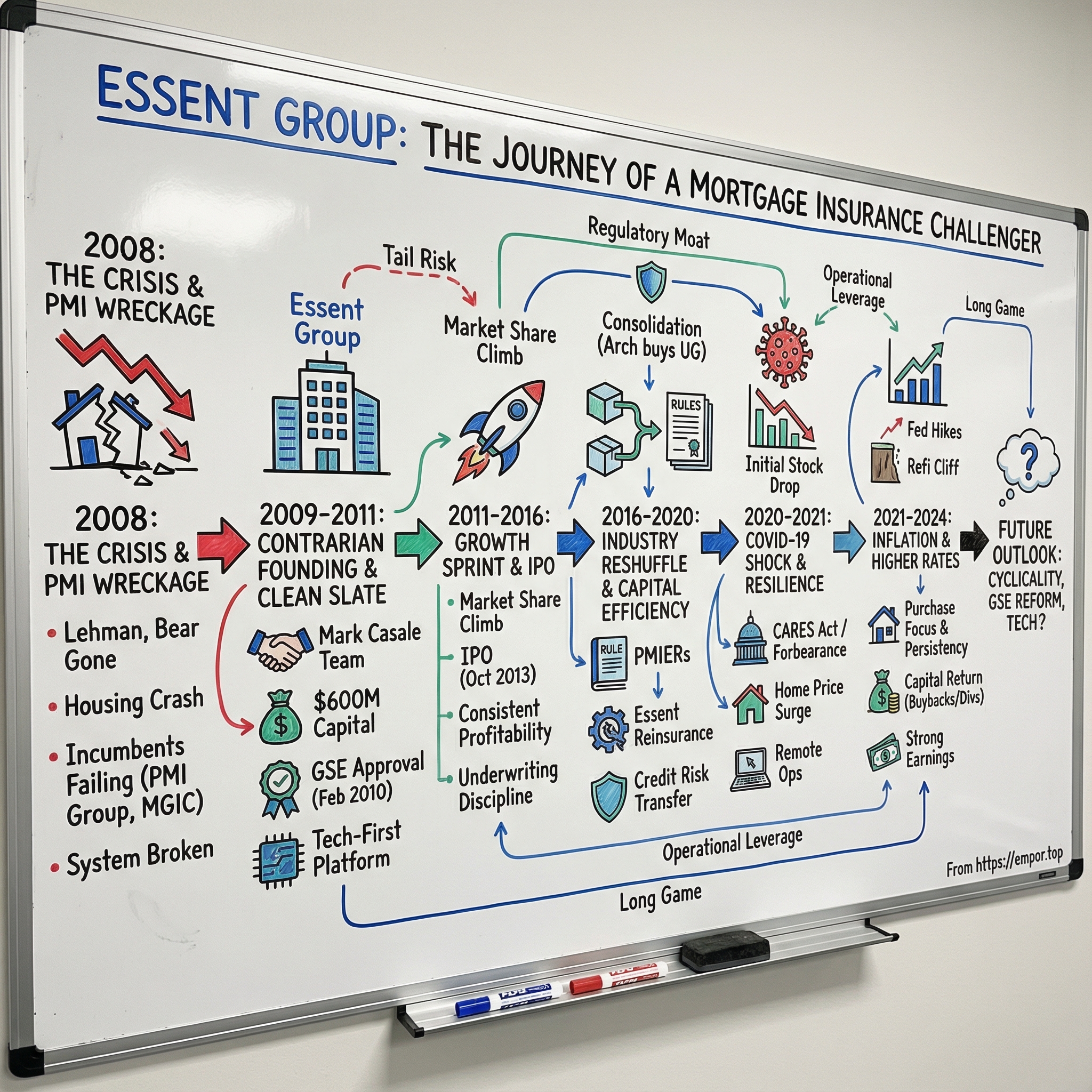

Essent Group: The Story of America's Mortgage Insurance Challenger

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture late 2009. The American financial system is still smoking.

Lehman is gone. Bear is gone. The housing market has cratered, with home prices down roughly 30% from the peak. Millions of homeowners are underwater. And the private mortgage insurance industry—the companies that are supposed to be the shock absorbers when borrowers default—isn’t absorbing anything. It’s breaking.

PMI Group, one of the oldest names in the business, is sliding toward bankruptcy. MGIC is fighting to stay standing. Radian is scrambling to plug capital holes. The whole sector looks less like an industry and more like a cleanup site.

And in the middle of that wreckage, in Philadelphia, a small group of executives walks into investor meetings with a pitch that sounds almost insane: let’s start a brand-new mortgage insurance company. Right now. In the aftermath of the crisis that just blew up everyone else.

That company is Essent Group.

Today, Essent has a market cap of over $6 billion. From its October 31, 2013 market cap of $1.75 billion, it’s grown to more than $6 billion—nearly an 11% compound annual growth rate. In full-year 2024, Essent earned $729.4 million in net income, up from $696.4 million in 2023. This is a company built from nothing, launched into the worst financial environment in a generation, and scaled into a top-tier player.

So the question is straightforward: how does a startup founded after the financial crisis become a dominant force in mortgage insurance? And the more interesting question behind it: what does Essent’s rise teach us about finding opportunity in chaos, the strategic edge of a clean balance sheet, and the weird, counterintuitive power of contrarian timing?

Because this isn’t just a story about one insurer’s financials. It’s a story about founders who saw white space where everyone else saw carnage. It’s about a regulatory moat that got deeper overnight—and the delicate dance between private capital and government-backed markets. It’s about technology in an industry that rarely gets described as “tech.” And it’s about what happens when you build a business from day one for the rules everyone else is still trying to survive.

If you care about housing affordability, the plumbing of the mortgage market, or how private companies make money inside government-adjacent systems, Essent is a case study in strategic patience.

Let’s dive in.

II. What is Mortgage Insurance & Why Does It Exist?

To understand why Essent was able to break into this industry, you first have to understand the oddly invisible product at the center of it: mortgage insurance. It’s one of those things millions of Americans pay for, month after month, without ever really being told what it’s doing.

Start with the classic homebuying rule: 20% down.

That number isn’t magic. It’s a buffer. If you put 20% down and home prices fall, there’s still enough equity in the house that the lender can usually get paid back if they have to foreclose and sell. But here’s the catch: insisting on 20% down shuts out a huge portion of otherwise creditworthy buyers. And in the United States, expanding homeownership has long been a policy goal, not just a market outcome.

That’s where private mortgage insurance, or PMI, comes in.

PMI exists to make low down payment mortgages possible in the conventional market. Companies like Essent provide credit protection to lenders and mortgage investors by covering a portion of the unpaid principal balance if a borrower defaults. In plain English: PMI is private capital that steps in to take the first hit on losses, which gives lenders the confidence—and in many cases the permission—to make more loans to more people.

The basic trade is simple. If a borrower puts down less than 20%—maybe 5% or 10%—they pay an insurance premium. In return, if the borrower defaults and the home sells for less than the balance of the mortgage, the insurer covers part of the shortfall. Pricing varies with risk, but the idea is consistent: higher credit scores and bigger down payments mean lower premiums; thinner equity and weaker credit mean higher ones. Coverage is typically only a slice of the loan, often in the range of roughly a quarter to a third of the original amount—enough to protect the lender from a meaningful portion of the loss.

This creates a three-way handshake. The borrower buys a home with less cash upfront. The lender makes a loan they might otherwise avoid, because the riskiest layer is insured. And then the most important player of all enters the picture: the secondary market.

In the U.S., two government-sponsored enterprises—Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—buy residential mortgages from lenders and guarantee mortgage-backed securities sold to investors. Their charters restrict them from purchasing or guaranteeing many low down payment loans unless those loans have specific credit protections in place. PMI is one of the primary ways conventional loans meet that requirement.

Which is why Fannie and Freddie are the kingmakers here.

A mortgage insurer without GSE approval doesn’t have a business. Full stop. The GSEs dictate eligibility standards—capital requirements, underwriting expectations, reporting, oversight—and insurers either comply or they’re locked out of the market that matters.

