FNB Corporation: The Story of a Regional Banking Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

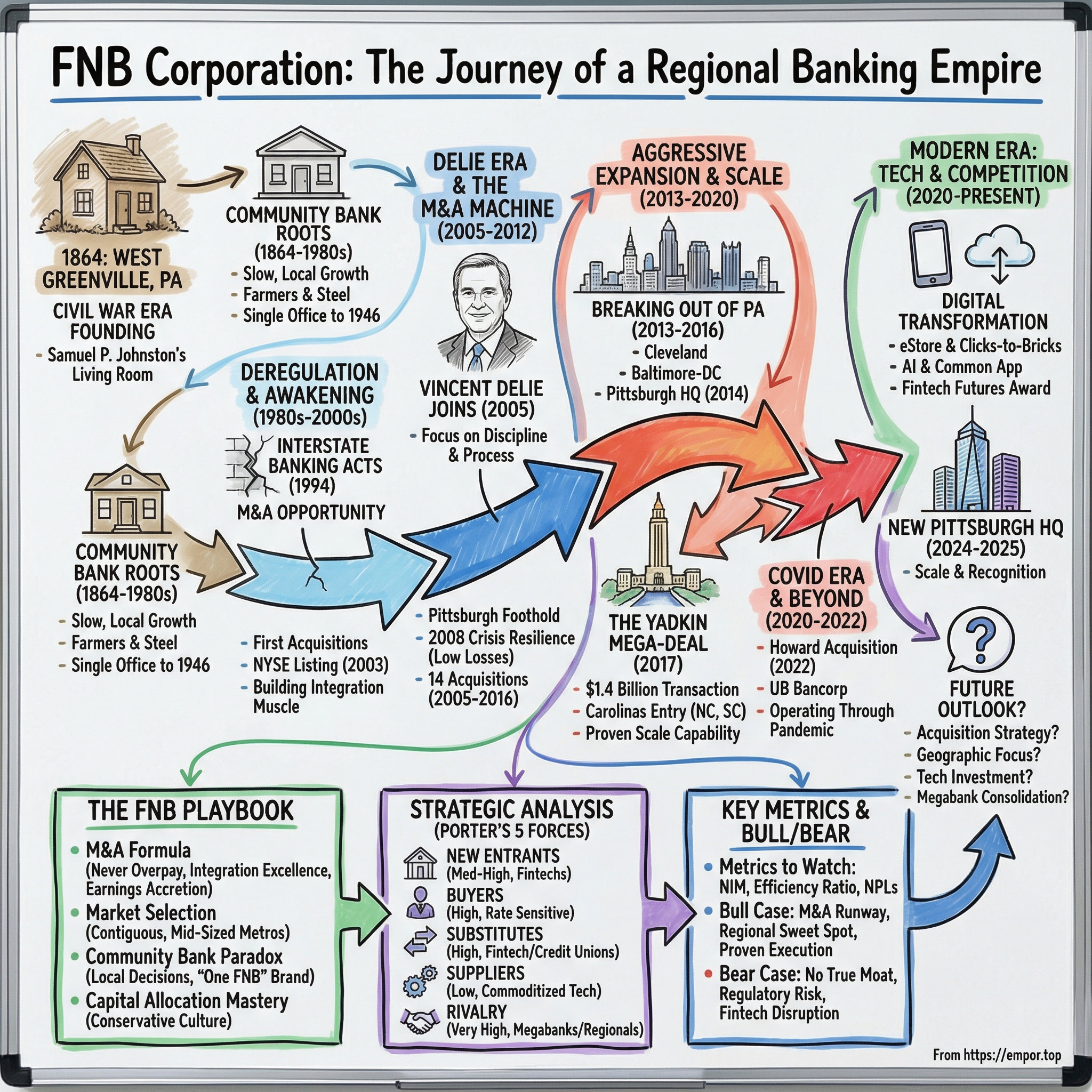

Picture this: It’s 1864, and the country is tearing itself apart. Abraham Lincoln signs the National Banking Act, creating a new class of federally chartered banks meant to help finance the Union war effort and bring order to a chaotic money system. In West Greenville, Pennsylvania—a rural speck in Mercer County—a man named Samuel P. Johnston sees an opening. He starts The First National Bank of West Greenville, and he does it the most literal way possible: out of his living room.

Now jump ahead 161 years. That living-room bank has become FNB Corporation, a diversified financial services company headquartered in Pittsburgh and the holding company for its biggest subsidiary, First National Bank. As of June 30, 2025, FNB has nearly $50 billion in assets, about 350 offices, and roughly 4,200 employees. Its footprint stretches across major metros and growth corridors—Pittsburgh, Baltimore, Cleveland, Washington, D.C., the Charlotte and Raleigh-Durham region and North Carolina’s Piedmont Triad, plus Charleston, South Carolina.

So how did a small-town Pennsylvania bank founded during the Civil War become one of the most acquisitive regional banks in America?

That question sits at the heart of the FNB story—and what makes it so compelling is what it isn’t. This isn’t a tale of Silicon Valley disruption. It isn’t financial engineering. It’s something rarer in corporate history: decades of disciplined, repeatable execution. The same basic playbook, run over and over again, getting sharper each time.

Because the tension here is real. Modern banking is a brutal sandwich: megabanks like JPMorgan Chase on top with almost $4 trillion in assets, fintechs like Chime and SoFi underneath trying to peel off customers product by product. Where does that leave a mid-sized regional bank?

FNB’s answer has been remarkably consistent: go where the giants won’t bother, buy and integrate smaller banks with relentless precision, and still keep the community-banking feel that makes customers stick around.

