First Financial Bancorp: From Civil War Charter to Regional Banking Powerhouse

Introduction: The 160-Year Journey of a Midwest Banking Institution

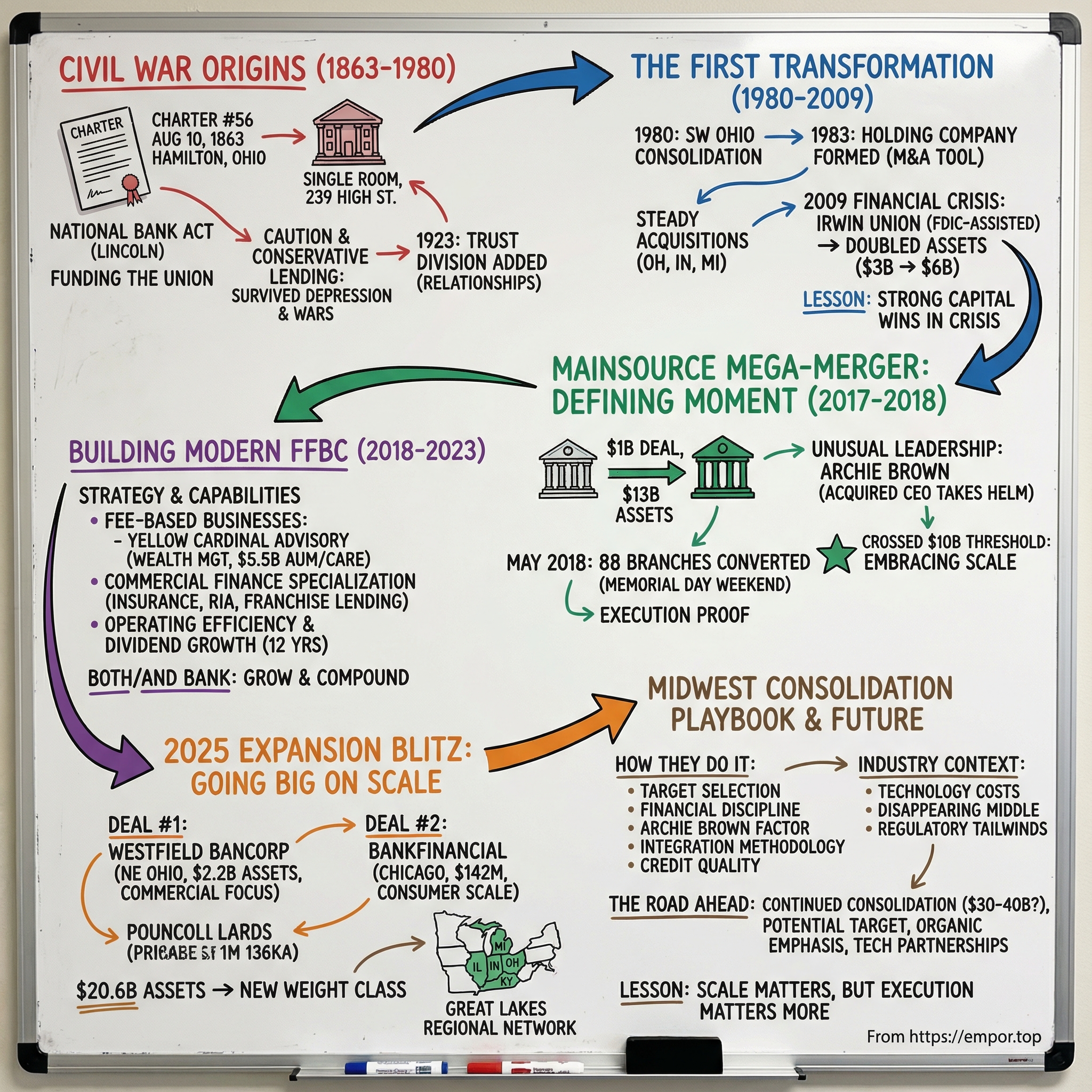

In the basement archives of Hamilton, Ohio, there’s a piece of paper that says more about American finance than its yellowed edges would suggest: Charter Number 56, issued on August 10, 1863, by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

That charter created the First National Bank of Hamilton under the brand-new National Bank Act—right in the middle of the Civil War, as Abraham Lincoln’s government tried to build a banking system sturdy enough to help finance a country coming apart. It was the sixth-oldest national bank charter ever issued. And it started, fittingly, small: a single room at 239 High Street in Hamilton.

Fast-forward 160 years and the same institution—now First Financial Bancorp, based in Cincinnati—had grown to $18.6 billion in assets as of December 31, 2024.

So the question isn’t “How old is this bank?” The question is: how did a small-town Ohio bank, founded during the Civil War, make it through every era of American banking—and then, late in its life, turn itself into a modern regional powerhouse?

First Financial now has 131 locations across Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and Illinois. But the real story isn’t the branch count or the trivia of an early charter. It’s what happened recently. Over roughly the past seven years, this bank stopped acting like a steady local operator and started acting like a consolidator—pulling off a billion-dollar merger that reset its ambition, then following it with a 2025 acquisition blitz that pushed it beyond the $20 billion scale threshold.

This is a story about the disappearing middle in American banking—where the economics increasingly force institutions to consolidate or be consolidated. And at the center of it is an unlikely protagonist: Archie Brown, a CEO who once sold his own bank to First Financial, then stepped in to run the combined company—and executed the playbook from the inside.

The Civil War Origins: When Banking Meant Building a Nation (1863-1980)

Picture Hamilton, Ohio, in the summer of 1863. The Civil War is still raging, and in Washington, Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase has just pushed through the National Bank Act—an ambitious attempt to bring order to American finance. The law created federally chartered banks, a uniform national currency, and a built-in funding mechanism for the Union: these new banks were required to buy U.S. bonds to back the money they issued.

That’s the environment First National Bank of Hamilton was born into.

