e.l.f. Beauty: From Dollar Store Disruptor to Digital Beauty Powerhouse

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s 2004, and you’re standing in a drugstore cosmetics aisle. The shelves are a wall of the usual suspects—Maybelline, CoverGirl, Revlon—and the prices feel… arbitrary. A tube of mascara that costs next to nothing to make sells for fifteen bucks. Foundation made in the same kinds of factories that supply prestige brands comes with a huge markup simply because it sits in the “right” display. “Affordable” still meant expensive. And a handful of giant companies effectively decided what most people could buy, and what it would cost, to put on their faces.

Now jump ahead two decades and the picture is unrecognizable. e.l.f. Beauty—born online selling makeup for a dollar—has grown into one of the biggest success stories in American beauty. It’s the fastest-growing major beauty brand in the country, with a market cap approaching $4.8 billion. In fiscal 2024, the company crossed $1 billion in net sales, up 77%, and e.l.f. Cosmetics grew market share for the fifth straight year.

So that’s the question at the heart of this story: how did a brand that started with dollar makeup become the number two mass cosmetics company in the United States—passing legacy names like Revlon and CoverGirl and competing toe-to-toe with L’Oréal’s powerhouse portfolio?

The answer isn’t “they sold cheaper.” It’s that e.l.f. rewired how beauty works. They treated social platforms as the main stage, not a side channel. They built products that were designed to be discovered in tutorials, tested in comments, and shared by real people—not pushed by department-store gatekeepers. And they used data not just to optimize ads, but to decide what to launch next, how fast to move, and when to double down.

The results show up in the scoreboard. Not long ago, e.l.f. sat around fifth place in mass cosmetics by Nielsen tracking. By August 2023—after 19 straight quarters of net sales growth—it had climbed to number three, with about 9.5% share, behind only L’Oréal and Maybelline. And it didn’t stall there. By Q2 fiscal 2025, e.l.f. posted 40% net sales growth, added meaningful share in the U.S., and nearly doubled international net sales—its 23rd consecutive quarter of both sales growth and market share gains.

This is also a story about positioning. e.l.f. has always been clear about what it stands for: premium-quality products at radically accessible prices, built around positivity, inclusivity, and community. That combination—high quality, low price, and culture-native marketing—was so counter to the old beauty playbook that it made the industry’s incumbents look slow, expensive, and out of touch.

And that’s why this matters beyond makeup. e.l.f.’s rise is a modern case study in how consumer brands win now: community over ad spend, speed over legacy scale, and authenticity over glossy celebrity campaigns. It’s also a reminder of the risk: beauty is fashion, and fashion is fickle. The same internet that can make you famous can move on tomorrow.

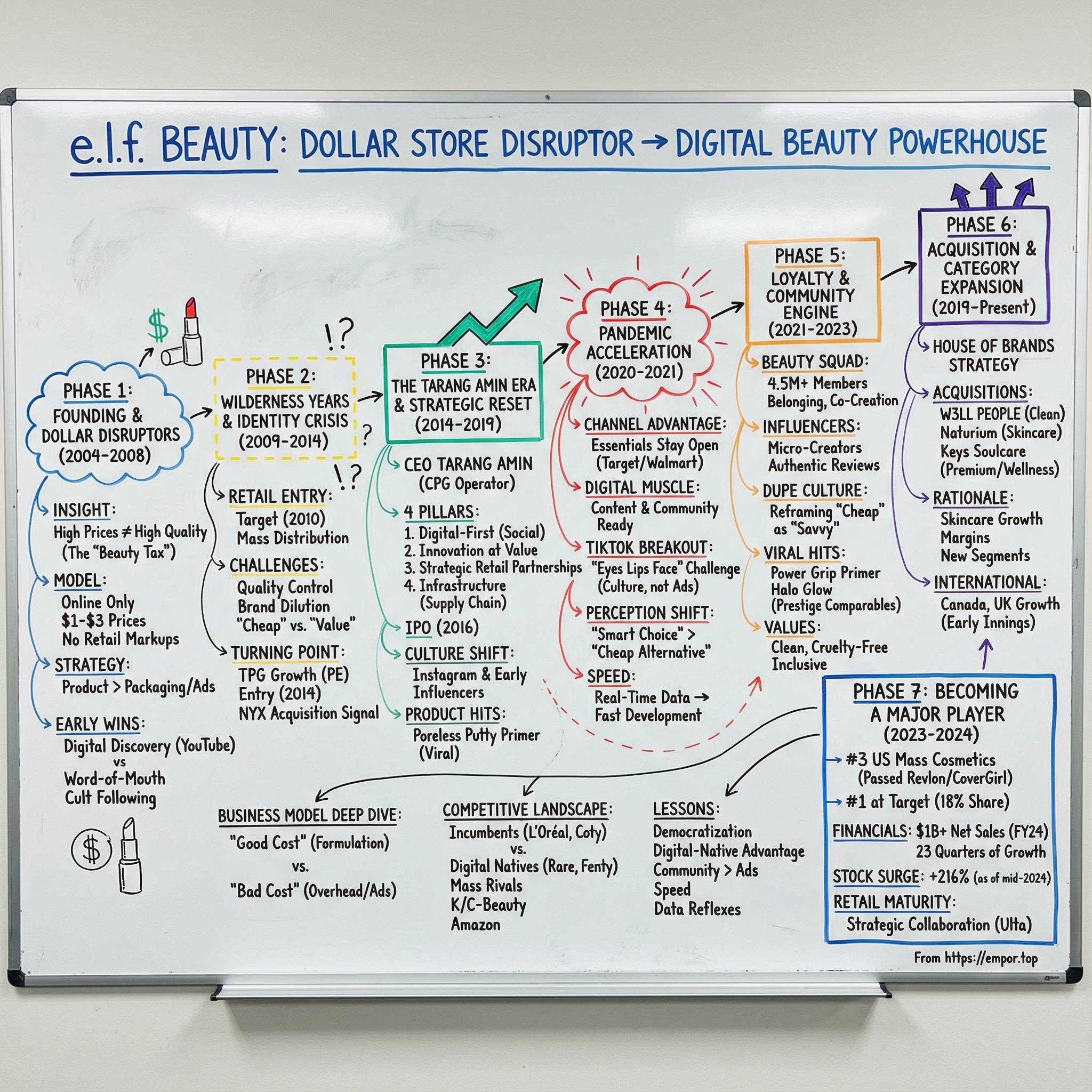

In this episode, we’re going to trace how e.l.f. got here—from a scrappy online upstart, through an identity crisis in retail, to a CEO-led reset, a social-media flywheel, and eventually a position near the top of the mass market. Along the way, we’ll unpack the business model, the strategic inflection points, and the playbook e.l.f. built for turning market share into real, compounding growth.

II. The Beauty Industry Before e.l.f.: Context & Incumbents (1990s–2000s)

Before e.l.f. could break the rules, it had to enter an industry built to enforce them. Beauty wasn’t just competitive—it was engineered to stay the same. A small number of companies controlled the brands, the shelves, the advertising, and, most importantly, the pricing logic. If you wanted to play, you played their game.

The Oligopoly Structure

By the early 2000s, global beauty had consolidated into an oligopoly dominated by a handful of giants—Estée Lauder, L’Oréal, Procter & Gamble, and Coty. Between them, they owned deep portfolios across both prestige and mass. That mattered because it let them “catch” consumers at any budget: splurge at a department store counter, then top up at the drugstore. Different packaging, different vibes, same corporate parent collecting the margin either way.

And those margins were protected by a shared belief: beauty is emotional, so beauty can be expensive. A lipstick wasn’t sold as wax and pigment. It was sold as confidence. A foundation wasn’t a formula. It was transformation. The industry spent heavily to reinforce that story—TV campaigns, glossy magazine ads, celebrity endorsements, and premium retail real estate—and then pointed to that spend as proof the prices were justified.

The Prestige vs. Mass Divide

Beauty also ran on a clean, almost moral separation: prestige versus mass. Prestige brands like Estée Lauder, MAC, and Clinique lived in department stores. They came with beauty advisors, countertop rituals, sampling, and the feeling that you were being initiated into something special. The prices reflected all of it: not just the product, but the staffing, the real estate, the inventory complexity, and the theater.

Mass brands like Maybelline, CoverGirl, and Revlon lived under fluorescent lights in drugstores and big-box aisles. They were cheaper—but not cheap in the way their production costs suggested. The category’s economics were wildly attractive: products that cost very little to make could sell for many multiples of that cost, and consumers didn’t revolt because the purchase felt personal, even intimate.

