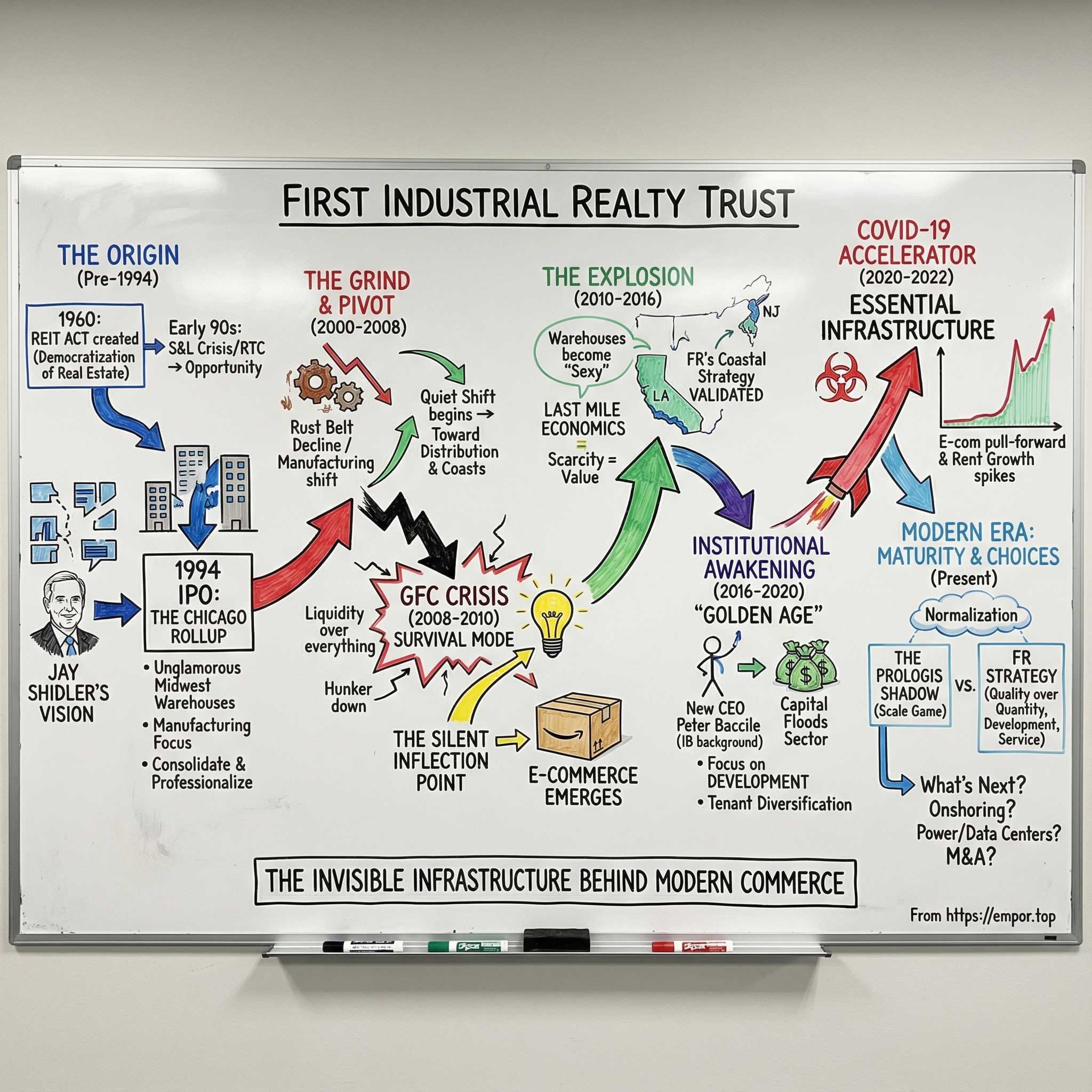

First Industrial Realty Trust: The Quiet Giant of America's Industrial Real Estate Revolution

I. Introduction: The Invisible Infrastructure Behind Every Amazon Box

Picture this: it’s a random Tuesday night. You tap “Buy Now” on Amazon. Two days later, a box shows up on your doorstep like magic. You might admire the speed. You might grumble about the price. But almost nobody stops to ask the quieter question behind the convenience: where did that box actually come from?

Not “from Amazon.” From a building.

A very large, very expensive, very strategically placed building where inventory sat, orders got picked, packed, and pushed into the delivery network. Somebody owns that building. And in modern commerce, owning the right building in the right place can be a phenomenal business.

That’s the world of First Industrial Realty Trust—a U.S.-only owner, operator, developer, and acquirer of logistics properties. They don’t sell you anything directly. They sell space and reliability to the companies that do, providing modern facilities and hands-on operations that keep supply chains running.

Today, First Industrial owns and has under development about 70.4 million square feet of industrial space, with a market capitalization of roughly $6.28 billion. That makes it a real player in the industrial REIT universe—just not the biggest one. That title belongs to Prologis, the 800-pound gorilla with more than a billion square feet globally.

What makes First Industrial so interesting isn’t that they’re the largest. It’s that their arc mirrors the arc of the entire category.

Since 1994, their buildings have housed everyone from Fortune 500 giants to small commercial tenants. They began as an opportunistic Chicago rollup—Midwestern warehouses built to serve the manufacturing belt back when “industrial real estate” was about as sexy as fluorescent lighting. And then the world changed. E-commerce arrived, then accelerated, then reshaped expectations for speed and proximity. The same plain distribution buildings that once felt forgettable suddenly became some of the most coveted real estate in America.

So here’s the framing question: how did a 1994 Chicago real estate rollup become perfectly positioned for an e-commerce revolution it couldn’t possibly have predicted?

This story matters because it’s bigger than one company. It’s about how REITs—an idea Congress created to open real estate ownership to everyday investors—became a powerful machine for building scale. It’s about industrial America shifting from making things to moving things. It’s about surviving the years when your original thesis is getting steamrolled by reality. And it’s about the kind of generational opportunity that only looks obvious in hindsight—if you’re still standing when it arrives.

Today, First Industrial concentrates its portfolio and new investments in 15 target MSAs, with an emphasis on supply-constrained, coastally oriented markets. That wasn’t always the plan. In the beginning, the coasts weren’t the prize—the Midwest was. The journey from there to here is what we’re about to unpack.

II. The REIT Revolution & Founding Context (1960s–1994)

The Birth of a Democratizing Structure

To understand First Industrial, you first need to understand what a REIT is—and why it exists in the first place.

In 1960, Congress created the U.S. REIT structure to give everyday investors access to income-producing real estate. President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed it into law as Public Law 86-779 (often referenced as the Cigar Excise Tax Extension of 1960). The idea was straightforward: make owning real estate feel more like owning stocks. Instead of needing millions to buy an office building outright, you could buy shares in a professionally managed portfolio through a liquid, publicly traded security.

