Ducommun Inc: From Civil War Supplier to Aerospace Precision

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s 1849, and a young Swiss immigrant steps onto the docks of San Francisco Bay. California is in full Gold Rush frenzy. Thousands of people are clawing through riverbeds, chasing the same glittering dream.

Charles Louis Ducommun takes one look at the chaos and makes a different bet. He doesn’t pick up a pickaxe. He opens a hardware store.

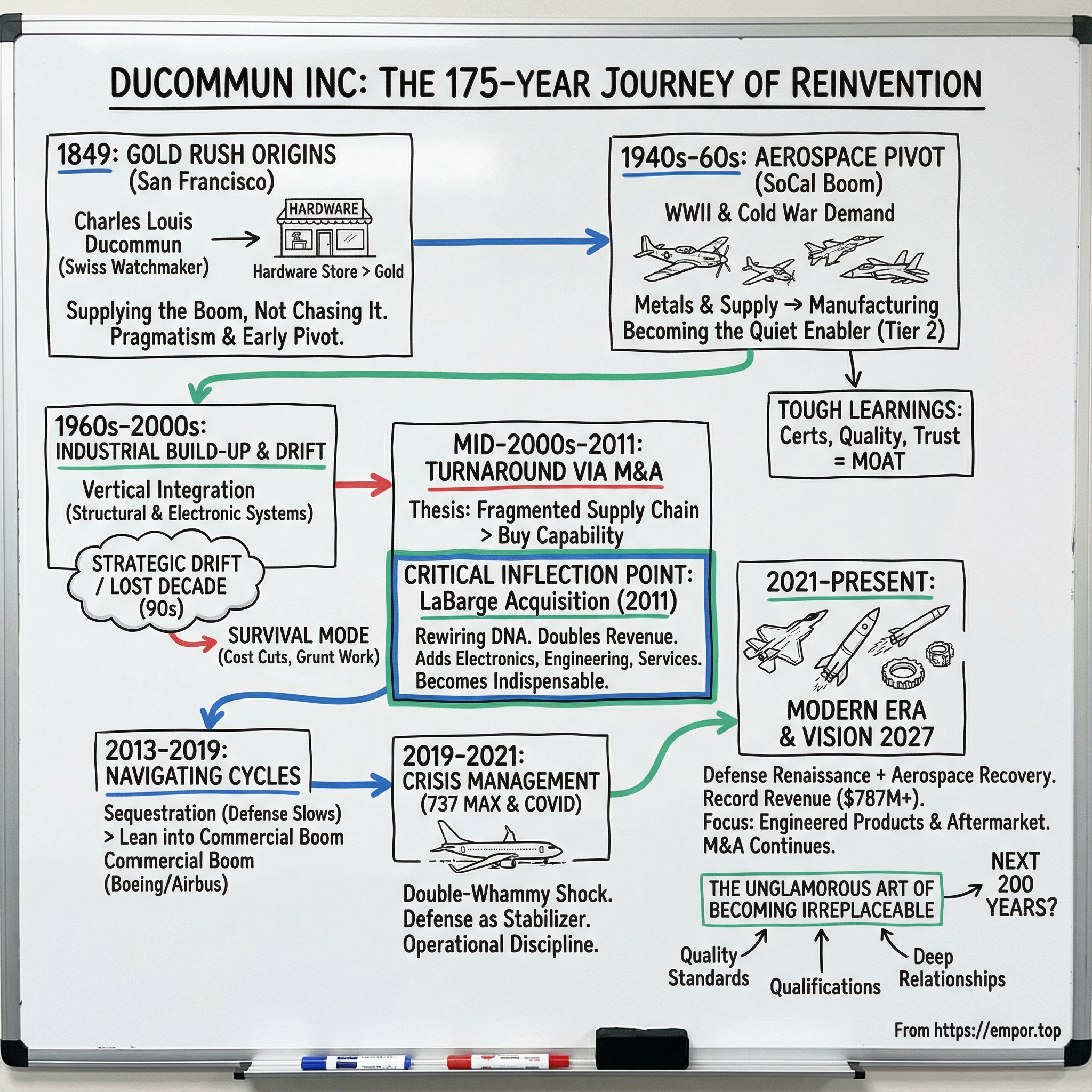

That one choice—sell to the miners instead of becoming one—set off a chain reaction that’s almost impossible to believe from the vantage point of modern aerospace. Because that little frontier-era supply business would eventually become the oldest incorporated company in California, still operating some 175 years later.

And Ducommun isn’t hanging on as a historical curiosity. Today it’s a $700+ million aerospace and defense supplier. Its parts fly on F-35 stealth fighters. Its electronics and structures show up in missile defense systems. Some of its work has even made its way to Mars.

So here’s the deceptively simple question that drives this story: how does a Gold Rush hardware store end up embedded inside America’s most advanced military and space programs?

The answer is a long sequence of reinventions—some intentional, some forced. There are near-death moments, periods of strategic drift, and then a handful of decisions that quietly change everything, including one acquisition that effectively rewired the company’s DNA. Along the way, Ducommun learns the unglamorous art of becoming irreplaceable: patient manufacturing discipline, brutal quality standards, and the kind of trust that takes years to earn and decades to displace.

This is a story about reinvention across generations. It’s about the hidden leverage inside aerospace supply chains—where relatively small suppliers can become mission-critical while staying invisible to almost everyone outside the industry. And it’s about what it really takes to survive for 175 years, through wars, booms, busts, and technological revolutions, when most companies can’t even make it to 20.

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s 1849, and a young Swiss immigrant steps off a ship into San Francisco Bay. California has Gold Rush fever. Thousands of people are clawing through riverbeds, convinced the next pan will change their lives.

Charles Louis Ducommun takes one look at the frenzy and makes a different bet. He doesn’t pick up a pickaxe. He opens a hardware store.

That choice—to sell the tools instead of chasing the gold—creates a business that’s still here, 175 years later, as the oldest incorporated company in California. And Ducommun isn’t surviving as a historical relic. Today it’s a global manufacturing and engineering supplier, building structural and electronic components, sub-assemblies, and engineered products that end up on Boeing’s 737 and 787, Airbus’s A320 and A220, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, F/A-18s, the C-17, Apache, Chinook, and Black Hawk helicopters—plus a long list of missile and defense programs most people never hear about.

