DigitalOcean: The Developer's Cloud

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

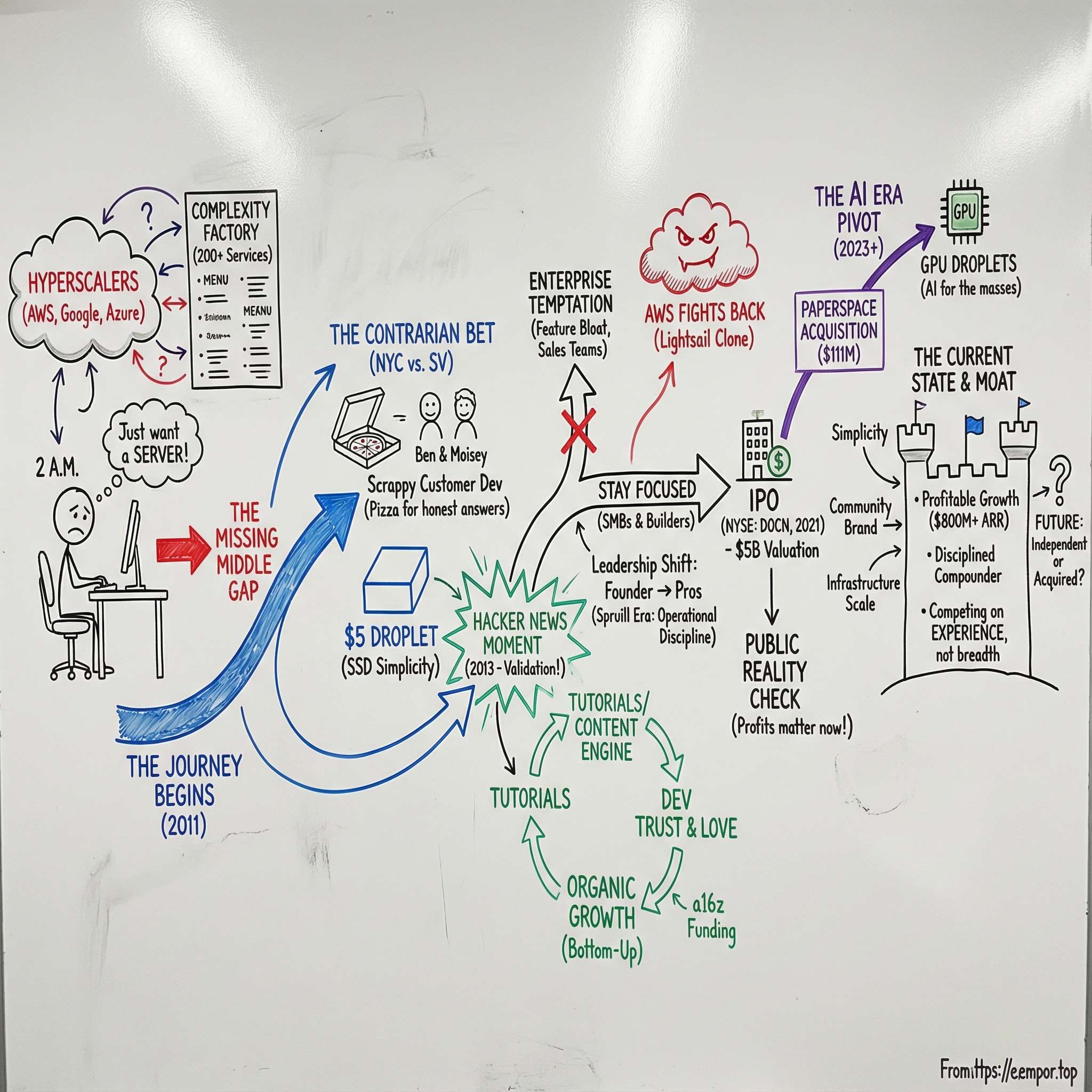

Picture a developer at 2 a.m., trying to ship a side project, staring down an AWS console that feels like it has more options than a Cheesecake Factory menu. They don’t need 200 services. They need one thing: a server, up and running, without a weekend of reading docs.

That frustration—the gap between overwhelming cloud complexity and what most developers actually need—is the emotional core of DigitalOcean’s origin story.

By the early 2010s, cloud computing was already being defined by giants. Amazon, Google, and Microsoft were building platforms that increasingly catered to enterprise demands: more services, more knobs, more edge cases, more ways to do everything. Ben Uretsky looked at that landscape and made a contrarian call: don’t chase the enterprise. Serve the developer.

Several years later, DigitalOcean had become one of the largest cloud platforms in the world for individuals, startups, and small businesses—the people who wanted infrastructure that felt straightforward, not intimidating.

So the question driving this episode is simple on its face and kind of wild in practice: how did five founders in New York build a cloud infrastructure company valued at around $5 billion while competing—directly or indirectly—with AWS, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure, three of the best-capitalized companies in modern business?

The answer comes down to a tension that’s been in cloud computing from day one: simplicity versus complexity. Hyperscalers kept piling on services—AWS now offers more than 200—because their customers asked for them and because that’s how you win the enterprise. DigitalOcean made the opposite bet: that millions of developers wanted a cloud that stayed out of their way.

In November 2025, DigitalOcean CEO Paddy Srinivasan put it like this: "DigitalOcean's unified agentic cloud is driving accelerated momentum in Q3. Revenue increased 16% year over year and we delivered the strongest incremental organic ARR in our history." Nearly 14 years after launch, it’s both validation and a reminder of the challenge. DigitalOcean proved it could survive. The question is whether it can keep thriving as the giants keep moving downmarket.

What makes this story so fun—and so instructive—is how often DigitalOcean did the opposite of what the playbook said. Instead of six-figure enterprise deals, they went after developers swiping a credit card for $5 a month. Instead of a feature arms race, they competed on clarity and ease. Instead of Silicon Valley, they built in New York. Again and again, they zigged while the industry zagged.

II. The Cloud Context: AWS Changes Everything (2006–2010)

Before we can understand what DigitalOcean disrupted, we have to remember what it felt like to launch on the internet before “the cloud” was a default setting.

In 2005, starting an online business meant you were doing, at least in part, a hardware business. You bought physical servers, found a data center to rack them, paid for bandwidth, paid for redundancy, and hired someone who knew how to keep the whole thing alive. You planned capacity months in advance, spent real money upfront, and then crossed your fingers that your traffic forecasts weren’t fantasy. And when something broke at 3 a.m. on a Saturday, it wasn’t a metaphor. It was your phone ringing.

This was the era of pets-not-cattle infrastructure: servers had names, histories, and weird quirks everyone learned to work around. It could be oddly satisfying in a craftsman way. It was also slow, expensive, and totally mismatched with the pace of software.

Then, in 2006, AWS flipped a switch that changed the entire trajectory of computing: the first beta of Amazon EC2.

In hindsight, it’s hard to overstate what EC2 introduced. Instead of buying computers, you rented them. Instead of provisioning for peak and hoping you guessed right, you spun servers up when you needed them and shut them down when you didn’t. The “EC” in EC2—Elastic Compute—wasn’t branding fluff. It was the thesis: compute should stretch and snap back as your workload changes.