Before REITs, commercial real estate was mostly a closed club. Institutions and wealthy individuals could buy office towers, shopping centers, apartments, and industrial sites. Most Americans couldn’t. REITs changed that by turning real estate into something you could own a slice of—along with everyone else.

The tradeoff is baked into the tax structure. To avoid U.S. federal corporate income tax, REITs generally must pay out at least 90 percent of their taxable income as dividends. That pass-through feature is the key: REITs are designed to throw off cash to shareholders, but it also means they can’t simply retain earnings to fund growth. They have to keep raising capital—then reinvesting it—over and over again.

The "Modern Era" Emerges from Crisis

REITs existed for decades after 1960, but the modern REIT era really took shape in the aftermath of the Savings and Loan crisis.

The late 1980s and early 1990s were a wrecking ball for real estate. Oversupply met tightening credit, and property values fell hard. Projects that looked inevitable on paper suddenly sat half-empty. Foreclosures mounted. And financing—especially the easy kind—disappeared.

A key difference from 2008 was the government’s direct role. During the S&L crisis, federal regulators took over 747 failed institutions and ended up controlling massive piles of loans and real estate. To deal with it, the government created the Resolution Trust Corporation, or RTC, to manage and ultimately sell those assets back into private hands. But the RTC took time to ramp up, and by the time it did, it was sitting on thousands of real estate assets.

That cleanup turned into a once-in-a-generation buying opportunity. Well-capitalized investors could scoop up properties and loan portfolios at distressed prices. Private equity proved the model, and then everyone chased it. Real estate private equity, once a tiny corner of finance, eventually grew into an industry with hundreds of billions under management.

At the same time, a separate but related shift was happening: real estate companies started going public in large numbers as REITs. The public markets became a new, scalable source of capital for an asset class that had historically been illiquid and locally financed.

Enter Jay Shidler: The Vision to Consolidate

Into this changing world stepped Jay Harold Shidler.

Shidler, an investor and philanthropist, grew up on military bases around the world as the son of a career U.S. Army officer. He attended the University of Hawaiʻi, earned a business degree in 1968, and was commissioned into the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. After returning to Hawaii in 1971 as a First Lieutenant, he formed The Shidler Group.

From a home base in Honolulu—about as far from Wall Street as you can get while still being in the United States—Shidler built a national real estate investment organization. Over time, The Shidler Group acquired and owned more than 2,000 commercial properties across 40 U.S. states and Canada. Shidler also became the initial investor in more than 30 public and private companies, with five eventually listing on the NYSE.

He was also the co-founder and initial Chairman of First Industrial Realty Trust. And importantly, First Industrial would be one of the first publicly traded REITs to focus exclusively on industrial property.

The IPO: A Fragmented Market Gets Consolidated

First Industrial was built as a rollup from day one.

The company packaged Shidler’s Midwestern industrial holdings alongside properties from three other developers—either already owned or acquired using IPO proceeds. Those developers included Troy, Michigan-based Damone/Andrew Associates Inc., Minnesota-based developer Steven Hoyt, and Pennsylvania-based developer Anthony Muscatello. The REIT was headed by Tomasz.

When First Industrial completed its IPO in June 1994, it owned 226 industrial properties totaling 17.4 million square feet across nine cities.

This wasn’t Silicon Valley going public with a new gadget. It was a financial and operational thesis: industrial real estate was fragmented, undervalued, and often poorly managed. Put it under one roof, professionalize it, finance it with public-market capital, and you could build scale—then turn that scale into advantages: lower cost of capital, better operations, and stronger tenant relationships.

The timing was good. The sector choice was not.

In hindsight, industrial looks like the obvious answer. A 2024 observation captured it neatly: “As recently as 10 years ago, industrial real estate was seen as a fairly unremarkable asset class. However, the rise of e-commerce significantly increased its appeal.” But in 1994, industrial was still firmly “unremarkable.” Low rents. Low prestige. Institutional neglect. The glamour capital chased office and retail. Nobody talked about “logistics” or “last-mile.” And the economy that industrial space served was still, overwhelmingly, built around making things—not racing to move them in two days.

III. The Rollup Era: Building Scale Through Consolidation (1994–2000)

The Strategy: Buy, Professionalize, Repeat

From the IPO through the late 1990s, First Industrial did what it was built to do: roll up a fragmented corner of commercial real estate and make it run like a real company.

The playbook wasn’t complicated. Find portfolios of industrial buildings owned by smaller operators, buy them at reasonable cap rates, fold them into a centralized platform, and keep going—funding the next set of deals with access to the public markets.

The growth showed up quickly. By 1997, revenue had climbed to about $210 million, and net income was nearing $52 million. The portfolio was expanding across the Midwest and the broader manufacturing belt, and the tenant roster stretched from small manufacturers to big-name corporates. This was industrial real estate as it existed at the time: practical buildings serving an economy still centered on making things.

In 1996, First Industrial also launched its Development Services Group division. It was an early step beyond pure acquisition—still secondary to the rollup engine, but an important capability to have in-house for what would come later.

The Competitive Landscape

First Industrial wasn’t the only one sniffing around industrial, but in the mid-1990s the sector still sat far from the center of institutional attention. Other industrial REITs were emerging, and private equity was starting to take a look. Still, the real glamour money was elsewhere: office towers in major downtowns, suburban malls at the peak of retail, and apartments in fast-growing cities.

Industrial, by contrast, was treated like a commodity. Warehouses were thought of as interchangeable boxes. Tenants were viewed as unsophisticated. Margins were assumed to be thin. The conventional wisdom was that you couldn’t build a durable edge here.

That view would age badly. But in the late 1990s, it kept the crowd from piling in.

The 1998 Wake-Up Call

Then the market reminded everyone that REITs weren’t immune to sentiment.

In 1998, REIT stocks sold off hard. A First Industrial executive told The Wall Street Journal that the stretch between May and September was “like the Bataan death march.” Tomasz went into full defense mode—constant road shows, nonstop reassurance—trying to keep analysts, rating agencies, and shareholders convinced the story still worked.

Amid that downturn, the company replaced its CEO in 1998. It was a leadership change in the middle of a rough tape—part market pressure, part the strain that comes with scaling fast in a suddenly unfriendly environment.

Early Signs of E-Commerce (Sort Of)

And yet, even as the public markets were wobbling, the company was starting to tilt its strategy.

In 1999, First Industrial began concentrating on the top 25 industrial real estate markets in the U.S., aiming to benefit from rising demand tied to e-commerce and supply chain management.

It’s a striking moment to see in print, because in 1999 “e-commerce” didn’t mean what it means now. It was the height of the dot-com bubble—pets.com, eyeballs, hype. Amazon was still mostly books. The idea that online retail would become a logistics arms race, and that warehouses near major population centers would turn into premium real estate, wasn’t remotely consensus.

But something was changing. Companies were getting more serious about supply chain management. Distribution patterns were starting to evolve. And First Industrial—whether by insight or instinct—began edging toward the markets that would matter most when “boring warehouses” became the backbone of modern commerce.