So the question that drives this story is deceptively simple: how does a hardware store serving Gold Rush miners become a critical supplier inside America’s most advanced aerospace and military machines?

The answer isn’t a straight line. It’s a chain of reinventions—some deliberate, some forced—through near-death moments, strategic drift, and then a handful of decisions that quietly change everything. There’s one acquisition in particular that effectively rewires the company’s DNA. And underpinning all of it is the unglamorous work of becoming irreplaceable: earning certifications, hitting brutal quality standards, and building trust that takes years to win and decades to displace.

Ducommun was founded in 1849, and in 2024 it reported record full-year revenue of $787 million. Even more telling: it delivered fifteen consecutive quarters of year-over-year revenue growth—an outcome that doesn’t happen in aerospace by accident.

This is a story about reinvention across generations. It’s about the hidden leverage inside aerospace supply chains, where relatively small suppliers can become mission-critical while staying invisible to almost everyone outside the industry. And it’s about what it really takes to survive for 175 years, through wars, booms, busts, and technological revolutions.

If you’re an operator or investor watching niche industrial businesses, Ducommun is a masterclass in a few big ideas: the qualification moat that makes aerospace suppliers sticky, the brutal cyclicality of commercial aviation, the stabilizing power of defense diversification, and how well-executed M&A can transform a company’s trajectory. We’re going to unpack all of it.

II. The Gold Rush Origins & Early Survival (1849–1900)

This story doesn’t start in a boardroom or a factory. It starts on foot, on the frontier.

In 1849, Charles Louis Ducommun—a Swiss watchmaker—joined the gravitational pull of the California Gold Rush. He didn’t arrive with a team or a backer. He left Arkansas walking, with a mule carrying everything he owned. He was 29 years old, and smallpox had already blinded him in one eye.

The trip took nine months. Along the way came the usual horrors of the era: brutal weather, hunger, illness, and the ever-present risk that the trail would end before the dream did. It’s hard to overstate what that kind of journey implies. This wasn’t a “founder story” in the modern sense. It was survival, and then—somehow—building.

When Ducommun finally reached Los Angeles, it was still a frontier village of about 1,600 people. He opened a watch store. But Los Angeles was growing, and so was the opportunity. Over the next decades, the business stretched with the needs of the region—first into a general store for miners and ranchers, then into a hardware store serving the industries that were beginning to define Southern California, including construction and oil exploration.

The key insight showed up early, and it’s the same one that repeats across every boom in history: don’t chase the strike—sell to the people doing the chasing. Instead of gambling on gold with lottery-like odds, Ducommun built a business supplying the people and projects that were guaranteed to exist whether or not any one miner got rich. Picks and shovels, yes—but more broadly, the steady infrastructure of a growing economy.

And Los Angeles turned out to be a particularly good place to plant that flag. The city incorporated the next year, and its population doubled. Ducommun was positioned to grow with it.

So why did Ducommun survive when thousands of Gold Rush-era businesses disappeared?

A few things stand out. Ducommun was pragmatic—he focused on demand that persisted rather than windfalls that might never arrive. He benefited from geography—Los Angeles would later become a transportation hub, an oil center, and, eventually, the beating heart of American aerospace. And most importantly, the business learned to pivot early. Watches to general merchandise to hardware to industrial supply: the company kept changing shape without losing its core purpose—providing what fast-growing industries needed, reliably, in volume.

In 1896, Charles L. Ducommun died at 76, and the business passed to his four sons: Charles Albert, Alfred, Emil, and Edmond. They incorporated it as Ducommun Hardware Company and ran it primarily as a metals distributor.

That handoff mattered. Most family businesses don’t survive the generational transition. The Ducommun brothers did more than keep the lights on—they formalized the operation and set the company up for the industrial transformation that was about to sweep Southern California.

III. The Aerospace Pivot: World War II & the Southern California Boom (1940s–1960s)

In the 1920s and 1930s, Southern California was turning into something new. The climate was forgiving, land was cheap, and the region sat far from the military threats that haunted Europe and Asia. It was the perfect place for an industry still finding its wings: aviation.

Ducommun didn’t try to become the next aircraft maker. Instead, it did what it had always done best: supply the people building the boom. Most notably, the company backed a young aircraft designer named Donald Douglas with a line of credit, while also supplying metals and tools to his fledgling operation. It wasn’t just a sale. It was a wager on a customer—and on a future—before that future was obvious. Douglas Aircraft would go on to become one of the defining manufacturers of the American aerospace age, later merging into McDonnell Douglas and eventually being absorbed by Boeing.

That relationship also revealed a playbook Ducommun would keep running for the next century: don’t fight to be the headline. Be the quiet enabler. By embedding itself in the supply chain—rather than competing in the product market—Ducommun could ride the entire industry’s growth, not just the fortunes of any single prime contractor.

World War I gave the company an early glimpse of what that could look like at scale. Ducommun expanded its metals supply business, feeding copper, brass, and steel into the emerging defense economy for shipbuilding and munitions. Government-driven demand turned a regional supplier into something sturdier.

Then World War II arrived, and the transformation became permanent. In 1942, Ducommun rebranded again, this time as Ducommun Metals & Supply Co. As the U.S. ramped into wartime production, Ducommun’s large inventory of stainless and carbon steel became fuel for the factories building bomber and fighter aircraft, along with the ships that carried the war across both the European and Pacific theaters.

This was also the moment Southern California became the aviation wing of the Arsenal of Democracy. Douglas, Lockheed, Northrop—and Boeing’s operations in the region—were churning out aircraft at a pace that would have seemed impossible a decade earlier. Ducommun, sitting one layer down, was effectively diversified across all of them. It was an industry-wide bet, not a single-customer bet.

By 1949, Ducommun was recognized as the leading metal materials distributor in the West. Over the next decade and a half, it broadened its offerings to keep up with an aircraft industry that was rapidly becoming more complex—especially as electronics started to matter as much as metal.

