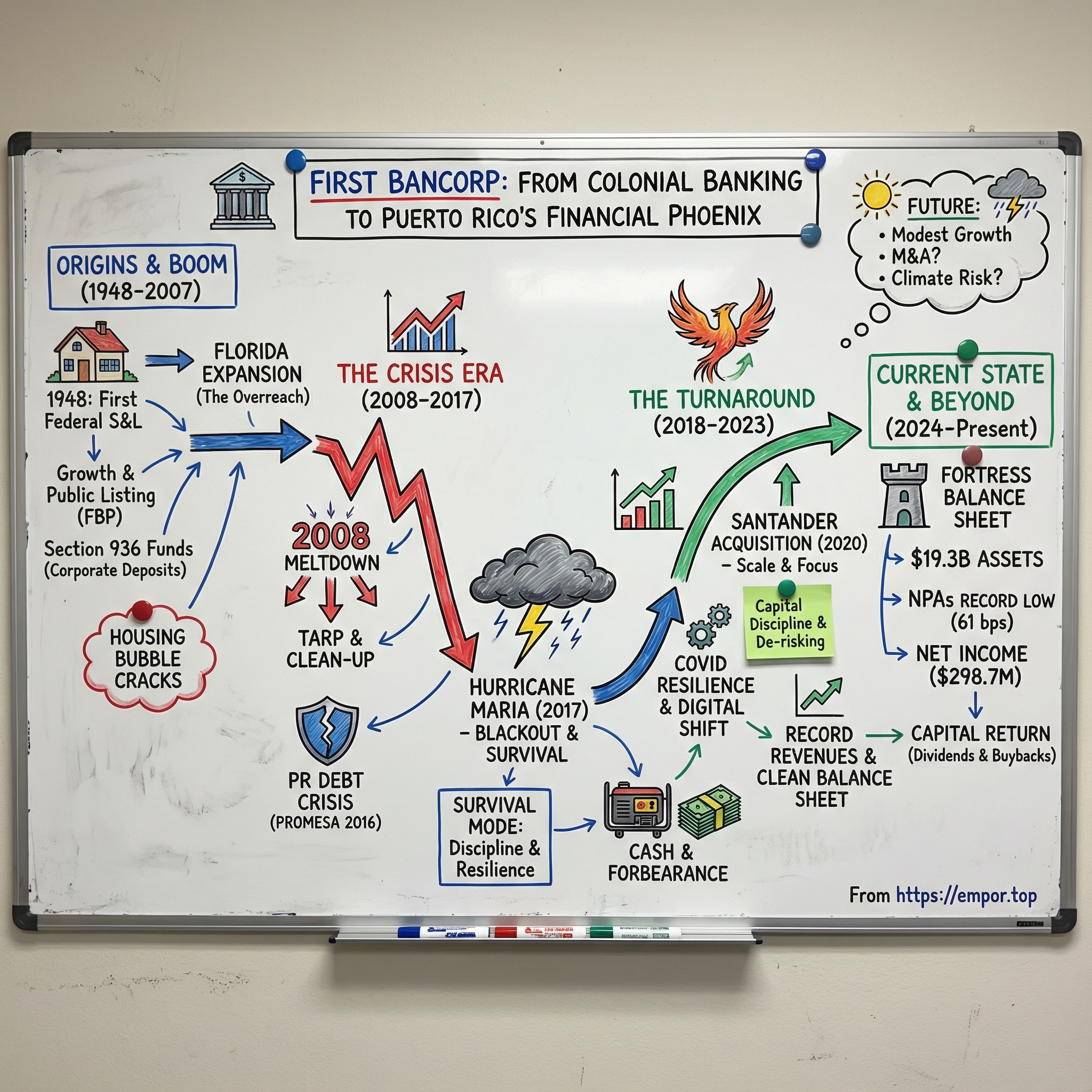

First BanCorp: From Colonial Banking to Puerto Rico's Financial Phoenix

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: September 2017. Hurricane Maria rips through Puerto Rico with 175-mile-per-hour winds. The entire island goes dark. No power. No cell service. ATMs don’t work. Three million American citizens are suddenly cut off from the basic plumbing of modern life.

Now imagine you’re running a bank inside that.

Branches are damaged or unreachable. Employees can’t get to work—many have lost homes themselves. Customers need cash immediately, but the systems that keep money moving are limping along on generators that will run out of diesel in days. Your loan book? You don’t even know who can pay next month. Your deposits? People are leaving the island, and nobody knows when they’ll come back.

That was the reality for First BanCorp, Puerto Rico’s second-largest financial institution, in the fall of 2017.

And here’s the twist: it didn’t just survive. It came out stronger.

Today, First BanCorp has about $19.3 billion in assets—an entirely different company than the one that spent the prior decade in survival mode. In Q4 2024, it reported net income of $75.7 million, or $0.46 per diluted share. For full-year 2024, net income totaled $298.7 million, or $1.81 per diluted share. Credit quality has followed the same arc: nonperforming assets fell to a record-low 61 basis points of total assets.

So how does a regional bank headquartered in a shrinking, bankrupt territory become one of the most compelling turnaround stories in American banking?

That’s the question at the heart of this deep dive.

Because this isn’t just a bank story. It’s a story about compounding catastrophes—and what it takes to stay standing when the ground keeps moving. A global financial crisis. A Puerto Rico debt spiral. A Category 5 hurricane. A pandemic. Each one would be a once-in-a-career event. First BanCorp got the whole set.

In the chapters ahead, we’ll follow First BanCorp from its beginnings as a tiny postwar savings institution in 1948, through the boom years and the overreach, into a near-death regulatory nightmare, and then through the slow, grinding work of rebuilding trust, capital, and discipline. We’ll dig into what makes Puerto Rico’s banking market so unusual, why mainland competition has mostly stayed away, and how the island’s banking landscape has effectively become a two-horse race between First BanCorp and Banco Popular. And we’ll close by laying out the bull case and the bear case for what comes next.

But first, we have to start where every Puerto Rico story starts: with the island itself.

II. The Island Context: Understanding Puerto Rico

To understand First BanCorp, you first have to understand Puerto Rico: a place that refuses to fit neatly into any box, and whose political status quietly rewires the rules of business.

Puerto Rico isn’t a state. It isn’t an independent country. It’s a commonwealth—an unincorporated U.S. territory the United States has controlled since the Spanish-American War in 1898. About 3.2 million people live there as U.S. citizens, in a system full of contradictions: they can vote in presidential primaries but not in the general election; they serve in the U.S. military but have no voting representation in Congress. The economy runs on the U.S. dollar and sits under U.S. federal jurisdiction—but for years, it didn’t have access to the same legal tools states use in a crisis, like bankruptcy protection. That gap wasn’t meaningfully addressed until PROMESA arrived in 2016.

This in-between status didn’t just shape politics. It shaped the entire economic model—and that shaped banking.