IV. The Lean Years: Surviving Manufacturing Decline (2000–2008)

The Rust Belt Reality

The early 2000s were not kind to First Industrial’s original bet.

They’d built the portfolio for the Midwest manufacturing belt—Detroit, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Minneapolis—the places where American industry had long meant cars, heavy equipment, and the web of suppliers that fed them.

And then that web started to snap.

Factories shut down as production migrated to lower-cost countries, especially China. NAFTA, enacted in 1994—the same year First Industrial went public—helped accelerate shifts to Mexico. The tenants that had filled First Industrial’s buildings—manufacturers, parts suppliers, and the distributors that served them—began shrinking, relocating, or disappearing entirely.

If the 1990s were about buying “industrial” because it was cheap and ignored, the 2000s were about discovering just how much of that industrial economy was leaving town.

The Unglamorous Grind

From 2000 to 2008, First Industrial entered its wilderness years. No flashy reinvention. No heroic, headline-grabbing acquisition. Just the slow work that real estate companies are built on when the macro turns against them: managing occupancy in weakening markets, negotiating with stressed tenants, and deciding what to fix, what to hold, and what to sell.

By the end of 2003, the portfolio was massive. First Industrial owned a broad mix: 423 light industrial properties, 163 research-and-development or flex properties, 123 bulk warehouse properties, 92 regional warehouse properties, and 33 manufacturing properties. In total, it controlled 57.9 million square feet across 22 states.

That scale was an asset. It was also a problem.

The portfolio wasn’t a clean, modern logistics machine. It was a patchwork—some buildings that could serve the emerging distribution economy, and plenty that were still tethered to a manufacturing base that was steadily eroding. The question wasn’t “how do we grow?” It was “what is this portfolio going to be when it grows up?”

The Strategic Pivot Begins

Somewhere in that grind, First Industrial started to change its stripes.

Quietly, the company began shifting away from heavy manufacturing space and toward lighter distribution. It also started rebalancing geographically—reducing exposure to struggling Midwest markets and leaning more into coastal markets and major transportation hubs.

But this wasn’t a dramatic pivot you could capture in a single press release. It happened the way real estate transformations usually happen: one disposition at a time, one acquisition at a time, one reinvestment decision at a time. Older, functionally obsolete properties in the wrong markets went out. More modern distribution facilities in markets with better long-term demand came in.

That sounds simple. It wasn’t.

Capital is always finite in a REIT. Every move into a better market meant making a trade: sell something, or raise new money. And at the time, industrial REITs were still a backwater—seen as the least exciting part of an already unglamorous asset class. This was not a period when the market rewarded patience or gave you the benefit of the doubt.

Leadership and Long-Term Thinking

What kept First Industrial from panicking was a willingness to play the long game.

Plenty of real estate companies under similar pressure would have tried something dramatic—sell the platform, merge with a competitor, or abandon industrial altogether. First Industrial largely did the opposite. Management kept working the portfolio: staying close to tenants, investing where it made sense, and steadily nudging the business toward properties that would matter more in the future.

They didn’t know an e-commerce revolution was coming, let alone that it would turn warehouses near major population centers into some of the most valuable real estate in the country.

But they did know a simpler truth: supply chains don’t go away. Goods still have to move. And well-located real estate—eventually—gets paid for.

V. The Financial Crisis & Turning Point (2008–2010)

The World Falls Apart

When the financial crisis hit in 2008, it threatened to undo everything First Industrial had built.

This wasn’t a normal downturn. It was a global financial shock centered in the U.S., driven in large part by a housing bubble inflated by speculation, lax underwriting, subprime lending, and regulatory blind spots. When the bubble burst, the damage didn’t stay contained to homeowners or banks—it tore straight through the plumbing of credit markets.

And for REITs, credit is oxygen.

Real estate is capital-intensive by nature. Buildings are bought with debt, refinanced with debt, and valued using assumptions that depend on debt being available at reasonable rates. So when lenders stopped lending, REITs everywhere slammed into the same wall: maturities coming due, refinancing markets frozen, and equity prices collapsing right when you’d least want to issue shares.

It was brutal. REIT indices fell sharply, dividends got cut across the sector, and companies that had leaned too hard into cheap leverage during the boom years suddenly looked like they might not make it through the winter. Different property types behaved differently, but the pattern was the same: a steep drop, followed by a slow, uneven recovery. Industrial held up better than some categories, but it still got hit hard.

The Survival Playbook

First Industrial survived, but not by luck.

They ran the classic crisis playbook: sell assets to raise cash, cut costs, and prioritize liquidity over everything. In a world where capital might not be available tomorrow, the only strategy that mattered was making sure you could pay your bills, manage your debt, and live to see the other side.

This is where the decisions from the years before paid off. First Industrial hadn’t binged on leverage the way some peers did in the 2005–2007 froth. That relatively conservative posture didn’t make them immune to the downturn, but it did buy them time. And in a frozen market, time is a superpower.

The Hidden Inflection Point

Here’s the twist: while the financial system was melting down, the retail economy was quietly changing shape underneath it.

E-commerce had been growing throughout the 2000s, but 2008 to 2010 started to feel like an inflection point. Amazon kept expanding, building out its fulfillment footprint and taking share from traditional retailers that were now fighting a recession and a new kind of competition at the same time.

The “retail apocalypse” phrase wasn’t mainstream yet. But the physics were becoming obvious: if customers expected fast delivery, retailers needed inventory closer to them—and they needed buildings designed to move goods at speed.

Amazon is the cleanest example. With Prime pushing two-day shipping expectations, the company built a massive logistics network—hundreds of fulfillment and operating facilities globally, spread across an enormous amount of warehouse space.

And that’s when First Industrial’s story flips.

Those plain distribution buildings—dismissed for years as commodity boxes—started to look like scarce, strategic infrastructure. Retailers needed more distribution capacity. E-commerce players needed fulfillment space. Third-party logistics providers needed nodes in the network.

The very properties that had been overlooked during the manufacturing decline were suddenly becoming the ones everyone wanted.

VI. The E-Commerce Explosion: Right Place, Right Time (2010–2016)

The Macro Shift Nobody Predicted

In the decade after the financial crisis, commercial real estate experienced a brutal and fascinating rotation. As consumers shifted more of their spending online, supply chains had to be rebuilt around a new promise: ship individual orders directly to homes, fast, at massive scale.

That single change rewired logistics. It also rewired real estate. For years, industrial had been treated as the plainest corner of the property world—functional, forgettable, interchangeable. Then, almost overnight, the industry woke up to a new reality captured perfectly by a line that started showing up in market commentary: “As recently as 10 years ago, industrial real estate was seen as a fairly unremarkable asset class. However, the rise of e-commerce significantly increased its appeal.”

And the demand was visible in the fundamentals. Leasing demand surged; net absorption ran at more than double the pace seen just a handful of years earlier.