That makes PMI a private industry that operates, in a very real sense, at the pleasure of quasi-government institutions.

Zoom out, and you can see the ecosystem split into two lanes. There’s FHA insurance, provided by the Federal Housing Administration, which often serves borrowers with lower credit profiles or those who can’t qualify for conventional financing. And then there’s private MI, offered by companies like Essent, MGIC, and Radian, covering conventional conforming loans that Fannie and Freddie will buy.

The business model looks straightforward from a distance, but it’s full of sharp edges up close. Premiums come in steadily over time, and policies can stay on the books for years. Claims, by contrast, are infrequent—until they’re not. When downturns hit, losses can spike fast, and they can be brutal. So the whole game is underwriting discipline: choosing risk carefully, pricing it correctly, and holding enough capital and reserves to survive the ugly years.

It’s also a scale business. You need deep actuarial talent, serious compliance infrastructure, and increasingly sophisticated technology. Those fixed costs don’t shrink just because volumes are down. The larger players can spread them across bigger portfolios and build stronger data advantages over time.

Mortgage insurance, in its modern form, grew out of the Great Depression era: the FHA was created in 1934 to stabilize housing finance, and private mortgage insurance emerged later as a way for private capital to complement government programs. By the 2000s, private MI had become a core pillar of the U.S. housing machine—until 2008 exposed how fragile that machine could be.

Keep that structure in mind, because it’s the backdrop for Essent’s entire strategy: a concentrated industry, dominated by a handful of firms, where government-adjacent gatekeepers control access, and where the economics can look wonderful in calm periods—and catastrophic in a real housing downturn. Essent would be built with that reality front and center.

III. The Old Guard & The 2008 Crisis Collapse

To appreciate Essent’s origin story, you have to feel the wreckage they were walking into.

By 2007, private mortgage insurance in America looked like a settled, mature business—an oligopoly run by a familiar cast. MGIC, founded in 1957, was the old lion that had helped invent modern PMI. PMI Group was another heavyweight, publicly traded and confident. Radian was firmly in the mix. Genworth had a major MI business. United Guaranty (owned by AIG) was a staple. And Triad Guaranty rounded out the list. These were not amateurs. They’d lived through recessions. They believed they understood mortgage risk.

They were wrong in the way that matters most: they were wrong all at once.

The bubble years created a perfect machine for manufacturing bad incentives. Originators got paid for volume, not quality, so they pushed loans through as fast as they could. Wall Street packaged those mortgages into securities and fed them to investors desperate for yield. Rating agencies stamped huge chunks of the stack with AAA. Borrowers stretched, gambled, and sometimes lied—often assuming home prices would keep climbing and bail everyone out.

And mortgage insurers, the supposed gatekeepers, were swept into the same current. They wrote policies on loans that never should have existed.

The era’s greatest hits now read like a parody: no-documentation loans where income didn’t need to be proven; option ARMs where borrowers could pay less than the interest due and watch the balance grow; “stated income” deals where anyone with a pulse could claim a six-figure salary. Mortgage insurers were meant to slow this down—decline to insure the worst loans. Instead, competition turned discipline into a luxury. If MGIC wouldn’t insure it, PMI Group would. If PMI wouldn’t, someone else might.

Then the music stopped.

Once home prices peaked in 2006 and started falling, defaults rolled through the system in waves—subprime first, then Alt-A, then borrowers who looked “prime” on paper but were sitting on underwater loans with unstable structures. For mortgage insurers, it was the nightmare scenario: claims spiking just as their investment portfolios—often loaded with mortgage-linked assets—were getting pummeled.

The casualties piled up. Incumbent mortgage insurers took massive losses, burned through capital, and strained relationships with lenders. Since 2007, three private mortgage insurers stopped writing new business.

PMI Group, which had been particularly aggressive in the boom, was hit the hardest. By 2011 it was insolvent and placed into rehabilitation by Arizona regulators—the first major mortgage insurer failure since the Great Depression. Triad Guaranty stopped writing new business in 2008 and ultimately ran off its remaining portfolio through bankruptcy. MGIC and Radian survived, but only by doing whatever it took: tightening standards, raising capital on painful terms, and grinding through years defined by huge losses.

Regulators and the GSEs didn’t just respond—they rewrote the rules of the game. State regulators tightened capital requirements. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, now in federal conservatorship themselves, overhauled what it meant to be an approved mortgage insurer. Those evolving standards later became PMIERs, the Private Mortgage Insurer Eligibility Requirements, and the message was unmistakable: if you want access to the conventional market, you need more capital, better risk management, and underwriting built to survive a real downturn.

At the same time, the federal government expanded its role dramatically to keep housing finance moving—most visibly through the FHA—then began signaling that private capital needed to return as the market healed. The system didn’t just want mortgage insurance; it needed it. Banks relied on MI to sell low-down-payment loans into the GSE pipeline. But the existing private insurers were trapped: they were bleeding from old books of business while trying to re-earn trust under tougher rules.

That contradiction created a strange vacuum. Demand for private mortgage insurance was there. Supply—credible, well-capitalized supply—wasn’t.

So the question hanging over the industry wasn’t whether there was opportunity. It was who could possibly take it. Who would be crazy enough—or clear-eyed enough—to launch a mortgage insurer right after the mortgage insurance industry had almost killed itself?

That’s the opening Essent stepped into. And it set the stage for one of the most contrarian bets in modern financial services.

IV. The Founding Story: Contrarian Bet (2009-2011)

In the wreckage of the financial crisis—when the housing market was still sliding and mortgage insurers were failing—one team looked at the damage and saw an opening.

At the center was Mark A. Casale, Essent’s founder and now its CEO and Chairman. Casale had spent more than 25 years in financial services, with senior roles across mortgage banking, mortgage insurance, bond insurance, and capital markets. Immediately before Essent, he ran Radian’s mortgage insurance business as Executive Vice President and served as President of Radian Guaranty. He wasn’t an outsider taking a flyer on a “disrupted” industry. He was an insider who had watched the system break in real time.

And he took away a simple, powerful lesson: the incumbents weren’t just wounded. They were chained to legacy portfolios written during the bubble years. Meanwhile, the underlying need for mortgage insurance—helping lenders and the GSEs support low down payment lending—wasn’t going anywhere.

Most founders hunt for tailwinds. Casale went looking for a storm.

Launching a capital-intensive financial guarantor in the worst recession since the Great Depression was almost deliberately perverse. This wasn’t software. You couldn’t iterate your way to product-market fit. You had to raise real money, meet strict regulatory and GSE standards, and convince the market you deserved trust—at the exact moment trust in anything mortgage-related had evaporated.

The pitch to investors was straightforward, and that was part of its power: mortgage insurance would survive, because the system needed it. The government’s expanded role—especially through the FHA—was a crisis response, not a forever solution. The remaining private insurers were constrained by past losses. And a new entrant, built for the post-crisis world, would have structural advantages: a clean balance sheet, tighter underwriting, and modern systems designed around the new rules rather than retrofitted to meet them.

Essent’s backers reflected that thesis. The company was supported by a management team that wanted to build a new mortgage insurer funded by private capital and unburdened by legacy exposures. A deep bench of strategic and financial investors committed roughly $600 million to get it off the ground, including affiliates of Pine Brook Road Partners, The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc., an affiliate of Global Atlantic Financial Group, Valorina LLC (majority owned by an entity managed by Soros Fund Management LLC), Aldermanbury Investments Limited, an affiliate of J.P. Morgan, an affiliate of PartnerRe Principal Finance Inc., RenaissanceRe Ventures Ltd., funds or accounts managed by Wellington Management Company, LLP, and affiliates of HSBC.

This wasn’t venture capital spraying bets. It was institutions—and reinsurance specialists—making a calculated wager on how the industry would rebuild. They believed a clean-sheet insurer, born under tougher standards, could earn credibility faster than older rivals could repair theirs.

