Ennis Inc.: The Roll-Up That Refused to Die

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

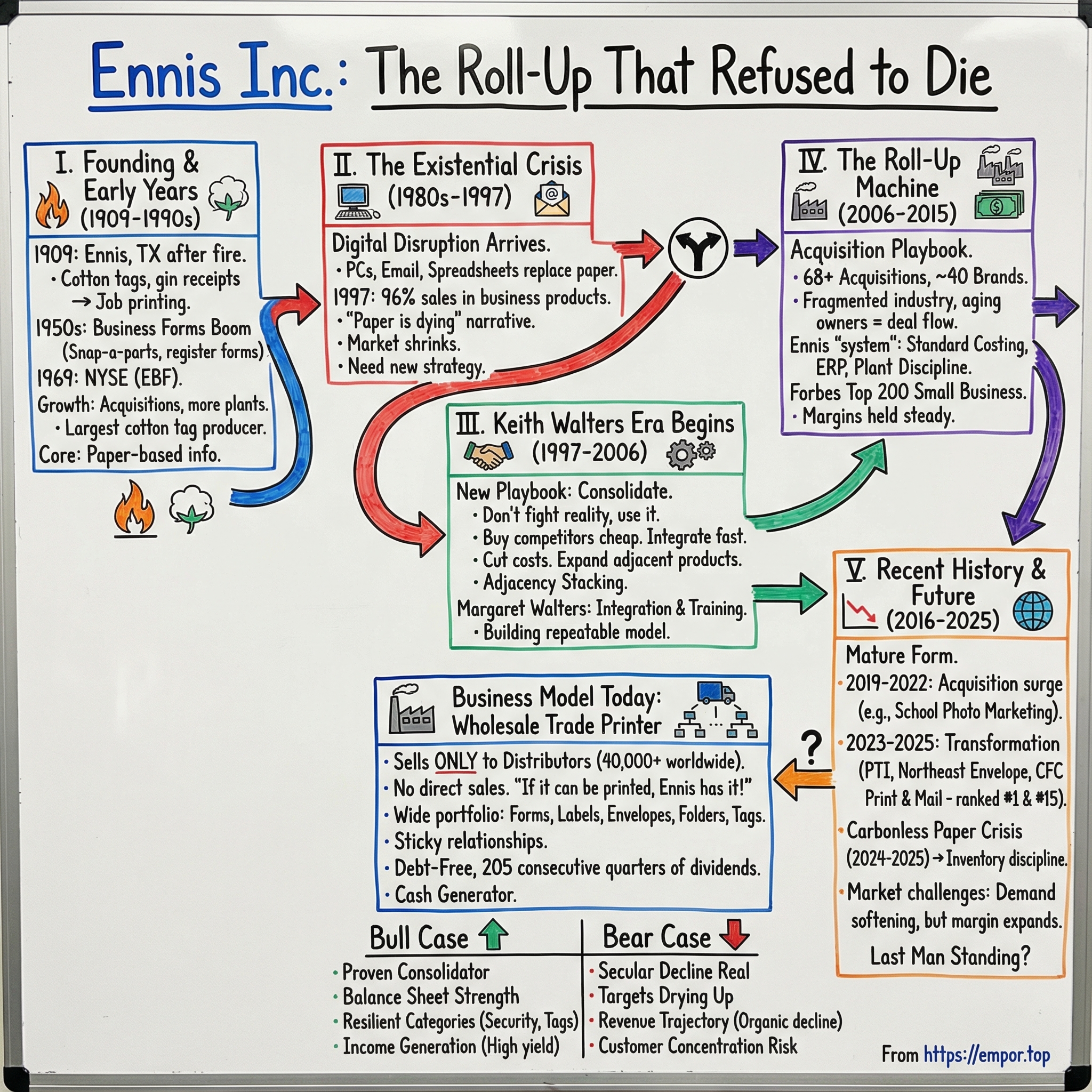

Picture a small Texas town in the early 1900s: cotton fields out to the horizon, and then a fire that wiped out the local newspaper facility. In the aftermath, a print shop opened its doors. It was a modest start—so modest that no one would’ve predicted it would still be here more than a century later, much less as the largest trade printer in the United States. This is the story of Ennis Inc., a company that lived through world wars, the Great Depression, the digital revolution, and the slow-motion collapse of the very category it was built on.

Ennis, Inc. (NYSE: EBF) was founded in 1909 in Ennis, Texas. Today it spans more than 55 locations across the U.S. and sits at the center of the wholesale print world—making and supplying print products that flow through distributors rather than directly to end customers. And that’s where the story gets interesting. Ennis didn’t survive by pretending paper would win. It survived by figuring out how to make real money in a business everyone assumed was headed for the grave.

That sets up the question at the heart of this episode: how does a business forms company survive—and actually thrive—in the digital age?

The answer isn’t a shiny tech pivot or some breakthrough product. It’s the unglamorous stuff that compounds: disciplined consolidation, ruthless attention to costs, and capital allocation that treats every dollar like it has to earn its keep.

Over the decades, Ennis grew primarily by acquisition, turning a one-employee operation into a nationwide manufacturer supported by an ever-expanding network. The transformation didn’t happen by accident. It came from a repeatable playbook—and, crucially, a leader willing to run it year after year.

Under CEO Keith Walters, Ennis completed 68 acquisitions and brought roughly 40 brands under the Ennis umbrella, diversifying well beyond traditional business forms. That pace—nearly three deals a year for more than two decades—isn’t “growth strategy.” It’s an operating system.

Now, more than 115 years after its founding, Ennis employs over 1,850 people and serves more than 40,000 distributors worldwide. It’s an old-line company in an old-line industry that somehow keeps getting bigger.