For decades, Puerto Rico’s modern economy revolved around tax incentives meant to lure mainland manufacturers. The big one was Section 936 of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code, enacted in 1976. It created a substantial tax credit for U.S. corporations operating in Puerto Rico and let subsidiaries on the island send earnings back to their parent companies without paying federal tax on that income.

The result was a manufacturing boom, especially in pharmaceuticals and medical devices. Puerto Rico grew into one of the world’s major biotech manufacturing hubs and a major exporter of medical devices, with dozens of plants across the island. Companies came for the tax structure—and for a while, that looked like an economic flywheel.

But the hidden twist is what those profits did once they were earned.

A large share of Section 936 profits weren’t reinvested into Puerto Rico’s productive economy. Instead, they sat as passive financial investments—more than $15 billion in passive holdings versus less than $5 billion invested in plants and equipment. A huge chunk of that money ended up inside the banking system as deposits and financial instruments.

Those “936 funds” created a very specific kind of banking ecosystem. In 1980, they made up about a third of all deposits in Puerto Rico’s commercial banks. By the mid-1980s, it was closer to two-fifths. Even as that share later declined, the effect lingered: finance grew larger and more central, but a lot of bank activity skewed toward securities trading and mortgages rather than broad-based local development.

So Puerto Rican banks got something powerful—an ocean of corporate deposits. And they also inherited something dangerous: dependence on a tax policy mainland politicians increasingly viewed as a corporate loophole.

By the early 1990s, Section 936 had become politically toxic. In 1996, President Clinton signed legislation to phase it out over ten years, with the provision fully repealed at the beginning of 2006.

That timing matters. The phase-out lined up almost perfectly with Puerto Rico’s last decade of meaningful growth. After 2006, Puerto Rico entered what became a long, grinding economic depression—year after year of contraction after the 936 era ended and cash flows turned negative.

Then the demographics poured gasoline on the fire. Census figures show Puerto Rico’s population fell about 14% from 2000 to 2020, dropping from 3.8 million to roughly 3.2 million. The 2010s were particularly brutal: roughly 456,000 people left between 2010 and 2020. Recent statistics have Puerto Rico among the world’s fastest-shrinking jurisdictions, with the population declining again in 2024 compared to the year before. And between 2008 and 2022, the departure of more than 600,000 people was estimated to cost the island about $1.2 billion in income.

For a bank, that’s not just a macro chart. It’s an existential operating environment.

Your customers are leaving. Your tax base is thinning. Your economy is contracting. Yet your franchise can’t simply relocate. Your headquarters, branch network, regulatory reality, and customer relationships are anchored to a 3,500-square-mile island in the Caribbean.

This is the backdrop First BanCorp has lived in for decades. And once you absorb that—how much is structural, how much is political, how much is demographic—you can start to understand why the bank made the choices it made, why it got into so much trouble, and why surviving at all was the first miracle in this story.

III. Origins & The Banking Landscape (1948–1990s)

It’s 1948. Postwar America is surging, and Puerto Rico is in the middle of its own reinvention. Operation Bootstrap is pulling the island out of an agrarian past and into an industrial future. Returning veterans are starting families. Cities are growing. And for the first time, a real middle class needs the thing that turns optimism into something concrete: a mortgage.

First BanCorp’s story starts right there. On October 29, 1948, it was established in Santurce as the First Federal Savings and Loan Association of Puerto Rico, with an initial capital investment of $200,000—making it the first savings and loan institution chartered on the island. Founded in San Juan by Enrique Campos del Toro, it began with a simple mission: help Puerto Ricans buy homes.

And it did. For decades, this was relationship banking in its purest form—one household at a time. The institution built its franchise slowly, essentially compounding trust: customer by customer, mortgage by mortgage. That steady pace mattered, because banking in Puerto Rico wasn’t just about moving money. It was about building the basic financial infrastructure of a modernizing society.

As the island changed, the bank’s structure changed with it. In 1983, it converted to a federally chartered savings bank. In 1994, it made the bigger leap: becoming a state-chartered commercial bank under the name FirstBank Puerto Rico.

The ownership story evolved too. In 1987, First Federal became a stockholder-owned savings bank and went public, trading on Nasdaq. In 1993, it was listed on the New York Stock Exchange under the symbol FBP. And in 1998, it reorganized into a holding company structure, forming First BanCorp as a Puerto Rico-chartered financial holding company—now under the watchful eyes of the Federal Reserve Board, the FDIC, and the Puerto Rico Office of the Commissioner of Financial Institutions.

All of this happened inside a market with a defining feature: dominance at the top.

Puerto Rico’s banking landscape has long been led by Banco Popular, the island’s largest bank, with market share consistently above 40%. By 2024, the field had narrowed dramatically: no foreign retail commercial banks operated on the island, and only three locally owned commercial banks remained—Banco Popular, FirstBank, and Oriental Bank (which began life in 1964 as Oriental Federal S&L Association).

That structure—an island-sized oligopoly—shaped everything that came next. Puerto Rico was big enough to support meaningful banking franchises, but small enough that scale made the difference between thriving and merely surviving. First BanCorp settled into a clear role: the credible number two—large enough to matter, still motivated to take share.

Then came the first steps off-island. First Federal expanded into the Virgin Islands, opening its first branch in Saint Thomas and becoming the first savings and loan institution to operate in the U.S. Virgin Islands. And in 2002, after acquiring Chase Manhattan Bank, FirstBank became the largest bank in the Virgin Islands (USVI & BVI), serving St. Thomas, St. Croix, St. John, Tortola, and Virgin Gorda with 16 branches.

By the 1990s and into the early 2000s, the bank’s personality was shifting. It had the roots of a conservative mortgage lender, but it was developing a reputation as an aggressive, growth-oriented institution. Management looked at Puerto Rico’s reliance on Section 936—already on its way out—and saw both a threat and a path forward. The threat was straightforward: when the incentives disappeared, the economy would weaken. The solution they pursued was diversification. Expand beyond Puerto Rico, especially into Florida’s booming real estate market, and the bank wouldn’t be trapped inside a shrinking home market.

The logic was clean. The outcome would be anything but.

This is the setup for the next chapter: First BanCorp’s biggest growth push—and the decisions that would later drag it to the edge.

IV. The Golden Years & Overexpansion (2000–2007)

By the mid-2000s, First BanCorp had shed its old identity as a modest savings-and-loan and remade itself into something far more ambitious: a commercial bank with off-island plans. By 2006, it had grown to more than $18.8 billion in assets—an extraordinary climb for an institution that began with just $200,000 in capital.

The strategy, on paper, was simple. Puerto Rico’s economic engine was sputtering as Section 936 neared the end of its phase-out and the manufacturing base started to thin. So First BanCorp went looking for a second home market. Florida was the obvious target: fast-growing population, soaring real estate values, and seemingly endless demand for credit.

It’s also where banking strategies go to die.