The initial funding came quickly by post-crisis standards. Essent raised a $500 million private equity round on May 27, 2009—less than a year after Lehman collapsed, when fear still dominated markets. In July 2010, it secured another $100 million of commitments from new and existing investors, bringing total equity commitments to $600 million.

With capital committed, the team moved fast, but not recklessly. In December 2009, Essent acquired a mortgage insurance platform from a former industry participant—an important step toward being operational without starting from absolute zero. Then came the true gate: GSE approval. In February 2010, Essent became the first mortgage insurer approved by the GSEs since 1995. In this business, that’s not a milestone. That’s the key to the front door.

Casale also built a team that matched the ambition of the moment. Vijay Bhasin joined in 2009 as Chief Risk Officer, bringing deep mortgage finance experience. He had been a managing director at Countrywide Financial Corporation/Bank of America, responsible for capital assessment and credit risk measurement, and earlier held roles at Freddie Mac, including vice president for credit and prepayment modeling, along with research positions at Fannie Mae and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Essent wasn’t learning mortgage risk on the fly. It was staffed by people who had spent their careers measuring it.

Building a mortgage insurer is as much about legitimacy as it is about operations. Casale led Essent through the practical gauntlet: securing private equity support, purchasing and implementing an operating platform, becoming licensed in all 50 states, and earning approval from government-linked gatekeepers who had just watched the last generation of insurers nearly implode.

From the beginning, Casale framed Essent as a long-term business. He emphasized two priorities: customers and the company itself. The approach was consultative—helping bank and mortgage customers succeed, not just quoting a price. Casale regularly met lenders in person, including prospects, leaning into a simple truth in a relationship-driven market: people do business with people they know.

Internally, the mindset was patience and discipline. Mortgage insurance carries tail risk; the decisions you make today can take years to fully show their quality. So the goal wasn’t short-term optics. It was to build the drivers of sustainable performance—strong counterparties, careful underwriting, and a platform that could hold up through a cycle.

By December 2010, Essent wrote its first mortgage insurance policies. What sounded like an impossible pitch in 2009—a brand-new mortgage insurer, launched after the industry had just detonated—was now a functioning business. And it was stepping into a post-crisis market that badly needed exactly what it had been built to provide.

V. The Growth Sprint: 2011-2016

With its first policies on the books in late 2010, Essent hit the market at a moment that almost never happens in financial services: the demand was there, but the supply of credible competitors was broken.

The incumbents were still reeling. MGIC was swallowing billions in losses from the pre-crisis book. Radian was under similar pressure. PMI Group, once a heavyweight, would file for bankruptcy in 2011. These companies weren’t in growth mode. They were in survival mode—trying to preserve capital, appease regulators, and stop the bleeding.

At the same time, the FHA’s footprint had exploded. Government insurance was carrying a huge share of insured mortgages, because there simply weren’t enough healthy private insurers to do the job. But policymakers were explicit: long-term, housing finance couldn’t be a one-way bet on the government. Private capital needed to come back.

Essent wasn’t the only one that saw that opening. New competition arrived too. National MI launched in 2013. Arch Capital acquired CMG Mortgage Insurance, bringing a formidable reinsurance-backed balance sheet into the fight. The industry was reshuffling in real time, and Essent had a narrow window to establish itself before the old guard regained its footing and the new entrants scaled up.

Essent’s playbook came down to three things: technology, speed, and service. On paper, that can sound like boilerplate. In practice, it was the difference between being a vendor and being a partner.

Remember that platform Essent bought in 2009? It wasn’t just a box to check. It gave them a functioning, scalable foundation that they kept improving—making it easier for lenders to work with them. Essent leaned into the idea of being “the mortgage insurer that acts like a tech company,” building the digital rails lenders actually cared about: automated underwriting, integrations into lender systems, and turnaround times that beat competitors still stuck on older processes.

They staffed up quickly enough to support the ambition, too—growing from 157 employees at the end of 2011 to 259 by June 30, 2013. And distribution came together fast. By June 30, 2013, Essent had master policy relationships with about 800 customers, including 21 of the 25 largest mortgage originators in the U.S. in the first quarter of 2013. Essent believed those customers accounted for nearly 70% of annual new insurance written in the private MI market.

That concentration is the whole game. Mortgage insurance isn’t sold to consumers; it’s sold to lenders. Win the top originators and you win the market. Essent went after those relationships relentlessly, and Casale made it personal—often showing up himself to meet current and prospective customers. In a business built on trust, an in-person pitch from the CEO wasn’t a nice-to-have. It was a signal: we’re serious, we’re here, and we’re going to be around.

The result was a market share climb that almost doesn’t look real if you’re used to how slow financial services usually moves. From a standing start in 2010, Essent reached roughly 15% of new insurance written within five years. In an industry where incumbents had decades of relationships, that was close to unprecedented.

Then came the moment that turned Essent from “fast-growing newcomer” into “permanent fixture”: the IPO on October 31, 2013. The public markets gave Essent growth capital, broadened its investor base, and—just as importantly—sent a message to lenders and counterparties that this wasn’t a temporary post-crisis experiment. Going public made Essent feel durable.

Profitability followed sooner than many skeptics expected. Insurance companies often spend their early years building reserves while losses catch up with them. Essent had a different starting point: a clean, post-crisis portfolio underwritten to tougher standards. Losses came in well below what the industry had been conditioned to fear. The company moved into consistent profitability and kept going.

Internally, Casale pushed a culture of performance and long-term thinking. He wanted teams focused on working with strong mortgage-banking counterparties—because these relationships aren’t one-off transactions. They’re long-duration contracts with real tail risk. The message was simple: underwriting discipline and customer quality matter as much as growth.

By 2016, the bet had clearly worked. Essent had gone from a contrarian startup to a legitimate force in mortgage insurance, proving that a clean balance sheet, modern systems, and disciplined underwriting could take share in one of the most regulated corners of finance. The next question was the harder one: could Essent hold what it had won—and turn momentum into enduring leadership?

VI. The PMI Ecosystem Reshuffles (2016-2020)

By the back half of the 2010s, mortgage insurance stopped looking like a post-crisis recovery story and started looking like a reshuffle for the next era. Three forces drove it: consolidation, regulation, and a new kind of competitor—one with reinsurance and capital markets muscle.

The headline move came in 2016, when Arch Capital Group bought United Guaranty from AIG for about $3.4 billion. United Guaranty was a major player, and the deal didn’t just change ownership. It pulled deep-pocketed reinsurance capital directly into the fight. Arch already had a foothold through its CMG subsidiary; with United Guaranty, it now had real scale and real firepower.

Paradoxically, fewer players meant sharper competition. The industry tightened into an oligopoly: MGIC as the legacy leader; Essent as the insurgent challenger; Radian and Genworth’s Enact as the established incumbents; and Arch/United Guaranty plus National MI as the newer entrants backed by alternative capital.

And MGIC, in particular, refused to play the role of wounded incumbent. After nearly collapsing during the crisis, it restructured, raised capital, and worked down its legacy book. By the late 2010s, MGIC had stabilized and started reasserting itself. At the top of the market, it increasingly felt like a two-horse race: MGIC and Essent, trading blows for share.

While the competitive field was tightening, the rulebook was hardening. The Federal Housing Finance Agency, the regulator overseeing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, finalized PMIERs—the Private Mortgage Insurer Eligibility Requirements—in 2015, then phased implementation through 2017. PMIERs formalized what the crisis had already taught everyone: if you want to insure GSE-eligible loans, you need rigorous capital, high-quality assets, and operations that can withstand real stress.

That also clarified Essent’s core risks: changes to Fannie and Freddie (through legislation, restructuring, or shifts in business practices), the ongoing requirement to meet GSE eligibility standards, and the concentration reality of the business—heavy competition for lenders, and the pain that comes with losing a major customer.

For Essent, though, PMIERs were both constraint and advantage. The company had been designed for the post-crisis world from day one. Its capital structure, risk framework, and operating processes were built with higher standards in mind. The older players had to retrofit. Essent was purpose-built.