So this is a story about a few things at once: an industry in decline, a roll-up machine built with patience and process, and the quiet power of being the best consolidator in a “boring” category. By the end, you’ll see why Ennis is such a compelling case study—how an existential threat didn’t kill the company, but instead became the condition that made its strategy work.

II. The Founding & Early Years (1909-1990s)

Ennis, Inc. began in Ennis, Texas in 1909, after a fire tore through the local newspaper facility. Garner Dunkerley, Sr. stepped into the wreckage, bought the subscriber list and equipment for $1,000, and launched Ennis Printing & Publishing. It’s the kind of origin story that sounds almost too neat—disaster, then opportunity—but it also foreshadowed something real about Ennis: this company learned early how to rebuild fast.

The startup capital was as local as it gets. The company issued 180 shares at $50 each, sold them to 23 residents, and raised $9,000—roughly $300,000 in today’s dollars. Not much money, but paired with something that mattered more: a clear read on what customers around them actually needed.

At first, Ennis sold advertising and did job printing. But it also started buying and reselling cotton tags to the warehouses and gins in the area. Soon Dunkerley moved from dealing to making—buying blank tags, overprinting them, and eventually purchasing the company’s first tag press. For years, cotton tags, gin receipts, and related supplies were the core output, right up until 1936.

That shift—from publishing a newspaper to supplying the paperwork of the cotton economy—was a preview of Ennis’s most important habit. It didn’t cling to a product for sentimental reasons. It followed demand.

By the late 1930s, the company sold off the newspaper business entirely so it could focus on its expanding tag and book business. The future wasn’t newsprint; it was the unglamorous infrastructure of commerce: tags, labels, and the kinds of forms that made fast-growing businesses legible and accountable.

In 1953 and 1954, Ennis began producing snap-a-parts, register forms, and continuous forms. A few years later, in 1957 and 1958, Garner Dunkerley, Jr. was elected president and the company renamed itself Ennis Business Forms, Inc.

The timing couldn’t have been better. Postwar America ran on paperwork. Every invoice, receipt, purchase order, and shipping document needed copies—often multiple—and those copies were made with the carbon-based forms Ennis specialized in. The economy boomed, and business forms boomed with it.

Expansion followed. In 1966, Ennis established a facility in DeWitt, Iowa. In 1967, Len Gehgrig became president—and the company began an acquisition program, starting with ABC Business Forms in Miami, Florida.

That first deal matters because it set the pattern. Ennis wasn’t just going to grow by selling more forms. It was going to grow by buying capacity, customers, and footprint.

Two years later, in 1969, Ennis began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker EBF. Going public gave the company a bigger war chest and a more flexible currency for growth. It could fund expansion with access to public markets and, when it made sense, with equity.

Through the 1970s, Ennis expanded to Knoxville, Tennessee; Fort Scott, Kansas; and Wolfe City, Texas. The Wolfe City acquisition helped make Ennis the largest producer of cotton tags in the world—an echo of its earliest product line, now scaled up into global leadership.

In 1980, Ennis expanded manufacturing again, adding facilities in Moultrie, Georgia and Coshocton, Ohio to produce snap-a-parts.

From the outside, it looked like steady, sensible growth: more plants, more products, more acquisitions, more scale. But a storm was building behind the numbers. The personal computer was moving from curiosity to inevitability. And Ennis—built on paper-based information transfer—sat squarely in the path of the next great disruption.

Still, the early decades left Ennis with two traits that would later become survival equipment: it could change what it sold without losing its identity, and it was willing to buy growth rather than wait for it. Those instincts were formed long before “digital transformation” was a phrase. And soon, they’d be tested.

III. The Existential Crisis: Digital Disruption Arrives (1980s-1997)

To understand what Ennis faced in the late 1980s and early 1990s, imagine running a business that exists to move information around on paper—then watching the world discover it can move that same information at the speed of light.

For most of the 20th century, business forms were one of the great tailwinds of American commerce. Every order, shipment, payroll run, and invoice generated a stack of paper, often in duplicate or triplicate. Ennis had built its footprint, its plants, and its identity around being excellent at that unglamorous work.

By 1997, the company employed 1,554 people and generated $153.73 million in sales—nearly nine decades of steady compounding. But the ground underneath that compounding was starting to shift.

The single most dangerous line in the story is this: in 1997, business products still made up 96% of Ennis’s net sales. In a growing market, focus looks like discipline. In a shrinking market, it looks like exposure. Almost everything Ennis did—its equipment, its capacity, its sales motion, its operating rhythm—was tied to a category that was about to stop behaving like a growth industry.

At first, the personal computer boom didn’t feel like a threat. Early office printers loved continuous-feed paper. Multipart invoices, checks, mailing labels—those still needed specialized forms. It was easy to convince yourself that digitization might even help.

But it was a false dawn.

As the 1990s rolled on, the replacement wasn’t “new paper.” It was no paper. Email began displacing memos. Spreadsheets replaced ledgers. Accounting and ERP systems reduced the need to pass forms from desk to desk. Electronic invoicing started creeping in at the edges. Even the fax machine—briefly a lifeline for paper-based workflows—was getting swallowed by the next wave of digital communication.

Ennis could see it. And by the time it reached 1997, the company had started openly trying to lessen its dependence on business forms.

The strategic dilemma was simple and brutal. When an industry slows down, there are only so many levers left. You can try to grow by taking share—usually by cutting price—and watch your margins bleed out. Or you can diversify into adjacent products and categories, which requires capital, operational know-how, and a willingness to change what the company is.

