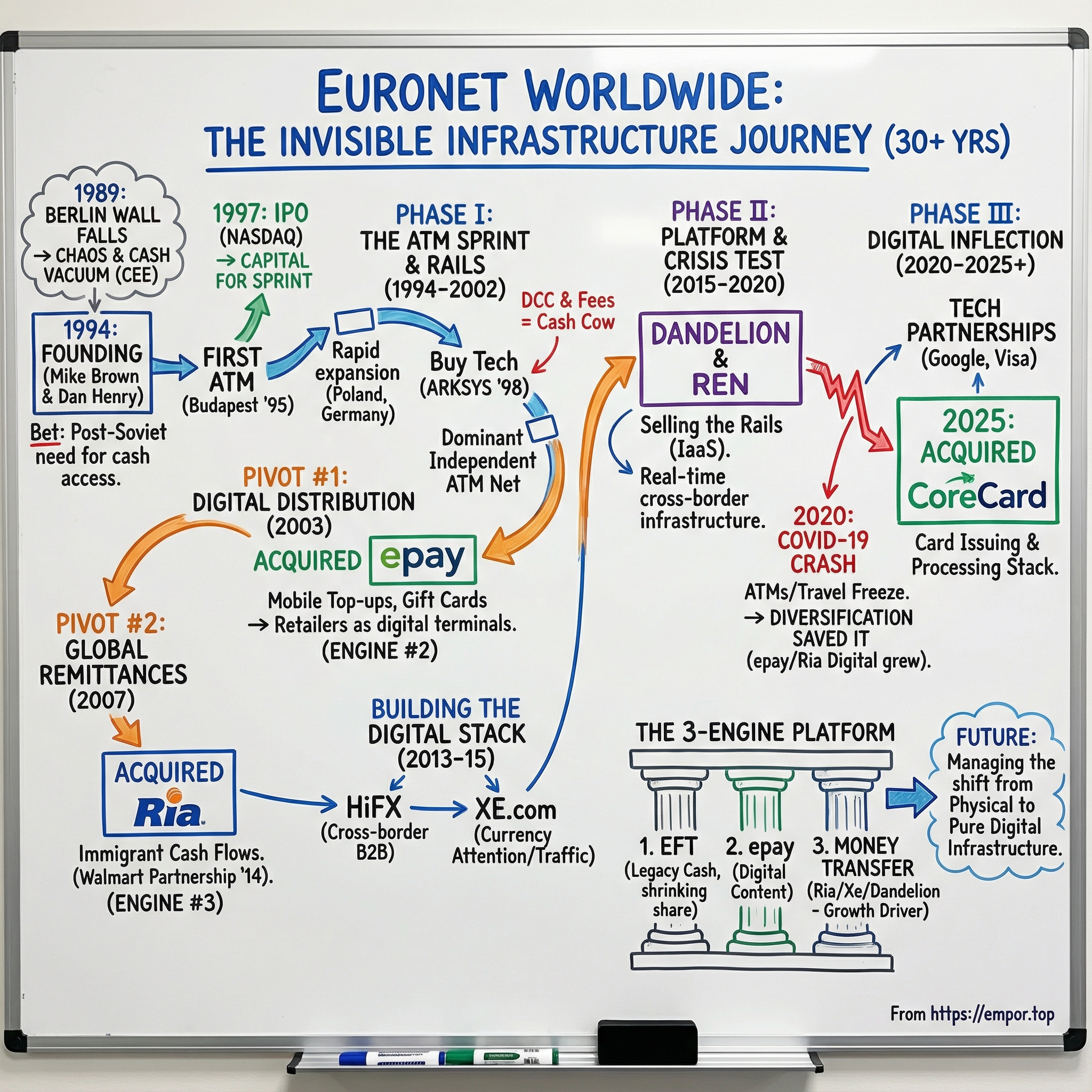

Euronet Worldwide: Building the Invisible Infrastructure of Global Payments

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a cold December evening in 2024.

Somewhere in Eastern Europe, a migrant worker taps her phone and sends money home. In Barcelona, a tourist pulls euros from a bright orange ATM just off La Rambla. In Germany, a teenager buys a digital gaming gift card at a convenience store. In Australia, a small business owner checks a currency conversion app before wiring a supplier overseas.

Four moments, four countries, four different products. One invisible common thread: the transaction rails run through a company most of them have never heard of, Euronet Worldwide.

Euronet is a Kansas-based fintech that, by late 2025, was generating more than $1.1 billion in quarterly revenue. It operated with roughly 11,000 employees across 67 offices, and its payments footprint stretched across about 200 countries and territories. In 2024, total revenue reached $3,989.8 million, up 8% year over year. Yet for something that touches billions of transactions, Euronet has stayed almost completely out of the spotlight.

Which is exactly what makes the story so good.

How did two brothers-in-law, taking a bet on post-Soviet ATMs in the early 1990s, end up building a global payments empire, one that now powers remittances for immigrants, distributes prepaid mobile top-ups across continents, and helps run one of the world’s largest real-time cross-border payment platforms?

The answer is a three-decade sprint through unglamorous infrastructure: spotting gaps no one else wanted to fill, buying the right assets at the right moments, and surviving the industry’s most dangerous shift, from cash and terminals to apps and instant payments. Mike Brown co-founded Euronet in 1994 and has led it ever since, as CEO, chairman, and president, one of the longest founder-led runs in fintech.

If you’re an investor or builder, this is a masterclass in how network businesses actually get built in financial services, how disciplined M&A can substitute for years of organic grind, and how to operate in emerging markets where the rules, the rails, and the risk all change fast. It’s also a warning: legacy infrastructure can be a fortress, until the world stops needing it.

From 2019 to 2024, Euronet’s revenue jumped 45%, from $2.8 billion to about $4 billion. Over that same stretch, ATM network revenue shrank as a share of the total, from 25% to 19%, even as it still grew in absolute dollars. The company is in the middle of a real transformation, and the ending isn’t written yet.

So let’s start at the beginning, in the chaos and opportunity that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall.

II. Founding Context: The Fall of the Berlin Wall & The Payments Vacuum (1989-1994)

November 9, 1989. The Berlin Wall came down, and almost overnight, hundreds of millions of people across Central and Eastern Europe were pushed into a crash course in market capitalism.

There was just one problem: the plumbing didn’t exist.

Banks were outdated. Card networks were thin. Cash was still king, but getting cash was a logistical mess. ATMs, the most ordinary thing in the West, were still basically a novelty—something you’d seen on Western TV, not something you’d relied on in your own neighborhood.

Most people looked at that gap and saw risk. Mike Brown and Dan Henry saw a business.

They were brothers-in-law from Kansas City, and in 1994 they founded what would become Euronet on a simple conviction: if the region was going to modernize, it would need access points to money. And if the banks couldn’t—or wouldn’t—build those access points themselves, an independent operator could.