That set up the next battlefield: capital efficiency. PMIERs made risk-based capital the scarce resource, and every insurer started looking for ways to do more business without tying up more capital than necessary. Essent pushed hard here.

It built a Bermuda reinsurance structure through Essent Reinsurance Ltd., designed to manage capital more efficiently across the organization. It also became an active user of insurance-linked notes, transferring mortgage risk to capital markets investors. In effect, credit risk transfer helped shift the industry from “buy and hold” to “buy, manage, and distribute.” By 2021 Q2, Essent said it had about 85% of its portfolio hedged via credit risk transfer. The payoff wasn’t just financial engineering; it was resilience. When risk is shared and capital is managed more efficiently, insurers can keep writing business through cycles—and remain credible counterparties to lenders and the GSEs.

By the end of the decade, the scoreboard was hard to argue with. Essent had become the clear #2 player behind MGIC. Founded in 2008 under Casale and initially backed with $500 million of equity funding, Essent Group Ltd. had grown to manage roughly $240 billion of insurance in force. Under Casale’s leadership, it became a leading mortgage insurer and reinsurer, positioning itself as a strong counterparty to lenders and the GSEs, and enabling more than three million borrowers to become successful homeowners.

It also made early, cautious steps toward international diversification. Through Essent Reinsurance Ltd., it took on mortgage risk from other markets—small in scale, but potentially useful experience if U.S. growth ever tightened.

By the time 2019 ended, Essent had pulled off the thing that sounded absurd back in 2009: a startup, founded in the wreckage, had become a pillar of the U.S. housing finance system. But the market still hadn’t delivered the one test no one could fully simulate—the kind of shock that forces every assumption into the open.

That test arrived next.

VII. COVID-19 Shock & Resilience (2020-2021)

In March 2020, COVID-19 slammed the brakes on the global economy—and financial markets delivered what felt like a speedrun of every crisis playbook at once. For mortgage insurers, it instantly raised the only question that mattered: is this 2008 again?

If unemployment exploded, would defaults follow? If home prices fell, would the thin equity on low-down-payment loans vanish overnight? Mortgage insurance is built to take the first hit, so when the world starts talking about mass job loss, the market doesn’t wait around for the claims to arrive.

Essent got punished accordingly. After trading above $50 in February 2020, the stock plunged into the low $20s by March 23—down more than half in a matter of weeks. Investors weren’t just fearing a recession. They were pricing in a wipeout.

Then came the twist.

Washington moved with a speed and scale that simply didn’t exist in 2008. The CARES Act delivered broad household support—enhanced unemployment benefits, stimulus checks, and, most consequential for mortgage credit, forbearance programs that let borrowers pause payments without being shoved into default. The Federal Reserve cut rates to near zero and restarted quantitative easing.

That policy response rewired the outcomes. Instead of a foreclosure wave, millions of borrowers got time. Instead of missed paychecks turning into immediate delinquencies, government support helped bridge the gap. And the biggest assumption—falling home prices—never showed up.

Home prices surged.

Remote work changed where people wanted to live. Buyers flooded toward more space and different geographies. Supply was already tight before COVID, then construction slowed further. With mortgage rates at historic lows, demand caught fire. The result was a housing boom that looked, from the outside, like the mid-2000s—except it wasn’t being driven by toxic underwriting and leverage. It was being driven by cheap money, constrained supply, and a sudden reshaping of consumer preferences.

For mortgage insurers, rising home prices are an almost unfair advantage. More equity means borrowers are less likely to default, and even when they do, losses are smaller because the home can be sold for more. A buyer who put 5% down in 2019 could, by 2021, be sitting on a very different equity position—and a very different risk profile.

Essent’s operating response mattered too. The company didn’t have to invent crisis workflows on the fly. Its platform supported the shift to remote work. Its capital position meant it wasn’t racing for emergency funding. And its post-crisis underwriting discipline—tight standards, no legacy bubble book—meant the portfolio going into the pandemic was built for stress.

The feared spike in losses never arrived at scale. Forbearance did what it was designed to do: bridge households through disruption. Home price appreciation kept widening the equity cushion underneath the book. Profitability remained strong, and the company’s performance stayed durable well beyond the initial shock.

The market noticed. From the March 2020 lows, Essent shares climbed back into the $50s by 2021, effectively doubling off the bottom. Investors weren’t just buying the rebound; they were repricing the core narrative. COVID wasn’t a housing-led collapse. It was a shock met by extraordinary policy support and, counterintuitively, a strengthening housing market.

The episode left Essent with a few hard-earned lessons. First, in mortgage insurance, the loss curve isn’t determined by borrower behavior alone—government policy can reshape it overnight. Second, conservative underwriting and real capital buffers aren’t theoretical virtues; they change what you can survive without blinking. Third, technology isn’t only a growth tool. In a crisis, it’s operational continuity.

And the company’s credit risk transfer program played the role it was built for. By sharing exposure with reinsurers and capital markets investors, Essent reduced peak downside. In 2020, that wasn’t just “capital efficiency.” It was an extra layer of shock absorption when the world was stress-testing everything at once.

By the end of 2021, Essent had come through the ultimate surprise exam stronger than it entered. The model had held, the market had healed, and housing looked like a tailwind.

But the next test wouldn’t come from collapsing demand. It would come from something far trickier: inflation—and the sharp rise in interest rates that followed.

VIII. The Housing Market Inflation Era (2021-2024)

The post-COVID housing boom handed mortgage insurers a strange kind of victory. On the one hand, soaring home prices were exactly what you want if you already have a book of insured loans. More home value means more borrower equity, fewer defaults, and smaller losses when something does go wrong. On the other hand, those same prices were quietly making it harder for new buyers to get in the door.

Through 2021, housing stayed on fire. Millennial buyers who’d delayed starting families and buying homes showed up all at once. Remote work reshuffled where people wanted to live. And supply was still tight—years of underbuilding, plus COVID-era construction delays—so every listing turned into a bidding war. In many markets, prices were rising at a pace that would’ve sounded impossible a few years earlier.

Then inflation arrived, and it changed the plot.

Consumer prices jumped in 2021 and 2022, and the Federal Reserve eventually responded with the most aggressive rate-hiking cycle in decades. The fed funds rate moved from near zero in early 2022 to over 5% by mid-2023. Mortgage rates rose with it, ripping from roughly 3% to over 7%.

If you want to freeze a mortgage market, that’s how you do it.

The first casualty was refinancing. The low-rate era had created a refi machine; suddenly it was gone. Nobody trades a 3% mortgage for a 7% mortgage. That “refi cliff” hit every volume-driven corner of housing finance, including private mortgage insurance. New insurance written didn’t disappear, but it shrank sharply as overall origination volume fell.

Industry-wide, private mortgage insurer volume rebounded in 2024, rising 5% compared with 2023, helped by a stronger fourth quarter. The first half of the year lagged the prior year, but the back half improved—third quarter volume was up 5%, and fourth quarter jumped 33%. Even with that improvement, new insurance written across the industry was still about half of the record levels reached in 2020, when totals topped $600 billion.

Essent’s play during this stretch was pragmatic: focus on what it could control. Purchase mortgages held up better than refinancing, so the company leaned harder into share on purchase transactions. It developed rate lock products, stayed disciplined on pricing, and resisted the temptation to chase volume just to keep the top line looking good.

And here’s the counterintuitive part: high rates helped in a different way. Persistency—how long insurance stays in force—improved. When rates are low, borrowers refinance frequently and mortgage insurance policies roll off. When rates are high, borrowers stay put, and the policies keep earning premiums. So even as new business slowed, the existing book stuck around longer, producing steady income.

You can see it in Essent’s operating stats. For full-year 2024, Essent wrote $45.6 billion of new insurance, slightly down from $47.7 billion in 2023. Fourth quarter 2024 new insurance written was $12.2 billion, compared with $12.5 billion in third quarter 2024 and $8.8 billion in fourth quarter 2023. Insurance in force stayed remarkably stable: $243.6 billion as of December 31, 2024, versus $239.1 billion a year earlier.

