EVgo: Powering America's Electric Future

I. Introduction: From Scandal to Infrastructure Giant

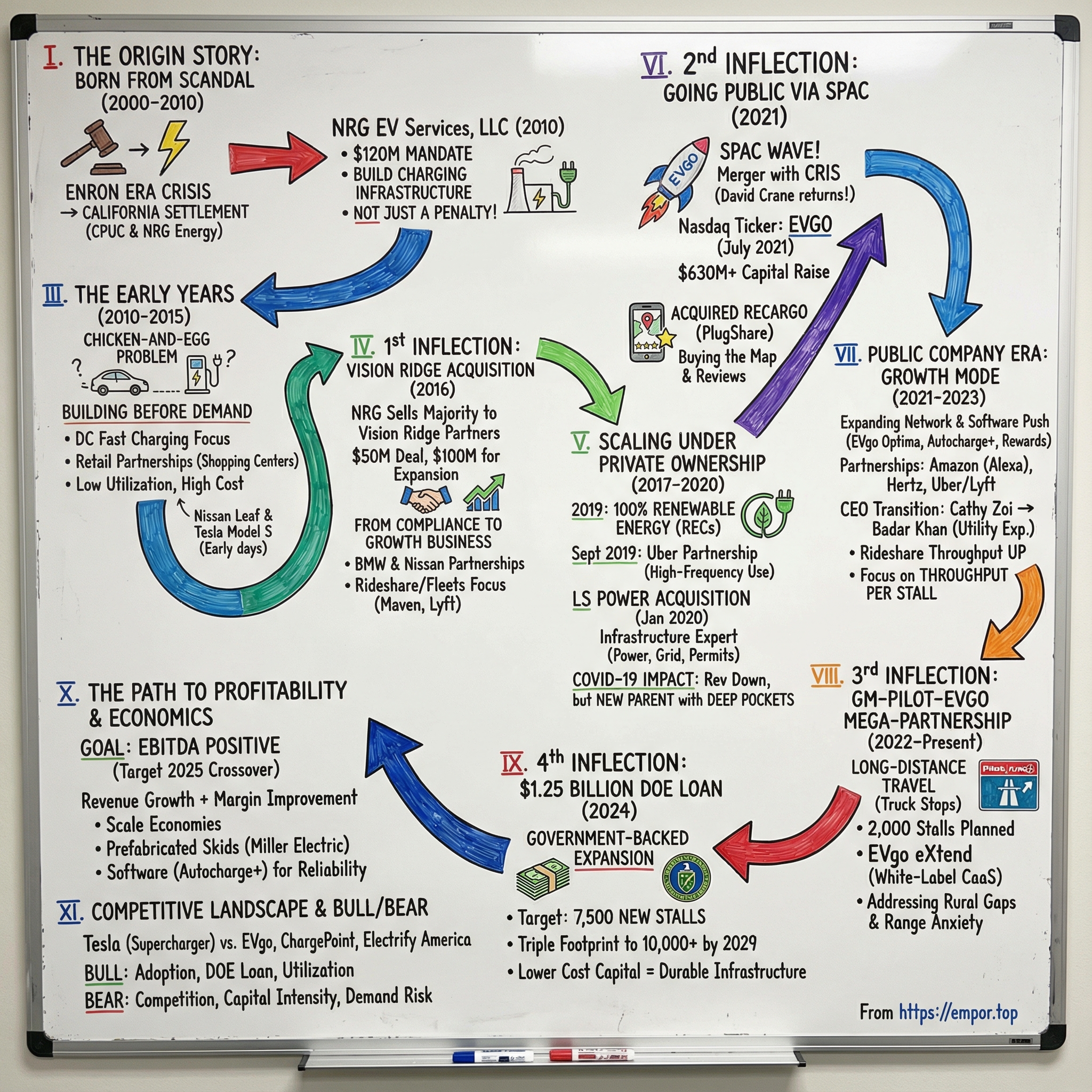

What do Enron’s market games, a $102.5 million regulatory settlement, and the future of American transportation have in common? EVgo.

This company didn’t start as a scrappy startup with a slide deck and a dream. It started as a kind of corporate penance: a charging network born out of regulation, shaped by ownership handoffs, and ultimately built on a simple, audacious bet—that Americans would one day trade gas pumps for sleek boxes that dispense electrons.

Today, EVgo operates one of the largest public fast-charging networks in the United States, with more than 1,100 fast-charging locations across 47 states and over 1.6 million customer accounts. It’s publicly traded on Nasdaq under the ticker EVGO, and like just about everything in the EV world, its valuation has risen and fallen with the market’s mood. But the numbers don’t capture what makes EVgo interesting.

The real story is the problem EVgo was created to solve—and the trap that catches every new infrastructure category: you can’t get drivers to buy electric cars if they don’t trust they can charge them, and you can’t justify building chargers if there aren’t enough drivers. It’s the same chicken-and-egg dynamic that defined railroads, broadband, and smartphones. Someone has to build first, while demand is still a theory.

EVgo’s twist is that it didn’t get to wait. A regulatory mandate pushed NRG Energy to start building charging infrastructure before the market was ready. What looked like punishment turned into a head start—and eventually, into a platform sturdy enough to attract serious capital, including major government backing.

That’s why the most recent chapter is so consequential. With a Department of Energy loan guarantee, EVgo plans to build roughly 7,500 new public fast-charging stalls nationwide, bringing its owned-and-operated network to at least 10,000 stalls in the U.S. In plain terms: a plan to more than triple its footprint, driven by the belief that the EV transition has moved from possibility to inevitability.

This story turns on four inflection points: a birth from scandal, a private equity-led transformation, a SPAC-fueled debut on the public markets, and a government-backed infrastructure buildout. Each one shows what it really takes to create the “gas stations of the future”—and how messy the path can be between a big idea and a profitable, reliable network.