The deeper reason was simple but powerful: e-commerce is warehouse-intensive. Online fulfillment generally requires far more distribution space than a traditional store-based model—often multiple times more. CBRE Research put a number on it: for every additional $1 billion of e-commerce sales, the system needs roughly another 1.25 million square feet of distribution space to support it.

That’s why industrial didn’t just benefit from e-commerce. It became one of the primary bottlenecks. In a store-based world, the “last mile” was the customer walking out with a bag. In an e-commerce world, the last mile is expensive, operationally hard, and entirely dependent on having the right buildings in the right places.

Amazon Reshapes the Landscape

No company embodied this shift more than Amazon.

Its fast-delivery playbook required a web of fulfillment centers and supporting facilities positioned near major metro areas, with additional nodes that extended reach into smaller regions. Amazon built out a huge footprint—about 110 fulfillment centers in the U.S. and more than 185 globally—so that, no matter where customers lived, orders could arrive quickly and reliably.

But Amazon didn’t build everything itself. It leased enormous amounts of space from third-party landlords, including industrial REITs like First Industrial. More importantly, Amazon’s speed forced everyone else to follow. Retailers that had spent decades perfecting store networks suddenly had to build fulfillment capacity, or partner with third-party logistics providers who would.

The result was a rising tide for logistics real estate—one that lifted almost every credible owner of modern, well-located buildings.

Last-Mile Economics Transform Location Value

E-commerce didn’t just increase demand. It changed what “good” looked like.

Historically, industrial value centered on the building: size, clear height, loading doors, trailer parking. Location mattered too, but mostly as it related to freight—ports, rail, and highway access.

Then the priority shifted from moving pallets efficiently to getting packages to people quickly. Proximity to population centers started to dominate. A warehouse twenty miles from downtown Los Angeles could be worth dramatically more than an otherwise similar building much farther away, simply because it could shave time and cost out of delivery.

This is where First Industrial’s strategy began to look less like a slow-motion pivot and more like prescience. The company’s portfolio and new investments were concentrated in 15 target MSAs, with an emphasis on supply-constrained, coastally oriented markets.

That mattered because in the places where last-mile value was highest—Southern California, Northern New Jersey, South Florida—land wasn’t just expensive. It was scarce. Zoning was tight, entitlement was hard, and there were only so many sites left that actually worked for modern logistics.

First Industrial's "Aha Moment"

For First Industrial, this was the payoff for a decade of unglamorous repositioning.

They had spent the 2000s moving away from manufacturing-heavy exposure and toward distribution in stronger markets. As e-commerce accelerated, that portfolio became more relevant—and more valuable—by the quarter.

Across the national logistics sector, rent growth stayed strong, and investor returns followed. First Industrial leaned into the moment by accelerating development in high-demand markets, continuing to sell older, non-core assets, and recycling that capital into newer distribution buildings designed for the modern supply chain.

The company didn’t need a flashy reinvention. The market finally moved in the direction their portfolio had been inching toward all along.

The Competition Heats Up

Of course, once industrial stopped being “unremarkable,” it stopped being lonely.

Industrial REITs expanded rapidly to meet demand, growing portfolios materially in a short period. Prologis, already the category leader, kept widening the gap. Private equity poured in. Investors bid aggressively for buildings, and cap rates compressed as prices rose.

What had once been dismissed as a commodity box business turned into one of the most competitive arenas in real estate—and First Industrial was now fighting in a sector that everyone suddenly understood was strategic.

VII. The Institutional Awakening: Industrial Goes Mainstream (2016–2020)

Capital Floods the Sector

By 2016, industrial real estate wasn’t the overlooked cousin anymore. It was the favorite.

Institutional capital that used to treat warehouses as a tiny allocation started moving in size. Insurance companies, pensions, sovereign wealth funds—everybody wanted exposure. The pitch was clean and easy to understand: vacancies were low, rents were rising, e-commerce kept pushing demand forward, and the business was operationally simpler than most other property types.

Compared to hotels, you weren’t managing nightly pricing. Compared to retail, you weren’t fighting consumer foot traffic and bankrupt tenants. The model looked almost boring in the best way: control great locations, own modern buildings, sign leases with solid tenants, collect rent, repeat.

And once enough big money decided industrial was the place to be, it stopped being a niche. It became mainstream.

A New Leader Takes the Helm

In September 2016, First Industrial announced that Peter E. Baccile had been named President and would join the company’s Board, effective immediately. He was 54, and he brought more than three decades of management, real estate, and financial experience—but not from the usual REIT pipeline.

Baccile came from J.P. Morgan, where he spent 26 years in senior leadership roles. Most recently, he was Vice Chairman of J.P. Morgan Securities Inc. and Co-Head of the General Industries Investment Banking Coverage Group, which included Real Estate, Lodging, Gaming, Diversified Industrials, Paper Packing and Building Products, and Transportation.

A few months later, in December 2016, he assumed the CEO role when Bruce Duncan retired.

On paper, it was an unusual move: an investment banker taking the top seat at an industrial REIT. But it also made a certain kind of sense. Industrial was entering a phase where capital markets savvy—how you fund growth, when you issue equity, how you think about development versus acquisitions—could be just as decisive as day-to-day property operations.

As the company put it at the time: “Peter joins us bringing a wealth of leadership, real estate and capital markets expertise to First Industrial, including a deep knowledge of the industrial real estate industry given his experience serving companies within our sector during his accomplished career in investment banking and advisory.”

For Baccile personally, the timing lined up, too. After three decades in banking, he took the job as his youngest child was preparing to leave for college.

The "Golden Age" of Industrial Real Estate

“We are in what I consider to be the ‘golden age of industrial real estate.’ There is much opportunity ahead to grow cash.”

It’s hard to read that line without hearing the confidence of the moment—and in this case, the results backed it up. From 2016 through 2020, industrial demand kept coming. Occupancies stayed high. Rents moved up. New development penciled. And the tenant base kept expanding, pulled forward by the logistics arms race that e-commerce had kicked off.

This wasn’t just a good cycle. It felt like the sector had been structurally re-rated.

Strategic Focus and Execution

Under Baccile, First Industrial kept sharpening what it had already been becoming: a portfolio built for modern logistics in the markets that mattered most.

The focus was increasingly clear:

- Southern California and coastal market expansion: putting more capital into supply-constrained markets with the strongest long-term fundamentals

- Modern bulk distribution development: building large, state-of-the-art facilities suited to e-commerce and logistics users

- Tenant mix diversification: expanding exposure to Amazon, FedEx, UPS, third-party logistics providers, and omnichannel retailers

The company’s emphasis wasn’t just on owning buildings—it was on staying close to what tenants actually needed as the logistics playbook evolved in real time:

“In the industrial business, our world is evolving rapidly. The needs of our tenants are changing almost weekly, so offering the right form and functionality to our tenants is an area where we must stay on top of the trends. Not only that, but having professional property managers that are responsive to our customers and take care of our buildings is key to retention, especially in a down market. Customer service is ingrained in our culture.”