Competition stayed tight. MGIC remained the market leader, and market share moved around quarter to quarter as lenders shifted mix and pricing. MGIC’s underwriting unit wrote $16.4 billion of new insurance in Q2 2025, up from $10.2 billion in Q1. Essent held its ground as a leading challenger, even as the gap between players fluctuated with the market.

With fewer obvious ways to grow quickly in a high-rate environment, capital returns moved from “nice-to-have” to central strategy. In the fourth quarter of 2024 and January 2025, Essent repurchased over 2 million shares for about $118 million. In February 2025, the board approved a $500 million share repurchase authorization running through the end of 2026. Alongside a higher dividend, it was a clear message: the company believed its cash flows were durable enough to return more capital while still keeping the balance sheet strong.

By 2024, the financial results reflected that stability. Essent reported $1.24 billion in revenue, up 12% from $1.11 billion the year before. Net income rose to $729.4 million, up about 5%. The housing market was still constrained by affordability, but the takeaway for the industry—and for Essent—was bigger than any single year’s growth rate: private mortgage insurance could stay profitable through a cycle that looked nothing like 2008.

And that was the point. The 2022 to 2024 stretch didn’t prove Essent could thrive in a boom. It proved the company could keep compounding in a grind—when volumes are down, headlines are bleak, and the easy growth is gone.

IX. The Business Model Deep Dive

To really understand Essent, you have to get past the label “mortgage insurer” and look at the machine underneath: how premiums come in, how risk gets priced, what happens when loans go bad, and how capital gets stretched.

Revenue starts with premiums on insured mortgages. And those premiums come in two main forms. The first is borrower-paid monthly insurance (BPMI), where the homeowner pays the premium as part of the monthly mortgage payment. It’s steady, recurring income, and it tends to persist as long as the loan stays in place. The second is lender-paid single premium (LPSI), where the lender pays upfront and usually bakes the cost into the loan’s interest rate. That delivers cash immediately, but there’s no monthly stream afterward. Same core product, very different revenue timing.

Essent also sells a broader menu around those basics—Borrower-Paid Mortgage Insurance, Lender-Paid Single, Borrower-Paid Single, Lender-Paid Monthly, and Split Premium. The mix matters. It changes not just when revenue shows up, but how long policies stay on the books and how sensitive the business is to refinancing cycles.

The heart of the whole operation is underwriting: deciding which loans to insure and what price to charge. Essent evaluates risk using automated underwriting that looks at credit scores, loan-to-value ratios, debt-to-income ratios, property types, and geographic factors. Over time, Casale has continued pushing the franchise toward more risk-based pricing, with AI-driven analytics supporting the goal of growing shareholder value while promoting affordable and sustainable homeownership.

This is where Essent’s tech orientation shows up in a very practical way. Its proprietary pricing engine, EssentEDGE, lets lenders see Essent’s mortgage insurance pricing in real time as they build the loan. That’s not just convenience. It’s how you price more precisely—charging more where the risk is higher, staying competitive where the risk is lower, and making sure underwriting discipline doesn’t slow down the lender’s workflow.

Then there’s the moment everyone thinks defines insurance: claims. But for Essent, claims aren’t meant to be a mechanical payout. When borrowers default, the company works with loan servicers on loss mitigation—loan modifications, forbearance arrangements, deed-in-lieu transactions—anything that can reduce the size of the loss. The objective is to manage claim severity, not just claim frequency. And it’s exactly why Casale talks so much about tail risk: a policy written today might not reveal its true quality for five or ten years, and the outcome depends partly on how well the resolution process is handled.

Like any insurer, Essent also runs a second business alongside underwriting: investing the float. Premiums come in long before most claims get paid, and that pool of cash generates investment income. In 2024, net investment income grew 19% to $222.1 million. The strategy emphasizes high-quality, liquid securities—primarily investment-grade bonds. It’s the same basic dynamic Buffett points to with companies like GEICO: underwriting is the engine, but float turns time into another source of returns.

Technology also shows up as a retention tool. Platforms like EssentIQ and EssentEngage create day-to-day integration touchpoints with lenders. In a B2B market, that kind of workflow embedding can become real switching costs: not because a lender can’t move volume elsewhere, but because it’s annoying, risky, and operationally expensive to rip out systems that already work.

Distribution is straightforward and intensely relationship-driven. Essent serves the originators of residential mortgage loans—regulated depository institutions, mortgage banks, credit unions, and other lenders. Volume is concentrated, because a relatively small set of big lenders drives a large share of the market. Master policy relationships can create predictable flow, but they also come with the obvious risk: losing a major customer matters.

And finally, there’s the capital game—reinsurance and risk transfer. Essent has leaned into increasingly sophisticated reinsurance, including two forward quota share transactions covering 25% of eligible policies for 2025–2026, and two excess of loss transactions covering 20% of eligible policies. The point is simple: transfer some risk to third parties, free up capital, and either redeploy it for growth or return it to shareholders.

The company also announced the closing of a $363.4 million reinsurance transaction and related mortgage insurance-linked notes. Insurance-linked notes pull capital markets investors directly into the risk-sharing stack, expanding Essent’s ability to move risk beyond traditional reinsurance.

Put it all together and the unit economics start to click. A good year means writing business at attractive premiums, seeing low defaults in the existing book, earning solid investment returns on float, and keeping expenses tight. A great year adds market share gains, falling loss provisions as credit performs, and rising investment income. The operating leverage is real: a lot of the costs are fixed, so incremental premium dollars can drop heavily to the bottom line.

That discipline shows up in Essent’s balance sheet posture too, with conservative leverage—reflected in a debt-to-equity ratio of 0.09—and strong liquidity, with a current ratio of 3.94.

X. Industry Structure & Competitive Dynamics

Private mortgage insurance looks competitive from the outside, but structurally it behaves like an oligopoly: a handful of approved players, all selling a similar product, all fighting over the same concentrated set of lender customers—under rules set by the same gatekeepers.

The players are familiar by now. MGIC has remained the clear No. 1 by market share. Behind it, Essent typically sits in the #2 or #3 spot depending on the quarter, trading places with a tight pack that includes Enact (the former Genworth MI business), Radian, Arch, and National MI. Enact has finished certain quarters ranked second.

What’s striking is how compressed the leaderboard can get. In some recent periods, the gap between the top players has been as small as a couple percentage points, though there have also been stretches where it widened to around five points. And when overall volumes soften, the whole scoreboard bunches up even more: in the first quarter compared with the prior year, a similar share of borrowers still used private MI as credit enhancement, but only one underwriter crossed $10 billion in new insurance written. Fewer big quarters mean fewer chances to pull away.

If this sounds like a market where a scrappy startup could jump in and take a swing, it isn’t. The barriers to entry are brutal. You’re looking at well over $500 million of capital just to be taken seriously—before you’ve built the actuarial talent, infrastructure, compliance, and systems you need to operate at scale. And none of that matters unless you get the one approval that counts: Fannie and Freddie. GSE approval is essential, and it can take years. The best proof is history: when Essent got approved in February 2010, it was the first mortgage insurer to clear that hurdle since 1995. A fifteen-year gap tells you how rarely new entrants make it through the front door.

Then there’s the customer dynamic, which is where the real knife fight happens. Mortgage insurance is sold to lenders, not consumers, and origination volume is heavily concentrated among the largest lenders. Lose a major relationship and market share can move fast. That concentration also gives big lenders negotiating leverage on pricing and terms, because they can shift flow across insurers with a phone call and a pricing sheet.

Private MI also competes with a substitute that isn’t just another company—it’s the U.S. government. FHA insurance is always in the mix, and the borrower’s choice between FHA and private MI depends on credit profile, loan size, and how the premium economics pencil out. When FHA pricing is attractive, private insurers feel it in share. Put simply: a rising share of loans insured through federal mortgage insurance programs is a real risk factor for the private players.