Retailers enforced the split. Department stores acted as gatekeepers for prestige distribution and took their cut through margins and requirements like staffed counters. Mass retailers demanded their own form of tribute: promotional spend, fees to earn shelf space, and constant deal cycles. Either way, the middle of the chain extracted value—and brands built their operating models around paying it.

The "Beauty Tax" Explained

This is where the so-called “beauty tax” came from. Not a literal tax, but a structural markup layered onto almost every item. A mascara might cost well under a dollar to manufacture, but by the time you added packaging, retailer margins, and the marketing machine needed to keep the brand visible, the price at the shelf could easily hit the low teens.

The punchline is that, in many cases, the least-funded piece of the puzzle was the product itself. Formulation innovation mattered, but it wasn’t where the system was designed to spend. The system was designed to spend on perception.

That created a strange mix of strength and fragility. Strength, because incumbents had scale and shelf control. Fragility, because if someone could strip out the expensive parts—especially traditional marketing and distribution—the whole pricing logic started to look optional.

The Early 2000s Retail Evolution

The ground was also shifting under the incumbents in ways they didn’t fully appreciate yet. Sephora entered the U.S. in 1998 and made prestige feel less intimidating. It replaced the department store counter with an open-sell environment: browse, swatch, experiment, leave without buying if you want. That single change trained consumers to expect access.

Ulta—founded earlier, in 1990—pushed a different kind of boundary: prestige and mass in the same store, plus a salon. It quietly acknowledged something obvious in hindsight: real people don’t shop according to the industry’s categories. They mix and match. They’ll pay up for one thing and save on another, based on what they care about.

Target, too, was upgrading its beauty presentation because cosmetics were a high-margin traffic driver. Walmart remained the volume king of mass retail, moving huge quantities for consumers who watched every dollar.

But one channel was still treated like a sideshow: the internet. Beauty e-commerce existed, but it wasn’t where the category’s power players placed their bets. The conventional wisdom was simple: you can’t sell makeup online at scale because people need to see shades, feel textures, and test in person. Color matching and trust were physical problems, and the store was the solution.

That assumption would not age well.

Why Disruption Was Inevitable

In retrospect, the pre-e.l.f. beauty industry had all the classic conditions for disruption. Incumbents were addicted to margins that had drifted far from underlying costs. Gatekeepers were expensive and entrenched. Marketing had ballooned into a barrier to entry more than a true advantage. And a new generation was arriving that didn’t trust traditional ads, didn’t love department stores, and spent its time in digital spaces the beauty giants didn’t yet understand.

The old model asked consumers to pay for aspiration. The disruptor’s question was different: what if you could deliver great product without the markup—and build the emotional connection in a place that didn’t require a magazine spread or a department store counter?

III. Founding Story: The Dollar Disruptors (2004–2008)

e.l.f.’s origin story has all the ingredients of a classic disruptor—outsiders, a simple insight, a big market—but the hook isn’t just “we’ll sell it cheaper.” It’s that the founders looked at the beauty industry and saw a machine full of expensive parts that didn’t actually make the product better.

The Founding Team

Alan Zeichner and Joey Shamah weren’t beauty lifers. They were entrepreneurs, and in 2004 they built e.l.f. around a question that sounds obvious once you say it out loud: why are these products priced like luxury goods when they cost so little to produce?

Cosmetics, they realized, had a quiet secret. Plenty of prestige brands were already using contract manufacturers in Asia. Often, the same kinds of factories—and similar processes—were producing products across price tiers. What changed wasn’t necessarily the quality bar coming off the line. What changed was everything wrapped around it: the packaging, the marketing, and the distribution model that demanded a big cut at every step.

So the gap between a twenty-dollar lipstick and a two-dollar lipstick wasn’t always formula-deep. Sometimes it was story-deep.

The founders’ bet was straightforward: strip out the costs that don’t improve performance, and make great makeup accessible to everyone. The brand name made that mission literal—eyes, lips, face—three everyday categories, not a gated club.

The "e.l.f." Naming and Philosophy

“e.l.f.” was meant to feel friendly and modern, not intimidating. It signaled a brand that didn’t need a counter, a consultant, or a permission slip. And it quietly rejected the industry’s old assumption that consumers needed to be guided by experts.

Instead, e.l.f. leaned into a different idea: people—especially younger shoppers—were becoming self-taught. They’d trust friends, reviews, and online communities more than a glossy ad or a department-store script. e.l.f. didn’t need to “educate” consumers into buying. It needed to give them something worth talking about.

The Original Business Model

At the start, e.l.f. was online-only. That choice wasn’t just about being early to e-commerce—it was the business model. Sell direct, keep overhead low, and price products at one to three dollars. No retail markups. No slotting fees. No expensive middlemen.

Over time, e.l.f. would expand into drugstores and mass retailers like Walmart and Target, while continuing to sell directly through its digital channel. But in those early years, the internet was the wedge.

The company kept costs down by hitting the big line items that made traditional beauty so expensive:

Manufacturing Innovation: e.l.f. didn’t build factories. It partnered with contract manufacturers and focused its dollars on product quality rather than ornate packaging and frills.

Distribution Efficiency: selling online let e.l.f. avoid the economic toll of traditional retail—margins and fees that could swallow a huge chunk of the shelf price.

Marketing Reinvention: while legacy beauty poured money into TV, magazines, and celebrity campaigns, e.l.f. largely stayed out of that arms race. The plan was to let the price and the performance create word-of-mouth.

The Digital Beauty Culture Emerges

The timing couldn’t have been better. Right as e.l.f. was finding its footing, beauty discovery started moving online. YouTube launched in 2005, and it didn’t take long before tutorials became a new kind of beauty counter—one where the “advisor” was a peer, and the product recommendations felt earned.

e.l.f. fit that world perfectly. At one to three dollars, it was easy for viewers to try what they’d just watched. The low price removed the fear of being wrong. You could experiment, mess up, start over, and still spend less than you would on a single prestige item.

Building the Cult Following

This wasn’t an overnight rocket ship. The early years were scrappy. e.l.f. grew the old-fashioned way: customers used the products, liked them, and told other people. A small but passionate group of budget-conscious beauty fans started to treat e.l.f. like a secret—the rare aisle-level find that didn’t feel like a compromise.

Beauty bloggers became accelerants. Before “influencer marketing” became a formal strategy, bloggers were already doing side-by-side reviews and pointing out the uncomfortable truth: for a lot of everyday makeup, the quality gap didn’t match the price gap. And that message landed especially well with young consumers who’d learned to tune out traditional advertising.

e.l.f.’s digital footprint was modest by today’s standards, but it proved something that mattered: cosmetics could sell online, and consumers didn’t always need to test in person—especially when the financial risk was so low.

The Foundation for Growth

By 2008, e.l.f. had done the hard first thing: it proved the concept. It had a loyal customer base, a clear positioning, and a model that made traditional pricing look—at best—padded.

But success came with constraints. Direct-to-consumer alone limited how big e.l.f. could get. Awareness was still concentrated among enthusiasts. And the “dollar makeup” identity, powerful as it was, carried a danger: it could keep e.l.f. in a bargain niche instead of letting it become a true mass-market leader.

To break out, e.l.f. would need to expand beyond online without losing what made it work in the first place. And it would have to learn a different set of skills: scaling quality, navigating retail partnerships, and building the infrastructure of a real contender.

IV. The Wilderness Years: Retail Expansion & Identity Crisis (2009–2014)

Every breakout founder story has a messy middle—the part where momentum doesn’t feel like momentum. It feels like whiplash. New doors open, but each one comes with hidden costs: operational complexity, brand confusion, and the slow creep of compromises that seem small in the moment.

For e.l.f., that “wilderness” stretched from roughly 2009 to 2014. The company had proven people wanted good makeup at radically low prices. Now it had to prove it could scale that promise in the real world—on real shelves, under real fluorescent lights—without becoming just another cheap brand.

The Target Partnership and Mass Retail Entry

The big leap was mass retail, starting with Target around 2010. On paper, it was everything e.l.f. needed: national distribution, instant credibility, and access to shoppers who were never going to discover a scrappy online-only brand.

But the second you move from DTC to a big-box shelf, the math changes. Mass retail demanded things the lean early model didn’t: better packaging to win attention in an aisle, promotional support to keep products moving, and price points that could absorb retailer margins while still feeling unmistakably “e.l.f.”