Brown wasn’t coming in naïve. He had decades of experience in software and electronic payments. In 1979 he founded Innovative Software, building integrated business software for personal computers. In 1988, Innovative Software merged with Informix, a major database software company. At Informix, Brown went on to serve as president and chief operating officer, and also led its workstation products division. In 1993, he became a founding investor in Visual Tools, which developed and marketed component software. He’d built companies, shipped product, and operated at scale.

So when Brown decided in 1994 that he wanted to make cash more accessible around the world, it wasn’t a moonshot. It was a calculated move. With $4 million, he founded Euronet Worldwide, Inc., and planted the flag where the need was urgent and the competition was scared: Budapest, Hungary.

The premise was straightforward, even if the execution wasn’t. Post-communist countries needed modern financial infrastructure fast. Local banks didn’t have the capital, experience, or appetite to roll out ATM fleets and maintain them. Western banks viewed the region as unstable. That left a vacuum.

Euronet stepped into it by installing the first independent, non-bank-owned ATM network in Central Europe.

This was “picks and shovels” thinking applied to finance. Euronet wasn’t trying to become a bank. It wasn’t trying to win consumers with a shiny brand. It was building the rails everyone else would have to ride—the pipes that made the new economy usable day to day.

That positioning would prove durable for decades. Because as new banks opened, retailers expanded, and consumers demanded basic convenience, they all needed the same thing: reliable access to cash.

And now, with the first machines in the ground, the stage was set for Euronet’s next move: expanding that network as fast as the region was changing.

III. The ATM Network Play: Rapid European Expansion (1994-2002)

Euronet started in Hungary, and in 1995 it installed its first ATM in Budapest. One machine doesn’t sound like much. But in that moment, it wasn’t a cash box. It was a demonstration that the model worked: a non-bank company could plant infrastructure in the middle of a newly opened economy and get paid every time someone needed money.

From there, the playbook was simple: expand fast and lock in the best locations before anyone else did. Euronet began with a few hundred ATMs and pushed outward across Central Europe with real urgency. Post-communist Europe was modernizing in real time, and Brown and Henry knew the window wouldn’t stay wide open. Once the big Western banks got serious about the region, the easy territory would be gone.

The economics made the sprint worth it. Every withdrawal generated revenue, and independent operators could stack multiple streams on the same transaction: fees from cardholders, interchange from the issuing banks, and surcharges when a customer used a card from another institution. Meanwhile, banks were often relieved to let someone else do the messy, capital-heavy work of deploying and running machines. ATMs required hardware procurement, constant maintenance, cash logistics, physical security, software updates, and 24/7 uptime. That’s operations, not banking. Euronet was built to specialize in exactly that.

Then came the turbocharger.

On December 15, 1997, Euronet went public on NASDAQ, raising about $53 million. For a company that was only a few years old—and operating in markets most U.S. investors still thought of as unstable—that was a major milestone. The IPO didn’t change the strategy; it funded it.

Expansion had already started. By 1996, Euronet was moving beyond Hungary into other European countries. In 1997 it entered Poland, which would become one of its most important markets. And the company wasn’t just laying down more machines; it was quietly building the capabilities to control more of the stack.

That showed up clearly in 1998, when Euronet bought ARKSYS, a software company focused on electronic payment and transaction delivery systems. This wasn’t about buying revenue. It was about buying leverage. ARKSYS gave Euronet more in-house technology muscle, making it less dependent on third-party systems and more capable of building proprietary payments infrastructure—a theme that would repeat across the next two decades.

Geography kept widening. By 2000, Euronet had entered Greece and made a notable leap into Asia with Indonesia. In August 2001, it renamed itself from Euronet Services to Euronet Worldwide—less a branding exercise than a statement of intent. This was no longer a Central European ATM story. It was an emerging-markets infrastructure story.

In August 2002, Euronet made another big bet: India, through an outsourcing agreement for 450 ATMs. India would become enormous, but it was also different. Transaction growth could outpace revenue growth because the country produced huge volumes of smaller withdrawals. It was a preview of a pattern Euronet would learn to love: scale first, then efficiency.

And inside the ATM business, Euronet found a profit lever that went beyond the basic withdrawal: dynamic currency conversion, or DCC. For international cardholders, DCC let the ATM display the withdrawal in the customer’s home currency at the moment of the transaction. The margins on DCC were richer than standard fees, and Euronet leaned into it hard as its network became more tourist-heavy and cross-border travel grew.

By the early 2000s, Euronet had become the dominant independent ATM operator across Central and Eastern Europe, and one of the largest independent networks on the continent. It had done exactly what it set out to do: build the cash access rails that banks didn’t want to build themselves.

But Brown could see the next problem coming. ATMs were a great engine—but not an infinite one. If Euronet wanted to keep compounding, it needed a second act.

It found it in an unexpected product that was exploding across the same emerging markets Euronet already understood: prepaid mobile phone top-ups.

IV. Strategic Pivot #1: The epay Acquisition & Digital Distribution (2003)

In the early 2000s, another kind of payments revolution was spreading through the same markets where Euronet’s ATMs were taking off. Mobile phones were finally cheap enough for everyone. But the way people paid for them didn’t look like the West. There were no tidy monthly plans. People bought prepaid airtime, over and over, in tiny increments, from whatever shop was closest.

Mike Brown immediately recognized the pattern. This was the ATM business all over again: a fragmented retail landscape, tons of small transactions, and a huge market hiding in plain sight. If Euronet could build the infrastructure that made cash usable, it could also build the infrastructure that made digital value—starting with airtime—available everywhere.

So in February 2003, Euronet bought e-pay, Ltd., an electronic payments processor for prepaid mobile airtime top-ups in the U.K. and Australia. That single deal didn’t just add a product line. It gave Euronet a new machine: a way to connect major brands to everyday retail counters through software, settlement, and distribution. And Euronet didn’t stop there. Later that year, it expanded the footprint with the September 2003 purchase of Austin International Marketing and Investments, Inc. (AIM) in the U.S., followed by the November 2003 acquisition of Germany’s transact Elektronische Zahlungssysteme GmbH.

The shift was subtle but huge. Euronet wasn’t “just” running ATMs anymore. It was building a retail distribution network for digital goods, delivered through point-of-sale terminals in stores around the world. In Germany, it partnered with major mobile operators and rolled out top-ups across more than 18,000 stores—proof that this wasn’t a niche service. It could scale fast.

The underlying insight was even better. Prepaid airtime worked because it matched the reality of how people earned money. If you didn’t have a bank account or a credit card, you could still buy phone credit the moment you had cash, in an amount you could afford. What made that possible wasn’t marketing. It was infrastructure: the terminals, the retailer relationships, the software, the reconciliation. This was exactly Euronet’s kind of problem.