That flexibility created the modern cloud. But it also came with a catch, especially early on: EC2 wasn’t built for hobbyists or tiny teams. It was built to solve Amazon-sized problems. Which meant it could do almost anything… but simple things weren’t always simple. To launch what felt like “just a server,” you had to navigate an increasingly intricate maze of security settings, networking concepts, permissions, storage choices, instance types, and billing rules that could feel less like product design and more like compliance training.

AWS had essentially invented a new market and, in the process, built one of the most important businesses of the century. But it also left a ton of people behind.

Because at the same time, the modern developer world was taking shape. GitHub launched in 2008 and made collaboration the default. Heroku showed up and made deployment feel magical for a certain kind of developer. The indie web exploded—side projects, startups, experiments, all shipping faster than ever.

And those developers had a very specific problem. Shared hosting was cheap and easy, but it hit a ceiling fast. Dedicated servers were powerful, but required money, planning, and ops expertise. AWS was flexible, but felt like it was speaking a different language—one designed for enterprises with teams dedicated to running infrastructure.

So a “missing middle” emerged: millions of developers who were sophisticated enough to need real cloud infrastructure, but not staffed—or funded—to wrestle with enterprise-grade complexity. They wanted the power of EC2 without the cognitive overhead. They wanted infrastructure that felt like a tool, not a second job.

That gap is the context DigitalOcean was born into. By the time Ben and Moisey Uretsky started looking seriously at the cloud as a business opportunity, it wasn’t that the market needed another AWS. The market needed an on-ramp.

And that’s a pattern worth noticing: the biggest opportunities often aren’t about inventing a new category. They’re about taking a massive category that already exists and serving the customers everyone else is accidentally ignoring. In the late 2000s, cloud infrastructure was the future. But for a huge slice of developers, it still wasn’t usable. DigitalOcean’s entire story starts right there.

III. The Founding Story: Ben & Moisey's Bet (2011–2012)

Ben and Moisey Uretsky didn’t come up through the usual Silicon Valley pipeline. They grew up in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, in a Russian immigrant family, learning computers the unglamorous way: by wanting them badly, not having much, and teaching themselves anyway. As Ben later put it: “We came to America, and we were always passionate about computers, but we were really poor. We got a computer when we were 13 and used AOL and a dial-up modem.”

Their family immigrated from Russia when Ben was five. The brothers went on to attend Stuyvesant High School—one of New York City’s most selective public schools, where admission is earned through a competitive exam. It’s a detail that fits the broader theme: no shortcuts, just grinding through gates.

Before DigitalOcean, they ran ServerStack, a managed hosting business. For eight years, it gave them a front-row seat to the real day-to-day pain of infrastructure: customers who needed help, systems that broke at the worst times, and an industry that slowly squeezed differentiation out of everything. ServerStack’s annual revenue fluctuated between $3 million and $7 million. But as competition intensified—Rackspace looming large—being “better” wasn’t enough to keep winning.

Ben remembered it this way: “I launched my first company, ServerStack, a managed hosting provider, but despite having newer hardware and superior support at a lower cost, we were losing out to the competition.”

That’s the moment the lesson lands. If you’re only incrementally better, the market eventually treats you like a commodity. To survive, you need to be meaningfully different.

So the Uretskys stepped back and looked at where the world was going. Cloud computing was clearly becoming the default way to build modern web applications. The problem was that for most developers, it still felt like an obstacle course. To figure out what developers actually wanted, they did something wonderfully low-tech: they walked around New York’s startup neighborhoods with boxes of pizza and asked CTOs to talk. One slice for one honest answer. Then they built around what they heard—simple, elegant infrastructure at a scale developers could trust.

It wasn’t polished market research. It was scrappy customer development. And it worked because they weren’t guessing. They were listening.

DigitalOcean was founded on June 24, 2011. The founding team was Ben and Moisey Uretsky, Jeff Carr, Alec Hartman, and Mitch Wainer.

And in a detail that still feels very DigitalOcean: Moisey met Mitch Wainer through a Craigslist job listing. No warm intros, no pedigree signaling—just talent finding talent in the places other people weren’t looking.

From the start, the technical and product choices were intentionally contrarian. DigitalOcean built on KVM, a simpler, Linux-native hypervisor. They bet on SSDs when that was still an expensive choice, because speed mattered to the experience. And instead of asking developers to decode a matrix of instance families and confusing acronyms, they sold virtual machines with a friendlier name and a clear starting point: “Droplets,” beginning at $5 a month.

Even the branding carried the strategy. “Droplet” made infrastructure feel approachable—small, simple, tangible—in a world full of intimidating terminology. The company name, “DigitalOcean,” was meant to evoke something broad and powerful, without sounding like an enterprise product catalog.

Ben described the early magic like this: “It took us about six months to build DigitalOcean. When we spun up that first server, I was like ‘this is amazing, all I want to do is build a Rails app and spin up some more servers.’ We knew that if we could deliver that feeling to other customers we were on to something.”

By early 2012, they were still trying to line up funding when someone suggested Techstars New York. There was one catch: the deadline was 24 hours away. They pulled it together, applied, and landed an invite to intro day.

DigitalOcean ultimately joined TechStars’ 2012 accelerator in Boulder, Colorado, and the founders moved out there to build. By the end of the program in August 2012, they had signed up 400 customers and launched around 10,000 cloud server instances.

And through all of this, the broader posture stayed consistent: they weren’t trying to outspend anyone. They were trying to out-focus them. They chose to bootstrap and build in New York instead of chasing the gravity of Silicon Valley—leaning on what they already had: deep infrastructure instincts, empathy for developers, and an obsession with making the cloud feel like a tool you could just pick up and use.

IV. Launch & Early Traction: The HackerNews Moment (2012–2013)

Every great tech company seems to have a “lightning in a bottle” moment—the day when a product stops being something a small team is willing into existence and becomes something the internet is pulling out of them. For DigitalOcean, that day was January 15, 2013.

On paper, the trigger sounds like an infrastructure footnote: DigitalOcean became one of the first cloud-hosting companies to offer SSD-based virtual machines. In reality, it was a strategic dare. SSDs were meaningfully more expensive than traditional hard drives, and DigitalOcean wasn’t a hyperscaler with infinite margin to play with. If they were going to move the entire platform to SSDs, they had to make it up in volume. The bet was straightforward and brutal: performance and simplicity would pull in customers fast enough to cover the higher cost.

And remember—despite the brand becoming synonymous with “SSD-only” later, DigitalOcean didn’t start there. In 2012, they were still using regular hard drives. SSDs weren’t even the obvious next step; they were a way to differentiate in a market where “cheap VPS” was already crowded. So they went for it.

Then the story hit. TechCrunch ran the first piece about the move—Romain Dillet wrote it—and Uretsky later said he remembered the exact date because that was the day he realized the idea was going to work. Later that same day, the post made its way to Hacker News.