That last part mattered. A one-dollar product that works online doesn’t automatically work in a store, where every inch of shelf space has a cost and every item needs enough margin to justify its slot.

At the same time, e.l.f. was benefiting from a broader consumer shift toward value—especially among younger shoppers. The brand was gaining traction in key channels like Target and, later, Ulta Beauty. The opportunity was real. So were the trade-offs.

Quality Control Challenges

Then came the hard part: making more product, more consistently, at higher volume. Scaling exposed gaps in the manufacturing and quality systems. Batches weren’t always uniform—something could perform beautifully one run and disappoint the next.

For most brands, inconsistent quality is a headache. For e.l.f., it was an identity threat. The entire promise was that low price didn’t mean low performance. If consumers couldn’t trust what they were buying, the brand’s core proposition collapsed.

Some of this was structural. Contract manufacturing relationships that worked at small scale got strained at larger volumes. Ingredient sourcing became more complicated. And the same speed that helped e.l.f. keep up with trends became a liability when quality checks and processes didn’t keep pace.

Brand Dilution Fears

Retail also forced a different kind of question: what exactly was e.l.f. now?

Online, the “dollar makeup” story was charming—and it made experimentation feel risk-free. In a mainstream aisle, next to incumbents like Maybelline and CoverGirl, that same origin story could read differently. Cheap could still mean “not good,” especially to shoppers who hadn’t been part of the early online discovery.

Inside the company, that tension turned into a debate: stay ultra-low priced and risk being boxed into the bargain bin, or move upmarket and risk losing the thing that made e.l.f. special.

The result was uneven. Some products crept up in price, but without a simple, consistent explanation consumers could feel. And that’s the danger zone for any brand: when you’re no longer clearly the value choice, but you’re not yet the aspirational one either. You end up in the middle—competing with everyone and owned by no one.

Private Equity Enters: TPG Growth

By 2014, e.l.f. brought in a different kind of partner. TPG Growth acquired a majority stake in the company. It was validation—proof that a serious investor saw real upside in what e.l.f. had built.

It was also a turning point. Private equity doesn’t invest for vibes. It brings pressure: professionalize the business, tighten execution, accelerate growth, and build toward an eventual exit.

That meant new discipline and new ambition. It also marked the end of e.l.f. as a purely scrappy startup and the beginning of its evolution into a scaled competitor—with all the risk that comes with “growing up.”

The NYX Signal

That same year, the market sent a loud signal. L’Oréal acquired NYX Cosmetics in 2014 for approximately $500 million.

NYX had built a similar kind of following—accessible, trend-forward—but with higher price points and a more polished image. The deal proved the giants were paying attention. “Affordable” wasn’t a niche anymore. It was strategic.

And for e.l.f., it was a mirror. NYX had become what e.l.f. was still trying to figure out how to be: mass, modern, and credible—affordable without feeling disposable.

The Realization

By 2014, the company was at a crossroads. The founding insight was still right: people wanted high-quality beauty at accessible prices. Beauty discovery was moving faster and faster into digital spaces, which should have favored a brand like e.l.f. And the competitive landscape was shifting in ways that created openings for challengers.

But the next level required capabilities e.l.f. didn’t yet have: a clearer positioning, operational excellence in supply chain and quality, a more sophisticated approach to retail, and a team built for scale.

e.l.f. didn’t need a new mission. It needed a reset—one that could preserve the disruptive spirit while building the infrastructure of a real contender.

The stage was set for the transformative leadership that would arrive with Tarang Amin.

V. The Tarang Amin Era: Strategic Reset & Digital Transformation (2014–2019)

e.l.f.’s leap from a drifting “cheap makeup” brand to a modern beauty contender traces back to one decision in 2014: bringing in Tarang Amin as CEO. On the surface, it looked like a strange hire. Amin wasn’t a beauty insider. He was a consumer packaged goods operator. But that was the point. e.l.f. didn’t need more people who understood lipstick. It needed someone who understood how to scale a brand without breaking it.

The Unconventional Choice

Amin came up through the machine: Procter & Gamble, Clorox, then Schiff Nutrition. Those are companies built on repeatable execution—tight operations, disciplined marketing, and sophisticated retail playbooks. When Amin talked about e.l.f.’s prospects, he wasn’t selling glamour. He was selling conviction: “We’re quite bullish about the future and particularly in terms of how we’re positioned.”

What he brought was the missing layer between e.l.f.’s promise and e.l.f.’s reality. The company already had a disruptive idea and real consumer love. What it lacked were the systems and focus to turn that into durable advantage.

The Diagnosis

Amin walked into a brand with momentum and mess.

e.l.f. had product-market fit, but it was chasing opportunities instead of building a strategy. The brand message had gotten fuzzy—was e.l.f. still the dollar-store disruptor, or was it “affordable quality,” or something else? Different channels told different stories, which is how brands quietly lose trust.

Retail was another weak spot. The company had partnerships, but not the kind of data-driven, planful approach that turns shelf space into a compounding asset. e.l.f. was too often reacting to what retailers asked for instead of shaping the relationship.

And most painfully, the company wasn’t fully exploiting what should have been its unfair advantage: digital. e.l.f. was born online, but it hadn’t yet rebuilt itself as a digital-first beauty brand in a world where attention was moving to social platforms.

The Strategic Pillars

Amin’s reset centered on four moves that fit together like gears:

Digital-First Strategy: Not “we have a website,” but social as the core marketing engine. e.l.f. would show up where its customers actually lived—YouTube and Instagram in this era—leaning into community, creator culture, and content that didn’t feel like an ad.

Product Innovation at Value: The mission wasn’t to be the cheapest. It was to be the smartest buy. Improve quality systematically while keeping prices accessible, so the value proposition felt undeniable.

Strategic Retail Partnerships: Instead of chasing distribution everywhere, e.l.f. would focus on where it could win—especially Target, Walmart, and Ulta—and manage those relationships deliberately, with better planning, better merchandising, and collaboration that helped the whole category grow.

Building Infrastructure: The unsexy work: supply chain, systems, talent, and process. If e.l.f. wanted to scale without quality hiccups and operational fires, it needed a foundation that matched its ambition.

The IPO and Public Market Debut

That reset helped set the stage for e.l.f.’s IPO in September 2016. Going public opened a new chapter: capital to invest, visibility with retailers and partners, and eventually a public currency that could support acquisitions.

But it also brought a harsher spotlight. Public markets don’t grade on potential. They grade on consistency.

Post-IPO Challenges

The years after the IPO were not a victory lap. The stock struggled. Activist investors questioned the strategy. Some observers started to wonder if e.l.f. had hit its ceiling—whether the low-price positioning that fueled its early love would ultimately cap how big it could get.

What they missed was that Amin wasn’t just trying to win a quarter. He was building capabilities that take time to show up on the scoreboard: a sharper digital marketing muscle, faster product development, a more resilient supply chain, and deeper, more productive retail partnerships.

The Cultural Moment Arrives

At the same time, the culture was shifting in e.l.f.’s favor.

Beauty discovery was moving from the old gatekeepers to the new ones. YouTube tutorials had already changed how people learned. Instagram pushed makeup into everyday visual culture. And by the late 2010s, TikTok was beginning to emerge as the next platform that would matter.

These weren’t just new ad channels. They reshaped consumer expectations. Younger shoppers wanted creativity, individuality, and creators who felt like peers—not glossy perfection delivered from on high. They wanted to try trends fast, learn fast, and share fast.

That’s exactly the environment where e.l.f.’s model made sense: quality that held up on camera, prices that made experimentation easy, and a brand voice that felt native to the internet.

Early Product Victories

The reset started to show in the products—especially the ones that seemed to catch fire “overnight,” even though they were anything but accidental.

The Poreless Putty Primer, launched in 2018, became a cult favorite: a product people compared to prestige primers at a fraction of the price, spreading because consumers genuinely wanted to tell other consumers about it.

The Mad for Matte palette and other eyeshadow launches proved e.l.f. could compete in categories where prestige brands had long owned the conversation. Influencers and everyday buyers were doing side-by-sides and landing on the same conclusion: this performs like products that cost many times more.

That was Amin’s strategy in action: products built to be discovered digitally, to perform under real scrutiny, and to be priced so trial turned into recommendation.

By 2019, e.l.f. had done the hard, quiet work. The foundation was in place—the infrastructure, the focus, the digital muscle, and the early hero products. The company was ready for an acceleration.

What it didn’t know was that the next acceleration would come from a global pandemic that would force the entire beauty industry to operate like the internet had always been the main stage.

