use in the U.S. while it remains owned by a Chinese company.

Fastly tried to put numbers around the risk. As CFO Ron Kisling said, “Globally, ByteDance, the parent company of TikTok represented less than 10% of our revenue in the second quarter of 2025 and the United States traffic represented less than 2% of our revenue in the same period.”

The irony is hard to miss. Years after TikTok helped inflate Fastly’s story to peak hype—and years after TikTok-driven volatility helped puncture it—ByteDance was still there in 2025. Smaller than before, but still big enough to drag Fastly back into the headlines whenever Washington moved the goalposts.

In other words: Fastly was showing signs of operational progress. But some of the same structural tensions—customer concentration, usage volatility, and geopolitical exposure—still hadn’t fully let go.

XI. Technology Deep Dive: What Makes Fastly Different?

Fastly’s differentiation has always been rooted in how it built the edge: not as a generic network of small caches, but as a set of high-capacity points of presence designed to do more work, hold more content, and respond faster.

One way Fastly tells that story is time to first byte—how quickly a user gets the first response from a site. Fastly has said it sees meaningfully faster TTFB than other CDNs on average, and that sites migrating from Cloudflare to Fastly have shown faster median TTFB, while the reverse move shows slower median TTFB. The claim isn’t that every customer magically gets a speed boost overnight. It’s that Fastly’s architecture can win on performance when you’re running sophisticated, latency-sensitive workloads and you know how to tune the system.

Performance: Fastly emphasizes high-throughput, high-capacity POPs that can keep more content in cache for longer. That typically means fewer trips back to the origin and quicker responses at the edge—especially for demanding, high-traffic applications.

Configurability: This is where Fastly’s developer reputation really comes from. VCL plus configuration APIs give teams granular control over caching and request handling. If you want custom caching rules, traffic shaping, or complex edge logic, Fastly is built to let you do it without waiting on a vendor ticket.

Instant purge: Fastly’s instant purge—about a 150-millisecond global average—remains one of its cleanest, most concrete advantages. For news, e-commerce, and any workflow where “right now” actually matters, being able to invalidate cached content across the world almost immediately is a real capability, not marketing gloss.

Fastly also rounds out the platform with features that matter to modern delivery: semantic web caching, support for the UDP-based HTTP/3 protocol, and media capabilities like DRM-enabled delivery, encryption, and secure tokens to restrict access. As of March 2024, Fastly said it was transferring 336 Tbps of data—an indicator of just how much traffic the network can handle at scale.

Protocol support: Fastly has invested in staying on the front edge of web standards, with HTTP/3 support and strong media-delivery primitives that matter for streaming and controlled distribution.

But here’s the catch—and it’s the theme of this entire story. Technical advantage doesn’t automatically become business advantage.

For a lot of enterprises, the buying decision isn’t “best-in-class edge configurability.” It’s “good enough performance, packaged with security, bundled with our cloud, and simple to run.” That reality shows up in the economics.

Fastly’s gross margins have sat far below Cloudflare’s. And that gap matters because it hints at something structural: either Fastly’s network costs are higher, its pricing power is lower, or both. In a category where competitors can bundle, cross-subsidize, and sell platforms instead of point products, that margin disadvantage makes it much harder for Fastly to generate the kind of operating leverage public investors expect—even when revenue grows.

XII. The Business Model & Unit Economics Analysis

Fastly’s model has a few structural traits that help explain why the company can look great on a product demo and still feel fragile in the numbers.

Usage-based pricing: Fastly gets paid when customers push traffic through its network. In good times, that’s beautifully aligned: customers grow, and Fastly grows right alongside them. In bad times, it cuts the other way. If a customer optimizes bandwidth, shifts traffic elsewhere, gets hit with macro headwinds, or builds more in-house, Fastly feels it immediately—no annual subscription floor to soften the blow.

That’s why you’ll hear skeptics frame it bluntly, especially with a customer like TikTok in the mix:

I'm not a personal investor in Fastly, because of the fact that it's a revenue model that's based on usage. And when you're trying to predict usage from large customers like TikTok, it's naturally going to be really volatile here. The only way they keep their dollar-based net retention rate greater than 130%, which is about where investors have anchored expectations for Fastly, is by increasing usage and upselling their current customers.