And that complexity changed Ducommun, too. The post-war years marked the beginning of a shift from pure distribution to something more specialized. Ducommun started learning the aerospace rulebook the hard way: certifications, relentless quality standards, documentation requirements, and qualification cycles that could stretch for years. These weren’t annoyances. They were barriers—and once you’d cleared them, they became a kind of moat.

The Cold War kept the pressure—and the spending—on. Southern California became a core node of the growing defense-industrial complex, designing and building the jets, bombers, and early space systems that defined American power. Ducommun’s relationships deepened in parallel, and the company began its long transition from supplying raw materials to supplying engineered, aerospace-grade solutions.

IV. Building the Mid-Century Industrial Business (1960s–1990s)

After World War II, Ducommun’s next reinvention wasn’t a rebrand. It was a structural change in what the company actually did.

Through the 1960s—including acquisitions like VSI Corporation—Ducommun began moving from being primarily a distributor of metal and industrial supplies to being a manufacturer. That vertical integration is what ultimately formed the backbone of the company’s two modern pillars: Electronic Systems and Structural Systems.

And it mattered. Distribution is a volume game with thin margins and constant vulnerability—someone can always try to cut you out. Aerospace manufacturing is different. Once you’re making complex parts for a program, the relationship stops being transactional and starts becoming operational. You have to clear qualification requirements, meet punishing quality standards, and live inside your customer’s documentation and inspection universe. But if you do all that, you’re not easily replaced. In aerospace, being “on the program” is everything.

As Ducommun expanded beyond California, it started to look less like a regional supplier and more like a national industrial manufacturer. It was building increasingly sophisticated components for major defense programs and commercial aircraft, and in the process, it moved from “vendor” toward something closer to “trusted partner.”

To understand what that meant day to day, you have to zoom out and look at the aerospace supply chain pyramid. Ducommun operated largely as a Tier 2 supplier—making subassemblies that would be delivered to Tier 1 suppliers, who in turn deliver larger integrated systems to the prime contractors.

That position comes with a particular kind of pressure. Tier 2 isn’t where the headlines are, but it’s where the work has to be right. These suppliers often produce major structural and mechanical pieces, along with the building blocks that feed into larger electronic systems. And because modern aircraft contain vast numbers of electronic components that ultimately roll up into avionics and other mission-critical suites, the knock-on effects of a single miss can be enormous.

That’s why the relationship between Tier 1 and Tier 2 suppliers is so symbiotic. Tier 1 production simply doesn’t move without a reliable Tier 2 supply chain underneath it. The middle of the funnel carries a disproportionate share of the liability and responsibility—because if you’re late, out of spec, or noncompliant, the whole system feels it.

By the mid-1980s, though, Ducommun’s path forward was anything but settled. Chairman Wallace W. Booth, a former Rockwell International executive, pushed the company to focus more heavily on aerospace, and to do it at the expense of electronics. The shift sparked real internal conflict. President W. Donald Bell resigned in 1987, arguing that electronics hadn’t been supported adequately under the new strategy. The prior president, David G. Schmidt, had also resigned after just a year, following clashes with Booth. Not long after, Ducommun’s electronics components distribution businesses—Kierulff Electronics, MTI Systems, and Ducommun Data Systems—were sold to Arrow Electronics Inc.

Underneath the management turnover was a question that would keep haunting Ducommun: was it trying to be a broad industrial conglomerate, or a focused aerospace specialist?

The answer wouldn’t just shape the org chart. It would determine whether Ducommun could build a real identity—or drift into the kind of strategic muddle that quietly kills companies like this.

V. The Lost Decade & Strategic Drift (1990s–Early 2000s)

By the late 1980s, Ducommun wasn’t debating strategy. It was fighting to stay alive.

From 1985 to 1989, the company lost about $20 million a year on average. In 1988, Norman Barkeley was brought in with a new management team to replace Wallace Booth, and his mandate was blunt: “Survive.”

When a CEO’s mission statement is a single word like that, you know the situation isn’t about polishing operations or chasing a new market. It’s about making payroll, keeping lenders calm, and living to see the next quarter.

Part of the problem was bad luck. In 1986, the space shuttle Challenger exploded, and the fallout effectively sidelined AHF-Ducommun Inc.—a Ducommun subsidiary that made the shuttle’s fuel tanks—for roughly two years. At the same time, defense spending was slowing, which squeezed the rest of Ducommun’s aerospace exposure just as the company was already dealing with the internal whiplash of the prior decade.

It’s hard to design a more punishing combination: a flagship program stops cold, the broader defense tide goes out, and the company is still sorting out what it even wants to be.

Barkeley’s response wasn’t sexy, and that was the point. In the Wall Street Journal, he credited the turnaround to “plain old, ordinary grunt work”—raising prices where he could and cutting costs where he had to. By 1990, Ducommun was back in the black, posting nearly $2 million in income on $74 million in sales. It also slashed long-term debt by 75 percent in two years.

That playbook—back to basics, cost discipline, balance-sheet repair—didn’t just save Ducommun then. It became a muscle memory the company would need again and again.

But survival didn’t mean the story got easy. The 1990s brought the post-Cold War “peace dividend.” Defense budgets fell, primes merged, and the aerospace supply chain consolidated fast. Ducommun was in an awkward spot: too small to compete as a systems integrator alongside the big primes, but at risk of being seen as too interchangeable to command real pricing power.

Still, Barkeley managed to rebuild momentum. A series of acquisitions gave Ducommun meaningful roles across a spread of programs—McDonnell Douglas fighters, Boeing airliners, and even the space shuttle. By the end of his ten-year run in 1998, profitability reached a high-water mark. Ducommun posted its highest operating income ever—$29.8 million—on $170.8 million in sales.

Then leadership turned over again. Joseph Berenato succeeded Barkeley, first as president and CEO and later as chairman. He kept pushing the same growth formula—acquire and develop—but the market had changed. In 1998 and 1999, high valuations for targets effectively put Ducommun’s acquisition ambitions on ice.

The company was healthier than it had been a decade earlier. But the underlying tension never went away. In aerospace, the relationships that make you valuable can also make you vulnerable. Betting heavily on a few huge customers like Boeing can drive growth—right up until those customers stumble, and you feel the impact immediately.