That’s the roadmap for this story. It’s a study in operational excellence in a commoditizing industry—and a reminder that, sometimes, the best strategy isn’t to reinvent the world. It’s to pick your lane, and then execute so well that your capabilities compound for decades. The open question, though, is whether that’s enough for the next era, with fintech innovation accelerating and scale advantages at the top end only getting stronger.

II. Founding & Early History: From Civil War to Steel Town Banking (1864–1980s)

1864 wasn’t just brutal on the battlefield. It was also a pivot point for American money.

While Grant pushed toward Richmond and Sherman readied his march, Congress was doing something quieter but just as consequential: rewriting the rules of banking. The National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 were, at their core, wartime infrastructure. The Union needed cash to pay and supply an army on a scale the federal government had never attempted. But the country’s financial system was a patchwork. Coins circulated alongside paper notes printed by state-chartered banks, and those notes didn’t travel well. A bill issued in one state might be accepted at a discount in another, or not accepted at all.

That fragmentation was a problem in peacetime. In wartime, it became dangerous.

So the federal government offered an elegant trade: a national charter in exchange for buying U.S. government bonds. Create a new class of “national banks,” require them to hold government debt, and you accomplish two things at once. You fund the war effort and you standardize the currency. By the end of 1864, 683 banks had taken those federal charters.

One of them was in Mercer County, Pennsylvania.

That year, The First National Bank of West Greenville opened for business—operating, quite literally, out of the home of its president, Samuel P. Johnston, in Greenville, Pennsylvania. It wasn’t a grand launch. It wasn’t a visionary bet on the future of finance. It was one more small bank stepping into a new federal framework and serving a local community.

In the 1880s, the town dropped “West” from its name, and the bank followed suit, rechartering as The First National Bank of Greenville. Through World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II, it stayed exactly what it sounded like: a community bank rooted in northwestern Pennsylvania.

And that’s the key point of this era. What’s remarkable about the first hundred years of FNB’s life is how ordinary they were.

The bank served the Shenango Valley’s farmers, families, and small businesses. The region rode waves of industrial change—oil, steel, and all the boom-and-bust volatility that came with them—while the bank remained a steady local utility. In 1946, it still had a single office and roughly $2 million in assets. No dramatic expansion. No near-death collapse. Just steady community banking.

That context matters because it reframes what comes later. FNB didn’t start as a “platform.” It wasn’t born with a grand strategy. For decades, it looked like thousands of other small-town banks spread across America: important to its customers, but not yet special in the national story.

Then, slowly, it began to change shape.

Over the next few decades, the institution grew, and in 1974 it took a meaningful structural step: FNB Corporation was formed as a financial services holding company for a growing set of businesses. Under that umbrella sat the bank—then operating as The First National Bank of Mercer County with about $120 million in assets—along with Regency Finance Company.

A holding company doesn’t automatically make you an empire. But it does signal a mindset shift. It’s a way of saying: we’re not just a single-bank operation anymore, and we want the flexibility to own, build, and acquire.

Still, the world around FNB hadn’t changed enough for that ambition to really matter. Before the 1980s, banking was tightly regulated and geographically boxed in. Most banks lived inside narrow boundaries, competition was limited, and the concept of building a multi-state franchise was more fantasy than strategy.

That was about to break open.

III. Deregulation & the M&A Opportunity (1980s–1990s)

The story of American banking in the 1980s and 1990s is, at its core, a story about walls coming down.

For decades, regulation kept banks in tight geographic boxes—a Depression-era reflex against financial concentration. Most institutions lived and died inside their home counties and states. Then, in the early 1980s, states started cutting reciprocal deals that allowed out-of-state banks to enter—carefully, and usually only if the neighboring state offered the same access in return. Consolidation began as a local affair. In the first half of the decade, mergers were mostly in-state because cross-border deals simply weren’t allowed. In the second half, as states loosened up—often limiting new combinations to contiguous states—regional rollups started to form.

The real inflection point arrived in 1994 with the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act. In plain English: banks could now operate branches across state lines. Overnight, what had been a patchwork of thousands of insulated institutions started to feel like one national arena. And with that, every community bank faced the same blunt question: do we consolidate, or do we get consolidated?

The 1990s delivered the answer with force. Over the decade, there were 6,020 bank and thrift mergers.

Pennsylvania turned into one of the hottest battlefields. Pittsburgh-based giants PNC and Mellon were actively stitching together bigger franchises, building the kind of scale that could drown smaller competitors. For a bank like FNB, the math got simple: staying small wasn’t a strategy—it was an exit plan.

FNB’s first meaningful moves were modest but revealing. In July 1992, it acquired ten branch offices from First National Bank of Pennsylvania. Along with those branches, it took something else: the name. First National Bank of Mercer County formally became First National Bank of Pennsylvania. On paper, it looked like a branding update. In reality, it was a declaration of intent. This bank no longer wanted to be defined by one county.

More important than the signage was what the deal taught them. You don’t become a great acquirer by doing one big, heroic transaction. You become one by doing a lot of small ones and learning, step by step, how to evaluate targets, price risk, convert systems, keep employees, and—most critically—hold onto customers through the chaos of change. FNB was starting to build that integration muscle.

By 2003, the results were hard to miss. The company had grown to $4.6 billion in assets, operated more than 125 banking offices, and began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker FNB.

The NYSE listing wasn’t the strategy. It was the signal that the strategy was working—and that FNB now had the visibility and access to capital markets to keep going. Because by the end of this era, the philosophy that would define the next two decades was coming into focus: find markets the megabanks won’t fight over, buy community banks with real relationships and clean balance sheets, integrate them cleanly, and repeat.