Ennis began to test that second path. In April 1996, it acquired a presentation folder manufacturer in Los Angeles. On paper, it looked like a small, almost forgettable deal. In reality, it was Ennis admitting something important: the future couldn’t be one product line.

Still, a few tentative steps don’t solve an existential problem. What Ennis needed next was leadership that didn’t just understand printing—but understood how to run a transformation inside a manufacturing business. In August 1997, that leadership arrived.

To investors watching at the time, Ennis could easily have looked like a classic value trap: a cheap stock in a dying category, overly concentrated, with limited obvious upside. But what the market could miss in moments like this is optionality. The very assets that made Ennis formidable in forms—its distributor relationships, its manufacturing discipline, its nationwide footprint—could become the base for a different kind of company.

The question was whether Ennis could move fast enough, and whether its next CEO would be willing to play a very different game than the one the company had been playing for the last 88 years.

IV. The Keith Walters Era Begins: A New Playbook (1997-2006)

Keith S. Walters arrived at Ennis in August 1997 as Vice President of Commercial Printing Operations. Three months later, in November, he became CEO.

That kind of timeline doesn’t happen in a healthy, unhurried company. It happens when the board looks at the curve in front of it and decides it can’t afford a gentle handoff. Ennis didn’t just need a new leader. It needed a new operating system.

Walters brought exactly that. He wasn’t a lifelong printing executive, and that was the point. His reputation was built in manufacturing and operations—industries where you survive by controlling costs, standardizing processes, and making plants run like clockwork. Over a four-decade career, he’d managed multiple manufacturing facilities and participated in more than 37 acquisitions, with a particular strength in post-deal integration: getting systems aligned, cultures stabilized, and performance improved.

That background mattered because printing was about to experience what autos and electronics had already lived through: contraction, relentless price pressure, and consolidation. Walters had seen what happens when capacity exceeds demand. He’d also seen the opportunity hidden inside that pain—especially for a buyer with discipline.

He also joined Ennis’s Board in 1997 and later served as Chairman. And while his academic background—Political Science and Geology from Ohio University—didn’t scream “trade printer,” it fit the way he operated: pragmatic, systems-driven, and comfortable navigating complexity.

The strategic insight Walters leaned on was simple and, for a legacy forms company, almost heretical: if business forms are structurally declining, don’t waste energy arguing with reality. Use it.

So instead of defending the old world, Walters positioned Ennis to consolidate it. Buy competitors when they’re cheap. Integrate them fast. Take out redundant costs. And, crucially, expand into adjacent printed products that could ride through the same distributor channels and be made with similar manufacturing know-how.

This wasn’t a leap into some unfamiliar future. It was adjacency stacking. Ennis already understood the mechanics of making printed products at scale. Moving into things like folders, labels, envelopes, and other print items wasn’t reinvention—it was expansion. And because Ennis sold through distributors rather than going direct, it could deepen those relationships by offering more of what the same customers were already buying.

The real advantage, though, was timing. Declining industries create motivated sellers. Family-owned printers with aging owners don’t always have successors lined up, especially when the headline story of the sector is “paper is dead.” Walters turned that into deal flow. Ennis could become the natural home for companies that didn’t want to simply shut the doors.

One of the more unusual pieces of this story is how much of the integration machine was shaped by someone not listed on the org chart. Margaret Walters, Keith’s wife, played a significant informal role in the company after his appointment in 1997. She was a trained educator with curriculum development expertise, and she helped build the standard cost training curriculum and tools Ennis used to bring new plants onto its way of operating and to train plant managers. That discipline—standard costing, consistent training, repeatable integration—was a big part of how Ennis managed to keep operating margins healthy even as it absorbed more businesses.

For nearly 25 years, she also attended industry events and trade shows, building relationships with suppliers, distributors, and other printing companies. Those relationships mattered. In a fragmented industry, acquisitions often come from trust and familiarity long before they come from bankers.

Put all of that together and you can see what Walters really built in this first phase: not a one-off turnaround, but a repeatable model. By the mid-2000s, Ennis was already shifting from “a business forms company trying to diversify” into something more durable—a company betting that it could buy, integrate, and operate printing businesses better than anyone else.

And that distinction is everything. A printing lifer might have tried to protect the legacy. Walters treated decline as the landscape, not the crisis—and started building an empire designed to win inside it.

V. The Roll-Up Machine: Building the Acquisition Playbook (2006-2015)

If the early Walters era was about choosing a direction, the stretch from 2006 to 2015 was about turning that direction into a machine. Ennis wasn’t just “doing acquisitions.” It was building the muscle to do them repeatedly, integrate them quickly, and come out the other side stronger.

Over his CEO tenure, Walters oversaw 68 acquisitions and brought about 40 brands into the Ennis family. That’s not a growth spurt. That’s a worldview: when your core market is maturing or shrinking, you don’t wait for demand to come back. You consolidate the supply.

And it’s worth pausing on what that cadence really implies. Each acquisition means finding the target, getting comfortable with the books, agreeing on price, and then doing the hard part—making the new business actually run inside Ennis. At roughly a few deals a year, Ennis effectively operated with M&A as a standing capability, not an occasional event.

Printing made that possible because it has long been a fragmented, local-business industry—thousands of small and mid-sized operators, many of them family-owned. A lot of those shops could still be profitable, but they had a quiet, structural problem: succession. Owners who’d spent decades building their companies often didn’t have someone ready—or willing—to take the wheel. Against that backdrop, Ennis could show up as something rare: a credible buyer that understood the business and could offer an exit.

What made the strategy work wasn’t only buying companies. It was what happened after the ink dried.