According to historical information First Financial provided to a newspaper, the bank opened on August 15, 1863, in a single room at 239 High Street. Hamilton wasn’t a sleepy river town. It was an industrial place—positioned on the Great Miami River, with textile mills and paper manufacturing in its orbit. Beckett Mill on Dayton Street was operating at the time; it later became Mohawk Fine Papers and ultimately closed in 2012. Other 1860s-era industry included Schuler and Benninghofen, a woolen mill producing blankets and felt used by the paper trade. In other words, this was a town that made things—and needed a bank that could finance payrolls, inventory, equipment, and growth.

From early on, First National developed a reputation for something less flashy but far more durable: caution. Conservative lending. Strong capital. A bias toward surviving the bad years over maximizing the good ones. Vaden Fitton, a former senior officer, first vice president, and bank director, later summed it up plainly: the bank was “always very sensitive about its capital position” and “perhaps more conservative in its lending process than its competition.” That mindset mattered. It’s how a bank founded during the Civil War could still be standing after the Great Depression—and again after the Great Recession.

Then, in 1923, came a decision that quietly widened the bank’s identity. The name changed to First National Bank and Trust Company of Hamilton with the creation of a trust division. It wasn’t just a rebrand. It was an early bet that banking could be more than deposits and loans—that advising families, managing wealth, and building multigenerational relationships could become part of the institution’s core.

For the next several decades, the bank did what community banks did at their best: it stayed local, served local customers, and built trust the slow way—one relationship at a time. The Depression. Multiple wars. The inflation and turmoil of the 1970s. First National moved through all of it anchored in Butler County, accumulating something you can’t buy quickly: a stable credit culture and a reputation for safety.

And that’s the point of this first chapter. First Financial didn’t spend its first century chasing scale. It spent it earning the right to pursue it later.

The First Transformation: From Local to Regional (1980-2009)

By 1980, First National Bank of Hamilton had spent more than a century proving it could survive. Now it was ready to grow.

That year, it consolidated operations with the First National Bank of Middletown to form the First National Bank of Southwestern Ohio. It sounds like a simple combination, but it marked a shift in mindset: this was the moment the institution stopped being just a Butler County bank and started behaving like a regional one. From there, it began picking up smaller institutions, using those acquisitions to push beyond its home turf.

The bigger structural move came in 1983, when First Financial Bancorp was formed as a holding company.

That detail matters, because a holding company is how a bank gets serious about M&A. It creates a parent entity that can raise capital, issue stock, take on debt, and do deals—while keeping the core bank operations insulated from the mechanics and complexity of transactions. At the time, First Financial’s footprint had grown to $2.6 billion in assets, with 15 affiliates operating 106 banking centers across Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan.

The playbook in this era was steady and methodical: small community banks, usually in adjacent markets, one at a time. First Financial expanded across northwestern, eastern, and southern Indiana through 11 acquisitions starting in the 1980s. No single deal was meant to redefine the company. Together, they did.

Then the calendar flipped to September 2009, and the environment changed from “expand carefully” to “survive, or strike.”

The financial crisis created openings that only well-capitalized banks could take. On September 18, 2009, while much of the industry was pulling back, First Financial made its biggest move yet. It announced that its wholly owned subsidiary, First Financial Bank, N.A., had purchased the banking operations of Irwin Union Bank and Trust Company and Irwin Union Bank, F.S.B.—subsidiaries of Irwin Financial Corporation—through agreements with the FDIC.

This was an FDIC-assisted acquisition, the regulator’s way of moving deposits and branches to a healthy institution quickly, without letting a failed bank’s problems ripple outward. Under the deal, deposits were assumed at a premium of less than 1%. The loan portfolio was purchased under modified terms: non-performing assets, other real estate owned, acquisition, development and construction loans, and residential and commercial land loans were excluded. Performing loans were purchased at an approximate 25% discount and backed by FDIC loss-share agreements, with a threshold of $636 million. Roughly $2.5 billion in assets were covered. Generally, losses up to that threshold were covered at 80% by the FDIC, and beyond it at 95%.

The impact was immediate. Those purchases helped double First Financial’s assets—from about $3 billion in 2008 to more than $6 billion by 2010.

But the Irwin deal wasn’t just about getting bigger. It was about proving capability. First Financial had shown it could work with regulators, absorb a distressed institution, and come out stronger. The 2009 purchase also gave it three outposts in suburban Indianapolis. Two years later, it bought 22 Indiana branches from Flagstar Bank.

The crisis taught First Financial a lesson it would keep using: when others retreat, the banks with strong capital and disciplined underwriting get to move forward.

The MainSource Mega-Merger: A Defining Moment (2017-2018)

By 2017, First Financial had grown to roughly $8.9 billion in assets—respectable, but increasingly exposed. It was no longer a true small-town community bank, but it still wasn’t big enough to go toe-to-toe with regional heavyweights like Fifth Third and Huntington across technology, product breadth, and efficiency. That “in-between” is where banks get squeezed. And First Financial could see the squeeze coming.

On July 25, 2017, it made its move. First Financial agreed to buy Greensburg, Indiana-based MainSource Bank in a $1 billion deal—one that would make it the fourth-largest bank in Cincinnati, and the second-largest locally based bank.

This wasn’t a tidy little bolt-on. It was a defining bet: a merger designed to create what the companies called a new, preeminent community bank across Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky. Two high-performing Midwest franchises coming together to build a roughly $13 billion institution with real scale in commercial and retail banking, wealth management, and specialty finance.

The mechanics were straightforward. The companies structured it as a stock-for-stock transaction, with MainSource Bank merging into First Financial Bank. MainSource shareholders would receive 1.3875 shares of First Financial stock for each MainSource share.

But the real twist wasn’t in the exchange ratio—it was in who would run the combined company.

Both banks said their CEOs would play “critical” roles in the transition. Claude Davis, First Financial’s CEO, would move into executive chairman for three years. And Archie Brown—MainSource’s chairman, president, and CEO—would become president and chief executive officer of the combined bank. Then, Davis would shift again to non-executive chairman in 2021.

That is not how most bank deals work. In the usual script, the buyer’s team takes the controls and the seller’s executives exit over time. Here, the acquired CEO took the top job. It was a signal that this transaction was as much a partnership as it was an acquisition—and that First Financial believed Archie Brown was the operator to lead the next chapter.

There were hurdles, of course. To satisfy the Department of Justice, MainSource had to divest one branch in Greensburg and four in Columbus, Indiana. Those branches were sold to German American Bancorp.