Over time, epay became a global prepaid product provider and distribution network, with approximately 728,000 points of sale across about 339,000 retail locations in markets including Australia, Brazil, China, France, Germany, Greece, India, Italy, New Zealand, Poland, Romania, Russia, Spain, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

And airtime was only the wedge. The platform expanded into gift cards, gaming content, digital media, and other prepaid products. Eventually, digital media content grew into a major driver, representing 66% of epay’s revenue—an extraordinary evolution from “top up your phone at the corner store.”

You can see that progression in deals like the one signed in September 2020, when epay entered an agreement with Microsoft to manage monthly recurring billing for select retailers in the mobile gaming market. That’s a long way from airtime vouchers. It’s recurring billing and digital distribution at scale.

Financially, epay kept becoming a bigger pillar. The segment delivered $267.4 million in revenue in Q1 2025, up 4% year over year. For full-year 2024, epay reached $1,150.5 million, a 6% increase from 2023.

Strategically, this was the point. epay gave Euronet a second engine, one not tied to how often people walked up to an ATM. When cash usage dipped—whether from long-term cashless trends or sudden shocks like COVID lockdowns—this business helped keep the whole company steady. And when digital content boomed, epay was positioned to ride the wave.

It also put Mike Brown’s acquisition philosophy in neon lights: buy infrastructure and distribution, not just technology. e-pay brought the network—retail reach, operator relationships, and working processing rails. Those were the hard parts. Software could always be upgraded.

And with ATMs on one side and prepaid distribution on the other, Euronet was now something more than an ATM operator. It had built two different ways to move value through everyday commerce.

Next, Brown would go after a third—and it would take Euronet from behind-the-scenes plumbing into the center of one of the biggest financial flows on Earth: cross-border remittances.

V. Strategic Pivot #2: The Ria Acquisition & Money Transfer (2007)

In 2007, Euronet bought Ria Money Transfer, a global remittance company with a network of agents and company-owned stores across North America, the Caribbean, Europe, and Asia. If epay had given Euronet a second engine, Ria gave it a whole new category—and it turned out to be the most consequential acquisition Euronet ever made.

The bet paid off. Since Euronet purchased Ria, the money transfer division’s operating income has grown at a 25% compounded annual rate. That kind of compounding doesn’t happen in payments by accident. It happens when you plug into a flow that’s both massive and durable.

Remittances are exactly that. Immigrants earn money in developed economies and send it back to families in developing ones—rent, school fees, medical bills, basic living expenses. The World Bank has estimated global remittances at more than $800 billion a year, a financial lifeline measured not in headlines, but in household budgets.

There was one obvious problem: this industry already had a king. Western Union had spent about 170 years building the brand and the footprint, with more than 500,000 agent locations worldwide. On paper, it looked untouchable. And Euronet, at the time, was still best known for ATMs.

So Euronet and Ria played the underdog game on purpose. They went after emerging corridors where Western Union wasn’t as deeply entrenched. They built distribution through retail agent networks where immigrant customers already were. They competed hard on price against higher-cost providers. And they invested in payout reliability in the receiving countries, because in remittances, “it arrived” matters more than “it was slick.”

Under Mike Brown, Ria expanded its cash pickup footprint dramatically, then pushed aggressively into digital in more recent years. The result was a network with roughly 638,000 cash pickup locations, plus connections to around 7.5 billion digital wallet and bank accounts. That scale helped make Ria the second-largest money remittance company in the world.

A major accelerant arrived in April 2014: Walmart. The retailer launched a store-to-store money transfer service with Ria, called Walmart2Walmart, letting shoppers move money between more than 4,000 Walmart stores across the U.S. In 2016, that offering expanded internationally with Walmart2World.

For Ria, this wasn’t just a nice partnership. It was distribution at American scale, dropped directly into the weekly routines of the exact customer base remittances depend on. It also signaled to the market that Ria could handle big volumes, big partners, and big operational expectations—credibility that tends to compound into more deals.

In June 2015, Ria widened its reach again by entering the Middle East remittance market through the acquisition of IME. That mattered because the Gulf is a critical remittance corridor, sending money to South Asia and Africa at enormous volume.

The real strategic win, though, was the model: keep serving cash-to-cash customers who still lived in a cash world, while building digital rails for customers who didn’t. Euronet priced Ria’s digital service below the industry average in several U.S. outbound corridors. And interestingly, even some digital-native remittance brands—including Sendwave, Xoom, and Remitly—have leveraged Euronet’s global distribution network and agents for payouts in certain geographies. In 2024, Euronet’s digital money transfer business grew transactions by more than 30%, and by year-end, 54% of payout volume was digital.

In the broader market, one distribution estimate put Western Union at 12% share, with Remitly at 4%, and Intermex, MoneyGram, and Ria at 3% each. Ria’s slice might look modest in that snapshot, but inside Euronet, money transfer became the biggest revenue contributor and the fastest-growing line of business.

The Ria acquisition also perfectly fit Brown’s core pattern: build infrastructure that gets stronger as it grows. Every new agent location made the network more useful. Every new payout option made the product more competitive. And once that flywheel starts spinning, it doesn’t just drive volume—it makes the whole platform harder to replace.

VI. Building the Digital Money Transfer Stack (2013-2015)

By 2013, the remittance market was starting to tilt. Digital-native startups like TransferWise (now Wise) and Remitly were showing customers something the legacy players hadn’t prioritized: an app-first experience, clearer pricing, and fewer trips to a storefront.

Euronet could see where this was going. Ria had the physical network. But if the future of remittances was going to live on phones, Euronet needed a digital stack fast. True to Mike Brown’s style, it didn’t try to invent everything from scratch. It went shopping.

First came Pure Commerce in 2013, which gave Euronet access to a suite of SaaS-based applications. The point wasn’t flashy branding. It was capability: cloud-based technology that could support a more modern, digital-forward platform.

Then, in May 2014, Euronet bought HiFX, a U.K.-based international payments provider with a cross-border business in the U.K., Australia, and New Zealand. HiFX expanded the mission beyond classic remittances. It served higher-income consumers and small-to-medium businesses moving larger amounts across borders. In other words: different customers, different use cases, and a step toward higher-margin, more service-heavy payments.

But the real watershed moment came in July 2015, when Euronet acquired XE, the currency site almost everyone has used at some point, even if they don’t remember the name. XE was a global leader in foreign exchange information, fulfilling more than 2.9 billion annual requests. Across XE.com and x-rates.com, it drew over 1.6 billion page views from more than 200 million unique visitors each year, and its mobile app had more than 35 million downloads and three billion rate requests.

Euronet acquired XE.com Inc. on July 2, 2015 for approximately $120 million, paying $79.9 million in cash and issuing 0.32 million shares of common stock at closing.