And Hacker News didn’t just upvote it. It validated the entire product philosophy in public, in the most demanding corner of the internet. One highly upvoted comment captured what people were feeling: “It’s that the web interface, and process for starting a ‘droplet,’ is dead-simple and super-elegant, their support docs are comprehensive and easy to use, and they even do things like let you manage your own DNS records. And it all just works. Digital Ocean is 100x easier and quicker to use than AWS, without exaggeration. It’s easy to start a hosting provider—it’s really hard to make one that is also really high quality, intuitive and easy to use, and then cheap on top of it.”

That flood of attention immediately created a second, less glamorous problem: they weren’t ready for it.

DigitalOcean’s infrastructure had been built for steady, controlled growth. Now it was getting stress-tested by a surge that looked a lot more like a step function. Demand was exploding, and the team had to scale the business as fast as it was scaling the servers. Those early months pushed them to their operational limits.

But the way they responded revealed something important about what DigitalOcean actually was. They didn’t just add capacity. They doubled down on developer empathy—and started building what would become a compounding advantage: education as a growth engine.

DigitalOcean began publishing deeply practical, step-by-step tutorials for the exact tasks their customers were trying to do. Set up Nginx. Configure MySQL. Install Ruby on Rails. Not marketing fluff, not thin documentation—real guides written to help someone ship. By August 2014, DigitalOcean said it had more than 1,000 vetted tutorials. The content did three things at once: it helped customers succeed, it brought in organic traffic, and it turned the brand into something developers trusted.

Capital followed. In July 2013, the company raised $3.2 million in seed funding led by IA Ventures.

And the traction was already getting hard to ignore. At the beginning of 2013, DigitalOcean had only a couple thousand customers. Not long after, it had grown to more than 100,000 active customers, running thousands of physical servers, signing up just under a thousand users per day—and it was profitable.

That last part matters. In an era where “growth at all costs” was becoming the default religion, DigitalOcean was showing something rarer: a cloud product that could grow quickly without being a financial black hole. The $5-per-month Droplet wasn’t just a clever entry point. It worked.

As Ben Uretsky put it: “We’re the 9th largest infrastructure provider worldwide and it’s such a capital intensive industry. Our users can buy a slice of a physical machine for a short period of time for a fraction of a penny. Securing this capital is very important to make sure that we stay ahead of our customers’ demand.”

V. Hypergrowth & The Developer Flywheel (2013–2015)

By 2014, DigitalOcean had something most startups never touch: real product-market fit, with developers spreading it for them. The internal question stopped being “will this work?” and became “can we keep up?”

The outside world noticed too. Andreessen Horowitz led a $37.2 million round that valued the company at $153 million, with IA Ventures and CrunchFund participating. Peter Levine joined the board.

Levine later described meeting Ben and Moisey Uretsky as one of the most memorable moments of his venture career. He went in thinking cloud hosting was already owned by the “big guys,” and that a scrappy upstart couldn’t possibly matter. Two things changed his mind: the traction, and the founders’ single-minded commitment to “building a cloud that developers love.”

Ben was blunt about how intentional the raise was. “We wrote a wishlist. We had about 10 different VCs that we wanted to reach on the West Coast,” he said. “Ultimately, Andreessen Horowitz walks away with the prize and they were actually number one on our list. They represent that perfect mix of capital and strategic investment. They share a similar view of the world where the developers have much more power than they used to.”

That’s what made the a16z round such an inflection point. It wasn’t just money to buy more servers. It was a stamp of approval on the thesis that had powered DigitalOcean from day one: win developers, and you can build a real company—without starting in the enterprise.

Levine connected the dots from his own experience. “I’m on the board of GitHub as well, and the power of the community became really evident to me at GitHub. Users sense the empowerment,” he said. “DigitalOcean has this very large community of users so they get a lot of feedback. It’s very uncommon for a startup.”

At the same time, DigitalOcean started turning its early momentum into global reach. In December 2013, it opened its first European data center in Amsterdam. Over the course of 2014, it added new locations in Singapore and London. The play was simple: keep latency low, keep the experience consistent, and meet developers where they were—everywhere.

Then came another big check. In July 2015, DigitalOcean raised $83 million in funding led by Access Industries, with Andreessen Horowitz participating again.

And the scale was starting to look surreal. In May of that year, Netcraft ranked DigitalOcean as the second-largest hosting company in the world by web-facing computers—behind only AWS. Amazon still had far broader global coverage, but the very fact that DigitalOcean was in the same sentence told you how fast this thing was moving. DigitalOcean said more than a half-million developers had deployed over six million cloud servers—Droplets—on the platform.

Take that in. A company founded just a few years earlier—bootstrapped out of New York, literally walking around with pizza to interview CTOs—had become, by certain measures, one of the biggest hosting platforms on the internet. Not by outspending the hyperscalers. By out-loving them, in the one segment where love actually matters.

Through all the growth, the product philosophy stayed stubbornly consistent: simple, but not simplistic. Every new capability had to earn its way in. Would it make developers’ lives easier, or just add another knob to turn? That discipline helped DigitalOcean scale without losing its identity.

It also planted the seed of the next tension in the story: what happens when your customers start asking for “just one more thing,” and every “one more thing” pulls you closer to the complexity you set out to escape?

VI. Inflection Point #1: The Enterprise Temptation (2015–2017)

Success has a way of narrowing your options. By 2015, DigitalOcean had done the hard part: it had built something developers genuinely loved, and it could acquire them efficiently. The catch was in the unit economics of that love. Most of those customers were spending something like $5 to $50 a month. That’s great for adoption. It’s harder if your ambition is to build a truly massive company.

So DigitalOcean found itself staring at a fork in the road: keep serving developers, startups, and SMBs—or start chasing the enterprise budgets that AWS, Azure, and Google were vacuuming up.

This is a familiar arc in tech. A product wins the hearts of developers. It spreads bottoms-up. Then the company looks upmarket, because enterprise buyers write bigger checks, sign longer contracts, and are harder to dislodge once you’re embedded. But “going enterprise” isn’t just a pricing change. It’s a full-body transformation: sales teams, customer success, compliance, procurement cycles, certifications, and roadmaps increasingly shaped by what the biggest accounts need—often at the expense of the simplicity that made the product beloved in the first place.

That tension started showing up in the product. During this period, DigitalOcean expanded beyond basic Droplets and added capabilities like block storage, load balancers, and managed databases. These were the kinds of building blocks growing businesses expected, and they made the platform more complete. They also made it more complicated. Each new feature forced the same question: does this make developers’ lives easier—or does it turn DigitalOcean into the kind of console developers came here to avoid?

At the same time, the competitive landscape got a lot less forgiving. DigitalOcean had helped make the modern VPS feel fun and approachable—a simpler, cleaner alternative to AWS. And then, inevitably, AWS came for the exact thing DigitalOcean had made popular.

In 2016, Amazon launched Lightsail, a simplified VPS product with pricing that started at $5. Developers immediately read it for what it was: AWS, intentionally trying to look more like DigitalOcean.

Lightsail was flattery in the form of a threat. It meant Amazon had noticed that a comparatively tiny company was winning mindshare with the very people who would become the next generation of cloud decision-makers. But it also raised the stakes. If the world’s largest cloud provider was now offering “simple,” could DigitalOcean keep its edge on simplicity? Or would simplicity get commoditized the way servers had?