All of this sits on top of a business that is inherently cyclical. Mortgage insurance volume surges in hot housing markets and falls hard when rates spike or a recession hits. The survivors are the ones that treat good years as the time to build capital, not the time to relax standards. That sounds obvious now, but it’s a lesson the industry had to learn the painful way.

Which brings us to pricing. Analysts have noted that MI management teams across the industry continue to describe pricing as balanced and constructive, and that higher macro uncertainty hasn’t meaningfully changed pricing dynamics so far. The oligopoly structure helps: if one player tries to buy share with aggressive rate cuts, everyone else can respond, and the whole industry’s profitability gets dragged down. Discipline isn’t perfect—there have been periods of irrational competition—but the incentives generally push toward restraint.

And with six active players in a mature market, M&A is never far from the conversation. Arch buying United Guaranty proved consolidation can happen. Large reinsurers or diversified financial firms could see MI as an attractive niche, especially if they believe they can bring cheaper capital or better distribution. And the most likely targets are the subscale players—the ones that struggle to generate consistent profitability when the cycle turns.

XI. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter and Helmer are useful here because mortgage insurance is one of those businesses that can look simple from a distance—everyone sells “the same” policy—until you map the forces that actually govern who wins. This is a regulated oligopoly selling a mission-critical product to a small set of powerful buyers, under rules written by government-adjacent gatekeepers.

Porter's 5 Forces Assessment:

Threat of New Entrants: HIGH BARRIERS If you want one statistic that captures the barrier to entry, it’s this: in February 2010, Essent became the first mortgage insurer approved by the GSEs since 1995. That’s a 15-year gap. It’s not just the capital—well over $500 million to be taken seriously—it’s the time, the scrutiny, and the scale you need to make the economics work. Post-crisis, only a couple of new players made it in, and they did it with sophisticated backers and deep domain expertise. In other words: entry is possible, but it’s brutally hard, and the gate stays narrow.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW Mortgage insurers don’t rely on scarce physical inputs. Their “supplies” are capital and talent. Capital comes from broad financial markets, and reinsurance is available from multiple global providers, so no single supplier tends to control the industry. Talent matters, but it’s not cornered by one firm. Supplier leverage just isn’t the limiting factor here.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM-HIGH The buyers are lenders, and the largest lenders have real leverage. They control huge volumes and can steer flow across insurers with pricing grids and allocation decisions. That said, it isn’t costless to switch. Master policy relationships, operational processes, and technology integrations create friction, and service quality matters when loans go sideways. Most lenders also spread volume across multiple insurers, which limits how much power any single insurer has—but it also means insurers are constantly fighting to stay in the rotation.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM Private MI isn’t the only way to solve the “low down payment” problem. FHA is a direct substitute for many borrowers. There are also credit risk transfer structures and other approaches that can shift mortgage risk without traditional MI. Portfolio lending can bypass the GSE pipeline, which can reduce the need for MI altogether. And for the very largest institutions, holding more capital is a theoretical alternative. None of these substitutes has displaced PMI, but they do cap pricing power and keep the industry honest.

Competitive Rivalry: MEDIUM There are about six active players competing in a mature market, and competition for lender relationships is intense. But this isn’t a price-war business in the way airlines can be, because everyone remembers what happens when underwriting or pricing discipline breaks. The oligopoly structure helps reinforce restraint, and industry commentary has generally described pricing as “balanced and constructive.” Rivalry is real—but it’s typically managed rather than mutually destructive.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework:

1. Scale Economies: YES This business has meaningful fixed costs—technology, actuarial and risk teams, compliance infrastructure, and corporate overhead. The bigger your premium base and the larger your insured portfolio, the more efficient you become and the more credible your models get. Scale also helps diversify risk. Essent’s growth into a massive book of insurance in force is the story of those advantages compounding.

2. Network Effects: WEAK Essent benefits from integrations and data, but adding one more lender doesn’t make the product intrinsically more valuable to other lenders in the way a true platform does. There are some platform-like effects, but they’re not the core moat.

3. Counter-Positioning: HISTORICAL (FADING) Essent’s original edge was classic counter-positioning: it entered with a clean balance sheet when competitors were dragging around toxic legacy books. Being built for the post-crisis rules was a structural advantage. Over time, that edge has naturally faded as incumbents worked through their old exposures and new business came to dominate everyone’s portfolios.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE There’s some real stickiness here. Tools like EssentEDGE and platforms like EssentIQ embed into lender workflows. Master policies create relationship and process gravity. And once lender teams are trained and comfortable, switching creates operational risk. None of it is an unbreakable lock, but it raises the cost of churn and helps defend share.

5. Branding: WEAK This is lender-driven, not consumer-driven. “Brand” matters mostly as reputation: claims-paying ability, reliability, and responsiveness when things get messy. It’s less about consumer mindshare and more about whether lenders trust you as a long-term counterparty.

6. Cornered Resource: NO Essent doesn’t control a unique input that others can’t access. The team is strong and the data is valuable, but neither is exclusive in a way that permanently blocks competitors.

7. Process Power: YES Essent’s enduring advantage is operational: how it underwrites, how it prices, how it integrates, and how it runs the business under strict constraints. Casale and the team didn’t just “start a company”—they navigated licensing in all 50 states, built or acquired a functioning platform, earned GSE approval, and created a system that can scale without abandoning discipline. That accumulation of know-how, controls, and execution is hard to copy quickly, even if the product looks similar on paper.

Primary Powers: Scale Economies, Process Power, Switching Costs

Durability Assessment: Medium-high, but highly dependent on the current regulatory structure. These advantages matter most because the GSEs control access and PMIERs shapes the capital game. If those rules change materially, the competitive map can change with them.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case & Key Risks

The Bull Case:

Housing supply shortage drives long-term origination growth. The U.S. has underbuilt housing for more than a decade, and the National Association of Realtors estimates the country is short millions of homes. As millennials and Gen Z form households, demand should stay structurally strong. If supply gradually catches up, that doesn’t kill the opportunity for mortgage insurers—it can actually extend it, by supporting years of steady purchase activity.

Market share gains remain achievable. Essent has already taken meaningful share, but there may still be room to keep winning business from weaker competitors, especially as the industry continues to consolidate. And in a business built on trust, credit ratings matter. Moody’s upgraded Essent Guaranty’s rating to A2 from A3, a signal that can strengthen Essent’s hand versus lower-rated rivals when lenders decide where to send flow.

Operating leverage drives margin expansion. Mortgage insurance has a classic scaling curve: once the platform is built and the book is large, incremental premiums can be very profitable. Essent’s book value per share rose 11% to $63.36, helped by net investment income rising roughly 20% to $222 million. If costs stay relatively stable while the book compounds, margins can expand even without heroic growth.

Capital return story demonstrates confidence. Essent has leaned harder into buybacks and dividends, signaling management’s belief in the durability of the cash flows and, at times, the attractiveness of the stock. Year-to-date, the company repurchased 6.8 million shares for $387 million, with $260 million remaining in the buyback program.

Regulatory moat protects incumbents. This is one of those rare industries where the gate is not rhetorical. GSE approval requirements and PMIERs capital standards create real barriers to entry and tend to protect established players from new competition showing up out of nowhere.

Credit performance validates underwriting. The portfolio was built under post-crisis standards, and it has now lived through multiple stress events without producing the kind of losses the market used to assume were inevitable. As Casale put it, “given the embedded equity in the portfolio… it’s probably on a lower probability side… from a credit standpoint… we feel pretty good from that first loss perspective.”

The Bear Case:

Cyclicality remains the core risk. Mortgage insurance will always be tied to the housing cycle. Another severe downturn may not look likely from today’s vantage point, but the industry’s history makes the underlying point uncomfortable: the question is always when, not if.