II. The Origin Story: Born from Scandal

Picture California in the summer of 2000: rolling blackouts rippling across the state, offices going dark, and electricity prices jumping to levels that felt impossible—until it became clear they weren’t just “high.” They were engineered. The California energy crisis was later tied to market manipulation by Enron and a web of power traders who exploited the state’s newly deregulated electricity markets. The political fallout was enormous. Governor Gray Davis was recalled. And ratepayers were left holding the bag for long-term power contracts they never should have needed in the first place.

A decade later, that mess unexpectedly produced something new: EVgo.

In 2010, EVgo was created as part of a settlement between NRG Energy and the California Public Utilities Commission, rooted in the aftermath of the Enron-era crisis. Under the deal, NRG wasn’t just asked to pay money—it was required to build. Specifically, it had to invest roughly $100 million in public EV charging infrastructure across California.

That’s the part that makes this origin story so unusual. Regulatory settlements usually end with a check and a press release. This one turned into a statewide construction plan. The CPUC–NRG settlement totaled $120 million: a $20 million payment, plus the much larger commitment to deploy charging—more than 200 fast-charging stations, and more than 10,000 Level 2 chargers.

NRG’s connection to the crisis ran through Dynegy Energy, a company NRG acquired in 2006 that had participated in the price-gouging during the 2000–2001 period. And NRG was careful to draw a bright line between punishment and infrastructure. As NRG executive David Knox put it at the time, the cash was the penalty; the charging buildout was something else entirely. The $20 million would go toward ratepayer relief, but the much larger investment wasn’t “going to the state.” It was a commitment to build EV infrastructure.

That distinction mattered. A straightforward penalty would have been forgettable. This was different: California effectively forced a major energy company to become an early builder of EV charging, years before the market could remotely justify it on its own.

EVgo was formally established in October 2010 as NRG EV Services, LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of NRG Energy, created to develop and operate charging infrastructure—primarily in California.

NRG’s CEO then was David Crane, a central character not just in NRG’s clean-energy push, but later in EVgo’s story as well. Announcing the settlement, Crane framed it as both infrastructure and policy: “With this agreement, the people of California will gain a charging infrastructure ready to support their current and future fleet of electric vehicles,” he said, tying it directly to the state’s Zero Emission Vehicle mandate.

Crane’s broader ambition at NRG was to reposition the company around the energy transition. Over his tenure, NRG pushed deeper into renewables, home solar, carbon capture, and—through EVgo—electric vehicle charging. Whatever you think of the strategy, the throughline was clear: Crane wanted NRG to be early to the next energy era.

Late in 2010, NRG launched the EVgo network, positioning it as the first completely private, public charging network for electric vehicles.

And the settlement wasn’t just about putting chargers anywhere and calling it a day. It spelled out the blueprint: at least 200 DC fast-charging stations, battery buffer systems to manage grid demand, and Level 2 charging at multi-unit dwellings—aimed at the high-traffic urban and suburban corridors where early EV adoption was most likely to take root.

In 2011, EVgo opened its first public fast-charging station, focusing early rollout in Southern California to hit settlement milestones and to catch the first real wave of modern EVs, like the Nissan Leaf.

Not everyone was thrilled. Competitors complained that the settlement effectively handed NRG a protected position in a new market, arguing it amounted to a fractional resolution of much larger claims tied to the crisis. Legal challenges followed, including a lawsuit seeking to stop NRG from installing chargers under the settlement.

They didn’t succeed. A California appeals court dismissed the effort, and the buildout moved forward.

And that’s the twist: what started as a mandate became an advantage. While everyone else in EV charging had to argue for every dollar of capital against uncertain demand, EVgo had no choice but to build. There was, effectively, a clock running. The obligation was real—and in hindsight, it forced EVgo into exactly the position you’d want to be in before the market took off.

III. The Early Years: Building When Nobody Was Driving

Imagine trying to open gas stations in a country where hardly anyone owns a car yet. That was EVgo’s reality in the early 2010s. The Nissan Leaf had only just launched, and the Tesla Model S was still on its way. Electric driving lived mostly in early-adopter circles and long-range forecasts—while the hard, physical work of building charging stations had to happen in the real world, on real timelines, with real construction crews.

This was the chicken-and-egg problem in its purest form: without chargers, people won’t buy EVs; without EVs, chargers don’t make money. That loop kept most private capital on the sidelines. EVgo’s advantage was unusual and uncomfortable—NRG didn’t get to wait for demand. The settlement required buildout, whether utilization was high, low, or basically nonexistent.

So EVgo started laying track before the train showed up.

By 2015, the network was pushing beyond its early California footprint. In January of that year, EVgo announced its first five stations in Tennessee—an early signal that this wasn’t going to stay a coastal experiment. And by July 2015, the NRG eVgo network had grown to roughly 350 stations across 19 metro markets, with sites in places like Texas, Maryland, and the Northeast. A big part of that expansion leaned on retail hosts—shopping centers and other high-visibility locations that made stations easier to find and easier to use. Even then, growth had friction: EV adoption was still limited, and every new site could trigger utility coordination, grid upgrades, and regulatory steps that stretched timelines.

The business model, though, was punishing. Many stations sat quiet for long stretches. The equipment was expensive. Electricity pricing and demand charges didn’t care how few cars showed up. At low utilization, the unit economics of DC fast charging could look almost absurd.

But EVgo made a bet that would shape everything that came after: it prioritized DC fast charging instead of leaning primarily on Level 2. Level 2 chargers were cheaper and common elsewhere in the market, but they came with a problem that wasn’t technical—it was behavioral. They took hours. DC fast charging, by contrast, could deliver a meaningful charge in around half an hour or less. That was the first version of “charging that feels like a stop,” not “charging that feels like an overnight plan.”