Ennis invested in systems that directly improved how fast acquisitions turned into positive returns. Walters’ approach earned the company meaningful recognition, including repeated placement on Forbes Magazine’s “Top 200 Small Businesses” list (Ennis was the only wholesale printer named, and appeared five consecutive years before it outgrew the list’s eligibility rules). In the trade world, Ennis also rose to the top of supplier rankings, including a long-running #1 spot on Print+Promo’s “Top 50 Suppliers” list and sustained recognition from PSDA’s “Top 50 Member Trade Printers” list.

That industry credibility wasn’t just a trophy case. It sent a signal to potential sellers: Ennis was the buyer who could close, integrate, and keep the lights on. In a business where reputations travel fast, that mattered. It helped drive deal flow and reinforced Ennis as the natural consolidator.

At the same time, the product portfolio kept widening—by design. In Ennis’s Print segment, the company designs, manufactures, and sells business forms and printed business products like snap sets, continuous forms, laser cut sheets, tags, labels, envelopes, integrated products, jumbo rolls, and pressure sensitive products. It also produces financial and security documents, presentation and document folders, promotional products, and advertising concept products across more than 50 locations. Many facilities add warehousing, kitting, and fulfillment on top.

The point of all that breadth wasn’t to chase shiny objects. It was to become more valuable to the same distributor base. If a distributor already relied on Ennis for forms, Ennis wanted to be the easiest answer for envelopes, labels, folders, and more. That “one-stop shop” positioning increased stickiness and made it harder for a distributor to justify switching suppliers.

Underneath the product expansion was what Ennis itself described as an unusually deep operating system. As the company put it: “The Ennis system also allows our Business Unit Directors to monitor multiple plants simultaneously… [it] is nonexistent in the print manufacturing world today based on my experience.”

That operating system was the real acquisition playbook. Ennis didn’t buy businesses and hope they stayed healthy. It moved them onto Ennis standards. ERP systems came in. Standard costing was implemented. Plant leaders were trained in Ennis’s methods for inventory control, scheduling, and quality. The goal was consistent performance and real-time visibility—so corporate leadership could see what was happening across plants and act quickly.

When a deal closed, integration wasn’t treated as a slow cultural merge. It was a fast conversion. Ennis started the work immediately, aiming to bring each facility into the same language, the same metrics, and the same rhythm.

What that created for investors was a very particular profile. Even as the broader market for forms faced long-term pressure, Ennis could keep growing by taking share—often simply by buying the competition. It could protect or improve margins by removing duplicated overhead and applying its process discipline. And it could fund much of this through operating cash flow rather than leaning heavily on debt.

In a roll-up story, the plot always comes down to execution: can you integrate faster than you buy, and can you actually improve the acquired businesses instead of just stacking revenue? For Ennis, this era was the proof. The strategy wasn’t theoretical anymore. It was repeatable—and it was working.

VI. Recent History: Acceleration & Key Inflection Points (2016-2025)

From 2016 onward, you can see the Ennis playbook reach its mature form. The company entered this stretch as a proven consolidator. It came out the other side as the clear leader in its corner of printing—still operating in a category with structural headwinds, but increasingly positioned to be the last, biggest, best-run player standing.

The 2019-2022 Acquisition Surge

In November 2022, Ennis announced the acquisition of School Photo Marketing in Morganville, New Jersey. School Photo Marketing provides printing, yearbook publishing, and marketing-related services to more than 1,400 school and sports photographers serving schools around the country.

On its face, school photography sounds like a left turn from “business forms.” But strategically, it fits the Ennis template: printed products moving through a specialized channel, where service, reliability, and breadth matter as much as unit economics. Ennis framed the deal as an opening to “service this new channel with products produced through Ennis manufacturing operations,” and noted that School Photo Marketing operates through a wholesale manufacturer–distributor–end user structure similar to Ennis’s existing model.

In other words: new vertical, familiar plumbing.

The 2023-2025 Transformation

By 2023 and 2024, Ennis was still doing what it had always done—quietly picking off capabilities and footprint where it made strategic sense. In June 2024, the company acquired Printing Technologies Inc. And in April 2025, Ennis announced another deal: Northeast Envelope, a trade manufacturer based in Old Forge, Pennsylvania. It was Ennis’s first acquisition in nearly a year, following PTI and earlier Pennsylvania buys like Eagle Graphics and Diamond Graphics. Over roughly that mid-2023 to mid-2024 window, the company had made multiple acquisitions, continuing to add density and range without changing its basic operating model.

Ennis described Northeastern Envelope (founded in 1966) as a leading trade manufacturer of a wide variety of envelopes. Beyond custom converting and manufacturing, the company inventories hundreds of double- and single-window envelopes, enabling same-day shipping.

The strategic point was straightforward: envelopes are a high-frequency, operationally demanding product category, and this strengthened Ennis’s envelope manufacturing capabilities in the eastern U.S.—a geography where speed and proximity matter.

Then came the deal that really underlined Ennis’s position in the industry.

In 2025, Print & Promo Marketing ranked Ennis as the largest trade printer in the United States, and ranked CFC Print & Mail as the 15th largest. In November 2025, Ennis acquired CFC Print & Mail—based in Grand Prairie, Texas and founded in 2009—a wholesale provider of business-document printing, mailing, and commercial print solutions.

Ennis’s own framing made the logic clear: CFC brought scale, distribution depth, and the ability to turn a high volume of orders quickly. Keith S. Walters called out CFC’s “innovation, service and efficiency,” and positioned the deal as a fit with Ennis’s priorities around quality, responsiveness, and national scale.

What makes this acquisition especially telling is what it says about the market. Even after decades of consolidation, Ennis could still buy meaningful competitors—and not just tiny tuck-ins. This was the leader absorbing another ranked player, further tightening its grip on the trade print landscape.