VI. The Turnaround Begins: M&A as Growth Strategy (Mid-2000s–2010)

By the mid-2000s, Ducommun’s leadership finally locked onto a clear thesis: the aerospace supply chain was fragmented, and fragmentation creates an opening. If Ducommun could buy the right pockets of capability—then stitch them together—it could get bigger, more relevant, and harder to ignore. Not by becoming a prime, but by becoming the kind of supplier primes don’t want to live without.

This was a real pivot in what Ducommun was selling. Less commodity, more know-how. Less “we can make that part,” more “we can solve that problem.” And that shift—toward engineered, value-added products—ended up shaping the modern company.

The logic was simple. Basic aerostructures work, the “metal bending” layer of manufacturing, was getting commoditized. Price pressure was relentless. The path to better margins and stickier customer relationships ran uphill, toward electronics, engineered subsystems, and technical services—places where qualification takes longer, performance matters more, and switching suppliers is painful.

A set of acquisitions during this stretch helped Ducommun climb that hill. Miltec, in particular, brought something Ducommun needed badly: engineering services. Not just manufacturing to a drawing, but design, development, integration, and test—capabilities that pull a supplier earlier into programs and make it much tougher to replace once a platform is underway.

Ducommun Miltec operates in missile and aerospace system design, development, integration, and test, and it extends that expertise into NASA and commercial work. Its primary customers include the U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command (SMDC) and the Aviation and Missile Command (AMCOM), with additional major customers including the Missile and Space Intelligence Center (MSIC), the U.S. Navy, and NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC).

Strategically, Ducommun was building toward a two-segment model. Structural Systems would remain the company’s traditional aerostructures foundation. Electronic Systems would provide the higher-complexity layer—electronics and engineering—where programs tend to run longer and supplier positions can be more durable. The point wasn’t just diversification for its own sake; it was creating a portfolio that could cross-sell into the same primes, and be less exposed when any one corner of aerospace cooled off.

That, in turn, made deepening relationships with the primes—Boeing, Lockheed, Raytheon, Northrop—a central priority. In aerospace, incumbency is gravity. Once you’re qualified on a program, you can stay there for years. But getting qualified is hard, and for defense work it comes with regulatory gates too. Suppliers in the U.S. military and aerospace markets often need to be ITAR certified, under the International Traffic in Arms Regulations governing defense-related exports and related controls.

So the thesis sharpened: Ducommun wasn’t going to win by being the cheapest. It was going to win by being embedded—by building technical complexity, earning the qualifications, and becoming indispensable to customers who value execution and trust as much as cost.

VII. Critical Inflection Point: LaBarge Acquisition (2011)

Every company has a handful of decisions that don’t just change a quarter or a year—they change what the company is. For Ducommun, that decision arrived in 2011.

On April 4, 2011, Ducommun announced a definitive agreement to acquire LaBarge, Inc. LaBarge was a widely recognized electronics manufacturing services (EMS) provider operating across multiple high-growth industries, with revenue of $324 million for the twelve months ended January 2, 2011. For Ducommun, this wasn’t incremental. The deal would nearly double its revenue base, strengthen its position as a Tier 2 supplier in both aerostructures and electronics, and open doors to new customers and end markets.

The price underscored the scale of the bet: Ducommun agreed to pay $19.25 per share in cash, for a total purchase price of approximately $340 million, including the assumption of LaBarge’s outstanding debt.

That “nearly double” line is doing a lot of work. This wasn’t a tuck-in. Ducommun was committing to integrate a company roughly its own size—and to prove that its M&A thesis could hold at full scale, not just in manageable chunks.

Ducommun framed it plainly: “The acquisition solidifies Ducommun as a premier Tier 2 provider of both structural and electronic assemblies. By adding LaBarge to Ducommun Technologies, we will form one of the largest global aerospace and defense providers of EMS for high margin, low volume/high mix applications. We look forward to this next, exciting stage of our development.”

And the strategic logic was tight. LaBarge brought the electronics and engineering capabilities Ducommun wanted as it pushed up the value chain—critical electronics systems and subsystems, plus high-end engineering and design support, prototyping, program management, and testing. Just as important, it came with deep, long-term customer relationships, the kind that are hard to win and even harder for competitors to dislodge.

The two companies signed the merger agreement on April 3, 2011. LaBarge’s stockholders approved it on June 23, 2011, and each outstanding share was cancelled and converted into the right to receive $19.25 in cash. The vote wasn’t close: 99 percent of the shares voting approved the deal, representing 83 percent of total shares outstanding on the record date.

In the end, Ducommun acquired all issued and outstanding shares at $19.25 per share for a total purchase price of approximately $338 million, including the assumption of LaBarge’s outstanding debt of $27.5 million. The merger created Ducommun LaBarge Technologies (DLT), a new business segment formed by integrating LaBarge with Ducommun Technologies.

Craig LaBarge, LaBarge’s chairman, CEO, and president, captured the handoff: “It has been my privilege and pleasure to serve as CEO and president of LaBarge for the past 20 years. Today the LaBarge organization begins a new chapter and our outstanding team joins the Ducommun family, ready to continue providing customers with the highest levels of quality and service for complex electronic, electromechanical and mechanical products. I look forward to what the combined organizations can achieve together.”

The timing also mattered. The deal increased Ducommun’s defense exposure ahead of sequestration, while also positioning the company to participate in a commercial aerospace recovery. More than anything, though, this was the moment Ducommun stopped trying to become modern—and became it.

VIII. Navigating the 2010s: Defense Sequestration & Commercial Aerospace Boom

Then came 2013, and with it sequestration—the blunt, automatic budget cuts that threw a fog over defense programs. For contractors and suppliers alike, the fear wasn’t just lower spending. It was uncertainty: which programs would slow, which would be delayed, and which would get reshuffled entirely.

Ducommun’s response highlighted why the company had worked so hard to build a portfolio that wasn’t all-in on any one corner of aerospace. As defense spending tightened, Ducommun leaned harder into commercial.

And commercial, in the mid-2010s, was on fire. Boeing and Airbus were ramping production to meet a surge in global airline demand. The 737 MAX, 787 Dreamliner, and A320neo families expanded output, and for a Tier 2 supplier with meaningful positions across those platforms, that production wave did more than help—it cushioned the business against the defense wobble.