There’s an old pattern in banking that repeats with depressing consistency: the lenders that sprint into a hot new market during the boom are often the ones that get mangled when the cycle turns. They don’t have decades of local pattern recognition. They don’t know which developers always land on their feet and which ones are one missed payment away from collapse. And because they’re trying to grow quickly against entrenched competitors, they often end up taking the deals the incumbents didn’t want.

First BanCorp walked straight into that dynamic. The industry-wide slide in underwriting discipline during the housing bubble didn’t just provide a bad backdrop—it amplified every risk inherent in the expansion.

The Florida push captured the era’s optimism perfectly. In March 2005, First BanCorp acquired Ponce General Corporation, the parent of UniBank, a community bank founded in 1978 as Ponce de Leon Federal Savings. UniBank brought roughly $600 million in assets, and it deepened FirstBank Florida’s footprint across Miami-Dade, Broward, Orange, and Osceola counties. The bank also ran a real estate and commercial loan office in Coral Gables that had opened in 2004—exactly the kind of beachhead you’d want if you believed Florida would keep booming.

Management wasn’t subtle about the bet. In a 2006 press release, Dacio Pasarell, an Executive Vice President of First BanCorp, said the Florida market represented “an important strategic opportunity for First BanCorp.”

And to be fair, everybody thought that. Before the industry imploded, out-of-state banks were lining up to buy their way into Florida. Prices got absurd. A vivid example came in 2004, when Cincinnati-based Fifth Third Bancorp bought Naples-based First National Bankshares of Florida for $1.6 billion—valuations that, in hindsight, read less like disciplined capital allocation and more like late-cycle euphoria.

That’s the key timing problem: many of the riskiest loans in the whole housing era were originated from 2004 through 2007, when securitization-driven competition was at its fiercest and standards cratered across the system. First BanCorp wasn’t just expanding into Florida. It was expanding into Florida at the exact moment the entire industry’s credit guardrails were coming off.

Meanwhile, back on the island, the situation was deceptively stable. Section 936 was winding down, and the economic fundamentals were starting to rot underneath the surface—but real estate prices were still high, construction was still humming, and the banking system remained awash in deposits that needed somewhere to go. When a bank has liquidity and shareholders want growth, the easiest product to manufacture is loans.

That’s how boom-time cultures get dangerous. Banks stop competing on relationships and start competing on terms. Loan officers are rewarded for volume. Risk managers who try to slow things down get framed as people who “don’t get the market.” Credit committees stretch, then stretch again, until what used to be unacceptable becomes normal.

By 2007, First BanCorp had built what looked like a diversification success story: Puerto Rico plus Florida, growing fast, riding the property wave on both fronts. But underneath, it wasn’t an engine. It was leverage, thin underwriting, and concentration risk—packed tightly and waiting.

When the cycle turned in 2008, that waiting ended.

V. The Crisis Begins: 2008–2013 Meltdown

The collapse didn’t arrive all at once. It came like a series of doors slamming shut.

First, the U.S. housing bubble started cracking in 2007. Then Lehman Brothers failed in September 2008, and credit markets around the world seized up. And then the recession hit Puerto Rico—harder, and for longer, than almost anywhere else in the United States.

For First BanCorp, it was a two-front war.

In Florida, the real estate portfolio management had raced to build turned toxic fast. Construction loans defaulted. Condos sat empty. Borrowers walked away from properties suddenly worth less than the debt on them.

Back in Puerto Rico, the timing was even crueler. The island hadn’t recovered from Section 936’s phase-out when the global financial crisis landed. Construction lending—one of the staples of the boom years—started to rot as projects stalled midstream. Commercial real estate values dropped. Mortgage delinquencies climbed. The “diversify to Florida” bet didn’t hedge the risk. It doubled it.

This was the era when banks failed by the hundreds. The FDIC closed 465 banks from 2008 through 2012. In the five years before 2008, only 10 failed. First BanCorp wasn’t just dealing with a bad quarter or a rough cycle. It was staring at the same abyss that had swallowed institutions all across the country.

The scale of the problem demanded a reset at the top. In September 2009, Aurelio Alemán-Bermúdez became President and CEO. He wasn’t a parachuted-in outsider. He had been the company’s Chief Operating Officer and Senior Executive Vice President from 2005 to 2009, and an Executive Vice President at FirstBank from 1998 through 2009. Before that, he’d built a deep operating resume on the island: Vice President at Citibank, N.A., overseeing wholesale and retail auto financing and retail mortgages, and earlier, Vice President at Chase Manhattan Bank, N.A., responsible for banking operations and technology for Puerto Rico and the Eastern Caribbean region from 1990 to 1996.

With Alemán in the CEO seat, management framed the turnaround around four pillars: recapitalizing the bank, managing the balance sheet, retaining franchise value, and upgrading risk management.

What that meant in real life wasn’t glamorous. It was relentless. Loan workouts. Foreclosures. Provisions. Shrinking the balance sheet. Quarter after quarter of write-downs and reserve builds, under the watchful eye of regulators. In a local economy that would ultimately see three bank failures, just staying alive took discipline.

Capital was the oxygen. First BanCorp raised it where it could: about $525 million of common stock sold to institutional investors, plus the conversion of preferred stock it had issued to the U.S. Treasury under the Troubled Asset Relief Program into common stock. Even years later, the crisis still echoed on the balance sheet—by May 2016, First BanCorp still owed $124.97 million to the U.S. government under TARP.

So why did First BanCorp survive when others didn’t?

Part of it was timing, part of it was leadership, and part of it was that the core Puerto Rico franchise—while badly bruised—still had real value. Other players, like Doral and Westernbank, collapsed under even more aggressive lending and weaker capital positions. First BanCorp was sick, but it wasn’t terminal.

Alemán’s approach was painfully methodical. He didn’t try to “grow out” of the mess—a reflex that destroys banks in downturns. He focused on cleaning up what had already been done. At the same time, the bank looked for safer ways to rebuild earning power, including expanding mortgage originations, improving commercial lending operations in Florida, and buying a $400 million credit card portfolio from a Bank of America unit—newer loans meant to replace the problem-heavy real estate and construction exposure that had nearly sunk the franchise.

By 2013, the worst of the post-2008 meltdown had passed.

But Puerto Rico’s troubles weren’t ending. They were shifting. The government debt crisis was about to explode—and it would threaten to drag the entire economy, and every bank inside it, into a second catastrophe.

VI. The Puerto Rico Debt Crisis (2014–2017)

Just as First BanCorp was starting to crawl out of its near-death experience, the ground under Puerto Rico gave way.

This time, it wasn’t a housing bubble or Florida condos. It was the Commonwealth itself.

By the middle of the decade, Puerto Rico was carrying roughly $70 billion in debt and tens of billions more in unfunded pension obligations. And once the market stopped believing the government could pay, the whole machine seized. In 2014, the major credit rating agencies downgraded multiple Puerto Rico bond issues to junk status. That single label mattered. It cut the government off from the bond market, leaving it unable to roll over debt the way it had for years. With no fresh financing to plug the budget gap, the government began burning through its remaining savings while warning—correctly—that the reserves would run out.