The Carbonless Paper Crisis (2024-2025)

Even the best-run operators get tested by supply shocks. In 2024 and 2025, Ennis faced a serious one: the announced closure of the only domestic producer of carbonless paper.

Management’s response was very Ennis: prepare early, use the balance sheet, and protect the customer relationship. The company said it had “strategically used cash to increase inventory” in anticipation of the closure, then began working that inventory down through sales while transitioning to alternative sources. It noted it did “not anticipate any supply disruptions” as it moved to foreign suppliers.

Ennis also pointed directly to the Pixelle mill closure in Chillicothe, Ohio, describing it as removing all carbonless roll paper produced in North America and disrupting the traditional forms market. The company’s message to customers was essentially: we’ve seen this movie before. Ennis said it would cover customer needs “in the same fashion as we did during the pandemic,” leaning on multiple-plant inventory and consigned inventories to buy time while building new supplier lanes.

The takeaway isn’t that the paper market got easier. It’s that Ennis behaved like the consolidator it is: the company with the planning discipline—and the inventory posture—to be reliable when the market gets chaotic.

Market Challenges & Response

Supply disruptions weren’t the only issue. Demand softened, too.

Ennis attributed part of the slowdown to customers overstocking during prior paper shortages, then pulling back. The company said it began seeing “a softening of orders in some of our product lines” starting in the fourth quarter of fiscal 2023—an early warning that carried into fiscal 2024 and beyond.

For the fiscal year ended February 28, 2025, Ennis reported revenue of $394.6 million, down from $420.1 million the prior year. Gross profit dollars declined as well, but gross margin percentage held essentially flat at just under 30%. Net earnings were $40.2 million, compared to $42.6 million the prior year.

That pattern is the story: volumes can slide in this industry, but Ennis fights to hold the economics steady. Keeping margins stable while revenue falls is exactly what you’d expect from a company that treats cost systems, plant discipline, and integration as a core competency.

And then, in the most recent quarter ending November 30, 2025, performance improved: revenue ticked up slightly year over year, earnings per share increased, and gross margin expanded meaningfully (to 31.9% from 29.3% in the comparable quarter). Ennis pointed to continued operational execution, with the CFC Print & Mail acquisition now inside the tent.

So by the end of 2025, the picture was sharp. The core market still faced secular headwinds and periodic shocks. But Ennis kept doing what it has done for decades: absorb competitors, broaden capabilities, and run a tighter operation than the rest of the field.

For investors, that leaves the enduring question—one that has defined the entire Walters era: can acquisition-driven scale and operational discipline outpace organic decline, and still produce attractive returns over time?

VII. The Business Model & Competitive Positioning Today

To understand Ennis’s competitive position, you first have to understand the weirdly powerful niche it occupies: the wholesale trade printer. Ennis doesn’t sell to consumers. It doesn’t sell directly to end businesses, either. It sells to distributors—full stop. And that single choice changes the entire economics of the company.

Ennis has leaned into that identity for decades. As the company puts it, its strength is “dedication to our distributor partners” and an expansive network that gives them “endless possibilities.” Today, that network includes more than 1,850 employees serving over 40,000 distributors worldwide. Distributors get the best of both worlds: local, relationship-driven service through Ennis’s regional presence, plus the purchasing power and operational scale of a much larger enterprise.

That “over 40,000 distributors” figure is doing a lot of work. It means Ennis isn’t hostage to any single customer. Lose one distributor, and the financial impact is limited. But it also means loyalty is earned every day—through service levels, pricing, and, most importantly, product breadth.

Those distributors come in many flavors: business forms dealers, stationers, printers, computer software developers, and advertising agencies across the United States. It’s a wide channel. Ennis’s job is to be the dependable engine behind it.

The wholesale model also creates a strategic advantage that’s easy to underestimate: Ennis doesn’t compete with its own customers. A printer that sells direct to businesses is always tempted to go around the distributor when a big account appears. Ennis avoids that conflict by staying wholesale-only. Distributors can recommend Ennis without worrying Ennis will turn around and steal the relationship.

If it can be printed or printed on, Ennis has it!

That line isn’t just marketing. It’s strategy. Ennis has spent decades building a portfolio so wide that a distributor can consolidate purchasing with Ennis across category after category. And the more a distributor buys from Ennis, the stickier the relationship becomes. Switching suppliers isn’t just swapping out one product—it’s reworking a large chunk of the distributor’s workflow.

In practice, that portfolio spans business forms and printed products like snap sets, continuous forms, laser cut sheets, tags, labels, envelopes, integrated products, jumbo rolls, and pressure-sensitive products. The company operates roughly 59 plants across 20 states, and many of its best-known names reflect where acquisitions and niches meet: Adams McClure in advertising products; Admore, Folder Express, and Independent Folders in presentation folders; Ennis Tag & Label and Allen-Bailey Tag & Label in tags and labels; Trade Envelopes, Block Graphics, Wisco, and National Imprint Corporation in envelopes.

Those 40-plus brands matter because Ennis doesn’t try to erase what it buys. The local or niche reputation often stays intact, while the underlying business gains Ennis’s procurement scale, manufacturing discipline, and distribution reach.

Financially, Ennis is not a high-flying tech story. It’s something rarer: a steady cash generator in a challenged industry. The company has cited an 18.4% non-GAAP EBITDA margin and has operated with no debt. As management noted, it maintained $32.0 million in cash with no debt.

That debt-free posture is one of Ennis’s defining characteristics. While many companies lean on leverage to juice returns, Ennis has played a more conservative—and more flexible—game. No debt means fewer constraints in a downturn, and it means the company can act when opportunities appear.