The scale mattered because attention is distribution. XE’s traffic consistently ranked it among the top 500 global websites, comparable to brands like Reuters, Samsung, and The Wall Street Journal. It also ranked as one of the top five business news sites globally.

Brown was unusually blunt about why this deal mattered. “Building a brand and generating high quality traffic to your digital properties require some of the heaviest investment when constructing a digital business,” he said. XE had already made that investment, becoming “the world’s top currency site,” serving more than 200 million unique visitors annually—49% of whom, according to an XE user poll, had a payment need.

That’s the play in one line: buy the traffic instead of trying to earn it.

XE had spent more than two decades becoming a trusted front door for people thinking about currency. Euronet could now connect that front door to two things it already had: Ria’s payout network on the back end, and HiFX’s cross-border payments capabilities for customers who weren’t just sending money home, but paying suppliers and moving business funds too.

A few years later, in December 2018, Xe merged with its sister company HiFX, and the combined business continued under the Xe brand. The result was a single, digital-first money transfer identity that could serve both consumers and businesses.

Zooming out, the logic is clean. Pure Commerce helped modernize the underlying technology. HiFX brought a broader payments product and a new customer segment. XE brought a global audience at the exact moment they were already thinking about FX. Combined with Ria’s physical footprint, Euronet had assembled a hybrid model: cash when customers needed it, digital when customers wanted it, and a funnel of intent at the very top.

VII. The Dandelion Network: Building Cross-Border Real-Time Payments Infrastructure (2015-2020)

By the mid-2010s, Euronet had assembled something rare: consumer brands on the front end, and a sprawling payout engine on the back end. Ria and Xe were the faces customers interacted with. But Mike Brown saw the bigger prize one layer down.

If Euronet could move money across borders for its own brands, why not sell that capability to everyone else?

That idea became Dandelion. In November 2021, Euronet made it public, launching Dandelion as a cross-border payments platform designed so fintechs, banks, ERPs, and tech platforms could build cross-border payments into their own products without having to stitch together a maze of correspondent banks and local partners.

The timing made sense. Cross-border payments were massive—more than $155 trillion moving annually, with costs that could exceed $200 billion. And expectations had changed. Digital payments were becoming the default, regulators were pushing modernization, gig and temporary work was expanding across borders, and emerging markets were pulling more people into the formal economy. Customers no longer wanted “a few days.” They wanted “now,” with transparency.

Dandelion was Euronet’s answer: a real-time, cross-border payments network built on top of everything the company had been quietly building for decades. The infrastructure that once existed mainly to serve Ria and Xe became a wholesale product.

By then, the network spanned more than 600,000 cash locations and roughly 7 billion accounts across 195+ countries, with Euronet saying it could deliver 90% of payments in real time. In another snapshot of the same footprint, the network covered 624,000 locations across nearly 200 countries and supported 3.2 billion mobile wallet accounts, 4 billion bank accounts, and 4 billion Visa cards.

The pitch was straightforward: instant settlement across borders, without having to build and maintain thousands of banking relationships. On top of that, Dandelion bundled the hard parts that kill cross-border products in the real world—settlement, currencies on demand, compliance, and payment tracking—backed by a company with more than 35 years of experience managing risk and navigating local regulatory requirements.

Commercially, it was licensing-as-a-service. Instead of Euronet being only an operator with its own consumer brands, it could also be the platform other financial institutions and fintechs built on—using Euronet’s licenses, banking relationships, and local infrastructure rather than spending a decade assembling their own.

In parallel, Euronet developed REN: a platform designed to help payment processors modernize without ripping out and replacing existing hardware and software. Through REN Foundation, banks and payment service providers could adopt new technologies as they became available. Mozambique became the headline example: the country switched its entire payment systems to run on Euronet’s REN Foundation program.

That Mozambique deployment was a landmark not because it made for a good press release, but because it showed the logical endpoint of Euronet’s strategy: not just owning terminals or storefront locations, but powering the underlying rails. Under the agreement, Euronet supported transaction processing services, connections to major card associations, ATM and point-of-sale device driving, card issuing, mobile recharge, bill payments, and digital wallets, among other services.

Together, Dandelion and REN marked Euronet’s evolution from operator to platform provider—a shift that changed the ceiling on scale, and reshaped how the company could compete.

VIII. COVID-19 Crisis & Digital Acceleration (2020)

March 2020 hit Euronet in the one place it still couldn’t fully outgrow: cash.

Lockdowns rolled across Europe and beyond. Tourism evaporated. Cross-border travel stopped. And when people aren’t moving around, they aren’t hunting for ATMs in airports, train stations, city centers, and shopping districts. Overnight, the Electronic Funds Transfer segment—the original engine of the company—ran into the worst environment it had seen in decades.

What kept Euronet from getting crushed was the thing Mike Brown had been building toward for years: diversification.

Even before the world shut down, Ria was pushing forward. In February 2020, it opened its first retail store in Singapore, giving customers another place to send money at foreign exchange rates. Then, as lockdowns made storefront visits harder, Ria leaned into digital. In May 2020, it expanded its money transfer mobile app to European customers, meeting demand as remittance customers started shifting to apps and websites out of necessity.

Euronet also used the chaos to deepen distribution. In July 2020, OXXO—the biggest convenience store chain in Latin America—partnered with Ria Money Transfer to offer money transfer services in its stores. That instantly put Ria inside more than 20,000 locations across Mexico, a huge win in one of the world’s most important remittance corridors.

epay, meanwhile, benefited from the strange economics of lockdown life. In September 2020, it entered an agreement with Microsoft to manage monthly recurring billing for select retailers in the mobile gaming market. As more entertainment shifted to screens, gaming content—digital by nature and less dependent on foot traffic—helped steady results even when parts of physical retail were under pressure.

And Brown did what he often does in downturns: he bought. In December 2020, Euronet purchased 700 non-branch ATMs from the Bank of Ireland, a counter-cyclical move that signaled confidence and a willingness to pick up infrastructure assets when others were pulling back.

Earlier that year, in April 2020, Euronet also acquired Dolphin Debit, a U.S.-based ATM outsourcing company. Euronet already ran ATM outsourcing globally, but Dolphin Debit opened a new door: expanding those outsourcing services into the U.S. for the first time.

By the time the world began reopening, the bigger takeaway was already visible. COVID didn’t create Euronet’s digital shift, but it forced the pace. Customers who had relied on agent locations learned to use apps. And many didn’t go back. In the years that followed, Euronet’s digital money transfer business kept growing—transactions were up more than 30% in 2024—evidence that the behavior change wasn’t just temporary.

The 2020 lesson was blunt: diversification saved the company. When ATM volumes fell off a cliff, money transfer and epay helped carry the weight. When one channel got disrupted, another grew. And when the world’s payment habits changed faster than anyone expected, Euronet’s mix of physical infrastructure and digital rails turned out to be a lot more resilient than a single-product model.