Not glamorous. Not flashy. Just relentlessly compounding execution.

IV. The Vincent Delie Era & Transformation Into an M&A Machine (2000s–2012)

In 2005, FNB made a hire that would end up defining the next era of its growth. Vincent J. Delie, Jr. joined the company that year to run the Pittsburgh Region. At the time, FNB was still a roughly $5.6 billion community bank headquartered in Hermitage, Pennsylvania—about an hour from Pittsburgh. Delie’s job was straightforward on paper and brutal in practice: go build a real business in the Steel City.

He came from National City Bank, the big Ohio-based player that had a meaningful presence in the region. It was a solid role, but by 2005, Delie felt he’d hit a ceiling. FNB’s pitch was the opposite: a chance to build.

Before he jumped, he did what good bankers do—he tried to quantify the problem. He hired a market research firm to gauge FNB’s standing in Pittsburgh. The verdict was harsh: First National Bank of Pennsylvania didn’t even “fog the glass” there. In other words, the bank barely registered.

That starting point mattered. Pittsburgh wasn’t some open frontier. It was entrenched territory, dominated by giants like PNC, Mellon, and National City. If FNB wanted to become anything more than a rural Western Pennsylvania bank with ambitions, it needed a foothold in its nearest major metro. That meant strategy, yes—but also years of grinding execution.

Delie’s life had trained him for that kind of grind. He’s spoken about struggling in school and later learning he has dyslexia. He paid his own way through college, then got laid off from his first job as a stockbroker after the 1987 market crash—right when he had student loan debt and bills to pay. He moved back in with his parents, regrouped, and took a trading desk job at PaineWebber.

From there, he joined Equibank, a Pittsburgh institution that ultimately closed in 1993. During the savings and loan crisis, he was still early in his career, in a management trainee program—and he stayed employed while many people around him were cut because he was doing loan review. In other words: learning credit the hard way, in the middle of chaos.

That biography isn’t just color. It shaped how Delie led. He had watched what happens when underwriting gets sloppy and when institutions pretend cycles don’t exist. He valued discipline, process, and repeatability—traits that become incredibly powerful when your strategy is “buy, integrate, and do it again.”

At FNB, he rose quickly. He started in 2005 as President of the Pittsburgh Region, then began taking on broader executive leadership roles in 2008. In 2009, he joined the First National Bank Board of Directors and became the bank’s President, later moving into the CEO role. In 2011, he was named President of FNB Corporation. And in 2012, he reached the top job: Chief Executive Officer of FNB Corporation, effective January 18, 2012.

He succeeded Stephen J. Gurgovits, who shifted to Chairman of the Board. It was a generational handoff, and the company Delie inherited was already far larger than the one he’d joined. Gurgovits had spent 50 years at FNB, and during his tenure as CEO, the corporation completed eight bank mergers and grew assets from $3.8 billion to $12 billion.

So Delie didn’t have to invent FNB’s strategy. The machine was already being built. His task was to professionalize it, scale it, and keep it pointed in the same direction.

The timing mattered. The 2008 financial crisis was both a stress test and an opening. While many banks were drowning in toxic assets and collapsing loan portfolios, FNB’s credit performance held up better than most. Its peak net charge-offs as a percentage of loans—1.15%—were well below peers during the crisis, and its capital ratios stayed above the regulatory “well-capitalized” thresholds. That conservative culture—especially its avoidance of the subprime excesses that wrecked competitors—left FNB in the position every bank wants when the cycle turns: strong enough to buy, not forced to sell.

And it did. In the third quarter of 2008, FNB completed the acquisition of Iron and Glass Bancorp, Inc., strengthening its presence in Pittsburgh. The deal added a $167 million loan portfolio, $254 million in deposits, and $310 million in total assets.

This was the pattern taking shape in real time. While others retrenched, FNB leaned in—selectively, and with a clear preference for building density in markets it cared about. The strategy was crystallizing: roll up community banks in contiguous geographies, price deals with discipline, take out costs, keep relationships intact, and repeat.

By the time the decade turned, that approach had become FNB’s identity. Between 2005 and 2016, FNB completed 14 acquisitions and reached top retail deposit share in three major metro areas: Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Baltimore.

This era established the template that would define everything that came next: disciplined, serial acquisition executed with operational precision.

V. The Pivotal Decade: Aggressive Expansion & Scale Building (2013–2020)

A. Breaking Out of Pennsylvania (2013–2016)

By 2013, FNB had proven it could win in Pennsylvania and push into Ohio. But the logic of modern banking was getting harder to ignore: bigger banks could spread the rising costs of technology, compliance, and competition over a much larger base. If FNB wanted to stay in the game—let alone keep playing offense—it needed more scale.

So it started placing bets outside its home turf.

In 2013, FNB acquired PVF Capital Corp., the parent of Park View Federal Savings Bank, giving it an entry point into the Cleveland market.

Then came Maryland. BCSB Bancorp, Inc.—the holding company for Baltimore County Savings Bank—ran a network of 16 offices across the greater Baltimore area. In 2014, FNB acquired BCSB, expanding its presence in Maryland.

Those Maryland moves mattered because they weren’t just about adding branches. They were about upgrading the map. The Baltimore–Washington corridor offered growth dynamics that Pennsylvania and Ohio couldn’t match, and FNB leaned into that logic again with the acquisition of OBA Financial Services, Inc., the Germantown, Maryland-based parent of OBA Bank. The deal expanded FNB’s footprint along the Interstate 270 corridor—one of the region’s key commuter and business arteries.

And in July 2014, FNB made the shift official: Pittsburgh was named the corporation’s headquarters. It was more than a plaque on a building. It was an acknowledgment of what the company had become—a Pittsburgh-centric bank building a multi-state franchise, not a small-town institution that happened to grow.