The roots of the crisis weren’t mysterious. Puerto Rico had been running persistent deficits and using borrowing to paper over them. Financial oversight was weak. Policy decisions leaned on debt proceeds to balance budgets. And all of it was happening while the economy had been contracting since 2006, shrinking the tax base year after year. Worse, Puerto Rico didn’t have access to the same bankruptcy tools U.S. municipalities can use to restructure liabilities. When the wall arrived, there wasn’t an obvious legal exit.

By 2015, the spiral was out in the open. Puerto Rico began defaulting on its obligations and, by August 2015, had defaulted on more than $1.5 billion in debt.

Then came PROMESA.

On June 30, 2016, President Barack Obama signed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management and Economic Stability Act—PROMESA—creating a seven-member Financial Oversight and Management Board with sweeping authority over the Commonwealth’s budget and the power to negotiate a debt restructuring. With the legal protections PROMESA provided against lawsuits, Governor Alejandro García Padilla suspended payments due on July 1.

For Puerto Rico, PROMESA was a lifeline: a framework to restructure and an attempt to impose fiscal discipline where politics had failed. It arrived in a moment when the island had lost access to capital markets, its debt load was widely described as unsustainable, and pension liabilities were piling up with no realistic way to fund them.

For banks, PROMESA was something else: confirmation that the crisis was real, systemic, and going to last.

The risk came in layers. There was direct exposure—Puerto Rico government bonds on balance sheets, loans to municipalities, and financing tied to government contracts. There was indirect exposure too: when an economy is spiraling, every borrower feels it, from retailers to contractors to landlords. And there was the question nobody wanted to say out loud: if the Commonwealth’s financial system broke, could any local bank make it through?

By early 2017, Puerto Rico’s bond debt was still around $70 billion in a territory with a 45% poverty rate and double-digit unemployment—12.4% in December 2016—more than twice the mainland U.S. average. The recession had dragged on for a decade. Defaults had become normal.

First BanCorp’s posture during this period was shaped by scar tissue. After the 2008–2013 trauma, management had learned what overreach looks like, and what it costs. Government exposure was approached conservatively. The balance sheet was cleaner than it had been in years. Capital levels were stronger. Underwriting had tightened dramatically.

But the operating environment was getting worse in a different way: people were leaving. The population exodus accelerated, and in banking, that’s slow-motion erosion. Every family that relocated to Florida or Texas was one less depositor, one less borrower, one less small business account. Every shuttered storefront meant another stressed loan. Meanwhile, the competitive landscape kept compressing as weaker institutions failed or exited and the survivors fought to hold ground.

Once again, First BanCorp made the same choice that had kept it alive before: protect capital, stay disciplined, and refuse the temptation to chase short-term earnings in the middle of a structural crisis.

It worked. The bank made it through.

But Puerto Rico’s real stress test still wasn’t the debt. It was what arrived next, in September 2017, on the back of 175-mile-per-hour winds.

VII. Hurricane Maria: The Ultimate Stress Test (2017)

September 20, 2017. The date is seared into Puerto Rican memory.

Hurricane Maria tore through the northeastern Caribbean and hit Puerto Rico with historic force. It became the deadliest and costliest hurricane to strike the archipelago and the island: Puerto Rico accounted for 2,975 of the 3,059 deaths attributed to the storm, and the damage estimate reached roughly $90 billion.

In many ways, it was a worst-case scenario layered on top of an already fragile reality. Maria was widely described as the worst hurricane to hit Puerto Rico since 1928, and it arrived just two weeks after Irma had already soaked and stressed the island. This wasn’t a place with slack in the system. Puerto Rico was coming off a decade of economic decline, a shrinking population, and a banking sector that had already spent years in triage.

Then the physical infrastructure collapsed.

The storm flattened neighborhoods and crippled the power grid. In its wake, the basic utilities of modern life failed at once: the entire power grid went down, most cellular sites stopped working, and nearly half of wastewater treatment plants became inoperable. Days after landfall, the island was still almost entirely dark. Large portions of the population lacked tap water. Cell service was effectively gone.

And when the lights go out, so does the financial system. No power means no ATMs. No connectivity means no card payments. No communications means no coordination. In the immediate aftermath, many residents didn’t just lose homes and businesses. They lost access to money.

For First BanCorp—and every bank on the island—Maria wasn’t just a credit event. It was an operational nightmare with existential stakes.

How do you run a bank when there’s no power? How do you serve customers when they can’t reach branches, and branches can’t connect to anything? How do you manage a loan portfolio when a meaningful slice of borrowers has, quite literally, lost everything?

The answer wasn’t a clever playbook. It was brute-force execution: branch by branch, customer by customer, day by day.

First BanCorp mobilized generators, stood up emergency operations, and focused on the simplest, most urgent mission: get cash into people’s hands when ATMs were down and electronic payments were impossible. It implemented forbearance programs for borrowers who couldn’t pay—not as charity, but as realism. Foreclosing on a destroyed property doesn’t create a recovery; it just locks in losses and burns relationships.

What happened next is one of the most important twists in this entire story.

The expected outcome after a catastrophe like this is a wave of defaults and lasting credit damage. But credit performance was better than feared. A New York Fed study later found that Maria had only a modest, short-term impact on banks’ performance and no negative lasting effect on credit quality. A web of protections helped: homeowners’ insurance, government emergency assistance, and mortgage insurance structures tied to FHA, VA, and the GSEs. And crucially, most of the incremental losses after Maria came from loans that were already at least 90 days past due before the hurricanes ever hit.

Then came the even more surprising part: deposits flowed in.

Insurance payouts arrived. Federal aid began to move. Remittances from the Puerto Rican diaspora surged. Money flooded into the banking system, and First BanCorp was one of the pipes it flowed through. In some cases, the crisis hardened decisions the other way—customers who had been on the fence about leaving chose to stay. And the bank’s role during the blackout deepened relationships that had been built over decades.

The federal response promised massive reconstruction aid. Governor Ricardo Rosselló estimated at least $90 billion in damage, a figure that would eventually translate into billions flowing into Puerto Rico’s economy—funds that, inevitably, would pass through the island’s banks.

First BanCorp had made it through the ultimate stress test. Now the question was whether the aftermath would finally give Puerto Rico—and the institutions anchored to it—the recovery that had been out of reach for more than a decade.

VIII. The Turnaround: 2018–2020 Phoenix Rising

By 2018, First BanCorp had already lived through what would normally be three separate careers’ worth of trauma: the 2008–2013 financial meltdown, the 2014–2017 debt crisis, and then Hurricane Maria. Survival had come with a cost—branch closures, layoffs, loan losses, capital raises, and years of regulatory pressure. But it also left the bank with something most competitors didn’t have anymore: hard-earned discipline, tighter underwriting, and the instinct to protect capital before chasing growth.