Inside the company, Ducommun LaBarge Technologies became a major engine of that next chapter. It built its reputation as a provider of electronics manufacturing services, including the design and manufacture of complex cable assemblies and interconnect systems, printed circuit board assemblies, and higher-level electronic, electromechanical and mechanical assemblies for high-reliability applications. It was also a leading supplier of electromechanical illuminated push button switches for the aerospace industry, microwave switches and components for the aerospace and wireless communications industries, and engineering, technical and program management services principally for the aerospace industry. And it served a spread of end markets—defense, aerospace, industrial, oil-and-gas, mining, and medical—that gave Ducommun yet another layer of insulation when any single sector cooled.

Strategically, the company kept circling a question that defines suppliers like this: are you build-to-print, or are you design-to-spec? Build-to-print means you manufacture exactly what the customer draws. It’s valuable work, but it’s also easier to shop, easier to squeeze, and easier to replace. Design-to-spec is different. That’s where Ducommun brings engineering value—helping shape what gets built, not just producing it. The company steadily pushed in that direction, because that’s where margins tend to be better and customer relationships get much harder to unwind.

At the same time, Ducommun doubled down on operational excellence—lean manufacturing, yield improvements, and cost reduction. In a business where margins can be won or lost on execution, a small improvement in scrap, rework, or throughput doesn’t just make the plant look better. It changes the economics.

One risk never went away, though: customer concentration. Boeing, in particular, represented a huge opportunity for content and scale—but it also created a very specific kind of fragility. When Boeing’s programs ran smoothly, Ducommun benefited immediately. When they didn’t, Ducommun felt that shock just as fast. And that tension—deep relationships that power growth, paired with dependence that can bite—was about to become the defining problem of the next chapter.

IX. The 737 MAX Crisis & COVID Double-Whammy (2019–2021)

March 2019 delivered a crisis Ducommun couldn’t influence, but couldn’t escape. On March 13, 2019, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration grounded the 737 MAX. Within days, the entire global fleet—387 aircraft—was parked, disrupting roughly 8,600 weekly flights across 59 airlines.

For Ducommun, this wasn’t just bad news on the evening broadcast. The 737 MAX was its biggest commercial aerospace program. When Boeing’s production slowed and then stopped, the shock ran straight down the supply chain. Plants that had been running hot suddenly had too much capacity and not enough demand. Fixed costs didn’t disappear just because the planes did.

The grounding was triggered by two fatal crashes in late 2018 and early 2019, and it detonated into a full-blown reckoning for Boeing—its engineering decisions, its culture, and its relationship with regulators. Investigators and critics pointed to a mix of factors: flaws tied to the MAX’s new flight control software, internal pressure to keep pace with Airbus, limited transparency around the system, and inadequate oversight by the FAA.

And when the prime contractor stumbles, everyone underneath it pays. Boeing’s supply chain—components, subassemblies, simulators—took the hit in lockstep. By the time the FAA recertified the MAX in November 2020, Boeing’s net orders were down by more than a thousand aircraft. The program’s direct costs were estimated around $20 billion, with indirect costs north of $60 billion.

Then the second wave hit.

COVID arrived in 2020 and turned commercial aviation from “down” to “off.” Airlines stopped flying, carriers deferred deliveries, and the entire aerospace industry fell into a hole that no planning model had really contemplated. The combination—MAX grounding plus a global pandemic—was a true double-whammy.

This is where Ducommun’s portfolio design finally showed its value. Defense became the stabilizer. Even as commercial demand deteriorated sharply, Ducommun managed the combined MAX-and-COVID shock with limited impact on adjusted EBITDA, largely by growing its military and space business—from $278 million in 2018 to $421 million in 2022—and by moving early on cost.

The playbook in a moment like this is rarely glamorous, but it’s decisive: aggressive cost cuts, facility consolidations, and a single-minded focus on cash and liquidity. Management made painful workforce decisions while working to protect the capabilities that mattered long-term. Capital allocation tilted hard toward preservation, with only selective strategic investments kept alive.

There were signs of thaw. Boeing resumed 737 MAX production on May 27, 2020. On December 29, 2020, American Airlines became the first U.S. airline to put the MAX back into commercial service.

But the bigger takeaway from this period wasn’t the date the line restarted. It was what the company learned—and proved—about resilience: diversification across defense and commercial markets, the operational flexibility to scale down and back up, a conservative balance sheet that bought time, and the discipline to wait for recovery rather than making desperation moves.

X. Modern Era: Defense Renaissance & Aerospace Recovery (2021–Present)

By the early 2020s, Ducommun entered what might be its best setup in decades: a leaner company, a clearer strategy, and end markets finally blowing in its direction.

A lot of that traces back to a leadership change a few years earlier. In 2017, Stephen G. Oswald became Ducommun’s president and CEO, and in 2018 he was appointed chairman of the board. He moved quickly to streamline the organization and sharpen Ducommun’s focus on aerospace and defense. In his first five years, the company also expanded into aftermarket products and services through five strategic acquisitions. Then, in December 2022, Ducommun rolled out “Vision 2027,” a plan to push further into engineered products and aftermarket content, deepen its presence on key commercial platforms, execute its “off-loading” strategy with defense primes, and keep consolidating its facility footprint.

Oswald’s background helps explain why the playbook looked the way it did. He came to Ducommun after serving as CEO of Capital Safety and before that holding senior roles at United Technologies Corporation, with a career that also included Hoechst Celanese. He joined Ducommun effective January 23, 2017, bringing roughly 30 years of industry experience. At Capital Safety—a former KKR portfolio company acquired in 2012—he grew revenue at a compounded annual rate of 10% and helped guide the business to a sale in 2015 for $2.5 billion. At UTC, he spent 15 years in leadership positions, including president of the Hamilton Sundstrand Industrial Division, where he led the division to more than $1 billion in revenue and delivered strong EBITDA growth.

Capital Safety’s sale to 3M became one of the notable private equity transactions of 2015 and delivered a $1.8 billion return—about 3x—for investors and management. In other words, Oswald didn’t just know industrial operations. He knew how to create shareholder value in industrial businesses.