The retail strategy fit that philosophy. Put chargers where people already spend time—grocery stores, shopping centers, busy commercial parking lots—and you solve several problems at once. Drivers get something to do while they wait. EVgo gets foot traffic, visibility, and easier adoption. And hosts get a reason to welcome chargers onto their property. In this model, the gas station of the future doesn’t look like a gas station at all. It looks like a place you were going to visit anyway.

And even in those early years, EVgo was effectively building toward the metric that matters most in charging: throughput per stall—the amount of electricity each charging stall actually dispenses. It’s the cleanest proxy for utilization and network efficiency, and it’s what ultimately turns a charger from an expensive metal box into an economic engine. Early on, throughput was naturally low. The point was to have the network in place when the curve finally bent upward.

IV. First Inflection Point: The Vision Ridge Acquisition (2016)

By 2016, the ground had shifted under NRG Energy. David Crane’s big swing to push the company toward renewables ran headlong into collapsing natural gas prices and an increasingly impatient shareholder base. In December 2015, NRG removed Crane from his duties, and the company’s Chief Operating Officer, Mauricio Gutierrez, stepped in as Chief Executive and President.

Crane later reflected that he had “tried to shift the company hard toward low to no carbon sources of generation” starting around 2008 and 2009. There were, in his words, “some successes and some failures,” but the transition proved a “very difficult challenge.” By the end of 2015, he was out.

The new regime moved fast and made the priorities obvious: focus on the core, stabilize the balance sheet, and cut anything that looked like a long-dated bet. EVgo, even with its strategic promise, was still a capital-intensive network serving a market that hadn’t fully arrived. From the inside of a turnaround, it wasn’t a moonshot. It was an expense line.

So NRG sold.

In June 2016, NRG Energy sold a majority interest in EVgo Services LLC to Vision Ridge Partners for approximately $50 million, while retaining a minority stake and certain contractual rights.

Vision Ridge—an investment firm oriented around climate action—announced it had closed its major investment in EVgo, describing it as the nation’s leading public fast-charging network. The message was clear: EVgo would operate as a more independent company now, with a mandate to expand and bring more drivers into electric vehicles nationwide.

The deal also came with real capacity to build. Vision Ridge positioned EVgo with more than $100 million of infrastructure funding to expand the network. NRG, meanwhile, stayed involved as a significant partner and continued to support the California settlement obligations that had launched EVgo in the first place.

But the transaction also revealed how early—and how uncertain—this market still was. The price, roughly $50 million for a majority stake, was a stark comedown from what had been invested to get the network off the ground. NRG valued its remaining 35% equity interest at just $1 million and recorded a $78 million loss on the sale.

To Vision Ridge, that wasn’t a warning sign. It was the entry point.

“As the nation’s leading charging network, EVgo is uniquely positioned to build the transportation infrastructure of the future,” said Reuben Munger, Managing Director of Vision Ridge. With new resources and guidance, he argued, EVgo could expand further, ease range anxiety, and help reshape how people travel.

And the strategic shift under Vision Ridge showed up quickly. EVgo stopped being framed as a compliance artifact and started being run like a growth infrastructure business—built for a market that was finally beginning to move. Tesla’s Model 3 was coming. Automakers were making electrification commitments in public. California kept tightening its zero-emission mandates. The “maybe someday” era was starting to look a little more like “soon.”

EVgo leaned hard into partnerships as a way to manufacture demand. It worked with automakers including BMW to bring fast combo charging to 24 cities. It partnered with Nissan on the “No Charge to Charge” program, offering free fast charging for customers leasing the Leaf.

It also leaned into a segment that most charging networks were only beginning to understand: rideshare and shared mobility. EVgo had already done work electrifying programs like GM’s Maven Gig, WaiveCar, and Lyft—experience that would matter later, as fleets became one of the clearest paths to higher utilization.

The Vision Ridge years, from 2016 through 2020, turned EVgo from a mandated buildout into a commercial enterprise. But the most important work in that era was easy to miss from the outside. EVgo was building a real operating engine: learning where chargers actually work, how to negotiate with utilities, how to procure and deploy equipment at scale, and how to make the customer experience feel reliable. In charging, that know-how compounds—and over time, it becomes a moat.

V. Scaling Under Private Ownership (2017-2020)

By 2018, the EV market started to feel less like a science project and more like a movement. Tesla was ramping the Model 3, and legacy automakers were no longer talking about electrification as a niche—they were putting timelines on it. The question was shifting from “will people buy EVs?” to “how fast will they buy them, and will the charging be there when they do?”

EVgo used that moment to scale what it already had: real infrastructure in real places. By this point, its footprint had grown to more than 750 sites with over 1,250 fast chargers spanning 34 states. In 2018, EVgo’s public fast-charging network powered more than 75 million electric miles, offsetting an estimated 17,000 metric tons of carbon emissions.

Then came a differentiator that was both strategic and philosophical. In 2019, EVgo became the first EV charging network in the U.S. to be powered by 100% renewable energy. This wasn’t just branding. One of the most common critiques of EVs is that they’re only as clean as the electricity behind them. EVgo’s answer was straightforward: it sourced renewable energy credits to match 100% of its network consumption. That gave the company a clean marketing message and a cleaner environmental story—at a time when trust and perception mattered almost as much as plugs and kilowatts.

That same year, EVgo leaned further into a customer segment that could actually make charging economics work: rideshare. In September 2019, Uber and EVgo announced an agreement aimed at accelerating rideshare electrification in the U.S., with EVgo positioned as a natural partner thanks to its fast-charging footprint and renewable-energy claim.