And then, in a twist that would’ve sounded impossible a few years earlier, First BanCorp went on offense.

In October 2019, FirstBank announced its intention to purchase Banco Santander de Puerto Rico. Regulators approved the transaction on July 28, 2020, and it closed on September 1, 2020.

Santander’s Puerto Rico franchise came with real heft. As of July 31, 2020, it had approximately $5.5 billion in assets, $2.7 billion in total loans, and $4.2 billion in deposits. First BanCorp paid cash of approximately $394.8 million as a base purchase price for 117.5% of Banco Santander’s core tangible common equity, plus $882.8 million for Santander’s BanCorp excess capital.

CEO Aurelio Alemán put it simply: “Today we completed the acquisition of Banco Santander announced back in October 2019. The completion of this transaction marks a significant milestone in our journey.”

And it was. The deal didn’t just add balances—it reshaped the franchise. First BanCorp said the acquisition expanded its ability to serve customers through a network of 73 branches throughout Puerto Rico, strengthening its presence in San Juan, Bayamón, Caguas, and Guaynabo, and expanding reach in the western and southern regions of the island.

On a pro forma basis using June 30, 2020 figures, the company expected that after closing it would have approximately $18.8 billion in assets, a $12 billion loan portfolio, $15.4 billion of deposits, and roughly 650,000 customers.

Management framed the strategic logic with unusual clarity: “We expect that this acquisition will significantly improve our scale and competitiveness in Puerto Rico and will be financially compelling to optimize the use of our excess capital.”

That phrase—use of excess capital—was the tell. This was no longer a bank begging for oxygen. Under Alemán, First BanCorp had gone from triage to optionality. His tenure included engineering the turnaround of a troubled institution in a local economy that had already produced three bank failures, and executing a strategic plan that led to the $520 million recapitalization of the Corporation in 2011.

Now the playbook was about focus, not reach. The strategic refocus was straightforward: pull back from Florida outside targeted lending, double down on Puerto Rico, and operate with a fortress balance sheet. At the same time, the bank pushed harder on technology. Company reports show active retail digital platform users reached approximately 300,000 by 2021—up 77% from prior years—driven by features like mobile deposits and online transfers.

The macro backdrop was finally shifting too. PROMESA began to deliver something Puerto Rico hadn’t had in years: a path to fiscal clarity. The Oversight Board and the Government of Puerto Rico restructured about 80% of the island’s outstanding debt, lowering total liabilities from more than $70 billion to $37 billion, a move projected to save Puerto Rico more than $50 billion in debt service payments.

And the timing couldn’t have been better. First BanCorp closed the Santander acquisition just as reconstruction dollars were starting to move more meaningfully, just as the island’s fiscal outlook was becoming less chaotic, and just as the pandemic kicked off a surprising new chapter: remote-work migration and renewed interest in Puerto Rico as a place to live and do business.

IX. COVID & The Modern Era (2020–2024)

When COVID hit in March 2020, the obvious assumption was that Puerto Rico would get crushed—and that its banks would follow. This was an island economy tied to tourism, still rebuilding from Maria, with fragile infrastructure and a healthcare system nobody wanted to stress-test.

But the story didn’t play out that way.

Puerto Rico came through the pandemic better than most expected, and the recovery had real momentum. By mid-2022, private-sector employment had climbed to a fifteen-year high. After a dip in 2022, real GDP growth turned positive again in 2023.

A big reason was simple: money arrived, and it arrived at scale. Federal support flowed through PPP loans, enhanced unemployment benefits, and stimulus checks. At the same time, disaster-recovery dollars kept moving from multiple events—Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017, the 2019 and 2020 earthquakes, and Hurricane Fiona in 2022. For an economy that had spent years starved for investment, those flows mattered.

Then there was a second, more surprising tailwind: people. Remote work made Puerto Rico newly “reachable” for mainland earners, and Act 60’s tax incentives pulled in a visible wave of newcomers, including cryptocurrency entrepreneurs and remote professionals. Tourism also snapped back hard. Arrivals rose sharply in 2023, and both 2022 and 2023 set records for arrivals and room tax revenue. Total inbound air passengers increased 18.7% in 2023, a clean signal that the island’s most important service export was roaring back.

For First BanCorp, this was close to the best possible macro setup. The Santander acquisition was in the middle of integration. Credit was getting cleaner. Deposits held up. And when rates started rising in 2022, the bank had the kind of balance sheet that could actually benefit—net interest margins expanded instead of getting squeezed.

By 2024, the turnaround showed up in the numbers. First BanCorp reported record revenues, with net interest income inching higher year over year. The loan portfolio grew as well, led by commercial, construction, and consumer lending.

What mattered more than the totals was where the bank was putting money to work. It financed new loans for small businesses across Puerto Rico, funded projects tied to the tourism rebound—development, construction, and refinancing for hotels and tourism-related businesses—and provided financing for clean-energy environmental projects and for manufacturing factory expansions.

And then came the milestone that tells you a bank is no longer in triage: capital return. Dividends resumed. Buybacks were authorized. Just a few years earlier, when the company was operating under regulatory consent orders, that would have been unthinkable.

Looking ahead, forecasts called for modest Puerto Rico growth in the 1–2% range, supported by federal disaster relief, infrastructure spending, and the island’s resilient manufacturing base. After two decades of crises stacked back-to-back, “modest” was more than enough. For First BanCorp, it was finally a normal-ish operating environment—and after everything that came before, normal started to look like a competitive advantage.

X. Recent Inflections & Current State (2024–Present)

The latest results show just how complete the turnaround has been. In Q4 2024, First BanCorp reported net income of $75.7 million, or $0.46 per diluted share. For the year ended December 31, 2024, it reported net income of $298.7 million, or $1.81 per diluted share, compared to $302.9 million, or $1.71 per diluted share, for the year ended December 31, 2023.

The cleaner balance sheet is just as telling. Nonperforming assets fell to a record low of 61 basis points of total assets—a level that says the crisis-era loan book is no longer the defining feature of the company.

And once a bank is truly out of triage, it does the thing it couldn’t do for years: give capital back. In early 2025, First BanCorp announced that its Board of Directors declared a quarterly cash dividend of $0.18 per share, a 13% increase, or $0.02 per common share, compared to its most recent dividend paid in December 2024.

As CEO Aurelio Alemán put it: "We are pleased to announce another increase to our common stock dividend. This, combined with our share buyback program, underscores our unwavering commitment to maximizing shareholder value. These actions are supported by our consistent long-term performance, strong capital position, and positive future outlook."

The business is still growing, too. Total loans increased by $310 million, with meaningful contributions from consumer, commercial, and mortgage lending across Puerto Rico and Florida.

Under the hood, the company continued to run with significant cushion. First BanCorp maintained strong liquidity and regulatory capital ratios well above “well-capitalized” levels—exactly the kind of conservative posture you’d expect from a team that survived the last decade.