IX. Recent Inflection Points: Strategic Expansion & Tech Partnerships (2020-2025)

The years after the pandemic didn’t bring Euronet a quiet recovery. They brought a sprint: keep the cash-and-ATM machine healthy, but accelerate the shift to digital while the window is open.

One of the clearest examples came in July 2025, when Ria Money Transfer and Xe announced a strategic collaboration with Google to make cross-border money transfers easier to find and use. The idea was simple: if people are already starting their journey inside Google’s ecosystem, meet them there, and remove friction between intent and transaction.

For Euronet, that kind of distribution is the prize. If Ria and Xe can show up where customers already are, the company can grow transaction volume without having to spend proportionally more to acquire each new user. It’s the same playbook as the XE acquisition—buy, build, or partner your way into attention—but now applied at platform scale.

At the same time, Euronet kept making moves on the infrastructure side. It signed an agreement with a top-three U.S. bank for its Ren ATM operating system, reinforcing that even as cash declines, running the machinery for banks is still valuable work—especially when the banks don’t want to do it themselves.

But the biggest recent swing was CoreCard.

Euronet entered into a definitive agreement to acquire CoreCard in a stock-for-stock merger that valued CoreCard at approximately $248 million, or $30 per share. Shareholders approved the acquisition on October 28, 2025. Pending customary closing conditions, it was expected to close on October 31, 2025.

CoreCard, founded in 2001, runs a credit card issuing and processing platform. Its software supports a wide range of card products—prepaid, revolving credit, fleet, debit, loans, and private-label programs—along with the card management tools and transaction processing that make those programs work day to day. And it comes with real credibility: CoreCard’s platform has been proven at scale with clients that include Goldman Sachs and American Express, plus fintechs like Cardless and Gemini.

The strategic logic is clear: combine CoreCard’s modern issuing stack with Euronet’s Ren architecture and its global distribution footprint. Under the deal terms, CoreCard shareholders would receive between 0.2783 and 0.3142 Euronet shares for each CoreCard share, with the final exchange ratio determined by Euronet’s stock price.

“More than a product expansion, this acquisition will be a catalyst for long-term growth, and we expect it to be accretive in the first full year post close,” said Michael J. Brown, Euronet’s Chairman and Chief Executive Officer. “By integrating CoreCard’s platform with our own Ren architecture and global distribution network, we will be positioned to become a leading modern card issuer and innovation partner for the next generation of digital financial services”.

Euronet also kept tightening its global remittance coverage. In Japan, Kyodai Remittance holds a Type 1 Funds Transfer Service Provider license, which allows transactions exceeding JPY 1 million (approximately USD $6,800). Integrating that capability with Ria’s network would give customers in Japan access to Ria’s global reach—an important step as Japan’s remittance market expanded, with USD $6.07 billion in personal remittances sent from Japan in 2024.

Meanwhile, Dandelion continued to get broader and faster. A partnership with Visa expanded the network’s real-time payout capabilities by enabling the integration of Visa Direct. The practical impact: real-time payouts to more than 4 billion debit cards, and the ability for EEFT customers to send money to Visa debit cards worldwide within minutes, using only the recipient’s name and card number.

All of this sits inside a larger, unavoidable trend. Management has been clear that the mix is shifting: ATM-based revenue is expected to fall sharply over time, while digital services take the overwhelming share. The timeline is aggressive, but it reflects a company that understands the direction of travel.

And even in the middle of that transition, the numbers suggested both sides of the house were still moving. In Q1 2025, the EFT Processing segment’s transaction volume rose 38%, and the Money Transfer segment reported a 10% increase in transactions—evidence that Euronet was still growing the legacy engine while building the next one.

X. The Business Model: Three Engines, One Platform

By this point in the story, Euronet stops looking like “an ATM company that bought some other stuff” and starts looking like what it actually is: three separate engines, stitched together by shared rails—technology, compliance, settlement, and distribution.

Those engines are Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT), epay, and Money Transfer. Each one wins in a different way. Together, they give Euronet something most payments companies never achieve: resilience.

Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) Segment

EFT is the original business—the part of Euronet that touches the physical world. It includes cash withdrawals and deposits at ATMs, ATM network participation, outsourced ATM and point-of-sale (POS) management, card outsourcing for credit, debit, and prepaid programs, card issuing, and merchant acquiring.

What began with roughly 300 ATMs has grown into a global fleet. Euronet has said its network now includes about 57,000 installed ATMs worldwide, and in another snapshot it described approximately 51,000 ATMs plus about 705,000 POS terminals across roughly 190 countries and territories.

The money comes from lots of small tolls: transaction fees, interchange, surcharges, and—when the customer is traveling—dynamic currency conversion margins. In Q3 2025, the EFT Processing Segment reported $409.4 million in revenue, up 10% from $373.0 million in Q3 2024.

epay Segment

epay is Euronet’s digital distribution machine. It distributes and processes prepaid mobile airtime and other electronic content, and provides payment processing services for a wide set of prepaid products, cards, and services.

In practice, epay is how big brands get their digital goods onto the shelves of everyday retail. It’s one of the world’s largest retail networks for distributing third-party content—both physical and digital—from leading brands. That means consumers can pay in the way that works for them, even if they’re unbanked, underbanked, or just standing at a corner store with cash in their pocket.

The portfolio is broad: prepaid mobile top-up, prepaid debit cards, e-wallets, gift cards, digital music and other content, lottery, bill payment, money transfer through its sister company Ria, and transport payments like road tolls and public transport.

Money Transfer Segment

Money Transfer is the cross-border engine. It includes consumer-to-consumer money transfer through a network of locations and through riamoneytransfer.com, account-to-account transfers, and digital money transfer through xe.com, the Xe app, and customer service representatives.

Within the segment, the two pillars are Ria and Dandelion.

Ria Money Transfer is one of the largest consumer remittance companies in the world, built for real-time international transfers with a particular strength in emerging markets. Customers can send through the Ria app or riamoneytransfer.com, and recipients can collect through a global network of roughly 630,000 cash locations.

Dandelion is Euronet’s real-time cross-border payments network. It handles transaction processing and fulfillment for both consumer and business flows, with payout options that include bank accounts, cash pick-up, and mobile wallets. It powers Xe and Ria, and it’s also used by third-party banks, fintechs, and big tech platforms.

Financially, this is the heavyweight. The Money Transfer segment was the largest revenue generator, contributing approximately 46% of consolidated revenues in Q1 2025.

Revenue Model

Across all three segments, the monetization is consistent: take a fee for moving value, earn a spread when foreign exchange is involved (especially through DCC), and collect commissions when prepaid products sell.