The appeal was simple. Rideshare drivers drive a lot. EVgo cited a 2019 study finding that rideshare drivers typically drive three to seven times more miles than the average EV owner, with some charging multiple times per day. For a charging network, that’s the dream: high-frequency customers who turn expensive hardware into something closer to an annuity.

But the biggest change of the era wasn’t a partnership or a sustainability pledge. It was another ownership handoff.

In December 2019, LS Power signed a definitive agreement to acquire EVgo from Vision Ridge Partners. EVgo would continue to operate as a stand-alone entity under LS Power’s umbrella. The deal was expected to close in early 2020, and financial terms weren’t disclosed.

LS Power wasn’t a sustainability-branded investor. It was an energy infrastructure machine—an owner, operator, and builder in the power world. Since 1990, it had developed, constructed, managed, or acquired more than 41,000 MW of competitive power generation and 630 miles of transmission. In other words: this was a firm fluent in permitting, interconnection, utility negotiations, and the painful realities of moving electrons across a grid.

On January 16, 2020, LS Power completed the acquisition.

That shift mattered. Vision Ridge helped turn EVgo into a growth company. LS Power had the muscle memory for infrastructure at scale—how to finance it, how to build it, and how to navigate the byzantine world of power markets and grid constraints that quietly determines whether charging sites open on time or sit stuck in limbo.

“EVgo is a well-established leader in EV charging, with an exceptional team dedicated to building, owning and operating the most extensive public fast charging network in the United States,” said David Nanus, Co-Head of Private Equity at LS Power, framing the acquisition as a platform to expand EVgo’s footprint and invest into the next phase of growth.

And then, almost immediately, the world slammed the brakes.

Within weeks of the deal closing, COVID-19 began shutting down travel and collapsing vehicle miles driven. In 2020, the drop in driving pushed EVgo’s revenue down 17% and network throughput down 39%.

It was the kind of shock that could have suffocated a capital-intensive network at exactly the wrong moment. But it also clarified what EVgo now had: a new parent with deep pockets, long time horizons, and a core competency in keeping infrastructure alive through volatility.

That combination—hard-earned operational experience, a growing footprint, and an infrastructure-native owner—set EVgo up for the next wave. Because after COVID came the public-market frenzy. And in the EV world, that meant one thing: SPAC season.

VI. Second Major Inflection: Going Public via SPAC (2021)

By 2021, SPACs had turned into the hottest shortcut to the public markets—and nowhere was the frenzy more intense than anything adjacent to electric vehicles. In just a matter of months, a parade of EV and EV-adjacent names went the blank-check route: Arrival, Canoo, ChargePoint, Fisker, Lordstown Motors, Proterra, and The Lion Electric Company, among others.

EVgo’s deal fit the moment. But it also had a twist that felt almost too neat.

The SPAC EVgo chose was led by David Crane—the same David Crane who, a decade earlier, had pushed NRG into clean energy, created EVgo inside the company, and then was forced out when that vision collided with shareholder patience. Now he was back, this time with a vehicle built specifically for climate-focused companies.

Crane had co-founded two climate SPACs and served as CEO. The first, Climate Change Crisis Real Impact I Acquisition Corporation, raised about $230 million and then, on January 22, announced it would merge with EVgo.

CRIS described itself plainly: a special-purpose acquisition company formed to identify and acquire a scalable business making a significant contribution to fighting the climate crisis. Its leadership bench was built to look credible at the intersection of energy, finance, and operations, with veterans from NRG, Credit Suisse, General Electric, and Green Mountain Power.

Crane’s co-founders included John Cavalier as Chief Financial Officer and Beth Comstock as Chief Commercial Officer. Cavalier had been Managing Partner at Hudson Clean Energy Partners, and before that held senior roles at Credit Suisse, including Global Chairman of the firm’s Energy Group. In 2005, he launched Credit Suisse’s first dedicated renewable energy investment banking effort.

The symmetry wasn’t lost on anyone watching: the CEO who had once championed EVgo as an internal bet—and paid a career price when that bet looked too early—was now effectively returning to finish the job by taking EVgo public.

The transaction itself combined roughly $230 million of cash from the SPAC’s trust account with $400 million from a PIPE investment (not including redemptions and fees). The business combination was unanimously approved by the SPAC’s board and then cleared at a special meeting of stockholders on June 29, 2021, with more than 99% of votes cast in favor.

The PIPE investors were the kind of names that signaled institutional conviction. “We are excited to take EVgo public,” said David Nanus, EVgo Chairman and Co-Head of Private Equity at LS Power. “We look forward to continuing to partner with Cathy and her outstanding team as they execute on the incredible growth opportunity in front of them and drive electrification of the transportation space.”

When the deal closed, Climate Change Crisis Real Impact I Acquisition Corporation changed its name to EVgo Inc. On July 2, 2021, EVgo Inc.’s Class A common stock and warrants began trading on the Nasdaq Global Select Market under the symbols “EVGO” and “EVGOW.”

And EVgo didn’t wait long to make it clear it wasn’t just building hardware. The same month, it announced the acquisition of Recargo, an e-mobility software company, for $25 million in an all-cash transaction.

Recargo’s flagship product, PlugShare, was already embedded in EV driver behavior. It had captured nearly 3 million driver reviews, and EVgo said it was seeing adoption at a startling level: about 7 unique PlugShare app installs for every 10 EVs in operation in the U.S. PlugShare’s database spanned over 52,000 public charging locations and more than 133,000 chargers covered, built from driver-contributed data and on-the-ground reporting.

For EVgo, this was strategic gold. Charging is a physical infrastructure business, but winning often comes down to software, discovery, and trust—who drivers turn to when they’re low on range and need a charger that actually works. PlugShare was widely used as the place to find stations and read real-world reviews. In effect, EVgo had bought the map—and the comment section.