That battle-tested leadership is also thinking about what comes after it. In early 2025, the company announced a strategic reorganization aligned with its corporate succession plan. Alemán, who has served as President and Chief Executive Officer since September 2009, has been the central figure through the meltdown, the debt crisis, Maria, and the recovery—so formalizing the next chapter matters.

Zooming back out, the Puerto Rico backdrop remains cautiously constructive. The economy rebounded, and by mid-2022 private-sector employment was at a fifteen-year high. The medical manufacturing cluster is still a cornerstone of the island’s economy, even if employment remains well below its 2005 peak.

Most forecasts call for modest growth of around 1–2% in the coming years, supported by federal disaster relief, infrastructure investment, and a resilient manufacturing base. Not a miracle, not a boom—just something Puerto Rico hasn’t reliably had in a long time: a steady enough environment for a disciplined bank to keep compounding.

XI. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

To understand why First BanCorp can be both “just a regional bank” and a genuine turnaround story, you have to look at the structure of the market it operates in. Puerto Rico banking is a strange mix: a tightly bounded geography, a heavily regulated industry, and a customer base that has been through enough crises to prize survival over flash.

Seen through the classic strategy lenses, that structure creates a market that’s more protected than most, but never completely comfortable.

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis:

1. Competitive Rivalry (Moderate to High)

In practice, Puerto Rico is a two-horse race. Banco Popular is the clear leader with roughly 45% share. First BanCorp sits in the strong number-two spot at around 25% after the Santander acquisition. Oriental Bank, founded in 1964 as Oriental Federal S&L Association, and a handful of smaller players make up the rest.

What makes rivalry feel intense isn’t a crowded field—it’s that the field is so concentrated. In 2024, there were no foreign retail commercial banks operating on the island, and only three locally owned commercial banks remained: Banco Popular, FirstBank, and Oriental.

The good news is that competition mostly shows up in rates, service, and digital features—not in suicidal price wars. The survivors of the last decade learned the hard way that reckless share grabs destroy the whole industry’s economics. That’s where First BanCorp’s edge shows up: credibility earned under pressure, and a fortress-balance-sheet reputation that matters a lot when your customers remember bank failures and island-wide blackouts.

2. Threat of New Entrants (Low)

Starting a bank anywhere is hard. Starting one in Puerto Rico is harder.

A new entrant would need FDIC approval, meaningful capital, and serious BSA/AML compliance capabilities from day one. Then there’s the local complexity: a legal environment that doesn’t map perfectly to the mainland, Spanish as the primary business language, and market dynamics that can feel like a developing economy even though everything is dollar-denominated.

Scale makes the barrier even taller. Branch networks, modern digital platforms, cybersecurity, and compliance are expensive fixed costs. In a market this size, you need real volume for those investments to make sense. And after a period that included multiple bank failures, regulators are understandably cautious about letting new charters in.

Even before the crises, mainland banks mostly stayed away. For the megabanks, it’s too small to matter. For smaller banks, it’s too unfamiliar and complex. For most regionals, it’s perceived as too risky.

3. Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Low)

In banking, deposits are the raw material. First BanCorp’s deposit base is spread across a broad set of retail and commercial customers, so no one group can really dictate terms. Government deposits can create some concentration risk, but it’s manageable in context.

And because the bank runs with strong liquidity, it doesn’t have to overpay for funding. When you don’t need deposits to survive, you can be rational about what you’re willing to pay for them.

4. Bargaining Power of Buyers (Moderate)

Borrowers have options, but they’re not infinite.

Large corporations can tap mainland capital markets in theory, but in practice many still want a local bank that can handle cash management, payroll, treasury services, and the daily friction of running operations on the island. A distant institution can offer a rate; it can’t always offer a relationship that actually works on the ground.

For consumers, switching costs are real. Changing direct deposit, rebuilding bill pay, moving a mortgage relationship, and redoing automatic payments is just annoying enough to prevent churn. On top of that, language and culture matter—Spanish-speaking bankers with local context aren’t instantly replaceable by a mainland call center.

Digital competition from mainland banks and fintechs is showing up at the edges, especially for rate-sensitive deposits. But those players often struggle to replicate full-service banking for Puerto Rican households and businesses.

5. Threat of Substitutes (Low to Moderate)

There are alternatives, but most are limited.

Credit unions exist, but generally lack the scale and commercial-lending breadth of a large bank. Mainland banks can provide digital access, but not local presence or expertise. Fintech and crypto ventures have been attracted by Act 60’s tax benefits, yet regulatory uncertainty keeps the impact contained.

Shadow banking is minimal. Government lending programs can support certain segments, but they don’t replace commercial banking. And the classic substitute—capital markets disintermediation—doesn’t take much share in a market of Puerto Rico’s size and structure.

Overall Assessment: Post-consolidation, Puerto Rico banking is moderately attractive. Barriers to entry are high and substitutes are limited, which supports profitability. But competition among the few scaled players, plus the lingering regulatory and macro overhang of the last decade, keeps the ceiling on returns. The island’s uniqueness is the moat: big enough to sustain serious banks, small enough—and specific enough—to deter most outsiders.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis:

1. Scale Economies (★★★★☆)

With more than $19 billion in assets, First BanCorp gets real leverage from scale. Technology, compliance, risk systems, and a dense branch footprint are all fixed costs that become far more manageable when spread across a larger base.

This matters most in compliance. BSA/AML programs, stress-testing capabilities, and the broader regulatory infrastructure demand major investment. Smaller competitors feel those costs as a tax; First BanCorp can amortize them and still price competitively.

2. Network Effects (★☆☆☆☆)

Traditional banking doesn’t get much stronger just because more people bank there. Payment rails like Zelle, ATM networks, and card systems do create some network value—but they’re commoditized and widely shared. Network effects aren’t what protects First BanCorp.

3. Counter-Positioning (★★☆☆☆)

After living through multiple crises, First BanCorp’s conservatism became a strategic position. The fortress approach isn’t just “being cautious.” It’s a form of counter-positioning against anyone tempted to grow aggressively or loosen standards to win share.

In theory, a digital-first challenger could counter-position against branch-based banks. In practice, that hasn’t shown up at scale in Puerto Rico. Here, “boring banking” is the product—and it’s what customers often want.

4. Switching Costs (★★★★☆)

For commercial clients, switching is painful. Loans, treasury management, payroll services, and cash management get woven into daily operations. Moving banks isn’t just a paperwork exercise—it’s operational risk.

For consumers, the friction is lower but still meaningful: direct deposit, bill pay, automatic payments, and habit are powerful anchors. Add in language and local-knowledge advantages, and retention becomes even stickier. First BanCorp keeping more than 80% of customers through multiple crises is a real-world proof point.

5. Branding (★★★☆☆)

FirstBank is a familiar name across Puerto Rico, backed by more than seven decades of operating history. And in banking, the most valuable brand attribute isn’t excitement—it’s trust.