In other words: when expectations are set around high retention and expansion, the company needs customers not just to stick around, but to keep sending more and more traffic—or to buy more products. Any pause shows up fast.

Customer concentration: Even after progress, Fastly still gets a meaningful share of revenue from a small set of whales. The top ten customers still make up roughly a third of revenue, which means a single customer decision can swing results—and those customers have leverage in negotiations.

Infrastructure cost structure: Fastly isn’t a pure software margin story. It pays for bandwidth, colocation, and hardware, and those costs don’t flex down neatly when revenue dips. That’s how you get margin pressure during slowdowns: the cost base is real, and it’s sticky.

You can see all of this playing out in the customer mix. In the second quarter, Fastly said its top ten customers accounted for 31% of revenue, down from 34% in the second quarter of 2024. But the growth split is the more telling part: revenue from the top ten customers grew only 2% year over year, while revenue from customers outside the top ten grew 17%.

That’s the diversification strategy working in one sense—less dependence on a handful of accounts. But it also hints at the tradeoff: if the biggest customers are basically flat while the rest of the base is doing the growing, Fastly may be replacing high-volume traffic with smaller accounts that don’t carry the same scale benefits.

XIII. Competitive Landscape & Market Dynamics

By this point in the story, the competitive picture is hard to ignore: Cloudflare is growing faster than Fastly, with higher net retention and meaningfully better gross margins. And the stock charts tell the same tale. Both Cloudflare and Fastly went public in 2019, but Cloudflare’s shares later rose more than 550%, while Fastly traded about 10% below its IPO price.

Cloudflare didn’t win because it stumbled into CDN at the right time. It won because it executed a similar vision—developer-friendly, programmable delivery with security layered in—but packaged it for far broader adoption. The freemium model created an enormous funnel. The product roadmap expanded relentlessly. And the company built a platform story that enterprise buyers could standardize on, not just a tool engineers admired.

Cloudflare: The existential threat. Cloudflare has built the “everything at the edge” platform Fastly aspired to—CDN plus security plus developer compute—then scaled it with a distribution machine Fastly never had. Today, Cloudflare sits at a vastly larger scale, with dramatically higher margins, and a market cap above $40 billion, versus Fastly at roughly $1 billion.

The result is a brutal reality for Fastly: even if Fastly can be faster in specific performance-sensitive cases, Cloudflare can win deals by being close-enough on performance while being easier to buy, easier to deploy broadly, and easier to justify as a vendor consolidation move.

Both companies are major players in the CDN market, but NET looks like the safer bet today, largely because it has scale, breadth, stronger enterprise traction, and a clearer pathway to monetizing new demand—AI included—in ways that show up in earnings and in analyst estimates.

Akamai, meanwhile, is the proof that incumbents can survive—if they evolve. It operates across CDNs, cybersecurity, and cloud computing, and in CDN it fights the same enemies everyone does: Amazon CloudFront, Google Cloud CDN, Microsoft Azure CDN, and Cloudflare. Cloudflare has been especially aggressive, bundling integrated security and delivery with competitive pricing and solid performance.

Akamai: The incumbent with deep enterprise relationships, a diversified security portfolio, and scale. Akamai has made the hard transition from “CDN company” to “security-and-delivery platform,” with security now the majority of revenue. Fastly can compete on developer experience and certain technical advantages, but it can’t match Akamai’s enterprise sales infrastructure or the institutional lock-in that comes from decades of being on approved vendor lists.

Hyperscalers: AWS CloudFront, Google Cloud CDN, and Azure CDN aren’t trying to be the fanciest CDN on earth. They’re trying to be the easiest. If you already run on that cloud, turning on CDN as another integrated service is often more appealing than running a standalone vendor—especially when procurement, identity, billing, and observability are already tied to the hyperscaler. They don’t have to win on features. They win on bundling and ecosystem gravity.

That “all-inclusive” cloud approach also changed the shape of the market. It pushed many companies toward multi-CDN strategies for resilience and pricing leverage, and in some cases toward moving delivery fully into hyperscaler platforms. At the very top end, it also nudged a different decision: build it yourself.

Larger companies like TikTok or Netflix have enough traffic, engineering talent, and leverage to justify building their own CDNs—pulling some of the most attractive volume out of the third-party market altogether.