The deal closed on April 2, 2018. And then came the part that separates banks that do deals from banks that can integrate them.

On May 29, 2018, MainSource’s systems and deposits were transitioned to First Financial. Eighty-eight branches converted over a single Memorial Day weekend. That’s the unglamorous, high-stakes heart of bank M&A: get the systems conversion wrong and customers leave, accounts break, and the economics unravel. First Financial got it done.

On the other side, the combined company—operating as First Financial Bancorp with its banking subsidiary, First Financial Bank—came out at roughly $14 billion in assets.

And that’s why MainSource was transformational. It wasn’t just bigger. It pushed First Financial decisively beyond the psychologically—and regulatorily—important $10 billion threshold. Many banks hesitate near that line because scale brings new complexity, including enhanced Dodd-Frank requirements and the Durbin Amendment’s interchange fee restrictions. First Financial didn’t tiptoe over it. It cleared it in one jump, choosing to embrace scale and build a platform for what would come next.

Building the Modern FFBC: Strategy and Capabilities (2018-2023)

When Archie Brown took the helm of the combined company in April 2018, he inherited something more valuable than a bigger balance sheet: a platform built to keep compounding.

Brown didn’t arrive as a typical “new CEO after the merger.” He had been president and chief executive officer of MainSource Financial from 2008 to 2018, and its board chair from 2011 to 2018. Across nearly 41 years in banking, he’d worked in branch and regional management, deposit and loan operations, business development, small business, and consumer lending. In other words, he wasn’t just a deal guy—he understood how the bank actually runs.

That background gave him a rare advantage: he knew both sides of M&A. He had sold MainSource to First Financial, then turned around and began using First Financial to buy others. He understood what sellers want, what integrations demand, and what regulators are really looking for. That’s the kind of experience you can’t fake—and it shaped the next chapter.

There’s also a personal through-line to Brown that shows up in the culture First Financial tries to build. As a teenager, he knew two things earlier than most: he wanted to be a banker, and he’d met the person he wanted to marry.

In the early 1970s, two middle-class kids from Colerain Township met in a church youth group. They married in 1980 while in college—Archie Brown was 19; his bride, Sharen, had just turned 21—and then completed their degrees at the University of Georgia. He earned a bachelor’s degree in business administration from the University of Georgia and later an MBA from Xavier University.

Those faith-driven values show up in how First Financial talks about employees and communities. The company has earned recognition as a Gallup Exceptional Workplace Award winner and has received consecutive Outstanding ratings from the Federal Reserve for Community Reinvestment Act performance.

But culture is only half the story. The other half is the operating model Brown and the team built after MainSource—one designed to be more than “just” a spread-based bank. The strategy centered on a few capabilities that make a consolidator work.

Fee-based businesses came first, especially wealth. First Financial rolled out a new name for its Wealth Management division—Yellow Cardinal Advisory Group—positioning it around “deep expertise,” a “unique blend of sophisticated solutions,” and client individuality. The debut also included expanded capabilities in business succession planning and fixed income investments. As the bank put it: “Just as a yellow cardinal is unique in nature, the Yellow Cardinal brand expresses our aim to help clients live a one in a million life.”

Under the hood, this wasn’t branding for branding’s sake. Yellow Cardinal already had a meaningful base: $3.3 billion under management and care, plus another $1.7 billion in its retail brokerage platform. By mid-2025, the company said wealth services—provided through Yellow Cardinal—spanned wealth planning, portfolio management, trust and estate planning, brokerage services, investment banking, and retirement plan services, with about $5.5 billion in assets under management or care as of June 30, 2025.

Alongside wealth, First Financial leaned into commercial finance specialization. The company offers secured commercial financing services to the insurance industry, registered investment advisors, certified public accountants, indirect auto finance companies, and restaurant franchisees. These verticals can produce higher-margin revenue, but just as importantly, they embed the bank deeper into how clients operate—relationships that are harder to displace than a rate quote.

Then there was the unsexy but essential part: operating efficiency. First Financial pursued ongoing workforce efficiency initiatives even as it grew. That focus reflects a basic truth about banking economics: in a business where margins can get thin fast, cost discipline isn’t optional—it’s a strategy.

And through all of it, the company kept one promise that matters to a lot of bank investors: dividends. First Financial Bancorp extended a long record of dividend growth—12 consecutive years—including a 4.2% increase in the quarterly dividend to $0.25 per share in July 2025. Management framed those payouts as a signal of stability, supported by robust earnings and a payout ratio of about 38.80%.

Put together, the message was straightforward. First Financial wanted to be a “both/and” bank: grow through acquisitions and still pay shareholders like a steady compounder. That’s a difficult needle to thread in regional banking. But after MainSource, First Financial wasn’t trying to be typical anymore.

The 2025 Expansion Blitz: Going Big on Scale

If 2017 and 2018 were the inflection point, 2025 was the acceleration. In a matter of months, First Financial announced two deals that didn’t just add branches—they pushed the company past the $20 billion line and stretched its map in a deliberate way.

Deal #1 was Northeast Ohio.

In June 2025, First Financial agreed to acquire Westfield Bancorp, the holding company of Westfield Bank, FSB. Westfield came with $2.2 billion in assets and, more importantly, a presence in the “geographically attractive” communities of Northeast Ohio—territory First Financial had been working its way into.

The price tag was $325 million, paid 80% in cash and 20% in First Financial stock. The seller was Westfield’s sole shareholder, Ohio Farmers. In practical terms, the consideration was $260 million in cash plus about 2.75 million shares—roughly $65 million based on a 10-day volume weighted average price as of June 20, 2025.

For a bank that wants to do repeatable M&A, the math has to work. First Financial said this one would be 12% accretive to earnings, with a tangible book value earn-back of about 2.9 years—an especially attractive payback period by industry standards, and a signal the company believed it was buying value, not just buying size.

After the deal closed, First Financial announced it now had $20.6 billion in assets—officially moving it into a new weight class, with what it described as a strong Midwest foundation and a broader set of retail and business capabilities. CEO Archie Brown highlighted a key theme in the Westfield transaction: this wasn’t simply about adding deposits. He pointed to Westfield’s commercial banking and specialty lending businesses as assets that would “build upon our existing strengths.”