The mix has been shifting fast. Between 2019 and 2024, revenue rose 45%, from $2.8 billion to $4 billion. And by 2024, only 19% of revenue was generated from Euronet-owned ATMs—while the faster-growing lines of business did more of the work.

The elegant part is how often these systems reinforce each other in the real world. Someone can send money digitally through the Ria app, while the recipient picks up cash through a physical agent location. A traveler can pull local currency from an ATM and then buy prepaid content at a nearby retailer. Underneath both experiences sits the same advantage Euronet has been compounding for decades: payment rails, compliance infrastructure, and banking relationships that can be reused across products instead of rebuilt from scratch.

XI. The Mike Brown Era: 30+ Years of Leadership

Michael J. Brown co-founded Euronet in 1994 and has been its Chief Executive Officer ever since. He also serves as chairman of the board and the company’s President. In a business that lives and dies on reliability, Brown’s leadership has been a defining constant—less “startup rocket ship,” more long-haul operator building rails country by country.

Brown is an entrepreneur with decades of experience spanning computer software and digital payments, and he has stayed closely involved in Euronet’s day-to-day operations while steering strategy, financial performance, and growth across markets. That hands-on posture matters, because Euronet’s edge has never been a single product. It’s execution: getting machines installed, networks connected, partners signed, money settled, and compliance handled—repeated thousands of times, in dozens of regulatory environments.

From the first ATM in Hungary to a global footprint, Brown helped scale Euronet to roughly 10,000 employees and 67 offices worldwide, operating a payments network spanning about 200 countries and territories. And while Euronet’s businesses are often described in terms of transactions and locations, the human outcome is simpler: more ways for people and businesses to access and move money, especially in places where the infrastructure lagged demand.

His personal story is its own kind of signal. Brown is a lifelong Kansas Citian and has supported Kansas City-area charities as an active supporter and past and present board member. His education is also unusual for a fintech CEO: a Bachelor of Science in electrical engineering from the University of Missouri-Columbia in 1979, and later a Master of Science in molecular and cellular biology from the University of Missouri-Kansas City in 1997. No MBA, no classic finance pedigree—more builder than banker. You can feel that in Euronet’s bias toward infrastructure, systems thinking, and operational excellence over marketing flash.

Founder-led companies get talked about like a cliché, but at Euronet the advantages are real: long-term thinking, strategic patience, and an M&A discipline that’s been refined over decades. Brown has executed acquisition after acquisition without the integration blowups that usually come with that pace. The through-line is consistent: buy distribution and infrastructure, not just technology—then plug it into Euronet’s rails.

That same mindset shows up in how the company operates. The philosophy is basically: own the infrastructure, control the network. Instead of relying on third parties for critical capabilities, Euronet has built or acquired pieces across its value chain—from ATM operations to payout networks to compliance and settlement.

And Brown hasn’t built alone. Juan C. Bianchi joined Euronet after the company acquired RIA Envia Inc. in April 2007. As CEO of the Money Transfer segment, Bianchi oversees Euronet’s money transfer operations worldwide, responsible for the segment’s financial and operational performance and for driving global strategy. Before the acquisition, he was CEO of Ria, and he has spent his entire career at either Ria or AFEX Money Express.

That kind of tenure is rare in payments, an industry known for churn at the top. Euronet’s leadership continuity has helped it retain institutional knowledge, build long-term relationships with partners, and navigate regulators market by market.

Still, the obvious question hangs over any company with a 30+ year CEO: succession. Brown remained actively involved in day-to-day operations, but what leadership looks like after him is still an open question—and one investors continued to watch closely.

XII. Competitive Landscape & Challenges

Euronet’s story is, at its core, a story about building rails. The problem is that rails attract traffic, and traffic attracts competitors. By the mid-2020s, every part of Euronet’s portfolio had serious, well-funded companies trying to take share.

EFT Competition

On the ATM and point-of-sale side, Euronet goes up against giants like Fiserv, FIS, and NCR Atleos. These companies have scale, strong balance sheets, and deep relationships with banks—exactly the customers Euronet also wants when it’s selling outsourcing, software, and operational services.

Euronet’s differentiation has never been that it’s the only one who can run terminals. It’s that it built an independent ATM model in markets where banks didn’t want to do the work themselves, and then expanded it aggressively. Over time, it paired that physical footprint with two other scale businesses: what it describes as the world’s largest payment network for prepaid mobile top-up, and Ria, which it positions as the second-largest global money transfer company.

Money Transfer Competition

Remittances are a knife fight.

One market share snapshot put Western Union at about 12% of remittances, followed by Remitly at around 4%, then Intermex, MoneyGram, and Ria at roughly 3% each, with Viamericas at about 1.5%. In digital remittances specifically, Western Union and PayPal have been described as holding a significant combined share of more than 20%.

But the bigger truth is that the competitive set keeps expanding. Ria isn’t just battling the old guard—Western Union and MoneyGram—it’s also dealing with app-first rivals like Wise and Remitly, and broader fintechs like Revolut moving into cross-border flows. And Western Union’s own position has been shifting: since 2009, it has seen gradual share decline as the market became more complex and more digital, and as customers demanded better pricing and better experiences.

epay Competition

In prepaid distribution, Euronet faces large, established players like InComm Payments and Blackhawk Network. This isn’t a market where a single clever feature wins. It’s a grind of retailer relationships, distribution scale, and operational reliability—areas where Euronet is strong, but not alone.

Regulatory Challenges

The downside of being the company with machines and logos in the real world is that you’re also the company that gets blamed when customers feel surprised by fees.

Euronet has run into repeated scrutiny in Europe. In 2018, the Danish Consumer Council warned against using Euronet ATMs due to high fees, saying, “The fee is the same as if you withdraw in an ATM that is physically located abroad”. In January 2019, Amsterdam’s municipality announced plans to prevent new Euronet ATMs from opening in shop facades, citing that Euronet “charges a hefty fee per cash withdrawal and uses unfavorable exchange rates”.

That same year, Prague criticized Euronet after hundreds of ATMs appeared around the city, with several reportedly installed into the facades of historic buildings and heritage sites without permission, in some cases causing irreversible damage.

More recently, in 2023, Euronet changed the ATM interface in the Czech Republic and Poland, and some believed customers could be misled into selecting a “Cash and Balance” service that charged an additional fee for a balance inquiry. Poland’s Office of Competition and Consumer Protection stated that it was investigating the issue.

The Cash Decline Threat

Then there’s the long-term, structural risk: what happens when the world simply stops using cash?

Cash use has been declining across developed markets for years, and the pandemic accelerated the trend. Euronet has been living that shift in real time. Euronet-owned ATMs generated 19% of revenue by 2024, down from 25% in 2019, and the direction of travel is hard to argue with.