Crisis survival became the brand. The bank that stayed standing. The bank that kept operating through the debt spiral. The bank that worked to get cash moving after Maria. It’s a “safe hands” brand more than an aspirational one, but in this market, that’s often the stronger position.

6. Cornered Resource (★★★☆☆)

Some resources are hard to buy, even if you have money.

Prime branch locations are legacy assets that would be expensive and slow to replicate. The deposit base is tied to long relationships and local knowledge, not just rates. Government banking relationships, like payroll and treasury services, tend to be sticky once established.

And then there’s the most overlooked resource: management scar tissue. A team that has navigated a global financial crisis, a sovereign-style debt crisis, and a Category 5 hurricane has institutional knowledge you can’t hire off a résumé.

7. Process Power (★★★★☆)

If First BanCorp has a “secret weapon,” it’s process power—the operational excellence forged by necessity during the crisis years.

Credit underwriting: Working through more than $2 billion in loan losses leaves a mark. The institution learns what can go wrong, where optimism hides risk, and how small underwriting decisions compound.

Workout and recovery: Years spent restructuring, foreclosing, and disposing of assets created a muscle most banks only build in downturns. Those processes are now embedded.

Regulatory compliance: Systems built under intense scrutiny often end up stronger than what peers maintain in normal times. What started as survival-grade compliance can become an advantage.

Risk management: The culture tilts cautious, but not naive. It’s conservative with context—an organization trained to look for the risks others rationalize away.

Synthesis: First BanCorp's Moat

Primary Powers: Process Power + Switching Costs + Scale Economies

Secondary Powers: Cornered Resource (relationships, locations, experience)

Emerging: Counter-positioning (conservatism as strategy)

First BanCorp is a crisis-forged fortress operating inside an oligopolistic market with high structural barriers. Its advantage isn’t flashy innovation. It’s discipline, trust, and institutional knowledge that can’t be copied without living through the same near-death experiences. And Puerto Rico itself is part of the moat: complicated enough to demand local expertise, and small enough to keep most mainland competitors from bothering.

Key Questions for Investors:

Can First BanCorp stay disciplined when times are good? The same caution that saved it in downturns can become a growth constraint in an upcycle.

Will Puerto Rico’s structural challenges—population decline and fiscal constraints—shrink the market over time? Even the best operator can’t outgrow a steadily shrinking addressable base forever.

How durable is the duopoly with Popular? The equilibrium looks stable, but disruption rarely announces itself in advance.

Can digital challengers win meaningful share without physical presence? It’s still unclear whether fintech can overcome Puerto Rico’s mix of local complexity, relationship banking, and crisis-driven preference for stability.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case: "The Puerto Rico Recovery Play"

1. Market Structure = Pricing Power

Puerto Rico banking has effectively become a duopoly. Banco Popular is the leader, and First BanCorp is the scaled number two. After years of consolidation, the industry has fewer players, higher barriers to entry, and a shared memory of what happens when banks compete too aggressively.

That tends to produce something rare in banking: rational competition. And in a market like that, First BanCorp doesn’t need heroic growth to deliver strong results. It just needs to keep doing what it’s been doing—take share around the edges, protect credit, and let the structure of the market do the work.

2. Credit Quality Tailwind

The simplest bull argument is that the mess is finally behind them.

Nonperforming assets hit a record low at 61 basis points of total assets. The loan book has been re-underwritten after years of hard lessons, and the crisis-era vintages that drove so much pain are steadily rolling off. If Puerto Rico stays even modestly stable, that sets up a world where credit costs normalize at levels far below what this institution was built to survive.

3. Capital Return Machine

First BanCorp is back to the thing healthy banks get to do: return capital.

Capital levels sit well above regulatory requirements. The Board raised the quarterly dividend to $0.18 per share, up 13%, and the bank has been actively buying back stock, repurchasing more than 3.8 million shares since July 2024. The message is straightforward: this is no longer a bank hoarding capital to appease regulators. It’s a bank with the capacity—and the confidence—to give it back.

And because the stock trades around tangible book value, buybacks aren’t just cosmetic. They’re accretive.

4. Puerto Rico Stabilization/Recovery

The island doesn’t need to become an economic miracle for First BanCorp to win. It just needs to stay standing.

The labor market already showed meaningful improvement, with private-sector employment reaching a fifteen-year high by mid-2022. Population decline appears to be slowing, and there are real pockets of new activity: remote work migration, nearshoring interest, and Act 60-driven inflows. Tourism has been resilient. Manufacturing remains a foundation. Debt restructuring is largely complete, giving the island more fiscal clarity than it’s had in years. And while reconstruction funds move slowly, they continue to flow.

Even the grid—still fragile and frustrating—represents potential upside if modernization efforts finally translate into reliability.

5. Operating Leverage

This is where the turnaround turns into compounding.

With rates stabilizing, asset yields have repriced faster than deposit costs. Net interest margin improved to 4.33% from 4.25%. The efficiency ratio improved to 51.57% from 52.41%. Those aren’t just incremental improvements—they’re signals that the machine is getting tighter.

In banking, once the balance sheet is clean and the cost base is set, small amounts of loan growth can drive outsized earnings growth. That’s the operating leverage story, and it’s why a “boring” bank can become a great stock in the right setup.

6. Valuation Disconnect

Despite the turnaround, First BanCorp still trades like a bank with a permanent question mark over it—about 8–10x earnings and around tangible book value. Meanwhile, many mainland regional banks trade at higher multiples.

If investor perception of “Puerto Rico risk” continues to improve, even modest multiple expansion could add to returns that are already supported by earnings growth and capital return.

The Bear Case: "The Inescapable Geography"

1. Structural Demographic Decline

The bear case starts with a brutal reality: the market may still be shrinking.

Puerto Rico is one of the fastest-declining population jurisdictions in the world. Forecasts call for continued decline through 2029, falling by about 100,000 people, or 3.13%, to a little over 3.1 million—its lowest level since 1977. Birth rates have fallen sharply, the population is aging, and even if the exodus slows, the direction is still negative.

For a bank, a shrinking population is a headwind you can’t “execute” your way out of forever. Over time, it turns growth into a knife fight.

2. Puerto Rico Fiscal Time Bomb

Debt restructuring improved the picture, but it didn’t erase the underlying fragility. Pension obligations remain a major unresolved problem. The island’s reliance on federal funding—about 46% of the budget—creates real political risk. And with a pressured tax base, the system still has the feel of something that can tip back into crisis under the wrong conditions.

3. Energy/Infrastructure Nightmare

The grid is still a daily operational risk for the entire economy. PREPA debt is unresolved, blackouts persist, and Puerto Rico experienced island-wide power cuts in FY 2025 (July 2024–June 2025), affecting every sector.

Reconstruction funds have been bottlenecked, and climate risk isn’t theoretical—it’s a recurring threat, with more intense hurricanes increasing the odds of another Maria-style disruption.