The pressure wasn’t only external. Internally, DigitalOcean was also growing up fast. “I’d like to thank our talented and growing team of 1,200 employees around the world for their passion for and commitment to DigitalOcean’s mission to simplify cloud computing.” Getting from five founders to a global organization of that size doesn’t happen without trade-offs. The scrappy, instinctive operating style that works in the early days gives way to layers: process, specialization, managers, planning cycles—the stuff you need to scale, and the stuff that can quietly slow you down.

Leadership was shifting too. Ben Uretsky had driven the vision, strategy, and growth from 2012 through 2018. Stepping aside after taking a company from zero to real industry prominence takes a certain kind of self-awareness. He stayed on the board, but day-to-day control moved to professional management. In June 2018, Mark Templeton, the former CEO of Citrix, took over as CEO—bringing instant enterprise credibility from a career built selling to IT departments worldwide.

Even if DigitalOcean wasn’t declaring an enterprise pivot outright, the signal was hard to miss: the company was entering a new chapter. And the central question of that chapter was the one hanging over every decision—product, leadership, hiring, go-to-market:

Could DigitalOcean add the capabilities customers were asking for, fend off AWS moving downmarket, and still feel like DigitalOcean?

VII. Inflection Point #2: The Yancey Spruill Era & Repositioning (2018–2020)

By the time Mark Templeton came in, the company had already started to “grow up.” But the next shift was even more defining: DigitalOcean needed a leader who could scale the business without turning it into the kind of enterprise machine it was built to counter-program.

In July 2019, Yancey Spruill—formerly the CFO and COO of SendGrid, another Techstars alum—replaced Templeton as CEO. Around the same time, Bill Sorenson, the former CFO of EnerNOC, was appointed CFO.

Spruill’s profile was a clean break from both the founders and his predecessor. He was deeply familiar with high-growth tech, but he wasn’t coming in as a founder-operator or an enterprise titan. He’d spent four years at SendGrid, helping take it from a much smaller revenue base to more than triple that size. And he’d done it in a world adjacent to DigitalOcean’s: cloud infrastructure, developer-centric products, and the reality that “simple” is hard to scale.

“As my previous role, I gained a substantial understanding of cloud infrastructure,” Spruill said. “So my experience aligned well with DigitalOcean by the time I was coming on board in 2019.” DigitalOcean wanted to grow, and Spruill’s track record at SendGrid was a compelling proof point.

His personal story also fit DigitalOcean’s ethos: ambitious, practical, and a little bit contrarian. Spruill grew up in Buffalo in the 1970s, during the years when America’s industrial belt was hollowing out. Layoffs and labor strife were everywhere, and nothing about that environment screamed “future business executive.” His main goal was simply to leave Buffalo—and he did it by leaning on a straightforward belief system. “I know people don’t believe it anymore but there is this thing called the American Dream,” he said, “that if you work hard, keep your nose clean, and study hard, good things will happen.” He went on to study engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta.

Once he took the job, Spruill made what was arguably the most important strategic call of his tenure: he explicitly committed DigitalOcean to the SMB market.

Instead of chasing enterprise customers—with their long procurement cycles, compliance checklists, and roadmaps dictated by big accounts—DigitalOcean doubled down on what had always made it different: serving developers, startups, and small businesses. The message, internally and externally, was crisp. DigitalOcean was not going to try to be AWS.

That focus clarified how the company wanted to win. The hyperscalers would keep competing on breadth: more services, more regions, more specialized infrastructure. DigitalOcean would compete on experience. In a world where silicon and network capacity are increasingly commoditized, DigitalOcean’s differentiation was its simplified developer experience—helping customers write code faster, deploy more easily, and scale without needing a dedicated ops team. That’s what kept product-market fit strong with entrepreneurs and small teams who wanted to build software, not babysit infrastructure.

And importantly, “staying focused” didn’t mean standing still. Product evolution accelerated in this period. In May 2018, DigitalOcean announced the launch of a Kubernetes-based container service. Kubernetes—the container orchestration system that emerged from Google—was rapidly becoming the default way modern applications got deployed. But running Kubernetes well is notoriously complex. DigitalOcean’s pitch was classic DigitalOcean: you can get the power of Kubernetes without having to become a Kubernetes expert.

Then 2020 hit, and the world changed.

COVID-19 became an unexpected tailwind. Overnight, every business needed a digital presence. Small companies that had been inching toward digital transformation were forced to sprint. E-commerce surged. Remote work became the norm. Demand for digital services spiked. And across the board, that meant more demand for cloud infrastructure—especially for the kinds of customers DigitalOcean served.

In May 2020, DigitalOcean raised an additional $50 million from Access Industries and Andreessen Horowitz. The company was positioning itself for the next major transition: going public.

As one board member later put it, the IPO path wasn’t a single decision so much as a series of operational switches that had to get flipped. When Spruill joined, the view was basically: there are “20 levers” to pull to get ready for an IPO. The only problem was, no one could neatly list what those levers were. Spruill and his team figured it out the only way DigitalOcean ever had—by executing, while staying true to the company’s core focus: serving the developer community.

VIII. Going Public: IPO & Public Market Reality (2021)

In March 2021, DigitalOcean stepped onto the biggest stage in business: the public markets.

The company priced its initial public offering at $47 per share, selling 16.5 million shares. On March 24, 2021, DigitalOcean began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker DOCN, at an implied valuation of about $5 billion. That morning, Yancey Spruill rang the opening bell—an on-the-nose moment for a company built on the idea that infrastructure should feel simple, not intimidating.

It was also a surreal milestone in context. The Brighton Beach brothers who had once walked around New York with pizza, trading slices for honest product feedback, had taken their developer-first cloud all the way to the NYSE. Early backers did incredibly well on paper. IA Ventures, which led DigitalOcean’s seed round, had paid about $0.26 per share in the 2012–2013 timeframe, according to Crunchbase—meaning the IPO price implied roughly 180x returns.

But the first day of trading delivered a quick reminder: Wall Street doesn’t grade on origin stories.

DOCN opened around $41.50—about 12% below the IPO price—and finished the day down close to 10% at $42.50, valuing the company at roughly $4.5 billion. In private markets, a company like DigitalOcean could be understood as a long-term compounding machine: a beloved product, a huge base of small customers, and a clean path to expanding over time. In public markets, it also had to hit near-term expectations, quarter after quarter, in full view of everyone.

The S-1 made the trade-offs plain. In 2020, DigitalOcean posted a $43.6 million net loss on $318.4 million of revenue, with revenue up about 25% year over year and losses up 7% from 2019. CFO Bill Sorenson told prospective investors the plan was to earn more from each customer while bringing research and development and general and administrative spending down as a percentage of revenue. “We still see a pathway to continuing to increase our overall operating margins in a number of the spend areas,” Sorenson said.

Underneath that corporate language was the real strategic tension: DigitalOcean had hundreds of thousands of customers, but the average customer didn’t spend much. To turn a developer-loved cloud into a public-market-loved company, it would need to increase average revenue per customer, find meaningful operating leverage at scale, or pull off both at once.