COVID-19: The Ultimate Validation

Then, in early 2020, the stress test arrived.

COVID hit commercial real estate like a blunt instrument. Offices emptied. Hotels went dark. Retail stores shuttered. Whole business models suddenly looked fragile.

Industrial was the exception.

Warehouses didn’t just stay open—they became more essential by the week. Consumers shifted spending online at a speed nobody had planned for. Companies scrambled for space to handle the surge and to buffer supply-chain disruption. As one observer put it, the COVID years became a helter-skelter period of warehouse users grabbing whatever space they could find. The torrent of leasing activity helped drive double-digit rent growth.

E-commerce penetration, which had been steadily climbing for years, jumped ahead by what many estimated was about five years in just a few months. People who had never shopped online became regular customers. Delivery expectations tightened. Distribution networks strained.

And for First Industrial—and every well-positioned industrial landlord—it was the cleanest validation imaginable. While other real estate categories wrestled with existential questions, industrial was treated as essential infrastructure. The buildings stayed busy. Demand surged. And the once-“unremarkable” asset class looked, suddenly, like one of the most strategically important pieces of the modern economy.

VIII. The Modern Era: Maturity & Strategic Choices (2020–Present)

Navigating Post-Pandemic Normalization

After the pandemic surge, the industrial story didn’t break—it cooled.

As consumers started spending more time in physical stores again, and shifted more of their budgets from “stuff” to long-delayed services that got them out of the house, the pressure valve released. Across much of the U.S., industrial fundamentals softened. Year-over-year rent growth that had been running red-hot fell back to earth, dropping to roughly 3.6 percent in the second quarter of 2024 from more than 16 percent a year earlier.

Vacancy moved up toward cyclical highs. New construction, meanwhile, started to contract. In the first half of 2024, new supply still outpaced new demand—but the gap narrowed, hinting that the market was slowly working through the excess.

The industry’s challenges were familiar, but now they were happening all at once:

- Supply concerns: Space that was greenlit during the boom kept delivering into a slower-demand environment

- Interest rate impacts: Higher rates raised the cost of capital—bad for development math and refinancing alike

- E-commerce normalization: Online retail kept growing, but at more sustainable rates after the COVID pull-forward

- Tenant rationalization: Some retailers, including Amazon, had expanded too aggressively and began subleasing space

First Industrial's Strong Execution

Even in that cooler backdrop, First Industrial kept putting up strong numbers.

In 2024, the company initiated 2025 NAREIT FFO guidance of $2.87 to $2.97 per share/unit, about 10% growth at the midpoint. It also increased its first quarter 2025 dividend to $0.445 per share, a 20.3% increase. Fourth quarter funds from operations came in at $0.71 per share/unit on a diluted basis, up from $0.63 a year earlier. For the full year 2024, FFO was $2.65 per share/unit, compared to $2.44 in 2023—an 8.6% increase.

The more telling story was what happened when leases rolled.

In the fourth quarter, cash rental rates increased 41.4%. For the full year, cash rental rates increased 50.8%, the second-highest annual increase in company history.

Those gains weren’t just “the market is still strong.” They were a mark-to-market reveal. As older leases—signed at much lower rent levels—expired, First Industrial was able to reset them closer to today’s pricing. Even as headline rent growth moderated, the company still had meaningful embedded rent upside sitting inside the portfolio.

The Prologis Shadow and Industry Consolidation

If there was a single moment that captured where industrial real estate had landed by the 2020s, it was this: consolidation at the very top.

In 2022, Duke Realty announced it would be acquired by Prologis. The transaction closed on October 3, 2022, and Duke is now part of Prologis.

Prologis agreed to acquire Duke Realty in an all-stock deal valuing Duke at $26 billion, including the assumption of debt. Prologis was already the category leader, with a market capitalization of more than $81 billion. Duke, the second-largest industrial REIT at the time, had a market cap of over $19.5 billion. Together, it created a logistics real estate superpower with a market value north of $100 billion.

The implications were obvious: Prologis’s scale advantage—cost of capital, tenant relationships, development reach—became even harder to match. And for a mid-sized pure-play like First Industrial, it sharpened the strategic question: in a sector that increasingly rewards scale, how do you compete, and how do you stay independent if the industry keeps consolidating?

The Current Strategic Position

First Industrial’s portfolio and new investments are concentrated in 15 target MSAs, with an emphasis on supply-constrained, coastally oriented markets. As of September 30, 2025, the company owned and had under development approximately 70.4 million square feet of industrial space.

The strategy in this era is less about being everywhere and more about being right:

- Quality over quantity: Prioritizing top markets over broad national coverage

- Development as a value driver: Creating value through building, not just buying

- Balance sheet strength: Keeping leverage conservative to preserve flexibility

- Customer focus: Competing through responsiveness, service, and relationships

As the company put it: “In 2024, the First Industrial team delivered strong portfolio operating metrics and signed 4.7 million square feet of development leases, the second highest annual volume since we re-launched our development program in 2012.” In the fourth quarter, First Industrial commenced two development projects totaling 679,000 square feet, with an estimated investment of $96 million.

IX. The Business Model Deep Dive: How Industrial REITs Actually Work

The REIT Structure: Tax Efficiency with Discipline

At the core, a REIT is a tax-advantaged, pass-through structure. The company generally doesn’t pay U.S. federal corporate income tax on the income it earns from real estate. Instead, that income flows through to shareholders, who pay the tax.

But the deal comes with rules. To keep REIT status, a company has to live inside a pretty strict box: most of its assets have to be real estate (or real estate-adjacent things like cash and U.S. Treasuries), most of its income has to come from real estate activities, and it has to pay out at least 90 percent of taxable income to shareholders each year.

That combination creates both the superpower and the constraint. The superpower is obvious: no corporate-level tax means more of the economics can reach investors. The constraint is equally important: REITs can’t just hoard earnings to fund growth. If they want to build, buy, or reposition properties, they usually have to go back to the capital markets—raising debt, issuing equity, or both.

Triple Net Leases: The Foundation of Stable Cash Flow

Industrial REIT cash flow is built on a surprisingly simple contract: the triple net lease.

Under a triple net lease—often shortened to NNN—the tenant pays the rent, and also covers major property-level expenses like insurance, property taxes, and common area maintenance. In plain terms, the tenant takes on most of the day-to-day cost variability of operating the building, while the landlord collects rent.

Industrial is especially well-suited to this setup. Warehouses and fulfillment centers are often leased to a single tenant that occupies the entire building, and those leases can run a long time—sometimes stretching up to 25 years. That creates the REIT version of “subscription revenue”: steady, contractually defined cash flow.

The predictability comes from two places. First, many leases include annual rent escalators. Second, because most operating expenses are pushed to the tenant, the landlord’s big swing factors are limited: vacancy when a tenant leaves, and the capital needed to refresh or reconfigure a building for the next occupant.

The Development Cycle: Creating Value from Dirt

Acquisitions build scale. Development can create step-change value.