GSE policy risk looms. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have been in conservatorship since 2008, and there’s still no clear endgame. Any change—privatization, restructuring, or even a shift in business practices—could reshape what kinds of loans the GSEs buy and what credit enhancement they require. Changes in or to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, whether through federal legislation, restructurings, or a shift in business practices, remain a real risk factor.

FHA competition expands government share. If policymakers respond to affordability pressures by expanding FHA’s role or making it more attractive relative to private MI, private insurers could lose share to government insurance.

Interest rate sensitivity constrains growth. Higher rates suppress mortgage originations and reduce new insurance opportunities. Persistency can help offset this—loans stay on the books longer when nobody refinances—but a prolonged high-rate environment can still cap growth.

Concentration risk creates vulnerability. Mortgage insurance is a relationship business with concentrated customers. Intense competition for those lender relationships, or the loss of a significant customer, can move results quickly.

Limited growth ceiling exists. As Essent gets bigger, market share gains naturally get harder. Over time, growth will tend to converge toward overall mortgage market growth unless new products or markets open up.

Tail risk never fully disappears. A truly severe housing crisis—think 30%+ home price declines—would stress any mortgage insurer regardless of underwriting quality. Black swan events can overwhelm even disciplined risk management.

Key Risks to Monitor:

Housing affordability limiting first-time buyers—if monthly payments stay out of reach, origination volume can weaken even if underlying demographic demand is strong.

GSE conservatorship resolution—any shift in PMIERs or GSE practices could change the competitive map quickly.

Credit risk transfer evolution—if the GSEs expand alternative risk transfer mechanisms that reduce reliance on traditional MI, that’s a structural threat to the industry.

Technology disruption—Essent has positioned itself as a tech-forward MI player, but fintech could still attack distribution or underwriting workflows over time.

XIII. The Inflection Points That Defined Essent

If you zoom out, Essent’s story isn’t a smooth upward line. It’s a series of gates—moments where the company either earned the right to keep playing, or it didn’t. Seven inflection points, in particular, explain how a contrarian startup turned into an industry fixture:

1. 2008 Crisis & Founding Moment (2009-2010): The financial crisis didn’t just create chaos. It created white space. While most founders hunt for a sunny forecast, Casale chose the opposite: start a mortgage insurer in the worst recession since the Great Depression. That timing gave Essent its defining structural advantage—a clean slate. No legacy portfolio. No pre-crisis losses. No hidden landmines waiting to detonate years later.

2. GSE Approval (February 2010): This was the real “company exists” moment. In February 2010, Essent became the first mortgage insurer approved by the GSEs since 1995. Without that approval, Essent wouldn’t have been a challenger—it would’ve been locked out of the market entirely. With it, the entire addressable conventional market opened up.

3. IPO & Public Markets Access (October 2013): On October 31, 2013, Essent went public. The IPO did more than raise capital. It validated the model and, just as importantly, signaled durability to lenders. In mortgage insurance, customers aren’t buying a feature—they’re choosing a long-term counterparty. Public markets access helped Essent look permanent.

4. Reaching #2 Market Share (~2016): By capturing meaningful share from wounded incumbents, Essent crossed a psychological line. It wasn’t a post-crisis experiment anymore. It was a real force. That legitimacy attracted more lender relationships, deepened confidence among counterparties, and reinforced the flywheel with investors.

5. Capital Optimization via Reinsurance (2016-2018): Credit risk transfer marked a shift in how Essent managed the business. The old model was effectively “buy and hold” risk. The newer approach became “buy, manage, and distribute” risk—sharing exposure with reinsurers and capital markets. The payoff was better capital efficiency, reduced tail risk, and a more sophisticated playbook for compounding through cycles.

6. COVID Stress Test (2020): COVID was the gut-check. Markets initially priced in a 2008 repeat, but government intervention and surging home prices flipped the outcome. Defaults didn’t materialize the way people feared, and Essent came through with record profitability. The model didn’t just survive a stress event—it proved it could bend without breaking.

7. Rate Shock Survival (2022-2024): The next test wasn’t credit. It was volume. Rising rates crushed refinancing and squeezed affordability, cutting the easy growth out of the system. Essent staying profitable through that kind of slowdown proved something different: maturity. Not just resilience in a housing-led downturn, but adaptability when the market simply stops moving.

XIV. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Essent's story offers lessons that travel well—across cycles, across industries, and across founder and investor playbooks:

Contrarian Timing: Casale chose to start a mortgage insurer in the worst recession since the Great Depression, right when the housing market was still in free fall and the established names were failing. That sounds reckless until you see the advantage: weakened competitors, a desperate market need for credible private capital, and a post-crisis regulatory reset that rewarded the firms built to survive. The best time to start is often when everyone else has just proved what doesn’t work.

Distribution is Everything: In B2B financial services, you don’t win on product features alone. You win on trust, responsiveness, and relationships. Casale leaned into that reality early—showing up in person to meet lenders, prospects, and partners. In a business where the “product” is really a long-term promise to pay in a downturn, people do business with people they know.

Clean Balance Sheet = Competitive Weapon: Essent was funded by private capital and built without legacy exposures. That wasn’t just a philosophical advantage—it was operational. No old book bleeding capital. No hidden landmines from bubble-era underwriting. It meant faster decisions, more disciplined pricing, and the freedom to play offense while others were cleaning up the past.

Technology as Differentiator: Even in a traditionally “boring” corner of finance, digital execution can separate winners from everyone else. Essent invested in tools and platforms that made it easier for lenders to do business with them—faster decisions, smoother integration, less friction. Over time, those conveniences turn into real efficiency advantages and real switching costs.

Regulatory Moats are Real: GSE approval and ongoing PMIERs compliance aren’t paperwork—they’re gates. Essent’s edge wasn’t fighting regulation; it was embracing it and building for it from day one. In highly regulated markets, understanding the rules better than your competitors can be a durable advantage.

Cyclical Businesses Need Discipline: Mortgage insurance is unforgiving. The good years tempt everyone to loosen standards; the bad years punish whoever did. Essent’s story reinforces the unglamorous truths: conservative underwriting, robust capital management, and the patience to build reserves instead of maximizing short-term optics.

Scale Matters in Insurance: Scale isn’t vanity here. It spreads fixed costs, improves the quality of risk data, deepens diversification, and strengthens the ability to absorb shocks. In insurance, size can be strategy.

The Long Game: Casale consistently emphasized building for long-term success, not just quarterly outcomes. In financial services, trust is earned slowly and lost fast. Market position compounds when counterparties believe you’ll still be standing when the cycle turns.

Capital Allocation Sophistication: Mature businesses don’t just grow—they choose how to deploy cash. Essent’s increased dividend and new share repurchase authorization signaled confidence in the durability of its cash flows, and a commitment to balancing reinvestment with returning capital to shareholders.

XV. Current State & What to Watch (2024-2025)

By late 2025, Essent looked less like a post-crisis upstart and more like what it set out to become: a steady, well-capitalized counterparty in a market that never stops stress-testing confidence.

On the third-quarter 2025 call in November, Mark A. Casale put it plainly: “We are pleased with our third quarter results, which again demonstrate the strength and resilience of our business model.” He credited “continued favorable credit trends” and the interest rate environment—specifically its lift to policy persistency and investment income—for helping Essent keep producing what he called “high-quality earnings.”

Operationally, the business was holding its shape. New insurance written in Q3 2025 was $12.2 billion, slightly below $12.5 billion in Q2 2025 and matching the general plateau versus $12.5 billion in Q3 2024. The bigger story was the installed base. Insurance in force rose to $248.8 billion as of September 30, 2025, up from $246.8 billion at June 30, 2025 and $243.0 billion a year earlier.

Profitability and balance sheet strength remained the company’s calling cards. Return on equity ran at 13% annualized year-to-date through Q3 2025. U.S. mortgage insurance in force was up about 2% year-over-year to roughly $249 billion, and persistency was 86% as of September 30, 2025—exactly the kind of “higher rates, fewer refinances” dynamic that keeps premiums flowing longer than expected. Consolidated cash and investments stood at $6.6 billion.