Management has been explicit about the philosophy: it believes it has “one of the strongest balance sheets in the industry,” and that profitability and cash reserves allow it to fund operations and acquisitions without borrowing—while still returning substantial capital to shareholders. In one quarter alone, the company said it returned $72.3 million through dividends, including a special dividend of $2.50 per share. And it also noted that, if a larger acquisition ever demanded it, Ennis expects it could access credit in a timely way.

Then there’s the dividend record: 205 consecutive quarters of dividend payments. That’s more than 51 years of checks going out—through recessions, industry disruption, and every chapter of the forms-to-whatever-comes-next transition.

For investors, that’s the Ennis proposition in a sentence: a long-lived, cash-generative company in a declining industry that tries to turn decline into an advantage through disciplined consolidation and disciplined capital allocation. The open questions are the ones that have hovered over the whole Walters era: how long can Ennis keep finding attractive acquisition targets, and can the roll-up machine outpace the category’s long-term gravity?

VIII. Strategic Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Ennis is an old-school manufacturer running a modern-day consolidation play. To see why it works—and where it’s exposed—it helps to look at the business through two lenses: Porter’s Five Forces (what the industry does to you) and Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers (what you do that others can’t easily copy).

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Starting a wholesale trade printer at Ennis’s scale is brutally hard. Yes, the equipment is expensive—but the real barrier is the channel. A new entrant would have to earn the trust of thousands of distributors who make their living on reliability and repeat orders. Those relationships are sticky, the sales cycle is slow, and distributors don’t switch suppliers lightly.

Then there’s cost. Ennis buys paper, ink, and substrates at volumes that smaller players can’t match. Even if a newcomer could match quality, they’d likely be structurally more expensive.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MEDIUM-HIGH (with recent vulnerabilities)

Ennis has been clear-eyed about the risks here: digital technologies continue to erode demand for printed business documents; acquisitions carry integration risk; and the company faces a limited number of suppliers and ongoing variability in paper and other raw material prices.

The carbonless paper situation put a spotlight on supplier power. With the only domestic producer shutting down, Ennis had to pivot to foreign sources. When key inputs are concentrated, suppliers gain leverage—on price, on lead times, and on terms.

Ennis can blunt some of this through scale (it’s an important customer) and by spreading risk across many product categories. But this force doesn’t disappear. It’s one of the structural pressures of the business.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM

Ennis’s customer base is massive—more than 40,000 distributors—so no single buyer can dictate terms. That diversification is a quiet strength.

But distributors still have options: regional printers, specialized niche shops, and, in some cases, internal print capabilities. In the most commoditized categories, price becomes the battlefield fast.

Ennis fights back with two weapons that matter in wholesale: breadth and service. If you can reliably cover more of a distributor’s catalog—at consistent quality, with fast turnaround—you become less of a vendor and more of an operating dependency.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH (but stabilizing)

This is the force that created the whole Ennis strategy in the first place. PDFs, email, electronic forms—digital is a substitute for paper, and the secular decline in traditional business forms has been the reality for decades.

But “print is dying” isn’t evenly true across all print. Some categories hold up: security documents, specialized tags and labels tied to identification and compliance, and promotional products where physical materials still matter. Ennis has deliberately nudged its mix toward the parts of print that don’t vanish just because software got better.

Competitive Rivalry: MEDIUM

The industry is still competitive, especially in commodity categories where price pressure is constant. But the rivalry has changed shape over time: consolidation has reduced the number of large-scale players, and Ennis has often been the one doing the consolidating.

That matters because buying competitors is a form of rivalry management. Every acquisition can remove a price-cutting rival, add capacity and customers, and increase Ennis’s leverage with suppliers and distributors.

Hamilton's Seven Powers

Scale Economies: STRONG

By 2025, Print & Promo Marketing ranked Ennis as the largest trade printer in the United States, and CFC Print & Mail as the 15th largest. Ennis’s acquisition of CFC added scale, distribution depth, and quick-turn capabilities for high-volume orders—further strengthening Ennis’s position in business products and commercial print.

At this size, scale shows up everywhere: lower input costs, fixed costs spread across more volume, and the ability to invest in systems and equipment smaller competitors can’t justify. In a mature industry, scale isn’t just nice to have—it’s survival gear.

Network Effects: MODERATE

Ennis isn’t a software platform, but there’s a real flywheel in its distributor network. The broader the product catalog, the more attractive Ennis becomes as a one-stop partner. As more distributors rely on Ennis, the company gets more volume, more data, and more justification to add capacity and expand offerings.

It’s not a winner-take-all network effect, but it is a reinforcing loop that helps the biggest player keep getting stronger.

Counter-Positioning: WEAK

Ennis isn’t winning by inventing a new model that incumbents can’t respond to. It’s winning by running a traditional consolidation strategy with more discipline than the rest of the field. That’s valuable—but it doesn’t come with the built-in “incumbents can’t copy this” protection you’d see in a true counter-positioning story.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

Ennis creates stickiness through operational integration. For example, Printing Technologies, Inc. (PTI), acquired during the second quarter of the prior year, was fully integrated into Ennis’s ERP systems and performing well. That kind of systems alignment is part of what makes Ennis hard to replace once a distributor has built ordering habits around its catalog, service expectations, and workflows.

Switching isn’t impossible. But it’s annoying. And in wholesale, “annoying” is often enough to keep business in place.

Supplier risk also feeds into this dynamic. When the sole U.S. mill producing carbonless paper announced its closure, Ennis invested in additional inventory as a buffer while pivoting to other sources. In a disruption, the supplier who can still ship becomes the supplier you keep.