When an industrial REIT develops a building, it’s taking a piece of land and turning it into a modern logistics asset—often in a market where there simply isn’t much land left to do that. The cycle usually looks like this:

- Land acquisition: Buy entitled land, or buy raw land and secure entitlements

- Design and permitting: Engineer the facility and get approvals

- Construction: Build the building (often 12 to 18 months for larger projects)

- Lease-up: Sign tenants, either as a pre-leased build-to-suit or as a speculative project

- Stabilization: Once it’s leased, it becomes a long-term core holding

When things go well, development spreads—the gap between what it costs to build and what the finished, leased building is worth—can be substantial, especially in strong markets.

But this is where the risk lives, too. Construction costs can jump mid-project. Demand can cool while steel is going up. Lease-up can take longer than planned. Development is value creation, but it’s value creation with timing risk attached.

Why Location Creates the Moat

In industrial real estate, the moat isn’t a fancy lobby. It’s land in places that are hard to replicate.

E-commerce and modern logistics have made proximity more valuable than ever—close to ports, highways, and dense population centers. And tenants often prefer NNN leases because they want control over operating costs and building operations as they push for speed and efficiency.

But the deeper truth is this: you can’t create more industrial land in the places everyone needs to be. You can’t manufacture new supply in Southern California’s Inland Empire at will. You can’t easily add industrial sites near the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. And you can’t casually carve out new logistics corridors in supply-constrained Northern New Jersey.

That scarcity shows up in pricing. Cap rates—the yield investors accept when buying properties—can be dramatically different for buildings that look similar on paper. A warehouse in California’s Central Valley might trade around a 6% cap rate, while a comparable facility in Los Angeles might trade around 4%. Same basic box. Totally different economics. The difference is the dirt underneath it—and the access that dirt buys to people, infrastructure, and time.

X. Strategic Frameworks & Competitive Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate to Low

Getting into industrial real estate takes capital. But staying in it, and winning in it, takes something rarer: well-located land. In the best markets, zoning restrictions, environmental rules, and the simple reality that there aren’t many workable sites left all raise the bar. Private equity is still active, but in many of the most desirable submarkets, the best dirt is already spoken for—controlled by the incumbents who got there earlier.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low to Moderate

For an industrial REIT, the key “supplier” is the construction ecosystem—contractors, labor, and materials. In normal times, it’s a competitive market and landlords can bid work out. In boom periods, that flips. In 2021 and 2022, labor shortages and materials constraints gave builders real pricing power and pushed costs up. Since then, costs have cooled somewhat, but the lesson sticks: development returns can swing quickly when the construction market tightens.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Tenants): Moderate

Big tenants—Amazon, Walmart, major third-party logistics providers—have leverage because they take a lot of space and they know the market. They can run a tight process and negotiate hard. But their power has limits, especially in the places that matter most. In supply-constrained markets with low vacancy, “take your pick” can become “take what you can get.” And even for giants, moving a distribution operation isn’t like moving an office. It’s disruptive, operationally risky, and expensive.

Threat of Substitutes: Low

You can optimize a warehouse with automation. You can pack inventory tighter. You can squeeze more productivity out of the same footprint. But you can’t digitize the physical reality that e-commerce and modern logistics require buildings. There’s no true substitute for space with docks, trailer parking, and access to highways and customers.

Competitive Rivalry: High

This is a knife fight with forklifts.

Prologis sets the pace with unmatched scale. Strong specialists like Rexford in Southern California and EastGroup in the Sunbelt win by owning the right markets and executing relentlessly. Private equity is constantly in the mix. And as cap rate compression has made buying stabilized buildings less attractive, the competition has shifted toward development—and toward controlling the land positions that make development possible.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Moderate

Scale helps. It lowers cost of capital, deepens tenant relationships, and spreads overhead across a larger base. Prologis’s size creates advantages that a mid-sized player like First Industrial can’t easily match.

But there’s a catch: industrial is still, at its core, a local business. National scale doesn’t automatically win you a lease on a specific interchange in a specific submarket. You still need the right site and the right building for that tenant, right now.

Network Effects: Minimal

This isn’t a network-effect business. Owning more warehouses doesn’t inherently make each warehouse more valuable.

Counter-Positioning: Diminished

In the early years, betting on industrial while others chased office and retail was a form of counter-positioning—industrial was ignored because it didn’t fit the fashionable narrative. Today, that edge is gone. Everyone sees the value now, and capital has poured in accordingly.

Switching Costs: Moderate

Tenants don’t switch lightly. They install racking, equipment, and systems. They build processes and hire labor around a location. Moving can mean retraining an entire workforce and risking service levels.

But switching costs aren’t permanent lock-in. At lease expiration, tenants regularly shop alternatives—especially if the rent reset is steep enough to justify the pain.

Branding: Low

Tenants mostly care about location, building quality, and economics—not which logo is on the landlord letterhead. First Industrial’s “2-Hour Rule” on customer service can help at the margin, but brand isn’t the core moat in this category.

Cornered Resource: Moderate to Strong

The cornered resource is land—especially infill land in supply-constrained markets. If you control irreplaceable sites near ports, dense populations, and major transportation corridors, you have a real advantage. First Industrial’s emphasis on “supply constrained, coastally-oriented markets” is essentially a strategy statement built around that resource.

Process Power: Moderate

Execution matters. Development is a timing-and-details business: entitlements, budgets, schedules, lease-up, and tenant service. First Industrial’s ability to deliver buildings and run them well creates an edge.

But it’s not magic. Well-capitalized competitors can replicate good processes, hire the same talent, and bid for the same contractors. Process power helps—but it’s not unassailable.

Competitive Positioning

First Industrial is a REIT built around the physical movement of goods—distribution centers and logistics-focused warehouse properties designed to serve the trucking-and-delivery economy.

That puts the company in an interesting middle lane: big enough to matter, small enough that it can’t simply outmuscle the category leader on scale. So the strategy has to be sharper. The company has leaned into a clear set of choices:

- Focus on the U.S.: Unlike Prologis’s global footprint, First Industrial is exclusively domestic

- Concentrate on top markets: It puts capital into the highest-quality, most supply-constrained markets instead of trying to be everywhere

- Emphasize development: Build value rather than overpay for stabilized assets when acquisitions get bid up

- Differentiate on service: Stay close to tenants and win on responsiveness, not just rent roll

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Perspective

The Bull Case

Structural Tailwinds Persist

Even after the post-COVID cool-down, the long-term direction of travel still favors industrial. The shift toward more domestic and near-shore production is expected to keep pulling demand toward U.S. manufacturing, warehousing, and distribution space. Over time, that supports stable occupancy, continued development activity, and a generally constructive backdrop for industrial landlords.

E-commerce is also still far from “done.” It represents only about 16% of retail sales, which implies meaningful runway ahead. At the same time, supply chains are being redesigned for resilience: more reshoring, more redundancy, and more safety stock. And all of that, in one way or another, translates into a need for more space.