The capital story stayed just as conservative. Operating expenses in Q3 2025 were $34.2 million. Essent reported a PMIERs sufficiency ratio of 177% as of September 30, 2025, with a debt-to-capital ratio of 8%. Statutory capital was $3.7 billion, and the risk-to-capital ratio was 8.9:1.

With growth more constrained by the rate environment than by credit, capital returns continued to matter. Year-to-date through October 31, Essent repurchased 8.7 million shares for $501 million, and the board approved a new $500 million repurchase authorization through year-end 2027. And in a business where ratings are a competitive weapon, Moody’s upgraded Essent Guaranty to A2 from A3 on August 6, 2025, and upgraded Essent Group’s senior unsecured rating to Baa2 from Baa3, both with a stable outlook.

Strategically, the message was continuity, with a little bit of optionality. Essent kept its focus on the core mortgage insurance franchise, while also exploring diversification through Essent Re and its title insurance operations. Technology investment stayed central—continued evolution of risk-based pricing and AI-driven analytics—while market share defense still came down to the old fundamentals: service quality and lender relationships.

Industry-wide, the constraints were familiar. Housing affordability remained the dominant concern. Credit risk transfer continued to evolve, with private mortgage insurers still playing a meaningful role. And the big structural unknown—GSE reform and the future of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—remained unresolved, with no clear near-term endpoint.

Management stability matched the business posture. Mark Casale remained Chairman, CEO, and President. Christopher Curran served as President of Essent Guaranty, leading the core mortgage insurance business. The broader leadership team that built Essent from inception largely remained in place.

If you want to track whether Essent is getting stronger or simply getting older, three operating signals matter most:

-

Insurance in force growth: the size of the premium-earning base, driven by both new production and how long policies stay on the books.

-

Default rate and loss ratio: the credit heartbeat of the portfolio, and the clearest read on whether stress is building or fading.

-

PMIERs sufficiency ratio: the capital cushion that determines how much flexibility Essent has—for growth, buybacks, or absorbing shocks when the cycle turns.

XVI. Epilogue & Future Scenarios

Looking ahead, Essent’s path will be shaped as much by the system it operates in as by anything management can control. You can think about the next chapter in four plausible scenarios:

Scenario 1: Steady-State Oligopoly

The base case is that not much changes—structurally, at least. The same small set of approved mortgage insurers competes for lender relationships inside a tightly regulated framework that keeps new entrants out and, most of the time, keeps pricing from turning into a race to the bottom. In that world, Essent stays a top-tier player, produces consistent earnings, and keeps returning capital through dividends and buybacks. It starts to look less like a “post-crisis disruptor” and more like a durable incumbent—closer to mature categories like credit cards or auto insurance: competitive, not flashy, but predictably profitable.

Scenario 2: Consolidation

With multiple players of different sizes—and scale advantages that get more valuable in tougher markets—M&A is always on the table. Essent could play offense and acquire a smaller competitor to gain share and drive efficiencies. Or it could be the prize: an acquisition target for a larger financial services company that wants a meaningful position in mortgage credit risk. The Arch/United Guaranty deal proved consolidation can happen, and if it happens again, it will come down to strategic fit and valuation.

Scenario 3: Regulatory Disruption

The biggest wild card remains the same one the industry has lived with since 2008: Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are still in conservatorship, and there’s no clear endgame. Any resolution—privatization, wind-down, restructuring—could change what kinds of loans the GSEs support and what they require in terms of mortgage insurance. Changes in or to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, whether through Federal legislation, restructurings or a shift in business practices, represent key risk factors. And even without a grand reform, the system can evolve around the edges: alternative credit risk transfer mechanisms that don’t rely on traditional MI could expand, and that would reshape the industry’s role.

Scenario 4: Housing Crisis 2.0

The scenario everyone hopes stays hypothetical is another true housing downturn. If home prices fell 20% to 30% in a recession scenario, defaults and claims would rise sharply, and every mortgage insurer would be stress-tested again. Essent’s conservative underwriting and strong capital position should help it hold up better than many—but no one gets through a severe housing drawdown unscathed. That’s the nature of the product: it exists for the bad years, and the bad years are never gentle.

The Bigger Picture: Private mortgage insurance plays an essential role in America’s housing finance system. It channels private capital to absorb mortgage credit risk that would otherwise fall more heavily on taxpayers through government programs. A competitive mortgage insurance industry backed by private capital serves the housing finance system very well. Today, over $1.3 trillion of mortgages are financed by loans with private mortgage insurance.

Lessons for Founders: Essent is a blueprint for finding white space in regulated industries. A crisis weakened incumbents. Regulatory change raised the bar and created room for someone built to meet it. And patient capital funded a multi-year build, not a quick flip. If you’re looking for a similar opening, the pattern is clear: wounded incumbents, shifting rules, and a structural need the market still can’t do without.

Lessons for Investors: Essent is a case study in what you might call a cyclical compounder—a company that can generate returns through economic cycles while quietly strengthening its competitive position. The recurring traits are unglamorous but powerful: conservative management, a strong capital base, a clean balance sheet, steady technology investment, and customer-focused execution. It may look boring in any single quarter, but over time that combination can deliver compelling long-term outcomes.

Final Reflection: Essent exists because Mark Casale and his team made a bet that sounded irrational in 2009. They raised roughly $600 million when anything tied to mortgages felt radioactive. They built a company when trust in financial institutions had evaporated. And they pushed through licensing, GSE approvals, and a regulatory maze that would have broken a less committed team.

Mark A. Casale is the founder, Chief Executive Officer and Chairman of the Board of Directors of Essent Group Ltd. Founded in 2008 by Mr. Casale with $500 million of equity funding, Essent Group Ltd. has grown to a market capitalization of approximately $6B and manages approximately $240B of insurance in force. Under Mr. Casale's leadership, Essent has become a leading mortgage insurer and reinsurer serving as a trusted and strong counterparty to lenders and GSEs and has enabled more than three million borrowers to become successful homeowners.

From the ashes of the 2008 financial crisis, Essent rose into the core of American housing finance. The audacious startup that shouldn’t have worked became the category challenger that helped redefine what “safe” looks like in private mortgage insurance. That’s a story worth telling.

XVII. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Resources for Deeper Understanding:

-

Essent Group Annual Reports & Investor Presentations (2013-present) - The primary source. These filings and decks lay out the financials, risk factors, and management’s own narrative of the business. Available at ir.essentgroup.com.

-

"The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report" (2011) - The definitive post-mortem on the 2008 crisis—the shock that set the stage for why a clean-sheet mortgage insurer like Essent could even exist.

-

Urban Institute Housing Finance Policy Center - Reliable, ongoing research on housing finance, affordability, and mortgage insurance policy—useful for tracking how the “rules of the system” keep evolving.

-

MGIC, Radian, Enact, Arch MI Investor Materials - The best way to understand Essent is to see how its closest competitors describe the same market: pricing, credit, capital, and share.

-

Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) PMIERs Documentation - The rulebook. PMIERs is the capital and eligibility framework that governs who gets to play in GSE mortgage insurance—and how aggressively they can grow.

-

Journal of Housing Research - Academic work on mortgage insurance, risk, and housing policy. Less narrative, more depth—helpful if you want the underlying research.

-

Mark Casale Interviews & Conference Presentations - Hear the strategy directly from the source, including appearances at events like the KBW Financial Services Conference and the Barclays Global Financial Services Conference.

-

"Guaranteed to Fail" by Viral Acharya et al. - A broader look at the GSE system and housing finance incentives—context that explains why private mortgage insurance matters, and why it’s politically and economically complicated.

-

Mortgage Bankers Association Research Reports - Industry data on origination volumes, purchase vs. refinance mix, and lender behavior—the demand side that drives MI cycles.

-

Keefe, Bruyette & Woods (KBW) Mortgage Insurance Sector Reports - Specialist analyst coverage on industry structure, competitive dynamics, and company-by-company comparisons from one of the key research shops in the sector.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music