Then the macro winds shifted. Geopolitical tensions—Ukraine, China, and a broader rise in defense spending—created real tailwinds for defense-exposed suppliers. Ducommun carried a robust backlog exceeding $1.0 billion, including military and space backlog that increased by $100 million to $625 million.

The acquisition strategy continued to reinforce the same themes: more engineered content, more aftermarket, and more stickiness. In 2023, Ducommun completed its acquisition of BLR Aerospace. Oswald said at the time: “I am pleased that the acquisition has now closed and would like to welcome the BLR team to Ducommun. BLR’s product offerings further strengthens our engineered products portfolio at the company and adds as well very important aftermarket business.” Founded in 1992, BLR is a provider of aerodynamic systems designed to enhance the productivity, performance, and safety of rotary- and fixed-wing aircraft across commercial and military platforms.

It was the fifth—and largest—acquisition since Oswald joined in 2017, and it fit Vision 2027 neatly: engineered products plus aftermarket services for rotorcraft and fixed-wing business aviation OEMs and fleet operators.

By the end of 2024, Ducommun was showing what that strategy looked like in results. The company reported record annual revenue of $787 million and a strong three-year total shareholder return, ranking at the 79th percentile versus the Russell 2000. Quarterly revenue topped $190 million for the sixth straight quarter, rising to about $197 million, helping deliver that record year. Profitability moved, too: gross margin increased 180 basis points year-over-year to 23.5% for the quarter, and 350 basis points for the full year to 25.1%, another all-time record.

And then came a moment that tested management’s commitment to staying independent. In 2024, Ducommun received an unsolicited, non-binding indication of interest from Albion River LLC, a private direct investment firm, proposing to acquire all outstanding shares for $60.00 per share in cash. Ducommun’s board unanimously concluded it wasn’t in the best interests of the company or shareholders to pursue discussions.

Albion River came back in July 2024 with a higher $65.00 per share cash offer. The board again unanimously declined to engage.

Their rationale was straightforward: they believed the offered price—and the generic actions described—significantly undervalued Ducommun and risked distracting the team from executing Vision 2027. The board’s message was clear: Ducommun was not for sale, and leadership intended to keep compounding value through the existing strategy.

For investors, that’s a loud signal. Ducommun walked away from a meaningful premium because management and the board believed the standalone plan was worth more. Now the only question is whether Vision 2027 delivers enough to prove them right.

XI. The Business Model Deep Dive

To understand Ducommun’s competitive position, you have to understand how aerospace actually makes money—and why the supply chain behaves the way it does.

At the top of the pyramid, final aircraft manufacturing is highly concentrated. In large commercial jets, it’s basically an Airbus-and-Boeing world. That concentration creates enormous buyer power. But it’s only half the story. The other half is that the parts going into those planes are so specialized, and the standards are so unforgiving, that only a limited number of suppliers can reliably produce many key systems and components. In practice, that specialization puts a ceiling on how much leverage either side can really exert.

Zoom in one layer, and you see the scale of the machine. A large aerospace OEM can have more than 12,000 Tier 2 and Tier 3 suppliers. These lower-tier suppliers are critical, but they’re also numerous and scattered around the globe—which makes the whole system both resilient and fragile at the same time.

How you get paid matters just as much as what you make. Ducommun operates across long-term agreements (LTAs), cost-plus contracts, and firm fixed price arrangements. Each comes with a different tradeoff. Fixed-price work can be great when execution is tight, but it’s punishing when costs run ahead of estimates. Cost-plus is typically steadier and more predictable, but it caps the upside.

The real moat in aerospace isn’t a clever marketing angle. It’s the qualification barrier. Aerospace manufacturers prioritize stable, long-term supplier relationships because the stakes are existential: safety, reliability, regulatory compliance, and performance. Switching suppliers isn’t just “finding another shop.” It can mean requalification, re-testing, re-documenting, and re-earning trust—often over years. Those stable relationships also help protect hard-won know-how in an R&D-intensive industry, where leakage matters.

And the complexity is almost hard to picture. One airliner can contain millions of individual parts if you count every fastener and electronic component. Deloitte points out that a large aerospace OEM may manage over 200 direct Tier 1 suppliers and more than 12,000 Tier 2 and Tier 3 suppliers behind them. That’s a supply chain management problem on an industrial scale—and it’s why “small” delays aren’t small. A missing bolt, gasket, or connector can cascade into a late delivery for an entire aircraft.

This is also why program lifecycle matters so much. Development doesn’t usually throw off much revenue, but it’s where positions get established. Production is where volume and profits show up. And then there’s sustainment and aftermarket—work that can last for decades and often carries more predictable, better margin characteristics than pure production. Ducommun’s push into engineered products and aftermarket content isn’t accidental; it’s a recognition that the longest-lived cash flows in aerospace tend to come after the first aircraft is delivered.

Operationally, Ducommun runs through two core areas. Electronic Systems focuses on full-service manufacturing for high mix, low volume complex electronics where the cost of failure is extremely high. That includes high-reliability interconnect systems, printed circuit board assemblies, and integrated electronic, electromechanical, and mechanical assemblies. Structural Systems is the traditional backbone: large, complex contoured structural components and assemblies. The toolbox there includes stretch-forming, thermal-forming, chemical milling, precision fabrication, machining, finishing processes, and integrating those components into subassemblies.

Then there’s the part of the business model that doesn’t show up in glossy program photos: working capital. Aerospace production cycles are long, inventory is complex, and customer payment terms can tie up cash for extended periods. Managing that well is a competitive advantage in itself—because it determines how much the company can invest, how much flexibility it has in downturns, and how painful growth becomes.

Finally, there’s the constant make-versus-buy question. Vertical integration can capture margin and control, but it demands capital, talent, and time. Ducommun’s acquisition strategy has effectively served as selective vertical integration—adding capabilities through M&A rather than trying to build everything from scratch.

XII. Hamilton's 7 Powers & Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Hamilton's 7 Powers Assessment

Switching Costs: MODERATE-HIGH In aerospace, being “qualified” is everything. Once Ducommun is approved on a program, the customer can’t just swap in a new supplier the way they might in other industries. Re-certification is slow, expensive, and risky. That makes Ducommun’s positions on platforms like the F-35 and 737 inherently sticky. The caveat is that not all work is equally protected: on more commodity-like parts, switching is still very doable.