Supply Constraints in Key Markets

This is the core of First Industrial’s positioning. It’s one thing to say demand should be steady; it’s another to own buildings in markets where new supply is genuinely hard to create.

In places like Los Angeles or Northern New Jersey, you can’t just decide to build a million square feet because the spreadsheet says so. Land is scarce, entitlements are difficult, and regulatory barriers are real. If you already control the right sites in those markets, you’re operating with a built-in advantage.

Embedded Rent Growth

First Industrial has also been harvesting a powerful, very real source of growth: lease roll.

For the full year, cash rental rates increased 50.8%, the second-highest annual increase in company history. And on leases signed to date that commence in 2025, the company has achieved cash rental rate increases of about 33%.

The important idea isn’t the exact number—it’s what the numbers are telling you: there’s a meaningful gap between in-place rents and today’s market rents. When older leases expire, those rents reset higher, driving NOI growth even if headline market rent growth is no longer booming.

Strong Operational Execution

Industrial can look simple from the outside, but the winners still separate themselves on execution: keeping buildings full, keeping tenants happy, delivering development on time, and allocating capital with discipline.

Under Baccile, First Industrial has built a track record of operational consistency—strong leasing volume, steady occupancy, and a development program that’s become a real value-creation engine rather than a side project.

Potential Acquisition Target

Finally, there’s the strategic optionality angle. In a world where scale keeps getting rewarded, a mid-sized, pure-play industrial REIT with a concentrated, high-quality portfolio can become a logical target—either for a larger public player looking to add U.S. exposure, or for private equity looking to take a portfolio private.

The Bear Case

Oversupply Concerns

The hangover from the boom years is still working its way through the system.

In the first half of this year, new supply continued to outpace new demand, even though the gap narrowed. Third-party logistics firms—delivery and logistics operators like Ryder and DHL moving goods on behalf of clients—have been leading demand. But the broader issue remains: a lot of product that was started when leasing was frantic is still delivering now, into a more normal environment.

That dynamic has pushed vacancy up from trough levels and, unsurprisingly, put pressure on rent growth.

E-Commerce Maturation

E-commerce is still growing as a share of retail, but the pace is no longer the pandemic-era sprint.

The surge that drove “grab anything you can” leasing a few years ago has moderated. Some retailers expanded too far, too fast, and have been rationalizing space. The growth story is intact—but it’s shifted from explosive to sustainable, which changes the tone of the entire market.

Interest Rate Sensitivity

REITs don’t live in a vacuum. Higher interest rates raise borrowing costs, pressure development economics, and reduce the present value investors assign to future cash flows. The higher-rate environment of 2022 through 2024 already hit REIT valuations, and the risk is that capital stays expensive longer than expected.

Scale Disadvantage

Then there’s the Prologis problem.

Competing against Prologis’s cost of capital, tenant relationships, and development reach is difficult even in good markets. And with Duke Realty now inside Prologis, the scale gap only widened. The question for First Industrial isn’t whether it can execute—it’s whether it can keep creating value as a mid-sized player in a sector where consolidation continues to tilt advantages toward the very largest platforms.

Automation Risk

Automation isn’t an immediate demand killer, but it’s a long-term variable worth watching. If warehouse technology enables companies to push more throughput through less space over time, that could gradually reduce space needed per unit of commerce—especially in the most advanced, highest-cost markets.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch

For investors tracking First Industrial, two KPIs do most of the work:

1. Cash Same-Store NOI Growth

This is the cleanest measure of organic growth—what the existing portfolio is doing, separate from acquisitions and new developments. It captures rent increases, occupancy changes, and expense management. For the full year, same-store NOI increased 8.1%, primarily reflecting higher rental rates on new and renewal leasing and contractual rent escalations.

2. Cash Rental Rate Increases on New and Renewal Leasing

This is the “mark-to-market” indicator: the spread between what expiring leases were paying and what new leases pay. As long as that spread stays healthy, First Industrial has visible, embedded growth. If it narrows sharply, that’s often the early signal that market fundamentals are weakening.

XII. Lessons & Takeaways: The Playbook

Strategic Patience Pays Off

First Industrial’s arc—from a 1994 Midwest rollup of warehouses to a coastal, logistics-focused platform—wasn’t a sudden reinvention. It was a decades-long repositioning.

They couldn’t have forecast what e-commerce would become when they went public. What they did do was stay alive long enough to benefit from it: grind through the manufacturing decline without blowing up, keep the balance sheet from getting reckless, and come out of 2008 with the ability to play offense when the opportunity finally arrived.

Boring Can Be Beautiful

For years, industrial was the definition of boring. Low rents. “Just warehouses.” Tenants that didn’t sound impressive at a cocktail party. No trophy buildings, no glamour, no buzz.

And then it turned out to be one of the best-performing property types for years, precisely because the world started valuing speed, inventory placement, and reliability. The lesson isn’t that boring always wins. It’s that the market’s favorite story and the market’s best compounding asset are often two different things.

Location Is the Ultimate Moat

You can fix a building. You can re-lease a space. You can run operations better.

What you can’t do is manufacture land in the places everyone suddenly needs to be. In supply-constrained coastal markets, the scarcity isn’t the warehouse—it’s the dirt underneath it. First Industrial’s emphasis on those markets is a bet on the one advantage competitors can’t simply replicate with money and enthusiasm.

Conservative Leverage Preserves Optionality

Real estate companies don’t usually die from slow quarters. They die when debt markets shut and they don’t have room to breathe.

Plenty of REITs that leaned too hard into leverage in the mid-2000s found themselves fighting for survival in 2008 and 2009. First Industrial’s comparatively conservative approach didn’t make the crisis easy, but it made it survivable. Balance sheet strength rarely gets celebrated in a boom. It’s what keeps you in the game when the cycle turns.

Development Creates Value, But Requires Discipline

Development is where industrial REITs can create real value—turning land into modern logistics space, and capturing the spread between cost and finished value.

But it cuts both ways. Speculative building at the wrong point in the cycle can be a fast way to destroy returns. First Industrial’s approach has been to push development when demand supports it, and to stay disciplined when conditions shift, rather than building simply because growth is available.

The REIT Structure Matters

REITs are a powerful vehicle: liquid ownership, tax efficiency, and a built-in requirement to return cash to shareholders through dividends.

But that structure also forces a tradeoff. Because REITs can’t retain most earnings, growth depends on continual access to capital markets—debt, equity, or both. If you’re evaluating a REIT, you’re never just evaluating the real estate. You’re evaluating the company’s ability to fund itself through cycles.

Mid-Size in a Scale Business Is Challenging

Industrial real estate has become a scale game—especially at the top end, where cost of capital and tenant relationships compound into real advantage.

First Industrial sits in a tricky middle ground: not the category giant with overwhelming scale advantages, and not a tiny niche player that can dominate a single micro-market. They’ve competed by focusing on portfolio quality, development, and execution. But the strategic tension doesn’t go away. In a consolidating industry, the question of long-term positioning is always in the background.