Then the macro environment flipped. The tech sell-off of 2022 punished growth stocks broadly, and DigitalOcean got swept up in it. DOCN fell more than 45% from its IPO price as rising interest rates and inflation concerns sparked a rotation away from high-growth tech.

From IPO to later trading, the company’s market cap moved from about $4.95 billion to about $4.63 billion—a decline of roughly 6%. For DigitalOcean, the early public-company era became a different kind of operating challenge: not just running the business well, but doing it with a stock chart that could swing on sentiment, not just execution.

That’s the public market reality. DigitalOcean could keep building what it had always built—simple, reliable infrastructure for the people who just want to ship—but now it had a second product too: investor expectations.

IX. The Modern Era: AI, Competition & Finding Moats (2022–2024)

ChatGPT’s breakout in late 2022 didn’t just add another tech trend. It rewired the roadmap for basically every software company overnight. Suddenly, “we should have an AI story” became table stakes, and the scarce resource wasn’t ideas—it was GPUs, the specialized chips that make modern AI workloads possible.

For DigitalOcean, that was both a tailwind and a gut check. The opportunity was obvious: their core customers—developers, startups, SMBs—were going to want to build with AI the same way they’d wanted to build with web servers a decade earlier. The threat was just as obvious: if AI became the next big wave of cloud demand, and DigitalOcean didn’t have credible GPU infrastructure, it risked getting squeezed into “the place you host the old stuff.”

So DigitalOcean made a very un-DigitalOcean move, in the best way: it bought its way into relevance.

In July 2023, DigitalOcean acquired Paperspace for $111 million in cash. Management said the deal would have an immaterial impact on 2023 financial results, but strategically it was a loud signal: DigitalOcean was serious about AI infrastructure.

Paperspace had been founded in 2014 by Daniel Kobran and Dillon Erb, University of Michigan grads, and had raised $35 million from investors including Battery Ventures, Intel Capital, SineWave Ventures, and Sorenson Capital. It was also backed by Y Combinator—and notably by Jeff Carr, one of DigitalOcean’s own co-founders. The company ran its own data centers with custom GPU configurations, and while it started with low-cost virtual machines and high-performance cloud workstations for design, visualization, and gaming, it increasingly leaned into AI. As AI went mainstream, Paperspace built tools for developing, training, deploying, and hosting models in the cloud—exactly the muscle DigitalOcean needed.

This wasn’t DigitalOcean’s first acquisition as a public company, either. In 2022, it bought Cloudways for $350 million in cash, with a significant portion of the consideration paid over the 30 months following closing. Cloudways put DigitalOcean deeper into managed hosting—an on-ramp for SMBs who want the power of cloud infrastructure without having to run it themselves. The fit was unusually clean: the two companies had worked together since 2014, and Cloudways relied on DigitalOcean infrastructure for approximately 50% of its customers. Cloudways also came with an industry-leading NPS of 71. Combined, DigitalOcean and Cloudways would serve more than 124,000 customers paying over $50 per month, representing about 84% of the pro forma company’s total revenue.

By 2024, DigitalOcean fully folded the Paperspace brand into DigitalOcean. In other words: Paperspace stopped being a separate product you had to go discover. DigitalOcean became the umbrella brand for its AI/ML offerings—GPUs and GenAI capabilities included.

All of this was happening while competitive pressure kept rising from every direction.

The hyperscalers—AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud—kept improving their developer experiences and shipping AI features at hyperscaler speed. Meanwhile, companies like Vercel and Netlify fought for control of the deployment layer. Cloudflare bundled more infrastructure into its edge network. And price-first providers like Hetzner kept dragging the market toward commoditization.

Which brought DigitalOcean back to the same core question it’s faced since the beginning: when the underlying compute is increasingly interchangeable, what’s the moat?

DigitalOcean’s answer in this era centered on three ideas: keep the product experience simple, make AI accessible to SMBs, and run the business with real operational discipline.

That strategy became tangible on October 1, 2024, when DigitalOcean announced that GPU Droplets accelerated by NVIDIA H100 Tensor Core GPUs were available to all customers. Customers could spin up NVIDIA H100 instances in 1- and 8-GPU configurations directly through the control panel and API.

X. Recent Developments & Current State (2024–Present)

By late 2024, DigitalOcean wasn’t just shipping new products. It was changing who would lead the next chapter.

Paddy Srinivasan joined DigitalOcean from GoTo, a SaaS company with more than $1 billion in revenue, where he served as CEO. His background reads like a checklist for the job DigitalOcean needed done: build products customers actually like using, then scale them without losing the plot. Over a 25+ year career, he’s moved between startups and giants—co-founding Opstera, holding senior product and engineering roles at Oracle and Microsoft, and running major product and technology organizations at GoTo (formerly LogMeIn). Before that, he was at Amazon as General Manager for Data and Machine Learning Platform Services and Alexa AI.

That leadership transition landed against a backdrop of a business that, for the first time in a while, started to look more like a disciplined compounder than a niche challenger.

In Q4 2024, DigitalOcean reported $205 million in revenue, up 13% year over year. For the full year, revenue reached $781 million, also up 13%. Profitability moved sharply in the right direction: net income for 2024 was $84 million, and adjusted EBITDA was $328 million. In the company’s words, DigitalOcean Holdings, Inc. (NYSE: DOCN) was leaning into its identity as “the simplest scalable cloud for growing tech companies”—but now with public-company margins to match.

At the end of the quarter, annual run-rate revenue (ARR) was $820 million, up 13% year over year. Gross profit was $126 million, up 22%, with gross margin at 62%. Net income attributable to common stockholders came in at $18 million, up 15%, and adjusted EBITDA was $86 million, up 17%.

Then, in Q3 2025, management signaled that the story wasn’t just “we’re profitable now.” It was “we’re accelerating.”

“DigitalOcean's unified agentic cloud is driving accelerated momentum in Q3. Revenue increased 16% year over year and we delivered the strongest incremental organic ARR in our history,” Srinivasan said. He also pointed to traction with larger customers: revenue from customers with more than $100,000 in annual run-rate grew 41% year over year and represented 26% of total revenue.

The quarter’s headline numbers reflected that momentum. Q3 revenue reached $230 million, up 16% year over year—its highest growth rate since Q3 2023. The company posted $44 million in organic incremental ARR, the highest in its history, and delivered $100 million in adjusted EBITDA, up 15% year over year. DigitalOcean said Direct AI revenue more than doubled year over year for the fifth consecutive quarter, while general-purpose cloud products delivered their strongest incremental organic ARR since Q2 2022.

Looking ahead, the company’s Q4 and full-year 2025 guidance implied a 16% exit growth rate for 2025. And while it said it wouldn’t provide 2026 guidance until its February earnings call, it expected to deliver 18% to 20% growth in 2026.

By this point, DigitalOcean said more than 640,000 customers relied on it for cloud, AI, and ML infrastructure. For 2025, it projected total revenue between $870 million and $890 million. It also expected its AI/ML business to grow from $29 million in 2024 to $105 million in 2026, with long-term goals of reaching 18% to 20% revenue growth and mid-teens adjusted free cash flow by 2027.