The numbers told the same story. In Pittsburgh alone, FNB had gone from a single banking office in 1997 to nearly 100 locations and a top-three retail deposit market share.

FNB kept filling in the chessboard. In 2015, it acquired Metro Bank (formerly Commerce Bank) of Harrisburg. Later that year, on September 3, 2015, it announced the acquisition of 17 Pittsburgh-area branches and $383 million in deposits from Fifth Third Bank. And with the Metro Bancorp, Inc. merger—adding more than 30 offices in Central Pennsylvania—FNB became the second largest bank in Pennsylvania by assets.

Then, in 2016, it lined up the deal that would change the company’s trajectory: an agreement to acquire Yadkin Financial of Raleigh, North Carolina in a $1.4 billion transaction—the largest in FNB’s history.

B. The Mega-Deal Era: Yadkin Financial (2016–2017)

The Yadkin deal was the inflection point—the moment when FNB proved it could do more than roll up small community banks. This was a large, complex transaction that would reshape its footprint and force the organization to scale its playbook.

On July 26, 2016, FNB and Yadkin Financial Corporation announced a definitive merger agreement under which FNB would acquire Yadkin in an all-stock transaction valued at approximately $27.35 per share, or about $1.4 billion in the aggregate, using FNB’s 20-day trailing average closing stock price as of July 20, 2016.

Strategically, Yadkin brought an immediate Southeastern platform: a North Carolina-based franchise with a major presence in both North Carolina and South Carolina. The acquisition would add billions in assets, deposits, and loans, along with roughly 100 banking offices across the two states. On a pro-forma basis, the combined company would approach $30 billion in total assets and operate more than 400 full-service banking offices.

FNB leadership framed the deal as a step-change, not an incremental addition. Vincent J. Delie, Jr. said the combination “transforms FNB’s growth profile and creates a premier regional bank with an expanded footprint across the Mid-Atlantic and Southeast.”

It also came with a twist: Yadkin was no sleepy hometown bank. It had been an aggressive consolidator itself, including a $456 million acquisition of NewBridge Bancorp in March 2016 that helped build its scale in the Carolinas. FNB wasn’t buying a simple branch network—it was absorbing an organization that had been doing M&A at speed.

The merger closed on March 11, 2017. And this is where the real test began.

If FNB fumbled the integration, it would throw the entire strategy into doubt. Instead, the integration moved forward smoothly—validating the M&A machine FNB had been sharpening for decades.

FNB didn’t just buy its way into the Carolinas; it planted a flag. In May 2017, it announced a regional headquarters in Raleigh: a 22-story building that would be called FNB Tower. Groundbreaking came in December 2017, and the building opened in December 2019. In March 2018, FNB announced it would also anchor a 31-story tower in Charlotte—FNB Tower Charlotte—which was completed and opened in July 2021.

C. The Howard Acquisition and COVID Era (2020–2022)

The next major step came back in the Mid-Atlantic.

In July 2021, FNB Corporation and Howard Bancorp, Inc. announced a definitive merger agreement for FNB to acquire Howard—along with its wholly-owned subsidiary, Howard Bank—in an all-stock transaction valued at $21.96 per share, or approximately $418 million, based on FNB’s closing stock price as of July 12, 2021.

Howard, headquartered in Baltimore, had $2.6 billion in total assets at March 31, 2021, along with $2.0 billion in total deposits and $1.9 billion in total loans and leases. It operated 13 full-service offices across Baltimore and the greater Washington, D.C. area. The merger further strengthened FNB’s Mid-Atlantic position, with the combined organization projected to hold the sixth largest deposit share in Baltimore, Maryland. FNB also expected the deal to be 4 percent accretive to earnings per share with fully phased-in cost savings on a GAAP basis.

FNB completed the merger on January 22, 2022, with customer and branch branding conversion scheduled to be finalized on February 7, 2022. After the Howard transaction, FNB reported approximately $42 billion in total assets, $27 billion in total loans, and $33 billion in total deposits.

All of this unfolded against the backdrop of the COVID pandemic—a stress test that hit banks in exactly the places regional franchises tend to feel most exposed. Digital adoption surged. Credit concerns spiked across the industry. Branch traffic fell hard. But FNB’s operating model held up, and it kept moving.

In June 2022, FNB announced the purchase of UB Bancorp of Greenville, North Carolina, adding Union Bank’s 15 branches and $1.2 billion in assets in a stock transaction valued at $117 million.

VI. The Modern Era: Scale, Technology & Competition (2020–Present)

The post-pandemic banking landscape handed FNB a real paradox. Digital habits had snapped into place almost overnight, calling into question the value of a big physical branch network. At the same time, the regional bank model proved tougher than many expected, and FNB’s conservative underwriting helped it avoid the kind of credit damage that took down less disciplined peers.

Under Vincent Delie’s leadership, FNB kept doing what it does best: expand—both by acquisition and by building capabilities. Alongside 17 acquisitions, the company materially upgraded its digital platform and broadened its product set. Over his tenure, FNB’s market capitalization rose by nearly 600 percent.

The clearest signal of FNB’s response to the digital era is how hard it leaned into technology without abandoning the physical footprint that defines “relationship banking.” The centerpiece is eStore, a proprietary digital banking experience that has picked up meaningful industry recognition.

eStore sits at the heart of Clicks-to-Bricks, FNB’s omnichannel strategy. The idea is simple: meet customers wherever they are, and make the “how” of banking interchangeable. Through online and mobile channels—or through interactive in-branch kiosks—customers can shop for products, open accounts, apply for loans, book appointments, and access financial education resources.