Then, before the ink was dry, came Deal #2.

In August 2025, First Financial and BankFinancial jointly announced an agreement for First Financial to acquire Chicago-based BankFinancial in an all-stock transaction valued at approximately $142 million as of the date of the merger agreement. BankFinancial brought a “strong core deposit franchise” and 18 financial centers—giving First Financial something it didn’t fully have in Chicago yet: consumer banking and lending scale to match its existing commercial presence.

Brown framed it as an expansion of the menu in a market where First Financial already had a foothold. “We are excited to add consumer banking and lending solutions to the existing lineup of commercial services offered to Chicago businesses,” he said, adding that BankFinancial’s retail footprint would give Chicago clients access to a broader range of banking and specialty solutions.

By December 2025, First Financial had received regulatory approval from the Federal Reserve and the Ohio Department of Financial Institutions to complete the BankFinancial acquisition. Closing was anticipated on or around January 1, 2026, subject to customary closing conditions and approval by BankFinancial shareholders.

Zoom out, and you can see the shape of the strategy.

First Financial wasn’t just collecting assets; it was connecting markets. In 2023, it added a commercial lending presence in Northeast Ohio. In 2025, it doubled down on Chicago through the BankFinancial agreement. And it also planted a flag in Michigan, adding a commercial banking presence in Grand Rapids.

That Michigan move came with a very specific play: put a local leader on the ground. First Financial introduced Grand Rapids native Chris Turner as commercial market president and opened a commercial banking office in Grand Rapids. Turner was tasked with leading the local team and building commercial and industrial client relationships. As the bank put it, Turner’s market knowledge and connections—combined with First Financial’s broader commercial banking capabilities—positioned it to build relationships and grow from there.

Put it all together and the pattern is hard to miss. First Financial was building a Great Lakes regional network—Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, Illinois, and now Michigan—linking industrial heartland markets where relationship-driven commercial banking still matters, and where scale increasingly decides who gets to keep playing.

The Midwest Consolidation Playbook: How They Do It

First Financial’s M&A strategy isn’t flashy. That’s the point. It’s a repeatable, relationship-driven playbook—one designed to avoid the classic regional bank trap of buying growth at any price and then spending years cleaning it up. If you want to judge whether FFBC can keep compounding from here, you start by understanding how it picks targets, prices deals, and integrates what it buys.

Target Selection Criteria: - Community banks with strong credit cultures—what one investor letter described as a “plain vanilla loan portfolio with solid credit culture.” - Geographic adjacency: expanding into nearby markets, not running off into distant experiments. - Franchises that complement the platform rather than just pile on overlap. - Sellers motivated by strategy, not desperation.

Financial Discipline: FFBC sits in that mid-cap regional category, with a market cap around $2.2 billion. And that’s where discipline becomes non-negotiable—because a bank this size can’t count on a perpetually “expensive” stock to fund acquisitions. It has to buy well.

That’s a big part of why valuation keeps coming up in how investors talk about First Financial. Gator Capital Management, for example, framed FFBC as a well-run, better-than-average commercial bank that trades too cheaply—pointing to a valuation of about 7.41x 2026 P/E versus what it described as a 10–14x normal range and peer averages. They also cited strong returns (1.40% ROA and 19.11% ROTCE), steady credit outcomes, and a pattern of strategic expansion—into Cleveland and Chicago in particular—through low-priced acquisitions that become platforms for organic growth.

The takeaway isn’t the multiple. It’s the constraint: if the stock is discounted, management can’t “financial-engineer” its way into growth. Every deal has to stand on its own economics.

The Archie Brown Factor: It’s hard to overstate how unusual it is for the acquired CEO to become the buyer’s CEO—and then turn the combined company into an acquirer. Brown has led First Financial since April 2018, after serving as president, CEO, and board chair of MainSource Financial Group, where he oversaw significant growth.

That history gives him an edge that doesn’t show up on a term sheet. When Brown calls a potential seller, he isn’t pitching from a script. He can credibly say: I’ve been in your seat. I’ve sold my bank. I’ve lived what happens next—for shareholders, employees, and the community. In an industry that still runs on trust and reputation, that kind of lived experience can be a real advantage in getting deals done.

Integration Methodology: MainSource became the template. The banks legally became one company when the deal closed in early April 2018, but operationally it stayed “business as usual” until the planned transition weekend later in the second quarter—when MainSource’s systems converted and branches rebranded under First Financial.

That’s the hard part of bank M&A: not the signing, not the closing, but the conversion. Moving customer accounts, cards, online banking, back-office systems, and branch routines without breaking the customer experience is where integrations succeed or fail. First Financial converted 88 branches over a single weekend. It took months of preparation—and the fact that it happened without major disruption became a proof point the organization can point back to as it takes on Westfield and BankFinancial.

Credit Quality Through Growth: The other non-negotiable is credit. First Financial has managed to grow without loosening underwriting just to put up bigger numbers. Net charge-offs of 10–33 basis points over the past decade suggest the bank didn’t trade discipline for expansion—and in banking, that’s often the difference between a consolidator and a cautionary tale.

The Industry Context: Why Regional Banks Must Consolidate

First Financial’s strategy only really clicks when you zoom out. The whole regional banking industry is in the middle of a structural shift, and the forces pushing banks together aren’t subtle—they’re compounding.

The first force is technology, and it’s turning into a tax on being mid-sized.

Over the past 15 years, banks increased technology spending by about 65%, and budgets are expected to keep growing at roughly 10% a year for the next five years. By 2023, the biggest banks were spending more than 10 times what regional banks could afford—and that gap is still widening.

That creates a brutal reality for a $20 billion bank. JPMorgan can spend more on tech in a single quarter than First Financial generates in annual revenue. If you’re a regional, you can’t “outspend” that. You can only out-focus it—or scale enough that the fixed costs stop being suffocating.

As one industry report put it, tech upgrades are a major investment for every bank, but they hit community and smaller banks harder because they have fewer assets over which to spread the cost. And because smaller banks tend to have higher fixed costs in general, they’re left with less room to fund the next wave of technology investment.

Then there’s the second force: the middle of the industry is disappearing.