4. Competitive Threats

Banco Popular’s dominance—roughly 45%+ share—caps upside. Meanwhile, mainland digital banks can cherry-pick the most rate-sensitive deposits without the cost of branches. Fintech continues to unbundle parts of banking, and the Act 60/crypto cohort may not build durable relationships with local institutions.

The risk isn’t that First BanCorp loses its core franchise overnight. It’s that growth and pricing power get quietly pressured over time.

5. Regulatory Overhang

Regulators have long memories, especially after a decade that produced multiple bank failures on the island. Even with dramatically improved credit and capital metrics, First BanCorp can still operate under a higher bar of scrutiny than a “normal” mainland regional bank.

That matters because it can constrain capital return, raise compliance costs permanently, and complicate M&A—both as an acquirer and as a target.

6. Interest Rate/Economic Risk

Puerto Rico banks are asset-sensitive, so rate cuts can compress net interest margin. And Puerto Rico historically tends to experience an amplified version of mainland cycles—when the U.S. slows, Puerto Rico can get hit harder.

Commercial real estate exposure, estimated at 20–25% of the portfolio, remains a vulnerable area. And there have been early signs of stress in consumer lending, with increases in early delinquencies noted in the consumer loan segment.

7. Valuation Trap

The stock can look cheap and still be a trap.

If earnings are being flattered by provision releases, core profitability may be lower than it appears. Limited institutional ownership can create liquidity issues. And the combination of ESG concerns, climate exposure, and Puerto Rico’s unresolved political status can justify a persistent discount in the market’s eyes.

8. Succession Risk

Aurelio Alemán-Bermúdez has been President and CEO since 2009. After more than 15 years, succession isn’t a question of if, but when. The same continuity that powered the turnaround can become a risk if the transition isn’t executed cleanly.

Key KPIs to Track:

1. Net Interest Margin (NIM): The heartbeat of bank earnings. A target range of 4.2–4.5% is healthy; compression below 4.0% is a warning sign.

2. Nonperforming Assets to Total Assets: Currently at a record low of 61 basis points. Staying below 1.0% signals a clean book; moving above 1.5% suggests meaningful deterioration.

3. Efficiency Ratio: The simplest read on operating leverage. Below 50% is the goal; above 52% suggests the cost story is stalling; above 55% implies structural friction.

Together, these metrics capture the essentials: margin, credit, and costs. And in banking, the trend matters as much as the level—because the direction is usually what tells you the next chapter before the headline numbers do.

XIII. Epilogue: What Comes Next

The biggest question hanging over First BanCorp is succession. Aurelio Alemán has led the company since 2009—through the long cleanup after the financial crisis, Puerto Rico’s debt spiral, Hurricane Maria, the pandemic, and the Santander acquisition. Whenever he steps aside, it won’t just be a CEO change. It’ll be the end of the turnaround’s defining chapter.

That’s why the strategic reorganization announced in early 2025 matters. It reads like a board trying to make the next era feel less like a handoff and more like a continuation. The real test is whether the discipline that saved the bank—tight underwriting, capital-first thinking, and a refusal to chase easy growth—lives in the institution, or whether it mostly lived in the people who carried it through the crises.

Then there’s M&A, the ever-present “what if” in a consolidating industry. Could First BanCorp be acquired? It’s possible in theory, messy in practice. Bank deals are hard enough; bank deals in Puerto Rico come with extra layers of regulatory scrutiny and political complexity. Banco Popular might love to remove its only scaled rival, but antitrust issues would loom large. A mainland super-regional could see a valuable franchise with real market position, but Puerto Rico’s unique risk profile—and the need for local expertise—likely keeps most would-be buyers on the sidelines.

Puerto Rico’s political status still sits in the background, shaping the rules without ever resolving them. Statehood could bring full parity with federal programs, but also different tax dynamics. Independence would imply an entirely new national framework for banking. And the status quo preserves today’s operating reality, while leaving the fundamental question unanswered—an uncertainty premium that never fully goes away.

Climate risk is the more immediate, practical threat. Maria proved First BanCorp can operate in catastrophe conditions. But “can survive” isn’t the same thing as “wants to repeat.” More frequent and more severe hurricanes mean repeated operational stress, interrupted commerce, and potential credit losses. And Puerto Rico’s fragile energy grid makes every storm worse: when power fails, everything fails, from ATMs and branches to merchants trying to run payroll.

The digital future adds another layer. First BanCorp has invested heavily, but banking technology is an arms race with no finish line. Mainland fintechs can nibble at the edges—rate-sensitive deposits, simple consumer products—without building a single branch. The counterweight is that Puerto Rico still rewards local presence: language, culture, relationships, and the kind of on-the-ground competence customers remember when the island goes dark. The question is whether that friction remains strong enough as more of banking moves onto screens.

There are also potential tailwinds. Nearshoring and Act 60 pulled attention and capital to the island in the pandemic era, along with a visible wave of newcomers. But incentives fade, and other jurisdictions can compete. The durability will depend on whether those flows translate into lasting businesses and stable residents, not just a temporary arbitrage.

And looming over all of it is the simplest certainty in this story: there will be another crisis. The only unknown is what form it takes. When it arrives, does First BanCorp have the balance sheet—and the nerve—to be an acquirer again? Or does it do what kept it alive before: pull the shutters down, protect capital, and outlast the storm?

For investors, that may be the real takeaway. First BanCorp isn’t the fastest horse, and it’s not a conventional growth story. Puerto Rico’s structural challenges are real, and they won’t disappear. But this is a company built around endurance. And in a market that often rewards the loudest narrative, there’s a quiet edge in owning the institution that has already proven it can take the hits—and keep standing.

Sometimes the best investment isn’t the one that promises to change the world. Sometimes it’s the one that simply refuses to die.

XIV. Further Reading

If you want to go deeper—into the filings, the policy framework behind the debt restructuring, and the research on how Puerto Rico’s banks performed under stress—these are the best places to start.

Primary Sources: - First BanCorp Investor Relations (fbpinvestor.com): annual reports, 10-Ks, quarterly filings, and investor presentations - PROMESA Oversight Board reports: fiscal plans, economic forecasts, and restructuring documents - Federal Reserve Bank of New York Puerto Rico Economic Indicators: quarterly economic data and analysis

Academic and Government Analysis: - GAO reports on Puerto Rico’s fiscal crisis: detailed coverage of the debt build-up, the restructuring process, and the policy tradeoffs - Congressional Research Service reports on PROMESA and its implementation - New York Fed staff study “Banks versus Hurricanes: A Case Study of Puerto Rico”

Industry Context: - FDIC, “Crisis and Response: An FDIC History, 2008–2013,” for a regulator’s-eye view of the era that reshaped U.S. banking - Puerto Rico Planning Board economic reports for official GDP estimates and activity indices

Books for Broader Context: - “Fantasy Island: Colonialism, Exploitation, and the Betrayal of Puerto Rico” by Ed Morales - “Puerto Rico: What Everyone Needs to Know” by Jorge Duany

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music