That approach earned outside validation. In June 2024, eStore was named Best Digital Initiative at the 2024 Banking Tech Awards USA. Fintech Futures recognized FNB for executing a technology-driven customer banking initiative built around a digital proposition.

FNB has also pushed toward a cleaner, more unified customer experience with the eStore Common app. The ambition is big: a single, universal application for almost all products and services, including the ability to apply for multiple products at the same time. Using advanced technology—including artificial intelligence and machine learning—the Common app is designed to make applications faster and more secure.

Delie said eStore and the Common app are powered by AI and a large data warehouse, enabling automation not only in opening accounts digitally but also in generating personalized product recommendations. Submissions through the eStore Common app rose 108 percent from the first quarter of 2025 to the second.

Even the company’s physical headquarters tells the story of scale. FNB moved into FNB Financial Center in November 2024 and held a grand opening in February 2025. The timing lined up with a wave of recognition for Delie, and the building itself was designed to match the growth FNB achieved during his tenure. It also anchors a larger urban redevelopment effort expected to drive more than $1 billion in economic expansion in Pittsburgh’s historically underserved Hill District.

From the 26th floor, Delie looks out over downtown Pittsburgh from an office suite he had designed to echo the layout of JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s executive offices in New York. The space features black-and-white marble and a material called Marvel, which mimics marble.

Operationally, FNB’s performance has remained solid. For the fourth quarter of 2024, it reported net income available to common stockholders of $109.9 million, or $0.30 per diluted common share, compared with $48.7 million, or $0.13 per diluted common share, in the fourth quarter of 2023.

FNB also strengthened liquidity and capital. It improved its loan-to-deposit ratio by more than 500 basis points from its 2024 peak through strong deposit originations, and it posted higher capital ratios with a record CET1 ratio of 10.6%. Tangible book value per share (non-GAAP) rose 11% year-over-year to a record $10.49.

For full-year 2024, operating EPS was $1.39, reflecting execution against strategic objectives. It generated 5% year-over-year loan growth and 6.9% deposit growth across its diversified footprint—results that materially outpaced the industry.

Into 2025, profitability trends continued to firm up. In the third quarter of 2025, pre-provision net revenue (non-GAAP) grew 11% linked-quarter, contributing to positive operating leverage and a peer-leading efficiency ratio of 52%. Capital levels reached new highs, with an estimated CET1 regulatory capital ratio of 11%, tangible book value per share up 11% year-over-year, and return on tangible common equity of 15%.

Recognition followed the results. Delie was selected as CEO of the Year from more than 500 nominees across industries. In naming him the winner, The CEO Magazine cited his focus on shareholder value creation and his strategic guidance in building FNB into one of the 50 largest bank holding companies in the U.S.

In April 2025, Brand Finance also named Delie one of the top 50 CEOs in the U.S., placing him in its Brand Guardianship Index among leaders of the country’s most respected companies. He ranked in the top five bank CEOs in the U.S.

VII. The FNB Playbook: What Makes This Model Work

The M&A Formula

FNB’s edge isn’t that it buys banks. Lots of banks buy banks. The difference is that FNB has turned doing it well into a repeatable craft—one that’s been pressure-tested across decades, cycles, and geographies. The formula is simple to describe, hard to execute, and even harder to sustain.

Never overpay. It’s the oldest rule in M&A, and the one most likely to get ignored the moment competition heats up. FNB has built a reputation for sticking to its price and walking away when valuations get stretched. That restraint matters because it protects the core promise that makes the whole strategy work: acquisitions shouldn’t just make the company bigger; they should make it better.

Integration excellence. Buying a bank is the easy part. The real risk shows up after the press release—when systems have to convert, processes have to align, employees have to stay, and customers have to feel like nothing broke. FNB has gotten good at that unglamorous work through repetition. And when it needed to prove it could do this at scale, the Yadkin deal was the proof point: nearly 100 branches brought onto FNB’s platform without the kind of chaos that can quietly destroy the economics of a merger.

Earnings accretion focus. FNB doesn’t treat acquisitions as trophies. The deal has to improve earnings, not just add footprint. That discipline forces trade-offs—sometimes slower growth, sometimes fewer deals—but it also keeps the machine from turning into an empire-building exercise.

Market Selection Strategy

FNB’s map tells you a lot about how it thinks. It expands contiguously, building outward market by market instead of hopping across the country. That approach creates density—shared infrastructure, deeper brand awareness, and more efficient operations.

Just as important is where it chooses to play: mid-sized metros and suburban corridors like Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Baltimore, and the Carolinas. These are markets where scale still matters, but the megabanks don’t always bring their full weight to bear. That’s FNB’s sweet spot: big enough to build real share, small enough to win on relationships.

The Community Bank Paradox

Here’s the balancing act at the center of FNB’s story: how do you scale up without losing the thing customers actually value in a community bank—local decision-making and personal trust?

FNB’s answer has been structural. Lending decisions stay closer to the market. Local leaders have real authority. The company pushes a “One FNB” brand, but it doesn’t try to run every market like a centralized factory. And technology plays a supporting role: the better the digital platform and back office run, the more time relationship managers can spend doing the one thing software can’t replicate—being present for customers.

Capital Allocation Mastery

All of this depends on having the balance sheet to keep playing offense.

FNB’s culture of conservatism—disciplined underwriting, not chasing marginal loans, staying prepared for downturns—has helped it keep credit losses low through cycles. And that stability gives management options: invest in the business, return capital to shareholders through dividends or buybacks, and still preserve capacity for opportunistic acquisitions when the timing is right.