Banking is bifurcating into two models that make sense. On one end are the national giants with massive budgets, broad product suites, and near-infinite patience for multi-year platform investments. On the other end are truly local community banks—small enough that relationships, speed, and local knowledge are the advantage. The banks in between are the ones with the hardest job: too big to be “just local,” too small to match the big players on digital experience, data, and product breadth.

In that world, consolidation isn’t a tactic. It’s how you avoid getting squeezed.

And the timing matters, because the M&A environment warmed up fast in 2025.

After a sluggish 2022–2023, mergers picked back up, and the momentum was expected to carry into 2026. By 2025, more than 150 bank deals had already been announced—more than all of 2024. In October 2025 alone, 21 bank deals were announced totaling $21.4 billion, the highest monthly deal value since early 2019.

Regulation played a role in that rebound, too. Federal agencies began clearing deals faster and with fewer roadblocks, especially for mid-sized transactions. That shift was punctuated by the rescission of the 2024 merger review guidelines and the return of expedited review and streamlined business combination applications. The result: recent mergers were approved in less than half the time similar deals took under the prior regime. The FDIC, OCC, and, to some extent, the Federal Reserve appeared more willing to green-light footprint- and capability-expanding mergers—so long as the obvious red flags, like severe CRA issues or antitrust problems, weren’t present.

Put those pieces together and you get the fourth force: a super-regional arms race.

Regional lenders were pursuing mergers to diversify revenue, strengthen balance sheets, and expand in faster-growing markets—because competing with the biggest banks increasingly requires scale in deposits, technology, and data. When two regionals merge, they’re not just adding branches. They’re combining their ability to fund modern digital banking, analytics, and product development—and trying to buy themselves a seat at the table for the next decade.

First Financial operates in the shadow of that reality. Fifth Third and Huntington aren’t just nearby competitors; they’re vastly larger institutions playing the same game with far more resources. So the question hanging over FFBC isn’t whether consolidation is happening. It’s whether First Financial can get big enough, fast enough, to stay a consolidator—or whether, one day, it becomes somebody else’s deal.

Competitive Dynamics and Market Position

To understand where First Financial fits, you have to stop thinking of “the Midwest banking market” as one battlefield. It’s more like a set of overlapping arenas—consumer branches, small business, middle-market commercial, and specialty finance—and the competitors change depending on where you’re standing.

The big names loom over everything:

The Midwest Competitive Set: - Fifth Third Bancorp: Fifth Third runs about 1,300 branches across the Midwest and Southwest. With its Comerica acquisition, it becomes the ninth-largest U.S. bank at roughly $288 billion in assets. Put differently, First Financial is only about 7% the size of post-merger Fifth Third. - Huntington Bancshares: Huntington has nearly 1,000 branches across the Midwest. Its Cadence deal, valued at $39.77 per share, is expected to create a top-ten bank with about $276 billion in assets and $220 billion in deposits. - KeyCorp: Cleveland-based, with a heavier tilt toward commercial banking. - Regional community banks: Dozens of smaller institutions—some fierce competitors today, and, in the consolidator worldview, potential partners tomorrow.

That’s the core tension for First Financial. Against the super-regionals, it can’t win a pure scale race. But it also isn’t a tiny community bank that can survive entirely on hometown relationships and local decision-making.

The Strategic Positioning: First Financial sits in a narrow but attractive middle lane: far smaller than Fifth Third and Huntington, yet large enough to deliver the kind of products and infrastructure many community banks can’t—treasury management, wealth services, specialty lending—without giving up the relationship-driven model that customers still value.

The strategy, in plain English, is “national-bank-like capabilities with community-bank relationships.”

As the Federal Reserve frames it, regional banks generally run from $10 billion to $100 billion in assets, operate across several states, and focus on consumer, small business, and commercial lending within defined territories—big enough to support technology and compliance spend, but still grounded in local markets. Super-regionals are typically above $100 billion in assets and compete more like national banks in select product lines, with broader footprints and deeper digital investment.

First Financial is at the upper end of the regional category—trying to offer more sophistication than its size would suggest, without drifting into the impersonal sprawl that often comes with being much bigger.

Differentiation Through Specialty: Where First Financial really tries to separate itself is vertical expertise—business lines that deepen relationships and, in many cases, carry better economics than “plain vanilla” commercial banking.

In Michigan, for example, First Financial said it would bring businesses a wide suite of sophisticated capabilities: commercial credit and services, asset-based lending, ESOP, sponsor and family office banking, syndications, treasury management, trade finance, M&A advisory, risk management, and employee financial wellness programs.

And those offerings aren’t theoretical. The company points to specialty banking lines including Bannockburn Capital Markets; equipment finance and leasing through Summit Funding Group; specialty financing lending through Oak Street Funding; commercial insurance premium financing through Agile Premium Finance; and wealth management—both institutional and personal—through Yellow Cardinal Advisory Group.

These are the kinds of niches—insurance premium finance, equipment leasing, RIA lending—where expertise matters, relationships get sticky, and price competition tends to be less of a race to the bottom. For a bank like First Financial, that’s not just differentiation. It’s how you compete with larger players without pretending you can outspend them.

Business Model Deep Dive and Economics

First Financial’s business model is built to do two things at once: generate steady spread income like any traditional bank, and layer on fee businesses that make the earnings stream more durable.

Revenue comes in two big buckets. The first is net interest income—the spread between what the bank earns on loans and what it pays on deposits. The second is non-interest income: fees from wealth management, commercial finance, treasury services, and other products that don’t depend on the rate cycle.

As of September 30, 2025, First Financial reported $18.6 billion in assets, $11.7 billion in loans, $14.4 billion in deposits, and $2.6 billion in shareholders’ equity. Its main banking subsidiary, First Financial Bank—founded back in 1863—runs six lines of business: Commercial, Retail Banking, Investment Commercial Real Estate, Mortgage Banking, Commercial Finance, and Wealth Management.

That mix matters, because it helps explain how FFBC can be both a consolidator and a consistent earner.