Of course, buying the map raised an immediate question: would it stay neutral?

EVgo addressed that directly. “To enhance transparency, EVgo and Recargo intend to publish PlugScore calculations and methodologies, enhance algorithms and further integrate customer and network feedback to improve the utility of the score while preserving its neutrality.” And when asked whether PlugShare would still show a competing station if it was the closest option, EVgo’s Chief Commercial Officer was blunt: “Absolutely.”

VII. The Public Company Era: Growth Mode (2021-2023)

Going public didn’t just give EVgo a ticker symbol. It gave the company a bigger toolbox: access to public-market capital, a liquid acquisition currency, and a platform to sell itself as the default fast-charging partner for anyone trying to electrify at scale. From 2021 through 2023, EVgo pushed on three fronts at once: expanding the network, building software, and stacking partnerships that could drive real, repeatable utilization.

The software push mattered because it telegraphed EVgo’s real ambition: to be more than a company that owns metal boxes in parking lots. Products like EVgo Optima, EVgo Inside, EVgo Rewards, and Autocharge+ were about smoothing the experience, reducing friction at the plug, and layering in services that could differentiate the network beyond price per kilowatt-hour. In a business where hardware quickly becomes commoditized, EVgo was trying to win on the parts customers actually feel: discovery, reliability, and a checkout flow that doesn’t make you want to give up and go home.

That theme showed up in a very consumer-tech way at CES in January 2023, when EVgo announced a partnership with Amazon. The idea: drivers with Alexa-equipped cars could locate, schedule, and pay for charging using Alexa, with a roll-out planned later in 2023. It was a small glimpse of where charging was headed—less like a transaction at a pump, more like something your car and your phone quietly coordinate in the background.

EVgo also kept doing the unglamorous work of building demand through programs and partnerships. Various government agencies and automakers offered discount plans on the EVgo network. Ridesharing companies like Uber and Lyft did as well. And EVgo partnered with Hertz, offering special charging rates to drivers renting EVs at Hertz locations across the country.

Fleets and rideshare, in particular, kept proving why EVgo had leaned into them early. EVgo found that the average rideshare driver charged about five times more than the average retail customer in 2023. And that usage started to show up as a meaningful share of the whole network: rideshare throughput reached 24% of total throughput in the first quarter of 2024, up from 11% in the first quarter of 2021.

That concentration is the key to EVgo’s economic story. Fast-charging networks are dominated by fixed costs: equipment, installation, rent, and the sometimes-painful realities of grid connection. Once a site is built, the incremental cost of serving the next charging session is comparatively low. So the fastest path to sustainable economics isn’t just “more stalls.” It’s more sessions per stall. High-intensity drivers—especially rideshare—help turn underutilized infrastructure into working infrastructure.

This period was also defined by leadership. Under CEO Cathy Zoi, EVgo scaled dramatically as a public company. Zoi retired as CEO and from the Board after overseeing a 957% increase in quarterly revenue since EVgo went public in 2021.

“Leading EVgo from a 50-person, private enterprise focused on a nascent EV sector to a leader in charging solutions serving nearly 700,000 customers has been a highlight of my career,” Zoi said. “I set out to build a strong business yielding robust growth in charger deployments, network utilization, and company revenues, and as a team, we have accomplished that.”

In August 2023, EVgo’s board announced a leadership transition. Badar Khan became Chief Executive Officer in November 2023. He had already been on EVgo’s board since May 2022, and he came with something EVgo increasingly needed: deep utility and infrastructure experience.

From 2017 to 2022, Khan worked at National Grid, most recently as President of National Grid USA and previously President of National Grid Ventures. During his time there, he oversaw regulatory approval for one of the largest “make ready” EV infrastructure programs for utilities in the U.S.—exactly the kind of coordination-heavy work that determines whether charging buildouts stay on schedule or get stuck in interconnection purgatory.

Before that, Khan spent 14 years at Centrica plc in the U.S. and U.K., including as CEO of Direct Energy from 2013 to 2017, where the business served more than five million customers. Under his leadership, Direct Energy grew to revenue of more than $15 billion.

Khan’s appointment signaled where EVgo was headed next: less startup storytelling, more operational scale. And that was timely, because the next phase of EVgo’s story would be defined by infrastructure measured not in dozens of sites, but in thousands of stalls—and a level of capital that only a few players in the industry would be able to access.

VIII. Third Major Inflection: The GM-Pilot-EVgo Mega-Partnership (2022-Present)

If EVgo’s early buildout was optimized for city life—retail lots, grocery runs, and the places people already parked—the Pilot partnership was something else entirely. It was EVgo stepping onto the American highway system and making a claim on the hardest problem in EV charging: long-distance travel.

In 2022, Pilot Company, General Motors, and EVgo announced a plan to build up to 2,000 fast-charging stalls at up to 500 Pilot and Flying J locations.

The idea is almost embarrassingly logical. Truck stops were built for exactly what fast charging requires: a predictable 15-to-30-minute stop, any time of day, with bathrooms, food, drinks, and a place to reset before getting back on the road. They’re already positioned at the interchanges that matter, which means you’re not asking drivers to take a detour just to refuel with electrons.

And the pitch isn’t just “we put chargers here.” It’s “we made charging feel like it belongs here.” Many sites come with the same amenities you’d expect from a modern travel center—lounges, free Wi‑Fi, upgraded restrooms, on-site restaurants, and grab-and-go options—so the charging stop feels more like a break you’d take anyway, not a chore you have to plan around.

The stations are designed for real road-trip use, too: overhead canopies at many locations, and pull-through stalls for larger vehicles and drivers towing trailers. EVgo’s high-power chargers can deliver up to 350 kW, with the headline promise of getting drivers back on the road in as little as 15 minutes. And for compatible vehicles, Plug-and-Charge means the session can start and payment can happen just by plugging in—no app fumbling, no card reader roulette.