That’s the real compounding advantage here. The playbook isn’t one move. It’s the ability to keep making the next move.

VIII. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Medium-High

The new entrants aren’t opening branches on street corners. They’re showing up on your phone.

Fintech challengers like Chime and SoFi have proven they can gather deposits and deliver core banking experiences without building traditional infrastructure. The catch is that becoming a true, full-service bank is still hard. Regulation, compliance, and the sheer operational burden of banking remain real barriers. That’s where FNB has an edge: an established franchise, a physical presence that still matters in many communities, and the institutional muscle to operate inside a heavily regulated industry.

So the threat is meaningful, but not existential. Fintechs tend to win narrow use cases. Regional banks win the full relationship.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low

On the vendor side, most banks buy from the same universe of core systems and technology providers. It’s competitive, it’s commoditized, and at FNB’s scale, the company can usually negotiate from a position of strength.

But in banking, the most important “input” isn’t software. It’s deposits. And competition for deposits has intensified across the industry, raising funding costs and turning deposit gathering into a daily knife fight.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High

Customers can switch banks, and they do—especially when rates move. That’s true on both sides of the balance sheet: depositors chase yield, borrowers shop terms.

FNB’s defense is to make the relationship bigger than the rate. Bundled services, local decision-making, and the kind of day-to-day integration that comes from doing more for a customer all increase stickiness. The eStore platform is built for exactly this: increasing “products per household,” the quiet metric that often determines whether a customer is loyal or just passing through.

Threat of Substitutes: High

Substitutes are everywhere. Fintechs siphon off payments, credit cards, and consumer lending. Credit unions remain formidable in consumer banking. And for many businesses, capital markets can be an alternative to traditional bank lending.

FNB’s counter is depth. A full-service relationship—especially in small business and commercial banking—doesn’t replace easily. Transactional products can be unbundled. Trusted banking relationships are harder to replicate.

Competitive Rivalry: Very High

This is the brutal reality of modern banking: pressure from every direction.

From above, megabanks like JPMorgan, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo can outspend almost anyone on technology, marketing, and pricing. From below, community banks compete on local intimacy. And across the middle, credit unions and fintechs pick off high-value product lines.

In FNB’s regional peer set, competitors include PNC Financial Services Group, Truist Financial, KeyCorp, Huntington Bancshares, and Fifth Third Bancorp. In the community banking tier, it also competes with S&T Bancorp, Northwest Bancshares, and WesBanco.

FNB’s bet is that it can live in the “Goldilocks zone”: big enough to have real scale economics, small enough to keep the relationship banking edge.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: ⭐⭐⭐

Scale is one of the reasons FNB has been so determined to keep getting bigger. Technology, compliance, and back-office operations don’t scale linearly; spreading them over nearly $50 billion in assets creates real efficiency advantages versus smaller banks. Density in key markets also makes the branch network more productive.

But it’s important to be clear about what kind of scale this is. FNB doesn’t have JPMorgan or Bank of America scale. Its edge is relative—strong against smaller regionals and community banks, not absolute across the industry.

Network Economies: ⭐

Limited. Banking doesn’t behave like social networks or marketplaces where winners pull away through network effects. There are modest benefits from things like ATM networks and merchant relationships, but they don’t create winner-take-all dynamics.

Counter-Positioning: ⭐⭐

FNB’s pitch against megabanks is straightforward: local decision-making, relationship focus, and an ability to serve mid-market businesses without treating them like a rounding error.

That’s real counter-positioning, and megabanks can’t fully replicate it without changing how they’re built. Still, it’s not exclusive to FNB—many regional banks sell a similar story.

Switching Costs: ⭐⭐⭐

Switching costs are where banking gets sticky—especially for businesses. Credit lines, treasury management, and operational workflows create real friction once a company is embedded with a bank.

Retail is different. Consumers can move their money with a few clicks, and loyalty often lasts only as long as the last promotional rate. FNB’s strategy here circles back to the same lever: increase the number of products per household so leaving becomes inconvenient, not just possible.

Branding: ⭐⭐

FNB’s brand is strongest where it’s been for decades—core Pennsylvania and Ohio markets. It’s naturally weaker in newer territories like North Carolina and South Carolina, where it’s still earning mindshare.

And in general, regional bank brands live in an awkward middle ground: they rarely carry the universal trust of national giants, and they often don’t have the hyper-local identity of a hometown community bank.

Cornered Resource: ⭐

There’s no single locked-up asset here—no unique technology advantage, no exclusive regulatory position. Management quality is a strength, but talent can be matched over time.

Process Power: ⭐⭐⭐⭐

This is the heart of the FNB story.

FNB’s M&A integration playbook has been sharpened over more than 20 years and 17-plus acquisitions. It pairs disciplined underwriting with a credit culture that has produced consistently low charge-offs through cycles. And it has the operational capability to take out costs and realize synergies without alienating customers—something that sounds simple and routinely destroys mergers when it’s done poorly.

That’s not an accident. It’s learned behavior, built over repetition. And it’s genuinely hard to copy without living through the same reps.

Overall Assessment: FNB’s real power comes from a combination of scale economies and process power—especially in acquisition and integration. This is a “better operations” story, not a classic moat story. The advantage is real, but it only stays real if FNB keeps executing.

IX. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

M&A runway remains long. Even after decades of consolidation, the U.S. banking industry is still crowded. With more than 4,600 banks left in the country—and well over a thousand community bank mergers completed in just the last decade—there’s still plenty of wood to chop. FNB has spent years building the muscle memory to source deals, price them, integrate them, and move on to the next one.