VI. The Pandemic Acceleration: Digital Native Meets Digital Reality (2020–2021)

The COVID-19 pandemic rewrote the rules of retail almost overnight. For a lot of beauty companies, it was a full-body blow: stores closed, sampling disappeared, and the entire “come in and try it on” model stopped working. For e.l.f., it was the moment when years of quiet preparation suddenly looked like a cheat code.

The Channel Advantage

When lockdowns shuttered department stores and Sephora went dark, the expectation across the industry was simple: makeup sales were going to get crushed. After all, the category had always leaned on in-person discovery—shades, textures, testers, and the reassuring presence of a real store.

But e.l.f. was set up differently. Its core customers already shopped mass and already trusted the brand online. And crucially, its biggest retail partners—Target and Walmart—stayed open as essential retailers. While prestige brands watched their main stages disappear, e.l.f. was still sitting right there in the aisles people were already walking for essentials.

So when shoppers needed a small pick-me-up, or wanted to try something new without splurging, e.l.f. was the easy yes. The brand kept putting up high double-digit sales gains quarter after quarter as consumers piled into low-priced products—either through e.l.f.’s own site or at the mass retailers that never closed.

Digital Infrastructure Pays Off

This is where Tarang Amin’s earlier bets started paying back with interest. The company’s e-commerce engine didn’t just survive the shift—it benefited from it. Digital sales grew sharply year over year, and online became a meaningfully larger portion of the business.

But “digital” for e.l.f. wasn’t just a checkout page. The company had already been building the other half of the machine: content, community, and social engagement that made people feel like they were discovering e.l.f. in the wild, not being sold to. When the world moved online, e.l.f. didn’t have to translate its strategy. It was already speaking the language.

The TikTok Revolution

Then came the platform that turned the volume all the way up: TikTok.

While legacy brands were still treating TikTok like a confusing new ad channel, e.l.f. treated it like what it actually was—culture. The content was playful, quick, participatory, and designed to be remixed. And e.l.f. didn’t just show up on TikTok. It belonged there.

The breakout was the “Eyes Lips Face” campaign. Instead of producing a traditional commercial, e.l.f. commissioned an original song and asked users to create with it. The result was a tidal wave: billions of views, endless user-generated videos, and a case study that every marketer in beauty would study afterward.

The lesson wasn’t simply “go viral.” It was deeper than that: younger consumers don’t want to be talked at. They want to be in on it. e.l.f.’s campaign worked because it didn’t feel like an ad. It felt like an invitation.

Perception Transformation

The pandemic also accelerated a shift that e.l.f. needed for the long run: what the brand meant.

For years, “cheap makeup” had been both a weapon and a ceiling. During 2020 and 2021, e.l.f. started to break through that ceiling. Value became mainstream, and e.l.f. increasingly read not as a compromise, but as a smart choice—proof that you didn’t need prestige pricing to get results.

That distinction matters. “Settling” is weak positioning. “Choosing” is strong positioning. In a moment when shoppers were watching budgets and questioning markups, e.l.f. didn’t look like the brand you bought because you had to. It looked like the brand you bought because you were paying attention.

Data-Driven Development

As everything moved faster online, e.l.f.’s digital advantage got sharper. Social platforms weren’t just marketing channels—they were real-time focus groups. The company could see what people were talking about, what products were getting traction, and which trends were building before they hit the mainstream.

That feedback loop fed into speed. Compared to traditional brands working on long development timelines, e.l.f. could move from idea to launch far faster. When a trend started to form, e.l.f. had a better chance of meeting it while it was still hot—not after it cooled.

Supply Chain Resilience

Of course, none of that matters if you can’t keep product on shelves. The pandemic stress-tested supply chains everywhere, and beauty was no exception. e.l.f. held up better than many expected, helped by the operational muscle Amin had been building: tighter planning, stronger relationships, and systems that could handle volatility.

Even with all the chaos, the company expanded gross margin during the period, supported by a mix of factors including foreign exchange benefits, pricing actions internationally, cost savings, mix, and improved transportation costs.

Financial Inflection

By the time the industry started finding its footing again, e.l.f. had done more than survive. It had taken share, strengthened its brand, and proved that its model worked at scale—digital-first marketing, value-driven product, and a community flywheel that could outperform traditional ad spend.

It entered 2021 with real momentum and a clearer identity than it had ever had. e.l.f. wasn’t just a disruptor anymore. It was becoming a leader.

VII. The Loyalty & Community Engine: Building a Moat (2021–2023)

If the pandemic proved e.l.f.’s model could work, the years after proved it could stick. Plenty of brands got a temporary bump during COVID and then cooled off. e.l.f. kept climbing—and it wasn’t because it found a new trick. It was because it turned the internet attention it had earned into something far harder to copy: a loyalty-and-community engine that kept customers coming back, and kept new customers discovering the brand through them.

The Beauty Squad: Beyond Points

At the center of that engine was Beauty Squad. Members accounted for about 80% of sales on elfcosmetics.com, and the program grew to 4.5 million members—up 30% year over year. But the design wasn’t “buy more, get coupons.” It was built to make customers feel closer to the brand.

Beauty Squad offered early access to launches, exclusive content, and meaningful ways to participate. The message was subtle but powerful: you’re not just shopping here—you’re part of this. In a category where switching is as easy as grabbing a different tube off the shelf, that sense of belonging created real stickiness.

The Micro-Influencer Strategy

At the same time, e.l.f. leaned even harder into the kind of marketing that had always fit its personality. While competitors chased celebrities, e.l.f. kept betting on creators who felt like real people.

The strategy emphasized micro-influencers—smaller audiences, higher engagement, and recommendations that came across as genuine rather than paid-and-polished. It also tended to be more efficient: you could build a lot of creator relationships for the price of one celebrity contract. But the bigger edge was credibility. When a micro-creator says, “This actually works,” it lands differently—because their followers believe they mean it.

And that’s not something you can replicate just by spending more. It requires a brand that creators actually want to talk about.

Product Co-Creation

e.l.f. also started treating its community as a product-development partner, not just an audience. Feedback from loyal customers shaped formulations, shades, and sometimes even the underlying ideas for new products.

That changed the psychology of launches. When people feel like they asked for something and the brand delivered, they don’t just buy it—they champion it. It also improved the company’s odds. Instead of relying only on internal “expert intuition,” e.l.f. could pressure-test concepts with the people most likely to purchase, helping it commit resources more confidently and avoid more flops.

Viral Product Innovations

The output of that system was a string of products that didn’t just sell—they traveled through culture.

Power Grip Primer became a breakout hit as consumers framed it as a comparable alternative to higher-end primers. The internet did what it always does: side-by-sides, wear tests, and “here’s what I’m using instead” videos that doubled as both proof and promotion.

Halo Glow Liquid Filter took that dynamic even further. It captured the “dupe” moment perfectly—delivering results people compared to prestige products costing fifty dollars or more, at a price that made trying it feel effortless. The product generated huge organic buzz and pulled in new consumers who might not have considered e.l.f. before.

These weren’t lucky accidents. They were the strategy made tangible: find where prestige is charging for the story more than the performance, and offer something that holds up under the camera—and under the comments.

The "Dupe" Positioning

By this point, “dupe culture” wasn’t a side conversation in beauty. It was the conversation, especially for Gen Z and millennials who had grown up price-aware and marketing-skeptical.

Instead of tiptoeing around comparisons, e.l.f. leaned into them. The brand reframed affordability as savvy. You weren’t buying e.l.f. because you couldn’t afford something else—you were buying it because you could see through the markup.

That repositioning mattered. “Cheap” is a constraint. “Smart” is an identity. And e.l.f. increasingly became the brand you chose because you were paying attention.

Clean Beauty Without the Premium

e.l.f. also broadened what “accessible” meant. It wasn’t just price. It was access to the standards consumers were starting to demand—clean, cruelty-free, and vegan—without the premium pricing that often came with those claims. e.l.f. also became the first beauty company with a Fair Trade certified manufacturing facility.

In a market where “clean” had often been treated like an upscale add-on, e.l.f. made it feel normal. And that put competitors in a bind: brands built around thirty-dollar clean mascara couldn’t easily follow e.l.f. down to a six-dollar price point without breaking their own economics.

International Foundations

With the U.S. engine running, e.l.f. started laying the groundwork for the next leg of growth. The company opened an office in London earlier this year and focused first on markets where its proposition traveled well—especially Canada and the UK.