Build vs. buy: For the biggest content companies—Netflix, TikTok, and other massive traffic generators—owning the delivery stack can be cheaper and more controllable than renting it. And when those whales build instead of buy, they don’t just leave a vendor. They remove an entire tier of potential high-volume revenue from the addressable market.

XIV. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate to high. Building a true global CDN still takes real capital and operational muscle. But the “hard part” of internet infrastructure is no longer a gated club. The hyperscalers are already in the market, and newer, more focused companies can enter from the side—especially in edge compute and developer platforms—without trying to replicate a full traditional CDN footprint on day one.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate. CDNs live and die by their underlying inputs: bandwidth, colocation, hardware, and interconnection. There are multiple suppliers, and they compete hard for business, so Fastly isn’t stuck with a single choke point. But it also can’t buy at the same scale, or on the same terms, as AWS, Google, or Microsoft—so supplier economics will always be a pressure point.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High. Fastly’s biggest customers have negotiating leverage simply because they’re big. They can demand pricing concessions, push for custom terms, or shift traffic elsewhere. Multi-CDN setups are increasingly common, which makes “switching” less like a one-time migration and more like a traffic allocation decision. And enterprises, especially in tighter budget environments, expect competitive pricing.

Threat of Substitutes: High. For many customers, a CDN is no longer a specialized purchase—it’s a bundled feature inside a cloud platform. Hyperscaler CDNs are often good enough, easier to procure, and easier to operate if the rest of the stack already lives there. And for simpler delivery needs, there’s an abundance of alternatives that get the job done without premium complexity.

Competitive Rivalry: Very high. Fastly sits in the blast radius of multiple well-funded, highly motivated competitors—Cloudflare expanding relentlessly, Akamai defending the enterprise, and the hyperscalers bundling delivery into broader cloud commitments. Pricing pressure is constant, and feature gaps close quickly as the category matures.

Summary: Fastly is fighting in a market where customers have leverage, substitutes are credible, and competition is relentless. That doesn’t mean differentiation is impossible. It does mean sustaining it—and translating it into durable business power—is the hard part.

XV. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Weak. CDNs do benefit from scale, but not in the way software businesses do. More traffic helps, yet bandwidth, servers, and colocation remain real, ongoing costs. And as Cloudflare has shown, you don’t need to be the biggest network to be cost-competitive.

Network Effects: None. Adding more Fastly customers doesn’t inherently make Fastly better for the next customer. This isn’t a social network or a marketplace. It’s infrastructure.

Counter-Positioning: Lost. Fastly’s early posture—real-time control, transparency, built for developers—was a true break from the legacy CDN world. But Cloudflare adopted the same language, shipped its own programmable edge story, and then wrapped it in broader distribution and a wider product suite. The differentiation that once felt like a wedge stopped being one.

Switching Costs: Moderate. Integrating a CDN into your stack takes work, and custom VCL logic can add real friction. But the market has moved toward multi-CDN setups, which turns “switching” into something more like “rebalancing.” Customers can shift traffic away without ripping everything out overnight.

Branding: Weak-Moderate. Among engineers, Fastly has genuine credibility. But that reputation hasn’t consistently translated into enterprise preference or pricing power—especially when competitors can bundle delivery with security, tooling, and procurement simplicity.

Cornered Resource: Weak (eroding). For a while, VCL know-how and early relationships with sophisticated developers looked like a defensible asset. Over time, competing edge platforms—especially Cloudflare Workers—have narrowed the gap and given developers other, more mainstream places to build.

Process Power: Weak-Moderate. Fastly’s developer-friendly culture and real-time architecture are real strengths, and they show up in the product experience. The problem is that the parts competitors need to copy are increasingly copyable, and the parts that aren’t copyable don’t automatically translate into market power.

Summary: Fastly doesn’t have a durable competitive advantage. No single power offers long-term protection against larger, better-distributed, better-capitalized competitors.

XVI. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Fastly’s arc reads like a checklist of what makes infrastructure both thrilling to build and brutal to scale. A few lessons keep showing up, whether you’re founding a company in this space or underwriting one.