On profitability, the headline numbers have been a big part of the pitch. With a 1.40% return on assets and a 20%+ return on tangible common equity, First Financial has been producing returns that compare well against high-performing Midwestern peers. A 1.40% ROA is strong for a community and regional bank—where 1.0% to 1.2% is often closer to “normal.” And a 20%+ ROTCE signals something even more important for an acquirer: the bank is turning its capital base into meaningful earnings, which is the fuel for growth.

Then there’s valuation—where the story gets more complicated.

Investor commentary has emphasized a familiar banking pattern: own banks with above-average returns, strong credit culture, and management focused on growing tangible book value per share, but buy them at a discount—often around 8x next year’s earnings rather than the 10–14x range those same businesses can trade at in better sentiment.

In the market, FFBC shares opened at $25.80 on Monday. Analyst sentiment has been mixed: five analysts have issued hold ratings and three have rated the stock a buy. The average 12-month price target among brokerages covering the company over the last year is $29.50. Truist raised its price target from $28.00 to $29.00 and maintained a “hold” rating in a research note dated Friday, October 3rd.

That discount cuts both ways. It’s a risk because a cheaper stock is weaker M&A currency. But it’s also an opportunity: if the market starts pricing First Financial more like a premium operator rather than a generic regional bank, there’s room for the multiple to rise.

And finally, the dividend—the “don’t forget we’re still a bank stock” part of the equation.

First Financial disclosed a quarterly dividend that was paid on Monday, December 15th. Shareholders of record on Monday, December 1st received $0.25 per share, with an ex-dividend date of Monday, December 1st. Annualized, that’s $1.00 per share, or about a 3.9% yield. The company’s dividend payout ratio was listed at 37.04%.

That payout level is conservative by design. It means the bank is still keeping the majority of its earnings inside the business—supporting growth, capital strength, and, crucially, the ability to keep doing deals—while paying investors a meaningful cash return along the way.

Porter's Five Forces and Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

To make sense of First Financial’s position—and its odds of continuing to compound from here—it helps to look at the company through two lenses: the classic competitive framework everyone learns, and the newer “powers” framework that gets at what advantages can actually endure.

Porter's Five Forces:

1. Threat of New Entrants (LOW):

Starting a brand-new bank from scratch has become almost prohibitively difficult since the 2008 financial crisis. Between regulatory hurdles, capital requirements, and the simple fact that building a real deposit base takes years, de novo competition just doesn’t show up the way it used to. In that environment, First Financial’s 1863 charter isn’t just a fun historical footnote—it represents more than a century and a half of accumulated legitimacy, relationships, and operating infrastructure.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers (LOW-MEDIUM):

In banking, “suppliers” are mostly depositors and the vendors that power the modern stack. Deposits are competitive—customers can shop rates quickly—but scale still helps, and First Financial’s footprint gives it real funding advantages versus smaller players. On the other side, technology vendors have been gaining leverage as digital capabilities become table stakes. That pressure isn’t unique to First Financial, but it does raise the cost of staying relevant.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers (MEDIUM-HIGH):

Commercial clients, especially, have plenty of choices. They can move relationships to Fifth Third, Huntington, or any number of regional and local competitors. What reduces that leverage is complexity. Once a business is running payroll, treasury management, multiple credit lines, and specialized services through one bank, switching becomes painful. First Financial’s specialty lending verticals add another layer of stickiness—when you’re embedded in how a customer operates, you’re harder to replace with a rate quote.

4. Threat of Substitutes (MEDIUM):

Fintech is a real substitute threat, but it’s usually product-by-product rather than relationship-by-relationship. Payments players like Square and Stripe, lenders like Upstart and SoFi, and digital wealth platforms like Betterment and Wealthfront can siphon off specific revenue pools. What’s still defensible is the bundled relationship: commercial credit paired with deposits, treasury management, and wealth services. Yellow Cardinal does face the broader trend of robo-advisors, but it’s also positioned for clients who want more than automated allocation.

5. Competitive Rivalry (HIGH):

This is the hard truth of every market First Financial operates in: rivalry is intense. National banks, super-regionals, other regionals, and credit unions all compete for the same deposits and loans. Consolidation only turns up the heat, because the banks that remain standing tend to be larger, better funded, and more capable.

Hamilton's Seven Powers:

1. Scale Economies (MODERATE-STRONG):

The biggest lever in modern banking is spreading fixed costs—technology and compliance, especially—over a larger base. Industry-wide, technology spending has risen dramatically over the past 15 years and is expected to keep climbing at a healthy clip. At $20B+ in assets, First Financial has real scale advantages versus sub-$10B banks. It’s still small next to super-regionals, but it has crossed into a tier where the economics start to work differently.

2. Network Effects (WEAK):

Traditional banking doesn’t have strong network effects. ATM networks help at the margins, but they don’t create the kind of compounding advantage you see in software or marketplaces. Digital network effects could emerge over time, but regional banking hasn’t really produced them yet.

3. Counter-Positioning (WEAK):

First Financial isn’t running a model that incumbents can’t copy. It’s not structurally protected by being “different.” Its advantage comes from doing the fundamentals well and executing consistently—not from a business design that blocks responses from larger competitors.

4. Switching Costs (MODERATE):

Switching costs are real in commercial banking: treasury setups, credit documentation, and the human relationships that get deals done. On the consumer side, switching has become easier as digital tools simplify moving accounts—so the stickiness is there, but not as strong as it once was.

5. Branding (MODERATE):

First Financial has meaningful regional brand recognition, especially in Ohio and Indiana, and its long history signals stability. Yellow Cardinal also gives the wealth business a distinct identity. But this is still a regional brand—not a national one—and that caps how much branding alone can do.

6. Cornered Resource (WEAK-MODERATE):

The sixth-oldest national bank charter carries some intangible advantage, but the more important “cornered resources” are practical: management expertise in Midwest commercial banking, a proven ability to execute M&A integration, and embedded relationships in key verticals like insurance premium finance and restaurant franchise lending.

7. Process Power (MODERATE-STRONG):

This is where First Financial stands out. The ability to repeatedly integrate banks—systems, people, culture—without breaking the customer experience is a real capability, and it’s hard to build quickly. Converting 88 MainSource branches in a single weekend took organizational muscle. The same goes for underwriting discipline: maintaining net charge-offs in a low range through multiple cycles suggests a process that’s embedded, not improvised.