XIII. Epilogue: What's Next for Industrial Real Estate?

The Current Environment

By the mid-2020s, industrial real estate started to look less like a rocket ship and more like what it always becomes eventually: a market.

Cushman & Wakefield’s Industrial_Logistics Investor Outlook noted that U.S. industrial net absorption improved in the third quarter—up about 30% from the prior quarter and roughly 33% from a year earlier. Rent growth, while slower than the post-COVID surge, stayed positive. And with supply and demand expected to keep rebalancing into 2026, rent growth was projected to settle back into a more normal, sustainable range—around the 3% to 4% neighborhood.

That’s the broader story: normalization after the most distorted cycle the sector has ever seen. Development has been stepping down from record levels. Demand has cooled from the “grab anything you can find” panic of 2020 and 2021. Rent growth has come back to earth.

And that’s healthy. Markets that only go up don’t stay healthy for long. They just store up pain for later.

Emerging Demand Drivers

What’s interesting now is that the next wave of demand may not look exactly like the last one.

Industrial developers are increasingly moving into data centers—adjacent in some ways, very different in others. The data center sector has been growing rapidly as the digital economy expands, and the AI boom has only intensified the need for capacity. Developers already know how to do the hardest parts of the job: secure land, navigate entitlements, manage complex construction timelines. In that sense, the skill set transfers.

At the same time, the “stuff economy” is getting a new source of tailwind: manufacturing investment shifting back toward North America. Reshoring and nearshoring have been driven by supply chain resilience concerns, political pressure to reduce dependence on China, and incentives like the CHIPS Act. If more production happens closer to the end customer, the logistics footprint that supports that production usually grows with it—raw materials in, finished goods out, and more inventory held along the way.

Automation and Building Evolution

One of the quiet plot twists in industrial real estate is that warehouses are becoming power problems.

Location selection is still about highways, labor, and proximity to customers—but power availability is increasingly near the top of the list, especially for buildings supporting automation and advanced manufacturing. Across real estate portfolios, power and network densification have started to show up as real pricing catalysts.

Modern logistics facilities aren’t just big boxes anymore. They’re increasingly high-spec environments that need significant electrical capacity—for robotics, automation, sensors, and sometimes heavy climate control. That evolution has a side effect: it can make older buildings obsolete faster, especially the ones that can’t be upgraded efficiently. For landlords with development capability and well-located land, that can be an opportunity. For owners of yesterday’s product, it’s a warning.

The Ultimate Question

For First Industrial, the long-term question isn’t whether industrial matters. That part has been decided.

The question is structural: does First Industrial remain an independent public company, get acquired by a larger player, or go private? All three outcomes have plenty of precedent in the REIT world:

- Independence: keep executing—developing in the right markets, selectively acquiring, and recycling out of older assets

- Acquisition: become part of a larger industrial REIT or a diversified real estate company that wants more logistics exposure

- Privatization: a private equity buyer could take it private at a premium, betting they can create value with a different risk profile

First Industrial has executed well and built a credible platform. But in a category where scale keeps getting rewarded—and where the biggest player keeps getting bigger—the question of long-term positioning doesn’t go away.

The Warehouse That Delivered Your Last Amazon Order

Run the tape back to something simple: the last thing you ordered online.

That package didn’t teleport to your doorstep. It moved through a chain of buildings—sometimes more than one—where inventory was stored, picked, packed, staged, and handed off to the next link in the network. Somebody owns those buildings. Somebody paid to acquire them or develop them. Somebody keeps them running, keeps tenants happy, and keeps the lights on.

And every month, tenants—Amazon, FedEx, third-party logistics firms, retailers—write rent checks. In the REIT model, most of that income ultimately gets passed through to shareholders.

First Industrial is one slice of that invisible infrastructure. It’s not glamorous. It doesn’t have a consumer brand. It’s steel, concrete, asphalt, and access—big buildings near highways and population centers, doing the uncelebrated work of making modern life feel effortless.

Sometimes the best businesses are the ones nobody pays attention to—until the world changes, and it turns out they were standing in exactly the right place the whole time.

XIV. Further Reading & Resources

Essential References

-

First Industrial Realty Trust Investor Relations (investor.firstindustrial.com) - Annual reports, investor presentations, earnings calls, and SEC filings from 2010 to the present are the best primary source for how the company thinks, invests, and measures performance.

-

NAREIT (National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts) (reit.com) - A strong starting point for understanding the REIT model: how it was created, how it’s regulated, and how different property sectors behave across cycles.

-

"The Everything Store" by Brad Stone - Not a real estate book, but essential context. It explains the Amazon machine—and the logistics demands that helped turn warehouses into strategic infrastructure.

-

Prologis Research (prologis.com/research) - High-quality research on logistics real estate fundamentals, supply chain trends, and how demand evolves market by market.

-

Green Street Advisors - Independent REIT research and valuation work (subscription required). Helpful for understanding how the public markets price industrial REITs and why.

-

JLL and CBRE Industrial Market Reports - Broker research with market-level detail on supply, demand, vacancies, rent trends, and what’s getting built where.

-

Urban Land Institute (ULI) Research - Practitioner and academic work on real estate development, urban logistics, and the forces shaping the built environment.

-

SEC EDGAR Filings for FR - First Industrial’s 10-Ks, proxy statements, and 8-Ks—the most detailed view into financials, governance, and management’s own narrative about risks and strategy.

-

Cushman & Wakefield Industrial Reports - A useful quarterly pulse check on vacancy, net absorption, rent growth, and construction pipelines.

-

"Realty Check" by Sam Zell - A cycle-savvy investor’s perspective on how real estate really works: risk, leverage, timing, and why being early can feel indistinguishable from being wrong—until it isn’t.

XV. Final Thoughts

First Industrial’s story captures one of the most durable truths in business and investing: the biggest outcomes often come from sticking with an underappreciated idea long enough for the world to catch up—while staying disciplined enough to survive the years when it doesn’t feel rewarded.

Back in 1994, almost nobody would have bet that warehouses would become the most sought-after commercial real estate in America. The founders saw a fragmented market that could be consolidated and run professionally. They didn’t—and couldn’t—see Amazon’s logistics machine, smartphones turning shopping into a tap, or a global pandemic that would pull e-commerce forward by years.

What they did have was a structure built to compound: the REIT model, access to capital, an operating platform, and the patience to keep improving the portfolio through ugly cycles. When the opportunity finally arrived, they didn’t win because they predicted the future perfectly. They won because they were still standing—and because they’d quietly positioned the business to benefit when demand shifted.

The bigger lesson goes beyond industrial real estate. Infrastructure businesses that sit underneath massive consumer trends can create enormous value, even if the end customer never learns their name. The warehouse that moved the package containing the device you’re reading this on? Somebody owned it. Somebody collected rent on it. And in a REIT, a large share of that cash ends up back in investors’ hands.

Sometimes, the quiet giants are the ones worth watching.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music