Technical excellence ≠ business success: Fastly built technology that engineers genuinely admired. But in infrastructure, “better” doesn’t automatically win. What wins is getting adopted widely, getting bought predictably, and expanding inside accounts—things that depend as much on distribution, go-to-market execution, and product packaging as they do on raw performance.

Developer love vs. revenue: Bottoms-up adoption can be rocket fuel in the right categories. But CDN and edge spending often gets decided in enterprise processes—security reviews, procurement, vendor consolidation—where the loudest voice isn’t always the developer who wants the most control. If the buyer can’t easily understand, standardize, and roll it out, love stays love; it doesn’t always become revenue at scale.

Customer concentration risk: When a single customer becomes a meaningful slice of revenue—and that customer’s decisions are shaped by politics, regulation, or sudden internal optimization—you don’t have a customer. You have a dependency. Diversification isn’t something you do after the first shock. It’s something you build before the business learns what “one customer decision” really feels like.

Usage-based pricing volatility: Usage-based pricing aligns incentives when customers are growing. It also means revenue can drop fast, without warning, for reasons that have nothing to do with product quality. Public markets tend to reward stability, and they punish surprises. Subscription floors, commits, and longer-term contracts don’t just improve forecasting—they reduce existential quarter-to-quarter fragility.

Competitive moats in infrastructure: In this market, moats rarely come from being a little faster. They come from scale economics, bundling into broader platforms, and distribution engines that make adoption effortless. A performance edge can be real and still not be defensible if competitors can match it “well enough” and beat you everywhere else that matters.

The enterprise transition: Selling to developers is one motion. Selling to enterprises is another. It requires different product choices (simplicity and standardization, not just flexibility), different support expectations, and a different kind of sales organization. Many companies stumble here—not because their tech stops working, but because the company they need to become is not the company that got them there.

XVII. Bear Case vs. Bull Case

The Bear Case

Fastly is fighting the hardest kind of fight: staying independent in a market that keeps turning its core product into a commodity. It can’t match Cloudflare’s “one vendor for everything at the edge” platform, and it can’t win a price war against hyperscalers that treat CDN as an add-on to a much larger cloud bill.

That leaves Fastly squeezed. Customer concentration means revenue can still swing when a handful of large accounts change behavior. And because this is an infrastructure business, costs don’t magically fall when usage does—making margin expansion a slow, stubborn grind. The enterprise sales motion has also been an unfinished project, even as leadership has changed more than once. And the bigger narrative Fastly once rode—edge computing as the next inevitable platform shift—hasn’t shown up at scale in a way that reliably lifts all boats.

In this view, Fastly doesn’t blow up overnight. It just gradually loses mindshare and leverage, while continuing to burn cash in a market that rewards size, bundling, and distribution.

The Bull Case

The bull case starts with a simple mismatch: Fastly is priced like a broken story, but it still owns real technology that serious engineers respect—and it has a security business that’s growing.

From that base, a cleaner product story and better go-to-market execution could matter a lot. If the leadership team can translate Fastly’s strengths into a tighter enterprise pitch—performance plus security plus edge compute, packaged in a way buyers can standardize on—then the company doesn’t need to win the whole market. It just needs to win the right slice of it and do so more predictably.

And there’s still optionality. Edge computing could prove out more broadly over time, and Fastly’s early investment could pay off if meaningful workloads move closer to users. Or the outcome could be even simpler: an acquirer—private equity, Akamai, or an enterprise software company—decides the assets are undervalued and buys Fastly at a modest premium.

The Realistic Case

The most likely outcome lives between those extremes. Fastly remains independent as a niche player that serves sophisticated, developer-centric customers—or it gets acquired, but not at anything like the 2020-era valuation.

Growth settles into the single digits. Profitability comes, not through a sudden demand wave, but through cost discipline and gradual mix improvement. The best-fit customers stay loyal because Fastly is genuinely good at what it does. But the biggest share of the edge platform opportunity goes to competitors with more capital, broader product suites, and stronger distribution.

XVIII. Key Metrics & What to Watch

If you’re trying to answer the only question that matters—“is Fastly actually getting healthier?”—three metrics tell you more than almost anything else:

Net Revenue Retention (NRR): This is the pulse of a usage-based business. Are existing customers sending more traffic and buying more over time, or are they quietly optimizing, shifting traffic away, and shrinking? An NRR below 100% means the base is contracting, which is how a usage-driven model can slip into a slow-motion death spiral. The move up to 104% is a good sign—but it only matters if it holds.