That doesn’t mean the EFT segment disappears overnight. But it does mean the company has to keep migrating growth to businesses that don’t depend on someone walking up to a machine.

Digital-Native Pressure

Even within money transfer—Euronet’s biggest growth engine—digital-native competitors keep squeezing the market.

Companies like Wise and Remitly have trained customers to expect modern apps, transparent pricing, and clean user experiences. That pressure doesn’t just move share; it compresses margins for everyone else. For legacy and hybrid providers, the challenge is brutal: match the UX expectations of a software-first business while still carrying the costs, complexity, and compliance burden of a global physical payout network.

XIII. Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-LOW

Euronet benefits from the unsexy things that make payments hard: long-term contracts, regulatory licenses across dozens of countries, and compliance infrastructure that takes years to build. On the physical side, there’s also a real capex wall. Building and operating ATMs, POS terminals, and cash pickup networks isn’t just software. It’s hardware, service teams, cash logistics, and uptime.

But the threat isn’t evenly distributed. Starting an EFT-style business at scale is brutally difficult. Attacking money transfer from the outside, digitally, is much easier. A digital-only remittance competitor can launch with far less capital, then try to win customers with product and pricing while relying on someone else’s payout infrastructure.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Most of what Euronet buys is either commoditized or competitive. ATM and POS hardware comes from multiple manufacturers. Cash-in-transit providers compete for contracts. And a meaningful portion of the software stack is built in-house or brought inside through acquisitions. That combination tends to keep supplier leverage low.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

On the customer side, power concentrates quickly. Big retailers can push hard on margins in epay. Banks can negotiate aggressively when deciding whether—and how—to outsource ATM operations. And in money transfer, consumers are famously price-sensitive, with digital comparison making it easy to shop the best rate.

Still, not all customers are equally free to walk away. Once a bank has outsourced its ATM network, switching providers can be disruptive, time-consuming, and risky. Integrated partners may negotiate hard up front, but they don’t churn casually.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

The substitute threat is real and rising. Digital wallets increasingly replace the everyday reasons people used cash. Crypto can be an alternative path for cross-border value transfer. And real-time bank-to-bank payment networks reduce the need for cash access in the first place. As more economies go cashless, the baseline demand for ATM withdrawals declines—especially in developed markets.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Euronet fights on multiple fronts in crowded arenas. Remittances still have a heavyweight incumbent in Western Union, while fintech challengers keep pushing digital experiences forward and squeezing pricing. Across payment corridors, competition can become a straight price war, fast.

Euronet’s partial advantage is breadth. Few rivals compete meaningfully across all three of its segments, which gives the company diversification and multiple ways to win—even when one battleground gets uglier.

XIV. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: STRONG

Euronet runs at a scale that’s hard to appreciate until you zoom out: roughly 51,000 ATMs and about 705,000 POS terminals spread across around 190 countries and territories. That footprint lets it spread fixed costs across billions of transactions, creating real operating leverage. And scale buys leverage in another way too: when you’re embedded across that many markets and retailers, you tend to get better terms, better placement, and more staying power in negotiations.

2. Network Effects: MODERATE-STRONG (and growing)

In money transfer, the flywheel is classic: more payout locations and options attract more customers, which attracts more agents and partners, which makes the network even more useful. Dandelion gets stronger the same way—every new connection increases the platform’s value to the next institution considering it.

epay has a similar dynamic. More retailers mean more distribution. More distribution attracts more brands and products. More products then make the retailer relationship more valuable. It’s a network effect, even if it looks like “just” distribution.

The caveat is important: these aren’t as absolute as Visa or Mastercard, where the network is the product and switching becomes nearly unthinkable. Euronet’s networks are powerful, but they’re not unassailable.

3. Counter-Positioning: WEAK

There is a form of counter-positioning in the original EFT business: many banks can’t—or simply don’t want to—build and operate independent ATM fleets because of the capital spend and operational hassle. That reluctance created space for Euronet in the first place.

But in the most contested parts of the market, the counter-positioning cuts the other direction. Digital-native fintechs can position themselves against Euronet’s legacy infrastructure with cleaner pricing, simpler apps, and a product experience that doesn’t come with the baggage of physical networks.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE

For institutional customers, switching can be painful. Multi-year contracts, integrated processing, and the operational risk of moving mission-critical payments systems create meaningful friction. In money transfer and cross-border payments, licensing and regulatory complexity raise the bar further. You don’t swap providers lightly when compliance is on the line.

For consumers, though, switching costs are close to zero. If a customer decides Wise is cheaper or easier, they can stop using Ria immediately. That’s the structural weakness: high switching costs where Euronet sells infrastructure, low switching costs where it sells directly to people.

5. Branding: WEAK-MODERATE

Euronet’s brand is split across Euronet, Ria, epay, and Xe. Ria and Xe have recognition in specific markets, but neither has the universal consumer trust and awareness of Western Union.

In fairness, Euronet doesn’t need a dominant consumer brand to win in B2B infrastructure. But in money transfer, brand still matters—especially when the product is one tap away from a competitor and the customer is choosing based on trust and perceived fairness.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Euronet’s cornered resource is mostly regulatory and physical: licenses in over 60 countries, plus a presence in key markets that took decades to assemble. Those are hard to replicate quickly. Retail partnerships—like Walmart and OXXO—also create meaningful distribution advantages.

Still, no single asset is truly proprietary or impossible to copy over time. The moat here is cumulative, not magical.

7. Process Power: MODERATE-STRONG

This might be the most underrated power in the whole story. Euronet has spent more than 35 years building the muscle memory for running payments businesses globally—managing risk, handling compliance country by country, and operating reliably in emerging markets where conditions change fast. That operational know-how, built through repetition and hard lessons, is a durable advantage.

On the technology side, platforms like Ren reinforce that process power by giving Euronet a way to modernize and deliver real-time payments infrastructure without starting from scratch in every market.

Primary Power Assessment: Network Effects + Scale Economies + Process Power

Together, those three powers form Euronet’s moat. But it’s a moat in motion. The ATM side is under long-term pressure as cash declines, while the money transfer, platform, and digital distribution sides are getting stronger as the network grows and more of the world’s payments move onto real-time rails.

XV. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

The bull view is that Euronet is pulling off a rare trick in payments: it’s shifting meaningfully toward digital without letting the legacy infrastructure business collapse underneath it. Digital money transfer transactions grew more than 30% in 2024, and by the end of the year 54% of payout volume was digital. That matters because it suggests the company isn’t just “adding an app.” It’s actually changing how money moves through its network.

The other tailwind is simply the market itself. The global digital remittance market, valued at $23.4 billion in 2024, is projected to grow at a 13.5% CAGR to $83.2 billion by 2034. Euronet’s pitch is that it can win here precisely because it isn’t purely digital or purely physical. It can originate transactions online and still land them in the real world, through cash pickup, bank accounts, and mobile wallets, depending on what the receiver can actually use.