The pace of rollout has been fast. Pilot, GM, and EVgo said the network had reached more than 200 locations across nearly 40 states, with close to 850 fast-charging stalls deployed in just over two years. The companies also said they were nearing the halfway mark toward the full build, and anticipated reaching 1,000 stalls across 40 states by the end of 2025.

What’s easy to miss in all this is what it says about EVgo’s business model in its public-company era. Much of this build is delivered through EVgo eXtend, EVgo’s white-label “charging-as-a-service” offering. EVgo builds, operates, and maintains the infrastructure, while partners like Pilot and GM bring the sites and customer demand. It’s a way to scale faster—without EVgo having to shoulder every piece of the capital burden alone.

It’s also a direct attack on one of the most stubborn gaps in U.S. charging: rural coverage. As the partners expanded the footprint from more than 25 states to nearly 40 in under a year, they emphasized that availability still lagged in the countryside—where, at the start of 2025, only 45% of rural counties had at least one fast-charging stall.

“Hitting the open road is a natural emblem of American culture, and traveling by car means drivers can set their own schedule to stop and charge when and where they want,” said EVgo CEO Badar Khan. “Our EVgo eXtend network, built in collaboration with Pilot and GM, is delivering reliable charging to communities large and small — ensuring freedom of fueling choice for every driver.”

And Pilot wasn’t the only way the GM relationship deepened. In 2024, EVgo pointed to milestones that included surpassing 2,000 GM-related stalls, alongside expanding partnerships with automakers like Toyota and retail partners including Meijer and Regency Centers.

IX. Fourth Major Inflection: The $1.25 Billion DOE Loan (2024)

If there was ever a moment that signaled EV charging had graduated from a venture bet to a national infrastructure priority, this was it: in December 2024, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office closed a $1.25 billion loan guarantee for EVgo—one of the largest federal commitments ever made to a single charging network.

The process took time. EVgo said the facility reached financial close after an 18-month run-up, and the company has already taken its first step into the funding: a $75 million initial draw.

The scale is the headline. The loan is designed to support EVgo’s deployment of roughly 7,500 new DC fast-charging stalls across the U.S. By EVgo’s plan, that buildout would bring its owned-and-operated network to at least 10,000 fast-charging stalls by 2029—more than tripling its footprint.

Under the hood, the facility includes $1.05 billion of principal and up to $193 million of capitalized interest. It’s structured with a long time horizon—a 17-year tenor—and a multi-year deployment window beginning in 2025. EVgo also contributed 1,594 existing charging stalls as collateral for the project.

This funding wasn’t just about quantity. It was also about what EVgo intends to build next. The company said it plans to roll out new charging architecture beginning in the second half of 2026, with a focus on streamlining the charging process and improving energy efficiency.

And importantly, this wasn’t a “someday” announcement. EVgo said it has already built the first new stalls financed by the loan, and that it will prioritize new sites in amenity-rich locations—places with retail, dining, shopping, and services—because that’s where charging fits most naturally into real life.

The loan’s structure also reflects the policy goals wrapped around electrification. EVgo estimates the buildout will create more than 1,000 U.S. jobs, including over 700 contracted roles spanning construction, engineering, development, and operations and maintenance.

As EVgo put it: “EVgo’s comprehensive network plan helps address the growing demand for public charging infrastructure by bringing our industry-leading fast charging solutions to more drivers than ever before. DOE’s low-cost financing enables EVgo to more than triple our network size by 2029, building our operational and financial scale and expanding our geographic footprint.”

Zooming out, this is what changes the game for EVgo. Building fast-charging stations is expensive, and the economics are unforgiving when capital is costly. With a government-backed facility like this, EVgo no longer has to rely only on equity raises or higher-cost debt to fund growth. It now has access to lower-cost financing that can make each new site pencil out—and that’s how charging stops being a land grab and starts becoming durable infrastructure.

X. The Path to Profitability: Understanding EVgo's Economics

All of that expansion—the SPAC, the partnerships, the DOE-backed buildout—eventually runs into the only question public markets really care about: can this thing make money?

EVgo has been clear about what “making money” means in its world: getting to EBITDA profitability. The company has guided to full-year 2025 revenue of $350 million to $405 million, with adjusted EBITDA ranging from a $15 million loss to a $23 million gain. In other words, 2025 is positioned as the crossover year, with EVgo expecting to reach EBITDA break-even by Q4 2025. Longer term, it has set an ambitious target of $500 million of adjusted EBITDA by 2029, with mid-30% margins.

In Q3 2025, EVgo reported total charging network revenues of $56 million, up 33%. eXtend revenue—the white-label build, own, and operate business—came in at $32 million, up 46%. Ancillary revenues were about $5 million, up 27%. The takeaway is that growth isn’t coming from a single lever; it’s coming from both EVgo’s owned network and its partner-led buildouts.

Margins have been moving the right way, too—because they have to. Charging network gross margin was 35% in the third quarter. Adjusted gross profit was $27 million, up 48% year over year. EVgo also pointed to operating leverage: adjusted G&A fell from 40% of revenue in Q3 2024 to 34% in Q3 2025. Adjusted EBITDA in the quarter was still negative, at -$5 million, but that was a $4 million improvement versus the same quarter the year before.

Behind those financials is the physical reality of scale. EVgo ended Q3 2025 with 4,590 stalls in operation—about 2.7 times more than at the end of 2021. Over that same period, the customer base grew almost fivefold. Utilization has been climbing, too: EVgo reported charger utilization reaching 24% in the first quarter, up from 9% two years earlier. That matters because, in charging, utilization is the difference between “infrastructure” and “expensive decoration.”