Regional bank sweet spot. FNB is big enough to afford real technology and compliance, but not so big that it gets treated like a systemically important institution. That matters, because the heaviest regulatory burdens fall on the very largest banks, forcing them to carry more capital and liquidity. That gap has historically created a meaningful return on equity advantage for major regional banks versus the GSIBs—an advantage FNB can potentially keep exploiting as it scales.

Proven execution. This is the strongest part of the bull case: FNB has actually done the thing it says it’s good at. It has a track record of integrating acquisitions, growing earnings, and maintaining credit discipline through cycles. Plenty of banks talk about being good operators. Far fewer have the reps.

Geographic diversification. A footprint spanning seven states plus Washington, D.C. reduces the risk that one local economy sinks the whole ship. It also balances the portfolio: faster-growing markets in the Carolinas and the Mid-Atlantic can help offset slower growth in Pennsylvania and Ohio.

Management continuity. The strategy hasn’t depended on a revolving door at the top. Delie has remained CEO, and CFO Vincent Calabrese has been with the company since 2007. That continuity matters in banking, because the “culture” is often just another word for underwriting discipline and operating habits—things that don’t survive constant leadership resets.

Digital investment. FNB’s eStore platform is evidence that the company isn’t trying to win 2025 with a 1995 playbook. The bet is that technology can improve efficiency and deepen customer relationships, rather than simply becoming a defensive cost line item.

The Bear Case

No true moat. FNB’s advantage is real, but it’s not untouchable. Process power can be copied, slowly. Other regionals can improve their integration playbooks, hire talent, and close the gap. If FNB’s execution slips, the “we’re great at M&A” narrative can erode faster than you’d think.

Regulatory risk. Bank regulation is full of cliffs, not gentle slopes. The industry tends to cluster around asset thresholds because the rules get tougher as you cross them. As FNB moves toward $50 billion in assets, supervisory intensity increases. And looming shifts like Basel III endgame or other changes to capital requirements could pressure returns.

Fintech disruption. Deposits, payments, and lending—the building blocks of banking economics—are all being attacked by technology-forward competitors. FNB has invested heavily in digital, but the open question is whether traditional banks can innovate at the speed of pure-play fintechs, especially as customer expectations keep moving.

Commercial real estate exposure. Like most regional banks, FNB operates in an industry where commercial real estate is a common concentration risk. The post-pandemic reset in office usage has already strained parts of the system, and further weakness could pressure loan portfolios across the sector.

Rate sensitivity. Banking is still, at its core, a spread business. When rates rise, margins can expand; when rates fall, that tailwind can become a headwind. FNB’s net interest margin was 3.09% in 2024, down from 3.35% in 2023—a reminder that the rate environment can swing earnings more than management teams like to admit.

Acquisition targets drying up. Consolidation works best when there are plenty of attractive sellers at sensible prices. If the best targets are already gone—or if competition among consolidators pushes valuations too high—future deals may stop being meaningfully accretive.

Branch network liability. A big footprint can be an asset in relationship banking, but it’s also expensive. Even with strong digital capabilities, FNB still runs roughly 350 branches—real fixed costs in a world where more customers do more banking without ever walking inside.

Key Metrics to Monitor

For investors tracking FNB, three metrics stand out as most important:

-

Net Interest Margin (NIM): The spread between what FNB earns on loans and pays on deposits is the core driver of profitability for any bank. Changes in NIM signal competitive dynamics (deposit costs), portfolio quality (loan yields), and rate environment impacts.

-

Efficiency Ratio: The ratio of non-interest expense to revenue indicates operating leverage. FNB’s peer-leading efficiency ratio of around 52% reflects the benefit of scale and integration discipline. Deterioration would signal cost pressures.

-

Non-Performing Loans (NPL) and Net Charge-Offs: Credit quality is the existential question for any bank. Non-performing loans were 0.47% in 2024, up from 0.33% in 2023. Continued deterioration would signal portfolio stress.

X. What Would We Have Seen Coming? What Did We Miss?

If we’d done this episode in 2010, would we have called the Yadkin deal—the moment FNB vaulted from a Western Pennsylvania consolidator into a true multi-state regional bank?

Probably not with confidence. But we would’ve seen the ingredients.

By then, FNB had already proven it could buy and integrate smaller institutions without blowing itself up. Management was openly chasing scale. Deregulation and industry economics were pushing every community bank toward the same fork in the road: sell, or become the buyer. And the 2008 crisis had done something even more important—it had validated FNB’s conservative credit culture at the exact moment the industry was punishing anyone who’d reached for growth at all costs.

In other words, the setup was there. What came next wasn’t a surprise strategy. It was the disciplined execution of an obvious one.

The real surprise is how long FNB kept that discipline intact. Lots of companies can articulate a plan. Far fewer can run it year after year without drifting into empire-building, overpaying, or losing control of integration. Yadkin, Howard, and the push into digital weren’t left turns—they were step-ups. Bigger moves, same playbook.

And that’s the investing lesson here. In banking, boring often wins. The institutions that made it through 2008—and through the regional bank stress that hit the sector in 2023—tended to be the ones that resisted the temptation to chase yield, stretch underwriting, or buy growth they couldn’t digest.

What’s still unresolved is whether this model holds for the next twenty years. The pressure from both directions keeps increasing: fintechs unbundling products from below, and megabanks compounding scale advantages from above. FNB has responded with real technology investment, but the broader question remains: can a regional bank sustain an edge in an industry where the rules are still being rewritten?

The fintech question is the sharpest version of that challenge. FNB’s eStore and broader digital build-out narrow the gap, but pure-play fintechs still have structural advantages in speed, recruiting, and focus. The likely answer is that banking doesn’t collapse into one winner. Different customers want different things. And for the segments FNB prioritizes—commercial clients, small businesses, and wealth relationships—trust, local decision-making, and full-service depth can still matter more than having the slickest app.