Top 10 Customer Concentration: This is Fastly’s recurring nightmare in a single number. The lower it goes, the less any one customer can whip-saw a quarter. The drop from 40% to 32% is meaningful progress. But it’s still a reminder that a handful of accounts can move the story—and stability depends on that continuing to come down.

Security Revenue Growth: If Fastly is going to escape “CDN as commodity,” security is the clearest route. It tends to be higher margin, stickier, and easier to expand inside enterprises once you’re trusted. That’s why the roughly 30% growth rate in security is one of the most encouraging signals in the business—and one worth watching closely as a leading indicator of whether Fastly can broaden beyond delivery.

XIX. Epilogue & Reflections

Fastly’s story, at its core, is a cautionary tale about the gap between building great technology and building a great business around it.

Artur Bergman saw a real problem—legacy CDNs that weren’t built for modern developers—and he built a real solution. The product worked. The customers were real. The early growth was real. But the market Fastly chose to fight in was unforgiving: capital-intensive infrastructure, buyers with leverage, competitors with scale, and a category where “better” is hard to defend once everyone else catches up.

The Cloudflare comparison is unavoidable. Both companies went public in 2019 with versions of the same big idea. One is worth more than $40 billion; the other has struggled around $1 billion. And the difference wasn’t simply technology. It was execution: broader packaging, a more scalable go-to-market motion, and a story the market could keep believing. Cloudflare built a platform. Fastly, too often, got valued like a feature.

And then there’s the biggest promise of all: edge computing. The idea that meaningful computation would move out of centralized clouds to the edges of the network still hasn’t played out at the scale early believers expected. There are real use cases. There are real wins. But the “revolution” hasn’t arrived in the way the hype cycle implied. Fastly may have been right on direction—and early on timing. In company-building, that can be the difference between category king and footnote.

For infrastructure founders, the takeaway is blunt: distribution and scale can matter more than technological purity. For investors, it’s a reminder that developer love and technical excellence can coexist with unstable revenue, heavy competition, and mediocre business outcomes.

Whether Fastly ends up as a cautionary tale or an underdog comeback is still unsettled. The recent signs—faster growth, less concentration, positive free cash flow—suggest a business that’s stabilizing. But stabilization is a long way from the trajectory that once justified $128 a share.

In the end, Fastly may be remembered as a company that proved parts of the edge computing vision could work—and just as clearly proved that working technology is only the starting line.

XX. Further Reading & Resources

Key Sources for Continued Analysis:

- Fastly S-1 IPO Filing (2017) - SEC.gov - The clearest snapshot of Fastly’s original pitch, strategy, and risk factors before the public-market narrative took over

- Fastly June 2021 Outage Postmortem - Fastly Blog - A rare example of an infrastructure company explaining exactly what broke, why it broke, and what it changed afterward

- Cloudflare vs. Fastly competitive analyses - Stratechery and other industry analysts - Helpful context for how two similar edge visions diverged in distribution, packaging, and execution

- Fastly earnings call transcripts - Seeking Alpha and Fastly investor relations - The unfiltered quarter-by-quarter record of what management expected, what changed, and how guidance evolved

- CDN market research - IDC MarketScape and Gartner reports - A look at how the category is framed by enterprise buyers and evaluators, not just engineers

- Edge computing market landscape - a16z and the Bessemer Cloud Index - Useful for separating edge hype cycles from what’s actually getting adopted

- Varnish Cache documentation - The technical foundation behind Fastly’s original edge programmability story

- Recent Fastly Investor Presentations (2024-2025) - Fastly IR website - The most current version of Fastly’s strategy, positioning, and metrics

Recommended Framework Reading: - 7 Powers by Hamilton Helmer - A practical way to think about whether a company has durable competitive advantage, or just a great product - The Innovator's Dilemma by Clayton Christensen - A guide to how markets commoditize and why incumbents (and challengers) often miss the transition - Amp It Up by Frank Slootman - A blunt, operator’s view on what it takes to build an enterprise go-to-market machine that can scale

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music