And the network is simply doing far more work than it used to. EVgo reported 350 gigawatt-hours of energy dispensed over the trailing twelve months—a 13-fold increase from that earlier period. Over the last twelve months, revenue reached $333 million, which EVgo said was more than 15 times higher than in 2021. It also highlighted that charging network gross margins have improved from the mid-teens to the mid-to-high 30s as the business has matured.

In 2025, EVgo also leaned into a very specific kind of operational advantage: building faster and cheaper. The company said it deployed more than 40% of its new U.S. fast-charging stations in 2025 using domestically manufactured, prefabricated charging skids. The modular approach reduced installation time and lowered average station costs by around 15%. That’s a big deal in a business where construction timelines can be the difference between hitting growth targets and missing an entire season.

A lot of that execution has been supported by EVgo’s collaboration with Miller Electric Company, launched in 2023. EVgo credits the partnership with accelerating installation timelines and reducing costs, while also supporting domestic manufacturing and local job creation.

The capital stack has evolved alongside the buildout. EVgo reported strong Q2 2025 results, including record revenue of $98 million, up 47% year over year. It also announced a $225 million commercial bank loan facility, expandable to $300 million, to fund further deployment. EVgo described the $225 million senior secured, non-recourse credit facility—with an option to increase by $75 million—as the largest commercial bank facility in the U.S. EV charging sector.

And then there’s the software layer—the part of charging that drivers actually feel. EVgo’s Autocharge+ is the company’s proof point that “fast charging” isn’t just about power output; it’s about removing friction. EVgo said it has surpassed five million Autocharge+ sessions, with more than 300,000 customer accounts enrolled over the last three years. Nearly 30% of charging sessions are now initiated using Autocharge+, and EVgo points to that seamless flow as a contributor to higher charge success rates across the network.

Put all of this together and you can see the shape of the bet. EVgo is trying to do what infrastructure companies always have to do: survive the low-utilization early years, scale into operating leverage, and cross the line where each new station isn’t just another cost—but another compounding asset.

XI. Competitive Landscape and Strategic Positioning

No matter how good EVgo gets, the U.S. fast-charging conversation starts with one name: Tesla. The Supercharger network is the incumbent advantage in this market, and every other operator is playing on a field Tesla helped define.

By the count of ports, Tesla’s lead is enormous. Federal data puts the Supercharger network at more than 33,000 fast-charging ports, with Electrify America a distant second at a little over 5,000. EVgo and ChargePoint come next, but the gap to Tesla is the story. Tesla crossed this threshold the old-fashioned way: it built early, built hard, and then kept building. It launched the first six Supercharger stations in the U.S. in 2012, all in California, years before “road-tripping an EV” felt normal.

EVgo’s positioning in that landscape is both simpler and narrower. Like Electrify America, EVgo exists because of a settlement—NRG’s, in the aftermath of the Enron-linked California energy crisis. But unlike Tesla, Blink, or ChargePoint, EVgo isn’t primarily in the business of selling charging hardware. It’s in the business of running a network: choosing sites, getting power, installing equipment, keeping uptime high, and making the experience feel consistent.

That consistency has become a quiet differentiator. EVgo tends to rely on a streamlined set of fast-charging hardware and aims for a predictable experience across locations—about as close as a non-Tesla network has come to “you know what you’re getting when you pull in.”

And it is scaling quickly. EVgo operates across 40 states and has said it aims to reach 15,000 stalls by 2029. By mid-2025, it had about 4,350 stalls in operation, with more than half of those offering 350 kW charging. The customer strategy matches the economics: EVgo has leaned into subscribers and high-utilization drivers, especially rideshare, with more than 55% of network demand coming from rideshare drivers or other subscribers.

EVgo’s broader pitch is straightforward: fast charging that works for every EV driver, not just one brand’s customers. With a little over 4,000 ports and roughly a 7% share of the U.S. fast-charging market, EVgo has carved out a meaningful position—but it’s doing it in a market where the leader still towers over everyone.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants (Moderate-High): The technology is accessible, but the real barriers are capital, permitting, interconnection, and operations. EVgo’s DOE-backed financing and automaker partnerships strengthen its position, but deep-pocketed entrants—oil majors like Shell and BP, big-box retailers like Walmart, and the continued expansion and opening of Tesla’s network—can still reshape the map.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Moderate): EVgo uses multiple equipment suppliers, which reduces dependency. Its prefabrication work with Miller Electric is a practical edge here: supply chain decisions that lower cost and speed deployment translate directly into competitiveness.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Low-Moderate): Individual drivers don’t have much leverage. Fleets and rideshare partners do, and they can negotiate pricing and programs. EVgo’s subscription and partner offerings reflect that reality: flexible pricing to attract the customers who drive the most throughput.

Threat of Substitutes (Low-Moderate): The biggest substitute is home charging. But that’s not universally available—especially for renters and multi-unit housing—so public fast charging is structurally necessary. Faster charging also reduces the time tradeoff, making public charging feel less like a compromise.

Competitive Rivalry (High): Competition is intense and getting more so: Tesla’s scale, Electrify America’s footprint, ChargePoint’s installed base, and new entrants all fight for the same scarce resources—prime locations, grid capacity, and loyal repeat users.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework:

EVgo’s advantages show up less as a single knockout punch and more as a stack of compounding edges:

Network Effects: PlugShare gives EVgo exposure to user behavior and feedback at massive scale. More charging activity creates more reviews and better data, which improves discovery and confidence for drivers.

Scale Economies: Fast charging has heavy fixed costs—software, operations, site development, grid work. As EVgo grows, those costs spread across more stalls and more sessions, showing up as operating leverage.

Counter-Positioning: EVgo’s focus on DC fast charging, rather than trying to be everything (Level 2 plus DC, hardware sales plus network operations), keeps the company specialized. That specialization can be an advantage when reliability and throughput matter most.