Branding: WEAK

This is a wholesale B2B business. End-consumer brand recognition doesn’t matter much, and Ennis doesn’t win because a purchasing manager loves the Ennis logo.

The brands that do matter tend to be the acquired ones—names with recognition inside their niches (Admore, Allen-Bailey Tag & Label, Trade Envelopes, and others). That’s helpful at the product-line level, but it’s not the kind of broad branding power that creates durable pricing leverage on its own.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Keith Walters brought deep experience running manufacturing plants and participating in more than 37 acquisitions, with a track record of making integrations work. Over time, that turned into something more than personal experience: an institutional capability.

The acquisition and integration playbook—supported by training curricula, standard costing systems, and management tools that Margaret Walters helped develop—functions like a hard-to-copy resource. It’s not patented. But it’s embedded. And it’s exactly the kind of “know-how advantage” that weaker consolidators struggle to replicate.

Process Power: STRONG

Ennis’s biggest advantage is not a product. It’s a process: buying companies at sensible prices, integrating them quickly, standardizing how they’re run, and extracting real operational improvements.

That sounds simple. It isn’t. Doing it once is hard; doing it dozens of times, across many plants and brands, while maintaining service levels is rarer. Ennis has spent decades refining this muscle, and that accumulated learning curve is a meaningful moat.

Key Performance Indicators

For anyone tracking whether the Ennis machine is still doing what it’s supposed to do, two metrics matter most:

-

Gross Profit Margin: A quick read on whether Ennis is holding the line on pricing and executing on cost control. Around the 30% range has been a marker of healthy performance; meaningful deterioration would suggest competitive pressure, input-cost stress, or integration issues.

-

Organic Revenue Growth (ex-acquisitions): Acquisitions can mask the underlying trend. Persistent organic decline would imply the roll-up is mainly buying time. Stable—or improving—organic performance would be a signal that Ennis’s breadth, service, and scale are keeping the core engine healthier than the industry headline suggests.

IX. Bull vs. Bear Case & Future Outlook

Every business like Ennis forces you to hold two ideas in your head at the same time: the industry is in secular decline, and yet this particular company has found ways to make that decline work in its favor. The investment case swings on which side of that tension you think wins.

Bull Case

The Proven Consolidator

Ennis has spent nearly three decades proving it can do the hardest part of a roll-up: not just buying companies, but integrating them and improving them. In an industry filled with small operators—often with aging owners and no clear succession—Ennis has positioned itself as the natural buyer.

After the acquisition of Printing Technologies Inc., Walters reiterated the posture that has defined the company’s strategy: keep pursuing acquisitions as long as they make financial sense. In his words, Ennis’s profitability and strong financial condition allow it to fund acquisitions without incurring debt, while still expecting timely access to credit if a larger opportunity ever requires it.

Balance Sheet Strength

Ennis’s debt-free balance sheet gives it two advantages at once. Defensively, it can ride out downturns without lenders dictating terms. Offensively, it can move quickly when sellers appear—without having to dilute shareholders or accept restrictive covenants just to get a deal done.

Resilient Product Categories

“Print is dying” is an overstatement—but it’s not wrong everywhere equally. Security documents like checks and other negotiable instruments have staying power. Tags and labels tied to compliance and product identification don’t vanish just because someone adds software. And some promotional products still work precisely because they’re physical. Ennis has steadily pushed its mix toward these more defensible categories.

Income Generation

Ennis pays dividends quarterly. The last paid amount was $0.250 on Nov 07, 2025, and as of today the dividend yield (TTM) is 6.89%.

For income-focused investors, that’s the headline: a high yield supported by steady cash generation. And the $2.50 per share special dividend in November 2024 signaled something else too—management is willing to return excess capital when it doesn’t see better uses for it.

Last Man Standing

There’s a cold, strategic logic to being the dominant consolidator in a declining market. When competitors exit—by selling, going bankrupt, or simply shutting down—someone inherits the demand that remains. If the industry ultimately becomes small enough to support only a handful of scaled operators, being the biggest, most efficient, and most reliable of those operators can be a very good place to be. The bull case is that Ennis becomes that “last man standing” and runs a smaller market at attractive economics for a long time.

Bear Case

Secular Decline Is Real

Ennis itself doesn’t sugarcoat the risks. It has pointed to the erosion of demand for printed business documents from digital technologies, uncertainty around completing and integrating acquisitions, and the limited supplier base and price volatility for paper and other raw materials.

And the underlying trend isn’t ambiguous. Each year, fewer invoices get printed. Fewer forms get filled out by hand. More workflows move to digital-only systems. The question isn’t whether demand is shrinking. It’s whether Ennis can keep shrinking gracefully—while still earning strong returns.

Acquisition Targets Drying Up

The roll-up machine only works if there are deals worth doing. Over time, consolidation reduces the pool. And as the industry shrinks, the number of healthy, attractively priced targets can shrink with it. The CFC Print & Mail acquisition—buying a ranked competitor—can be read as a sign that the remaining meaningful targets may be getting harder to find.

Revenue Trajectory

For the fiscal year ended February 28, 2025, Ennis reported revenue of $394.62 million, down 6.07% from $420.11 million the prior year. Earnings were $40.22 million, down 5.58%.

Even with acquisitions, the top line moved lower. That’s the bear case in one chart: organic decline is strong enough that deals aren’t fully offsetting it. If that continues, Ennis has to run faster just to stay in place—and eventually, there’s a limit to how fast you can buy.