Those bets started showing early traction. The company said its overseas business in the United Kingdom and Canada grew 79% in Q1. The takeaway wasn’t just a strong quarter—it was proof that the “premium quality at accessible prices” story wasn’t uniquely American. And internationally, e.l.f. was still early.

Values Alignment with Gen Z

Underneath all of this was something easy to dismiss as “brand,” but hard to replicate: values that felt consistent with the business model. e.l.f. positioned itself as inclusive and values-driven, and for younger consumers, that mattered. They didn’t just want products that worked. They wanted to feel good about who they were buying from.

That kind of alignment deepened affinity. e.l.f. wasn’t just winning on performance-per-dollar. It was building a relationship—and in beauty, relationships are the closest thing to a moat you can get.

VIII. The Acquisition Strategy & Category Expansion (2019–Present)

As e.l.f.’s core business caught fire, management made a second bet: don’t just win in color cosmetics—build a broader beauty company. That meant using acquisitions and partnerships to add new categories, new capabilities, and new kinds of consumers without stretching the core e.l.f. brand until it snapped.

These moves are a window into how Tarang Amin and team think about the next act: e.l.f. not as one brand that has to be everything to everyone, but as a portfolio built to travel across price points and routines.

W3LL PEOPLE: Clean Beauty Credibility

In 2019, e.l.f. acquired W3LL PEOPLE, a clean beauty brand founded by makeup artist Shirley Pinkson. The value wasn’t scale. It was credibility. W3LL PEOPLE brought a more premium, clean-leaning positioning and formulations that complemented where e.l.f. was already headed.

e.l.f. had been moving toward cleaner products, but W3LL PEOPLE came with established legitimacy in a part of the market where trust and standards matter—and where consumers are often willing to pay more. It gave e.l.f. a way to participate in “clean” across a wider range of price points without forcing the core brand to suddenly speak with a different voice.

Naturium: The Skincare Entry

If W3LL PEOPLE expanded what e.l.f. could stand for, Naturium expanded what e.l.f. could sell.

The Naturium acquisition closed on October 4, 2023, and reflected Naturium’s contribution for about half of e.l.f. Beauty’s fiscal year. e.l.f. said the deal closed for “$333 million in a combination of cash and Company stock,” and that it “furthers the Company’s mission to make the best of beauty accessible to every eye, lip, face and skin concern.”

The strategic logic is straightforward: skincare is bigger than makeup, it’s been growing faster, and it tends to bring more repeat purchasing. It’s also where consumer routines have been shifting—toward a skincare-first mindset. Naturium arrived with what e.l.f. values most in a modern brand: products with momentum, social credibility, and a community that already knew how to talk about them online.

Amin has described more “white space” in skincare. Naturium was e.l.f.’s way of stepping into it quickly and credibly—competing across beauty categories instead of staying boxed into color cosmetics.

Keys Soulcare: The Alicia Keys Partnership

Then there’s Keys Soulcare, the brand built with Alicia Keys. This wasn’t a classic celebrity “face of the brand” arrangement. The positioning leaned into prestige and spiritual wellness, with Keys genuinely involved in product development and the brand vision.

Strategically, it also showed something important: e.l.f. could operate beyond its core price tier. Keys Soulcare sits at higher price points than e.l.f. Cosmetics, and that forced the organization to prove it could manage differentiation—multiple brand voices, multiple consumer expectations, all under one roof.

Strategic Logic: House of Brands

Put together, these deals point to a clear direction: e.l.f. is building a house of brands. Each addition brings a distinct positioning, a different consumer segment, or a capability that would be slow—or risky—to build organically.

That approach creates optionality. It also creates complexity. Running a portfolio is harder than running one rocket ship. Integration risk is real, and focus can blur if the organization doesn’t stay disciplined about what each brand is for.

e.l.f. has also said the acquisition of rhode will further strengthen and diversify its portfolio of fast-growing disruptive brands—another signal that the long-term plan is breadth, not just deeper penetration of the core.

Category Expansion Rationale

Skincare, in particular, explains why this portfolio strategy matters. As consumers prioritized skin health, skincare growth outpaced color cosmetics. It also generally offers higher margins and more frequent replenishment behavior than makeup—exactly the kind of fundamentals that can make growth more durable.

And early signs suggested the expansion was working. While the U.S. facial skin care sector grew 10% in fiscal Q1, e.l.f. Beauty said its facial skin care business grew 127%. The brand reportedly held a 1.5% share of facial skin care dollar share—still small, but meaningful as proof that e.l.f.’s “accessible quality” playbook could translate beyond cosmetics.

IX. Recent Inflection: Becoming a Major Player (2023–2024)

By 2023 and 2024, e.l.f. wasn’t just winning quarters. It was changing the leaderboard. The brand that started as a dollar-store disruptor had become the kind of company incumbents have to plan around.

The Market Share Moment

On an earnings call, CEO Tarang Amin put it plainly: “We passed both CoverGirl and Revlon for the No. 3 position in color cosmetics at 9.5% share. But if I look at our longest-standing national retailer, Target, we’re the clear No. 1 brand there with an 18% share. So I feel over the next few years, we have an opportunity to double our market share in color cosmetics.”

Passing Revlon and CoverGirl wasn’t just a headline. It was a signal that e.l.f.’s playbook—value-driven product, digital-native marketing, and fast iteration—could beat brands with decades of shelf dominance and enormous cumulative marketing spend.

Financial Performance

The financials matched the story. In Q4, sales rose to $321.1 million, up from $187.4 million a year earlier. For the full year, sales reached $1.02 billion, up 77%.

And this wasn’t growth at any cost. Profitability expanded too: net income grew to $127.7 million, up from $61.5 million in the prior-year period.

The company kept that momentum going as it scaled. In fiscal 2024, e.l.f. Beauty reported revenue of $1.31 billion, up 28.28% from $1.02 billion the year before—continuing to outpace the broader category.

Stock Performance and Investor Recognition

Public markets, which had once doubted whether “cheap makeup” could ever become a durable growth story, changed their minds in a big way. e.l.f. stock hit an all-time high intraday price of $221.83 on March 4, 2024, after having traded as low as $6.71 on February 27, 2019. The all-time high closing price was $218.00 on June 27, 2024.

Over the past year, the stock surged 216%. With that came a shift in who owned the story: institutional ownership increased as e.l.f. started getting treated less like a quirky disruptor and more like a legitimate, repeatable growth company.

Retailer Relationship Evolution

This is also where you could see e.l.f.’s relationships with retailers mature. The partnerships started to look less like a typical brand “supplying product” and more like strategic collaboration.

At Target—where e.l.f. held the number one position—the relationship included data sharing, exclusive launches, and joint planning designed to grow the category, not just the brand.

Ulta was another proof point. e.l.f. grew its business there by 80% in fiscal 2024, which Amin noted was “well above where the overall growth rates were.” That mattered because Ulta is a beauty specialist; winning there is different from winning in a mass aisle. It showed e.l.f. could translate its model beyond its original strongholds.

International Acceleration

Internationally, e.l.f. was moving from “early traction” to “real engine,” even if the base was still smaller. In Q2 fiscal 2025, the company posted 40% net sales growth, driven by market share gains in the U.S. and rapid growth overseas, including 91% international net sales growth.

On an analyst call, Amin added, “I think for the quarter, we grew international 115%, primarily off of our first 2 countries, Canada and the U.K., where we continue to increase rank.” The point wasn’t the exact rate—it was that the model was traveling, and the runway was still long.

Technology and Innovation

Even at this scale, e.l.f. kept behaving like a digital-native brand that assumed attention is earned, not bought. A Q4 collaboration with Liquid Death drove a triple-digit increase in traffic to e.l.f.’s website and generated 12 billion impressions.

And the company kept experimenting with how and where beauty shows up, including an Apple Vision Pro app and a partnership with Roblox. These weren’t side quests. They were consistent with the same underlying strategy e.l.f. had been refining for years: meet consumers where they are, build experiences that feel native, and keep the brand embedded in culture—not just in stores.

X. The Business Model Deep Dive: How e.l.f. Actually Works

To understand how e.l.f. makes money selling a six-dollar lipstick, you have to zoom in on the unit economics—and the deliberate choices that let the company keep prices low without turning the product into the thing it compromises.

The "Good Cost" Philosophy

At e.l.f., not all costs are created equal. The company draws a hard line between spending that makes the product better and spending that just makes the brand louder. More dollars go into formulation quality, ingredient sourcing, and manufacturing standards—the stuff you can actually feel when you put it on. Less goes into overhead that consumers don’t experience directly.