Summary: First Financial’s real advantages cluster around Scale Economies and Process Power. That’s why the strategy leans so heavily toward consolidation: scale helps the economics, and process is what makes the deals survivable. But the implication cuts both ways—if FFBC is going to keep playing this game, it has to keep executing.

Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

1. Perfectly Positioned for Continued Midwest Consolidation: More than 150 bank deals were announced in 2025, regulators appeared to be moving faster again, and the industry’s cost pressures keep pushing smaller banks toward partners. That’s exactly the environment where First Financial’s strategy works. It has already shown it can find targets, get transactions done, and make them real after closing.

2. High Return Metrics: Gator’s investment in FFBC reflected a simple view: this is a bank putting up strong returns—around 1.40% ROA and 20%+ ROTCE—while using acquisitions to expand its footprint. If FFBC can sustain those returns as it scales, the compounding can be powerful.

3. Proven M&A Execution: MainSource is still the proof point. Converting 88 branches over a single weekend with minimal customer disruption is what “good at M&A” actually means in banking. That kind of operational competence lowers the risk of the next deal—because it suggests FFBC can do the hard part, not just the headline part.

4. Attractive Valuation: FFBC has traded around 7–8x next year’s earnings versus a cited “normal” range of roughly 10–14x. If the market starts rewarding the company like a high-quality consolidator—rather than pricing it like a generic regional—the upside doesn’t require heroics. It just requires recognition.

5. Management Alignment: Archie Brown isn’t an outsider parachuted in to chase growth. He sold his own bank to First Financial and then took over running the combined company. That lived experience matters: he understands what sellers worry about, what integrations demand, and what long-term stewardship looks like. It’s a real check against the classic “empire-building” incentives.

6. Interest Rate Tailwinds: A world of lower short-term rates and a steeper yield curve would generally be a friendlier setup for bank earnings. If the Federal Reserve cuts and the curve steepens as expected, the core spread business gets a tailwind.

7. Diversified Revenue: FFBC isn’t relying purely on net interest income. Specialty finance businesses like Oak Street Funding, Agile Premium Finance, and Summit Funding Group—plus Yellow Cardinal wealth management—add fee income and relationship depth that can make results more resilient across rate cycles.

Bear Case:

1. Integration Execution Risk: This is the flip side of doing deals. First Financial is working to integrate Westfield and BankFinancial at the same time, while also building out a new presence in Grand Rapids. Running multiple plays at once increases the odds of operational mistakes, cultural missteps, or customer attrition.

2. Technology Gap: By 2023, the largest banks’ technology budgets were more than 10 times those of regional banks. First Financial can’t match the digital investment of a JPMorgan. If customers come to expect “mega-bank” product experiences everywhere, the gap could widen and make it harder to compete.

3. Fintech Disruption: Fintech tends to attack banking one product at a time—payments, consumer lending, small business tools, wealth. Those competitors often have cleaner user experiences and lower cost structures, and they can pressure pricing in exactly the categories that used to be easy profit pools.

4. Geographic Concentration: FFBC’s footprint is still concentrated in the Midwest. That’s a strength for relationship banking, but it also creates cyclical exposure to regional industrial and manufacturing economies. If the Midwest hits a downturn, the impact won’t be diversified away.

5. Commercial Real Estate Exposure: Commercial real estate has been a pressure point across regional banking. The industry has watched what happens when CRE stress snowballs—New York Community Bancorp’s early-2024 downgrades and its subsequent capital raise are a reminder of how quickly sentiment can turn. First Financial isn’t immune to that broader risk.

6. Regulatory Headwinds: The bigger you get, the harder the game becomes. If First Financial keeps scaling through acquisitions, scrutiny rises. And once a bank pushes into much larger size tiers—around $50 billion—regulatory requirements like stress testing become substantially more demanding.

7. Competition from Larger Regionals: The consolidators aren’t just small and mid-sized banks. Huntington’s agreement to buy Cadence in a $7.4 billion all-stock deal is a reminder that super-regionals have far more firepower—more capital, bigger tech budgets, and more ability to absorb shocks.

8. Potential Acquisition Target: If First Financial keeps performing well while trading at a discount, it could become attractive to a larger acquirer. That might be fine—even great—for shareholders in the moment. But it would end the story of FFBC as an independent consolidator building the next platform.

Key Metrics to Watch

If you want to track whether First Financial’s “consolidator” story is actually working, you don’t need a spreadsheet full of ratios. You need a small dashboard—three signals that tell you whether the engine is compounding or quietly leaking.

1. Tangible Book Value Per Share Growth: This is the north star for many bank investors because it captures the real scoreboard: how much value the company is building for each share, after you strip out goodwill and other accounting noise. It reflects both earnings retention and whether acquisitions were bought and integrated well. First Financial has emphasized this metric, and the Westfield and BankFinancial transactions will show up here pretty quickly—either as clean compounding, or as a drag that takes longer to earn back.

2. Net Charge-Off Ratio: Credit quality is the one thing you can’t hand-wave. First Financial’s historical net charge-offs—generally in a low range—suggest real underwriting discipline. If that starts to deteriorate in a sustained way, it’s often the earliest warning that growth is being purchased with looser standards. Watch the quarterly net charge-off ratio and management’s commentary on where losses are showing up, especially in categories like commercial real estate.

3. Integration Success Metrics: Deals don’t create value at closing. They create value when customers stay, deposits stick, systems convert cleanly, and the promised efficiencies actually show up. So pay attention to customer retention, deposit retention, and cost synergy realization after Westfield and BankFinancial. Management will typically set expectations around synergies—this is where you hold them to it. Smooth branch and systems conversions, like the MainSource transition over Memorial Day weekend, are a good proxy for whether the organization can keep doing this at scale.

The Road Ahead and Future Scenarios

So what happens after you cross $20 billion, stitch together new markets, and prove you can run multiple integrations at once? For First Financial, the next chapter is still being written—but a few paths stand out.

Continued Consolidation (Most Likely):

The most natural next move is simply more of the same: keep buying well-run community banks in adjacent Midwest markets and keep building the Great Lakes footprint. If that playbook continues to work, it isn’t hard to imagine First Financial pushing toward the $30–$40 billion range over the next several years. Michigan already looks like the beginning of that next ring of expansion, and further moves into Illinois—or a step into nearby markets like Tennessee—would fit the pattern.