Scale Economics: LIMITED Ducommun absolutely gets some benefits from scale—better purchasing leverage, more consistent facility utilization, and the ability to spread overhead across a bigger revenue base. But it’s still not “big” in the context that matters. In Structural Systems especially, it runs into much larger suppliers like Spirit AeroSystems, Triumph Group, Howmet Aerospace, and SIFCO Industries. Against companies of that size, Ducommun’s scale advantage tends to disappear.

Process Power: MODERATE Ducommun has built real process capability over decades: manufacturing know-how, quality systems, and the discipline required to meet aerospace certifications and documentation requirements. That creates a barrier—especially for smaller shops that can’t afford to climb the learning curve. But it’s not magic. With enough capital, time, and customer access, competitors can replicate many of these processes.

Network Effects: MINIMAL This isn’t a network-effects business. Ducommun doesn’t get more valuable just because more participants exist around it. The value is in execution and qualification, not in building a platform ecosystem.

Branding: LIMITED In B2B aerospace, the “brand” that matters is your reputation with engineers and procurement teams: quality, reliability, delivery performance, and how you behave when things go wrong. That’s important, but it’s not consumer brand equity. Ducommun’s name doesn’t pull demand the way a household brand would.

Counter-Positioning: LIMITED There’s no structural reason a larger competitor couldn’t pursue similar moves—buy capabilities, broaden offerings, push into higher-value engineered work. Ducommun can execute well, but the model itself doesn’t lock out bigger players.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE What Ducommun does have is hard to recreate quickly: long-term customer relationships, program-specific institutional knowledge, and incumbent positions on critical platforms. Those are valuable resources—especially in aerospace, where trust is accumulated slowly. They just aren’t truly exclusive.

Verdict: Ducommun’s power is real, but it’s not overwhelming. The defensibility comes from qualification barriers, process discipline, and relationship depth—not from structural scale advantages. It’s a business you can protect, but you have to keep earning your place.

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Rivalry Among Competitors: MODERATE-HIGH Tier 2 is competitive. It’s fragmented, it’s consolidating, and there are always capable shops chasing work. Larger competitors often bring more resources, but Ducommun’s edge comes from playing in specialized, high-reliability engineered niches—and from being able to serve both commercial and defense markets. The company’s acquisition strategy has helped it build a broader technical toolkit and stay relevant where customers care about more than just price.

Threat of New Entrants: LOW The barriers to entry are enormous. Aerospace systems are built from massive webs of parts that all have to work together under extreme requirements. The Boeing 787, for example, draws major components from dozens of large suppliers—and behind them sits a long tail of suppliers providing everything from electronics and switches to hardware and finishes. In total, the Tier 1, 2, and 3 supplier base runs into the thousands. Getting into that ecosystem—and staying there—requires certifications, audits, proven performance, and years of trust-building.

Supplier Power: MODERATE Some inputs are constrained, especially specialized materials, but Ducommun generally has multiple sourcing options. Still, material shortages can hit hard. Titanium, for example, became acutely limited after the war in Ukraine, creating ripple effects that tightened availability for essential components across the industry.

Buyer Power: HIGH This is the big one. Prime contractors like Boeing, Lockheed, Raytheon, and Northrop have enormous leverage over Tier 2 suppliers. Price pressure never really stops, and customer concentration adds another layer of risk: when a major customer slows down, changes terms, or has a crisis, the impact travels downstream fast.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE There are substitutes at the margin—additive manufacturing, new materials, or primes bringing work in-house through vertical integration. But aerospace moves slowly, and once a supplier is locked into a program, displacement is difficult. The installed base and certification environment protect incumbents, even as manufacturing technology evolves.

Industry Attractiveness Assessment: The Tier 2 aerospace supply chain is moderately attractive. You can build defensible positions through qualifications and deep customer relationships, but profitability is structurally constrained by buyer power. This isn’t a fast-win industry. It rewards the companies that execute relentlessly and let small advantages compound over a long time.

XIII. Playbook: Lessons for Operators & Investors

The Reinvention Imperative: Making it to 175 years isn’t about preserving a legacy. It’s about shedding it, repeatedly. Ducommun has been a watch shop, a hardware store, a metals distributor, an electronics business, and now an aerospace manufacturer. The meta-lesson is the willingness to change what the company is, not just how it operates, when the environment demands it.

M&A as Strategy: In fragmented industrial markets, consolidation can be the fastest path to relevance—if you can integrate. LaBarge showed how a single deal can reposition a company overnight, moving Ducommun up the value chain. But the warning label is just as important: integrations can also destroy value through culture clashes, system mismatches, and operational disruption.

The Qualification Moat: The unglamorous stuff is the moat. Certifications, audits, documentation, and long qualification cycles can take years, but that time investment creates stickiness. Once you’re on a program, getting replaced is slow, expensive, and risky—which is exactly why patient capital can work so well in aerospace.

Cyclicality Management: Defense plus commercial diversification isn’t a nice-to-have; it’s survival gear. Ducommun’s ability to lean on defense when commercial aviation collapsed in 2020 is the clearest proof. Single-market exposure in aerospace can look fine in the upcycle, right until it suddenly isn’t.

Customer Concentration Risk: The deepest relationships are often the most dangerous. Boeing is the perfect example: huge program content and huge upside when things run smoothly, but real vulnerability when the prime hits turbulence. Concentration can power growth, but it can also turn external problems into internal crises.

Operational Excellence Matters: In low-margin manufacturing, execution is the strategy. Small improvements in throughput, scrap, rework, and labor productivity compound into real financial outcomes. Ducommun’s higher revenue per employee in 2023 versus 2022 is the kind of signal that tells you the machine is getting tighter, not just bigger.

Crisis Navigation: The downturn playbook is simple, and it’s brutal: protect liquidity, cut costs fast, consolidate where you must, and still invest selectively where the long-term advantage is worth it. Ducommun’s 2019–2020 response worked because it balanced urgency with restraint—staying alive without blowing up the future.