That’s a major break from traditional beauty, where marketing can swallow a huge chunk of revenue, often through TV advertising and celebrity endorsements. e.l.f. spends far less, putting its energy into digital channels where credibility is earned through creators, community, and repeatable engagement—not glossy production budgets.

That’s how e.l.f. can deliver strong gross margins while charging dramatically lower shelf prices. The advantage doesn’t come from making cheaper product. It comes from running a leaner machine around it.

Manufacturing and Supply Chain

e.l.f. doesn’t own factories. It uses contract manufacturing, working primarily with Asian suppliers that also produce for other beauty brands. That keeps the model asset-light and flexible: e.l.f. can scale without sinking capital into vertical integration.

The trade-off is exposure. When a meaningful portion of your goods are purchased from China, you benefit from cost and scale—but you also inherit geopolitical and tariff risk. e.l.f. can manage that tension, but it can’t make it disappear.

Operationally, the company has shown it can protect—and even expand—profitability. Gross margin rose about 50 basis points to 71%, driven mainly by favorable foreign exchange impacts on goods purchased from China and cost savings.

Retail Economics

About 80% of e.l.f.’s revenue comes from mass retail, with Target, Walmart, and Ulta as core partners. That distribution is a superpower—millions of shoppers see e.l.f. during normal trips, which is reach direct-to-consumer can’t touch.

But retail also comes with its own requirements: promotions, fixtures, inventory discipline, and constant competition for shelf space. You share economics with powerful partners, and you have to keep earning your spot. e.l.f.’s edge here is that it shows up with what retailers want most: velocity, newness, and a customer who’s already primed by social discovery.

Digital and Direct Channels

Digital sales grew 70% year over year and represented 22% of total sales. The direct channel tends to deliver higher margins and far richer consumer data, but it’s smaller than the retail engine—and e.l.f. uses it with intention.

DTC is where e.l.f. can launch new products, run limited editions, and build deeper relationships with its most engaged customers. It’s also where Beauty Squad lives most naturally—turning repeat buyers into a feedback loop that helps e.l.f. refine what it makes and how it talks about it.

Marketing Efficiency

e.l.f.’s marketing advantage is less about spend and more about fit. The brand leans into digital-first channels where authenticity matters: TikTok, creators, and community-driven content. Done well, that earns attention that traditional advertising can’t buy—and it tends to do it at a fraction of the cost.

And it compounds. Every product that performs creates another wave of content. Every satisfied customer becomes a credible messenger. Competitors can outspend e.l.f., but they can’t automatically manufacture the trust that makes this flywheel work.

Product Development Velocity

Legacy beauty often runs on long calendars—twelve to eighteen months from concept to shelf. e.l.f. moves faster, sometimes getting products to market in under six months.

That speed changes what the company can do. It can respond while a trend is still alive, not after it’s already peaked. It can iterate based on what consumers are saying in real time. And it can keep the brand feeling constantly fresh, which matters in a category where relevance decays quickly.

The downside is pressure: shorter timelines mean less room for mistakes. The upside is a pipeline that keeps the brand in the conversation.

Key Performance Indicators

If you’re tracking whether e.l.f.’s model is still working, two signals matter more than almost anything else:

U.S. Market Share Growth: The cleanest proof of competitive strength is whether e.l.f. keeps taking share in U.S. color cosmetics. In Q4, the company expanded market share by 325 basis points, marking 21 consecutive quarters of net sales and market share growth. Share gains are hard to fake; they’re the market voting for your value proposition.

Gross Margin Trajectory: e.l.f. isn’t winning by sacrificing profitability. Sustaining seventy-plus percent gross margins while growing fast is evidence that the value equation is structural, not promotional. Gross margin increased about 180 basis points to 71%, reinforcing that e.l.f. has been able to grow and expand profitability at the same time.

XI. Competitive Landscape & Strategic Positioning

e.l.f. competes in one of the most crowded, fastest-moving corners of consumer goods. The threats don’t come from one rival, but from every direction at once: global conglomerates with bottomless budgets, buzzy prestige brands that dominate conversation, legacy drugstore staples fighting for relevance, and international upstarts that can remix trends overnight.

The Incumbent Challenge

L'Oréal still leads the U.S. cosmetics market, which is valued at over $87 billion. And it hasn’t acted like a company defending a mature position. Last year, it spent $2.5 billion to acquire Aesop, adding yet another high-end brand to an already sprawling portfolio.

That’s the core dynamic e.l.f. lives with: the giants—L'Oréal, Estée Lauder, Coty—can outspend e.l.f. in marketing, outbid it in M&A, and outmuscle it in global distribution. They own prestige and mass brands, and they know how to use scale.

But they also have a built-in constraint that e.l.f. doesn’t. Competing at e.l.f.’s price points can be self-destructive. If you’re sitting on a portfolio full of fifteen-dollar products, launching a five-dollar alternative risks teaching your own customer that the markup was optional. It’s hard to win a price war when you’re the one with the most to lose.

That tension creates oxygen for a challenger whose whole identity is “premium results without the premium tax.”

Prestige Digital Natives

Then there are the brands that grew up in the same internet ecosystem—Glossier, Rare Beauty, and Fenty—but planted their flag in prestige pricing. They prove an important point: digital fluency and community aren’t exclusive to value brands. Plenty of companies can build buzz online.

The difference is what happens when you try to scale. Prestige has a smaller pool of everyday buyers, higher stakes per purchase, and often higher customer acquisition costs. And even the most online-native prestige brands eventually run into the same reality: to get truly big, you usually need major retail distribution.

e.l.f. plays a different game. By sitting in mass—while still showing up like a modern, creator-led brand—it gets to chase scale without waiting for consumers to “trade up.”

Mass Market Competition

In the aisles where e.l.f. actually wins, the competition is relentless. Maybelline and NYX (both owned by L'Oréal), plus Revlon and CoverGirl (Coty), have decades of awareness and deep relationships with retailers. Shelf space in mass isn’t a meritocracy; it’s a battlefield with history.

This is where Tarang Amin’s confidence becomes a real claim to be tested: “We've doubled our market share in the last three years, and I feel we can double our market share again over the next few years.” Momentum is real—but sustaining it means continuing to deliver newness, keep hero products in stock, and stay culturally relevant while everyone else tries to copy the playbook.

The K-Beauty and C-Beauty Factor

Korean and Chinese beauty brands have also reset consumer expectations—faster innovation cycles, fresh formulations, and pricing that makes experimentation easy. They’re both competition and a moving benchmark for what “good and affordable” should look like.

e.l.f. absorbs some of that pressure because it already sits at the intersection of value and trend. A shopper hunting for high-performing, low-commitment products might pick e.l.f. instead of ordering an imported brand.

But the broader takeaway cuts both ways: when quality affordable options multiply, differentiation gets harder. e.l.f. can’t just be inexpensive. It has to stay ahead on product and speed.

The Amazon Question

Finally, there’s Amazon—and the particular risk it poses to value brands. Amazon’s private label beauty offerings can use the platform’s data and distribution to spot what’s working and move quickly into the same white space.

e.l.f. has some insulation here. People often shop e.l.f. by name, not as a generic “primer” or “concealer” search, and the brand’s mass retail footprint helps keep it visible beyond a single online marketplace.

Still, Amazon can compete brutally on convenience and price. It’s not an existential threat today, but it’s one that never fully goes away—and it’s exactly the kind of pressure that forces a brand to keep earning loyalty, not assuming it.

XII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate-High

Beauty is one of those industries where it’s surprisingly easy to start and brutally hard to scale. You don’t need much capital to launch a cosmetics line, contract manufacturing is widely available, and social media gives you a way to reach customers without buying a single magazine ad.

But getting to meaningful market share is a different game. You need distribution in the places people actually buy—especially mass retail—and those relationships take time, proof, and consistency. You need awareness that doesn’t evaporate after one viral moment. And you need the operational muscle—quality, inventory, supply chain—to behave like a real brand, not a weekend project. That’s where e.l.f.’s infrastructure, brand equity, and long-built retail partnerships become real advantages that newcomers can’t replicate quickly.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low-Moderate

e.l.f. relies on contract manufacturers, and the good news is there are plenty of them—especially across Asia. The company also keeps its supplier base diversified, so it isn’t hostage to a single factory or partner.

The pandemic briefly reminded everyone that suppliers can gain leverage when components and capacity get tight. But those pressures were more about temporary disruption than a permanent shift in power. In normal conditions, e.l.f.’s scale is its leverage: manufacturers value steady, high-volume partners.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High

For consumers, switching costs in beauty are basically nonexistent. If you don’t like a mascara, you pick a different one next time. Loyalty is real, but it’s fragile—and the barrier to trying something new is usually just the price of one product.