Under the hood, this is still an infrastructure business—meaning execution lives and dies by physical reality. DigitalOcean operates 15 in-house data centers connected by a private network, and it has been building out a new data center in Atlanta, Georgia, scheduled to launch in Q1 2025.

XI. Business Model Deep Dive & Unit Economics

DigitalOcean’s business model looks almost too simple from the outside: developers swipe a card, spin up infrastructure, and pay for what they use. But that surface simplicity hides a deliberately engineered economic machine—one built to stay profitable in a category dominated by companies that can outspend anyone.

It starts with the pricing philosophy: clarity as a feature. Where AWS pricing can feel like a choose-your-own-adventure written in spreadsheets, DigitalOcean’s pricing is designed to be understood at a glance. A Basic Droplet starts at $4 per month. Managed Kubernetes is priced per node. Storage is a straightforward per‑gigabyte fee. That’s not just friendlier marketing. When customers can predict their bill, they deploy faster, panic less, and file fewer support tickets. The product feels safer to adopt.

From there, revenue follows the way modern infrastructure gets consumed: metered usage across compute (Droplets), managed databases, storage (Spaces), and networking—plus, increasingly, GPU infrastructure for AI workloads. On top of that core, DigitalOcean also brings in revenue from Cloudways’ managed hosting services and from the AI/ML capabilities that came with Paperspace.

The customer base tells you what the company is optimizing for. DigitalOcean segments users by spend, with particular focus on its “Builders and Scalers”—customers spending more than $50 per month—because that’s where the business gets durable. And at the high end of its market, it’s starting to show real momentum: revenue from customers spending more than $100,000 annually grew 41% year over year.

That “move up” shows up in ARPU too. Average revenue per customer rose to $95.13, up 8% versus the first quarter of 2023, and later reached $102.51, up 11% versus the third quarter of 2023. Builders and Scalers increased 8% versus the first quarter of 2023, and their revenue grew 13% year over year.

The dynamic here is the whole strategic trade-off in one metric. DigitalOcean has proven it can raise ARPU over time through product expansion and land-and-expand behavior. But the levels are still modest compared to enterprise clouds—because this is what you sign up for when you choose SMBs over Fortune 500 procurement departments.

On margins, DigitalOcean looks like what it is: an infrastructure company that’s run with discipline. Gross margins have stabilized around 60–62%, including 61% gross margins alongside 41% EBITDA margins. Those are strong for IaaS, but they’ll never look like pure software margins, because the underlying inputs are physical: servers, storage, bandwidth, and data center capacity.

The go-to-market engine is classic DigitalOcean: product-led and content-led. Instead of field sales teams chasing large accounts, the company pulls customers in through tutorials, documentation, organic search, word-of-mouth, and community. That model typically means much lower customer acquisition costs than enterprise-first competitors, and it fits the way developers actually choose infrastructure.

Retention is solid, if not explosive. Net Dollar Retention was 97% versus 96% the prior quarter, then increased to 99% from 97% in the third quarter of 2024. Near 100% is a sign of a stable base: customers aren’t dramatically expanding, but they aren’t falling off a cliff either. It’s not the 120%+ you’ll see in best-in-class enterprise SaaS, but it matches DigitalOcean’s segment and positioning.

Profitability, in turn, has come from operational leverage—getting more efficient as the business scales. Adjusted EBITDA was $86 million, up 17% year over year, with a 42% adjusted EBITDA margin.

And finally, the constraint you can’t hand-wave away: capital intensity. DigitalOcean can’t scale purely by writing more code. It has to keep buying hardware, expanding capacity, and investing in its network. Capex was 30% of revenue for the quarter. That’s the price of doing business in cloud infrastructure—and why “simple” on the front end still requires serious machinery on the back end.

XII. Strategic Frameworks: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate-High

In raw technical terms, the cloud is more buildable than ever. Open-source virtualization, containers, and a mature ecosystem of cloud-native tools have lowered the barrier to standing up something that looks like “a cloud.” With enough capital, a new entrant can get pretty far, pretty fast.

But “standing it up” isn’t the same as winning customers. DigitalOcean’s real defenses here are softer and harder to copy: a decade-plus of brand trust with developers, a distribution engine built on community and content, and a reputation for making infrastructure feel approachable. Those don’t stop entrants, but they do raise the cost of becoming relevant.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate

DigitalOcean is downstream of very real supply chains: CPUs and servers, storage, networking gear, and the data center footprint to run it all. In normal times, there are enough alternatives across most of those categories that no single vendor fully dictates terms.

AI changes that balance. When the market is short on high-end GPUs, supplier leverage goes up, fast. DigitalOcean’s CFO noted they had Nvidia H200s coming and that they were watching Blackwell’s timing. The subtext is clear: in the AI era, hardware availability and pricing aren’t just cost items—they’re strategic constraints.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High

Developers have options. Lots of them. Between transparent pricing, copy-pasteable infrastructure tooling, and a culture of “try it and move on,” buyers can shop around and switch when something better comes along.

DigitalOcean still benefits from a few forms of inertia: migration work, downtime risk, reconfiguring systems, retraining muscle memory. Most teams don’t wake up excited to move clouds. But the broader reality is that buyer power stays high, because the switching costs are real yet rarely prohibitive.

Threat of Substitutes: Very High

DigitalOcean doesn’t just compete with other VPS providers. It competes with the idea that you shouldn’t have to think about servers at all.

At the infrastructure layer, the hyperscalers are always there. Above that, platforms like Vercel, Netlify, and Render offer a path where developers ship without ever touching the underlying plumbing. Cloudflare pushes a different model entirely, pulling compute toward the edge. And for larger, more regulated customers, on-prem and hybrid architectures remain viable alternatives.

If you’re asking “what force matters most?” it might be this one. DigitalOcean is fighting not only rivals, but shifting abstractions.

Competitive Rivalry: Extreme

This is the hard truth of the category: DigitalOcean competes in a market where the biggest players can outspend, out-price, and out-ship nearly anyone, whenever they decide it matters. AWS alone brings in more revenue in a single quarter than DigitalOcean’s entire market cap. If a hyperscaler wants to compress margins in a segment for strategic reasons, it can.

Then there are the specialists: lean providers attacking on price, performance, location, or niche workflows. Rivalry isn’t occasional—it’s constant, and it shows up in both pricing and product expectations.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Limited

DigitalOcean does get some scale benefits: buying hardware in larger batches, improving utilization, spreading fixed costs across a bigger revenue base. Those are meaningful in infrastructure.

But compared to the hyperscalers, it’s a different game. Amazon, Microsoft, and Google operate at a level of scale that caps how much advantage DigitalOcean can ever extract purely from getting bigger.

Network Effects: Weak-to-Moderate

DigitalOcean’s community and tutorial ecosystem has a compounding quality: more content brings in more developers, which creates more demand and feedback, which supports more content. That’s real, and it’s been one of the company’s smartest long-term bets.

But it’s not a classic network effect where each new user directly increases the value of the product for every existing user. It’s closer to a durable, feedback-driven distribution loop than a marketplace-style lock-in.