Acquisition Target (Possible):

There’s an irony baked into being a successful consolidator: the better you get at building a clean, scalable platform, the more interesting you become to bigger players. A super-regional like Fifth Third or Huntington—already operating at a very different scale—could view First Financial as a way to deepen presence in Ohio and Indiana. And FFBC’s appeal would be straightforward: a clean balance sheet, a strong credit culture, and a management team that has shown it can execute.

Organic Growth Emphasis (Possible):

Another plausible scenario is a deliberate pause. After Westfield and BankFinancial, First Financial could shift from “buy and integrate” to “optimize and deepen”—leaning harder into organic growth, digital investment, and continued efficiency work before the next wave of deals. In banking, sometimes the best acquisition is the one you don’t do until you’re ready.

Technology Partnerships:

First Financial can’t win a spending war against the mega-banks. So the more likely route is partnering—fintech relationships, targeted acquisitions, or vendor-led platform upgrades that let the bank upgrade its digital capabilities without trying to build everything from scratch.

Succession Planning:

Finally, there’s the question that comes for every long-tenured leader. Archie Brown has spent about four decades in banking, with experience spanning branch leadership, regional management, and bank operations. That depth has been a real advantage for First Financial’s transformation—but it also makes succession planning critical. The next era of FFBC will depend not just on what deals it does, but on who’s ready to lead when the current architect eventually steps aside.

Lessons and Takeaways

For Founders/CEOs:

Strategic patience pays off. First Financial didn’t try to brute-force its way to scale from day one. It spent generations building a foundation—capital strength, a conservative credit culture, and community trust—so that when the window for bold growth finally opened, it had the credibility and operational muscle to act.

For Investors:

In banking, scale matters. But execution matters more. Acquisitions only create value if the integration holds: customers stay, systems convert cleanly, and the promised economics actually show up. MainSource is the proof point that First Financial can do the hard part. The job now is to watch whether that same discipline carries through Westfield and BankFinancial.

For M&A Practitioners:

Integration is a capability, not a checklist. First Financial’s edge isn’t that it does deals—it’s that it can absorb them: convert systems, keep relationships intact, and turn “two banks” into one operating rhythm. In a consolidating industry, that kind of repeatable integration becomes its own competitive advantage—and it’s what ultimately flows into tangible book value and fuels the next transaction.

For Regional Banks:

The arithmetic is unforgiving: consolidate or be consolidated. Technology and compliance costs keep rising, and the industry keeps bifurcating. The likely end state is a smaller set of stronger super-regionals, plus a thinner layer of truly local banks. The ones who move earlier tend to have more options, better partners, and more control over their fate.

For Communities:

Scale and community don’t have to be mutually exclusive. First Financial has grown past $20 billion while still positioning itself as a relationship-driven Midwest bank. The real test comes next: can it keep that ethos as it stretches into new markets and keeps adding pieces? That question is still open—and it’s what will determine whether this becomes a great consolidation story, or just a big one.

December 2025 Update

As 2025 wound down, First Financial was right where its strategy was always meant to take it: bigger, more geographically connected, and on the verge of turning announcements into reality.

In December 2025, the company said it had received regulatory approval to complete its acquisition of Chicago-based BankFinancial. If it closed around January 1, 2026, as expected, it would put a clean capstone on the year’s expansion blitz: not just adding another bank, but filling in a key market where First Financial had been building a broader presence.

Meanwhile, the Westfield Bank integration kept moving forward, with a full conversion expected in early 2026. With Westfield folded in, First Financial stood at $20.6 billion in assets—now firmly in that next tier of regional banks, with a wider set of consumer and business offerings across its Midwest footprint.

Wall Street noticed, even if it didn’t fully re-rate the story yet. Shares of First Financial Bancorp (NASDAQ: FFBC) rose 2.8% in afternoon trading after Truist Securities raised its price target to $29 from $28. Truist kept its Hold rating, but the move reflected a simple change: BankFinancial was now real enough to model.

Truist also lifted its 2026 adjusted earnings per share forecast by 3% to $3.20, pointing to expected cost savings and purchase accounting adjustments from the merger. The note echoed a broader theme in how the market has come to talk about First Financial: steady execution, tangible book value per share growth, and the kind of shareholder-friendly capital decisions—like buybacks—that can quietly boost per-share economics over time.

Operationally, the company also kept reinforcing the culture it claims is part of the edge. In 2025, First Financial Bank received its second consecutive Outstanding rating from the Federal Reserve for Community Reinvestment Act performance. It was also recognized as a Gallup Exceptional Workplace Award winner—one of only 70 Gallup clients worldwide to receive the designation.

So the real question heading into 2026 wasn’t whether First Financial could do deals. It was what it would choose next: pause to digest Westfield and BankFinancial, or keep pressing while the lane stays open. The regulatory environment had turned more favorable, but it’s not guaranteed to last. There’s a political window through 2026–27 when approvals may remain easier—and if consolidation is part of the long-term plan, timing matters.

Either way, the arc is already remarkable. First Financial traveled from a single room on High Street in Civil War-era Hamilton to a $20+ billion regional bank spanning the Great Lakes economy.

The journey continues.

Further Reading and Resources

Primary Sources: 1. First Financial Bancorp annual reports and 10-K filings (2018–2025) — available at investor.bankatfirst.com 2. SEC filings, including 8-K acquisition announcements and quarterly 10-Q reports 3. First Financial investor presentations and earnings call transcripts

Industry Analysis: 4. Oliver Wyman: “Key Trends Driving US Bank Consolidation and Growth” (January 2025) 5. Deloitte: “Time is Right for a Wave of Bank Consolidation” 6. Fitch Ratings: U.S. community banks consolidation outlook

Investment Research: 7. Gator Capital Management Q3 2025 investor letter — FFBC investment thesis 8. Truist Securities, KBW, and Hovde Group research notes on FFBC

Historical Context: 9. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland: Archie Brown profile 10. Hamilton Journal-News archives: First Financial 150th anniversary coverage

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music