Then there are the actual gatekeepers: retailers like Target, Walmart, and Ulta. They control access to enormous volumes of shoppers and can demand margin, promotions, and in-store support in exchange for shelf space. e.l.f. has to manage those partnerships carefully—getting the distribution it needs without letting retailer demands erode the economics.

The counterweight is e.l.f.’s direct relationship with customers, especially through Beauty Squad and its broader community. That doesn’t eliminate buyer power, but it does give e.l.f. more pull than a typical mass brand that’s purely dependent on the aisle.

Threat of Substitutes: High

In beauty, substitution is constant and multidirectional. Consumers can trade up or trade down between prestige and mass. They can swap brands with zero friction. They can even shift their spending from makeup to skincare, depending on the trend cycle and their routines.

And e.l.f.’s biggest cultural tailwind—dupe culture—cuts both ways. If e.l.f. can win by offering prestige-like performance at a lower price, someone else can try to undercut e.l.f. with an even cheaper alternative. The only real defense is staying ahead: keep innovating, keep earning attention, and keep building a brand people actively want to come back to.

Competitive Rivalry: Very High

This is an industry where everyone is fighting for the same two things: attention and shelf space. The major players are deep-pocketed, the field is crowded, and mass retail is aggressively promotional. Add in trend-driven demand—where a hero product can go from “must-have” to “marked down” fast—and the pressure never lets up.

e.l.f. competes by moving quickly, staying digitally fluent, and maintaining real brand affinity. But those are living advantages, not permanent ones. They have to be renewed over and over, product launch after product launch, platform shift after platform shift.

XIII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Moderate and Growing

As e.l.f. gets bigger, it gets more leverage in the places that matter: distribution, marketing efficiency, and operations. Higher volumes can translate into better retailer terms. Digital capabilities and infrastructure investments get spread across a larger revenue base. And the company’s systems—from planning to supply chain—tend to improve as they’re exercised at scale.

What e.l.f. doesn’t have is the classic manufacturing scale advantage. It’s still outsourcing production to contract manufacturers that serve multiple brands, which means the scale benefits are mostly operational, not production-based.

Network Effects: Weak but Emerging

Beauty Squad creates a small but real flywheel: more members means more reviews, more feedback, more community energy, and more social proof—especially online, where people buy what they see other people using.

But e.l.f. isn’t a platform business, and these effects are limited. User-generated content can help, but competitors can also generate UGC if they build the right products and community. So this is an advantage—just not an unassailable one.

Counter-Positioning: Strong (Historically)

This was e.l.f.’s original superpower. The incumbents were boxed in. They couldn’t match e.l.f.’s pricing without undermining their own economics—especially in prestige. And for years, e.l.f.’s digital-first approach looked alien to organizations optimized for TV ads and department-store counters.

The issue is that counter-positioning doesn’t last forever. L’Oréal’s acquisition of NYX was one sign the giants were willing to compete harder in “affordable.” And over time, digital marketing stopped being exotic—it became table stakes. So the advantage that once gave e.l.f. oxygen has narrowed, even if it still matters at the margin.

Switching Costs: Weak

Switching costs in cosmetics are close to zero. If a mascara disappoints, you swap it out the next time you’re in Target—no contracts, no friction.

e.l.f.’s loyalty program adds a bit of stickiness through rewards and perks. Familiarity helps too: once someone finds a shade or routine that works, they’re less likely to stray. But these are helpful nudges, not a true lock-in.

Branding: Moderate and Strengthening

e.l.f.’s brand is getting stronger, especially with Gen Z and millennials. The positioning—accessible, cruelty-free, inclusive, and culturally fluent—has become part of why people buy, not just what they buy.

It’s not prestige-level brand power, where consumers will pay more and forgive more. If e.l.f. stumbles on quality or relevance, plenty of shoppers will happily try the next hot thing. Still, brand strength is clearly compounding through consistent product hits and a voice that feels authentic online.

Cornered Resource: Weak

e.l.f. doesn’t have proprietary technology, exclusive ingredients, or anything else competitors can’t theoretically access. The closest thing to a cornered resource is shelf space: every four feet of e.l.f. on a planogram is four feet someone else doesn’t get.

But shelf space isn’t owned—it’s rented through performance. If velocity slows, retailers will reallocate that space quickly. And while Tarang Amin and the leadership team have been hugely important, the advantage here is less about irreplaceable individuals and more about the organization’s accumulated capabilities.

Process Power: Moderate and Growing

This is where e.l.f. looks most defensible. The company’s ability to move quickly—spotting trends, developing products fast, marketing them in a platform-native way, and learning from real-time feedback—adds up to process advantage.

None of it is a secret formula. It’s the result of years of building muscle in product development velocity, data-driven decision making, digital marketing, and community management. Competitors can copy pieces, but replicating the whole operating cadence takes time.

Overall Power Assessment

e.l.f.’s powers are real, but they’re not permanent fortresses. The company’s biggest historical advantage—counter-positioning—has weakened as incumbents adapt. The strengths that are growing now are brand and process: trust with younger consumers, and an operating system built for speed and digital discovery.

The flip side is clear too. Without strong structural moats, e.l.f. doesn’t get to coast. The upside is that great execution compounds. The risk is that execution stumbles can show up fast—in market share, on shelves, and in culture.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

Generational Brand Loyalty: Gen Z and millennial consumers who found e.l.f. early—when they were learning how to do makeup, watching tutorials, and figuring out what products actually worked—may stick with the brand as their incomes rise. If that community-driven bond holds, e.l.f. doesn’t just get repeat purchases; it earns decades of lifetime value.

International Runway: Tarang Amin has said the company is still in the “early innings,” with plenty of room left in cosmetics, skin care, and international markets. Today, international revenue is still a small slice of the whole, which is exactly why investors see upside: if the value proposition travels, the runway is long.

Category Extension Opportunity: Skincare traction suggests e.l.f. can take its playbook beyond color cosmetics. Hair care, fragrance, and adjacent beauty categories are obvious candidates for expansion—new pools of demand where the same “high performance, accessible price” idea could work.

Digital and Data Advantages: e.l.f. has spent years building the muscles that matter in modern beauty: engaging consumers where they live, spotting trends early, and moving from insight to shelf quickly. Those capabilities get stronger with repetition—and with more data flowing in from community feedback and digital channels.

Retail Partnership Depth: e.l.f.’s distribution isn’t just broad; it’s embedded. Target, Walmart, and Ulta aren’t easy shelves to earn, and they’re even harder to keep. As Amin pointed out, “We’re the clear No. 1 brand at Target with an 18% share.” Leading positions like that create practical advantages—visibility, collaboration, and staying power—that a new entrant can’t replicate overnight.

Management Track Record: Amin and team have already delivered the kind of consistency the public markets demand. As he put it, “Fiscal 2024 marked our strongest year of net sales growth on record, a continuation of the exceptional, consistent, category-leading growth we’ve delivered.” In a category known for boom-and-bust brands, that track record matters.

Premiumization Potential: There’s also a world where e.l.f. expands upward without abandoning its base—using acquisitions or carefully tiered product lines to reach higher price points. If the company can do that without breaking trust, it opens the door to richer margins while keeping the volume engine intact.

The Bear Case

Brand Heat Risk: Beauty runs on attention, and attention moves. Revlon and CoverGirl were once dominant; their declines are a reminder that cosmetics leadership isn’t permanent. If e.l.f. stops feeling culturally current—or stops shipping hits—momentum can reverse faster than investors want to believe.

Low Barriers to Entry: It’s never been easier to start a beauty brand. Social platforms can create awareness quickly, and contract manufacturers make production accessible. That means competition doesn’t just come from the giants; it can come from anywhere, at any time.

Retail Dependence: e.l.f. still relies heavily on retail partners, with approximately 84% of net sales coming through the retail channel. That scale is a strength until it isn’t. If a key retailer changes terms, shifts shelf space, or prioritizes a competitor, e.l.f. feels it immediately.

Manufacturing and Tariff Exposure: The supply chain brings its own set of risks. With manufacturing concentrated in Asia—primarily China—e.l.f. is exposed to tariffs, geopolitical tension, and disruption. The pandemic highlighted how quickly those issues can turn from theoretical to operational.