Counter-Positioning: Strong (Historically), Eroding

This was the original superpower: DigitalOcean was the anti-AWS experience. Where the hyperscalers were broad and complex, DigitalOcean was clean, focused, and friendly. “Simple” wasn’t a marketing line—it was the strategy.

The problem with counter-positioning is that it works best when incumbents can’t follow without breaking their own model. Over time, AWS has improved its UX and launched simplified offerings. The gap hasn’t disappeared, but it’s narrowed. What once felt like a radical alternative can start to look like a difference of degree.

Switching Costs: Moderate

Moving infrastructure is annoying. There are configurations to rewrite, data to move, networking to re-plumb, and failure modes nobody wants to discover in production. Those frictions create stickiness.

But this isn’t enterprise software where migrations take a year and require executive sponsorship. A motivated customer can move in days or weeks. Switching costs help DigitalOcean, but they don’t protect it.

Branding: Moderate-Strong

DigitalOcean’s brand is genuinely loved in its core segment. “The developer cloud” means something because the company earned it—through a product that feels welcoming and through years of community education that made it a trusted resource, not just a vendor.

That brand power weakens as you move upmarket. Enterprises don’t buy “friendly.” They buy certifications, procurement alignment, and vendor assurance. DigitalOcean can win larger customers, but it doesn’t enjoy hyperscaler-level brand gravity in that world.

Cornered Resource: Weak

There’s no patented magic here—no exclusive data asset, no unique research advantage, no proprietary technology that others can’t build around. The community is valuable, but it’s not uncopyable. And talent, in tech, always has a market.

Process Power: Moderate

DigitalOcean has built strong operating processes for its audience: streamlined onboarding, self-serve workflows, community-driven support, and a product approach that prioritizes reducing cognitive load. That’s a kind of operational advantage.

Still, it’s not a moat on its own. Competitors can replicate good processes if they’re willing to invest—and many are.

Synthesis

DigitalOcean’s advantage is real, but it’s not the kind you can put behind a castle wall. It rests mostly on brand and the remnants of its original counter-positioning, with some help from switching friction and well-tuned SMB-focused operations.

In a market this competitive, a narrow moat can still be enough—but only if it’s reinforced every day. For DigitalOcean, that means relentless execution: staying simpler than the giants, staying more reliable than the cheap players, and staying relevant as the industry keeps abstracting the infrastructure away.

XIII. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Thesis

The Bull Case

The optimistic view starts with a simple idea: DigitalOcean may still be early in its market. The world keeps minting new businesses, and most of them are exactly the kind of teams DigitalOcean was built for—small, speed-focused, and allergic to unnecessary complexity. As Yancey Spruill put it: “The cloud market is one massive opportunity… there are 14 million new companies created every year.” If even a small slice of those companies eventually need real infrastructure, the top of the funnel is effectively endless.

AI adds a second tailwind: an actual category expansion, not just a new feature. DigitalOcean said its AI revenue more than doubled year over year for the fifth consecutive quarter, which matters less for the absolute dollars today and more for what it signals—SMBs want AI capabilities, and they don’t all want to buy them from AWS. If DigitalOcean can become the “easy button” for SMB AI infrastructure the way it became the easy button for web infrastructure, growth could re-accelerate.

Then there’s the margin story. DigitalOcean has already shown it can run this business with discipline, and management has been explicit that operating leverage is part of the plan. Infrastructure will always be capital intensive, but scale still helps: better utilization, more efficient operations, and a bigger base to spread fixed costs across.

And the wild card is the thing DigitalOcean has always had in spades: developer loyalty. The company’s entire model is land-and-expand. A customer might start at $5 a month, then gradually grow into spending hundreds or thousands as their app becomes a business. That curve isn’t instant, and ARPU growth tends to be gradual rather than explosive, but it’s real—and it compounds.

Finally, the bull case has a built-in escape hatch: acquisition value. DigitalOcean’s customer base, brand, and infrastructure could be strategically attractive to a buyer like Oracle, IBM, Broadcom, or private equity—anyone who wants developer-focused cloud assets without having to build them from scratch. That doesn’t guarantee a deal. But it does create a plausible floor under the “this company disappears” narrative.

The Bear Case

The bear case is blunt: hyperscalers can choose to make DigitalOcean’s life miserable whenever they want.

AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud have effectively unlimited capital and every strategic incentive to win the next generation of cloud customers early. If they decide to aggressively target SMBs with simplified products and pricing pressure, DigitalOcean can’t fight that battle with brute force. It has to win on focus and experience—and those advantages can narrow over time.

Which leads to the second concern: differentiation. DigitalOcean’s original counter-positioning was crystal clear: “we’re the simple alternative.” But as AWS improves its developer experience and ships offerings like Lightsail, the obvious question becomes harder to dodge: what is the unique value that keeps DigitalOcean essential as an independent company?

Then there’s the growth ceiling problem. DigitalOcean has historically avoided the enterprise motion—big contracts, long commitments, procurement cycles—because that’s not who it was built for. But without landing six-figure enterprise deals at scale, the path to meaningfully larger revenue gets narrower. The fear isn’t that DigitalOcean can’t grow. It’s that it can’t grow fast enough, for long enough, to satisfy the expectations that come with a public-company valuation.

AI intensifies that tension. The infrastructure required to compete seriously in AI—especially access to GPUs and the capital to deploy them at scale—favors the hyperscalers. Even if DigitalOcean’s AI business is growing quickly, it’s still tiny relative to what Amazon, Microsoft, and Google can offer, and the GPU shortage gives suppliers and incumbents the upper hand.

And the pressure doesn’t only come from above. It also comes from below. Price-first providers like Hetzner and OVH keep dragging the market toward commoditization, and DigitalOcean can’t win a race to the bottom without breaking its own economics.

The Realistic Case

The middle path is that DigitalOcean keeps doing what it has proven it can do: run a profitable, durable cloud business for developers and SMBs. In that world, steady organic growth—something like 10–15%—is achievable without heroic assumptions, and continued operational discipline could plausibly push operating margins higher over time.

The company likely remains independent, or it gets acquired at a modest premium. The road to becoming AWS is closed. But DigitalOcean doesn’t need to become AWS to be a good business—it just needs to keep owning its lane, even as the giants keep trying to repaint it.

XIV. Playbook: Lessons for Founders & Investors

Simplicity as Strategy

DigitalOcean’s big insight was that simplicity isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s a competitive strategy. In markets where every incumbent keeps adding more switches, more SKUs, and more “advanced settings,” there’s usually a huge group of customers who want the opposite: fewer decisions, fewer ways to shoot yourself in the foot, and a path from idea to running app that doesn’t require a weekend of studying.

The founders designed for the reality of their customer. If you’re a developer paying $5 a month, you don’t have the time or patience for complexity theater. By optimizing for constraints instead of maximal capability, DigitalOcean turned “less” into real differentiation.

Developer-First Go-to-Market

DigitalOcean also showed how far you can get by meeting developers where they already are—and speaking like a developer, not like a brochure. The tutorials and community engagement weren’t window dressing; they were the acquisition engine. Thousands of practical guides helped customers succeed, pulled in organic traffic, and built trust in a way paid marketing rarely can.