Switching Costs: Autocharge+, subscriptions, and rideshare programs introduce real, if moderate, switching costs. Once charging becomes automatic and habitual, drivers have less reason to experiment.

The biggest strategic risk remains the same one facing every non-Tesla network: Tesla opening Superchargers to non-Tesla vehicles. It expands the total pool of fast charging—good for EV adoption overall—but it also turns the category leader into a more direct competitor for the very drivers EVgo is trying to win.

XII. Bull and Bear Cases: Weighing the Investment

The Bull Case:

The bull case for EVgo starts with a simple premise: America is putting millions of EVs on the road, and those drivers are going to need reliable places to charge. EVgo already owns and operates real infrastructure that took years to assemble—permits, utility relationships, site hosts, equipment, operations, and the hard-earned learning curve that comes with running a network in the real world.

The Department of Energy loan guarantee changes the financing equation. Charging is a capital-heavy business, and the difference between expensive money and low-cost money often determines whether a network can scale aggressively without destroying shareholder returns. With that facility in place, EVgo has a credible shot at building out faster while keeping the cost of capital under control.

Management has also been leaning into a narrative the market wants to hear: predictable growth and a visible path to profitability. CEO Badar Khan has argued that EVgo’s revenue has grown “consistently and predictably” and even outpaced the growth in EVs on the road. He’s also pointed to the milestone that matters most internally: “We are getting closer and closer to the point where charging network gross profits exceed fixed costs.”

Then there’s the utilization engine. Retail drivers are nice, but high-frequency drivers are what make the math work. Rideshare remains one of EVgo’s clearest advantages because those drivers charge far more often than the average consumer, which helps push stations toward breakeven faster. Layer in the GM-Pilot buildout—expanded coverage with partners sharing pieces of the capital burden through EVgo eXtend—and you get a scaling story that doesn’t rely solely on EVgo funding every site entirely on its own.

And while the network is growing quarter to quarter, the biggest wave of deployment is still ahead. EVgo’s plan implies the steepest ramp comes later in the decade, with 2029 standing out as the year with the largest jump in stalls, reaching an upper target of 14,400.

The Bear Case:

The bear case is also straightforward—and it’s the one that haunts every non-Tesla charging network: competition, capital intensity, and demand risk.

Tesla’s Supercharger network is still the benchmark for scale and reliability. As Tesla opens more of that network to non-Tesla vehicles, EVgo risks fighting a stronger version of the category leader for the same charging sessions. At the same time, ChargePoint’s footprint, Electrify America’s highway presence, and new competition from oil majors and major retailers make the landscape increasingly crowded.

Even with DOE-backed financing, the business remains execution-heavy. EVgo has to deliver thousands of deployments while staying on top of construction timelines, utility interconnections, and equipment uptime—any of which can become a bottleneck. And because the assets are expensive, mistakes compound.

Finally, there’s the demand side. If EV adoption slows or turns down year over year for a stretch, charging networks feel it—especially in a model where the economics improve dramatically with higher utilization. EVgo has also seen seasonality in vehicle miles traveled and charging behavior, which can create swings in throughput per stall and, in turn, gross margins.

Key KPIs to Monitor:

For anyone tracking EVgo, two metrics matter more than almost everything else:

-

Average Daily Throughput per Stall (kWh): This is utilization—how hard each stall is working. Higher throughput doesn’t just lift revenue; it spreads fixed costs across more charging, which is how the model moves from “installed” to “profitable.”

-

Charging Network Gross Margin (%): This is the clearest measure of whether the core charging business is becoming a durable engine before corporate overhead. EVgo has shown expansion from the mid-teens to the mid-30s; continued movement higher would be a strong signal the network is maturing into real infrastructure economics.

XIII. Conclusion: The Infrastructure Bet

EVgo’s journey—from an Enron-era settlement to a Department of Energy-backed charging buildout—captures the strange way real infrastructure companies get born. What started as corporate penance turned into an accidental head start. What NRG exited at a loss later re-emerged as a public company with access to government-guaranteed capital and a mandate to scale.

Along the way, EVgo has started to rack up mainstream validation. It was named one of America’s Greatest Companies 2025 by Newsweek and Plant-A Insights Group, earning a 4.5 out of 5 star rating. And the business itself has been growing fast: EVgo reported $257 million in revenue for 2024, up 60% year over year.

But the real EVgo thesis still comes down to two words: timing and execution.

The transition to electric vehicles is happening. The argument now is about pace—and about who captures the charging sessions that matter. If EV adoption accelerates, EVgo’s early network, automaker relationships, and corridor strategy become more valuable with every year that passes. If adoption slows, or if competitors win the highest-traffic sites and the most loyal customers, EVgo is left holding a very expensive set of assets that need utilization to work.

This is why the operational details matter. EVgo has said it deployed over 40% of its 2025 stations using prefabricated, modular charging skids manufactured domestically with Miller Electric—cutting average station costs by about 15% while speeding up deployment. In a category where delays and cost overruns can quietly kill the model, “build faster and cheaper” isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the playbook.

For long-term investors, EVgo is a relatively pure bet on American public fast-charging infrastructure—with all the policy exposure, competitive pressure, and execution risk that comes with that territory. And in a way, the company’s origin story is repeating itself. The same forces of regulation and public policy that created EVgo in the first place are now showing up again through DOE financing, state incentives, and federal charging programs that help underwrite the next phase of the buildout.

Whether EVgo can scale to thousands more stalls, keep reliability high across a sprawling network, and stay competitive in a market Tesla helped define will determine how this story ends: as a durable infrastructure winner, or as another early pioneer that built ahead of demand and paid the price for being too soon.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music