Limited Pricing Power: e.l.f.’s biggest brand strength is also a constraint. “Affordable” limits how much pricing the company can push through when costs rise. If inflation, freight, or inputs move faster than e.l.f. can offset, margins get squeezed—and the brand can’t simply “price like prestige” without undermining its promise.

International Execution Risk: Expanding abroad isn’t just translating packaging. It means navigating new retailers, different regulations, and local consumer preferences. Success in the U.S. doesn’t guarantee success elsewhere, and international expansion requires investment that could otherwise be deployed in the core business.

TikTok Algorithm Risk: e.l.f.’s marketing edge depends heavily on platforms it doesn’t control. A change in TikTok’s algorithm—or any major social platform’s distribution mechanics—could reduce organic reach and force e.l.f. into more paid marketing, weakening the efficiency that has been such a key advantage.

Valuation Expectations: With a trailing P/E of nearly 57, the market is pricing in a lot of future perfection. If growth slows, even modestly, the multiple can compress at the same time earnings disappoint—creating a double hit to the stock.

What to Watch

Market Share Trajectory: The company has delivered 23 consecutive quarters of market share gains. That’s one of the clearest indicators that the model is still working. A quarter of share loss wouldn’t be fatal, but it would be a meaningful warning sign.

Gross Margin Sustainability: Seventy-plus percent gross margins while scaling quickly is a big part of the bull thesis. If margins start sliding, it could signal rising costs, heavier promotions, or intensifying competition.

International Revenue Mix: Watch whether international becomes a larger piece of the business over time. A rising mix would validate the global runway story; a flat mix would suggest expansion is harder—or slower—than it looks on paper.

XV. Lessons & Takeaways: The Playbook

e.l.f.’s rise—from a dollar cosmetics upstart to a modern category leader—reads like a beauty story on the surface. But underneath, it’s a disruption playbook for almost any consumer category where price, distribution, and marketing habits have calcified over time.

Democratization as Strategy

The most durable disruptors don’t just undercut price. They pull something “premium” out of a gated world and make it normal.

That’s what e.l.f. did. It didn’t win by selling makeup that happened to be cheaper. It won by proving that premium performance and accessible pricing could coexist—and by making that feel obvious once you experienced it.

The broader lesson is uncomfortable for incumbents: in a lot of categories, “premium” pricing is less about cost and more about inertia. If a challenger can strip away what doesn’t improve the product and still deliver results, it can open up a much bigger market than anyone thought was available.

Digital-Native Advantage

e.l.f.’s dominance on platforms like TikTok wasn’t luck and it wasn’t a one-off viral moment. It was the output of years spent learning how people actually discover products now: through creators, comments, tutorials, and remixable content that feels like culture, not advertising.

Incumbents built for TV and glossy campaigns often struggle in environments that reward authenticity over production value. That gap creates asymmetric opportunity for brands that are native to digital attention—and know how to earn it instead of buying it.

Community Over Advertising

Paid awareness fades. Community compounds.

e.l.f. didn’t just build customers; it built participants. Members make up about 80% of sales on elfcosmetics.com, and that matters because those buyers aren’t only purchasing. They’re reviewing, recommending, creating content, and feeding back into what the company makes next.

That kind of advantage takes time. It can’t be shortcut with spend, because the whole point is trust. But once it exists, it’s hard for an advertising-dependent competitor to replicate quickly—no matter how big their budget is.

Speed as Competitive Weapon

In fashion-driven categories, the winner isn’t the company with the perfect plan. It’s the company that can move while the moment is still alive.

e.l.f.’s ability to develop and launch products faster than slower-moving competitors lets it capture trends, iterate in public, and stay relevant in real time. That speed doesn’t come from one clever process. It comes from organizational choices: fewer layers, empowered teams, faster approvals, and a culture that tolerates imperfection in exchange for learning.

Counter-Positioning’s Expiration Date

For a long time, e.l.f. benefited from classic counter-positioning: incumbents couldn’t match its value proposition without undermining their own pricing logic.

But that kind of protection doesn’t last forever. Big players adapt, copy, acquire, and reposition. New entrants show up without legacy baggage. The lesson is that counter-positioning buys time—but sustained success requires building new advantages before the old one fades.

Amin has stayed confident even as competition intensifies, saying e.l.f. Beauty is “in early innings unlocking the full potential for our brands.” The subtext is clear: the company is playing offense, not defending a one-time trick.

Omnichannel Reality

Beauty is not a category where “digital only” scales cleanly. e.l.f.’s evolution—from online-only to omnichannel—shows what the best operators eventually accept: ideology doesn’t beat category dynamics.

Retail delivers reach and credibility that owned channels can’t replicate on their own. The winners don’t pick a side. They build a system where digital drives discovery and retail turns that discovery into volume—then use direct channels to deepen the relationship.

Data as Differentiator

In modern beauty, data is less about dashboards and more about reflexes.

Real-time signals from social listening, community feedback, and digital engagement are faster—and often more honest—than traditional research. e.l.f. used those signals to shape product development, optimize marketing, and spot trends early. The advantage isn’t access to data; everyone has data. The advantage is having the muscle to act on it quickly and consistently.

The Importance of Leadership

Finally, e.l.f.’s story is a reminder that strategy needs an operator.

Tarang Amin’s impact wasn’t that he discovered the company’s potential—it was already there. His contribution was turning that potential into repeatable execution: sharper focus, better infrastructure, tighter retail strategy, and a digital-first mindset applied with real discipline. In the right moment, the right leadership doesn’t change the mission. It makes the mission scalable.

XVI. Epilogue & The Future

As e.l.f. looks out over the next decade, it runs into the problem every great disruptor eventually earns: once you’ve won, the game changes. The question stops being “can this work?” and becomes “can this keep working as the organization gets bigger, broader, and harder to steer?”

The Path to Ten Billion

Tarang Amin has been clear about the kind of performance e.l.f. believes it can sustain. As he put it: "In this dynamic environment, we continue to deliver industry-leading results. In Fiscal 2025, we grew net sales 28%, gained 190 basis points of market share in the U.S. and continued our international expansion strategy."

If you’re sketching a path from today’s scale to something like ten billion dollars in revenue, the roadmap is pretty straightforward—and pretty demanding. It would mean continuing to take share in U.S. cosmetics, turning international expansion from “early innings” into a real second engine, and pushing further into adjacent categories like skincare, hair care, and potentially fragrance. It may also mean more acquisitions that add new brands and new consumer segments without diluting what makes e.l.f. work.

Plausible? Yes. Guaranteed? Not even close. Each of those levers comes with execution risk, and in beauty, the competitive landscape doesn’t pause while you build.

Independence or Acquisition Target?

At this point, e.l.f.’s success naturally invites the “who buys them?” conversation. Companies like L'Oréal, Estée Lauder, Unilever, and P&G all have the balance sheets and the strategic logic to want a brand with proven growth, digital-native marketing strength, and real credibility with younger consumers.

But there’s another force pointing the other direction: e.l.f. has been acting like an acquirer, not a target. The recent acquisition of rhode reinforces that posture—building a portfolio rather than selling the platform. Still, public-company reality applies here, too: if an offer shows up that truly serves shareholder interests, the board and management have a fiduciary duty to take it seriously.

The Next Generation

Then there’s the hardest question of all: what happens when Gen Alpha becomes the next wave of beauty consumers?

Will e.l.f.’s positioning resonate with a cohort that has never known a pre-digital world? Will TikTok still be the center of gravity, or will the attention map shift again to platforms and formats that demand a new playbook?

e.l.f.’s history suggests it knows how to adapt. But relevance across generational transitions is the ultimate stress test. Plenty of brands win one era. Very few keep winning the next.

Technology Integration

Beauty is also heading into a more tech-driven phase: AI-powered personalization, virtual try-on, and augmented reality experiences that change how people discover and buy products. e.l.f. has already shown a willingness to experiment here, from Apple Vision Pro apps to Roblox partnerships.

The point isn’t that any single initiative is make-or-break. It’s that e.l.f. is structurally comfortable with experimentation—meeting consumers where they are, learning fast, and iterating in public. If the next big shift in beauty commerce comes through technology, that mindset matters.

The Democratization Legacy

And finally, zoom out from strategy and stock charts to why e.l.f.’s story has stuck in the first place.

e.l.f. proved something the industry had treated as almost impossible: you can offer accessible pricing without treating quality as optional. You can build a profitable business by expanding access, not by protecting a markup. In a moment when people increasingly question whether business creates real value or just extracts it, e.l.f. is a case study in disruption that opened the doors wider.