Bulls also point to CoreCard as a step up the stack. Instead of earning only “tolls” on transactions, Euronet adds higher-margin software and processing from a card issuing and processing platform. Euronet said the acquisition was expected to be accretive to adjusted EPS, and CoreCard forecast 2025 revenue of $66.8 million with adjusted EBITDA of $16.1 million.

Distribution is the other advantage that’s hard to replicate. Partnerships with Google, Tencent, Walmart, and others put Euronet’s products in front of customers without requiring the company to spend proportionally more on customer acquisition. And Dandelion extends that idea beyond consumer remittance: it positions Euronet as infrastructure-as-a-service for cross-border payments, selling the rails to other businesses instead of only running cars on them.

Finally, the bulls lean on consistency. The company anticipated 2025 adjusted EPS growth of 12% to 16% year over year, in line with its long-term compounded growth rates over the last 10 and 20 years. Brown framed that stability as a feature of the model’s diversification: “I would offer that we do not see any direct impacts on our business as a result of the recent United States’ tariff actions,” he said. “With a good start to the year together with our diversified global business, we are reaffirming our expectation to produce 12% to 16% earnings growth for the year.”

Bear Case

The bear case starts with the most obvious structural threat: cash is shrinking. Management itself projected ATM-based revenue would decline from 19% of revenue in 2024 to about 7% by 2034. Even if Euronet keeps the absolute dollars stable for a while, a business built on physical cash access can’t be the long-term growth engine in a world that keeps moving to tap-to-pay.

Then there’s the fight for the digital customer. Remitly, Revolut, and Wise keep taking share with simpler user experiences and aggressive pricing. Euronet’s bears argue that a company built through decades of infrastructure buildout and acquisitions can end up with legacy tech, integration complexity, and a fragmented brand identity—exactly the things that make it hard to compete against digital-native products.

Regulation is another pressure point, especially where Euronet is most visible: ATM fees and dynamic currency conversion. In Europe, DCC drew attention from the Czech Ministry of Finance, which elevated the issue to the European Union. The EU responded with a regulation requiring ATMs to show customers the exchange rate and the deviation from the European Central Bank’s exchange rate. That rule entered into force in April 2020. Bears see these kinds of changes as both headline risk and a potential squeeze on one of the higher-margin levers in the EFT business.

Money transfer, meanwhile, is not a gentle market. Competition is intense, and pricing pressure has been relentless for decades. One estimate suggests industry margins have fallen steadily, dropping about 40% over the previous 15 years to under 5% today. Even Western Union, historically able to sustain higher pricing, saw its markup stay above 5% until 2019 before sliding to under 3.5% as lower-cost digital transfers became a larger share of the mix. If the giants are getting squeezed, the underdogs aren’t getting a free pass.

Finally, the bears point to execution risk. Euronet has done a lot of M&A, and integration is never “done” once the deal closes—especially with a platform like CoreCard that touches the core of card issuing and processing. Add in the unresolved succession question for a CEO who has led the company for more than 30 years, and the downside case looks like this: a company with valuable assets, but forced to run faster every year just to stay in place.

XVI. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

By now, Euronet can look like a blur of segments, acquisitions, and networks. But if you’re trying to judge whether the story is getting better or worse from here, you don’t need a hundred metrics.

You need three.

1. Digital Transaction Growth Rate (Money Transfer Segment)

This is the scoreboard for Euronet’s most important transition: moving remittances from counters to screens without losing volume to app-first rivals. Coming out of 2024, 54% of payout volume was digital. Track how quickly that share rises, and whether it accelerates or stalls. It’s the most direct signal of whether Ria and Xe are winning in the world the market is becoming.

2. Constant Currency Revenue Growth by Segment

Euronet operates everywhere, which means currency can make growth look better—or worse—than it really is. That’s why constant currency growth matters: it strips out FX noise and tells you what demand is actually doing.

In Q3 2025, revenue rose 4% as reported, but only 1% on a constant currency basis. That gap is the reminder. If you don’t separate the business from the exchange rates, you can misread momentum.

3. Adjusted EBITDA Margin Trend

Euronet’s pitch, at its core, is operating leverage: once the rails are built, more transactions should drop through at better economics. As the mix shifts toward digital and platform services, the margin should tell the truth.

In 2024, Euronet generated $3,989.8 million in revenue and adjusted EBITDA of close to $700 million, or roughly a 17% margin. Watching whether that margin expands as the company “goes digital” is how you judge whether the transformation is actually creating value—or just reshuffling revenue.

XVII. Conclusion

Euronet Worldwide sits at one of those rare moments where the past and the future collide.

The company Mike Brown and Dan Henry started in Budapest three decades ago—essentially a bet that post-Soviet Europe would need basic financial plumbing—has grown into a global payments platform spanning three business segments, roughly 200 countries and territories, and billions of transactions.

What’s striking is how consistent the playbook has stayed, even as the products changed. Euronet has repeatedly built or bought infrastructure, leaned into network effects, diversified across geographies and revenue streams, and played the long game. That approach helped produce adjusted EPS growth in the low-to-mid teens, consistent with what it delivered over long multi-year periods—something very few fintechs have managed without blowing themselves up along the way.

But the next chapter is harder than the last. Cash usage keeps declining. Digital-native competitors keep raising the bar on user experience and pricing. And regulators have shown they’re willing to step in when ATM fees and dynamic currency conversion feel unfair or unclear. The same physical footprint that once looked like an unassailable moat—ATMs, agent locations, POS terminals—can start to look like drag in a world that wants everything to happen instantly, inside an app.

Brown has been direct about that shift: "While I am very proud of our heritage, we're not just in the ATM business. We invested heavily in card acquiring, in REN, Dandelion, Digital Money Transfer, ePay, and you can see the results".

CoreCard, the Google partnership, and Dandelion’s continued expansion are all signals of the same internal conclusion: the future is digital infrastructure, not just physical machines. The open question is execution. Can Euronet migrate the mix fast enough, keep customers as they move from storefronts to screens, and still protect profitability as pricing pressure intensifies?

Dandelion is the clearest expression of the bull thesis. Euronet has described it as the world’s only global payments infrastructure delivering real-time transactions backed by 35 years of compliance and expertise. That head start—licenses, banking relationships, compliance systems, local teams—took decades to assemble, and it’s not something a new entrant can spin up in a couple of funding rounds. The real test is whether that advantage stays valuable when the “last mile” of the customer experience belongs to someone else’s interface.

For long-term fundamental investors, Euronet is a case study in reinvention. It has already transformed itself more than once: from ATM operator, to prepaid distribution network, to global remittance player, to platform company selling the rails. Whether it can pull off one more transformation—and make the next thirty years as durable as the first—remains the question that matters.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music