Customer Concentration Risk

Ennis’s distributor base is huge, which limits single-customer risk. But the model concentrates exposure in the channel itself. If distributors consolidate, change buying patterns, or shift volume to other suppliers, Ennis could feel the effects more quickly than the “40,000 distributors” figure suggests.

Management Succession

Keith Walters has led Ennis since 1997. The acquisition engine, the integration discipline, and a lot of the industry relationships have been built under his watch. He has also indicated he is considering future board opportunities as his commitments at Ennis become more predictable. Whenever that transition comes, it creates uncertainty: can a new CEO keep the same cadence, discipline, and operating rigor that made the Walters era work?

The Verdict: Classic Value Trap or Hidden Gem?

Ennis resists a simple label. It can look like a value trap: a company in a declining industry with a shrinking revenue base. It can also look like a hidden gem: disciplined capital allocation, consistent cash generation, and a leadership position built through decades of consolidation.

One way to frame it is the “cockroach theory.” Business forms have been pronounced dead for decades. And yet Ennis keeps generating profits, paying dividends, and buying competitors. At some point, repeated survival stops being a fluke and starts looking like a capability.

Where this goes from here comes down to capital allocation. If Ennis keeps generating cash and deploying it well—into accretive acquisitions, smart repurchases, and sustainable dividends—shareholders can do fine even if the industry keeps slowly contracting. If attractive deals dry up and the company can’t convert cash into productive returns, the thesis weakens fast.

X. Epilogue: Lessons for Founders & Investors

The Ennis story offers a handful of lessons that travel well beyond printing.

Sometimes, survival is the strategy. Not every company gets to pivot into a growth market. Not every legacy manufacturer can reinvent itself as a software platform. If you’re in a structurally declining industry, the “win” might be disciplined decline management: protect margins, generate cash, keep customers happy, and outlast the weaker players. Ennis shows that harvesting a business isn’t the same thing as giving up. Done well, it can be a decades-long value-creation strategy.

Boring businesses can compound wealth quietly. Ennis has maintained dividend payments for 52 consecutive years. That’s not a flashy statistic—it’s a statement of durability. While the world pays attention to high-growth stories, a lot of wealth gets built the slow way, in industries that never trend on social media. Business forms printing will never be cool. But for shareholders who owned Ennis through the Walters era, the combination of endurance, consolidation, and dividends has been meaningful.

Disciplined M&A is a superpower in fragmented industries. When an industry is filled with small operators, especially owner-run companies facing succession issues, consolidation isn’t just possible—it’s inevitable. The difference is who does it well. The hard part isn’t buying; it’s integrating. Ennis’s edge wasn’t simply access to targets. It was a repeatable integration playbook that could capture synergies without breaking what made the acquired businesses worth buying in the first place.

In some contexts, process beats product. In fast-growing markets, product innovation is the engine. In mature or declining markets, execution becomes the moat. Ennis didn’t win because it had dramatically better forms than anyone else. It won because it got exceptionally good at the unsexy stuff: standardizing operations, managing costs, integrating plants, and delivering reliably through the distributor channel. Over time, that operating discipline mattered more than any single product breakthrough.

Don’t underestimate institutional knowledge. A century-plus of operating history adds up to something you can’t buy off the shelf: deep familiarity with distributors, suppliers, category economics, and manufacturing realities. That doesn’t make Ennis invincible. But it does create a kind of advantage that’s hard to copy and even harder to measure—until you see who still performs when conditions get ugly.

Finally: know when to harvest, and when to reinvest. Ennis didn’t try to become a tech company. It didn’t chase a narrative. It accepted the industry reality, then used capital allocation and consolidation to make that reality work in its favor. That clarity—knowing what you are, what you aren’t, and how you’ll create value anyway—might be the most important lesson in the entire story.

For long-term investors, Ennis is an unconventional case: a company that turned adversity into advantage and decline into a framework for disciplined growth-by-acquisition. Whether the next chapter produces great returns will depend on execution investors can’t control. But if the last few decades prove anything, it’s that writing Ennis off has been a bad bet.

XI. Further Reading & Resources

If you want to go deeper on Ennis—and on the kind of “boring” consolidation strategy that can quietly compound for decades—these are the best places to start:

-

Ennis Inc. 10-K Annual Reports (2020-2025) – The clearest window into how Ennis thinks: acquisition rationale, segment performance, market headwinds, and the details that rarely make it into press releases.

-

Company History at Ennis.com – A surprisingly useful timeline of the company’s 115-year evolution, including many of the acquisitions that built today’s footprint.

-

Print & Promo Marketing Magazine – Industry context that helps you understand where Ennis sits in the trade-print ecosystem and how competitive dynamics are shifting.

-

"The Outsiders" by William Thorndike – Not about printing, but about the skill Ennis has leaned on for years: capital allocation. A great lens for judging whether “disciplined and boring” is actually brilliant.

-

Ennis Investor Presentations – Management’s own framing of strategy, operating priorities, and what they’re seeing in demand, pricing, and supply.

-

Industry Reports on Commercial Printing – IBISWorld and similar firms cover the broader commercial printing market and help separate company execution from industry gravity.

-

Keith Walters Interviews in Trade Publications – Useful color on the acquisition mindset and integration discipline from the person who ran the playbook for decades.

-

"Capital Allocation" by Tobias Carlisle – A framework-driven way to think about roll-ups, buy-and-build models, and when they create value versus when they just mask decline.

-

Historical Analysis of the Business Forms Industry (1990s-2000s) – Trade and academic sources from the era when “paper to digital” stopped being theory and started showing up in sales trends.

-

Seeking Alpha and Similar Investment Platforms – Not primary sources, but a good way to pressure-test the bull and bear cases and see what skeptics and supporters are focusing on.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music