The "Picks and Shovels" Strategy: Ducommun doesn’t have to win the prime contractor wars. It just has to keep supplying the primes. That “sell to the builders” posture—spread across platforms and customers—reduces single-program risk and lets the company benefit from broader industry growth.

Niche Manufacturing Arbitrage: Technical complexity plus qualification barriers is where pricing power lives. The value-creation path is moving from interchangeable work—the commodity end of “metal bending”—into engineered solutions where performance, reliability, and trust matter as much as cost.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Considerations

Bull Case

Defense Upcycle: If Pentagon budgets keep rising with geopolitical tension, Ducommun’s defense exposure becomes a tailwind, not just a hedge. The company carried backlog above $1.0 billion, with military and space backlog increasing by $100 million to $625 million. That growth was driven mainly by higher military and space revenue tied to missile programs, electronic warfare, and ground vehicle platforms.

Space Market Explosion: Space is no longer a science project. Commercial players like SpaceX and Blue Origin are scaling, and military space continues to expand alongside them. Ducommun already has positions on key space programs—and if those programs ramp, the content can ramp with them.

Commercial Aerospace Recovery: Commercial is the other half of the comeback story. Production rates were recovering, and there was real pent-up demand in the system. Management said it expected Boeing’s progress on safety and quality to translate into better stability and production growth in the second half of 2025 and into 2026. Layer on expected growth at Airbus, and the outlook for Ducommun’s commercial aerospace work improves materially.

Operational Leverage: This is where the model can surprise people. When volumes come back, fixed costs don’t rise linearly—so incremental revenue can fall to the bottom line. Ducommun’s target is an 18% EBITDA margin by 2027, with revenue near $950 million, supported by a push to lift engineered products and aftermarket revenue to 25% of total revenue.

Consolidation Target: Even if management insists it’s not for sale, the interest is real. The rejected Albion River approaches signaled that Ducommun is on acquirers’ radar. And shareholders have already seen meaningful value creation: market capitalization rose from about $286 million at the end of 2016 to about $929 million as of July 2024.

Bear Case

Customer Concentration: The dark mirror of “deep relationships” is dependence. Boeing is the obvious risk—when Boeing hurts, Ducommun feels it fast. The 737 MAX grounding made that vulnerability impossible to ignore, and any future stumbles would land downstream again.

Margin Pressure: Aerospace buyer power never takes a vacation. Prime contractors squeeze suppliers relentlessly, and that structural reality caps pricing power no matter how well-run the shop floor is.

Scale Disadvantage: Ducommun competes in a world where size matters. Larger players like Spirit AeroSystems (now being reacquired by Boeing) and Howmet Aerospace can often spread overhead, buy materials, and invest in automation at levels Ducommun can’t match.

Cyclicality: Aerospace cycles don’t get abolished; they just lull you into thinking they have. Commercial aviation will turn down again at some point, and timing that turn is notoriously hard.

Technology Disruption: Over time, additive manufacturing, new materials, and primes pulling work in-house could chip away at today’s positions—especially on work that isn’t deeply engineered or tightly program-embedded.

Geopolitical Risk: Defense spending can be a tailwind, until it isn’t. Budget cuts, program cancellations, or shifts in spending priorities could weaken Ducommun’s defense portfolio even if the broader company is executing well.

Key Metrics to Track

Backlog and Book-to-Bill Ratio: Backlog is the closest thing aerospace gets to a forward-looking dashboard. Book-to-bill above 1.0 generally signals expansion; below 1.0 can be an early warning. Backlog as of September 28, 2024 was $1,043.9 million, up from $993.6 million as of December 31, 2023.

Defense vs. Commercial Revenue Mix: This mix determines how the next downturn feels. A heavier defense mix tends to stabilize results, while commercial exposure can amplify upside in a boom. Military and space revenue was $109 million in Q4 2024, up from $104 million in Q4 2023.

Gross Margin Trend: Margin is where the strategy either shows up—or doesn’t. Ducommun’s gross margin hit a record 26.6% in Q1 2025, improving by 200 basis points year-over-year, supporting the narrative that engineered content is becoming a bigger part of the company’s economic engine.

XV. Epilogue & Reflections

The paradox at the heart of Ducommun’s story is that America’s oldest California company has stayed alive by refusing to stay the same. The business that exists today barely resembles Charles Ducommun’s watch shop, or the hardware store that stocked the Gold Rush. And yet the throughline is unmistakable: a company that adapts, stays practical, and reinvents itself when the world changes.

So what does it actually take to survive for 175 years? Ducommun’s record points to a handful of repeatable ingredients: strategic flexibility (the willingness to walk away from legacy businesses when they stop making sense), geographic luck (being in Southern California just as aerospace took off), relationship depth (earning a place inside customers’ programs over decades), operational pragmatism (the “grunt work” Norman Barkeley talked about), and crisis resilience (the ability to take hits that could’ve ended the company—and keep going).

Most companies never get close. The average lifespan of an S&P 500 company has reportedly fallen from around 60 years in 1950 to under 20 years today. Against that backdrop, Ducommun’s ability to outlast technological revolutions, wars, financial crises, and industry reshuffles isn’t just unusual—it’s the story.

One of the clearest modern proof points was the successful delivery of NASA’s Orion spacecraft for the Artemis I mission, which included critical components manufactured by Ducommun. It’s the same arc, just at a different altitude: a company that started by supplying prospectors ends up supplying some of the most demanding engineering programs on Earth—and beyond it.

That’s the underappreciated reality of aerospace: the hidden giants matter as much as the names on the aircraft. When an F-35 completes a mission, when a 787 crosses an ocean, when a rover touches down on Mars, the success is distributed across a supply chain that rarely gets credit. Ducommun’s work isn’t famous. It’s just necessary.

And what happens next? Ducommun could keep executing Vision 2027 and remain independent. It could eventually become an acquisition target for a larger aerospace consolidator or private equity, and the unsolicited Albion River approaches suggest there’s real interest. Or it could get squeezed if Boeing’s challenges deepen or if defense budgets take an unexpected turn.

In 2024, Ducommun marked “175 years young,” with a market cap that had roughly tripled since the end of 2016. Which leaves the only question that really fits a company like this: can Ducommun make it to 200 years?

Given the track record, it’s hard to bet against reinvention.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music