XI. Epilogue & Looking Forward

FNB entered 2026 with real momentum. In the second quarter of 2025, it generated $412.9 million in revenue, and over the last twelve months that totaled $1.55 billion—up year-over-year.

But the next chapter, like it always is in banking, depends on the backdrop. And the biggest variable is interest rates.

As the Federal Open Market Committee began cutting, yields on earning assets moved lower, pressuring net interest income. In the fourth quarter of 2024 alone, the Fed reduced the target federal funds rate by a total of 50 basis points, bringing the year-to-date decrease to 100 basis points.

For a regional bank, the sweet spot is rarely “higher forever” or “lower forever.” It’s stability. A normal-for-longer rate environment tends to be the more workable setup—one where balance sheets can be managed with less whiplash and where revenue and earnings can compound in a more predictable way.

That’s the setting. Now comes the set of choices that will shape what FNB becomes next.

Strategic questions ahead for FNB include:

Acquisition strategy. Does FNB keep buying, or does it slow down and focus on organic growth while it digests what it already owns? The FDIC has indicated plans to prioritize streamlining the approval process for proposed bank mergers. If the regulatory tone becomes more accommodating, FNB’s long-built M&A muscle could matter even more.

Geographic focus. Does FNB keep pushing into new markets, or deepen share where it already has density? The Carolinas still represent a growth engine. Pittsburgh and Cleveland are proven strongholds—but more mature ones, where gains come from share capture and product expansion rather than population growth.

Technology investment. Build, buy, or partner? FNB has shown it can build internally (eStore), and it has also shown a willingness to work with fintech partners. The question isn’t whether it will invest—it’s how it will allocate effort and capital between proprietary platforms and partnerships.

Then there’s the question hanging over the entire regional banking sector: what does “regional” even mean in the next decade?

Some analysts believe the next consolidation wave could produce as many as seven new megabanks with more than $1 trillion in assets over the next five to ten years. If that happens, where does FNB sit? Is it one of the buyers assembling the next tier? Does it become a target? Or does it carve out a durable middle by becoming even better at what it already does?

If history is any guide, FNB’s answer won’t be a dramatic reinvention. It will be the same thing that got it here: disciplined execution of a familiar playbook, paired with tactical adaptation as conditions change. This company hasn’t won by making bet-the-company leaps. It has won by doing the basics—pricing, underwriting, integration, efficiency, relationship banking—better and more consistently than most.

That’s the lesson for investors, too. FNB doesn’t have a magical moat that makes competition disappear. It’s operating excellence in a commoditizing industry, compounded over decades. Whether that remains enough as banking keeps evolving is still the central question. But after 161 years of surviving wars, depressions, deregulation, crises, and technological shifts, dismissing FNB has never been a smart bet.

XII. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Resources for FNB Corporation Research

-

FNB Corporation Annual Reports and Investor Presentations (2010-present) — Start here. They’re the clearest window into how management explains the strategy, measures performance, and thinks about capital, credit, and acquisitions. Available at fnb-online.com.

-

FDIC Historical Statistics on Banking — The best backdrop for FNB’s entire arc: deregulation, bank failures, consolidation, and how the industry’s center of gravity shifted over time.

-

S&P Global Market Intelligence Bank M&A Database — The gold standard for bank deal history: who bought whom, at what price, and what the market was paying across cycles.

-

Federal Reserve Bank research on regional banking — Across multiple Fed districts, you’ll find research on community-bank economics, deposit competition, credit cycles, and the growing operational burden of regulation and compliance.

-

American Banker — Ongoing industry reporting that’s especially useful for understanding competitive dynamics, regulatory shifts, and how banks like FNB are positioning against peers and fintechs.

-

OCC history resources — Helpful context on the National Banking Act era, why national charters mattered, and how regulation evolved into the modern U.S. banking system.

-

Vincent Delie interviews and speeches — Bank Director, American Banker, and regional outlets capture the leadership perspective behind the playbook: discipline, integration, and how FNB thinks about scale.

-

Celent and Fintech Futures research — For the technology angle: digital banking trends, customer behavior shifts, and the tooling that’s reshaping distribution and operating models.

-

Pittsburgh Business Times — Local reporting that fills in key texture: FNB’s headquarters decisions, local market moves, and the company’s role in Pittsburgh’s business ecosystem.

-

Federal Reserve reports on regional banking competitiveness — A more academic and policy-driven view of how competition works in deposits and lending, and what that implies for regional banks’ long-term economics.

Key Takeaways

-

FNB is a process power story. It didn’t win with a magical moat or a breakthrough product. It won by doing hard, repeatable things—underwriting, integration, efficiency—better than most, for a long time.

-

The consolidation bet paid off. FNB leaned into the industry’s gravity: scale mattered more every year, and buying smaller banks in the right markets created real operating leverage.

-

2013–2020 was the transformation era. This is when FNB stopped being “a Pennsylvania bank that’s expanding” and became a true multi-state regional franchise.

-

The Yadkin deal was the inflection point. It proved FNB could execute a large, complex merger and build a meaningful platform in the Carolinas—without breaking the machine.

-

The challenge ahead is sustainability. The question isn’t whether FNB can operate well. It’s whether operating excellence, by itself, can stay decisive against fintech unbundling and megabank scale.

This is a story about finding the lane that fits, then running the same play—disciplined, deliberate, and repeatable—until it compounds into something much bigger than anyone expected. In an industry that often rewards flash, FNB has made a case for the quiet power of boring. At least so far.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music