That playbook comes with requirements: patience (content takes time to compound) and authenticity (developers can smell corporate marketing instantly). But when it works, it becomes a durable, low-cost growth machine that doesn’t depend on outspending competitors.

Niche Focus vs. Feature Sprawl

Every company that wins a niche eventually gets the same question from investors, employees, and customers: when are you going “upmarket”? Bigger customers mean bigger budgets, higher ARPU, and longer contracts. And that is genuinely tempting.

DigitalOcean lived the upside and the downside of that pressure. The upside is obvious. The risk is subtle and deadly: you start building for procurement checklists and edge cases, and the product that used to feel clean starts to feel like everything else. Spruill’s recommitment to SMBs was a clear strategic choice. It traded some near-term expansion for coherence, focus, and a better chance of staying DigitalOcean.

Competing with Giants

If you’re competing with AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud, you can’t play their game. You’re not going to win on total feature breadth, and you’re not going to win a sustained price war against companies that can subsidize segments for strategic reasons.

So you need a lane the giants can’t or won’t fully occupy. For DigitalOcean, that lane has been an opinionated experience: simplicity, community, and a product built for people who want to ship, not manage infrastructure. The broader lesson is as old as strategy itself: pick your battles, then build until you’re unmistakably the best choice in that specific fight.

Bottoms-Up Infrastructure

DigitalOcean also helped normalize a bottoms-up growth motion for infrastructure: transparent pricing, self-serve onboarding, usage-based billing, and a product that developers can adopt without asking permission. That minimized the need for heavy sales motion while maximizing reach.

It’s the same dynamic that powered great developer tools: win the individual first, then let the usage grow into the business.

Building Moats in Commodity Markets

Finally, DigitalOcean is a reminder that infrastructure is brutally commoditized. Hardware is broadly available. Protocols are standard. Competitors can match features, and incumbents can copy UX patterns.

In that world, the durable advantages tend to be intangible: brand, distribution, and customer relationships. DigitalOcean’s moat—such as it is—doesn’t live in proprietary technology. It lives in trust, reputation, and the compounding value of being the cloud that developers remember as the one that just worked.

XV. Epilogue & Future Scenarios

Scenario 1: Independence, Steady-State Profitable Growth

DigitalOcean keeps doing what it’s doing now: serving developers and SMBs, growing steadily in that 10–15% range, and widening margins through operational discipline. In this world, it settles into the role of a durable, mid-cap infrastructure business. The stock doesn’t need a hype cycle to work; it works the boring way—through profit growth, and potentially a higher multiple as the market gains confidence that the business can keep compounding.

Scenario 2: Acquisition by Strategic Buyer

A strategic buyer—Oracle, IBM, Broadcom, or someone with similar motivations—decides it’s faster to buy developer distribution than to build it. DigitalOcean’s appeal here isn’t some secret technology. It’s the combination of customer base, brand trust, and a real platform with proven operations. The premium is meaningful but not euphoric—something like 30–50%—reflecting a mature public company in a brutally competitive category. The trigger could be simple: prolonged stock underperformance, or a buyer deciding that cloud and AI ambitions need a developer-first on-ramp, now.

Scenario 3: AI Pivot Changes Trajectory

The Paperspace/GPU bet hits harder than expected. DigitalOcean becomes a default choice for AI-native startups that want capability without hyperscaler complexity, and GPU revenue grows into a business that actually moves the needle. If that happens, growth could reaccelerate into the 25%+ range, and the narrative shifts from “steady infrastructure company” back to “platform with a second act.” This path requires execution—and, just as importantly, the right timing and positioning in a market where the incumbents control the supply chain.

Scenario 4: Private Equity Take-Private

If public markets stay impatient, private equity starts to look like the natural endgame. A PE firm values the predictable customer base, recurring revenue, and clear levers for margin expansion. DigitalOcean goes private at a premium to where it’s trading, but likely below prior highs, then gets run for efficiency—cost controls, pricing tweaks, utilization improvements—before either returning to the public markets later or selling to a strategic buyer.

Key KPIs to Track

Net Dollar Retention (NDR): If you only watched one metric, it would be this. NDR tells you whether the existing customer base is expanding, flat, or shrinking. Above 100% means the base is growing even before you add new customers. DigitalOcean’s move up to 99% is a positive signal—but it’s still not the “customers are expanding effortlessly” profile you see in the best enterprise SaaS businesses.

High-Value Customer Growth: The big strategic question is whether DigitalOcean can move upmarket without losing the product identity that made it work in the first place. Growth from customers spending $100K+ annually is one of the cleanest signals here. The recent 41% growth rate in that segment is one of the most encouraging data points in the entire story.

AI/ML Revenue: If DigitalOcean wants a true second growth curve, AI has to become more than a press release. Watching GPU and Paperspace-related revenue is the simplest way to see whether the strategy is gaining real traction, or staying stuck as an interesting but small side business.

The Broader Lesson

DigitalOcean’s story is a reminder of something easy to miss in markets dominated by giants: there’s often room for focused players, if they serve a real segment that the giants underserve by default. The hard part is never spotting the opening—it’s keeping it defensible once the category matures and the incumbents adapt.

More than a decade after founding, DigitalOcean has already answered one question: yes, this can be a real business. It’s profitable, it’s still growing, and it’s still solving a genuine customer problem.

The open question is the one that matters now: can it keep thriving as an independent company, with hyperscalers moving downmarket, new abstractions pulling developers away from servers, and AI reshaping the infrastructure stack in real time?

What’s not in doubt is the original insight. Developers did need a simpler cloud. The gap was real. And DigitalOcean proved that even in one of the most competitive arenas on Earth, a company can carve out a meaningful place by making the product feel like a tool—one that helps people ship.

XVI. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Resources

- DigitalOcean S-1 Filing (2021) - SEC.gov - The best starting point: how DigitalOcean explains its business model, key risks, and financials in its own words

- DigitalOcean Investor Relations - investors.digitalocean.com - Earnings calls, shareholder materials, and the quarter-by-quarter story of how the company is operating today

- "Building a Cloud That Developers Love" - a16z archive - The original investment thesis and why developer love was treated as a real strategic asset

- Annual Shareholder Letters (2021-2024) - Management’s view of what matters, what’s changing, and what they’re optimizing for

- Netcraft Hosting Research - Independent data that helps triangulate DigitalOcean’s footprint in the hosting ecosystem

- The New Kingmakers by Stephen O'Grady (RedMonk) - Great context for why developers became the buyer, the influencer, and the distribution channel all at once

- Cloud Infrastructure Market Reports (Gartner, Forrester) - Broader market framing and where DigitalOcean fits versus hyperscalers and specialists

- TechCrunch Archive: DigitalOcean Coverage - A time capsule of key launches, funding rounds, and inflection points as they happened

- DigitalOcean Community Tutorials Archive - The clearest window into the content flywheel that helped turn the brand into a trusted resource

- HackerNews Threads on DigitalOcean - Unfiltered developer sentiment—the praise, the complaints, and the moments the product really broke through

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music